- Department of Gerontology, Shanghai Sixth People's Hospital, Shanghai Jiao Tong University School of Medicine, Shanghai, China

Introduction: The multimorbidity underlying in cognitive frailty remain poorly understood.

Methods: A cross-sectional study was performed in non-dementia Chinese aged over 50 years, Cognitive frailty (cognitive impairment and slow gait [SG]). Cardiovascular and cerebrovascular diseases (CCVD) (heart disease, type 2 diabetes, hypertension, hyperlipidemia and cerebral infarction). Continuous variables were evaluated using one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA). Categorical variables were assessed using the chi-square test. Pairwise comparisons were performed using the Bonferroni-corrected column proportion test (z-test). Multiple logistic regression analysis was conducted to identify factors associated with cognitive frailty.

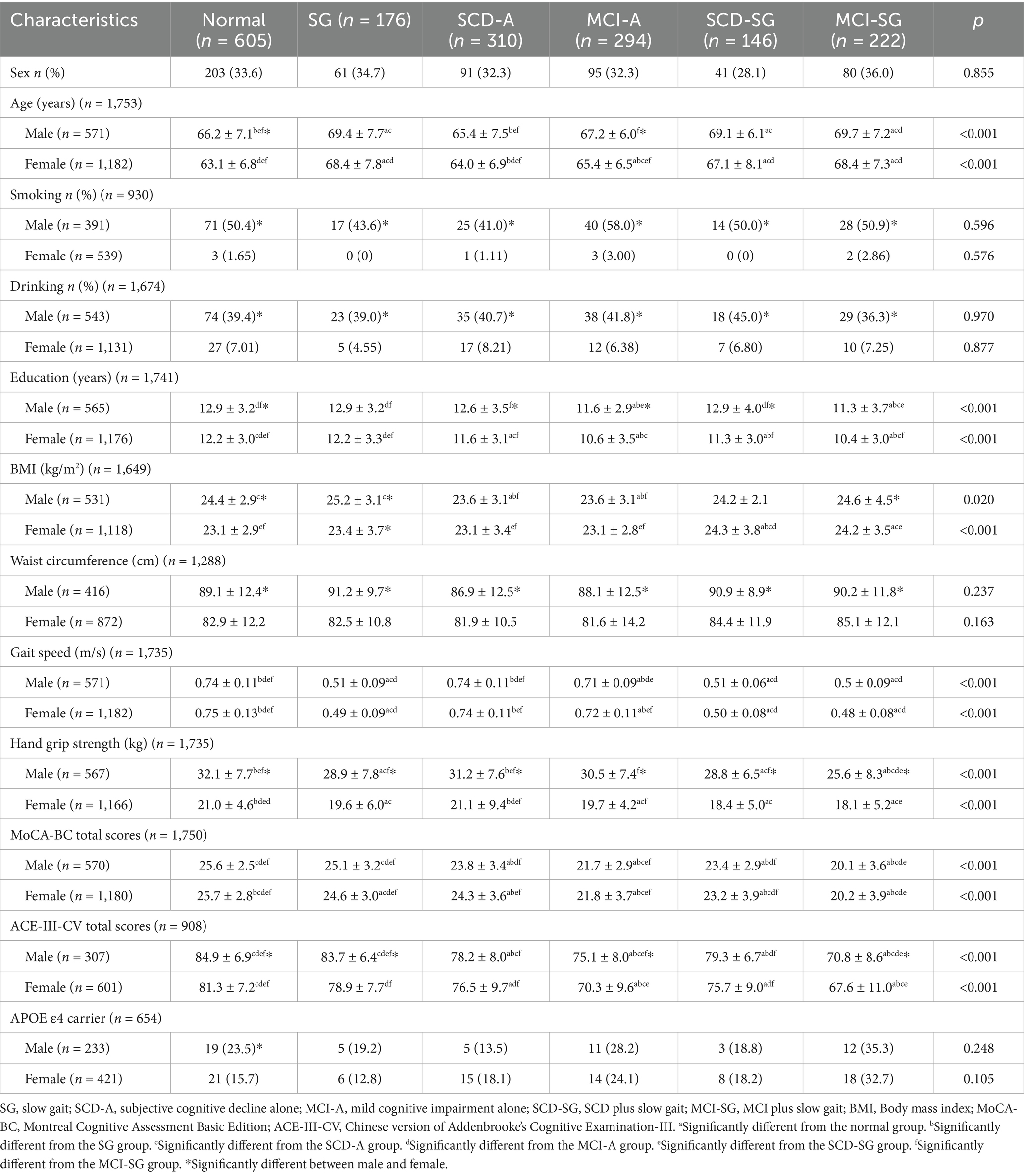

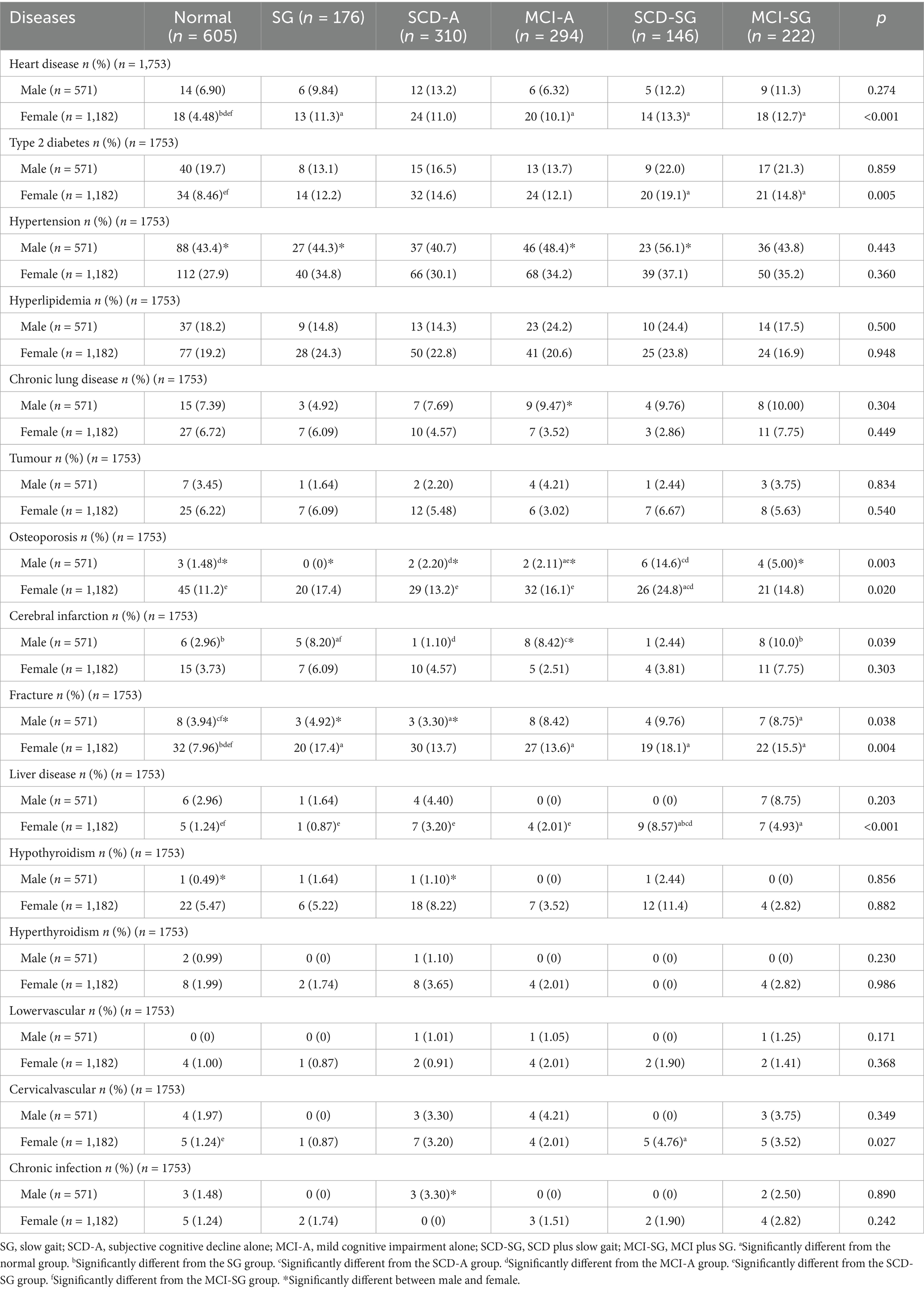

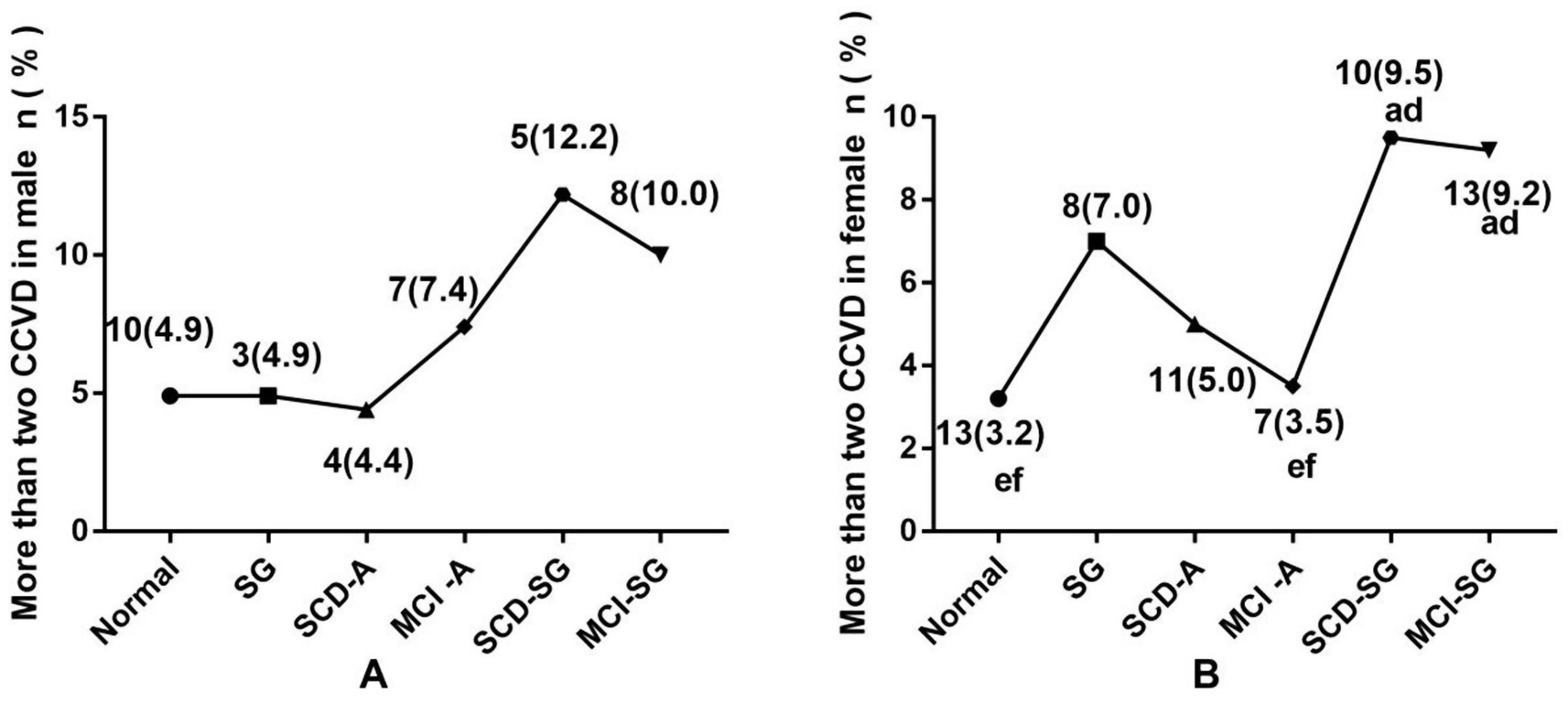

Results: A cross-sectional study included 571 males and 1,182 non-demented Chinese aged ≥50 years, categorized into 6 groups: normal, SG, subjective cognitive decline alone (SCD-A), mild cognitive impairment alone (MCI-A), subjective cognitive decline with slow gait (SCD-SG), and mild cognitive impairment with slow gait (MCI-SG). Cognitive frailty was defined as cognitive impairment plus SG. Walking speed and hand grip strength were lower in SG, SCD-SG, and MCI-SG groups (p < 0.05). SCD-SG and MCI-SG groups had higher prevalence of ≥3 chronic conditions (p < 0.05); SCD-SG and MCI-SG groups showed higher ≥3 CCVD (9.5, 9.2%; p < 0.05) in female. SCD-SG group had higher risk of 1–2 chronic conditions (OR = 1.81, 95%CI = 1.06–3.07) and ≥3 chronic conditions (OR = 3.79, 95%CI = 1.96–7.36).

Conclusion: Cognitive frailty in Chinese aged ≥50 years increases risk of ≥3 chronic diseases, with SCD-SG group at highest risk, highlighting the need for attention to cognitive frailty and multimorbidity.

Introduction

The aging global population has led to a rising prevalence of aging-related disorders. Alzheimer’s disease (AD), osteoarthritis, and cardiovascular and cerebrovascular diseases (CCVD), including type 2 diabetes, atherosclerosis, and hypertension, are significant age-related conditions (1). While these diseases are closely linked, the association between the pre-AD stage and these chronic disorders remains incompletely understood. Accumulating evidence highlights that cognitive and physical impairments in late life are interrelated through shared pathophysiological mechanisms and may represent a unified complex phenotype (2). Importantly, gait disorders and cognitive decline, which progress with aging, are regarded as primary risk factors for falls in older dementia patients (3, 4). The presence of both slow gait (SG) and objective cognitive impairment was linked to the highest risk of developing dementia and is considered the phenotype of cognitive frailty most susceptible to dementia progression (5).

Slow gait (SG) is recognized as an early symptom of dementia, and its severity worsens with disease progression compared to healthy older adults (6). Subjective cognitive decline (SCD) and mild cognitive impairment (MCI) are early manifestations of AD (7): SCD is characterized by a subjective perception of memory decline or mild objective neurocognitive impairment, while MCI represents a transitional stage between normal aging and mild dementia, with cognitive deficits that do not significantly impact daily functioning. Previous studies have shown that the co-occurrence of MCI and SG is associated with a higher risk of dementia and disability than either condition alone (8, 9). According to the consensus by the International Academy on Nutrition and Aging and the International Association of Gerontology and Geriatrics, cognitive frailty is defined by reduced cognitive reserve and motor decline (10), and research in this field has increasingly focused on motor decline and gait variables due to the critical role of motor function in the interplay between cognitive performance, cognitive impairment, and physical frailty (10). Notably, individual components of frailty have been linked to specific cognitive domains: slow gait is associated with executive function, attention, processing speed (11), word recall, and logical memory (12); weak grip predicts changes in executive function (12); and physical activity correlates with changes in executive function and word recall (12). However, among these factors, only motor performance has had its validity and reliability formally established in previous research (13, 14). Building on these findings, we defined cognitive frailty as the coexistence of cognitive decline and slow gait in the present study (5), a concept that holds significant clinical and research potential for better stratifying the risk of dementia and functional disabilities in older adults (15).

Slow gait serves as a key objective marker of this defined cognitive frailty. Understanding the prevalence of age-related diseases in individuals with cognitive frailty could facilitate early detection and intervention for AD and other age-related conditions, thereby alleviating the substantial burden on healthcare and long-term care systems. Cognitive frailty itself has also been associated with disability and death (16), though the heterogeneity of objective frailty assessment tools has led to inconsistent reliability evaluations of cognitive frailty across studies. Additionally, the limited reliability and inherent variability in the operational metrics of the Cardiovascular Health Study frailty criteria further hinder the establishment of a standardized definition for cognitive frailty. Despite these considerations, few studies have comprehensively explored multimorbidity in cognitive frailty—particularly in the specific subgroups of cognitive decline combined with slow gait, namely SCD plus SG (SCD-SG) and MCI plus SG (MCI-SG).

Therefore, our study aimed to investigate the patterns of multimorbidity in cognitive frailty that consists of cognitive decline and slow gait among Chinese non-dementia adults aged over 50 years. A major strength of this article lies in the combination of cognitive function severity levels and gait speed.

Methods

Study population

Between January 2019 and June 2023, 3,034 participants were enrolled from the Department of Geriatrics at Shanghai Sixth People’s Hospital. Trained staff conducted neuropsychological tests for all participants in a standardized neuropsychological assessment room. Exclusion criteria included: (1) age under 50 years (n = 303); (2) diagnosis of dementia based on the American Psychiatric Association’s Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 4th edition (DSM-IV) (n = 645); (3) a history of psychological disorders (n = 32); and (4) individuals with physical disabilities who were unable to provide gait speed measurements or unavailable gait speed records (n = 301). After applying these criteria, 1,753 participants were included in the final analysis. The study protocol was approved by the Ethics Committee of Shanghai Sixth People’s Hospital (approval number: 2019–041), and all participants provided written informed consent in compliance with the Helsinki Declaration.

Measurements at baseline

Patients’ demographic characteristics, chronic diseases, medical history, and lifestyle factors—including age, sex, smoking and drinking status, heart disease, hypertension, type 2 diabetes, osteoporosis, cerebral infarction, fracture, and cirrhosis—were verified through medical record reviews by experienced clinicians. Heart disease included a history of coronary artery disease and arrhythmia, while chronic lung disease encompassed chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and chronic bronchitis. Cerebral infarction was diagnosed based on a history of ischemic events confirmed by brain CT or MRI scans. Body mass index (BMI, kg/m2) was calculated as weight (kg) divided by height squared (m2). Hand grip strength (kg) was assessed using a dynamometer (WCS-100, Nantong, China).

The SCD group included individuals who reported subjective cognitive decline without objective neuropsychological test abnormalities, as well as those with detectable cognitive changes using sensitive neuropsychological measures during the preclinical stage of AD. MCI inclusion criteria were adapted from Petersen RC’s guidelines: (1) cognitive complaints reported by the participant, informant, nurse, or physician within the past year; (2) normal cognitive function (Montreal Cognitive Assessment Basic Edition [MoCA-BC] scores: primary school 19–14, secondary school 22–16, university and above 24–17); (3) objective cognitive impairment, defined as performance at least 1.5 SD below age- and education-adjusted norms on standardized neuropsychological tests; (4) minimal impairment in daily living activities, with no more than one item significantly affected on the Chinese version of the Activities of Daily Living Scale (ADLs) or a total score < 26 (17); and (5) no diagnosis of dementia (18, 19). Gait speed was assessed using the timed up-and-go test over a 6-meter distance. The threshold for gait speed varies in the literature. Merchant RA et al. defined SG as <1 m/s (20), while other studies proposed thresholds of <0.6 m/s (21, 22) or <0.8 m/s (23) to identify individuals at higher risk of poor health outcomes. In our study, to ensure a rigorous analysis across age groups, we first focused on participants aged 50–59 years and defined SG as a gait speed below 0.6 m/s.

The participants in this study were divided into six groups: the normal group, the SG group, the subjective cognitive decline alone (SCD-A) group, the mild cognitive impairment alone (MCI-A) group, the group with concurrent SCD and SG (SCD-SG), and the group with concurrent MCI and SG (MCI-SG) group. The “cognitive frailty groups” are characterized by concurrent cognitive decline and SG, corresponding specifically to the SCD-SG group and the MCI-SG group.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analyses were carried out using SAS version 9.4 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC). Continuous variables, such as age, education level, hand grip strength, gait speed, and neuropsychological test scores, were reported as mean ± standard deviation (SD). Differences among groups for continuous variables were evaluated using one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA). For categorical variables, including gender, smoking status, alcohol consumption status, and the prevalence of chronic diseases, group differences were assessed using the chi-square test. Pairwise comparisons were performed using the Bonferroni-corrected column proportion test (z-test). Multiple logistic regression analysis was conducted to identify factors associated with MCI-SG and SCD-SG. A p-value < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. Figures were prepared using GraphPad Prism version 9.

Results

Demographic and clinical characteristics

A total of 1,753 participants (571 males and 1,182 females) were divided into six groups: normal, SG, SCD-A, MCI-A, SCD-SG, and MCI-SG. Each group was further stratified by gender to explore potential gender-specific differences in demographic and clinical characteristics.

Gender and group distribution

Females accounted for 67.4% of the total participants, with no significant difference in gender distribution across the six groups (p = 0.855). The proportion of participants in each group was as follows: normal group (34.5%), SG group (10.0%), SCD-A group (17.7%), MCI-A group (16.8%), SCD-SG group (8.3%), and MCI-SG group (12.7%).

Age

In the female subgroup, participants in the SG (68.4 ± 7.8 years), SCD-SG (67.1 ± 8.1 years), and MCI-SG (68.4 ± 7.3 years) groups were significantly older than those in the normal, SCD-A, and MCI-A groups (p < 0.05). A similar age trend was observed in the male subgroup, with the SG (69.4 ± 7.7 years), SCD-SG (69.1 ± 6.1 years), and MCI-SG (69.7 ± 7.2 years) groups being significantly older than the other three groups (p < 0.05).

Lifestyle and anthropometric indicators

Smoking status, alcohol consumption, and waist circumference showed no significant differences across the six groups, regardless of gender. Regarding BMI, the SG group had a higher BMI in males, while the SCD-SG (24.3 ± 3.8 kg/m2) and MCI-SG (24.2 ± 3.5 kg/m2) groups had higher BMI in females (p < 0.05).

Physical function

Regardless of gender, walking speed was significantly slower in the SG (males: 0.51 ± 0.09 m/s; females: 0.49 ± 0.09 m/s), SCD-SG (males: 0.51 ± 0.06 m/s; females: 0.50 ± 0.08 m/s), and MCI-SG (males: 0.50 ± 0.09 m/s; females: 0.48 ± 0.08 m/s) groups compared to the normal, SCD-A, and MCI-A groups (p < 0.05). A similar trend was observed for hand grip strength across the six groups (p < 0.05).

Education level and cognitive function

The MCI-SG (males: 11.3 ± 3.7 years; females: 10.4 ± 3.0 years) and MCI-A (males: 11.6 ± 2.9 years; females: 10.6 ± 3.5 years) groups had significantly lower years of education than the other four groups (p < 0.05). For cognitive function (assessed using the MoCA-BC and Chinese version of Addenbrooke’s Cognitive Examination-III (ACE-III-CV) total scores), the MCI-SG and MCI-A groups had the lowest scores, followed by the SCD-SG group (all p < 0.05).

APOEε4 carrier status and gender-related differences

There was no significant difference in APOEε4 carrier status between males and females, indicating that gender may not affect APOEε4 carrier status and thus eliminating potential sample interference from higher cognitive risk associated with more APOEε4 carriers in either gender. Additionally, some groups showed significant gender differences in age, smoking status, alcohol consumption, years of education, BMI, waist circumference, hand grip strength, and MoCA-BC scores.

All demographic and clinical characteristic data are summarized in Table 1.

The difference prevalence of chronic conditions and CCVD among normal, SG, SCD-A, MCI-A, SCD-SG and MCI-SG groups

Figure 1A displayed the prevalence of chronic conditions, categorized by the number of conditions (none, one or two, and more than two) across six groups. In males, the SCD-SG group (22.0%) and MCI-SG group (18.8%) had a significantly higher prevalence of more than two chronic conditions compared to the normal group (p < 0.05). No significant differences were observed for none or one to two chronic conditions. Among females, the proportion of participants with no chronic conditions was highest in the normal group and lowest in the SCD-SG group (36.3% vs. 14.3%, p < 0.05). In contrast, the prevalence of more than two chronic conditions was significantly higher in the SCD-SG group (25.7%) and MCI-SG group (19.7%) compared to the normal group (10.5%, p < 0.05).

Figure 1. (A) The difference prevalence of no chronic conditions among six groups in male. (B) The difference prevalence of one or two chronic conditions among six groups in male. (C) The difference prevalence of more than two chronic conditions among six groups in male. (D) The difference prevalence of no chronic conditions among six groups in female. (E) The difference prevalence of one or two chronic conditions among six groups in female. (F) The difference prevalence of more than two chronic conditions among six groups in female. aSignificantly different from the normal group. bSignificantly different from the SG group. cSignificantly different from the SCD-A group. dSignificantly different from the MCI-A group. eSignificantly different from the SCD-SG group. fSignificantly different from the MCI-SG group.

Cardiovascular and cerebrovascular diseases (CCVD), encompassing heart disease, type 2 diabetes, hypertension, hyperlipidemia, and cerebral infarction, were also analyzed. The prevalence of more than two CCVD was significantly higher in the SCD-SG group (9.5%) and MCI-SG group (9.2%) among females (p < 0.05). A similar trend was observed in males, though the differences were not statistically significant (Figure 2A).

Figure 2. (A) The difference prevalence of more than two CCVD among six groups in male. (B) The difference prevalence of more than two CCVD among six groups in female. CCVD, Cardiovascular and cerebrovascular diseases. aSignificantly different from the normal group. bSignificantly different from the SG group. cSignificantly different from the SCD-A group. dSignificantly different from the MCI-A group. eSignificantly different from the SCD-SG group. fSignificantly different from the MCI-SG group.

Chronic conditions among normal, SG, SCD-A, MCI-A, SCD-SG and MCI-SG groups

We demonstrated that the prevalence of osteoporosis, cerebral infarction, and fracture varied significantly among the six male subgroups (p < 0.05). Osteoporosis prevalence was elevated in the SCD-SG and MCI-SG groups, while cerebral infarction and fracture rates were highest in the MCI-SG group. In females, significant differences were observed in the prevalence of heart disease, type 2 diabetes, osteoporosis, fracture, liver cirrhosis, and cervical vascular disease across groups (p < 0.05), with the SCD-SG and MCI-SG groups showing the highest prevalence of these conditions (Table 2).

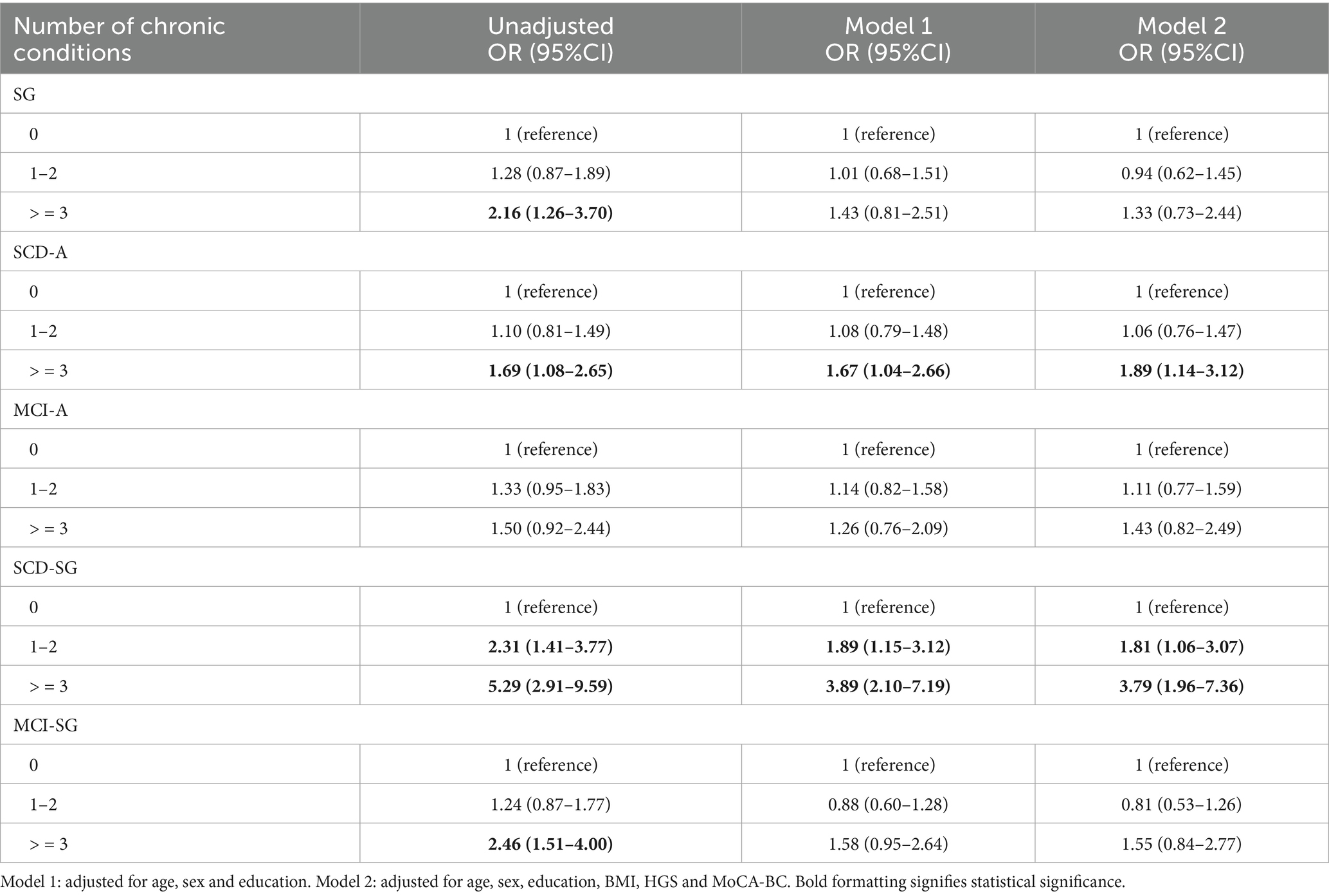

Odd ratios (ORs) and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) for the associations of the number of chronic conditions with risk of SG, SCD-A, MCI-A, SCD-SG and MCI-SG

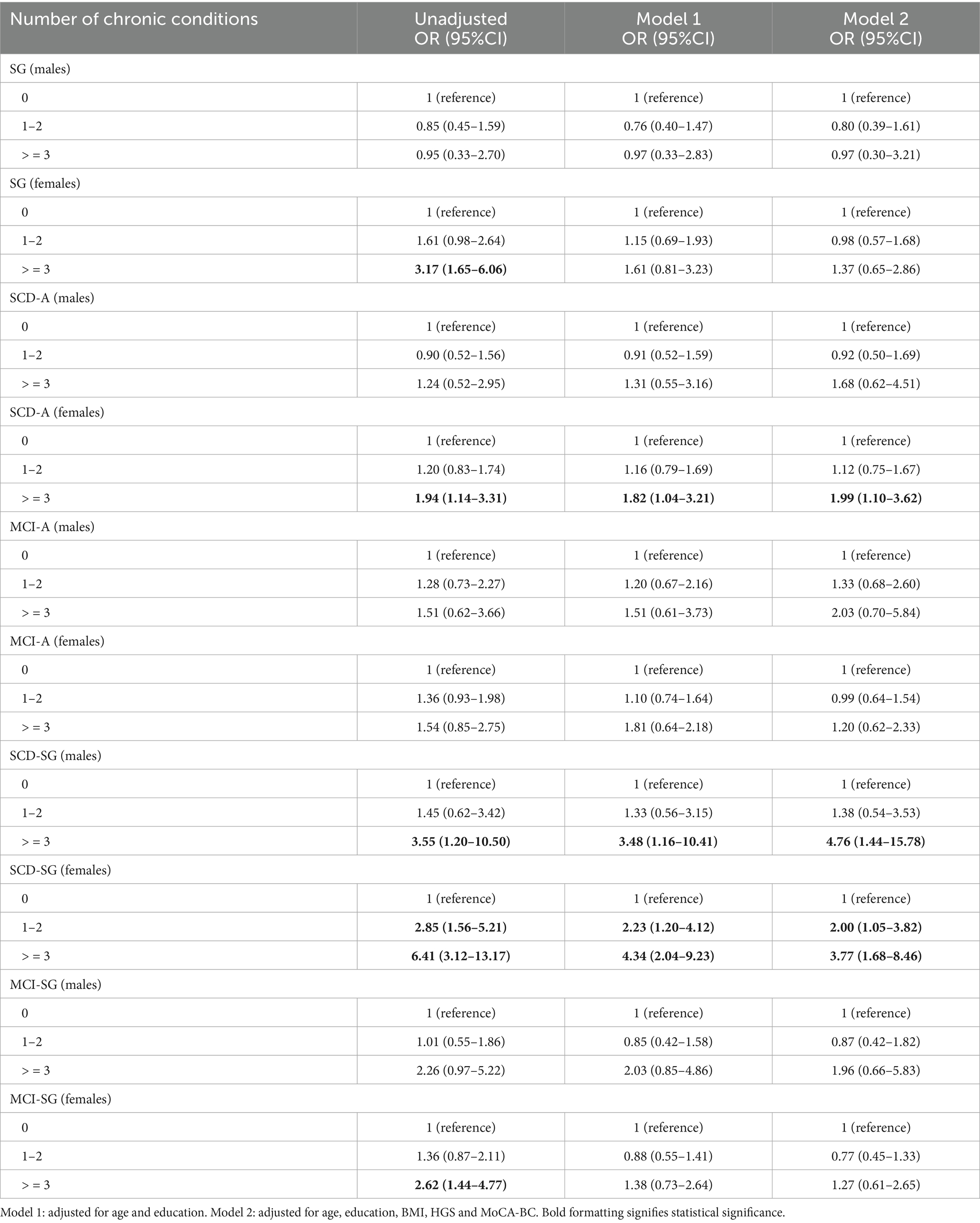

In all participants, when adjusted for age, gender, education, BMI, HGS, and MoCA-BC, compared to the normal group, it was found that the SCD-A group had a greater risk of developing at least two chronic conditions (OR = 1.89, 95% CI: 1.14–3.12), whereas the SCD-SG group had a 2.79 times higher risk of developing more than two chronic conditions (Table 3).

Table 3. Odd ratios (ORs) and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) for the associations of the number of chronic conditions with risk of SG, SCD-A, MCI-A, SCD-SG and MCI-SG.

In males, it was found that the SCD-A group had a greater risk of developing more than two chronic conditions (OR = 4.76, 95% CI: 1.44–15.78) (Table 4).

Table 4. Odd ratios (ORs) and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) for the associations of the number of chronic conditions with risk of SG, SCD-A, MCI-A, SCD-SG and MCI-SG in males and females.

In females,it was found that the SCD-A group had a greater risk of developing more than two chronic conditions (OR = 1.99, 95% CI: 1.10–3.62); the SCD-SG group had a 1.00 time higher risk of developing one or two chronic conditions, 2.77 times higher risk of developing more than two chronic conditions (Table 4).

Discussion

Over 20% of the older adults in our study exhibited cognitive frailty, characterized by the coexistence of cognitive decline and SG, along with multiple chronic conditions. Notably, Chinese adults aged over 50 years with subjective cognitive decline (SCD) accompanied by SG were more likely to have more than two chronic conditions. This study is the first to systematically investigate the relationship between cognitive frailty, SG, and multimorbidity in non-dementia Chinese adults aged over 50 years.

Cognitive frailty is considered a reversible condition (2), making it an ideal target for preventing asymptomatic preclinical cognitive impairment. We divided cognitive frailty into SCD-SG and mild MCI-SG and revealed differences in chronic disease burden among these phenotypes. We found that individuals with SCD-SG had a significantly higher risk of developing two or more chronic conditions whether in males or females. Growing evidence suggests that interventions, particularly physical activity, are effective in reducing cognitive decline and preventing negative health outcomes (10).

Our study focused on multimorbidity in cognitive frailty, which is the integration of cognitive function severity and gait speed, enabling comprehensive characterization of cognitive frailty. We observed osteoporosis was more prevalent in both genders with concurrent cognitive decline and slow gait (SG), with females at higher risk. Certain age-related metabolic diseases were also more common in women, potentially driven by genetic and hormonal factors. These findings align with prior research reporting elevated burdens of age-related conditions, such as type 2 diabetes, cerebral infarction, heart disease, fractures in individuals with SCD and SG (24, 25). Notably, we detail individual comorbidities instead of relying on aggregate indices like the Charlson Comorbidity Index. This granular approach revealed hypertension, hyperlipidemia, chronic lung disease, tumors, thyroid disorders, and chronic infections were not highly prevalent in our cognitive frailty cohorts—differing from studies that found no significant differences in common metabolic or endocrine conditions across SCD, MCI, and AD groups (26–28). These observations support cognitive frailty’s potential reversibility in preclinical stages: modifiable comorbidities, such as osteoporosis, age-related metabolic diseases identified here are actionable intervention targets. Targeting osteoporosis via lifestyle or pharmacological strategies, for instance, may mitigate cognitive frailty progression, supporting early intervention feasibility. Alignment with prior evidence (24, 25) reinforces addressing multimorbidity in early cognitive frailty, while our distinct profile underscores the need for larger longitudinal studies to refine intervention frameworks.

The association between CCVD and SG, SCD, or cognitive frailty is well supported by prior research, but our study advances this understanding by focusing on their co-occurrence in SCD-SG, MCI-SG. Notably, while the rising prevalence and mortality of cardiovascular disease (CVD) in China underscore the clinical relevance of these links (29), prior work—including a recent study (Lv J, Huang F, Shi Y. Association between multimorbidity and cognitive frailty among the older adults in China: the mediating effect of depressive symptoms. Exp Gerontol. 2025;210:112864. doi:10.1016/j.exger.2025.112864) has primarily focused on aggregate multimorbidity burden or isolated cognitive or gait outcomes rather than their combined presentation in preclinical stages.

Some studies reported that cardiovascular and metabolic multimorbidity correlates with incident cognitive frailty in older adults, emphasizing shared inflammatory pathways (Aprahamian I, Mamoni RL, Cervigne NK, et al. Design and protocol of the multimorbidity and mental health cohort study in frailty and aging (MiMiCS-FRAIL): unraveling the clinical and molecular associations between frailty, somatic disease burden and late life depression. BMC Psychiatry. 2020;20 (1):573. Published 2020 Dec 1. doi:10.1186/s12888-020-02963-9; Grande G, Marengoni A, Vetrano DL, et al. Multimorbidity burden and dementia risk in older adults: The role of inflammation and genetics. Alzheimers Dement. 2021;17 (5):768–776. doi:10.1002/alz.12237). Our findings align with this mechanistic framework: elevated IL-6 and C-reactive protein have been linked to SG (30), reduced gray matter and hippocampal volume (31, 32)—structures critical for cognition and gait regulation—and subsequent cognitive decline (33). However, we extend this work by demonstrating that these inflammatory pathways also intersect with gender-specific comorbidities in preclinical AD subgroups, a gap not addressed in prior research.

A key novel finding of our study is the higher incidence of liver cirrhosis in females with coexisting cognitive decline and SG—an association rarely reported in cognitive-gait comorbidity research. This may stem from gender-specific metabolic alterations, hormonal fluctuations, malabsorption, or age-related muscle strength decline (34), all of which interact with inflammatory pathways highlighted in the Experimental Gerontology study. Additionally, our observation of poor handgrip strength (a core frailty marker) in SCD-SG and MCI-SG subgroups reinforces prior links between IL-6, reduced muscle mass, and cognitive impairment (35, 36), but contextualizes this within preclinical AD—where intervention potential is greatest. Together, these findings refine the multimorbidity profile of cognitive decline and SG, distinguishing our work from prior aggregate analyses and highlighting novel targets for early intervention. Larger longitudinal studies are needed to confirm these gender-specific associations and explore causal relationships.

However, the present study has several limitations that should be acknowledged. First, data on certain chronic conditions—such as fatty liver disease—were not comprehensively collected. This may have led to underrepresentation of the true burden of multimorbidity in the study population, potentially introducing bias into the analysis of associations between chronic diseases and cognitive outcomes. Second, the relatively small sample size of male participants constrained the statistical power of gender-stratified analyses. As a result, we may have been unable to detect subtle associations between chronic conditions and cognitive decline that are specific to males, limiting the generalizability of our gender-specific findings. Finally, the cross-sectional nature of the study design precluded us from establishing directional or causal relationships between chronic diseases and cognitive decline. It remains unclear whether chronic conditions precede and contribute to cognitive decline, or if early cognitive impairment increases the risk of developing chronic diseases, or if both are driven by shared underlying factors, such as chronic inflammation, aging-related biological pathways.

Conclusion

The prevalence of more than two chronic conditions was significantly higher in individuals with cognitive frailty, particularly those with SCD and SG. This indicates that the combination of cognitive decline and SG may be a critical marker for identifying individuals at risk of multimorbidity and serves as a critical marker for identifying high-risk groups, guiding middle-aged/older adults screening in communities and clinics. Additionally, osteoporosis, fractures, and the presence of more than two CCVD were more frequently observed in individuals with cognitive frailty. We recommend that walking speed and subjective cognition be closely monitored in adults over 50 years of age. Interventions aimed at strengthening physical exercise and improving walking speed may not only prevent AD but also mitigate chronic conditions.

Data availability statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/supplementary material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author/s.

Ethics statement

The studies involving humans were approved by Ethics Committee of the Sixth People’s Hospital of Shanghai. The studies were conducted in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. The participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study.

Author contributions

JZ: Writing – original draft. CR: Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. TH: Investigation, Writing – original draft. JJ: Data curation, Supervision, Writing – original draft. QG: Supervision, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declare that financial support was received for the research and/or publication of this article. This study was funded by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (82171198), Shanghai Municipal Science and Technology Major Project (2018SHZDZX01), and Shanghai Municipal Health Commission (202340173).

Acknowledgments

We thank all participants who participated in this study.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The author(s) declare that no Gen AI was used in the creation of this manuscript.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

1. Fan, R, Peng, X, Xie, L, Dong, K, Ma, D, Xu, W, et al. Importance of Bmal1 in Alzheimer’s disease and associated aging-related diseases: mechanisms and interventions. Aging Cell. (2022) 21:e13704. doi: 10.1111/acel.13704

2. Panza, F, Seripa, D, Solfrizzi, V, Tortelli, R, Greco, A, Pilotto, A, et al. Targeting cognitive frailty: clinical and neurobiological roadmap for a single complex phenotype. J Alzheimer's Dis. (2015) 47:793–813. doi: 10.3233/JAD-150358

3. Cohen, JA, Verghese, J, and Zwerling, JL. Cognition and gait in older people. Maturitas. (2016) 93:73–7. doi: 10.1016/j.maturitas.2016.05.005

4. Zhang, W, Low, L-F, Schwenk, M, Mills, N, Gwynn, JD, and Clemson, L. Review of gait, cognition, and fall risks with implications for fall prevention in older adults with dementia. Dement Geriatr Cogn Disord. (2019) 48:17–29. doi: 10.1159/000504340

5. Montero-Odasso, MM, Barnes, B, Speechley, M, Muir Hunter, SW, Doherty, TJ, Duque, G, et al. Disentangling cognitive-frailty: results from the gait and brain study. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. (2016) 71:1476–82. doi: 10.1093/gerona/glw044

6. Kikkert, LHJ, Vuillerme, N, van Campen, JP, Hortobágyi, T, and Lamoth, CJ. Walking ability to predict future cognitive decline in old adults: a scoping review. Ageing Res Rev. (2016) 27:1–14. doi: 10.1016/j.arr.2016.02.001

7. Ge, H, Chen, S, Che, Z, Wu, H, Yang, X, Qiao, M, et al. rTMS regulates homotopic functional connectivity in the SCD and MCI patients. Front Neurosci. (2023) 17:1301926. doi: 10.3389/fnins.2023.1301926

8. Doi, T, Makizako, H, Tsutsumimoto, K, Hotta, R, Nakakubo, S, Makino, K, et al. Combined effects of mild cognitive impairment and slow gait on risk of dementia. Exp Gerontol. (2018) 110:146–50. doi: 10.1016/j.exger.2018.06.002

9. Doi, T, Shimada, H, Makizako, H, Tsutsumimoto, K, Hotta, R, Nakakubo, S, et al. Mild cognitive impairment, slow gait, and risk of disability: a prospective study. J Am Med Dir Assoc. (2015) 16:1082–6. doi: 10.1016/j.jamda.2015.07.007

10. Facal, D, Burgo, C, Spuch, C, Gaspar, P, and Campos-Magdaleno, M. Cognitive frailty: an update. Front Psychol. (2021) 12:813398. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2021.813398

11. Robertson, DA, Savva, GM, Coen, RF, and Kenny, R-A. Cognitive function in the prefrailty and frailty syndrome. J Am Geriatr Soc. (2014) 62:2118–24. doi: 10.1111/jgs.13111

12. McGough, EL, Cochrane, BB, Pike, KC, Logsdon, RG, McCurry, SM, and Teri, L. Dimensions of physical frailty and cognitive function in older adults with amnestic mild cognitive impairment. Ann Phys Rehabil Med. (2013) 56:329–41. doi: 10.1016/j.rehab.2013.02.005

13. Solfrizzi, V, Scafato, E, Frisardi, V, Seripa, D, Logroscino, G, Maggi, S, et al. Frailty syndrome and the risk of vascular dementia: the Italian longitudinal study on aging. Alzheimers Dement. (2013) 9:113–22. doi: 10.1016/j.jalz.2011.09.223

14. Sargent, L, and Brown, R. Assessing the current state of cognitive frailty: measurement properties. J Nutr Health Aging. (2017) 21:152–60. doi: 10.1007/s12603-016-0735-9

15. Nyunt, MSZ, Soh, CY, Gao, Q, Gwee, X, Ling, ASL, Lim, WS, et al. Characterisation of physical frailty and associated physical and functional impairments in mild cognitive impairment. Front Med (Lausanne). (2017) 4:230. doi: 10.3389/fmed.2017.00230

16. Aliberti, MJR, Cenzer, IS, Smith, AK, Lee, SJ, Yaffe, K, and Covinsky, KE. Assessing risk for adverse outcomes in older adults: the need to include both physical frailty and cognition. J Am Geriatr Soc. (2019) 67:477–83. doi: 10.1111/jgs.15683

17. Chen, P, Yu, ES, Zhang, M, Liu, WT, Hill, R, and Katzman, R. ADL dependence and medical conditions in Chinese older persons: a population-based survey in Shanghai, China. J Am Geriatr Soc. (1995) 43:378–83. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.1995.tb05811.x

18. Petersen, RC. Mild cognitive impairment as a diagnostic entity. J Intern Med. (2004) 256:183–94. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2796.2004.01388.x

19. Jack, CR, Bennett, DA, Blennow, K, Carrillo, MC, Dunn, B, Haeberlein, SB, et al. NIA-AA research framework: toward a biological definition of Alzheimer’s disease. Alzheimers Dement. (2018) 14:535–62. doi: 10.1016/j.jalz.2018.02.018

20. Merchant, RA, Chan, YH, Anbarasan, D, and Aprahamian, I. Association of Motoric Cognitive Risk Syndrome with sarcopenia and systemic inflammation in pre-frail older adults. Brain Sci. (2023) 13:936. doi: 10.3390/brainsci13060936

21. Cesari, M, Kritchevsky, SB, Penninx, BWHJ, Nicklas, BJ, Simonsick, EM, Newman, AB, et al. Prognostic value of usual gait speed in well-functioning older people--results from the health, aging and body composition study. J Am Geriatr Soc. (2005) 53:1675–80. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2005.53501.x

22. Studenski, S, Perera, S, Wallace, D, Chandler, JM, Duncan, PW, Rooney, E, et al. Physical performance measures in the clinical setting. J Am Geriatr Soc. (2003) 51:314–22. doi: 10.1046/j.1532-5415.2003.51104.x

23. Abellan van Kan, G, Rolland, Y, Andrieu, S, Bauer, J, Beauchet, O, Bonnefoy, M, et al. Gait speed at usual pace as a predictor of adverse outcomes in community-dwelling older people an international academy on nutrition and aging (IANA) task force. J Nutr Health Aging. (2009) 13:881–9. doi: 10.1007/s12603-009-0246-z

24. Sathyan, S, Wang, T, Ayers, E, and Verghese, J. Genetic basis of motoric cognitive risk syndrome in the health and retirement study. Neurology. (2019) 92:e1427–34. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0000000000007141

25. Beauchet, O, Sekhon, H, Schott, A-M, Rolland, Y, Muir-Hunter, S, Markle-Reid, M, et al. Motoric cognitive risk syndrome and risk for falls, their recurrence, and Postfall fractures: results from a prospective observational population-based cohort study. J Am Med Dir Assoc. (2019) 20:1268–73. doi: 10.1016/j.jamda.2019.04.021

26. Mank, A, Rijnhart, JJM, van Maurik, IS, Jönsson, L, Handels, R, Bakker, ED, et al. A longitudinal study on quality of life along the spectrum of Alzheimer’s disease. Alzheimer's Res Ther. (2022) 14:132. doi: 10.1186/s13195-022-01075-8

27. Chou, M-Y, Nishita, Y, Nakagawa, T, Tange, C, Tomida, M, Shimokata, H, et al. Role of gait speed and grip strength in predicting 10-year cognitive decline among community-dwelling older people. BMC Geriatr. (2019) 19:186. doi: 10.1186/s12877-019-1199-7

28. Pereira, ML, de Vasconcelos, THF, de Oliveira, AAR, Campagnolo, SB, Figueiredo, S d O, Guimarães, AFBC, et al. Memory complaints at primary care in a middle-income country: clinical and neuropsychological characterization. Dement Neuropsychol. (2021) 15:88–97. doi: 10.1590/1980-57642021dn15-010009

29. Hu, S-S. Epidemiology and current management of cardiovascular disease in China. J Geriatr Cardiol. (2024) 21:387–406. doi: 10.26599/1671-5411.2024.04.001

30. Ferrucci, L, Corsi, A, Lauretani, F, Bandinelli, S, Bartali, B, Taub, DD, et al. The origins of age-related proinflammatory state. Blood. (2005) 105:2294–9. doi: 10.1182/blood-2004-07-2599

31. Gu, Y, Vorburger, R, Scarmeas, N, Luchsinger, JA, Manly, JJ, Schupf, N, et al. Circulating inflammatory biomarkers in relation to brain structural measurements in a non-demented elderly population. Brain Behav Immun. (2017) 65:150–60. doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2017.04.022

32. Satizabal, CL, Zhu, YC, Mazoyer, B, Dufouil, C, and Tzourio, C. Circulating IL-6 and CRP are associated with MRI findings in the elderly: the 3C-Dijon study. Neurology. (2012) 78:720–7. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0b013e318248e50f

33. Semba, RD, Tian, Q, Carlson, MC, Xue, Q-L, and Ferrucci, L. Motoric cognitive risk syndrome: integration of two early harbingers of dementia in older adults. Ageing Res Rev. (2020) 58:101022. doi: 10.1016/j.arr.2020.101022

34. Nardelli, S, Gioia, S, Faccioli, J, Riggio, O, and Ridola, L. Sarcopenia and cognitive impairment in liver cirrhosis: a viewpoint on the clinical impact of minimal hepatic encephalopathy. World J Gastroenterol. (2019) 25:5257–65. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v25.i35.5257

35. Fritz, NE, McCarthy, CJ, and Adamo, DE. Handgrip strength as a means of monitoring progression of cognitive decline - a scoping review. Ageing Res Rev. (2017) 35:112–23. doi: 10.1016/j.arr.2017.01.004

36. Weaver, JD, Huang, M-H, Albert, M, Harris, T, Rowe, JW, and Seeman, TE. Interleukin-6 and risk of cognitive decline: MacArthur studies of successful aging. Neurology. (2002) 59:371–8. doi: 10.1212/WNL.59.3.371

Abbreviations

ACE-III-CV, Chinese version of Addenbrooke’s Cognitive Examination-III; AD, Alzheimer’s disease; ADL, Activities of Daily Living; ANOVA, One-way analysis of variance; APA, American Psychiatric Association; BMI, Body mass index; CCVD, Cardiovascular and cerebrovascular diseases; MCI, Mild cognitive impairment; MCI-A, Mild cognitive impairment but no slow gait; MCI-SG, Mild cognitive impairment plus slow gait; MoCA-BC, Montreal Cognitive Assessment Basic Edition; NIA-AA, National Institute on Aging and Alzheimer’s Association; SCD, Subjective cognitive decline; SCD-A, Subjective cognitive decline but no slow gait; SCD-SG, Subjective cognitive decline plus slow gait; SD, Standard deviations; SG, Slow gait.

Keywords: multimorbidity, slow gait, cognitive frailty, aged over 50 years, mild cognitive impairment

Citation: Zhu J, Ren C, Hu T, Jin J and Guo Q (2025) Multimorbidity patterns and cognitive frailty in adults aged over 50 years: China perspective. Front. Public Health. 13:1701955. doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2025.1701955

Edited by:

Selcuk Akpinar, Nevsehir University, TürkiyeReviewed by:

Mohammad Saiful Islam, Bangladesh Livestock Research Institue, BangladeshLalu Suprawesta, Mandalika Education University, Indonesia

Copyright © 2025 Zhu, Ren, Hu, Jin and Guo. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Qihao Guo, cWhndW9Ac2p0dS5lZHUuY24=; Jun Jin, amluanVuMjIyQHNqdHUuZWR1LmNu

†These authors have contributed equally to this work

Jiehua Zhu†

Jiehua Zhu† Chenxi Ren

Chenxi Ren Qihao Guo

Qihao Guo