- 1Department of Nursing, Fethiye Faculty of Health Sciences, Muğla Sıtkı Koçman University, Muğla, Türkiye

- 2Dokuz Eylul University Hospital, Izmir, Türkiye

- 3Dokuz Eylul University, Faculty of Nursing, Izmir, Türkiye

- 4Dokuz Eylul Universitesi Hemsirelik Fakultesi, Izmir, Türkiye

Background: Assessing the psychological impact of the pandemic on nurses is essential for protecting their well-being and ensuring the resilience of healthcare systems.

Methods: A descriptive, cross-sectional study following the STROBE reporting guidelines. The study included 417 nurses from Dokuz Eylul University Research and Practice Hospital who participated voluntarily. Data were collected between July and October 2021 using the Sociodemographic Data Form, the COVID-19 Phobia Scale (C19P-S), and the Mental Health Continuum Short Form (MHC-SF). Descriptive statistics and multiple linear regression analysis were used (p < 0.05).

Results: The mean C19P-S score was 49.03 ± 17.29. Gender, education, perceived general health status, and intention to quit predicted 17% of COVID-19 phobia variance (R2 = 0.17, p < 0.05). The mean MHC-SF score was 34.31 ± 16.53. Categorically, 46.8% of nurses were languishing in the emotional subdimension, 42.4% were mentally healthy, and 25% were languishing in social and psychological well-being.

Conclusion: Nurses experienced moderate COVID-19 phobia, with female gender, undergraduate education, worse perceived health, and intention to quit emerging as significant predictors, collectively explaining 17% of the variance. Interventions are needed to strengthen nurses’ mental health, particularly emotional well-being. Healthcare policymakers and administrators should implement strategies to support nurses’ psychological well-being and foster a fear-free work environment through empowerment.

Highlights

• Nurses experienced a high level of COVID-19 phobia, with greater psychological and social impacts compared to somatic and economic effects.

• Nearly half of the nurses exhibited emotional languishing, while a quarter experienced psychological and social languishing, reflecting the substantial mental health burden they faced.

• Sex, education, perceived general health status, and intention to quit collectively accounted for 17% of the variance in COVID-19 phobia.

Introduction

The novel virus SARS-CoV-2 first emerged in Wuhan, China, in late 2019. Its rapid global spread led the World Health Organization (WHO) to declare a pandemic on March 11, 2020 (1). Since its emergence, the virus has caused significant morbidity and mortality worldwide. As of January 31, 2024, a total of 774,291,287 cases and 7,019,704 deaths have been reported globally (2), while in Turkey, the Ministry of Health recorded 17,232,066 cases and 102,174 deaths as of March 2023 (3).

While the immediate concern during the outbreak focused on physical health outcomes, mounting evidence suggests that the pandemic also exerted profound psychological and social effects across populations (4–6). Among healthcare workers (HCWs) at the frontline, these effects are particularly pronounced. The combination of rapid viral transmission, high fatality rates, and systemic healthcare pressures has led to a novel psychological response, termed “corona phobia,” which reflects excessive fear and anxiety related to COVID-19 (7–9). This construct aligns with the DSM-IV criteria for specific phobias and has been validated using tools such as the COVID-19 Phobia Scale (9). Prior studies indicate that corona phobia is associated with anxiety, depression, distress, and sleep disturbances among both healthcare professionals and the general population, highlighting its relevance for mental health interventions (10–12).

Healthcare professionals have been disproportionately impacted by the dual physical and psychological stresses associated with the pandemic. WHO estimated that 35 million healthcare workers had been infected globally (1). According to the International Council of Nurses (ICN), more than 20,000 healthcare workers lost their lives during the pandemic, including 1,500 nurses across 44 countries (13). In Turkey, as of April 29, 2020, 7,428 HCWs had contracted the virus, accounting for 6.5% of all reported cases at that time (14).

The psychological burden for HCWs extends beyond the fear of infection and mortality. Nurses, in particular, have reported high levels of anxiety, depression, burnout, and moral distress due to their exposure to critically ill patients, ethical dilemmas in triage decisions, and the risk of transmitting the virus to their families (10, 11, 15). Research indicates that corona phobia significantly influences professional turnover intention (β = 0.316) and organizational turnover intention (β = 0.424) among HCWs, further straining healthcare systems (16). These challenges were further compounded by the pressures of equitably allocating limited resources, balancing personal and professional health needs, and addressing the demands of an overstretched healthcare system (17). Furthermore, factors such as social support, institutional resources, access to personal protective equipment (PPE), resilience, and media exposure may modulate the psychological impact of the pandemic, suggesting that additional unmeasured variables contribute to mental health outcomes (12, 18–20).

While numerous studies have explored the impact of the pandemic on different populations (21–26), research specifically examining corona phobia among nurses and its determinants remains scarce. Understanding these psychological burdens is essential for developing targeted interventions that enhance nurses’ mental well-being and resilience. Addressing these challenges may not only enhance nurses’ well-being but also strengthen healthcare systems’ preparedness and effectiveness in future public health crises. Accordingly, this study aimed to examine Coronavirus Phobia (COVID-19) and mental health conditions among nurses and to identify factors predicting COVID-19 phobia.

Methods

Study design

A descriptive, cross-sectional study following the STROBE reporting guidelines.

Setting and participants

The study included 417 nurses from Dokuz Eylul University Research and Practice Hospital. Using 95% confidence level, alpha equals 0.05, known value (Mean = 40.00), mean of the population (34.51), the standard deviation of the sampled population (16.53) and sample size 417, the power of the study was calculated, and determined to be 100% (27, 28).

Data sources/measurement

The data collection instruments were distributed to all nurses via Google Forms. Preliminary information about the study was provided electronically, and data were collected from nurses who voluntarily agreed to participate with system approval. Online self-report questionnaires were preferred, as they are widely recommended in psychological and mental health research for capturing subjective perceptions and emotional states that cannot be directly observed. Studies conducted with healthcare workers during the COVID-19 pandemic have reported that online self-report methods are both safe and feasible, minimizing face-to-face contact, and facilitating the data collection process (29–31). After the data collection, participants were informed that the study results would be shared with them after publication, and the research team’s contact information was provided for any inquiries. Additionally, the findings, results, and recommendations obtained from the study were shared with the hospital’s nursing services management.

The sociodemographic and job characteristics data form

The form delineates the participants’ sociodemographic and professional characteristics. This scale consists of 17 questions, including information such as age, sex, educational status, marital status, working status in pandemic clinics, working time in pandemic clinics, working time in the institution, working time in the profession, and average number of patients cared for during the pandemic.

COVID-19 phobia scale (C19P-S)

The development of the scale was motivated by the necessity to assess the potential for the emergence of new phobias in response to the pandemic. This scale was developed to measure the potential development of phobia related to the novel coronavirus, and its validity and reliability have been established. The scale utilizes a five-point Likert scale, ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree). The scale is composed of four subdimensions and 20 items. The psychological subdimension is measured by the first five items, the somatic subdimension by the sixth and twelfth items, the social subdimension by the seventh, eleventh, and sixteenth items, and the economic subdimension by the eighth, fourteenth, and sixteenth items. The subdimension scores are derived by summing the scores of the responses to the items that fall within a given subdimension. The total C19P-S score of the scale is determined by aggregating the subdimension scores. The scale score ranges from 20 to 100 points. Higher scores indicate greater levels of coronaphobia in subdimensions and overall. It is noteworthy that the scale does not include reverse-scored items, and the Cronbach’s alpha value is reported as 0.92 (9). In the present study, Cronbach’s alpha was determined to be 0.95, suggesting a high degree of internal consistency in the scale’s measurements.

The mental health continuum short form (RSS-CF)

The scale in question is a self-report scale developed by Keyes et al. (32) that measures emotional, social, and psychological well-being characteristics. It represents the mental health continuum. The self-report component of the scale is derived from the individual’s self-reported experiences and perceptions. The validity and reliability of the scale were established by Demirci and Akin (33). It consists of 14 items and three subdimensions: emotional (items 1, 2, and 3); social well-being (items 4, 5, 6, 7, and 8); and psychological (items 9, 10, 11, 12, 13, and 14). The scale utilizes a 6-point Likert scale, ranging from 0, representing “Never,” to 5, representing “Every day.” The total score that can be obtained from the scale varies between 0 and 70. It is noteworthy that the scale does not include reverse-scored items. The total score pertaining to mental health continuity was derived by summing the 14 items that comprise the scale. Additionally, the subscales can be scored independently. High scores on each subscale are indicative of high well-being in that specific area. Individuals who indicated “almost every day” or “every day” in response to one of the three statements in the emotional well-being dimension of the scale, and those who selected “almost every day” or “every day” in 6 of the 11 statements in the psychological and social well-being dimension, were classified as having good well-being. Conversely, individuals who selected “never” or “once or twice” in one of the three statements in the emotionality dimension of the scale, and those who selected “never” or “once or twice” in 6 of the 11 statements in the psychological and social well-being dimension, were categorized as having poor well-being. Other states indicate normal mental health. The reliability coefficients of the scale were found to be 0.84, 0.78, and 0.85 for the three subscales and 0.90 for the entire scale (34). In the present study, Cronbach’s alpha was determined to be 0.94.

Data analyses

The collected data were then subjected to analysis using SPSS version 25.0. Given that the research data were collected online, with respondents being required to complete each question before advancing to the next, no missing data were observed. The presence of outliers was assessed through the utilization of box plots, a method of graphical representation. This analysis yielded no identification of extreme values. Descriptive statistics, encompassing frequency, percentage, mean, standard deviation, minimum, median, and maximum, were employed to summarize the data. The normality of the data distribution was assessed using Shao’s skewness and kurtosis criteria, and parametric tests were applied to variables that satisfied the normality assumption.

For the purpose of group comparisons, independent samples t-tests were employed to compare two groups, while analysis of variance (ANOVA) was utilized for comparisons involving three or more independent groups. When significant differences between groups were identified, Bonferroni post hoc analysis was conducted to determine which specific pairs of groups differed significantly. Pearson correlation analysis was performed to examine the relationship between C19P-S and the independent variables. Furthermore, multiple linear regression analysis was executed for multivariate analysis using both the “enter” and “stepwise” methods. The residuals were confirmed to follow a normal distribution, linearity was assessed through residual vs. fitted plots, and homoscedasticity was evaluated through visual inspection of residual plots. The multicollinearity assumption was tested, and no issues were detected. A significance level of 0.05 was established for all statistical analyses.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

To conduct the study, we obtained legal permission from the Ministry of Health, Dokuz Eylul University Research and Practice Hospital, and Dokuz Eylül University Non-Interventional Research Ethics Committee (Date: 15.03.2021, Decision Number: 2021/09-10), as well as from the scale owners. Nurses who volunteered to participate in the study provided informed consent through the Google Forms system.

Results

Descriptive data

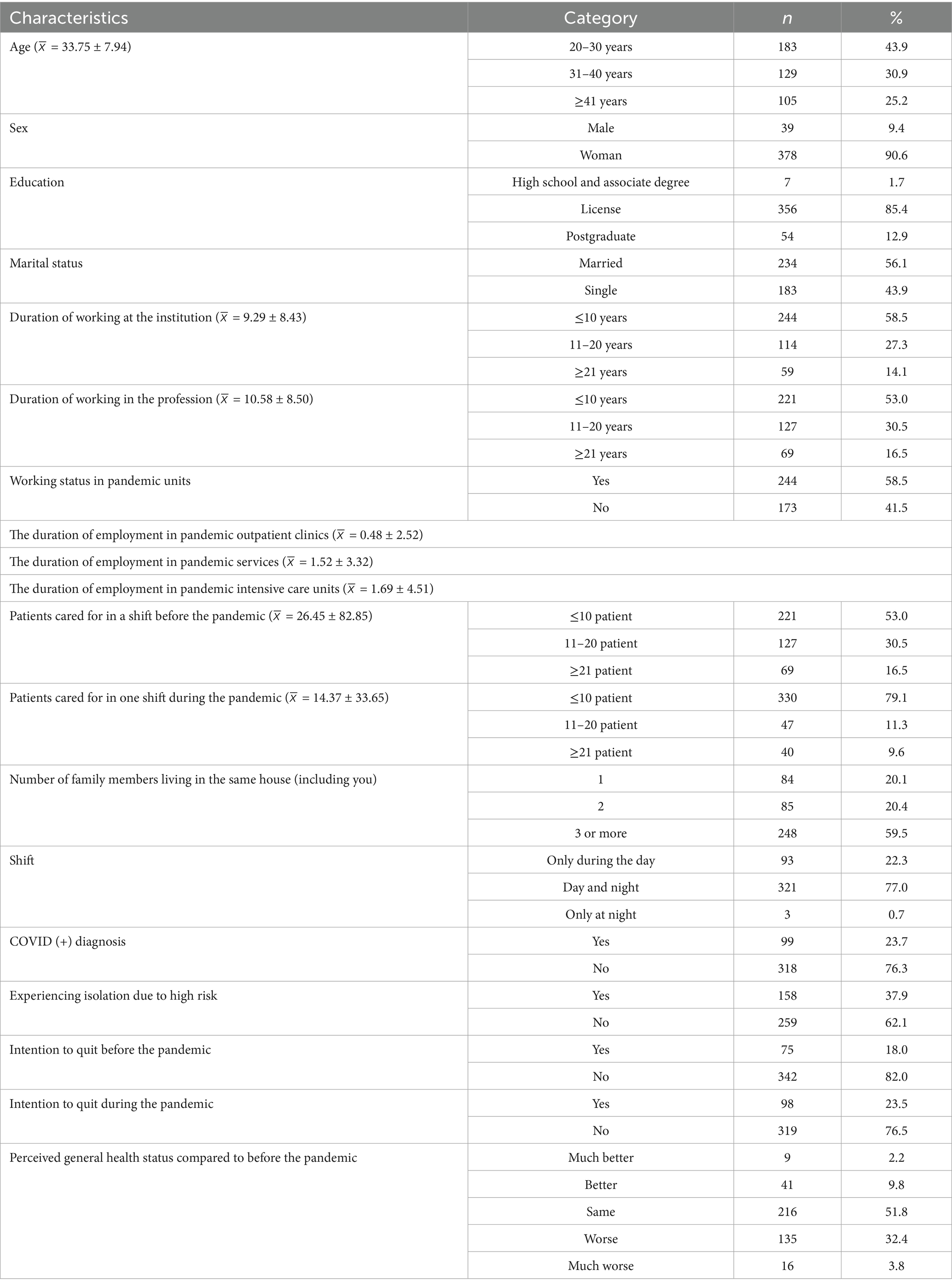

The sociodemographic and job characteristics of the nurses during the pandemic are presented in Table 1.

The mean age of the nurses participating in the study was 33.75 years (±7.94 years), with a range from 22 to 55 years. The majority of the nurses were female (90.6%), had a university degree (85.4%), and were married (56.1%). The average duration of employment at the institution was 9.29 years (±8.43), and the average duration of employment in the profession was 10.58 years (±8.50). The majority of the participants (58.5%) were employed in pandemic units. The average duration of nurses working in pandemic outpatient clinics was 0.48 ± 2.52 months, the average duration of nurses working in pandemic intensive care units was 1.52 ± 3.32 months, and the average duration of nurses working in pandemic services was 1.69 ± 4.51 months. The mean number of patients cared for during a shift before the pandemic was 26.45 ± 82.85, while the mean number of patients cared for during a shift during the pandemic was 14.37 ± 33.65. It was determined that more than half of the participants resided with three or more individuals (maximum: 6, mean: 2.77 ± 1.25, 59.5%). Furthermore, 77% of the participants reported working both day and night shifts. The majority (76.3%) of these participants had been diagnosed with COVID-19, and the majority of them were isolated due to high-risk contact (62.1%). Moreover, 82% of nurses had previously expressed their intention to resign before the pandemic, and 76.5% indicated a similar intention during the pandemic. Furthermore, the data indicates that more than half of the nurses reported no change in their general health status before and during the pandemic, while more than one-third indicated a deterioration in their health (36.2%) (Table 1).

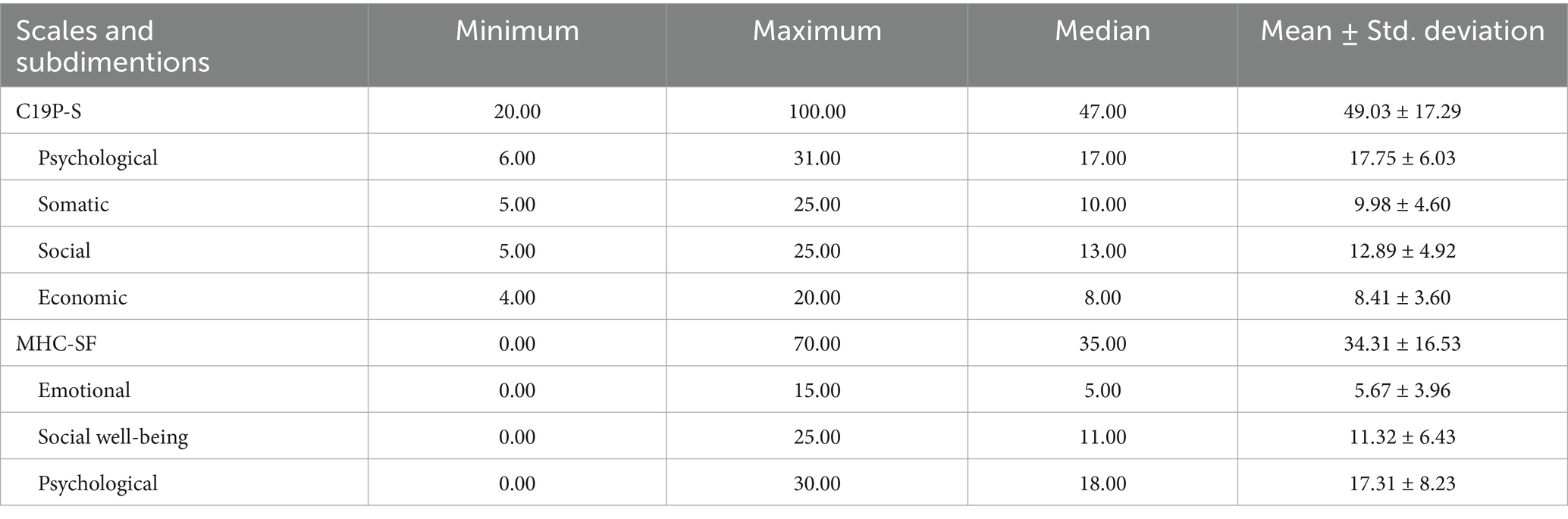

The findings related to the evaluation of COVID-19 phobia and mental health among the nurses participating in the study are presented in Table 2.

The mean C19P-S score of the nurses was 49.03 ± 17.29, and their mean MHC-SF score was 34.31 ± 16.53. The nurses demonstrated average scores of 17.75 ± 6.03 in the psychological subdimension of the C19P-S, 9.98 ± 4.60 in the somatic subdimension, 12.89 ± 4.92 in the social subdimension, and 8.41 ± 3.60 in the economic subdimension (Table 2).

When the MHC-SF subdimensions were categorized and examined, nearly half of the nurses (46.8%) experienced languishing in the “emotional” subdimension. According to the subdimensions of “social well-being” and “psychological” dimensions, 42.4% of the nurses exhibited normal mental health, while 25% were classified as languishing.

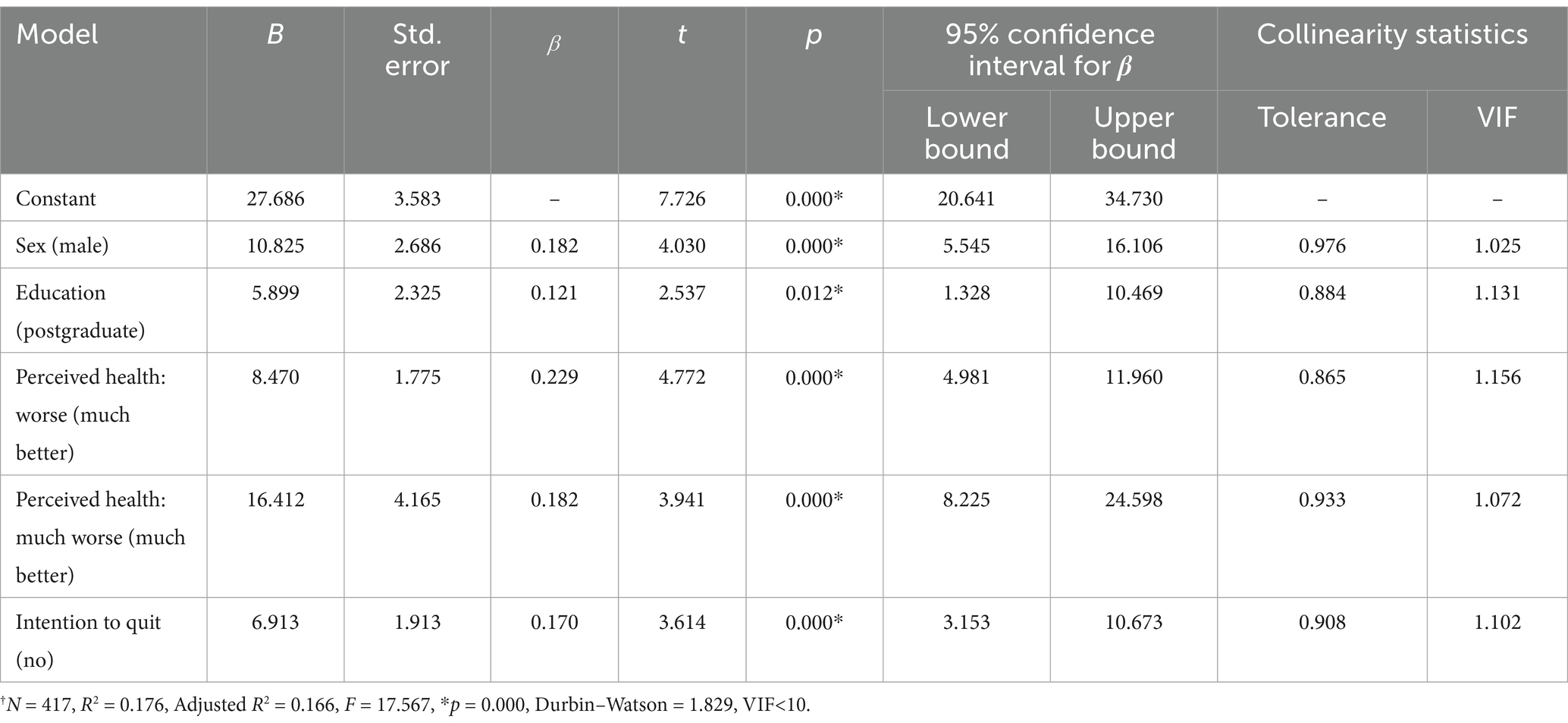

Multiple regression analysis was conducted using the enter method to assess the impact of 17 independent variables, mental health continuity, and subdimension scores on the C19P-S scores of the nurses. While a statistically significant model was established (p < 0.05; F = 4.841; Durbin–Watson = 1.782), the regression analysis was repeated using the stepwise method to ensure that significant variables remained in the model and to address the issue of multicollinearity (VIF > 10). The final model revealed that factors such as sex, educational attainment, perception of general health status before the pandemic, and the decision to discontinue employment during the pandemic collectively accounted for 17% of the variance in the manifestation of fear associated with the novel virus. However, it is noteworthy that for 83% of the participants, the incidence of the virus was influenced by other variables (see Table 3).

The mean C19P-S score of female nurses was 10.825 points higher than that of male nurses. Furthermore, nurses with an undergraduate education exhibited a mean C19P-S score that was 5.899 points higher than nurses with a graduate education. In addition, nurses with “worse” and “much worse” health statuses before the pandemic exhibited mean C19P-S scores that were 8.470 and 16.412 points higher, respectively, compared to those with “much better” health status. Lastly, nurses who expressed intentions to resign during the pandemic exhibited a mean C19P-S score that was 6.913 points higher compared to those who did not intend to resign (see Table 3).

Discussion

Nurses working during the COVID-19 pandemic have faced various psychological challenges, including fear, stress, anxiety, and mental health issues (10, 11, 15, 16). These difficulties impact the well-being of healthcare professionals and have also posed considerable challenges to the effective management of patient care and workforce planning (34). Moreover, understanding these challenges is crucial for informing interventions that support nurses’ psychological well-being.

This study explores nurses’ experiences of fear and mental health during the pandemic, as well as the factors predicting COVID-19-related fear. A study by Gholampour et al. (35) revealed that the prevalence of COVID-19 phobia varied across studies and was particularly high among healthcare professionals, especially nurses. Similarly, a study conducted in Saudi Arabia reported that 80.3% of nurses experienced COVID-19 phobia (36). Fronda and Labrague (16) also found that more than half of nurses exhibited symptoms of COVID-19 phobia.

In the present study, nurses were found to have a high level of COVID-19 phobia. While psychological and social subdimension scores were elevated, moderate levels of corona phobia were observed in the somatic and economic subdimensions. Two studies conducted in Turkey with intensive care nurses and nursing students yielded similar findings regarding total Coronaphobia Scale scores and subdimension means (21, 37). These results suggest that while nurses are affected across all dimensions, psychological and social impacts are particularly pronounced. Being on the front lines, constantly dealing with social distancing measures, and facing “stay-at-home” restrictions may have contributed to these findings. Korkut (38) also demonstrated that healthcare workers exhibited heightened levels of corona phobia. Although the prevalence of COVID-19 phobia among nurses has been well-documented in the literature, it is possible that phobic reactions may intensify during epidemics. Contributing factors include direct contact with COVID-19 patients, limited access to PPE, quarantine conditions, feelings of hopelessness, and burnout (36, 38–40).

The findings of this study indicated that nurses’ mental health was at a moderate level. A significant proportion exhibited symptoms of emotional languishing, while a notable segment also experienced psychological and social languishing. These results align with those of a study conducted with intensive care nurses in Turkey (37). Similarly, a study in Italy reported that healthcare workers had moderate mental health, though a smaller proportion (8.9%) experienced mental languishing (28). Differences in epidemic management strategies across countries may have influenced these variations. The existing literature frequently examines stress, depression, anxiety, and burnout as key indicators of mental health (41, 42). A national study in the United States found that the vast majority of nurses (84.7%) experienced moderate burnout, while nearly half exhibited moderate to severe symptoms of depression (44.6%) and post-traumatic stress (46.7%) (39). Strengthening resilience and enhancing mentalizing capacity among healthcare workers have been recognized as crucial in mitigating the adverse psychological effects of the pandemic, including anxiety, stress, and depression (43). Taken together, these findings emphasize the importance of supporting nurses’ mental health through targeted interventions and institutional policies.

In the context of caring for COVID-19 patients, factors such as life-threatening situations, separation from home, quarantine practices, and ethically challenging decisions have been shown to significantly impact nurses’ mental health (39, 41). However, the extent of these effects varies depending on factors such as geographical location, sample size, institutional framework, and working conditions.

To the best of our knowledge, very few studies have specifically examined the predictors of corona phobia among nurses (44, 45). In this study, sex, educational status, perceived general health status before the pandemic, and intention to quit were significant predictors of corona phobia, collectively explaining 17% of the variance. While the regression model is a major strength, the low explained variance represents a limitation that must be acknowledged. A substantial proportion of the variance (83%) remains unexplained, suggesting the role of additional unmeasured factors. Potential contributors include institutional support, access to PPE, pre-existing mental health conditions, social support outside work, individual resilience, and media exposure (12, 18–20, 46).

Evidence from the literature further supports the psychological impact of COVID-19 fear. A meta-analysis by Şimşir et al. (46) reported strong associations between fear of COVID-19 and anxiety, traumatic stress, and distress, as well as moderate associations with stress and depression in the general population. Lin et al. (12) found that social media use and misunderstanding of COVID-19 were linked to increased psychological distress. Yıldırım and Güler (18) highlighted that perceived health, self-efficacy, and preventive behaviors influenced mental health outcomes among Turkish healthcare workers. Eder et al. (19) demonstrated that individual and environmental factors predicted fear and perceived health across countries, and Balaban and Potas (20) showed that fear of illness, virus evaluation, and quality of life significantly affected social anxiety and fear in patients with chronic conditions.

A separate study identified gender, marital status, job status, and personal resilience as significant predictors of corona phobia, accounting for 15% of the variance (44). Additionally, previous research has highlighted hygiene habits as a key factor influencing COVID-19 phobia (47) Similarly, a study conducted with nursing students found that factors such as experiencing symptoms of the virus, the loss of a relative or acquaintance due to COVID-19, fear of caring for infected patients, lack of social distancing, and shared living spaces (e.g., toilets, elevators) contributed to corona phobia, explaining 35% of the variance (21). Furthermore, while some studies suggest that women tend to experience higher levels of fear compared to men (46), others indicate that sex is not a significant differentiating factor (35). Collectively, these findings underscore that nurses’ corona phobia is a multidimensional phenomenon shaped by individual, occupational, and environmental determinants. It is hypothesized that higher education levels foster professionalism and better information processing, which may aid in managing COVID-19-related fears. Nurses who perceive their health status as poor may experience heightened concern about their future well-being. Nurses contemplating resignation may experience heightened corona phobia, possibly due to exposure to patient mortality or the loss of colleagues, further amplified by extensive media coverage.

Strengths and limitations of the study

This study offers significant insights into the prevalence of fear surrounding the COVID-19 and the mental health status of nurses, underscoring the profound impact of the pandemic on healthcare professionals who play a pivotal role in public health maintenance. As with the general population, nurses have experienced a variety of fears during the pandemic; however, their role imposes unique demands on their mental and emotional well-being. While the study identifies predictive factors contributing to the development of fear of the novel virus, the use of nonprobability sampling may introduce biases that limit the findings’ generalizability. A comprehensive understanding of corona phobia necessitates the exploration of potential confounding factors, including the workplace environment and access to mental health resources. Future research endeavors should prioritize the incorporation of larger samples and the implementation of confounder control mechanisms to enhance the robustness of the findings. It is incumbent upon policymakers to devise targeted interventions to address epidemic-specific phobias, thereby promoting the mental health and well-being of nurses and ensuring their capacity to deliver essential care during public health crises.

Conclusion

This study underscores the significant impact of COVID-19-related fear and anxiety on nurses’ psychological well-being. Nurses who perceive their health as poor and those contemplating resignation were identified as particularly vulnerable to heightened levels of COVID-19-related fear. Based on the predictor variables identified in this study—female gender, undergraduate education, poorer perceived general health, and intention to quit—there is a clear need for targeted interventions tailored to at-risk groups.

Specifically, high-risk nurses should have access to structured psychological support programs, such as cognitive-behavioral therapy and resilience training (12, 18). Priority should be given to female nurses and those with perceived poor health. For nurses considering resignation during the pandemic, retention-focused strategies addressing pandemic-specific concerns—such as provision of mental health support, flexible scheduling, access to adequate personal protective equipment, and mentoring opportunities—are essential (19, 47). Moreover, healthcare organizations should cultivate empowering work environments characterized by transparent communication, sufficient resource allocation, and readily accessible mental health services. Complementary educational initiatives and structured social support mechanisms can further enhance nurses’ coping abilities, resilience, and overall well-being.

The integrated implementation of these measures is expected to mitigate COVID-19-related fear, strengthen nurses’ psychological well-being, and improve both nursing and patient care outcomes. This evidence-based approach provides a comprehensive framework for policymakers and healthcare administrators to guide interventions during the current pandemic as well as in future public health crises.

Data availability statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

Ethics statement

The studies involving humans were approved by Dokuz Eylul University Research and Practice Hospital, Non-Interventional Research Ethics Committee. The studies were conducted in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. The participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study.

Author contributions

MY: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Resources, Software, Validation, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. EY: Investigation, Methodology, Resources, Validation, Writing – review & editing. SS: Conceptualization, Methodology, Supervision, Validation, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declare that no financial support was received for the research and/or publication of this article.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank all the nurses who participated and contributed to our study.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The authors declare that no Gen AI was used in the creation of this manuscript.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

1. World Health Organization. WHO calls for healthy, safe and decent working conditions for all health workers, amidst covid-19 pandemic. (2020). Available online at: https://www.who.int/news/item/28-04-2020-20200428_protect_workers (Accessed October 13, 2025).

2. World Health Organization. WHO covid-19 dashboard. (2024). Available online at: https://data.who.int/dashboards/covid19/cases?n=c (Accessed July 31, 2024).

3. Turkish Ministery of Health. COVID-19 informations plattform (2024). Available online at: https://covid19.saglik.gov.tr/ (Accessed October 13, 2025).

4. Brooks, SK, Webster, RK, Smith, LE, Woodland, L, Wessely, S, Greenberg, N, et al. The psychological impact of quarantine and how to reduce it: rapid review of the evidence. Lancet. (2020) 395:912–20. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30460-8

5. Kisely, S, Warren, N, McMahon, L, Dalais, C, Henry, I, and Siskind, D. Occurrence, prevention, and management of the psychological effects of emerging virus outbreaks on healthcare workers: rapid review and meta-analysis. BMJ. (2020) 369

6. Vindegaard, N, and Benros, ME. COVID-19 pandemic and mental health consequences: systematic review of the current evidence. Brain Behav Immun. (2020) 89:531–42. doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2020.05.048

7. Asmundson, GJ, and Taylor, S. Coronaphobia: fear and the 2019-nCoV outbreak. J Anxiety Disord. (2020) 70:102196. doi: 10.1016/j.janxdis.2020.102196

8. Javanmardi, F, Keshavarzi, A, Akbari, A, Emami, A, and Pirbonyeh, N. Prevalence of underlying diseases in died cases of COVID-19: a systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS One. (2020) 15:e0241265. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0241265

9. Arpaci, I, Karataş, K, and Baloğlu, M. The development and initial tests for the psychometric properties of the covid-19 phobia scale. Pers Individ Dif. (2020) 164:110108. doi: 10.1016/j.paid.2020.110108

10. Chen, Q, Liang, M, Li, Y, Guo, J, Fei, D, Wang, L, et al. Mental health care for medical staff in China during the covid-19 outbreak. Lancet Psychiatry. (2020) 7:e15–6. doi: 10.1016/S2215-0366(20)30078-X

11. Huang, L, Lin, G, Tang, L, Yu, L, and Zhou, Z. Special attention to nurses’ protection during the covid-19 epidemic. Crit Care. (2020) 24:120. doi: 10.1186/s13054-020-2841-7

12. Lin, CY, Broström, A, Griffiths, MD, and Pakpour, AH. Investigating mediated effects of fear of COVID-19 and COVID-19 misunderstanding in the association between problematic social media use, psychological distress, and insomnia. Internet Interv. (2020) 21:100345. doi: 10.1016/j.invent.2020.100345

13. International Council of Nurses. CN confirms 1,500 nurses have died from COVID-19 in 44 countries and estimates that healthcare worker COVID-19 fatalities worldwide could be more than 20,000. (2020). Available online at: https://www.icn.ch/news/icn-confirms-1500-nurses-have-died-covid-19-44-countries-and-estimates-healthcare-worker-covid (Accessed October 13, 2025).

14. Turkish Medical Association. Covid-19 pandemic two-month evaluation report. (2020). Available online at: https://www.ttb.org.tr/userfiles/files/covid19-rapor.pdf (Accessed October 13, 2025).

15. Editorial the Lancet. COVID-19: protecting health-care workers. Lancet. (2020) 21:922. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30644-9

16. Fronda, DC, and Labrague, LJ. Turnover intention and coronaphobia among frontline nurses during the second surge of covid-19: the mediating role of social support and coping skills. J Nurs Manag. (2022) 30:612–21. doi: 10.1111/jonm.13542

17. Greenberg, N, Docherty, M, Gnanapragasam, S, and Wessely, S. Managing mental health challenges faced by healthcare workers during covid-19 pandemic. BMJ. (2020) 368:m1211. doi: 10.1136/bmj.m1211

18. Yıldırım, M, and Güler, A. COVID-19 severity, self-efficacy, knowledge, preventive behaviors, and mental health in Turkey. Death Stud. (2022) 46:979–86. doi: 10.1080/07481187.2020.1793434

19. Eder, SJ, Steyrl, D, Stefanczyk, MM, Pieniak, M, Martinez Molina, J, Pešout, O, et al. Predicting fear and perceived health during the COVID-19 pandemic using machine learning: a cross-national longitudinal study. PLoS One. (2021) 16:e0247997. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0247997

20. Balaban, FE, and Potas, N. Determining the effect of fear of illness and virus evaluation and quality of life on diagnosis of social phobia in patients with chronic disease: using machine learning approaches. Florence Nightingale J Nurs. (2024) 32:312–21. doi: 10.5152/FNJN.2024.24073

21. Kisely, S, Warren, N, McMahon, L, Dalais, C, Henry, I, and Siskind, D (2020). Occurrence, prevention, and management of the psychological effects of emerging virus outbreaks on healthcare workers: rapid review and meta-analysis. BMJ. 369:1–11.

22. Amin, S. The psychology of coronavirus fear: are healthcare professionals suffering from corona-phobia? Int J Healthc Manag. (2020) 13:249–56. doi: 10.1080/20479700.2020.1765119

23. Amin, S. Why ignore the dark side of social media? A role of social media in spreading corona-phobia and psychological well-being. Int J Ment Health Promot. (2020) 22:29–38. doi: 10.32604/IJMHP.2020.011115

24. Bashar, SI, Inda, A, and Maıwada, RM. Perceived effects of corona-phobia and movement control order on Nigerian postgraduate students in University Teknologi Malaysia. Asia Proc Soc Sci. (2020) 6:117–20. doi: 10.31580/apss.v6i2.1307

25. da Silva, BM, Leite, ACAB, García-Vivar, C, Nascimento, LC, and Marcon, SS. The experience of coronaphobia among health professionals and their family members during covid-19 pandemic: a qualitative study. Collegian. (2022) 29:288–95. doi: 10.1016/j.colegn.2022.03.006

26. Labrague, LJ. COVID-19 phobia, loneliness, and dropout intention among nursing students: the mediating role of social support and coping. Curr Psychol. (2024) 43:16881–9. doi: 10.1007/s12144-023-04636-8

27. Power/Sample Size Calculator. Inference for a mean: comparing a mean to a known value. Available online at: https://www.stat.ubc.ca/~rollin/stats/ssize/n1.html (Accessed October 13, 2025).

28. Bassi, M, Negri, L, Delle Fave, A, and Accardi, R. The relationship between post-traumatic stress and positive mental health symptoms among health workers during covid-19 pandemic in Lombardy, Italy. J Affect Disord. (2021) 280:1–6. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2020.11.065

29. Arrow, K, Resnik, P, Michel, H, Kitchen, C, Mo, C, Chen, S, et al. Evaluating the use of online self-report questionnaires as clinically valid mental health monitoring tools in the clinical whitespace. Psychiatry Q. (2023) 94:221–31. doi: 10.1007/s11126-023-10022-1

30. Zimmerman, M. The value and limitations of self-administered questionnaires in clinical practice and epidemiological studies. World Psychiatry. (2024) 23:210–2. doi: 10.1002/wps.21191

31. Romero, CS, Otero, M, Lozano, M, Delgado, C, Benito, A, Catala, J, et al. Rapid and sustainable self-questionnaire for large-scale psychological screening in pandemic conditions for healthcare workers. Front Med Lausanne. (2023) 9:969734. doi: 10.3389/fmed.2022.969734

32. Keyes, CL, Wissing, M, Potgieter, JP, Temane, M, Kruger, A, and Van Rooy, S. Evaluation of the mental health continuum–short form (mhc–sf) in setswana-speaking south Africans. Clin Psychol Psychother. (2008) 15:181–92. doi: 10.1002/cpp.572

33. Demirci, İ, and Akın, A. The validity and reliability of the mental health continuum short form. J Faculty Educ Sci. (2015) 48:49–64. doi: 10.1501/Egifak_0000001352

34. Williams, GA, Ziemann, M, Chen, C, Forman, R, Sagan, A, and Pittman, P. Global health workforce strategies to address the covid-19 pandemic: learning lessons for the future. Int J Health Plann Manag. (2024) 39:888–97. doi: 10.1002/hpm.3762

35. Gholampour, MH, Zamani, F, Bakhshalizade Rashti, S, Hajehforoush, N-S, Dadkhah-Tehrani, M, Zare-Kaseb, A, et al. Corona phobia among nurses: a narrative review. J Nurs Rep Clin Pract. (2023) 1:84–8. doi: 10.32598/JNRCP.23.41

36. Aljemaiah, AI, Alyami, AA, Alotaibi, FS, and Osman, M. The prevalence of coronaphobia among nursing staff in Saudi Arabia. J Family Med Prim Care. (2022) 11:1288–91. doi: 10.4103/jfmpc.jfmpc_1412_21

37. Bulut, A, Yılmaz, BE, and Yüksel, A. Coronaphobia, job satisfaction, and languishing levels of intensive care nurses: a cross-sectional and correlational study. J Turk Soc Intens Care. (2023) 21:297–305. doi: 10.4274/tybd.galenos.2023.60252

38. Korkut, S. Research of burnout, coronaphobia, hopelessness, and psychological resilience levels in healthcare workers during the covid-19 pandemic. Int J Med Sci. (2022) 11:1569–76. doi: 10.5455/medscience.2022.08.174

39. Anozie, OB, Nwafor, JI, Nwokporo, EI, Esike, CU, Ewah, RL, Eze, JN, et al. Mental health impact of covid-19 pandemic on health care workers in Ebonyi state, southeast, Nigeria. Int J Innov Res Med Sci. (2020) 5:400–406. doi: 10.23958/ijirms/vol05-i09/955

40. Zare-Kaseb, A, Dadkhah-Tehrani, M, Nazari, AM, Zamani, F, and Bakhshalizade Rashti, S. The relationship between corona phobia and burnout in critical care nurses during the COVID-19 pandemic: a narrative review. J Nurse Rep Clin Pract. (2023) 1:138–42. doi: 10.32598/JNRCP.23.47

41. Guttormson, JL, Calkins, K, McAndrew, N, Fitzgerald, J, Losurdo, H, and Loonsfoot, D. Critical care nurse burnout, moral distress, and mental health during the covid-19 pandemic: a United States survey. Heart Lung. (2022) 55:127–33. doi: 10.1016/j.hrtlng.2022.04.015

42. Varghese, A, George, G, Kondaguli, SV, Naser, AY, Khakha, DC, and Chatterji, R. Decline in the mental health of nurses across the globe during COVID-19: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Glob Health. (2021) 11:05009. doi: 10.7189/jogh.11.05009

43. Safiye, T, Gutić, M, Dubljanin, J, Stojanović, TM, Dubljanin, D, Kovačević, A, et al. Mentalizing, resilience, and mental health status among healthcare workers during the covid-19 pandemic: a cross-sectional study. Int J Environ Res Public Health. (2023) 20:5594. doi: 10.3390/ijerph20085594

44. Labrague, LJ, and De Los Santos, JAA. Prevalence and predictors of coronaphobia among frontline hospital and public health nurses. Public Health Nurs. (2021) 38:382–9. doi: 10.1111/phn.12841

45. Akman, EK, Gür, S, and Özbaş, A. Determination of the relationship between the coronavirus-2019 phobia level and hygiene behaviors of nurses. Mediterr Nurs Midwifery. (2023) 3:72–80. doi: 10.4274/MNM.2023.22122

46. Şimşir, Z, Koç, H, Seki, T, and Griffiths, MD. The relationship between fear of COVID-19 and mental health problems: a meta-analysis. Death Stud. (2022) 46:515–23. doi: 10.1080/07481187.2021.1889097

Keywords: COVID-19, corona phobia, nurses, mental health, pandemic, well-being

Citation: Yildirim M, Yildiz E and Seren Intepeler S (2025) Corona phobia and mental health among nurses: identifying determinants in a cross-sectional survey. Front. Public Health. 13:1681478. doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2025.1681478

Edited by:

Krystyna Kowalczuk, Medical University of Bialystok, PolandReviewed by:

Catherine Bodeau-Pean, Independent Researcher, Paris, FranceNihan Potas, Ankara Haci Bayram Veli University, Türkiye

Copyright © 2025 Yildirim, Yildiz and Seren Intepeler. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Menevse Yildirim, bWVuZXZzZXlpbGRpcmltQG11LmVkdS50cg==

Menevse Yildirim

Menevse Yildirim Emre Yildiz

Emre Yildiz Seyda Seren Intepeler

Seyda Seren Intepeler