Abstract

The Small Island Developing States (SIDS) are epicenters of a global climate crisis where agricultural systems, particularly the historically vital sugarcane sector, face existential threats. The academic and policy responses to this crisis, however, have been defined by a critical flaw: a deep-seated fragmentation that addresses biophysical, socioeconomic, and institutional challenges in isolation. This paradigm has demonstrably failed to build meaningful resilience. This study challenges this fragmented approach by proposing a new conceptual model: the integrated resilience framework. We posit that sustainable resilience is not an additive outcome of piecemeal interventions but an emergent property of the synergistic interplay between three core pillars: biophysical capacity, socioeconomic empowerment, and institutional agility. Grounded in a critical synthesis of global literature and empirical evidence from Fiji, this study first deconstructs the climate threat as an interconnected cascade, where biophysical shocks trigger systemic socioeconomic decay. It then moves to a critique of the current adaptation landscape, arguing that its persistent failures stem from a fundamental inability to address this systemic complexity. The proposed framework offers a direct theoretical and practical alternative, conceptualizing resilience as a holistic system underpinned by catalytic enablers such as predictive analytics and targeted finance. In doing so, this study provides a theoretically robust and actionable model to guide the necessary paradigm shift from managing vulnerability to actively architecting long-term viability in the world’s most climate-exposed agricultural systems.

1 Introduction

The specter of anthropogenic climate change haunts global agriculture, creating systemic disruptions that threaten food security and rural livelihoods (IPCC, 2022). Within this global panorama, the sugarcane (Saccharum officinarum L.) economy of the Small Island Developing States (SIDS) represents a unique crucible of vulnerability. Despite being a globally significant commodity (Waclawovsky et al., 2010) in the island nations of the Pacific, Caribbean, and Indian Ocean, sugarcane is more than a crop; it is a legacy, a cornerstone of post-colonial economies, rural employment, and cultural identity (Ali and Narayan, 1989; Chand, 2015; Narayan and Prasad, 2005). Yet, the very systems that underpin this legacy are now profoundly threatened. To understand this threat, however, one must look beyond climate models to the political economy of the sector. In Fiji, the industry is not comprised of large corporate plantations but of over 11,000 smallholder farmers. Crucially, the land tenure system where farmers lease land from the iTaukei Land Trust Board rather than owning it creates a structural disincentive for long-term investment in climate-resilient infrastructure such as irrigation (Chand, 2015). Recent analyses reinforce that these challenges are multifaceted. Khan and Yun (2025) and Medina Hidalgo et al. (2024) identified a complex matrix of “climatic and non-climatic stressors,” arguing that transformation is impossible without addressing these structural barriers.

The defining geography of SIDS, their low-lying coastal topography, economic isolation, and constrained national capacities, places agriculture at the bleeding edge of climate impacts (Mycoo et al., 2022; Nurse et al., 2014). This study contends that the compounding and intensifying barrage of climatic shocks, from acute cyclones to slow-onset salinization, is creating a state of systemic risk that threatens the sector with terminal decline.

The pathways of this decline, from biophysical crop failure (Zhao and Li, 2015) to socioeconomic ruin (Morton, 2007), are increasingly understood. However, the intellectual and policy frameworks designed to address this crisis suffer from a critical and persistent flaw: a paradigm of fragmentation. Biophysical science exists in one silo, socioeconomic analysis in another, and policy formulation in a third (Betzold, 2015). This disciplinary disjuncture has yielded a portfolio of piecemeal, reactive, and ultimately inadequate solutions that fail to grasp the interconnected nature of the problem.

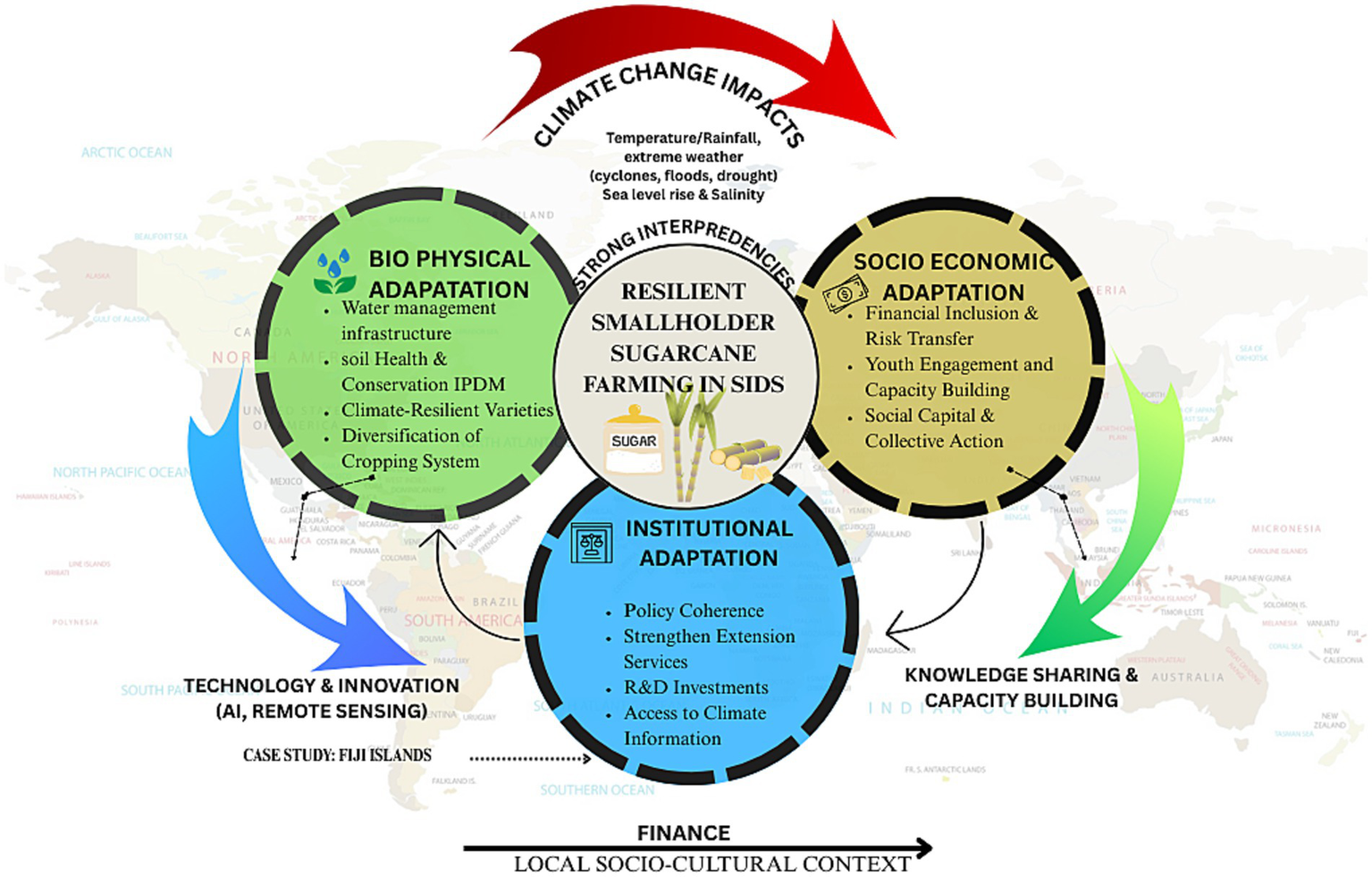

This study directly confronts this inadequacy. We argued that the failure to build meaningful resilience stems from the absence of a truly integrated conceptual model. To fill this critical void, we proposed the integrated resilience framework. Our central thesis is that sustainable resilience is not an additive outcome of isolated technical or policy fixes. Rather, it is an emergent property that arises from the purposeful, synergistic alignment of interventions across three interdependent domains: biophysical capacity, socioeconomic empowerment, and institutional agility. This framework offers a new theoretical lens for understanding and acting upon the climate challenge in SIDS agriculture, one that shifts the focus from managing discrete symptoms to transforming the underlying system.

Through a critical synthesis of existing literature, anchored by the illustrative case of Fiji, this study builds the argument for this new paradigm. We first establish the threat not as a list of impacts but as a socio-ecological cascade, demonstrating that a fragmented response is destined to fail. We then deconstruct the current adaptation landscape to diagnose the failures of the status quo. Finally, we present our framework as a robust conceptual alternative, outlining a strategic and integrated pathway toward a viable future for sugarcane in the world’s most vulnerable regions.

2 Methodology: a conceptual review approach

This manuscript employs a conceptual review methodology. While informed by the systematic search protocols of the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) framework (Page et al., 2021), its primary objective is not an exhaustive summary, but a critical synthesis aimed at theoretical proposition. The approach involves a comprehensive search of academic and gray literature (2010–2025) to marshal evidence, followed by a narrative synthesis (Popay et al., 2006). This method integrates heterogeneous evidence—from quantitative crop models to qualitative ethnographic studies—to reveal the “Driver-Dependent” fragmentation that currently hinders effective policy formulation in SIDS.

2.1 Search strategy and data sources

To ensure a rigorous and contemporary analysis, this study conducts a comprehensive literature review across prominent academic databases, including the Web of Science, Scopus, ScienceDirect, SpringerLink, and the Wiley Online Library, covering publications up to January 2025.

To incorporate critical policy- and practice-oriented insights, this review is supplemented with gray literature from the digital archives of key international and regional bodies. These include the Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO), the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC), the World Bank, the Asian Development Bank (ADB), the Caribbean Community (CARICOM), and the Pacific Community (SPC), alongside relevant reports from Fijian government ministries and the Fiji Sugar Corporation (FSC).

A structured search methodology uses Boolean operators to combine specific crop, climate, and regional terms. For example, search strings link terms such as sugarcane with climate change and climate variability. Other queries combine geographical indicators such as SIDS or Fiji with agricultural terms and concepts of climate adaptation or resilience, specifically those related to stressors.

2.2 Inclusion and exclusion criteria

The criteria for including studies in the review were carefully defined to ensure relevance and quality. These are summarized in Table 1.

Table 1

| Criteria | Inclusion | Exclusion |

|---|---|---|

| Subject matter | Must directly address climate change impacts or adaptation in sugarcane systems. | Studies unrelated to the nexus of climate change and sugarcane. |

| Geographic focus | Studies focusing on SIDS or providing comparable tropical contexts relevant to smallholders. | Research focuses exclusively on large-scale industrial plantations without transferable lessons. |

| Publication type | Peer-reviewed journal articles, policy reports, and technical papers from recognized organizations. | Conference abstracts, non-peer-reviewed theses, and opinion pieces. |

| Language and access | Full-text articles available in the English language. | Non-English publications; abstracts without full text. |

| Timeframe | Published between January 2010 and March 2025. | Publications outside the specified timeframe. |

Inclusion and exclusion criteria for the systematic review.

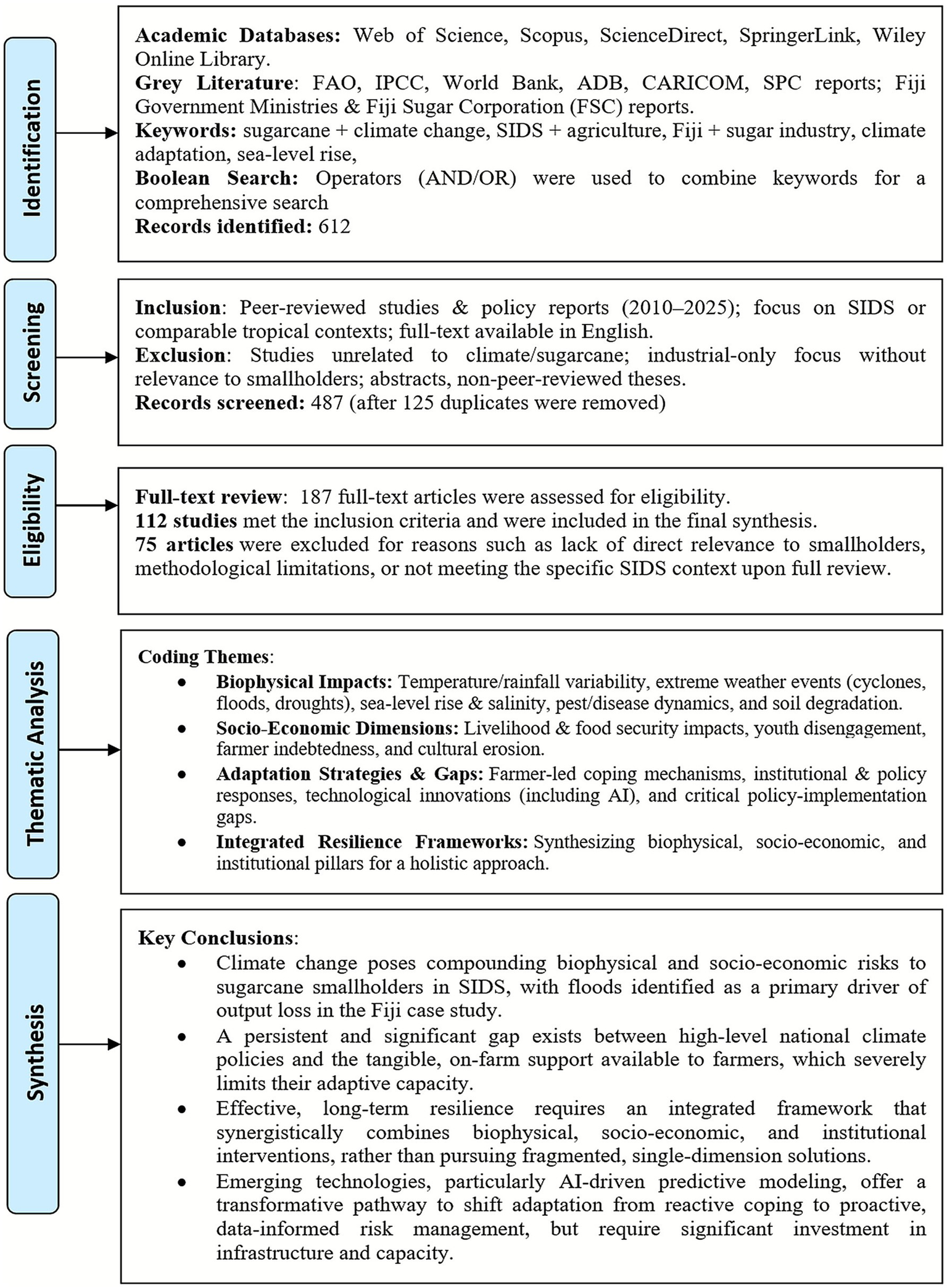

2.3 Study selection and synthesis

The initial search yielded 612 records. After removing duplicates, titles and abstracts were screened, resulting in 187 articles for full-text review. Of these, 112 met the final inclusion criteria. Given the heterogeneity of the methodologies in the included studies, ranging from econometric models to qualitative case studies, a narrative synthesis was used rather than a quantitative meta-analysis (Popay et al., 2006). This approach enabled the comparison of themes across diverse regions and facilitated the critical integration of empirical evidence to enhance the contextual relevance and impact of the findings for the SIDS context.

Data synthesis proceeded in two stages:

-

Thematic coding: To generate the quantitative diagnosis presented in the results, the included studies were coded based on their primary variable of analysis.

-

Structural classification: Drawing on the systems theory logic used by Sulaiman et al. (2023), studies were classified into three distinct structural domains:

-

Independent domain: Studies focusing exclusively on biophysical drivers (e.g., yield, pest, and soil).

-

Dependent domain: Studies focusing exclusively on socioeconomic outcomes (e.g., profit, labor, and debt).

-

Linkage domain: Studies using integrated methodologies connecting drivers to outcomes.

This classification protocol allowed for the quantitative assessment of fragmentation and formed the empirical foundation for the proposed integrated resilience framework.

3 Results and discussion: diagnostic synthesis and conceptual proposition

3.1 Structural classification of research themes

To construct a robust conceptual framework, we first used a systematic search strategy (see Methodology) to diagnose the structural failures in the current body of knowledge. Analyzing the 112 included studies revealed that the research landscape is not merely “gapped” but structurally fragmented. Drawing on the systems theory logic used by Sulaiman et al. (2023), we classified the current literature into three distinct domains based on their “driver power” (influence) versus “dependence.”

First, the independent domain (biophysical drivers) is dominated by biophysical research. Quantitative coding reveals a significant skew where approximately 48% of reviewed studies focused exclusively on biophysical impacts such as yield modeling under heat stress, soil salinity dynamics, or pest prevalence. In a conceptual system, these act as “independent drivers.” They identify the root causes of production decline (the biophysical shock) but rarely analyze the downstream human consequences. While technically rigorous, this isolation renders them insufficient for policy formulation because they treat the farm as a biological unit rather than a socioeconomic enterprise.

Second, the dependent domain (socioeconomic outcomes) comprises 32% of the literature. These studies address factors such as labor shortages, household income decline, or debt levels. In the context of resilience, these are “dependent variables”; they fluctuate in response to the biophysical drivers. However, current research often treats them in isolation. For instance, studies on “youth disengagement” (Khan and Yun, 2025; Medina Hidalgo et al., 2024) often describe the phenomenon without fully mapping it back to the specific biophysical drivers (e.g., heat stress making labor unbearable) that trigger it.

Third, the linkage domain—which connects biophysical drivers to socioeconomic outcomes—is critically underrepresented. Only 20% of the studies utilized a methodology that crossed these disciplinary boundaries. This structural gap explains the failure of current adaptation policies: interventions are designed for either the “driver” (e.g., irrigation infrastructure) or the “dependent” (e.g., food aid) but fail to address the feedback loops between them.

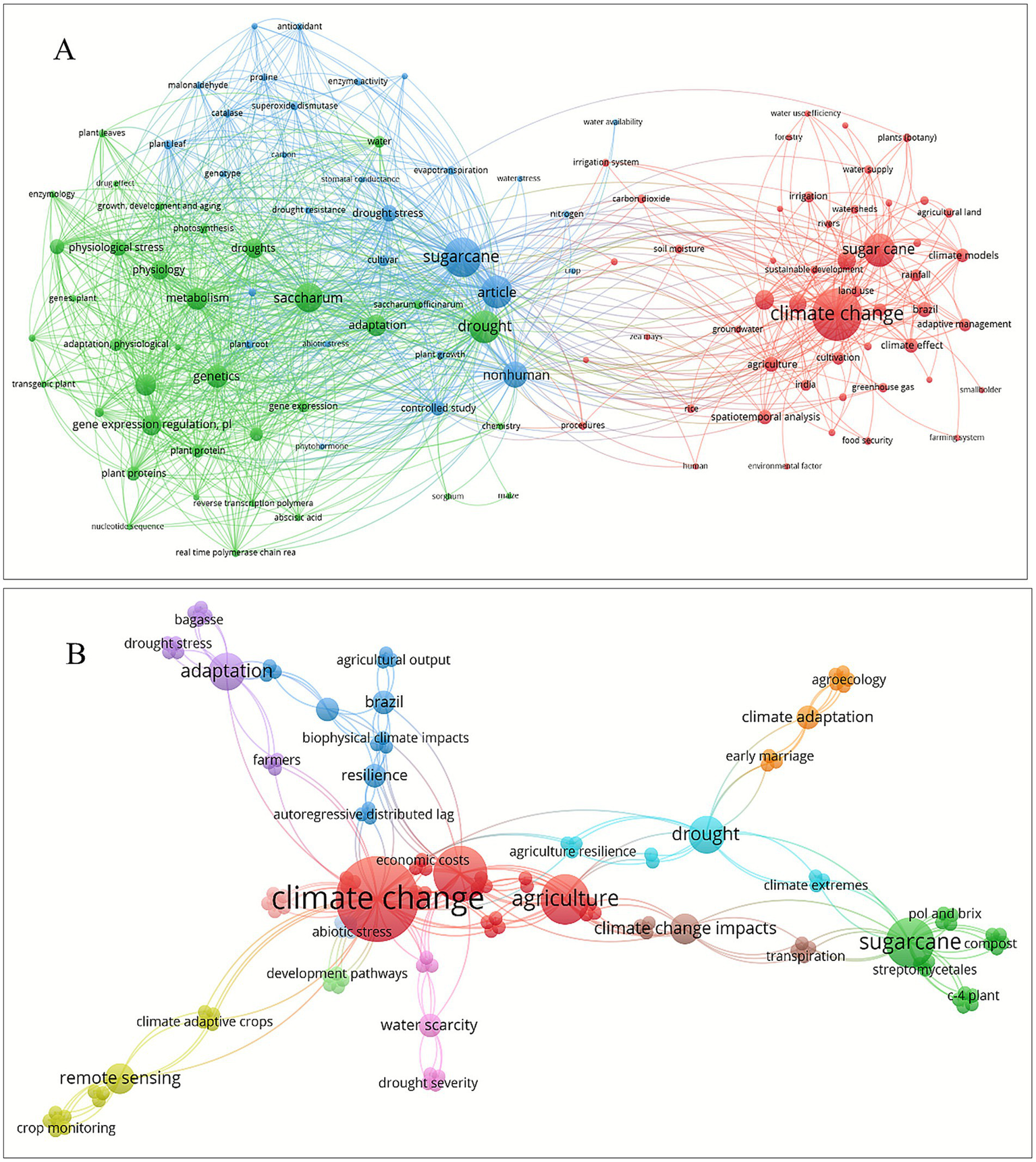

To empirically validate this qualitative coding, a supplementary bibliometric analysis was conducted using VOSviewer on data from both Scopus and Web of Science. Figure 1 presents the comparative network visualizations. Despite differences in indexing between the databases, a consistent structural fragmentation is evident in both panels. In Figure 1A (Scopus), the green cluster (deep physiology/genetics) is spatially isolated from the red cluster (climate/food security). Similarly, Figure 1B (Web of Science) reveals that technical terms such as “remote sensing” and “crop monitoring” (yellow) form distinct clusters separate from “adaptation” and “farmers” (purple). This cross-database validation confirms that the disciplinary silo is a systemic feature of the global research landscape, not an artifact of a single database (Figure 2).

Figure 1

Comparative bibliometric network visualization of keyword co-occurrences in sugarcane resilience literature (2010–2025). (A) The Scopus dataset (n = 176) shows a distinct polarity between deep physiological research (green cluster, left) and macro-level climate/social research (red cluster, right). (B) The Web of Science Dataset (n = 121) corroborates this trend, with agricultural/biophysical terms (green/blue) spatially distinct from adaptation strategies (purple/orange). Across both databases, the “hollow center” indicates a lack of integrated research connecting biological drivers to socioeconomic outcomes.

Figure 2

PRISMA-adapted research framework guiding the synthesis of literature on climate change impacts and resilience in sugarcane smallholder systems in SIDS.

3.2 Global parallels and structural isomorphism

The review identified that the structural challenges in SIDS are not isolated but share characteristics with continental systems, suggesting a “structural isomorphism” in smallholder sugarcane vulnerability. Research from India provides critical parallels regarding the “driver power” of infrastructure and ecosystem management:

-

Infrastructure as a driver: Research by Wadghane and Madguni (2023) on “agriculture water poverty status” in Maharashtra highlighted that even in irrigated zones, structural inefficiencies and inequitable distribution lead to significant water stress. This mirrors the situation in Fiji’s rain-fed belts, where water access is determined more by infrastructure maintenance (the driver) than raw rainfall.

-

Economic viability as dependent: Wadghane (2022) analyzed the “sustainability management status” of farmers in Shevgaon and Paithan in India. Their findings indicate that without sustainable management of the wider agro-ecosystem, the economic viability of smallholders (the dependent variable) deteriorates rapidly under stress.

-

The need for holistic assessment: Wadghane et al. (2025) used the Sustainability Assessment of Food and Agriculture systems (SAFA) framework to analyze sugarcane in Marathwada. They concluded that environmental resilience cannot be sustained without simultaneous improvements in economic governance, a finding that directly supports the multi-pillar approach proposed in this study.

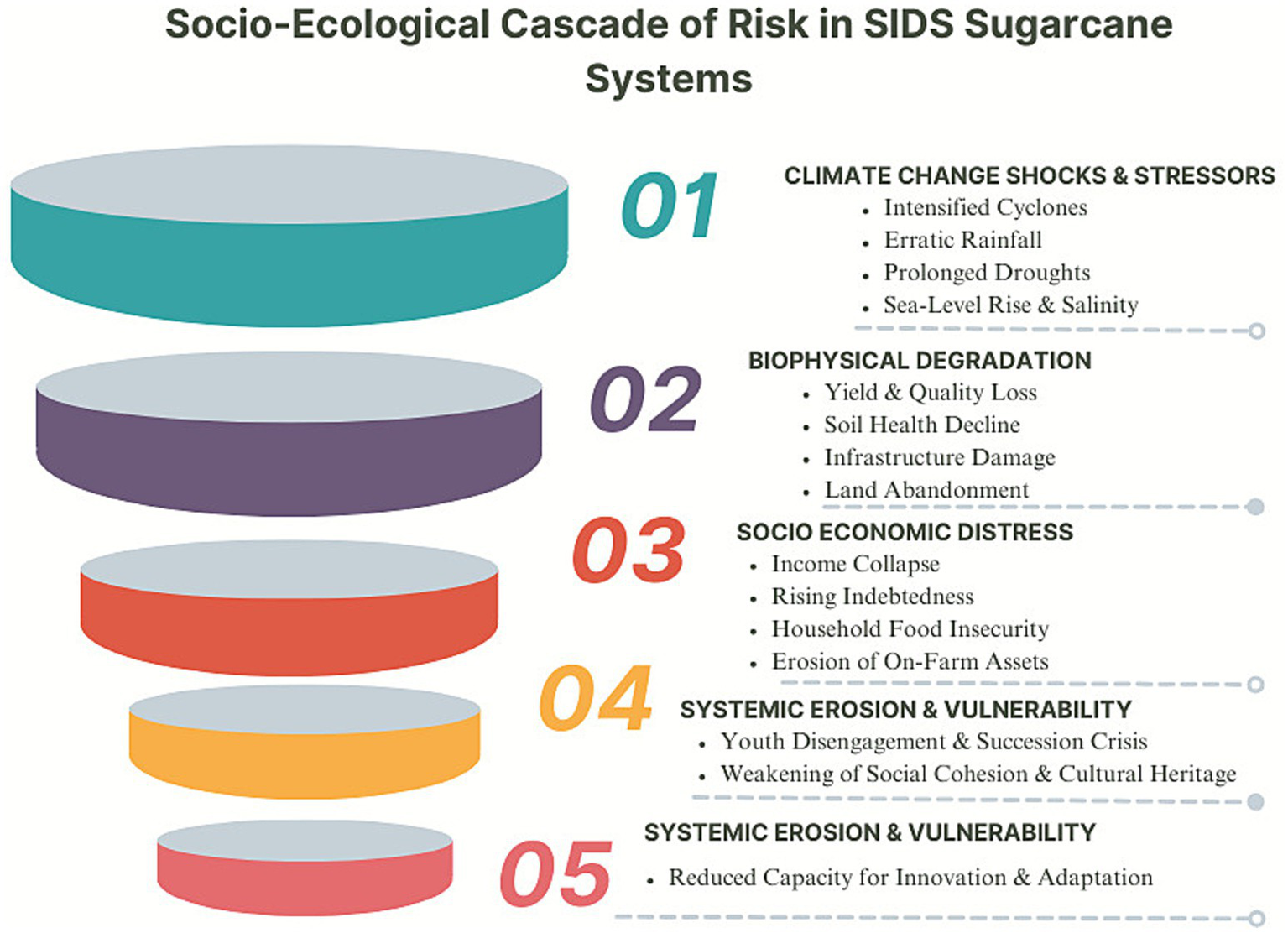

3.3 Hierarchy of vulnerability: the socio-ecological cascade

To justify an integrated solution, the problem must be conceptualized not as a series of discrete events but as a hierarchical system. This study conceptualizes this process as a “hierarchy of vulnerability,” visually represented in Figure 3. This model illustrates how initial driver variables (biophysical shocks) propagate through the system to impact dependent variables (socioeconomic decay).

Figure 3

Socio-ecological cascade of risk in SIDS sugarcane systems.

3.3.1 Level 1: the biophysical trigger (driver variables)

The cascade begins with the disruption of sugarcane’s core biophysical systems. Climate change pushes the crop beyond its evolved physiological thresholds (Gupta et al., 2017). Gradual shifts in temperature and rainfall create a new baseline of chronic stress, degrading sucrose content and disrupting production cycles (Bedia et al., 2015; Singh et al., 2022). In the structural model, these are independent drivers. Table 2 synthesizes the evidence for this initial trigger, demonstrating how these gradual climatic shifts systematically erode productive capacity.

Table 2

| Region | Hazard | Documented impact | Illustrative source |

|---|---|---|---|

| Fiji (western division) | Floods, irregular rainfall, and cyclones | Reduced yields, loss of crops, and reduced income, leading to food insecurity. | Nand et al. (2023), Senapati (2020) |

| India (Uttar Pradesh) | Heat stress during ripening | Reduced sucrose content and shortened maturation period. | Gupta et al. (2017), Pathak et al. (2019) |

| Brazil (São Paulo) | El Niño-Southern Oscillation (ENSO)-linked rainfall deficits | 15–20% annual yield losses. | Marin et al. (2013), Teixeira et al. (2016) |

| Mauritius | Erratic rainfall patterns | Delays in harvesting operations and lower overall cane quality. | Lalljee et al. (2018) |

Biophysical trigger: global evidence of sugarcane system degradation from chronic climate stress.

3.3.2 Level 2: acute shock propagation

Acute shocks act as accelerators within the hierarchy. The catastrophic impact of Tropical Cyclone Winston in Fiji, which destroyed approximately 80% of the harvest (Fiji Government, 2021; FSC, 2024; SCGC, 2020), serves as empirical testament to the force of these shocks. As illustrated in Table 3, these events do not merely damage the crop; they destroy the asset base required for recovery, effectively severing the link between effort and reward (Table 4).

Table 3

| Region | Hazard | Documented impact | Estimated economic loss | Illustrative source |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fiji | Cyclone Winston (2016) | Approx. 80% crop loss in the majority of affected areas, crippling the sector for the season. | >FJ$500 million (agricultural sector) | Chand (2020), Fiji Government (2016), Paulik et al. (2025) |

| Caribbean (Cuba, Barbados) | Pasch et al. (2018) and Cangialosi et al. (2018) | Sector-wide destruction of crops and critical infrastructure (e.g., mills and transport). | Hundreds of millions USD | Febles and Félix (2020), Galaitsi et al. (2024), UNDP (2018) |

| India/SE Asia | 2015–2016 El Niño Drought | Widespread, multi-regional cane yield declines. | Triggered a contraction in global sugar exports, demonstrating systemic supply chain risk. | Bhatla et al. (2023),Pandey et al. (2019), Pipitpukdee et al. (2020), UN ESCAP (2015) |

Force of acute shocks: documented catastrophic losses from extreme weather events.

Table 4

| Theme | Evidence from Fiji | Corroborating global parallels |

|---|---|---|

| Livelihood and food security collapse | Climate shocks increase farming costs, worsen labor shortages, and reduce incomes, forcing households to cut spending on education, healthcare, and food (~200,000 livelihoods affected) (Dean, 2022; FSC, 2023; Medina Hidalgo et al., 2020; Nand et al., 2023; Shukla et al., 2022) | Jamaica: Drought-induced poverty spikes among cane-farming households (Burrell, 2016; Floering, 2024). Mauritius: Forced diversification into precarious off-farm work (Linnenluecke et al., 2018; Sultan, 2021) |

| Youth disengagement and succession crisis | Younger generations migrate to urban centers, viewing farming as unviable; a clear decline in intergenerational farm transfers is observed (FAO, 2020; Medina Hidalgo et al., 2024; Prakash and Nakamura, 2024) | Caribbean: A systemic issue of an aging farmer demographic (Lowitt et al., 2015; NU. CEPAL, 2019) Mauritius: Documented preference among youth for exiting agriculture for tourism sector jobs (Olkeba et al., 2024; UNCTAD, 2017) |

| Indebtedness and rising costs | A vicious cycle where climate-induced crop failures make seasonal loans from the FSC unpayable, deepening poverty (Betzold, 2015; Prakash and Nakamura, 2024) | Jamaica: Pervasive debt traps resulting from price volatility and hurricane losses (Chen et al., 2020). Barbados: Input cost inflation is a primary driver of farm abandonment (Barker, 2012; Kemp-Benedict et al., 2020; World Bank Group, 2022) |

| Erosion of cultural heritage | The decline of cane farming, central to Indo-Fijian identity, leads to the fragmentation of community cohesion and cultural practices (McMichael et al., 2025; Shiiba et al., 2023) | St. Kitts & Nevis: The historical collapse of the cane industry dissolved a core component of rural identity (King, 2016; Macmillan, 2016). Mauritius: A documented shift in cultural identity away from the sugar monoculture (Lalljee et al., 2018). |

Socio-ecological cascade in action: a sourced synthesis of how biophysical triggers ignite systemic vulnerability.

3.3.3 Level 3: socioeconomic decay (dependent variables)

The biophysical drivers metastasize into socioeconomic crises. These are the dependent variables of the system, fluctuating in response to the drivers at Levels 1 and 2:

-

Livelihood collapse: Yield loss translates directly into household income collapse, forcing trade-offs in health and education (Nand et al., 2023).

-

The debt cycle: Climate volatility is a primary driver of indebtedness. Farmers take on seasonal debt that becomes unpayable after a single flood, creating a feedback loop of escalating vulnerability (Prakash and Nakamura, 2024).

-

The erosion of futurity: Perhaps, the most pernicious impact is the structural disengagement of youth, creating an aging demographic (Medina Hidalgo et al., 2024).

3.4 Identification of key strategic programs

The analysis of the current adaptation landscape (Table 5) reveals that existing interventions fail because they are fragmented. Top–down institutional responses are characterized by a debilitating disconnect between intent and impact, while technological solutions often present as “silver bullets” without regard for context (Dhanaraj et al., 2025). To address this, we identified key strategic programs that function as the “linkage elements” necessary to connect the biophysical and socioeconomic domains.

Table 5

| Level of response | Examples in Fiji | Global parallels and best practices | Critique: diagnosis of failure |

|---|---|---|---|

| Farmer-led | Trash mulching, digging rudimentary drainage channels, and adjusting planting calendars. | Intercropping with legumes (India) and community-based soil management (Jamaica). | Insufficient: Fundamentally reactive and incremental; capacity is overwhelmed by large-scale shocks; chronically under-supported. |

| Institutional | Climate Change Act 2021, National Adaptation Plan (NAP), and FSC seasonal advances. | National crop insurance schemes (India) and strategic sector diversification (Mauritius). | Disconnected: A persistent chasm between policy design and implementation reality fails to account for smallholder socioeconomic constraints. |

| Technological | Promotion of climate-smart agriculture practices; nascent interest in predictive modeling. | Widespread use of precision agriculture (Brazil) and advanced breeding programs (India). | Inaccessible: Presented as a panacea without addressing barriers of cost, digital literacy, and lack of support, rendering it an illusion for the majority of smallholders. |

Critique of the fragmented paradigm: diagnosing systemic failures in the current adaptation landscape.

Strategic program a: financial resilience (parametric insurance)

Function: Independent driver of stability

Current indemnity-based insurance is too slow and administratively costly. We propose a transition to parametric (index-based) insurance. As highlighted by Medina Hidalgo et al. (2024), these products trigger automatic payouts when rainfall drops below a specific threshold. This provides immediate liquidity before farmers enter the “vicious cycle of debt,” effectively stabilizing the dependent economic variables at Level 3.

Strategic program B: technological resilience (frugal innovation)

Function: Linkage mechanism

Current techno-centric pushes for precision agriculture are often inaccessible abstractions for indebted smallholders. Instead, the focus must be on “frugal innovation” via digital extension. Leveraging mobile penetration, agencies should deploy WhatsApp-based vernacular advisory services. This approach mirrors successful interventions in India identified by Wadghane et al. (2025), bridging the information gap without requiring expensive hardware.

Strategic program C: institutional resilience (cross-ministry coordination)

Function: Key actor/enabler

The “key actor” in this framework is the institutional structure. We recommend the establishment of a Cross-Ministry Climate Resilience Taskforce. Since drainage is often a public works responsibility but critical for sugarcane (agriculture), a shared budgetary framework is the only mechanism to ensure structural drivers (infrastructure) are managed effectively. This aligns with the need to transform rigid, top–down institutions into agile systems (Pillar 3 of the Framework).

The integrated resilience framework (Figure 4) illustrates this architecture, emphasizing that durable resilience is not an additive outcome of piecemeal interventions but an emergent property of these interconnected strategic programs.

Figure 4

The integrated resilience framework. This conceptual model illustrates the system architecture required to overcome structural fragmentation. It synthesizes three core pillars: Biophysical Capacity, Socioeconomic Empowerment, and Institutional Agility. While grounded in the Fiji case study (bottom left), the framework addresses universal SIDS vulnerabilities, proposing that resilience is an emergent property of these interconnected systems rather than isolated interventions.

4 Conclusion: a new paradigm for research and action

This study has prosecuted an argument against the paradigm of fragmentation. Through a systematic review, we demonstrated that current responses fail by addressing challenges in isolation. The parallels drawn from the sugarcane belts of Maharashtra (Wadghane, 2022; Wadghane et al., 2025) confirm that this is a global challenge requiring a systemic solution.

The primary contribution of this study is the formal proposition of the integrated resilience framework as a new conceptual model. This framework offers a theoretical and practical alternative to fragmentation. Its value is in shifting the objective from the implementation of isolated projects to the cultivation of emergent systemic properties. It provides a common language and a logical structure for coordinating the actions of researchers, policymakers, development practitioners, and farmers toward a shared goal.

Adopting this framework has profound implications for both research and policy:

-

For research, the agenda must move toward understanding the dynamics of interdependency. How do specific interventions in one pillar enable or inhibit progress in others? This requires transdisciplinary, system-oriented research, including the development of integrated assessment models and action research focused on scaling equitable technology.

-

For policy, the imperative is to organize for integration. This means breaking down ministerial silos, creating genuine multi-stakeholder governance bodies, and designing funding mechanisms that incentivize cross-pillar collaboration. The immediate priority must be to bridge the policy-implementation chasm by investing in the institutional capacity needed to empower farmers as central agents in their own resilient future.

The path to a viable future for sugarcane in SIDS is undoubtedly challenging. However, it is not impossible. It requires moving beyond the comfort of isolated solutions and embracing the complexity of systemic change. The framework proposed here is not a panacea but a compass, offering a new direction for a more hopeful and resilient future.

Statements

Author contributions

SK: Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. B-WY: Supervision, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declared that financial support was not received for this work and/or its publication.

Acknowledgments

The authors gratefully acknowledge the Korea International Cooperation Agency (KOICA) for providing the scholarship opportunity that supported the first author’s master’s studies at Kyungpook National University.

Conflict of interest

The author(s) declared that this work was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The author(s) declared that Generative AI was used in the creation of this manuscript. The authors acknowledge the use of ChatGPT (OpenAI; accessed March 2025) to assist in improving the clarity and language quality of the manuscript.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

1

Ali R. Narayan J. (1989). The Fiji sugar industry: a brief history and overview of its structure and operations. Pac. Econ. Bull.4, 13–21. Available at: http://hdl.handle.net/1885/158013

2

Barker D. (2012). Caribbean agriculture in a period of global change: vulnerabilities and opportunities. Caribb. Stud.40, 41–61. doi: 10.1353/crb.2012.0027

3

Bedia J. Herrera S. Gutiérrez J. M. Benali A. Brands S. Mota B. et al . (2015). Global patterns in the sensitivity of burned area to fire-weather: implications for climate change. Agric. For. Meteorol.214, 369–379. doi: 10.1016/j.agrformet.2015.09.002

4

Betzold C. (2015). Adapting to climate change in small island developing states. Clim. Change133, 481–489. doi: 10.1007/s10584-015-1408-0

5

Bhatla R. Bhattacharyya S. Verma S. Mall R. K. Singh R. S. (2023). El nino/La nina and IOD impact on Kharif season crops over western agro-climatic zones of India. Theor. Appl. Climatol.151, 1355–1368. doi: 10.1007/s00704-023-04361-z

6

Burrell D. (2016). “The decline of preferential markets and the sugar industry: a case study of trade liberalization in Central Jamaica” in Globalization, agriculture and food in the Caribbean: climate change, gender and geography. eds. BeckfordC. L.RhineyK. (London, United Kingdom: Palgrave Macmillan), 103–128.

7

Cangialosi J. P. Latto A. S. Berg R. (2018). Tropical Cyclone Report: Hurricane Irma (AL112017), 30 August–12 September 2017. National Hurricane Center. Available at: https://www.nhc.noaa.gov/data/tcr/AL112017_Irma.pdf

8

Chand S. (2015). The political economy of Fiji: past, present, and prospects. Round Table104, 199–208. doi: 10.1080/00358533.2015.1017252

9

Chand S. (2020). “Economic impacts and implications of climate change in the Pacific” in Climate change and impacts in the Pacific. ed. KumarL. (Springer in Cham, Switzerland: Springer International Publishing), 475–498.

10

Chen A. A. Stephens A. J. Koon Koon R. Ashtine M. Mohammed-Koon Koon K. (2020). Pathways to climate change mitigation and stable energy by 100% renewable for a small island: Jamaica as an example. Renew. Sust. Energy Rev.121:109671. doi: 10.1016/j.rser.2019.109671

11

Cyclone Winston 2016-Government of Fiji . (2016) Fiji post-disaster needs assessment: Tropical Cyclone Winston, February 20, 2016 (Report). Government of Fiji. Available at: https://www.preventionweb.net/publication/tropical-cyclone-winston-2016-fiji-post-disaster-needs-assessment

12

Dean M. R. U. (2022). The Fiji sugar industry: sustainability challenges and the way forward. Sugar Tech.24, 662–678. doi: 10.1007/s12355-022-01132-4,

13

Dhanaraj R. K. Maragatharajan M. Sureshkumar A. Balakannan S. P. (2025). On-device AI for climate-resilient farming with intelligent crop yield prediction using lightweight models on smart agricultural devices. Sci. Rep.15:31195. doi: 10.1038/s41598-025-16014-4,

14

FAO . (2020) Fiji Agriculture Census (59/2021) Fiji. Available online at: https://www.fao.org/fileadmin/templates/ess/ess_test_folder/World_Census_Agriculture/WCA_2020/WCA_2020_new_doc/FJI_REP1_ENG_2020.pdf (accessed March 18, 2023).

15

Febles N. Á. Félix G. F. (2020). “Hurricane María, agroecology, and climate change resiliency” in Climate justice and community renewal. eds. FeblesN. Á.FélixG. F. (Abingdon, United Kingdom: Routledge), 131–146.

16

Fiji Government . (2016). Fiji: post-disaster needs assessment. Available online at: http://fijiclimatechangeportal.gov.fj/wp-content/uploads/2021/12/TC-Winston-PDNA-2016.pdf (accessed April 7, 2022).

17

Fiji Government . 2021. Climate Change Act 2021: An Act to establish a comprehensive response to climate change, to provide for the regulation and governance of the national response to climate change, to introduce a system for the measurement, reporting and verification of greenhouse gas emissions and for related matters. Available online at: http://fijiclimatechangeportal.gov.fj/wp-content/uploads/2021/12/20210927_161640.pdf (accessed May 21, 2023).

18

Floering I. (2024). Cane sugar: three case studies. In GrahamE.FloeringI.The modern plantation in the third world, 150–198, Routledge, London

19

FSC . (2023). Fiji-Sugar-Corporation-Annual-Report. 18. Available online at: https://www.parliament.gov.fj/wp-content/uploads/2023/11/109-Fiji-Sugar-Corporation-Annual-Report-2023-5.pdf (accessed June 12, 2024).

20

FSC . (2024). Annual report. Parliamentary paper, 158/24. Available online at: https://www.sugarsoffiji.com/_files/ugd/660c5d_098a5b84911d466895c5ff8e95d9a70f.pdf (accessed August 8, 2024).

21

Galaitsi S. E. Corbin C. Cox S. A. Joseph G. McConney P. Cashman A. et al . (2024). Balancing climate resilience and adaptation for Caribbean Small Island developing states (SIDS): building institutional capacity. Integr. Environ. Assess. Manag.20, 1237–1255. doi: 10.1002/ieam.4860,

22

Gupta D. Singh G. Thakur N. Bhatia R. (2017). Evaluation of some novel insecticides, biopesticides and their combinations against peach leaf curl aphid, Brachycaudus helichrysi infesting nectarine. J. Environ. Biol.38, 1275–1280. doi: 10.22438/jeb/38/6/MRN-469

23

IPCC (2022) Climate Change 2022: impacts, adaptation and vulnerability. Available online at: https://www.ipcc.ch/report/ar6/wg2/ (accessed March 29, 2023).

24

Kemp-Benedict E. Drakes C. Canales N. (2020). A climate-economy policy model for Barbados. Economies8:16. doi: 10.3390/economies8010016

25

Khan S. Yun B.-W. (2025). Rooted in crisis, growing solutions: economic impacts and adaptive pathways for Fiji’s climate-threatened sugarcane industry. Front. Clim.7, 5–7. doi: 10.3389/fclim.2025.1690723

26

King N. (2016). Exploring female former sugar cane farmers' livelihood transition in St. Kitts and Nevis: a multiple case study. San Diego, California: Northcentral University. Available online at: https://www.proquest.com/docview/1836061499?pq-origsite=gscholar&fromopenview=true&sourcetype=Dissertations%20&%20Theses (accessed July 3, 2022).

27

Lalljee B. Velmurugan A. Singh A. K. (2018). “Chapter 14 - climate resilient and livelihood security – perspectives for Mauritius Island” in Biodiversity and climate change adaptation in Tropical Islands. eds. SivaperumanC.VelmuruganA.SinghA. K.JaisankarI. (Cambridge, Massachusetts: Academic Press), 403–431.

28

Linnenluecke M. K. Nucifora N. Thompson N. (2018). Implications of climate change for the sugarcane industry. WIREs Clim. Change9:e498. doi: 10.1002/wcc.498

29

Lowitt K. Hickey G. M. Saint Ville A. Raeburn K. Thompson-Colón T. Laszlo S. et al . (2015). Factors affecting the innovation potential of smallholder farmers in the Caribbean community. Reg. Environ. Change15, 1367–1377. doi: 10.1007/s10113-015-0805-2

30

Macmillan P. (2016). “St Kitts and Nevis” in The statesman’s yearbook: the politics, cultures and economies of the world 2017 (London, United Kingdom: Palgrave Macmillan), 1018–1020.

31

Marin F. R. Jones J. W. Singels A. Royce F. Assad E. D. Pellegrino G. Q. et al . (2013). Climate change impacts on sugarcane attainable yield in southern Brazil. Clim. Change117, 227–239. doi: 10.1007/s10584-012-0561-y

32

McMichael C. Yee M. Cornish G. Lutu A. McNamara K. E. (2025). Adaptive capacity in Pacific Islands: responding to coastal and climatic change in Nagigi village, Fiji. PLoS Clim.4:e0000504. doi: 10.1371/journal.pclm.0000504

33

Medina Hidalgo D. Mallette A. Nadir S. Kumar S. (2024). The future of the sugarcane industry in Fiji: climatic, non-climatic stressors, and opportunities for transformation. Front. Sustain. Food Syst.8, 6–10. doi: 10.3389/fsufs.2024.1358647

34

Medina Hidalgo D. Witten I. Nunn P. D. Burkhart S. Bogard J. R. Beazley H. et al . (2020). Sustaining healthy diets in times of change: linking climate hazards, food systems and nutrition security in rural communities of the Fiji Islands. Reg. Environ. Change20:73. doi: 10.1007/s10113-020-01653-2

35

Morton J. F. (2007). The impact of climate change on smallholder and subsistence agriculture. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci.104, 19680–19685. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0701855104,

36

Mycoo M. Wairiu M. Campbell D. Duvat V. Golbuu Y. Maharaj S. et al . (2022). Climate change 2022: impacts, adaptation and vulnerability. Cambridge, United Kingdom: Cambridge University Presshttps://research-repository.griffith.edu.au/items/50f50279d024-4231-8aa1-9306d568ab91.

37

Nand M. M. Bardsley D. K. Suh J. (2023). Addressing unavoidable climate change loss and damage: a case study from Fiji’s sugar industry. Clim. Change176:21. doi: 10.1007/s10584-023-03482-8

38

Narayan P. K. Prasad B. C. (2005). Economic importance of the sugar industry for Fiji. Rev. Urban Reg. Dev. Stud.17, 104–114. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-940X.2005.00097.x

39

NU. CEPAL (2019) Preliminary Overview of the Economies of Latin America and the Caribbean 2018 (9789211220063). Available online at: https://www.cepal.org/en/publications/44327-preliminary-overview-economies-latin-america-and-caribbean-2018 (accessed April 16, 2023).

40

Nurse L. A. Mclean R. F. Agard J. Briguglio L. P. Duvat-Magnan V. Pelesikoti N. et al . (2014). Small islands. In BarrosV.RFieldC. B.DokkenD. J.MastrandreaM. D.MachK. J.BilirT. E.et al. (Eds.), Climate change 2014: Impacts, adaptation, and vulnerability. Part B: Regional aspects. Contribution of working group II to the fifth assessment report of the intergovernmental panel on climate change (1613–1654). Cambridge, United Kingdom, and New York, NY, USA: Cambridge University Press. Available online at: https://hal.science/hal-01090732

41

Olkeba A. Alemu G. Belay S. Jember M. Meseret H. (2024). African rural transformation and livelihood system: experience from Mauritius. Cogent Food Agric.10:2300559. doi: 10.1080/23311932.2023.2300559

42

Page M. J. McKenzie J. E. Bossuyt P. M. Boutron I. Hoffmann T. C. Mulrow C. D. et al . (2021). The PRISMA 2020 statement: an updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ372:n71. doi: 10.1136/bmj.n71,

43

Pandey V. Misra A. K. Yadav S. B. (2019). “Impact of El-Nino and La-Nina on Indian climate and crop production” in Climate change and agriculture in India: impact and adaptation. ed. Sheraz MahdiS. (Cham, Switzerland: Springer International Publishing), 11–20.

44

Pasch R. J. Penny A. B. Berg R. (2018). Tropical Cyclone Report: Hurricane Maria (AL152017), 16–30 September 2017. National Hurricane Center. Available at: https://www.nhc.noaa.gov/data/tcr/AL152017_Maria.pdfHurricane

45

Pathak S. K. Singh P. Singh M. M. Sharma B. L. (2019). Impact of temperature and humidity on sugar recovery in Uttar Pradesh. Sugar Tech.21, 176–181. doi: 10.1007/s12355-018-0639-6

46

Paulik R. Williams S. Funaki M. Turner R. (2025). Wind damage dataset for buildings from 2016 tropical cyclone Winston in Fiji. Data Brief60:111463. doi: 10.1016/j.dib.2025.111463,

47

Pipitpukdee S. Attavanich W. Bejranonda S. (2020). Climate change impacts on sugarcane production in Thailand. Atmosphere11:408. doi: 10.3390/atmos11040408

48

Popay J. Roberts H. Sowden A. Petticrew M. Arai L. Rodgers M. et al . (2006). Guidance on the conduct of narrative synthesis in systematic reviews. A product from the ESRC methods programme1:b92. doi: 10.13140/2.1.1018.4643

49

Prakash R. Nakamura N. (2024). Sugarcane farmers’ perceptions of climate change and their “adaptation” methods in Fiji: adaptation for the industry or for their livelihood?Clim. Dev.16, 665–672. doi: 10.1080/17565529.2023.2295267

50

SCGC . (2020). Sugrcane growers council annual report 2020. Fiji: Sugarcane Growers Council. Available online at: https://www.parliament.gov.fj/wp-content/uploads/2022/09/Sugar-Cane-Growers-Council-Annual-Report-2020.pdf (accessed May 9, 2023).

51

Senapati A. K. (2020). Insuring against climatic shocks: evidence on farm households’ willingness to pay for rainfall insurance product in rural India. Int. J. Disaster Risk Reduct.42:101351. doi: 10.1016/j.ijdrr.2019.101351

52

Shiiba N. Singh P. Charan D. Raj K. Stuart J. Pratap A. et al . (2023). Climate change and coastal resiliency of Suva, Fiji: a holistic approach for measuring climate risk using the climate and ocean risk vulnerability index (CORVI). Mitig. Adapt. Strateg. Glob. Change28:9. doi: 10.1007/s11027-022-10043-4,

53

Shukla S. K. Sharma L. Jaiswal V. P. Dwivedi A. P. Yadav S. K. Pathak A. D. (2022). Diversification options in sugarcane-based cropping Systems for Doubling Farmers’ income in subtropical India. Sugar Tech.24, 1212–1229. doi: 10.1007/s12355-022-01127-1,

54

Singh R. Bindal S. Gupta A. K. Kumari M. (2022). “Drought frequency assessment and implications of climate change for Maharashtra, India” in Climate change and environmental impacts: past, present and future perspective. eds. PhartiyalB.MohanR.ChakrabortyS.DuttaV.GuptaA. K. (Cham, Switzerland: Springer International Publishing), 369–381.

55

Sulaiman A. A. Arsyad M. Rahmatullah R. A. Ridwan M. (2023). Identifying institutions and strategic programs to increase sugarcane production in Southeast Sulawesi, Indonesia [institutions role; ISM; strategic program; sugarcane]. Caraka Tani J. Sustain. Agric.38:15. doi: 10.20961/carakatani.v38i1.69869

56

Sultan R. (2021). “Economic impacts of climate change on agriculture: insights from the Small Island economy of Mauritius” in Small Island developing states: vulnerability and resilience under climate change. eds. MoncadaS.BriguglioL.BambrickH.KelmanI.IornsC.NurseL. (Cham, Switzerland: Springer International Publishing), 137–158.

57

Teixeira A. d. C. Leivas J. F. Ronquim C. C. Victoria D. d. C. (2016). Sugarcane water productivity assessments in the São Paulo state, Brazil. Int. J. Remote Sens. Appl.6, 84–95. doi: 10.14355/ijrsa.2016.06.009

58

UN ESCAP (2015) El Niño 2015/2016 impact outlook and policy implications (Bangkok, Thailand:United Nations Economic and Social Commission for Asia and the Pacific (UN ESCAP)).

59

UNCTAD . (2017). Economic Development in Africa Report 2017: Tourism for Transformative and Inclusive Growth. Available online at: https://unctad.org/publication/economic-development-africa-report-2017 (accessed June 27, 2022).

60

UNDP . (2018). From early recovery to long-term resilience in the Caribbean hurricanes Irma and Maria: One year on. UNDP Summary Report. Available online at: https://www.undp.org/sites/g/files/zskgke326/files/migration/latinamerica/UNDP-RBLAC-HurricanesIrmaMariaBB.pdf

61

Waclawovsky A. J. Sato P. M. Lembke C. G. Moore P. H. Souza G. M. (2010). Sugarcane for bioenergy production: an assessment of yield and regulation of sucrose content. Plant Biotechnol. J.8, 263–276. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-7652.2009.00491.x,

62

Wadghane R. (2022). Sustainability management status of agro-ecosystems: a case study of sugarcane farmers in Shevgaon and Paithan (sub-districts) of Maharashtra, India. Agric. Res.11, 737–746. doi: 10.1007/s40003-022-00617-8

63

Wadghane R. H. Madguni O. (2023). Agriculture water poverty status of sugarcane cultivation along canals of Jayakwadi dam, Maharashtra, India. Smart Agric. Technol.6:100369. doi: 10.1016/j.atech.2023.100369

64

Wadghane R. H. Madguni O. Baisakhi B. (2025). Unlocking sustainability potential: a SAFA framework analysis of sugarcane agriculture in Marathwada, Maharashtra, India. Sustain. Futures10:101118. doi: 10.1016/j.sftr.2025.101118

65

World Bank Group . (2022). Climate and development: an agenda for action. Available online at: https://www.worldbank.org/en/topic/climatechange/publication/climate-and-development-an-agenda-for-action (accessed August 14, 2023).

66

Zhao D. Li Y.-R. (2015). Climate change and sugarcane production: potential impact and mitigation strategies. Int. J. Agron.2015:547386. doi: 10.1155/2015/547386

Summary

Keywords

agricultural policy, climate adaptation, smallholder farmers, socio-ecological systems, sugarcane, systemic resilience

Citation

Khan S and Yun B-W (2026) From vulnerability to viability: integrating global evidence and Fijian insights for sugarcane resilience in SIDS. Front. Sustain. Food Syst. 10:1701721. doi: 10.3389/fsufs.2026.1701721

Received

09 September 2025

Revised

03 December 2025

Accepted

02 January 2026

Published

29 January 2026

Volume

10 - 2026

Edited by

Amitava Rakshit, Banaras Hindu University, India

Reviewed by

Vijay Singh Meena, ICAR - Mahatma Gandhi Integrated Farming Research Institute, India

Rahul Wadghane, Symbiosis International University Symbiosis Institute of Operations Management, India

Updates

Copyright

© 2026 Khan and Yun.

This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Byung-Wook Yun, bwyun@knu.ac.kr

Disclaimer

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.