Abstract

At present, an understanding of the teaching practices at university and the opinion of students about these practices is limited, at least in certain knowledge areas. Given this diagnosis and in the context of Social Sciences Didactics, we consider it important to analyze teaching practices and how they impact future teachers. Consequently, concerned about the quality of training offered to students, this study aims to know their opinion about which teaching practices they consider most appropriate to train in Social Sciences Didactics, once they finish the subjects related to this area. To this end, a non-experimental quantitative design has been used, involving collecting information through a questionnaire completed by 875 students from seven Spanish universities studying for the Degree in Primary Education. The data was analyzed from a triple perspective, an analysis of the descriptive statistics of the items contemplated in this research, the existing correlations between them, and a statistical analysis based on the gender variable. The results show that the treatment of controversial issues and the didactic outings outside the university classroom are the strategies most valued by the students in teaching specific content of the subject Social Sciences Didactics. The results also show significant differences in the responses to each item depending on the gender variable. We conclude that students widely value university teaching practices related to implementing active methodologies, analyzing current social and environmental issues, and collaborative work dynamics. Likewise, it is observed that women have, on the whole, a better opinion than men regarding these types of methodologies and strategies.

1 Introduction

The precepts governing the teaching of social sciences are currently based on the construct of democratic and critical citizenship (Gómez et al., 2021), capable of interpreting its environment, as well as intervening in it to transform it. This teaching should favor the consolidation of a complete vision of the world, where the totality of geographical spaces, existing historical and social events are taken into account while offering a local and global vision of problems (Pagés, 2019).

Given the importance of the teaching of Social Sciences in a world full of changes and uncertainties (Pérez, 2019), it is necessary to ask ourselves about what type of initial training future teachers will require to guide students in the process of building their social thinking. Along these lines, it is also worth questioning whether education professionals are trained to teach Social Sciences from a critical and emancipatory perspective and whether they are adequately trained to do so in university classrooms. Therefore, we consider that understanding students’ opinions about their initial training is key to knowing if this training has been significant enough to enable them to incorporate modifications in the teaching of social content in their areas of teaching activity.

Undoubtedly, the initial training that future teachers receive at university is transcendental to promote epistemological changes in their conceptions about the teaching of Social Sciences and its purposes (González and Fuentes, 2011). Similarly, authors such as Estepa (2017) justify the need for quality training, based on the idea that a teacher, when faced with teaching for the first time, usually bases their teaching methods on models already lived or experienced, as well as on their experiences as a student. This may imply a reproduction of previously perceived models that, in general terms, tend to be attached to traditional models (Sánchez Fuster, 2017; Souto and García-Monteagudo, 2019). Since the pedagogical actions of teachers in training will emerge from the teaching practices in the university classroom, offering adequate initial training should be the primary motivation for improving teaching practice in classrooms, ensuring a break from traditional school routines (Parra et al., 2019) and the social representations that students have about of Social Sciences (Souto and García-Monteagudo, 2016). Thus, in order to meet the indicated purposes, in the context of Higher Education, we must begin with methodological approaches that affect the problematization of social content, the connection with controversial issues, past and present (Santisteban, 2019a), and that allows students to play an active role in their own learning process.

In this context, almost 2 decades ago, Cuesta (2003) claimed the importance of training future teachers in critical didactics, which would involve, among other aspects, problematizing the present, thinking historically, learning through dialogue, and challenging pedagogical and professional codes to question the disciplinary bases of school knowledge that can hinder innovation and change. Consequently, at the university level, these training needs should focus on providing future professionals with an active attitude in their profession while equipping them with relevant skills and knowledge that could lead them to improve their educational practices (Iranzo, 2018).

Therefore, we understand the guidelines that must be adhered to train future teachers in teaching skills that allow them to develop the social thinking of their students for the purposes mentioned above, based on the critical understanding and interpretation of reality and a commitment to it. However, little is known as to whether the teaching practices at the university level in the subject of Social Sciences Didactics contribute to this and adequately impact the training of students (Pagès and Santisteban, 2014). In other words, there is little understanding of what these practices look like in a real classroom (Santisteban, 2019a), despite the importance of these processes for the improvement of teacher training.

Among the few works that have approached this reality, we highlight those of Moril (2011), Aranda and López (2017) or Guerrero et al. (2020), which have highlighted some aspects that deserve our attention, such as the continuity of excessively expository practices in university contexts, the lack of connection between theory and practice, or the need to reinforce the relations between university and school further. Despite being an unexplored and even ignored line of research (Cochran-Smith, 2005), at least in the Spanish university environment and, in particular, in the area of Social Science Didactics, it is crucial to continue analyzing the initial training offered to future teachers in this subject area, since reflection on the formative impact of the university teacher’s practice on trainee teachers (Kitchen and Stevens, 2008) can lead to an understanding of what is needed to enhance the professional development of future educators. Likewise, we consider it essential to address one of the main challenges posed to the didactics of this specific subject, such as preparing teachers who have the task of educating the future citizens of a complex society, which presents us with numerous challenges (Montero et al., 2017).

Based on our studies on university training practices, we can deduce that initial teacher training hardly favors methodological strategies that thoroughly train students and, in particular, involve questioning or asking questions. Methodological practices tend to be not very reflective, clashing head-on with the reflective nature of social content itself. In this context, regarding the training given in university classrooms, some authors point out that among teachers’ concerns, attracting the student body’s attention so that they feel attracted to what they are studying is not a priority (Esteban, 2019). An approach that has received the reinforcement of other authors when defining university didactics as traditional teaching that is excessively masterful and focused on theory, which hardly prepares future teachers for their professional practice (Vaillant and Marcelo, 2015).

Delving further into the issue of teacher training, knowledge of how students in initial training conceive the educational practices of teachers is essential to transform the teaching landscape from within. In fact, the process of transformation of educational practices in Social Sciences falls on the initial training of teachers, since only from this perspective can we train students to subsequently implement active learning methodologies in the classroom that optimize the teaching of historical, geographical, and social content, endowing them with a critical and transformative sense.

Faced with this situation, we value the need to train university students from the improvement of the teaching-learning process in Higher Education classrooms themselves, providing them with the necessary theoretical and practical knowledge that allows them to determine what content to teach, why they should be taught, how to teach them, and how and when to evaluate them (Benejam, 1999). For this reason, we consider that it is currently necessary to reflect on and investigate the teaching practices of university professors who teach subjects in Social Science Didactics. Not surprisingly, the main task of any specific didactics must reside, from a scientific point of view, the study of the existing relationships between the teacher, the students, and the transfer of knowledge in an educational context. Thus, given the reality that welcomes us, we believe it is essential to focus our attention on the university classroom and analyze and innovate to improve reflection-in-action and reflection-on-action, as pertains to teaching practice (Escribano, 2019). These purposes link with the reflective teaching practice that Schön (1992) began.

To confirm this better understanding of the act of teaching, it is appropriate for teachers to explore, together with their students, the representations that both have about what happens in class (Monereo et al., 2013). This research framework must be accompanied by different training strategies such as team meetings to manage the subject taught, teaching circles between teachers, and, sometimes, with students, in which the teaching and learning processes are analyzed for their improvement, based on self-training strategies. Furthermore, Monereo (2013) emphasizes this understanding by proposing an integrative approach to know the impact of teaching practice based on four parameters: the university teacher, university students, the institution, and the training process of the teacher.

In short, given the importance of initial training to transform praxis in educational contexts and the few studies carried out within the framework of Social Science Didactics at the university level, we wish to study, in-depth, which resources and methodologies are the most valued by preservice teachers in order to develop their skills and knowledge, once they have completed the subjects in this area. In this study, we also analyze whether there are gender differences in the results obtained. This analysis based on the gender variable is justified by the existence of extensive international studies that confirm these differences, for example, regarding the digital competences of future teachers (Lucas et al., 2021), their attitudes towards the new technologies (Ottenbreit-Leftwich et al., 2015; Tondeur et al., 2016), or perceptions in relation to the Technological Pedagogical Content Knowledge (TPACK) (Luik et al., 2018). However, there are also similar studies that do not find these differences (Sang et al., 2010; Papadakis, 2018). Consequently, in this research we wanted to determine if there are significant differences between men and women in relation to opinions about resources and methods for training in Social Science Didactics.

We are convinced that the optimization of training practices in Higher Education must occur because they are spaces for research and reflection for those who intervene in this training context. In this way, the results of this study will make it possible to identify strengths and weaknesses and integrate conclusive improvements in university teaching activities.

2 Materials and Methods

2.1 Objectives

The general objective (GO) of this research is to analyze the students’ opinions, once their training has concluded, of the Degree in Primary Education on the teaching practices at the university level in the area of Social Sciences Didactics. The following specific objectives (SO) are broken down from the previously mentioned GO:

1. Analyze which didactic resources they consider most appropriate to address the contents of the subjects in the area of Social Sciences Didactics.

2. Analyze which didactic methods they consider most appropriate to address the contents of the subjects in the area of Social Sciences Didactics.

3. Analyze the gender variable as a determining factor of students’ conceptions of teaching resources and methods.

2.2 Research Design

A non-experimental quantitative design was used to collect information through a questionnaire with a Likert scale (1–5). This type of design was chosen because it can respond to problems in descriptive terms and concerning the variables when the information is collected systematically, guaranteeing the rigor of the data obtained (Hernández and Maquilón, 2010).

2.3 Participants

Participants comprised 875 (n = 875) students of the Degree in Primary Education from seven different Spanish universities: Almería, Complutense de Madrid, Cordoba, Extremadura, Malaga, Murcia, and the Public University of Navarra. The study sample was made up of, in terms of gender, 281 men (32.1%) and 594 women (67.9%). The sample has been selected following non-probabilistic convenience sampling techniques since the criteria of accessibility to the subjects and suitability for the research were met (McMillan and Schumacher, 2005).

2.4 Instrument

Information was collected based on the following research instrument: “Questionnaire for the knowledge and evaluation of university educational practices of the teaching staff of Social Sciences Didactics.” The questionnaire has been validated by four experts from Social Sciences Didactics from various Spanish universities. This validation was carried out through a questionnaire wherein experts assessed aspects such as its sufficiency, clarity, and relevance with an estimation scale of 1–4 (Table 1). The results were satisfactory in terms of its presentation (3.75 on average), formal aspects (3.79 on average), content (3.77 on average), achievement of objectives (3.77 on average), and in its global character (3.83 on average). Following an initial validation phase, all the improvements proposed by the experts have been taken into account and integrated into the instrument before generating and applying its final version.

TABLE 1

| Parts of the validation questionnaire | Number of items | Average |

|---|---|---|

| Assessment of the presentation of the students | 7 | 3.75 |

| Assessment of the formal aspects of the questionnaire | 6 | 3.79 |

| Assessment of the contents of the test | 4 | 3.77 |

| Assessment of the achievement of research objectives through the questionnaire | 10 | 3.77 |

| Global assessment of the questionnaire | 3 | 3.83 |

Averages of the items of the validation questionnaire.

This research is based on the information corresponding to Block IV of the questionnaire dedicated, specifically, to the “Analysis of teaching educational practice: methodology, strategies, and materials in the classroom.” The analyzed items from Block IV correspond to Section IV.2 of the questionnaire, entitled: Opinions about materials and resources that could be used to teach the subject (Table 2), and Section IV.3, entitled: Opinions on the most appropriate didactic methods to impart knowledge of Social Sciences (Table 3). The participating students responded to the items listed in the sections, evaluating their responses between 1 (Strongly disagree) and 5 (Strongly agree).

TABLE 2

| Item 1 | Notes/subject manual/presentations |

| Item 2 | ICT resources (websites, applications, videogames …) |

| Item 3 | Relevant social problems or current social issues |

| Item 4 | Oral sources (interviews with grandparents, relatives, neighbors …) |

| Item 5 | Cultural heritage (tangible or intangible) |

| Item 6 | Audiovisual media (cinema, music, posters …) |

| Item 7 | Written media (literature, press, letters …) |

| Item 8 | Participation of social groups, associations, communities, sectors of the population |

| Item 9 | Participation of a large number of education professionals (active teachers, former students …) |

| Item 10 | Historical, geographical, artistic documentary sources, etc. |

Items in Block IV.2 on materials and resources.

TABLE 3

| Item 1 | Humanizing the teaching of social sciences through people and their actions |

| Item 2 | Carrying out debates about the contents |

| Item 3 | Outings to museums and historical places, fieldwork, etc. |

| Item 4 | Empathy exercises, simulation, dramatization, etc. |

| Item 5 | Cooperative group actions of students that enhance their intervention |

| Item 6 | Flipped Classroom |

| Item 7 | Gamification - Game Based Learning |

| Item 8 | Learning - Service |

| Item 9 | Otherness (condition of being another) |

| Item 10 | Literacy work or critical literacy in front of information or images |

Items in Block IV.3 on teaching methods.

The choice of these two sections for analysis is justified because they are considered the best elements to know the opinion of trainee teachers about the teaching actions and the interventions of their teachers during the teaching of the subjects. Its analysis offers valuable information about these students’ opinions about the most appropriate resources and methods to teach Social Sciences Didactics content.

To estimate the reliability of the sections of Block IV as analyzed in this study (Sections IV.2. and IV.3.), we used the internal consistency method based on Cronbach’s Alpha, which allows us to estimate the reliability of a measurement instrument composed of a set of Likert-type items, which we hope measure the same theoretical dimension (the same construct). In this way, the items are summable into a single score that measures a trait that is important in the theoretical construction of the instrument. The scale’s reliability must always be obtained with the data from each sample to guarantee the reliable measurement of the construct in the specific research sample. In the case of Block IV, in sections IV.2 and IV.3, we obtain a Cronbach’s Alpha index of 0.98, which is considered excellent (α > 0.9) (Frías-Navarro, 2020).

2.5 Procedure and Data Analysis

We contacted teachers from the Social Sciences Didactics area of different Spanish universities that taught in the Degree in Primary Education to collect the information. The research objectives were then explained, and they were invited to collaborate voluntarily with this study. Likewise, they were provided with the web link to the questionnaire used to collect information. University teachers from different Spanish universities who agreed to participate provided the questionnaire to teachers in initial training from May 2020 to July 2021, once the subjects they taught had been completed. In this way, the data set collected has been produced in the context of the global pandemic due to COVID-19. At all times, the participating students were informed of both the research objectives and the anonymity of their responses.

Once the information gathering process has been completed, the data analysis was carried out in three phases: a) analysis of the descriptive statistics of Sections IV.2. and IV.3. of Block IV of the questionnaire, b) analysis of the correlations between the items and c) statistical analysis based on the gender variable. Data was entered into the software Statistical Package for Social Sciences (SPSS) employing different techniques for quantitative analysis. First, a verification of the normality of the data was carried out with the non-parametric Kolmogorov-Smirnov test, due to a sample size greater than 50 participants (n = 875), setting a significance level of 5% (p = 0.05). In non-parametric tests, the distribution of the data is not known in advance and is not subject to any probability distribution or a certain sample size, functioning correctly when the skewness of the data or its distribution does not approach a normal distribution. Next, due to the result of normality of the data, the application of a non-parametric test is required to know the adequate coefficient for the correlation analysis, performing the Spearman test.

3 Results

3.1 Descriptive Analysis of the Items

3.1.1 Results on Teaching Resources

As can be seen in Figure 1, the item that has received the highest score from the participants in the survey is the one related to relevant social problems or current social issues (Item 3), given that 61.1% state that they are “strongly agree” with the inclusion of these topics in the classroom to address the contents of Social Sciences Didactics of Social subjects. Secondly, Item 6, related to audiovisual media (cinema, music, posters …), also received a very favorable opinion from 59.2% of those surveyed. Third, Item 5, linked to cultural heritage (tangible or intangible), is considered by 57.4% of teachers in initial training as a highly relevant resource for the development of the subject. These three resources are preferred by students to be used in the teaching-learning processes of the subjects Didactics of Social Sciences in the Degree in Primary Education.

FIGURE 1

Regarding the items that, despite receiving a favorable evaluation, have done so to a lesser degree, Item 9 relating to the participation of a greater number of education professionals (active teachers, former students …) stands out as it was considered as very relevant by 46.1% of the students. Next, the use of written media (literature, press, letters …) in the classroom was deemed to be very relevant by 45% of the participants (Item 7), receiving an assessment of 36.8% within the category “neither of agree nor disagree,” which reflects a fairly neutral opinion regarding the use of this resource by students. Finally, Item 1, concerning notes/subject manual/presentations, has been the one that was considered the least relevant, attaining the lowest percentage of 42.2%. It should also be noted that it has received the highest percentage of evaluations in disagreement with its use, that is, 6.7% in the evaluations that show positions that disagree somewhat or strongly disagree with its use.

3.1.2 Results on Teaching Methods

Concerning the section on didactic methods, Figure 2 shows the item that has had the highest valuation by the participants in the survey is outings to museums and historical places, fieldwork, etc. (Item 3), as 67.4% “strongly agree” with the use of this strategy. Secondly, Item 5, cooperative group actions of students that enhance their intervention, receives a very favorable opinion from 64.2% of those surveyed. Third, Item 7, linked to gamification and game-based learning, is considered by 62% of the teachers in training as a highly relevant resource in teaching subjects. Therefore, the students, once they take the subjects in the area of knowledge, consider that the most relevant methods for teaching the contents of Didactics of Social Sciences in Higher Education should be based on experiences implemented outside the classroom, cooperative and group dynamics with participation active on the part of the students and in a teaching action that is based on the majority use of gamified activities.

FIGURE 2

Regarding the items that have received a favorable assessment, although to a lesser extent, work on literacy or critical literacy versus information or images (Item 10) was considered highly relevant by 40.7% of the students; the use of the Flipped Classroom method (Item 6) was considered by 38.7% of the participants as very relevant, a long way from the levels observed in other innovative teaching methods, such as gamification or dramatization. Finally, otherness (condition of being other) was hardly considered by 33.6% of the participants as very relevant (Item 9). While, in this case, 31.8% of the sample selected “neither agree nor disagree,” this, in our opinion, is a relatively high percentage that could reflect the degree of ignorance that the participants have about this method or its meaning.

3.2 Analysis of Correlation of the Items

In order to observe possible relationships between the established variables, the correlations between the items have been examined, identifying variables that did not correlate well with any other, that is, with correlation coefficients less than 0.3; or variables that correlate well with others, that is, that have a coefficient lower than 0.9, thus omitting the almost perfect correlation.

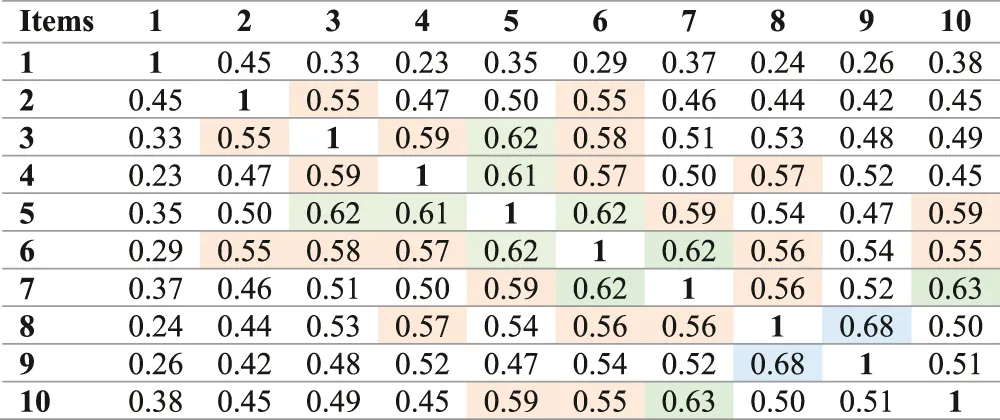

3.2.1 Correlations of the Items Related to Teaching Resources

Concerning the didactic resources, Table 4 shows the best correlation (0.68) occurring between Items 8 and 9, referring to the participation of social groups, associations, communities, sectors of the population and the participation of a greater number of education professionals (active teachers, former students …) in the classroom. Likewise, we highlight the correlation (0.63) between Items 7 and 10, related to the use in class of, on the one hand, Written media (literature, press, letters …) and, on the other hand, Historical and geographical documentary sources, artistic, etc. Finally, there is a striking correlation of 0.62, between variables 6 and 7, linked to the use of audiovisual media (film, music, posters …) and written media (literature, press, letters …); between variables 6 and 5 related to the use of cultural heritage and audiovisual media and finally, between variables 5 and 3 linked to the use of relevant social problems and cultural heritage.

TABLE 4

Spearman’s correlations of the items in Block IV.2. (didactic resources).

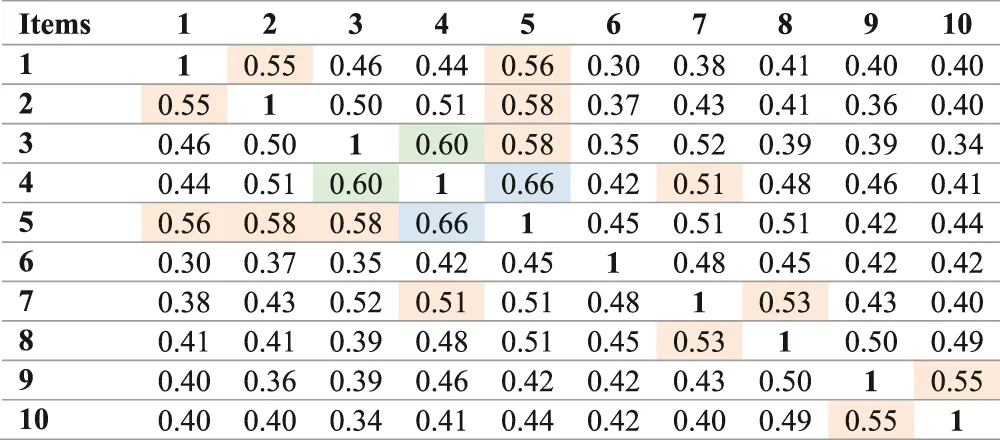

3.2.2 Correlations of the Items Related to Didactic Methods

Likewise, the correlations between the items in Block IV.3 concerning didactic methods (Table 5) have been examined, identifying the highest correlation (0.66) between Items 4 and 5, referring to the carrying out exercises in empathy, simulation, dramatization, etc. and the implementation of cooperative group actions for students that enhance their intervention in the classroom. Likewise, we can highlight the correlation (0.60) between Items 3 and 4, linked to the incorporation into the classroom of, on the one hand, outings to museums and historical places, fieldwork, etc.; as well as, on the other hand, exercises of empathy, simulation, dramatization, etc.

TABLE 5

Spearman’s correlations of the items in Block IV.3. (teaching methods).

3.3 Analysis of One Factor: Gender

3.3.1 The Gender Variable in Teaching Resources

Considering the gender variable, an analysis of the items based on this factor has been developed. In the case of didactic resources, a difference in responses is observed in three items: relevant social problems, oral sources, and, finally, audiovisual media (Table 6). What is observed are divergent response trends in terms of gender, with the data denoting diversity of opinions among the participants in the sample, depending on whether they are men or women. In this sense, although, in general terms, women regularly rate the set of resources offered as a response in the questionnaire better than men, it is observed how this opinion is more disparate in some specific items (shown in bold).

TABLE 6

| Lower limit | Upper limit | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Notes/subject manual/presentations | M | 3.99 | 4.20 |

| W | 4.09 | 4.24 | |

| Total | 4.08 | 4.20 | |

| ICT resources (websites, applications, videogames, virtual and augmented reality …) | M | 4.18 | 4.39 |

| W | 4.37 | 4.50 | |

| Total | 4.33 | 4.45 | |

| Relevant social problems or current social issues | M | 4.19 | 4.40 |

| W | 4.48 | 4.60 | |

| Total | 4.41 | 4.52 | |

| Oral sources (interviews with grandparents, relatives, neighbors …) | M | 3.97 | 4.22 |

| W | 4.28 | 4.42 | |

| Total | 4.21 | 4.33 | |

| Cultural heritage (tangible or intangible) | M | 4.22 | 4.43 |

| W | 4.40 | 4.52 | |

| Total | 4.36 | 4.47 | |

| Audiovisual media (cinema, music, posters …) | M | 4.19 | 4.40 |

| W | 4.42 | 4.55 | |

| Total | 4.37 | 4.48 | |

| Written media (literature, press, letters …) | M | 4.01 | 4.23 |

| W | 4.19 | 4.33 | |

| Total | 4.16 | 4.27 | |

| Participation of social groups, associations, communities, sectors of the population | M | 3.98 | 4.22 |

| W | 4.21 | 4.36 | |

| Total | 4.16 | 4.29 | |

| Participation of a large number of education professionals (active teachers, former students …) | M | 3.92 | 4.16 |

| W | 4.13 | 4.29 | |

| Total | 4.09 | 4.22 | |

| Historical, geographical, artistic documentary sources, etc. | M | 4.22 | 4.40 |

| W | 4.35 | 4.47 | |

| Total | 4.33 | 4.43 |

Descriptive analysis of the teaching resources, according to gender.

As shown in Table 6, women value the item, relevant social problems in the classroom, better than men, although men give this resource the highest average rating of the set of resources offered in the list. A difference in opinion regarding the use of resources that is more clearly observed is the case of the use of oral sources, where women have a notably more favorable opinion than men. Not surprisingly, men give this resource the lowest average ratings.

3.3.2 The Gender Variable in Teaching Methods

On the other hand, taking into account the didactic methods based on the gender variable, a difference in responses is observed (Table 7), particularly in three items: empathy exercises, simulation, dramatization, etc.; flipped classroom and, finally, service-learning. As in the case of resources, what is observed are divergent response trends related to the variable, where the data denotes diversity of opinions among the participants in the sample.

TABLE 7

| Lower limit | Upper limit | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Humanize the teaching of Social Sciences through people and their actions | M | 4.32 | 4.48 |

| W | 4.41 | 4.53 | |

| Total | 4.40 | 4.50 | |

| Carrying out debates about the contents | M | 4.29 | 4.48 |

| W | 4.46 | 4.58 | |

| Total | 4.42 | 4.52 | |

| Outings to museums and historical places, fieldwork, etc. | M | 4.33 | 4.54 |

| W | 4.47 | 4.61 | |

| Total | 4.45 | 4.56 | |

| Empathy exercises, simulation, dramatization, etc. | M | 4.17 | 4.38 |

| W | 4.38 | 4.52 | |

| Total | 4.33 | 4.45 | |

| Cooperative group actions of students that enhance their intervention | M | 4.33 | 4.52 |

| W | 4.51 | 4.62 | |

| Total | 4.47 | 4.57 | |

| Flipped Classroom | M | 3.71 | 3.97 |

| W | 3.98 | 4.14 | |

| Total | 3.92 | 4.06 | |

| Gamification - Game-Based Learning | M | 4.25 | 4.46 |

| W | 4.41 | 4.55 | |

| Total | 4.38 | 4.50 | |

| Learning - Service | M | 4.05 | 4.26 |

| W | 4.26 | 4.41 | |

| Total | 4.22 | 4.34 | |

| Otherness (condition of being another) | M | 3.72 | 3.94 |

| W | 3.88 | 4.03 | |

| Total | 3.85 | 3.98 | |

| Literacy work or critical literacy in front of information or images | M | 3.90 | 4.11 |

| W | 4.07 | 4.22 | |

| Total | 4.04 | 4.16 |

Descriptive analysis of the teaching methods, according to gender.

Thus, following the pattern identified in the previous case, regarding resources, women regularly rate the set of didactic methods offered in response to the questionnaire higher than men. However, we can observe how this opinion is more disparate in the three items indicated, especially in the one related to flipped classroom, where there is more disparity of opinion. In fact, in the case of men, this teaching method is the one with the worst average score of the set of items (3.71), while in the case of women, it is the second item with the worst score (3.98), only surpassed by the appeal of otherness (3.88).

4 Discussion

We began this study reflecting on the transformations that the creation of the European Higher Education Area has brought in the university, an institution traditionally rooted in the knowledge that has recently become an establishment linked to social demand and labor (Colomo and Esteban, 2020). As the primary educational entity, the university has been transformed from a humanist idea to a pragmatic or progressive conception of university education due to the so-called Bologna Process. A changing drift regarding teachers’ teaching practices has led some authors to indicate that “it seems that it does not matter too much if things are done well or not, if we have scandalous teachers or scandalous teachers” (Esteban, 2019: 107). An assertion that should at least alert the university educational community in the face of the establishment of mechanisms that could, at least, address the issue to better approach a research space that, as a general rule, is neglected in most degrees or areas of knowledge, as occurs in Didactics of Social Sciences (Pagès and Santisteban, 2014).

For this reason, we consider that better knowledge of the university teaching practice enables a progressive adaptation of a professional action that must be constantly exposed to analysis, reflection, and improvement. There are specific problems with the teaching practices in Education degrees, particularly in subjects related to specific didactics, since we must “teach” how future teachers are to teach (Estepa, 2017). In other words, we must train future teachers in strategies that enable the boys and girls who will make up their students to acquire meaningful and practical learning in an increasingly complex and challenging world. As trainers of trainers, bestows upon our profession a weighty responsibility, forcing us to rethink our practices and assess how these can be adapted to the training needs of our students in initial training and the demands of the professional reality outside the university classroom.

In this sense, an analysis of the teaching practices in Higher Education, particularly in the Degrees in Early Childhood Education or Primary Education, shows mostly theoretical, magisterial, or traditional approaches (Vaillant and Marcelo, 2015). We observe a panorama that contradicts both the paradigms that the Bologna Plan seeks to install: the establishment of educational prerogatives based on pragmatic and utilitarian training and increased focus on the training needs of future teachers.

Faced with this situation, studies like the present one, aimed at self-investigating our teaching practices, are fundamental because they open the way to research within the intervention context itself (Tack and Vanderlinde, 2014), thus allowing us to rethink the contents to be taught and the way to teach them, bearing in mind specific purposes pertinent to a specific ideological dimension (Ritter, 2010). Knowing what we do and how we do it helps us to guide our professional practice and define what teaching profiles and identities we want to train and what obstacles we must overcome in our daily practice to achieve this (Izadinia, 2014).

The results obtained in this study show students’ demand for methods involving joint group actions, teaching practices outside the classroom, and the implementation of active learning methodologies, such as gamification. These results agree with those observed in other similar investigations, which show that future teachers consider the acquisition of knowledge more effective through concrete actions that involve them in their own learning, compared to educational processes aimed at cognitive development where teachers direct a teaching practice at students, with little involvement from the student themselves (Uibu et al., 2017). Similarly, other studies such as that by Álvarez (2017) delve into the opinion of university students regarding the teaching methods they receive, concluding that: “students demand a methodological change in which interaction is prioritized in the teaching-learning process” (Álvarez, 2017: 110).

The data obtained in this study reinforces these demands aimed at the implementation in the classroom of didactic actions that move us away from the unidirectional and expository flows of content transfer from the teacher to the student and bring us closer to interactions between the actors present in the classroom, starting from a controlled dialogue and teacher-oriented dialogic inquiry (De Longhi et al., 2012; Reisman, 2012; Gómez et al., 2021).

Returning to the objectives set at the outset of this research, we have analyzed which resources are the most valued by future teachers for training in Social Sciences Didactics in Higher Education. The results show that these correspond to the relevant social problems or current social issues, audiovisual media (cinema, music, posters …), and cultural heritage (tangible or intangible). These results on the use of audiovisual media agree with the study by Miralles et al. (2019), who show how future Spanish teachers have a more motivational perception about the use of mass media and ICT than future English teachers. Concerning the use of heritage elements, our results agree with some recent research (Chaparro et al., 2020; Gómez Carrasco et al., 2021), highlighting the relevance that future teachers give to this resource to teach historical content. Similarly, it should also be noted that the students call for treatment of current social issues in the teaching-learning processes as they consider the connection between social content and current problems necessary in order to make increasingly practical and allow students to understand, interpret, and propose solutions to these problems (Santisteban, 2019b). For decades, without doubt, if we want to educate in citizenship, develop critical thinking of our students and prepare them to face the problems of the present and the future (García, 2021), the problematization approach to social content, despite the difficulties that it may entail, has been one of the most necessary alternatives to the disciplinary curriculum and the dominant school culture.

It is worth noting at this point that a relatively large percentage of the opinions obtained concerning the item notes/subject manual/presentations, 42.2%, stated that they “strongly agreed” to its use. Despite being the least valued resource, attaining a lower frequency value of 5 (very favorable), the truth is that it is representative of a sector of students who demand this type of resources or materials, probably because they consider them to essential tools for understanding the contents of the subject they need to pass, given the traditional character of the assessment tests used in university contexts. Undoubtedly, alternative and innovative resources and methods cannot lead to a traditional assessment based on memorization tests. Therefore, we consider this percentage (42.2%) favorable to the use of notes, manuals, and presentations to indicate the continued use of these traditional teaching practices in university classrooms.

Regarding the didactic methods, included in the second objective of this research, the teachers in training believe that the most appropriate strategies for teaching social content within the framework of the subjects corresponding to the area of Didactics of Social Sciences are: outings to museums and historical places, fieldwork, etc.; cooperative group actions of students that enhance their intervention and finally, the use of gamification and game-based learning in the classroom. These methodological elements invite teachers to rethink teaching from a purely participatory aspect, typical of active learning methodologies. In this case, it is a demand that is a response to the reality of university classrooms, where, occasionally, excessively rigid and theoretical practices tend to survive, based on traditional methodological principles, such as the transmission of knowledge in a masterful way, with few interactive methods between the agents participating in the teaching action (Álvarez, 2017).

The implementation of active learning methodologies in the university classroom would entail real and significant learning in the students, which would surely provide them with greater security and teaching skills when applying these methodologies in their future teaching practice, thus satisfying the guidelines of the previously mentioned Bologna Plan, which establishes teaching based on the development of skills and competences by the students (Paricio et al., 2020).

The disinterest shown by the participants in teaching based on the flipped classroom model is quite remarkable as it is one of the pedagogical models that is revolutionizing the educational field and that has had great success in virtual teaching contexts that have been developed as a necessary response to the context of the health emergency caused by the COVID-19 pandemic. Despite the apparent success of this model, the truth is that the results achieved are linked to those provided by some research that, at the very least, highlights the disparity of opinions among students when evaluating this method (Sosa and Palau, 2018; García et al., 2019; Sosa et al., 2021), including evaluations regarding its usefulness, opinions which, on occasions, differ from each other. In any case, students’ preference for a stance towards learning through active and collaborative didactic strategies where the student body is the primary actor in the training action does seem conclusive.

Finally, the study shows us some differences in the participants’ responses depending on the gender variable, where it is observed that, in general terms, women regularly value the set of resources and teaching methods itemized in the questionnaire better than men. Recent studies focused on the perceptions of trainee teachers about the use of specific resources in the teaching of historical content, also indicated a more favorable opinion of women towards the use of innovative methodologies in the classroom and, more particularly, on the use of ICT and mass media (Cózar and Roblizo, 2014; Roblizo and Cózar, 2015; Gómez et al., 2020a). This trend has been observed in other studies that analyze the competencies that future teachers consider most important to be worked on in history classes (Gómez et al., 2020b). In this research the results show the unanimous preference for competences of a procedural and methodological nature, and a clear preference of women for second-order contents.

Likewise, concerning resources listed, men have positively valued the use of relevant social problems or current social issues, audiovisual media (cinema, music, posters …), and historical, geographical, and documentary sources. artistic, etc. (4.40), while women have given their highest ratings to the use of relevant social problems or current social issues (4.60). In this regard, it is interesting to indicate how, in terms of the most appropriate didactic methods for imparting the contents of the area of knowledge, men consider that the best alternative is outings to museums and historical places, fieldwork, etc. (4.54), while women give the highest rating to cooperative group actions of the students that enhance their intervention (4.62).

5 Conclusion

Considering the results achieved, we can pose some questions that might help understand the demands from the student body for changing university teaching practices: does the student body of the Degree in Primary Education view the university as mainly being progressive or pragmatic? Does the student body only demand a training course that educates them as effective and efficient professionals? (Colomo and Esteban, 2020). How do current students conceive the training they should receive at university? That is, according to their expectations, what should the university be like today? (Ema et al., 2013). Expanding our understanding could help us to adapt, in certain aspects, the training as a response to student needs, without losing sight of two essential elements such as the current demands posed by education in a postmodern context and the collusion with the construction of a university for the 21st century.

Consequently, we advocate a line of research that seeks more profound knowledge of the teaching actions of teachers and that, in short, is directed towards implementation of what is known as self-study with regards to the training practices of the teaching staff (Cole and Knowles, 1998; Bullough and Pinnegar, 2001; Loughran et al., 2004; Pinnegar and Hamilton, 2009; Pithouse et al., 2009; and Ovens and Fletcher, 2014). This application would allow a significant and broader discovery of professional practice, resulting in the construction of the teacher’s personal knowledge and the growth of the scientific community (Loughran, 2005).

In our opinion, this research contributes to a greater understanding of how the teaching practice of Social Sciences Didactics should be to improve teacher training and adapt it to the needs of students. This study therefore has several educational implications. The first of these is the importance of establishing university teaching practices that contemplate the implementation of methods and resources that involve actively students in their learning and that allow them to develop professional skills that can be transferred to their future teaching service. It is called for a greater use of motivating resources such as audiovisual media or patrimonial elements and of strategies based on group work, field trips and the treatment of controversial issues (Ortega-Sánchez and Pagès, 2017). In this sense, it is necessary to intervene in the initial training of teachers to achieve an education based on competencies and active learning methods, which promotes epistemological changes and develops professional teaching competencies (Miralles-Martínez et al., 2019). The second educational implication, directly related to the practice of university teachers in this area, involves reorienting teaching approaches towards student-focused approaches centered on students (Postareff et al., 2007, 2008). This type of approach contributes to developing students’ knowledge, self-regulation processes and generates the conceptual and epistemological changes in their conceptions and mental representations about Social Sciences. The implications and needs indicated here can be extended to teacher training in our country, but also to other nearby spatial contexts such as Portugal. In this regard, the work of Gomes (2020) has also manifested the importance of opting for a more practical teaching approach in the classroom that is more closely related to real life. The author also demands a useful teaching training that can be transferred to the future teaching service of students and a greater connection between what university teachers believe (or say) they do and what they actually do. Likewise, training plans are required that reinforce the professional competencies of future teachers with regards to what to teach and how to teach it, and that focus on the current purposes of the teaching of Social Sciences, emphasizing the training of critical, autonomous, reflective, and committed professionals capable of making decisions and creating learning situations that favor meaningful and lasting social knowledge in their students.

Ultimately, this study provides us with a better understanding of how, in the opinion of students, the teaching practices of those who teach Social Science Didactics in Spanish universities should be, in terms of teaching resources and methods. An improved teaching praxis of all teachers must be built on the collection and analysis of information, consider all points of view, and be jointly reflected. This research contributes to this knowledge from the students’ perspective once they have completed the subjects, thus having a global perspective of the contents, the methodology, and evaluation. We also consider that the research provides information about the sociology of the classroom, in this case from the gender variable that, as has been shown, shows divergent response trends that, at a given moment, can determine decision-making in a classroom by the teacher. Finally, aware of the limitations that this study may have, we consider it necessary in future research to expand the sample and the spectrum of participating universities to check whether the trends observed in this research are also replicated in other training contexts. Likewise, future research must also take into account the opinions of university teachers from two aspects; on the one hand, the methodologies and resources that they consider most appropriate for the teaching and learning process of Social Sciences Didactics; and, on the other hand, the methodologies and resources that they habitually use in their training practices. It is important to investigate these two aspects, because they do not always converge. Finally, the methodological design of this research and the instruments used to collect information have had a quantitative approach, so future research also require the implementation of a mixed research design, which includes techniques and instruments of a qualitative research approach, such as in-depth interviews or groups of discussion. The results obtained through this qualitative approach will allow us to complement the results presented in this study and delve into the research object from a more holistic perspective.

Statements

Data availability statement

The datasets generated during the current study are not publicly available because the identities of some participants are visible, undermining privacy protection. Nevertheless, the datasets generated are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request. Requests to access the datasets should be directed to María del Mar Felices, marfelices@ual.es, Álvaro Chaparro: alvarocs@ual.es.

Ethics statement

Ethical issues were carefully contemplated in this study. Participants were informed about the objectives and procedures of the study and how their rights were going to be protected. Participation in the research was voluntary and anonymous.

Author contributions

MF was the primary author of the manuscript. MF and AC conceived and designed the project of which this study is part. MF and AC wrote the first draft of the manuscript. MF and AC both contributed to revisions and read and approved the submitted manuscript.

Funding

This study is the result of the R + D + i research project: “The teaching and learning of historical skills at the baccalaureate level: a challenge to achieve critical and democratic citizenship” (PID2020-113453RB-I00), funded by MCIN/AEI/10.13039/501100011033. In addition, it is also the result of the Educational Innovation Project: “Research to Innovate: Professional Development for Teaching in Social Sciences Didactics” (PIE 19/021), funded by the University of Malaga; and the Teaching Innovation Group “Investigating Innovative University Teaching Practices in Social Sciences Didactics” (21_22_1_06C), funded by the University of Almería.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Supplementary material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/feduc.2021.803289/full#supplementary-material

References

1

Álvarez ÁlvarezC. (2017). ¿Es interactiva la enseñanza en la Educación Superior? La perspectiva del alumnado. Redu15 (2), 97–112. 10.4995/redu.2017.6075

2

ArandaA. M.LópezE. (2017). Logros, dificultades y retos de la docencia e investigación en Didáctica de las Ciencias Sociales. REIDICS, Revista de Investigación en Didáctica de las Ciencias Sociales1, 5–23. 10.17398/2531-0968.01.5

3

BenejamP. (1999). La formación psicopedagógica del profesorado de Didáctica de las Ciencias Sociales. Revista Interuniversitaria de Formación Del Profesorado34, 219–229. Available at: https://dialnet.unirioja.es/servlet/articulo?codigo=118016 (Accessed October 18, 2021).

4

BulloughR. V.PinnegarS. (2001). Guidelines for Quality in Autobiographical Forms of Self-Study Research. Educ. Res.30 (3), 13–21. 10.3102/0013189x030003013

5

ChaparroA.GómezC. J.FelicesM.Rodríguez-MedinaJ. (2020). “Opiniones sobre el uso de recursos para la enseñanza de la Historia. Un estudio exploratorio en la formación inicial del profesorado,” in Desafíos de investigación educativa durante la pandemia Covid-19. Editors AznarI.CáceresM. P.MarínJ. A.MorenoA. J. (Madrid: Dykinson), 279–290. Available at: https://dialnet.unirioja.es/servlet/articulo?codigo=7819384 (Accessed October 18, 2021).

6

Cochran-SmithM. (2005). Teacher Educators as Researchers: Multiple Perspectives. Teach. Teach. Edu.21, 219–225. 10.1016/j.tate.2004.12.003

7

ColeA. L.KnowlesJ. G. (1998). “The Self-Study of Teacher Education Practices and the Reform of Teacher Education,” in Reconceptualizing Teaching Practice: Self-Study in Teacher Education. Editor HamiltonM. L.(London: Falmer Press), 224–234.

8

Colomo MagañaE.Esteban BaraF. (2020). La Universidad Europea: entre Bolonia y la Agenda 2020. Reec36 (julio-diciembre), 54–73. 10.5944/reec.36.2020.26179

9

CózarR.RoblizoM. (2014). La competencia digital en la formación de los futuros maestros. Percepciones de los alumnos de los Grados de Maestros de la Facultad de Educación de Albacete. RELATEC. Revista Latinoamérica de Tecnología Educativa13 (2), 119–133. 10.17398/1695-288X.13.2.119

10

CuestaR. (2003). Campo profesional, formación del profesorado y apuntes de didáctica crítica para tiempos de desolación. Didáctica de las Ciencias Experimentales y Sociales17, 3–23. Available at: https://roderic.uv.es/handle/10550/29818 (Accessed October 18, 2021).

11

EmaJ. E.García MolinaJ.ArribasS.CanoG. (2013). What Is Going on (With Us) at university?Athenead13 (1), 3–6. Available at: https://raco.cat/index.php/Athenea/article/view/291630/380116 (Accessed October 18, 2021). 10.5565/rev/athenead/v13n1.1173

12

EscribanoC. (2019). Enseñar a enseñar el tiempo histórico. ¿Qué saben y qué aprenden los futuros docentes de Secundaria? Tesis doctoral. Logroño: Universidad Internacional de La Rioja.

13

EstebanF. (2019). La universidad light. Un análisis de nuestra formación universitaria. Barcelona: Paidós.

14

EstepaJ. (2017). Otra didáctica de la historia para otra escuela. Lección inaugural del curso 2017-2018. Huelva: Universidad de Huelva. Available at: http://www.ub.edu/histodidactica/images/documentos/pdf/estepa%20libro.pdf (Accessed October 18, 2021).

15

Frías-NavarroD. (2020). Apuntes de consistencia interna de las puntuaciones de un instrumento de medida. Valencia: Universidad de Valencia. Available in: https://www.uv.es/friasnav/AlfaCronbach.pdf (Accessed October 18, 2021).

16

García HernándezM. L.Porto CurrásM.Hernández ValverdeF. J. (2019). El aula invertida con alumnos de primero de magisterio: fortalezas y debilidades. Redu17 (2), 89–106. 10.4995/redu.2019.11076

17

García PérezF. F. (2021). De las dificultades, posibilidades y retos del trabajo en torno a problemas. Reidics9, 6–13. 10.17398/2531-0968.09.6

18

GomesA. (2020). História e da Didática da História: práticas e conceções na formação inicial de professores Do ensino básico (10-12 anos). Enseñanza de las Ciencias Sociales19, 5–16. 10.1344/ECCSS2020.19.2

19

Gómez CarrascoC. J.Chaparro SainzÁ.Felices de la FuenteM. d. M.Cózar GutiérrezR. (2020a). Estrategias metodológicas y uso de recursos digitales para la enseñanza de la historia. Análisis de recuerdos y opiniones del profesorado en formación inicial. Aula abierta49 (1), 65–74. Available at:https://reunido.uniovi.es/index.php/AA/article/view/14224/12777 (Accessed October 18, 2021). 10.17811/rifie.49.1.2020.65-74

20

Gómez CarrascoC. J.Rodríguez-MedinaMirallesJ. P.Miralles MartínezP.Arias GonzálezV. B. (2021). Efectos de un programa de formación del profesorado en la motivación y satisfacción de los estudiantes de historia en enseñanza secundaria. Revista de Psicodidáctica26 (1), 45–52. Available at: https://www--sciencedirect--com.ual.debiblio.com/science/article/pii/S2530380520300162/pdfft?md5=e08abcb429a918d05b6636d8a85be5cc&pid=1-s2.0-S2530380520300162-main.pdf (Accessed November 5, 2021). 10.1016/j.psicod.2020.07.002

21

GómezC. J.ChaparroA.FelicesM.InarejosJ. A. (2020b). “Perceptions Regarding Historical Competences in Trainee Geography and History Teachers,” in Handbook of Research on Teacher Education in History and Geography. Editors GómezC. J.MirallesP.LópezR.Berlín: Peter Lang), 177–199.

22

GómezC. J.SoutoX. M.MirallesP. (Editors) (2021). Enseñanza de las ciencias sociales para una ciudadanía democrática. Estudios en homenaje al profesor Ramón López Facal. Barcelona: Octaedro.

23

GonzálezM.FuentesE. J. (2011). El Practicum en el aprendizaje de la profesión docente. Revista de Educación354, 47–70. Available at: http://www.revistaeducacion.educacion.es/re354/re354_03.pdf (Accessed October 18, 2021).

24

GuerreroR.ChaparroÁ.FelicesM. M. (2020). “La práctica docente en Didáctica de las Ciencias Sociales a revisión: una investigación en el Grado en Educación Primaria,” in Claves para la innovación pedagógica ante los nuevos retos. Editors López-MenesesE.Cobos-SanchizD.Molina-GarcíaL.Jaén-MartínezA.Martín-PadillaA. H. (Barcelona: Octaedro), 1574–1582.

25

HernándezF.MaquilónJ. J. (2010). “Introducción a los diseños de investigación educativa,” in Principios, métodos y técnicas esenciales para la investigación educativa. Editor NietoS. (Madrid: Dykinson), 109–126.

26

Iranzo-GarcíaP.Camarero-FiguerolaM.Barrios-ArósC.Tierno-GarcíaJ.-M.Gilabert-MedinaS. (2018). ¿Qué Opinan los Maestros sobre las Competencias de Liderazgo Escolar y sobre su Formación Inicial?Reice3 (3), 29–48. 10.15366/reice2018.16.3.002

27

IzadiniaM. (2014). Teacher Educators' Identity: a Review of Literature. Eur. J. Teach. Edu.37 (4), 426–441. 10.1080/02619768.2014.947025

28

LoughranJ. J.HamiltonM. L.LaBoskeyV. K.RussellT. (Editors) (2004). International Handbook of Self-Study of Teaching and Teacher Education Practices (Dordrecht: Kluwer Academic Publishers).

29

Jo TondeurJ.Sarah Van de VeldeS.Hans VermeerschH.Mieke Van HoutteM. (2016). Gender Differences in the ICT Profile of University Students: A Quantitative Analysis. Digest. J. Divers. Gend. Stud.3 (1), 57–77. 10.11116/jdivegendstud.3.1.0057

30

KitchenJ.StevensD. (2008). Action Research in Teacher Education. Action. Res.6 (1), 7–28. 10.1177/1476750307083716

31

Lía De LonghiA.FerreyraA.PemeC.BermudezG. M. A.QuseL.MartínezS.et al (2012). La interacción comunicativa en clases de ciencias naturales. Rev_Eureka_ensen_divulg_cienc9 (2), 178–195. Available at: https://www.redalyc.org/pdf/920/92024542002.pdf (Accessed October 18, 2021). 10.25267/rev_eureka_ensen_divulg_cienc.2012.v9.i2.02

32

LoughranJ. (2005). Researching Teaching about Teaching: Self-Study of Teacher Education Practices. Studying Teach. Edu.1 (1), 5–16. 10.1080/17425960500039777

33

LucasBem-HajaSiddiqM. P. F.Bem-HajaP.SiddiqF.MoreiraA.RedeckerC. (2021). The Relation between In-Service Teachers' Digital Competence and Personal and Contextual Factors: What Matters Most?Comput. Edu.160, 104052. 10.1016/j.compedu.2020.104052

34

LuikP.TaimaluM.SuvisteR. (2018). Perceptions of Technological, Pedagogical and Content Knowledge (TPACK) Among Pre-service Teachers in Estonia. Educ. Inf. Technol.23, 741–755. 10.1007/s10639-017-9633-y

35

McMillanJ. H.SchumacherS. (2005). Investigación Educativa. Madrid: Pearson Educación.

36

Miralles MartínezP.Gómez CarrascoC. J.Monteagudo FernándezJ. (2019). Percepciones sobre el uso de recursos TIC y "MASS-MEDIA» Para la enseñanza de la historia. Un estudio comparativo en futuros docentes de España-Inglaterra. Educación XX122 (2), 187–211. 10.5944/educXX1.21377

37

Miralles-MartínezP.Gómez-CarrascoC. J.Arias-GonzálezV. B.Fontal-MerillasO. (2019). Digital Resources and Didactic Methodology in the Initial Training of History Teachers. Comunicar: Media Edu. Res. J.27 (27), 45–56. 10.3916/C61-2019-04

38

MonereoC. (2013). La investigación en la formación del profesorado universitario: hacia una perspectiva integradora. Infancia y Aprendizaje36 (3), 281–291. 10.1174/021037013807533052

39

MonereoC.PanaderoE.ScarteziniR. (2013). SharEVents. La utilización de informes compartidos sobre incidentes críticos como medio para la formación docente. Cadernos de Educação42, 1–26. Available at: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/236022512_SharEVents_La_utilizacion_de_informes_compartidos_sobre_incidentes_criticos_como_medio_para_la_formacion_docente (Accessed October 18, 2021).

40

MonteroL.MartínezE.ColénM. (2017). Los estudios de Grado en la formación inicial de Maestros en Educación Primaria. Miradas de formadores y futuros maestros. Profesorado. Revista de Currículum y Formación de Profesorado21 (1), 1–16. Available at: https://recyt.fecyt.es/index.php/profesorado/article/view/58041 (Accessed October 18, 2021).

41

MorilR. (2011). Buenas prácticas en la didáctica de las ciencias sociales. Revista EDETANIA40, 173–187. Available at: https://riucv.ucv.es/handle/20.500.12466/758 (Accessed October 18, 2021).

42

Ortega-SánchezD.PagèsJ. (2017). Literacidad crítica, invisibilidad social y género en la formación del profesorado de Educación Primaria. REIDICS. Revista de Investigación en Didáctica de Las Ciencias Sociales1, 102–117. 10.17398/2531-0968.01.118

43

Ottenbreit-LeftwichA. T.ErtmerP. A.TondeurJ. (2015). “7.2 Interpretation of Research on Technology Integration in Teacher Education in the USA: Preparation and Current Practices,” in International Handbook of Interpretation in Educational Research (Dordrecht: Springer), 1239–1262. 10.1007/978-94-017-9282-0_61

44

OvensA.FletcherT. (2014). “Doing Self-Study: The Art of Turning Inquiry on Yourself,” in Self-study in Physical Education: Exploring the Interplay between Scholarship and Practice. Editors OvensA.FletcherT. (London: Springer), 3–14. Available at: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/262764296_Doing_Self-Study_The_Art_of_Turning_Inquiry_on_Yourself (Accessed October 18, 2021). 10.1007/978-3-319-05663-0_1

45

PagèsJ. (2019). Ciudadanía global y enseñanza de las Ciencias Sociales: retos y posibilidades para el futuro. REIDICS: Revista de Investigación en Didáctica de las Ciencias Sociales5, 5–22. 10.17398/2531-0968.05.5

46

PagèsJ.SantistebanA. (2014). “Una mirada desde el pasado al futuro en la didáctica de las Ciencias Sociales,” in Una mirada al pasado y un proyecto de futuro. Investigación e innovación en Didáctica de las Ciencias Sociales. Editors PagésJ.SantistebanA. (Barcelona: UAB, AUPDCS), 17–39. Available at: https://dialnet.unirioja.es/servlet/articulo?codigo=4696490 (Accessed October 18, 2021).

47

PapadakisS. (2018). Evaluating Pre-service Teachers' Acceptance of mobile Devices with Regards to Their Age and Gender: a Case Study in Greece. Ijmlo12 (4), 336–352. 10.1504/ijmlo.2018.10013372

48

Paricio RoyoJ.Fernández MarchA.Trillo AlonsoF. (2020). Veinte años de cambio en la educación superior: logros, fracasos y retos pendientes. Homenaje a Miguel Ángel Zabalza. Redu18 (1), 9–15. 10.4995/redu.2020.13713

49

ParraD.FuertesC. (2019). Reinterpretar la tradición, transformar las prácticas. Valencia: Tirant Lo Blanch.

50

PérezÁ. I. (2019). Ser docente en tiempos de incertidumbre y perplejidad. Márgenes0 (0), 3–17. 10.24310/mgnmar.v0i0.6497

51

PinnegarS.HamiltonM. L. (2009). Self-study of Practice as a Genre of Qualitative Research: Theory, Methodology, and Practice. London: Springer.

52

PithouseK.MitchellC.WeberS. (2009). Self‐study in Teaching and Teacher Development: a Call to Action. Educ. Action. Res.17 (1), 43–62. 10.1080/09650790802667444

53

PostareffL.Lindblom-YlänneS.NevgiA. (2008). A Follow-Up Study of the Effect of Pedagogical Training on Teaching in Higher Education. High Educ.56, 29–43. 10.1007/s10734-007-9087-z

54

PostareffL.Lindblom-YlänneS.NevgiA. (2007). The Effect of Pedagogical Training on Teaching in Higher Education. Teach. Teach. Edu.23, 557–571. 10.1016/j.tate.2006.11.013

55

ReismanA. (2012). Reading like a Historian: A Document-Based History Curriculum Intervention in Urban High Schools. Cogn. Instruction30 (1), 86–112. 10.1080/07370008.2011.634081

56

RitterJ. K. (2010). Revealing Praxis: A Study of Professional Learning and Development as a Beginning Social Studies Teacher Educator. Theor. Res. Soc. Edu.38 (4), 545–573. 10.1080/00933104.2010.10473439

57

Roblizo ColmeneroM. J.Cózar GutiérrezR. (2015). Usos y competencias en TIC en los futuros maestros de educación infantil y primaria: hacia una alfabetización tecnológica real para docentes. Pixel-Bit47, 23–39. Available at: https://idus.us.es/handle/11441/45279 (Accessed October 18, 2021). 10.12795/pixelbit.2015.i47.02

58

Sánchez FusterM. C. (2017). Evaluación de los recursos utilizados en Ciencias Sociales, Geografía e Historia. Murcia: Tesis Doctoral inédita, Universidad de Murcia. Available at: https://www.tdx.cat/handle/10803/457509 (Accessed October 18, 2021).

59

SangG.ValckeM.BraakJ. v.TondeurJ. (2010). Student Teachers' Thinking Processes and ICT Integration: Predictors of Prospective Teaching Behaviors with Educational Technology. Comput. Edu.54 (1), 103–112. 10.1016/j.compedu.2009.07.010

60

SantistebanA. (2019a). “La práctica de enseñar a enseñar ciencias sociales,” in Enseñar y aprender didáctica de las Ciencias Sociales: la formación del profesorado desde una perspectiva sociocrítica. Editors HortasM. J.GomesA.de AlbaN. (Lisboa: Escola Superior de Educaçao de Lisboa, AUPDCS), 1079–1092. Available at: http://didactica-ciencias-sociales.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/10/E-book-Simposio-XXX_vf_04_2020_comp.pdf (Accessed October 18, 2021).

61

Santisteban FernándezA. (2019b). La enseñanza de las Ciencias Sociales a partir de problemas sociales o temas controvertidos: estado de la cuestión y resultados de una investigación. FdP10, 57–79. 10.14516/fdp.2019.010.001.002

62

SchönD. (1992). La formación de profesionales reflexivos. Barcelona: Paidós.

63

Sosa DíazM. J.Guerra AntequeraJ.Cerezo PizarroM. (2021). Flipped Classroom in the Context of Higher Education: Learning, Satisfaction and Interaction. Edu. Sci.11 (8), 416. 10.3390/educsci11080416

64

Sosa DíazM. J.Palau MartínR. F. (2018). Flipped Classroom para la Formación del Profesorado: Perspectiva del alumnado. Redu16 (2), 249–264. 10.4995/redu.2018.7911

65

Souto GonzálezX. M.García MonteagudD. (2019). Conocer las rutinas para innovar en la geografía escolar. Rev. Geogr. Norte Gd.74, 207–228. 10.4067/S0718-34022019000300207

66

SoutoX. M.García-MonteagudoD. (2016). La Geografía escolar ante el espejo de su representación social. Didáctica Geográfica17, 177–201. Available at: https://didacticageografica.age-geografia.es/index.php/didacticageografica/article/view/365 (Accessed October 19, 2021). 10.4067/S0718-34022019000300207

67

TackH.VanderlindeR. (2014). Teacher Educators' Professional Development: Towards a Typology of Teacher Educators' Researcherly Disposition. Br. J. Educ. Stud.62 (3), 297–315. 10.1080/00071005.2014.957639

68

UibuK.SaloA.UgasteA.Rasku-PuttonenH. (2017). Beliefs about Teaching Held by Student Teachers and School-Based Teacher Educators. Teach. Teach. Edu.63, 396–404. 10.1016/j.tate.2017.01.016

69

VaillantD.MarceloC. (2015). El ABC y D de la Formación Docente. Madrid: Narcea.

Summary

Keywords

higher education, social sciences didactics, active learning, student learning, teacher professional development, teacher education practices

Citation

Felices-De la Fuente MM and Chaparro-Sainz Á (2021) Opinions of Future Teachers on Training in Social Sciences Didactics. Front. Educ. 6:803289. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2021.803289

Received

27 October 2021

Accepted

23 November 2021

Published

21 December 2021

Volume

6 - 2021

Edited by

José Antonio Marín Marín, University of Granada, Spain

Reviewed by

Delfín Ortega-Sánchez, University of Burgos, Spain

Pedro Miralles-Martínez, University of Murcia, Spain

Updates

Copyright

© 2021 Felices-De la Fuente and Chaparro-Sainz.

This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: María del Mar Felices-De la Fuente, marfelices@ual.es

This article was submitted to Digital Learning Innovations, a section of the journal Frontiers in Education

Disclaimer

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.