- 1Department of Emergency Medicine, West China Hospital, Sichuan University, Chengdu, China

- 2West China School of Nursing, Sichuan University, Chengdu, China

- 3Disaster Medical Center, Sichuan University, Chengdu, China

- 4Nursing Key Laboratory of Sichuan Province, Chengdu, China

Background: Emergency nurses face high occupational stress and long working hours, which may contribute to sleep disorders. However, the extent and nature of this association remain unclear.

Objective: This study assessed the relationship between occupational stress and sleep disorders among emergency nurses and identified their contributing factors.

Study design: A stratified cluster sampling method was employed between 26 December 2023 and 18 January 2024, based on the seven geographical regions of China (Northeast, North, East, Central, South, Southwest, and Northwest China). Emergency nurses aged ≥18 years, with ≥1 year of emergency care experience, and no psychiatric disorder history were included. Nurses undergoing advanced training or those on sick leave, maternity leave, or breastfeeding leave for ≥1 month were excluded. Participants completed a structured questionnaire including demographic data, an occupational stress assessment using a five-point Likert scale from 1 to 5, and sleep disorder quality evaluation. Logistic regression analysis was conducted to identify factors associated with sleep disorders, whereas Spearman’s correlation analysis evaluated the relationship between occupational stress and sleep disorders.

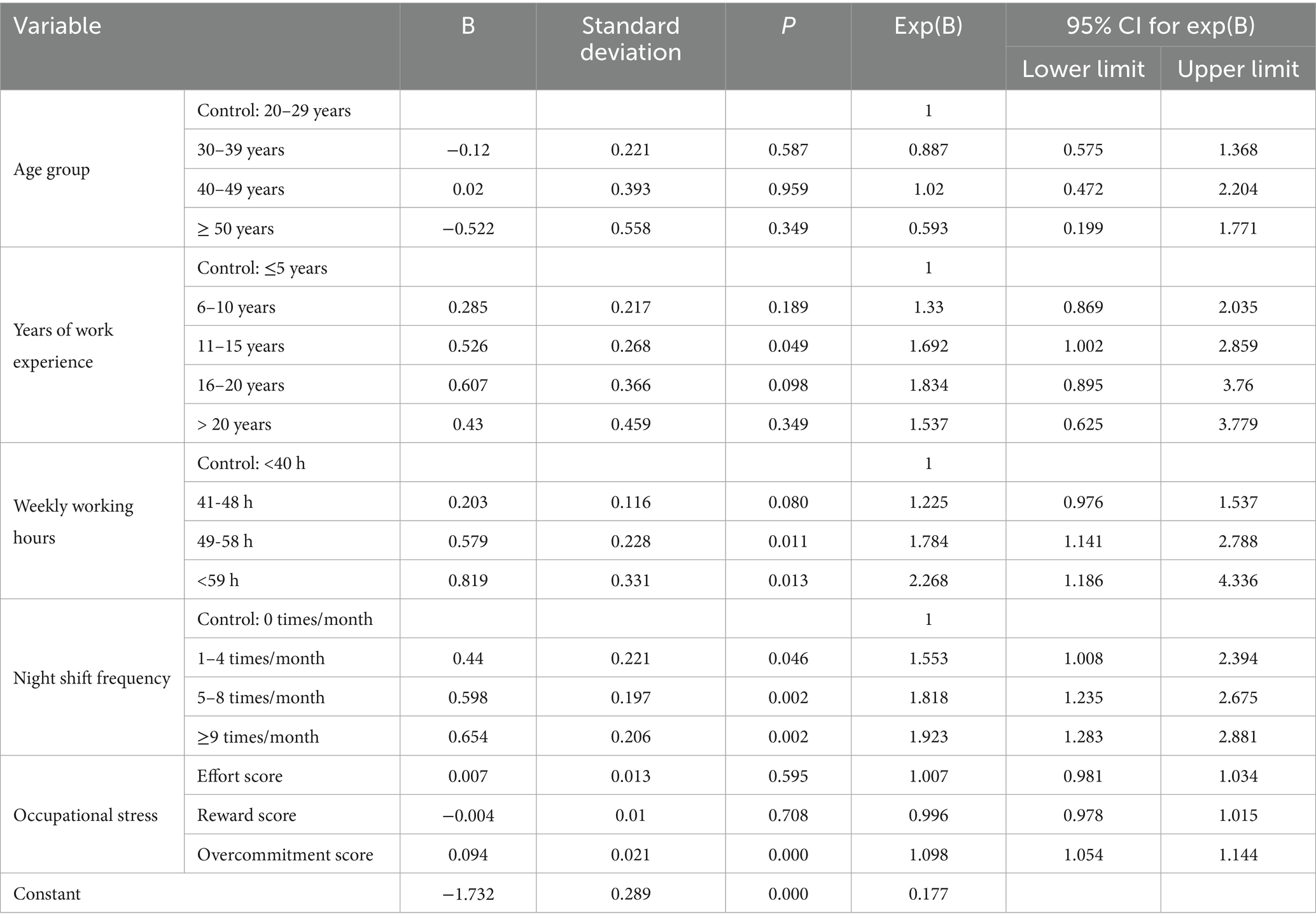

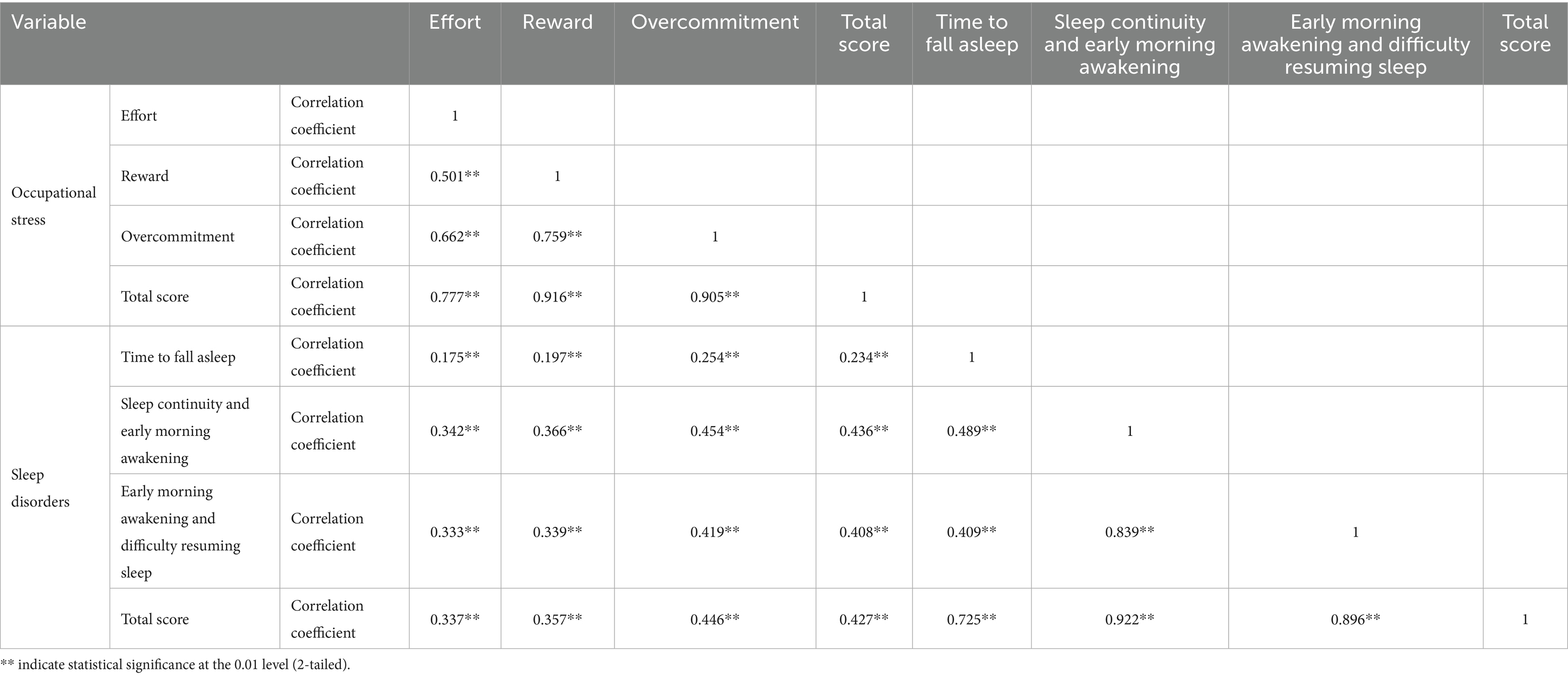

Results: A total of 1,551 questionnaires were collected. After excluding 11 invalid responses, 1,540 were analyzed. Binary logistic regression identified key risk factors for sleep disorders, including 11–15 years of work experience (OR = 1.692), weekly working hours of 49–58 h (OR = 1.784) or ≥59 h (OR = 2.268), night shift frequency, and overcommitment scores (OR = 1.098). A significant positive correlation was found between occupational stress and sleep disturbances (p < 0.05).

Conclusion: These findings highlight the need for hospital administrators to implement targeted interventions, such as psychological support programs, shift rotation optimization, and stress management training. Future research should focus on longitudinal designs to establish causal pathways and evaluate the effectiveness of interventions aimed at improving sleep quality among emergency nurses.

1 Introduction

Sleep disorders encompass a range of functional impairments in the sleep–wake cycle, typically characterized by prolonged sleep latency, difficulties in maintaining sleep, and early morning awakenings. Daytime manifestations commonly include fatigue, lack of concentration, impaired cognitive function, irritability, anxiety, and low mood. A cross-sectional study conducted in the United States revealed that 77.4% of nurses experienced suboptimal sleep quality, with 7.4% suffering from severe insomnia (1). Similarly, in Chinese public hospitals, the prevalence of poor sleep quality and severe sleep problems among emergency nurses was reported to be 65.8 and 61.4%, respectively (2). Inadequate sleep can result in concentration deficits, memory decline, increased absenteeism, higher risk of injuries, and diminished job performance. Furthermore, poor sleep quality is associated with adverse health outcomes, including elevated risks of dementia, cardiovascular diseases, and all-cause mortality. Notably, nurses with sleep difficulties are 15 times more likely to screen positive for depression risk (3).

Occupational stress, often termed “job stress” or “work pressure,” refers to the process wherein workplace stressors elicit psychological, behavioral, or physiological stress responses that may lead to long-term health consequences. This phenomenon affects various sectors involving both physical and mental labor. A UK-based study identified nursing as one of the three most stressful occupational groups (4). In recent years, occupational stress has gained increasing scholarly attention. Epidemiological data indicate that the prevalence of occupational stress among nurses is 38.8% in Europe, 49.0% in North America, 42.7% in South America, and as high as 57.4% in Asia. In China, over two-thirds (68.7%) of emergency nurses report experiencing occupational stress (5). Contributing factors to occupational stress can provoke a spectrum of stress-related responses, including depression, anxiety, and insomnia.

A substantial body of research has documented associations between occupational stress and various physical and mental health conditions, reduced work performance, absenteeism, high staff turnover, and decreased job satisfaction (6–8). A study focusing on police officers highlighted a bidirectional relationship between sleep and stress, demonstrating that chronic occupational stress exposure significantly increases the likelihood of sleep disturbances (9). Correspondingly, a cross-sectional investigation into psychosocial work stress and health risks found that emergency department nurses experiencing occupational stress and overcommitment faced elevated risks of developing stress-related diseases later in life (10). As a high-risk population for occupational stress, nurses frequently encounter persistent sleep problems that not only compromise their physical and mental well-being but also jeopardize medical safety, thereby posing substantial threats to patient care quality. Nevertheless, the specific correlation between occupational stress and sleep disturbances among emergency nurses remains inadequately elucidated, warranting further investigation.

Therefore, this study aimed to assess the relationship between occupational stress and sleep disorders among emergency nurses and to identify contributing factors. We hypothesized that higher occupational stress, longer working hours, and frequent night shifts would be significantly associated with poorer sleep quality.

2 Materials and methods

2.1 Study participants

From December 2023 to January 2024, a stratified cluster sampling method was employed based on geographical regions of China. Inclusion Criteria were as follows: (1) Emergency nurses aged ≥18 years, (2) Possessing at least one year of experience in emergency care, (3) No prior history of diagnosed psychiatric disorders. Exclusion Criteria was nurses on sick leave, maternity leave, or breastfeeding leave for one month or more. The sample size was determined using the formula for cross-sectional studies, the prevalence of sleep disorders among nurses in the previous studies were estimated at 59.9–77.4%, with a margin of error of 5% and a confidence level of 95%, the calculated sample size ranged from 269 to 370, with the maximum sample size of 370 selected.

2.2 Research instruments

General Demographic Information Collection Form: This form collected details such as gender, age, educational background, years of work experience, night shift status, income level, and marital status.

2.2.1 Occupational stress questionnaire

The effort-reward imbalance questionnaire, developed by the German scholar Siegrist and adapted into Chinese version by scholar Dai (11), was used to assess occupational stress levels among emergency nurses. This questionnaire comprises 6 items on effort, 11 items on reward, and 5 items on overcommitment, with each item rated on a five-point Likert scale from 1 to 5. Higher scores indicate greater levels of occupational stress. In this study, the Cronbach’s α coefficient for this scalescale was 0.88, three dimensions are 0.894, 0.952, and 0.922, respectively.

2.2.2 Sleep disorder survey

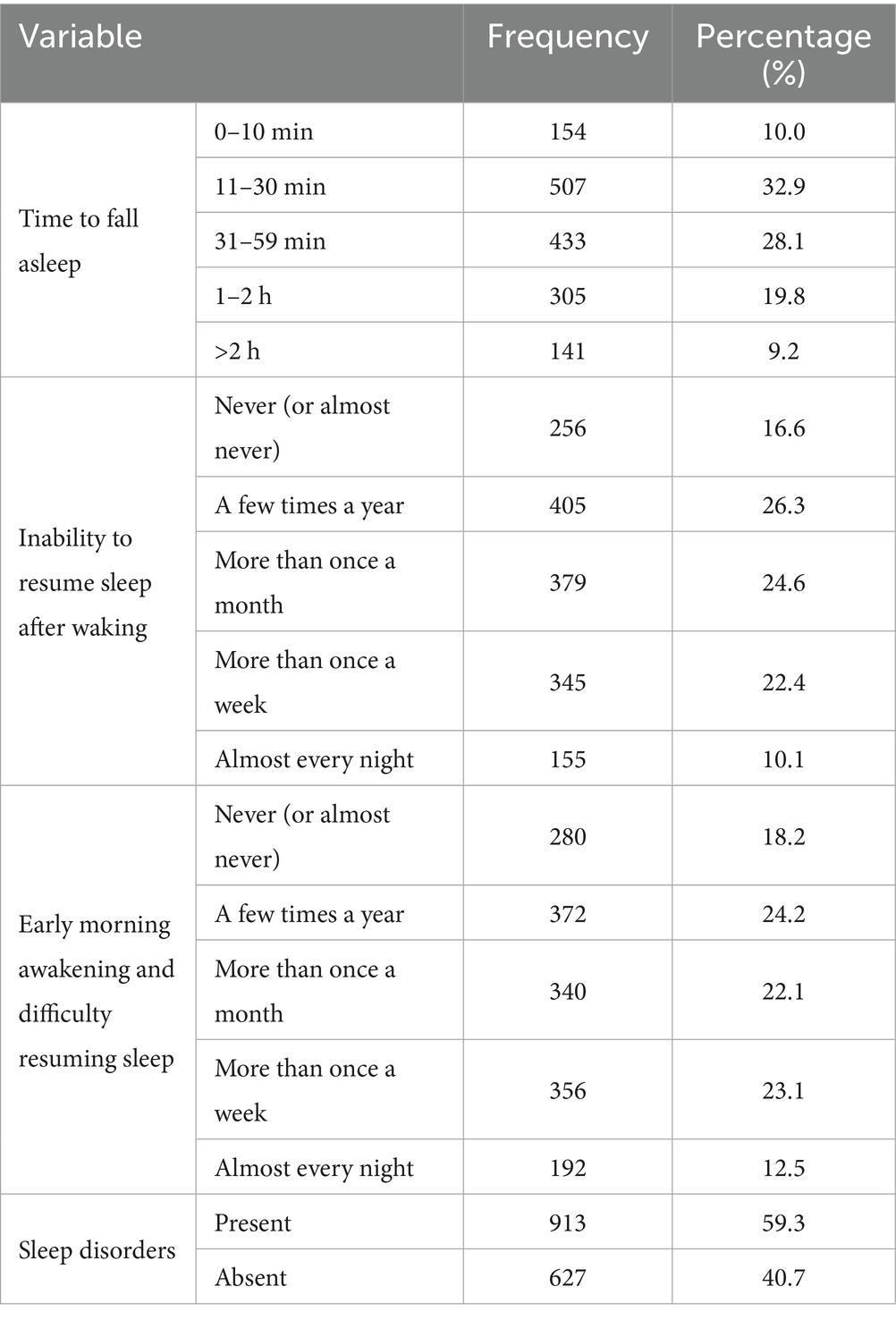

The self-administered sleep questionnaire (SSQ) (12) was used to evaluate sleep disorders among emergency department nurses. This questionnaire assesses 3 sleep symptoms, time to fall asleep, sleep continuity, and early morning awakening, through 3 items. Sleep disorder was defined as meeting at least one of the following: (1) taking ≥30 min to fall asleep; (2) unable to resume sleep after waking more than once a week; (3) early morning awakening with difficulty resuming sleep more than once a week. This composite definition was used to classify participants in Table 1. In this study, the Cronbach’s α coefficient for this scale was 0.809, showing good reliability and validity. Participants were instructed to report their overall sleep quality over the past month, considering both workdays and days off, to minimize bias from transient shift schedules.

2.3 Data collection

An electronic version of the survey questionnaire was created using the Wenjuanxing platform. To ensure data authenticity and consistency across multiple centers, the following measures were implemented: (1) All questionnaire items were set as mandatory to avoid missing data; (2) Each IP address was restricted to one response to prevent multiple submissions by the same individual; (3) Coordinators from each center received unified training to standardize survey administration. Key concepts and instructions related to the survey were standardised through training to ensure that the designated hospital personnel responsible for administering the survey provided accurate and consistent explanations of its content. The QR code for the survey was distributed via the WeChat platform. Participants were required to read and sign the informed consent form before completing the questionnaire. The questionnaires were eliminated, such as identical responses.

2.4 Statistical analysis methods

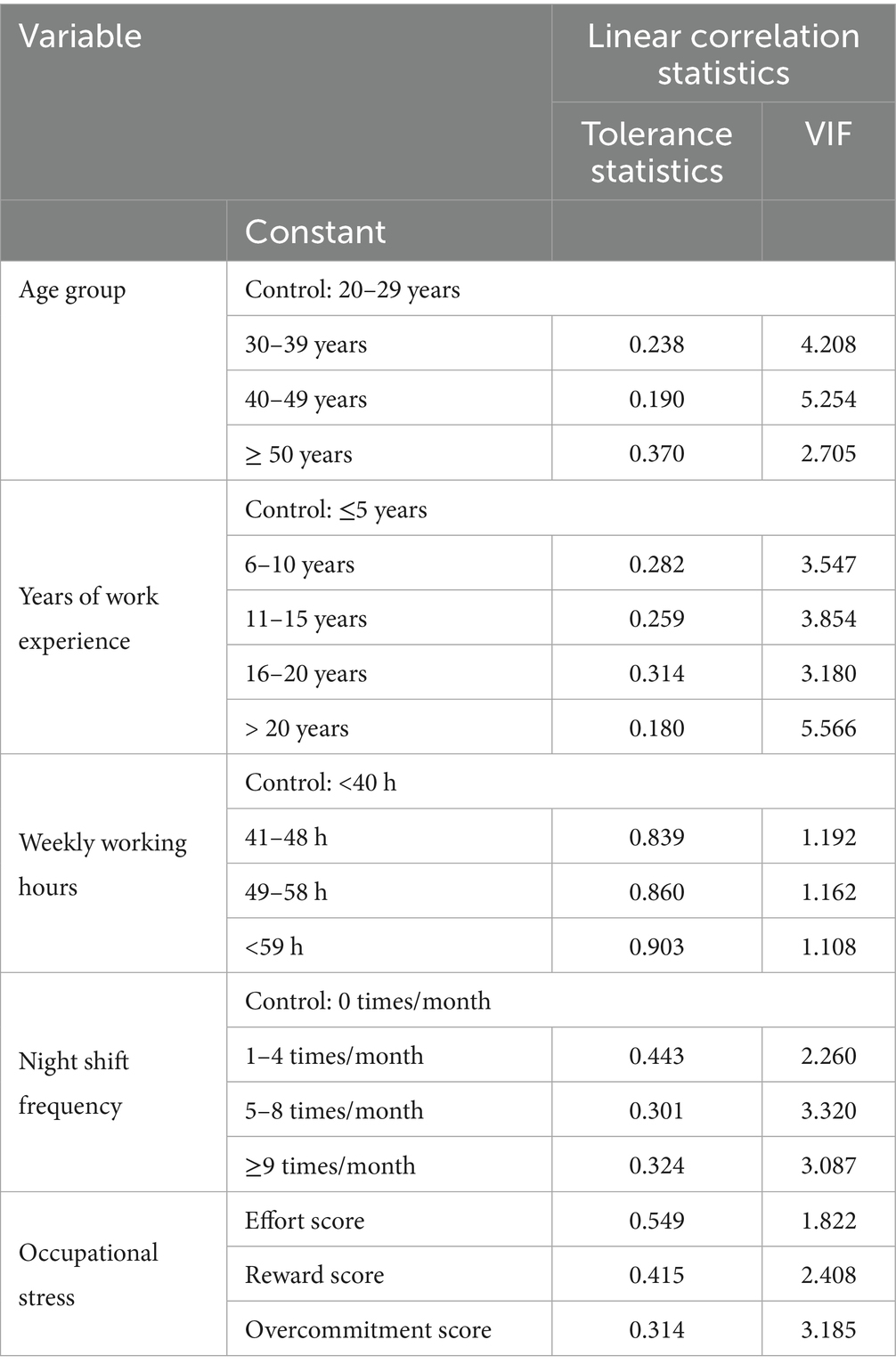

Statistical analyses were conducted using SPSS version 26.0. Descriptive statistics were performed for demographic data. Categorical variables were expressed as frequencies (n) and percentages, while continuous variables were presented as means and standard deviations. The Mann–Whitney U test was used for continuous variables, and the Chi-square test was used for categorical variables in univariate analysis. For variables with more than two categories in univariate analysis, the Chi-square test was applied with the binary sleep disorder outcome. Binary logistic regression analysis was employed to explore factors influencing sleep disorders, and Spearman’s rank correlation analysis was used to examine the relationship between occupational stress and sleep disorders. Potential confounding variables (e.g., age, gender, years of experience, night shift) were included in the binary logistic regression model to control for their effects. Multicollinearity was assessed using Variance Inflation Factor (VIF), with all values below 10 indicating no significant multicollinearity.

2.5 Ethics approval statement

This study was approved by the Ethics Review Committee of West China Hospital, Sichuan University (approval no. 2024.309). Written informed consent was obtained from all participants prior to data collection.

3 Results

3.1 Descriptive analysis of general demographic information of study participants

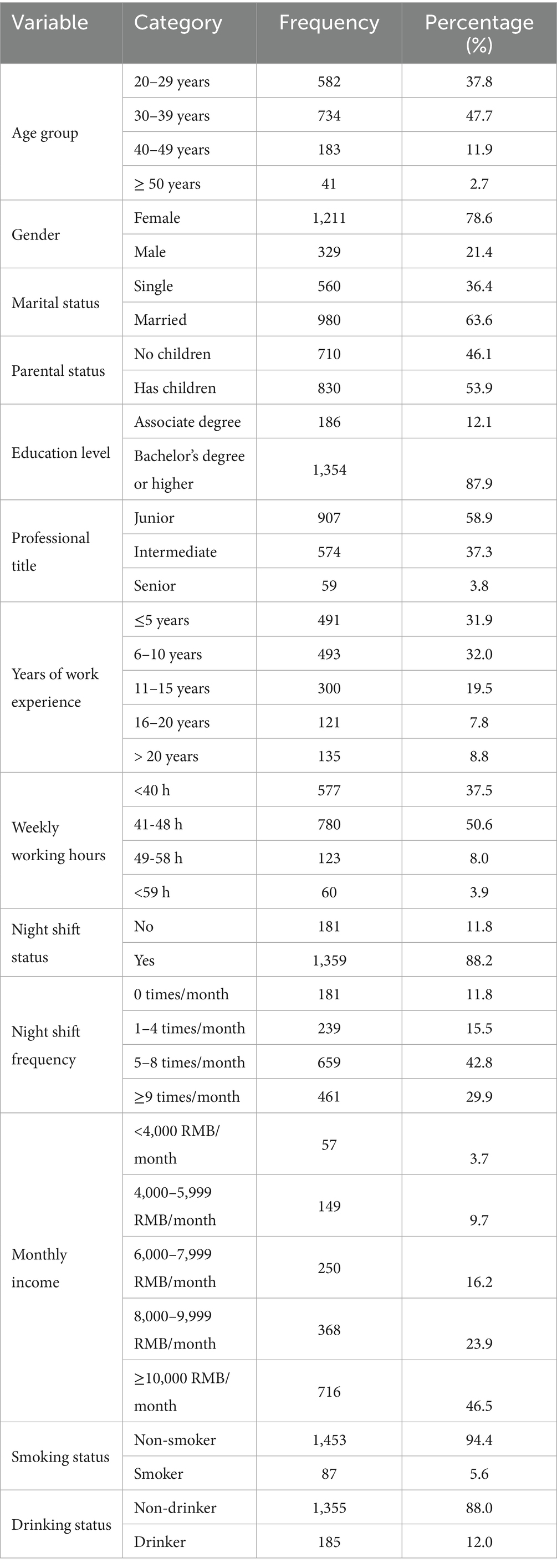

During the study period, a total of 1,551 questionnaires were collected. After excluding 11 questionnaires with identical responses, 1,540 were included in the final analysis. The participants were recruited from seven geographical regions of China. The regional distribution was as follows: North China (9%), Northeast China (15.3%), East China (21.6%), Central China (9%), South China (8.2%), Southwest China (16.9%), and Northwest China (19.7%). The basic characteristics of the participants were as follows: 1,211 were female, accounting for 78.6%; 1,354 had an education level of a bachelor’s degree or higher, representing 87.9%; 960 worked more than 40 h per week, accounting for 62.5%; and 1,359 had night shifts, representing 88.2%. See Table 2 for details.

3.2 Descriptive analysis of survey results on occupational stress and sleep quality

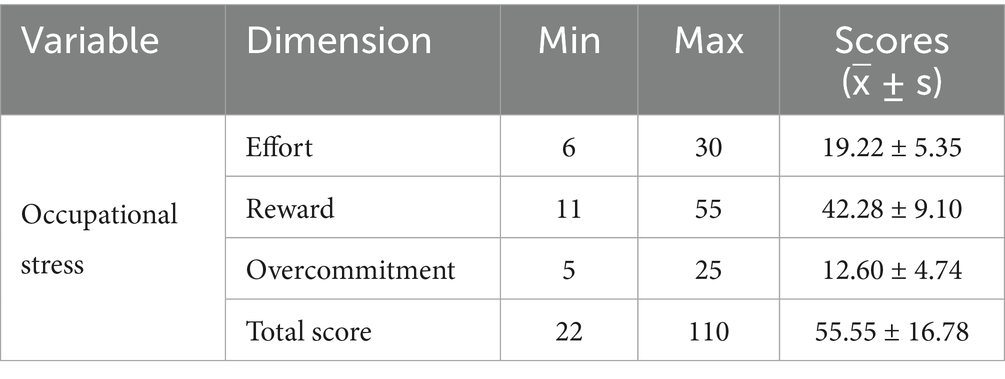

Regarding occupational stress, the total score was 55.55 ± 16.78, with an effort score of 19.22 ± 5.35, a reward score of 23.7 ± 9.10, and an overcommitment score of 12.60 ± 4.74. In terms of sleep quality, 59.3% of nurses experienced sleep disorders. Among them, 57.1% of nurses took 30 min or more to fall asleep, and 16.6% of nurses reported never being able to fall back asleep after waking up during the night. For detailed information, please refer to Tables 1, 3.

3.3 Analysis of factors influencing sleep disorders

To examine the factors associated with sleep disorders, sleep disorders were used as the dependent variable, while general demographic characteristics and occupational stress were used as independent variables.

3.3.1 Univariate screening

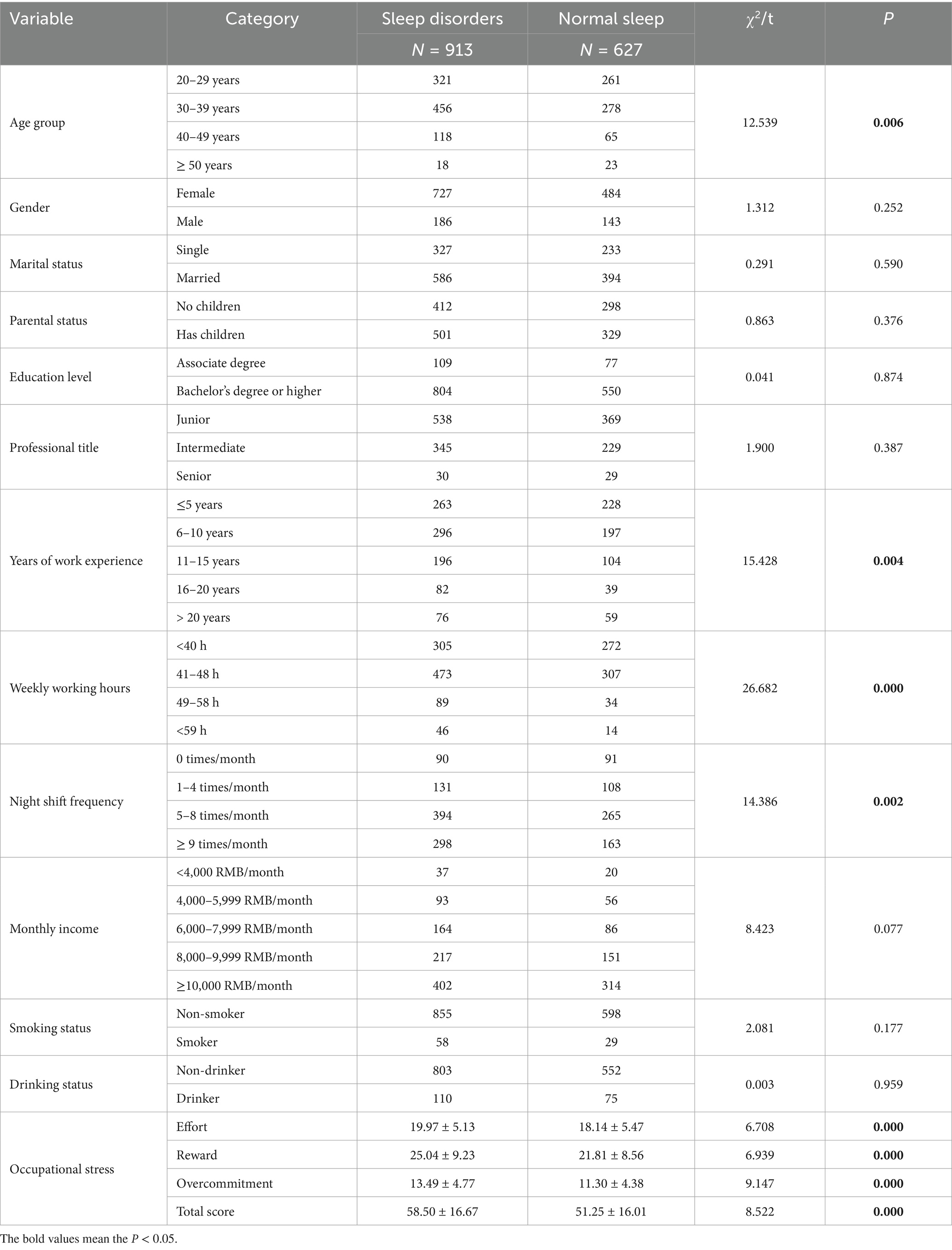

The univariate analysis revealed that years of work experience, weekly working hours, night shifts, and occupational stress were significantly associated with sleep disorders among emergency nurses (p < 0.05). See Table 4 for details.

3.3.2 Results of multivariate analysis

The results of the binary logistic regression analysis indicated that years of work experience (11–15 years), weekly working hours (49–58 h and ≥59 h), night shift frequency, and overcommitment scores were significant predictors of sleep disorders among emergency nurses. Specifically, emergency nurses with 11–15 years of work experience had a 1.692 times higher likelihood of developing sleep disorders compared to those with less than 5 years of work experience. Additionally, for each one-unit increase in the overcommitment score, the risk of sleep disorders increased by 1.098 times. See Table 5 for details.

3.3.3 Results on the correlation between occupational stress and sleep disorders

A positive correlation was observed between occupational stress and sleep disorders among emergency nurses (p < 0.05). See Table 6 for details.

3.4 Collinearity diagnosis

The collinearity diagnosis showed that all tolerance statistics were greater than 0.1 and all Variance Inflation Factor (VIF) values were less than 10, indicating no evidence of multicollinearity among the independent variables (Table 7).

4 Discussion

Emergency nurses serve as a vital force within the healthcare system, bearing the responsibility of treating critically ill patients. The nature of their work often entails 24-h availability, and the high-intensity, high-pressure environment presents significant challenges to their physical and mental well-being, among which sleep disorders are particularly prominent. This survey found that 59.3% of emergency nurses experienced sleep disorders, a finding consistent with the cohort study by Zhang et al. (13), which reported a prevalence of 59.9% among nurses. Adequate sleep is a physiological necessity, comparable to the need for food, and is crucial for sustaining life, health, and workplace safety (14–16). Good sleep quality is essential for nurses to deliver optimal patient care. Previous studies have similarly indicated a high prevalence of sleep disorders among nurses, with reported rates of 77.4% in the United States (1), 63.9% in China (17), and 57% in Taiwan (18), and a pooled prevalence of 61.0% according to Zeng et al. (19). These data suggest that sleep disorders are a common issue among nursing populations globally.

The results of the binary logistic regression analysis identified years of work experience (11–15 years), weekly working hours (49–58 h and ≥59 h), night shift frequency, and overcommitment scores as significant factors associated with the occurrence of sleep disorders among emergency nurses. Specifically, nurses with 11–15 years of experience had 1.692 times higher odds of sleep disorders compared to those with less than 5 years of experience. Moreover, for each one-unit increase in the overcommitment score, the risk of sleep disorders increased by 1.098 times. Due to prolonged exposure to high-pressure emergency settings, they may face dual pressures from career advancement and familial responsibilities, potentially leading to the accumulation of chronic stress, which could adversely affect sleep quality.

Furthermore, long-term shift work has been linked to reduced sensitivity of melatonin receptors, which may exacerbate sleep problems of emergency nurses. Extended weekly working hours (49–58 h or ≥59 h) were associated with more severe sleep disturbances. Such prolonged work hours may lead to persistent activation of the sympathetic nervous system, potentially impairing cellular repair processes and sleep efficiency. Frequent night shifts disrupt the body’s natural circadian rhythm, leading to dysregulation of the biological clock, which in turn may negatively impact sleep quality. Over time, such persistent disruptions are likely to contribute to ongoing sleep disturbances, with further implications for physical and mental health of emergency nurses.

This study also demonstrated a significant positive correlation between occupational stress and sleep disorders among emergency nurses (*p < 0.05). As crucial members of the healthcare system, emergency nurses operate under high-intensity pressure and complex working conditions. They are required not only to manage critically ill patients but also to respond to various emergencies and unpredictable situations. Within this demanding context, occupational stress among emergency nurses has become increasingly evident, with components such as effort, reward, and overcommitment significantly associated with their well-being. Emergency nurses often invest considerable effort into their work without receiving commensurate rewards. This effort-reward imbalance may contribute to feelings of frustration and dissatisfaction, which could further increase the risk of sleep disorders. Additionally, the high levels of concentration and dedication required in their roles often necessitate substantial overcommitment. While this may improve work efficiency and quality, it may also result in physical and mental exhaustion. Prolonged exposure to such demanding conditions appears to heighten the likelihood of developing sleep disturbances and other stress-related health issues. These findings suggest the need for targeted interventions to reduce occupational stress and improve sleep among emergency nurses, such as, optimizing shift schedules to limit consecutive nights; providing stress management and mindfulness training.

5 Limitations

It is important to note that this study demonstrates a correlation between occupational stress and sleep disorders, not causation. The cross-sectional design limits causal inference. The study participants were primarily emergency department nurses, making it necessary to further assess the generalizability of the findings to other hospital settings and clinical departments. Future research should consider conducting large-sample longitudinal cohort studies to elucidate the causal relationship between occupational stress and sleep disorders.

6 Conclusion

Years of work experience, weekly working hours, night shifts, and occupational stress are significant risk factors contributing to sleep disorders among emergency nurses. This study highlights a correlation between occupational stress and sleep disturbances in this population, with findings suggesting that greater occupational stress is associated with increased severity of sleep disorders.

Data availability statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

Ethics statement

The study was approved by Ethics Review Committee of West China Hospital, Sichuan University. The study was conducted in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. Informed consents were obtained from all participation.

Author contributions

YG: Writing – original draft, Data curation. XM: Data curation, Writing – original draft. YW: Formal analysis, Writing – original draft, Data curation. HZ: Writing – original draft, Data curation, Methodology, Formal analysis. LZ: Writing – original draft, Formal analysis, Data curation. ZY: Methodology, Writing – review & editing. XC: Writing – review & editing, Methodology.

Funding

The author(s) declare that no financial support was received for the research and/or publication of this article.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank all the participants of this project.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The author(s) declare that no Gen AI was used in the creation of this manuscript.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

1. Khatony, A, Zakiei, A, Khazaie, H, Rezaei, M, and Janatolmakan, M. International nursing: a study of sleep quality among nurses and its correlation with cognitive factors. Nurs Adm Q. (2020) 44:E1–E10. doi: 10.1097/NAQ.0000000000000397

2. Dong, H, Zhang, Q, Zhu, C, and Lv, Q. Sleep quality of nurses in the emergency department of public hospitals in China and its influencing factors: a cross-sectional study. Health Qual Life Outcomes. (2020) 18:116. doi: 10.1186/s12955-020-01374-4

3. Norful, AA, Albloushi, M, Zhao, J, Gao, Y, Castro, J, Palaganas, E, et al. Modifiable work stress factors and psychological health risk among nurses working within 13 countries. J Nurs Scholarsh. (2024) 56:742–51. doi: 10.1111/jnu.12994

4. Fagin, L, Brown, D, Bartlett, H, Leary, J, and Carson, J. The Claybury community psychiatric nurse stress study: is it more stressful to work in hospital or the community? J Adv Nurs. (1995) 22:347–58. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2648.1995.22020347.x

5. Zhang, Y, Lei, S, and Yang, F. Incidence of effort-reward imbalance among nurses: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Front Psychol. (2024) 15:1425445. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2024.1425445

6. Tan, Y, Zhou, J, Zhang, H, Lan, L, Chen, X, Yu, X, et al. Effects of effort-reward imbalance on emergency nurses' health: a mediating and moderating role of emotional exhaustion and work-family conflict. Front Public Health. (2025) 13:1580501. doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2025.1580501

7. Zhong, L, Wang, L, Zhang, H, Diao, D, Chen, X, and Zou, L. Effort-reward imbalance among emergency department nurses in China: construction and evaluation of a nomogram predictive model. J Nurs Manag. (2025) 2025:1412700. doi: 10.1155/jonm/1412700

8. Fei, Y, Fu, W, Zhang, Z, Jiang, N, and Yin, X. The effects of effort-reward imbalance on emergency nurses' turnover intention: the mediating role of depressive symptoms. J Clin Nurs. (2023) 32:4762–70. doi: 10.1111/jocn.16518

9. Garbarino, S, and Magnavita, N. Sleep problems are a strong predictor of stress-related metabolic changes in police officers: a prospective study. PLoS One. (2019) 14:e0224259. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0224259

10. Bardhan, R, Heaton, K, Davis, M, Chen, P, Dickinson, DA, and Lungu, CT. A cross-sectional study evaluating psychosocial job stress and health risk in emergency department nurses. Int J Environ Res Public Health. (2019) 16:3243. doi: 10.3390/ijerph16183243

11. Dai, JM. Job stress assessment method and its health effect at early stage. Shanghai: Fudan University Press (2008).

12. Nakata, A, Haratani, T, Takahashi, M, Kawakami, N, Arito, H, Kobayashi, F, et al. Job stress, social support, and prevalence of insomnia in a population of Japanese daytime workers. Soc Sci Med. (2004) 59:1719–30. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2004.02.002

13. Zhang, X, and Zhang, L. Risk prediction of sleep disturbance in clinical nurses: a nomogram and artificial neural network model. BMC Nurs. (2023) 22:289. doi: 10.1186/s12912-023-01462-y

14. Everson, CA. Comparative research approaches to discovering the biomedical implications of sleep loss and sleep recovery In: CJ Amlaner and PM Fuller, editors. Basics of sleep guide. 2nd ed. Westchester, IL: Sleep Research Society (2009). 237–48.

15. Zhang, H, Zhou, J, Zhong, L, Zhu, L, and Chen, X. Relationship between workplace violence and occupational health in emergency nurses: the mediating role of dyssomnia. Nurs Crit Care. (2025) 30:e70008. doi: 10.1111/nicc.70008

16. Centers for Disease Control. Effect of short sleep duration on daily activities – United States, 2005-2008. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. (2011) 60:239–42.

17. Dong, H, Zhang, Q, Sun, Z, Sang, F, and Xu, Y. Sleep disturbances among Chinese clinical nurses in general hospitals and its influencing factors. BMC Psychiatry. (2017) 17:241. doi: 10.1186/s12888-017-1402-3

18. Shao, MF, Chou, YC, Yeh, MY, and Tzeng, WC. Sleep quality and quality of life in female shift-working nurses. J Adv Nurs. (2010) 66:1565–72. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2648.2010.05300.x

Keywords: emergency nurses, occupational stress, sleep disorders, night shifts, workload, effort-reward imbalance, overcommitment

Citation: Gao Y, Ma X, Wang Y, Zhang H, Zhong L, Yuan Z and Chen X (2025) Relationship between occupational stress and sleep quality among emergency nurses. Front. Public Health. 13:1699441. doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2025.1699441

Edited by:

Concetto Mario Giorgianni, University of Messina, ItalyReviewed by:

Aleksandar Racz, University of Applied Health Sciences, CroatiaTianyu Chu, Affiliated Hospital of Jiangnan University, China

Copyright © 2025 Gao, Ma, Wang, Zhang, Zhong, Yuan and Chen. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Zhenfei Yuan, eXVhbnpoZW5mZWkxOTgyQDE2My5jb20=; Xiaoli Chen, NTMxMDkzOTUyQHFxLmNvbQ==

†These authors have contributed equally to this work

Yizhu Gao1,2,3,4†

Yizhu Gao1,2,3,4† Xiaofang Ma

Xiaofang Ma Hao Zhang

Hao Zhang Luying Zhong

Luying Zhong Xiaoli Chen

Xiaoli Chen