- 1Facultad de Enfermería y Fisioterapia, Universidad de Salamanca (USAL), Salamanca, Spain

- 2Instituto de Investigación Biomédica de Salamanca (IBSAL), Salamanca, Spain

- 3Unidad de Investigación de Atención Primaria de Salamanca (APISAL), Salamanca, Spain

- 4Hospital Universitario de Salamanca, Salamanca, Spain

- 5Facultad de Medicina, Universidad de Salamanca (USAL), Salamanca, Spain

- 6Research Center of Sleep Medicine, College of Medicine, Taipei Medical University, Taipei, Taiwan

- 7Red de Investigación en Cronicidad, Atención Primaria y Promoción de la Salud (RICAPPS), Barcelona, Spain

Background: Problematic use of new technologies has been associated with anxiety and other disorders in young adults. This study evaluated the efficacy of a Neurofeedback-Assisted Mindfulness Training Program (NAMTP) in reducing anxiety and related symptoms in young adults.

Methods: A randomized clinical trial assigned participants to an intervention group (IG), receiving 20-25 NAMTP sessions, or a control group (CG). All participants received a brief workshop on responsible technology use. Anxiety was assessed using the DASS-21 anxiety subscale. Secondary outcomes included the Smartphone Addiction Scale—Short Version (SAS-SV), Nomophobia Questionnaire (NMP-Q), and Athens Insomnia Scale (AIS), all evaluated at baseline and three months.

Results: A total of 40 participants completed the study (82.5% women; mean age 24.8 ± 3.4). No statistically significant differences were observed between the intervention group (IG) and the control group (CG) in any of the psychological variables assessed. For the DASS scales, the mean differences (IG–CG) were 0.1 (95% CI: −1.6 to 1.9; p = 0.868) for anxiety, −2.4 (95% CI: −7.2 to 2.4; p = 0.324) for depression, and −1.5 (95% CI: −5.3 to 2.4; p = 0.453) for stress. Similarly, the mean difference in the SAS-SV score was −1.0 (95% CI: −5.0 to 2.9; p = 0.606), while for the NMP-Q score it was 3.7 (95% CI: −8.9 to 16.4; p = 0.553). Finally, the Athens Insomnia score showed a mean difference of −1.1 (95% CI: −2.9 to 0.7; p = 0.211). Adherence to the NAMTP program was high (88.8%).

Conclusions: The NAMTP did not produce significant improvements in anxiety, mobile phone addiction, nomophobia, or sleep quality. These findings suggest that, although NAMTP is feasible and well-tolerated, further research is needed to determine its potential benefits.

Trial registration: Clinicaltrials.gov; NCT06188910. http://www.Clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT06188910.

1 Introduction

The use of new technologies, the internet, and mobile devices has increased in recent years, transforming the way we interact, obtain information, and entertain ourselves. Despite their benefits, the excessive and inappropriate use of these tools has led to growing concern about their negative impact on physical and mental health, especially in young people.

1.1 The effects of problematic technology use among young people

Various studies have linked problematic use of new technologies with symptoms of anxiety, depression, low self-esteem, eye strain (1, 2), attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD), sleep problems, hostility (3, 4), and reduced academic and work performance (5), among other issues (6). This phenomenon is especially alarming among children and adolescents, due to their developmental vulnerability and ongoing brain maturation.

Sleep is essential for healthy development, and insufficient sleep has become a public health concern. Longer screen time has been associated with poorer sleep quality, shorter sleep duration, and delayed bedtimes, especially in adolescents and young adults (7–9). While poor sleep may also lead to increased screen use, evidence suggests that evening smartphone exposure disrupts circadian rhythms and delays melatonin release (10). Notably, restricting mobile phone use before bedtime for several weeks has been shown to reduce sleep latency, improve sleep quality and duration, and enhance mood and cognitive performance (11).

A systematic review has indicated an association between problematic social media use and the presence of depression and anxiety in children under the age of 18. The mechanisms that have been identified include social comparison, sleep deprivation, and feedback-seeking behaviors (12). Several studies have demonstrated a significant positive association between problematic smartphone use (PSU) and anxiety symptom severity, consistently categorized as a small-to-moderate effect (13, 14). A comprehensive metanalysis identified that PSU significantly increases the risk of anxiety, with pooled odds ratio around 3.5 (15). From a theoretical perspective, anxiety may contribute to PSU through compensatory mechanisms, whereby excessive technological engagement serves as a maladaptive strategy for managing negative emotions. This association is supported by factors such as the Fear of Missing Out (FOMO), which mediates the link between anxiety and PSU severity (13, 14), and Negative Metacognition (NM), identified as key predictors in the pathway connecting anxiety dimensions with smartphone addiction (16).

Previous authors have suggested this excessive engagement as a behavioral addiction exhibiting addiction-like characteristics (17, 18). This problem exhibits high global prevalence. In Spain, 11.3% of individuals aged 15 and 24 who use the internet are at high risk of compulsive use (6). Globally, a systematic review revealed a 71% prevalence of internet addiction among university students in India (19). Similarly, research in Brazil found that 34.3% of participants reported problematic use, identifying female sex and screen time as key risk factors (20). Within this context, nomophobia—defined as the fear of being without a mobile phone—has become a specific focus of study. A meta-analysis examining its global prevalence across 52 studies from various continents found that moderate levels of nomophobia were the most prevalent, noting a significant upward trend in recent years (21). A predictive model of nomophobia highlighted the roles of fear of missing out, non-pathological compulsion, and rumination as key mechanisms explaining the condition (22).

1.2 Therapeutic approaches to technology addiction: the emerging role of mindfulness

In recent years, psychological, pharmacological, and healthy habit promotion strategies have been studied to address addiction to new technology. A meta-analysis demonstrated the efficacy of interventions such as Cognitive Behavioral Therapy (CBT), physical activity, pharmacological treatments, and group therapy in reducing internet addiction (23).

Among these, mindfulness has gained relevance due to its capacity to improve self-control and reduce symptoms such as nomophobia (24). It has been shown that even a single mindfulness session can alleviate symptoms associated with excessive mobile phone use (25), and that regular practice can be key in preventing addictive behaviors (24, 26).

Recent research supports its application. A study in adolescents showed that a mindfulness program acted as a mediator in PSU, improving levels of depression and sleep problems (27). Other research evaluated short online mindfulness programs, with daily 10-min sessions over 30 days, observing efficacy in reducing various forms of mobile addiction: mobile social media addiction, mobile game addiction, mobile in-formation acquisition addiction, and mobile short-form video addiction (28). The combined use of mindfulness and Tai Chi Chuan has also shown significant improvements in both mobile addiction and inhibition capacity, a key component in controlling addictive behaviors (29).

However, evidence regarding sleep quality is mixed. For example, in a group of nurses with insomnia, mindfulness treatment did not show significant improvements compared to the standard treatment (CTB), which proved more effective (30).

1.3 Neurofeedback as a complementary approach to mindfulness and addiction treatment

Mindfulness interventions are beneficial but often challenging to implement broadly, as they typically require specialized instructors and structured training. In this context, neurofeedback-assisted mindfulness emerges as a more accessible and scalable alternative. Neurofeedback (NF) is a biofeedback technique that trains individuals to self-regulate their brain activity through real-time feedback of electrical signals from the brain, mainly recorded through electroencephalography (EEG) (31, 32). This technique is valuable because it has demonstrated the ability to increase the power of alpha waves -associated with attentional focus- even in subjects with no prior meditation experience (26).

NF is a therapeutic technique aimed at the prevention, optimization, and rehabilitation of altered states of cortical activity, which has been shown to be effective in the treatment of various conditions, including anxiety, depression, ADHD, and post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) (33). Regarding anxiety disorders, evidence supports its effectiveness, as indicated by the clinical guidelines of the Canadian Agency for Drugs and Technologies in Health (34), which reported significant improvements in patients with PTSD and generalized anxiety compared to those who did not receive treatment (34). Similarly, a clinical trial in young university students with generalized anxiety disorder showed that the group treated with NF experienced a significant reduction in anxiety and depression levels, along with enhanced emotional regulation compared to the control group (35).

At a psychological level, research supports NF's potential in addictions. A recent meta-analysis evaluating EEG-NF effects on addiction reported symptoms improvement, especially in substance-related addictions. Behavioral addictions, such as internet addiction, showed lower heterogeneity, suggesting similar patterns of brain dysregulation (36). EEG studies in individuals with internet addiction reveal a pattern characterized by reduced beta activity and increased gamma activity (37), along with a predominance of slow frontal waves, which is associated with a deficit in inhibitory control (38). This opens a pathway for NF use to restore brain activity balance.

Based on a recent systematic review, mindfulness-based interventions assisted by NF enhance functional connectivity within and between key brain networks, improving self-regulation and cognitive control (39). This practice has been shown to influence activity in the insula (40) and the posterior cingulate cortex (41), two brain areas implicated in processes such as rumination, a central mechanism in nomophobia (22).

Initial studies on the combined application are promising. A randomized clinical trial among children and adolescents in South Korea demonstrated significant improvements on the Internet Addiction Scale following participation in a NF program guided by a mobile application (42). However, similar to the mindfulness findings, studies on NF focused on alpha waves have found non-significant results regarding objective sleep measures (43), consistent with other reviews concluding that NF offers no additional benefits for insomnia compared to other treatments (44).

1.4 Objectives and hypotheses

The primary objective of this study was to evaluate the efficacy of a Neurofeedback-Assisted Mindfulness Training Program (NAMTP) in reducing anxiety among young Spanish adults. The secondary objectives were to examine the program's effects on mobile phone addiction, nomophobia, and sleep quality.

The study hypothesized that the NAMTP would demonstrate a positive effect in reducing anxiety. The combination of NF and mindfulness was expected to be more effective because it uses real-time feedback to train the brain through reinforcement learning. This is a more robust way to build self-regulation skills (45), needed to manage anxiety.

2 Methods

2.1 Study design

A two-arm, parallel-group randomized clinical trial was conducted in Salamanca, Spain, from February 2024 to February 2025. This randomized controlled trial was conducted in accordance with the Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials (CONSORT) guidelines (46).

The clinical trial was registered at clinicaltrials.gov with the code NCT06188910 on January 02, 2024.

The study protocol has been published previously (47). The main results of this study are presented in this manuscript.

2.2 Study participants and recruitment

Participants were recruited through social media platforms and posters displayed in local health centers that advertised the study. Volunteers from the Salamanca area who met the following inclusion criteria were recruited: aged between 18 and 35, regular smartphone users, fully capable of completing the questionnaires, and having signed the informed consent form. Exclusion criteria included a history of serious psychiatric disorders, such as bipolar disorder, major depressive episode, or other non-organic psychotic disorders, requiring treatment within the 6 months prior to enrollment; or any brain injuries or conditions that contraindicated the use of NF.

2.3 Sample size

The sample size was estimated based on the primary outcome variable of anxiety, as measured by the Depression, Anxiety and Stress Scale (DASS-21). According to the study by Abdian et al. (35), it was determined that a total of 40 participants were required to detect a significant difference of 3.9 points or greater. The estimation was calculated with an alpha risk of 0.05 and a beta risk of 0.2, estimating a follow-up loss of 20%.

2.4 Randomization and blinding

Following the baseline assessment, participants were randomly assigned in a 1:1 ratio to either the control group (CG) or the intervention group (IG). Simple randomization was performed using a computer-generated sequence created by Epidat 4.2. software.

To ensure allocation concealment, a member of the research team who was not involved in participant enrollment was responsible for the randomization process.

After the baseline assessment was completed, participants were assigned a study identification number; this information was sent to the independent researcher, who used the pre-generated concealed allocation list to determine the participant's assigned group and informed the nurse responsible for delivering the intervention.

Due to the nature of the intervention, neither the participants nor the fieldwork nurse could be blinded to group assignments.

2.5 Intervention

All study participants in both groups (CG and IG) received an initial 30-min educational workshop on the responsible use of mobile phones and new technologies, conducted by a researcher.

The workshop included slides and printed handouts summarizing digital balance concepts and practical advice for healthy technology use. It began with a brief introduction explaining key concepts, followed by a guided reflection on personal technology use and strategies to establish healthy boundaries, concluding with a summary emphasizing awareness of digital identity and footprint. It took place individually in a designated room at the Nursing Faculty of the University of Salamanca.

The workshop was delivered identically to all participants, with minor clarifications or examples provided upon questions but no individualized modifications. No changes were made relative to the original protocol, and adherence was recorded for all participants, ensuring that all workshop components were delivered according to the planned schedule.

In addition to this workshop, only the IG received the NAMTP, which consisted of 20–25 sessions held 2–3 times per week. Each session lasted between 10 and 15 min. The number and duration of sessions were determined based on prior literature and studies with similar methodologies, which employed short EEG-based mindfulness or neurofeedback interventions. These studies reported measurable improvements in internet addiction disorder after 20 sessions, providing a basis for selecting a similar protocol in this study to explore comparable effects (36, 48). Furthermore, this dosage aimed to balance intervention intensity with participant adherence while maintaining sufficient training exposure.

Although traditional EEG systems retain superior spatial resolution and signal fidelity compared to mobile consumer-grade devices (49), the latter's value proposition is strongly rooted in accessibility and portability. According to a recent scoping review, consumer-grade EEG devices have demonstrated considerable utility across diverse research domains, thereby reinforcing the potential of affordable, portable technology to expand access to brain research and promote a more inclusive and equitable approach to neuroscience (50).

The study used the MUSE® device (InteraXon Inc.), specifically the Muse 2 and Muse S Headband models, which record EEG signals from four channels: an electrode on each side of forehead (AF7-AF8), two sensors behind the ears (TP9-TP10) and a reference electrode in the center of the forehead (FPz) (51, 52). Recognized as a cost-efficient mobile-EEG tool, the MUSE® has demonstrated validated utility in capturing electrophysiological markers of basic sensory and cognitive processes (51, 53, 54). Previous MUSE®-based studies have established these markers as reliable behavioral correlations of attentional control and mindfulness engagement, showing reductions in mind wandering (55, 56).

Through its sensors, the device records brain signals and transmits them via Bluetooth to the Muse: EEG Meditation & Sleep mobile app, which uses machine learning algorithms to analyze brain waves and classify the mental state as calm, neutral, or active. The algorithm processes brain activity in the delta (1–4 Hz), theta (4–8 Hz), alpha (8–13 Hz), beta (13–30 Hz), and gamma (30–44 Hz) frequency bands to estimate the participant's mental state. Real-time auditory neurofeedback is generated (52).

Because the feedback parameters of the MUSE® system are proprietary and not manually adjustable, the indicators “recoveries” and “birds” were recorded as indirect neurofeedback metrics. “Recoveries” represent the number of times the participant successfully refocused attention after distraction, while “birds” indicate sustained periods of calm (≥5 s) as detected by the algorithm.

For the initial sessions, the guided programs Discover Mind Biofeedback and MUSE Essentials were used to introduce participants to mindfulness practice. Beginning with the 17th session, participants transitioned to independent auditory-feedback programs to train self-regulation. Each session began with a 2-min introduction to a theoretical concept or practical tip by a meditation and mindfulness instructor. This was followed by a mindfulness practice with real-time NF and concluded with a 1–2-min reflection on effective tools and sensations.

IG participants attended the NAMTP sessions. Individual adjustments were made within the IG to mindfulness techniques (such as body scanning or breath counting) to optimize attention and engagement. Attendance was recorded according to the protocol, tracking each participant's session sequence to ensure fidelity. No changes were made to the original protocol.

Given that the NF device (MUSE®) is a non-invasive EEG system providing auditory feedback, no serious risks were anticipated. Potential adverse effects included mild skin irritation, headache or fatigue, transient drowsiness, and emotional discomfort or mild anxiety during mindfulness practice. Participants were instructed to report any new or undesirable symptoms, which were then recorded and classified by the research staff according to severity (mild, moderate, severe) and potential relation to the intervention.

The CG received no additional intervention beyond the initial educational workshop.

2.6 Instruments

The primary outcome, anxiety, was assessed using the Depression, Anxiety and Stress Scale 21-item (DASS-21). The Spanish version evaluated emotional states via three 7-item subscales (depression, anxiety, and stress). The presence of adverse mental health symptoms was considered according to the cut-off points proposed by Roman et al. (57) in the validation study with a sample of young people in Spain: DASS-21-Depression ≥6 points, DASS-21-Anxiety ≥6 points, and DASS-21-Stress ≥5 points.

The secondary outcomes were measured using the following scales:

- Smartphone Addiction Scale (SAS-SV): A 10-item tool where scores > 31 indicate smartphone addiction risk. The scale, adapted to Spanish population, has shown excellent internal consistency (α = 0.88) and good construct validity, with a single-factor structure explaining 49.3% of the variance (58).

- Nomophobia Questionnaire (NMP-Q): It is an instrument composed of 20 items. The range of scores varies from 20 to 140 points, with higher scores indicating a greater risk and severity of nomophobia. The Spanish adaptation of the Nomophobia Questionnaire (NMP-Q) showed excellent internal consistency (ordinal α = 0.95) and good test–retest reliability (r = 0.823) (59).

- Athens Insomnia Scale (AIS): This is an 8-item tool that helps in the diagnosis and assessment of insomnia according to ICD-10 diagnostic criteria. Higher scores reflect worse insomnia symptoms. The Spanish adaptation showed good internal consistency (α = 0.86), acceptable test–retest reliability (ICC = 0.75) (60).

All variables were assessed at baseline and 3 months after randomization. For each outcome, the mean and standard deviation were calculated, as well as the difference between the two time points. Statistical analyses were performed to determine whether there were significant differences over time and between groups.

2.7 Data collection procedure and management

A trained nurse was responsible for participant recruitment, scheduling intervention sessions, and data collection at both baseline and 3-month follow-up. Data adherence was monitored through attendance records.

Each participant was assigned a unique identifier to link their records across study visits. Paper records were kept under lock and key at the faculty, while the team compiled electronic records in a private database accessible only to authorized study researchers.

2.8 Ethical considerations

The study was approved by the Clinical Research Ethics Committee of the Salamanca Health Area (CEIm Code: PI 2023 07 1340). All participants provided written informed consent, in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki.

All data were handled in strict compliance with current data protection regulations, including the EU General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR 2016/679) and Spanish legislation: Organic Law 3/2018 on Personal Data Protection and Digital Rights, along with Law 14/2007 on biomedical research. Confidentiality was maintained throughout the study in accordance with these legal frameworks.

2.9 Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was performed according to the study protocol using IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows, version 28.0. An intention-to-treat (ITT) analysis was performed, including all participants regardless of their adherence to the target number of sessions. In cases of missing post-intervention data, available baseline data were used for descriptive analyses, while missing outcome data were excluded from pre–post comparisons. No imputation was planned unless deemed necessary.

Quantitative variables were expressed as mean ± standard deviation, while categorical variables were expressed by number and frequency. The Kolmogorov-Smirnov test was used to test the normality of variables.

Descriptive analyses were conducted using mean difference for quantitative variables and the chi-square test for categorical variables.

The association between variables was analyzed with Student's t-test and analysis of variance (ANOVA). The Student's t-test for independent samples was used to com-pare the means between two groups, evaluating the change within the same group with the Student's t-test for paired data.

A repeated-measures General Linear Model (GLM) was conducted in SPSS to examine changes in anxiety, depression, stress and smartphone addiction, nomophobia and insomnia before and after the intervention, with the group as the between-subjects factor and baseline anxiety scores as a covariate. The model included a within-subjects factor with two levels (pre and post), using Type III sums of squares and a significance level of α =0.05. Profile plots with confidence intervals were generated to visualize group differences, and estimated marginal means were computed adjusted for the covariate, with post-hoc comparisons performed using the LSD correction. In addition, descriptive statistics, effect size (η2), and observed power were obtained to assess the magnitude and reliability of the findings. The statistical significance limit was set at an alpha risk of 0.05.

3 Results

3.1 Participants flow

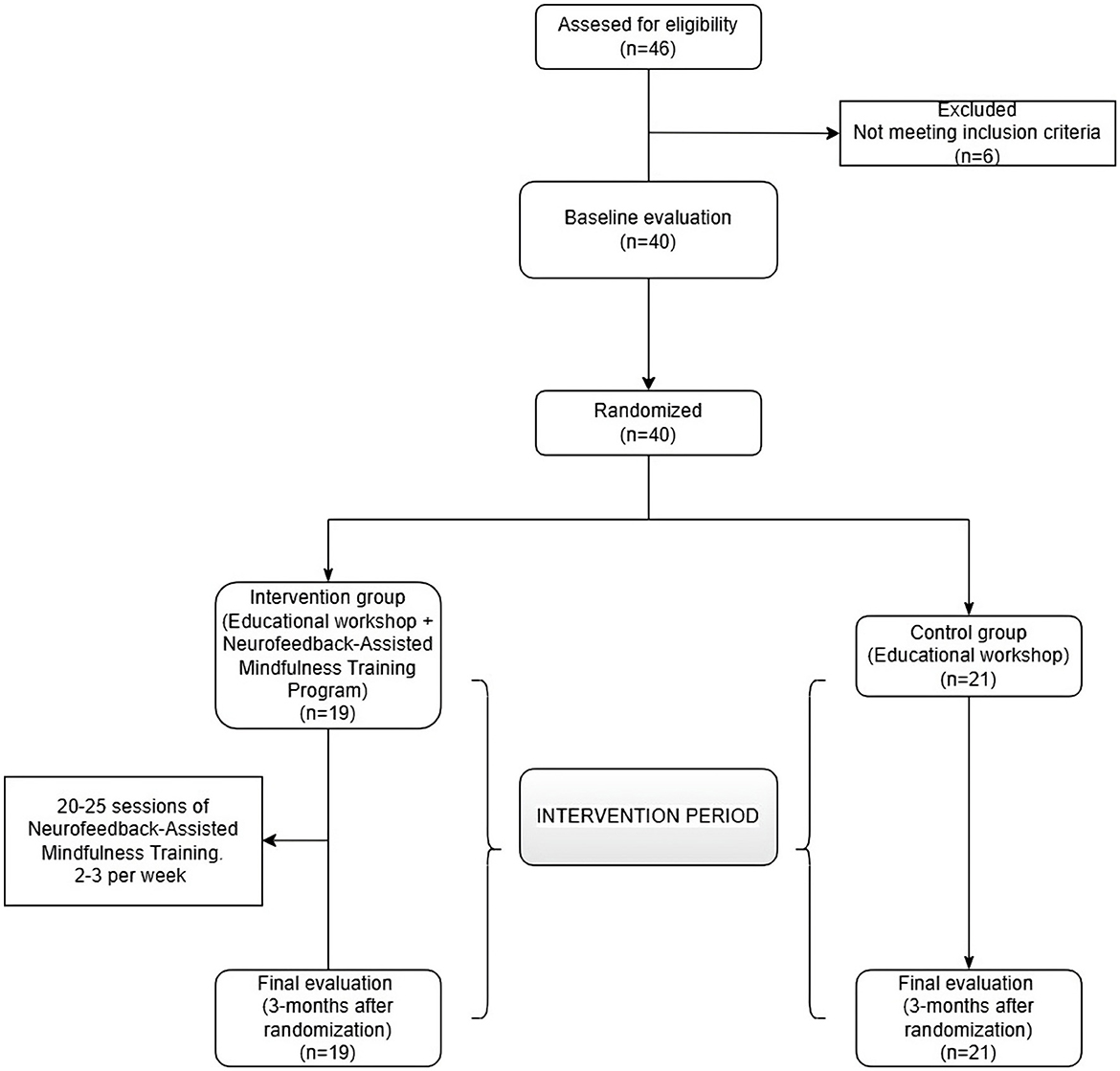

The flow of participants through the study is detailed in Figure 1, in accordance with the CONSORT statement.

Initially, a total of 46 participants were assessed for eligibility, of whom 40 met the inclusion criteria and were randomized. Twenty-one participants were allocated to the CG and 19 to the IG. A single participant from the CG was lost to follow-up, as they did not attend the post-intervention assessment despite repeated contact attempts.

Data from this participant were included in the baseline (pre-intervention) analyses used to characterize the study population but were excluded from the post-intervention comparisons (within- and between-group) due to the absence of outcome data.

3.2 Characteristics of the study population

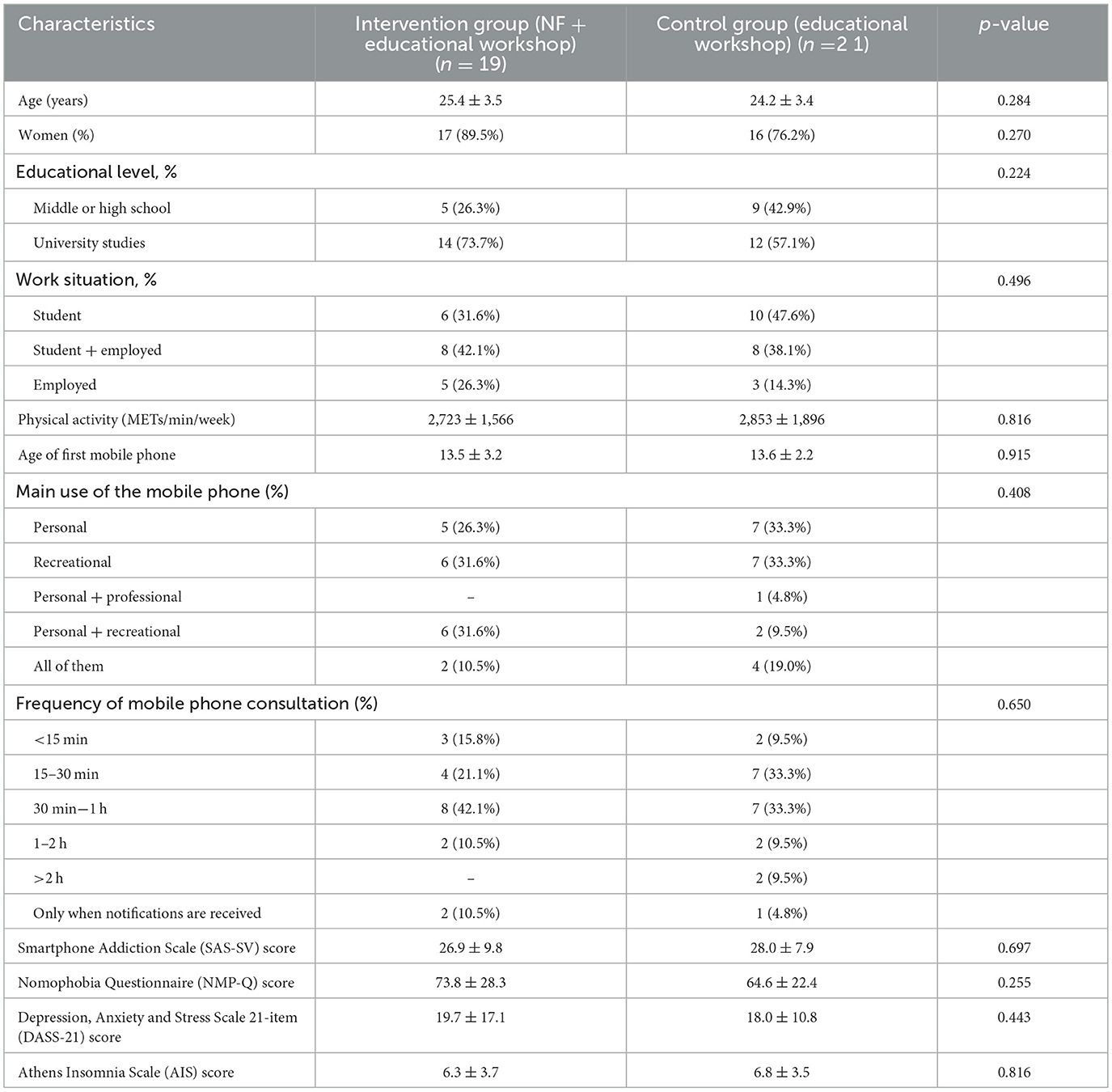

The sample consisted of 40 participants (IG: 19 and CG: 21) (Figure 1). The mean age was 24.8 ± 3.4, and 82.5% of the participants were women. Regarding educational level, 64.1% had university studies, and 80.0% were students, of whom half combined their studies with their work activity. Only 20.0% were exclusively dedicated to work. Table 1 shows the specific characteristics of each group.

The mean age at first use of the mobile phone was 13.6 ± 2.7 years. The main reasons for use were leisure (32.5%), personal use (30.0%), and both purposes equally (20.0%). With regard to the frequency of use, only 22.5% of participants stated not checking their phone every hour, while the remaining participants consulted it at least once per hour.

3.3 Effects of the intervention on anxiety levels and psychological distress

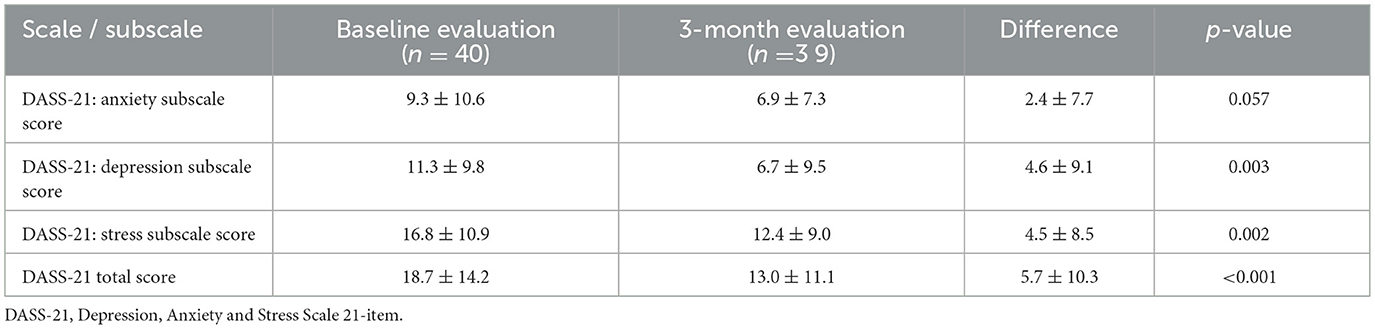

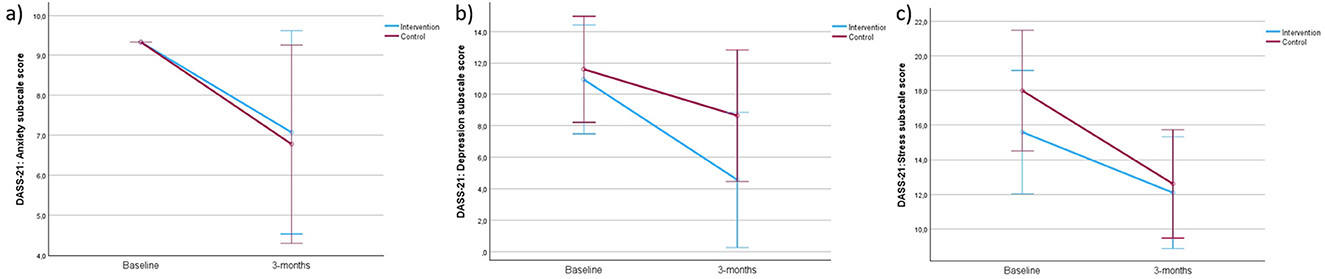

The primary outcome of this study was anxiety, assessed using the anxiety subscale of the DASS-21 scale. In the total sample (CG and IG), anxiety scores decreased by 2.4± 7.7 points at the 3-month follow-up, although this reduction did not reach statistical significance (p = 0.057). Significant decreases, however, were observed in the scores of depression and stress subscales after the intervention, as reported in Table 2.

Figure 2 shows the changes in DASS-21 subscales in both groups from baseline to 3-months follow-up: (a) Results in anxiety, (b) depression and (c) stress. No statistically significant differences were observed between the IG and the CG in any of the psychological variables assessed. For the DASS scales, the mean differences (IG–CG) were 0.1 (95% CI: −1.6 to 1.9; p = 0.868) for anxiety, −2.4 (95% CI: −7.2 to 2.4; p = 0.324) for depression, and −1.5 (95% CI: −5.3 to 2.4; p = 0.453) for stress. Data on effect size are described in the Figure legend. Both groups showed reductions in each DASS-21 subscale scores at 3 months. This indicates that the experimental intervention was no more effective in reducing anxiety than the control intervention.

Figure 2. Changes in the DASS-21 subscales in the control and intervention groups from baseline to 3-month follow-up. (a) Results in anxiety (F = 0.028), (b) depression (F = 0.998), and (c) stress (F = 0.576).

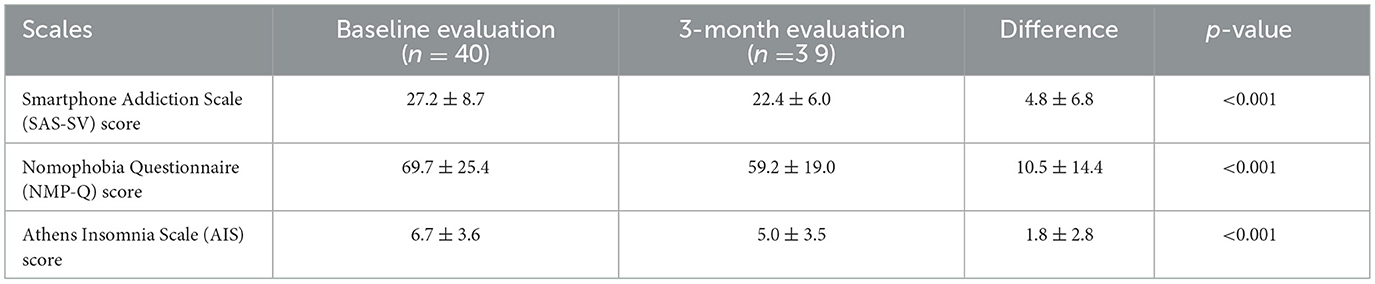

3.4 Effects of the intervention on mobile phone addiction, nomophobia, and insomnia

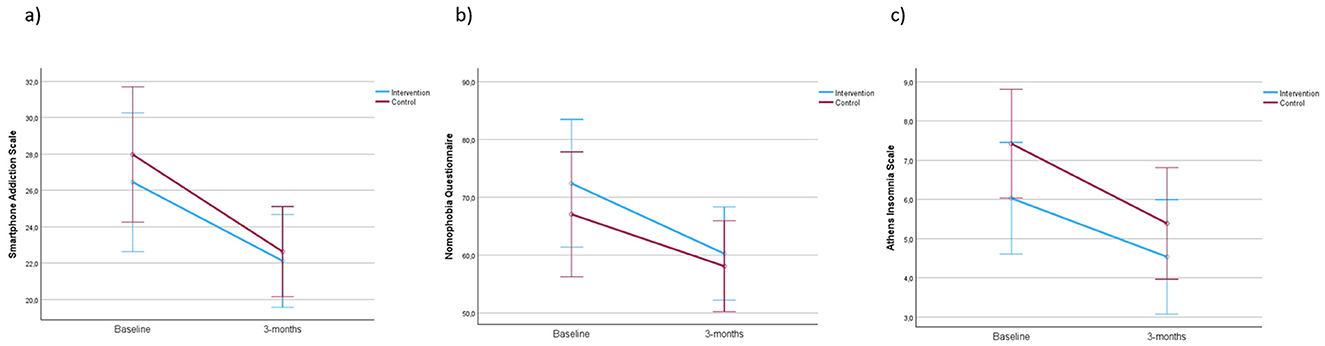

At the 3-month evaluation, statistically significant differences were observed in the other study variables compared to the baseline values in the total sample (Table 3). Mobile phone addiction, assessed with the SAS-SV, showed a mean decrease of 4.8 ± 6.8 points. The levels of nomophobia, measured with the NMP-Q, decreased by 10.5 ± 14.4 points. All were highly significant reductions. Finally, insomnia symptoms assessed with the AIS showed a difference of 1.8 ± 2.8 points.

Figure 3 shows the changes in both groups in smartphone addiction (a), nomophobia (b) and insomnia (c), from baseline to 3-months follow-up. Similarly, the mean difference in the SAS-SV score was −1.0 (95% CI: −5.0 to 2.9; p = 0.606), while for the NMP-Q score it was 3.7 (95% CI: −8.9 to 16.4; p = 0.553). Finally, the AIS showed a mean difference of −1.1 (95% CI: −2.9 to 0.7; p = 0.211). Data on effect size are described in the Figure legend. Both groups showed a similar decrease in SAS-SV (a), nomophobia levels, assessed with NMP-Q (b), and insomnia signs (c).

Figure 3. Changes in the smartphone addiction (a) (F = 0.271), nomophobia (b) (F = 0.358), and insomnia (c) (F = 1.619) scales in the control and intervention groups from baseline to 3-month follow-up.

Although both groups showed improvement at 3 months on each variable, there was insufficient evidence to demonstrate that the NAMTP techniques were more effective compared to the educational workshop.

3.5 Adherence to the neurofeedback intervention

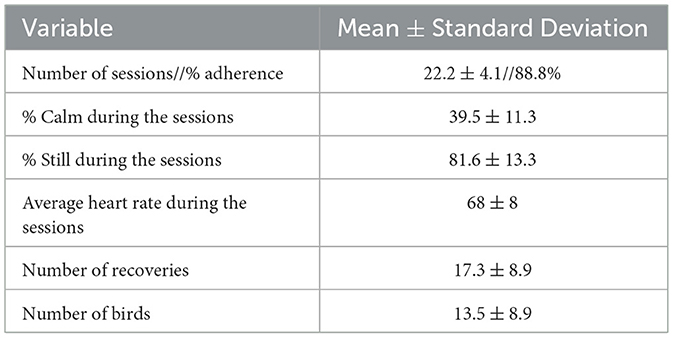

The IG was composed of 19 participants. Table 4 shows adherence and intervention data. Adherence to the program was 88.8%, with a mean of 22.2 ± 4.1 completed sessions. A correlation analysis has been performed, showing no differences between adherence to the sessions and the outcomes analyzed. No adverse events related to either intervention were reported during the study period. The MUSE® device monitored the time in which the mind remains in a calm state, recording an average of 39.5% of the session time, with an SD of 11.3%. In this group, a mean of 17.3 ± 8.9 recoveries and 13.5 ± 8.9 birds was observed. A correlation analysis has been performed, showing no differences between bird counts and the outcomes analyzed.

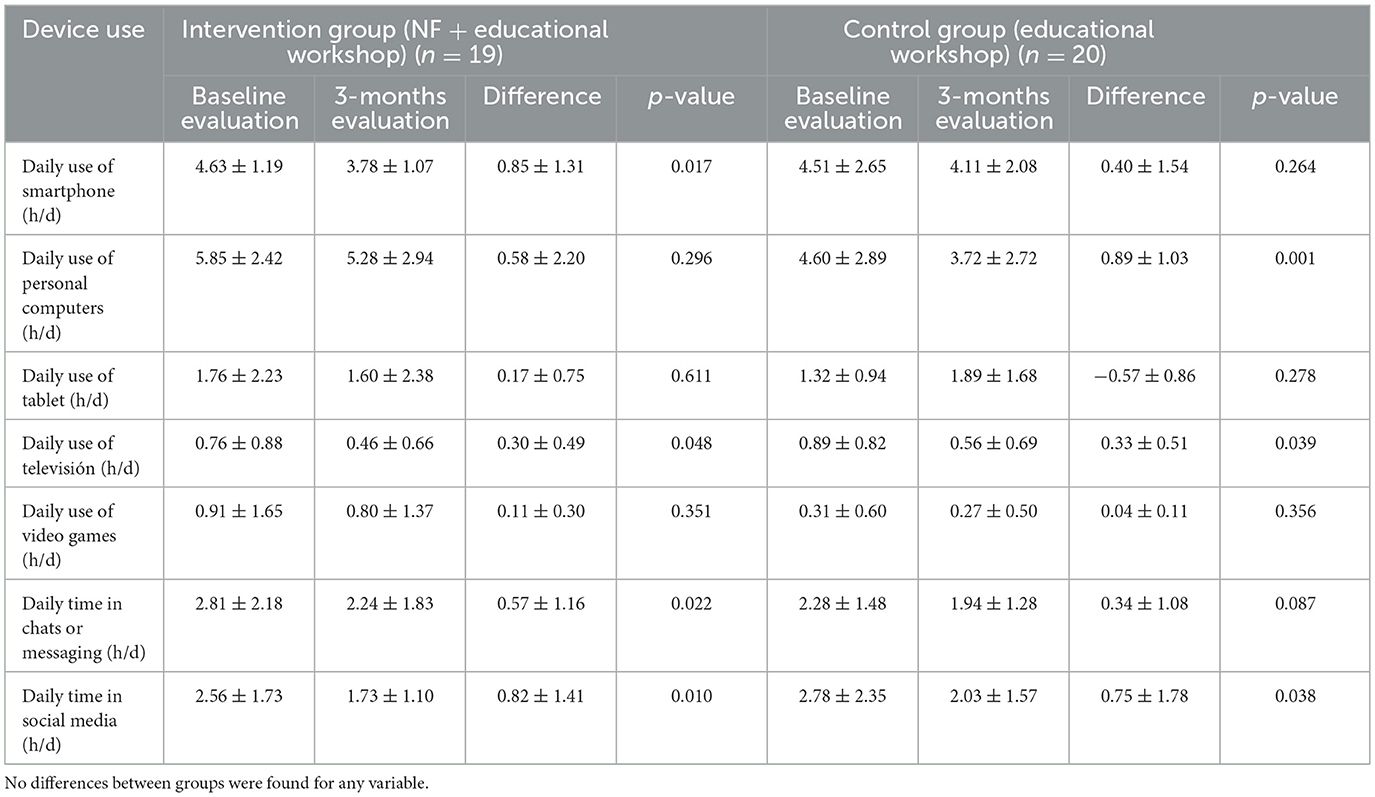

3.6 Self-reported use of technologies and social media

Regarding the time spent using new technologies, the most frequently used devices were the smartphone (mean use of 4.28 ± 2.18 h/day) and the computer (5.37 ± 3.15 h/day). In relation to habitual patterns of use, participants reported spending more time on social media (2.68 ± 2.08 h/day) and chatting or messaging (2.55 ± 1.83 h/day). Although a reduction in screen time was observed in both groups at the 3-month assessment, no statistically significant differences were found between them (p > 0.05).

For the IG, significant differences were found in daily smartphone use (p = 0.017), time in front of the TV (p = 0.048) and time spent chatting (p = 0.022), indicating that the intervention effectively influenced participants' behavior in these domains. Statistically significant decreases in computer (p = 0.001) and TV (p = 0.039) use were also observed for the CG. Both groups showed a significant reduction, at 3 months, in the use of social media, indicating that both the workshop and NF were effective on their own. These results suggest that adding NAMTP enhanced the overall impact on participants' digital habits and routines. However, it cannot be stated that one offered greater effectiveness over the other (Table 5).

4 Discussion

4.1 Principal's findings

The primary objective of this study was to evaluate the effectiveness of a NAMTP in reducing anxiety related to the use of new technologies in young Spanish adults. In this study, NAMTP did not lead to significant improvements in anxiety, mobile phone addiction, nomophobia, or sleep quality compared to CG.

Our findings partially coincide with previous research, such as a clinical trial that found the long-term benefits of NF in improving anxiety and depression may be time limited (61). In the context of internet addiction, a South Korean study found that a mobile NF program improved addiction levels but no significant changes in neurocognitive functions (42). In contrast, research conducted in Georgia reported improvements in different components of attention in children with internet addiction disorders, suggesting that NF could influence key brain regions involved in ADHD and IAD, such as the prefrontal cortex, caudate nucleus, and thalamus (48).

An active CG was selected over a no-treatment or standard care CG for several reasons. Considering the multiple studies highlighting mental and physical issues among young people (12, 15, 62), it was considered ethically inappropriate to withhold a basic preventive measure from the CG. Furthermore, the workshop was designed as a preventive, health-promoting intervention aimed at educating participants on responsible technology use, functioning as a public health measure even for a non-clinical population. The primary goal of the study, however, was to explore the effectiveness of NAMTP rather than to determine its superiority over the workshop. In addition, gold-standard conventional treatment has not yet been established for this emerging field. Finally, providing some form of intervention for all participants was considered beneficial for improving recruitment and retention rates, which often represent a challenge in clinical trials involving volunteer populations.

It should be noted that the studies reviewed use highly heterogeneous NF protocols, varying in the number of sessions, program duration, and the type of technology used (mobile devices vs. clinical equipment). This lack of standardization hinders direct comparison between studies and limits the generalizability of the results. In addition, much of the existing literature originates from Eastern countries, underscoring the need for further research in Western populations, where different cultural and environmental factors may influence the effectiveness of NF.

The current body of NF research presents several methodological limitations that constrain the reliability and generalizability of published findings. Systematic reviews of fMRI-NF and fNIRS-NF studies have identified substantial underpowering, with median statistical power estimates as low as 21–22% for detecting moderate clinical effects. Such underpowering likely contributes to an excess of reported significance, potentially due to selective analysis or reporting bias (63).

Even in laboratory-based mindfulness neurofeedback—where participants can modulate neural targets such as the Default Mode Network (DMN) and frontal midline theta—mechanistic claims remain weak, largely due to the frequent absence of appropriate sham control conditions (64). Outside the laboratory, it also remains unclear what specific brain mechanisms consumer-grade devices target and, consequently, why or how they should alter psychological states. A recent meta-analysis found only modest improvements in psychological distress (Hedges g ≈ −0.16 to −0.29), with no correlation between device-derived EEG metrics (e.g., Muse's “calm” score) and mindfulness or mental health outcomes. This pattern supports the interpretation that the reported benefits may primarily reflect neurosuggestion rather than genuine neural modulation. Users' expectations and the perceived scientific credibility of neurotechnological devices appear to play a substantial role in shaping subjective outcomes (65).

Regarding daily use of the new technologies, one study found that longer screen exposure time is associated with an increased risk of anxiety and depression (66); and that spending more than 3 h per day on social media doubles the risk of mental problems, according to a report by the American Psychological Association (67). In our sample, participants reported between 4 and 6 h daily in front of smartphones and computers, with an average use of social media of 2.68 ± 2.08 h/day, mainly for personal or entertainment purposes. These data coincide with reports from the National Institute of Statistics (INE) of Spain, which places communication, entertainment, and information as the most frequent activities carried out on the Internet among the Spanish population (68).

With regard to sleep, a systematic review found that excessive use of social media is associated with poorer sleep quality, reduced sleep duration, increased difficulty falling asleep, and a higher risk of depression among young people (69). In addition, using screens during the last hour before bedtime has been associated with sleep interruptions (70). In this context, 97.5% of the study participants reported using a mobile phone within 2 h before bedtime, and 57.5% took between 30 min and 2 h to fall asleep. The initial AIS score was higher than 6, indicating the presence of clinically relevant insomnia in part of the sample. Although there was improvement in the AIS score at 3 months in the IG, as observed in other studies, NF has not demonstrated objective clinical efficacy, although subjective improvements have been found (43, 44).

4.2 Limitations

This study has several limitations that should be considered when interpreting the results. First, as a single-center study, our results may not be generalizable to other populations. In addition, the sample was predominantly female, with university studies and in an active academic or work situation, which limits the ability to generalize the findings to male populations or others with different sociocultural contexts.

Another significant limitation was that the methodological design did not allow us to completely isolate the specific effect of the NAMTP since both groups received minimal educational intervention, which could dilute the differences between the groups. Also, due to the nature of the intervention, it was not possible to blind either the participants or the researchers. The lack of blinding may have introduced performance bias, as participants' awareness of their group allocation and the expectations of the nurse could have influenced the results.

In addition to the previous limitations, the absence of a “no-treatment” group makes it impossible to determine whether the positive effects observed in both groups were due to the intervention, the workshop, or a placebo effect. Furthermore, the use of a general anxiety scale (DASS-21) rather than a scale specifically designed to measure anxiety related to the use of new technologies may have limited our ability to isolate and accurately measure the specific impact of the intervention.

Finally, the lack of standardization in NF protocols reported in the literature, as well as the paucity of studies in Western contexts, limits direct comparison and applicability of the findings to other populations and clinical settings.

4.3 Implications for practice and future research

The findings of this study underscore the need to view problematic technology use not merely as an acute issue but as a chronic condition requiring long-term management within clinical practice. This study suggests that simple psychoeducational support, delivered in primary care and community settings, was considerably effective.

Future research should prioritize methodological rigor through adequately powered randomized controlled trials (n ≈ 100 for medium effects), employing consistent control conditions and standardized NF protocols. However, enhancing methodological consistency alone may not be sufficient. Integrating psychoeducational components and social scaffolds—such as guided reflection, peer support, and instructor-led elements—could improve adherence and facilitate a deeper understanding of mindfulness principles.

If the broader aim is to promote a rational and health-conscious use of these technologies, the most impactful future direction may lie in public health education. The goal is not to discourage their use, but to encourage users to engage with them in a mindful, critical, and responsible way. Educational initiatives that raise awareness about both the potential benefits and limitations of these technologies could help ensure they are used to support wellbeing rather than contribute to excessive or unreflective use.

5 Conclusions

The NAMTP did not demonstrate significant improvements in reducing anxiety, mobile phone addiction, or nomophobia. No significant effects were observed on sleep quality either. These findings suggest that, although NAMTP may be a feasible and well-tolerated intervention, further research with larger samples and consistent control conditions is needed to determine its potential benefits for anxiety reduction and behavioral regulation related to technology use.

Data availability statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/supplementary material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Ethics statement

The studies involving humans were approved by Clinical Research Ethics Committee of the Salamanca Health Area. The studies were conducted in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. The participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study.

Author contributions

MF-C: Conceptualization, Investigation, Methodology, Writing – original draft. MR-G: Conceptualization, Funding acquisition, Methodology, Resources, Supervision, Writing – review & editing. NS-A: Formal analysis, Writing – review & editing. NS-S: Investigation, Writing – review & editing. JG-S: Data curation, Writing – review & editing. IG-Y: Data curation, Writing – review & editing. H-CL: Supervision, Writing – review & editing. JR-R: Conceptualization, Funding acquisition, Methodology, Project administration, Resources, Supervision, Validation, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declare that financial support was received for the research and/or publication of this article. This research was funded by Gerencia Regional de Salud de Castilla y Leon, Spain (GRS2709/A1/2023) and Instituto de Investigación Biomédica de Salamanca-IBSAL (IBYE23_00001 and IBYP24_00001). Neither of the two institutions had authority in the study design, data collection, management, analysis, or interpretation.

Acknowledgments

The researchers would like to thank the following institutions: To all the participants of the study and to the professors and researchers of the University of Salamanca who made it possible, to the José Castillejo Foreign Mobility Stays Program for young PhDs, call 2022 (CAS22/00084) of the Ministry of Science, Innovation and Universities of the Government of Spain. Finally, to the Taiwan Fellowship Program of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs of the Republic of China (Taiwan).

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The author(s) declare that Gen AI was used in the creation of this manuscript. The author(s) acknowledge the use of generative artificial intelligence (Gemini 2.5. Flash, Google; ChatGPT-5, OpenAI) to support the improvement of language, clarity, and structure in the writing process. Final content was reviewed and approved by all authors.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Publisher's note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Abbreviations

ADHD, Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder; AIS, Athens Insomnia Scale; CG, Control group; CI, Confidence Interval; DASS-21, Depression, Anxiety and Stress Scale 21-item; IG, Intervention group; NAMTP, Neurofeedback-Assisted Mindfulness Training Program; NF, Neurofeedback; PSU, Problematic Smartphone Use; SAS-SV, Smartphone Addiction Scale.

References

1. Balhara YPS, Mahapatra A, Sharma P, Bhargava R. Problematic internet use among students in South-East Asia: current state of evidence. Indian J Public Health. (2018) 62:197. doi: 10.4103/ijph.IJPH_288_17

2. Solon LJF, Tomaz CH, de Sousa L, Teixeira B, da Silva LV. Smartphone addiction is associated with symptoms of anxiety, depression, stress, tension, confusion, and insomnia: a cross-sectional and comparative study with physically and non-physically active adults in self-isolation during the COVID-19 pandemic. Salud Ment. (2021) 44:193–200. doi: 10.17711/SM.0185-3325.2021.025

3. Zhang J, Zhang X, Zhang K, Lu X, Yuan G, Yang H, et al. An updated of meta-analysis on the relationship between mobile phone addiction and sleep disorder. J Affect Disord. (2022) 305:94–101. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2022.02.008

4. Santl L, Brajkovic L, Kopilaš V. Relationship between nomophobia, various emotional difficulties, and distress factors among students. Eur J Investig Health Psychol Educ. (2022) 12:716–30. doi: 10.3390/ejihpe12070053

5. Abdulsalim S, Anaam MS, Farooqui M, Alshammari MS, Alfadly S, Alolayan J, et al. Evaluation of social media addiction and its relationship with anxiety and academic performance among medical and non-medical students: a cross-sectional study from Saudi Arabia. Healthcare. (2025) 13:295. doi: 10.3390/healthcare13030295

6. Observatorio Nacional de Tecnología y Sociedad; Digital Future Society. Impacto del aumento del uso de Internet y las redes sociales en la salud mental de jóvenes y adolescentes (2023). Available online at: https://consaludmental.org/centro-documentacion/impacto-internet-redes-sociales-salud-mental-jovenes/ (Accessed May 29, 2025).

7. Arshad D, Joyia UM, Fatima S, Khalid N, Rishi AI, Abdul Rahim NU, et al. The adverse impact of excessive smartphone screen-time on sleep quality among young adults: a prospective cohort. Sleep Sci. (2021) 14:337. doi: 10.5935/1984-0063.20200114

8. Lourenço Silva R, Couto Gonçalves BP, Lourenço Ferreira MH, Carvas Junior N. Consequences of screen time on sleep quality in children and adolescents: a scoping review. J Pediatr Health Care. (2025). doi: 10.1016/j.pedhc.2025.08.005

9. Carter B, Rees P, Hale L, Bhattacharjee D, Paradkar MS. Association between portable screen-based media device access or use and sleep outcomes: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA Pediatr. (2016) 170:1202–8. doi: 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2016.2341

10. Babakhani D, Shojaei A. Pourroshan zad E, Kazemi M, Foroughi AA. From nighttime and daytime smartphone use to negative emotions in adults: the pathway through sleep indicators and event importance. Comput Hum Behav Rep. (2025) 20:100826. doi: 10.1016/j.chbr.2025.100826

11. He JW, Tu ZH, Xiao L, Su T, Tang YX. Effect of restricting bedtime mobile phone use on sleep, arousal, mood, and working memory: a randomized pilot trial. PLoS ONE. (2020) 15:e0228756. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0228756

12. Saleem N, Young P, Yousuf S. Exploring the relationship between social media use and symptoms of depression and anxiety among children and adolescents: a systematic narrative review. Cyberpsychol Behav Soc Netw. (2024) 27:771–97. doi: 10.1089/cyber.2023.0456

13. Elhai JD, Levine JC, Hall BJ. The relationship between anxiety symptom severity and problematic smartphone use: a review of the literature and conceptual frameworks. J Anxiety Disord. (2019) 62:45–52. doi: 10.1016/j.janxdis.2018.11.005

14. Elhai JD, Levine JC, Hall BJ. Problematic smartphone use and mental health problems: current state of research and future directions. J Psychiatry Neurol Sci. (2019) 32:1–3. doi: 10.14744/DAJPNS.2019.00001

15. Sohn SY, Rees P, Wildridge B, Kalk NJ, Carter B. Prevalence of problematic smartphone usage and associated mental health outcomes amongst children and young people: a systematic review, meta-analysis and GRADE of the evidence. BMC Psychiatry. (2019) 19:356. doi: 10.1186/s12888-019-2350-x

16. Hua Z, Ji Y, Han X. Metacognition mediates the relationship between anxiety and smartphone addiction in university students. Sci Rep. (2025) 15:33348. doi: 10.1038/s41598-025-14799-y

17. Terán A. Ciberadicciones: Adicción a las nuevas tecnologías (NTIC). Madrid, Spain: Congreso actualización pediatría (2019).

18. Adelhardt Z, Markus S, Eberle T. Teenagers' reaction on the long-lasting separation from smartphones, anxiety and fear of missing out. ACM Int Conf Proc SeR. (2018) 18:212–6. doi: 10.1145/3217804.3217914

19. Mishra J, Bahera MR, Samanta P, Kar S, Mahapatra P, Pattnaik JI, et al. Prevalence of internet addiction and its association with lifestyle factors among university students: a pilot study in Eastern India. Cureus. (2025) 17:85061. doi: 10.7759/cureus.85061

20. Pedrini B, Dumith SC, Pereira M. Prevalence and factors associated with problematic use of smartphone in high school students from southern Brazil. Cad Saude Publica. (2025) 41:e00140024. doi: 10.1590/0102-311XEN140024

21. Jahrami H, Trabelsi K, Boukhris O, Hussain JH, Alenezi AF, Humood A, et al. The prevalence of mild, moderate, and severe nomophobia symptoms: a systematic review, meta-analysis, and meta-regression. Behav Sci. (2023) 13:35. doi: 10.3390/bs13010035

22. Ceobanu CM, Marian AL, Apostolache R. Glimpse on 21st century new phobias; a predictive model of nomophobia. Front Public Health. (2023) 11:1252099.

23. Zhang X, Zhang J, Zhang K, Ren J, Lu X, Wang T, et al. Effects of different interventions on internet addiction: a meta-analysis of random controlled trials. J Affect Disord. (2022) 313:56–71. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2022.06.013

24. Liu F, Zhang Z, Liu S, Feng Z. Effectiveness of brief mindfulness intervention for college students' problematic smartphone use: the mediating role of self-control. PLoS ONE. (2022) 17:e0279621. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0279621

25. Cheng SS, Zhang CQ, Wu JQ. Mindfulness and smartphone addiction before going to sleep among college students: the mediating roles of self control and rumination. Clocks Sleep. (2020) 2:354–63. doi: 10.3390/clockssleep2030026

26. Navarro-Gil M, Escolano-Marco C, Montero-Marín J, Minguez-Zafra J, Shonin E, García-Campayo J. Efficacy of neurofeedback on the increase of mindfulness related capacities in healthy individuals: a controlled trial. Mindfulness (N Y). (2018) 9:303–11. doi: 10.1007/s12671-017-0775-1

27. Liu Q, Yang X, Zhang C, Xiong J. Is decreasing problematic mobile phone use a pathway for alleviating adolescent depression and sleep disorders? A randomized controlled trial testing the effectiveness of an eight-session mindfulness-based intervention. J Behav Addict. (2024) 13:525–41. doi: 10.1556/2006.2024.00034

28. Zhang Z, Wu L, Lu C, Guan T. Effectiveness of brief online mindfulness-based intervention on different types of mobile phone addiction: mechanisms of influence of trait mindfulness. Front. Psychol. (2025) 16:1400327. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2025.1400327

29. Li J, Wang D, Bai S, Yang W. The effect of mindfulness-based Tai Chi Chuan on mobile phone addiction among male college students is associated with executive functions. PLoS ONE. (2025) 20:e0314211. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0314211

30. Guo W, Nazari N, Sadeghi M. Cognitive-behavioral treatment for insomnia and mindfulness-based stress reduction in nurses with insomnia: a non-inferiority internet delivered randomized controlled trial. PeerJ. (2024) 12:e17092. doi: 10.7717/peerj.17491

32. Marzbani H, Marateb HR, Mansourian M. Neurofeedback: a comprehensive review on system design, methodology and clinical applications. Basic Clin Neurosci. (2016) 7:143–58. doi: 10.15412/J.BCN.03070208

33. Fajardo A, Guzmán AL. Neurofeedback, aplicaciones y eficacia. Interdis. (2016) 33:81–93. doi: 10.16888/interd.2016.33.1.5

34. Banerjee S, Argáez C. Neurofeedback and Biofeedback for Mood and Anxiety Disorders: A Review of Clinical Effectiveness and Guidelines (2017). p. 1–26.

35. Abdian H, Rezaei M, Eskandari Z, Ramezani S, Pirzeh R, Dadashi M. The effect of quantitative electroencephalography based neurofeedback therapy on anxiety, depression, and emotion regulation in people with generalized anxiety disorder. Basic Clin Neurosci. (2021) 12:281–90. doi: 10.32598/bcn.12.2.2378.1

36. Wan H, Chen B, Li X, Bu J. Effect of EEG neurofeedback therapy on addiction disorders: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Addiction. (2025) 1–14. doi: 10.1111/add.70164

37. Choi JS, Park SM, Lee J, Hwang JY, Jung HY, Choi SW, et al. Resting state beta and gamma activity in internet addiction. Int J Psychophysiol. (2013) 89:328–33. doi: 10.1016/j.ijpsycho.2013.06.007

38. Qi Y, Liu Y, Yan Z, Hu S, Zhang X, Zhao J, et al. Slow wave EEG activity correlates with impaired inhibitory control in internet addiction disorder. Int J Environ Res Public Health. (2022) 19:2686. doi: 10.3390/ijerph19052686

39. Jande J, Treves IN, Ely SL, Gowatch LC, Carpenter C, Shampine M, et al. Mindful young brains and minds: a systematic review of the neural correlates of mindfulness-based interventions in youth. Brain Imaging Behav. (2025) 19:609–25.

40. Yu X, Cohen ZP, Tsuchiyagaito A, Cochran G, Aupperle RL, Stewart JL, et al. Neurofeedback-augmented mindfulness training elicits distinct responses in the subregions of the insular cortex in healthy adolescents. Brain Sci. (2022) 12:363.

41. Kirlic N, Cohen ZP, Tsuchiyagaito A, Misaki M, McDermott TJ, Aupperle RL, et al. Self-regulation of the posterior cingulate cortex with real-time fMRI neurofeedback augmented mindfulness training in healthy adolescents: a nonrandomized feasibility study. Cogn Affect Behav Neurosci. (2022) 22:849–67. doi: 10.3758/s13415-022-00991-4

42. Choi JW, Yang S, Kim JW. Impact of mobile neurofeedback on internet addiction and neurocognitive function in neurotypical children: double blind, sham controlled randomized clinical trial. Neuropsychiatr Dis Treat. (2024) 20:1097–106. doi: 10.2147/NDT.S454881

43. Lu TH, Hsieh TH, Wang YH, Shaw FZ, Chen PS, Liang SF. Evaluation of alpha neurofeedback training to enhance sleep in remitted depression and anxiety sufferers with persistent insomnia. Psychiatry Res. (2025) 346:115258. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2025.116401

44. Recio-Rodriguez JI, Fernandez-Crespo M, Sanchez-Aguadero N, Gonzalez-Sanchez J, Garcia-Yu IA, Alonso-Dominguez R, et al. Neurofeedback to enhance sleep quality and insomnia: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized clinical trials. Front Neurosci. (2024) 18:1450163. doi: 10.3389/fnins.2024.1450163

45. Pamplona GSP, Zweerings J, Lor CS, deErney L, Roecher E, Taebi A, et al. Neural mechanisms of feedback processing and regulation recalibration during neurofeedback training. Hum Brain Mapp. (2025) 46:e70279. doi: 10.1002/hbm.70279

46. Hopewell S, Chan AW, Collins GS, Hróbjartsson A, Moher D, Schulz KF, et al. CONSORT (2025). Statement: updated guideline for reporting randomised trials. BMJ. (2025) 388:e081123. doi: 10.1136/bmj-2024-081123

47. Fernandez-Crespo M, Recio-Rodriguez JI, Lee HC, Alonso-Dominguez R, Montejo AL, Hernandez-Gonzalez L, et al. Study protocol of a proposed Neurofeedback-Assisted Mindfulness Training Program on symptoms of anxiety and psychological distress associated with smartphone use in young adults: a randomized controlled trial. Front Public Health. (2024) 12:1410932. doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2024.1410932

48. Nadiradze T, Bakhtadze S, Kvachadze I, Khachapuridze N. Use of neurofeedback to alter attention parameters in children with internet addiction disorder. Georgian Biomed News. (2024) 2:77. doi: 10.52340/GBMN.2024.01.01.77

49. Hayes HB, Magne C. Exploring the utility of the muse headset for capturing the N400: dependability and single-trial analysis. Sensors (Basel). (2024) 24:7961. doi: 10.3390/s24247961

50. Sabio J, Williams NS, McArthur GM, Badcock NA, A. scoping review on the use of consumer-grade EEG devices for research. PLoS ONE. (2024) 19:e0291186. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0291186

51. Krigolson OE, Williams CC, Norton A, Hassall CD, Colino FL. Choosing MUSE: validation of a low-cost, portable EEG system for ERP research. Front Neurosci. (2017) 11:243179. doi: 10.3389/fnins.2017.00109

52. Muse. (n.d.). Muse Health and Safety. Available online at: https://choosemuse.com/muse-2/ (Accessed January 9, 2023).

53. Krigolson OE, Hammerstrom MR, Abimbola W, Trska R, Wright BW, Hecker KG, et al. Using muse: rapid mobile assessment of brain performance. Front Neurosci. (2021) 15:634147. doi: 10.3389/fnins.2021.634147

54. Hayes HB, Magne CL. Dataset of 37-subject EEG recordings using a low-cost mobile EEG headset during a semantic relatedness judgment task. Data Brief. (2025) 59:111390. doi: 10.1016/j.dib.2025.111390

55. Hunkin H, King DL, Zajac IT. Evaluating the feasibility of a consumer-grade wearable EEG headband to aid assessment of state and trait mindfulness. J Clin Psychol. (2021) 77:2559–75. doi: 10.1002/jclp.23189

56. Hawley LL, Rector NA, DaSilva A, Laposa JM, Richter MA. Technology supported mindfulness for obsessive compulsive disorder: self-reported mindfulness and EEG correlates of mind wandering. Behav Res Ther. (2021) 136:103757. doi: 10.1016/j.brat.2020.103757

57. Román F, Santibáñez P, Vinet E. Uso de las Escalas de Depresión Ansiedad Estrés (DASS-21) como instrumento de tamizaje en jóvenes con problemas clínicos. Acta Investig Psicol. (2016) 6:2325–36. doi: 10.1016/S2007-4719(16)30053-9

58. Lopez-Fernandez O. Short version of the smartphone addiction scale adapted to spanish and french: towards a cross-cultural research in problematic mobile phone use. Addict Behav. (2017) 64:275–80. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2015.11.013

59. González-Cabrera J, León-Mejía A, Pérez-Sancho C, Calvete E. Adaptation of the Nomophobia Questionnaire (NMP-Q) to Spanish in a sample of adolescents. Actas Esp Psiquiatr. (2017) 45:137–44.

60. Gómez-Benito J, Ruiz C, Guilera G, A. Spanish version of the Athens Insomnia Scale. Qual Life Res. (2011) 20:931–7. doi: 10.1007/s11136-010-9827-x

61. Jing S, Dai Z, Liu X, Yang X, Cheng J, Chen T, et al. Effectiveness of neurofeedback-assisted and conventional 6-week web-based mindfulness interventions on mental health of Chinese nursing students: randomized controlled trial. J Med Internet Res. (2025) 27:e71741. doi: 10.2196/71741

62. Yang J, Fu X, Liao X, Li Y. Association of problematic smartphone use with poor sleep quality, depression, and anxiety: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Psychiatry Res. (2020) 284:112686. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2019.112686

63. Thibault RT, Pedder H. Excess significance and power miscalculations in neurofeedback research. Neuroimage Clin. (2022) 35:103008. doi: 10.1016/j.nicl.2022.103008

64. Treves IN, Greene KD, Bajwa Z, Wool E, Kim N, Bauer CCC, et al. Mindfulness-based neurofeedback: a systematic review of EEG and fMRI studies. Imaging Neurosci. (2024) 2:1–25. doi: 10.1101/2024.09.12.612669

65. Treves I, Bajwa Z, Greene KD, Bloom PA, Kim N, Wool E, et al. Consumer-grade neurofeedback with mindfulness meditation: meta-analysis. J Med Internet Res. (2025) 27:e68204. doi: 10.2196/68204

66. Li X, Vanderloo LM, Keown-Stoneman CDG, Cost KT, Charach A, Maguire JL, et al. Screen use and mental health symptoms in Canadian children and youth during the COVID-19 pandemic. JAMA Netw Open. (2021) 4:e2140875. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2021.40875

67. American Psychological Association. Social Media and Youth Mental Health. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (2023). Available online: https://www.hhs.gov/surgeongeneral/reports-and-publications/youth-mental-health/social-media/index.html (Accessed June 1, 2025).

68. Instituto Nacional de Estadística. Encuesta sobre Equipamiento y Uso de TIC en los Hogares 2022. Madrid: INE (2022). Available online at: https://www.ine.es/prensa/tich_2022.pdf (Accessed June 1, 2025).

69. Alonzo R, Hussain J, Stranges S, Anderson KK. Interplay between social media use, sleep quality, and mental health in youth: a systematic review. Sleep Med Rev. (2021) 56:101414. doi: 10.1016/j.smrv.2020.101414

70. Hamilton JL, Chand S, Reinhardt L, Ladouceur CD, Silk JS, Moreno M, et al. Social media use predicts later sleep timing and greater sleep variability: an ecological momentary assessment study of youth at high and low familial risk for depression. J Adolesc. (2020) 83:122–30. doi: 10.1016/j.adolescence.2020.07.009

Keywords: neurofeedback, mindfulness, anxiety, nursing, young adults, randomized controlled trial

Citation: Fernandez-Crespo M, Rihuete-Galve MI, Sanchez-Aguadero N, Sanchez-Sanchez N, Gonzalez-Sanchez J, Garcia-Yu IA, Lee H-C and Recio-Rodriguez JI (2025) Efficacy of neurofeedback-assisted mindfulness for anxiety and nomophobia in Spanish young adults: a randomized controlled trial. Front. Public Health 13:1712564. doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2025.1712564

Received: 24 September 2025; Revised: 10 November 2025;

Accepted: 13 November 2025; Published: 02 December 2025.

Edited by:

Gabriela Marcu, Lucian Blaga University of Sibiu, RomaniaReviewed by:

Limor Shtoots, Reichman University, IsraelIsaac Treves, Massachusetts Institute of Technology, United States

Copyright © 2025 Fernandez-Crespo, Rihuete-Galve, Sanchez-Aguadero, Sanchez-Sanchez, Gonzalez-Sanchez, Garcia-Yu, Lee and Recio-Rodriguez. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Mei Fernandez-Crespo, bWVpZmRlekB1c2FsLmVz

Mei Fernandez-Crespo

Mei Fernandez-Crespo M. Isabel Rihuete-Galve1,2,4

M. Isabel Rihuete-Galve1,2,4 Irene A. Garcia-Yu

Irene A. Garcia-Yu Hsin-Chien Lee

Hsin-Chien Lee Jose I. Recio-Rodriguez

Jose I. Recio-Rodriguez