- 1Department of Nursing, University of Applied Health Sciences, Zagreb, Croatia

- 2Department of Nursing, Faculty of Health Studies, University of Rijeka, Rijeka, Croatia

- 3Department of Surgery, Faculty of Medicine, Collegium Medicum, University of Rzeszów, Rzeszow, Poland

Editorial on the Research Topic

Patient and medical staff safety and healthy work environment in the 21st century

As the 21st century unfolds, bringing rapid technological advances and shifting societal expectations, the healthcare sector faces many challenges and opportunities (1). At the forefront of this transformation lies a dual imperative: ensuring patient safety while simultaneously safeguarding the wellbeing of medical staff (2). A severe shortage of medical staff increases the risk to patient safety and creates an enormous obligation for policymakers and hospital management to work extensively on the creation of a healthy work environment (3). Emotional exhaustion among nurses is a critical factor that significantly impacts patient safety and the overall quality of care in healthcare settings (4).

A healthy, supported, and protected healthcare workforce is the foundation upon which safe, effective, and compassionate patient care is provided (5).

Understanding safety in a complex healthcare ecosystem

Patient safety has evolved significantly since the publication of the seminal report To Err Is Human (6), which brought global attention to the alarming rates of preventable medical errors. Since then, various safety protocols, guidelines, and regulatory frameworks have been introduced (6). However, the complexity of modern healthcare systems means that risks to safety are constantly changing. High patient acuity, staffing shortages, increasing administrative burdens, and rising healthcare demands contribute to a work environment in which both patients and staff are vulnerable (7).

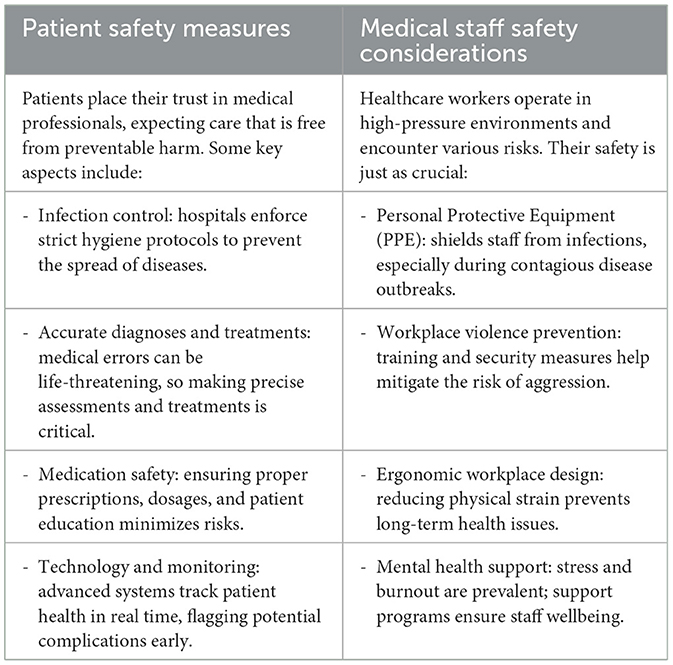

Staff safety has increasingly become a critical concern. According to the World Health Organization, healthcare workers experience some of the highest rates of occupational injury, burnout, and workplace violence (1). The COVID-19 pandemic further underscored these vulnerabilities, revealing significant gaps in emergency preparedness, access to mental health support, and systemic resilience. Whether the goal is ensuring patient wellbeing during medical procedures or safeguarding healthcare workers from occupational hazards, a secure environment is essential for quality care. Table 1 presents key elements of patient and medical staff safety.

The psychological dimension: burnout and moral injury

Burnout is no longer an isolated issue—it is a widespread occupational syndrome that affects every level of the healthcare workforce (8). Characterized by emotional exhaustion, depersonalization, and a diminished sense of personal accomplishment, burnout compromises clinical decision-making, reduces empathy, and increases the risk of medical errors (9). Compounded by the increasing administrative load and misalignment between organizational goals and personal values, many healthcare professionals have also reported symptoms of moral injury—the psychological distress that arises when they are unable to provide the quality of care they know is needed due to systemic constraints (10).

This erosion of the workforce's emotional and psychological health has had a direct impact on patient outcomes. Studies have consistently shown that clinician wellbeing is a strong predictor of patient safety, quality of care, and patient satisfaction.

Building a culture of safety

A global perspective illustrates how different regions address patient and staff safety. In Europe, the EU-OSHA Healthy Workplaces Campaign 2023–2025 has emphasized the importance of managing psychosocial risks and promoting digital safety in continental healthcare environments (11). In North America, the Occupational Safety and Health Administration (OSHA) has developed specific guidelines on workplace violence in healthcare, highlighting its impact on staff protection and patient outcomes (12). In Asia, research from Singapore documented high levels of burnout among healthcare workers during the COVID-19 pandemic and identified associated risk factors (13). Complementing this, the WHO Western Pacific Regional Office report underlined the need for sustained investment in workforce protection and capacity building in the post-pandemic era (14). Together, these examples strengthen the global scope of the discussion and illustrate the universal relevance of integrating patient safety with staff wellbeing.

Creating a safe and healthy healthcare environment requires a fundamental shift from individual accountability to systems-based thinking. Healthcare workers must be supported by organizational structures that prioritize safety, transparency, and continuous improvement (15). This includes:

• Leadership commitment to safety as a core organizational value, not just a compliance metric.

• Empowered reporting systems that encourage staff to report near misses and errors without fear of retribution.

• Workplace design improvements, such as ergonomic facilities, adequate rest areas, and reduced noise pollution, all of which enhance focus and reduce stress.

• Adequate staffing levels and skill mix to avoid overwork and ensure proper patient-to-provider ratios.

• Flexible scheduling and leave policies that promote work-life balance and prevent fatigue.

A safety culture must be more than an abstract goal—it must be implemented in daily practice, communication, and organizational policy. It also requires the involvement of all stakeholders, including patients, whose voices can help identify blind spots and improve system responsiveness (15).

Technology in healthcare

Technology is playing an increasingly prominent role in shaping the healthcare work environment. From electronic health records (EHRs) to AI-enabled decision support systems, digital tools have the potential to reduce errors, improve diagnoses, and streamline care delivery (16).

Healthcare institutions must adopt a human-centered approach to technology implementation. This involves engaging clinicians in the design and testing of digital tools, ensuring proper training, and continuously monitoring the impact of technology on both staff workload and patient outcomes.

As healthcare systems increasingly rely on interconnected digital platforms, cybersecurity and data privacy must be integral components of safety strategies. Ensuring the confidentiality, integrity, and availability of patient information protects both patients and staff from emerging digital threats (17). Alongside these benefits, however, research also points to risks associated with digitalization. Work-related technologies can contribute to technostress, blurred boundaries between work and private life, and increased psychosocial strain on staff, as highlighted in a recent scoping review of the public sector (18). At the same time, other evidence confirms that the adoption of digital health technologies can significantly improve staff performance while reducing workload, particularly in resource-constrained hospital environments (19).

Occupational health: from reactive to preventive models

Occupational health in healthcare settings has often been reactive, focusing on injury management and infection control. A 21st-century approach must be preventive and holistic. Insights from other sectors also demonstrate the value of digital technologies—systematic reviews highlight how wearables, sensors, and AI can transform occupational health by enabling real-time monitoring and prevention strategies (20). This includes:

• Regular mental health screenings and support services.

• Promotion of healthy lifestyle behaviors through institutional wellness programs.

• Measures to prevent workplace violence, including training in de-escalation and physical security.

• Access to vaccinations and personal protective equipment as standard protocol.

In addition, the introduction of digital technologies into daily workflows has been associated with psychosocial challenges such as technostress and work–life imbalance, as highlighted by Håkansta et al. (18). These findings emphasize that occupational health strategies must address not only physical but also digital and psychosocial risks. Emerging Industry 4.0 innovations—such as drones, collaborative robots, wearable sensors, and VR/AR-based training—are increasingly being applied to strengthen occupational safety and health systems (21). These technologies provide new opportunities for proactive monitoring, prevention, and staff training.

Health systems must also acknowledge the long-term effects of traumatic experiences, especially among emergency and critical care workers (22). Providing access to trauma-informed care and peer support programs is essential to maintaining a resilient workforce. Incorporating digital health technologies has also been shown to ease workload pressures and enhance efficiency among healthcare staff, thereby contributing to preventive occupational health strategies (19).

Equity and inclusion as safety imperatives

The health and safety of healthcare environments are deeply linked to equity and inclusion. Marginalized staff often experience higher levels of discrimination, abuse, microaggressions, and psychological distress (23–26).

By embedding equity into safety strategies—through bias training, inclusive hiring practices, and patient-centered communication—healthcare organizations can address both overt and subtle risks to wellbeing.

Conclusion: the path forward

Patient safety and staff wellbeing must be addressed as one system-level priority. Safe healthcare environments require collaboration across professions and sustained investment in education, innovation, and human resources. The COVID-19 pandemic demonstrated globally—from Europe to North America and Asia—that unprepared systems face higher rates of burnout, errors, and loss of trust. The cost of neglect extends beyond preventable harm to diminished public confidence. Aligning staff wellbeing with patient safety is essential to ensuring effective, compassionate, and resilient healthcare.

Author contributions

AF: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Funding acquisition, Investigation, Methodology, Project administration, Resources, Software, Supervision, Validation, Visualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. SB: Conceptualization, Data curation, Methodology, Project administration, Software, Supervision, Visualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. SK: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Methodology, Validation, Visualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. IK: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Methodology, Supervision, Validation, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. JK-B: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Methodology, Resources, Validation, Visualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. BF: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Methodology, Supervision, Validation, Visualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The author(s) declare that no Gen AI was used in the creation of this manuscript.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Publisher's note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

1. World Health Organization. Global Patient Safety Action Plan 2021–2030: Towards Eliminating Avoidable Harm in Health Care. Geneva: WHO (2021). Available online at: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789240032705 (Accessed Jun 13, 2025).

2. Tsikala P, Civka K, Friganovic A. Nurses forward innovation for advanced patient safety: report of the European Patient Safety Foundation (EUPSF) conference, Madrid (2024). Intens Crit Care Nurs. (2025) 90:104085. doi: 10.1016/j.iccn.2025.104085

3. Friganović A, Slijepčević J, ReŽić S, Cristina Alfonso-Arias C, Borzuchowska M, Constantinescu-Dobra A, et al. Critical care nurses' perceptions of abuse and its impact on healthy work environments in five european countries: a cross-sectional study. Int J Public Health. (2024) 69:1607026. doi: 10.3389/ijph.2024.1607849

4. Labrague LJ, Al Sabei S, Al Rawajfah O, Burney I, AbuAlRub, R. Linking emotional exhaustion to adverse patient events in paediatric and women's health nursing units: the mediating role of nurses' adherence to patient safety protocols. Int J Nurs Pract. (2025) 31:e70026. doi: 10.1111/ijn.70026

5. Jaber MJ, Bindahmsh AA, Baker OG, Alaqlan A, Almotairi SM, Elmohandis ZE, et al. Burnout combating strategies, triggers, implications, and self-coping mechanisms among nurses working in Saudi Arabia: a multicenter, mixed methods study. BMC Nurs. (2025) 24:590. doi: 10.1186/s12912-025-03191-w

6. Neuhaus C, Grawe P, Bergström J, St Pierre M. The impact of “To Err Is Human” on patient safety in anesthesiology. A bibliometric analysis of 20 years of research. Front Med. (2022) 9:980684. doi: 10.3389/fmed.2022.980684

7. Braithwaite J, Ellis LA, Churruca K, Long JC, Hibbert P, Clay-Williams R. Complexity science as a frame for understanding the management and delivery of high quality and safer care. In:Textbook of Patient Safety and Clinical Risk Management. Donaldson L, Ricciardi W, Sheridan S, Tartaglia R, , editors. Sydney, NSW: Springer (2020). p. 375–91. doi: 10.1007/978-3-030-59403-9_27

8. Gilbert-Ouimet M, Zahiriharsini A, Lam LY, Truchon M. Associations between self-compassion and moral injury among healthcare workers: a cross-sectional study. Nurs Ethics. (2024) 2024:9697330241299536. doi: 10.1177/09697330241299536

9. Roger C, Ling L, Petrier M, Elotmani L, Atchade E, Allaouchiche B, et al. Occurrences of post-traumatic stress disorder, anxiety, depression, and burnout syndrome in ICU staff workers after two-year of the COVID-19 pandemic: the international PSY-CO in ICU study. Ann Gen Psychiatry. (2024) 23:3. doi: 10.1186/s12991-023-00488-5

10. Fradley K, Sirois F, Bentall R, Ray J, Bishop R, Wadsley J, et al. Assessing moral injury in health care workers living in secular societies: introducing the Health care-Moral Injury Scale (HMIS). Br J Health Psychol. (2025) 30:e12810. doi: 10.1111/bjhp.12810

11. European Agency for Safety and Health at Work Safe and Healthy Work in the Digital Age: Healthy Workplaces Campaign 2023-2025. Publications Office of the European Union (2023).

12. Occupational Safety and Health Administration (OSHA). Workplace Violence in Healthcare: Understanding the Challenge. Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Labor (2023). Available online at: https://www.osha.gov/healthcare/workplace-violence

13. Tan BYQ, Kanneganti A, Lim LJH, Tan M, Chua YX, Tan L, et al. Burnout and associated factors among health care workers in singapore during the COVID-19 pandemic. J Am Med Dir Assoc. (2020) 21:1751–8.e5. doi: 10.1016/j.jamda.2020.09.035

14. World Health Organization Regional Office for the Western Pacific. Report of the Regional Director: The Work of WHO in the Western Pacific Region, 1 July 2022. – 30 June 2023. Manila: WHO Western Pacific Region (2023). Available online at: https://apps.who.int/publications/i/item/9789290620204

15. O'Connor E, McGrath SY, Castillon C, Ralph A, Kennedy E, Kerrigan V. “There is much more to learn still”: embedding culturally safe practice education into medical school programs. J Rac Ethnic Health Dispar. (2025). doi: 10.1007/s40615-025-02462-1

16. Thitame SN, Aher AA. AI-driven advancements in bioinformatics: transforming healthcare and science. J Pharm Bioallied Sci. (2025) 17(Suppl. 1):S24–7. doi: 10.4103/jpbs.jpbs_389_25

17. He Y, Aliyu A, Evans M, Luo C. Health care cybersecurity challenges and solutions under the climate of COVID-19: scoping review. J Med Internet Res. (2021) 23:e21747. doi: 10.2196/21747

18. Håkansta C, Asp A, Palm K. Effects of work-related digital technology on occupational health in the public sector: a scoping review. Work. (2025) 81:2477–90. doi: 10.1177/10519815251320274

19. Jeilani A, Hussein A. Impact of digital health technologies adoption on healthcare workers' performance and workload: perspective with DOI and TOE models. BMC Health Serv Res. (2025) 25:271. doi: 10.1186/s12913-025-12414-4

20. Jiang L, Zhang J, Wong YD. Digital technology in occupational health of manufacturing industries: a systematic literature review. SN Appl Sci. (2024) 6:631. doi: 10.1007/s42452-024-06349-4

21. Koh D, Tan A. Applications and impact of industry 4.0: technological innovations in occupational safety and health. Saf Health Work. (2024) 15:379–81. doi: 10.1016/j.shaw.2024.09.001

22. García-Rudolph A, Sanchez-Pinsach D, Remacha J, Patricio S, Opisso E. ChatGPT as a rising force: can AI bridge information gaps in Occupational Risk Prevention? Work. (2025). doi: 10.1177/10519815251348355

23. Llaurado-Serra M, Santos EC, Grogues MP, Constantinescu-Dobra A, Cotiu MA, Dobrowolska B, et al. Critical care nurses' intention to leave and related factors: survey results from 5 European countries. Intens Crit Care Nurs. (2025) 88:103998. doi: 10.1016/j.iccn.2025.103998

24. Georgiou E, Hadjibalassi M, Friganović A, Sabou A, Gutysz-Wojnicka A, Constantinescu-Dobra A, et al. Evaluation of a blended training solution for critical care nurses' work environment: lessons learned from focus groups in four European countries. Nurse Educ Pract. (2023) 73:103811. doi: 10.1016/j.nepr.2023.103811

25. Komen A, Vuckovic M. The relationship between physical activity and professional burnout syndrome among physiotherapists in Croatia. World Health. (2024) 7:23–8.

Keywords: patient, medical staff, nurses, healthy work place, work environment

Citation: Friganovic A, Boskovic S, Krupa Nurcek S, Kovacevic I, Kosydar-Bochenek J and Filipovic B (2025) Editorial: Patient and medical staff safety and healthy work environment in the 21st century. Front. Public Health 13:1677117. doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2025.1677117

Received: 31 July 2025; Accepted: 03 September 2025;

Published: 07 October 2025.

Edited and reviewed by: Arwa Alumran, Imam Abdulrahman Bin Faisal University, Saudi Arabia

Copyright © 2025 Friganovic, Boskovic, Krupa Nurcek, Kovacevic, Kosydar-Bochenek and Filipovic. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Adriano Friganovic, YWRyaWFub0BoZG1zYXJpc3QuaHI=

Adriano Friganovic

Adriano Friganovic Sandra Boskovic

Sandra Boskovic Sabina Krupa Nurcek3

Sabina Krupa Nurcek3 Irena Kovacevic

Irena Kovacevic Justyna Kosydar-Bochenek

Justyna Kosydar-Bochenek Biljana Filipovic

Biljana Filipovic