- 1College of Forestry, Kerala Agricultural University, Thrissur, Kerala, India

- 2Department of Biotechnology, University of Mysore, Mysuru, Karnataka, India

- 3Division of Biological Sciences, School of Science and Technology, University of Goroka, Goroka, Papua New Guinea

- 4Department of Environmental Science, Central University of Kerala, Kasaragod, Kerala, India

Wild edible plants (WEPs) are integral to many local food systems. Historically, they improved the nutrition, dietary diversity and food security of indigenous communities. Integrating WEPs into local food systems represents a sustainable approach to reducing the carbon footprints of intensive farming and facilitating a shift toward more resilient food systems. Wild foods, rich in vitamins and minerals and a source of ethnomedicines, can enhance diets and promote health, longevity, and sustainability, especially among nutritionally disadvantaged groups. High biodiversity, local accessibility, cultural acquaintance, and low input needs are intrinsic features of wild foods. However, unsustainable harvesting and overexploitation, particularly in the tropical region, have led to depletion of these ecologically niche resources and their habitats, underscoring the need for conservation efforts to protect them. WEP research has gained momentum recently, with India and China emerging as forerunners in this domain. Considerable developments are also underway in the USA, Europe, and Africa. Such endeavors transect disparate fields, including food science and technology, plant sciences, sustainable agriculture, and phytochemistry. However, more efforts are essential in sustainable harvesting, plant domestication, valorization, and conservation.

1 Introduction: food system transition and local food systems

Food deficits and malnutrition are major global concerns that affect the health and well-being of millions of people. Afshin et al. (2019) attributed 20% of premature disease-related deaths and the increasing healthcare costs to poor quality diets. With the world population projected to reach an estimated 9.77 billion by 2050, up from the current 8.186 billion (UNPD – United Nations Population Division, 2024), diet-related health issues, greenhouse gas emissions, environmental degradation, biodiversity loss, and waste generation are likely to aggravate (FAO, 2021). FAO (2024) data indicate that nearly 282 million people in 59 countries faced acute food insecurity in 2023, and 582 million people may be chronically undernourished in 2030. Furthermore, the grand Anthropocene challenges such as climate change, urbanization, and increasing consumption levels, especially in the developed world, are likely to exacerbate and impede progress in achieving Sustainable Development Goals (specifically SDGs 2, 3 and 15: Zero Hunger, Good Health and Wellness, and Life on Land, respectively). The Low- and Middle-Income countries are particularly vulnerable in this respect.

Food systems, which evolved successfully during the 20th century, are cardinal to achieving SDGs and staying within the “planetary boundaries” (Rockström et al., 2024). However, many food systems are already at risk as they are unable to absorb or adapt to the physical stresses that will increase in the coming decades (Fanzo et al., 2021). The mounting prominence of food systems in policy dialogues underscores the recognition that systemic reforms are essential to enhance access to sustainable and nutritious foods (IFPRI, 2021). To ensure just and equitable livelihoods, the food systems must be transformed to integrate food security, nutrition, ecosystem services, climate change mitigation/adaptation, and rural prosperity (FAO, 2021).

Addressing the vulnerabilities of fragmented systems requires developing and reinforcing local food systems (LFS), which are deeply ingrained in the socio-ecological contexts and cultural traditions. To achieve broader systemic transformation, LFS, which includes wild foods, must expand their scope and impact—yet this “scaling up” process remains a persistent challenge (Mount, 2012). The key barriers to upscale LFS and the consumption of wild edibles include problems related to the consistent availability of the products, perishability, high costs of collection, and low returns to the collectors and sellers. Furthermore, the types of issues involved and their governance may be local or region-specific, with profound variations among the subcategories (e.g., fruits, nuts, leaves, and other products), requiring solutions at the regional or local level (Borelli et al., 2020).

According to Lulekal et al. (2011), approximately 1 billion people consume wild foods daily, making it a vital component of the global food basket. Apart from wild edible plants (WEPs), wild edibles encompass fungi, mushrooms, algae, and lichens, as well as insects and animals. Some of the best WEPs, however, are edible weeds (alimurgic plants) that have a long history of use and wide distribution, such as Taraxacum officinale, Sonchus arvensis, S. oleraceus, Chenopodium album (Åhlberg, 2019). Edible weeds and other WEPs provide health-promoting raw materials for food during times of famine or hardship. Experimental research has demonstrated that they contain health-promoting substances, many of which also have therapeutic values against some diseases. Managing edible weeds as alternative crops is a context-dependent option, which can be attempted on a case-by-case basis (Menalled and Ebel, 2025). A growing interest in edible weeds nevertheless appears to be a worthwhile research strategy for improving sustainability in agriculture, with advantages that span agroecosystems, food systems, and public health (Borsari and Vidrine, 2024). This paper provides an overview of current trends in wild edible plant research, focusing on the regional distribution of publications, thematic areas, and emerging directions for future research.

2 Literature survey and key findings

A quick search of the Web of Science Core Collection (WoS) with keywords such as “wild edibles OR wild edible plant OR wild edible herbs OR wild edible fruits OR wild edible mushrooms OR wild edible vegetables” on 5 July 2025 returned 3,177 records, with approximately a third (1,050) on wild fruits and a fourth (843) on wild mushrooms, implying the dominance of these two categories in the research since 1970. The metadata were downloaded, and the titles and abstracts were evaluated for consistency/duplication, followed by the full texts of key articles. The results indicate that among the dominant countries, India leads the table with 440 studies on WEPs, followed by China, the USA, Turkey and Spain (Figure 1A). The temporal pattern showed that the number of studies has increased almost linearly over the years (Figure 1B), implying a growing global interest in WEP research. Foraging WEPs, thus, is a re-emerging practice with increasing popularity worldwide (Garekae and Shackleton, 2020). This global interest in WEPs foraging, however, may be asymmetrical across the urban–rural divide. In cities, it raises questions about the safety of foraging WEPs for human consumption, due to the potential exposure of plants to higher levels of pollutants (Amato-Lourenco et al., 2020). Yet, with the rapid urbanization, tourism, and trade, the Zhuang ethnic people’s food culture in Guangxi, China, including the consumption of wild edible plants, has become an attractive aspect of urban development (Liu et al., 2023). Foraging WEPs is markedly more prevalent in the rural areas, especially in India and China, with very large tribal populations (Mamo, 2025). The focal research areas included food science and technology, plant sciences, crop husbandry, and phytochemistry (Figure 1C).

Figure 1. (A) Geographic distribution of studies on wild edible plants published since 1970 (until June 2025); (B) Temporal trend in publication frequency over the same period; and (C) Major thematic research areas addressed in the literature with frequency of publications.

Many publications have reported comprehensive syntheses on the food, animal feed, and pharmacological uses of WEPs, and the WoS search returned 252 review articles. A large section of the publications, however, dealt with narrow geographic regions, such as a sub-region or a district within a country, and comprehensive global treatments are few.

2.1 Prehistoric uses

Wild edible plants are crucial sources of food, feed, and drugs, essential to human survival and cultural heritage in Asia, Africa, Latin America and Europe, for a long time. From the earliest hunter-gatherers to various stages of human adaptation, wild plants have been important, and many people throughout the world have relied on them for diet and medicine (Ferreira et al., 2016). For example, in Amazonia, indigenous fruit trees were domesticated and integrated into primitive farming systems through the “dump heap” approach or incidental route to domestication, which gave rise to the primitive Amazonian homegardens (Miller et al., 2006). The indigenous people of the Western Ghats traditionally had a profound knowledge of the local forest plants, on which they were intimately dependent, and sustainable utilization was integral to the tribal life (Sreekumar et al., 2020). There is ample proof showing that WEPs have been consumed in Mediterranean countries since prehistoric times, and their foraging and usage in European and Mediterranean diets have been growing continually (Åhlberg, 2021; Capurso, 2024). D’Agostino et al. (2024), based on a microscopic analysis of human dental calculus from two Italian burial caves, demonstrated that the consumption of wild edible fruits and the use of plant-based raw materials were widespread in central Italy during the Copper-Middle Bronze Age. The inhabitants had a detailed knowledge of the phytoecological context of their settlement areas, including the relative biodiversity.

Although wild foods represent a multifaceted and fascinating aspect of local bio-cultural and food heritage, traditional knowledge and practices linked to WEPs are rapidly changing and are severely endangered by globalization, even in the most remote areas of the globe (Pieroni, 2021). Nonetheless, a spectacular revival of interest in the foraging, processing, and consumption of wild foods is being observed in many health-conscious societies, mainly pushed by the keenness of the communities to “reconnect with nature” and have safe, “natural,” local, and healthy foods. This is of interest in the context of integrating wild food knowledge into LFS to achieve ecological and social sustainability.

2.2 The suite of species involved

The spectrum of WEP species is varied and shows large heterogeneity across regions. Of the 15,000 angiosperm species reported from India, 1,403 from 184 families have been used directly or indirectly as foodstuffs (Ray et al., 2020). Sreekumar et al. (2020) compiled a list of 237 wild fruit plants from the Western Ghats of India, including 37 endemic and 11 red-listed plants. In the cold trans-Himalayan region of India, Rana et al. (2012) documented 164 WEPs belonging to 100 genera, which are mostly eaten as vegetables. In Ethiopia, the rural communities sporadically consumed 100s of WEPs. But relatively fewer plant species are being used lately in Southern Ethiopia, signifying a decline in plant use knowledge (Getachew et al., 2013). Sub-global appraisals show that ethnic and traditional people consumed around 200 taxa (Grivetti and Ogle, 2000). WEPs also encompass an array of life-forms, ranging from annual and perennial herbs, vines, and grasses to shrubs and trees. Ali-Shtayeh et al. (2008) found that leaves (24%) and stems (21%), consumed raw or cooked, were the most commonly ingested plant parts in Palestine. Many pteridophytic species (ferns and lycophytes) are also known to be edible (either rhizomes or leaves), and 23 edible ferns were reported from Northeast India (Yumkham et al., 2017).

Wild edible species generally occur as self-sustaining populations within natural or semi-natural ecosystems such as forests, grasslands, and barren fields, and represent a vital component of biodiversity. They thrive without direct human intervention (Heywood, 2011). The spatial spread and market worth of WEPs are species-specific and context-dependent. Indigenous fruit species in Odisha, India, which are constituents of the mixed deciduous forest ecosystem, were sporadically distributed with a density of 10–15 species ha−1 (Mahapatra and Panda, 2012). The regeneration of wild edible fruit (WEF) tree species is generally poor due to overharvesting, which often involves highly destructive procedures (Muraleedharan et al., 2005).

2.3 Diet diversity, nutritional quality, and livelihood security

Although forest-based food resources provide only a small amount of the world’s caloric intake (0.6%), they significantly enhance nutrition and diet diversity (Ickowitz et al., 2014). Staple foods, which are deficient in vital micronutrients, are insufficient to effectively address the issue of micronutrient deficiencies or “hidden hunger” (Ickowitz et al., 2019). For many populations, therefore, local foods, including WEPs, complement diets with essential nutrients (Grivetti and Ogle, 2000; Keller et al., 2005). Rich in vitamins, fibers, minerals, and fatty acids, besides having medicinal properties, WEPs are thus crucial for the rural and aboriginal populations (Rumicha et al., 2025). In eastern India, per capita WEF consumption was generally low, yet it significantly enriched the tribal food basket, which was diverse and nutritious (Mahapatra and Panda, 2012). Due to little or no exogenous inputs for growth promotion, WEPs can also be expected to be of superior quality. WEPs are ingested in various ways, such as pickles, spices, fruits, desserts, salads, and cold and hot drinks. According to local traditions, they can be boiled, fried in fat, eaten raw, or rolled into vegetables (Pieroni, 2005).

However, for most of these species, little is known about their nutritional value, safety, availability, use, and consumption patterns, besides their impact on human health and the risk of non-communicable diseases (Termote et al., 2014). Many rural households depend on WEP gathering not only to meet their consumption requirements and to sustain food and nutritional security, but also as a source of employment and income. Leaves, fruits, and nuts are often collected and sold in the local markets of northeastern India (Figure 2) and in the semiarid lowlands of southern Ethiopia and other regions (Duguma, 2020). WEPs also provide for essential household needs such as fuelwood, construction materials, shelter and livestock fodder, besides supporting livelihoods. The fodder resources, in turn, reduce dependence on commercial animal feeds and contribute to more cost-effective and sustainable livestock production (Tebkew et al., 2018).

Figure 2. Wild and cultivated fruits, nuts, and vegetables in the Namsai market, Arunachal Pradesh, India (photo: BM Kumar).

2.4 Supplementary role of WEPs, data gaps, and the need for integration into National Planning

WEPs are vital in many traditions, contributing significantly to regular nourishments, predominantly during food scarcity or in times of crop failures. They act as a safety net and coping mechanism against hunger and malnutrition (Bharucha and Pretty, 2010), bridging seasonal food gaps, complementing staple diets, and serving as emergency food sources for the rural poor, especially during drought, conflict, or famine (Borelli et al., 2020). However, wild foods and their actual and potential contributions to nutritional security have rarely been studied or considered in nutrition and conservation programs (Termote et al., 2014). Consequently, there is a paucity of information on WEPs at the national level in many parts of the world. Given this lack of robust, reliable, and accessible food composition data, the role of WEPs in food security and nutrition strategies, besides their overall importance in national economies, remains under-appreciated. Users of such data also need to be certain about the reliability of the species-level identification and nomenclature of the WEPs, which is particularly problematic for lesser-known wild or locally cultivated plants (Nesbitt et al., 2010). Information available on the biology and ecology of WEPs, as well as the dynamics of their use and climate change impacts now and in the future, is also scarce (Borelli et al., 2020).

Knowledge regarding biocultural food heritage, important for marginalized communities, may also be of value, particularly in evolving policies and governance initiatives that might facilitate the maintenance of biocultural food heritage, development of climate-resilient agro-ecological techniques and product valorization (Pieroni, 2021). A greater understanding and appreciation of the nutritional value of wild foods and their contribution to food and nutritional security, especially by decision-makers, will lead to enhanced inclusion of WEPs in national nutrition policy instruments and dialogues. Greater use should also facilitate increased research and investments targeting existing knowledge gaps on WEPs to ensure their ex-situ conservation. Policy recognition and support, which is generally lacking today, would thus help create longer-term economic viability and link the conservation aims with sustainable management and use.

2.5 Threats and challenges for utilizing WEPs

A mix of natural and anthropogenic processes increasingly threatens the occurrence and abundance of WEPs in forest ecosystems. Land use dynamics, especially agricultural expansion, urbanization, and development projects such as rail and road construction, have led to habitat fragmentation and ecological degradation, especially in tropical regions. Encroachment of forestlands, deforestation, timber and fuelwood harvesting, wildfires, and the associated habitat destruction also endanger the richness of WEPs in natural ecosystems (Ali-Shtayeh et al., 2008). Droughts, overgrazing, and overharvesting further diminish WEP density and diversity. Anthropogenic climate change constitutes an additional threat to WEP resources (Shirsat and Koche, 2024). The magnitude of these threats, however, varies regionally depending on local socioecological conditions. Cultural disinterest, changing lifestyles, lack of knowledge of the nutritional and therapeutic properties of WEPs, inappropriate harvest procedures, inadequate postharvest storage and handling, and low shelf-life and rapid deterioration of the produce further limit the integration of WEPs into LFS. Moreover, being associated with rural poverty and low family status, younger generations in Ethiopia consider the consumption of WEPs as “less fashionable” (Duguma, 2020). However, in Europe, North America, Australia, and New Zealand, there is a resurgence of interest in using WEPs. Top chefs cook delicious cuisines with WEPs, wild berries, and other wild ingredients such as mushrooms and fish (Luczaj et al., 2012).

Despite the growing worldwide interest in WEPs and the plethora of threats, there are very few organized efforts that support and regulate the conservation and sustainable use of WEPs (FAO, 2017). Except for some exploratory ex situ conservation strategies, no specific initiatives are in vogue to promote WEP conservation through sustainable use (FAO, 2021). Governance systems to protect local communities’ and indigenous people’s rights to sustainably manage and profit from the use of WEPs and prevent others from overusing are also lacking (Borelli et al., 2020).

2.6 Wild edible plants and the traditional knowledge systems

Although widely used and their use and management deep-rooted in local traditional knowledge systems (TKS), the majority of WEPs have never been domesticated or systematically cultivated (Carvalho and Barata, 2016). The TKS, which encompass a complex array of beliefs, traditions, perceptions and value systems, transmitted orally through generations, are therefore, crucial for the preservation, utilization, and sustainable management of WEPs (Hazarika et al., 2012). However, the verbal transmittance of TKS has significantly diminished in recent times, and much of this information now exists only in the memories of elderly people (Suwardi et al., 2025). Interestingly, Uprety et al. (2012) found that in Nepal, younger individuals (aged 12–25 years) were the knowledge holders of wild fruit plants. Conversely, the knowledge relating to wild vegetables in these Nepalese households was largely maintained by the older female members (above 35 years old). Still, general awareness and interest in WEPs remain low among younger generations in Northeast India, signifying the erosion of TKS (Khan et al., 2015). Overall, rapid urbanization, modernization and settled agriculture have led to considerable loss of indigenous knowledge, practices, and technologies, besides biological and bio-cultural diversity (Keller et al., 2005).

2.7 Conservation and sustainable use of WEPs

Given the worldwide interest in WEPs and the numerous threats these resources face, conservation and sustainable utilization should be emphasized by documenting the useful species and characterizing their chemical constituents, habitats, and potential uses (Manda et al., 2025). Domestication offers a promising strategy to integrate WEPs into developmental interventions such as agroforestry (Kumar B. M. et al., 2024). In particular, the tropical homegardens may form a unique locus for integrating many WEPs (Kumar, 2008). Nurturing the promising WEPs in managed ecosystems is a sustainable way to prevent overharvesting from wildland ecosystems (Åhlberg, 2025). Residents in the western section of the Gaoligong Mountains in Yunnan have started growing Disporopsis aspersa, a Chinese medicinal food plant, in their gardens (Chen et al., 2025). Domestication and widespread cultivation of WEPs may provide economic rewards, potentially encouraging local interest in conserving important threatened WEPs. This, however, requires standardization of agro-techniques, evolving improved cultivars, and bridging knowledge gaps in seed germination and seedling development (Hazarika and Singh, 2018). In addition, prioritization of key species for sustainable harvesting and trade, developing propagation protocols to safeguard genetic diversity, and profiling the natural population are keys to WEP conservation efforts.

To ensure conservation of WEPs and their sustainable management, an integrated conservation approach involving multiple stakeholders is required (Borelli et al., 2020). According to Shirsat and Koche (2024), such an approach should collaborate with indigenous and local communities, integrate traditional and modern scientific knowledge, and implement comprehensive conservation strategies that can safeguard the diversity of WEPs. It should consider not only the nutritional potential of WEPs but also their medicinal values and pharmacological importance. Bridging the knowledge gaps in these areas is crucial for strategic planning and sustainable management.

2.8 Ethnomedical uses of WEPs and the potential risks

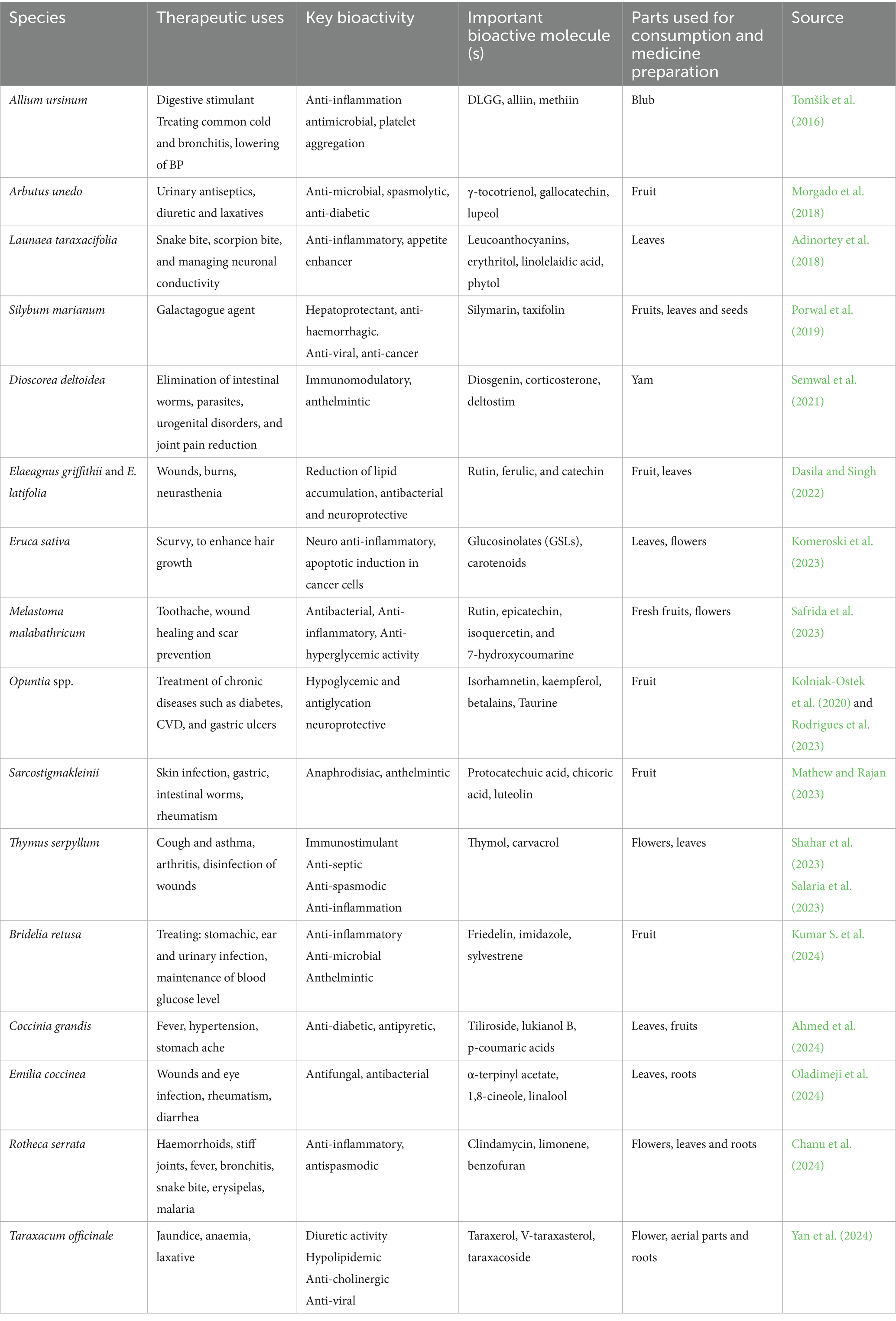

Besides their nutritional properties, WEPs are sources of numerous bioactive compounds with medicinal properties, frequently described in traditional medicine systems. The therapeutic attributes of WEPs have matured through time following the trial-and-error approach of early humans who struggled with numerous health issues. Globally, more than 20,000 plant species have been used by the traditional healers. About 64% of the global population, particularly indigenous and rural people, depend on conventional remedies for primary health care (Phondani et al., 2016). Many WEPs are traditionally used to treat various ailments, including gastrointestinal and dermatological disorders, respiratory and gynecological problems, snakebites, and so on. Although tribal communities have been ingesting WEPs since prehistoric times without understanding their ethnomedicinal value, their roles in traditional remedies underline the potential for developing functional foods and nutraceuticals to support healthcare and disease prevention (Benzie and Wachtel-Galor, 2011). In recent years, “phytoalimurgy” has helped rediscover the bioactivity of WEPs (Cammerino et al., 2024). Current research has also explored the biological activity of wild leafy vegetables, fruits, and seeds by adapting in vitro and in vivo assays. A range of bioactive compounds with anti-inflammatory, antimicrobial, antioxidant, antidiabetic effects, anti-depressant, cholesterol reducing activity, memory enhancement, immune modulators, etc., have been detected (Table 1). These compounds vary in their class of structural groups, functions, distribution, and bioavailability attributes and include short peptides, polyphenols, phytosterols, carotenoids, vitamins, short-chain fatty acids, terpenoids, and polysaccharides (Galanakis, 2017).

Table 1. Pharmacological and nutraceutical potential of selected wild edible plants and their traditional use with diverse functional values.

The antioxidant molecules widely detected in WEPs include phenolic compounds such as catechin, betaxanthins, betacyanins, quercetin pentoside, and hydroxycinnamic acids. Such molecules in Prunus nepalensis fruits regulated GSH synthase activity in mice (Chaudhuri et al., 2015). Likewise, the IJP70-1 polysaccharide from Inula japonica inhibited angiogenesis, and its water extract suppressed inflammatory cytokines and the JAK–STAT pathway in Asthma models. These results validate its use in traditional Chinese medical systems as an anti-tumor drug and for respiratory cure (Jung et al., 2025; Wang et al., 2023). Wild Himalayan strawberries, such as Fragaria nubicola, F. bucharica, and F. daltoniana, exhibited immunomodulatory and neuroprotective effects due to ellagic acid, which elevated acetylcholine levels in experimental animals (Bahukhandi et al., 2023; Sumanth et al., 2024). For treating snake bites, decoctions of WEPs, such as Euphorbia hirta, Launaea taraxacifolia, and Rotheca serrata, as well as the fruits of Alangium salvifolium and Erythrina variegata, have been applied externally. The extracts neutralized the venom and delayed cell membrane damage, necrosis, and inflammatory responses (Singh et al., 2017). The pharmaceutical and nutraceutical potential of numerous WEPs is currently being explored through a range of interdisciplinary approaches. The results imply that WEPs are future sources for sustainable pharmaceutical and nutraceutical development.

However, the ethnomedical products made from WEPs, apart from containing compounds of biological value, may also contain certain harmful compounds, such as some alkaloids and monoterpenes or bioaccumulated compounds derived from anthropogenic processes, like heavy metals or pesticides (Ali et al., 2021; Haile et al., 2018). The most frequently recognized chemical hazards in spices were mycotoxins, followed by heavy metals, including lead, cadmium and arsenic, as well as other chemical residues, according to Carpena et al. (2024). They also highlighted the presence of substances such as chlorpyrifos, ethylene oxide, pyrrolizidine alkaloids, aflatoxin B1 and ochratoxin A in six commonly consumed WEPs in Europe. Agrochemicals are extensively used in conventional crops, and nowadays, several of the WEPs are also cultivated, signifying the possibility of finding pesticide residues in ethnomedical products (Besil et al., 2017). Besides these chemical risks, microbial risks, including contamination by pathogens such as Salmonella, Bacillus cereus, Escherichia coli, Listeria monocytogenes and Clostridium perfringens, are likely. Micro- and nano-plastics absorbed by plants also may have potent toxic effects on human health (Karalija et al., 2022; Rodríguez-Pérez et al., 2023). An increase in cases of poisoning has also been reported due to plant misidentification, yet another potential risk in this regard (Cornara et al., 2018). Effective risk assessment, management and communication are essential to achieve protection for human health and safety.

2.9 Valorization and sustainable use

The effective utilization and sustainable management of WEPs are currently practiced on a limited scale only (Sékou et al., 2025). Since value addition to raw fruits is essential for establishing niche markets, developing varieties suited for products like jam, jellies, pickles, fortified cookies and other foodstuffs assumes importance. Equally significant are efforts in bioprospecting endangered and threatened plants, enhancing the production of secondary metabolites, and commercializing plant-based products, as well as formulating appropriate policies to support these initiatives (Ray et al., 2020). Contemporary research demonstrated the increasing importance of agro-extractivism and the process of valorization as key dynamics defining rural economies and natural resource governance. For example, the extraction and processing of Dioscorea alata and Hymenaea spp. and production of value-added products like cookies fortified with Acrocomia aculeata and Dipteryx alata almonds have been focused on in the Andalúcia Agrarian Settlement of Bazil (Bortolotto et al., 2017). Opuntia heliabravoana cladode mucilage as an edible biofilm demonstrated its potential both as a nutritive food component and as a biodegradable packaging material (Nájera-García et al., 2018). Small businesses and cottage industries in rural northern Portugal produced marmalades and food preserves from wild fruits (Carvalho and Morales, 2013). Due to high local demand driven by nutritional, medicinal, organoleptic, and cultural value of Celosia argentea, Cassia tora, and Clerodendrum serratum, Nirmal et al. (2019) standardized protocols for tissue-culture regeneration, bioprospecting, farming, and drying the produce. Recently, however, the focus shifted toward integrating nanoencapsulation and nanofabrication techniques to improve biological activity, palatability and nutraceutical values of Thuja occidentalis, Portulaca oleracea, and Malva sylvestris, while concurrently alleviating objectionable flavors (Ombra et al., 2023; Ali et al., 2024). Nevertheless, more research and developmental efforts to optimize these technologies and to ensure their wider adoption in functional food systems are vital.

Agritourism schemes designed to reconnect citizens with nature are expanding across Europe and increasingly feature sustainable WEP collection (Mina et al., 2023). WEPs are being accepted as distinctive gastronomic resources in contemporary culinary practices of several Mediterranean countries, as a source of seasonal foods and leafy greens. Despite declining WEP consumption and gathering in the Iberian Peninsula, certain uses persist due to cultural appreciation and recreational significance. Many outdoor programs promote the collection and consumption of WEPs for recreation and experiential learning (Stryamets et al., 2015). This trend indicates that, although certain traditional practices are being abandoned, others persist, underscoring the enduring significance of WEPs for their nutritional value, cultural ecosystem services, and non-food uses (Reyes-García et al., 2015). In industrialized states like Sweden, the concept of wilderness survival, i.e., depending on WEPs for survival, is gaining traction. It focuses on outdoor education and nature engagement for conserving cultural landscapes and recreational opportunities, besides reinforcing regional identities (Svanberg, 2012). Certain wild timber species are also exploited for their nuts and pods; for example, hazelnut (Corylus avellana) and walnut (Juglans regia) are cultivated in Europe (Carvalho and Barata, 2016), while others are maintained as naturalized or semi-domesticated.

With value addition, many WEPs may become marketable and valued for diversifying human diets. However, unregulated valorization of WEPs and commercialization may lead to the over-exploitation of these resources in the wild, erosion of genetic diversity, and habitat degradation. To mitigate such negative impacts, transforming the WEPs from open-access resources to community-governed endowments is an option. The entire value chain can be reimagined, capturing socio-cultural, health, and economic benefits of indigenous and local communities and family farmers, who are engaged in production and wild harvesting of these resources (Bacchetta et al., 2016).

3 Conclusion

Food system transformation entails promoting sustainable and local practices across food production, processing, and distribution, requiring innovation along the entire food value chain. Given the global prevalence of undernourishment and the rising environmental footprints of intensive agricultural production systems, WEPs constitute a central pillar of such transformation. Of late, there is a re-awakening of global interest in LFS. In many European countries, agritourism initiatives are increasingly becoming important. Sustainable WEP collection aimed at reconnecting citizens with nature is a central feature of such programs. Internalizing WEPs into food systems also enables tackling climate change and food insecurity challenges more effectively, as well as fostering food system diversification with less dependence on staple cereals. It may also facilitate achieving SDGs. However, incorporating WEPs into LFS and their valorization necessitates domestication of promising WEPs and evolving appropriate technology packages, which are still in their infancy in most parts of the world.

Author contributions

BK: Conceptualization, Formal analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Supervision, Visualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. GB: Investigation, Writing – original draft. SB: Visualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. SJ: Conceptualization, Resources, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declare that no financial support was received for the research and/or publication of this article.

Acknowledgments

The authors are thankful to the affiliated Universities for this collaborative work.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

The author(s) declared that they were an editorial board member of Frontiers, at the time of submission. This had no impact on the peer review process and the final decision.

Generative AI statement

The authors declare that no Gen AI was used in the creation of this manuscript.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

Adinortey, M. B., Sarfo, J. K., Kwarteng, J., Adinortey, C. A., Ekloh, W., Kuatsienu, L. E., et al. (2018). The ethnopharmacological and nutraceutical relevance of Launaea taraxacifolia (Willd.) Amin ex C. Jeffrey. Evid. Based Complement. Alternat. Med. 2018:7259146. doi: 10.1155/2018/7259146

Afshin, A., Sur, P. J., Fay, K. A., Cornaby, L., Ferrara, G., Salama, J. S., et al. (2019). Health effects of dietary risks in 195 countries, 1990–2017: a systematic analysis for the global burden of disease study 2017. Lancet 393, 1958–1972. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(19)30041-8

Åhlberg, M. (2019). Totuus syötävistä luonnonkasveista eli miksi uskallan syödä lähiluonnon kasveista kestävästi keräämääni ruokaa: OSA I: Tieteellisiä perusteita käytännönläheisesti (Finnish). Translated title of the contribution: the truth about wild edible plants - why I am not afraid of eating food that I have made about plants from the local nature that I have foraged sustainably. Helsinki: Eepinen Oy, 144.

Åhlberg, M. K. (2021). A profound explanation of why eating green (wild) edible plants promotes health and longevity. Food Front. 2, 240–267. doi: 10.1002/fft2.106

Åhlberg, M. K. (2025). Wild edible plants: ensuring sustainable food security in an era of climate change. Foods 14:1611. doi: 10.3390/foods14091611

Ahmed, R. M., Widdatallah, M. O., Alrasheid, A. A., Widatallah, H. A., and Alkhawad, A. O. (2024). Evaluation of the phytochemical composition, antioxidant properties, and in vivo antihyperglycemic effect of Coccinia grandis leaf extract in mice. Univers. J. Pharm. Res. 9, 63–68. doi: 10.22270/ujpr.v9i2.1091

Ali, A. I., Dandago, M. A., and Ali, F. I. (2024). “Food applications of Telfairia occidentalis as a functional ingredient and nanoencapsulation as a promising approach toward enhancing food fortification” in Phytochemicals in agriculture and food. eds. M. Soto-Hernández, E. Aguirre-Hernández, and M. Palma-Tenango (London: IntechOpen).

Ali, S., Ullah, M. I., Sajjad, A., Shakeel, Q., and Hussain, A. (2021). Environmental and health effects of pesticide residues. Sust. Agric. Rev. 48, 311–336. doi: 10.1007/978-3-030-54719-6_8

Ali-Shtayeh, M. S., Jamous, R. M., Al-Shafie', J. H., Elgharabah, W. A., Kherfan, F. A., Qarariah, K. H., et al. (2008). Traditional knowledge of wild edible plants used in Palestine (northern West Bank): a comparative study. J. Ethnobiol. Ethnomed. 4:13. doi: 10.1186/1746-4269-4-13

Amato-Lourenco, L. F., Ranieri, G. R., de Oliveira Souza, V. C., Junior, F. B., Saldiva, P. H. N., and Mauad, T. (2020). Edible weeds: are urban environments fit for foraging? Sci. Total Environ. 698:133967. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2019.133967

Bacchetta, L., Visioli, F., Cappelli, G., Caruso, E., Martin, G., Nemeth, E., et al. (2016). A manifesto for the valorization of wild edible plants. J. Ethnopharmacol. 191, 180–187. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2016.05.061

Bahukhandi, A., Attri, D. C., Mehra, T., and Bhatt, I. D. (2023). “Fragaria spp. (Fragaria indica, Fragaria nubicola)” in Himalayan fruits and berries: Bioactive compounds, uses and nutraceutical potential. eds. T. Belwal, I. D. Bhatt, and H. P. Devkota (London: Academic Press), 183–196. doi: 10.1016/B978-0-323-85591-4.00011-8

Benzie, I. F. F., and Wachtel-Galor, S. (2011). Herbal medicine: Biomolecular and clinical aspects. 2nd Edn. Boca Raton, FL: CRC Press/Taylor & Francis, 500.

Besil, N., Pequeño, F., Alonzo, N., Hladki, R., Cesio, M. V., and Heinzen, H. (2017). Evaluation of different QuEChERS procedures for pesticide residues determination in Calendula officinalis (L) inflorescences. J. Appl. Res. Med. Aromat. Plants 7, 143–148. doi: 10.1016/J.JARMAP.2017.09.001

Bharucha, Z., and Pretty, J. (2010). The roles and values of wild foods in agricultural systems. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. Lond. Ser. B Biol. Sci. 365, 2913–2926. doi: 10.1098/rstb.2010.0123

Borelli, T., Hunter, D., Padulosi, S., Amaya, N., Meldrum, G., de Oliveira Beltrame, D. M., et al. (2020). Local solutions for sustainable food systems: the contribution of orphan crops and wild edible species. Agronomy 10:231. doi: 10.3390/agronomy10020231

Borsari, B., and Vidrine, M. F. (2024). “Edible weeds in agricultural landscapes as a research emphasis for sustainability” in An agenda for sustainable development research, world sustainability series. eds. W. Leal Filho, A. L. Salvia, and C. R. de Portela Vasconcelos (Cham: Springer), 21–37.

Bortolotto, I. M., Hiane, P. A., Ishii, I. H., de Souza, P. R., Campos, R. P., Gomes, R. J.-B., et al. (2017). A knowledge network to promote the use and valorization of wild food plants in the Pantanal and Cerrado. Brazil. Regional Environmental Change 17, 1329–1341. doi: 10.1007/s10113-016-1088-y

Cammerino, A. R. B., Piacquadio, L., Ingaramo, M., Gioiosa, M., and Monteleone, M. (2024). Wild edible plant species in the ‘king’s coastal wetland: survey, collection. Mapping and Ecological Characterization. Horticulturae 10:632. doi: 10.3390/horticulturae10060632

Capurso, A. (2024). The Mediterranean diet: a historical perspective. Aging Clin. Exp. Res. 36:78. doi: 10.1007/s40520-023-02686-3

Carpena, M., Prieto, M. A., and Trząskowska, M. (2024). Chemical and microbial risk assessment of wild edible plants and flowers. EFSA J. 22:e221111. doi: 10.2903/j.efsa.2024.e221111

Carvalho, A. M., and Barata, A. M. (2016). “The consumption of wild edible plants” in Wild plants, mushrooms and nuts: Functional food properties and applications. eds. I. C. F. R. Ferreira, P. Morales, and L. Barros (UK: John Wiley & Sons, Ltd.), 159–198. doi: 10.1002/9781118944653.ch6

Carvalho, A. M., and Morales, R. (2013). “Persistence of wild food and wild medicinal plant knowledge in a north-eastern region of Portugal” in Ethnobotany in the new Europe: people, health and wild plant resources. eds. M. de Pardo Santayana, A. Pieroni, and R. Puri. 2nd ed (Oxford: Berghahn Books), 211–238.

Chanu, W. K., Chatterjee, A., Singh, N., Nagaraj, V. A., and Singh, C. B. (2024). Phytochemical screening, antioxidant analyses, and in vitro and in vivo antimalarial activities of herbal medicinal plant, Rotheca serrata (L.) Steane&Mabb. J. Ethnopharmacol. 321:117466. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2023.117466

Chaudhuri, D., Ghate, N. B., Panja, S., Das, A., and Mandal, N. (2015). Wild edible fruit of Prunus nepalensis Ser.(Steud): A potential source of antioxidants, ameliorates iron overload-induced hepatotoxicity and liver fibrosis in mice. PLoS One 10:e0144280. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0144280

Chen, Q., Wang, M., Hu, X., Zhang, J., Zhang, Q., Xu, C., et al. (2025). Traditional knowledge and efficacy analysis of an emerging medicinal food plant: Disporopsis aspersa. Foods 14:72. doi: 10.3390/foods14010072

Cornara, L., Smeriglio, A., Frigerio, J., Labra, M., Di Gristina, E., Denaro, M., et al. (2018). The problem of misidentification between edible and poisonous wild plants: reports from the Mediterranean area. Food Chem. Toxicol. 119, 112–121. doi: 10.1016/j.fct.2018.04.066

D’Agostino, A., Di Marco, G., Rolfo, M. F., Alessandri, L., Marvelli, S., Braglia, R., et al. (2024). Microparticles from dental calculus disclose paleoenvironmental and palaeoecological records. Ecol. Evol. 14:e11053. doi: 10.1002/ece3.11053

Dasila, K., and Singh, M. (2022). Bioactive compounds and biological activities of Elaeagnus latifolia L.: an underutilized fruit of north-east Himalaya, India. S. Afr. J. Bot. 145, 177–185. doi: 10.1016/j.sajb.2021.07.020

Duguma, H. T. (2020). Wild edible plant nutritional contribution and consumer perception in Ethiopia. Int. J. Food Sci. 2020:2958623. doi: 10.1155/2020/2958623

Fanzo, J., Haddad, L., Schneider, K. R., Béné, C., Covic, N. M., Guarin, A., et al. (2021). Viewpoint: rigorous monitoring is necessary to guide food system transformation in the countdown to the 2030 global goals. Food Policy 104:102163. doi: 10.1016/j.foodpol.2021.102163

FAO (2017). Sixteenth Regular Session of the Commission on Genetic Resources for Food and Agriculture— CGRFA-16/17/Report Rev.1. Rome, Italy: FAO.

FAO (2021). The state of food security and nutrition in the world 2021. Transforming food systems for food security, improved nutrition and affordable healthy diets for all. Rome: FAO, IFAD, UNICEF, WFP and WHO.

FAO (2024). The state of food security and nutrition in the world 2024 – Financing to end hunger, food insecurity and malnutrition in all its forms. Rome: FAO, IFAD, UNICEF, WFP and WHO.

Ferreira, F. S., Brito, S. V., de Oliveira Almeida, W., and Alves, R. R. N. (2016). Conservation of animals traded for medicinal purposes in Brazil: can products derived from plants or domestic animals replace products of wild animals? Reg. Environ. Chang. 16, 543–551. doi: 10.1007/s10113-015-0767-4

Galanakis, C. M. (2017). “Chapter 1: introduction” in Nutraceutical and functional food components: Effects of innovative processing techniques (London: Academic Press), 1–14.

Garekae, H., and Shackleton, C. M. (2020). Urban foraging of wild plants in two medium-sized south African towns: people, perceptions and practices. Urban For. Urban Green. 49:126581. doi: 10.1016/j.ufug.2020.126581

Getachew, G. A., Asfaw, Z., Singh, V., Woldu, Z., Baidu-Forson, J. J., and Bhattacharya, S. (2013). Dietary values of wild and semi-wild edible plants in southern Ethiopia. Afr. J. Food Agric. Nutr. Dev. 13, 7485–7503. doi: 10.18697/ajfand.57.11125

Grivetti, L. E., and Ogle, B. M. (2000). Value of traditional foods in meeting macro and micronutrient needs: the wild plant connection. Nutr. Res. Rev. 13, 31–46. doi: 10.1079/095442200108728990

Haile, E., Tesfau, H., and Washe, A. P. (2018). Determination of dietary toxins in selected wild edible plants of Ethiopia. Food Sci. Qual. Manag. 75, 1–9.

Hazarika, T. K., Lalramchuana,, and Nautiyal, B. P. (2012). Studies on wild edible fruits of Mizoram, India, used as ethno-medicine. Genet. Resour. Crop. Evol. 59, 1767–1776. doi: 10.1007/s10722-012-9799-5

Hazarika, T. K., and Singh, T. S. (2018). Wild edible fruits of Manipur, India: associated traditional knowledge and implications to sustainable livelihood. Genet. Resour. Crop. Evol. 65, 319–332. doi: 10.1007/s10722-017-0534-0

Heywood, V. H. (2011). Ethnopharmacology, food production, nutrition, and biodiversity conservation: towards a sustainable future for indigenous peoples. J. Ethnopharmacol. 137, 1–15. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2011.05.027

Ickowitz, A., Powell, B., Rowland, D., Jones, A., and Sunderland, T. (2019). Agricultural intensification, dietary diversity, and markets in the global food security narrative. Glob. Food Secur. 20, 9–16. doi: 10.1016/j.gfs.2018.11.002

Ickowitz, A., Powell, B., Salim, M. A., and Sunderland, T. C. H. (2014). Dietary quality and tree cover in Africa. Glob. Environ. Chang. 24, 287–294. doi: 10.1016/j.gloenvcha.2013.12.001

IFPRI (2021). Global food policy report: transforming food systems after COVID-19. Washington, DC: IFPRI.

Jung, M. A., Lee, J. Y., Kim, Y. J., Ji, K. Y., Le, M. H., Jung, D. H., et al. (2025). Inula japonica Thunb. and its active compounds ameliorate airway inflammation by suppressing JAK-STAT signaling. Biomed. Pharmacother. 183:117852. doi: 10.1016/j.biopha.2025.117852

Karalija, E., Carbó, M., Coppi, A., Colzi, I., Dainelli, M., Gašparović, M., et al. (2022). Interplay of plastic pollution with algae and plants: hidden danger or a blessing? J. Hazard. Mater. 438:129450. doi: 10.1016/J.JHAZMAT.2022.129450

Keller, G. B., Mndiga, H., and Maass, B. L. (2005). Diversity and genetic erosion of traditional vegetables in Tanzania from the farmer’s point of view. Plant Gen. Resour. 3, 400–413. doi: 10.1079/PGR200594

Khan, M. R., Kikim, A., and Yadava, P. S. (2015). Conservation of indigenous wild edible plants used by different communities of Kangchup Hills, Senapati, north East India. Int. J. Bio-resour. Stress Manag. 6, 680–689. doi: 10.5958/0976-4038.2015.00105.0

Kolniak-Ostek, J., Kita, A., Miedzianka, J., Andreu-Coll, L., Legua, P., and Hernandez, F. (2020). Characterization of bioactive compounds of Opuntia ficus-indica (L.) mill. Seeds from Spanish cultivars. Molecules 25:5734. doi: 10.3390/molecules25235734

Komeroski, M. R., Portal, K. A., Comiotto, J., Klug, T. V., Flores, S. H., and Rios, A. D. O. (2023). Nutritional quality and bioactive compounds of arugula (Eruca sativa L.) sprouts and microgreens. Internat. J. Food Sci. Technol. 58, 5089–5096. doi: 10.1111/ijfs.16607

Kumar, B. M. (2008). “Homegarden-based indigenous fruit tree production in peninsular India” in Indigenous fruit trees in the tropics: domestication, utilization, and commercialization. eds. F. K. Akinnifesi, R. R. B. Leakey, O. C. Ajayi, G. Sileshi, Z. Tchoundjeu, and P. Matakala, et al. (Wallingford, UK: CAB International Publishing), 84–99.

Kumar, S., Kumar, D., Sahu, M., Maurya, N. S., Mani, A., Govindasamy, C., et al. (2024). An in vitro and in silico antidiabetic approach of GC–MS detected friedelin of Bridelia retusa. J. King Saud Univ. Sci. 36:103411. doi: 10.1016/j.jksus.2024.103411

Kumar, B. M., Kunhamu, T. K., Bhardwaj, A., and Santhoshkumar, A. V. (2024). Subcanopy light availability, crop yields, and managerial implications: a systematic review of the shaded cropping systems in the tropics. Agrofor. Syst. 98, 2785–2810. doi: 10.1007/s10457-024-00957-0

Liu, S., Huang, X., Bin, Z., Yu, B., Lu, Z., Hu, R., et al. (2023). Wild edible plants and their cultural significance among the Zhuang ethnic group in Fangchenggang, Guangxi, China. J. Ethnobiol. Ethnomed. 19:52. doi: 10.1186/s13002-023-00623-2

Luczaj, L., Pieroni, A., Tardío, J., Pardo-de-Santayana, M., Sõukand, R., Svanberg, I., et al. (2012). Wild food plant use in 21st-century Europe: the disappearance of old traditions and the search for new cuisines involving wild edibles. Acta Soc. Bot. Pol. 81, 359–370. doi: 10.5586/asbp.2012.031

Lulekal, E., Asfaw, Z., Kelbessa, E., and Damme, P. V. (2011). Wild edible plants in Ethiopia: a review on their potential to combat food insecurity. Africa Focus 24, 71–122. doi: 10.1163/2031356X-02402006

Mahapatra, A. K., and Panda, P. C. (2012). Wild edible fruit diversity and its significance in the livelihood of indigenous tribals: evidence from eastern India. Food Secur. 4, 219–234. doi: 10.1007/s12571-012-0186-z

Mamo, D. (2025). The indigenous world 2025. 39th edition. The international work group for indigenous affairs (IWGIA). Copenhagen, Denmark: Eks-Skolens Grafisk Design &Tryk, 780.

Manda, L., Idohou, R., Agoyi, E. E., Agbahoungba, S., Salako, K. V., Agbangla, C., et al. (2025). Progress of in situ conservation and use of crop wild relatives for food security in a changing climate: a case of the underutilized Vigna Savi. Front. Sustain. 6:1453170. doi: 10.3389/frsus.2025.1453170

Mathew, S., and Rajan, R. (2023). “Medicinal properties and population studies on Sarcostigma kleinii Wight &Arn” in Bioprospecting of tropical medicinal plants. eds. K. Arunachalam, X. Yang, and S. P. Sasidharan (Cham, Switzerland: Springer Nature), 699–706.

Menalled, F., and Ebel, R. (2025). “Edible weeds as crops” in Agroecology of edible weeds and noncrop plants. eds. R. Ebel and F. Menalled (London: Academic Press), 75–102. doi: 10.1016/B978-0-443-16076-9.00006-8

Miller, R. P., Penn, J. W., and van Leeuwen, J. (2006). “Amazonian homegardens: their ethnohistory and potential contribution to agroforestry development” in Tropical Homegardens. Advances in agroforestry. eds. B. M. Kumar and P. K. R. Nair, vol. 3 (Dordrecht: Springer), 43–60. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4020-4948-4_4

Mina, G., Scariot, V., Peira, G., and Lombardi, G. (2023). Foraging practices and sustainable management of wild food resources in Europe: a systematic review. Land 12:1299. doi: 10.3390/land12071299

Morgado, S., Morgado, M., Plácido, A. I., Roque, F., and Duarte, A. P. (2018). Arbutus unedo L.: from traditional medicine to potential uses in modern pharmacotherapy. J. Ethnopharmacol. 225, 90–102. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2018.07.004

Mount, P. (2012). Growing local food: scale and local food systems governance. Agric. Hum. Values 29, 107–121. doi: 10.1007/s10460-011-9331-0

Muraleedharan, P. K., Sasidharan, N., Kumar, B. M., Sreenivasan, M. A., and Seethalakshmi, K. K. (2005). Non-timber forest products in the Western Ghats of India: floristic attributes, extraction and regeneration. J. Trop. For. Sci. 17, 243–257.

Nájera-García, A. I., López-Hernández, R. E., Lucho-Constantino, C. A., and Vázquez-Rodríguez, G. A. (2018). Towards drylands biorefineries: valorisation of forage Opuntia for the production of edible coatings. Sustainability 10:1878. doi: 10.3390/su10061878

Nesbitt, M., McBurney, R. P. H., Broin, M., and Beentje, H. J. (2010). Linking biodiversity, food and nutrition: the importance of plant identification and nomenclature. J. Food Compos. Anal. 23, 486–498. doi: 10.1016/j.jfca.2009.03.001

Nirmal, O. A., Parulekar, Y. R., Haldavnekar, P. C., Khandekar, R. G., Kulkarni, M. M., Salvi, B. R., et al. (2019). Studies on commercial cultivation of selected wild vegetables in coastal Maharashtra. Prog. Hort. 51, 166–176. doi: 10.5958/2249-5258.2019.00027.7

Oladimeji, A. O., Karigidi, K. O., Yeye, E. O., and Omoboyowa, D. A. (2024). Phytochemical composition, antioxidant and antimicrobial activities of essential oils extracted from Emilia coccinea (Sims) G. Don. Using in-vitro and in-silico approaches. Vegetos, 1–11. doi: 10.1007/s42535-024-01018-8

Ombra, M. N., Nazzaro, F., and Fratianni, F. (2023). Pasta fortification with leaves of edible wild plants to lower the P glycaemic index of handmade fresh noodles. Recent Prog. Nutr. 3, 1–21. doi: 10.21926/rpn.2302008

Phondani, P. C., Bhatt, I. D., Negi, V. S., Kothyari, B. P., Bhatt, A., and Maikhuri, R. K. (2016). Promoting medicinal plants cultivation as a tool for biodiversity conservation and livelihood enhancement in Indian Himalaya. J. Asia-Pac. Biodivers. 9, 39–46. doi: 10.1016/j.japb.2015.12.001

Pieroni, A. (2005). “Gathering food from the wild” in The cultural history of plants. eds. G. Prance and M. Nesbitt (New York: Routledge), 35–49. doi: 10.4324/9780203020906

Pieroni, A. (2021). Wild foods: a topic for food pre-history and history or a crucial component of future sustainable and just food systems? Foods 10:827. doi: 10.3390/foods10040827

Porwal, O., Ameen, M. M., Anwer, E. T., Uthirapathy, S., Ahamad, J., and Tahsin, A. (2019). Silybum marianum (Milk thistle): review on its chemistry, morphology, ethno-medical uses, phytochemistry and pharmacological activities. J. Drug Delivery Therapeutics 9, 199–206. doi: 10.22270/jddt.v9i5.3666

Rana, J. C., Pradheep, K., Chaurasia, O. P., Sood, S., Sharma, R. M., Singh, A., et al. (2012). Genetic resources of wild edible plants and their uses among tribal communities of cold arid region of India. Genet. Resour. Crop. Evol. 59, 135–149. doi: 10.1007/s10722-011-9765-7

Ray, A., Ray, R., and Sreevidya, E. A. (2020). How many wild edible plants do we eat—their diversity, use, and implications for sustainable food system: an exploratory analysis in India. Front. Sustain. Food Syst. 4:56. doi: 10.3389/fsufs.2020.00056

Reyes-García, V., Menendez-Baceta, G., Aceituno-Mata, L., Acosta-Naranjo, R., Calvet-Mir, L., Domínguez, P., et al. (2015). From famine foods to delicatessen: interpreting trends in the use of wild edible plants through cultural ecosystem services. Ecol. Econ. 120, 303–311. doi: 10.1016/j.ecolecon.2015.11.003

Rockström, J., Donges, J. F., Fetzer, I., Martin, M. A., Wang-Erlandsson, L., and Richardson, K. (2024). Planetary boundaries guide humanity’s future on earth. Nat. Rev. Earth Environ. 5, 773–788. doi: 10.1038/s43017-024-00597-z

Rodrigues, C., Paula, C. D. D., Lahbouki, S., Meddich, A., Outzourhit, A., Rashad, M., et al. (2023). Opuntia spp.: an overview of the bioactive profile and food applications of this versatile crop adapted to arid lands. Foods 12:1465. doi: 10.3390/foods12071465

Rodríguez-Pérez, C., de Sáenz Rodrigáñez, M., and Pula, H. J. (2023). Occurrence of nano/microplastics from wild and farmed edible species. Potential effects of exposure on human health. Adv. Food Nutr. Res. 103, 273–311. doi: 10.1016/BS.AFNR.2022.08.003

Rumicha, T. D., Belew, S., Hasen, G., Teka, T. A., and Forsido, S. F. (2025). Food, feed, and phytochemical uses of wild edible plants: A systematic review. Food Sci. Nutr. 13:e70454. doi: 10.1002/fsn3.70454

Safrida, S., Ulhusna, F. A., Gholib, G., Matualiah, M., Adinda, R., Putri, Y. A., et al. (2023). Phytochemical characterization and sensory evaluation of vinegar from Melastoma malabathricum L. flowers with variations in starter concentration and fermentation time. Jurnal Penelitian Pendidikan IPA 9, 706–713. doi: 10.29303/jppipa.v9i2.2940

Salaria, D., Rolta, R., Lal, U. R., Dev, K., and Kumar, V. (2023). A comprehensive review on traditional applications, phytochemistry, pharmacology, and toxicology of Thymus serpyllum. Indian J. Pharmacol. 55, 385–394. doi: 10.4103/ijp.ijp_220_22

Sékou, C. II, Émilie, K., Lonsény, T., and Michel, H. (2025). Valorization of Dialium guineense fruit seeds as a new hydrocolloid for food application. Internat. J. Food Sci. Technol. 60:vvae054. doi: 10.1093/ijfood/vvae054

Semwal, P., Painuli, S., and Cruz-Martins, N. (2021). Dioscorea deltoidea wall. Ex Griseb: a review of traditional uses, bioactive compounds and biological activities. Food Biosci. 41:100969. doi: 10.1016/j.fbio.2021.100969

Shahar, B., Indira, A., Santosh, O., Dolma, N., and Chongtham, N. (2023). Nutritional composition, antioxidant activity and characterization of bioactive compounds from Thymus serpyllum L.: an underexploited wild aromatic plant. Meas. Food 10:100092. doi: 10.1016/j.meafoo.2023.100092

Shirsat, R., and Koche, D. (2024). “Wild edible plants (WEPs): A review on their importance, possible threats, and conservation” in Contemporary research and perspectives in biological science. ed. L. Son, vol. 2 (Kolkata: Book Publisher International), 97–115.

Singh, P., Yasir, M., Hazarika, R., Sugunan, S., and Shrivastava, R. (2017). A review on venom enzymes' neutralizing ability of secondary metabolites from medicinal plants. J. Pharmacopuncture. 20, 173–178. doi: 10.3831/KPI.2017.20.020

Sreekumar, V. B., Sreejith, K. A., Hareesh, V. S., and Sanil, M. S. (2020). An overview of wild edible fruits of Western Ghats, India. Genet. Resour. Crop. Evol. 67, 1659–1693. doi: 10.1007/s10722-020-00986-5

Stryamets, N., Elbakidze, M., Ceuterick, M., Angelstam, P., and Axelsson, R. (2015). From economic survival to recreation: contemporary uses of wild food and medicine in rural Sweden, Ukraine and NW Russia. J. Ethnobiol. Ethnomed. 11:53. doi: 10.1186/s13002-015-0036-0

Sumanth, B., Uzma, F., Konappa, N., Ali, D., Alarifi, S., Chowdappa, S., et al. (2024). Isolation of antimicrobial ellagic acid from endophytic fungi and their target-specific drug design through computational docking. Biomass Convers. Biorefinery 14, 24867–24888. doi: 10.1007/s13399-024-05938-y

Suwardi, A. B., Baihaqi, B., and Harmawan, T. (2025). Diversity, utilization, and sustainable management of wild edible fruit plants in agroforestry systems: a case study in Central Kalimantan, Indonesia. Agrofor. Syst. 99:64. doi: 10.1007/s10457-025-01165-0

Svanberg, I. (2012). The use of wild plants as food in pre-industrial Sweden. Acta Soc. Bot. Pol. 81, 317–327. doi: 10.5586/asbp.2012.039

Tebkew, M., Gebremariam, Y., Mucheye, T., Alemu, A., Abich, A., and Fikir, D. (2018). Uses of wild edible plants in Quara district, Northwest Ethiopia: implications for forest management. Agric. Food Secur. 7:12. doi: 10.1186/s40066-018-0163-7

Termote, C., Raneri, J., Deptford, A., and Cogill, B. (2014). Assessing the potential of wild foods to reduce the cost of a nutritionally adequate diet: An example from eastern Baringo District, Kenya. Food Nutr. Bull. 35, 458–479. doi: 10.1177/156482651403500408

Tomšik, A., Pavlić, B., Vladić, J., Ramić, M., Brindza, J., and Vidović, S. (2016). Optimization of ultrasound-assisted extraction of bioactive compounds from wild garlic (Allium ursinum L.). Ultrason. Sonochem. 29, 502–511. doi: 10.1016/j.ultsonch.2015.11.005

UNPD – United Nations Population Division. (2024). World Population Prospects. United Nations, Department of Economics and Social Affairs, Population Division. Available online at: https://population.un.org/wpp/

Uprety, Y., Poudel, R. C., Shrestha, K. K., Rajbhandary, S., Tiwari, N. N., Shrestha, U. B., et al. (2012). Diversity of use and local knowledge of wild edible plant resources in Nepal. J. Ethnobiol. Ethnomed. 8:16. doi: 10.1186/1746-4269-8-16

Wang, X., Li, Y., Liu, W., Shen, Y., Lin, Z., Nakajima, A., et al. (2023). A polysaccharide from Inula japonica showing in vivo antitumor activity by interacting with TLR-4, PD-1, and VEGF. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 246:125555. doi: 10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2023.125555

Yan, Q., Xing, Q., Liu, Z., Zou, Y., Liu, X., and Xia, H. (2024). The phytochemical and pharmacological profile of dandelion. Biomed. Pharmacother. 179:117334. doi: 10.1016/j.biopha.2024.117334

Keywords: biodiversity conservation, ecological hotspots, ethnomedicines, food system transformation, wild foods

Citation: Kumar BM, Bhavya G, De Britto S and Jogaiah S (2025) Wild edible plants for food security, dietary diversity, and nutraceuticals: a global overview of emerging research. Front. Sustain. Food Syst. 9:1686446. doi: 10.3389/fsufs.2025.1686446

Edited by:

Raul Avila-Sosa, Benemérita Universidad Autónoma de Puebla, MexicoReviewed by:

Sudha Raj, Syracuse University, United StatesCopyright © 2025 Kumar, Bhavya, De Britto and Jogaiah. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: B. Mohan Kumar, Ym1vaGFua3VtYXJrYXVAZ21haWwuY29t; Sudisha Jogaiah, anN1ZGlzaEBjdWtlcmFsYS5hYy5pbg==

Present address B. Mohan Kumar, Pushpavihar, Nadathara, Thrissur, Kerala, India

ORCID: B. Mohan Kumar, orcid.org/0000-0001-9716-6856

Sudisha Jogaiah, orcid.org/0000-0003-2831-651X

B. Mohan Kumar

B. Mohan Kumar Gurulingaiah Bhavya

Gurulingaiah Bhavya Savitha De Britto3

Savitha De Britto3 Sudisha Jogaiah

Sudisha Jogaiah