- 1School of Public Administration, Shandong Normal University, Jinan, China

- 2Department of Human Resources, Jinan Central Hospital, Jinan, China

- 3School of Political Science and Public Administration, Shandong University, Qingdao, China

- 4School of Management, Shandong University of Traditional Chinese Medicine, Jinan, China

- 5School of Medical Management, Shandong First Medical University, Taian, China

- 6Dalla Lana School of Public Health, University of Toronto, Toronto, ON, Canada

Introduction: Primary healthcare workers (PHCWs) are crucial to the healthcare system, as they directly impact the delivery of essential health services. Their job performance is influenced by various types of organizational commitment, but the effects of these commitments are not fully understood. This study aims to explore how four types of organizational commitment (affective, normative, economic, and opportunity) affect job performance among PHCWs, using Self-Determination Theory to examine motivation internalization as a mediating factor.

Methods: A cross-sectional survey of 870 PHCWs from 38 primary healthcare institutions was conducted. Hierarchical regression analysis was used to explore the relationships between commitment types, motivation internalization, and job performance.

Results: Affective and normative commitments positively predicted job performance, with motivation internalization partially mediating this relationship. Opportunity commitment negatively predicted job performance, mediated by reduced motivation internalization. Economic commitment showed no significant effect on either motivation internalization or job performance.

Discussion: The impact of organizational commitment on job performance is shaped by its motivational quality. Strengthening affective and normative commitments through supportive incentive strategies can enhance PHCWs’ performance in primary healthcare settings.

1 Introduction

Ensuring a stable and motivated primary healthcare workforce remains a persistent challenge in many low- and middle-income countries. In China, this issue is particularly severe: high turnover among primary health care workers (PHCWs) continues to undermine the accessibility and quality of community-based services (1–4). Despite ongoing policy efforts, retention strategies have primarily focused on whether PHCWs remain, rather than why they remain (5). Yet remaining in one’s role does not necessarily imply strong work motivation, as some PHCWs may stay primarily due to external constraints rather than volition, potentially undermining both job performance and long-term workforce stability (6). In this context, understanding not just how many PHCWs remain, but what drives their decision to remain is increasingly important for cultivating an engaged and sustainable primary healthcare workforce.

Organizational commitment offers a valuable perspective on the motivational bases of long-term attachment, as it reflects a sustained psychological bond between individuals and their organization and helps explain why they choose to remain (7). According to Meyer and Allen’s framework, organizational commitment consists of three dimensions (8). Affective commitment involves an employee’s emotional attachment to and identification with the organization. Normative commitment reflects a sense of moral obligation to remain with the organization. Continuance commitment refers to the perceived costs associated with leaving. Subsequent research has further refined continuance commitment into two subcomponents: economic commitment, which emphasizes financial dependence as the primary reason for remaining, and opportunity commitment, which stems from a perceived lack of better job alternatives (9, 10). This refinement has led to a four-dimensional conceptualization of organizational commitment, which has been applied in subsequent studies to examine the distinct effects of economic and opportunity commitment on work outcomes (11) and to analyze their underlying motivational bases and consequences (9). Together, these dimensions reflect different motivational bases and shape PHCWs’ work experiences in different ways. Recognizing these variations helps explain why some PHCWs remain actively engaged in their roles, while others, though equally retained, contribute only minimally.

While a substantial literature has investigated the relationship between organizational commitment and job performance, findings have varied considerably depending on the type of commitment (11–13). Affective commitment is consistently associated with higher performance. Normative commitment is generally positively related to performance, though its effects are often modest (14). By contrast, continuance commitment (including economic and continuous dimensions) frequently correlates weakly or even negatively with performance (15, 16). Despite the accumulated evidence linking organizational commitment to job performance, few studies have explored how different commitment types exert their effects (17–19). To address this gap, this study introduces Self-Determination Theory (SDT) as a theoretical framework to examine the motivational mechanisms through which different types of commitment influence job performance (20, 21). SDT conceptualizes motivation as a continuum ranging from controlled form to full autonomy, with more autonomous forms consistently linked to better performance, persistence, and well-being (22–24). The shift from controlled to autonomous motivation is known as motivation internalization—a core process whereby external regulations are gradually integrated into one’s sense of self (21). According to SDT, motivation internalization is facilitated when individuals experience support for three basic psychological needs: autonomy, competence, and relatedness (22).

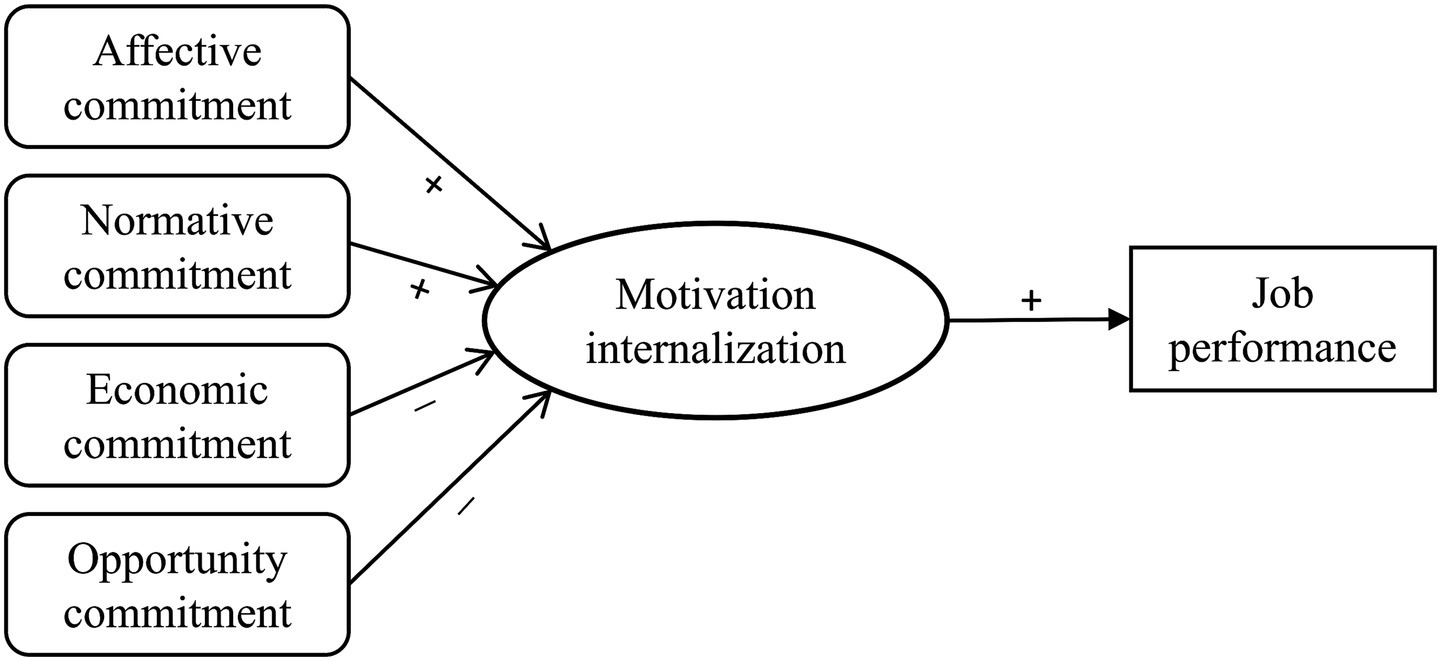

Drawing on SDT, we posit that each commitment type influences motivation internalization by supporting or frustrating the satisfaction of basic psychological needs. Affective commitment, which reflects emotional attachment to the organization, plays a key role in satisfying the need for relatedness—by fostering a sense of belonging, trust, and identification with colleagues and patients. This relational embeddedness can promote motivation internalization (8). Normative commitment, although obligation-based, may also support internalization if the perceived obligations are self-endorsed and aligned with personal values, thereby satisfying the need for autonomy (25). In contrast, opportunity and economic commitment are typically rooted in external constraints—such as limited alternatives or financial dependence—which may frustrate the need for autonomy and, in some cases, competence. As a result, these forms of commitment are likely to impede the internalization process (26). Moreover, prior research grounded in SDT has consistently shown that more autonomous forms of motivation are linked to higher levels of job performance (23). Since motivation internalization reflects the degree to which autonomous motivation dominates work behavior (27), we expect it to positively predict job performance. Based on the above reasoning, we propose a conceptual model (Figure 1) in which the four commitment dimensions influence job performance through their different effects on motivation internalization.

Figure 1. Conceptual model illustrating hypothesized relationships between commitment types, motivation internalization, and job performance.

This study empirically tests the proposed model based on survey data from PHCWs in Shandong Province, China. It offers a theoretical explanation for why equally committed PHCWs may perform differently, by clarifying how distinct types of commitment differentially influence motivation internalization. The findings also offer practical implications for improving provider retention and enhancing service delivery in the primary healthcare context.

2 Methods

2.1 Study design and sampling

This cross-sectional study was conducted in 2021 among PHCWs in Shandong Province, China, using a structured questionnaire. A multistage cluster sampling strategy was adopted to ensure geographic and economic representativeness. Three cities (Qingdao, Dongying, and Zaozhuang) were first selected based on regional diversity, followed by the random selection of four districts or counties within each city. Subsequently, 3–4 primary health institutions were chosen per district or county, yielding a total of 38 institutions (18 community health service centers and 20 township hospitals). All PHCWs on duty during the survey period were invited to participate.

A total of 870 valid questionnaires were returned, yielding a high response rate of 92.3%. The sample comprised 193 males (22.2%) and 677 females (77.8%). Participants ranged in age from under 30 (21.4%) to 50 years and older (8.6%), with the largest group aged 40–49 (37.8%). In terms of professional roles, 40.3% were physicians, 29.5% nurses, 15.8% medical technicians, 8.3% public health staff, and 6.1% administrative or logistical personnel.

2.2 Measure

2.2.1 Organizational commitment

Organizational commitment was measured using an adapted scale developed for PHCWs (28), encompassing four dimensions: affective, normative, economic, and opportunity commitment. Each dimension was assessed with three items (12 items in total) on a 5-point Likert scale (1 = strongly disagree, 5 = strongly agree), yielding scores from 3 to 15, with higher scores indicating stronger commitment. The Cronbach’s alpha coefficients for the four dimensions were 0.903 for affective commitment, 0.862 for normative commitment, 0.849 for economic commitment, and 0.758 for opportunity commitment, indicating acceptable internal consistency. Prior research provides structural validity based on factor analysis (15) and convergent, discriminant, and criterion validity across established antecedents and outcomes (11).

2.2.2 Motivation internalization

Motivation internalization was assessed based on the structure of work motivation outlined in SDT. Work motivation was measured using an adapted version of the Chinese Work Motivation Scale for Healthcare Workers (27, 29). The scale comprises 18 items covering five dimensions: amotivation (3 items, Cronbach α = 0.797), external regulation (6 items, Cronbach α = 0.754), introjected regulation (3 items, Cronbach α = 0.887), integrated regulation (3 items, Cronbach α = 0.876), and intrinsic motivation (3 items, Cronbach α = 0.769). All items were rated on a 7-point Likert scale (1 = completely disagree, 7 = completely agree), with higher scores indicating greater intensity of motivation. Prior validation of the MWMS has demonstrated robust structural validity and cross-cultural measurement invariance across languages and countries, supporting its applicability in diverse contexts (27). In addition, a recent study among Chinese primary healthcare workers employed the adapted Chinese version, further supporting its cross-cultural applicability (29).

The degree of motivation internalization was assessed using the Self-Determination Index (SDI), which aggregates the five motivation subscales by assigning differential weights that reflect their relative position on the autonomy continuum, ranging from amotivation (the least autonomous) to intrinsic motivation (the most autonomous) (30, 31). The formula is as follows:

2.2.3 Job performance

Job performance was measured using a 10-item scale developed by Zhao et al. specifically for PHCWs in China. The same study reported a multidimensional structure with acceptable global fit indices, indicating structural validity (32). The scale assesses three dimensions of job performance: task performance, contextual performance, and learning performance. Each item was rated on a 7-point Likert scale (1 = completely disagree, 7 = completely agree), and the total score, which ranged from 10 to 70, was used as the outcome variable in this study, with higher scores reflecting better performance. The scale demonstrated excellent internal consistency, with Cronbach’s alpha coefficient of 0.909.

2.2.4 Data analysis

Descriptive statistics and Pearson correlation analyses were conducted to examine basic patterns and associations among organizational commitment, motivation internalization, and job performance. To test the mediating role of motivation internalization, we followed Baron and Kenny’s three-step approach (33). All analyses were performed using SPSS version 22.0, with statistical significance set at p < 0.05.

3 Results

3.1 Descriptive statistics

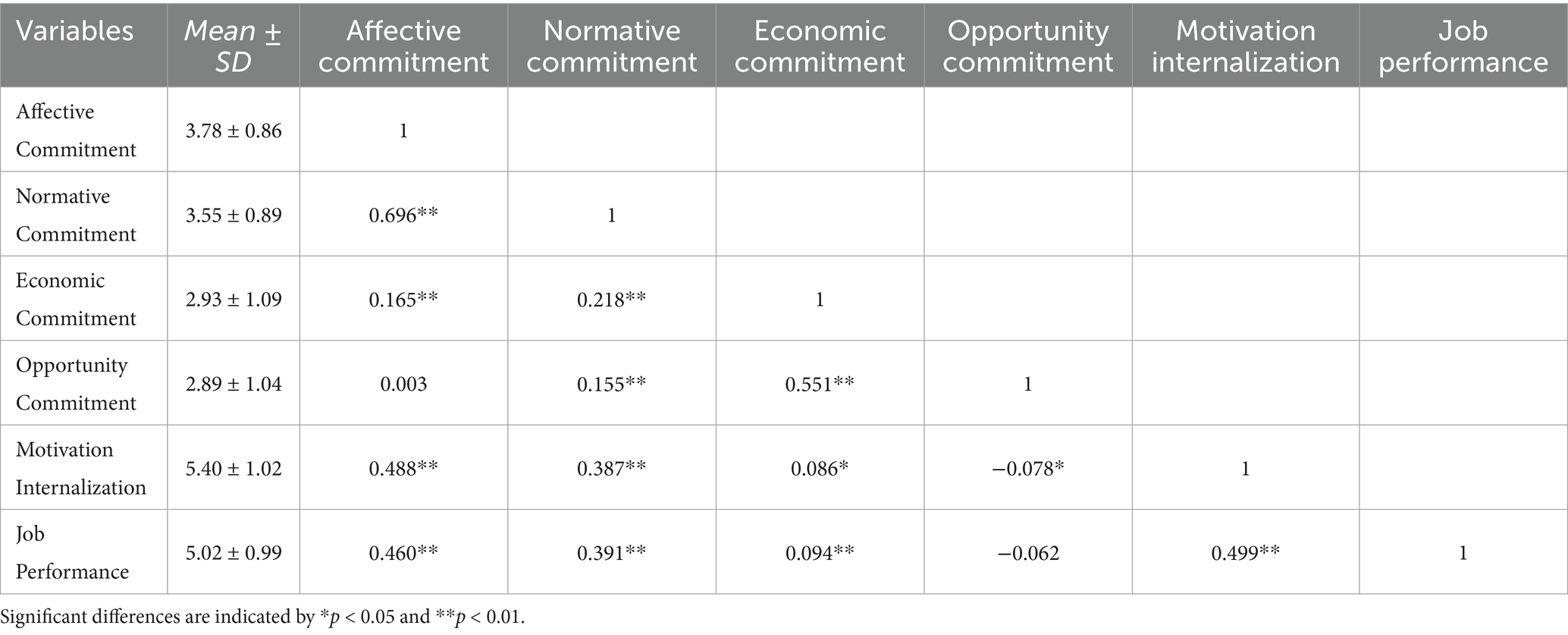

Descriptive statistics showed notable variation across the four dimensions of organizational commitment among PHCWs. On average, affective commitment received the highest score (M = 3.78, SD = 0.86), followed by normative commitment (M = 3.55, SD = 0.89). In contrast, economic commitment (M = 2.93, SD = 1.09) and opportunity commitment (M = 2.89, SD = 1.04) were relatively lower. Additionally, the average scores for motivation internalization and job performance were 5.40 (SD = 1.02) and 5.02 (SD = 0.99), respectively.

3.2 Correlation analysis

Significant correlations were observed among organizational commitment, motivation internalization, and job performance based on Pearson analysis (Table 1). Among the four commitment dimensions, affective commitment (r = 0.488, p < 0.01) and normative commitment (r = 0.387, p < 0.01) demonstrated moderate positive correlations with motivation internalization. Economic commitment was weak but significantly associated (r = 0.086, p < 0.05), whereas opportunity commitment showed a small negative correlation (r = −0.078, p < 0.05). As anticipated, motivation internalization was strongly associated with job performance (r = 0.499, p < 0.01). Affective (r = 0.460, p < 0.01) and normative commitment (r = 0.391, p < 0.01) were also positively associated with job performance. While economic commitment showed a weak positive correlation (r = 0.094, p < 0.01), opportunity commitment was not significantly associated with job performance (r = −0.062, p > 0.05).

Table 1. Correlations among organizational commitment, motivation internalization, and job performance.

3.3 Regression-based mediation analysis

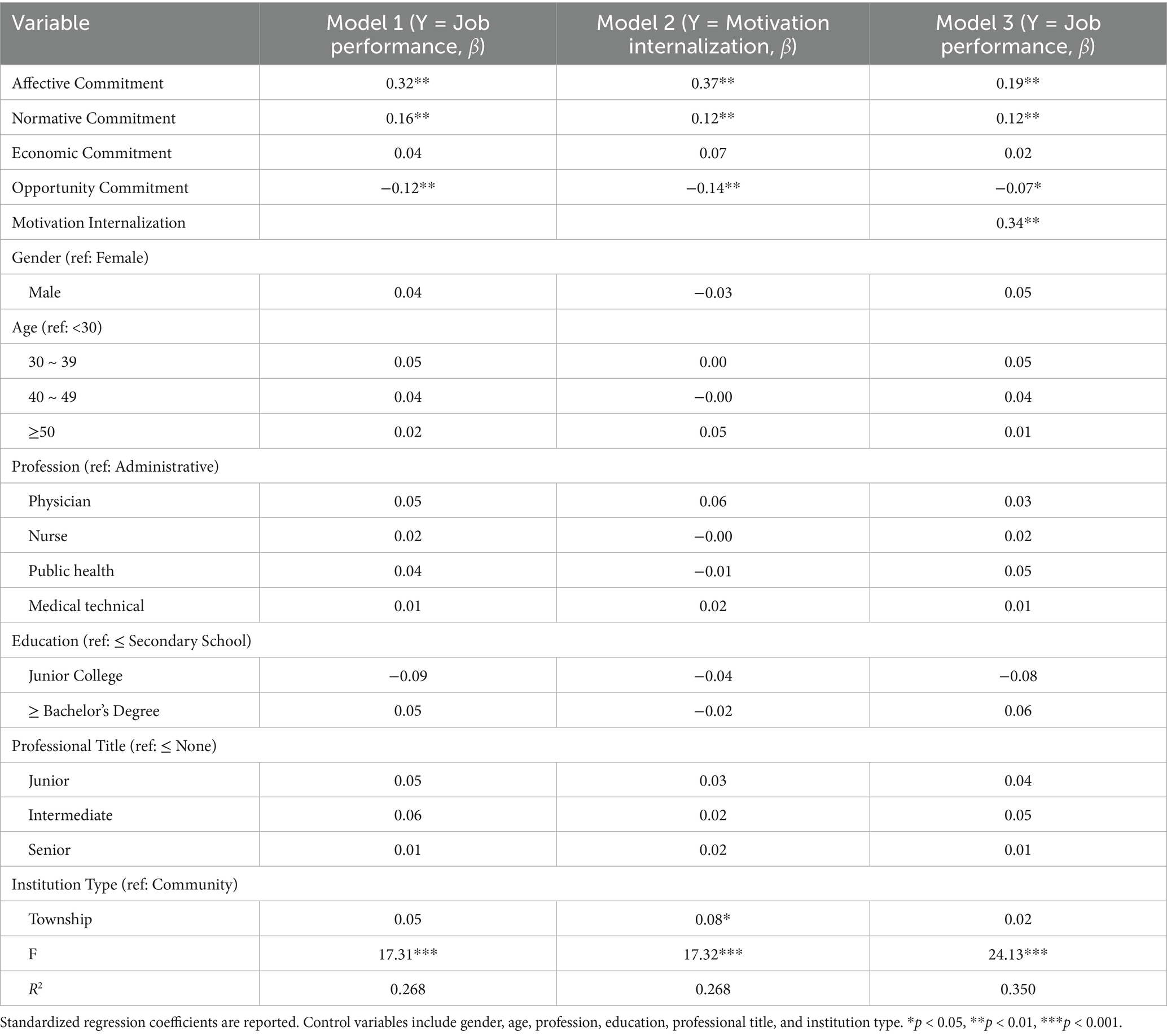

Hierarchical regression was conducted to test the hypothesized mediation model (Table 2). In Model 1, affective commitment (β = 0.32, p < 0.001), normative commitment (β = 0.16, p < 0.01), and opportunity commitment (β = −0.12, p < 0.01) significantly predicted job performance, while economic commitment showed no significant association (β = 0.04, p > 0.05).

Table 2. Regression analysis of organizational commitment, motivation internalization, and job performance.

In Model 2, motivation internalization was a significant predictor of job performance (β = 0.34, p < 0.001), supporting its potential role as a mediating variable.

After adding motivation internalization in Model 3, the effects of affective, normative and opportunity commitment were attenuated to β = 0.19 (from 0.32), β = 0.12 (from 0.16), and β = −0.07 (from −0.12), respectively, although all three remained significant (p < 0.01). This pattern suggests partial mediation, whereby these types of commitment influence performance both directly and indirectly through motivation internalization. In contrast, economic commitment remained nonsignificant across all models. Specifically, the indirect effect via motivation internalization was 0.125 for affective commitment, accounting for 39.12% of its total effect; 0.042 for normative commitment (26.59%); and −0.047 for opportunity commitment (40.94%).

Bootstrapped mediation analysis (5,000 resamples) further supported the mediating effects, with all indirect effects reaching statistical significance. The bias-corrected 95% confidence intervals excluded zero for each pathway: [0.083, 0.172] for affective commitment, [0.010, 0.076] for normative commitment, and [−0.081, −0.019] for opportunity commitment, indicating robust and consistent mediation.

4 Discussion

This study examined how distinct dimensions of organizational commitment influence job performance among PHCWs in China. Extending prior study on the commitment–performance relationship, it found that motivation internalization acts as a critical psychological mechanism through which certain types of commitment exert their effects (34, 35).

PHCWs reported the highest scores for affective and normative commitment, suggesting that many remain due to emotional attachment and perceived obligation. The prominence of affective commitment may reflect the relational continuity and community embeddedness characteristic of primary healthcare. PHCWs often serve the same patients over long periods, which fosters interpersonal trust, professional identification, and a sense of belonging (36). As these relationships are developed and maintained through their organizational roles, the emotional bonds with the community can extend to the organization. Meanwhile, the relatively high level of normative commitment may reflect PHCWs’ recognition of their essential role as gatekeepers of community health. This recognition can reinforce a strong sense of moral duty—not only to the communities they serve, but also to the organizations that enable their work (11). In addition, given that 77.8 percent of participants were women, the relatively higher levels of affective and normative commitment observed in this sample may partly reflect gender composition. Social role accounts suggest that, on average, women endorse more communal and relationship-oriented values, which can align with stronger emotional attachment and a greater sense of obligation to the organization (36). Consistent with this possibility, meta-analytic evidence suggests that women may exhibit higher affective commitment compared to men (37), and some studies also report slightly higher normative commitment among women (38, 39).

In contrast, economic and opportunity commitment were notably lower, suggesting that most PHCWs did not feel strongly constrained by financial dependency or limited alternatives. The relatively low level of economic commitment observed in this study may be partly attributable to a broader pattern identified in previous research, which shows that PHCWs often attach greater importance to non-financial incentives—such as stability, meaning, and manageable workloads—than to monetary compensation (40). Similarly, the lower level of opportunity commitment may reflect PHCWs’ limited concern with external job mobility, possibly due to job satisfaction, perceived job security, or habituated career paths that diminish the salience of alternative options.

The findings support the hypothesized pathway in which both affective and normative organizational commitment enhance job performance by promoting motivation internalization. Notably, affective commitment exerted a stronger effect on both motivation internalization and job performance compared to normative commitment. Affective commitment, rooted in emotional attachment and value identification, aligns more closely with autonomous motivation and thus showed a stronger effect. Normative commitment, driven by obligation and social expectation, may also support internalization but tend to involve more controlled regulation (41). In the primary healthcare context, where providers maintain long-term relationships with patients and are deeply rooted in local communities, emotional bonds and moral responsibility often coexist and reinforce one another (11), as evidenced by the strong positive correlation between affective and normative commitment in our findings. Under such conditions, PHCWs with high affective and normative commitment are more likely to view organizational goals as personally meaningful rather than imposed. This shift from compliance to identification fosters sustained, self-congruent motivation, which in turn supports sustained job performance.

Opportunity commitment was found to negatively affect both motivation internalization and job performance. Some PHCWs may remain in their position not by choice, but due to institutional constraints (42). This form of “passive retention” may undermine perceived autonomy and create a psychologically restrictive state. As suggested by SDT, such perceived external control reduces the likelihood of internalizing organizational goals, leading to more controlled forms of motivation and, ultimately, diminished job performance (21). Economic commitment was originally hypothesized to suppress performance by reducing the degree of motivation internalization, but the results showed no significant effect. This suggests that while financial dependence may explain continued employment, it neither energizes nor impairs motivation in this context. One possible reason is that stable income and job security are perceived as baseline conditions rather than active drivers of effort. This interpretation is consistent with Herzberg’s two-factor theory, which categorizes such factors as necessary to avoid dissatisfaction but insufficient to promote high motivation (43). In this sense, economic commitment may represent a more neutral form of attachment in terms of motivational quality: it does not facilitate internalization, but it may also avoid triggering controlled regulation.

This study advances understanding of organizational commitment by empirically comparing four distinct dimensions: affective, normative, opportunity, and economic, and uncovering the motivational mechanism through which they influence job performance. Drawing on SDT, the study confirms that different types of commitment influence motivation internalization to varying degrees. This finding underscores that the motivational quality of commitment plays a critical role in shaping behavioral effectiveness. Moreover, the study lends empirical support to a four-dimensional conceptualization of organizational commitment by distinguishing between economic and opportunity commitment. Though commonly conceptualized as a single dimension known as continuance commitment (8), these two dimensions exhibited distinct effects on motivation and performance, underscoring the theoretical and practical value of treating constraint-based commitment as a multidimensional construct.

These findings have some implications for human resource incentive policies in primary healthcare. A primary focus is to strengthen affective and normative commitment, as they support motivation internalization and improved job performance. To this end, institutions should foster psychologically supportive work environments by aligning performance management systems with autonomy and recognition, while also reinforcing daily managerial practices such as team communication, peer mentoring, and participatory decision-making. Furthermore, the negative effects associated with opportunity commitment underscore the risks of constraint-based retention, often stemming from institutional limitations such as restricted mobility or narrow promotion pathways. To address this, primary healthcare institutions should consider expanding horizontal development pathways, such as offering cross-institution rotations or diversified professional tracks. In addition, strengthening collaboration and resource sharing with higher-level hospitals can provide PHCWs with expanded professional development opportunities, without requiring formal job transfer.

Several limitations should be acknowledged. First, although the model is conceptually grounded in SDT and supported by empirical associations, the cross-sectional design limits causal interpretations of the observed relationships. In particular, self-reported measures may be subject to certain biases, such as social desirability. To strengthen causal inference and reduce potential bias, future studies should adopt longitudinal or experimental designs and incorporate more objective indicators of job performance, such as institutional or administrative records. Second, although Shandong Province shares many institutional features with other regions in China, the findings may not generalize to countries with primary healthcare systems and sociocultural environments that differ structurally from China’s. Differences in institutional arrangements, workforce policies, and cultural values may shape how organizational commitment and motivation internalization influence job performance. Future research should therefore include cross-cultural or multinational samples to enhance the external validity of findings. Third, this study primarily focuses on individual-level psychological mechanisms, without sufficiently considering institutional or organizational-level factors that may also shape job performance. Elements such as promotion systems, compensation structures, leadership styles, and governance arrangements could play a significant role in shaping how organizational commitment affects motivation internalization and job performance. Future research should therefore integrate organizational and policy-level variables, and ideally adopt multilevel research designs, to provide a more comprehensive and context-sensitive understanding of commitment dynamics in primary healthcare.

5 Conclusion

This study examined how different types of organizational commitment influence job performance among PHCWs in China, focusing on the mediating role of motivation internalization. The findings show that affective and normative commitment enhance both motivation internalization and job performance, while opportunity commitment has a negative influence and economic commitment shows no significant effect. Drawing on SDT, the study demonstrates that the impact of organizational commitment depends not just on its presence, but on the motivational quality of different commitment types—specifically, the extent to which they support internalized motivation. These insights highlight the managerial value of fostering supportive work environments that enhance affective and normative commitment and reduce opportunity commitment.

Data availability statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

Ethics statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and was approved by the Ethics Committee of Shandong First Medical University (approval number R202305160130). Written informed consent was obtained from all participants prior to their inclusion in the study. The studies were conducted in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. The participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study.

Author contributions

SZ: Conceptualization, Funding acquisition, Methodology, Writing – review & editing. TW: Data curation, Methodology, Writing – original draft. SL: Investigation, Writing – original draft. YM: Writing – original draft. YW: Conceptualization, Writing – review & editing. HM: Methodology, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. XW: Writing – review & editing, Supervision.

Funding

The author(s) declare that financial support was received for the research and/or publication of this article. This study was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (grant no. 72204150).

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

The author(s) declared that they were an editorial board member of Frontiers, at the time of submission. This had no impact on the peer review process and the final decision.

Generative AI statement

The author(s) declare that no Gen AI was used in the creation of this manuscript.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

1. Sun, Y, Wang, W, Yan, F, Xie, X, Cai, M, and Xu, F. Related factors of turnover intention among general practitioners: a cross-sectional study in 6 provinces of China. BMC Prim Care. (2025) 26:37. doi: 10.1186/s12875-025-02728-x

2. Zhang, T, Feng, J, Jiang, H, Shen, X, Pu, B, and Gan, Y. Association of professional identity, job satisfaction and burnout with turnover intention among general practitioners in China: evidence from a national survey. BMC Health Serv Res. (2021) 21:382. doi: 10.1186/s12913-021-06322-6

3. Ran, L, Chen, X, Peng, S, Zheng, F, Tan, X, and Duan, R. Job burnout and turnover intention among Chinese primary healthcare staff: the mediating effect of satisfaction. BMJ Open. (2020) 10:e036702. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2019-036702

4. Xu, X, Huang, J, Zhao, X, Luo, Y, Wang, L, and Ge, Y. Trends in the mobility of primary healthcare human resources in underdeveloped regions of western China from 2000 to 2021: evidence from Nanning. BMC Prim Care. (2024) 25:154. doi: 10.1186/s12875-024-02403-7

5. National Health Commission of China. Guiding opinions on strengthening the construction of the primary healthcare workforce. Beijing: National Health Commission of China (2018).

6. Zheng, J, Xu, A, Cao, X, Zhan, X, Miao, Q, Chen, J, et al. The impact mechanism and path of psychological contract and turnover intention on job performance among primary healthcare workers. Chin Health Serv Manag. (2023) 40:703–9. [in Chinese].

7. Perry, JL, and Wise, LR. The motivational bases of public service. Public Adm Rev. (1990) 50:367–73.

8. Meyer, JP, and Allen, NJ. Three-component conceptualization of organizational commitment. Hum Resour Manag Rev. (1991) 1:61–89.

9. Taing, MU, Granger, BP, Groff, KW, Jackson, EM, and Johnson, RE. The multidimensional nature of continuance commitment: commitment owing to economic exchanges versus lack of employment alternatives. J Bus Psychol. (2011) 26:269–84. doi: 10.1007/s10869-010-9188-z

10. Van den Broeck, A, Howard, JL, Van Vaerenbergh, Y, Leroy, H, and Gagné, M. Beyond intrinsic and extrinsic motivation: a meta-analysis on self-determination theory’s multidimensional conceptualization of work motivation. Organ Psychol Rev. (2021) 11:240–73. doi: 10.1177/20413866211006173

11. Meyer, JP, Stanley, DJ, Herscovitch, L, and Topolnytsky, L. Affective, continuance, and normative commitment to the organization: a meta-analysis of antecedents, correlates, and consequences. J Vocat Behav. (2002) 61:20–52. doi: 10.1006/jvbe.2001.1842

12. Vandenberghe, C, and Panaccio, A. Perceived sacrifice and few alternatives commitments: the motivational underpinnings of continuance commitment. J Vocat Behav. (2012) 81:59–72. doi: 10.1016/j.jvb.2012.05.002

13. Aliddin, LA, Syaifuddin, DT, Montundu, Y, and Marlina, S. The impact of perceived organizational support and social support on employee performance: the mediating role of organizational commitment. J Econ Business, Accountancy Ventura. (2024) 27:253–73. doi: 10.14414/jebav.v27i2.4610

14. Jaros, S, and Culpepper, RA. Some unresolved issues in the person-centered approach to organizational commitment within the Meyer/Allen paradigm. Manag Res Rev. (2025) 48:849–62. doi: 10.1108/MRR-11-2022-0747

15. Allen, NJ, and Meyer, JP. Affective, continuance, and normative commitment to the organization: an examination of construct validity. J Vocat Behav. (1996) 49:252–76.

16. Gellatly, IR, Meyer, JP, and Luchak, AA. Combined effects of the three commitment components on focal and discretionary behaviors: a test of Meyer and Herscovitch’s propositions. J Vocat Behav. (2006) 69:331–45. doi: 10.1016/j.jvb.2005.07.001

17. Chen, KS. A study on organizational commitment, work motivation, and job performance after the COVID-19 epidemic in Taiwan – the mediating effects of work motivation and organizational communication. Manag Stud. (2023) 11:65–74. doi: 10.59654/ms.2023.v11i1.006

18. Arifin, AH, and Matriadi, F. The role of job satisfaction in relationship to organization culture and organization commitment on employee performance. United Int J Res Technol. (2022) 3:117–29. doi: 10.17265/2328-2185/2023.02.002

19. Otoum, R, Hassan, II, Ahmad, WMAW, Al-Hussami, M, and Mohd Nawi, MN. Mediating role of job satisfaction in the relationship between job performance and organizational commitment components: a study among nurses at one public university hospital in Malaysia. Malays J Med Health Sci. (2021) 17:197–204.

20. Deci, EL, and Ryan, RM. The “what” and “why” of goal pursuits: human needs and the self-determination of behavior. Psychol Inq. (2000) 11:227–68. doi: 10.1207/S15327965PLI1104_01

21. Deci, EL, and Ryan, RM. Self-determination theory: Basic psychological needs in motivation, development, and wellness. New York: Guilford Press (2017).

22. Ryan, RM, and Deci, EL. Self-determination theory and the facilitation of intrinsic motivation, social development, and well-being. Am Psychol. (2000) 55:68–78.

23. Gagné, M, and Deci, EL. Self-determination theory and work motivation. J Organ Behav. (2005) 26:331–62. doi: 10.1002/job.322

24. Autin, KL, Herdt, ME, Garcia, RG, and Ezema, GN. Basic psychological need satisfaction, autonomous motivation, and meaningful work: a self-determination theory perspective. J Career Assess. (2022) 30:78–93. doi: 10.1177/10690727211042310

25. Meyer, JP, and Parfyonova, NM. Normative commitment in the workplace: a theoretical analysis and re-conceptualization. Hum Resour Manag Rev. (2010) 20:283–94. doi: 10.1016/j.hrmr.2009.09.001

26. Deci, EL, Olafsen, AH, and Ryan, RM. Self-determination theory in work organizations: the state of a science. Annu Rev Organ Psych Organ Behav. (2017) 4:19–43. doi: 10.1146/annurev-orgpsych-032516-113108

27. Gagné, M, Forest, J, Vansteenkiste, M, Crevier-Braud, L, Van den Broeck, A, Aspeli, AK, et al. The multidimensional work motivation scale: validation evidence in seven languages and nine countries. Eur J Work Organ Psychol. (2015) 24:178–96. doi: 10.1080/1359432X.2013.877892

28. Zhao, S. Research on the relationship between job attitudes and performance of health technicians in township health centers in three provinces of China [dissertation]. Jinan: Shandong University (2015).

29. Zhao, S, Ma, Z, Li, H, Wang, Z, Wang, Y, and Ma, H. The impact of organizational justice on turnover intention among primary healthcare workers: the mediating role of work motivation. Risk Manag Healthc Policy. (2024) 17:3017–28. doi: 10.2147/RMHP.S486535

30. Ryan, RM, and Connell, JP. Perceived locus of causality and internalization: examining reasons for acting in two domains. J Pers Soc Psychol. (1989) 57:749–61.

31. Chen, CA, and Bozeman, B. Understanding public and nonprofit managers' motivation through the lens of self-determination theory. Public Manag Rev. (2013) 15:584–607. doi: 10.1080/14719037.2012.698853

32. Zhao, S, Li, J, Zou, B, Zhang, X, Ma, H, et al. The impact mechanism of performance management on work performance of primary healthcare workers: the mediating role of work motivation. Chin J Health Policy. (2022) 15:24–30. doi: 10.3969/j.issn.1674-2982.2022.05.004, [in Chinese].

33. Baron, RM, and Kenny, DA. The moderator–mediator variable distinction in social psychological research: conceptual, strategic, and statistical considerations. J Pers Soc Psychol. (1986) 51:1173–82.

34. Meyer, JP, and Maltin, ER. Employee commitment and well-being: a critical review, theoretical framework and research agenda. J Vocat Behav. (2010) 77:323–37. doi: 10.1016/j.jvb.2010.04.007

35. Kolakowski, M, Royle, T, and Pittman, J. Reframing employee well-being and organizational commitment. J Organ Psychol. (2020) 20:30–42.

36. Wranik, WD, Price, S, Haydt, SM, Edwards, J, Hatfield, K, and Weir, J. Implications of interprofessional primary care team characteristics for health services and patient health outcomes: a systematic review with narrative synthesis. Health Policy. (2019) 123:550–63. doi: 10.1016/j.healthpol.2019.03.015

37. Eagly, AH, and Wood, W. Social role theory In: PAM Lange, AW Kruglanski, and ET Higgins, editors. Handbook of theories of social psychology. London: SAGE Publications Ltd (2012). 458–76.

38. Aydin, A, Sarier, Y, and Uysal, S. The effect of gender on organizational commitment of teachers: a meta-analytic analysis. Educ Sci Theory Pract. (2011) 11:628–32.

39. Marsden, PV, Kalleberg, AL, and Cook, CR. Gender differences in organizational commitment: influences of work positions and family roles. Work Occup. (1993) 20:368–90. doi: 10.1177/0730888493020003005

40. Willis-Shattuck, M, Bidwell, P, Thomas, S, Wyness, L, Blaauw, D, and Ditlopo, P. Motivation and retention of health workers in developing countries: a systematic review. BMC Health Serv Res. (2008) 8:247. doi: 10.1186/1472-6963-8-247

41. Vandenberghe, C, Mignonac, K, and Manville, C. When normative commitment leads to lower well-being and reduced performance. Hum Relat. (2015) 68:843–70. doi: 10.1177/0018726714547060

42. Li, X, Krumholz, HM, Yip, W, Cheng, KK, De Maeseneer, J, Meng, Q, et al. Quality of primary health care in China: challenges and recommendations. Lancet. (2020) 395:1802–12. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30122-7

Keywords: organizational commitment, job performance, motivation internalization, primary healthcare workers, self-determination theory

Citation: Zhao S, Wang T, Luo S, Mi Y, Wang Y, Ma H and Wei X (2025) The impact of organizational commitment on job performance in primary healthcare: a motivation internalization perspective. Front. Public Health. 13:1685420. doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2025.1685420

Edited by:

Arif Jameel, Shandong Xiehe University, ChinaReviewed by:

Erita Yuliasesti Diah Sari, Ahmad Dahlan University, IndonesiaSofia Sofia, Syiah Kuala University, Indonesia

Copyright © 2025 Zhao, Wang, Luo, Mi, Wang, Ma and Wei. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Ying Wang, eWluZ3dhbmdfMjAxNkAxNjMuY29t; Huifen Ma, aHVpZmVubWFAb3V0bG9vay5jb20=

†These authors have contributed equally to this work and share first authorship

Shichao Zhao

Shichao Zhao Tao Wang2†

Tao Wang2† Ying Wang

Ying Wang Huifen Ma

Huifen Ma Xiaolin Wei

Xiaolin Wei