- 1Institute of Agricultural Economics and Development, Chinese Academy of Agricultural Sciences, Beijing, China

- 2School of Public Administration, Zhongnan University of Economics and Law, Wuhan, China

Counties are key regions for grain production in China, and it is essential to incentivize county governments to focus on grain production to ensure national food security. This study uses county-level data from 2000 to 2021 to assess the impact of the reward policy for major grain-producing counties (RPMGC) on county governments' incentives to support grain production (CGISGP), employing a difference-in-differences approach. The results show that: (1) The implementation of RPMGC significantly increased CGISGP, and this result remains robust under parallel trend, placebo, and other robustness tests; (2) Further analysis reveals that the effect appeared in the first year after the policy's implementation and gradually diminished by the fifth year. The policy's impact is not sustained in the long term; (3) The effect was more pronounced in counties with high bonus distribution coefficients, large primary sectors, and significant financial pressure. It is necessary to promptly adjust and improve the RPMGC, accelerate horizontal grain interest compensation mechanisms, and enhance the endogenous motivation of grain-producing counties.

1 Introduction

Since the founding of the People's Republic of China, the country has developed a unique food security path through long-term practice and exploration, establishing a governance system in which the central government plays a leading role and local governments are the primary implementers. County-level governments, as grassroots administrative units, bear the critical responsibility of developing local grain production and ensuring national food security, thus occupying a pivotal role in the overall food security governance system. Particularly, major grain-producing counties, which account for nearly three-fourths of national grain production, are essential to ensuring national food security. Effectively stimulating the incentives of county governments for food security and ensuring that they fulfill their responsibilities is a major strategic necessity for the continued enhancement of food security capacity and the modernization of the country's food security governance.

The governance model with Chinese characteristics, defined by political centralization and fiscal decentralization following the tax-sharing reform, has led to local governments facing pressures due to the mismatch between administrative and financial powers, as well as a sharp decrease in disposable financial resources (Li and Du, 2021). Under the “GDP supremacy” concept, local governments prioritize investing their limited financial resources in productive construction projects that generate high tax revenues and returns, which are characterized by short cycles and quick results (Li and Li, 2024), while naturally neglecting food projects, which are marked by long cycles, high risks, and low returns. The complete abolition of the agricultural tax may have exacerbated the imbalance between local fiscal revenues and expenditures, as well as the reduction in fiscal expenditures allocated to agricultural production (Tai, 2014; Jiang et al., 2022). On the other hand, national food security is of strategic importance to social, economic, and political stability. The central government has consistently emphasized the importance of safeguarding food security and has allocated food security responsibilities across all levels of government. In addition, the central government has allocated responsibilities based on regional resource endowments, with major grain-producing areas and large grain-producing counties shouldering a larger share of the responsibility for food security. These regions have also sacrificed greater development opportunities and benefits due to the externalities and opportunity costs associated with grain production, trapping them in a development dilemma characterized by a severe disconnect between the responsibilities they bear and the economic returns they receive (Gong, 2015; Wang et al., 2024). Over time, the accumulation of imbalances and conflicts of interest between the central and local governments, as well as between regions, has significantly undermined the motivation of local governments to manage grain production and the incentives for farmers to grow grain. Coordinating the responsibilities and interests of all levels of government and regions in food security through effective mechanisms, as well as stimulating the endogenous motivation of local governments to ensure food security, is essential to enhancing food security governance.

Transfer payments, as a key tool for coordinating fiscal relations following the tax-sharing reform, significantly impact local governments' fiscal expenditure decisions and attention allocation. As a result, they have increasingly become an essential means for the central government to guide and mobilize local governments in implementing centrally set targets. Several studies have demonstrated that transfer payments play a significant role in alleviating interregional financial imbalances and enhancing the provision of local public goods, which is essential for local government governance (Zhang and Wang, 2023; Chu and Fei, 2021). Striving for more transfer funds in negotiations with the central government is a rational choice for local governments (Xu and Hou, 2010), and in this process, the central government can also use transfer payments to motivate local governments to actively achieve preset policy objectives. A number of studies have recently examined whether transfer payments can incentivize local governments to focus on agriculture and grain production. On one hand, some studies argue that although the abolition of the agricultural tax eliminates local governments' fiscal revenue from grain production, they remain strongly incentivized to support agriculture, primarily due to the central government's lucrative transfer payments (Zeng, 2015); other studies have empirically shown that central government transfers can positively influence local governments' investment in agriculture (Zhao and Li, 2016) and that transfer payments significantly promote agricultural output (Zhu et al., 2024; Li et al., 2025). On the other hand, some studies suggest that, because general transfer funds are unrestricted, their effect on local governments' agricultural expenditures is minimal (Yang, 2016); transfer payments have not been able to counteract the decline in local governments' net fiscal revenues caused by the abolition of the agricultural tax, and the practice of raising fiscal revenues through land sales has led to a reduction in arable land (Zhang et al., 2021). This suggests that the impact of transfer payments on local governments' decisions to support agriculture is uncertain and requires in-depth analysis in the con-text of specific policy scenarios.

As mentioned earlier, major grain-producing counties have made significant sacrifices to ensure food security. Therefore, in order to compensate for the economic losses of these counties, China implemented the RPMGC in 2005. Essentially, this policy is a transfer payment measure by the central government to compensate for the interest losses of these counties, falling within the category of transfer payments. RPMGC aims to “alleviate the financial difficulties of major grain-producing counties, stimulate the incentives of local governments to support grain production, and safeguard national food security”. County-level data may be difficult to obtain, so currently only a small number of studies have evaluated the effects of the RPMGC. Regarding the relationship between the RPMGC and grain production, Wang et al. (2025), Zhao et al. (2024), and Zhao and Hou (2021) focused on the relationship between RPMGC and grain production, finding that the policy significantly promotes grain production in major grain-producing counties. Luo and Zhang (2024), after demonstrating the policy's effectiveness in promoting grain production, analyzed the program from a cost-benefit perspective and affirmed its economic benefits. Regarding the relationship between the RPMGC and farmers' income as well as economic development, Wu and Zhang (2023) investigated the impact of the policy on farmers' incomes and county-level economic development, finding that while the policy positively affected farmers' incomes, it did not contribute to economic development. Additionally, some studies have found that the policy pro-vides limited incentives for local governments, primarily due to the insufficient scale of the incentive funds, which fail to significantly enhance local financial resources (Zheng and Song, 2023). Furthermore, the growth rate of the incentive funds shows a clear downward trend, weakening the policy's compensatory effect (Gao and Wei, 2021). Additionally, several studies have suggested that the implementation of this policy may prompt county governments with grain production marginally below the incentive threshold to overreport their production to secure incentive funds (Zhang et al., 2020).

The above studies provide valuable insights for understanding the effects of the RPMGC, but there are still several limitations: First, existing research has not paid sufficient attention to RPMGC. Studies on grain interest compensation have primarily focused on the provincial level, specifically on the compensation between major grain-producing areas and major grain-consuming areas, with insufficient focus on the county level, especially on grain interest compensation in major grain-producing counties. Second, existing research on RPMGC has mainly concentrated on the policy's impact on grain production, farmers' income, and economic development, while overlooking its influence on county governments' behavior, particularly regarding its role in promoting CGISGP. In fact, the incentive funds, as general transfer payments, are primarily allocated through county finances and can be used across various areas, including grain production, social security, and public goods expenditures. Therefore, the impact of the policy on county government behavior is crucial to realizing the policy's ultimate effect. A closer examination of the policy text reveals that the incentive funds for large grain-producing counties serve as a supplement to the financial resources of county governments. These transfer funds are particularly attractive to county governments facing financial difficulties. Moreover, the impact of RPMGC on CGISGP is also closely linked to factors such as the level of the bonus distribution coefficients, the structure of industrial development, and the level of government financial resources. These issues require in-depth exploration, supported by empirical evidence.

In summary, this study analyzes the impact of the RPMGC on CGISGP and aims to con-tribute to the existing literature in the following ways: First, unlike previous studies, we focus primarily on the impact of RPMGC on CGISGP, thereby expanding the perspective on research related to RPMGC. Second, we analyze the behavioral differences and the formation process of county-level government support for grain production, explaining the underlying logic of how RPMGC influences CGISGP, and offering a new perspective and theoretical framework for strengthening and improving food security governance. Third, since existing research rarely involves county-level financial data, we collect and organize panel data, such as county-level financial support for agriculture, and apply econometric models, such as difference-in-differences, to empirically test theoretical predictions. This approach addresses the limited depth of existing research on the relationship between agriculture-related policies and local government behavior in supporting grain production, while simultaneously providing empirical evidence on the governance effects of agricultural policies. Fourth, we examine the dynamic effects of the RPMGC from a temporal perspective, analyzing whether it has long-term effects. This provides evidence to support the adjustment of vertical interest compensation policies and the implementation of horizontal interest compensation policies. Lastly, we analyze the differential effects of RPMGC under varying bonus distribution coefficients, industrial structures, and financial pressures, providing recommendations for further adjustments and improvements to policy details and content.

2 Policy background and theoretical analysis

2.1 Policy background

In the context of fiscal decentralization, there is a mismatch between local government routine power and financial power, which has led to the persistence of local financial gaps. The inherent risks of grain production and the externalities associated with food security have caused major grain-producing counties, which assume greater responsibility for grain production, to fall into the predicament of “increased grain production leading to greater resource depletion, more lost benefits, and higher opportunity costs.” The food resource advantages of the major grain-producing counties have instead become a heavy burden on their finances. The significant imbalance of interests, combined with the distortion of incentives caused by the “promotion tournament,” undermined local governments' incentives to support grain production, local governments were both unwilling and unable to allocate additional funds to support grain production, leading to a consistent decline in China's grain output from 1998 to 2003, which posed a serious threat to food security.

To address the issue of “inverted grain production and fiscal revenue” in major grain-producing counties and to enhance the government's motivation to promote grain production, China initiated a pilot project to build financial resources in these counties starting in 1990. This project increased financial inputs to support agriculture in the 13 counties with the highest grain production or the largest contribution to grain production (Wang, 1993). China issued “No. 1 central document” for 2005, calling for “incentives and subsidies to be provided to major grain-producing counties through transfers based on factors such as the area of grain sown, yield, and the volume of commodities.” To implement the spirit of “No. 1 central document”, the Ministry of Finance issued the “Measures of the Central Government to Reward Major Grain-Producing Counties” in April 2005. RPMGC outlines the objective of “mobilizing the incentives of local governments to support grain production” and provides details regarding the shortlisting criteria, incentive factors and weights, bonus distribution coefficients, the distribution and use of funds, as well as the management and supervision of these funds. In particular, it specifies that incentive funds for large grain-producing counties are calculated based on factors such as the volume of grain commodities, grain production, and the area sown with grain, with different incentive coefficients applied on a provincial basis. Furthermore, it is specified that incentive funds, as a financial transfer coordinated by county financial arrangements, shall not be used for unrealistic performance or image projects. Additionally, incentives will be suspended for grain-producing counties that fail to meet the monitoring criteria. The incentive fund for major grain-producing counties has increased annually, rising from 5.5 billion yuan in 2005 to 57.1 billion yuan in 2024, playing a positive role in alleviating the financial difficulties of major grain-producing counties.

2.2 Theoretical analysis and hypothesis proposed

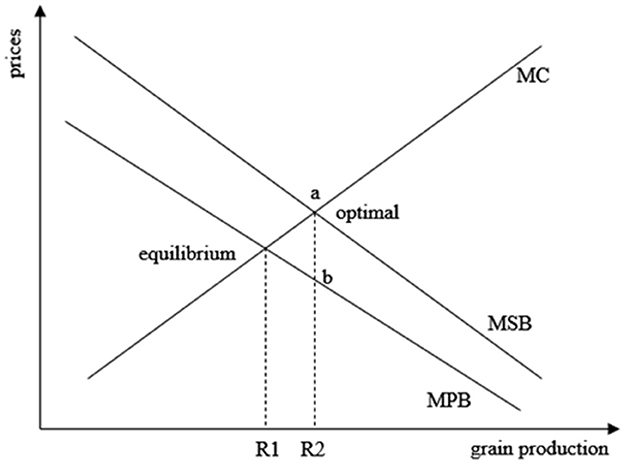

An important rationale for intergovernmental transfers is that local governments generate positive externalities in the provision of public goods, leading to a “spillover” of benefits. Without transfers to compensate for the loss of these benefits, the local government's pursuit of maximizing its own benefits may result in an insufficient supply of public goods and a loss of efficiency. grain is a quasi-public good of strategic significance with clear positive externalities, and ensuring food security is a shared responsibility between the central and local governments, including shared financial responsibility. However, in China's regional division of labor, large grain-producing counties often bear a disproportionate responsibility for food security, leading to higher financial obligations for grain production, which in turn limits their development opportunities. To address the externalities arising from food security in large grain-producing counties, the central government should provide transfer payments or subsidies to internalize these externalities. As shown in Figure 1, MPB and MC represent the marginal benefit curve and the marginal cost curve for the grain supply region, respectively, while MSB represents the marginal benefit curve for society as a whole. Due to the positive externality, MPB is smaller than MSB. R1 represents the grain production decision made by the grain supply region without considering the marginal social benefit of grain, where marginal benefit equals marginal cost, resulting in the maximization of benefit for the grain supply region. However, efficiency requires that marginal cost equals marginal social benefit, at which point grain production reaches R2. It is not difficult to find that in the absence of internalizing grain externalities, grain-supplying regions lack the incentives and motivation to increase grain production inputs, resulting in grain supply falling short of the optimal level required by society. However, if the central government or beneficiary regional governments provide transfer payments (equivalent to the marginal external benefit in the optimal state, i.e., the ab distance in the figure) to grain-supplying regions, compensating for their pro-duction and opportunity costs, it may incentivize these governments to increase in-vestments in grain production and improve governance of food security, thereby ensuring the achievement of national food security. Figure 1 illustrates the process of internalizing externalities.

RPMGC serves as vertical compensation for regions whose interests have been adversely affected by assuming responsibility for grain production, functioning as a typical transfer payment from the central government. The incentive funds are general transfers, which can be used flexibly by county governments to address local needs, with incentive standards ranging from 7 to 90 million yuan. These funds undoubtedly provide significant support for county-level finances. Major grain-producing counties facing financial difficulties due to fiscal decentralization and grain production often possess natural resource advantages and grain production competitiveness, providing stronger incentives to pursue incentive funds. Simultaneously, the policy stipulates that incentive funds are linked to the grain commodity volume, production, and sown area over the previous 5 years, as well as the previous year's performance evaluation score. A dynamic incentive mechanism is employed to select the shortlisted award-winning counties. This framework enhances the assessment and accountability authority of the central government as the principal, while simultaneously bolstering the sense of responsibility and mission among local governments as the agents, which better motivates and directs local governments to respond to RPMGC, thereby in-creasing financial investment in grain production and ensuring sustained access to incentive funds (Gong, 2015). Additionally, within China's food security governance system, receiving incentives for major grain-producing counties is accompanied by political recognition, which serves as an effective mental and promotional incentive for local governments, driving them to allocate more attention to grain production (Zeng, 2015). It is worth noting that, according to the “law of diminishing policy effects” in policy evaluation, the longer a policy is implemented, the weaker its initial objectives become. The impact of the RPMGC on CGISGP may gradually weaken over time, eventually disappearing. Some studies suggest a clear downward trend in the growth rate of reward funds, indicating that the policy's compensatory effects are diminishing (Gao and Wei, 2021). Based on the data collected on the reward funds for grain-producing counties, the funds have consistently increased, rising from 5.5 billion yuan in 2005 to 48.2 billion yuan in 2021. However, the growth rate of the reward funds has shown a gradual decline, from 54.55% in 2006 to 3.70% in 2021. Therefore, further discussion from a temporal perspective is needed to assess the dynamic effects of the grain-producing county reward policy and examine whether its effects are sustainable in the long term. Based on this, this paper proposes Hypothesis 1:

H1. RPMGC has a positive impact on CGISGP; however, the effect of the policy may diminish over time.

It is important to note that, considering the economic development differences and functional positioning across different regions, the incentive funds for major grain-producing counties are also linked to the financial status of each provincial-level area, with differentiated reward coefficients implemented. Specifically, Beijing, Tianjin, and Shanghai are not included in the reward scheme; the bonus distribution coefficients for Zhejiang and Guangdong provinces is set at 0.2; the bonus distribution coefficients for Liaoning, Jiangsu, Fujian, and Shandong provinces is set at 0.5; and the bonus distribution coefficients for other provinces is set at 1. This differentiated arrangement may imply that county governments in provinces with higher bonus distribution coefficients experience stronger incentive effects. Secondly, due to the pressure of the “promotion tournament”, county-level governments tend to prioritize goals such as GDP growth, fiscal revenue, and employment opportunities. In particular, county governments focused on secondary and tertiary industries may be more inclined to allocate limited fiscal resources to infrastructure projects that show quick results and obvious growth effects, thereby squeezing or even misappropriating investments in agricultural production, science, education, culture, health, and other sectors (Chen and Du, 2010). However, county-level governments that focus on agricultural development and grain production have a greater advantage in the competition for major grain-producing county rewards and are more motivated to increase fiscal support for agriculture, signaling their incentives for grain production to the central government in order to secure more transfer payments. Therefore, the effect of RPMGC is more pronounced in these regions. Additionally, county governments in China are responsible for promoting economic development, improving public services, ensuring grain production, and fulfilling other duties. For county governments with limited financial resources, the implementation of multiple tasks is a heavy burden, often exceeding their capacity. Striving for transfer payments from higher levels of government is a crucial method to secure wages, operational costs, and livelihood expenditures. Com-pared to county governments with lower financial pressures, those with greater financial strain have a stronger and more urgent demand for the incentive funds for major grain-producing counties, and they may invest more efforts in grain production to secure these incentives. Based on this, this paper proposes Hypothesis 2:

H2. The incentive effect of RPMGC on CGISGP may exhibit heterogeneity due to variations in bonus distribution coefficients, industrial structure, fiscal pressure, and other factors.

3 Research design

3.1 Sample description

To assess the impact of RPMGC on CGISGP, this paper collects and organizes annual panel data for county-level administrative units in China from 2000 to 2021. As of 2021, China has a total of 2,843 county-level administrative units. The sample selection process is as follows: First, considering the coverage of RPMGC and data quality issues, the sample excludes Beijing, Tianjin, Shanghai, Tibet, Taiwan, Hong Kong, and Macau. Second, considering the poor comparability in terms of grain production and fiscal systems between municipal district, forest regions, and other county-level administrative units, the former are completely excluded. Third, based on the 2021 administrative divisions of China, county-level administrative units that under-went changes during the study period (e.g., county-to-district or county-to-city adjustments) are excluded. Fourth, considering the availability of county-level data, particularly the severe lack of fiscal data, this paper manually collects and organizes county-level agricultural finance data, ultimately determining that the sample for analysis consists of 439 county-level administrative units. Among them, 222 are county-level administrative units that have continuously received the grain-producing county reward, while 217 are county-level administrative units that have never received this reward. Additionally, missing values are filled using linear interpolation, and extreme values are truncated, while all monetary variables were converted to real values using CPI with 2000 as the base year.

3.2 Selection of variables and data sources

3.2.1 Explained variable: CGISGP

Changes in the structure of fiscal expenditures pro-vide the clearest reflection of government policy preferences and the allocation of attention. The proportion of agricultural expenditure indicates the government's emphasis on agriculture and grain production sectors. Due to the absence of county-level statistical data on fiscal expenditures related to grain production, this paper draws on the research of Yang (2016), who suggests that a higher proportion of agricultural expenditure indicates greater emphasis by local governments on agricultural spending, Li and Zhou (2023), which uses fiscal agricultural support indicators to reflect whether the government's focus is on agriculture or non-agriculture sectors, and Yang and Lin (2024), which characterizes the government's economic attention to food distribution through the proportion of agricultural, forestry, and water affairs expenditure, and utilizes the proportion of agricultural expenditure—closely related to grain production—as a proxy for depicting the county-level government's motivation to promote grain production. Specifically, the higher the proportion of agricultural expenditure, the greater the motivation of county-level governments to promote grain production.

3.2.2 Explanatory variable: RPMGC

The treatment effect of the policy is captured through an interaction term between the dummy variable for major grain-producing counties and the dummy variable for the policy implementation time (post × treat). Based on the shortlisting criteria for major grain-producing counties, a total of 222 counties that have been continuously rewarded as major grain-producing counties and 217 counties that have never received such rewards were selected for the sample. The screening criteria for major grain-producing counties are an average grain production of more than 200 million kilograms over the past 5 years, and a grain commodity volume >5 million kilograms.

3.2.3 Control variables

Since fiscal agricultural expenditure is related to factors such as industrial structure, financial development, household savings, and government fiscal size, we refer to studies by Chen and Zhang (2008), Yang (2016), and Li et al. (2021) and select other variables that may influence agricultural expenditure based on these four aspects. To avoid the issue of post-treatment control variables potentially undermining the consistency of the estimation results, we follow the study by Li et al. (2016) and introduce the interaction term between the ex-ante variable (2004) and the time trend, while also reporting the regression results using time-varying control variables. Furthermore, drawing on the study of Cai et al. (2024), the product term of the selection criteria variables, including grain output, grain acreage, and rural population in 2004, is incorporated with the time trend to control for pre-existing characteristics influencing whether counties were rated as major grain-producing counties.

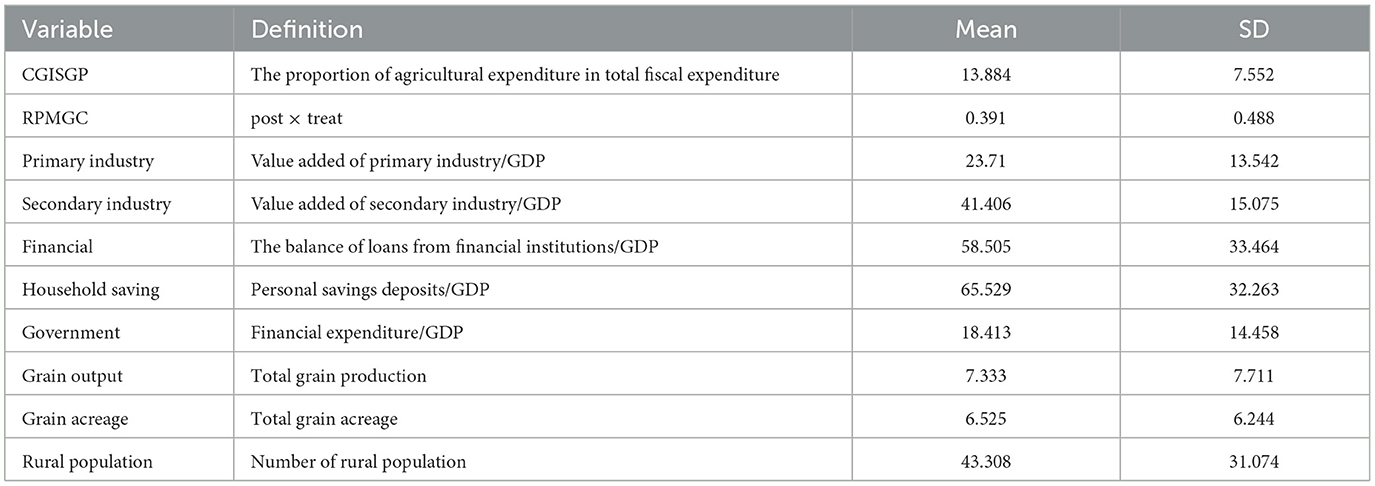

The data primarily originate from the China County Statistical Yearbook, China Statistical Yearbook, National Fiscal Statistics of Cities and Counties, the CSMAR Database, and historical statistical data from various provinces, cities, and counties. Table 1 provides an overview of the variable descriptions and descriptive statistics.

3.3 Model development

The Difference-in-Differences (DID) method is widely used in policy effect evaluation, with its main advantages being the effective control of unobserved time-invariant factors, and the assessment of the true impact of policies through a counterfactual framework, thereby reducing endogeneity issues. DID is particularly suitable for natural experiments, as it allows for more reliable causal inference by comparing the differences between the treatment and control groups, improving estimation efficiency, and reducing the interference of random fluctuations. This enables more accurate conclusions in policy effect evaluation. Therefore, this study adopts the DID method to assess the effect of RPMGC on CGISGP, the model is specified as follows:

In Equation 1, yct represents the explained variable, indicates CGISGP. postt × treatc is the explanatory variable, representing whether county c received the major grain-producing county reward in year t. Here, postt is a dummy variable indicating the period before or after the policy implementation, and treatc is a dummy variable indicating whether the county belongs to the treatment group. This paper primarily focuses on the coefficient β, which, if significantly positive, suggests that RPMGC effectively stimulates county-level governments to give greater attention to grain production. The regression model includes control variables xc, where μc represents county fixed effects, γt represents year fixed effects, and εct represents the random error term. The model in Equation (2) is augmented with the product term of the ex-ante variable and time trend (xc × ft), as well as the product term of the selection criterion variable and time trend identified in the previous section (pc × ft).

A key prerequisite for applying the difference-in-differences model is the satisfaction of the parallel trend assumption. This paper test the parallel trend assumption and investigate the dynamic impact of RPMGC on CGISGP. The model is specified as follows:

where Bk and Ak represent dummy variables for the Kth year before and after the policy's implementation, respectively. k = 5+ represents 5 years or more after the policy's implementation. To mitigate multicollinearity, the base period is set to 1 year prior to the policy's implementation. βk and ϑk represent the difference in CGISGP between the experimental and control groups in year K, compared to the pre-policy period (Period −1), respectively. The remaining symbols correspond to those in Equation 2.

4 Empirical findings

4.1 Benchmark analysis

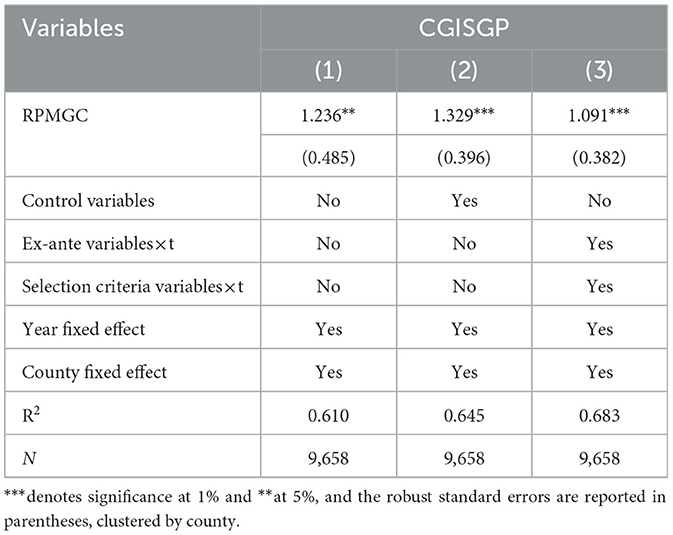

Table 2 presents the results of the benchmarking tests. Column (1) presents a univariate regression controlling for both year and county fixed effects. The coefficient of RPMGC is significantly positive at the 5% statistical level, which is a preliminary indication that the RPMGC has a significant positive effect on the CGISGP. Considering variables such as industrial structure, financial development level, household saving, and government fiscal size may have an impact on the CGISGP, we conduct the regression again on the basis of univariate regression by controlling for the above variables, and the results, as shown in column (2), show that the coefficient of RPMGC is still significantly positive at the 1% statistical level. Additionally, we further account for the interaction terms between ex-ante variables and the time trend, as well as the interaction terms between selection criteria variables and the time trend. The results, presented in column (3), show that the coefficient of RPMGC remains significantly positive at the 1% statistical level. Considering the three results, the effect of RPMGC implementation on CGISGP is both positive and significant, regardless of whether we control for the variables of interest. This is consistent with the results of the previous theoretical analysis and further supports the robustness of the estimation results in this paper.

4.2 Parallel trend test

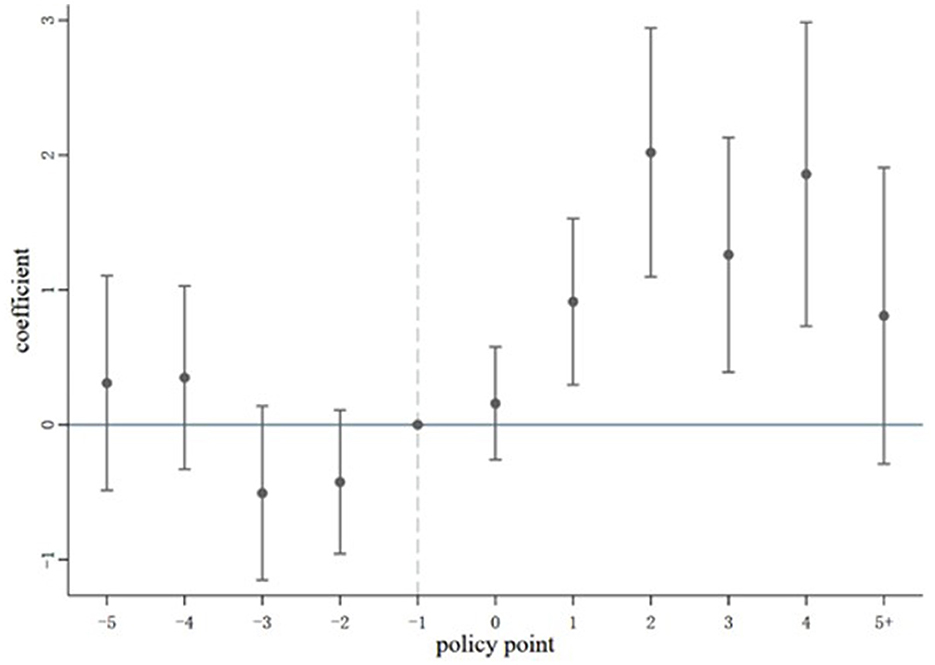

The implementation of the RPMGC has a certain degree of continuity, but its impact on CGISGP may not necessarily remain effective in the long term. Examining the dynamic effects of this policy from a temporal perspective not only provides decision-making support for optimizing vertical interest compensation, represented by the RPMGC, but also offers empirical evidence for accelerating the implementation of horizontal grain interest compensation. As shown in Figure 2, the horizontal coordinate is the relative time of RPMGC implementation. We designated the year before policy implementation as the policy base period, and 2005, the year of policy implementation, is represented by the number 0. The vertical coordinate represents the policy impact coefficient of RPMGC (with a 95% confidence interval). It is observed that the coefficient for the impact of RPMGC on CGISGP is not statistically significant prior to the policy implementation, but becomes statistically significant after the policy implementation. In other words, prior to the policy's introduction, no significant difference is observed between the CGISGP of grain-producing and non-grain-producing counties, and after the policy, RPMGC positively influences CGISGP. Therefore, the baseline regression estimates are shown to be both reliable and valid. The positive impact of RPMGC on CGISGP began to materialize in the first year following the policy's implementation, but over the long term, the policy's effect gradually diminished by the fifth year following its implementation, suggesting that the policy's effect is not sustained in the long term. The positive impact of RPMGC on CGISGP weakened as income from grain cultivation shrank and opportunity costs rose, implying that, to sustainably incentivize local governments to support grain production, further adjustments and improvements to the policy con-tent are necessary, particularly to enhance incentives that compensate for opportunity cost losses as much as possible.

4.3 Placebo test

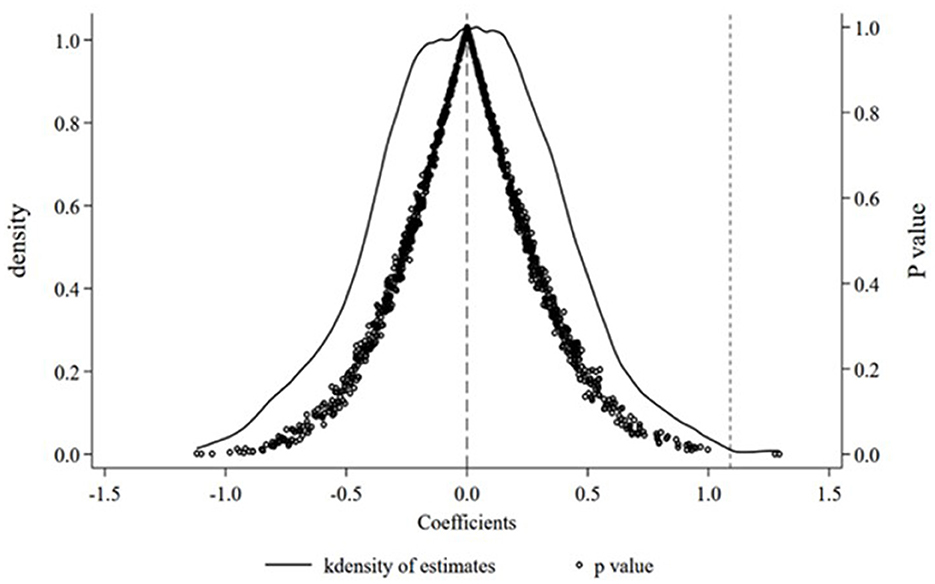

To eliminate the possibility of attributing the baseline regression findings to random chance, we conducted a placebo test. In this paper, instead of real major grain-producing counties, 222 counties are randomly selected from all samples and as-signed a randomly assigned dummy policy implementation time, and the model (2) equation is repeated for 1,000 regressions and the estimates are saved. Figure 3 plots the placebo test based on the simulation process described above. It can be observed that the mean value of the calculated coefficients is 0, with most of the p-values exceeding 0.1. Meanwhile, the estimated coefficient of 1.091 in the benchmark regression of Table 1 lies in the right tail of the distribution of pseudo-regression coefficients. In other words, the results of the benchmark regression are robust and reliable.

4.4 Robustness test

4.4.1 Endogeneity issue

The reverse causality between RPMGC and CGISGP in this paper is very weak, mainly because the experimental and control groups are divided on the basis of whether or not they receive the Grain Producing Counties Reward, and whether or not they receive the Grain Producing Counties Reward in the current year is closely related to the grain production and commodity volume in the previous years. For example, the basis for determining whether a county could receive the award in 2005 is that “the five-year average grain output from 1998 to 2002 was >200 million kilograms, and the volume of grain commodities was >5 million kilograms”, and CGISGP is measured using the share of agricultural expenditures in 2005, which meant that the reverse causality problem did not hold.

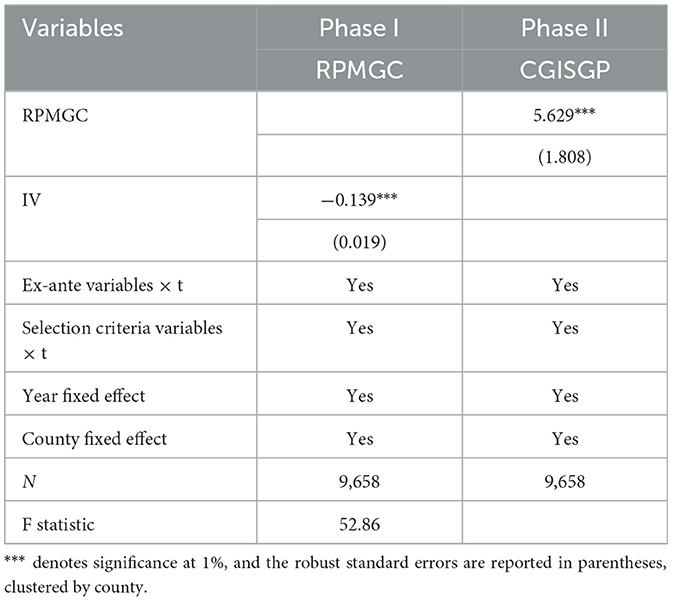

To enhance robustness, this study addresses the potential endogeneity issue using the parallel trend test and the instrumental variables approach. First, drawing on the research of Li and Jia (2020), if a higher CGISGP in the experimental group led to its classification as a major grain-producing county and subsequent reward allocation, there should have been a pre-existing difference in CGISGP between the experimental and control groups before the implementation of RPMGC. However, the results of the parallel trend test indicate that the two groups did not exhibit significant differences in CGISGP prior to RPMGC implementation, implying that the study's conclusions are not subject to reverse causality. Second, the interaction term between precipitation and post is chosen as an instrumental variable to test for endogeneity. On one hand, precipitation is determined by climatic and geographic conditions, with no causal relationship between CGISGP and precipitation, which aligns with the exogenous hypothesis. On the other hand, precipitation is closely related to grain production, influencing the likelihood that a county will be recognized as a major grain-producing county, which aligns with the correlation hypothesis. The results in Table 3 show that the coefficients of the instrumental variables in the first stage are significant at the 1% statistical level, with the F-statistic exceeding the critical value of 10, confirming that the instrumental variables satisfy the correlation conditions and that there is no issue with weak instruments. The second-stage regression results reveal that, after control-ling for endogeneity to the extent possible, the positive impact of RPMGC on CGISGP persists, confirming the robustness of the benchmark regression results.

4.4.2 Other robustness tests

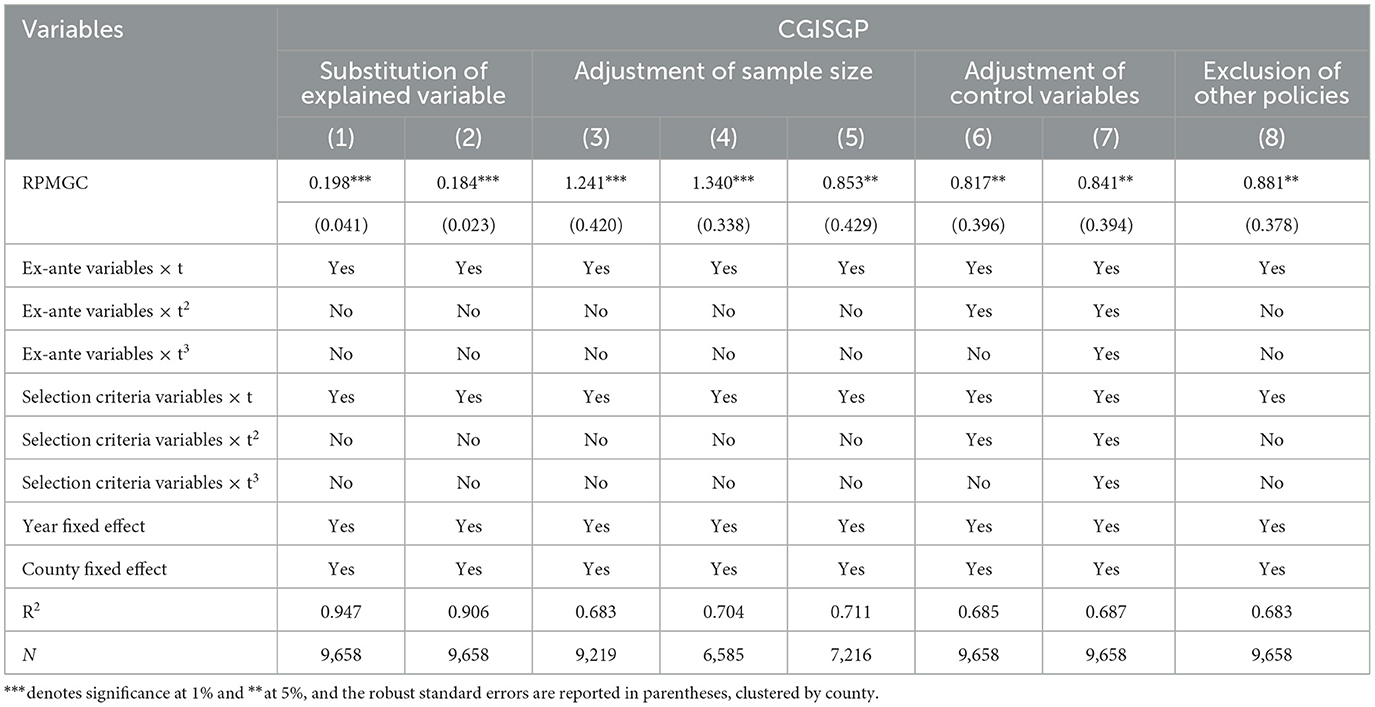

To ensure the robustness of the benchmark regression results, this study performs multiple robustness tests, including substituting explained variable, adjusting the sample size, adjusting control variables, and eliminating policy interference. The regression results are presented in Table 4. Total agricultural expenditures and the area of crops sown also reflect the importance placed by county governments on grain production. Column (1) replaces the explained variable with total agricultural expenditures, and the results indicate that the coefficient of RPMGC is still significantly positive at the 1% statistical level, and the findings of the benchmark regression are robust and reliable. Column (2) replaces the explained variable with the area of crops sown, and the results remain significantly positive, further confirming the robustness of the previous conclusions. Additionally, column (3) presents the results of a re-regression excluding the 2005 sample, the year of policy implementation, and shows that the coefficient of RPMGC is significantly positive. To avoid estimation bias caused by the implementation of the food security governors' accountability system, a re-regression is conducted excluding the 2015–2021 sample. The results in column (4) show that the coefficient of RPMGC is significantly positive. Furthermore, considering that mountainous counties have low grain production but potentially higher agricultural expenditure shares, and referencing the topographic relief data of China constructed by You et al. (2018), a re-regression is conducted after excluding the mountainous areas based on topographic relief. The results, shown in column (5), reveal that RPMGC significantly improves CGISGP. The conclusions of this paper re-main unchanged. It should be noted that columns (6) and (7) further control for “ex-ante variables × t2, ex-ante variables × t3, selection criteria variables × t2, selection criteria variables × t3”, and the results show that there is a significant incentive effect of RPMGC on CGISGP, proving that the benchmark regression results are robust. Additionally, considering the potential bias in estimation caused by the “three subsidies” policy on grain, policy interference is controlled for by introducing a dummy variable for the subsidy policy, and the results, shown in column (8), reveal that the coefficient of RPMGC remain positive and significant, indicating that the findings of this paper are robust and reliable.

5 Heterogeneity analysis

The above findings initially confirm that RPMGC serves as an incentive for CGISGP. This section further investigates the heterogeneous effects of RPMGC on CGISGP under different bonus distribution coefficients, industrial structures, and fiscal pressure scenarios.

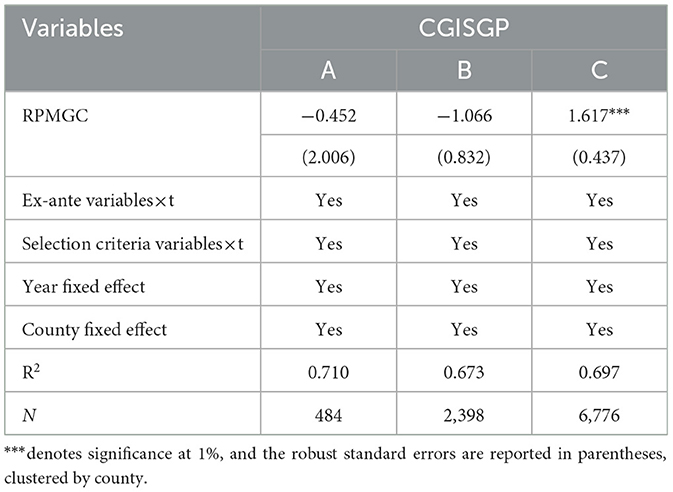

5.1 Heterogeneity analysis: bonus distribution coefficients

RPMGC establishes differentiated bonus distribution coefficients to allocate bonuses, directing them toward financially weaker counties to more effectively alleviate the financial difficulties in these areas. This differentiated bonus distribution pattern may influence CGISGP. This paper uses the bonus distribution coefficients specified in the policy text to divide the sample into three types of areas: A, B, and C, where the bonus coefficients for areas A, B, and C are 0.2, 0.5, and 1, respectively. The regression results are shown in Table 5. It can be observed that the effect of RPMGC on CGISGP varies significantly across the three types of areas. Specifically, the coefficient of RPMGC in category C areas is positive and statistically significant at the 1% level, while the test results for both category A and B areas are not statistically significant. This suggests that a higher distribution coefficient of the bonus corresponds to a more pronounced incentive effect of RPMGC on CGISGP.

5.2 Heterogeneity analysis: industrial structure

In China, local officials' promotions are, on one hand, closely tied to economic development, motivating them to actively promote the growth of secondary and tertiary industries to secure advancement. On the other hand, the strategic role of agriculture within the national economy, coupled with the importance of food security, dictates that ensuring stable grain production remains a key responsibility of local governments. Confronted with the dual pressures of economic development and food stabilization, local governments often adopt differentiated governance policies. Some studies have shown that local governments continue to prioritize the primary sector when engaging in fiscal governance (Lu et al., 2020). However, other studies have demonstrated a clear bias in local government expenditure structures toward the secondary and tertiary industries (Fu and Zhang, 2007).

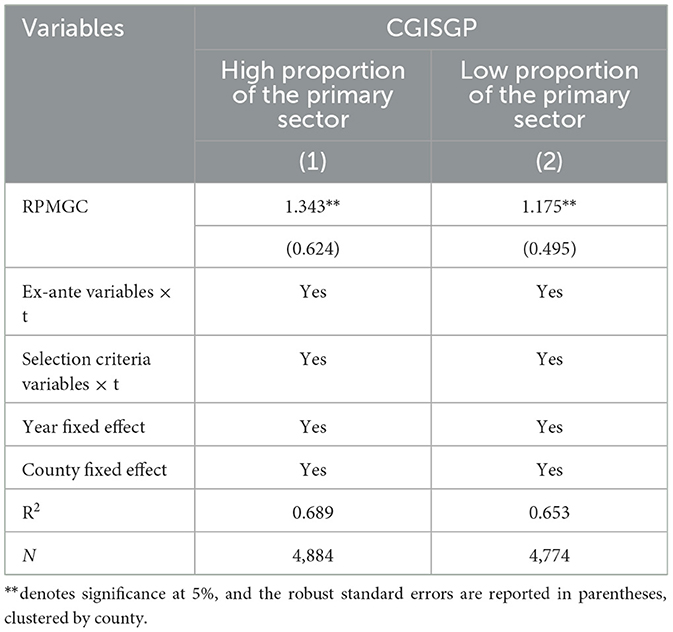

Regarding RPMGC, the incentive funds allocated by the policy exhibit a specialized focus, the performance evaluation mechanism encourages local governments to allocate a larger share of incentive funds to grain production. Under these conditions, local governments with a higher proportion of primary industry are more likely to al-locate greater financial resources to agriculture to support grain production, consequently receiving more incentive funds. Conversely, local governments with a higher proportion of secondary and tertiary industries are more inclined to focus on economic development and neglect agricultural development. This implies that the effect of the incentive policy may be diminished in such areas. The paper divides the sample into two groups for regression analysis based on the median proportion of the primary industry, and the estimation results (Table 6) indicate that the coefficient estimates for both groups are significantly positive. However, the incentive effect of the policies is more pronounced in counties with a larger proportion of the primary industry.

5.3 Heterogeneity analysis: financial pressures

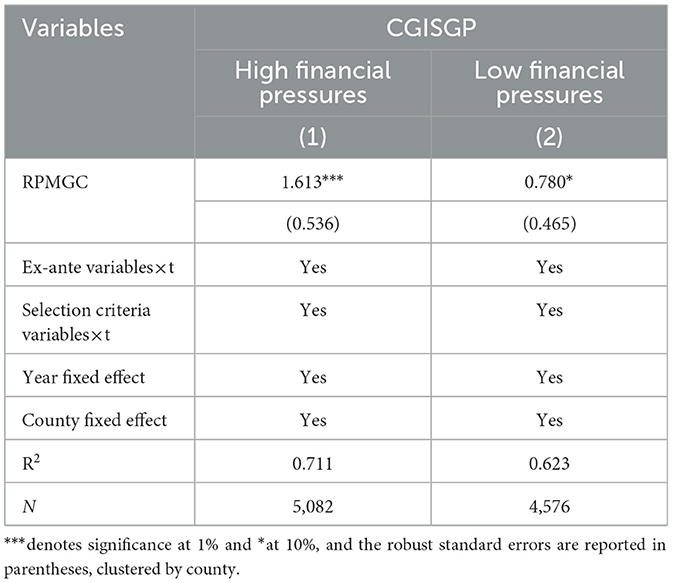

As discussed earlier, local governments exhibit varying degrees of dependence on transfers from higher levels of government, particularly those that are financially weaker. These governments shoulder greater expenditure responsibilities and, there-fore, have a more urgent need for transfers to alleviate financial pressures. It can be anticipated that the magnitude of financial pressures may, to some extent, influence the intensity of local governments' responses to RPMGC. Therefore, this paper measures local financial pressures as the proportion of the fiscal balance gap to fiscal revenue (Yang and Wang, 2021) and divides the sample into two groups for regression based on the median financial pressures. The results, as shown in Table 7, indicate that the coefficient estimates for both groups are significantly positive, suggesting that, regardless of the magnitude of financial pressures, RPMGC exerts a positive driving and incentivizing effect on CGISGP. Additionally, a comparison of the coefficient estimates in columns (1) and (2) reveals that the incentive effect of RPMGC is more pronounced in counties with high financial pressures, thereby confirming Research Hypothesis 2.

6 Conclusions and policy recommendations

Based on the analysis of the mechanism through which RPMGC influences CGISGP, this paper evaluates the actual effects and heterogeneity of the policy's implementation using the difference-in-differences (DID) method, based on 439 county-level panel data from China spanning the period 2000–2021. The results show that, first, RPMGC significantly enhances CGISGP, a conclusion that remains robust after several tests, including the parallel trend test, placebo test, and instrumental variables method, as well as after substituting explained variable, adjusting sample size, adjusting control variables, and excluding policy interference. Second, from a dynamic perspective, the incentive effect of RPMGC on CGISGP begins in the first year following implementation and gradually diminishes after the fifth year, indicating that the policy effect is not long-lasting. Third, the impact of RPMGC is closely linked to the structure of incentive funds: the higher the reward distribution coefficient, the more pronounced the policy effect. Furthermore, the policy's incentive effect on CGISGP is more significant in counties with a large proportion of the primary industry and high financial pressure. This suggests that RPMGC may incentivize CGISGP through direct financial rewards, guiding the flow of funds, and alleviating financial pressure, among other pathways.

Based on these findings, several policy implications can be drawn.

First, the adjustment and improvement of RPMGC should be accelerated. Specifically, a dynamic adjustment mechanism should be implemented, based on a five-year cycle, with joint multisectoral assessments of the policy's effects to enable timely adjustments to its direction and intensity. Additionally, the incentive funds for major grain-producing counties should be used effectively by increasing financial support and directing the policy to favor regions that are predominantly agricultural, economically weaker, and under greater financial pressure. This will help enhance the financial capacity of these areas and ensure that their finances adequately support grain production.

Secondly, accelerate the implementation of horizontal grain interest compensation. The responsibilities and division of labor for local food security should be clarified, and horizontal interest compensation between grain-producing and grain-consuming regions should be expedited. The RPMGC does not have long-lasting incentives for county governments to prioritize grain production, indicating that relying solely on unilateral compensation through central transfer payments is insufficient to address the interests lost by grain-producing counties. Therefore, on the basis of improving the compensation mechanism, it is essential to speed up the establishment of an intergovernmental horizontal transfer payment system, effectively balancing the responsibilities of grain-producing and consuming counties in food security, and encouraging the central government and local governments to actively participate in food security. In particular, efforts should be made to establish a food supply-demand linkage and benefit-sharing mechanism between consuming and grain-producing counties, coordinating data on food production, circulation, and consumption. Substantial progress should be made in advancing horizontal interest compensation, while expanding cooperation between the two sides in areas such as industry, talent, technology, and information, thereby motivating grain-producing counties to actively engage in food production, transportation, and storage.

Third, strengthen the “endogenous motivation” of grain-producing counties. Grain-producing counties should actively expand beyond the single domain of grain production and extend vertically into high-value-added areas such as deep processing, brand building, and market marketing. By lengthening the industrial chain, enhancing the value chain, and improving the supply chain, they can create an efficient transformation pathway from grain resources to industrial advantages and, ultimately, economic momentum. This approach will achieve value-added and sustainable utilization of grain resources. Increasing the processing conversion rate of grain at the point of origin will transform the advantages of grain production into industrial competitive advantages, leaving more post-harvest value-added profits and employment opportunities locally, thereby achieving a win-win situation for both increased grain production and economic development.

Finally, it should be noted that this study has several shortcomings and limitations. Since China has not published a list of large grain-producing counties or the corresponding incentive amounts, the list of these counties can only be inferred from the selection criteria, while the incentive amounts remain unquantifiable. Furthermore, a significant amount of data on financial support for agriculture and the characteristics of county-level officials is missing, which makes it challenging to test the specific pathways through which RPMGC incentivizes CGISGP. These limitations also restrict the scope of the empirical model that can be chosen. In the future, efforts will be made to collect more data on financial support for agriculture and the characteristics of county-level officials, in order to conduct further in-depth research on the theory of incentivizing local governments to prioritize grain production.

Data availability statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/supplementary material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author/s.

Author contributions

XB: Conceptualization, Formal analysis, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing, Data curation, Visualization, Methodology, Software. XW: Writing – original draft, Methodology, Writing – review & editing. XL: Writing – original draft, Formal analysis. YZ: Conceptualization, Funding acquisition, Project administration, Resources, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declare that financial support was received for the research and/or publication of this article. This research was funded by grants from the Chinese Academy of Agricultural Science and Technology Innovation Program (10-IAED-01-2025) and the National Social Science Foundation of China (21BJY131).

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The author(s) declare that no Gen AI was used in the creation of this manuscript.

Publisher's note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Abbreviations

RPMGC, The reward policy for major grain-producing counties; CGISGP, County governments' incentives to support grain production.

References

Cai, Y., Zhou, J., and Yuan, W. (2024). Data factor sharing and urban entrepreneurial vitality: empirical evidence from public data openness. J. Quantit. Technol. Econ. 8, 5–25. doi: 10.13653/j.cnki.jqte.20240619.004

Chen, A., and Du, J. (2010). Fiscal expenditure and rural-urban income gap in China. Statist. Res. 11, 34–39. doi: 10.3969/j.issn.1002-4565.2010.11.005

Chen, S., and Zhang, J. (2008). Fiscal expenditure efficiency of local governments in China: 1978-2005. Soc. Sci. China 4, 65–78+206.

Chu, D., and Fei, M. (2021). Vertical fiscal imbalance, transfer payment and local governance. Finance Trade Econ. 2, 51–66. doi: 10.1515/cfer-2021-0010

Fu, Y., and Zhang, Y. (2007). Chinese-style decentralization and fiscal expenditure structural bias: the cost of competing for growth. J. Managem. World 3, 4–12+22. doi: 10.19744/j.cnki.11-1235/f.2007.03.002

Gao, M., and Wei, J. (2021). Accelerating the construction of national grain security industrial belt: development orientation and strategic conception. Chin. Rural Econ. 11, 16–34.

Gong, W. (2015). The project system and the rectification of the externality of food production. Open Times. 2, 103–122.

Jiang, W., Li, X., Liu, R., and Song, Y. (2022). Local fiscal pressure, policy distortion and energy efficiency: Micro-evidence from a quasi-natural experiment in China. Energy 254:124287. doi: 10.1016/j.energy.2022.124287

Li, G., and Jia, F. (2020). Reform of fiscal hierarchy and reconstruction of tax enforcement incentive:evidence from “pmc” reform in fiscal. J. Managem. World. 8, 32–50. doi: 10.3969/j.issn.1002-5502.2020.08.005

Li, N., and Zhou, Q. (2023). Embedded mechanism inquiry: transformation of the main responsibility for food security in withdrawing counties and setting up districts. Issues Agricult. Econ. 3, 72–87. doi: 10.13246/j.cnki.iae.2023.03.002

Li, P., Lu, Y., and Wang, J. (2016). Does flattening government improve economic performance? Evidence from China. J. Dev. Econ. 123, 18–37. doi: 10.1016/j.jdeveco.2016.07.002

Li, S., and Li, G. (2024). Fiscal decentralization, government self-interest and fiscal expenditure structure bias. Econ. Anal. Policy. 81, 1133–1147. doi: 10.1016/j.eap.2024.01.014

Li, T., and Du, T. (2021). Vertical fiscal imbalance, transfer payments, and fiscal sustainability of local governments in China. Int. Rev. Econ Finance 74, 392–404. doi: 10.1016/j.iref.2021.03.019

Li, T., Yang, F., Zhang, H., and Lin, Q. (2025). The effectiveness and mechanisms of China's grain support policies in relation to grain yield—an evaluation of a wide range of policies. Foods 2:267. doi: 10.3390/foods14020267

Li, Y., Chen, A., and Cao, C. (2021). Sequential decentralization and regional fiscal expenditure structure —an empirical analysis based on the practice of provincial decentralization in China. Public Finance Res. 7, 53–65. doi: 10.19477/j.cnki.11-1077/f.2021.07.007

Lu, S., Li, X., and Lu, H. (2020). The characteristics of local governments' fiscal governance: evidence from the textual analysis of the Chinese government work reports. Public Finance Res. 4, 99–114. doi: 10.19477/j.cnki.11-1077/f.2020.04.010

Luo, S., and Zhang, J. (2024). The reward of bumper harvests: fiscal incentives and grain production growth. Chin. Rural Econ. 8, 27–46. doi: 10.20077/j.cnki.11-1262/f.2024.08.003

Tai, Q. (2014). Tax reform, fiscal revenues, and farmer' income evidence from two waves of Chinese agricultural tax. Fudan J. Humanit. Soc. Sci. 7, 265–286. doi: 10.1007/s40647-014-0015-1

Wang, S., Wu, H., Li, J., Xiao, Q., and Li, J. (2024). Assessment of the effect of the main grain-producing areas policy on China's food security. Foods 5:654. doi: 10.3390/foods13050654

Wang, X. (1993). Overview of the pilot situation of supporting the construction of financial resources in large grain-producing counties with financial support for agricultural working capital. China State Finance. 8, 7–9. doi: 10.14115/j.cnki.zgcz.1993.08.014

Wang, Z., Chen, X., and Shi, L. (2025). Incentive policies for large grain-producing counties and county-level grain production in China–an analysis based on spatial double-difference models. J. Agrotech. Econ. 2, 63–91. doi: 10.13246/j.cnki.jae.20240618.002

Wu, J., and Zhang, X. (2023). Can grain production incentives promote farmers' incomes and county economic development? A quasi-natural experiment based on the incentive policy for large grain-producing counties. J. Finance Econ. 1, 124–138. doi: 10.16538/j.cnki.jfe.20221022.402

Xu, T., and Hou, Y. (2010). The empirical analysis on the stabilization effect of transfer on local fiscal revenue: based on China provincial, prefectural and county panel data. J. Public Managem. 1, 47–57+125.

Yang, D., and Wang, D. (2021). Fiscal pressure, strategies of sub-provincial governments and the structure of fiscal expenditure. Public Finance Res. 8, 47–62. doi: 10.19477/j.cnki.11-1077/f.2021.08.002

Yang, L. (2016). Do fiscal transfers increase local agricultural public expenditures? Econ. Rev. 5, 148–160. doi: 10.19361/j.er.2016.05.11

Yang, Y., and Lin, W. (2024). Does the fiscal reform of province governing county promote county grain production? evidence from a quasi-natural experiment. Chin. Rural Econ. 6, 152–172+191–193. doi: 10.20077/j.cnki.11-1262/f.2024.06.008

You, Z., Feng, Z., and Yang, Y. (2018). Relief degree of land surface dataset of China (1 km). J. Global Change Data Discov. 2, 151–155+274–278. doi: 10.3974/geodp.2018.02.04

Zeng, M. (2015). Incentive effect of fiscal transfer: why does the local government support grain production: field survey from main grain production region. J. Nanjing Agricult. Univer. 3, 60–68+123.

Zhang, S., and Wang, Z. (2023). Effects of vertical fiscal imbalance on fiscal health expenditure efficiency—evidence from China. Int. J. Environm. Res. Public Health 3:2060. doi: 10.3390/ijerph20032060

Zhang, X., Chen, D., Lu, X., Tang, Y., and Jiang, B. (2021). Interaction between land financing strategy and the implementation deviation of local governments' cultivated land protection policy in China. Land 8:803. doi: 10.3390/land10080803

Zhang, X., Yu, X., and You, L. (2020). Does the granary county subsidy program lead to manipulation of grain production data in China? China Econ. Rev. 62, 101347. doi: 10.1016/j.chieco.2019.101347

Zhao, H., and Hou, S. (2021). Did the incentive policy for large grain-producing counties promote county food production?–Evidence from Henan County Panel Data. Sub Nat. Fiscal Res. 11, 75–85.

Zhao, H., Liu, Y., and Li, Z. (2024). The impact of the major grain -producing counties reward policy on county grain production: effective motivation or limited welfare. Reform 6, 93–107.

Zhao, W., and Li, G. (2016). Does central financial transfer payments reduce urban-rural income gap? J. Nanjing Agricult. Univer. 6, 141–151+156.

Zheng, Z., and Song, H. (2023). Improving the benefit compensation mechanism for main grain producing areas: basis, problems, and policy optimization. Res. Agricult. Moderniz. 2, 214–221. doi: 10.13872/j.1000-0275.2023.0039

Keywords: RPMGC, CGISGP, food security, transfer payments, policy

Citation: Ba X, Wang X, Luo X and Zhong Y (2025) Assessment of the effect of the reward policy for major grain-producing counties on county governments' incentives to support grain production. Front. Sustain. Food Syst. 9:1600573. doi: 10.3389/fsufs.2025.1600573

Received: 26 March 2025; Accepted: 29 May 2025;

Published: 18 June 2025.

Edited by:

Justice Gameli Djokoto, Dominion University College, GhanaReviewed by:

Wentai Bi, Bohai University, ChinaLongzhen Min, Sichuan Agricultural University, China

Copyright © 2025 Ba, Wang, Luo and Zhong. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Yu Zhong, emhvbmd5dUBjYWFzLmNu

†These authors have contributed equally to this work

Xuezhen Ba

Xuezhen Ba Xizhao Wang

Xizhao Wang Xi Luo2

Xi Luo2