- 1Department of Women's Health Care, Women and Children's Hospital of Ningbo University, Ningbo, Zhejiang, China

- 2Department of Child Health Care, Women and Children's Hospital of Ningbo University, Ningbo, Zhejiang, China

Objectives: Perinatal depression (PND) is a significant public health concern, particularly among those without local household registration. This study aims to investigate the association between China’s hukou status (household registration system) and PND, and to assess whether socioeconomic status (SES) modifies this relationship.

Methods: A prospective cohort study was conducted among 1,825 pregnant women at four maternal and child health hospitals in Ningbo, China, from January to December 2022. Depressive symptoms were assessed by the Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale (EPDS) during each trimester and postpartum. Socioeconomic status (SES) was assessed via a 0–5 composite score comprising educational level, household monthly income, and employment status. Generalized Estimating Equations (GEE) were used to evaluate the association between hukou status and PND (EPDS ≥ 9), and to examine potential effect modification by SES. All models were verified in parallel using logistic regression analyses. The robustness of the associations was examined in sensitivity analysis using alternative EPDS thresholds (≥10 and ≥13).

Results: In our study, local hukou status was significantly associated with a lower prevalence of PND compared with non-local hukou status (adjusted odds ratio [aOR] = 0.30, 95% CI: 0.22–0.42; p < 0.001), with the strongest protective effect observed in the second trimester (aOR = 0.28, 95% CI: 0.20–0.38). However, the interaction between hukou status and time was not statistically significant (p > 0.05). Interaction analyses between hukou status and SES further confirmed that the protective effect of local hukou was independent of SES (p > 0.05). Among the 1,825 pregnant women included, 345 (18.9%) held non-local hukou, and the prevalence of depression was 285 (15.62%), 237 (12.99%), 257 (14.08%), and 167 (9.15%) cases in the first, second, third trimesters, and postpartum period, respectively. Sensitivity analyses verified the robustness of all aforementioned findings.

Conclusion: China’s hukou status functions as an independent institutional determinant of PND risk, with its protective effect unmodified by individual socioeconomic resources. Addressing the hukou-based institutional inequities is essential for developing effective public health strategies and clinical interventions against PND.

1 Introduction

Perinatal depression (PND), encompassing both major and minor depressive episodes occurring during pregnancy or within the first year postpartum, is one of the most prevalent medical complications in the perinatal period. The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG) indicates that this condition affects approximately one in seven women during the period (1). While in China, relevant evidence highlights a comparable or slightly higher burden. For instance, a meta-analysis focusing on Chinese populations reported an overall PND prevalence of 16.3% (95% CI: 14.7–18.2%), with prenatal and postpartum rates reaching 19.7 and 14.8%, respectively (2). Globally, rural areas report a higher prevalence (22.1, 95% CI: 19.0–25.3%), and rates are further elevated in low- and lower-middle-income countries, at 24.5 and 22.8%, respectively (3). PND is a major public health issue with serious consequences for mothers and children. Depressed mothers face increased risks of obstetric complications, including preeclampsia (4) and gestational diabetes (5), with particularly heightened suicide risk (6, 7). Their infants are more likely to experience preterm birth (8), low birth weight, impaired growth, and psychomotor developmental delays (9). Beyond health impacts, PND also disrupts family relationships and creates economic burdens for households and society (10).

Beyond individual-level factors, perinatal mental health is profoundly shaped by structural social determinants. In China, the household registration (hukou) system institutionalizes such structural inequality by tying access to resources and opportunities to one’s registration locale (11, 12). This system classifies individuals as rural or urban residents, serving as a key socioeconomic indicator (13). The system aims to use administrative registration to anchor the population in specific geographic areas and restrict internal population movement (14). The hukou system can influence health outcomes through various pathways, including the allocation of medical resources and social security. In recent years, with economic development, the number of non-local workers in economically developed regions has increased. However, the actual social security and medical services they receive may fall below the standards enjoyed by local residents (13, 15, 16). Guo et al. found that both temporary and permanent non-local residents had significantly higher levels of depressive symptoms compared with urban local residents (14). Similarly, a nationwide survey by Qiu et al. revealed that non-local workers had a higher prevalence of depressive symptoms (23.7%), and the risk of depression was affected by socioeconomic status (SES) (17).

Existing studies have primarily identified several risk factors for PND, including premenstrual syndrome, violence exposure, unintended pregnancy (18), poor social support (19), low economic status of families, and low education level (20). However, few studies have explored the role of hukou status in PND in China, particularly its longitudinal effects across pregnancy stages. Moreover, higher SES (e.g., education, income) may buffer the adverse effects of disadvantaged hukou status by providing greater resources and coping strategies, whereas lower SES may compound these disadvantages. This potential interaction effect of SES in this relationship warrants further investigation.

In this study, we conducted a prospective cohort study in Ningbo, China, aimed to: (1) quantify the association between hukou status and perinatal depressive symptoms across pregnancy stages, adjusting for key confounders; and (2) assess whether SES modifies these associations. Our findings will provide new insights into the role of hukou status in PND and inform both clinical screening protocols and social policies mitigating health inequities among non-local mothers.

2 Methods

2.1 Study design and participants

This study recruited pregnant women who received first-trimester prenatal care (<14 weeks of gestation) at four maternal and child health hospitals in Ningbo, China, from January 1st to December 31st, 2022. A total of 2,000 eligible women were enrolled, with 500 participants per site, after providing written informed consent. Follow-up continued until two months postpartum.

Participants were included if they met all of the following criteria: (1) gestational age <14 weeks at enrollment; (2) singleton pregnancy; (3) willingness to complete baseline surveys and psychological assessments; (4) no prior diagnosis of psychiatric disorders; and (5) ability to comply with study protocols. Exclusion criteria included: (1) pre-existing neurological or brain disorders; (2) physical inability to complete self-administered questionnaires or psychological scales; or (3) high mobility or uncertain delivery location.

The study protocol was approved by the Medical Ethics Committee of Ningbo Women and Children’s Hospital (NBFE-2025-KY-134, renewed from EC2022-029). This study was conducted in accordance with the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki. All participants signed the informed consent form.

2.2 Data collection

All participants underwent initial depression screening using the Edinburgh postnatal depression scale (EPDS) and completed baseline questionnaires during the first trimester (<14 weeks). Follow-up EPDS assessments were conducted at three additional time points: the second trimester (14–27+6 weeks), the third trimester (≥28 weeks), and the postpartum period (42 days to 2 months after delivery). Demographic and socioeconomic characteristics, specifically age, education, income, employment, and marital status, were assessed solely at the first-trimester baseline. As these factors are generally stable over the relatively short perinatal period, they were not re-evaluated in follow-up visits. All Questionnaires were collected by trained interviewers. Among the 2,000 initially enrolled participants, 1,825 (91.3%) completed all follow-up assessments and were included in the final analysis.

2.3 Covariate

Covariates included maternal age, educational level (high school or below, college or above), only child status, marital status (married, divorced/unmarried), current employment status (unemployed, freelance, full-time employed), household monthly income (<10,000 RMB, 10,000–20,000 RMB, ≥20,000 RMB), gravidity (1, 2–4, ≥5 pregnancies), infectious disease history (including hepatitis B, syphilis, and HIV), pre-pregnancy BMI (<18.5 kg/m2 [underweight], 18.5–24 kg/m2 [normal weight], or ≥24 kg/m2 [overweight/obese]), and whether the current pregnancy was planned.

2.4 Definition of variables

Hukou status refers to China’s official household registration system, which legally ties individuals’ access to public services to their registered location (21). In our study, it was categorized as local and non-local. SES was determined through a composite scoring system incorporating three key variables: educational level, employment status, and household monthly income (22). Educational level was scored on a 0–1 scale (0 = high school or less, 1 = college degree or above), while household monthly income was scored 0–2 (0 = <10,000 RMB, 1 = 10,000–20,000 RMB, 2 = ≥20,000 RMB) and employment status was likewise scored 0–2 (0 = unemployed, 1 = freelance, 2 = full-time), yielding a total SES score ranging from 0 to 5. Based on this composite score, participants were categorized into two distinct groups: those with low SES (SES scores 0 to 2) and those with high SES (SES scores > 2). The detailed scoring criteria and point assignments for each variable are provided in Supplementary Table 1.

2.5 Measurement of depressive symptoms

The Edinburgh postnatal depression scale (EPDS) was employed to evaluate depressive symptoms in perinatal women and has been proven to be a useful tool for both prenatal and postpartum screening in the Chinese population (23). The scale consists of 10 items, with a total score ranging from 0 to 30; higher scores indicate more severe depressive symptoms. The Chinese version of EPDS has demonstrated high internal consistency (Cronbach’s alpha = 0.84) and reliability (split-half reliability coefficient = 0.74) (24). Additionally, it has a well-validated cutoff score of 9/10 for depression screening (25, 26). In our study, maternal EPDS scores ≥ 9 were considered the presence of depression symptoms (27–29).

2.6 Statistical analysis

In the current study, descriptive statistics were used to summarize the baseline characteristics of the study population. Continuous variables were compared using independent samples t-tests or one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA), while categorical variables were analyzed using Pearson’s χ2 tests or Fisher’s exact tests.

The association between hukou status and perinatal depressive symptoms (EPDS ≥ 9) was primarily assessed using Generalized Estimating Equations (GEE) to account for the longitudinal correlation of repeated measures across the four time points. All models adjusted for covariates, including maternal age, education, pre-pregnancy BMI, only child, hukou status, marital status, employment, household monthly income, gravidity, HIV, syphilis, hepatitis B, and other infectious diseases, and planned pregnancy. To evaluate potential effect modification by SES, an interaction term between hukou status and the composite SES score was included in the GEE model. To verify the robustness of our primary findings, we conducted complementary analyses using separate multivariable logistic regression models for each perinatal period (trimesters 1–3 and postpartum).

Furthermore, sensitivity analyses were performed by re-running both the GEE and logistic regression models using alternative EPDS cutoffs (≥ 10 and ≥ 13). For logistic regression models with low event rates (<5%), we implemented Firth’s logistic method to address potential small-sample bias. Before conducting the multivariable regression analyses, we performed Hosmer-Lemeshow goodness-of-fit tests and assessed multicollinearity using variance inflation factors (VIF) to ensure model fit and stability.

All statistical analyses were performed using R (version 4.4.3; R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria) and SAS (version 9.4; SAS Institute, Cary, NC). A two-tailed p-value <0.05 was considered statistically significant.

3 Results

3.1 Characteristics of participants

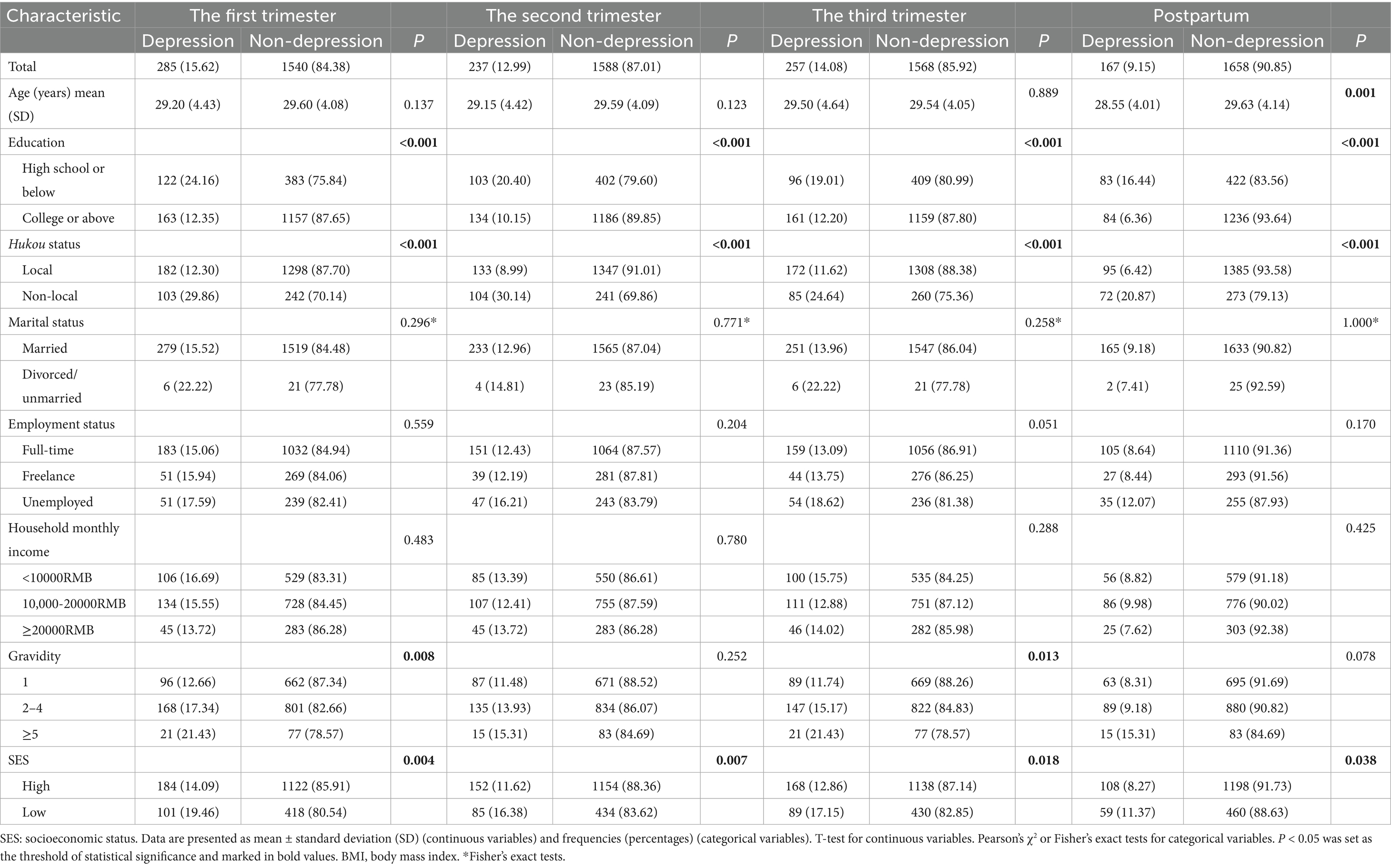

As depicted in Table 1, a total of 1,825 pregnant women were included in this longitudinal study, with an average age of 29.53 ± 4.14 years. The prevalence of depressive symptoms was 15.62% in the first trimester, 12.99% in the second trimester, 14.08% in the third trimester, and 9.15% postpartum.

Significant differences (p < 0.05) in basic demographic data were observed between depressed and non-depressed women in the first trimester, including educational level, only-child status, hukou status, gravidity, infectious diseases (HIV, syphilis, hepatitis B, and others), pregnancy planning status, and SES. In the second trimester, significant differences (p < 0.05) were found in educational level, only-child status, hukou status, infectious diseases, and SES. In the third trimester, significant associations (p < 0.05) were identified in educational level, only-child status, hukou status, gravidity, infectious diseases, and SES. Postpartum assessments revealed significant differences (p < 0.05) in maternal age, educational level, only-child status, hukou status, infectious diseases, pregnancy planning status, and SES. The complete results are presented in Supplementary Table 2.

3.2 Depressive symptoms

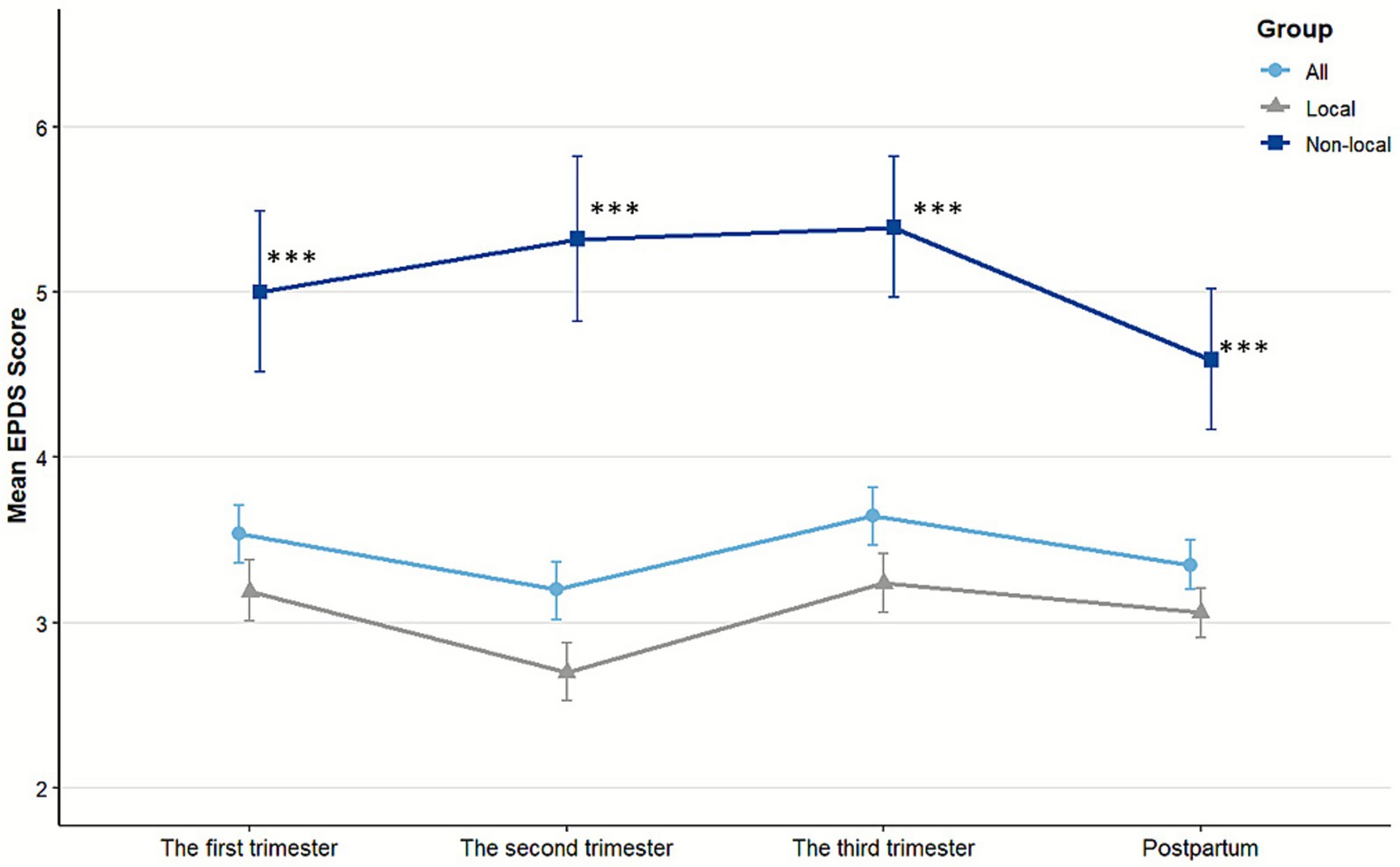

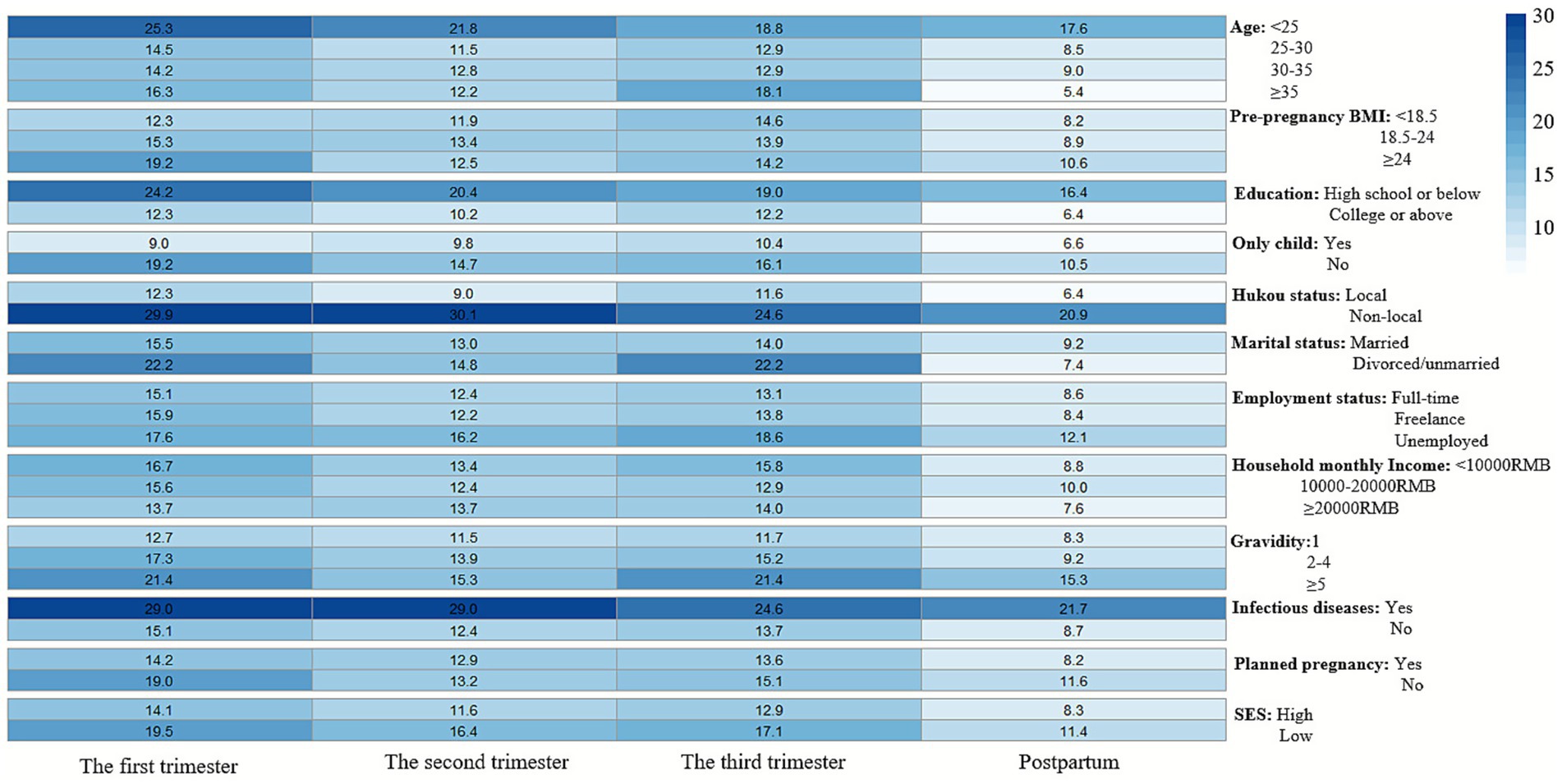

Figures 1, 2 illustrate the longitudinal trajectories of depressive symptoms across perinatal stages. In our cohort, 29.10% (531/1,825) of pregnant women exhibited at least one EPDS score ≥ 9 during the four assessed stages. The overall differences in EPDS scores across stages reached statistical significance (p < 0.001), with peak severity observed during the third trimester (mean EPDS score = 3.65, 95% CI: 3.47–3.82). A notable divergence emerged in the second trimester: while local women’s scores decreased (mean = 2.70, 95% CI: 2.53–2.88), scores for non-local women increased (mean = 5.32, 95% CI: 4.82–5.82). Non-local women consistently demonstrated higher EPDS scores than their local counterparts at every stage (all p < 0.001; Figure 1, detailed data in Supplementary Table 3). Statistical analysis of overall depression symptom prevalence rates similarly revealed significant variations across gestational periods (p < 0.001; Figure 2). As visually presented in Figure 2, which illustrates depression rates by maternal characteristics at each study timepoint, the prevalence of depressive symptoms showed a consistent decline during the postpartum period. Notably, non-local women exhibited persistently elevated rates (20.9–30.1% across stages), with the most pronounced disparity occurring in the second trimester (30.1% vs. 9.0% for local women). Overall, the risk of depression for non-local women was consistently higher, with prevalence ratios of 2.43 in the first, 3.34 in the second, 2.12 in the third trimester, and 3.27 postpartum compared to their local counterparts.

Figure 1. Mean EPDS scores with 95% confidence intervals by pregnancy stages and hukou status. Non-local women demonstrated significantly higher depression scores than local women at all stages (all p < 0.001). Significance levels: ***p < 0.001.

Figure 2. Heatmap of depression symptom prevalence (EPDS ≥ 9). Darker shading indicates higher incidence rates. The overall depression prevalence differences across pregnancy stages were statistically significant (p < 0.001).

3.3 Associations of depressive symptoms with hukou status and covariates across pregnancy stages

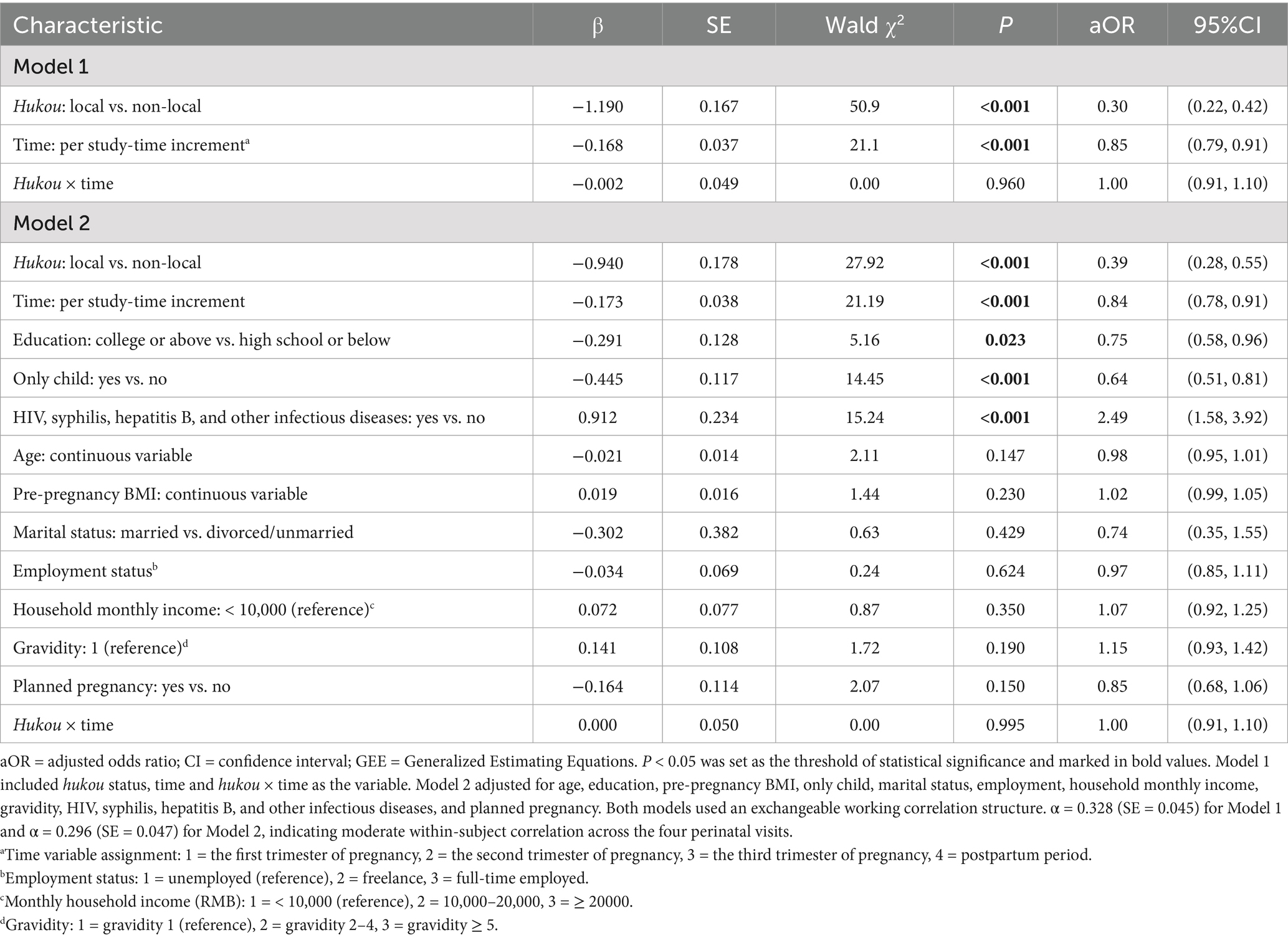

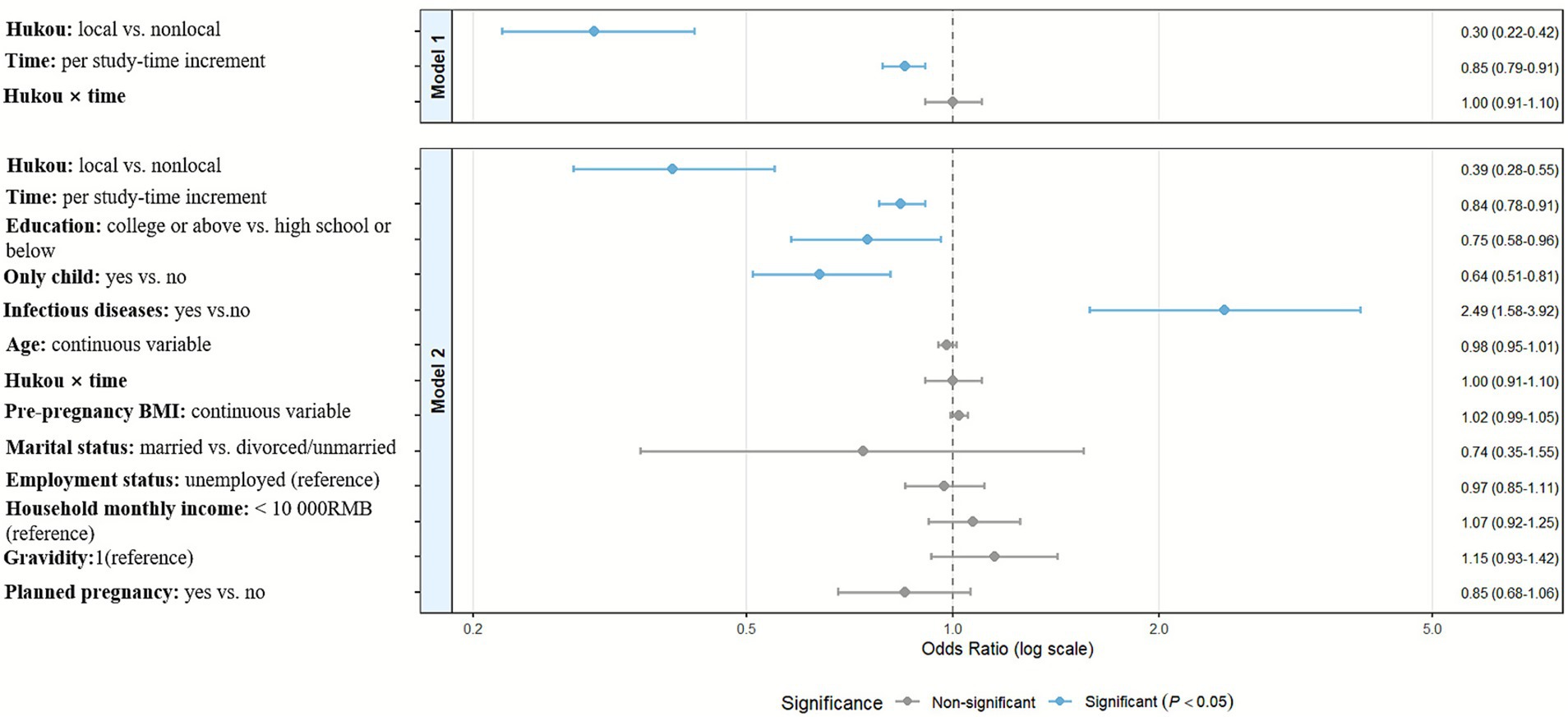

As shown in Table 2, the GEE analysis demonstrated that local hukou status conferred a significant protective effect against PND (aOR = 0.30, 95% CI: 0.22–0.42, p < 0.001), which remained robust after full adjustment for covariates (aOR = 0.39, 95% CI: 0.28–0.55, p < 0.001). With each successive study time point (from the first trimester to postpartum), the odds of depressive symptoms significantly decreased by 16% (aOR = 0.84, 95% CI: 0.78–0.91, p < 0.001) in the fully adjusted model (Model 2). Critically, the interaction between hukou status and time was not statistically significant (aOR = 1.00, 95% CI: 0.91–1.10, p = 0.995). This indicates that the protective effect of local hukou against depressive symptoms remained consistent in magnitude across all perinatal stages (trimesters 1–3 and postpartum) and did not vary significantly over time. Additionally, high degree (university and above), only-child status were found to be associated with a lower likelihood of depression (all aOR < 1, all p < 0.05), while history of infectious diseases was associated with increased PND risk (aOR = 2.49, 95% CI: 1.58–3.92, p < 0.001). These findings are visually summarized in Figure 3. Supplementary multivariable logistic regression analyses, which demonstrated adequate model fit (Hosmer-Lemeshow test p > 0.05, Supplementary Table 4) and no concerning multicollinearity (VIF < 2, Supplementary Table 5), consistently showed significantly reduced odds of depressive symptoms among women with local hukou across all perinatal stages compared to non-local women (all p < 0.05). Detailed results are provided in Supplementary Table 6 and Supplementary Figure 1.

Table 2. Association between hukou status (local vs. non-local) and perinatal depressive symptoms using GEE (N = 7,300 observations).

Figure 3. Forest plot analysis of hukou status and covariates associated with perinatal depression symptoms.

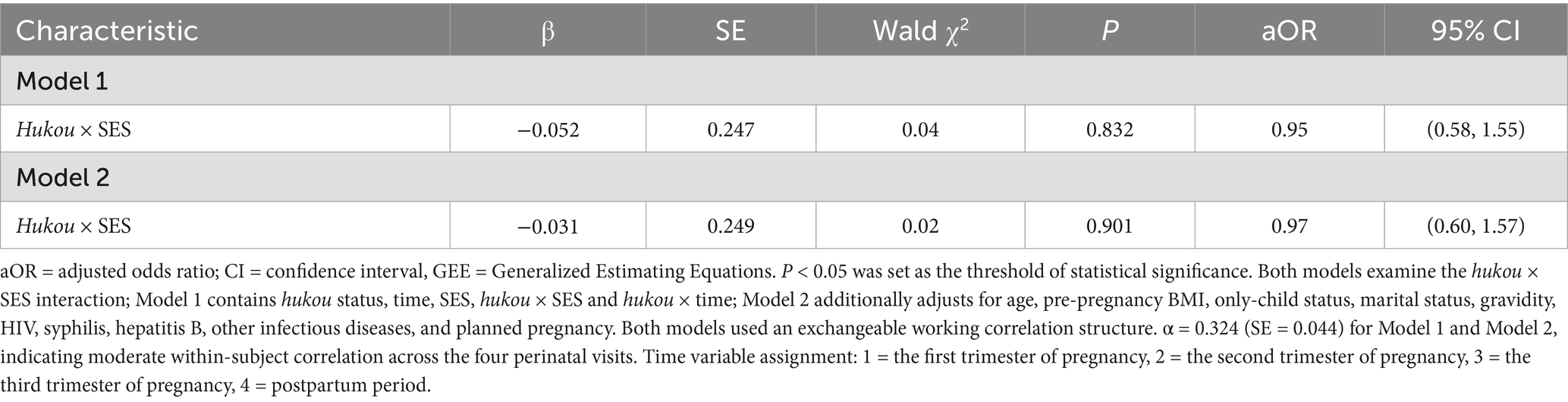

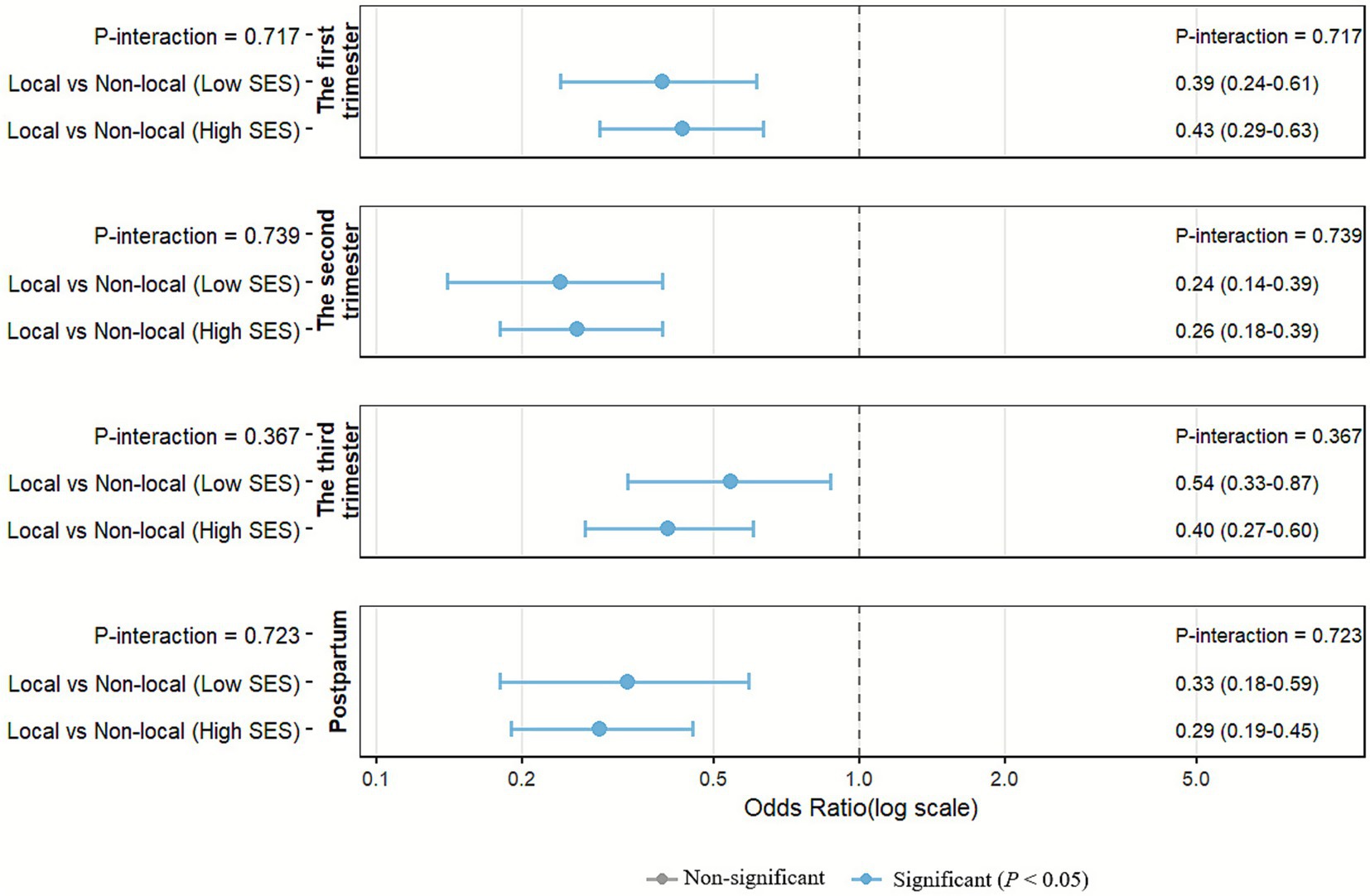

3.4 Interaction analysis between hukou status and SES on depression risk

Interaction results are presented in Table 3. In the longitudinal GEE model, the multiplicative interaction between hukou status and SES was non-significant both before and after adjustment for covariates (Model 1: aOR = 0.95, 95% CI 0.58–1.55, P-interaction = 0.832; Model 2: aOR = 0.97, 95% CI 0.60–1.57, P-interaction = 0.901). Furthermore, interactions between hukou status and each of the individual SES components (education, household monthly income, and employment status) also showed no statistically significant effects (all P-interaction > 0.05, Supplementary Table 7). Thus, we found no evidence that the protective effect of local hukou varies by SES level. To further explore these associations descriptively, we also conducted stratum-specific analyses using separate multivariable logistic regression models at each visit (Figure 4). The direction of effect was consistent (all P-interaction>0.05). Local hukou was associated with lower depression risk in both SES strata across all time points. Thus, the data support the conclusion that hukou status acts as a determinant of depression risk irrespective of SES.

Table 3. Effect of the hukou × SES interaction on perinatal depressive symptoms using GEE (N = 7,300 observations).

Figure 4. Interaction effects between hukou status and SES on depression risk across pregnancy stages (multivariate logistic regression). SES: socioeconomic status. All models adjusted for age, hukou status, SES, pre-pregnancy BMI, only child, marital status, gravidity, HIV, syphilis, hepatitis B, and other infectious diseases, and planned pregnancy.

3.5 Sensitivity analysis

In our sensitivity analyses, the prevalence trends of depressive symptoms remained largely consistent across perinatal periods when using different EPDS cutoffs (≥ 9, ≥ 10, ≥ 13) (Supplementary Table 8). In the adjusted GEE model, local hukou remained a significant protective factor at both the EPDS ≥ 10 (aOR = 0.44, 95% CI: 0.30–0.63, p < 0.001) and EPDS ≥ 13 (aOR = 0.31, 95% CI: 0.14–0.65, p = 0.002) thresholds (Supplementary Table 9). These findings were further confirmed by supplementary logistic regression analyses, where the protective effect was uniformly observed in each perinatal period after full adjustment (for EPDS ≥ 10: aOR range 0.21–0.55, all p < 0.05; for EPDS ≥ 13: aOR range 0.12–0.39, all p < 0.05) (Supplementary Table 10).

4 Discussion

In this study, we found that the prevalence of depressive symptoms (EPDS ≥ 9) significantly decreased in the postpartum period. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first investigation of the longitudinal association between hukou status and PND across pregnancy and postpartum stages in Chinese women. The results suggested that China’s hukou system significantly influences PND risk, with local hukou conferring consistent protection across all pregnancy stages and postpartum. Notably, the nonsignificant interaction between hukou status and SES indicated that this protective effect was not modified by SES.

Our study found that the prevalence of depression in the first trimester was 15.62%, while the incidence of postpartum depression symptoms decreased significantly (9.15%). This trend remained consistent even after stratification by basic demographic characteristics. This overall prevalence of PND in Ningbo is lower than rates reported in many other parts of China. For instance, a nationwide meta-analysis reported an overall PND prevalence of 16.3%, with prenatal and postpartum depression rates of 19.7% and 14.8%, respectively (30). Furthermore, studies from specific Chinese regions have reported higher rates, such as a postpartum depression prevalence of 23.5% in Shanghai (2019) (31) and 18.0% in Guangdong and Guangxi provinces (2021–2023) (32). Despite the lower overall prevalence in Ningbo, our study further reveals a stark disparity: the prevalence of depressive symptoms among non-local women persistently exceeded 20% across all perinatal stages. This rate is comparable to the general prevalence reported among pregnant women in other Chinese regions but is significantly higher than that of their local counterparts within Ningbo. Globally, a systematic review showed that the average overall prevalence rates of PND, prenatal depression, and postpartum depression were 26.3%, 28.5%, and 27.6%, respectively (33). Another meta-analysis revealed that the overall prevalence of PND was 24.7% (95% CI: 23.7–25.6%). The highest prevalence was observed in low- and middle-income countries, with an overall prevalence of 25.5% (95% CI: 23.8–27.1%), followed by upper-middle-income countries (overall prevalence of 24.7, 95% CI: 23.6–25.9%). Additionally, the prevalence of PND was lowest in the East Asia and Pacific region, at 21.4% (95% CI: 19.8–23.1%) (34). Our EPDS-based postpartum depression rates in Ningbo were significantly lower than those in Italy (35) and Ethiopia (19).

In the current study, the incidence of depressive symptoms among non-local registered pregnant women in Ningbo was significantly higher than that among local registered pregnant women (p < 0.05). We found that even after adjusting for covariates such as age, pre-pregnancy BMI, and education level, local hukou status remained a significant protective factor against perinatal depressive symptoms (aOR = 0.39, 95% CI: 0.28–0.55, p < 0.001). This protective association was consistent over time and remained statistically significant throughout all stages of pregnancy and the postpartum period (p < 0.001). Since China’s hukou system directly affects access to healthcare, housing eligibility, and educational resources (16), it is closely related to perinatal health. A study conducted in Beijing revealed that the non-local population has lower insurance coverage and utilization rates (36). A large-scale study in Shanghai further demonstrated that the unique hukou system restricts internal migrant women’s access to public services, thereby creating a potential pathway to the observed increased risk of high-risk pregnancies in this population (37). It is closely related to perinatal health. Our findings align with those of other international studies on immigrant populations (38, 39). Additionally, research indicates that the psychological status of rural and urban migrants is poor and merits further investigation (40). Thus, China’s unique hukou system deprives internally non-local women of public health services and social support compared to local registered women, rendering them a potentially vulnerable group. Taken together, our core finding is that the hukou system is an independent determinant of perinatal mental health—and this likely points to a systemic risk that exists nationwide. While the manifestation and intensity of this risk may vary across regions, it is reasonable to argue that the effect could be even more pronounced in areas with fewer social safety nets.

SES, including education level and family economic status, is an important factor contributing to maternal depressive symptoms (20, 41). Our interaction analysis shows that the protective effect of hukou status exists independently of SES. Past studies suggest that high SES may reduce the risk of depression among immigrant populations. A meta-analysis further underscores the vulnerability of this group, revealing that one in four migrant women develops PND, with the burden appearing even higher among forced migrants compared to economic migrants (42). Supporting this, a study in Belgium reported that immigrants from Turkey and Morocco had significantly higher prevalence of depressive symptoms compared to native Belgians (20.9% vs. 5.85–9.43%). Additionally, the study’s multivariate analysis suggested that high SES may mitigate the risk of depressive symptoms (43). However, a survey in Spain found that the self-reported prevalence of depression and antidepressant use among immigrant groups was lower than among native Spanish adults (44). This may be attributed to the healthy immigrant effect (45), as immigrants who remained in the country after the economic crisis had more favorable conditions in terms of social status and health. Similarly, studies in China have shown that the level of depressive symptoms is significantly higher among the temporary non-local population (β = 0.97, 95% CI: 0.38–1.56) and the permanent non-local population (β = 0.52, 95% CI: 0.04–1.00) compared to urban residents (14). This study demonstrates that China’s hukou system may limit the conversion of socio-economic resources into mental health benefits for non-local women, thereby making it challenging for them to achieve the same level of psychological protection even if they possess a higher economic status (46). Psychological interventions for the non-local population need to go beyond mere economic assistance and focus on fundamental reforms to the restrictive hukou system and the uneven distribution of resources and opportunities in urban and rural areas (40).

Compared to international migration studies, China presents a distinct paradigm. International literature often attributes deteriorating immigrant mental health primarily to language barriers, cultural differences, and workplace discrimination (47, 48). In China, however, the hukou system serves as a powerful structural determinant, legally tying access to public services and welfare benefits to one’s registered residence (49). This direct institutional barrier may prove more fundamental and intractable than the sociocultural obstacles faced by international migrants. The vulnerability of non-local women manifests through multiple pathways: institutional barriers to healthcare access; weakened social support networks due to migration; and socioeconomic insecurity. The paradoxical lack of a protective effect from higher SES further suggests that hukou-related implicit barriers, such as unequal access to quality resources, may counteract the benefits typically conferred by socioeconomic advantages. To address this structural unfairness, we recommend two pathways to delink medical service access from the hukou system: Firstly, enhance the existing residence permit system by explicitly granting non-local resident equal access to basic public services, including prenatal care. Secondly, accelerate the development of a nationwide, interoperable electronic maternal health record to eliminate information gaps and duplicate testing across regions. Clinically, these findings call for integrating hukou status into routine psychosocial assessments. Given the persistent risk, we recommend repeated depression screening for non-local women throughout the entire perinatal period, coupled with proactive referrals to community support resources.

This study has several strengths. First, it employs a prospective cohort design, with consecutive recruitment from four regional maternal and child health institutions, thereby enhancing the study’s internal validity. Second, longitudinal assessment of depressive symptoms across all pregnancy trimesters and postpartum provides dynamic data superior to cross-sectional approaches. However, this study also has some limitations. First, because we did not measure potential mediators such as access to health care, social support, or perceived discrimination, we cannot identify the specific pathways through which local hukou exerts its protective effect. Second, our sample consisted mainly of married, employed women, which limits the generalizability of the findings to more vulnerable non-local groups (e.g., unmarried women or those without stable employment). Third, although the EPDS is well suited for large-scale epidemiologic screening and our sensitivity analyses confirmed the robustness of the results, the absence of a clinical interview to confirm diagnoses may have reduced the clinical specificity of our findings. Finally, as an observational study, residual confounding cannot be ruled out despite adjustment for a wide range of covariates and extensive sensitivity analyses. Future research should incorporate the aforementioned mediators, deliberately recruit more vulnerable sub-populations, and integrate clinical diagnoses to further validate and extend the present findings.

5 Conclusion

In conclusion, this study demonstrates that China’s hukou system remains significantly associated with PND after adjustment for measured confounders, with local hukou providing substantial protection across all pregnancy stages. Therefore, decoupling healthcare access from hukou status and implementing targeted interventions during high-risk periods may help alleviate mental health disparities among China’s non-local pregnant population.

Data availability statement

The datasets presented in this article are not readily available due to privacy and ethical restrictions concerning research involving pregnant women; the raw data are not deposited in a public repository. Requests to access the datasets should be directed to XG, at eHVlanVuZ3VuYkAxNjMuY29t.

Ethics statement

The studies involving humans were approved by the Medical Ethics Committee of Women and Children’s Hospital of Ningbo University. The studies were conducted in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. The participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study.

Author contributions

TZ: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Methodology, Writing – original draft. YS: Data curation, Methodology, Writing – original draft. FC: Supervision, Writing – review & editing. XY: Supervision, Methodology, Writing – original draft. CJ: Writing – review & editing. XG: Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declare that financial support was received for the research and/or publication of this article. This work was supported by the Medical Science and Technology Project of Zhejiang Province, China (grant number 2022KY1166); the Ningbo Natural Science Foundation (grant number 2019A610303), and Women’s Health Care of Ningbo Key Support Discipline (grant number 2022-F27).

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank every member of the staff who participated in this project. Additionally, we are grateful for the invaluable support and assistance provided by Women and Children’s Hospital of Ningbo University, which enabled our work to proceed smoothly and achieve positive results.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The author(s) declare that no Gen AI was used in the creation of this manuscript.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Supplementary material

The Supplementary material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fpubh.2025.1711901/full#supplementary-material

References

1. Acog. Acog committee opinion no. 757: screening for perinatal depression. Obstet Gynecol. (2018) 132:e208–12. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0000000000002927

2. Nisar, A, Yin, J, Waqas, A, Bai, X, Wang, D, Rahman, A, et al. Prevalence of perinatal depression and its determinants in mainland China: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Affect Disord. (2020) 277:1022–37. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2020.07.046

3. Pan, T, Zeng, Y, Chai, X, Wen, Z, Tan, X, and Sun, M. Global prevalence of perinatal depression and its determinants among rural women: a systematic review and Meta-analysis. Depress Anxiety. (2024) 2024:1882604. doi: 10.1155/2024/1882604

4. Caropreso, L, De Azevedo Cardoso, T, Eltayebani, M, and Frey, BN. Preeclampsia as a risk factor for postpartum depression and psychosis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Arch Womens Ment Health. (2020) 23:493–505. doi: 10.1007/s00737-019-01010-1

5. Wilson, CA, Newham, J, Rankin, J, Ismail, K, Simonoff, E, Reynolds, RM, et al. Is there an increased risk of perinatal mental disorder in women with gestational diabetes? A systematic review and meta-analysis. Diabet Med. (2020) 37:602–22. doi: 10.1111/dme.14170

6. Hagatulah, N, Bränn, E, Oberg, AS, Valdimarsdóttir, UA, Shen, Q, and Lu, D. Perinatal depression and risk of mortality: nationwide, register based study in Sweden. BMJ. (2024) 384:e075462. doi: 10.1136/bmj-2023-075462

7. Yu, H, Shen, Q, Bränn, E, Yang, Y, Oberg, AS, Valdimarsdóttir, UA, et al. Perinatal depression and risk of suicidal behavior. JAMA Netw Open. (2024) 7:e2350897. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2023.50897

8. Zhang, ZY, Yu, JJ, Zeng, WT, Zhou, MC, Duan, CC, and Zhu, LL. Association between antenatal depression and adverse perinatal outcomes: a prospective cohort study. J Affect Disord. (2023) 323:490–5. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2022.12.008

9. Zhu, Y, Li, X, Chen, J, and Gong, W. Perinatal depression trajectories and child development at one year: a study in China. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. (2024) 24:176. doi: 10.1186/s12884-024-06330-4

10. Cleary, S, Orangi, S, Garman, E, Tabani, H, Schneider, M, and Lund, C. Economic burden of maternal depression among women with a low income in Cape Town, South Africa. BJPsych Open. (2020) 6:e36. doi: 10.1192/bjo.2020.15

11. Chen, JJ. Study on the effect of basic medical insurance on the SocialIntegration of urban and rural floating population UnderPerspective of intergenerational differentiation and InstitutionalDivision:Empirical test based on dynamic MonitoringData of floating population in 2017(master's thesis). Chengdu, China: Southwestern University of Finance and Economics (2022).

12. Song, YP, Wang, ZL, and Wu, HT. Impact of Hukou system reform on fertility decisions of migrants: a public service perspective. Popul Res. (2025) 49:101–16. doi: 10.12451/202509.02292

13. Chan, KW. The household registration system and migrant labor in China: notes on a debate. Popul Dev Rev. (2010) 36:357–64. doi: 10.1111/j.1728-4457.2010.00333.x

14. Guo, J, Guan, L, Fang, L, Liu, C, Fu, M, He, H, et al. Depression among Chinese older adults: a perspective from Hukou and health inequities. J Affect Disord. (2017) 223:115–20. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2017.07.032

15. Guan, M. Should the poor have no medicines to cure? A study on the association between social class and social security among the rural migrant workers in urban China. Int J Equity Health. (2017) 16:193. doi: 10.1186/s12939-017-0692-x

16. Wu, J, Liu, R, Shi, L, Zheng, L, He, N, and Hu, R. Association between resident status and patients' experiences of primary care: a cross-sectional study in the Greater Bay Area, China. BMJ Open. (2022) 12:e055166. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2021-055166

17. Qiu, P, Caine, E, Yang, Y, Chen, Q, Li, J, and Ma, X. Depression and associated factors in internal migrant workers in China. J Affect Disord. (2011) 134:198–207. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2011.05.043

18. Gastaldon, C, Solmi, M, Correll, CU, Barbui, C, and Schoretsanitis, G. Risk factors of postpartum depression and depressive symptoms: umbrella review of current evidence from systematic reviews and meta-analyses of observational studies. Br J Psychiatry. (2022) 221:591–602. doi: 10.1192/bjp.2021.222

19. Rtbey, G, Andualem, F, Nakie, G, Takelle, GM, Mihertabe, M, Fentahun, S, et al. Perinatal depression and associated factors in Ethiopia: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Psychiatry. (2024) 24:822. doi: 10.1186/s12888-024-06246-5

20. Yang, K, Wu, J, and Chen, X. Risk factors of perinatal depression in women: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Psychiatry. (2022) 22:63. doi: 10.1186/s12888-021-03684-3

21. Chan, KW, and Zhang, L. The "hukou" system and rural-urban migration in China: processes and changes. China Q. (1999) 160:818–55. doi: 10.1017/S0305741000001351

22. Erwin, EA, and Kelleher, KJ. Understanding the highs and lows of socioeconomic status. J Allergy Clin Immunol. (2022) 149:1585–6. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2022.03.007

23. Guan, H, Sun, B, Yang, L, and Zhang, Y. Assessment of the factor structure of the Epds in Chinese perinatal women: a longitudinal study using multigroup confirmatory factor analysis. Front Psychol. (2025) 16:1526716. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2025.1526716

24. Lau, Y, Wang, Y, Yin, L, Chan, KS, and Guo, X. Validation of the mainland Chinese version of the Edinburgh postnatal depression scale in Chengdu mothers. Int J Nurs Stud. (2010) 47:1139–51. doi: 10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2010.02.005

25. Chen, L, and Shi, Y. Analysis of influencing factors and the construction of predictive models for postpartum depression in older pregnant women. World J Psychiatry. (2023) 13:1079–86. doi: 10.5498/wjp.v13.i12.1079

26. Lee, DT, Yip, SK, Chiu, HF, Leung, TY, Chan, KP, Chau, IO, et al. Detecting postnatal depression in Chinese women. Validation of the Chinese version of the Edinburgh postnatal depression scale. Br J Psychiatry. (1998) 172:433–7. doi: 10.1192/bjp.172.5.433

27. Gao, M, Hu, J, Yang, L, Ding, N, Wei, X, Li, L, et al. Association of sleep quality during pregnancy with stress and depression: a prospective birth cohort study in China. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. (2019) 19:444. doi: 10.1186/s12884-019-2583-1

28. Huang, X, Zhang, L, Zhang, C, Li, J, and Li, C. Postpartum depression in northeastern China: a cross-sectional study 6 weeks after giving birth. Front Public Health. (2025) 13:1570654. doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2025.1570654

29. Sun, R, Zhao, M, Ma, L, Duan, Y, and Wei, J. High psychological stress levels related to delivery can increase the occurrence of postpartum mental disorders. Front Psych. (2023) 14:1273647. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2023.1273647

30. Peng, S, Lai, X, Du, Y, Meng, L, Gan, Y, and Zhang, X. Prevalence and risk factors of postpartum depression in China: a hospital-based cross-sectional study. J Affect Disord. (2021) 282:1096–100. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2021.01.012

31. Liu, Y, Zhang, L, Guo, N, and Jiang, H. Postpartum depression and postpartum post-traumatic stress disorder: prevalence and associated factors. BMC Psychiatry. (2021) 21:487. doi: 10.1186/s12888-021-03432-7

32. Zhang, Q, Qiu, M, Guo, L, Li, Y, Xie, Z, Yang, W, et al. Association between maternal weight perception before and during pregnancy and postpartum depression status in southern China. Nutrients. (2024) 16:3696. doi: 10.3390/nu16213696

33. Al-Abri, K, Edge, D, and Armitage, CJ. Prevalence and correlates of perinatal depression. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. (2023) 58:1581–90. doi: 10.1007/s00127-022-02386-9

34. Roddy Mitchell, A, Gordon, H, Lindquist, A, Walker, SP, Homer, CSE, Middleton, A, et al. Prevalence of perinatal depression in low- and middle-income countries: a systematic review and Meta-analysis. JAMA Psychiatry. (2023) 80:425–31. doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2023.0069

35. Camoni, L, Gigantesco, A, Guzzini, G, Pellegrini, E, and Mirabella, F. Epidemiology of perinatal depression in Italy: systematic review and meta-analysis. Ann Ist Super Sanita. (2023) 59:139–48. doi: 10.4415/ANN_23_02_07

36. Ma, C, Zhang, Y, Li, Y, Wang, Y, Jiang, Y, Wang, X, et al. Healthcare, insurance, and medical expenditure of the floating population in Beijing, China. Front Public Health. (2020) 8:375. doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2020.00375

37. Tang, D, Gao, X, and Coyte, PC. The relationship between internal migration and the likelihood of high-risk pregnancy: Hukou system and high-risk pregnancies in China. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. (2021) 21:509. doi: 10.1186/s12884-021-03958-4

38. Anderson, FM, Hatch, SL, Comacchio, C, and Howard, LM. Prevalence and risk of mental disorders in the perinatal period among migrant women: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Arch Womens Ment Health. (2017) 20:449–62. doi: 10.1007/s00737-017-0723-z

39. Fellmeth, G, Fazel, M, and Plugge, E. Migration and perinatal mental health in women from low- and middle-income countries: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BJOG. (2017) 124:742–52. doi: 10.1111/1471-0528.14184

40. Chen, J. Internal migration and health: re-examining the healthy migrant phenomenon in China. Soc Sci Med. (2011) 72:1294–301. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2011.02.016

41. Zhang, G, Cai, C, Zou, W, Jing, L, and Wu, S. Depressive symptoms and socioeconomic status among the labor force: evidence from China's representative sample. PLoS One. (2022) 17:e0272199. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0272199

42. Stevenson, K, Fellmeth, G, Edwards, S, Calvert, C, Bennett, P, Campbell, OMR, et al. The global burden of perinatal common mental health disorders and substance use among migrant women: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Public Health. (2023) 8:e203–16. doi: 10.1016/S2468-2667(22)00342-5

43. Levecque, K, Lodewyckx, I, and Vranken, J. Depression and generalised anxiety in the general population in Belgium: a comparison between native and immigrant groups. J Affect Disord. (2007) 97:229–39. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2006.06.022

44. Borrell, LN, Díez, J, Yago-González, S, Lanborena, N, and Rodríguez-Álvarez, E. Immigration status and depression in Spain: analysis of the European health interview surveys of 2014 and 2020. Gac Sanit. (2025) 39:102445. doi: 10.1016/j.gaceta.2024.102445

45. Blukacz, A, Oyarte, M, Cabieses, B, Madrid, P, and Obach, A. Mental health and the healthy immigrant effect in Chile: a comparative cross-sectional study with international migrants and locals. Front Public Health. (2025) 13:1582628. doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2025.1582628

46. Yang, M, Dijst, M, and Helbich, M. Mental health among migrants in Shenzhen, China: does it matter whether the migrant population is identified by Hukou or birthplace? Int J Environ Res Public Health. (2018) 15:2671. doi: 10.3390/ijerph15122671

47. Di Napoli, A, Rossi, A, Baralla, F, Ventura, M, Gatta, R, Perez, M, et al. Self-perceived workplace discrimination and mental health among immigrant workers in Italy: a cross-sectional study. BMC Psychiatry. (2021) 21:85. doi: 10.1186/s12888-021-03077-6

48. Krystallidou, D, Temizöz, Ö, Wang, F, De Looper, M, Di Maria, E, Gattiglia, N, et al. Communication in refugee and migrant mental healthcare: a systematic rapid review on the needs, barriers and strategies of seekers and providers of mental health services. Health Policy. (2024) 139:104949. doi: 10.1016/j.healthpol.2023.104949

Keywords: hukou status, perinatal depression, Edinburgh postnatal depression scale, socioeconomic status, pregnancy stages

Citation: Zhou T, Sun Y, Chen F, Yang X, Jiang C and Gu X (2025) Hukou status and perinatal depression: a longitudinal cohort study in China. Front. Public Health. 13:1711901. doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2025.1711901

Edited by:

Rixiang Xu, Anhui Medical University, ChinaReviewed by:

Vince Hooper, SPJ Global, United Arab EmiratesMd Adil Faizan, Government Medical College, Nizamabad, India

Wei Luo, Shanghai Jiading Maternal Child Health Hospital, China

Yueheng Peng, Chengdu University, China

Copyright © 2025 Zhou, Sun, Chen, Yang, Jiang and Gu. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Xuejun Gu, eHVlanVuZ3VuYkAxNjMuY29t

Tingting Zhou

Tingting Zhou Ying Sun1

Ying Sun1 Chen Jiang

Chen Jiang Xuejun Gu

Xuejun Gu