As of 2022, 23.9% of the Indian population (aged 15 years and above) uses tobacco (10.4% females and 36.8% males) (1). Further, 4.6% of the Indian population (≥15 years of age) smokes cigarettes as per 2022 data (0.4% females and 8.6% males) (1).

As per data from the National Family Health Survey-5 (NFHS-5), 2019–2021, from 47,343 adolescent (15–24 years of age) participants (42,254 females and 5,089 males), 1.3% females and 20.3% males were tobacco users (2). Males were found to be tobacco users more commonly as compared to females in both the young adult and late adolescent age groups: 31.8%, 2.2% and 15.9%, 1.2%, respectively (2).

According to data from 2021, tobacco was implicated in 18% or about 274,000 ischemic heart disease (IHD) mortalities, 60.4% (33,500) of all deaths from lung cancer, 14.2% (95,200) deaths from stroke and 40.7% (362,700) mortalities from Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease (COPD) (1). In 2021, tobacco was responsible for the loss approximately 12.6% of the total Disability Adjusted Life Years (DALYs) which is a loss of around 28.9 million DALYs in itself. Tobacco was responsible for 887,300 lung cancer DALYs, 7.8 million IHD DALYs, 7.9 million COPD DALYs, and 2.6 million stroke DALYs (1).

In apparent public health interest, Electronic Nicotine Delivery Systems (ENDS) are banned in India (1). The rationale behind this policy has been stated to revolve around issues such as nicotine addiction, harmful additives, possible carcinogens, waste disposal, and manufacturing-related environmental hazards (3).

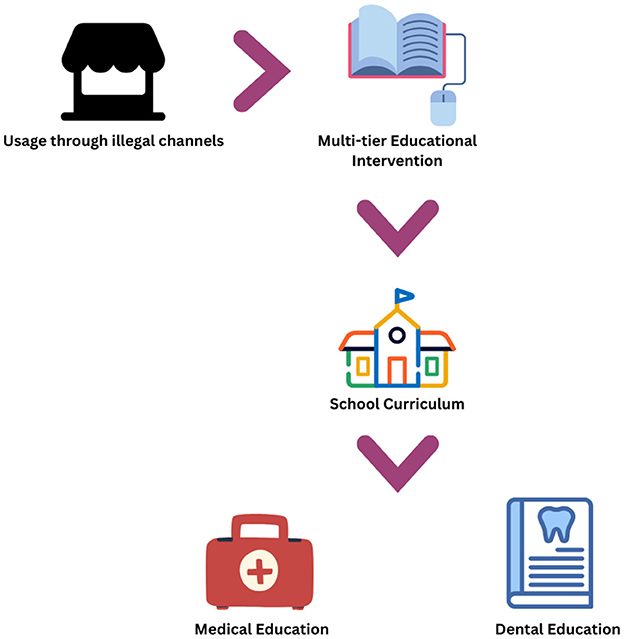

Despite the ban, ENDS continue to be available via illicit sources in India and readily so to be bought and used by consumers with vendors in probably all cases not being bothered to ascertain the age of the individuals buying these products.

Based on some evidence e-cigarettes are used as a smoking cessation intervention considering their safety profile in comparison to conventional cigarettes but the possibility of dual addiction cannot be ignored especially in the context of low-middle-income countries (4).

A growing concern surrounds the usage of these devices by people who were not smoking conventional cigarettes in the first place and indeed by adolescents and young adults who might be at risk of falling into nicotine addiction, which could then serve as a gateway to tobacco consumption and other substance abuse behavior (5).

A rampant unregulated gray/black market can possibly be filled with dubious and dangerous products which can cause significant harm to users such has been reported with the E-cigarette- or Vaping-Use-Associated Lung Injury outbreak in the US as well as incidents of modified devices causing explosive injuries (6, 7). In light of the situation described, it becomes imperative to educate as many people as possible, particularly those in younger age groups who might be more impressionable, regarding these devices and their risk profile (8).

A significant step forward in this regard will be to incorporate vaping prevention information into school curricula. This can be accomplished by adding this section alongside information on tobacco and/or other substance abuse-related topics. Individuals at a young and possibly impressionable age are likely to benefit from scientifically correct information when this is provided in a formal manner from a perceptible reliable source and individual (teacher).

School-based interventions, such as the Vaping: know the Truth curriculum, has been observed to be successful in increasing vaping harm-related knowledge among the youth (9). This intervention was innovative in terms of being peer-to-peer and online while also providing guidance on ways to quit vaping (9).

The CATCH My Breath program was found to be effective, feasible, and well-received when administered to 6,217 pupils over 25 high- and middle-schools across a 4-year time period in eight counties in the Appalachian region of the United States (10).

The OurFutures Vaping Program based out of Australia is another prevention-based initiative targeted toward adolescents (11).

The American Academy of Pediatrics also offers a curriculum aimed toward youth vaping and e-cigarette cessation and prevention (12).

There is however, a lack of such programs reported from the Southeast Asia region. Ideally, the strategy should be region-specific, however, existing programs from other parts of the world can be adapted in part or as a whole to evaluate their effectiveness, as a starting point.

A survey of medical students from Scotland (n = 606 comprising about 12% of all Scottish medical students) found that a vast majority (95%) reported e-cigarettes to not being covered sufficiently in their curriculum while 61% admitted that there was no mention of e-cigarettes in their coursework (13). Most respondents (98%) were not aware of the availability of any cessation services (13).

Previous work has highlighted shortcomings in the knowledge of dental students in the US and Spain to deal with a rise in e-cigarette usage and imparting relevant information to patients in this regard (14). This study recommended educational programs and incorporation of information on the hazards of e-cigarette usage in dental curricula (14).

The ill-effects of tobacco usage are taught in medical and dental schools in India, however, previous research has highlighted the largely didactic nature of instruction and a need to integrate tobacco counseling training not just in India but across curricula the world over (15).

There is room in Indian academic curricula to add information on ENDS in the MBBS (Bachelor of Medicine, Bachelor of Surgery), BDS (Bachelor of Dental Surgery), B.Sc. Nursing and B.Pharm courses (16–19). Healthcare professionals will probably be the first contacts of many ENDS-using individuals reporting to clinics and should be trained in identifying such individuals and counseling them appropriately. Not only this, healthcare professionals may largely be perceived as reliable sources of information and it is only when these individuals themselves have appropriate information on ENDS can they provide accurate information further.

The vaping prevention curricula at the school-level can be focused on equipping students with knowledge regarding the harmful effects of using these devices and help device refusal strategies. At the university-level, ENDS education can delve into greater scientific detail regarding the risk profile of vaping along with integrating cessation counseling skills. The delivery methods for a vaping prevention curriculum can be both online and in-person, with ENDS education at the university-level including a practical component to integrate cessation counseling skills.

Figure 1 illustrates a workflow of the situation and suggestions described.

Author contributions

VS: Software, Formal analysis, Writing – original draft, Resources, Visualization, Conceptualization, Writing – review & editing, Methodology, Investigation, Validation, Data curation. AS: Project administration, Writing – review & editing, Writing – original draft, Supervision, Conceptualization, Validation.

Funding

The author(s) declare that no financial support was received for the research and/or publication of this article.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The author(s) declare that no Gen AI was used in the creation of this manuscript.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Publisher's note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

1. Global Action to End Smoking. State of Smoking and Health in India. Available online at: https://globalactiontoendsmoking.org/research/tobacco-around-the-world/india/ (Accessed October 3, 2025).

2. Mudgal SK, Patidar V, Sharma SK, Gaur R, Huda RK, Singh J, et al. Tobacco and alcohol use among adolescents and young adults in aspirational districts in India: NFHS-5 based secondary analysis. Pan Afr Med J. (2025) 51:17. doi: 10.11604/pamj.2025.51.17.46828

3. Chakma JK, Kumar H, Bhargava S, Khanna T. The e-cigarettes ban in India: an important public health decision. Lancet Public Health. (2020) 5:e426. doi: 10.1016/S2468-2667(20)30063-3

4. ASH. Electronic Cigarettes. Available online at: https://ash.org.uk/resources/view/electronic-cigarettes (Accessed July 6, 2025).

5. Ren M, Lotfipour S. Nicotine gateway effects on adolescent substance use. West J Emerg Med. (2019) 20:696–709. doi: 10.5811/westjem.2019.7.41661

6. Centers for Disease Control. Outbreak of Lung Injury Associated with Use of E-Cigarette, or Vaping, Products. Available online at: https://archive.cdc.gov/www_cdc_gov/tobacco/basic_information/e-cigarettes/severe-lung-disease.html (Accessed July 6, 2025).

7. Kaltenborn A, Dastagir K, Bingoel AS, Vogt PM, Krezdorn N. E-cigarette explosions: patient profiles, injury patterns, clinical management, and outcome. JPRAS Open. (2023) 37:34–41. doi: 10.1016/j.jpra.2023.05.001

8. Liu J, Gaiha SM, Halpern-Felsher B. School-based programs to prevent adolescent e-cigarette use: a report card. Curr Probl Pediatr Adolesc Health Care. (2022) 52:101204. doi: 10.1016/j.cppeds.2022.101204

9. Hair EC, Tulsiani S, Aseltine M, Do EK, Lien R, Zapp D, et al. Vaping—know the truth: evaluation of an online vaping prevention curriculum. Health Promot Pract. (2024) 25:468–74. doi: 10.1177/15248399231191099

10. Burchfield K, Doyle D, Mantey D, Bennett T, Baus A. The CATCH My Breath vaping prevention curriculum: an evaluation of impacts in central Appalachian middle and high Schools, 2019-2023. J Prim Care Community Health. (2024) 15:21501319241277393. doi: 10.1177/21501319241277393

11. Gardner LA, Rowe AL, Stockings E, Egan L, Hawkins A, Blackburn K, et al. Co-design of the ‘Our Futures Vaping' programme: a school-based eHealth intervention to prevent e-cigarette use. Health Promot Int. (2025) 40:daaf085. doi: 10.1093/heapro/daaf085

12. American Academy of Pediatrics. E-cigarette Curriculum. Available online at: https://www.aap.org/en/pedialink/e-cigarette-curriculum/?srsltid=AfmBOoo5JSirjzUP4ZjnhSGhzhCE2tHaCblEdeNqFw1LdgnQQmbo3jF6 (Accessed October 3, 2025).

13. Langley RJ, Hamilton H, Turner S, Watt E, Posner F, Macleod KA. E-cigarette education and training in medical schools: a national survey. Pediatr Pulmonol. (2025) 60:e71125. doi: 10.1002/ppul.71125

14. Martín Carreras-Presas C, Naeim M, Hsiou D, Somacarrera Pérez ML, Messadi DV. The need to educate future dental professionals on E-cigarette effects. Eur J Dental Educ. (2018) 22:e751–8. doi: 10.1111/eje.12390

15. Chandrashekar BR, Khanum N, Kulkarni P, Basavegowda M, Kishor M, Suma S. E-learning module on tobacco counselling for students of medicine and dentistry in India: a needs analysis using mixed-methods research. BMJ Public Health. (2024) 2:e001031. doi: 10.1136/bmjph-2024-001031

16. National Medical Commission. UG Curriculum. Available online at: https://www.nmc.org.in/information-desk/for-colleges/ug-curriculum/ (Accessed July 6, 2025).

17. Dental Council of India. BDS Course Regulations 2007. Available online at: https://dciindia.gov.in/Rule_Regulation/Revised_BDS_Course_Regulation_2007.pdf (Accessed July 6, 2025).

18. Indian Nursing Council. Mandatory Modules B.Sc. Nursing Program. Available online at: https://www.indiannursingcouncil.org/uploads/pdf/17409911035979.pdf (Accessed October 3, 2025).

19. Pharmacy Council of India. Rules & Syllabus for the Bachelor of Pharmacy (B. Pharm) Course. Available online at: https://www.pci.nic.in/pdf/Syllabus_B_Pharm.pdf (Accessed October 3, 2025).

Keywords: vaping, Electronic Nicotine Delivery Systems (ENDS), curriculum, prevention, India, education

Citation: Sahni V and Shankar A (2025) Vaping prevention curriculum in India. Front. Public Health 13:1686030. doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2025.1686030

Received: 14 August 2025; Accepted: 07 October 2025;

Published: 28 October 2025.

Edited by:

Ahmed Ibrahim Fathelrahman, Taif University, Saudi ArabiaReviewed by:

Hasanain A. J. Gharban, Wasit University, IraqCopyright © 2025 Sahni and Shankar. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Abhishek Shankar, ZG9jLmFiaGlzaGFua2FyQGdtYWlsLmNvbQ==

Vaibhav Sahni

Vaibhav Sahni Abhishek Shankar

Abhishek Shankar