- Department of Clinical Nutrition, Faculty of Applied Medical Sciences, King Abdulaziz University, Jeddah, Saudi Arabia

Background: Inadequate nutritional awareness may lead to harmful eating habits and poor diet quality. Nutrition education interventions have been shown to improve nutritional knowledge and behaviors.

Aim: To assess the impact of nutrition education in Saudi Arabia, I reviewed relevant studies published between 2017 and 2024.

Methods: For the present systematic review, PubMed, Scopus, Google Scholar, Web of Science, and the Cochrane Library were searched. A total of 12 relevant articles published between January 2017 and January 2024 were identified; from the findings of these studies, the effectiveness of nutrition education in Saudi Arabia was assessed.

Results: The studies reviewed included children, adolescents, and adults in various regions of Saudi Arabia, with study durations ranging from 2 months to 2 years. In addition to changes in BMI and eating behaviors, four interventions showed significant improvement of physical activity, sedentary behavior, and body image satisfaction, as well as improvements in nutritional knowledge and eating habits. Despite a lack of statistically significant outcomes, five studies documented positive changes and beneficial impacts. Another study reported improved attitudes and behaviors toward healthy diets among teenagers, as well as improvements in nutritional understanding and dietary practices among school staff and students. However, one study revealed that its nutritional intervention was not adequate in providing education about physical exercise and another found no discernible changes in adolescents’ anthropometric measurements, physical activity, or harmful behaviors after an education intervention.

Conclusion: Nutrition education interventions especially school based done in Saudi Arabia, had significantly improved nutritional knowledge, physical activity, body image satisfaction and BMI.

Introduction

Dietary and lifestyle choices have changed since 1980, with a noticeable rise in eating out and at restaurants, leading to bigger portion sizes (1). Energy-dense and nutrient-poor diets dominated by fats, sweets, and processed foods have replaced diets rich in whole foods such as pulses and whole grains, which are low in refined oils and sugars (2, 3).

Four of the top 10 causes of death, including obesity, several types of cancer, and coronary heart disease, are caused by current eating trends (4). Among the leading causes of premature deaths worldwide are cardiovascular illnesses, type 2 diabetes mellitus, and various malignancies. Each year, 17.9 million people die from cardiovascular diseases, followed by 9.3 million from cancer, and 2.0 million from diabetes (5). Poor-quality nutrition and improper eating habits are major contributors to many chronic disorders (6). Diet-related risk factors were responsible for 7.9 million deaths and 187.7 million disability-adjusted life years (DALYs) lost in 2019 (7). Because of facts such as these, nutritional issues have received more attention in the last 10 years.

Children now consume more energy-dense foods, fewer fruits and vegetables, and excessive quantities of low-nutritional-value foods, according to recent studies (8–10). These poor eating habits are important indicators of metabolic problems in later life (11).

Inadequate nutritional awareness may be associated with unhealthy eating behaviors and poor-quality diets (12). Individuals’ self-perceptions of the value of balanced meals and their levels of nutritional awareness are known to influence their dietary choices and nutritional intake (13). Diet quality is directly impacted by nutritional awareness, which is also correlated with socioeconomic characteristics, specifically income and education, which impact the association between nutritional awareness and diet quality (14).

Maintaining a healthy or suitable body weight is facilitated by the establishment of healthy eating habits, which are mostly dependent on nutritional knowledge (15). Eating habits and nutritional knowledge are clearly linked, ensuring that vital nutrients are consumed throughout the life cycle (16). Nutrition education, whether formal or informal, can enhance understanding and positively influence food consumption (16).

Effective nutrition education can help decrease and control non-communicable diseases, including obesity-related diseases and disorders (17). For instance, nutrition education can promote awareness of carbohydrates and appropriate levels of daily carbohydrate intake, and thus help in the management of diabetes (18). In addition, teaching patients about the Dietary Approaches to Stop Hypertension (DASH) diet can help in the management of hypertension. Furthermore, depression, ovarian and breast cancer, obesity, diabetes, and asthma have all been found to be alleviated or prevented by adoption of a Mediterranean diet (19).

Researchers have found that nutrition education motivates children to participate in activities and promotes a general understanding of nutrition. Academic studies have also shown that people are becoming more conscious of the importance of eating a healthy diet, and that such awareness leads to changed eating habits (20). Poor eating habits also directly contribute to future non-communicable diseases. Education on nutrition is essential if individuals are to choose a healthy, balanced diet. The burden of non-communicable diseases may be lessened with the help of such information (21).

To combat childhood obesity, a number of national and international measures have been put into place. For instance, the Commission on Ending Childhood Obesity of the World Health Organization has made six key recommendations, including encouraging the consumption of nutritious foods, encouraging physical activity, promoting healthy eating habits, promoting preconception and pregnancy care, promoting physical activity and diet in early childhood, and promoting school-age children’s health (22). However, because these initiatives are focused on the creation of policies that call for a multi-sectoral approach, their implementation has been sluggish and uneven (23).

Morbidity is now a bigger issue than mortality in the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia, which has practically finished its epidemiological shift (24, 25). Noncommunicable diseases (NCDs), including diabetes and cardiovascular disease, account for 73% of all deaths in Saudi Arabia and are the cause of an increasing medical and economic burden (24–26).

With a significant increase in the use of ultra-processed foods and beverages, Saudi Arabia is experiencing a nutritional shift that is adversely altering dietary patterns and increasing diseases associated with poor nutrition. Furthermore, the deleterious impacts of growing urbanization on dietary habits and lifestyles are speeding up these changes (27, 28).

Concerns over diet quality (DQ) were highlighted by studies conducted in Saudi Arabia that showed bad eating habits, such as a high intake of fats, salt, and sugar and a low intake of fruits, vegetables, dairy products, nuts, and fish (29, 30). A prior study conducted in Saudi Arabia found that poor DQ was highly prevalent and suggested nutrition education that focused on DQ, sustainable nutrition, and eating habits (31). According to a different study, the Saudi population has bad eating habits, failing to consume the necessary amount of healthy food, consuming more fast food and fatty foods, and having poor breakfast and snacking habits (28).

Adult male obesity rates in Gulf nations like Saudi Arabia are over 30%, while adult female obesity rates are higher still, at about 40% (32). NCDs now account for 73% of all deaths in Saudi Arabia, a country which is now undergoing a major shift in its national health profile (33). In the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia (KSA), poor diet was found to be responsible for 17.4% of adult DALYs and 25.6% of adult fatalities in 2017 (34).

The Saudi Arabian Ministry of Health (MOH) has launched four nationwide programs to control the NCDs epidemic throughout the last 20 years. The first was in 2001 and was the first step in addressing NCDs. Through a number of resolutions, a specialist committee was tasked with creating and upgrading the program (35). The Saudi Arabian MOH collaborated with WHO to create the second and third measures to address the rising incidence of NCDs, which were implemented as Country Cooperation Strategies (2006–2011) and (2012–2016) (36). These strategies suggested that the Saudi healthcare system give the idea of health promotion—which includes leading a healthy lifestyle and preventing and controlling noncommunicable diseases—priority. The strategies also called for the creation of an integrated health education and research program, which should be appropriate given the circumstances in Saudi Arabia (33).

The National Executive Plan for NCDs (2014–2025), which comprises a thorough national strategy to combat NCDs, is the fourth effort. The goal of this approach is to manage and stop NCDs from getting worse (37). This strategy is in line with the Gulf Cooperation Council’s (GCC) NCD resolutions (38) and the WHO Global NCD Action Plan 2013–2020, which aims to meet the WHO’s targets of a 25% reduction in premature mortality from NCDs among individuals aged 30–70 years over a 15-year period (39). Initiating national NCD prevention strategies and supporting multisectoral activities in implementing preventive interventions known as “best buy” interventions are two of the guidelines provided by the global action plan to Member States. By focusing on common risk factors, the most effective interventions are available to lessen the burden of NCDs at the community level. These include encouraging physical activity, increasing costs on alcohol and tobacco, enforcing laws against alcohol and tobacco advertising, removing trans-fat from food supply chains, cutting back on salt intake, and early detection and treatment of noncommunicable diseases. According to WHO, these interventions were appropriate for use in health systems, cost-effective, and supported by evidence (39).

In accordance with WHO goals to enhance population health, strengthen the healthcare system, and better manage noncommunicable diseases, the Saudi Arabian government has put in place a variety of policy initiatives (40). In 2013, the Saudi MOH Executive Council passed a resolution establishing the Obesity Control Program. The Assistant Agency for Primary Healthcare, a division of the MOH’s Agency for Public Health, is home to the Genetic and Chronic Diseases Control General Department, which oversees this initiative. The program is founded on a clear vision and mission to end obesity, provide the best protection, and provide integrated healthcare services to individuals with any of the three levels of obesity in order to improve the health of Saudi Arabia’s population across all age groups (41).

The Saudi Guidelines for the Prevention and Management of Obesity were created at the national level to offer evidence-based strategies for addressing childhood and adult obesity (42). An intervention designed to lower the body weights of adolescents by 5% or more was reported in a recent Saudi study by Al-Daghri et al. (43); this intervention was carried out in Riyadh, and involved a sample of 363 adolescents aged between 12 and 18 years. Classroom-based instructional sessions were used to promote physical activity and provide teaching materials about healthy eating. When adherent and non-adherent groups were compared after 12 months, substantial decreases in BMI were recorded in the adherent group (43).

The purpose of this review was to examine systematically the impact of nutrition education interventions in Saudi Arabia by assessing changes in nutritional knowledge and habits by widening the search through Saudi studies published between 2017 and 2024. This time frame was selected to guarantee that the assessment takes into account the most current and pertinent data about nutrition education in Saudi Arabia. Because public health initiatives and nutrition-related programs have significantly increased in Saudi Arabia since the introduction of Saudi Vision 2030, and it enables the inclusion of recent studies that reflect current practices, policies, and population health behaviors.

Methods

Literature search strategy

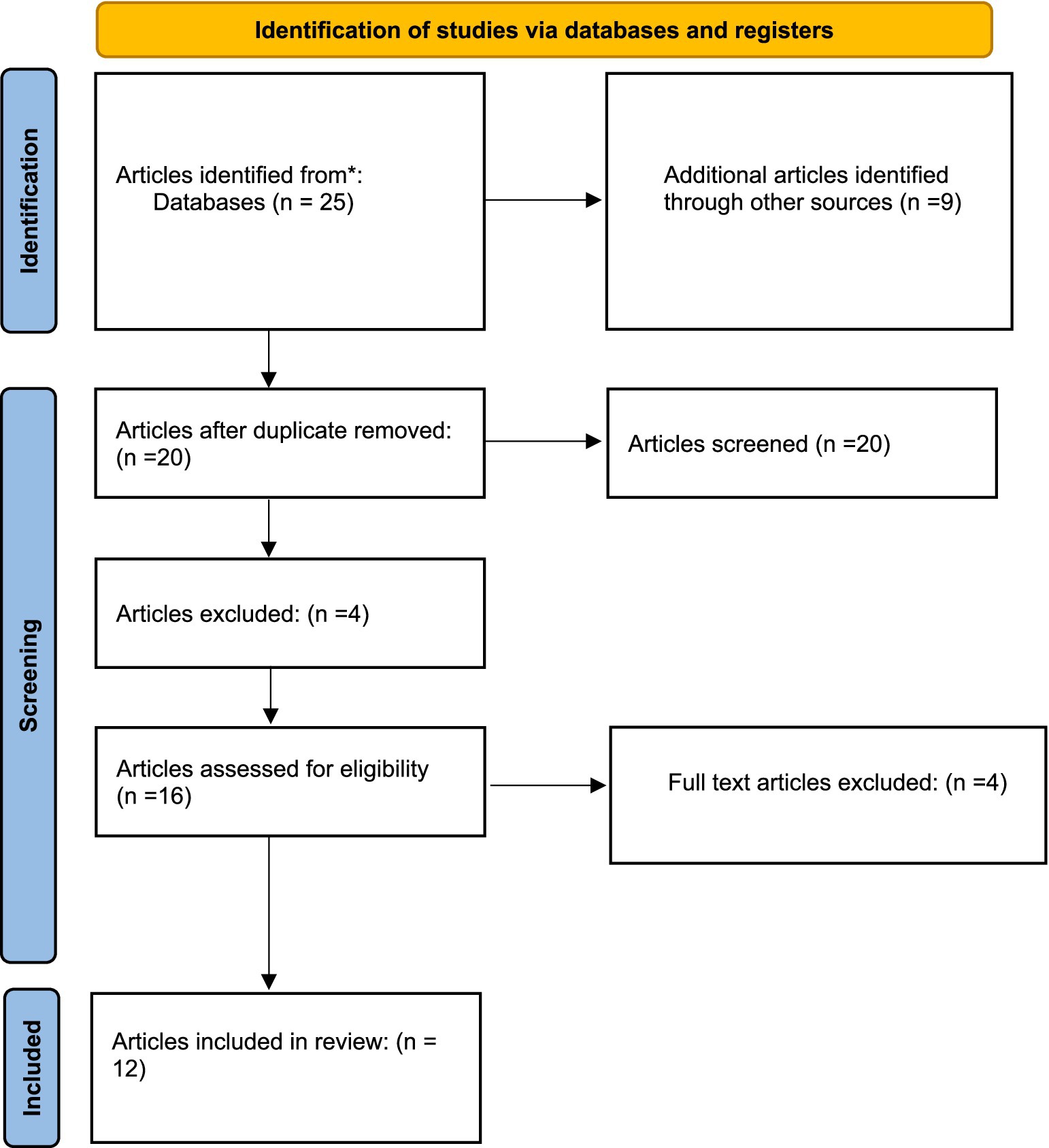

A comprehensive literature search was undertaken, utilizing databases such as PubMed, Scopus, Google Scholar, Web of Science, and Cochrane, to identify relevant articles published between January 2017 and January 2024. In addition, papers published in regional journals that might not be indexed in global databases were captured by incorporating regional databases like Saudi Digital Library, Arab World Research Source. Thus, a more thorough representation of nutrition education initiatives in Saudi Arabia was guaranteed by this all-encompassing strategy. A thorough search approach was used, combining important phrases associated with public health, nutrition education, and Saudi Arabia utilizing the Boolean operators “AND” and “OR.” The final search term that was used was: AND (“public health” OR “health promotion” OR “community health” OR “health behavior” OR “health outcomes”) AND (“Saudi Arabia” OR “Kingdom of Saudi Arabia” OR “KSA”) AND (“nutrition education” OR “nutrition intervention” OR “health education” OR “dietary education”). The studies included were randomized controlled trials (RCTs), quasi-experimental or observational studies and the population focus were students and adults. A thorough examination of collected references was carried out in search of potentially related literature. The titles and abstracts of every article that was retrieved were separately examined by the reviewer who was trained in public health, nutrition and epidemiology. After that, the whole texts of studies that might be eligible were examined in light of the established inclusion and exclusion criteria. The protocol for this review adhered to the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews (PRISMA) standards.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

Studies were eligible if they included nutrition education in any population group (children, adolescents, or adults) in Saudi Arabia. Given its critical role in promoting adequate early-life nutrition, they included treatments targeting mother and newborn nutrition, such as breastfeeding instruction. The PICOS eligibility criteria (Population, Intervention, Comparator, Outcomes, Study design) criteria were as follows:

• Population: Children, adolescents and adults residing in Saudi Arabia.

• Intervention: Nutrition education interventions delivered in any format focusing on nutritional habits.

• Comparator: Usual care, no intervention, or other types of interventions.

• Outcomes: Any reported outcomes related to nutrition knowledge, dietary behavior, or health status as reduction in BMI, change in fruits or vegetables intake, etc.

• Study design: Quasi-experimental studies, Cross-sectional studies, randomized controlled trial and pre-post intervention studies.

The methodological quality of the included studies was assessed using a critical appraisal checklist. The reviewer independently evaluated each paper, and discrepancies were settled by discussion. Domains like selection bias, comparability, outcome measurement, were evaluated by the tool and any disagreements were resolved through discussion or consultation with another re-viewer. Studies were excluded if they did not involve a dietary intervention in Saudi Arabia or did not focus on the outcomes and impact of these interventions. Studies published in a language other than English were also excluded.

Reporting

The PRISMA guidelines were followed and illustrated in (Figure 1) that was reproduced from an open access source under the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY 4.0) (44). Critical appraisal was conducted using Critical Appraisal Skills Program (CASP) tools.

Data extraction and analysis

The selected studies were thoroughly evaluated to determine their quality and relevance to our study objectives. To gather relevant information from the selected research, a standardized data-extraction form was developed. The following data were extracted, summarized, and presented descriptively: study characteristics, study design, participant information, intervention, findings, and conclusion.

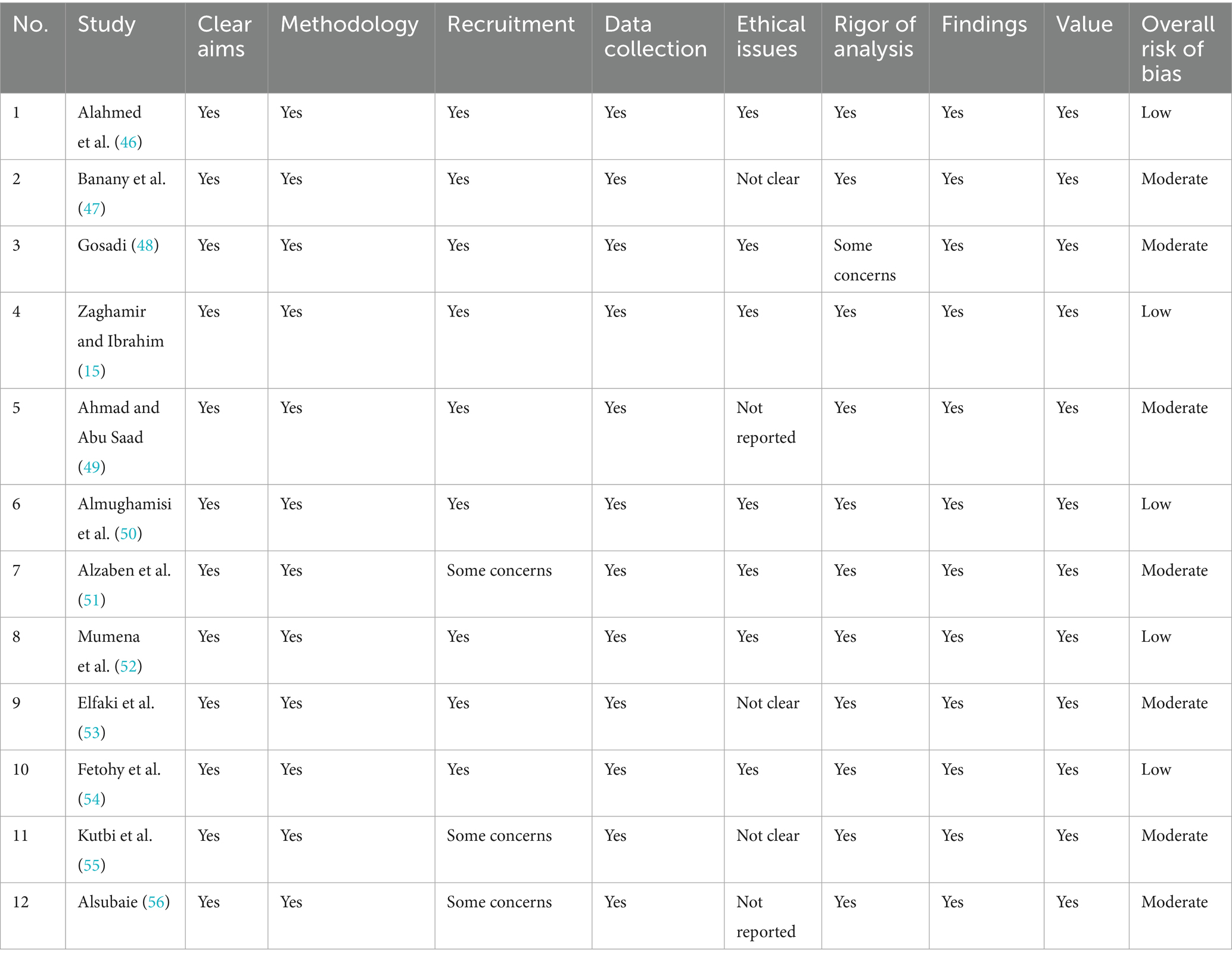

Assessment of risk of bias in studies

The methodological quality of the 12 chosen studies was assessed, and studies with a high risk of bias were excluded. The risk of bias was measured using pre-specified questions for each research design (Table 1) (45).

Results

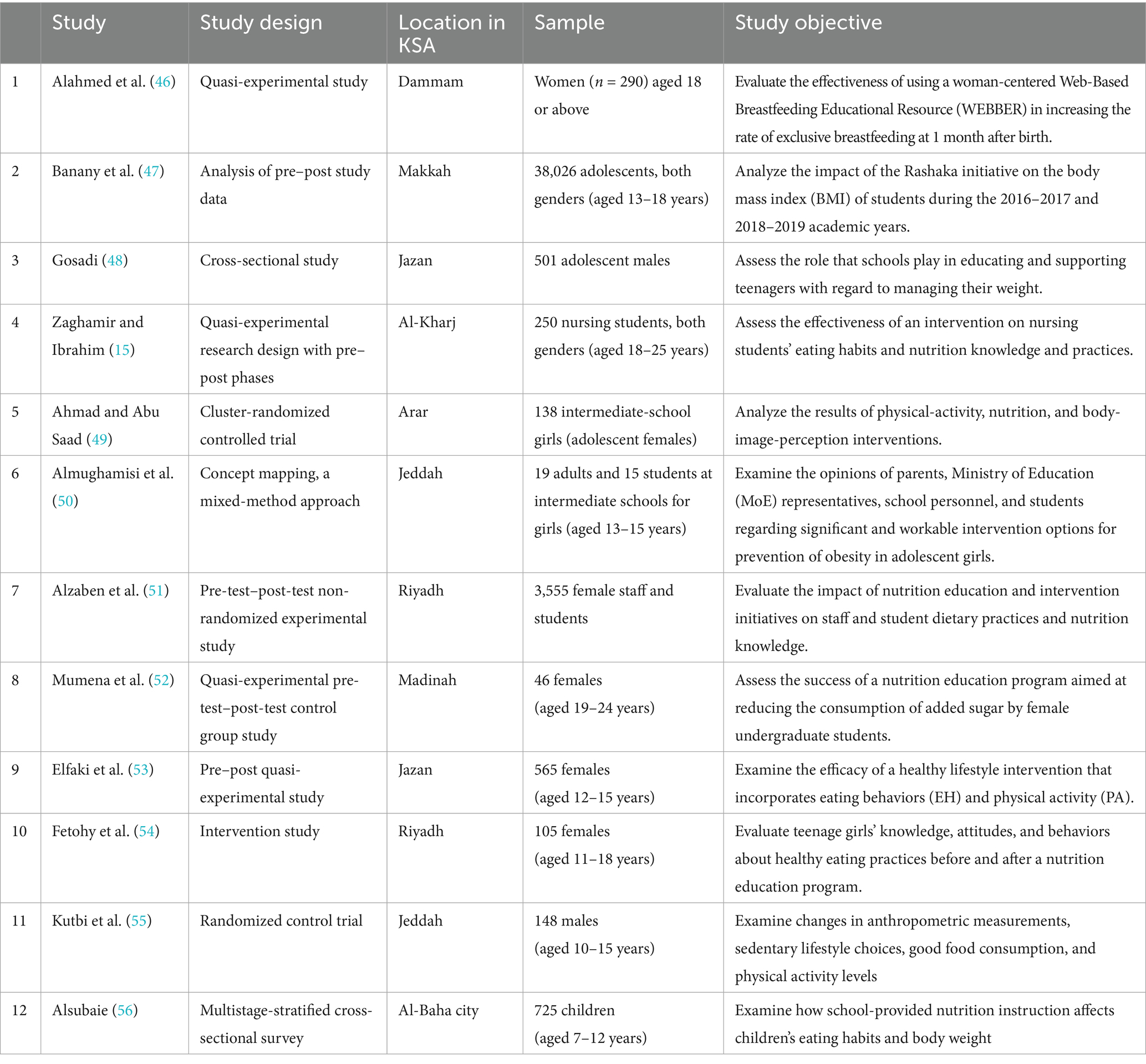

This systematic review included 12 articles (15, 46–56) of these, six focused on adolescents (47–49, 53–55), two covered both adults and adolescents (50, 51), and three involved adults (41, 42, 48), while only one study included children (57). Geographically, the selected articles covered various regions of Saudi Arabia, with two studies from Jeddah (50, 55), two from Riyadh (51, 54), and two from Jazan (48, 53). Additionally, one article was sourced from each of the following cities: Arar (49), Alkharj (45), Makkah (47), Dammam (46), Madinah (52), and Al-Baha (56).

The study populations varied significantly, ranging from 105 (54) to 38,026 (47) participants in articles focused on adolescents; 34 (50) to 3555 (51) participants in studies including both adults and adolescents, and 46 (52) to 290 (46) participants in studies with adults. In addition, one study examined 725 children (56). Eight interventions were school-based (47–50, 52–54, 56).

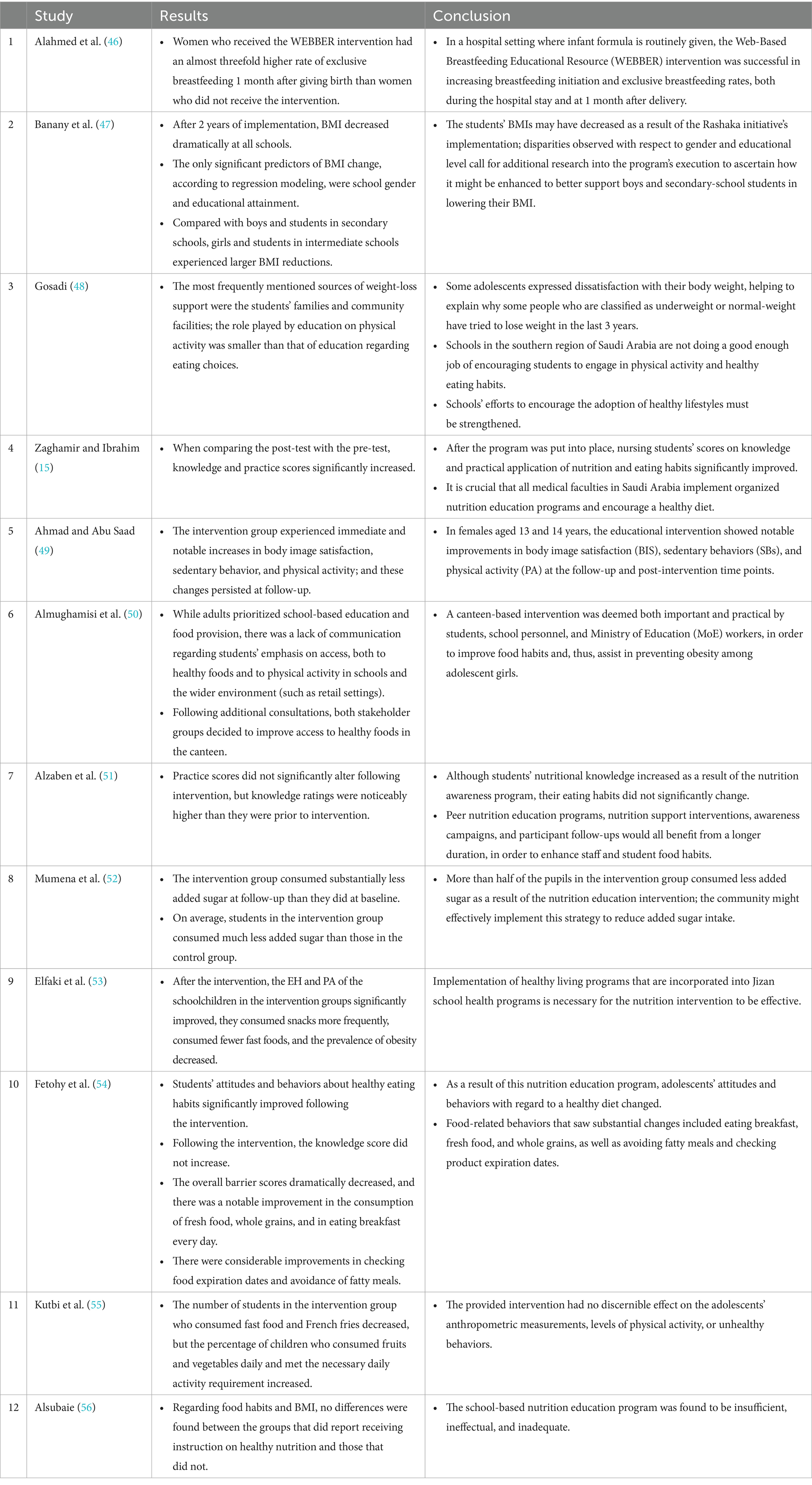

School-based interventions (n = 8 studies): Most interventions (4, 47–50, 53, 55, 56) were school-based. Four of these reported strong and statistically significant positive outcomes. For instance, Gosadi et al. (48) demonstrated improvements in physical activity and dietary choices; Ahmad and Abu Saad (49) showed sustained improvements in body image satisfaction and physical activity; Almughamisi et al. (50) observed better access to healthy canteen food; and Elfaki et al. (53) reported reduced obesity prevalence alongside improved dietary habits and physical activity.

Other school-based studies indicated positive trends, though without statistical significance. These included increased nutritional knowledge (51), and enhanced dietary practices (54). However, two studies found limited or no effect on anthropometric measures, dietary behavior, or BMI (55, 56).

Community-based interventions (n = 4 studies): Four studies (45, 46, 51, 52) were implemented in community or clinical settings. The outcomes were more variable: one study (46) reported nearly threefold improvements in breastfeeding rates with intervention; another (51) found improvements in nutritional knowledge and attitudes. Conversely, one community-based program (52) assessing short-term effects showed limited impact, and another reported suboptimal delivery of physical activity education compared with dietary education (48). Overall, outcomes were heterogeneous, reflecting differences in study populations, intervention content, duration, and settings. School-based programs generally showed more consistent positive effects, while community-based interventions had mixed results, often limited by short follow-up or narrow outcome measures.

The durations of the studies ranged from 2 months to 2 years. Two articles evaluated short-term effects (under 3 months) (52, 55); three articles investigated medium-term intervention effects (3 to 6 months); and one article assessed long-term effects (2 years) (47).

Only one study included a follow-up after 3 months (50). Reviewed studies included participants of both biological sexes, although most individual works targeted either female or male adolescents, due to gender-segregated schooling; only one study of adolescents involved both genders (57).

The primary findings from most of the reviewed studies (Table 2 and Table 3) indicated that four interventions resulted in strong positive and significant effects of the educational interventions. The first was the Gosadi et al. (48) study, where nutritional education had influenced physical activity and eating choices. The second was Ahmad and Abu Saad (49) study, where immediate and persisted follow-up increases in body image satisfaction, sedentary behavior, and physical activity was observed. The third was the study done by Almughamisi et al. (50), which showed improved access to healthy foods in the canteen after intervention. The fourth was the study done by Elfaki et al. (53), where a significant increase in snacks consumption and PA, and decrease in both fast foods consumption and prevalence of obesity was observed after intervention.

Five studies reported improvements and positive effects, although without statistically significant results; for example, the rate of exclusive breastfeeding was nearly three times higher among women who participated in the WEBBER intervention (46). Another study noted enhancements in nutritional knowledge and dietary practices among school students and staff, along with better attitudes and behaviors related to healthy diets among adolescents (51). However, one study found that the provision of education concerning physical activity was suboptimal, compared with education about eating habits (48). Additionally, one study found that completing a nutrition education program had no significant effects on anthropometric measures, physical activity, or unhealthy behaviors in adolescents (55). Lastly, no differences were observed in dietary behaviors and BMI between groups that reported being taught about healthy nutrition and those that did not (56).

Discussion

In this review, we aimed to assess the impact of nutrition education in Saudi Arabia, as reported in studies published between 2017 and 2024.

Eight of the studies included in this review involved adolescents (47–51, 53–55). Obesity in children and adolescents has been identified as a public health problem in both developed and developing countries (57). The Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC) nations—Saudi Arabia, the United Arab Emirates, Kuwait, Bahrain, Oman, and Qatar—have seen significant sociocultural and lifestyle changes in recent decades. An increased prevalence of high-calorie diets, sedentary lifestyles, and physical inactivity has led to a sharp rise in childhood obesity (58). In one 2022 report, 25.7% of school-age children in Saudi Arabia were classified as overweight or obese (59).

Among the 12 articles reviewed, eight studies described interventions carried out in schools (47–50, 53–56). Given that students spend a large portion of their time in schools, and because schools offer meal programs and physical education classes, among other environmental elements, schools can be seen as ideal places to undertake weight-related interventions (60, 61).

Five of the eight school-based studies in this review demonstrated that nutritional intervention positively improved the participants’ behaviors (47, 49, 50, 53, 54). In a recent study by Raut et al., school-age teenagers’ nutritional knowledge and attitudes were found to be improved by a health education intervention (62). In addition, a systematic analysis of 12 studies published between 2020 and 2023 revealed that school-based nutrition education interventions based on behavior change theories and models had a favorable impact on the eating habits of teenagers (63).

The promotion of healthy food intake, the promotion of physical activity, preconception and pregnancy care, early childhood diet and physical activity, and school-age children’s health are among the six primary recommendations made by the World Health Organization’s Commission on Ending Childhood Obesity (64). However, in three trials (48, 55, 56), interventions were found to be unsuccessful. In the study conducted by Gosadi et al. (48), it was found that schools in the southern region of Saudi Arabia were not doing enough to encourage children to be physically active and eat healthily. In the work of Kutbi et al. (55), it was discovered that adolescents’ anthropometric measurements, physical activity, and unhealthy behaviors were not significantly impacted by the given intervention. In the third study, it was found that a school-based nutrition education program was both inadequate and ineffective (56).

A study carried out in Australia also revealed a limited impact of school-based interventions; in this work, it was found that physical-activity, diet, or combination interventions had no effect on children’s weight or quality of life (65). Similar findings were made by researchers in China, who found that school-based interventions had only a minimal impact on childhood obesity (66). In addition, Habib-Mourad et al. assessed a nutritional intervention in Lebanon. In this work, it was stressed that neither the physical attributes of the school nor the availability of nutritious food options could be altered; had this not been the case, the diets of students might have been improved more significantly (67).

The interventions included in the studied articles showed that nutritional education had influenced physical activity and sedentary behavior, eaten choices as healthy foods consumption and decreased fast food, and body image satisfaction.

The study by Faiz et al., demonstrated the efficacy of nutritional education by seeing significant weight variations between the intervention group and the control group. With each follow-up over time, the experimental group’s weight, waist circumference, waist-to-hip ratio, and body fat % all significantly decreased in comparison to the controls (68). This result agrees with previous studies which showed that nutrition education has been a promising solution to improve dietary habits (68–70).

The current review included six studies that focused on adolescents (47–49, 53–55). Healthy eating habits are more likely to be followed by adolescents who have a solid understanding of nutrition (71, 72). Thus, it is crucial to teach kids about nutrition and stress the value of eating a well-balanced diet. One possible way to enhance eating habits has been through nutrition education (71, 72).

Numerous researches among adolescents have supported nutrition education as an effective means of disseminating nutrition knowledge (68, 73, 74). A systematic review that focused on the impact of nutritional education interventions on enhancing adolescents’ general health and well-being by encouraging healthier food choices and cultivating positive body image perceptions also disclosed the effect of nutrition education on body image perception (75). Additionally, prior research has shown that nutrition education has a good effect on increasing physical activity (76, 77).

Of the 12 studies included in the present review, only one assessed long-term effects (2 years) (47), while three investigated medium-term intervention effects (3 to 6 months) (15, 49, 51). Short-term effects (under 3 months) were reported in two articles (52, 55). According to Hoelscher et al. (78) interventions to combat childhood obesity are needed in low-income and ethnically diverse settings. A combination of primary and secondary techniques is expected to offer adequate exposure, resulting in considerable reductions in childhood obesity. There have been few studies on the long-term impacts of experiential nutrition education programs in schools. However, in one such study, conducted in 2024, it was found that giving hands-on nutrition instruction to children could have long-term benefits (79). The positive effect of long-term nutrition intervention of dietary behavior was observed in previous studies (80, 81).

In nine out of the 12 studies considered in the present review, improvements in intended outcomes upon program completion were demonstrated. In the study by Al-Daghri et al. that was carried out in Riyadh, Saudi Arabia, involving a sample of 363 adolescents between the ages of 12 and 18, an intervention was created with the goal of reducing the adolescents’ body weight by 5% or more. As part of the intervention, classroom-based instructional sessions were used to promote physical activity and provide teaching materials about healthy eating. After 12 months, when adherent and non-adherent groups were compared, substantial decreases in BMI were recorded in the adherent group (56).

Bashatah noted that focusing on food intake and encouraging physical exercise could improve nutritional knowledge and behaviors in students, thereby demonstrating the efficacy of nutrition education programs (82). In a study conducted in Ghana in 2024, it was found that school-based food and nutrition education interventions improved children’s awareness of nutrition and increased their consumption of fruit, but had no impact on anthropometric indices (83).

In a recent systematic review, it was found that lower caloric intake, increased consumption of fruits and vegetables, and reduced consumption of sugar-sweetened beverages were all promoted by nutrition education initiatives; in addition, improved knowledge, beliefs, and habits related to nutrition were all encouraged (84). Similar findings have also been reported in other studies (70, 85).

In order to properly prevent overweight and obesity in children and adolescents, the Saudi Guidelines for the Prevention and Management of Obesity also suggest creating long-lasting school-based interventions. An inter-sectoral strategy involving families should be taken into account in these interventions. Unfortunately, there is little information on the extent to which Saudi Arabian schools offer school-based interventions to help children and teenagers manage their weight (56).

To support future research and interventions that address the nutritional needs of the Saudi population, this systematic review provides a summary of empirical evidence to improve nutritional knowledge, improve dietary habits, increase physical activity, boost body image satisfaction, address rising obesity rates, increase exclusive breastfeeding rates, and reduce added sugar consumption among adults, adolescents, and children.

Limitations

The goal of the research presented in this study was to thoroughly describe and assess the body of knowledge regarding nutrition education initiatives carried out in Saudi Arabia. Our results were arranged according to the study’s design, location, sample, goals, and main results. The ability to prove causation is limited because most of the included research were cross-sectional, pre-post, or quasi-experimental in design. Furthermore, the overall quality of the evidence is diminished by the very small number of randomized controlled trials, which therefore limits the findings’ applicability to larger groups and contexts. Additionally, long-term follow-up to evaluate the durability of behavioral changes across time was absent from the majority of interventions as only one study tracked participants for up to 2 years, raising questions about how long-lasting the effects were. Furthermore, the possibility for a total lifestyle transformation was limited since physical activity components were either underemphasized or not included in nutrition instruction. These drawbacks show that more thorough, extensive, and carefully monitored research is required, especially randomized controlled trials with long-term follow-up, to bolster the body of evidence and direct Saudi Arabian nutrition education policy and practice. In addition, future studies should concentrate on creating multimodal therapies that incorporate education on physical activity and nutrition, with extensive follow-up times to assess long-term effects.

Conclusion

According to this review, nutrition education initiatives in Saudi Arabia have the potential to raise eating habits and increase nutritional awareness among a range of age groups. The evidence is conflicting, though, and variables in study design, intervention duration, delivery strategies, and cultural adaptability are probably what affect effectiveness. Few programs assessed the long-term sustainability of these changes, despite the fact that many reported excellent short-term results. To increase their impact on public health, future programs should concentrate on putting into practice evidence-based, culturally appropriate interventions with integrated lifestyle elements and thorough assessment.

Data availability statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/supplementary material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author/s.

Author contributions

SA: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Software, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author declares that financial support was received for the research and/or publication of this article. This project was funded by KAU Endowment (WAQF) at King Abdulaziz University, Jeddah, under grant. The authors, therefore, acknowledge with thanks WAQF and the Deanship of Scientific Research (DSR) for technical and financial support.

Conflict of interest

The author declares that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The author declares that no Gen AI was used in the creation of this manuscript.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Abbreviations

DASH, Dietary Approaches to Stop Hypertension; KSA, Kingdom of Saudi Arabia; DALYs, Disability-adjusted life years; BMI, Body Mass Index; GCC, The Gulf Cooperation Council.

References

1. Espinosa-Salas, S, and Gonzalez-Arias, M. Behavior modification for lifestyle improvement. Treasure Island, FL: StatPearls Publishing (2024).

2. Aboul-Enein, BH, Bernstein, J, and Neary, AC. Dietary transition and obesity in selected Arabic speaking countries: a review of the current evidence. East Mediterr Health J. (2017) 22:763–70. doi: 10.26719/2016.22.10.763

3. Bodirsky, BL, Dietrich, JP, Martinelli, E, Stenstad, A, Pradhan, P, Gabrysch, S, et al. The ongoing nutrition transition thwarts long-term targets for food security, public health and environmental protection. Sci Rep. (2020) 10:19778. doi: 10.1038/s41598-020-75213-3

4. Neuhouser, ML. The importance of healthy dietary patterns in chronic disease prevention. Nutr Res. (2019) 70:3–6. doi: 10.1016/j.nutres.2018.06.002

5. World Health Organization. Noncommunicable diseases. Geneva: World Health Organization (2023). Available online at: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/noncommunicable-diseases.

6. Adolph, TE, and Tilg, H. Western diets and chronic diseases. Nat Med. (2024) 30:2133–47. doi: 10.1038/s41591-024-03165-6

7. Delavari, M, Sønderlund, AL, Swinburn, B, Mellor, D, and Renzaho, A. Acculturation and obesity among migrant populations in high income countries--a systematic review. BMC Public Health. (2013) 13:458. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-13-458

8. Mahmood, L, Flores-Barrantes, P, Moreno, LA, Manios, Y, and Gonzalez-Gil, EM. The influence of parental Dietary behaviors and practices on children's eating habits. Nutrients. (2021) 13:1138. doi: 10.3390/nu13041138

9. Dallacker, M, Knobl, V, Hertwig, R, and Mata, J. Effect of longer family meals on children's fruit and vegetable intake: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Netw Open. (2023) 6:e236331. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2023.6331

10. Nasreddine, LM, Kassis, AN, Ayoub, JJ, Naja, FA, and Hwalla, NC. Nutritional status and dietary intakes of children amid the nutrition transition: the case of the eastern Mediterranean region. Nutr Res. (2018) 57:12–27. doi: 10.1016/j.nutres.2018.04.016

11. Shang, X, Liu, J, Zhu, Z, Zhang, X, Huang, Y, Liu, S, et al. Healthy dietary patterns and the risk of individual chronic diseases in community-dwelling adults. Nat Commun. (2023) 14:6704. doi: 10.1038/s41467-023-42523-9

12. Ziso, D, Chun, OK, and Puglisi, MJ. Increasing access to healthy foods through improving food environment: a review of mixed methods intervention studies with residents of low-income communities. Nutrients. (2022) 14:2278. doi: 10.3390/nu14112278

13. Scalvedi, ML, Gennaro, L, Saba, A, and Rossi, L. Relationship between nutrition knowledge and Dietary intake: an assessment among a sample of Italian adults. Front Nutr. (2021) 8:714493. doi: 10.3389/fnut.2021.714493

14. Alkerwi, A, Sauvageot, N, Malan, L, Shivappa, N, and Hébert, JR. Association between nutritional awareness and diet quality: evidence from the observation of cardiovascular risk factors in Luxembourg (ORISCAV-LUX) study. Nutrients. (2015) 7:2823–38. doi: 10.3390/nu7042823

15. Zaghamir, DEF, and Ibrahim, AM. Efficiency of an intervention study on nursing students' knowledge and practices regarding nutrition and dietary habits. Libyan J Med. (2023) 18:2281121. doi: 10.1080/19932820.2023.2281121

16. Cena, H, and Calder, PC. Defining a healthy diet: evidence for the role of contemporary Dietary patterns in health and disease. Nutrients. (2020) 12:334–49. doi: 10.3390/nu12020334

17. Ruthsatz, M, and Candeias, V. Non-communicable disease prevention, nutrition and aging. Acta Biomed. (2020) 91:379–88. doi: 10.23750/abm.v91i2.9721

18. American Diabetes Association. Diabetes and food: Understanding carbs, find your balance. American Diabetes Association (2024). Available online at: https://diabetes.org/food-nutrition/understanding-carbs.

19. Filippou, CD, Tsioufis, CP, Thomopoulos, CG, Mihas, CC, Dimitriadis, KS, Sotiropoulou, LI, et al. Dietary approaches to stop hypertension (DASH) diet and blood pressure reduction in adults with and without hypertension: a systematic review and Meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Adv Nutr. (2020) 11:1150–60. doi: 10.1093/advances/nmaa041

20. Dunn, CG, Burgermaster, M, Adams, A, Koch, P, Adintori, PA, and Stage, VC. A systematic review and content analysis of classroom teacher professional development in nutrition education programs. Adv Nutr. (2019) 10:351–9. doi: 10.1093/advances/nmy075

21. Fletcher, A, and Carey, E. Knowledge, attitudes, and practices in the provision of nutritional care. Br J Nurs. (2011) 20:615–20. doi: 10.12968/bjon.2011.20.10.615

22. World Health Organization. Report of the commission on ending childhood obesity: Implementation plan: Executive summary. Geneva: World Health Organization. (2017). Available online at: https://iris.who.int/handle/10665/259349?locale-attribute=ar&show=full.

23. Lister, NB, Baur, LA, Felix, JF, Hill, AJ, Marcus, C, Reinehr, T, et al. Child and adolescent obesity. Nat Rev Dis Primers. (2023) 9:24–43. doi: 10.1038/s41572-023-00435-4

24. World Health Organization. Noncommunicable diseases progress monitor. Geneva: World Health Organization (2020). Available online at: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/ncd-progress-monitor-2020 (Accessed Aug 28, 2020).

25. Zaidan, A. Three decades of trends in risk factors attributed to disease burden in Saudi Arabia: findings from the global burden of disease study 2021. Healthcare (Basel). (2025) 13:1717–32. doi: 10.3390/healthcare13141717

26. Albejaidi, F, and Nair, KS. Addressing the burden of non-communicable diseases: Saudi Arabia’s challenges in achieving vision 2030. J Pharm Res Int. (2021) 33:34–44. doi: 10.9734/jpri/2021/v33i35A31871

27. Popkin, BM, and Ng, SW. The nutrition transition to a stage of high obesity and noncommunicable disease prevalence dominated by ultra-processed foods is not inevitable. Obes Rev. (2022) 23:e13366. doi: 10.1111/obr.13366

28. Bukhari, M, and Dietary, H. Habits for adults in Saudi Arabia. Univers J Public Health. (2024) 12:499–507. doi: 10.13189/ujph.2024.120307

29. AlHusseini, N, Sajid, M, Akkielah, Y, Khalil, T, Alatout, M, Cahusac, P, et al. Vegan, vegetarian and meat-based diets in Saudi Arabia. Cureus. (2021) 9:e18073. doi: 10.7759/cureus.1807

30. Moradi-Lakeh, M, El Bcheraoui, C, Afshin, A, Daoud, F, AlMazroa, MA, Al Saeedi, M, et al. Diet in Saudi Arabia: findings from a nationally representative survey. Public Health Nutr. (2017) 20:1075–81. doi: 10.1017/S1368980016003141

31. Alzaben, AS, Alresheedi, KR, Bakry, HM, Ozayb, RA, Aldawsari, HA, Alnamshan, AO, et al. Assessing the association between diet quality and sociodemographic factors in young Saudi adults. Front Nutr. (2025) 12:1641284. doi: 10.3389/fnut.2025.1641284

32. Balhareth, A, Meertens, R, Kremers, S, and Sleddens, E. Overweight and obesity among adults in the Gulf states: a systematic literature review of correlates of weight, weight-related behaviors, and interventions. Obes Rev. (2019) 20:763–93. doi: 10.1111/obr.12826

33. Hazazi, A, and Wilson, A. Noncommunicable diseases and health system responses in Saudi Arabia: focus on policies and strategies. A qualitative study. Health Res Policy Syst. (2022) 20:63–70. doi: 10.1186/s12961-022-00872-9

34. Al-Gassimi, O, Shah, HBU, Sendi, R, Ezmeirlly, HA, Ball, L, and Bakarman, MA. Nutrition competence of primary care physicians in Saudi Arabia: a cross-sectional study. BMJ Open. (2020) 10:e033443. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2019-033443

35. GCC Countries. First BA regional workshop on the epidemiology of diabetes and other non-communicable diseases. Jeddah, Saudi Arabia. GCC Countries (2009).

36. World Health Organization. Country cooperation strategy for WHO and Saudi Arabia 2012–2016. Geneva: World Health Organization. Regional Office for the Eastern Mediterranean (2013). Available online at: https://apps.who.int/iris/ handle/10665/113227 (Accessed Sep 16, 2021).

37. Ministry of Health. Saudi Arabia national strategy for prevention of NCDs. Riyadh: Ministry of Health (2014).

38. Gulf Health Council. Control of non-communicable diseases. Riyadh: Gulf Health Council (2020). Available online at: http://ghc.sa/en-us/pages/noncommunicablediseaseprogram.aspx. (Accessed Sep 2, 2020).

39. World Health Organization. Global action plan for the prevention and control of noncommunicable diseases 2013–2020. Geneva: World Health Organization (2013). Available online at: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789241506236 (Accessed Sept 28, 2021).

40. Alharbi, NS, Alotaibi, M, and de Lusignan, S. An analysis of health policies designed to control and prevent diabetes in Saudi Arabia. Glob J Heal Sci. (2016) 8:233–41. doi: 10.5539/gjhs.v8n11p233

41. Saudi Ministry of Health (MOH). Obesity control Program (2025). Available online at: https://www.moh.gov.sa/en/OCP/Pages/AbouttheProgram.aspx.

42. Saudi Ministry of Health. Saudi guidelines on the prevention and management of obesity. (2016). Available online at: https://www.moh.gov.sa/Ministry/About/Health%20Policies/008.pdf.

43. Al-Daghri, NM, Amer, OE, Khattak, MNK, Hussain, SD, Alkhaldi, G, Alfawaz, HA, et al. Attendance-based adherence and outcomes of obesity management program in Arab adolescents. Children (Basel). (2023) 10:1449–65. doi: 10.3390/children10091449

44. Almuqairsha, SA, Al-Harbi, FA, Alaidah, AM, Al-Mutairi, TA, Al-Oadah, EK, Almatham, AE, et al. Demographics, clinical characteristics, and management strategies of epilepsy in Saudi Arabia: a systematic review. Cureus. (2024) 16:e63436. doi: 10.7759/cureus.63436

45. Viswanathan, M, Ansari, MT, Berkman, ND, Chang, S, Hartling, L, McPheeters, M, et al. Assessing the risk of Bias of individual studies in systematic reviews of health care interventions. 2012 mar 8. In: methods guide for effectiveness and comparative effectiveness reviews. Rockville (MD): Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (US) (2008).

46. Alahmed, S, Frost, S, Fernandez, R, Win, K, Mutair, AA, Harthi, MA, et al. Evaluating a woman-centred web-based breastfeeding educational intervention in Saudi Arabia: a before-and-after quasi-experimental study. Women Birth. (2024) 37:101635. doi: 10.1016/j.wombi.2024.101635

47. Banany, M, Gebel, K, and Sibbritt, D. An examination of the predictors of change in BMI among 38 026 school students in Makkah. Saudi Arabia Int Health. (2024) 16:463–7. doi: 10.1093/inthealth/ihae029

48. Gosadi, IM. Assessment of school contributions to healthy eating, physical activity education, and support for weight-loss attempts among adolescents from Jazan, Saudi Arabia. Nutrients. (2023) 15:4688. doi: 10.3390/nu15214688

49. Ahmad Bahathig, A, and Abu, SH. The effects of a physical activity, nutrition, and body image intervention on girls in intermediate schools in Saudi Arabia. Int J Environ Res Public Health. (2022) 19:11314. doi: 10.3390/ijerph191811314

50. Almughamisi, M, O'Keeffe, M, and Harding, S. Adolescent obesity prevention in Saudi Arabia: co-identifying actionable priorities for interventions. Front Public Health. (2022) 10:863765. doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2022.863765

51. Alzaben, AS, Alnashwan, NI, Alatr, AA, Alneghamshi, NA, and Alhashem, AM. Effectiveness of a nutrition education and intervention programme on nutrition knowledge and dietary practice among Princess Nourah Bint Abdulrahman University's population. Public Health Nutr. (2021) 24:1854–60. doi: 10.1017/S1368980021000604

52. Mumena, WA, Abdulhakeem, FA, Jannadi, NH, Almutairi, SA, Aloufi, SM, Bakhishwain, AA, et al. Nutrition education intervention to limit added sugar intake among university female students. Prog Nutr. (2020) 22:e2020038. doi: 10.23751/pn.v22i3.9764

53. Elfaki, FAE, Khalafalla, HE, Gaffar, AM, Moukhyer, ME, Bani, IA, and Mahfouz, MS. Effect of healthy lifestyle interventions in schools of Jazan City, Kingdom of Saudi Arabia: a quasi-experimental study. Arab J Nutr Exerc. (2020) 5:1–14. doi: 10.18502/ajne.v5i1.6911

54. Fetohy, EM, Mahboub, SM, and Abusalih, HH. The effect of an educational intervention on knowledge, attitude and behavior about healthy dietary habits among adolescent females. JHIPH. (2020) 50:106–12. doi: 10.21608/jhiph.2020.109034

55. Kutbi, MS, Al-Jasir, BA, Khouja, JH, and Aljefri, RA. School intervention program to promote healthy lifestyle among male adolescent students in king faisal residential city, Jeddah, Western region, 2014-15. Int J Adv Res. (2019) 7:423–32. doi: 10.21474/IJAR01/9680

56. Alsubaie, ASR. An assessment of nutrition education in primary schools and its effect on students Dietary behaviors and body mass index in Saudi Arabia. Majmaah J Health Sci. (2017) 7:45–65. doi: 10.5455/mjhs.2017.02.006

57. Sahoo, K, Sahoo, B, Choudhury, AK, Sofi, NY, Kumar, R, and Bhadoria, AS. Childhood obesity: causes and consequences. J Family Med Prim Care. (2015) 4:187–92. doi: 10.4103/2249-4863.154628

58. Al Yazeedi, B, and Berry, DC. Childhood overweight and obesity is increasing in gulf cooperation council countries: a review of the literature. J Transcult Nurs. (2019) 30:603–15. doi: 10.1177/1043659619829528

59. Albaker, W, Saklawi, R, Bah, S, Motawei, K, Futa, B, and Al-Hariri, M. What is the current status of childhood obesity in Saudi Arabia?: evidence from 20,000 cases in the Eastern Province: a cross-sectional study. Medicine (Baltimore). (2022) 101:e29800. doi: 10.1097/MD.0000000000029800

60. Feng, L, Wei, DM, Lin, ST, Maddison, R, Ni Mhurchu, C, Jiang, Y, et al. Systematic review and meta-analysis of school-based obesity interventions in mainland China. PLoS One. (2017) 12:e0184704. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0184704

61. Liu, Z, Xu, HM, Wen, LM, Peng, YZ, Lin, LZ, Zhou, S, et al. A systematic review and meta-analysis of the overall effects of school-based obesity prevention interventions and effect differences by intervention components. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act. (2019) 16:95–107. doi: 10.1186/s12966-019-0848-8

62. Raut, S, Kc, D, Singh, DR, Dhungana, RR, Pradhan, PMS, and Sunuwar, DR. Effect of nutrition education intervention on nutrition knowledge, attitude, and diet quality among school-going adolescents: a quasi-experimental study. BMC Nutr. (2024) 10:35–45. doi: 10.1186/s40795-024-00850-0

63. Flores-Vázquez, AS, Rodríguez-Rocha, NP, Herrera-Echauri, DD, and Macedo-Ojeda, G. A systematic review of educational nutrition interventions based on behavioral theories in school adolescents. Appetite. (2024) 192:107087. doi: 10.1016/j.appet.2023.107087

64. Barnes, C, Hall, A, Nathan, N, Sutherland, R, McCarthy, N, Pettet, M, et al. Efficacy of a school-based physical activity and nutrition intervention on child weight status: findings from a cluster randomized controlled trial. Prev Med. (2021) 153:106822. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2021.106822

65. Hung, LS, Tidwell, DK, Hall, ME, Lee, ML, Briley, CA, and Hunt, BP. A meta-analysis of school-based obesity prevention programs demonstrates limited efficacy of decreasing childhood obesity. Nutr Res. (2015) 35:229–40. doi: 10.1016/j.nutres.2015.01.002

66. Habib-Mourad, C, Ghandour, LA, Moore, HJ, Nabhani-Zeidan, K, Adetayo, N, Hwalla, C, et al. Promoting healthy eating and physical activity among school children: findings from health-E-PALS, the first pilot intervention from Lebanon. BMC Public Health. (2014) 14:940–52. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-14-940

67. Aiz, A, Nawaz, S, Raza, Q, Imran, K, Batool, R, Firyal, S, et al. Effectiveness of nutrition education on weight loss and body metrics among obese adults: an interventional study. Cureus. (2024) 16:e74373. doi: 10.7759/cureus.74373

68. Singh, A, Grover, K, and Sharma, N. Effectiveness of nutrition intervention to overcome the problem of Anaemia. Food Sci Res J. (2014) 5:184–9. doi: 10.15740/HAS/FSRJ/5.2/184-189

69. Salas-Salvadó, J, Díaz-López, A, Ruiz-Canela, M, Basora, J, Fitó, M, Corella, D, et al. Effect of a lifestyle intervention program with energy-restricted Mediterranean diet and exercise on weight loss and cardiovascular risk factors: one-year results of the PREDIMED-plus trial. Diabetes Care. 42:777–88. doi: 10.2337/dc18-0836

70. Lua, PL, and Putri Elena, WD. The impact of nutrition education interventions on the dietary habits of college students in developed nations: a brief review. Malays J Med Sci. (2012) 19:4–14.

71. Grosso, G, Mistretta, A, Turconi, G, Cena, H, Roggi, C, and Galvano, F. Nutrition knowledge and other determinants of food intake and lifestyle habits in children and young adolescents living in a rural area of Sicily. South Italy Public Health Nutr. (2013) 16:1827–36. doi: 10.1017/S1368980012003965

72. Alam, N, Roy, SK, Ahmed, T, and Ahmed, AM. Nutritional status, dietary intake, and relevant knowledge of adolescent girls in rural Bangladesh. J Health Popul Nutr. (2010) 28:86–94. doi: 10.3329/jhpn.v28i1.4527

73. Bandyopadhyay, L, Maiti, M, Dasgupta, A, and Paul, B. Intervention for improvement of knowledge on anemia prevention: a schoolbased study in a rural area of West Bengal. Int J Health Allied Sci. (2017) 6:69–74. doi: 10.4103/ijhas.IJHAS_94_16

74. Naghashpour, M, Shakerinejad, G, Lourizadeh, MR, Hajinajaf, S, and Jarvandi, F. Nutrition education based on health belief model improves dietary calcium intake among female students of junior high schools. J Health Popul Nutr. (2014) 32:420–9.

75. Pushpa, BS, Abdul Latif, SN, Sharbini, S, Murang, ZR, and Ahmad, SR. Nutrition education and its relationship to body image and food intake in Asian young and adolescents: a systematic review. Front Nutr. (2024) 11:1287237. doi: 10.3389/fnut.2024.1287237

76. Wang, M, Guo, Y, Zhang, Y, Xie, S, Yu, Z, Luo, J, et al. Promoting healthy lifestyle in Chinese college students: evaluation of a social media-based intervention applying the RE-AIM framework. Eur J Clin Nutr. (2021) 75:335–44. doi: 10.1038/s41430-020-0643-2

77. Lee, JH, Lee, HS, Kim, H, Kwon, YJ, Shin, J, and Lee, JW. Association between nutrition education, dietary habits, and body image misperception in adolescents. Asia Pac J Clin Nutr. (2021) 30:512–21. doi: 10.6133/apjcn.202109_30(3).0018

78. Hoelscher, DM, Butte, NF, Barlow, S, Vandewater, EA, Sharma, SV, Huang, T, et al. Incorporating primary and secondary prevention approaches to address childhood obesity prevention and treatment in a low-income, ethnically diverse population: study design and demographic data from the Texas childhood obesity research demonstration (TX CORD) study. Child Obes. (2015) 11:71–91. doi: 10.1089/chi.2014.0084

79. Lier, LN, Mila, EV, and Havermans, RC. Long-term effects of a school-based experiential nutrition education intervention. Int J Health Promot Educ. (2024) 12:1–10. doi: 10.1080/14635240.2024.2421557

80. Marshall, AN, Markham, C, Ranjit, N, Bounds, G, Chow, J, and Sharma, SV. Long-term impact of a school-based nutrition intervention on home nutrition environment and family fruit and vegetable intake: a two-year follow-up study. Prev Med Rep. (2020) 20:101247. doi: 10.1016/j.pmedr.2020.101247

81. Zarnowiecki, DM, Dollman, J, and Parletta, N. Associations between predictors of children's dietary intake and socioeconomic position: a systematic review of the literature. Obes Rev. (2014) 15:375–91. doi: 10.1111/obr.12139

82. Bashatah, A. Nutritional habits among nursing students using Moore index for nutrition self-care: a cross-sectional study from the nursing school Riyadh, Saudi Arabia. Nurs Open. (2020) 7:1846–51. doi: 10.1002/nop2.572

83. Mogre, V, Sefogah, PE, Adetunji, AW, Olalekan, OO, Gaa, PK, Anie, HA, et al. A school-based food and nutrition education intervention increases nutrition-related knowledge and fruit consumption among primary school children in northern Ghana. BMC Public Health. (2024) 24:1739. doi: 10.1186/s12889-024-19200-7

84. Cotton, W, Dudley, D, Peralta, L, and Werkhoven, T. The effect of teacher-delivered nutrition education programs on elementary-aged students: an updated systematic review and meta-analysis. Prev Med Rep. (2020) 20:101178. doi: 10.1016/j.pmedr.2020.101178

Keywords: impact, nutrition, education, interventions, review, Saudi

Citation: Alsharif SN (2025) Nutrition education and its public health impact in Saudi Arabia: a systematic review. Front. Public Health. 13:1700254. doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2025.1700254

Edited by:

Enas A. Assaf, Applied Science Private University, JordanReviewed by:

Dalal Usamah Zaid Alkazemi, Kuwait University, KuwaitMaria João Lima, Instituto Politecnico de Viseu, Portugal

Copyright © 2025 Alsharif. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Sarah N. Alsharif, c25hbHNoYXJpZkBrYXUuZWR1LnNh

Sarah N. Alsharif

Sarah N. Alsharif