- 1Acupuncture and Tuina College, Chengdu University of Traditional Chinese Medicine, Chengdu, Sichuan, China

- 2School of Health and Rehabilitation, Chengdu University of Traditional Chinese Medicine, Chengdu, Sichuan, China

Objective: As a prominent complementary and alternative therapy, acupuncture is widely used to treat Tourette syndrome in children. This review aims to evaluate its clinical efficacy and provide evidence-based support for acupuncture in pediatric Tourette syndrome.

Methods: We systematically searched six databases: China National Knowledge Infrastructure, Wanfang Database, VIP Information Chinese Journal Service Platform, PubMed, Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials, and Embase, from their inception to 10 April 2025. Randomized controlled trials comparing acupuncture alone versus medication, or acupuncture plus other treatments versus other treatments alone, for children tic disorder were included.

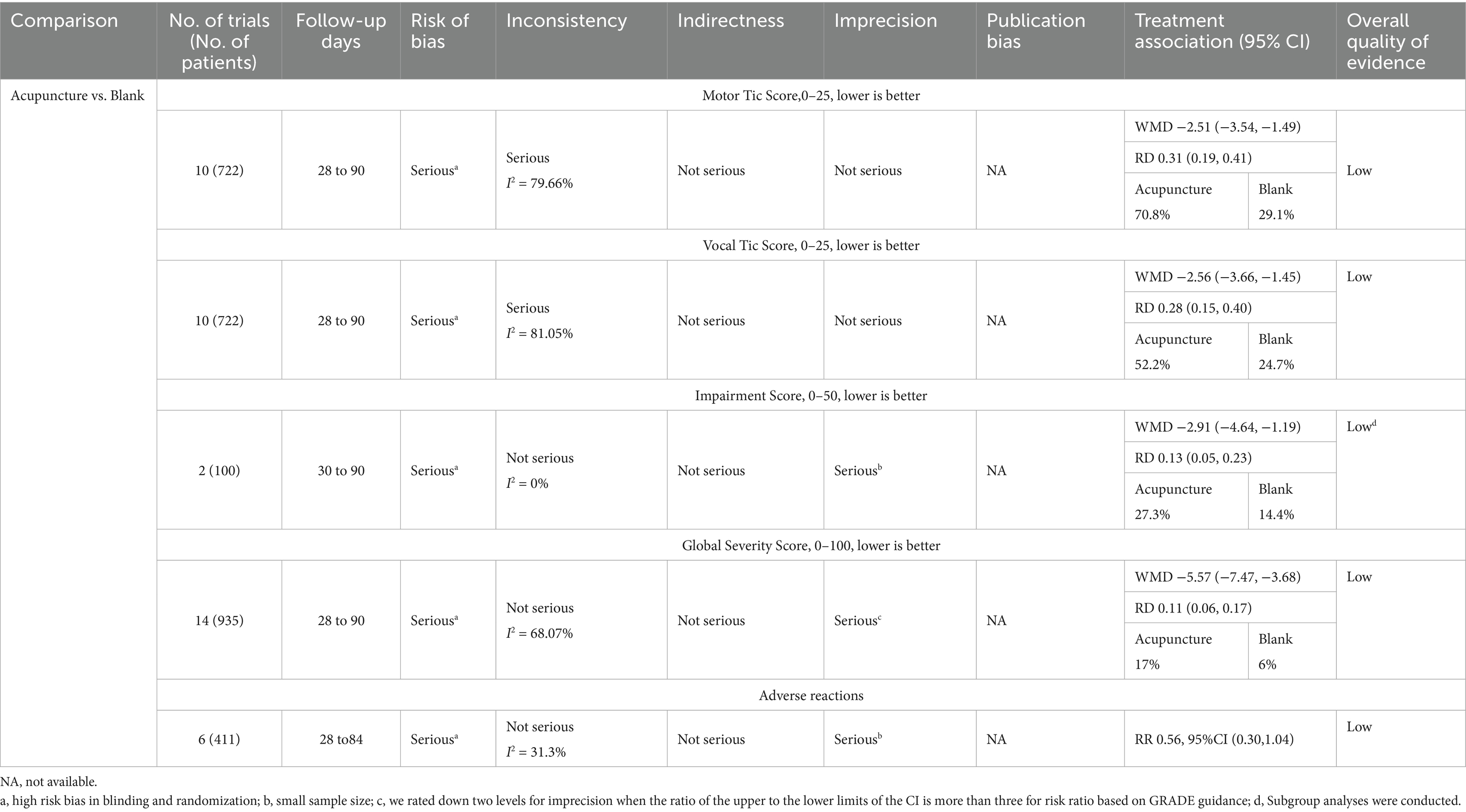

Results: Thirty-two studies were included, with 2,201 participants. Acupuncture may be more effective in improving motor tics symptoms than dopamine agonist [WMD −3.04, 95% CI (−3.77, −2.31), RD 0.38 (0.29, 0.46)], slightly improving vocal tics [WMD −2.39, 95% CI (−3.51, −1.26), RD 0.21 (0.10, 0.35)] and overall condition [WMD −5.56, 95% CI (−7.28, −3.83), RD 0.05 (0.02, 0.09)], but having little difference in functional impairment [WMD −2.27, 95% CI (−3.58, −0.96), RD 0.14 (0.09, 0.20)]. Acupuncture may be more effective than blank treatment on basis of other therapies in improving motor tics [WMD −2.51, 95% CI (−3.54, −1.49), RD 0.31 (0.19, 0.41)] and vocal tics [WMD −2.56, 95% CI (−3.66, −1.45), RD 0.28 (0.15, 0.40)], but slightly improving functional impairment [WMD −2.91, 95% CI (−4.64, −1.19), RD 0.13 (0.05, 0.23)] and overall symptom severity [WMD −5.57, 95% CI (−7.47, −3.68), RD 0.11 (0.06, 0.17)].

Conclusion: Chinese children with Tourette syndrome using acupuncture may experience more improvement in motor tics symptoms than those using dopamine agonist. Acupuncture combined with other therapies may bring Chinese children with Tourette syndrome symptom relief in motor tics and vocal tics more than those alone. All results are supported by low-quality evidence.

Systematic review registration: https://www.crd.york.ac.uk/PROSPERO/view/CRD42023444312, identifier CRD42023444312.

1 Introduction

Tourette’s syndrome (TS) is a prevalent chronic neuropsychiatric disorder representing a distinct chronic subtype of tic disorders: onset occurs before age 18, with a duration exceeding 1 year; it involves both motor and vocal tics, which may occur asynchronously. This distinguishes it from chronic tic disorders presenting solely with one tic type and transient tic disorders lasting less than 1 year. Patients typically present with semivoluntary muscle twitching in the head, face, shoulders, neck, and limbs, alongside abnormal vocalizations. These symptoms are frequently accompanied by psychological comorbidities such as attention deficit hyperactivity disorder and obsessive-compulsive disorder (1). The causes and mechanisms of the disease remain unclear, and treatment primarily involves symptomatic drug therapy (2). Long-term medication use often leads to adverse neurological reactions, such as blurred vision, drowsiness, fatigue, nausea, and vomiting, making it difficult for children to comply with long-term medication regimens, resulting in suboptimal treatment outcomes (3). Acupuncture is a non-pharmacological therapy for neurological disorders. Research indicates that acupuncture has demonstrated substantial efficacy in treating such conditions, including central nervous system disorders such as stroke and migraine, and peripheral nervous system disorders such as Bell’s palsy and trigeminal neuralgia. With its minimal adverse reactions, acupuncture is gaining increasing acceptance among practitioners and patients alike (4, 5). This study aims to evaluate the clinical efficacy of acupuncture in treating children with TS and provide evidence-based medical for acupuncture treatment of childhood Tourette syndrome.

2 Methods

2.1 Literature search

We followed the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines (6) to report our systematic review and registered it in PROSPERO (registration number: CRD42023444312). The search strategy is as follows: (1) Database Search: China National Knowledge Infrastructure, Wanfang Data Online Knowledge Service Platform, VIP Information Chinese Journal Service Platform, PubMed, Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials, and Embase Database. (2) Manual Search: (1) China Clinical Trials Registry (search terms: Tourette syndrome AND acupuncture); (2) Included literature from published systematic reviews and their reference lists. The search was conducted up to 10 April 2025, with no language restrictions. (Database search terms and search results are listed in Supplementary Table 1).

2.2 Literature screen and data extraction

After removing duplicate documents using Endnote 21 software, four researchers (QQZ, ZCL, ZYH, JT) independently read the titles, abstracts, and full texts of all documents to determine the final documents to be included. In case of disagreement, the issue was resolved through discussion or by the third party (PT, LL). Data extraction was conducted independently by four researchers (QQZ, ZCL, ZYH, JT) in a blinded fashion. The extracted data included: literature characteristics (title, authors, publication year, age, disease duration, sample size, intervention and control measures), methodological information (randomization method, allocation concealment, use of blinding, loss to follow-up), and outcome measures (tics, vocal tics, functional impairment, adverse reactions). After extraction, we applied the following inclusion and exclusion criteria.

Inclusion criteria: (1) patients diagnosed with TS according to the diagnostic criteria of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fifth Edition (DSM-5) (7), with a disease duration of over 1 year and no tic-free periods exceeding 2 months, aged <18 years,(2) acupuncture vs. western medicine, acupuncture vs. blank control, with a follow-up ≥4 weeks, (3) randomized controlled trial (RCT), (4) primary outcomes involved tic symptoms, coprolalia symptoms, and functional impairment, and secondary outcomes were adverse reactions.

Exclusion criteria: (1) Semi-randomized controlled trials; (2) Tics attributable to other neurological disorders.

2.3 Risk of bias assessment

The risk of bias in the included RCTs was assessed independently by two reviewers (QQZ, ZCL) using the Cochrane Risk of Bias 1.0 tool (8, 9). The following domains were rated: (1) random sequence generation; (2) allocation concealment; (3) blinding of participants and personnel; (4) blinding of outcome assessment; (5) incomplete outcome data; (6) selective reporting; and (7) other sources of bias.

2.4 Data analysis

Continuous variables were analyzed using the weighted mean difference (WMD) and corresponding confidence interval (95% CI); binary variables were analyzed using the relative risk (RR) and 95% CI. All meta-analyses were performed using a random-effects model in Stata 17 software. Heterogeneity was assessed using the I2 value and Q test, with an I2 value ≥ 50% indicating high heterogeneity. Subgroup analysis was conducted to identify sources of heterogeneity. To better interpret the clinical significance of effect sizes, we defined an effect size of ≥30% reduction from baseline as the minimal clinically important difference (MCID), and calculated the risk difference (RD) between groups to quantify between-group differences.

2.5 Certainty of evidence

We used the GRADE (Grading of Recommendations, Assessment, Development, and Evaluation) method to assess the certainty of evidence for each outcome (10). Evidence from RCTs started at high quality but can be downgraded to high, moderate, low, or very low quality based on factors such as risk of bias, consistency, directness, precision, and publication bias.

3 Results

3.1 Literature screening

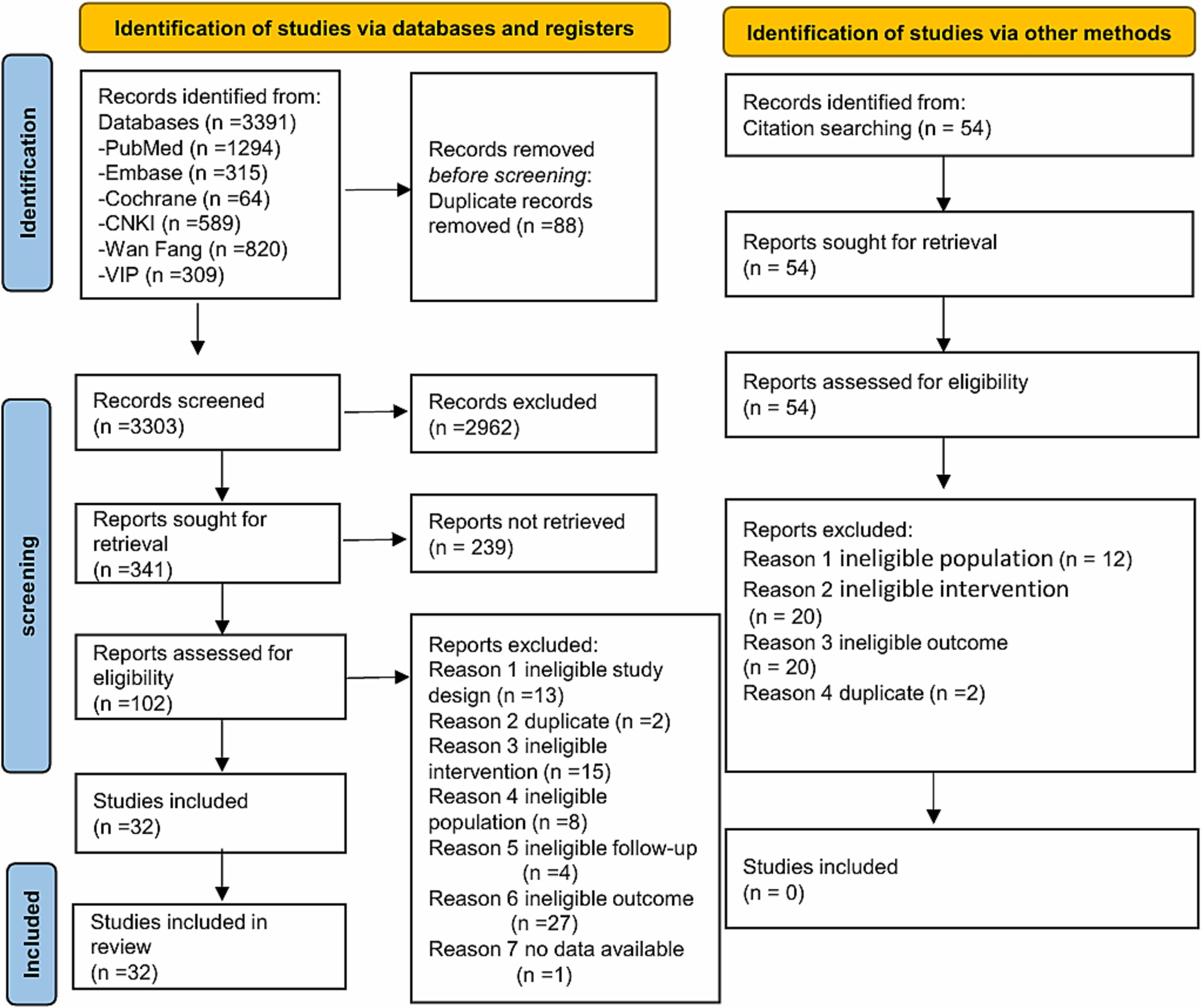

Database search yielded 3,391 records. Manual search yielded 54 records from 11 published systematic reviews (11–21). Thirty-two studies were ultimately included (Figure 1).

3.2 Characteristics of included studies

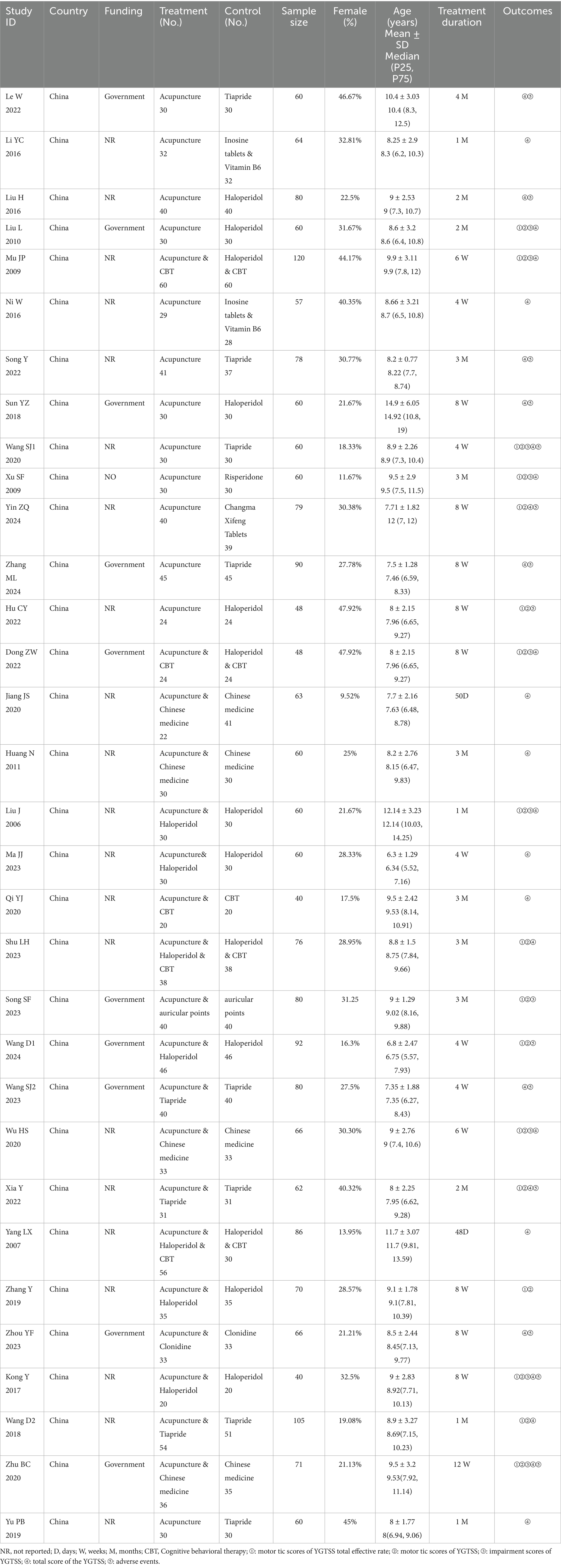

Thirty-two studies (22–52) were included, involving 2,201 patients, with 28.17% being female. All included studies were conducted in China, and 10 studies (22, 25, 29, 34, 36, 42–44, 48, 51) received funding support. Among the 25 studies reporting participants’ specific ages, the average age of participants was 8.84 years, with the shortest intervention duration being 28 days and the longest being 120 days. This included 15 acupuncture vs. medication control studies (22–31, 33–36, 52), 11 acupuncture combined with medication vs. medication alone control studies (38, 39, 41, 43, 44, 46–50, 52, 53), 4 studies comparing acupuncture combined with Chinese herbal medicine vs. Chinese herbal medicine alone (32, 37, 45, 51), 1 study comparing acupuncture combined with ear acupuncture vs. ear acupuncture alone (42), and 1 study comparing acupuncture combined with cognitive behavioral therapy vs. cognitive behavioral therapy alone (40). Fourteen studies (22, 24, 28–30, 33–35, 43, 44, 46, 48, 49, 51) reported adverse reactions. The detailed information of the included studies can be seen in Table 1.

3.3 Risk of bias

All of the 32 included studies showed that 26 (81%) had adequate randomization sequence generation, 3 (9%) had adequate allocation concealment (22, 35, 36), and 3 (9%) had blinding of data collectors, data processors, and data analysts (22, 35, 36). Six studies reported patient attrition (27, 32, 37, 48, 51, 53), but the attrition rates did not exceed 20% in any case (Supplementary Table 3).

3.4 Acupuncture vs. medicine

3.4.1 Motor tic symptoms

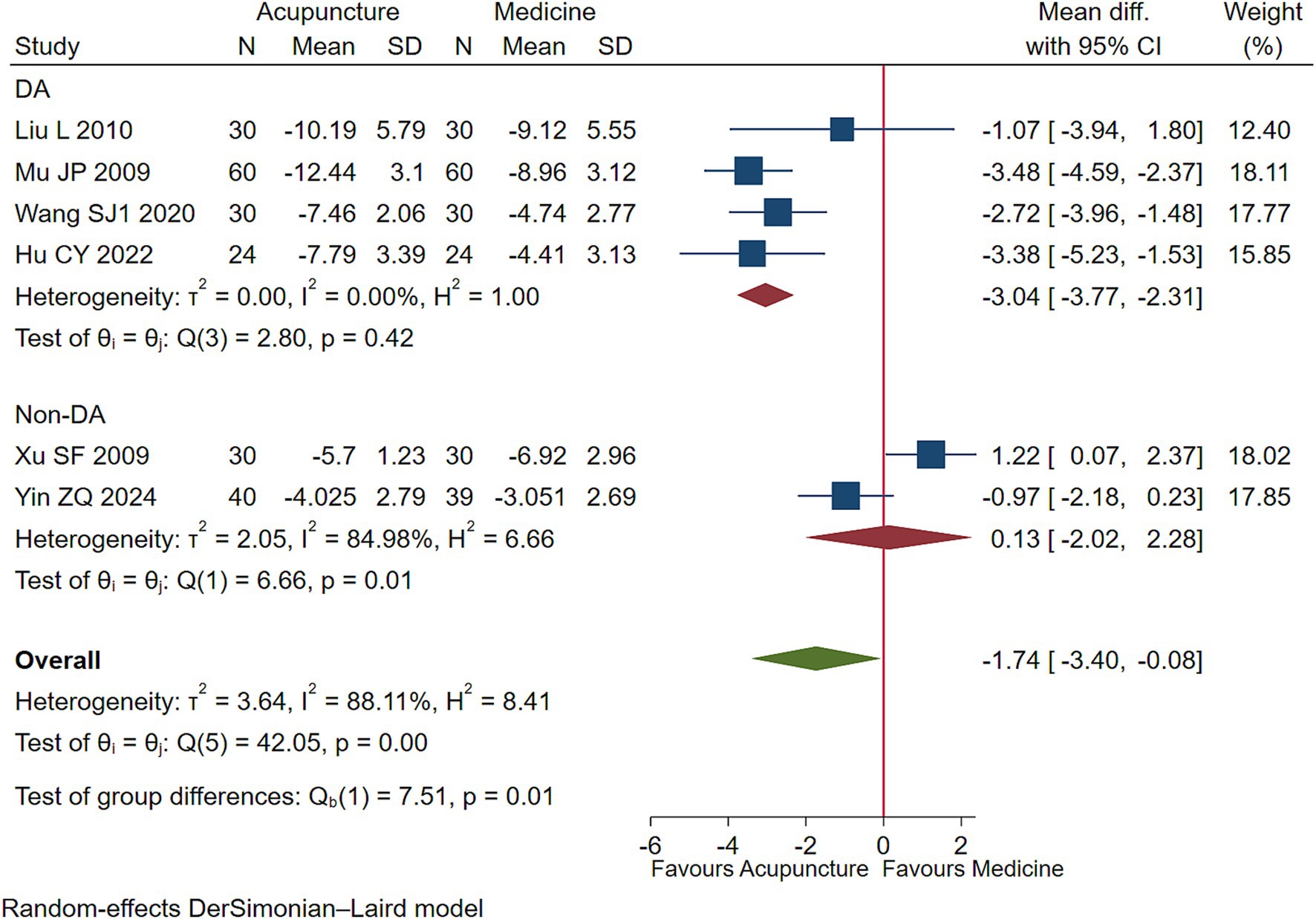

Low-quality evidence (4 studies, 288 participants) suggested that acupuncture may lessen motor tics symptoms in children with TS than DA [WMD −3.04, 95% CI (−3.77, −2.31), RD 0.38 (0.29, 0.46) (Figure 2; Table 2)] (25, 26, 30, 35).

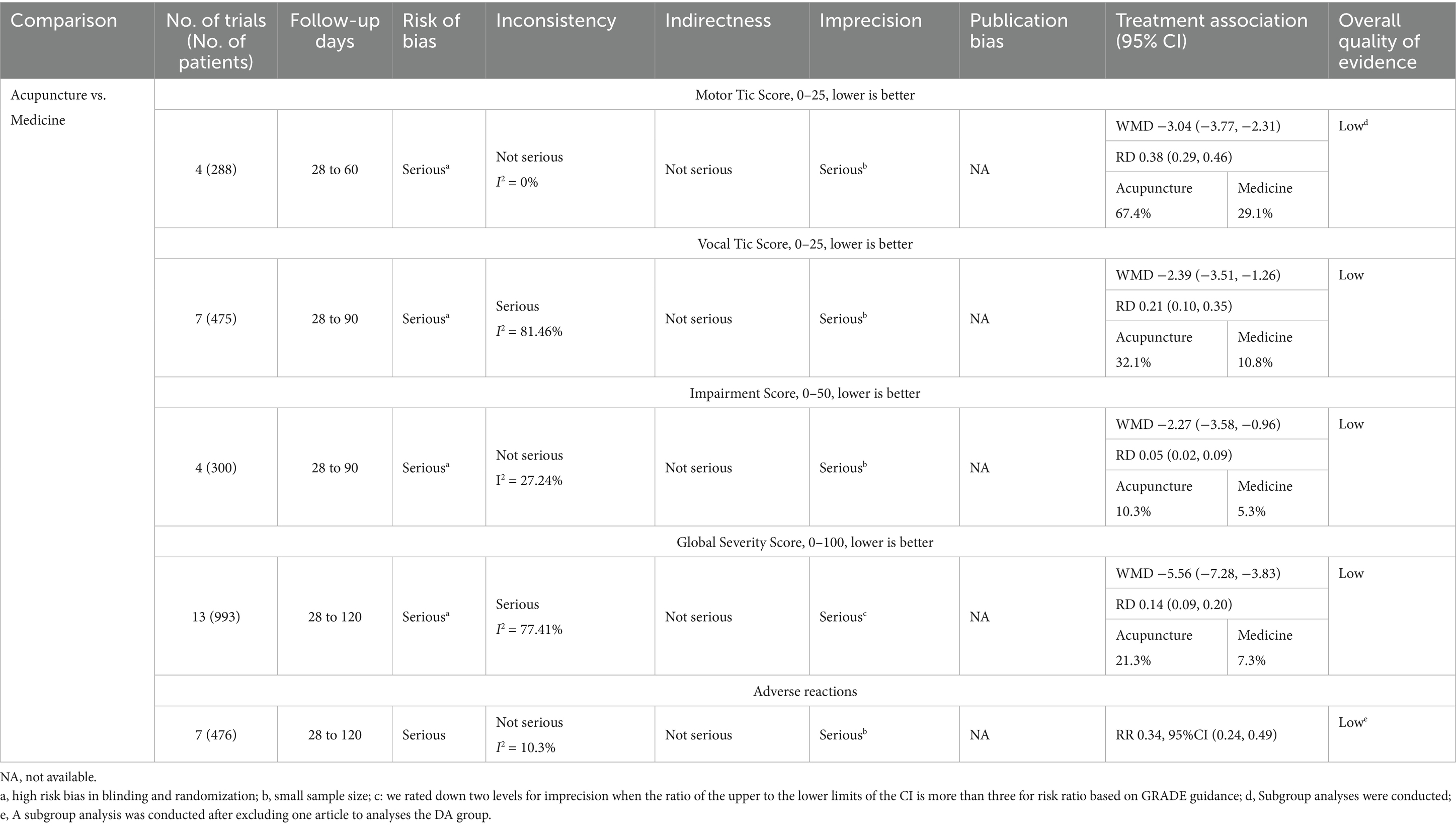

Table 2. GRADE evidence quality rating of the clinical efficacy of acupuncture versus medicine therapy for children with TS.

3.4.2 Vocal tic symptoms

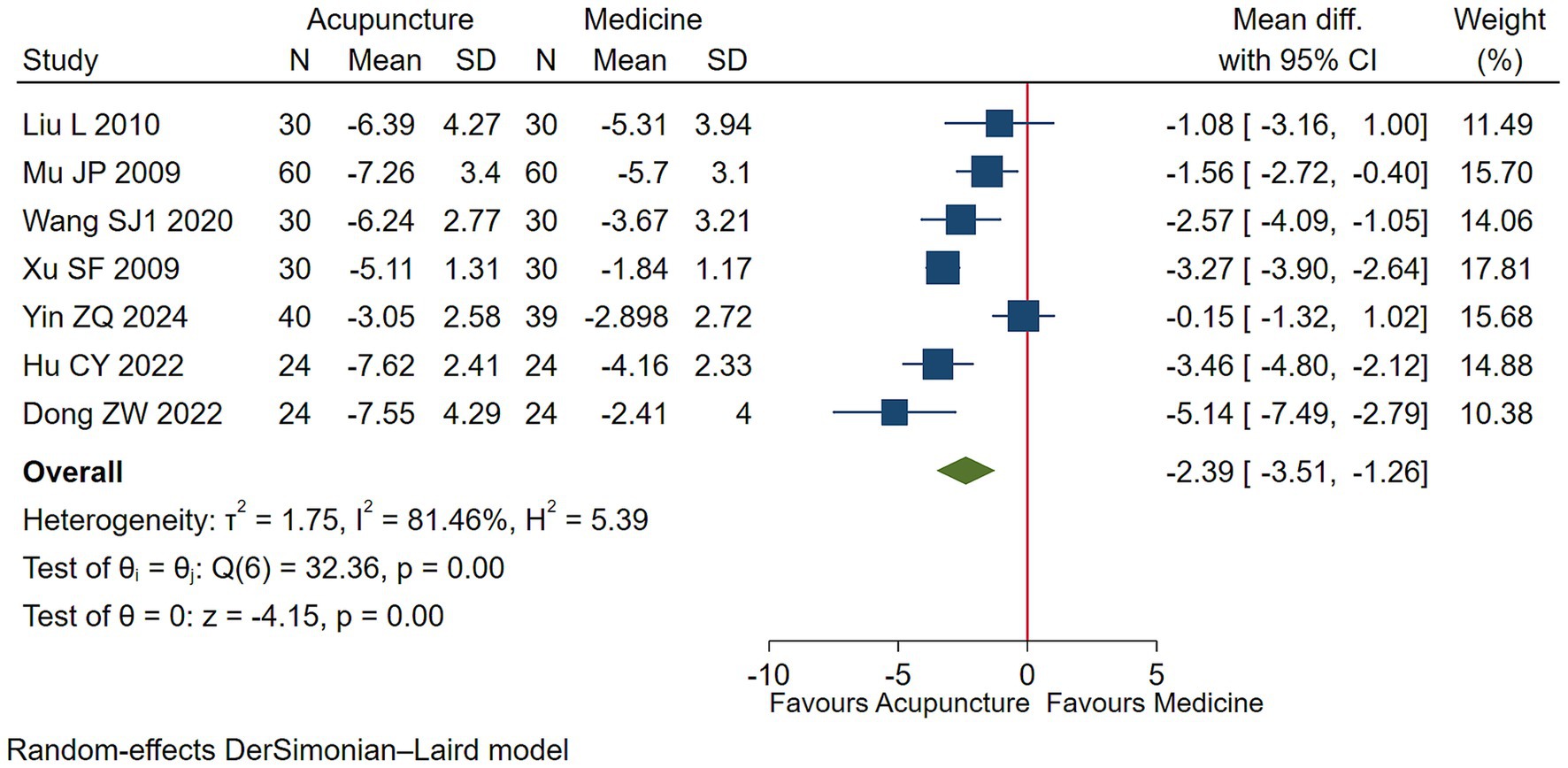

Low-quality evidence (7 studies, 475 participants) suggested that acupuncture may slightly improve vocal tics symptoms in children with TS compared to conventional medication [WMD −2.39, 95% CI (−3.51, −1.26), RD 0.21 (0.10, 0.35) (Figure 3, Table 2)] (25, 26, 30, 31, 33, 35, 36).

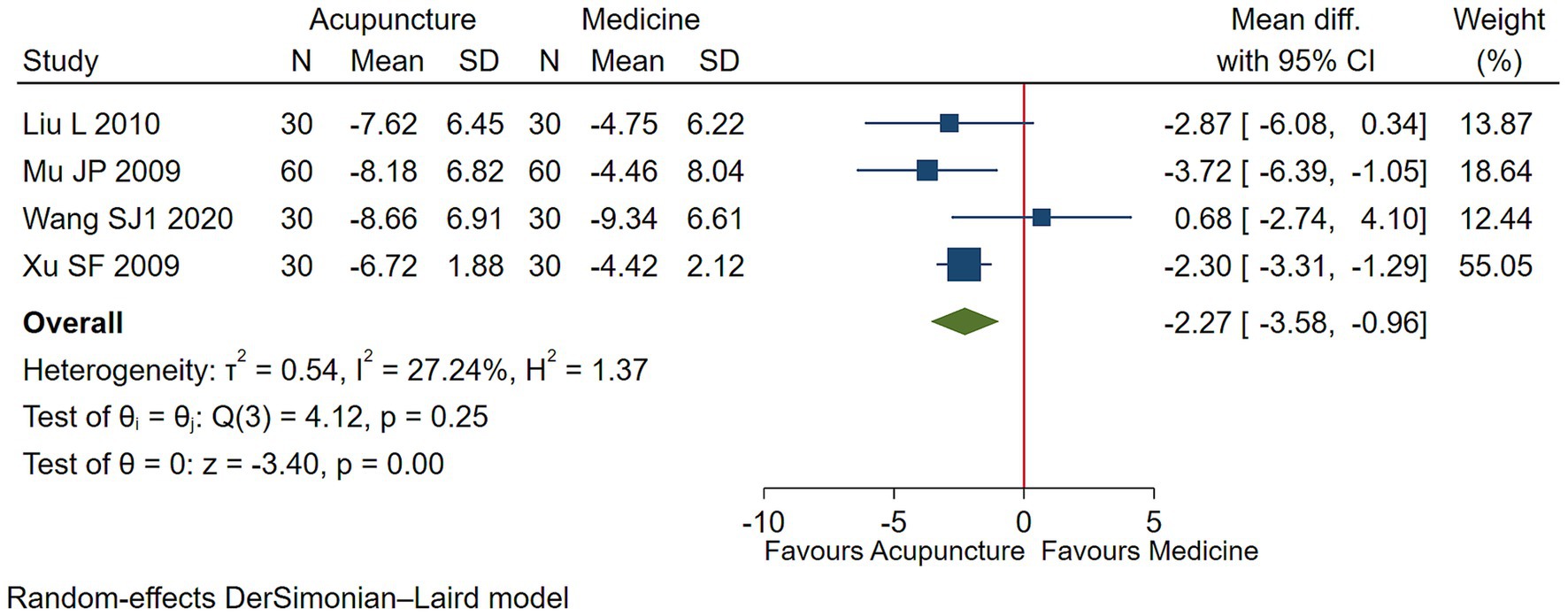

3.4.3 Functional impairment

Low-quality evidence (4 studies, 300 participants) suggested that acupuncture may has a negligible effect on functional impairment in children with TS [WMD −2.27, 95% CI (−3.58, −0.96), RD 0.05 (0.02, 0.09) (Figure 4; Table 2)] (25, 26, 30, 31).

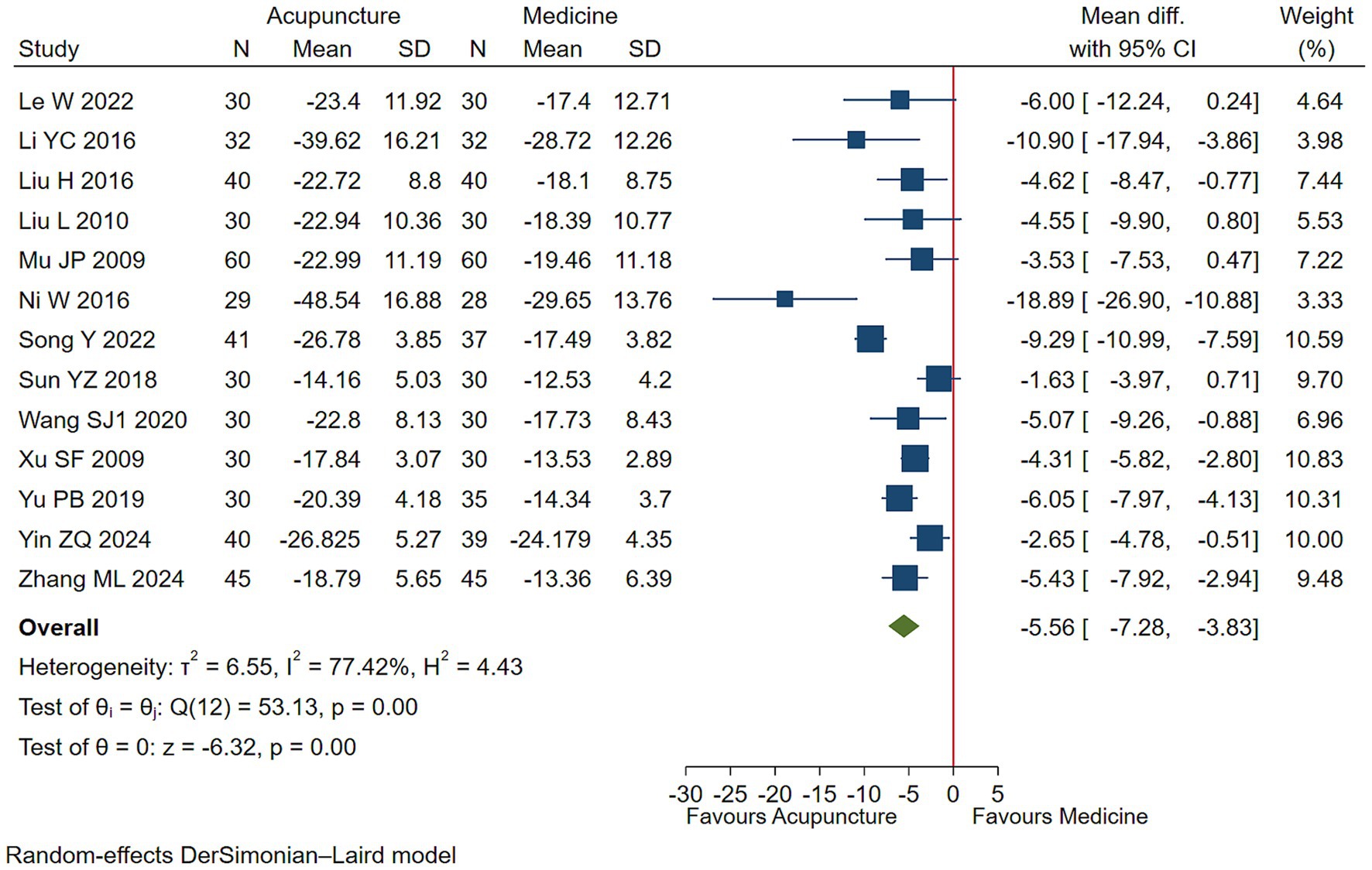

3.4.4 Overall symptom severity

Low-quality evidence (13 studies, 995 participants) suggested that acupuncture may slightly control overall symptom severity in children with TS [WMD −5.56, 95% CI (−7.28, −3.83), RD 0.14 (0.09, 0.20) (Figure 5; Table 2)] (22–31, 33, 34, 52).

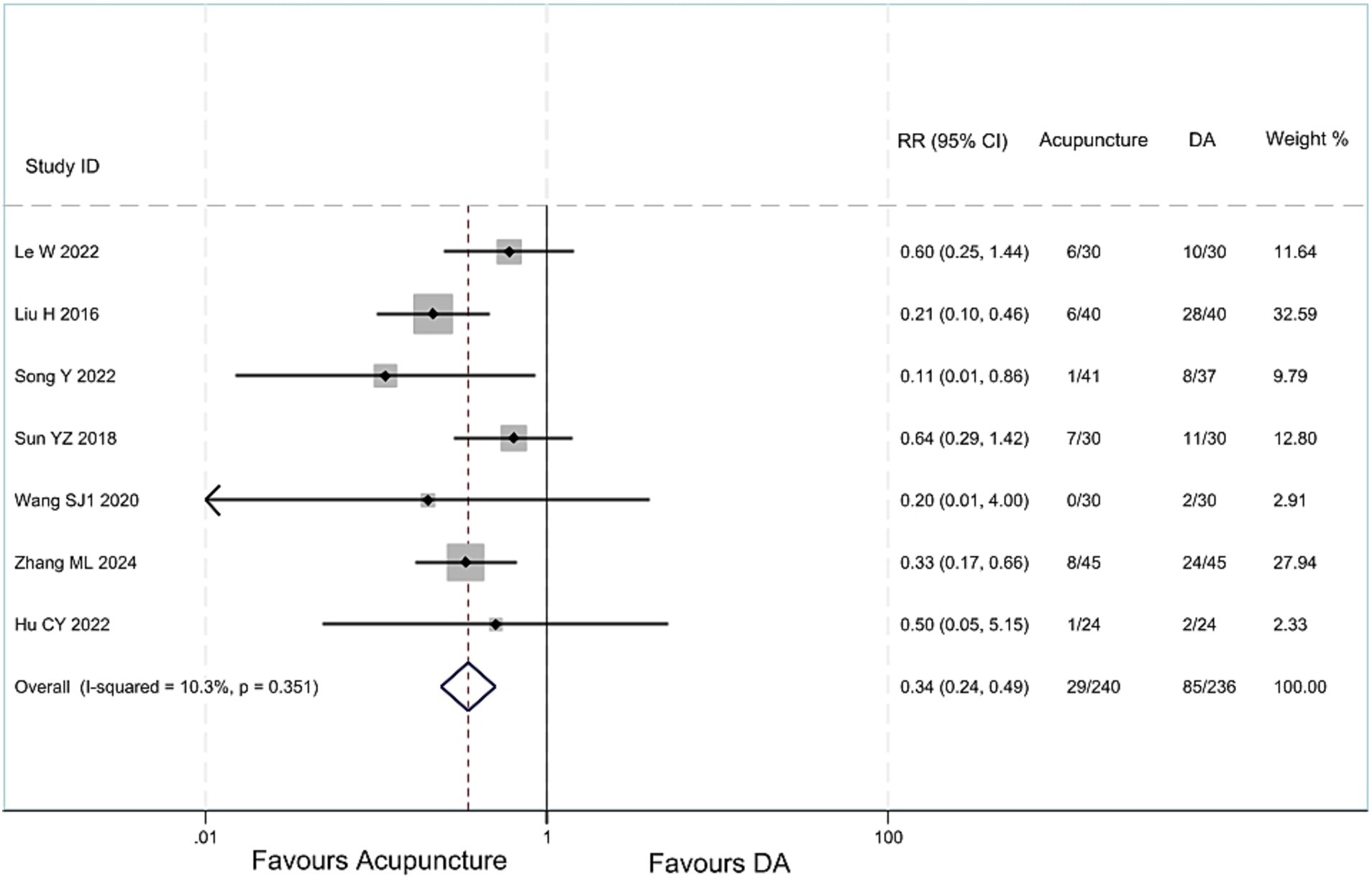

3.4.5 Adverse reactions

Low-quality evidence (7 studies, 476 participants) suggested that acupuncture treatment for children with TS has less adverse reactions than DA, [RR 0.34, 95%CI (0.24, 0.49) (Figure 6; Table 2)] (22, 24, 28–30, 34, 35). One article (33) compared the acupuncture group with the drug group, and found no difference in the incidence of adverse reactions between the two groups.

3.5 Acupuncture vs. blank control on basis of usual care

3.5.1 Motor tic symptoms

Low-quality evidence (10 studies, 722 participants) suggested that acupuncture may lessen more motor tics symptoms in children with TS than blank treatment on basis of usual care [WMD −2.51, 95% CI (−3.54, −1.49), RD 0.31 (0.19, 0.41) (Figure 7; Table 3)] (38, 41–43, 45–47, 49–51).

![This forest plot compares the efficacy of acupuncture therapy with a blank control group in reducing motorized seizures (TS) symptoms in children, presenting mean differences and 95% confidence intervals. All difference values fall to the left of the zero line. The overall effect size is-2.51, with a confidence interval of [-3.54, -1.49]. The figure displays heterogeneity statistics and weight percentages, indicating statistically significant results overall. This suggests acupuncture therapy may demonstrate greater efficacy compared to no treatment.](https://www.frontiersin.org/files/Articles/1677592/fpubh-13-1677592-HTML/image_m/fpubh-13-1677592-g007.jpg)

Figure 7. Acupuncture vs. blank control on basis of usual care evaluation of efficacy of motor tics.

Table 3. GRADE evidence quality rating of the clinical efficacy of acupuncture versus blank therapy for children with TS.

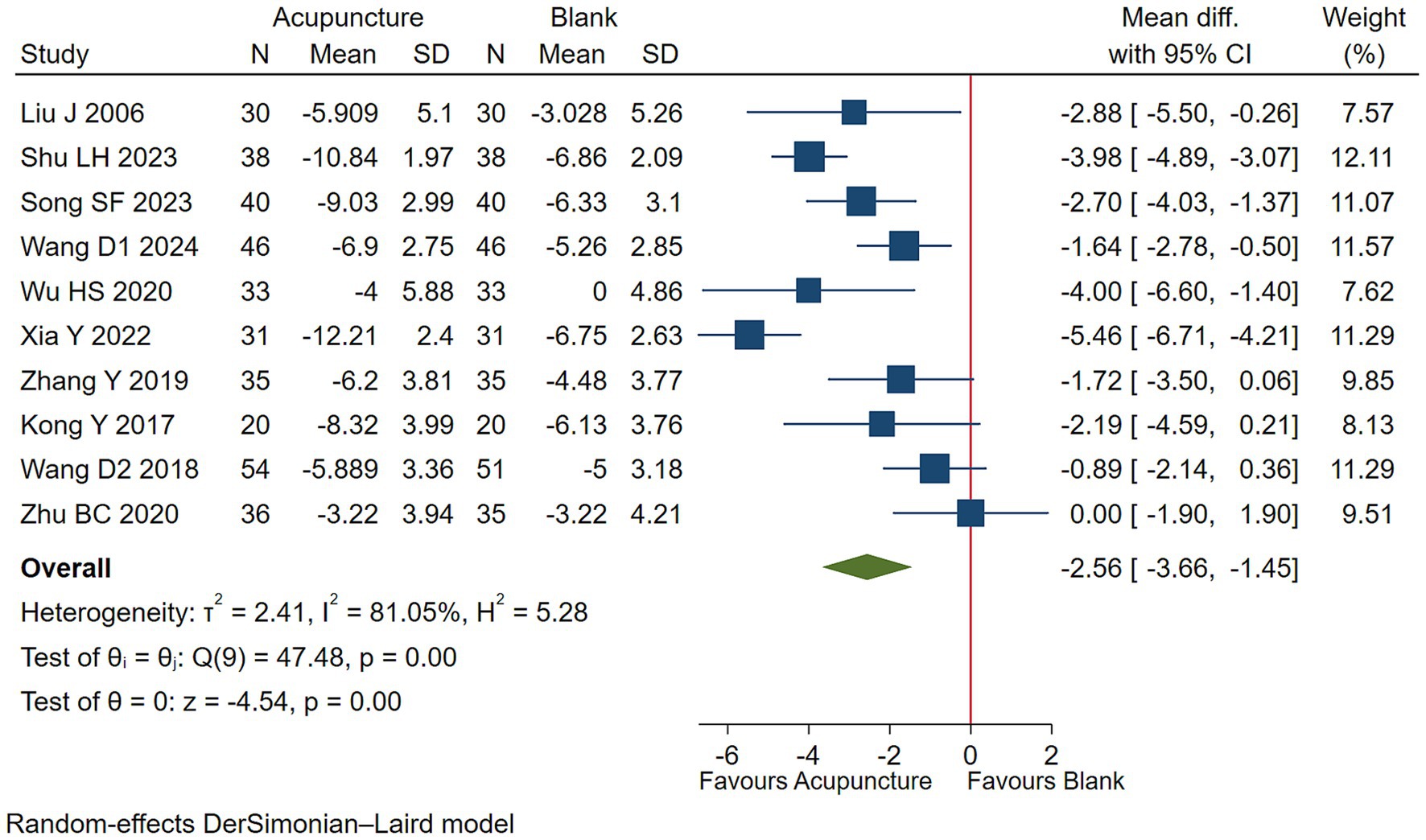

3.5.2 Vocal tic symptoms

Low-quality evidence (10 studies, 722 participants) suggested that acupuncture may improve vocal tics symptoms in children with TS compared to blank treatment on basis of usual care [WMD −2.56, 95% CI (−3.66, −1.45), RD 0.28 (0.15, 0.40) (Figure 8; Table 3)] (38, 41–43, 45–47, 49–51).

Figure 8. Acupuncture vs. blank control on basis of usual care evaluation of efficacy of vocal tics.

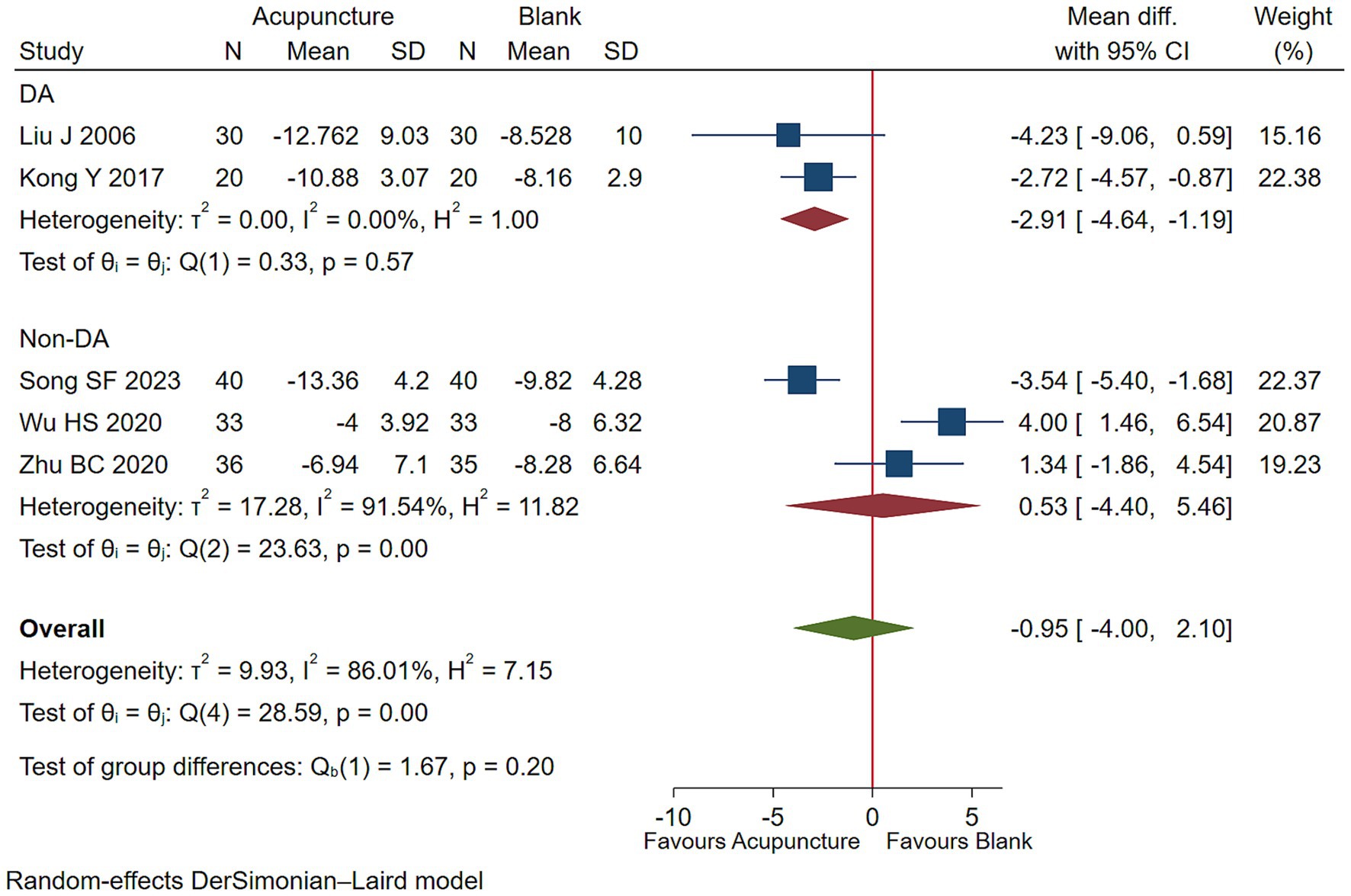

3.5.3 Functional impairment

Low-quality evidence (2 studies, 100 participants) suggested that acupuncture with DA may lessen functioning impairment than DA [WMD −2.91, 95% CI (−4.64, −1.19), RD 0.13 (0.05, 0.23) (Figure 9; Table 3)] (38, 42, 45, 49, 51).

Figure 9. Acupuncture vs. blank control on basis of usual care evaluation of efficacy of functional improvement.

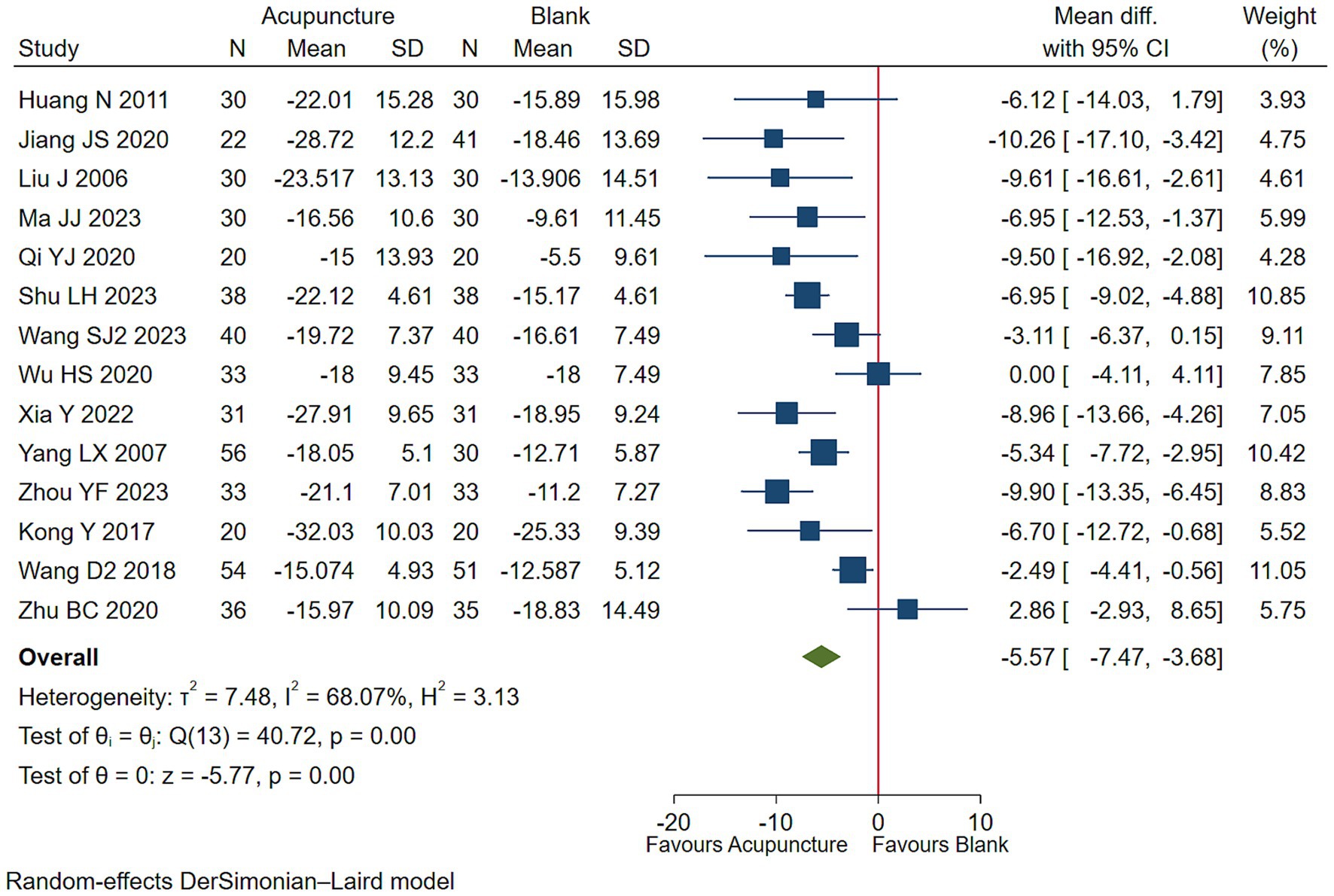

3.5.4 Overall symptom severity

Low-quality evidence (14 studies, 935 participants) suggested that acupuncture may be superior in improving overall symptoms severity in children with TS than blank treatment [WMD −5.57, 95% CI (−7.47, −3.68), RD 0.11 (0.06, 0.17) (Figure 10; Table 3)] (32, 37–41, 44–46, 48–51, 53).

Figure 10. Acupuncture vs. blank control on basis of usual care evaluation of efficacy of overall symptom efficacy evaluation.

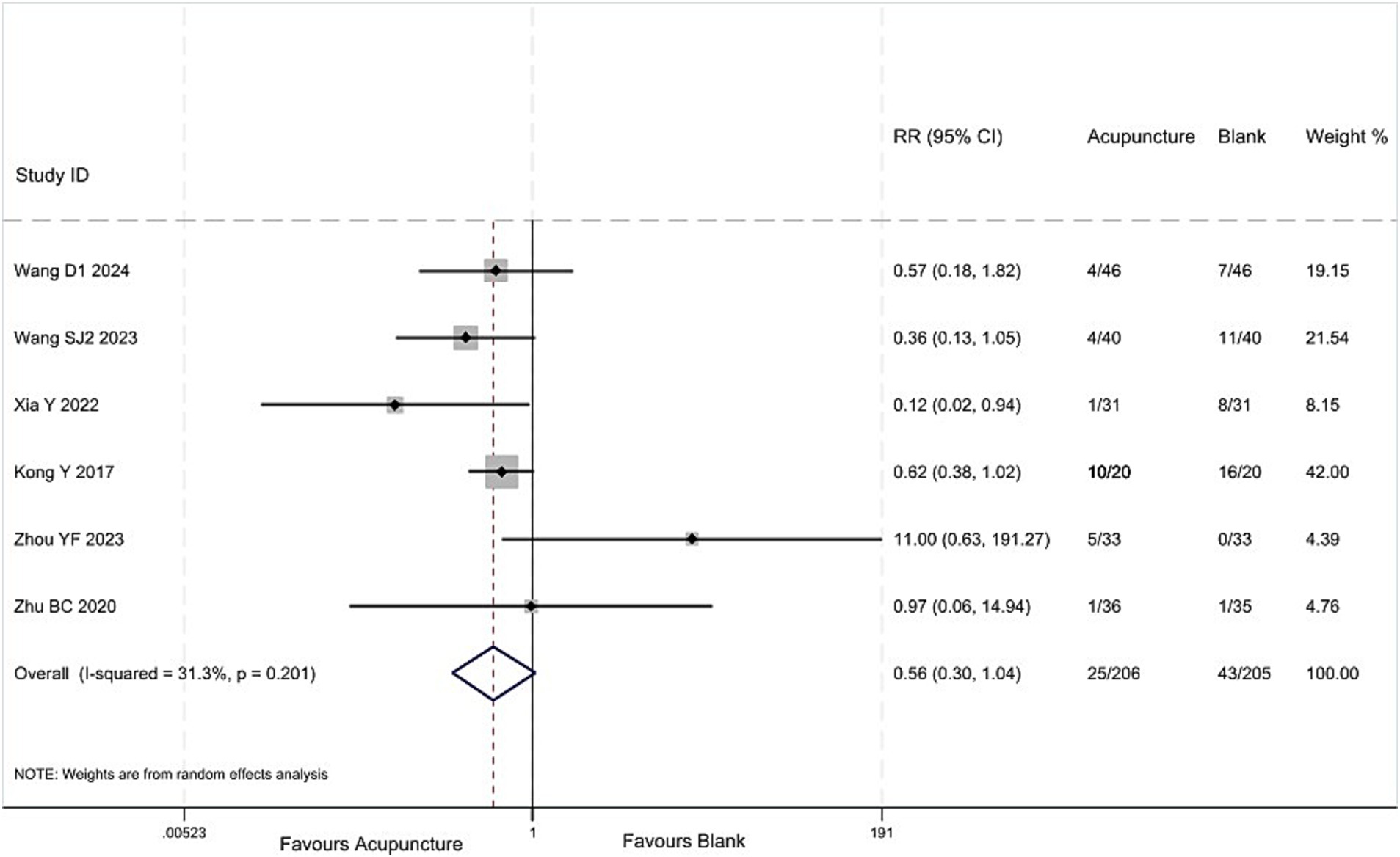

3.5.5 Adverse reactions

Low-quality evidence (6 studies, 411 participants) suggested that the incidence of adverse reactions in children with TS treated with acupuncture combined with other therapies is not significantly different from that in children treated with other therapies alone, [RR 0.56, 95%CI (0.30, 1.04), (Figure 11; Table 3)] (43, 44, 46, 48, 49, 51).

Figure 11. Acupuncture vs. blank control on basis of usual care analysis of the incidence of adverse reactions.

4 Discussion

4.1 Overall findings

Compared with pharmacotherapy, acupuncture may alleviate more motor tics symptoms with less adverse effects, but it may bring about slight improvement in vocal tics, functional impairments, and overall symptom severity in Chinese children with TS. Compared with blank treatment, acupuncture may alleviate more motor tics, vocal tics symptoms, functional impairments, and overall symptom severity in Chinese children with TS.

4.2 Relation of other studies

We identified eleven systematic reviews on acupuncture treatment for childhood tic disorders (11–21). After screening their included studies, we excluded those that enrolled patients with chronic or transient tic disorders, or that used ineligible comparators or outcomes (Supplementary Table 2).

The latest systematic review (21) included 26 studies, with a search cut-off date of October 2023. The results indicated that acupuncture is more effective than most existing treatments in alleviating motor and vocal tics in children with TS, while also reducing the incidence of adverse reactions. However, some outcome measures in the included studies only reported treatment efficacy rates, failing to clearly assess improvements in tic symptom-related scores. Additionally, the study did not include outcomes related to functional impairments in children with TS, focusing solely on motor and vocal tics. Finally, the study did not assess the certainty of the evidence, lacking a certain degree of professionalism.

This study included 18 RCTs not included in the latest review and excluded 12 studies included in the review, with specific reasons as follows: (1) Six studies had questionable inclusion criteria for children with TS, including patients with chronic tic disorder and transient tic disorder (54–59), (2) Two studies had acupuncture intervention durations of less than 28 days (60, 61), (3) Four studies did not report reasonable tic symptom scores (62–65). Our findings lead to a more cautious conclusion than the latest review and emphasize that the role of acupuncture in the treatment of TS in children requires further clinical research to confirm. (Supplementary Table 2).

4.3 Strengths and limitations

The strengths of this study include a comprehensive search for eligible RCTs and a focus on patient-reported outcome measures, with analysis conducted across three domains: motor tics, vocal tics, and functional impairment. We used the GRADE method to assess the certainty of the evidence and referenced the latest research results from the BMJ (66) and Cochrane Collaboration (10) for methodological exploration: first, we calculated the scores where the reduction rate in each YGTSS subscale reached at least 30%, defining this as the MCID. We then calculated the probability of achieving this value in the acupuncture group and the control group, respectively, and used the RD to display the between-group differences, thereby making the findings more accessible and clinically interpretable.

This study has limitations. Only three studies (22, 35, 36) adequately described random-sequence generation, allocation concealment, participant blinding, and implementation details. Additionally, due to the special nature of acupuncture procedures, it was not possible to blind patients or operators, resulting in a high risk of bias. Our review was based on the Chinese population, which limits its generalizability. Evidence from other populations is therefore needed for further analysis.

4.4 Implications

Chinese children with TS who receive acupuncture may experience greater relief of motor tics and fewer adverse effects compared with those on pharmacotherapy. Relative to no-treatment controls, these children also demonstrate larger reductions in vocal tics, functional impairment, and overall symptom severity. Low-certainty evidence underpins these conclusions on basis of Chinese population. Future trials should adopt rigorous methodological safeguards to minimize bias, and additional well-designed RCTs are required to clarify the efficacy of acupuncture for pediatric tic disorders.

5 Conclusion

Compared to pharmacotherapy, acupuncture may relieve more motor tics symptoms with less adverse effects, but it may slightly improve vocal tics, functional impairments, and overall symptom severity in Chinese children with TS. Compared to blank treatment, acupuncture may alleviate more motor tics, vocal tics symptoms, functional impairments, and overall symptom severity in Chinese children with TS. All results are supported by low-quality evidence.

Data availability statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/Supplementary material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Author contributions

Q-QZ: Formal analysis, Software, Resources, Investigation, Writing – review & editing, Conceptualization, Project administration, Methodology, Funding acquisition, Data curation, Writing – original draft. Z-CL: Writing – review & editing, Writing – original draft, Conceptualization, Methodology, Project administration, Resources, Formal analysis, Software, Funding acquisition, Data curation. Z-YH: Writing – original draft, Conceptualization, Software, Investigation, Resources, Methodology, Formal analysis, Project administration, Data curation. JT: Writing – original draft, Data curation, Resources, Conceptualization, Formal analysis, Project administration, Investigation, Methodology. PT: Validation, Visualization, Project administration, Writing – original draft, Software, Investigation. Q-RW: Investigation, Software, Visualization, Writing – original draft, Project administration, Validation. Z-QD: Methodology, Writing – original draft, Formal analysis. W-BM: Methodology, Writing – original draft. LL: Methodology, Writing – review & editing, Formal analysis, Project administration, Data curation, Conceptualization, Investigation, Software, Writing – original draft, Resources, Funding acquisition.

Funding

The author(s) declare that financial support was received for the research and/or publication of this article. This study was funded by the Chengdu University of Traditional Chinese Medicine University-Institute Joint Innovation Fund (Grant No. LH202402049) and Sichuan provincial project (Grant No. 2022YFS0401).

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The authors declare that no Gen AI was used in the creation of this manuscript.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Supplementary material

The Supplementary material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fpubh.2025.1677592/full#supplementary-material

References

1. Hirschtritt, ME, Lee, PC, Pauls, DL, Dion, Y, Grados, MA, Illmann, C, et al. Lifetime prevalence, age of risk, and genetic relationships of comorbid psychiatric disorders in Tourette syndrome. JAMA Psychiatry. (2015) 72:325–33. doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2014.2650

2. Roth, J . The colorful spectrum of Tourette syndrome and its medical, surgical and behavioral therapies. Parkinsonism Relat Disord. (2018) 46:S75–9. doi: 10.1016/j.parkreldis.2017.08.004

3. Lin, LP, Gao, X, Li, YP, Teng, SY, W, SM, and L, XF. Interpretation of the European clinical practice guidelines for the pharmacological treatment of Tourette syndrome, version 2.0. J Psychiatry. (2023) 36:87–91. Available online at: https://kns.cnki.net/kcms2/article/abstract?v=i9XsIId0T11tCFxyjeU4RLjyzip6VgTQe-QLIgxPMEiFcF8zpz1Bk3NRctst-EenZS1agnJP-fv8jP94bRgFLI_6qbEDkf-6Jv1heBWsVU5AZhHv0ycORBI9ZoJetpaFe7tLjcta5BSNhcXY54ms3Vy19snCKQNNRDdWmNUESgNNpozHrmDPEg==&uniplatform=NZKPT&language=CHS

4. Zhang, MJ, and L, HY. Clinical and mechanisms of acupuncture and moxibustion in the treatment of childhood Tourette′s disease. Asia-Pacific Traditional Med. (2020) 16:208–10. doi: 10.11954/ytctyy.202001065

5. Yao, J, Bao, QN, Wu, KX, Zhong, WQ, Zhang, YX, Chen, ZW, et al. The overview and future trend of high-quality clinical randomized controlled trial of acupuncture for neurological disorders. Modern. Traditional Chinese Med. Materia Medica. (2024) 27:973–81. doi: 10.11842/wst.20240409003

6. Moher, D, Liberati, A, Tetzlaff, J, and Altman, DG. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. J Clin Epidemiol. (2009) 62:1006–12. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2009.06.005

7. Jones, KS, Saylam, E, and Ramphul, K. Tourette syndrome and other tic disorders. StatPearls. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing Copyright © 2025, StatPearls Publishing LLC (2025).

8. Higgins, JP, Altman, DG, Gøtzsche, PC, Jüni, P, Moher, D, Oxman, AD, et al. The Cochrane collaboration's tool for assessing risk of bias in randomised trials. BMJ. (2011) 343:d5928. doi: 10.1136/bmj.d5928

9. Akl, EA, Sun, X, Busse, JW, Johnston, BC, Briel, M, Mulla, S, et al. Specific instructions for estimating unclearly reported blinding status in randomized trials were reliable and valid. J Clin Epidemiol. (2012) 65:262–7. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2011.04.015

10. Santesso, N, Glenton, C, Dahm, P, Garner, P, Akl, EA, Alper, B, et al. GRADE guidelines 26: informative statements to communicate the findings of systematic reviews of interventions. J Clin Epidemiol. (2020) 119:126–35. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2019.10.014

11. Lin, Y, Yu, MF, Huang, SJ, Zhang, CH, and Lr, D. Specific instructions for estimating unclearly reported blinding status in randomized trials were reliable and valid. J Guangzhou Univ Tradit Chin Med. (2022) 39:2989–96. doi: 10.13359/j.cnki.gzxbtcm.2022.12.042

12. Zhu, BC, Shan, YH, Cao, Y, and Z, HM. Efficacy of acupuncture and moxibustion for treating Tourette syndrome: a meta analysis. J. Modern Med. Health. (2020) 36:2314–8. doi: 10.3969/j.issn.1009-5519.2020.15.005

13. Zhou, WX, Gong, BZ, and N, X. A meta-analysis on scalp acupuncture treatment of Tourette syndrome. J Li-shizhen Tradit Chin Med. (2021) 32:230–4. doi: 10.3969/j.issn.1008-0805.2021.01.72

14. Ni, XQ, Wu, ZZ, Qin, J, Li, LM, and Yh, L. A meta-analysis on randomized controlled trials of acupuncture in treatment of children with tic disorders. Chin Arch Tradit Chin Med. (2017) 35:2608–14. doi: 10.13193/j.issn.1673-7717.2017.10.037

15. Xiao, L, Chen, YW, Du, YH, Gao, X, Lin, XM, and S, P. Evaluation of clinical randomized control trials of acupuncture for treatment of multiple tics-coprolalia syndrome. J Li-shizhen Tradit Chin Med. (2010) 21:1199–202. doi: 10.3969/j.issn.1008-0805.2010.05.084

16. Zhao, RZ, Xin, Y, Wang, WY, Wang, WQ, and S, K. Meta-analysis of the clinical efficacy of acupuncture treatment for tic disorders. Shanghai J. Acupuncture Moxibustion. (2020) 39:244–52. doi: 10.13460/j.issn.1005-0957.2020.02.0244

17. Li, JR, Li, X, Sun, MY, and Bai, YJ. Network meta-analysis of acupuncture and moxibustion for tic disorder. World J. Integrated Traditional Western Med. (2022) 17:1079–84. doi: 10.13935/j.cnki.sjzx.220603

18. Zhao, D . Evaluation of the efficacy of acupuncture in improving clinical symptoms of Tourette syndrome [dissertation/master's thesis]. Chengdu: Chengdu University of Traditional Chinese Medicine (2015).

19. Liu, L, Ni, XX, Tian, T, Li, X, Wang, YN, and Z, L. Current status and analysis of randomized controlled clinical trials of acupuncture in the treatment of TiC in children. Modern. Traditional Chinese Med. Materia Medica. (2020) 22:2751–7. doi: 10.11842/wst.20190710008

20. Liu, X, and Chen, CMJF. M. Mesh meta-analysis of acupuncture and moxibustion related therapies for tic disorder. China Med Pharm. (2023) 13:53–8. doi: 10.3969/j.issn.2095-0616.2023.02.014

21. Lai, S, Wan, H, Deng, F, Li, Y, An, Y, Peng, J, et al. Efficacy and safety of acupuncture for Tourette syndrome in children: a Meta-analysis and systematic review. Clin Pediatr (Phila). (2025) 64:719–35. doi: 10.1177/00099228241283279

22. Le, W, Su, W, J, W, and Y, LL. Randomized controlled clinical study of Zhang's scalp acupuncture in the treatment of children with multiple tics. Modern. Traditional Chinese Med. Materia Medica. (2022) 24:939–45. doi: 10.11842/wst.20210719007

23. Li, YC, Bao, C, Chen, D, and Q, B. Clinical observation of 32 cases of childhood tic disorder treated primarily with electroacupuncture at the four gates acupoints. Jiangsu J Tradit Chin Med. (2016) 48:57–8. Available online at: https://kns.cnki.net/kcms2/article/abstract?v=i9XsIId0T13tnd2pqxjTTs20gUEF7ZKVfkdA3l4H9DHhiaDW0_fIobQQ5JXjAyLDaWL13wgDnpEhWggGUa9-XT9PuM4RIX-euzJqhBJQfxOy88LQQnsj-bJPghsgyLqIc2DAo3AKGWVQXKTyHXExIUbT4ctygHFtPakT7v34Mhi4iEycy1AxVQ==&uniplatform=NZKPT&language=CHS

24. Liu, H, Zou, W, Yu, XP, Teng, W, Yu, WW, Ma, HH, et al. Observations on the therapeutic effect of acupuncture on Tourette's syndrome. Shanghai J Acupunct Moxibustion. (2016) 35:977–9. doi: 10.13460/j.issn.1005-0957.2016.08.0977

25. Liu, L, Li, XL, Wang, F, Xu, YF, and X, G. Clinical effects and influences of neurotransmitters on the treatment of GTS by using electroacupuncture on the head. Acta Chin Med Pharmacol. (2010) 38:128–31. doi: 10.19664/j.cnki.1002-2392.2010.05.052

26. Mu, JP, Cheng, JM, Ao, JB, Zhou, LZ, Wang, J, and F, W. Clinical study of electroacupuncture combined with psychobehavioral therapy in the treatment of Tourette syndrome in 60 cases. Jiangsu J Tradit Chin Med. (2009) 41:49–51. doi: 10.3969/j.issn.1672-397X.2009.02.030

27. Ni, W. (2016) Evaluation of curative effect of regulating the liver and calming the wind acupuncture therapy on children's tourette's syndrome caused by yin deficiency and wind type [Dissertation/master’s thesis]. Nanjing: Nanjing: Nanjing University of Traditional Chinese Medicine.

28. Song, Y . Clinical observation on 41 cases of tic disorders in children with kidney-yin consumption and liver-wind stirring type treated by electroacupuncture therapy. J. Pediatrics of Traditional Chinese Med. (2022) 18:87–90. doi: 10.16840/j.issn1673-4297.2022.04.22

29. Sun, YZ, and L, C. YU'S cluster needling at scalp acupoints for tourette's syndrome. J. Changchun Univ. Chinese Med. (2018) 34:737–9. doi: 10.13463/j.cnki.cczyy.2018.04.039

30. Wang, SJ . Clinical observation on the treatment of pediatric multiple tics with scalp point penetration acupuncture [dissertation/master's thesis]. Heilongjiang: Heilongjiang Provincial Academy of Traditional Chinese Medicine (2020).

31. Xu, SF, and Bc, Z. Observation of the efficacy of acupuncture treatment with retained needles in the head acupoints for 30 cases of Tourette syndrome. Guiding J. Traditional Chinese Med. Pharmacy. (2009) 15:58–9. doi: 10.3969/j.issn.1672-951X.2009.06.029

32. Huang, N . The clinical research on treatment of tourette syndrome in children by acupuncture added chinese herbs [dissertation/master's thesis]. Guangzhou: Guangzhou University of Traditional Chinese Medicine (2011).

33. Yin, ZQ . Clinical observation and curative effect analysis of acupuncture treatment for hyperactivity of liver with wind in children tic disorder [dissertation/master's thesis]. Hebei: Hebei University (2024).

34. Zhang, ML, Liu, Y, and Z, Q. A comparative study of acupuncture therapy and tiapride in the treatment of childhood tourette syndrome of wind-phlegm blocking collaterals type. Clin J Chin Med. (2024) 16:141–4. doi: 10.3969/j.issn.1674-7860.2024.33.030

35. Hu, CY, and H, L. Clinical observation on the treatment of phlegm and fire internal disturbance type of Pediatric Tourette syndrome by opening Siguan acupoint. Prac. Clinical J. Integrated Traditional Chinese Western Med. (2022) 22:17–20. doi: 10.13638/j.issn.1671-4040.2022.07.004

36. Dong, ZW, and Z, YP. “Clinical observation of the treatment of childhood tic disorder with obscene language syndrome caused by internal disturbance of phlegm and fire using the ‘open four gates’ method.” in 2022 annual meeting of the Chinese acupuncture society. Jinan, Shandong Province, China (2022). doi: 10.26914/c.cnkihy.2022.018242

37. Jiang, JS . Logistic regression analysis of factors associated with childhood tic disorder and evaluation of clinical efficacy of combined acupuncture and medication treatment [dissertation/master's thesis]. Liaoning: Liaoning University of Traditional Chinese Medicine (2020).

38. Liu, J. (2006) Clinical study on the treatment of Tourette syndrome using electroacupuncture at acupoints on the head [Dissertation/master’s thesis]. Heilongjiang: Heilongjiang provincial academy of traditional Chinese medicine

39. Ma, JJ, Fan, GJ, and L, XH. Clinical observation on 30 cases of tourette syndrome with qi stagnation transforming into fire in children treated by combination of acupuncture and medicine. J. Gansu Univ. Chinese Med. (2023) 40:95–8. doi: 10.16841/j.issn1003-8450.2023.06.18

40. Qi, YJ . Clinical study on the effect of "Tiaogan Xifeng" acupuncture and psychological improvement of children with tourette disorder [dissertation/master's thesis]. Nanjing: Nanjing University of Traditional Chinese Medicine (2020).

41. Shu, LH . Clinical observation on 38 cases of Tourette syndrome treated with integrated traditional Chinese and Western medicine. Chinese J. Ethnomedicine Ethnopharmacy. (2023) 32:97–100. Available online at: https://kns.cnki.net/kcms2/article/abstract?v=i9XsIId0T124sylMCShsd83Q8i_z-30dk8PjqfTTN6Oxx82CRZp7gxXeObmmlW7XYDqok3v0uTfp_qxRup-wJH8i9-TTK2pbzhpY5GZNtu4Jg3kFh6j5vvMRjUikbE77bWGjYXkwA22bM1PMfCYjtNnCmjreLAv1Yacu6iZupLTVtKS67jWgXw==&uniplatform=NZKPT&language=CHS

42. Song, SF, and Wang, XY. Effects of scalp acupuncture combined with ear pressure beans in treatment of children with tic disorders. Med J Chin Peoples Health. (2023) 35:116–9. doi: 10.3969/j.issn.1672-0369.2023.13.035

43. Wang, D, and Peng, W. Effect of acupuncture combined with haloperidol on children with multiple convulsions. J Pract Tradit Chin Intern Med. (2024) 38:98–100.

44. Wang, SJ, and Ye, GXKT. W. Observation on the therapeutic effect of "Xiaoxingnao" acupuncture method on children with tic disorders. Forum Traditional Chinese Med. (2023) 38:37–9. doi: 10.13913/j.cnki.41-1110/r.2023.03.021

45. Wu, HS . Clinical study on the combined use of acupuncture and Chinese herbal medicine based on the ‘liver-spleen theory’ for the treatment of childhood tic disorder [dissertation/master's thesis]. Shanghai: Shanghai University of Traditional Chinese Medicine (2020).

46. Xia, Y, and W, HN. Clinical observation on 31 cases of children with multiple tic disorders treated by acupuncture clinical observation on 31 cases of children with multiple tic disorders treated by acupuncture. J. Pediatrics Traditional Chinese Med. (2022) 18:89–93. doi: 10.16840/j.issn1673-4297.2022.05.21

47. Zhang, Y . Clinical observation on 35 cases of children with Gilles de la Tourette syndrome treated by acupuncture clinical observation on 35 cases of children with Gilles de la Tourette syndrome treated by acupuncture. J. Pediatrics Traditional Chinese Med. (2019) 15:74–7. doi: 10.16840/j.issn1673-4297.2019.02.22

48. Zhou, YF, You, HZ, Yu, PB, Wang, CJ, Chen, Y, Xie, J, et al. Tongdu Tiaoshen acupuncture combined with clonidine transdermal patch in the treatment of children with tic disorders:a randomized controlled trial. Chin J Integr Tradit West Med. (2023) 43:39–44. doi: 10.7661/j.cjim.20220705.055

49. Kong, Y, Xu, HP, Gao, W, and Xy, L. Clinics observation of scalp-acupuncture combined with medication in the treatment of Tourette's syndrome. J Clinical Acupuncture Moxibustion. (2017) 33:20–4. doi: 10.3969/j.issn.1005-0779.2017.11.006

50. Wang, D . Aclinical control study on scalp-acupuncture combined with tiapride for the treatment of tourette's syndrome [dissertation/master's thesis]. Hubei: Hubei University of Chinese Medicine (2018).

51. Zhu, BC, Li, YF, Shan, YH, Feng, YL, Cao, Y, Zheng, HM, et al. Study on the clinical effect of scalp acupuncture combined with traditional Chinese medicine in the treatment of tics. J Mod Med Health. (2020) 36:3906–10. doi: 10.3969/j.issn.1009-5519.2020.24.005

52. Yu, P, Sun, K, and Zhou, S. Therapeutic observation of swift needling at Fengchi (GB20) for Tourette syndrome. Shanghai J Acupunct Moxibustion. (2019) 38:497–500. doi: 10.13460/j.issn.1005-0957.2019.05.0497

53. Yang, LX, Wu, J, and Z, XG. Clinical observation of comprehensive rehabilitation therapy mainly using acupuncture for treating Tourette syndrome. Chin J Rehabil Med. (2007) 5:457–9. doi: 10.3969/j.issn.1001-1242.2007.05.023

54. Huang, Y . Clinical observation of the therapeutic effect of acupuncture treatment using the method of regulating the spirit and calming the liver on children with tic disorder. Essential Health Reading. (2021) 9:38. Available at: https://d.wanfangdata.com.cn/periodical/ChVQZXJpb2RpY2FsQ0hJMjAyNTA2MjISEGprYmQwMDEyMDIxMDkwNDAaCHJvMW4xNGFp

55. Gik, HY . Clinical observation of the treatment for the children with transient tic disorder based on "TiaoShenXiFeng acupuncture" [dissertation/master's thesis]. Nanjing: Nanjing University of Traditional Chinese Medicine (2019).

56. Guo, MR . An observational study on the clinical effects of acupuncture combined with rehabilitation training for children with tic disorder characterised by spleen deficiency and liver hyperactivity [dissertation/master's thesis]. Hebei: Hebei University of Chinese Medicine (2021).

57. Luo, W . Clinical observation of Chinese herbal medicine combined with needling in the treatment of children with tic disorder syndrome with pattern of spleen deficiency and hyperactivity of liver [dissertation/master's thesis]. Jiangxi: jiangxi University of Chinese Medicine (2021).

58. Chen, YL . Clinical observation of acupuncture on tic disorder. Hubei J Tradit Chin Med. (2016) 38:6–8. Available at: https://kns.cnki.net/kcms2/article/abstract?v=i9XsIId0T123dJjmKVFUdB7ZsIfbmBgErFei3Si7FsJRbT0BzVy7GcJosnwFS0vR-w3y31bZrOrsQvXDCx3giWE9vZCQ4uYHke4vGK4gnZbIQYn9qq2mGDhA5wh4AO2938ETWPp8ONakKfRJMhpdeJ9V0deYK2VaLm4EIzYooqln75Ahoc9SSA==&uniplatform=NZKPT&language=CHS

59. Huang, LZ . Clinical observation on regulating the mind and calm the liver acupuncture in the treatment of children with tic disorders [dissertation/master's thesis]. Fujian: Fujian University of Traditional Chinese Medicine (2019).

60. Yang, N . The clinical study of acupuncture shu-points of the five-organs combined with auriculai point therapy for the treatment of Tourette syndrome [dissertation/master's thesis]. Changchun: Changchun University of Traditional Chinese Medicine (2018).

61. Huang, J, and Xm, Y. Effect of Luozang abdominal acupuncture combined with aripiprazole on children with Tourette syndrome and its effects on muscle function and neurotransmitters. Liaoning J Tradit Chin Med. (2023) 50:174–177+225. doi: 10.13192/j.issn.1000-1719.2023.02.046

62. Miao, QX, Wu, G, and Zhou, PS. Clinical observation of Taixi acupuncture in treating pediatric tic disorder. J Pract Tradit Chin Med. (2019) 35:599–600. Available online at: https://kns.cnki.net/kcms2/article/abstract?v=i9XsIId0T129xkUObs10goa5LmNz9ViYu_tXv1YuSocZo8hQn-lOKFtgN0MI-Zd3ZEB7ff1820g_WMuAWe1iiBvHdKRNBIMHS9r5KAwccS_853K7H3X6RNXnoke3w6OOp6A8yP2e8BBhPUYnlh2JQnAAoyObLvC1TV9-vJt3eNndEI1J7DnsEQ==&uniplatform=NZKPT&language=CHS

63. Shi, XH, Ying, HZ, and Y, HF. Clinical study on acupuncture with Qingxin Pinggan method combined with spine pinching therapy for children multiple tics. New Chin Med. (2021) 53:135–8. doi: 10.13457/j.cnki.jncm.2021.16.035

64. Wu, HS, Huang, WT, and S, WD. Curative effect of fast needling in treating pediatric Tourette syndrome. Journal of Clinical Acupuncture and Moxibustion. (2021) 37:49–52. doi: 10.19917/j.cnki.1005-0779.021182

65. Fang, JX . Acupuncture combined with haloperidol treatment for 30 cases of childhood tic disorder. Journal of External Therapy of Traditional Chinese Medicine. (2013) 22:20–1. doi: 10.3969/j.issn.1006-978X.2013.04.013

Keywords: acupuncture, Tourette syndrome, children, systematic review, meta-analysis

Citation: Zhou Q-Q, Li Z-C, Hu Z-Y, Tang J, Tang P, Wu Q-R, Deng Z-Q, Ma W-B and Lan L (2025) The effectiveness of acupuncture in the treatment of Tourette syndrome in Chinese children: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Front. Public Health. 13:1677592. doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2025.1677592

Edited by:

Georg Johannes Seifert, Charité Universitätsmedizin Berlin - Charité Competence Center for Traditional and Integrative Medicine (CCCTIM), GermanyReviewed by:

Valeria Sajin, Asklepios Klinik St. Georg, GermanyPaulo Sargento, Escola Superior de Saúde Ribeiro Sanches, Portugal

Ibrahim Serag, Mansoura University, Egypt

Copyright © 2025 Zhou, Li, Hu, Tang, Tang, Wu, Deng, Ma and Lan. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Lei Lan, bGFubGVpQGNkdXRjbS5lZHUuY29t

Qian-Qian Zhou

Qian-Qian Zhou Zi-Chen Li

Zi-Chen Li Zhuo-Ya Hu1

Zhuo-Ya Hu1 Wen-Bin Ma

Wen-Bin Ma Lei Lan

Lei Lan