- 1Cornell University Public Health Program, Ithaca, NY, United States

- 2Cornell University Health Impacts Core, Ithaca, NY, United States

- 3Department of Public & Ecosystem Health, Cornell University, Ithaca, NY, United States

Introduction: To reinforce and re-build the public health workforce, many capacity building interventions are in place. While pre-post assessments are often used to describe short-term outcomes, methods to assess and describe longer-term outcomes and impacts are wanting. Our work aimed to help close this gap by exploring ways to assess and describe longer-term outcomes, including how capacity gains contribute to new actions taken by individual workers and organizations in support of public health goals. We hoped this work might inform development of an evaluation framework able to measure outcomes and impacts of public health workforce capacity-building initiatives.

Methods: Building from short-term outcomes data demonstrating changes in participant capacity (knowledge, skill, confidence), we used a multiple case study design to explore outcomes resulting from the use of the online Public Health Essentials (PHE) capacity building intervention. We conducted in-depth interviews with a purposive sample of eight PHE graduates (Summer 2023-Spring 2024) to elucidate both medium-term outcomes and potential longer-term impacts. Qualitative interviews were coded and analyzed using a priori and emergent themes (Spring-Fall 2024).

Results: Interview analysis revealed outcomes grouped into 13 themes. PHE graduates described how capacity growth influenced seven individual capabilities and their ability to take collective or shared actions in three areas. Further, they described their ability to influence changes in conditions in three areas critical public health: health equity, social determinants of health, and prevention.

Conclusion: Evaluating longer-term outcomes and impacts of capacity building interventions is crucial to both improve and justify public health workforce development initiatives, particularly as prevention and population health needs persist. We posit that evaluations will be more effective if standardized methods are used across interventions, and if there is a greater push to share and publish results. We present a conceptual framework that may inform and guide future evaluation and process improvement efforts.

Introduction

The health and wellbeing of people in their communities and ecosystems is Public Health (1–3). This state is assured by the collective work of people and organizations influencing the policies, practices, and systems that work to prevent disease or injury, promote health, and prolong life (1–4). To achieve this, an interdisciplinary workforce is required, equipped with right-fit knowledge, skills, and capacities to support delivery of core functions and essential services (1, 2, 4–6).

Prompted by the COVID-19 pandemic, and in anticipation of future public health needs, governments, allied organizations, and working groups around the world have developed competency frameworks and guidance to support the development and growth of the public health workforce (1, 2, 7, 8). Together, these have informed and spurred refinements to public health education frameworks (e.g., bachelors, masters, doctoral degrees in public health) (9–11), and have expanded capacity-building interventions and new methods for public health worker recruitment, in-service training, and retention (10, 12–14). For example, in the US, public health workforce assessment and enumeration efforts have shown that the public health system is understaffed (4), and that the current public health workforce has skills gaps and training needs (15). During and following the COVID-19 emergency, many initiatives were developed to help backfill and meet critical public health workforce needs through hiring, training, and up-skilling (16, 17). The outcomes of these efforts, however, are not yet well elucidated (15).

Building public health workforce capacities

Many approaches are used to build capacities among public health workers, such as education in degree-granting programs, in-service training, online training, and mentoring for new and existing workers (1, 18–21). The World Health Organization (WHO) reports that capacity development is a result of learning content delivered, organization of the content, teaching methods used, learning and learner experiences, and the methods of assessment used with the learners (1). To support this, WHO working groups have defined essential public health functions, subfunctions, and services; provided guidance to help strengthen competency-based training and education oriented toward the delivery of the essential public health functions; and mapping and measuring the diversity of occupations involved in delivering—and needed to ensure delivery of—these functions (1, 2, 7).

Methods and models used for public health workforce assessment and development in the US align with the WHO guidance. For example, the Public Health Workforce Interest and Needs Survey (PH WINS) reliably assesses workforce training needs and skill gaps among the governmental public health workforce (15, 22), helping to inform education and capacity-building efforts (6, 17, 23–27). Workforce development strategies in the US largely focus on building knowledge and skills in “specialized skill” domains (e.g., epidemiology), as well as the Core Competencies for Public Health Professionals (8), and the Public Health Strategic Skills (28), in both degree-granting public health education programs (9–11), and through workforce development/ training efforts. These frameworks aim to build foundational, cross-cutting capacities in areas such as Effective Communication; Data-Based Decision Making; Cross-Sectoral Partnerships; Leadership; Systems Thinking; Community Engagement; Change Management; and Program Planning, equipping public health workers and organizations to ensure The 10 Essential Public Health Services in their communities (29). Additional influences on public health capacity building in the US focus on ensuring public health programs are aligned to community needs, re-building public trust in public health, and collaborative practice for collective impact (3, 6, 17, 30, 31).

Translating capacities into action

While numerous approaches are being used to build capacities among the public health workforce in the US and globally, there is a paucity of reports on if or how workforce training needs are being met, and if or how increased workforce capacity manifests in real-world settings (32). We posit that a focus on this is critical. At present, despite a concerted focus on workforce development, literature to help inform evaluation of outcomes is scant. For example, repeat rounds of PH WINS show no significant change closure of skills gaps despite the broad availability of capacity building resources (15). Further, while there is some literature reporting on the short-term effectiveness of trainings (e.g., knowledge or skill-gains pre-post training intervention) (14, 33, 34), a 2023 study on COVID-19 contact tracing scale-up stated that their work was the “first comprehensive analysis” that aimed to illustrate the interrelationships between the capacities, capabilities, outcomes, and impacts (35). This may be because impacts are not easy to identify—especially in the short-term—and are highly context-specific. Evaluation of longer-term outcomes or impacts appear more prevalent in health care fields, where the application of expanded capacities can be observed by a supervisor or an evaluator (36–38), but even an implementation study exploring workers’ expanded capacity to address HIV and TB identified public health impacts as an evaluation criterion that was hard to measure. The research team reported several challenges in monitoring and reporting on public health impacts, including building systems for monitoring impacts, securing resources, and engaging leadership (39).

We propose that there is an opportunity for expanded investigation around public health workforce development, globally. More robust, shorter-term evaluations of workforce development efforts are needed to measure and improve intervention effectiveness. Additionally, we posit that evaluation of capacity building interventions must go a step further and explore if or how gained capacity translates into mid-and-longer-term outcomes and collective public health benefits or impacts. And, while this may need to be context specific, we posit that there may be standard framing or frameworks that could be used. To test the feasibility of this, we designed an initial exploratory process focused on one cohort of learners.

Filling the gap—public health essentials as a case study

As a part of the multi-pronged approach to reinforce the public health workforce in the US, our team developed and deployed a capacity-building intervention. The Public Health Essentials (PHE) curriculum was designed to build and assess competence in 54 skill areas, and developed using pedagogical and behavior change theories (14). PHE is a cohort-based, facilitated, on-line intervention that builds competence and confidence among new and existing public health workers over a 15- to 20-week period (14). The approach aims to rapidly equip people working in public health roles with the knowledge and applied skills needed for foundational public health work (14). PHE comprises 75 h of content, and all learning and assessment is completed in an asynchronous classroom. Learners access and complete lessons and graded competency assignments and receive developmental feedback from expert facilitators (14).

Prior PHE-focused research focused on understanding outputs (e.g., program uptake, completion rate) and short-term outcomes (e.g., changes in worker competence and confidence); this work showed that PHE graduates demonstrate significant competency gains, and report an ability to apply knowledge and skills acquired to their work (14, 40). However, these studies did not get at the So What: does expanded capacity translate into actions to advance public health, and if so, how. This is what we set out to explore in this project.

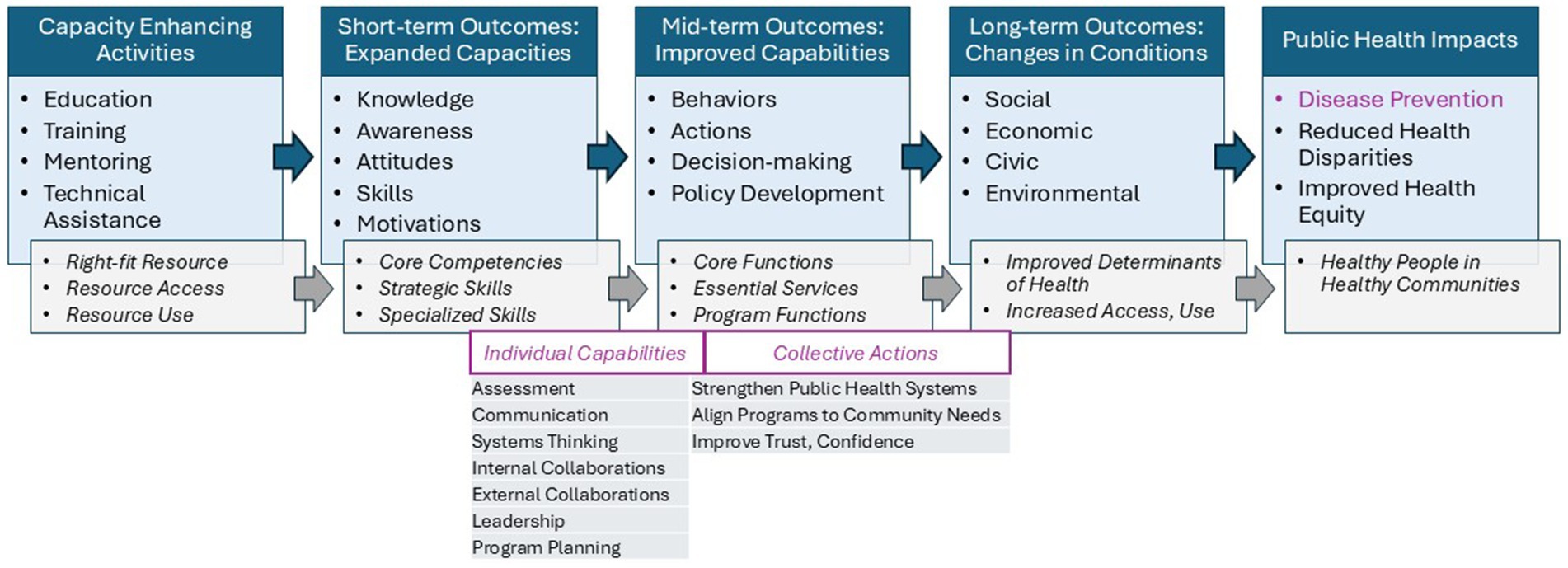

To explore this “so what” of a capacity building intervention that shows short-term effectiveness, we used a logic model/pathway to impacts approach to expand our a priori theory of change. We knew that activities [the PHE intervention] had led to short-term outcomes [improved knowledge, skill, motivation], but we had only hypothesized that those might lead to mid-term outcomes [changes in capabilities manifest as behaviors, actions] and longer-term outcomes [changes in conditions] that could result in community health impacts (Figure 1). As PHE was designed to build Core Competencies and Public Health Strategic Skills, we further hypothesized that these capacities could equip a worker with stronger capabilities aligned with the essential services of public health, allowing them to contribute to changing systems and processes to improve wellbeing.

Methods

We used a qualitative case study approach to assess this: how capacity gains among PHE graduates are translating into public health-focused outcomes (Cornell IRB Protocol #00147810). PHE graduates who had demonstrated increased competence (expanded capacities) across 54 skill areas post-PHE were qualified to participate. To control for possible bias inherent from working within a public health department, we applied purposive sampling to a national cohort of community-based public health workers not working in governmental public health (n = 58). Eight respondents were selected based on geography (a variety of US states), work location (community based), and responses to a screening survey about how they were applying PHE-supported learning into their current work (articulate a community public health need that they were focused on). Interviewees provided both written informed and verbal consent.

The interview protocol was developed and piloted by members of our research. Interviews were conducted Summer 2023-Spring 2024 by (DL, JL, CF) and focused on five key questions related to (a) the focus of their public health work, (b) their motivation to do this work, (c) what actions they take to achieve this, (d) what outputs and outcomes they are seeing, and (e) how PHE-derived skills have helped them do this work.

Interviews were recorded (Zoom, Version 5.15.7 or 5.17.2); transcripts were generated (Rev Transcription Services), cleaned (JL), and coded for themes (Dedoose version 9.2.006) by two qualitative researchers (JL, CF) using a shared codebook that was developed in an iterative manner. Initial codes focused on actions or behaviors, and were proposed a priori from our literature review (including Core Competencies, Strategic Skills, Essential Services); these were expanded and clarified during pilot interviews using a modified hybrid approach (41) where two coders (JL, CF) assessed alignment and divergence of code application, discussed code application strategies and definitions, and developed a code book. Consultation with other team members regarding any discrepancy helped solidify consistent application of codes. Between-coder triangulation was used until consensus in code application was reached.

Qualitative analyses of the coded transcripts were conducted Spring-Fall 2024 (JL, CF). Code application frequencies were used to explore cross-case themes (Dedoose, Version 9.2.006) and to identify emergent capabilities being applied to modify conditions to improve community health.

Results

Expanded capacities

All respondents (n = 8) were women and all reported working in the field of public health for at least 3 years. All respondents worked in rural counties in the U. S., including in NY (n = 3), NE (n = 2), WI (n = 1), AR (n = 1) and NC (n = 1). Each respondent recalled having completed PHE in the preceding 1–2 years and having appreciated knowledge and skill gains (expanded capacities) as a result. Respondents reported participating in PHE for a variety of reasons, including broadening their understanding of public health and learning new frameworks to apply to their public health work.

A priori, we hypothesized that the PHE graduates might be able to describe how their PHE-supported changes in knowledge and skill (short-term outcomes) have led to changes in their capabilities (mid-term outcomes), helping them work toward community impacts. Via the coding process, two distinct types of “improved capabilities” were noted: behaviors or actions taken by an individual (Individual Capabilities), and behaviors or actions taken by an organization (Collective Actions); respondents also described some outcomes (Changes in Conditions) they hoped to see as a result of their actions.

Improved capabilities

When asked to describe how the knowledge and skills gained in PHE influenced their work, 224 excerpts were coded as Individual Capabilities. In general, individual capability codes focused on the behaviors or actions an individual takes in their day-to-day public health work. Based on our a priori framework, we envisioned hearing about individual actions aligned with the 10 Essential Services, but codes ended up focusing on a mix of Core Competencies, Strategic Skills, and Essential Services.

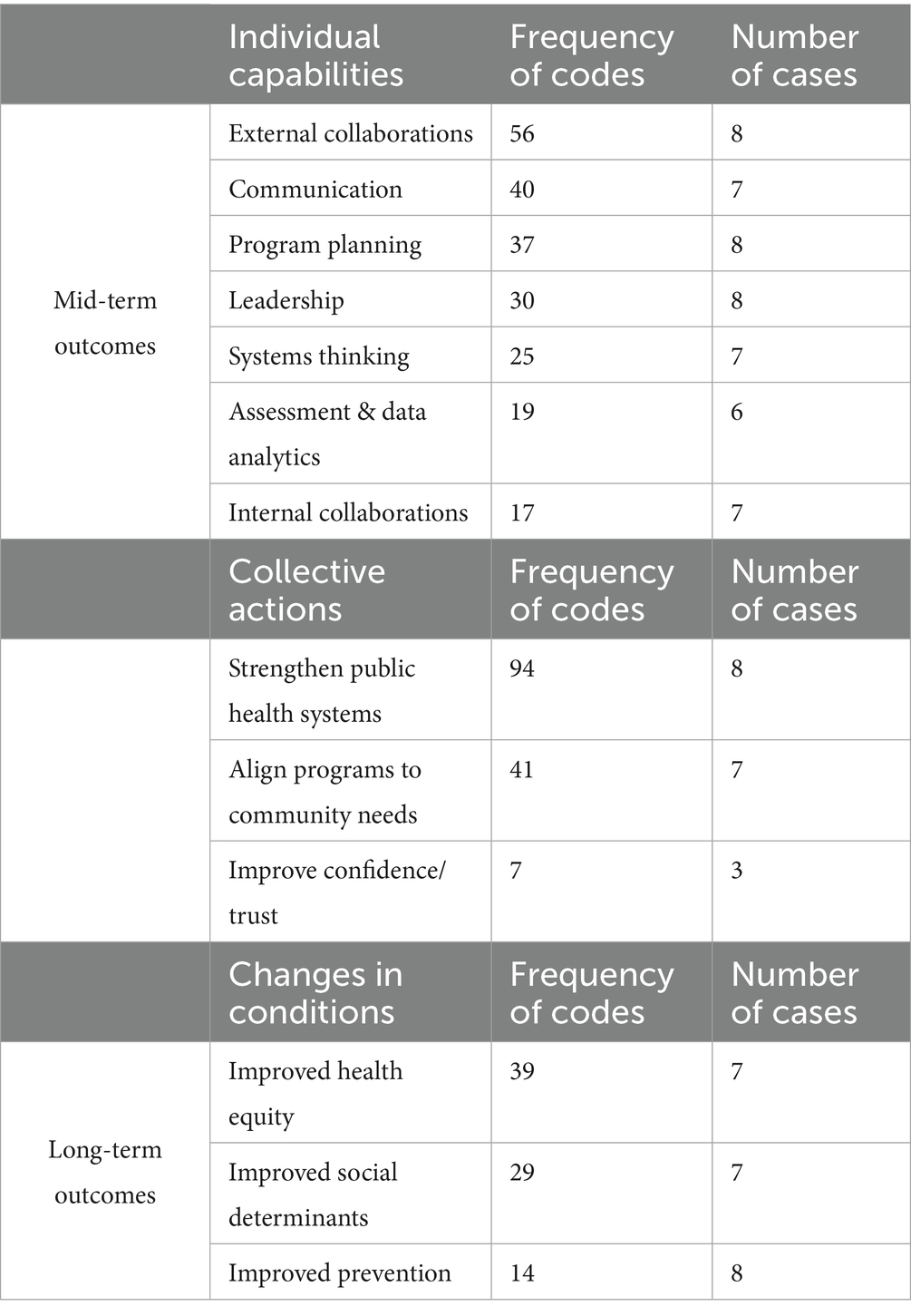

Across the eight cases, seven Individual Capabilities themes were noted (Table 1), including investments in External Collaborations (n = 56), Communication (n = 40), Program Planning (n = 37), and Leadership (n = 30). All themes except Advocacy were noted by at least 75% of the cases.

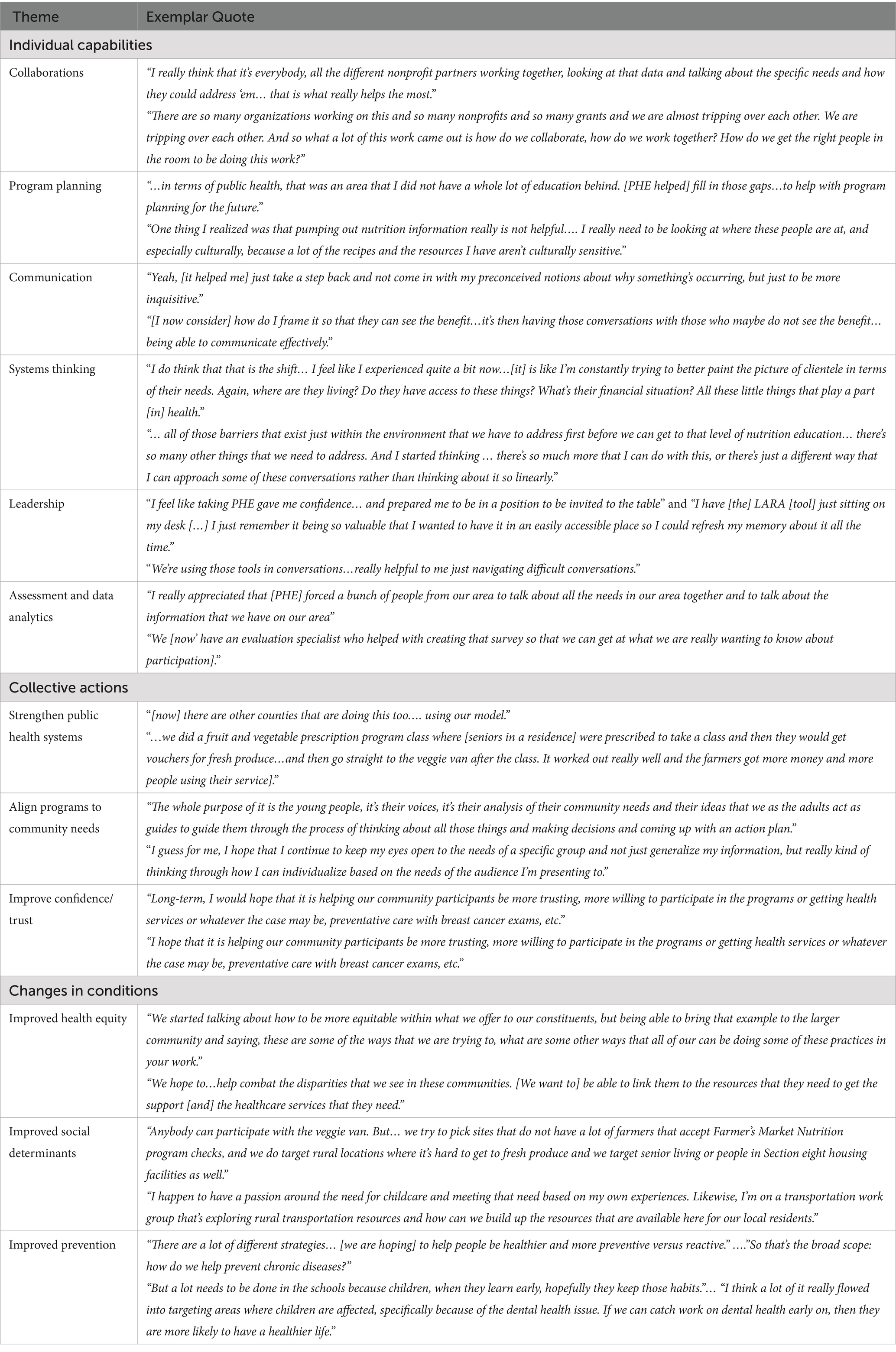

Collaboration was coded when respondents reported translating PHE-skills building to invest in sustained, long-term, ongoing reciprocal partnerships where teamwork increased or workloads were shared. This was further segmented into collaborations with others within their workplace (Internal Collaboration), vs. collaboration with community members or organizations (External Collaboration). Program Planning was coded when respondents reported translating skills to create, champion, and/or implement policies or programs to address health needs. See sample quotes in Table 2.

Table 2. Exemplar quotes from interviewees highlighting individual capabilities, collective actions, and changes in conditions.

Communication was coded when respondents reported translating PHE-skills building to develop or disseminate information to help inform and educate, including working with community stakeholders to ensure culturally and linguistically appropriate communications. Systems Thinking was coded when respondents reported translating skills to engage cross-sectoral partners to understand and explore inter-related systems, including when working to develop a shared vision of how to better collaborate to address public health needs.

Leadership was coded when respondents reported translating PHE-skills building to lead or support teamwork, collaboration, or action. Assessment and Data Analytics was coded when respondents described translating skills to collect data to understand needs or opportunities, or to use data to guide actions.

Collective actions

When asked to report on how the knowledge and skills gained in PHE influenced their work, 152 excerpts were coded as Collective Actions. In general, collective action codes focused on the reason a person, an organization, or a group took or is taking action; these appeared to focus loosely on the Essential Services. Across the eight cases, three Collective Action themes were noted (Table 1), including Strengthen Public Health Systems (n = 94), Align Programs to Community Needs (n = 41), and Improve Confidence/Trust (n = 17). All themes except Improve Confidence/Trust were noted by at least 75% of the cases. Strengthen Public Health Systems was coded when respondents reported translating PHE-skills building to broaden the networks of organizations contributing to public health, working to enhance capacity among those working to support public health, and improving cross-sectoral collaborations to meet a need. Align Programs to Community Needs was coded when respondents reported translating skills to help adapt or improve programs—based on qualitative or quantitative data—to better meet the needs of a community. Public Confidence/Trust was coded when respondents reported translating skills to aim to [re]build trust in public health and the public health system. See exemplar quotes in Table 2.

Changes in conditions

When asked to describe why they are focused on the projects highlighted in the interviews, all respondents reported a focus on at least one “Changes in Conditions” related to influencing the health and wellbeing of the communities they serve. Each respondent was able to clearly articulate a community public health need that their work focused on (e.g., improving food access, food security, fruit and vegetable consumption, health-supporting behaviors, youth development, and community development). Some 82 excerpts were coded across the eight cases, three Changes in Conditions themes were noted (Table 1), including Improved Health Equity (n = 39), Improved Social Determinants (n = 29), and Improved Prevention (n = 14). Improved Health Equity was coded when respondents reported taking actions to ensure inclusion or improved diversity, or to specifically improve health equity. Improved Social Determinants was coded when respondents reported explicitly addressing needs related to a determinant of health, such as housing, transportation, quality food access, education, or quality health care. Improve Prevention was coded when respondents reported explicitly working to prevent disease or harm or disability. Several respondents talked about working with youth to develop healthy lifelong habits, such as eating healthy foods and going to the dentist.

Across the interviews, respondents also spoke to the “why” behind their work, or what motivates them invest to in public service. Respondents focused on altruistic themes: “I want to implement programs that will make a difference.” “I would love just to see people eating healthier and having better access to this produce.”

Cross theme analysis

PHE was designed to build Core Competencies and Public Health Strategic Skills and we hypothesized that with expanded capacities, public health workers would feel more equipped to contribute to changing systems and processes to improve wellbeing. Across the interviews, respondents articulated how they believe completing PHE benefited them. Beyond feeling more equipped with stronger knowledge and expanded skills, they described shifts in their understanding of public health and their role within it. Respondents described that PHE helped them gain a broader perspective of public health, including a stronger emphasis on prevention, community engagement, collaboration, and being responsive to actual (not presumed) needs. For example: “[Before PHE] I wasn’t thinking about the other factors that come into play. It is not just whether or not someone has access to the money to purchase these foods. [It is] do they have access to get to the grocery store? Where’s that located? What other things are happening within their household that might be interfering with that or what environmental factors come into play that create barriers and challenges for them? [Before] I was narrowly focused, I think, on my approach.”

Respondents shared case examples of how they have translated their capacity into actions linked to engagement, network-building, assessment, and program planning, and reflected on how they believe their improved work has resulted in stronger relationships between organizations and community members, improved programs that address community needs (e.g., increased food access, overcoming transportation or access barriers), and growing trust in public health initiatives. For example: “I wasn’t expecting how much more broadly it helped me to think about the work that I’m doing, the partnerships that I have that I would not have necessarily included in conversations about public health that I should have been thinking about--everything that they do.” Respondents also shared that they believe these outcomes can serve to promote long-term health-focused behaviors, reduce stigma, and support local economies. For example: “It is making sure that people are collaborating and for the good of the community because it is for the community. It is not for us, it is for the community.”

Discussion

Globally, there is a deficit of public health and health care workers: an estimated 12.9 million will be needed by 2035 (42). In the US alone, an estimated 100,000 new public health workers are needed now (4). Public health workforce needs are further strained in the US as an estimated 84% of government public health workers have no formal public health training (15), and more than 50% report skills gaps and training needs (15). As we look to the future of public health, a skilled and interdisciplinary workforce is essential. Existing research on career pipelines and pathways suggests that, in addition to stronger recruiting pipelines from accredited public health programs (43), and stronger workplace policies to engage and retain workers (44), real-time/in-service capacity building will remain a priority (4, 5, 17, 23). However, in strained funding environments, being able to demonstrate outcomes from investments of time and money in workforce development is critical.

This study sought to explore methods to evaluate whether and how public health workforce capacity-building interventions [such as PHE] may translate into meaningful public health action that helps to create conditions where communities can achieve health. While some existing research documents intervention-related gains in capacity and confidence among public health workers, there is a critical gap in exploring the “so what?”: does expanded capacity lead to changes in behaviors or actions that can support positive health impacts? Prior research showed that individuals who participated in the in-depth capacity enhancing intervention, PHE, demonstrated expanded capacities in 54 core competencies and strategic skills (14). This study took this a step further. Developing a theory of change based on existing public health workforce frameworks allowed us to articulate potential pathways to impact and helped to inform a research design.

Application of qualitative methods helped us explore these pathways and identify themes to explore more broadly. We sampled a sub-set of PHE graduates and invited them to describe how investments in their own capacity have impacted their work. Broadly, participants were able to describe translation of knowledge and skills into improved capabilities. Coding elucidated a series of individual behaviors and actions that participants apply in their work; these were aligned with the Core Competencies (8) and Strategic Skills (28) frameworks, and began to touch on some of the Essential Services (29). For example, participants described deep investments in communication and collaboration and applying systems thinking and leadership to inform data access and use and program planning. Coding also elucidated collective or team-based actions that participants apply in their work; these aligned with the Essential Services (29). For example, participants described working to strengthen public health systems, to better align programs to community needs, and to ensure trust and confidence in the public health system. Finally, participants also described the impetus for their work, or the changes in conditions that they seek. Broadly, these aligned with the goals and mission of public health: to focus on disease prevention, to improve the social drivers of health, and to work toward health equity. These themes are encouraging, given today’s public health focus and priorities, where current literature suggests that cross-sector collaboration is critical to improving public health (3, 45, 46), and that this is supported by the application of core competencies and strategic skills (3, 6, 47–49).

Using a theory of change framework and qualitative methods, we were able to explore how expanded knowledge and skills among practitioners led to improved individual capabilities, collective organizational actions, and changes in community conditions. For our specific case study, we were able to elucidate how learners see and describe changes in their Individual Capabilities, and how these contribute to Collective Actions. We were able to see how the reported capabilities aligned well with competencies and services expected of the workforce (e.g., Core Competencies for Public Health Professionals and/or Strategic Skills domains such as communication, systems thinking, collaboration, and leadership), and how those led to both individual actions and team-based/collective actions aligned with the Essential Services (e.g., assessment, planning, strengthening systems, building trust; Figure 2). These findings suggest that when interventions are thoughtfully designed and delivered, they can catalyze shifts in practice—enhancing collaboration, communication, leadership, and systems thinking. These capabilities support stronger public health systems, better alignment of programs to community needs, and efforts to rebuild public trust. Importantly, participants linked their work to broader goals such as improving social determinants of health, advancing prevention, and promoting equity. Further this work showed that themes reported by participants in open-ended interviews aligned closely with existing public health frameworks. Although just a pilot, this suggests that existing public health competency statements and frameworks could be used as measures or indicators to help standardize outcome evaluation methods across jurisdictions.

Although presented against the US frameworks of the Strategic Skills, Core Competencies, and Essential Services, the approach used in this study surfaced themes that are consistent with international public health frameworks and could easily be adapted. Further, this approach suggests that the use of qualitative or ‘storytelling’ methods may be valuable in surfacing richness and unanticipated themes. For example, despite the time investment, the rich data we collected allowed us to develop an updated theory of change to guide future evaluation processes at a larger scale. The themes that emerged allowed us to map detail and frameworks to each step in the theory of change, and these frameworks provide possible themes, codes, and indicators for longer-term evaluation processes. Further work by an expanded set of researcher-evaluators will strengthen the framework, the approaches, and most importantly, the evidence.

Looking forward

This study underscores a critical truth: building capacity within the public health workforce is not just beneficial; it is essential. As public health challenges grow more complex, our ability to respond effectively hinges on equipping practitioners with the right skills, frameworks, and confidence to act. Our findings suggest that when capacity-building interventions are thoughtfully designed and delivered, they can catalyze meaningful changes in individual behavior, organizational practice, and community outcomes. But we must go further. To truly advance the field, we need to keep piloting and refining evaluation methods that capture not just what participants learn, but how they apply it—and what that means for public health impact. Developing scalable, grounded evaluation approaches to assess outcomes will be key to sustaining investment, guiding strategy, and ensuring that workforce development efforts are driving us toward a more equitable and resilient public health system.

As in-depth outcomes evaluation is wanting related to public health workforce development efforts (e.g., in contrast to medical education), we invite scholar-practitioners to consider adoption and adaptation of this Theory of Change (Figure 2) to help guide medium and long-term evaluations of public health efforts. In this exploratory use case, we depended on an interview-based protocol and questions to elucidate and validate categories and themes, but as a next step, we anticipate alternative use cases that use these categories and themes to inform larger-scale survey-based evaluation that can more rapidly and thoroughly explore how knowledge and skills (capacities) are being applied in the workplace (capabilities) and for what purpose (changes in conditions), complemented by structured short-answer questions that still invite storytelling. Doing so will support evaluation framed around current public health frameworks (e.g., strategic skills) where skills or performance gaps are known and also help to describe the effects or impacts being seen as a result of expanded capacity. We posit that shared use of this emerging framework for grounded mixed methods evaluation will help develop a collective body of research that shows best practices, value, and impacts of public health capacity-building initiatives. This is especially important given the ubiquity of workforce challenges such as burn-out and erosion of trust. With a shared impact framework, all capacity-building evaluations can start aligning questions related to retention, leadership development, and improved trust.

Limitations

Limitations of this study include lack of generalizability due to both the small sample size, and to purposive recruitment of select learners who participated in PHE. Code frequencies are only a measure of how often a respondent talked about a theme related to their project and therefore may reflect their biases. However, despite being self-reported, the frequency of theme occurrence across contexts may reveal important trends about how capacity translates into action.

Conclusion

Evaluation of workforce capacity-enhancing efforts is crucial. This study reinforces what many in the field intuitively know: when we invest in the public health workforce with intention and structure, we see meaningful returns. While it may be too soon to identify measurable impacts in the cases reported herein, the potential for these is clear. Through PHE, participants not only gained knowledge and skills, but they have also translated those gains into real-world actions that align with the Essential Services of public health. Their stories reflect a shift in mindset, a deepened understanding of systems and equity, and a commitment to community-centered practice. To sustain and scale these gains, the field must continue piloting and refining evaluation methods that capture not only learning outcomes but also real-world application and impact.

While qualitative methods like those used here are resource-intensive, they offer rich insight into how capacity building can catalyze change. As we look ahead, developing scalable, grounded evaluation strategies will be critical—not only to demonstrate impact, but to ensure that our workforce development efforts are truly advancing the mission of public health: to create conditions in which all people can thrive. There are many different public health capacity building initiatives that are funded, developed, and promoted each year and we encourage a shared evaluation framework across all trainings to ensure proper comparison and documentation of material changes to the workforce as a result of successful participation. The pilot evaluation framework presented in this paper, upon further development and refinement, may prove a useful tool in assessing the actions of public health workers, and may help guide future assessments in identifying key actions requisite for effective public health interventions. Developing grounded, scalable approaches to assess workforce development outcomes is essential for guiding investment, informing strategy, and ensuring that public health capacity-building efforts in both the US and other nations are driving meaningful changes.

Data availability statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Ethics statement

The study involving humans was approved by Cornell University Institutional review board. The study was conducted in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. The participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study.

Author contributions

CF: Validation, Methodology, Writing – review & editing, Writing – original draft, Formal analysis, Investigation. JL: Formal analysis, Methodology, Validation, Investigation, Writing – review & editing, Writing – original draft. DL: Conceptualization, Writing – review & editing, Methodology, Supervision, Writing – original draft. GM: Writing – review & editing, Methodology, Writing – original draft, Investigation, Supervision, Conceptualization, Formal analysis, Visualization, Validation.

Funding

The author(s) declare that no financial support was received for the research and/or publication of this article.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The author(s) declare that no Gen AI was used in the creation of this manuscript.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

1. World Health Organization. Global competency and outcomes framework for the essential public health functions. (2024). Geneva: World Health Organization.

2. World Health Organization. Defining essential public health functions and services to strengthen National Workforce Capacity. (2024). Geneva: World Health Organization.

3. DeSalvo, KB, O’Carroll, PW, Koo, D, Auerbach, JM, and Monroe, JA. Public health 3.0: time for an upgrade. Am J Public Health. (2016) 106:621–2. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2016.303063

4. Leider, JP, Mccullough, JM, Singh, SR, Sieger, A, Robins, M, Fisher, JS, et al. Staffing up and sustaining the public health workforce. J Public Health Manag Pract. (2023) 29:E100–7. doi: 10.1097/PHH.0000000000001614

5. McKeever, J, Leider, JP, Alford, AA, and Evans, D. Regional training needs assessment: a first look at high-priority training needs across the United States by region. J Public Health Manag Pract. (2019) 25:S166–76. doi: 10.1097/PHH.0000000000000946

6. DeSalvo, KB, and Wang, YC. Public health 3.0: a new vision requiring a reinvigorated workforce. Pedag Health Promot. (2017) 3:8S–9S. doi: 10.1177/2373379917697334

7. World Health Organization. Essential public health functions: a guide to map and measure National Workforce Capacity. (2024). Geneva: World Health Organization.

8. The Council on Linkages Between Academia and Public Health Practice Core competencies for public health professionals available from: phf.Org/Corecompetencies the council on linkages between academia and public health practice (2021). Washington, D.C.: Public Health Foundation.

9. Meredith, GR, Welter, CR, Risley, K, Seweryn, SM, Altfeld, S, and Jarpe-Ratner, E. A new baseline: master of public health education shifting to meet public health needs. J Public Health Manag Pract. (2022) 28:513–24. doi: 10.1097/PHH.0000000000001537

10. Meredith, GR, Welter, CR, Risley, K, Seweryn, SM, Altfeld, S, and Jarpe-Ratner, EA. Master of public health education in the United States today: building leaders of the future. Public Health Rep. (2023) 138:829–37. doi: 10.1177/00333549221121669

11. Meredith, GR, Welter, CR, Risley, K, Seweryn, SM, Altfeld, S, and Jarpe-Ratner, EA. Levers of change: how to help build the public health workforce of the future. J Public Health Manag Pract. (2023) 29:E90–9. doi: 10.1097/PHH.0000000000001618

12. Jamal, S, Meredith, G, and Eiseman, D. Enhancing public health strategic skills: a guide to high quality trainings. Cornell University health impacts core. (2025). Available online at: https://hdl.handle.net/1813/117798 (Accessed October 2, 2025)

13. Meredith, G, Baker, A, and Patchen, A. Community engaged teaching, research and practice: a catalyst for public health improvement. Mich J Community Serv Learn. (2020) 26:75–100. doi: 10.3998/mjcsloa.3239521.0026.106

14. Meredith, GR, Leong, D, Frost, C, and Travis, AJ. Facilitated asynchronous online learning to build public health strategic skills. J Public Health Manag Pract. (2024) 30:56–65. doi: 10.1097/PHH.0000000000001813

15. de Beaumont Foundation. (2025). PH WINS Dashboard. Available online at: https://www.phwins.org/dashboard/explore?topicId=6&subtopicId=40 (Accessed October 2, 2025)

16. Morrison Lee K, Bosold A, Alvarez C, Rittenhouse D, Felf-Lisk S, Miller F, Palo, C. Surging the Public Health Workforce: Lessons Learned from the COVID-19 Response at State, Tribal, Local, and Territorial Public Health Agencies (2023), Princeton, NJ: Mathematica.

17. DeSalvo, KB, and Kadakia, KT. Public health 3.0 after COVID-19-reboot or upgrade? Am J Public Health. (2021) 111:S179–81. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2021.306501

18. Public Health Foundation. About - TRAIN Learning Network - powered by the Public Health Foundation. (2025). Available online at: https://www.train.org/main/help/about (Accessed July 23, 2025)

19. CDC. Training Effectiveness | Training Development. (2024) Available online at: https://www.cdc.gov/training-development/php/about/evaluate-training-measuring-effectiveness.html (Accessed January 19, 2024)

20. Miner, K, and Allan, S. Future of public workforce training. Health Promot Pract. (2014) 15:10S–3S. doi: 10.1177/1524839913519648

21. Regional Public Health Training Centers. Bureau of Health Workforce. (2022). Available online at: https://bhw.hrsa.gov/funding/regional-public-health-training-centers (Accessed July 23, 2025)

22. Robins, M, Leider, JP, Schaffer, K, Gambatese, M, Allen, E, and Hare Bork, R. PH wins 2021 methodology report. J Public Health Manag Pract. (2023) 29:S35–44. doi: 10.1097/PHH.0000000000001632

23. Balio, CP, Galler, N, Meit, M, Hale, N, and Beatty, KE. Rising to meet the moment: what does the public health workforce need to modernize? J Public Health Manag Pract. (2023) 29:S107–15. doi: 10.1097/PHH.0000000000001624

24. Porter, JM, Giles-Cantrell, B, Schaffer, K, Dutta, EA, and Castrucci, BC. Awareness of and confidence to address equity-related concepts across the US governmental public health workforce. J Public Health Manag Pract. (2023) 29:S87–97. doi: 10.1097/PHH.0000000000001647

25. Owens-Young, JL, Leider, JP, and Bell, CN. Public health workforce perceptions about organizational commitment to diversity, equity, and inclusion: results from PH WINS 2021. J Public Health Manag Pract. (2023) 29:S98–S106. doi: 10.1097/PHH.0000000000001633

26. Halverson, PK. Ensuring a strong public health workforce for the 21st century: reflections on PH WINS 2017. J Public Health Manag Pract. (2019) 25:S1–3. doi: 10.1097/PHH.0000000000000967

27. Resnick, BA, Morlock, L, Diener-West, M, Stuart, EA, Spencer, M, and Sharfstein, JM. PH WINS and the future of public health education. J Public Health Manag Pract. (2019) 25:S10–2. doi: 10.1097/PHH.0000000000000955

28. Gendelman M, Cinnick S, Castillo G. Adapting and aligning public health strategic skills (2021) de Beaumont Foundation, Bethesda, MD.

29. CDC. 10 Essential Public Health Services | Public Health Gateway. (2024). Available online at: https://www.cdc.gov/public-health-gateway/php/about/index.html (Accessed July 23, 2025)

30. Wong, BLH, Siepmann, I, Chen, TT, Fisher, S, Weitzel, TS, Nathan, NL, et al. Rebuilding to shape a better future: the role of young professionals in the public health workforce. Hum Resour Health. (2021) 19:82. doi: 10.1186/s12960-021-00627-7

31. Buys, DR, and Rennekamp, R. Cooperative extension as a force for healthy, rural communities: historical perspectives and future directions. Am J Public Health. (2020) 110:1300–3. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2020.305767

32. Escoffery, C, Lebow-Skelley, E, Udelson, H, Böing, EA, Wood, R, Fernandez, ME, et al. A scoping study of frameworks for adapting public health evidence-based interventions. Transl Behav Med. (2019) 9:1–10. doi: 10.1093/TBM/IBX067

33. Markaki, A, Malhotra, S, Billings, R, and Theus, L. Training needs assessment: tool utilization and global impact. BMC Med Educ. (2021) 21:310. doi: 10.1186/s12909-021-02748-y

34. Czabanowska, K, and Feria, PR. Training needs assessment tools for the public health workforce at an institutional and individual level: a review. Eur J Pub Health. (2024) 34:59–68. doi: 10.1093/eurpub/ckad183

35. Woodward, A, and Rivers, C. Building case investigation and contact tracing programs in US state and local health departments: a conceptual framework. Disaster Med Public Health Prep. (2023) 17:e540. doi: 10.1017/dmp.2023.205

36. Crawford, K, Cordero, SF, and Brasher, S. Evaluating the impact of a community health worker training program. J Health Popul Nutr. (2025) 44:1–9. doi: 10.1186/S41043-025-01011-0/TABLES/2

37. Lima, ME, Maia, PF, Valente, EP, Vezzini, F, and Tamburlini, G. Effectiveness of an action-oriented educational intervention in ensuring long term improvement of knowledge, attitudes and practices of community health workers in maternal and infant health: a randomized controlled study. BMC Med Educ. (2018) 18:1–13. doi: 10.1186/S12909-018-1332-X/FIGURES/3

38. Ramirez, AG, Hu, Y, Kim, H, and Rasmussen, SK. Long-term skills retention following a randomized prospective trial on adaptive procedural training. J Surg Educ. (2018) 75:1589–97. doi: 10.1016/J.JSURG.2018.03.007

39. Ghosh, S, Struminger, BB, Singla, N, Roth, BM, Kumar, A, Anand, S, et al. Appreciative inquiry and the co-creation of an evaluation framework for extension for community healthcare outcomes (ECHO) implementation: a two-country experience. Eval Program Plann. (2022) 92:102067. doi: 10.1016/j.evalprogplan.2022.102067

40. Leong, D, and Meredith, G. National Impacts of Public Health Essentials Training: Evaluation Brief (2024). Ithaca, NY.: Cornell Health Impacts Core.

41. Patton, MQ. Qualitative research and evaluation methods. (2014). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications.

42. Mormina, M, and Pinder, S. A conceptual framework for training of trainers (ToT) interventions in global health. Glob Health. (2018) 14:1–11. doi: 10.1186/S12992-018-0420-3/TABLES/6

43. Plepys, CM, Krasna, H, Leider, JP, Burke, EM, Blakely, CH, and Magaña, L. First-destination outcomes for 2015-2018 public health graduates: focus on employment. Am J Public Health. (2021) 111:475–84. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2020.306038

44. Leider, JP, Yeager, VA, Kirkland, C, Krasna, H, Hare Bork, R, and Resnick, B. The state of the US public health workforce: ongoing challenges and future directions. Annual Rev Public Health Public Health. (2023) 44:323–41. doi: 10.1146/annurev-publhealth

45. Ruggiero, EDi, Papadopoulos, A, and Steinberg, M, Strengthening collaborations at the public health system-academic interface: a call to action. Special Section On COVID-19. (2020);111:921–925. doi: 10.17269/s41997-020-00436-w/Published

46. Bishai, DM, Resnick, B, Lamba, S, Cardona, C, Leider, JP, McCullough, JM, et al. Being accountable for capability-getting public health reform right this time. Am J Public Health. (2022) 112:1374–8. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2022.306975

47. Kulik, PKG, Alperin, M, Todd Barrett, KS, Bekemeier, B, Documet, PI, Francis, KA, et al. The need for responsive workforce development during the pandemic and beyond: a case study of the regional public health training centers. J Public Health Manag Pract. (2024) 30:46–55. doi: 10.1097/PHH.0000000000001835

48. Caron, RM, Neeley, S, Eldredge, C, Goodman, AC, Oerther, DB, Satz, AB, et al. Health in all education: a transdisciplinary learning outcomes framework. Am J Prev Med. (2023) 64:772–9. doi: 10.1016/J.AMEPRE.2022.12.001

Keywords: public health, public health workforce, evaluation, workforce development, outcomes evaluation

Citation: Frost C, Lawless JW, Leong D and Meredith GR (2025) Piloting a framework to explore the impacts of public health workforce capacity-building initiatives. Front. Public Health. 13:1677187. doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2025.1677187

Edited by:

Roksana Mirkazemi, Bahá'í Institute for Higher Education (BIHE), IranReviewed by:

Karin Joann Opacich, University of Illinois Chicago, United StatesEarlene Camarillo, Western Oregon University, United States

Copyright © 2025 Frost, Lawless, Leong and Meredith. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Genevive R. Meredith, Z3JtNzlAY29ybmVsbC5lZHU=

Cheyanna Frost1,2

Cheyanna Frost1,2 Jeanne W. Lawless

Jeanne W. Lawless Genevive R. Meredith

Genevive R. Meredith