- 1College of Physical Education, Hunan Normal University, Changsha, China

- 2Independent Person, Windermere, FL, United States

1 Introduction

Tai Chi, referred to as Taijiquan in Chinese, embodies a unique cultural legacy that bridges ancient Chinese medical thought, martial strategy, and philosophical harmony. Born out of the dual currents of Traditional Chinese Medicine and martial necessity, it has evolved into a globally practiced method of exercise and mindfulness. In this opinion article, we propose that Tai Chi is not merely a relic of the past but a culturally rooted, adaptable, and inclusive fitness modality with increasing relevance for public health promotion across the lifespan. This reflection aligns with current calls to reintegrate culturally embedded physical practices into modern health policy and community-based intervention design (1, 2).

In light of the global burden of physical inactivity and rising chronic diseases, especially among aging populations (3), the urgency to explore movement modalities that are not only effective but also socially and culturally sustainable has never been greater. Tai Chi offers more than physical benefits; it embodies a life philosophy that promotes emotional regulation, social cohesion, and harmony with nature—elements increasingly recognized in holistic health frameworks. As more countries struggle with health disparities, there is a growing interest in accessible, low-cost interventions that provide both physical and psychosocial benefits, positioning Tai Chi as a compelling candidate for public health integration.

2 Healing and martial origins

Historically, Tai Chi emerged during the late Ming and early Qing dynasties, developing from earlier Daoist breathing and movement practices, and evolving into a coherent martial art by Chen Wangting in the 17th century. Its structure reflects the integration of medical qigong, battlefield defense techniques, and philosophical doctrines into a single internal martial art. Over time, different styles—including Chen, Yang, Wu, Sun—emerged. Nonetheless, Tai Chi is founded on a yin–yang cosmology, not only in its flowing movements but in its therapeutic principles. Traditional Chinese Medicine, particularly the concepts of qi, meridians, and internal regulation, informed the early structure of Tai Chi as a health-preserving practice (4). Simultaneously, its martial components were derived from ancient combat systems, informed by tactical texts such as Sun Tzu's The Art of War (5). Tai Chi embodies the balance of softness and strength, yielding and force (6), not merely as physical tactics, but as a philosophy for healthful living.

The yin–yang principle in Tai Chi is not a metaphor; it governs the shifting interplay of motion and stillness, expansion and contraction, attack and retreat. When practicing, the practitioner alternates between weight shifts, rotational spirals, and centering forces that mirror internal organ regulation and emotional equilibrium. This integration of intention, breath, and form forms the physical expression of Chinese cosmology. Moreover, Tai Chi's martial applications, including push hands (tuishou), joint locks, and neutralization techniques, underscore its original function as a defensive art rooted in battlefield pragmatism. These combat strategies, when examined through a modern lens, mirror core principles of biomechanics, proprioception, and reactive balance (7). This integration of martial precision and therapeutic regulation is rare among traditional exercise systems and may explain why Tai Chi has retained clinical utility in contemporary rehabilitation sciences.

This dual origin enabled Tai Chi to serve both defensive and rehabilitative functions. Breathing, posture, and internal awareness coalesce in practice, promoting circulation, postural control, and internal harmony (8). The historical image of the Tai Chi practitioner was not solely that of a fighter, but also of a healer and philosopher—someone who cultivated physical strength, ethical virtue, and mind–body awareness. This ethical dimension was deeply rooted in Confucian values of benevolence and restraint, Taoist ideals of naturalism and non-action, and the moral imperative of martial virtue (9). This inseparability of martial precision and therapeutic intent allowed Tai Chi to emerge as one of the few movement systems with robust historical continuity, integrating biomechanical control with energetic regulation in a coherent framework now highly relevant for rehabilitation and preventive care.

3 From cultural practice to public health asset

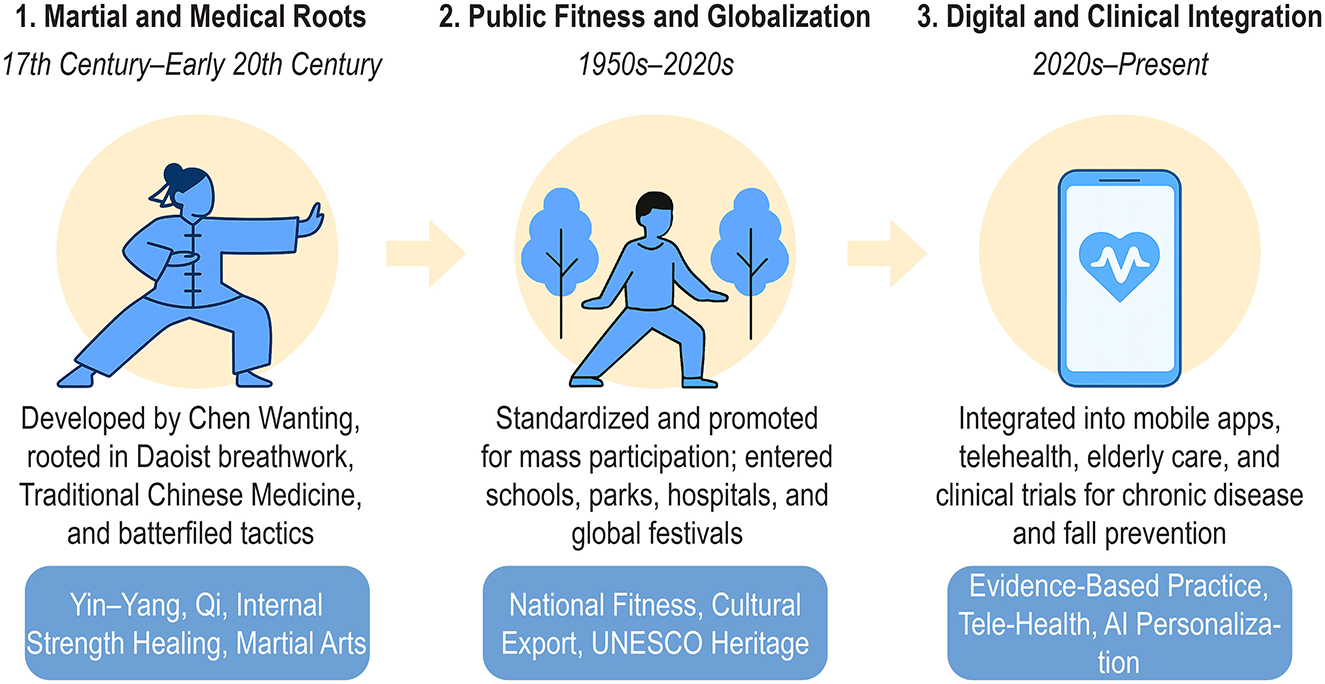

In the 20th century, Tai Chi underwent a profound transformation. As China transitioned through war, reform, and modernization, Tai Chi was adapted for public accessibility and stripped of its combat exclusivity. It entered parks, clinics, schools, and international festivals. This shift mirrors global trends where traditional practices are repurposed for wellness and disease prevention, as illustrated in Figure 1.

Tai Chi has been included in national fitness programs in China, and recently recognized by UNESCO as intangible cultural heritage. These efforts have supported the formal transmission of simplified forms (e.g., 24-form, 42-form Tai Chi) that can be taught to older adults, children, and people with disabilities. This democratization of access has contributed to the longevity and spread of Tai Chi globally.

Scientific evidence supports this transition from tradition to therapy. Physiological investigations have revealed a wide spectrum of health effects. Evidence from cardiovascular and pulmonary research shows that Tai Chi improves baroreflex sensitivity (10) and heart rate variability (11), markers of cardiovascular resilience. Studies have documented enhanced vagal tone and improved autonomic balance in older adults (12). Among patients with hypertension or coronary artery disease, regular Tai Chi practice has been associated with reduced blood pressure, improved lipid metabolism, and endothelial function (13, 14). In respiratory contexts, benefits have been reported among patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (15), where Tai Chi enhances diaphragm strength, tidal volume, and forced expiratory measures. Musculoskeletal adaptations include improved gait speed, balance, and muscular strength (16). In a recent trial conducted by our group among fall-prone postmenopausal women, Tai Chi significantly enhanced balance control and lower limb function (17). This aligns with meta-analytic findings on improved joint mobility and reductions in fall incidence (18). Studies further suggest that long-term practitioners show gains in bone mineral density, particularly in the lumbar spine and femoral neck (19). Metabolic and inflammatory outcomes are equally promising. Tai Chi has been shown to enhance insulin sensitivity, reduce glycated hemoglobin (20), and lower systemic inflammation markers such as C-reactive protein and Tumor Necrosis Factor alpha (21). These outcomes are relevant for chronic disease prevention, particularly in the context of aging.

Evidence also supports psychological benefits. Randomized controlled trials have demonstrated moderate-to-large improvements in depressive symptoms, anxiety, and general wellbeing (22). Mechanistically, these outcomes are linked to parasympathetic activation and reductions in cortisol levels via controlled breathing and meditative movement. Clinical improvements in sleep quality have also been observed, especially in older adults and oncology patients, where Tai Chi interventions improved both subjective and objective sleep metrics (23). Further, preliminary neuroimaging studies suggest enhanced connectivity in brain regions involved in executive function and attentional control following regular practice (24, 25), offering potential value in preventing cognitive decline and mental resilience.

Beyond physical and psychological effects, Tai Chi also nurtures a sense of spiritual connectedness. Rooted in Daoist cosmology and Confucian ethics (26, 27), it fosters a meditative presence and inner harmony. Many practitioners report feelings of spiritual peace, existential grounding, and a sense of unity with nature (28–30), elements that may contribute to enhanced wellbeing and life satisfaction, especially in aging populations or those coping with chronic illness.

Taken together, this structured evidence ranging from physiological regulation to psychological resilience positions Tai Chi as an evidence-based and culturally adaptable approach for enhancing public health.

4 Modern relevance and global reach

Today, more than 300 million individuals practice Tai Chi globally (31), including an estimated 1.5 million in the United States alone, most of whom are non-Chinese (32). This broad uptake across continents is not merely a cultural curiosity—it reflects Tai Chi's unique ability to address universal public health concerns while transcending cultural boundaries. Its meditative movement, emphasis on balance, and low-impact nature resonate with diverse populations facing similar health challenges: aging, stress-related illness, sedentary lifestyles, and the erosion of social cohesion.

Tai Chi is particularly well-suited to fill gaps in physical activity engagement among older adults and individuals with chronic disease or mobility limitations. Unlike high-intensity fitness trends that may alienate these populations, Tai Chi offers a gentle, scalable, and sustainable alternative that aligns with global calls for age-friendly health promotion strategies. Its adaptability across cultures lies in its non-dogmatic approach: while rooted in Chinese philosophy, its practice does not require spiritual affiliation or prior cultural familiarity. Practitioners in Europe, the Americas, and Southeast Asia have incorporated Tai Chi into local healthcare systems, rehabilitation programs, senior centers, and even public school curricula (33–35). In addition to its physical benefits, Tai Chi supports broader social determinants of health. Its emphasis on group practice fosters social inclusion, intergenerational interaction, and community identity (36–38), features that are critical in societies grappling with loneliness, digital disconnection, and mental health crises. In urban environments, where access to green space is often limited and public health infrastructure strained, Tai Chi's minimal spatial and equipment requirements make it an ideal intervention for parks, rooftops, and community halls. Moreover, Tai Chi provides a counter-narrative to dominant Western fitness models that prioritize intensity, competition, and external body aesthetics. It encourages a somatic awareness that values internal balance, mindful movement, and long-term sustainability, principles increasingly recognized in trauma-informed care, integrative medicine, and mental health interventions. As such, its global relevance extends beyond clinical efficacy to embody an alternative vision of health and human flourishing.

By offering a culturally rich yet pragmatically accessible form of movement, Tai Chi has the potential to serve as a bridge between traditional wisdom and modern public health, between East and West, and between individual and collective wellbeing. Its success in international contexts demonstrates that culturally grounded practices, when supported by evidence and adapted respectfully, can play a transformative role in global health promotion.

5 A call to action: reclaiming cultural heritage in public health

Current physical activity frameworks often emphasize frequency, intensity, and duration as key parameters for health promotion. However, these metrics alone may overlook important sociocultural and motivational factors that determine long-term engagement. Traditional practices such as Tai Chi, while not always designed for maximal exertion, offer a contextually meaningful and sustainable form of movement that resonates with diverse populations.

To maximize Tai Chi's contribution to modern public health, future strategies should go beyond conventional clinical trials or park-based programs. The next frontier lies in leveraging digital health platforms to scale its accessibility and cultural relevance. For example, multilingual video-based programs featuring certified instructors and tailored to diverse age groups could be integrated into mobile apps, wearable ecosystems, and telehealth services. These platforms could incorporate adaptive algorithms that tailor practice intensity based on real-time biometric data (e.g., heart rate, fall risk profiles), personalized progression, and community engagement features that support adherence, particularly in rural, underserved, or socially isolated populations. Such innovations would allow Tai Chi to be practiced anywhere, reducing barriers in low-resource settings or among mobility-constrained individuals.

Real-world implementation of Tai Chi within digital and community frameworks is already underway in several regions. In mainland China, the “National Fitness Platform” app developed by the General Administration of Sport includes guided Taijiquan video modules for different age groups, with millions of registered users accessing them for daily exercise. In the United States, Tai Chi in the “Moving for Better Balance” program—endorsed by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention—has been adopted in over 40 states, especially for fall prevention in older adults (39). Digital iterations include hybrid models like tele-Tai Chi classes via Zoom, which were widely implemented during the COVID-19 pandemic to ensure continuity in movement therapy for vulnerable populations (40). In the United Kingdom, the National Health Service has piloted community-based Tai Chi programs in public parks and GP (exercise) referral schemes as part of holistic fall prevention strategies (41). These examples illustrate not only feasibility but also sustained adherence and measurable health outcomes, providing practical models for broader integration.

Building on these efforts, cross-cultural adaptation studies are also essential. Rather than treating Tai Chi as a static tradition, researchers and practitioners should explore how local contexts can reshape its instructional language, delivery format, and group dynamics while preserving core principles. Comparative studies examining Tai Chi alongside conventional aerobic or resistance training can clarify its differential effects on mental health, neuromotor coordination, and immune function.

Moreover, governments and global health agencies could support pilot programs that blend traditional movement with modern metrics, such as heart rate variability, sleep monitoring, and fall risk assessment. These data-driven initiatives can generate the translational evidence needed to legitimize and integrate Tai Chi into policy-supported health promotion models.

In short, reclaiming Tai Chi as a living, evolving cultural asset requires that we do not simply advocate for its use—we must innovate how it is delivered, evaluated, and contextualized for contemporary global needs.

6 Discussion

Tai Chi's journey—from ancient battlefield and healing hall to global public parks—is a testament to its adaptability and enduring relevance. As we seek innovative ways to promote lifelong physical activity, especially among aging and marginalized populations, culturally meaningful practices like Tai Chi should not be overlooked. The legacy of Tai Chi rests not just in its techniques but in its worldview: that strength lies in flexibility, that health arises from balance, and that wellness is achieved not through domination but through harmony. In a fragmented and fast-moving world, Tai Chi invites us to slow down, reconnect with our bodies, and cultivate equilibrium—within ourselves, our communities, and the natural world. By reintegrating such practices into our public health systems, we do not merely preserve cultural heritage; we actively expand the definition of fitness to one that is more human-centered, inclusive, and sustainable. This is the future Tai Chi points us toward: one in which health is not imposed, but harmonized. The synthesis of empirical validation and cultural relevance embodied in Tai Chi offers a scalable, culturally grounded strategy to support inclusive, community-based public health solutions worldwide.

Author contributions

DL: Conceptualization, Writing – original draft. BZ: Funding acquisition, Writing – review & editing. ZW: Writing – original draft. YZ: Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declare that financial support was received for the research and/or publication of this article. This study is supported by the National Social Science Foundation of China under grant number 24FTYB007 (holder by Prof. Zhou Bo).

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The author(s) declare that no Gen AI was used in the creation of this manuscript.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Publisher's note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

1. Brown D, Leledaki A. Eastern movement forms as body-self transforming cultural practices in the west: towards a sociological perspective. Cult Sociol. (2010) 4:123–54. doi: 10.1177/1749975509356866

2. Langweiler MJ. Evidence-based medicine and the potential for inclusion of non-biomedical health systems: the case for Taijiquan. Front Sociol. (2021) 5:618167. doi: 10.3389/fsoc.2020.618167

3. Fang EF, Scheibye-Knudsen M, Jahn HJ Li J, Ling L, Guo H, Zhu X, et al. A research agenda for aging in China in the 21st century. Ageing Res Rev. (2015) 24:197–205. doi: 10.1016/j.arr.2015.08.003

4. Fogaça LZ, Portella CFS, Ghelman R, Abdala CVM, Schveitzer MC. Mind-body therapies from traditional Chinese medicine: evidence map. Front Public Health. (2021) 9:659075. doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2021.659075

5. Luo C. Strategy and tactics: Taijiquan and the art of war. J Beijing Sport Univ. (2004) 27:288–9.

6. Law N-Y, Li JX. Biomechanics analysis of seven tai chi movements. Sports Med Health Sci. (2022) 4:245–52. doi: 10.1016/j.smhs.2022.06.002

7. Hua H, Zhu D, Wang Y. Comparative study on the joint biomechanics of different skill level practitioners in chen-style tai chi punching. Int J Environ Res Public Health. (2022) 19:5915. doi: 10.3390/ijerph19105915

8. Liu H, Nichols C, Zhang H. Understanding Yin-Yang philosophic concept behind tai chi practice. Holist Nurs Pract. (2023) 37:E75–82. doi: 10.1097/HNP.0000000000000598

9. Wang Z-D, Wang F-Y. Ternary Taiji Models of the traditional Chinese self: centered on confucian, taoist, and buddhist cultures. J Humanist Psychol. (2021) 0:00221678211016957. doi: 10.1177/00221678211016957

10. Sato S, Makita S, Uchida R, Ishihara S, Masuda M. Effect of tai chi training on baroreflex sensitivity and heart rate variability in patients with coronary heart disease. Int Heart J. (2010) 51:238–41. doi: 10.1536/ihj.51.238

11. Larkey L, James D, Vizcaino M, Kim SW. Effects of tai chi and Qigong on heart rate variability: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Heart Mind. (2024) 8:310–24. doi: 10.4103/hm.HM-D-24-00045

12. Lu W-A, Kuo C-D. The effect of tai chi chuan on the autonomic nervous modulation in older persons. Med Sci Sports Exerc. (2003) 35:1972–6. doi: 10.1249/01.MSS.0000099242.10669.F7

13. Yeh GY, Wang C, Wayne PM, Phillips R. Tai chi exercise for patients with cardiovascular conditions and risk factors: a systematic review. J Cardiopulm Rehabil. (2009) 29:152–60. doi: 10.1097/HCR.0b013e3181a33379

14. Luk T-H, Dai Y-L, Siu C-W, Yiu K-H, Chan H-T, Lee SWL Li S-W, et al. Effect of exercise training on vascular endothelial function in patients with stable coronary artery disease: a randomized controlled trial. Eur J Prev Cardiol. (2012) 19:830–9. doi: 10.1177/1741826711415679

15. Niu R, He R, Luo B-l, Hu C. The effect of tai chi on chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: a pilot randomised study of lung function, exercise capacity and diaphragm strength. Heart Lung Circ. (2014) 23:347–52. doi: 10.1016/j.hlc.2013.10.057

16. Wehner C, Blank C, Arvandi M, Wehner C, Schobersberger W. Effect of tai chi on muscle strength, physical endurance, postural balance and flexibility: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ Open Sport Exerc Med. (2021) 7:e000817. doi: 10.1136/bmjsem-2020-000817

17. Bai X, Xiao W, Soh KG, Zhang Y. A 12-week Taijiquan practice improves balance control and functional fitness in fall-prone postmenopausal women. Front Public Health. (2024) 12:1415477. doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2024.1415477

18. Huang Z-G, Feng Y-H, Li Y-H, Lv C-S. Systematic review and meta-analysis: tai chi for preventing falls in older adults. BMJ Open. (2017) 7:e013661. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2016-013661

19. Zhou Y, Zhao Z-H, Fan X-H, Li W-H, Chen Z. Different training durations and frequencies of tai chi for bone mineral density improvement: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Evid Based Complementary Altern Med. (2021) 2021:6665642. doi: 10.1155/2021/6665642

20. Xinzheng W, Fanyuan J, Xiaodong W. The effects of tai chi on glucose and lipid metabolism in patients with diabetes mellitus: a meta-analysis. Complement Ther Med. (2022) 71:102871. doi: 10.1016/j.ctim.2022.102871

21. Shu C, Feng S, Cui Q, Cheng S, Wang Y. Impact of tai chi on CRP, TNF-alpha and IL-6 in inflammation: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Ann Palliat Med. (2021) 10:7468–78. doi: 10.21037/apm-21-640

22. Yin J, Yue C, Song Z, Sun X, Wen X. The comparative effects of tai chi versus non-mindful exercise on measures of anxiety, depression and general mental health: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Affect Disord. (2023) 337:202–14. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2023.05.037

23. Takemura N, Cheung DST, Fong DYT, Lee AWM, Lam T-C, Ho JC-M, et al. Effectiveness of aerobic exercise and tai chi interventions on sleep quality in patients with advanced lung cancer: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Oncol. (2024) 10:176–84. doi: 10.1001/jamaoncol.2023.5248

24. Cui L, Yin H, Lyu S, Shen Q, Wang Y, Li X, et al. Tai chi chuan vs general aerobic exercise in brain plasticity: a multimodal MRI study. Sci Rep. (2019) 9:17264. doi: 10.1038/s41598-019-53731-z

25. Tao J, Liu J, Egorova N, Chen X, Sun S, Xue X, et al. Increased hippocampus–medial prefrontal cortex resting-state functional connectivity and memory function after tai chi chuan practice in elder adults. Front Aging Neurosci. (2016) 8:25. doi: 10.3389/fnagi.2016.00025

26. Brown D. Taoism Through Tai Chi Chuan: Physical Culture as Religious or Holistic Spirituality? Spirituality across Disciplines: Research and Practice. Springer: New York (2016). p. 317–28. doi: 10.1007/978-3-319-31380-1_24

27. Cibotaru V. The spiritual features of the experience of qi in Chinese martial arts. Religions. (2021) 12:836. doi: 10.3390/rel12100836

28. Bradshaw A, Phoenix C, Burke SM. Living in the mo(ve)ment: an ethnographic exploration of hospice patients' experiences of participating in tai chi. Psychol Sport Exerc. (2020) 49:101687. doi: 10.1016/j.psychsport.2020.101687

29. Hjortborg SK, Ravn S. Practising bodily attention, cultivating bodily awareness – a phenomenological exploration of tai chi practices. Qual Res Sport Exerc Health. (2020) 12:683–96. doi: 10.1080/2159676X.2019.1662475

30. Chandran S. Integrating transactional analysis and tai chi for synergy and spirituality. Trans Anal J. (2019) 49:114–30. doi: 10.1080/03621537.2019.1577336

31. United Nations. China's centuries-old martial art tai chi (taijiquan) inscribed in UNESCO's cultural heritage list; tai chi joins yoga as world's best body-mind health exercises (2020). Available online at: https://theunitednationscorrespondent.com/chinas-centuries-old-martial-art-tai-chi-taijiquan-inscribed-in-unescos-cultural-heritage-list-tai-chi-joins-yoga-as-worlds-best-body-mind-health-exercises/ (Accessed December 21, 2020).

32. Shi H, Guo Y. Hot spots and content analysis of american taijiquan research in the past 20 years. Chin Sport Sci Technol. (2018) 54:3–10.

33. Manor B, Lough M, Gagnon MM, Cupples A, Wayne PM, Lipsitz LA. Functional benefits of tai chi training in senior housing facilities. J Am Geriatr Soc. (2014) 62:1484–9. doi: 10.1111/jgs.12946

34. Ory MG, Smith ML, Parker EM, Jiang L, Chen S, Wilson AD, et al. Fall prevention in community settings: results from implementing tai chi: moving for better balance in three states. Front Public Health. (2015) 2:258. doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2014.00258

35. Webster CS, Luo AY, Krägeloh C, Moir F, Henning M. A systematic review of the health benefits of tai chi for students in higher education. Prev Med Rep. (2016) 3:103–12. doi: 10.1016/j.pmedr.2015.12.006

36. Hallisy KM. Tai Chi beyond balance and fall prevention: health benefits and its potential role in combatting social isolation in the aging population. Curr Geri Rep. (2018) 7:37–48. doi: 10.1007/s13670-018-0233-5

37. Bao X, Jin K. The beneficial effect of tai chi on self-concept in adolescents. Int J Psychol. (2015) 50:101–5. doi: 10.1002/ijop.12066

38. Kim EH, Chee KH, DeStefano C, Broome A, Bell B. Retention in intergenerational exercise classes for older adults: a mixed-method research study. Educ Gerontol. (2021) 47:269–84. doi: 10.1080/03601277.2021.1923132

39. Li F, Harmer P, Eckstrom E, Fitzgerald K, Chou L-S, Liu Y. Effectiveness of tai ji quan vs multimodal and stretching exercise interventions for reducing injurious falls in older adults at high risk of falling: follow-up analysis of a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Netw Open. (2019) 2:e188280. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2018.8280

40. Gomaa S, West C, Lopez AM, Zhan T, Schnoll M, Abu-Khalaf M, et al. Telehealth-delivered tai chi intervention (taichi4joint) for managing aromatase inhibitor–induced arthralgia in patients with breast cancer during COVID-19: longitudinal pilot study. JMIR Form Res. (2022) 6:e34995. doi: 10.2196/34995

Keywords: aging, digital health, exercise, fall prevention, fitness, physical activity

Citation: Liu D, Zhou B, Wen Z and Zhang Y (2025) From healing and martial roots to global health practice: reimagining Tai Chi (Taijiquan) in the modern public fitness movement. Front. Public Health 13:1677470. doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2025.1677470

Received: 31 July 2025; Accepted: 14 August 2025;

Published: 02 September 2025.

Edited by:

Selcuk Akpinar, Nevsehir University, TürkiyeReviewed by:

Ozkan Isik, Balikesir University, TürkiyeCopyright © 2025 Liu, Zhou, Wen and Zhang. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Bo Zhou, emhvdWJvQGh1bm51LmVkdS5jbg==; Zhixiang Wen, NDU3MjU0NzU0QHFxLmNvbQ==

Dinghua Liu1

Dinghua Liu1 Bo Zhou

Bo Zhou Zhixiang Wen

Zhixiang Wen Yang Zhang

Yang Zhang