- 1University of Birmingham, Dubai, United Arab Emirates

- 2American University of Beirut, Beirut, Lebanon

- 3University of Cambridge Public Health, Cambridge, United Kingdom

- 4The Hashemite University, Az-Zarqa, Jordan

Editorial on the Research Topic

Science diplomacy and neocolonialism: lessons from the field with a view to the future

Introduction

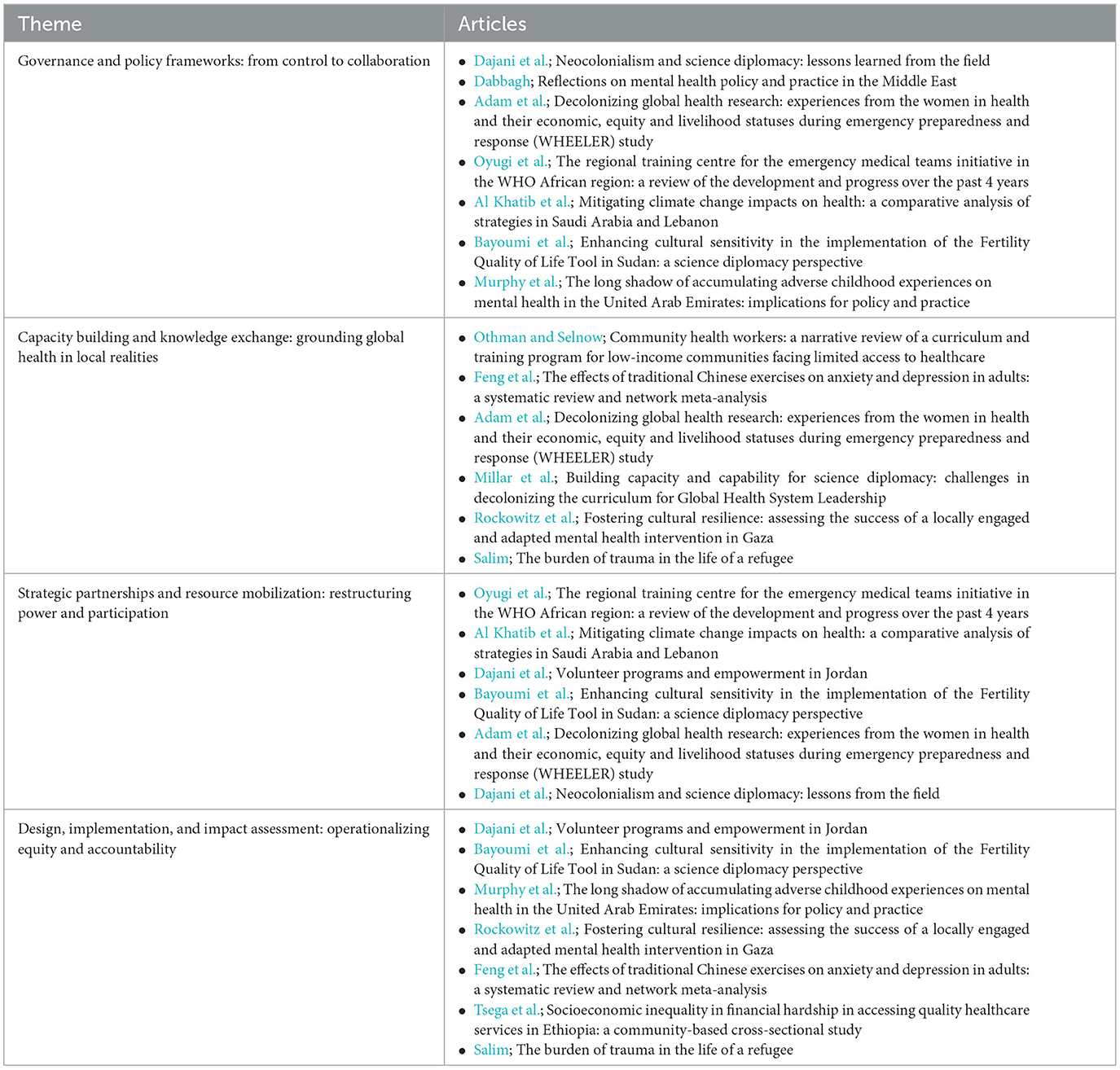

Science diplomacy, understood as the use of scientific cooperation to inform foreign policy and advance shared public goods, has long unfolded under neocolonial conditions that marginalize researchers and publics in the Global South (1). Power asymmetries shape what questions are asked, who leads, how evidence is valued, and who ultimately benefits (1). Recent crises, from COVID-19 to protracted conflicts including those in Ukraine and Palestine, have further exposed how public health collaboration can reproduce inequities rather than redress them (Dajani et al.). Yet across the Global South, practitioners are assembling more inclusive and flexible models that include co-governed research, regionally anchored training platforms, culturally validated metrics, and financing arrangements designed to protect local leadership. This Research Topic examines how public health research and promotion interact with science diplomacy in such contexts, identifies practical strategies for multilateral and interdisciplinary partnerships, and showcases case studies that challenge hierarchies and travel across diverse settings (see included articles in Table 1). While prior work has often centered South America and Asia, this Research Topic highlights under-studied Middle East and African contexts, contributing to a more balanced comparative literature on science diplomacy.

Governance and policy frameworks: from control to collaboration

Science diplomacy is recast in these contributions as a governance project, not only about brokering ties across borders but about redesigning the rules, incentives, and relationships through which knowledge is produced and applied. The common pivot is away from control, top-down, externally defined, and often Western-led, toward collaboration grounded in reciprocity, plural knowledge systems, and local ownership. The WHEELER study in Kenya exemplifies this turn by embedding Community Research Advisory Groups and Local Advisory Boards into the research process and applying gender analysis to ensure representation (Adam et al.). The WHO EMT Training Center in Addis Ababa illustrates another model of collaborative governance, transforming an evacuation site into a regional training hub aligned with the African Union's Agenda 2063, while candidly acknowledging gaps in monitoring and sustainability (Oyugi et al.). Reflections on public mental health in Palestine and the UAE underscore how governance can emerge from daily practice rather than imported models, with narrative approaches to suicide and autism pathways designed through community consultation (Dabbagh). Critiques of ethics rule-setting bodies reveal how the absence of Muslim scientists undermines legitimacy, while the collapse of the UK's Global Challenges Research Fund highlights how dependence on short-cycle, externally controlled grants unravels equity projects (Dajani et al.). Collectively, these studies argue that equitable governance requires specifying co-decision structures from proposal to publication, reforming ethics and standard-setting bodies for cultural and regional diversity, investing in regional capacity platforms with robust monitoring and evaluation, and designing multi-year funding instruments with safeguards against political or budgetary shocks. These cases also demonstrate Global South researchers as protagonists, shaping agendas beyond state hierarchies and asserting agency in international systems.

Capacity building and knowledge exchange: grounding global health in local realities

Capacity building is presented here not as a one-way transfer of “best practices” but as a dialogic, context-rooted process that enables communities and researchers to co-produce priorities and solutions. The Community Health Worker program developed by WiRED International reframes workforce expansion as community-owned professionalization, offering open, offline-capable curricula for rapid and low-cost training that can be adapted to local languages and norms (Othman and Selnow). A meta-analysis of Traditional Chinese Exercises shows that cultural consonance is not an accessory but a mechanism of effectiveness, since embedded practices such as tai chi and qigong drive adherence and outcomes, raising questions about how such modalities can be sensitively adapted while maintaining therapeutic cores (Feng et al.). WHEELER again provides lessons on reciprocity by design, combining local resource centers, mentorship ladders, and sense-making workshops into a learning system that endures beyond a single project (Adam et al.). An article on international branch campuses highlights the paradoxes of decolonizing education from privileged institutional settings but demonstrates how dialogic pedagogy and co-developed competency frameworks with regional partners can make education itself a form of diplomacy (Millar et al.). Finally, the Tarkiz program in Gaza illustrates long-horizon adaptation, showing how 15 years of locally stewarded mental health interventions anchored in community participation can sustain impact under chronic crisis (Rockowitz et al.). Taken together, these contributions argue that capacity building is most effective when it is open, dialogic, culturally embedded, and infrastructural, producing two-way change in which both academic teams and community partners gain new capabilities.

Strategic partnerships and resource mobilization: restructuring power and participation

Effective science diplomacy also depends on who convenes and who controls resources. Several studies highlight models that de-center extractive funding and institutionalize shared leadership. The EMT hub in Addis Ababa represents a sustained, multi-actor training platform rooted in the region (Oyugi et al.). A comparative analysis of climate–health strategies in Saudi Arabia and Lebanon demonstrates how different political economies and funding ecosystems shape adaptation priorities (Al Khatib et al.). The Jordan “We Love Reading” initiative shows how participatory systems mapping can reveal empowerment pathways among refugees and host communities, demonstrating that community–academy partnerships can inform public policy (Dajani et al.). Research on infertility in Sudan demonstrates how adapting tools such as FertiQoL to cultural realities strengthens the case for investment in infertility care, linking measurement choices to resource mobilization (Bayoumi et al.). The perspective piece by Dajani et al. broadens this argument, calling for grassroots-driven and reflexive partnerships that resist tokenistic collaborations (Dajani et al.). Together, these contributions suggest that equitable diplomacy requires multi-year partnerships with co-leadership clauses, financing tied to community-defined metrics, and investment in platforms such as regional hubs rather than isolated projects.

Design, implementation, and impact assessment: operationalizing equity and accountability

Assessment frameworks are most meaningful when they measure what communities value. Several articles illustrate how to embed accountability and equity into design and evaluation. A participatory systems mapping study in Jordan used Fuzzy Cognitive Mapping with Syrian refugees and Jordanian women to generate causal models of empowerment that are owned by the community and can be simulated for policy scenarios (Dajani et al.). Research on FertiQoL in Sudan shows that cognitive interviewing and cultural adaptation challenge universalizing measures that miss local lived experience (Bayoumi et al.). A study from Ethiopia quantifies socioeconomic gradients in access to quality care (Tsega et al.), while population-level research in the UAE links cumulative childhood adversity to adult mental health, highlighting the importance of early identification and trauma-informed systems (Murphy et al.). The Tarkiz program in Gaza provides an example of community-defined success criteria evolving over 15 years (Rockowitz et al.), while a network meta-analysis of Traditional Chinese Exercises illustrates how evidence synthesis can elevate non-Western practices into global discourse (Feng et al.). Across these cases, the message is clear: equity requires co-created theories of change, cultural validation protocols before cross-setting use of measures, and transparent reporting of authorship balance, principal investigator location, and data stewardship. It also requires closing practice-to-policy loops so that feedback from service delivery informs curricula and national guidelines. Future work should collate such models dynamically, producing flexible frameworks that allow lessons learned in one context to be adapted across others.

Conclusion

This Research Topic advances a pragmatic agenda for equitable science diplomacy, emphasizing representative governance, reciprocal capacity ecosystems, co-led and shock-resilient financing, and equity-first impact assessment. Across diverse contexts, the studies demonstrate that shifting from extractive ties to shared authority is feasible when participation is specified, cultural validity is designed in, and resources are stabilized. Looking forward, three priorities stand out: funders should require co-governance structures and equity audits, ministries should invest in regional platforms that link training to service change, and journals and consortia should adopt standardized equity metrics in reporting. Done this way, science diplomacy becomes not an instrument of soft power but a practice of shared power in service of global public health equity.

Author contributions

RB: Conceptualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. TB: Conceptualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. AA: Writing – review & editing. RD: Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The author(s) declare that no Gen AI was used in the creation of this manuscript.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Publisher's note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

1. Polejack A, Goveas J, Robinson S, Flink T, Ferreira G. Where is the Global South in the Science Diplomacy Narrative? SSRN (2022). Available online at: https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=4278557 (Accessed November 16, 2022).

Keywords: science diplomacy, public health, global south, equity, governance, capacity building, strategic partnerships

Citation: Bayoumi R, Bosqui T, Awad A and Dajani R (2025) Editorial: Science diplomacy and neocolonialism: lessons from the field with a view to the future. Front. Public Health 13:1700272. doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2025.1700272

Received: 06 September 2025; Accepted: 15 September 2025;

Published: 09 October 2025.

Edited and reviewed by: Christiane Stock, Charité - Universitätsmedizin Berlin, Corporate Member of Freie Universität Berlin and Humboldt-Universität zu Berlin, Germany

Copyright © 2025 Bayoumi, Bosqui, Awad and Dajani. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Rasha Bayoumi, ci5iYXlvdW1pQGJoYW0uYWMudWs=

Rasha Bayoumi

Rasha Bayoumi Tania Bosqui

Tania Bosqui Abdullah Awad

Abdullah Awad Rana Dajani

Rana Dajani