Abstract

To address the impact of demand disruption risks on dual-channel food supply chains, this paper constructs a two-echelon supply chain Stackelberg game model comprising a single supplier and a single retailer. Treating the supply chain resilience investment level as an endogenous decision variable, it systematically analyzes its effects on system profit and channel coordination under four scenarios: decentralized decision-making, centralized decision-making, cost-sharing contract (CS), and a composite contract combining cost-sharing and revenue-sharing (CRS). The research results show that although resilience investment entails upfront costs, it effectively enhances the probability of the supply chain maintaining normal operations during disruptions, thereby significantly increasing overall profit. Among these contractual mechanisms, the CRS contract, through its dual incentive approach of “cost-sharing + revenue-sharing,” demonstrates the optimal coordination effect in promoting upstream and downstream collaborative investment and alleviating the “double marginalization” problem. Further numerical simulation analysis indicates that the resilience investment efficiency coefficient (λ) has a positive impact on profit levels and resilience investment intensity. In contrast, the impact coefficient of resilience investment on market demand (η) exhibits an inverted U-shaped relationship with profit, pricing, and investment level. This study provides a theoretical basis for food enterprises to scientifically formulate resilience investment strategies and design contractual mechanisms to achieve risk resistance and system synergy in the context of demand disruptions.

1 Introduction

Currently, global supply chains are facing escalating uncertainties. Frequent “black swan” events—such as natural disasters, geopolitical conflicts, and public health crises—have transformed supply chain disruptions from occasional risks into commonplace challenges (Amorim et al., 2023; Tiwari et al., 2024). Among these disruption risks, demand disruption stands out as particularly critical (Diaz et al., 2023). Originating from drastic fluctuations in end markets, it may manifest as a sharp decline in demand within a short period, leading to inventory accumulation and cash flow pressures (Moadab et al., 2023). Alternatively, it may trigger panic buying among consumers, causing sudden demand surges that leave enterprises struggling with insufficient production capacity and customer loss (Qiao and Zhao, 2023). Such non-linear and abrupt demand changes impose higher requirements on the responsiveness and robustness of supply chains (Sun et al., 2023).

Building a resilient supply chain with the ability to withstand shocks and recover quickly is not only the foundation for ensuring normal business operations but also a key strategy for maintaining competitiveness and achieving sustainable development in a volatile environment (Silva et al., 2021). However, despite deepening research on supply chain risk management, existing literature still has certain limitations regarding demand disruption issues (Dong et al., 2019). Most studies focus on supply-side disruptions or explore coordination mechanisms under assumptions of stable, linear, or merely stochastic demand, making it difficult to accurately reflect the suddenness, high uncertainty, and non-linear characteristics of real-world demand disruptions (Pham et al., 2023). Furthermore, although “enhancing resilience” has become a common consensus, research that systematically incorporates resilience investment as a core decision variable into the game analysis of dual-channel supply chains and explores its interaction with pricing strategies and contract design remains relatively scarce (Drozdibob et al., 2023; Gaudenzi et al., 2023). This often leaves enterprises lacking a scientific basis for weighing the costs and potential benefits of resilience investment when practically responding to demand shocks (Pertheban et al., 2023).

This study focuses on a dual-channel food supply chain and incorporates resilience investment as a key variable into a Stackelberg game model for analysis. In this model, the dominant supplier is responsible for setting both the wholesale price and the level of resilience investment, while the retailer determines the final retail price based on these decisions. To enhance the overall performance of the supply chain, we introduce a combined mechanism of cost-sharing contracts and revenue-sharing contracts, exploring how contract design can contribute to profit growth. In terms of research methodology, we adopt an integrated approach of game-theoretic analysis and numerical simulation: equilibrium outcomes under different decision-making modes are derived using backward induction, and the impact of key parameters on decisions is examined through sensitivity analysis. This combination of theoretical modeling and empirical validation not only ensures the scientific rigor of the research process but also enhances the practical relevance of the findings for real-world management.

Unlike previous studies that predominantly focused on supply disruptions or stable demand, this paper shifts the emphasis to demand-side shocks and selects the food supply chain as a typical scenario for analysis, thereby enhancing the practical relevance of the research. A detailed comparison can be found in Table 1. This work not only expands the application of supply chain resilience theory in the context of dual channels and demand disruptions but also provides valuable theoretical insights for managers in the food and related industries to build more resilient supply chain systems.

Table 1

| Research dimension | Traditional representative studies | This study |

|---|---|---|

| Core scenario | Supply disruption, stable/stochastic demand | Demand disruption risk |

| Decision variables | Pricing, production/inventory level, green investment level | Adds core variable: Resilience investment level (e) |

| Channel structure | Mostly focused on single-channel | Dual-channel supply chain |

| Coordination mechanism | Traditional contracts like revenue sharing, buyback, two-part tariff | Cost-sharing contract (CS) & Cost-sharing + Revenue-sharing composite contract (CRS) |

| Theoretical framework | Mostly static optimization or stochastic programming | Stackelberg dynamic game, supplier as leader, first decides resilience investment |

Comparison of this study with existing research on core dimensions.

2 Literature review

2.1 Demand disruption

Demand disruptions are typically triggered by changes in the natural environment, policy adjustments, or social factors, manifesting as a sudden surge or sharp decline in market demand over a short period, thereby undermining the stable operation of supply chains (Wu et al., 2023). From a supply chain network perspective, such disruptions propagate through the system by altering consumer behavior patterns, creating ripple effects on overall operations and emerging as one of the central issues in supply chain risk management (Yang and Zhao, 2011). Current academic research primarily develops along two trajectories: first, investigating how to establish appropriate product pricing and production planning under disruption conditions; second, analyzing how to optimize procurement strategies and inventory management mechanisms within such contexts (Chen et al., 2021; Khanlarzade and Yegane, 2022).

Regarding product pricing, Yan et al. (2021) explored the pricing and coordination decisions of a dual-channel supply chain under decentralized decision-making in a demand disruption context. Hosseini-Motlagh et al. (2019) investigated the optimal pricing, sustainability level, and CSR decisions of a reverse supply chain (RSC) system under demand disruption. Pi et al. (2019) studied competitive and cooperative product pricing strategies in a dual-channel supply chain consisting of one manufacturer and two retailers under demand disruptions. Rahmani and Yavari (2019) examined pricing decisions and green inputs in a green supply chain under demand disruptions. Zhai et al. (2022) analyzed pricing decisions under demand disruptions in the presence of different power structures.

In terms of purchasing and inventory decision-making for products under demand disruptions, He and Wang (2012) focused on deteriorating items and proposed corresponding production and inventory plans based on the duration and severity of the disruptions. Xu et al. (2018) analyzed the supply chain optimization problem of a dual-channel supply chain in the context of online subsidy services and demand disruptions. Pathy and Rahimian (2023) examined the pharmaceutical supply chain and explored flexible inventory strategies under demand disruptions. Additionally, Saithong and Lekhavat (2020) considered the uncertainty of disruptions and defined the relevant inventory decision variables accordingly. Schmidt and Raman (2022) highlighted that disruptions may lead to increased inventory costs, but reliable control mechanisms can mitigate the impact of disruptions on firm risk and value. Ray and Jenamani (2016) applied the newsboy model to analyze purchasing decisions made by risk-neutral and risk-averse decision-makers in the face of supply and demand uncertainty during disruptions.

2.2 Supply chain resilience

The term “resilience” originates from the Latin word meaning “to rebound,” describing a system's ability to overcome shocks by recovering to its original state (Razak et al., 2023). In the context of supply chain management, supply chain resilience refers to the capacity of a supply chain to absorb the impact of disruptive events, respond to disruptions, and quickly return to its original state or achieve an even more optimized operational state (Bahrami and Shokouhyar, 2022; Junaid et al., 2023). As such, supply chain resilience can be regarded as a dynamic capability. It encompasses the various stages from the occurrence of a risk to recovery: preparation, response, recovery, and growth (Hendry et al., 2019; Birkel et al., 2023).

The academic community generally recognizes that supply chain resilience is essentially the result of the synergistic interaction and combined effect between dynamic capabilities and risk factors within the supply chain. Based on this understanding, scholars have proposed numerous insightful perspectives from different angles (Ali et al., 2023). Before risks materialize, the key to enhancing resilience lies in strengthening the predictive capabilities of the supply chain. By improving the capture and analysis of market environments and external information, node enterprises can identify potential risk indicators earlier, issue timely warnings, and take preventive measures (Rajesh, 2016). When risks enter the occurrence phase, response speed becomes critical. At this stage, supply chain members need to dynamically adjust production plans and operational arrangements through efficient coordination and rapid decision-making to minimize the impact of external shocks on overall operations. This agile response capability represents an important dimension in measuring supply chain resilience (Kazancoglu et al., 2022). In the post-risk phase, the focus shifts to recovery and growth. Restoration capacity reflects the supply chain's ability to quickly return to its original operational level after being impacted (Ivanov et al., 2017; Al-Hakimi et al., 2021), Growth capability goes a step further—it signifies that the supply chain can not only resume normal operations but also achieve system optimization and capability upgrades after experiencing disruptions, forming a virtuous cycle of “post-traumatic growth” (Siva Kumar and Anbanandam, 2020).

Research on supply chain resilience can be roughly sorted out from two directions: one is the construction of evaluation systems, and the other is quantitative modeling analysis (Rajesh, 2017; Lu et al., 2022). In terms of evaluation, many scholars focus on identifying key factors affecting resilience and attempting to establish evaluation indicators (Lee and Rha, 2016; Chowdhury and Quaddus, 2017). Asamoah et al. (2020) proposed that social network relationships can provide the necessary resources and capabilities for building resilient supply chains. Soni et al. (2014) constructed a supply chain resilience evaluation framework based on 17 indicators, including agility, flexibility, and adaptability, and explored the impact of non-financial key performance indicators (KPIs) on supply chain resilience. Ge et al. (2020) applied the fuzzy TOPSIS method to establish a set of logistics supply chain resilience indicators, arguing that enhancing information monitoring and early warning capabilities, as well as improving planning accuracy, are effective strategies for strengthening emergency supply chain resilience. Jain et al. (2017) further proposed an evaluation model containing 13 influencing factors. These works provide practical tools for qualitatively assessing the resilience level of supply chains.

In comparison, although quantitative modeling analysis has reached a certain scale, its application in the food industry is still insufficient. In limited research, Xue and Xu (2022) discussed the impact of government subsidies, power structure, and consumer preferences on food supply chain decisions, finding that subsidy policies and retailer-led models help improve system resilience. Shi et al. (2023) used a game model to analyze the impact of retailers' trade-offs between adopting blockchain technology and their procurement strategies on resilience. However, these models mostly focus on supply-side risks, rarely treating demand disruption as the core scenario. Even fewer studies treat resilience investment itself as an enterprise's proactive decision variable—especially in dual-channel competitive environments, research linking resilience investment with pricing strategies and coordination contracts is scarce.

2.3 Dual-channel supply chain coordination

The issue of dual-channel supply chain coordination, as a key topic in operations management, primarily focuses on how to alleviate channel conflicts and the “double marginalization” effect caused by the coexistence of offline retail and online direct sales. Early research mostly assumed a stable market environment, with the main goal being to optimize system performance using traditional coordination tools. For example, Yavari et al. (2024) and other scholars explored the impact of carbon trading policies on the pricing and coordination strategies of green dual-channel supply chains. Yang et al. (2024) used Stackelberg and Nash game theory to analyze pricing behavior and profit distribution mechanisms between channels.

With the rapid development of e-commerce, subsequent research gradually introduced more complex real-world factors, such as service competition, consumer channel preferences (Yu et al., 2025). Some scholars have also begun to pay attention to uncertain environments. For example, Hu et al. (2020) studied coordination strategies for dual-channel closed-loop supply chains under the assumption of stochastic demand. However, overall, these models still default to a basically stable operating environment and lack sufficient attention to sudden and severe fluctuations that may occur on the demand side—such as panic buying or consumption slumps triggered by pandemics.

Although some scholars have attempted to incorporate disruption risks into dual-channel models in recent years, the research focus remains on supply disruption (Yu et al., 2023). Even when some studies involve demand disruption, they mostly treat it as an exogenous shock, with the research focus on post-event response strategies, such as dynamic price adjustment or inventory reallocation (Zhao et al., 2022). Research that truly treats pre-event resilience building as an endogenous decision of the enterprise and systematically examines how it interacts with dual-channel pricing and contract design is still very scarce. This makes it difficult for existing theories to effectively answer a key management question: How should enterprises enhance their risk resistance through strategic investment and ensure that this investment is effectively synergized with channel management strategies?

In summary, the three research directions of demand disruption, supply chain resilience, and dual-channel coordination, although each has accumulated rich results, have long been in a state of fragmentation: demand disruption research emphasizes post-event adjustment, dual-channel coordination is often based on stable assumptions, and resilience modeling tends toward macro assessment or supply-side risk analysis. The three have not yet been organically integrated. Based on this, this paper raises the core research questions: In the context of potential sudden demand disruptions, how should a dual-channel food supply chain scientifically decide its resilience investment level? What kind of contract design should be used to promote upstream and downstream collaboration and ultimately achieve overall system optimization? To this end, this paper attempts to integrate the three threads of “demand disruption—resilience investment—dual-channel coordination” to construct a Stackelberg game model with the supplier as the leader. This model not only considers the impact of disruption probability on pricing decisions but also treats resilience investment as an active decision variable for the supplier, and designs a composite contract (CRS) combining cost-sharing and revenue-sharing to incentivize supply chain members to invest jointly and coordinate actions. This research approach helps expand the intersection of dual-channel and resilience research in theory and provides more operable decision-making references for enterprises in practice.

3 Model description and assumptions

3.1 Problem background and food supply chain characteristics

This paper focuses on how a two-echelon dual-channel food supply chain composed of a single supplier and a single retailer makes decisions and achieves coordination when facing demand disruption risk. The so-called demand disruption risk refers to drastic fluctuations in market demand triggered by sudden external events. These fluctuations affect both online and offline channels, rather than being confined to a specific region or link. For the food industry, such risks are particularly severe. Food is perishable, highly time-sensitive, and has strict quality and safety standards. Once sales are blocked, in addition to directly causing inventory backlogs, it can also lead to serious product spoilage and value loss, having a dual negative impact on the enterprise's financial status and brand image.

To cope with these risks, members of the supply chain can choose to make resilience investments in advance. In this model, we pay special attention to a core variable—the resilience investment level (e), which, in the context of the food supply chain, manifests as a series of strategic investments aimed at enhancing system stability. Specifically, these investments mainly include three aspects: first, infrastructure resilience, such as building a multi-level temperature-controlled cold chain logistics network and modern warehousing facilities; second, information and coordination resilience, such as adopting blockchain technology to improve supply chain transparency and response speed; and finally, operational model resilience, such as establishing flexible procurement mechanisms and backup logistics solutions.

The characteristic of these resilience investments is that they are made ex-ante, and once incurred, the costs are difficult to recover. However, their main return lies in significantly enhancing the supply chain's ability to maintain normal operation when facing disruptions, thereby effectively reducing the risks of food waste, revenue decline, and reputation damage caused by disruptions. Therefore, incorporating resilience investment as an endogenous decision variable into the game analysis framework of the food supply chain has not only important theoretical significance but also provides practical guiding value for enhancing the industry's risk resistance.

3.2 Research model and assumptions

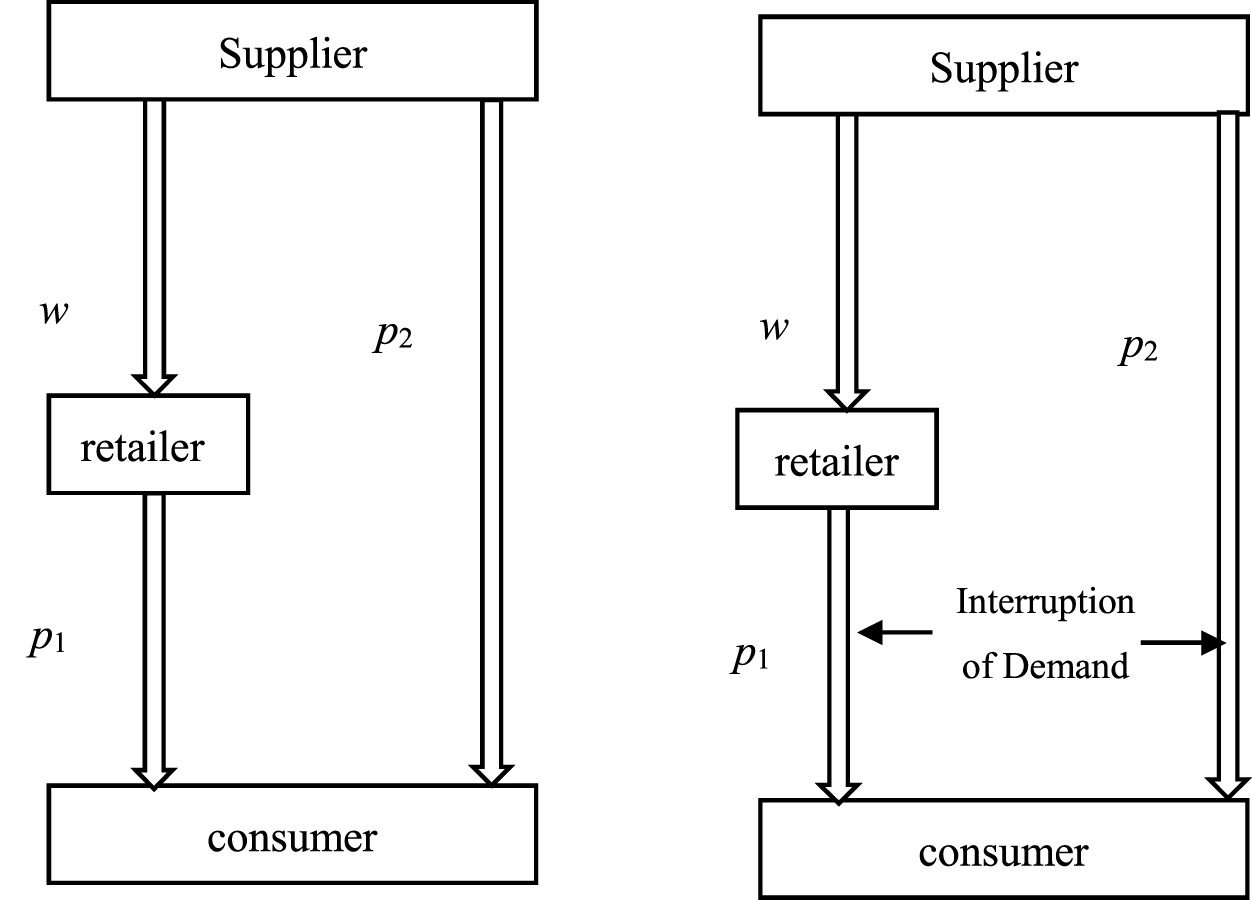

This is a dual-channel supply chain. It consists of a food supplier and a retailer. The supplier can sell products through the offline retail channel. In this case, the supplier sells to the retailer first. Then, the retailer sells the products to customers. Alternatively, the supplier can also sell directly to customers. This is done through the online direct sales channel. As shown in Figure 1. Therefore, the food supplier must decide not only the wholesale price w for products supplied to the food retailer via the offline retail channel but also the sales price p2 for products sold directly to customers via the online direct sales channel. Facing market demand, the retailer only needs to decide the sales price p1 for products sold to customers. The operational process of the food supply chain system examined in this study unfolds as follows: First, the food supplier determines the investment in supply chain resilience. Next, the supplier sets the online direct sales price p2 and the offline wholesale price w. Subsequently, the retailer, taking into account the prices established by the supplier and the online pricing, formulates the offline retail price p1. Finally, both the supplier and the retailer sell the products to consumers and generate sales revenue. The symbols and related definitions used in this paper are presented in Table 2.

Figure 1

Dual-channel supply chain demand disruption model.

Table 2

| Symbol | Definition |

|---|---|

| j | Channel index, j = 1, 2 |

| p j | The sales price of channel j, j = 1, 2 |

| e | Supply chain resilience investment level |

| w | Wholesale price per unit of product |

| α | Offline Channel Demand |

| d 1 | Offline channel demand function |

| d 2 | Online channel demand function |

| ψ | Revenue sharing coefficient ratio |

| φ | Supply chain resilience cost sharing ratio |

| τ | Probability of supply chain normal operation |

| τ0 | Initial resilience level of the supply chain |

| λ | Resilience investment efficiency coefficient (improvement effect per unit investment on resilience level) |

| η | Sensitivity coefficient of supply chain resilience investment on market demand |

| πsc | Profitability of the entire supply chain |

| πm | Supplier profits |

| πr | Retailers' profits |

Symbols and their meanings.

Hypothesis 1: All participants in the supply chain are completely rational economic agents, pursuing their own profit maximization, and information is symmetric within the supply chain system.

Hypothesis 2: Considering the characteristics of this research, total demand is assumed to be 1, and offline demand is α. The demand function is a function of channel preference, market size, retail price, and supply chain resilience investment level. Therefore, the demand function for the offline retail channel is: d1(p1, e) = α−p1+ηe, and the demand function for the online direct sales channel is: d2(p2, e) = 1−α−p2+ηe.

Hypothesis 3: The resilience investment cost function is a convex function, indicating that the marginal cost increases with the investment level: .

Hypothesis 4: The Supplier and the retailer follow the Stackelberg game, with the manufacturer being in the dominant position in the system.

Hypothesis 5: Assume the initial resilience level of the food supply chain is τ0. This represents the probability that the food supply chain maintains normal operation without resilience investment. Through resilience investment e, the supply chain resilience level is improved. The overall resilience level is defined as: τ = τ0+λe, where τ represents the probability of the supply chain operating normally, and the disruption probability is 1−τ. When a disruption occurs, the actual sales volume of both channels is 0.

4 Model solution and analysis

4.1 Decentralized decision-making model (D model)

Under a decentralized decision-making model, both the food supplier and the retailer operate as independent entities, each aiming to maximize their own profits. This setup creates a classic two-stage game process: first, the supplier, as the market leader, determines the supply chain resilience investment level e, followed by setting the wholesale price w and the online direct sales price p2. Then, the retailer observes the supplier's decisions and subsequently sets the retail price p1 for their offline stores. In this way, to analyze how resilience investment affects the profitability of each party, we need to establish separate profit functions for the supplier and the retaile:

In Equation 1, τ0+λe represents the probability of the supply chain operating normally. w(α − p1 + ηe) denotes the revenue obtained by the supplier from selling products to the retailer through the offline channel. p2(1 − α − p2 + + ηe) represents the revenue obtained by the supplier from selling products directly to consumers through the online channel. indicates the supplier's investment in supply chain resilience. In Equation 2, (p1 − w)(α − p1 + ηe) represents the revenue obtained by the retailer from selling products to consumers through the offline channel.

The backward induction method can be used to find the optimal solution. First, consider the second stage, where the food retailer sets the retail channel sales price p1 to maximize its own profit. Since , is concave in p1. Taking the first derivative of respect to p1 and setting it equal to 0, yields the retailer's optimal response function: . Substituting p1into the supplier's profit function, and taking the second derivatives of the supplier's profit function with respect to e, w, p2, we get , , . Since the food supplier simultaneously determines the wholesale price w and the retail price p2 for the online direct sales channel, the Hessian matrix can be obtained as follows:

Since |H1| = −λe−τ0 < 0|, it follows that the first leading principal minor is less than 0 and the second leading principal minor is greater than 0. Therefore, the second-order Hessian matrix is positive definite. Additionally, the following condition must be satisfied:

At this point, the system of equations has a solution for e, w, and p2.

Substitute the solutions of and into the profit function of the food supplier, and then take the derivative of the food supplier's profit function with respect to e.

. Based on the above equation, the equilibrium solution of the supply chain under the decentralized model is obtained as follows:

Substituting the above equilibrium solutions into the expression for p1, we obtain:

4.2 Centralized decision-making model (C model)

Under a centralized decision-making model, food suppliers and retailers are regarded as a unified entity, working together to achieve maximum total profit for the entire supply chain. Under this framework, the independent profit functions of supply chain members are integrated to construct a unified system total profit function. The decision process is usually that the food supplier and food retailer first decide the supply chain resilience investment e. Then they simultaneously decide the online retail price p1 and the offline retail price p2. Finally, the backward induction method is applied to identify the solution that optimizes the overall profit. At this point, the total profit function of the supply chain can be expressed as:

In Equation 3, τ0+λe represents the probability of the supply chain operating normally. p1(α−p1+ηe) denotes the revenue obtained by the supply chain from selling products to consumers through the offline channel. p2(1−α−p2++ηe) represents the revenue obtained by the supply chain from selling products to consumers through the online channel. indicates the overall investment in supply chain resilience made by the supply chain.

The optimal solution is obtained using backward induction. First, consider the second stage, where the food supplier and the food retailer set the retail channel price p1 and the online retail price p2 to maximize their respective profits. .

Since the food supplier simultaneously determines the offline product retail price p1 and the online direct sales channel product retail price p2, the Hessian matrix can be derived as follows:

Since |H1| = −2λe−2τ0 < 0 and . the first leading principal minor is less than 0, and the second leading principal minor is greater than 0. Therefore, the second-order Hessian matrix is positive definite. Additionally, when the following condition is satisfied:

the system of equations has a solution for e, p1, and p2.

According to the equations above, the equilibrium solution of the supply chain under the centralized model is obtained as follows:

Conclusion 1 When , the resilience investment under centralized decision-making increases as the supply chain resilience investment efficiency coefficient increases.

Proof: Take the derivative of the optimal supply chain resilience investment level with respect to the supply chain resilience investment efficiency coefficient λ.

When ,

Conclusion 2 The resilience investment under centralized decision-making increases as the initial resilience level τ0 increases.

Proof: Since

therefore, the resilience investment under centralized decision-making increases as the initial resilience level τ0 increases.

Conclusion 3 When comparing centralized and decentralized decision-making, the relative magnitude of profits under centralized decision-making vs. the decentralized decision model depends on the parameter values.

Proof: Let . The following expression can be derived:

Therefore, the relative magnitude of profits under centralized decision-making vs. the decentralized decision model depends on the values of the other parameters.

To deeply explore the specific performance of the profit relationship under centralized and decentralized decision-making and seek an effective path to achieve supply chain coordination, the subsequent numerical simulation part of this paper will focus on comparing and analyzing the profit performance under two coordination mechanisms: the cost-sharing contract (CS) and the cost-sharing plus revenue-sharing contract (CRS). By setting reasonable parameter ranges, the impact of different contract modes on supplier profit, retailer profit, and total system profit will be simulated and systematically compared with the profit levels under the decentralized decision mode. This aims to intuitively reveal the effectiveness of the two contracts in incentivizing member collaborative investment and alleviating the “double marginalization” effect, thereby providing clear decision-making basis for supply chain managers to choose the optimal coordination strategy under different scenarios.

4.3 Cost-sharing game model (CS model)

To better coordinate the supply chain during demand disruptions, we introduce the Cost-Sharing Contract (CS) as a collaborative solution. The core arrangement involves the retailer sharing a portion φ of the supplier's resilience investment costs, thereby incentivizing the supplier to increase their investment level. The rationale behind this design lies in the fact that resilience investments not only ensure stable production for the supplier but also help maintain product freshness and supply stability, ultimately bringing more customers and sales to the retail channel and benefiting the retailer indirectly. However, under decentralized decision-making, the supplier bears the full cost alone without capturing all the benefits, leading to insufficient investment motivation. By sharing the costs, the financial burden on the supplier is directly reduced, making them more willing to elevate resilience investments closer to the system-optimal level. This approach ultimately enhances the overall performance of the supply chain. The profit functions for each party can be expressed as:

In Equation 4, τ0+λe represents the probability of the supply chain operating normally. w(α−p1+ηe) denotes the revenue obtained by the supplier from selling products to the retailer through the offline channel. p2(1−α−p2++ηe) represents the revenue obtained by the supplier from selling products directly to consumers through the online channel. indicates the portion of the supply chain resilience investment borne by the supplier, accounting for 1−φ of the total cost. In Equation 5, (p1−w)(α−p1+ηe) represents the revenue obtained by the retailer from selling products to consumers through the offline channel. indicates the portion of the supply chain resilience investment borne by the retailer, accounting for φ of the total cost.

The optimal solution can be obtained using backward induction. First, consider the second stage, where the food retailer sets the retail channel price p1 based on observed outcomes to maximize its own profit. Since it follows that is a concave function of p1. By taking the first-order derivative of p1 and setting it to zero, the profit function for the traditional retail channel p1 can be derived: which implies . Substituting p1 into the food supplier's profit function and taking the second-order derivatives of the food supplier's profit function with respect to e, w, and p2, we obtain: , . Since the food supplier simultaneously determines the wholesale price w and the retail price p2 for the online direct sales channel, the Hessian matrix can be derived as follows:

Since |H1| = −λe−τ0 < 0, . The first leading principal minor is less than 0 and the second leading principal minor is greater than 0. Therefore, the second-order Hessian matrix is positive definite. Additionally, when the following condition is satisfied:

the system of equations has a solution for e, w, and p2.

Based on the above equations, the equilibrium solution of the supply chain under the cost-sharing model is obtained as follows:

Substituting the above equilibrium solutions into the expression for p1, we obtain:

This contract, by setting the baseline of “profit not less than under decentralized decision,” ensures the willingness of the supplier and retailer to cooperate, thus laying the foundation for Pareto improvement. On this basis, the two parties can flexibly adjust the core mechanism of the cost-sharing proportion according to the actual situation to dynamically optimize profit distribution and jointly pursue overall profit maximization.

4.4 Cost-sharing + revenue-sharing game model (CRS model)

This section further introduces the Cost-and-Revenue-Sharing contract (CRS) on the basis of the cost-sharing contract (CS) to build a more comprehensive collaborative mechanism. This composite contract contains two core parameters: the proportion φ of resilience investment cost borne by the retailer, and the proportion ψ of the retailer's channel revenue shared with the supplier. Its design logic is that although the single CS contract can incentivize the supplier to increase resilience investment, the retailer only bears the cost but fails to fully share the benefits of demand growth brought by enhanced resilience. The CRS contract compensates the retailer for its cost sharing by allowing the supplier to share part of the retailer's revenue, forming a closed loop of “risk sharing and benefit sharing”: the supplier is more willing to conduct high-level resilience investment due to obtaining additional revenue, while the retailer's increased sales revenue from improved supply chain stability and demand expansion is sufficient to cover its cost and revenue sharing expenditures. This dual incentive aims to simultaneously optimize the investment level and profit distribution, thus theoretically able to more effectively approach the overall optimal performance of the centralized decision supply chain. The profit functions of the supply chain entities are respectively:

In Equation 6, τ0+λe represents the probability of normal supply chain operation. w(α−p1+ηe) denotes the revenue obtained by the supplier from selling products to the retailer through the offline channel. ψp1(α−p1+ηe) indicates that the supplier receives ψ proportion of the retailer's sales revenue. p2(1−α−p2++ηe) represents the revenue obtained by the supplier from selling products directly to consumers through the online channel. indicates that the supplier bears 1−φ proportion of the supply chain resilience investment. In Equation 7, [(1−ψ)p1−w)](α−p1+ηe)represents the total revenue retained by the retailer after sharing ψ proportion of sales revenue with the supplier. indicates that the retailer bears φ proportion of the supply chain resilience investment.

The optimal solution can be obtained using backward induction. First, consider the second stage, where the food retailer sets the retail channel price p1 based on observed outcomes to maximize its own profit. Since . it follows that is a concave function of p1. By taking the first-order derivative of p1 and setting it to zero, the profit function for the traditional retail channel p1 can be derived: . which implies. Substituting p1 into the food supplier's profit function and taking the second-order derivatives of the food supplier's profit function with respect to e, w, and p2, we obtain: , . Since the food supplier simultaneously determines the wholesale price w and the retail price p2 for the online direct sales channel, the Hessian matrix can be derived as follows:

Since , . The first leading principal minor is less than 0 and the second leading principal minor is greater than 0. Therefore, the second-order Hessian matrix is positive definite. Additionally, when the following condition is satisfied:

the system of equations has a solution for e, w, and p2.

Based on the above equations, the equilibrium solution of the supply chain under the cost-sharing model is obtained as follows:

Substituting the above equilibrium solutions into the expression for p1, we obtain:

Under this contract framework, Pareto improvement of the supply chain can be achieved, provided that the profits of all parties are guaranteed to be no less than their levels under independent decision-making. The parties can efficiently negotiate around the core coordination parameters of cost-sharing and revenue-sharing, completing dynamic decision-making by adjusting these proportions, and ultimately achieving the goal of system profit maximization.

5 Numerical analysis

5.1 Impact of contract coordination on equilibrium profit

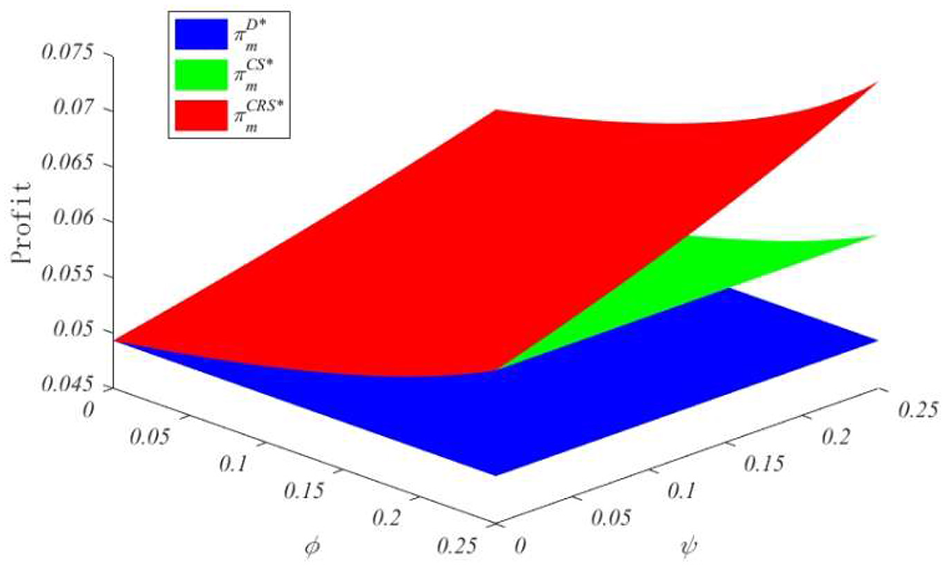

To clearly demonstrate the practical effectiveness of different coordination contracts in addressing demand disruptions, we employ MATLAB for numerical simulation analysis. By establishing a set of benchmark parameters, this study examines the dynamic changes in supply chain member profits and total system profits under three scenarios: decentralized decision-making, cost-sharing contracts, and the combined model of cost-sharing with revenue-sharing contracts. The specific parameter configuration is as follows: the initial market share of the offline channel is set at α = 0.8. This value reflects the continued dominance of traditional retail channels in the current landscape and aligns with the operational reality of most food supply chains. the initial resilience level of the supply chain τ0 = 0.4, indicating that the system has a medium to low risk resistance ability; the resilience investment efficiency coefficient λ = 0.8, reflecting that the effect of per unit investment on improving operational stability is relatively obvious; the demand impact coefficient η = 0.5, indicating that the stimulating effect of resilience investment on market demand is at a medium level. As key variables of the contracts, the cost-sharing proportion ϕ and the revenue-sharing proportion ψ are both set in the range of [0, 0.25]. This range reasonably reflects the degree of interest concession that enterprises may accept in actual cooperation, which will not excessively sacrifice their own interests but can also provide sufficient incentives for cooperation. By adjusting these two parameters within this interval, we can systematically observe how contract design affects the profit changes of all parties and identify which parameter combinations can effectively achieve Pareto improvement. The focus of the simulation is to reveal the actual performance of CS and CRS contracts in alleviating “double marginalization,” incentivizing resilience investment, and optimizing profit distribution. Basic parameter settings are as follows: α = 0.8,τ0 = 0.4,λ = 0.8,η = 0.5, φ∈[0.0.25],ψ∈[0.0.25].

Figure 2 compares the profits obtained by the food supplier under three scenarios: decentralized decision (D), cost-sharing contract (CS), and cost-sharing plus revenue-sharing contract (CRS). The simulation results show that when the cost-sharing proportion and revenue-sharing proportion are both low, the supplier's profit under decentralized decision is the lowest. This is mainly because the lack of coordination leads to the “double marginalization” problem, damaging the efficiency of the entire supply chain. After introducing the cost-sharing contract, the supplier's profit increases significantly. The reason is that the retailer begins to share part of the cost of resilience investment—such as cold chain equipment or preservation technology expenses—thus reducing the pressure on the supplier to bear the risk alone. When the revenue-sharing mechanism is further added, forming the CRS contract, the supplier's profit reaches the highest level among the three modes. This indicates that by simultaneously adjusting cost sharing and revenue distribution, bilateral cooperation can be more effectively incentivized, enhancing the overall coordination effect. Furthermore, as the cost-sharing proportion and revenue-sharing proportion increase, the supplier's profit continues to grow, showing a stronger contract incentive effect.

Figure 2

Impact of different contract modes on supplier profit.

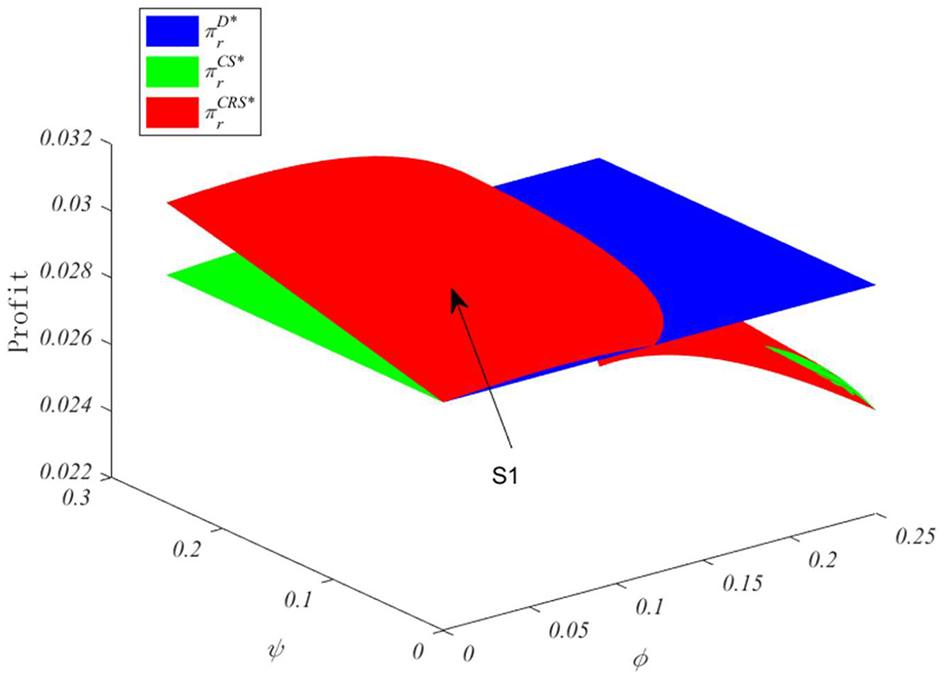

Figure 3 shows the changes in retailer profit under different contracts. Under both CS and CRS contracts, the retailer's profit first increases and then decreases with the increase of the cost-sharing proportion ϕ, showing a typical inverted U-shaped relationship. When the revenue-sharing proportion ψ is small, the retailer's profit under the CRS mode increases with the increase of this proportion. In the parameter region S1, the CRS contract can bring higher profit to the retailer than CS and decentralized decision. However, if the cost-sharing proportion and revenue-sharing proportion continue to increase, the retailer's profit will instead fall below the level under decentralized decision. This indicates that in the food supply chain, excessively requiring the retailer to bear costs or transfer revenue may be counterproductive, inhibiting its enthusiasm to participate in cooperation.

Figure 3

Impact of different contract modes on retailer profit.

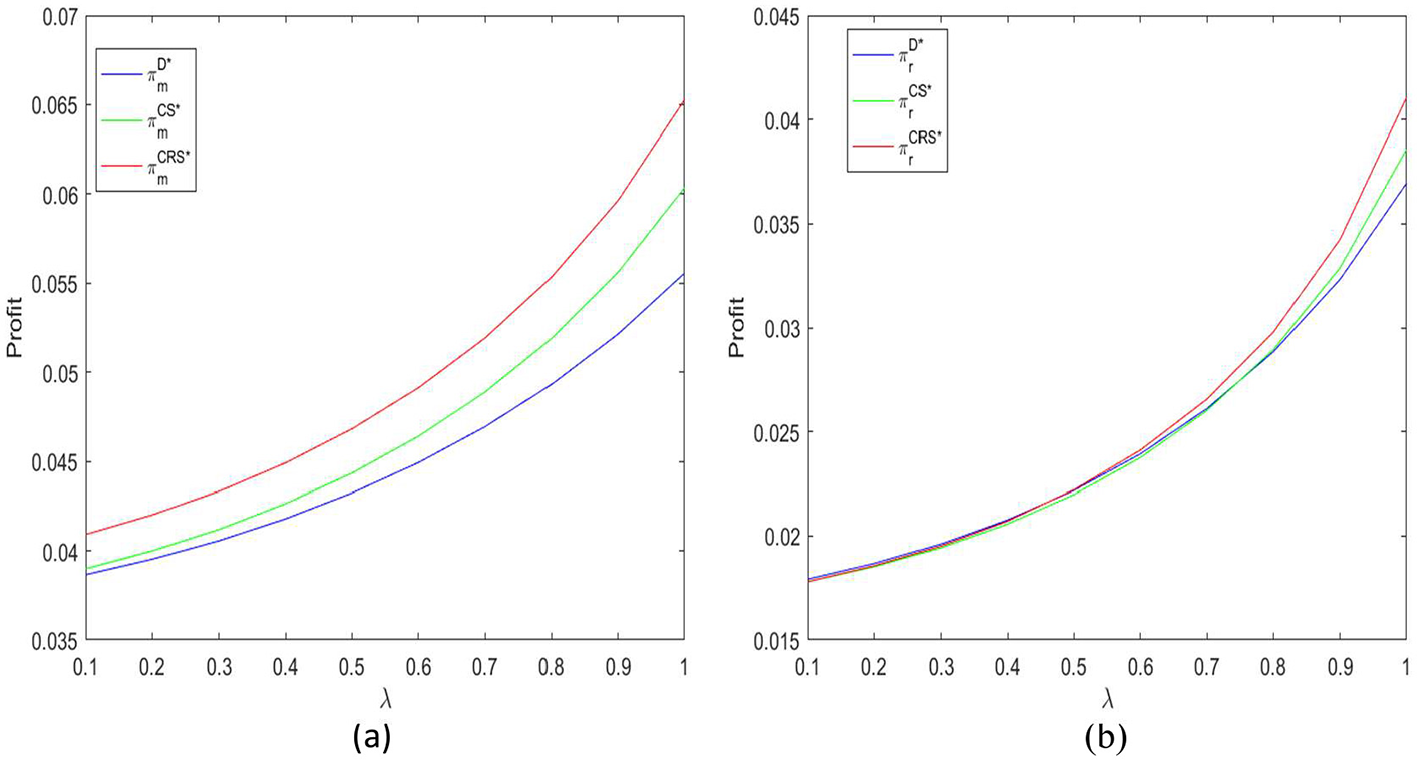

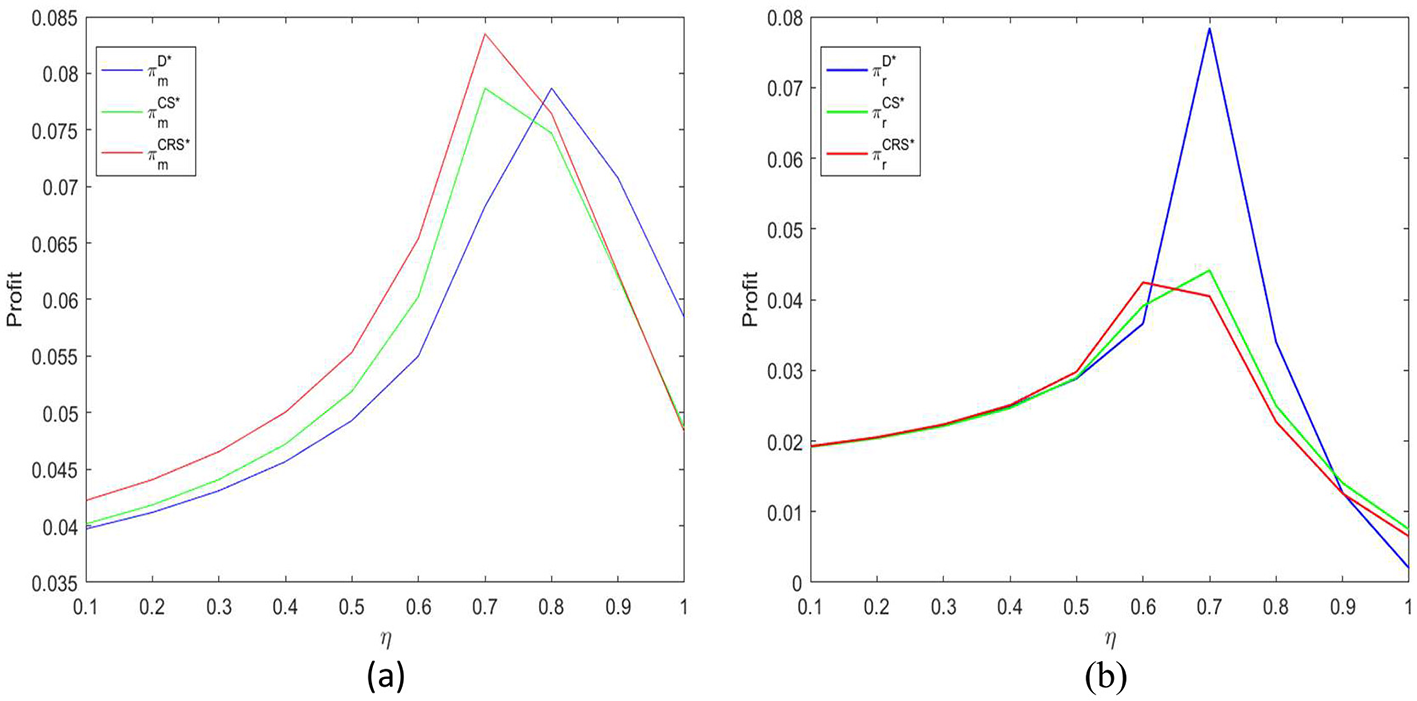

5.2 Impact of parameters λ and η on equilibrium profit

To more clearly understand the driving factors behind supply chain resilience, this section focuses on analyzing the impact of the resilience investment efficiency coefficient λ and the demand impact coefficient η on the profits of various parties in the supply chain. Based on the previous contract coordination analysis, we set the cost-sharing proportion and revenue-sharing proportion to ϕ = 0.2, ψ = 0.1, aiming to create a relatively stable contract environment to separately observe the effects of λ and η. Through numerical simulation, we can see under what levels of investment efficiency and market demand responsiveness the supplier and retailer can truly benefit from resilience investment, and how the profit performance under different decision modes changes.

Figure 4a shows that the resilience investment efficiency coefficient λ has a clear positive effect on the food supplier's profit. As λ increases, the food supplier's profit under all three decision modes continues to rise. The reason is not difficult to understand: higher investment efficiency means the same cost can bring stronger risk response capability and more stable market demand, naturally leading to higher expected revenue. It is particularly worth noting that under the CRS contract, profit grows the fastest. This indicates that when the resilience investment efficiency is high, the composite contract combining cost-sharing and revenue-sharing allows the food supplier to benefit the most from resilience construction.

Figure 4

(a, b) Impact of resilience investment efficiency coefficient λ on supply chain profit.

Figure 4b shows the impact of λ on the food retailer's profit. Overall, the retailer's profit also increases with the increase of λ, but the performance under different modes has obvious differences. Under decentralized decision-making, profit growth is relatively slow, mainly because the retailer cannot obtain all the benefits brought by resilience investment; some of these benefits “spill over” to the supplier. Under the CS and CRS contracts, especially the CRS mode, the retailer's profit improvement is more obvious. This indicates that through reasonable contract arrangements, the retailer is more motivated to participate in resilience investment and can more fully share the market benefits brought by the improvement of supply chain stability.

Figure 5a illustrates the relationship between the degree of impact of resilience investment on market demand (denoted by η) and the profit of food suppliers. Simulation results reveal that supplier profit does not consistently increase with higher values of η; instead, it follows an inverted U-shaped pattern, initially rising and then declining. Specifically, when η is relatively small, the supplier profit under the CRS contract remains higher than under the CS contract and decentralized decision-making, indicating that contractual coordination remains effective at this stage. However, as η continues to increase, signifying high market sensitivity to resilience investment and strong demand response, supplier profit under decentralized decision-making becomes the highest. This may be because, in situations of highly sensitive demand, unified coordination restricts the flexibility of parties to adapt to market changes, thereby diminishing the effectiveness of the contractual mechanism.

Figure 5

(a, b) Impact of the effect coefficient η of resilience investment on market demand on supply chain profit.

Figure 5b focuses on the impact of η on retailer profit. As a channel directly facing consumers, the retailer is more sensitive to changes in market demand, and its profit also shows an inverted U-shaped trend with η. When η is low, although resilience investment cannot greatly boost sales, it can enhance consumer trust in food safety and brands, thereby driving offline sales, from which the retailer benefits. Under the CRS contract, the retailer can not only enjoy this part of demand growth but also share the additional revenue obtained by the supplier in the online channel through the revenue-sharing mechanism, so the overall profit is the highest.

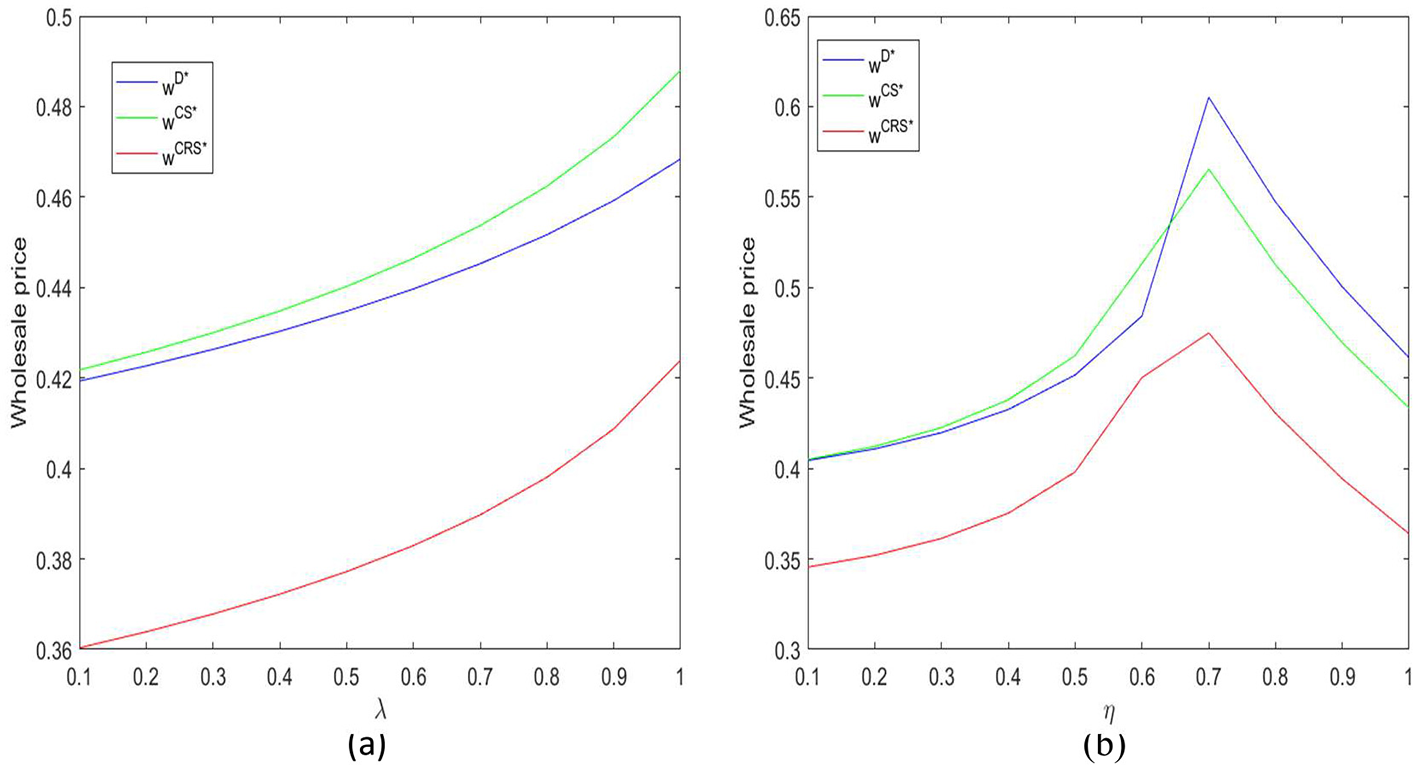

5.3 Impact of parameters λ and η on optimal decisions

Figure 6a shows that as the resilience investment efficiency coefficient λ increases, the supplier gradually increases the wholesale price w under all three decision modes. The reason is simple: the higher λ is, the more obvious the return brought by resilience investment, and the supplier will increase prices to recover part of the cost. However, under the CRS contract (cost-sharing + revenue-sharing), although the wholesale price is also rising, the increase is the most moderate, and the overall price level is the lowest among the three modes. This indicates that the CRS contract alleviates the supplier's cost transfer pressure to a certain extent, helps maintain more reasonable pricing.

Figure 6

(a, b) Effects of parameters λ and η on wholesale price.

Figure 6b illustrates the relationship between the demand influence coefficient η and the wholesale price. The wholesale price does not consistently increase with η but rather shows an inverted U-shaped pattern, rising initially before declining. When η is at low to moderate levels, resilience investment begins to stimulate market demand, prompting suppliers to moderately increase the wholesale price. However, when η becomes excessively high, the market becomes highly sensitive to resilience investment and demand approaches saturation. Further price increases at this stage could dampen retailers' ordering enthusiasm. Thus, suppliers tend to stabilize or even reduce prices under such conditions.

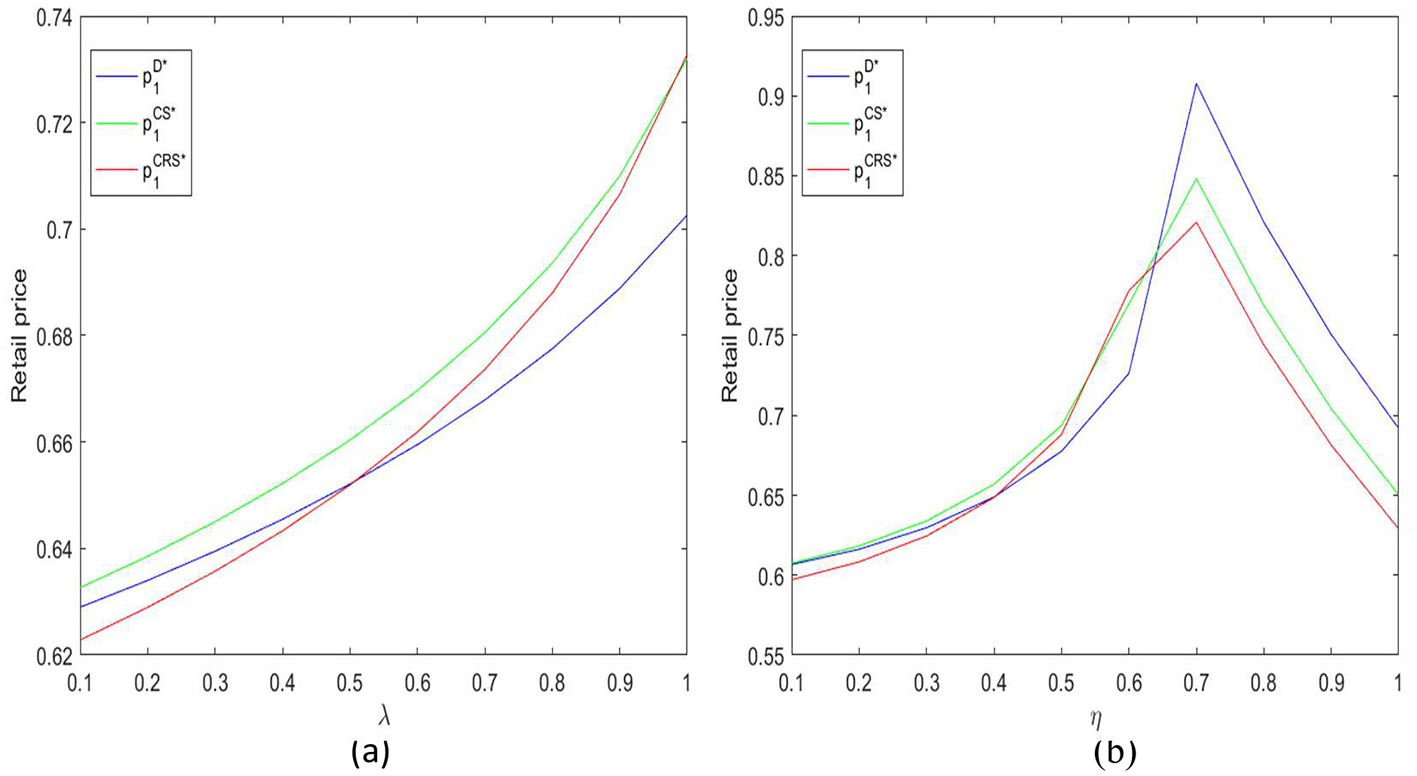

Figure 7a shows that as the resilience investment efficiency coefficient λ increases, the retailer also gradually increases the offline retail price p1. There are two reasons behind this: on the one hand, the supplier's wholesale price has increased, and cost pressure will naturally be partially transmitted to the retail end; on the other hand, the overall supply chain becomes more reliable, and consumers' trust and recognition of the product also increase, giving the retailer room to raise prices. When using coordination contracts, the adjustment of retail prices appears more stable and rhythmic, indicating closer coordination between upstream and downstream.

Figure 7

(a, b) Effects of parameters λ and η on offline retail price.

Figure 7b examines the effect of the demand impact coefficient η on the offline retail price p1. The result finds that this effect is not linear but phased: when η is small, the retail price rises with η. This is because at this time, resilience investment mainly enhances product value by improving brand image and enhancing consumer confidence, and it is reasonable for retailers to slightly increase prices accordingly. But when η continues to increase, meaning market demand is highly sensitive to resilience investment, raising prices further will reduce consumer demand. At this time, the impact of η on retail price turns negative, and retailers will actively control prices.

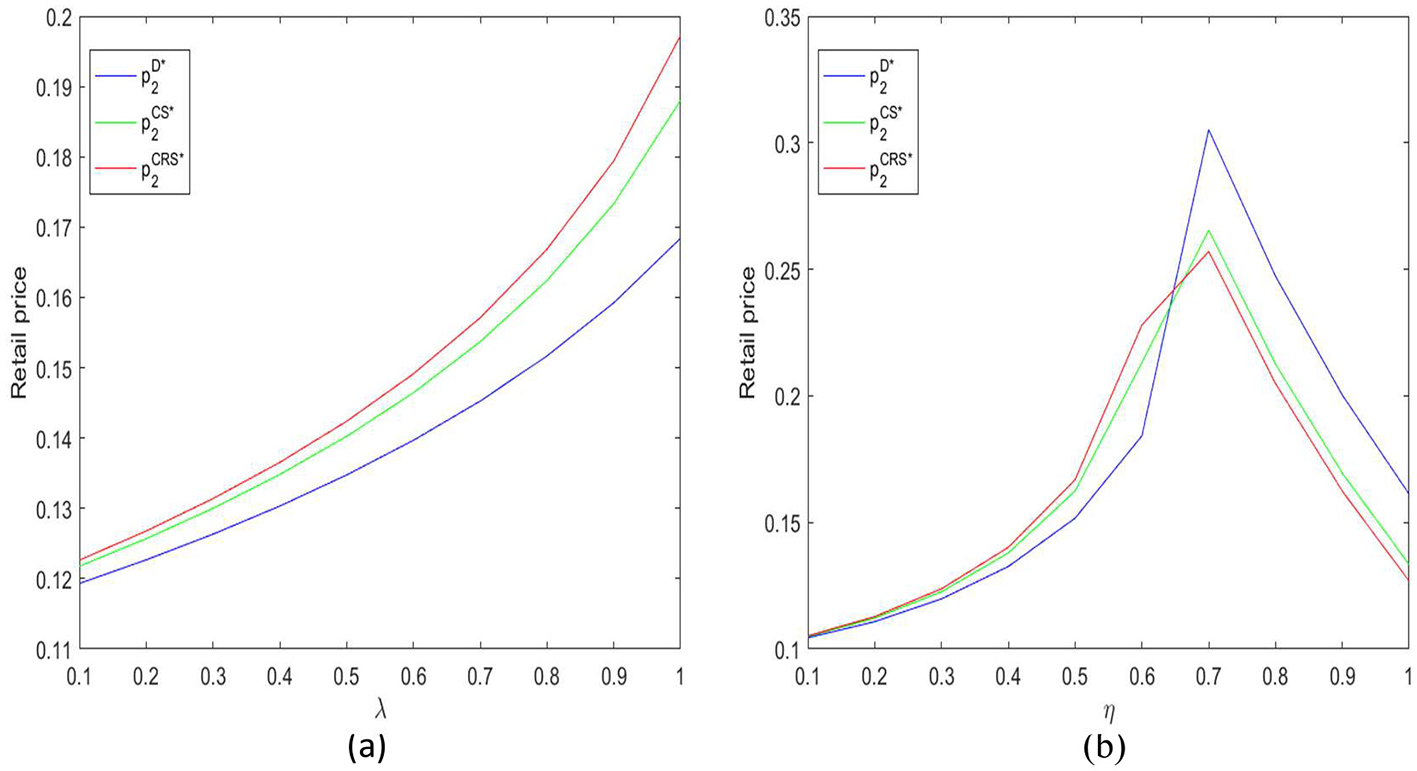

Figure 8a reveals the decision rule of the food supplier's online direct sales price p2 changing with the resilience investment efficiency coefficient λ. Similar to the offline channel, the online price also shows an upward trend with the increase of λ. As the Stackelberg leader in the supply chain, the food supplier tends to simultaneously implement price increase strategies in both wholesale and direct sales channels against the background of improved resilience efficiency, to systematically optimize its overall profit structure. It is worth noting that under the CRS coordination contract, the online direct sales price reaches the highest level among the three modes.

Figure 8

(a, b) Effects of parameters λ and η on online retail price.

Figure 8b shows the non-linear characteristics of the online retail price p2 changing with the demand impact coefficient η, showing an inverted U-shaped trajectory overall. Specifically, when η is in the low to medium range, the pulling effect of resilience investment on market demand is significant, and the supplier significantly increases the online direct sales price to obtain marginal revenue. The internal logic is that demand expansion reduces price elasticity, making the marginal revenue brought by price increases exceed the potential sales loss. However, when η further increases into the high-value range, the price level under the CRS contract turns lower than the decentralized decision mode. This is because under this contract, the food supplier needs to share part of the online revenue with the food retailer, reflecting the regulatory effect of the contract structure on pricing decisions.

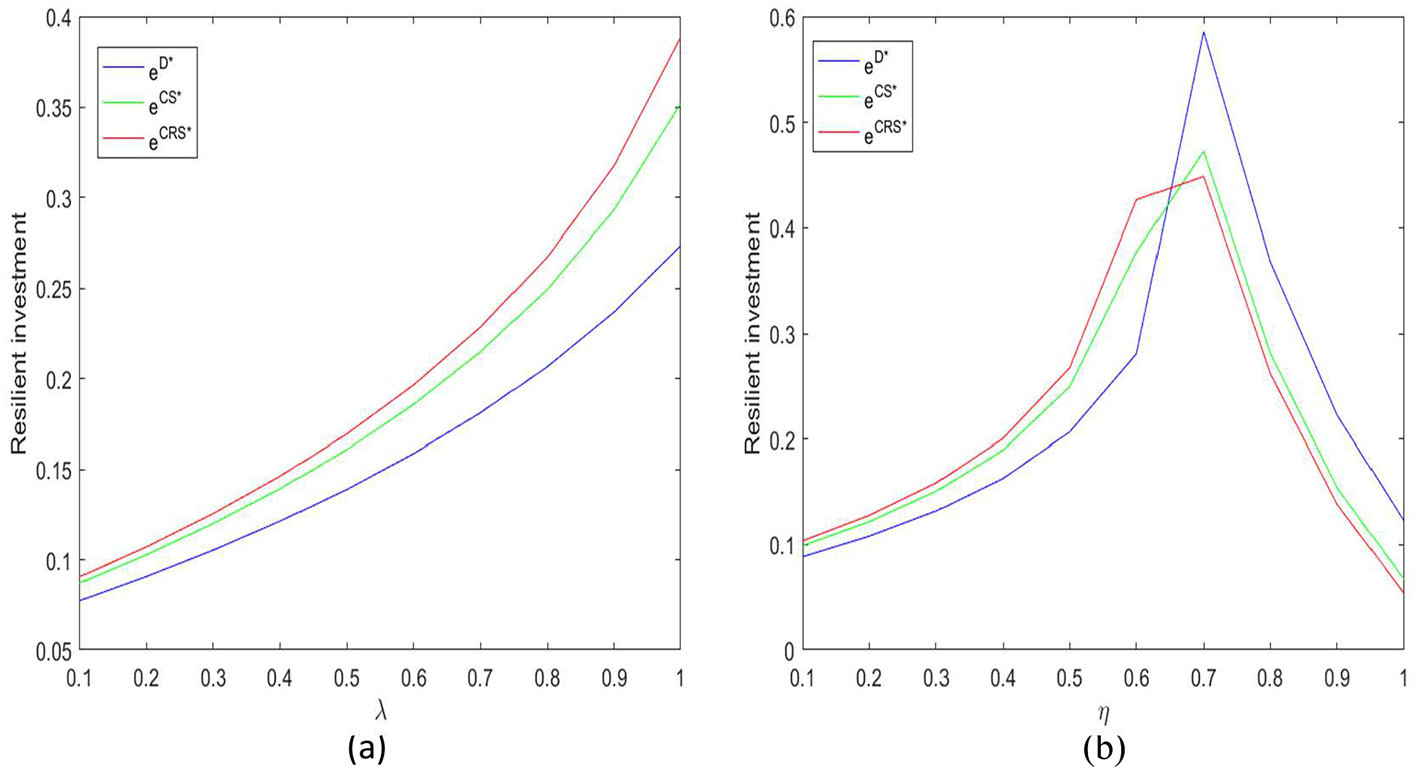

Figure 9a clearly presents the significant positive correlation between the supply chain resilience investment level e and the efficiency coefficient λ. As λ increases, that is, the enhancement effect of per unit resilience investment on the stability of the food supply chain increases, both the food supplier and the food retailer show stronger investment willingness, reflecting the direct impact of “investment—return” efficiency on decision-making behavior. Among the three coordination modes, the resilience investment level under the CRS contract is always the highest, fully illustrating that this contract, through the dual mechanism of cost-sharing and revenue-sharing, effectively alleviates the free-rider tendency and investment externality problems among food supply chain members, thereby overcoming the under-investment dilemma under decentralized decision-making and significantly enhancing the overall resilience and risk resistance capability of the food supply chain system.

Figure 9

(a, b) Effects of parameters λ and η on supply chain resilience investment level.

Figure 9b further reveals the driving effect of the demand impact coefficient η on the resilience investment level e, showing a typical inverted U-shaped relationship between the two. When η is in the low to medium range, the resilience investment under the CRS contract is the most proactive. This indicates that when resilience investment can not only enhance operational stability but also effectively stimulate market demand, this contract can maximize the willingness of food supply chain members to collaborate in investment. However, when η continues to rise into the high range, the investment level under the decentralized decision-making model surpasses that of the coordinated contract. This shift may stem from the saturation of the demand-pull effect, while the increased complexity of transaction costs and profit distribution brought by contractual coordination somewhat inhibits food companies' motivation for further investment, reflecting the applicability boundaries of coordination mechanisms under different scenarios.

6 Summary

6.1 Conclusion

This paper, by establishing a dual-channel supply chain model including a single food supplier and a single food retailer, discusses how resilience investment in the food supply chain affects system profit and channel coordination when facing demand disruption risk, and analyzes the effects of CS and CRS contracts in ensuring food supply stability. The main conclusions are as follows:

First, considering the characteristics of food being perishable and having high loss rates, research shows that resilience investment has significant economic benefits. Although it requires additional investment initially, these investments can significantly reduce the loss rate of fresh products, enhance the supply chain's ability to cope with demand fluctuations, thereby increasing the probability of normal operation, and ultimately enhancing the profit of the entire supply chain and its members. This indicates that resilience investment is not only a risk management tool but also an important strategy to ensure food safety and improve corporate competitiveness.

Second, contractual mechanisms are crucial for coordinating the behavior of supply chain members and achieving Pareto improvement. Both cost-sharing contracts and cost-sharing plus revenue-sharing contracts have been proven to incentivize members to jointly invest in resilience construction such as cold chain logistics and inventory management, thereby increasing overall profit. In particular, the CRS contract, through the dual adjustment of cost and revenue, demonstrates the best coordination effect. In links requiring high resilience investment efficiency, such as the circulation of fresh products, the CRS contract can maximize the synergistic effect, allowing both suppliers and retailers to benefit from it.

Finally, the study finds that the impact of key parameters on supply chain decisions and profits is complex. The resilience investment efficiency coefficient (λ) always has a positive promoting effect on profit and investment level, directly affecting the freshness preservation effect and market value of fresh products; while the impact coefficient of resilience investment on demand (η) shows an inverted U-shaped relationship, with an optimal interval, reflecting the sensitive balance of consumers toward food quality and price. In addition, the effect of contract coordination mechanisms is influenced by environmental parameters and may weaken in high demand response scenarios. This suggests that food enterprises should flexibly adjust their resilience strategies and contract design according to different market environments to adapt to changes and maximize benefits.

6.2 Management implications

According to the research results, food supply chain managers should adopt targeted resilience investment strategies, prioritizing investment in areas with high returns. Research shows that increasing the resilience investment efficiency coefficient (λ) can continuously enhance profits. Therefore, blind comprehensive investment should be avoided; instead, cost-benefit analysis should be used to find the best investment points in different links, prioritizing those areas that can bring the greatest benefits. For fresh and short-shelf-life foods, the focus should be on digital traceability systems and flexible logistics networks; for standardized packaged foods, more attention can be paid to supply chain visibility platforms and multi-channel inventory sharing systems to maximize investment return.

Enterprises also need to establish flexible contract coordination mechanisms to ensure alignment with product characteristics. Research shows that the effect of the cost-sharing plus revenue-sharing contract (CRS) depends on the product's characteristic parameters. For example, for high-end foods sensitive to demand, such as organic food or imported fresh products, a supplier-led CRS contract should be adopted; for price-sensitive bulk foods, a simpler cost-sharing contract is more suitable. This product-characteristic-based differentiated contract design helps avoid coordination failures caused by a unified model.

Building a demand-oriented pricing system is crucial for realizing the value of resilience. Research points out that although resilience investment increases market prices, there is an optimal interval. Managers should effectively communicate quality assurance and safety commitments to customers in the initial stage; use digital tools to monitor the demand impact coefficient (η) in real-time, and adjust prices promptly when η rises; and establish a price elasticity monitoring mechanism to proactively adjust strategies when η declines, preventing excessive price increases from causing sales declines. Promoting the digital upgrade of the supply chain is key to precise resilience management. Research reveals the complex relationship between resilience investment and operational parameters, which is difficult to optimize effectively with traditional management methods. Managers should accelerate the establishment of a unified supply chain data platform, use intelligent decision support systems to simulate the effects of different resilience investment schemes, and set up digital dashboards to continuously monitor and display key indicators (such as λ and η), thereby achieving refined management.

Finally, enterprises need to build cross-enterprise collaborative networks, going beyond the boundaries of a single enterprise to enhance overall resilience. Research shows that supply chain performance under centralized decision-making is optimal. This means that managers should jointly formulate resilience construction plans with core partners, actively participate in industry-level standard setting, and promote the interconnection and resource sharing of infrastructure. At the same time, explore cooperation with financial institutions to develop financial products specifically for supply chain resilience, forming a sustainable development resilience ecosystem.

Statements

Data availability statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/supplementary material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Author contributions

LL: Project administration, Supervision, Validation, Writing – review & editing, Data curation, Methodology, Software, Writing – original draft. SM: Investigation, Writing – original draft. KK: Data curation, Writing – original draft, Methodology, Project administration, Software, Supervision, Validation, Writing – review & editing. ZJ: Conceptualization, Formal analysis, Funding acquisition, Validation, Writing – original draft. XL: Investigation, Methodology, Project administration, Resources, Writing – original draft. CL: Conceptualization, Data curation, Software, Visualization, Writing – review & editing. RD: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Validation, Writing – review & editing. JL: Formal analysis, Investigation, Visualization, Writing – review & editing. YL: Conceptualization, Data curation, Funding acquisition, Resources, Writing – review & editing. MY: Project administration, Resources, Software, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declared that financial support was received for this work and/or its publication. This work was supported by Guangxi Key R&D Plan (Guike AB23026014), Guangxi Philosophy and Social Science Research Project (25SHB345), Innovation Project of Guangxi Graduate Education (JGY2024045), and by Guangxi Human Resources and Social Security Research Project (GXRS2025058).

Conflict of interest

ZJ was employed by company Zhejiang Guocai Urban Services Co., Ltd. JL was employed by company Guangxi Dakangyang Tourism Development Co., Ltd. MY was employed by company Guangzhou Caseeder Technology Co., Ltd. The remaining author(s) declared that this work was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The author(s) declared that generative AI was not used in the creation of this manuscript.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

1

Al-Hakimi M. A. Saleh M. H. Borade D. B. (2021). Entrepreneurial orientation and supply chain resilience of manufacturing SMEs in Yemen: the mediating effects of absorptive capacity and innovation. Heliyon7:e08145. doi: 10.1016/j.heliyon.2021.e08145

2

Ali I. Golgeci I. Arslan A. (2023). Achieving resilience through knowledge management practices and risk management culture in agri-food supply chains. SCM28, 284–299. doi: 10.1108/SCM-02-2021-0059

3

Amorim P. G. Mathias M. A. S. Rocha A. B. T. D. Oliveira O. J. D. (2023). Understanding and implementing environmental management in small entrepreneurial ventures: supply chain management, production and design. JSBED30, 1445–1475. doi: 10.1108/JSBED-08-2022-0344

4

Asamoah D. Agyei-Owusu B. Ashun E. (2020). Social network relationship, supply chain resilience and customer-oriented performance of small and medium enterprises in a developing economy. BIJ27, 1793–1813. doi: 10.1108/BIJ-08-2019-0374

5

Bahrami M. Shokouhyar S. (2022). The role of big data analytics capabilities in bolstering supply chain resilience and firm performance: a dynamic capability view. ITP35, 1621–1651. doi: 10.1108/ITP-01-2021-0048

6

Birkel H. Hohenstein N.-O. Hähner S. (2023). How have digital technologies facilitated supply chain resilience in the COVID-19 pandemic? An exploratory case study. Comp. Ind. Eng. 183:109538. doi: 10.1016/j.cie.2023.109538

7

Chen K. Zhou H. Lei D. (2021). Two-period pricing and ordering decisions of perishable products with a learning period for demand disruption. JIMO17:3131. doi: 10.3934/jimo.2020111

8

Chowdhury M. M. H. Quaddus M. (2017). Supply chain resilience: conceptualization and scale development using dynamic capability theory. Int. J. Prod. Econ.188, 185–204. doi: 10.1016/j.ijpe.2017.03.020

9

Diaz E. M. Cunado J. De Gracia F. P. (2023). Commodity price shocks, supply chain disruptions and U.S. inflation. Finance Res. Lett. 58:104495. doi: 10.1016/j.frl.2023.104495

10

Dong G. Wei L. Xie J. Zhang W. Zhang Z. (2019). Two-echelon supply chain operational strategy under portfolio financing and tax shield. IMDS120, 633–656. doi: 10.1108/IMDS-07-2019-0395

11

Drozdibob A. Sohal A. Nyland C. Fayezi S. (2023). Supply chain resilience in relation to natural disasters: framework development. Prod. Plann. Control34, 1603–1617. doi: 10.1080/09537287.2022.2035446

12

Gaudenzi B. Pellegrino R. Confente I. (2023). Achieving supply chain resilience in an era of disruptions: a configuration approach of capacities and strategies. SCM28, 97–111. doi: 10.1108/SCM-09-2022-0383

13

Ge X. Yang J. Wang H. Shao W. (2020). A fuzzy-TOPSIS approach to enhance emergency logistics supply chain resilience. IFS38, 6991–6999. doi: 10.3233/JIFS-179777

14

He Y. Wang S. (2012). Analysis of production-inventory system for deteriorating items with demand disruption. Int. J. Prod. Res.50, 4580–4592. doi: 10.1080/00207543.2011.615351

15

Hendry L. C. Stevenson M. MacBryde J. Ball P. Sayed M. Liu L. (2019). Local food supply chain resilience to constitutional change: the Brexit effect. Int. J. Oper. Prod. Manage.39, 429–453. doi: 10.1108/IJOPM-03-2018-0184

16

Hosseini-Motlagh S.-M. Nouri-Harzvili M. Choi T.-M. Ebrahimi S. (2019). Reverse supply chain systems optimization with dual channel and demand disruptions: sustainability, CSR investment and pricing coordination. Inf. Sci.503, 606–634. doi: 10.1016/j.ins.2019.07.021

17

Hu Y. Lin J. Su X.-L. (2020). Channel selection decision in a dual-channel supply chain: a consumer-driven perspective. IEEE Access8, 145634–145648. doi: 10.1109/ACCESS.2020.3014396

18

Ivanov D. Dolgui A. Sokolov B. Ivanova M. (2017). Literature review on disruption recovery in the supply chain. Int. J. Prod. Res.55, 6158–6174. doi: 10.1080/00207543.2017.1330572

19

Jain V. Kumar S. Soni U. Chandra C. (2017). Supply chain resilience: model development and empirical analysis. Int. J. Prod. Res.55, 6779–6800. doi: 10.1080/00207543.2017.1349947

20

Junaid M. Zhang Q. Cao M. Luqman A. (2023). Nexus between technology enabled supply chain dynamic capabilities, integration, resilience, and sustainable performance: an empirical examination of healthcare organizations. Technol. Forecasting Soc. Change196:122828. doi: 10.1016/j.techfore.2023.122828

21

Kazancoglu I. Ozbiltekin-Pala M. Kumar Mangla S. Kazancoglu Y. Jabeen F. (2022). Role of flexibility, agility and responsiveness for sustainable supply chain resilience during COVID-19. J. Cleaner Prod.362:132431. doi: 10.1016/j.jclepro.2022.132431

22

Khanlarzade N. Yegane B. Y. (2022). Strategic inventory management of deteriorating products with demand disruptions. Arab J. Sci. Eng.47, 15095–15115. doi: 10.1007/s13369-022-07134-4

23

Lee S. M. Rha J. S. (2016). Ambidextrous supply chain as a dynamic capability: building a resilient supply chain. Manage. Decis.54, 2–23. doi: 10.1108/MD-12-2014-0674

24

Lu J. Wang J. Song Y. Yuan C. He J. Chen Z. (2022). Influencing factors analysis of supply chain resilience of prefabricated buildings based on PF-DEMATEL-ISM. Buildings12:1595. doi: 10.3390/buildings12101595

25

Moadab A. Kordi G. Paydar M. M. Divsalar A. Hajiaghaei-Keshteli M. (2023). Designing a sustainable-resilient-responsive supply chain network considering uncertainty in the COVID-19 era. Expert Syst. Appl.227:120334. doi: 10.1016/j.eswa.2023.120334

26

Pathy S. R. Rahimian H. (2023). A resilient inventory management of pharmaceutical supply chains under demand disruption. Comp. Ind. Eng.180:109243. doi: 10.1016/j.cie.2023.109243

27

Pertheban T. R. Thurasamy R. Marimuthu A. Venkatachalam K. R. Annamalah S. Paraman P. et al . (2023). The impact of proactive resilience strategies on organizational performance: role of ambidextrous and dynamic capabilities of SMEs in manufacturing sector. Sustainability15:12665. doi: 10.3390/su151612665

28

Pham H. T. Testorelli R. Verbano C. (2023). The impact of operational risk on performance in supply chains and the moderating role of integration. BJM18, 207–225. doi: 10.1108/BJM-10-2021-0385

29

Pi Z. Fang W. Zhang B. (2019). Service and pricing strategies with competition and cooperation in a dual-channel supply chain with demand disruption. Comp. Ind. Eng.138:106130. doi: 10.1016/j.cie.2019.106130

30

Qiao R. Zhao L. (2023). Highlight risk management in supply chain finance: effects of supply chain risk management capabilities on financing performance of small-medium enterprises. SCM28, 843–858. doi: 10.1108/SCM-06-2022-0219

31

Rahmani K. Yavari M. (2019). Pricing policies for a dual-channel green supply chain under demand disruptions. Comp. Ind. Eng.127, 493–510. doi: 10.1016/j.cie.2018.10.039

32

Rajesh R. (2016). Forecasting supply chain resilience performance using grey prediction. Electron. Commerce Rese. Appl.20, 42–58. doi: 10.1016/j.elerap.2016.09.006

33

Rajesh R. (2017). Technological capabilities and supply chain resilience of firms: a relational analysis using total interpretive structural modeling (TISM). Technol. Forecasting Soc. Change118, 161–169. doi: 10.1016/j.techfore.2017.02.017

34

Ray P. Jenamani M. (2016). Sourcing decision under disruption risk with supply and demand uncertainty: a newsvendor approach. Ann. Oper. Res.237, 237–262. doi: 10.1007/s10479-014-1649-8

35

Razak G. M. Hendry L. C. Stevenson M. (2023). Supply chain traceability: a review of the benefits and its relationship with supply chain resilience. Prod. Plann. Control34, 1114–1134. doi: 10.1080/09537287.2021.1983661

36

Saithong C. Lekhavat S. (2020). Derivation of closed-form expression for optimal base stock level considering partial backorder, deterministic demand, and stochastic supply disruption. Cogent Eng.7:1767833. doi: 10.1080/23311916.2020.1767833

37

Schmidt W. Raman A. (2022). Operational disruptions, firm risk, and control systems. M&SOM24, 411–429. doi: 10.1287/msom.2020.0943

38

Shi X. Chen S. Lai X. (2023). Blockchain adoption or contingent sourcing? Advancing food supply chain resilience in the post-pandemic era. Front. Eng. Manag. 10, 107–120. doi: 10.1007/s42524-022-0232-2

39

Silva M. E. Silvestre B. S. Del Vecchio Ponte R. C. Cabral J. E. O. (2021). Managing micro and small enterprise supply chains: a multi-level approach to sustainability, resilience and regional development. J. Cleaner Prod.311:127567. doi: 10.1016/j.jclepro.2021.127567

40

Siva Kumar P. Anbanandam R. (2020). Theory building on supply chain resilience: a SAP-LAP analysis. Glob. J. Flex Syst. Manag.21, 113–133. doi: 10.1007/s40171-020-00233-x

41

Soni U. Jain V. Kumar S. (2014). Measuring supply chain resilience using a deterministic modeling approach. Comp. Ind. Eng.74, 11–25. doi: 10.1016/j.cie.2014.04.019

42

Sun K.-X. Ooi K.-B. Tan G. W.-H. Lee V.-H. (2023). Enhancing supply chain resilience in SMEs: a deep learning-based approach to managing Covid-19 disruption risks. JEIM36, 1508–1532. doi: 10.1108/JEIM-06-2023-0298

43

Tiwari S. Sharma P. Jha A. K. (2024). Digitalization & Covid-19: an institutional-contingency theoretic analysis of supply chain digitalization. Int. J. Prod. Econ.267:109063. doi: 10.1016/j.ijpe.2023.109063

44

Wu D. Li P. Chen J. Wang H. (2023). Coordination strategies of dual channel closed-loop supply chain considering demand disruptions. EJIE17, 597–626. doi: 10.1504/EJIE.2023.131733

45

Xu Q. Wang W.-J. Liu Z. Tong P. (2018). The influence of online subsidies service on online-to-offline supply chain. Asia Pac. J. Oper. Res. 35:1840007. doi: 10.1142/S0217595918400079

46

Xue W. Xu Z. (2022). The impacts of government subsidies and consumer preferences on food supply chain traceability under different power structures. Sustainability15:470. doi: 10.3390/su15010470

47

Yan B. Chen Z. Liu Y.-P. Chen X.-X. (2021). Pricing decision and coordination mechanism of dual-channel supply chain dominated by a risk-aversion retailer under demand disruption. RAIRO-Oper. Res. 55, 433–456. doi: 10.1051/ro/2021013

48

Yang A.-T. Zhao L.-D. (2011). Supply chain network equilibrium with revenue sharing contract under demand disruptions. Int. J. Autom. Comput. 8, 177–184. doi: 10.1007/s11633-011-0571-7

49

Yang Z. Shang W.-L. Miao L. Gupta S. Wang Z. (2024). Pricing decisions of online and offline dual-channel supply chains considering data resource mining. Omega126:103050. doi: 10.1016/j.omega.2024.103050

50

Yavari M. Mihankhah S. Jozani S. M. (2024). Assessing cap-and-trade regulation's impact on dual-channel green supply chains under disruption. J. Cleaner Prod.478:143836. doi: 10.1016/j.jclepro.2024.143836

51

Yu N. Zhang Z. Cai X. (2025). Manufacturer's online channel encroachment with consumer fairness concern. J. Syst. Sci. Syst. Eng. 1–27. doi: 10.1007/s11518-025-5654-z

52

Yu Y. Yang H. Zhen Z. (2023). Collection cooperation breakdown and repair in a closed-loop supply chain during supply disruption and price shock. Comp. Ind. Eng.183:109495. doi: 10.1016/j.cie.2023.109495

53

Zhai Y. Bu C. Zhou P. (2022). Effects of channel power structures on pricing and service provision decisions in a supply chain: a perspective of demand disruptions. Comp. Ind. Eng.173:108715. doi: 10.1016/j.cie.2022.108715

54

Zhao N. Liu X. Wang Q. Zhou Z. (2022). Information technology-driven operational decisions in a supply chain with random demand disruption and reference effect. Comp. Ind. Eng.171:108377. doi: 10.1016/j.cie.2022.108377

Summary

Keywords

cost-sharing contract, demand disruption, dual-channel supply chain, revenue-sharing contract, Stackelberg game, supply chain resilience

Citation

Lu L, Mao S, Kang K, Jiang Z, Luo X, Li C, Dong R, Lu J, Li Y and Yuan M (2026) Countering demand disruptions: the role of resilience investment and contract design in food supply chains. Front. Sustain. Food Syst. 9:1715345. doi: 10.3389/fsufs.2025.1715345

Received

29 September 2025

Revised

30 November 2025

Accepted

26 December 2025

Published

16 February 2026

Volume

9 - 2025

Edited by

José Antonio Teixeira, University of Minho, Portugal

Reviewed by

Abdel Moneim Elhadi Sulieman, University of Hail, Saudi Arabia

Xuefeng Wang, Jiangxi University of Finance and Economics, China

Updates

Copyright

© 2026 Lu, Mao, Kang, Jiang, Luo, Li, Dong, Lu, Li and Yuan.

This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Zubai Jiang, 262612479@qq.com; Xiaochun Luo, luoxiaochun@nuaa.edu.cn; Chaoling Li, lichaoling@mailbox.gxnu.edu.cn

†These authors share first authorship

Disclaimer

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.