- Lund University Center for Sustainability Studies, Lund, Sweden

This article combines insights from two emerging literatures on transnational private regulation: the grounding perspective and politics and power in global value chains. Drawing on a case study conducted in Turkey, it examines political economy of voluntary sustainability standards in hazelnut production, a critical but overlooked part of the chocolate value chain with no shortage of human rights scandals. Focusing on smallholders and migrant workers, it problematizes the decent work programmes of transnational private governance systems. In Turkey, the agricultural labour market is ethnically segregated, and agricultural work is carried out by seasonal migrant workers belonging to the country’s Kurdish and Arab minorities and refugees, mainly from Syria. Decent work programmes focus on these workers. Through an analysis of the roles of actors (the state, corporations, exporters, local merchants, producers, workers, and third-party certifiers) in the financialized hazelnut market, I demonstrate that farmers and workers cannot sufficiently benefit from transnational private governance programmes due to political power dynamics, market structure, and price volatility at the nation-state level. I argue that any effort to assess the impact of private-led social justice schemes in food production must include a thorough analysis of country conditions, societal conflicts, power asymmetries, and the structure of the commodity market.

1 Introduction

Decent work is a key pillar of the Sustainable Development Goals, and therefore of sustainable food systems. As the eighth target of SDG 8 clearly emphasises, we must ‘Protect labour rights and promote safe and secure working environments for all workers, including migrant workers, especially women migrants, and those in precarious employment’ (United Nations, n.d.). However, global food systems are increasingly converging with a growing need for hired labour and deteriorating working conditions (King et al., 2021; Corrado et al., 2017), occasionally erupting into scandals of child and forced labour practices, inhumane working conditions and poor pay, raising serious social justice issues (Whewell, 2019; Mourad, 2019; Segal, 2019). The COVID-19 pandemic demonstrated the dependence of agri-food supply chains on migrant labour (Schmidhuber et al., 2020; Clapp and Moseley, 2020), but it also crystallised how racialised structures exacerbate the vulnerability of migrant agricultural workers in the midst of a global health crisis, and thus the disposability of migrant labour in both transnational (Creţan and Light, 2020) and domestic circular labour migration (Jesline et al., 2021). While there are research on the promises of alternative food markets on promoting decent work (Florean et al., 2024) or the collective action of the farmworkers for labour justice utilising diverse political strategies (Mamonova, 2016; Kavak and Eren Benlisoy, 2025), workers in agri-food value chains are constrained by economic and political pressures.

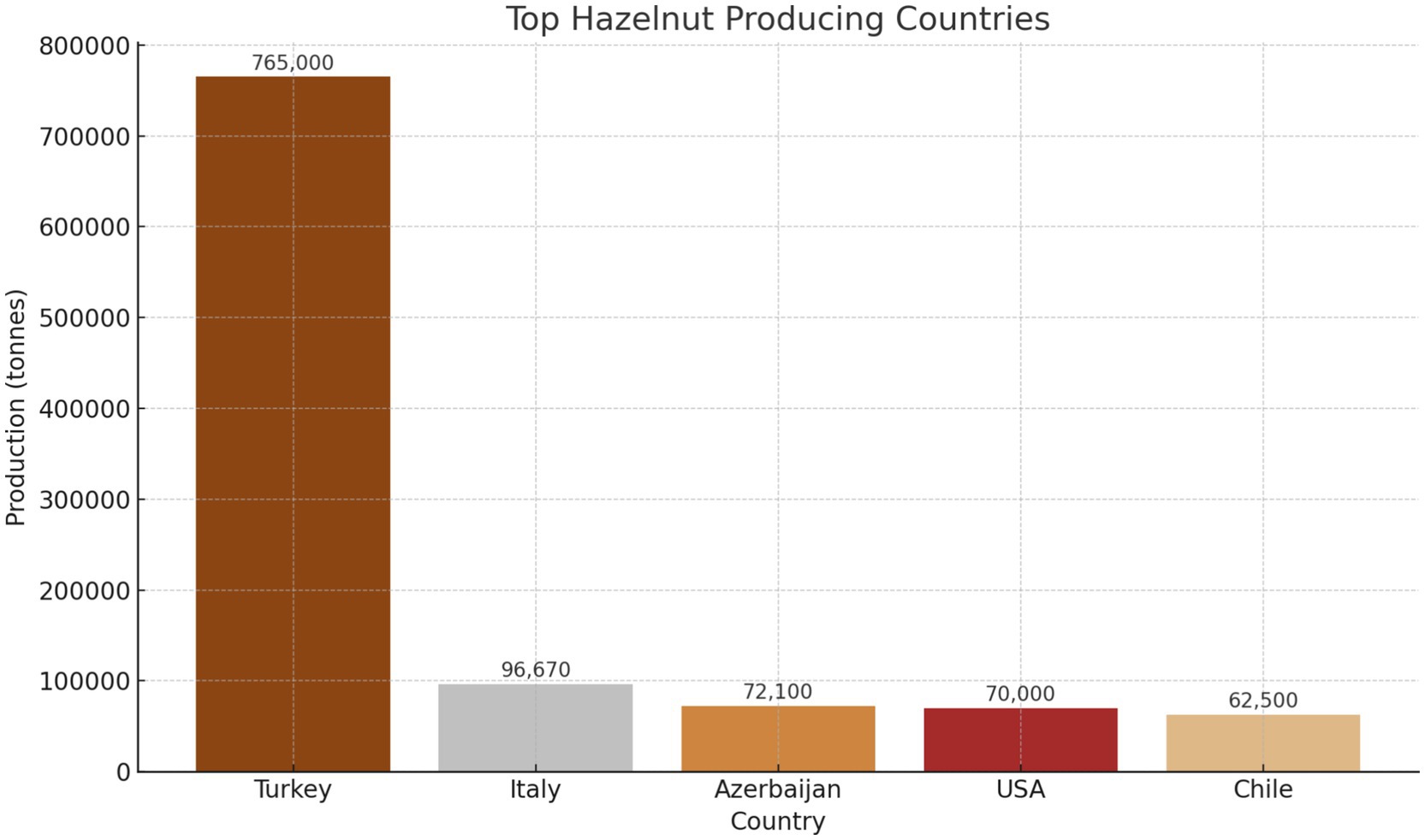

Empirically, this article focuses on the private-led labour governance in Turkey’s hazelnut market, a critical by overlooked part of the chocolate value chain. Turkey is the largest hazelnut producer on the global scale which produces up to 78 per cent of the global supply (Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations, 2022). Hazelnuts are harvested by migrant farmworkers, who are impoverished and marginalised Kurds and Arabs of the country, as well as Syrian refugees. Looking at the hazelnut market allows us to observe the effects of private-led labour governance at the corporate power and nation-state nexus in a crystalized fashion.

Labour governance is an emerging topic in agricultural work and value chains that needs more attention from the academic community (Malanski et al., 2021). The effectiveness of private governance in improving the livelihoods of producers and farm workers is still an open question in the literature (Oya et al., 2018), to which this article contributes. It asks:

How do national policies and state power affect the configuration of power along the value chain through an actor-based analysis? How do these interact with the existing vulnerabilities of migrant workers, and what are the implications for private labour governance more generally?

The literature focuses either on macro-structures or micro-practices, alongside the specificities of individual private governance systems and their implementation (Graz et al., 2020). Moreover, we also see the dominance of firm-centred analyses (Alford and Phillips, 2018). The reports vary considerably, as the studies that collect them approach the problem from different angles, but largely through socio-economic variables such as worker satisfaction, crop prices and an increase in wages, among others (Amengual et al., 2020; Anner, 2020; Barrientos and Smith, 2007; Brown and Getz, 2008; Carswell and de Neve, 2013; LeBaron, 2020). Wages do not appear to benefit from the presence of private regulation, and there is no evidence that total household income improves with certification (Cramer et al., 2014; Oya et al., 2018). There are gender-based constraints to achieving labour justice (Murphy et al., 2020) in gendered value chains Barrientos et al. (2019) and multiple dependencies exemplified by the role of labour contractors (Kavak and Eren Benlisoy, 2025). Ultimately, multiple factors shape the effectiveness of governance schemes, most of which are context-dependent (Oya et al., 2018) and socially embedded (Krauss and Barrientos, 2021). Racialisation is a topic that has been examined in the context of transnational migrant labour (Raeymaekers, 2024), but to a lesser extent in relation to private labour governance and the elaboration of domestic ethnicity.

This article contributes to the literature in two specific ways: First, it takes a holistic approach to the upstream value chain to examine different forms of power along the value chain, including the role of the state in the market and in law enforcement capacity. Secondly, it shows the interplay between constructed market volatility and ethnic tensions between workers and farmers in a Global South context where seasonal migrant workers are also citizens. It thus links the literature on private governance to the racialisation of agricultural labour addressing the discrimination and marginalisation beyond the transnational migration.

Focusing on the politics of governance Graz (2022), invites the concept of grounding with the objective of fostering communication between disciplinary divides and open a way to a ‘more holistic, embodied, and contextualised conceptual innovation’ (Graz, 2022, p. 8). Grounding entails evaluating transnational private governance as localised implementation of the standards, and practices of political contestation (Graz, 2022, p. 3). In a related fashion, scholars of political economy call for analysing the role of the state and public institutions in private governance, thus a political economy of governance (Mayer et al., 2017). Due to these advancements, scholars of the field turned their attention to interactions of private governance with the political economic structure of the country contexts, especially with a focus on emerging economies (Sun, 2022; Zajak, 2017) and authoritarian domestic politics (Bartley, 2018).

Building on these advancements, this article argues for the need to analyse politics beyond the translation and effectiveness of standards and transnational governance on the ground, but in interaction with forms of power, politics and inequalities on the ground. This involves disentangling the multiple forms of power among a variety of actors in the value chain. It employs a critical political economy approach to bridge global value chain analysis (GVC) and private labour governance to simultaneously explore relations between value chain actors and the power exercised by the state. This strain of literature, pioneered by Mayer et al. (2017), calls for moving beyond a firm-centric approach in GVCs and exploring the role played by the states and transnational private governance.

Instead of only focusing on a particular standard setting, programme implementation or the effectiveness of any voluntary governance scheme, the article analyses simultaneous affects by multiple private governance schemes that have different demands and dependencies. The results identify volatile pricing mechanism, cost of compliance and increasing ethnic tension as key areas leading to contention due to power asymmetries. The following sections explain these areas after an introduction of private labour governance and migrant labour in hazelnut production.

1.1 Materials and methods

This articles is a part of a larger research project on the hazelnut market, labour conditions and climate change. Empirically, it is based on field data collected by the author in both the Northwest and Southeast of Turkey through semi-structured, face-to-face, individual in-depth interviews (8) and focus group discussions (7) with a total of 45 migrant workers during hazelnut harvest. Data also included interviews 20 farmers and 20 local merchants on the market conditions, challenges related to the production and labour processes. The interviews, which lasted around 1 h, took place in hazelnut orchards, worker accommodations/camps, and village coffeehouses during the harvest between 2017 and 2023.

Additionally, 5 focus groups interviews with 15 workers were conducted in the workers’ hometowns, where they felt more secure and were more vocal about their experiences in the hazelnut region. Workers were inclined to self-sensor and move around the questions in the hazelnut region due to the feelings of insecurity and fear of getting a reaction from the farmers, or to larger degree, from labour supervisors. Thus, interviews with hazelnut workers in their hometown in the Southeastern Turkey helped to increase the validity of the research.

Verbal consent was acquired before the interviews and interviews are conducted in a culturally appropriate and politically sensitive manner. Respondents were selected using a combination of random and snowball sampling techniques. The livelihoods, socio-economic conditions and land tenure patterns of hazelnut farmers in the region are similar. The working conditions of migrant workers are also comparable, as industry-wide practices affect all migrant workers, thereby increasing the representativeness of the study.

Workers were asked to provide information about their experiences on hazelnut farms, including details of working conditions, accommodation, transport, working hours, payments, wages, overtime, underage employment and discrimination practices. Farmers were asked about commodity market conditions, certification programmes, audits, production and compliance costs, hazelnut prices, distribution channels, incentives and premiums for compliance, and the role of the state in setting prices, subsidies and support payments. Farmers were also asked about recruitment practices, their responsibilities towards and daily interactions with farm workers.

Data was analysed through descriptive and thematic coding of interviews to identify labour, working and living conditions for workers, market conditions and due diligence requirements for farmers, and vulnerabilities and interactions between different actors in the value chain, which are detailed in the findings and discussion sections. While the qualitative methodology was useful in identifying key trends and their causes, it was also challenging to collect data in the context of prevailing political and economic dependencies. A more embedded ethnographic approach may be useful to identify micro and fine-grained impacts in daily life.

2 Neo-liberalisation in a ‘nutshell’: the hazelnut market today

First step of the research is to identify the structure of the hazelnut market and map the value chain, including the farmers and workers. There are approximately 440,000 registered hazelnut producers in Turkey (ZMO, 2018). Hazelnut producers are predominantly smallholders (Gürel et al., 2019). Producer cooperatives were the driving force behind state-regulated agricultural policy, which led to the spread of market-oriented smallholder production (Kavak, 2012; İslamoğlu, 2017; Gürel et al., 2019). Hazelnut producers were organised under the Union of Hazelnut Sales Cooperatives (Fiskobirlik) and the market was regulated by the state, despite the neoliberalisation agenda initiated in the 1980s. In 2000, with the Agricultural Reform Implementation Project (ARIP) initiated by the World Bank in Turkey, the hazelnut market entered a liberalisation process that led to a complete restructuring of the market (Aydın, 2010; Keyder and Yenal, 2011).

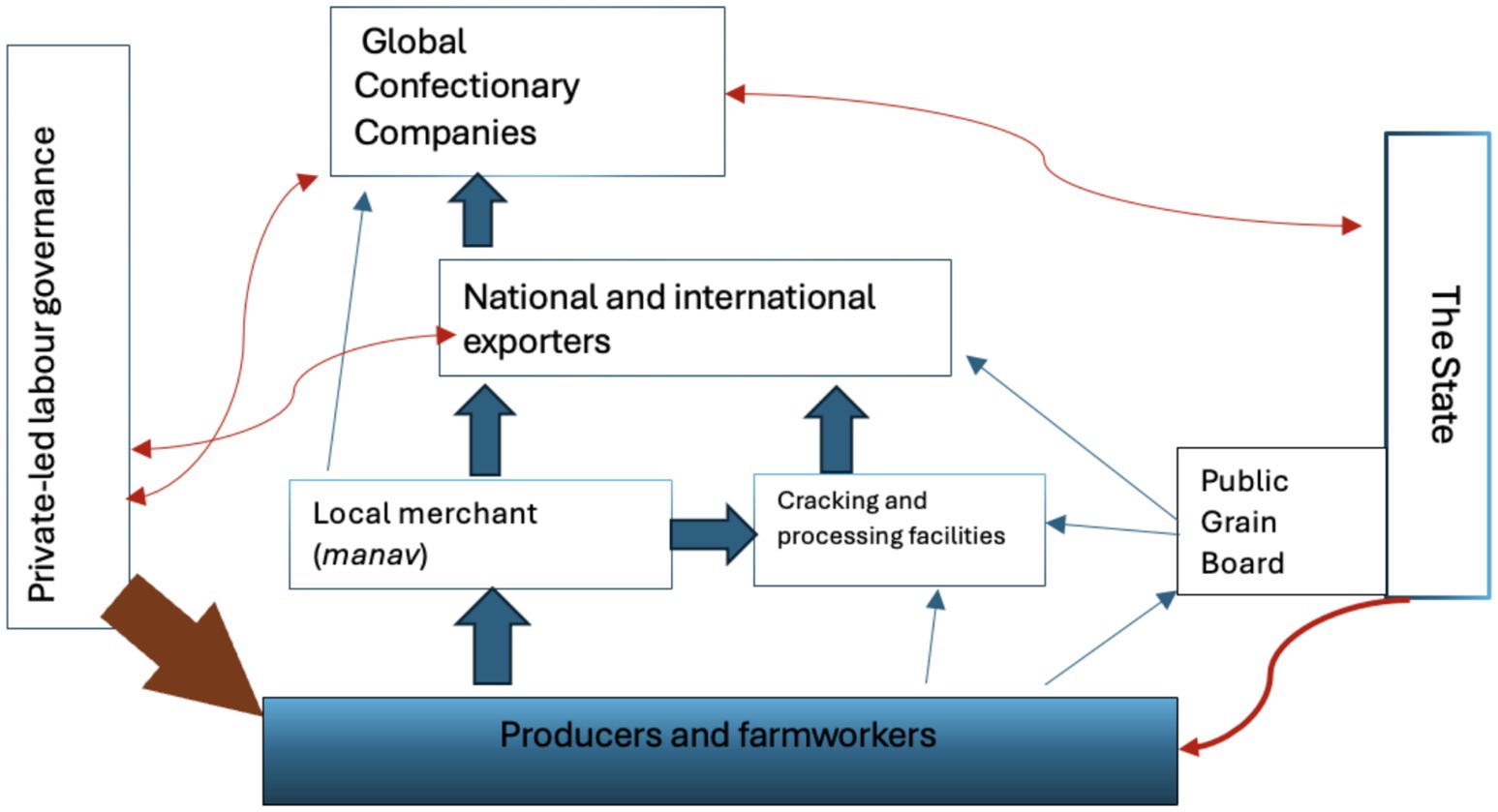

The research showed that there are numerous actors at the local level influencing the market and social justice dynamics at the state level, while the global market is dominated by a handful of companies and a handful of global exporters. The relationships between actors in the domestic market and between exporters and global buyers reveal a complex set of dynamics. These two sets of actors are not necessarily interlinked. The complexity of the market structure leads to constructed uncertainties, price volatility, political involvement and alternative governance mechanisms, such as the private-led social equity schemes that are the focus of this article. Before going into detail, I will briefly introduce the market process and its actors (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Top five hazelnut producing countries and their production volume. Source: Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (2022).

2.1 Market actors, value chain and labour governance

It is important to note that there is no contract farming in Turkish hazelnut market, and that is defining feature of the market relations that will be explained in the following sections. Contract farming is defined as “A binding arrangement between a firm (contractor) and an individual producer (contractee) in the form of a ‘forward agreement’ with well-defined obligations and remuneration for tasks done, often with specifications on product properties such as volume, quality, and timing of delivery” (Catelo and Costales, 2008). This implies that the producers do not know the buyer and price of the commodity when they will be selling their hazelnuts and implies that the market operates largely on the ‘invisible hand’ approach. Once the hazelnuts are collected and dried, they are sold to the local merchants at the prevailing commodity price of the day.

Local merchants, called ‘manav’ in Turkish, are the key actors and main point of contact for farmers in the market. Manavs directly purchase hazelnuts from the farmers during or after the harvest. Depending on their size, they either sell them either to larger merchants or to the major hazelnut exporters (which are direct suppliers of the global companies). Farmers can choose which manav to sell their crop to, but my observations suggest that villages are shared between manavs operating in the respective regions. These manavs are locals, either from the village or the town, and they have informal, day-to-day contact with the producers. They may provide loans or advances or store the hazelnuts in their facilities for the farmers. They are the key players who link the farmers to the exporters. Agronomists from exporter companies and local chambers of agriculture regularly visit them to monitor crop quality and provide information on how to improve crop quality (Figure 2).

Figure 2. Hazelnut value chain. Blue arrows: Commodity flow through trade. Red arrows: Due diligence and policy interventions.

Mergers and acquisitions have led to increasing market concentration in the value chain. Compared to the 1990s, there are fewer exporters in the Turkish market, supplying a handful of MNCs, of which Ferrero Rocher is the largest player, along with Mondelez International, Nestlé SA, Mars and Lindt. Two major events mark this concentration: the merger of Olam International, a major global agribusiness supplier, and Progıda, a local exporter, in 2011, and Ferrero’s acquisition of Oltan Gıda, the largest hazelnut exporter, in 2014.

As the relationship between capital investors and consumers with sustainability demands strengthened, third party due diligence organisations and their external funders became involved in the hazelnut market. UTZ Certified (now Rainforest Alliance), Good Agricultural Practices (GAP) and The Fair Labour Association are among the most active due diligence programmes for the hazelnut industry in social sustainability. These corporate social compliance and sustainability programmes often involve one or more local civil society organisations, UN agencies such as the ILO and UNICEF, and foreign donors such as retailers or government agencies such as the US Department of Labour and the US Department of Agriculture. Farmers become party in the labour governance programmes and they are directly responsible for the labour compliance without formal commitment neither to the programme or nor to the company, due to non-existence of contract farming. Global confectionery companies are the ones who decide which programmes to be implemented and how they are implemented. The exporters are required to implement those programmes and supply the companies with the certified or responsibly produced hazelnuts. The strategy of the exporters is to choose a geographical location suitable and easy to implement the programme where they have connections, mostly through local merchants called manav to ensure the geographical traceability of the product. That is to say, the farmers of a particular geographical location do business with the manavs in close vicinity to them. These manavs then sell the crop to the exporters who are operative within that vicinity. The villages are shared by the manavs and exporters. Exporter companies select villages where they will implement the responsible production programmes based on their personal and business connections with the manavs and the village governors. These personal relations allow exporters to implement due-diligence programmes, deliver trainings to farmers, get their summer schools running, and get approval from the producers for the third-party auditors. Hence, the involvement of the farmer in the company due-diligence programme is determined by local trade, personal and sometimes political relations.

Finally, and undoubtedly, the Turkish state also plays a key role in the sector, regulating cultivation, providing credit and acreage support, and implementing programmes to improve the conditions of pickers. In some years, the state also buys hazelnuts through the Turkish Grain Board (Toprak Mahsulleri Ofisi, TMO) to stabilise prices, usually in response to political demands or as a populist tool. However, support purchases are not institutionalised. The state decides to intervene sporadically, which adds another factor of uncertainty to market relations. Besides the involvement in pricing and procurement, the corporate sustainability agenda of the confectionary companies is also upheld at the state level through multilateral projects and lobbying. Since the early 2010s, the Turkish state has been a party to several public-private partnership projects with the ILO, UNICEF, the Association of Chocolate, Biscuits and Confectionery (CAOBISCO), the United States Departments of Agriculture and Labour, and global companies and exporters. Turkey and the European Union (EU) has been running a project titled ‘Elimination of Child Labour in Seasonal Agriculture’ since 2020 which is funded by the EU. Hazelnuts are among the target crops of the project.

There are therefore several powerful actors in the market, competing and cooperating at different levels. Private labour governance is one such area with a focus on child labour in seasonal migrant farmwork. Being a widespread problem in agriculture, child labour has a multitude of causes, effects and implications that extend beyond the scope of this article. However, it is crucial to highlight how child labour in agriculture has become a pivotal concern within the realm of private governance and international funding of multi-stakeholder initiatives, including public institutions. Primarily, child labour, and consequently labour governance, serves as the driving force and focal point within private governance systems, multi-stakeholder projects and international funding, which will be elaborated upon in the subsequent section.

2.2 Child labour and private labour governance agenda

Being a widespread problem in agriculture, child labour has a multitude of causes, effects and implications that extend beyond the scope of this article. However, it is crucial to highlight how child labour in agriculture has become a pivotal concern within the realm of private governance and international funding of multi-stakeholder initiatives, including public institutions. Primarily, child labour, and consequently labour governance, serves as the driving force and focal point within private governance systems, multi-stakeholder projects and international funding, which will be elaborated upon in the subsequent section.

Turkey joined the International Programme on the Elimination of Child Labour (IPEC) in 1992 and ratified the ILO Convention on the Worst Forms of Child Labour (No. 182) in 2001. Seasonal agricultural work is classified among the worst forms of child labour in Turkey’s policy agenda, prompting interventions by the government, the ILO, NGOs, and companies. According to the convention, the minimum employment age for seasonal agricultural work in sectors defined as worst forms of child labour is 18 years, making it illegal to employ younger children.

However, Turkey’s labour code does not apply to enterprises with fewer than 50 workers. Hazelnut orchards, typically small-or medium-sized businesses, informally employ 10–20 workers for a few weeks during the harvest season.

Multi-stakeholder child labour prevention programmes gained momentum in the early 2010s, coinciding with market concentration in the hazelnut industry [MLSS (Ministry of Labor and Social Security), 2010]. The primary program, run by the ILO and the Ministry of Labour and Social Security, began implementation at hazelnut farms in 2013. This public-private partnership is funded by CAOBISCO (Chocolate, Biscuits and Confectionery of Europe), an industry association representing major global confectionery companies.

Companies involved in hazelnut exports often purchase directly from farms, using intermediaries like local merchants. This direct involvement in sourcing makes them responsible for executing corporate social sustainability initiatives. In response to global demand, most exporters join certification programmes. Their ability to maintain and expand their exporting influence depends on effectively implementing on-ground corporate social sustainability projects and delivering ethically sourced hazelnuts at specified prices and timelines. Exporters proficient in cost-effective sustainability project implementation gain prominence in the local market, contributing to market concentration and creating instability for farmers.

Decent work programmes work with different codes of conduct, the content of these codes is similar. And in the case of Turkey, the content focuses mainly on decent work standards, which consist of a set of indicators and benchmarks relating to employment conditions, working hours, health and safety, discrimination, harassment and abuse, child labour and forced labour.

All programmes conduct farm-level audits during the harvest season. Farmers working in the areas where the company’s programmes are implemented will typically undergo a Good Agricultural Practices (GAP) and UTZ-Rainforest Alliance audit, as well as an audit for the company’s own CSR programme. These may be accompanied by a Fair Labour audit conducted by independent auditors. UTZ and GAP audits lead to certification, company audits are usually confidential, and Fair Labour audits are published on the organisation’s website for transparency.

Different schemes opt for different strategies of due diligence but there are three very common interventions; trainings and awareness raising, farm level interventions and implementation projects targeting children such as summer schools close to orchards. Training of farmers in good agricultural practices and corporate social sustainability is a very common component of social sustainability programmes. These also include training of workers, labour contractors, company staff and local authorities. Direct intervention activities at the farms by company representatives or their partnering NGOs, certification programmes, or third-party monitors is another component to achieve social sustainability. These include trainings, monitoring visits (both internal and third-party), and child removal, if one is found working. Farmers rarely have a say in these visits and monitoring; they are expected to welcome the company staff, NGOs, and the independent auditors. Thirdly, companies partner with international and non-governmental organisations to provide psychosocial and educational support to children. These include summer schools, mobile education units to reach children who work in remote farms.

Scrutinising hazelnut geographies allows one to observe the complex effects of private governance at multiple levels of dependencies, not only economically but also politically and culturally. One reason for this is, hazelnut is harvested by seasonal migrant workers from Turkey’s Kurdistan, who have become an essential workforce during transformation of Turkey’s agriculture (Kavak, 2016). They are composed of Kurdish and Arabic minorities of the country and refugees from Syria. The work is casual and informal, often done by children and women. Seasonal migrant workers have become the centre of transnational private governance in Turkey since the 2010s and new market-compatible social welfare standards of the ruling Justice and Development Party (AKP) period. Hence, focusing on migrant farm workers means focusing on the understudied role of state and politics in interaction with corporate agenda and sustainability programmes. Moreover, hazelnut is a market where one can observe heated contention among the market actors (i.e., exporters, vested political interest of the government and politicians, both from the perspective of electoral politics and cronyism, the flourishing national capital, cooperatives, farmers and public institutions).

Multiple research studies indicate that the primary workforce driving Turkish agriculture consists of seasonal migrant labourers, with over 1 million individuals estimated to be involved in farm-related activities (Kavak, 2016; Dedeoğlu, 2022). Furthermore, approximately 31 percent of child labourers in Turkey are employed within the agricultural sector (International Labour Organization, 2021). However, due to the predominantly informal nature of this sector, acquiring accurate and reliable data poses a challenge. According to data released by the Turkish Statistical Institute, there are around 1 million seasonal migrant labourers in Turkey, along with 220,000 children engaged in agricultural work (Turkstat, 2019). These labourers represent the most vulnerable and impoverished segment of the population, frequently subjected to violations of their human rights. A substantial majority of these seasonal migrant workers, over 90 %, originate from the southeastern region bordering Syria (Kavak, 2016). Previous investigations have demonstrated that 60 % of these workers’ household incomes fall below the national poverty line. Moreover, almost half (49 percent) of those actively employed in the fields from these households are under the age of 18 (Semerci, 2014); this figure is slightly lower for hazelnut production at 42 percent (Fair Labor Association, 2017).

3 Findings

Hazelnut pickers, including children, spend about 11 h a day on the farms, with 1.5 h of rest and lunch time. After returning to their temporary accommodation in the evening, they undertake a range of domestic tasks, including fetching water, cooking meals, washing dishes and doing laundry. While the hazelnut harvest typically takes place during the summer holidays, some families engage in seasonal migration, moving from farm to farm and crop to crop for periods of up to 9 months, if not the entire year. This prevents children from attending school regularly. It is not uncommon for children to start working in the fields at the age of 11 or 12. However, there have been cases where children as young as seven have been involved in such activities. Whether or not they are directly involved in agricultural work, these children are significantly affected by seasonal migration.

Workers focused on issues of working hours, accommodation and age verification as they often stay in unhygienic tent camps or makeshift structures and in overcrowded rooms. In these places, there is often no access to hot water and sometimes no access to clean drinking water. Workers have reported that it is very difficult to even take a shower after a long day’s work on the farm. These areas rarely have refrigeration, which means that dairy and meat products cannot be kept fresh, depriving children of the opportunity to consume nutritious meals.

With child labour at the forefront of private labour management, workers have become very aware of this, but unfortunately not always to keep children off the farms. Instead, they either try to hide the real age of those under 16 (the minimum age for legal employment) or keep the children off the farms during audits. This shows that policies to prevent child labour require more structural interventions to alleviate poverty.

Nevertheless, workers are generally appreciative of decent work interventions by companies and civil society when such a programme is in their immediate vicinity. This is another challenge as the area is vast and hilly and farms are usually far from village centres.

Smallholders are the primary employers of farmworkers. They hire farmworkers during the harvest, depending on the size of their land and crop maturation periods. Harvest usually takes place in August or early September. It is common practice for producers to share workers throughout the harvest since farms are small, the harvest is done in rounds, and each round takes couple of days. Workers either proceed to another plot by the same producer or farms of other producers, usually the relatives.

Farmers hire migrant workers for short periods and pay them the local daily wage. In hazelnuts, a local commission made up of executive and agricultural bodies declares a daily wage and maximum daily working hours for farm workers each year before the harvest. Farmers abide by the terms of the declaration but usually do not check the age of the workers. That is because employment is arranged by labour contractors, who put workers together and assign them to farms. The payment of the workers is also arranged by the labour contractors, who take 10% of the workers’ earnings as a service fee. The labour contractors are critical figures in the value chain as they have control beyond the farms, extending to other geographical areas where migrant workers work, as well as ensuring discipline and a control mechanism.

Farmers largely focused on the difficulties of growing hazelnuts and the volatility of the market. They complained almost exclusively about rising production costs (fertilisers, pesticides, fuel and labour costs), the lack of support from the government and the fact that the income from hazelnuts barely covered their costs. Dependence on hired labour was one of the concerns raised during the interviews, and was linked to rural depopulation in the hazelnut region. While they are appreciative of the activities by the companies and civil society, they largely stressed the pricing ambiguity as the main problem. Worker and farmer interviews analysed together, I have identified three major problems, that emerged as contentious at the intersection of market, politics and governance. These are (1) commodity price volatility, (2) cost of complience and (3) increasing contention towards farmworkers.

4 Discussion: power and politics in at the nexus of hazelnut value chain and private-led governance

Bartley (2018) reminds us that ‘10,000 feet up you can only see blurred structures—that is, broad contours of rulemaking, legitimation and convergence’ (p. 4). The analysis of the programmes cannot be done from 10,000 feet, looking only at norms, rights and implementation, nor do they operate in a vacuum between corporations, smallholders and farm workers. On the contrary, transnational private governance initiatives are part of larger constellations of complex relationships with significant involvement of the state, the state and workers, the state and farmers, farmers and capital, the state and capital, and certainly farmers and workers. Understanding these constellations requires an understanding of how power is conferred, manifested and exercised in the value chain. This article identifies two areas of contention exacerbated by the implemented by the private labour governance programmes: the cost of compliance and the growing tension between the farmworkers and smallholders.

4.1 Commodity price volatility and farmer vulnerability

The price mechanism is a useful prism for the analysis of power relations. The hazelnut market is a ‘dealer market’ (Dodd, 2002; Tekin Bilbil, 2012), where the market is constituted by bilateral negotiations between one or more dealers at multiple times during the harvest season. There is no fixed price for spot sales during the purchase between farmers and local dealers, or between local dealers and exporters. The price of the hazelnut changes instantaneously during individual trade agreements. In addition, hazelnut prices vary from province to province and these prices appear on the stock exchanges of these provinces. Price volatility is particularly high during and immediately after the harvest season, when supplies are plentiful. Here’s how one farmer describes this volatility: “You agree a price with the manav on the phone. He gets his truck to load your crop and drives to you. By the time he gets to you, let us say in half an hour, the price has changed. You either lose or win.”

However, in direct contrast to the volatility felt by growers, global chocolate manufacturers know the price they will pay a season before the harvest season. At the global level, hazelnut is an over the counter (OTC) derivatives market with little or no regulatory framework that operates with forward agreements (Tekin Bilbil, 2012). Forward agreements between the global buyer and major exporters determine the commodity price in futures markets, opening the market to speculation by exporters and international brokers. Knowing the price they will receive from the global buyer; exporters manipulate the market either by manipulating supply and demand in the spot market or by creating a sense of uncertainty in the market through discursive speculation. The former involves stockpiling hazelnuts when the price is low and reselling them at lower prices on the domestic market when prices tend to rise. The latter can involve different strategies.

The state plays an important role in the construction of price uncertainty. One way of doing this is to manipulate yield expectations. The State Statistical Institute sometimes forecasts a high yield as early as May or June to lower farmers’ price expectations. A high yield means lower prices, and the total yield can only be accurately predicted towards the end of July. This price anticipation by the Statistical Institute (which is not an authorised institution) is instrumentalised as a discursive strategy to manage farmers’ expectations.

Another such intervention that underpins the ambiguity can be observed in the market intervention of the Turkish Grain Board (TMO). The TMO has been authorised to intervene in the market to regulate prices through support purchases, but this authority is not an independent institutional one. It can only be mobilised with a ministerial decree, which is valid for a certain period and for a certain tonnage defined in the decree. In 2017, the TMO purchased hazelnuts at a certain price (10.5 TRY) and up to a certain quantity (140 thousand tonnes). Again in 2018, President Erdoğan announced that TMO would purchase hazelnuts from producers up to 2000 tonnes at 14 TRY. But the news came in November, 3 months after the harvest, when smallholders were already selling their crop on the market. The decision is a political one, presented in the media as a gift from the benevolent state and President Erdoğan. This small example shows how the support policy has been instrumentalised as a political tool for the authoritarian populist government. Prices start to rise after November, after most vulnerable smallholders have already sold their crops, and at the end of the day only a handful of better-off farmers and exporters benefit from higher prices.

For example, during the fieldwork, the stock exchange did not open the market and declare any spot price until after the harvest in late August, while the general practice is to declare an anticipated price per kilo towards the end of June. Smallholders had to sell the crop soon after the harvest because they did not have adequate storage facilities. Not knowing the price during and after harvest leads most smallholders to sell the nuts at lower prices.

This is where politics and state power come into play. Lowering the price even a little means a good profit for the exporter because of the high volume of exports in the market, which is concentrated in the hands of few exporters. The state contributes to this process by deepening price uncertainty because of its vested interests and crony relations with the exporters in an increasingly authoritarian neoliberal Turkey (Borsuk et al., 2021; Tansel, 2018).

Private-led labour governance programmes are being implemented in this context of high price volatility in the oligopolistic global market structure, characterised by the large number of local exporters in Turkey supplying certified and conventional hazelnuts to very few transnational corporations in the global market. During the interviews, a representative from the sustainability department of a global confectionery company stated that their strategy is to increase competition among exporters in Turkey in corporate responsibility and sourcing responsibly produced hazelnuts, since the purchase price is determined by the market in initial transactions. This demand is driving exporters to join various certification and due diligence programmes in the villages, where they can exert more influence on farmers to join the programme. Private initiatives can therefore exert influence on exporters, smallholders and workers in areas beyond the price of the commodity. These areas include land use, biodiversity, pesticide and fertiliser management for the environmental dimension. For social sustainability, working and accommodation conditions, worker profiles, employment relationship, anti-discrimination policies, child and forced labour, hours of work come to the fore. The scope and content of the remediation and preventive measures become areas that warrant analysis of power beyond the pricing in the commodity markets. In fact, commodity pricing is detached from the private-led sustainability agenda for the smallholders and workers. Following sections delve deeper into farmers’ and workers’ experiences.

4.2 Cost of compliance: who bears the cost?

Effectiveness of the standards implemented by companies is periodically verified by third party auditors. To join the certification programme, companies must pay an annual membership fee. This fee is related to the cost of monitoring the programme, but also to the value that the labels add to product prices in the form of premiums (Guthman, 2009, p. 202). In Turkish case, exporter companies pay for these membership fees and the audit costs. They also run pilot programmes in selected villages with selected producers, and as well as hometowns of workers.

However, farmers are expected to implement responsible production criteria on their farms, including better payment of workers, regulated working hours and conditions, age verification at farm level, provision of protective equipment for workers, ensuring health and safety relations as well as proper and sanitary accommodation conditions. Although these are minimum standards for decent work that should be ensured by the state, public institutions and the capital, farmers are the primary responsible party in ensuring decent work standards by multiple programmes and companies. Nevertheless, compliance comes at a cost, farmers must bear these costs.

Increasing workers’ wages is a major concern for farmers, who are earning less and less due to the volatility of the financialised market. In the past, workers’ daily wages have been below the minimum wage, and to control this, local wage fixing commissions have been set up in hazelnut regions, partly due to pressure and lobbying from stakeholders. These commissions set the daily wage to be paid to workers before the harvest at an amount equal to the gross minimum wage divided by 30 (average length of a month) instead of legal 21 working days per month. Farmers are usually required to pay a double wage to supervisors and a daily wage to the cook for larger groups of workers. Although the daily wage appears to be the gross minimum wage, it does not consider the required weekly breaks and working hours. A worker works 9.5 to 10 h a day, excluding lunch and rest breaks, and usually 7 days a week, as they do not earn any money for the days they do not work. In addition, labour brokers deduct 10% from the workers’ earnings, bringing the earnings below the minimum wage and therefore not compliant for most growers who rely on hired labour for the harvest. Although on paper daily wages are calculated in accordance with labour laws, workers earn less than they should if they were formally employed. The total income of worker households is usually below the poverty line (Levent et al., 2018).

Since farmers pay more for the workers, they tend to make workers work more efficiently, quickly, and with fewer breaks. A worker stated: “Supervisors yell at us to pick the hazelnuts quickly, they do not allow us to chat with the fellow workers, nor to take a toilet break outside of breaks.” Workers are made to collect hazelnuts under the rain or in dangerous mountainous areas under the threat of losing their jobs and withholding of wages. Workers need to continue working even if they are injured. If they need to go to the hospital, they finish the work first in order not to lose their daily earning. Or, if they cannot work due to heavy rain, they must compensate for the time the next day by doing overtime.

Other cost items in compliance include providing workers with proper accommodation, safe transport to orchards, and providing them with personal protective gear. Exporter companies run pilot programmes in selected villages with a selected number of farmers to improve these areas, but ultimately, the responsibility belongs to the farmers. In a landmark study on procurement price, Levent et al. (2018) suggest that “low price of hazelnuts perpetuates low wages, long working hours and intense working conditions” (p. 31) in hazelnut production. It is repeatedly stated by farmers that it is very hard for them to continue production because of depreciating commodity prices and increased production costs. They get loans to continue production, hoping to sell the yield for a better price at the end of the production season. They also tend to minimise costs, including hiring migrant workers instead of better-paid local workers. How about the economic value created by responsibly produced and certified hazelnut, which is traded for higher prices?

Certification programmes in the global hazelnut market is expected to function as redistributive mechanism with an objective of revenue allocation along the supply chain and actors. The theory of change of the certification programmes is also based on the assumption that ethically produced crops yield more income for the farmers who will then be able to pay more for the workers, describing a win-win deal.

However, in Turkish case, monetary benefits for farmers are impeded by the structure of the commodity market, due to the lack of contract farming. This is a point that I heard multiple times from the company representatives and private-led social justice organisations: Since there is no contract, we cannot offer a set price for the crop, or a set a predefined premium. We can never be sure that a particular farmer is in our supply chain.

The premium is detached from the commodity during the purchase, due to the lack of contract farming and claims that farmers are selling their commodity in the free market at the momentary spot price of the stock exchange. A manav recounts: “The price is determined from above [the exporter]. The farmer earns proportionate to the amount paid to the manav from above.” Hence, spot pricing does not automatically entail a premium for the producer. A closer interrogation will make visible that the premium is not a given, but a possibility for the farmer, dependent on a combination of circumstances, and it is largely unknown to the atomized smallholder stripped of an agricultural cooperative or any form of collective body to negotiate commodity prices. Within the broader political economy of hazelnut farming, farmers do not have any bargaining power on the price announced in regional spot markets when they sell the crop to the local merchants, including the certified product.

How about the earnings of the farmworkers who are the main target of private social justice schemes? Worker’s daily wages has increased with the mobilisation of the state apparatus, multilateral/multistakeholder social sustainability projects and lobbying. Every year before the harvest, provincial commissions declare a minimum for daily wages, which usually corresponds to the gross minimum wage divided by 30 days. Farmers comply with this. This intervention increased nominal earnings for the hazelnut workers compared to other crops and reflected in the social compliance audit reports to verify ethical production. But this rise does not necessarily imply improved conditions for the workers, since parts of their earnings are cut by the labour intermediaries as their service fee, for transportation costs and any cost that may arise during their stay in the hazelnut region.

Farmer income does not increase through certification and production efficiency which is embedded in the structure of the commodity market at the state-level. On the contrary, it declines due to depreciating commodity prices and increasing production costs, including the cost of compliance. However, farmers have a responsibility to provide better conditions for workers in line with prevailing international industry standards. This contributes to the grievance of the farmers towards the state, policymakers and workers. A farmer asks: ‘You [state] announce the daily wage of the worker before the harvest. Then why do not you [state] announce the price of hazelnut at the same time? This leads me to my last argument, which is increasing tension and grievance towards the seasonal migrant workers.

4.3 Increasing contention towards farmworkers

Power and inequality in value chains also entail scrutiny on racial power asymmetries and economic inequalities at the state level and it is a political and academic imperative to analyse private social justice initiatives against the backdrop of decades of ethnic conflict and broader political culture in Turkey. Hazelnuts are grown in the northernmost regions of the country, where the Turkish nationalism and conservatism are stronger among the residents (Gürel et al., 2019) and harvested by the workers from the southeast Turkey who are either Kurds and Arabs or-to a lesser extend-refugees from Syria. An earlier worker profiling study showed that 83% of the workers in the eastern and 61% of the western parts of the hazelnut region stated that Kurdish is their mother tongue (Fair Labor Association, 2017). Karapınar (2005) shows that Southeast Anatolia is an example of extreme inequality that has been ascribed through state politics and he righteously states, “Economic factors, such as integration into domestic and international markets, have affected the region through the filter of this politically embedded inequality” (p. 166). Private social justice activities contribute to the exacerbation of ethnic tensions and grievances against seasonal migrant workers in hazelnut regions through the power dynamics of the market and, of course, the role of the state.

The Turkish state is involved in the hazelnut sustainability agenda through both its legislative and law enforcement capacities; first by authorising local public institutions to set worker’s daily wages and working hours of the workers; and second, by empowering law enforcement, often the gendarmerie, to control and monitor the flow of migrant workers to the hazelnut region. The latter is practiced through identity checks at the village level. Workers are required to give a copy of their national identity cards to the village governor, and to be sent to the gendarmerie within 24 h upon their arrival. This constitutes an intimidating practice, especially within the context of ethnic conflict and discrimination. I should note that all seasonal migrant workers involved in hazelnut production are in the spotlight, regardless of whether the villages are within the geographical scope of the company’s due diligence programme, as advocacy and lobbying take place at the state level.

Hazelnut villages are the places of encounter between farmers leaning towards Turkish nationalism and Kurdish farmworkers, under the gaze of the state and pressure of the market. There is an undeniable tension in the villages and some of the farms that is often felt in the form of discrimination. During interviews with workers, many mentioned that they cannot talk with the farmers or other villagers, and they cannot freely wander in the village and the children said that they cannot freely play in the playgrounds because villagers complain. They reported that security personnel of the state (especially gendarmerie) advise workers to stay in their houses or camp areas and not to be visible in the public to avoid tensions between the locals and migrant workers of different ethnic backgrounds. Workers do not have any bargaining power in terms of working conditions and the earnings. They need to work as many days as possible and earn as much as possible before returning their hometowns. One worker explains: “There is a lot of discrimination. Locals do not talk to us on the farm. When they finish their work, they immediately leave. It is the same everywhere, we cannot say we are Kurds.” Another says: “It is like the cattle market. He (the farmer) cherry picks the workers, then complains saying that you are not working properly. The next day, he will not pick you.”

This potential political tension that is often felt in the form of discrimination occasionally erupts into assaults on migrant workers. During interviews with workers, many mentioned that they cannot talk with the farmers or other villagers, and they cannot freely wander in the village safely. The security personnel of the state (especially gendarmerie) advise workers to stay in their houses or camp areas, so as not to be visible in public, especially in the town, to avoid tensions between the locals and migrant workers. During my field visit in the villages where the private governance projects are implemented, farmers kept telling me: “You always ask about the workers, everyone asks and wants to learn about the workers, no one wants to learn about our problems, it is all about the workers now.”

Workers stated that they do not want to raise their voices and oppose farmer’s and supervisor’s demands. The ethnic tension and distrust towards state institutions became visible when I inquired about the daily conflicts and rights violations workers face in the hazelnut villages. A worker said “What will happen if we raise our voice, only the gendarmerie will get involved and the situation will become worse.”

I noticed that in the villages where social sustainability programmes were being implemented, workers became more intimidated. They did not want to be interviewed or were closely watched by the villagers during the interviews. This is due to a series of audits that farmers go through every year. Monitoring fatigue leads to a perception that what workers say or do will work against farmers’ interests in the context of volatile market conditions and private-led social justice programmes that focus on farmer responsibility.

It is important to recognise the positive contributions. Summer schools run by NGOs can provide a safe space for young children to play and socialise with other children, rather than staying in the unsanitary conditions of the labour camps. The children I interviewed said they liked going to school. But this is not sustainable. When they reach working age, 12–13 years old, they end up in the orchard. Or if they switch from hazelnut to another crop—which is usually the case—they end up working in the field again. So the solution outside the market is far from sustainable. A 12-year-old child labourer said that social workers tried to prevent him from working by enrolling him in the summer school programme, which he could only attend for 1 day. The farmer then called him to the orchard and explained that he had calculated the total amount to be paid for a total number of workers, including the child. As a result, the family had to withdraw him from the summer and take him to the orchard. I have to work because everyone is working,” he said.

4.4 Interaction and implications

These three areas of contention exemplifies that the impacts of the private labour governance extends beyond the indicators of the individual labour governance programmes and context is crucial in identifying variation affects (Oya et al., 2018). While some workers reported satisfaction with the decent work programmes, or their income increased compared to other commodities-which are indicators for success for labour governance-, the smallholders are put into increased insecurity due rising costs of the compliance, absence of price-premium and constructed ambiguities in pricing.

Alongside growing evidence showing how voluntary standards primarily serve the interests of firms, these standards have also led to increased intervention for farmers by supplier firms, local merchants, civil society, and states, driven by heightened demands for audits, traceability, and best practices (Bartley, 2022; Power, 2019). More importantly, LeBaron (2020) identified hidden costs of supply chain solutions, that end up in unintended consequences (i.e., leading way to alternative extractive industries, reinforce unequal development models or legitimise corporations). Their research on the hidden costs of supply chains highlights the need not only to assess the effectiveness of voluntary standards but also to examine the broader power dynamics and concealed costs that extend beyond individual programmes’ specific objectives, key performance indicators, and audit results. This approach calls for attention to power and inequality dimensions, focusing on how power is structured, exerted, and experienced by diverse actors within global value chains, with a particular impact on farmers.

This is how the article connects to the emerging grounding perspective (Graz, 2022). It shows how implementation of the decent labour standards without taking the commodity market structure, possibility of price-premium and racial power asymmetries can end up leading to heightened forms of discrimination, marginalisation and political contestation. This is not independent from the state power, both in market and in disciplining diverse socio-economic groups.

Hence this article calls for a political economy approach in analysing the role of the state and public institutions in private governance, thus a political economy of governance (Mayer et al., 2017) combining the governance research with political economic structure of the country contexts, especially with a focus on emerging economies (Sun, 2022; Zajak, 2017) and authoritarian domestic politics (Bartley, 2018).

5 Conclusion

Transnational private regulation does not take place in a vacuum, free of existing power structures and asymmetries, nor is it only dominated by corporate power along the value chain. In the similar vein, it is not just a dance between the power of the firm along the supply chain and the power of state in controlling politics on the ground. Power is vested in complex constellations among value chain actors and in interaction with deeply embedded power asymmetries. It goes beyond firm’s value chain, interacts with the power and politics on the ground which can be observed in pricing, in politics and in daily relations between the target groups of the due-diligence programmes, migrant workers and smallholders.

Although it has received less attention than other agri-food value chains—such as cocoa, coffee, palm oil, cotton, etc.—the hazelnut value chain offers an analytically fruitful site for the analysis of power and politics in value chains, where the power exercised by private labour governance programmes is an integral part. As a major sector of the global chocolate market, most of the hazelnut production takes place in an increasingly authoritarian and conflict-ridden country, with an undeniable trend towards market concentration and the prevalence of smallholder production dependent on hired labour for harvesting, with farm workers belonging to ethnic minority and refugee groups.

A closer look at the value chain and the relationships between market actors is necessary to question the real impact of responsible business practices and the complex dynamics that contribute to the vulnerability of smallholders and farm workers. The results identify volatile pricing mechanism, cost of compliance and increasing ethnic tension as key areas leading to contention due to power asymmetries. In Turkey, certification does not allow farmers to increase their market power or their incomes. On the contrary, it contributes to the insecurity of producers, especially smallholders. Although companies appear to be primarily responsible for certification programmes, the costs of compliance are borne by the farmers, but the associated premium payments cannot be traced back to them. An average hazelnut farmer must undergo three or four audits during a harvest on the decent working practices they apply to their workers.

The state contributes to increased corporate profits by creating price uncertainties for smallholders. As the article shows, farmers’ incomes do not increase because of certification and production efficiency; on the contrary, they fall due to falling commodity prices and rising production costs. However, workers’ incomes have increased with the mobilisation of the state apparatus through lobbying and multilateral social sustainability projects in hazelnut. Legislation and law enforcement capacities are mobilised by capital.

The programmes are mainly implemented in the global South, where most of the world’s food is produced. Transnational private regulatory regimes are employed by global corporations, but procurement, supply, commodity pricing and market concentration take place with significant involvement of the state agency, which is heavily influenced by the prevailing power struggles in the country. The article argues that the prevalence of private-led decent work initiatives in the hazelnut market may end up exacerbating power asymmetries, both economic and political. It shows that private governance may end up contributing to smallholders’ insecurity and vulnerability and argues that both smallholders and farm workers experience increased pressure in the context of a volatile price mechanism and constructed insecurity. While it is difficult to anticipate these hidden costs, it argues that any effort to assess the effectiveness of private-led social justice schemes in food production must include a thorough analysis of country politics and the structure of the commodity market. Further research is needed to identify other possible negative impacts of labour governance due to the social embeddedness and context dependency of manifestations of power in value chains.

Data availability statement

The datasets presented in this article are not readily available because this article is based on qualitative interviews collected by the author. Requests to access the datasets should be directed to c2luZW0ua2F2YWtAbHVjc3VzLmx1LnNl.

Ethics statement

Ethical approval was not required for the studies involving humans because no personal and sensitive data are recorded and all the interviews were anonymized during the interviews. Acquiring written consent can backlash in countries like Turkey as people are sceptical towards the written material and signatures, therefore I acquired verbal consent. The studies were conducted in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. Written informed consent for participation was not required from the participants or the participants’ legal guardians/next of kin in accordance with the national legislation and institutional requirements because it is not required according to the prevailing ethics rules in Turkey, and also written consent can backlash and intimidate people because of the political sensitives in the country.

Author contributions

SK: Conceptualization, Formal analysis, Funding acquisition, Investigation, Methodology, Resources, Supervision, Visualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declare that financial support was received for the research and/or publication of this article. Part of the research in this article is supported by a project grant from Formas (Swedish Research Council for Sustainable Development) with grant ID 2021-00567.

Conflict of interest

The author declares that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The author declares that no Gen AI was used in the creation of this manuscript.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

Alford, M., and Phillips, N. (2018). The political economy of state governance in global production networks: change, crisis and contestation in the south African fruit sector. Rev. Int. Polit. Econ. 25, 98–121. doi: 10.1080/09692290.2017.1423367

Amengual, M., Distelhorst, G., and Tobin, D. (2020). Global purchasing as labor regulation: the missing middle. ILR Rev. 73, 817–840. doi: 10.1177/0019793919894240

Anner, M. (2020). Squeezing workers’ rights in global supply chains: purchasing practices in the Bangladesh garment export sector in comparative perspective. Rev. Int. Polit. Econ. 27, 320–347. doi: 10.1080/09692290.2019.1625426

Aydın, Z. (2010). Neo-Liberal transformation of Turkish agriculture. J. Agrar. Chang. 10, 149–187. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-0366.2009.00241.x

Barrientos, S., Bianchi, L., and Berman, C. (2019). Gender and governance of global value chains: promoting the rights of women workers. Int. Labour Rev. 158, 729–752. doi: 10.1111/ilr.12150

Barrientos, S., and Smith, S. (2007). Do Workers benefit from ethical trade? Assessing codes of labour practice in global production systems. Third World Q. 28, 713–729. doi: 10.1080/01436590701336580

Bartley, T. (2018). Transnational corporations and global governance. Annu. Rev. Sociol. 44, 145–165. doi: 10.1146/annurev-soc-060116-053540

Bartley, T. (2022). Power and the practice of transnational private regulation. New Political Econ., 27:188–202. doi: 10.1080/13563467.2021.1881471

Borsuk, İ., Dinç, P., Kavak, S., and Sayan, P. (2021). “Consolidating and contesting authoritarian neoliberalism in Turkey: towards a framework” in Authoritarian neoliberalism and resistance in Turkey: Construction, consolidation, and contestation. eds. I. Borsuk, P. Dinç, S. Kavak, and P. Sayan (Springer Singapore: Singapore), 11–59.

Brown, S., and Getz, C. (2008). Privatizing farm worker justice: regulating labor through voluntary certification and labeling. Geoforum 39, 1184–1196. doi: 10.1016/j.geoforum.2007.01.002

Carswell, G., and De Neve, G. (2013). Labouring for global markets: conceptualising labour Agency in Global Production Networks. Geoforum 44, 62–70. doi: 10.1016/j.geoforum.2012.06.008

Catelo, M. A. O., and Costales, A. C. (2008). Contract farming and other market institutions as mechanisms for integrating smallholder livestock producers in the growth and development of the livestock sector in developing countries. (FAO Working Paper). Rome, Italy: Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations.

Clapp, J., and Moseley, W. G. (2020). This food crisis is different: COVID-19 and the fragility of the neoliberal food security order. J. Peasant Stud. 47, 1393–1417. doi: 10.1080/03066150.2020.1823838

Corrado, A., de Castro, C., and Perrotta, D. (2017). “Cheap food, cheap labour, high profits: agriculture and mobility in the Mediterranean” in Migration and agriculture: Mobility and change in the Mediterranean area. eds. A. Corrado, C. Castro, and D. Perrotta (Abingdon: Routledge), 1–24.

Cramer, C., Johnston, D., Oya, C., and Sender, J. (2014). Fairtrade, employment and poverty reduction in Ethiopia and Uganda.

Creţan, R., and Light, D. (2020). COVID-19 in Romania: transnational labour, geopolitics, and the Roma ‘outsiders’. Eurasian Geogr. Econ. 61, 559–572. doi: 10.1080/15387216.2020.1780929

Dedeoğlu, S. (2022). Syrian Refugees and Agriculture in Turkey: Work, Precarity, Survival. London: I. B. Tauris.

Fair Labor Association . (2017). Demographic profiling of seasonal migrant workers in agriculture: Hazelnut harvesting in Turkey. Available online at: https://www.fairlabor.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/01/demographic_profiling_hazelnut_workers_in_turkey_september_2017.pdf (accessed September 14, 2023).

Florean, S., Crețan, R., and Doiciar, C. (2024). Beyond mass food production and consumption: the emergence of alternative food networks in Romania. Cogent Soc. Sci. 10:2437053. doi: 10.1080/23311886.2024.2437053

Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (2022). FAOSTAT: crops and livestock products – hazelnuts, in shell. Italy: FAO.

Graz, J. C. (2022). Grounding the politics of transnational private governance: introduction to the special section. New Political Econ., 27:177–187. doi: 10.1080/13563467.2021.1881472

Graz, J. C., Helmerich, N., and Prébandier, C. (2020). Hybrid production regimes and labor agency in transnational private governance. J. Bus. Ethics 162, 307–321. doi: 10.1007/s10551-019-04172-1

Gürel, B., Küçük, B., and Taş, S. (2019). The rural roots of the rise of the justice and development Party in Turkey. J. Peasant Stud. 46, 457–479. doi: 10.1080/03066150.2018.1552264

Guthman, J. (2009). “Unveiling the unveiling: commodity chains, commodity fetishism and the ‘value’ of voluntary, ethical food labels” in Frontiers of Commodity Chain Research (California: Stanford University Press), 190–206.

International Labour Organization (2021). Seasonal agricultural workers in the hazelnut supply chain in Turkey: hazelnut harvest and post-harvest process. Turkey: ILO Office.

İslamoğlu, H. (2017). “The politics of agricultural production in Turkey” in Neoliberal Turkey and its discontents: Economic policy and the environment under Erdogan. eds. F. Adaman, B. Akbulut, and M. Arsel, (London: I.B. Tauris). 75–102.

Jesline, J., Romate, J., Rajkumar, E., and George, A. J. (2021). The plight of migrants during COVID-19 and the impact of circular migration in India: a systematic review. Human. Soc. Sci. Commun. 8, 1–12. doi: 10.1057/s41599-021-00915-6

Karapınar, B. (2005). Land inequality in rural southeastern Turkey: rethinking agricultural development. New Perspect. Turk. 32, 165–197. doi: 10.1017/S0896634600004155

Kavak, S. (2012). Struggling for survival in the village: New rurality and patterns of rural restructuring in response to agricultural liberalization in Turkey : LAP Lambert Academic Publishing. Saarbrucken, Germany.

Kavak, S. (2016). Syrian refugees in seasonal agricultural work: a case of adverse incorporation in Turkey. New Perspect. Turk. 54, 33–53. doi: 10.1017/npt.2016.7

Kavak, S., and Eren Benlisoy, Z. C. (2025). Seasonal migrant farm workers at the nexus of production and social reproduction in contemporary Turkey. Agric. Hum. Values, 1–19. doi: 10.1007/s10460-025-10720-5

Keyder, Ç., and Yenal, Z. (2011). Agrarian change under globalization: markets and insecurity in Turkish agriculture. J. Agrar. Chang. 11, 60–86. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-0366.2010.00294.x

King, R., Lulle, A., and Melossi, E. (2021). New perspectives on the agriculture–migration nexus. J. Rural. Stud. 85, 52–58. doi: 10.1016/j.jrurstud.2021.05.004

Krauss, J. E., and Barrientos, S. (2021). Fairtrade and beyond: shifting dynamics in cocoa sustainability production networks. Geoforum 120, 186–197. doi: 10.1016/j.geoforum.2021.02.002

LeBaron, G. (2020). Combatting modern slavery: Why labour governance is failing and what we can do about it. Cambridge: Polity Press.

Levent, H., Yukseker, D., Sahin, O., Sert, D., and Erkose, Y. (2018). Hazelnut Barometer-Procurement Price Study : Fair Labour Association.

Malanski, P. D., Dedieu, B., and Schiavi, S. (2021). Mapping the research domains on work in agriculture. A bibliometric review from Scopus database. J. Rural. Stud. 81, 305–314. doi: 10.1016/j.jrurstud.2020.10.050

Mamonova, N. (2016). Naive monarchism and rural resistance in contemporary Russia. Rural. Sociol. 81, 316–342. doi: 10.1111/ruso.12097

Mayer, F. W., Phillips, N., and Posthuma, A. C. (2017). The political economy of governance in a ‘global value chain world’. New Political Econ. 22, 129–133. doi: 10.1080/13563467.2016.1273343

MLSS (Ministry of Labor and Social Security) , (2010). Mevsimlik Gezici Tarım İşçilerinin Çalışma ve Sosyal Hayatlarının İyileştirilmesi Stratejisi ve Eylem Planı planı (Başbakanlık Genelgesi No. 2010/6). Ankara: Çalışma ve Sosyal Güvenlik Bakanlığ.

Mourad, S. (2019). Nutella and Ferrero Rocher rocked by child labour claims. Available online at: https://www.dailymail.co.uk/news/article-7497763/Nutella-Ferrero-Rocher-rocked-child-labour-claims.html (accessed May 6, 2024).

Murphy, S., Arora, D., Kruijssen, F., McDougall, C., and Kantor, P. (2020). Gender-based market constraints to informal fish retailing: evidence from analysis of variance and linear regression. PLoS One 15:e0229286. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0229286

Oya, C., Schaefer, F., and Skalidou, D. (2018). The effectiveness of agricultural certification in developing countries: a systematic review. World Dev. 112, 282–312. doi: 10.1016/j.worlddev.2018.08.001

Power, M. (2019). “Infrastructures of traceability” in Thinking infrastructures (research in the sociology of organizations). ed. M. Kronenberger . (Bingley, UK: Emerald), 62:115–130.

Raeymaekers, T. (2024). The natural border: Bounding migrant farmwork in the black Mediterranean. Ithaca and London: Cornell University Press.

Schmidhuber, J., Pound, J., and Qiao, B. (2020). COVID-19: channels of transmission to food and agriculture (38 pp.; FAO Working Paper No. 20210277367). Rome, Italy: Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations. doi: 10.4060/ca8430en

Segal, D. (2019). Syrian Refugees Toil on Turkey’s Hazelnut Farms with Little to Show for It—The New York Times. Available online at: https://www.nytimes.com/2019/04/29/business/syrian-refugees-turkey-hazelnut-farms.html (accessed June 11, 2021).

Sun, Y. (2022). Certifying China: The rise and limits of transnational sustainability governance in emerging economies. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.Press.

Tansel, C. B. (2018). Authoritarian neoliberalism and democratic backsliding in Turkey: beyond the narratives of progress. South European Society Politics 23, 197–217. doi: 10.1080/13608746.2018.1479945

Tekin Bilbil, E. (2012). The politics of Uncertainity in a global market: The hazelnut exchange and its production [PhD]. Boğaziçi University.

Turkstat (2019). Çocuk İşgücü Anketi Sonuçları. Available online at: https://data.tuik.gov.tr/Bulten/Index?p=Child-Labour-Force-Survey-2019-33807 (accessed May 15, 2022).

United Nations . (n.d.). Goal 8: Promote sustained, inclusive and sustainable economic growth, full and productive employment and decent work for all. Available online at: https://sdgs.un.org/goals/goal8 (retrieved November 10, 2024).

Whewell, T. (2019). Is Nutella made with nuts picked by children? BBC News. Available online at: https://www.bbc.com/news/stories-49741675 (accessed April, 14 2021).

Zajak, S. (2017). Transnational activism, global labor governance, and China. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan.

ZMO . (2018). FINDIK RAPORU-2018. Available online at: https://zmo.org.tr/genel/bizden_detay.php?kod=30070&tipi=38&sube=0 (accessed June, 13 2021).

Keywords: grounding, decent work, transnational labour governance, certification, agriculture, farmworkers, ethnicity

Citation: Kavak S (2025) Transnational labour governance in hazelnut value chain: farmers and seasonal migrant workers at the nexus of market and politics in Turkey. Front. Sustain. Food Syst. 9:1530220. doi: 10.3389/fsufs.2025.1530220

Edited by:

Valentina Siracusa, University of Catania, ItalyReviewed by:

Remus Cretan, West University of Timișoara, RomaniaLinda Forst, University of Illinois Chicago, United States

Copyright © 2025 Kavak. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Sinem Kavak, c2luZW0ua2F2YWtAbHVjc3VzLmx1LnNl

Sinem Kavak

Sinem Kavak