- 1Student Work Department, Central South University, Changsha, China

- 2School of Marxism, Central South University, Changsha, China

- 3The Hunan Provincial Research Base for Educational Public Opinion and Risk Prevention, Changsha, China

- 4School of Public Administration, Central South University, Changsha, China

- 5School of Metallurgy and Environment, Central South University, Changsha, China

- 6Organization Department of the Party Committee, Central South University, Changsha, China

Introduction: Adopting an information behavior perspective, this study reveals the mechanisms influencing college students' behavioral intention to use Generative Artificial Intelligence (GAI) tools.

Methods: Focusing on the behavioral intention of college students to utilize generative AI tools, the study employed a modified Unified Theory of Acceptance and Use of Technology (UTAUT) model to analyze the behavioral intention of Chinese university students regarding GAI tools.

Results: Data were collected from 378 students and the results show that: effort expectation, performance expectation, and individual innovation positively affect the willingness to use GAI tools, whereas perceived trust and perceived risk do not. Effort expectation and performance expectation indirectly affects the behavioral intention through the mediation of personal innovativeness, while perceived humanlikeness negatively affect the willingness to use.

Discussion: These findings offer a valuable tool for policymakers and faculty members to understand the factors driving GAI acceptance or resistance. Thus, maximize the benefits of applying GAI tools and minimize potential risks and negative sentiment. Consequently, this understanding can facilitate the maximization of benefits derived from GAI tool application and the minimization of potential risks and negative sentiment. Such insights are crucial for the education sector to effectively embrace the transformative potential of GAI and foster the innovative capacity of students.

1 Introduction

Named “DeepSeek moment,” Chinese AI chatbot DeepSeek reshaped the AI chatbot landscape and attracted users for its powerful performance, initiating another wave of GAI promotion. GAI refers to computational techniques capable of generating meaningful content, such as text, images, or audio, derived from training data (Feuerriegel et al., 2024), which demonstrates potential in providing new perspectives for innovation and transformation.

Among sectors, 81.07% of AI publications (2010–2022) fell into the education sector (Nestor et al., 2024), and the potential of AI empowerment has been observed (Chen et al., 2024). This trend is largely attributable to the proactive adoption of emerging technologies by universities and students (Chen et al., 2024; Wang et al., 2025; Bates et al., 2020). However, the expansion of GAI also introduces potential risks and growing concerns. Beyond advantages, it also raises issues such as the digital divide, academic integrity, and ethical challenges (Global Education Monitoring Report Team, 2023). In order to make the most of GAI and avoid concomitant risks, deeper studies on individuals' behavioral intention on GAI, revealing the mechanism behind are necessary.

Targeting the adoption of emerging technologies like GAI, many models are given to analyze and predict the use behavior, including the Theory of Planned Behavior (TPB), Expectation Confirmation Model (ECM), Technology Acceptance Model (TAM), etc. Proposed in 2003, the unified theory of acceptance and use of technology (UTAUT) model raised the bar to 70% in terms of explaining technology adoption compared to the 30% bar of TAM (Shaper and Pervan, 2007), and 40% bar of TAM2 (Oye et al., 2014), indicating that the UTAUT offers a more accurate prediction and description of the mechanism of use behavior. The excellent performance of UTAUT makes it a potential player on this new track of studying GAI acceptance.

Acknowledging the transformative innovations introduced by GAI, the current study aims to investigate college students' behavioral intentions regarding the use of GAI tools and to illustrate the underlying mechanisms. More bluntly, we will construct an extended UTAUT model illustrating the effects on behavioral intention of GAI tools from various determinants, hypothesize relationships between determinants, and examine these hypotheses based on the data we acquire from the questionnaire on Chinese college students. This research is expected to provide critical insights into GAI adoption among Chinese university students, assist university administrations and faculty members in evaluating its influence, and facilitate the formulation of policies and regulations that encourage the rational application of GAI in education while mitigating potential negative impacts.

The rest of this research includes the following: Section 2 provides the literature review in this field and the study design as well as the proposed model; Section 3 presents research hypotheses; Section 4 discusses the research methodology, visualized the model, and provides a brief introduction on data acquisition and our descriptive analysis; the research results we obtained are elucidated in Section 5, and we thoroughly discuss and conclude our study in Sections 6 and 7, respectively.

2 Literature review

2.1 Previous studies on GAI

For its fascinating performance and great ambitions, GAI became a research frontier recently (Kanbach et al., 2024), as we can see a triple growth in the number of publications from 2010 to 2022 (Nestor et al., 2024). However, potential capacity and risks make this tool a double-edged sword, and more in-depth studies are required to better understand GAI in education (Chen et al., 2024). In fact, as a background, researchers have started to explore if AI can be applied to education since the 1970s (du Boulay, 2016), and at present, the wide application of GAI brings a rapidly changing landscape (Baidoo-Anu and Ansah, 2023).

Previous educational studies on GAI can be broadly categorized into three levels based on their research scope. At the macro level, research has addressed the introduction and widespread adoption of GAI within the education sector, examining its potential advantages and future challenges (Chen et al., 2024; Baidoo-Anu and Ansah, 2023; Alasadi and Baiz, 2023). At the meso level, some essays discussed how educational institutions should address this rapid change, such as adopting a more open mind to GAI tools and establishing clear guidelines for their use (Alasadi and Baiz, 2023). At a micro level, we also discovered numerous studies analyzing the nuanced effects of applying GAI on teachers and students, such as the changes in teachers' work and roles (Kshetri, 2023), students' learning experience (Stojanov, 2023), behavior and cognitive achievement (Jaboob et al., 2025), and academic achievement (Sun and Zhou, 2024). Given the extensive current user base of GAI tools, a generalized description of usage behavior across such a broad population becomes less accurate and practical. Since tertiary education is considered one of the most affected sectors (Alqahtani et al., 2023) and university students are found to have more accessibility to GAI technology (Chen et al., 2024; Bates et al., 2020), studies specifically concerned about the college students' behavioral intention of GAI services proliferated (Chan and Tsi, 2024; Diao et al., 2024; Strzelecki and ElArabawy, 2024).

Focusing on the adoption behavior of GAI services, various information systems theories have been employed (Dai et al., 2024), which propose potential determinants and explain usage behavior through these determinants and their impact pathways. Through a literature review on AI adoption, the technology acceptance model (TAM) and the unified theory of acceptance and use of technology (UTAUT) are considered as two prominent themes and adoption theories in this specific field (Khanfar et al., 2024).

2.2 Unified theory of acceptance and use of technology (UTAUT)

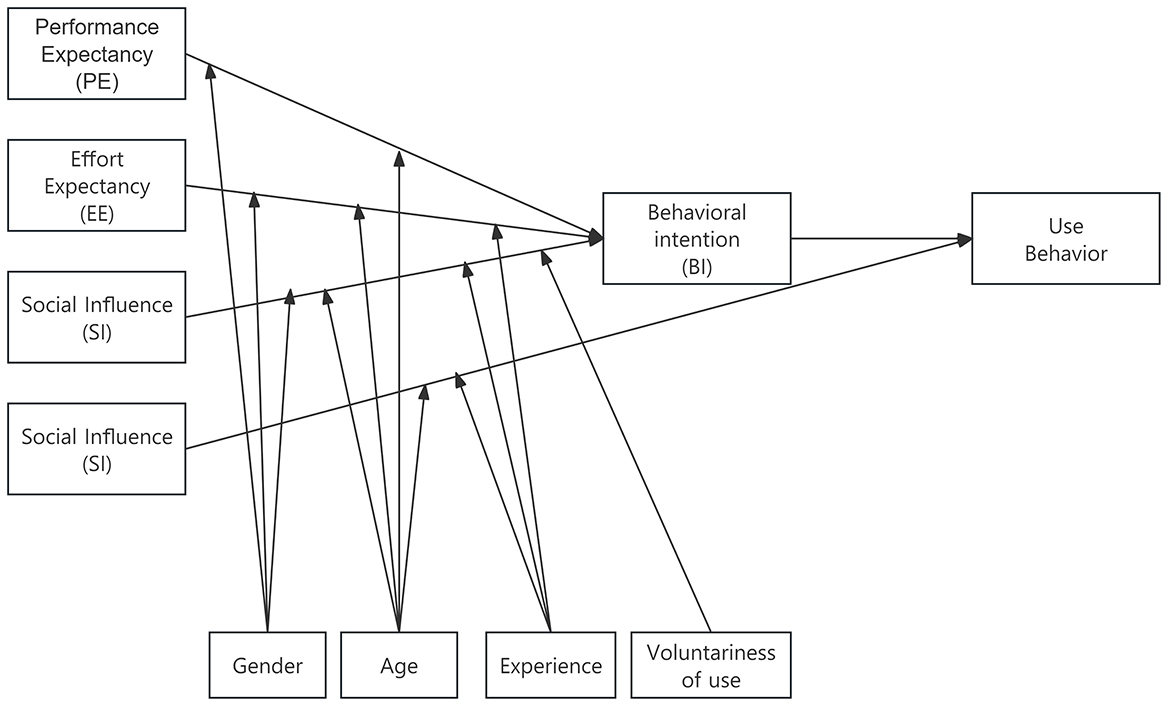

In 2003, Venkatesh et al. integrated core elements from eight models and prominent theories, and proposed the unified theory of acceptance and use of technology (UTAUT) model to explain new technology adoption, acceptance, and usage (Venkatesh et al., 2003). Learning from theories like TRA, TPB, and TAM, the UTAUT model consists of four moderating variables (experience, voluntariness, gender, and age) and four core variables (performance expectancy, effort expectancy, social influence, and facilitating conditions). Since its introduction, the UTAUT model has been widely applied and tested in many countries and numerous fields, and it has outperformed in predicting the use behavior of novel technologies, including e-learning system (Abbad, 2021). Based on previous literature, we can argue that the UTAUT model was well-tested and its robustness was validated. Thus, a deeper examination of applying UTAUT in behavioral studies on AI use can be expected as the model was utilized only to a limited extent (Khanfar et al., 2024) currently. The classic UTAUT model is shown in Figure 1 below.

2.3 Research gaps

A comprehensive review reveals several limitations within previous studies. First, existing studies made valuable attempts to introduce determinants like task-technology fit and habit (Du and Lv, 2024; Sergeeva et al., 2025), but anthropomorphic features of GAI are largely ignored; Second, given the rapid proliferation of GAI tool users subsequent to the launch of ChatGPT, a more nuanced understanding of diverse user groups has become imperative (Strzelecki and ElArabawy, 2024). Observing these, developing a theoretical framework that explains GAI use behavior and covers features arising from the technology and the specific user group is necessary. As stated above, the group of college students is a suitable object for the high coverage of GAI services among them and the prior research accumulation on the education sector.

More specifically, the traditional model of UTAUT is insufficient for describing and predicting the use behavior of AI, because its scope is limited to the use of technologies and cannot explain the complex processes involved in AI adoption (Chi et al., 2020). It is imperative that novel characteristics inherent to Generative Artificial Intelligence (GAI) tools and the unique attributes of college student users are explicitly addressed within the proposed model. Most studies only used a subset of the UTAUT model, and moderators were frequently dropped (Dwivedi et al., 2019), this strategy of extending UTAUT is frequently applied and achieved rather good results (Al-Saedi et al., 2020; Hu et al., 2020). This inspired us to introduce extended determinants and moderators like perceived humanlikeness and domain expertise since these determinants are extracted from the actual use behavior and can be beneficial to the explanatory power of the proposed model. On the other hand, technology acceptance models, including the UTAUT, are interdisciplinary in nature (Wrycza et al., 2017), and this feature allows the UTAUT model to remain effective by extending. Building on these existing gaps, our study is expected to provide a more detailed explanation of GAI adoption and inspire university officers and students to make good use of GAI in the future.

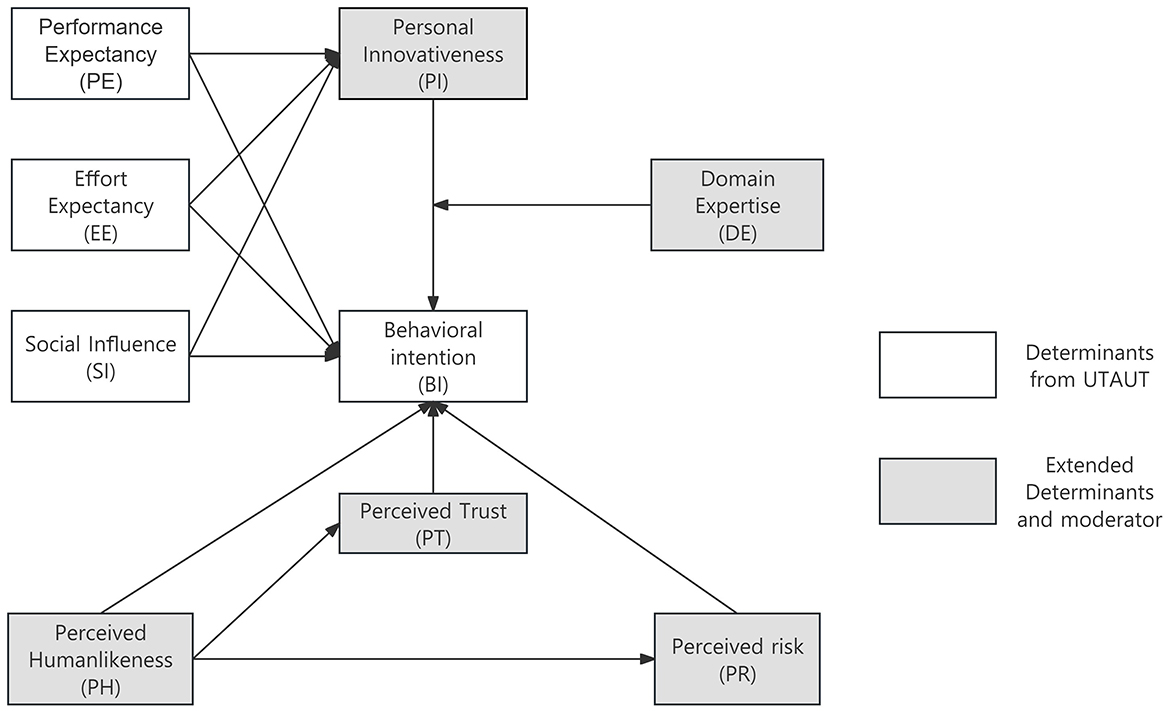

We decided to drop facilitating conditions as a core variable and all moderators, then introduce four determining components, including perceived risk (PR), perceived trust (PT), perceived humanlikeness (PH), personal innovativeness (PI), and another moderator: domain expertise (DE), to better reflect the behavioral intentions of GAI tools among college students. The theoretical basis and hypotheses related to these determinants are explained in the next chapter.

3 Research hypotheses

3.1 Performance expectancy (PE)

Performance expectancy (PE) is defined as “the degree to which an individual perceives that using a system will help him or her to improve job performance” (Venkatesh et al., 2003). In the current study, it can be understood that using GAI tools assists college students in their courses, inquiry learning, etc. A very recent study (Schei et al., 2024) on perceptions and use of AI chatbots among students in higher education shows its significance in AI adoption, and it is also considered the most reliable predictor (Venkatesh et al., 2012). So the following hypotheses are given based on the discussion above:

H1: PE has a positive effect on PI.

H2: PE has a positive effect on behavioral intention (BI).

3.2 Effort expectancy (EE)

Effort Expectancy is the degree of ease associated with the use of the system (Venkatesh et al., 2003). In the context of new technological innovation adoption, this usability is as crucial as functional value (Davis, 1989), so we can hypothesize:

H3: EE has a positive effect on BI.

H4: EE has a positive effect on PI.

3.3 Social influence (SI)

Social Influence (SI) is defined as “the degree to which an individual perceives that important others believe he or she should use the new system” (Venkatesh et al., 2003). In the current study, we can assume that college students will have a stronger intention to try GAI tools if their close friends or professors are using these tools and have positive feedback. Therefore, our hypotheses are as follows:

H5: SI has a positive effect on BI.

H6: SI has a positive effect on PI.

3.4 Perceived trust (PT)

Perceived trust can be described as believing that the service (i.e., GAI tools here) is reliable and safe to adopt (Al-Saedi et al., 2020), and it is one of the leading success factors that affect the adoption of a new information system (Sharma and Sharma, 2019; Leschanowsky et al., 2024). Assuming college students who trust AI tools more will have a stronger intention to apply them, we can hypothesize that:

H7: PT has a positive effect on BI.

3.5 Perceived risk (PR)

Perceived risk was originally proposed by Bauer (1967) in consumer behavior studies. In this study, it can be defined as users' expectations of potential problems following the adoption of AI tools (Lee, 2009). Prior studies have revealed the effect of perceived risk on users' intention to use AIGC-assisted design tools, including concerns about ethics (Wu et al., 2023) and privacy (Chen et al., 2023). Perceived risk might negatively influence behavioral intention since users tend to be risk-averse, and introducing perceived risk helps to understand concerns and worries among college students facing GAI. So we can propose that:

H8: PR has a negative effect on BI.

3.6 Perceived humanlikeness (PH)

Perceived humanlikeness is related to users' responses to an entity with human-like features (Kim et al., 2022), or more specifically, whether human-like features will affect college students' intentions of using AI tools in this study. Human-like characteristics are generally categorized into appearances, thoughts, and emotions (Ruijten et al., 2019). According to scholars, the current human-AI interaction is evolving to foster emotional connections and imitate cognitive processes (Kang and Kang, 2024; Seok et al., 2025). Some studies claimed this determinant shows a positive effect on people's engagement with robots (Chidambaram et al., 2012) and people's trust (Park et al., 2024; Glikson and Woolley, 2020). However, contradictory results also indicate that creepiness toward AI chatbots can also increase as they become more anthropomorphized based on theories like Computers are social actors (CASA) paradigm (Seok et al., 2025; Konya-Baumbach et al., 2023), and that might trigger negative emotions and promote conservative decision-making. So we can hypothesize that:

H9: PH has a positive effect on PR.

H10: PH has a positive effect on PT.

H11: PH has a positive effect on BI.

3.7 Personal innovativeness (PI)

Personal innovativeness is defined as “a predisposition or attitude describing a salesperson's learned and enduring cognitive evaluations, emotional feelings, and action tendencies toward adopting new information technologies” by Schillewaert et al. (2005). This predictor has obtained support from studies across disciplines, including studies on mobile payment (Patil et al., 2020), E-learning (Twum et al., 2022), etc. So, we can formulate a hypothesis here:

H12: PI has a positive effect on BI.

3.8 Domain expertise (DE) as a moderator

Based on Dreyfus and Dreyfus (1986), gaining expertise in a domain is defined as going beyond ordinary learning from rule-based and fact-based “knowing that” toward experience-based “knowing how.” Domain expertise can be considered as an assessment of an individual's knowledge of applying a technology (Bhagat and Sambargi, 2019). Users with domain expertise can use a technology effectively without much concern because of knowing the mechanism or principles behind it. Although most GAI tools tried to be user-friendly and users can use their service in the form of chatting, the mechanism behind these AI models remains unfamiliar and similar to a black box to most users, and we guess that college students will have a stronger intention to give AI tools a try if they have the expertise in AI sector, and some studies on algorithms (Mahmud et al., 2024; Turel and Kalhan, 2023) verified this suspicion. We can hypothesize that:

H13: The relationship between PI and BI is moderated by DE.

4 Method

4.1 Measurement instruments

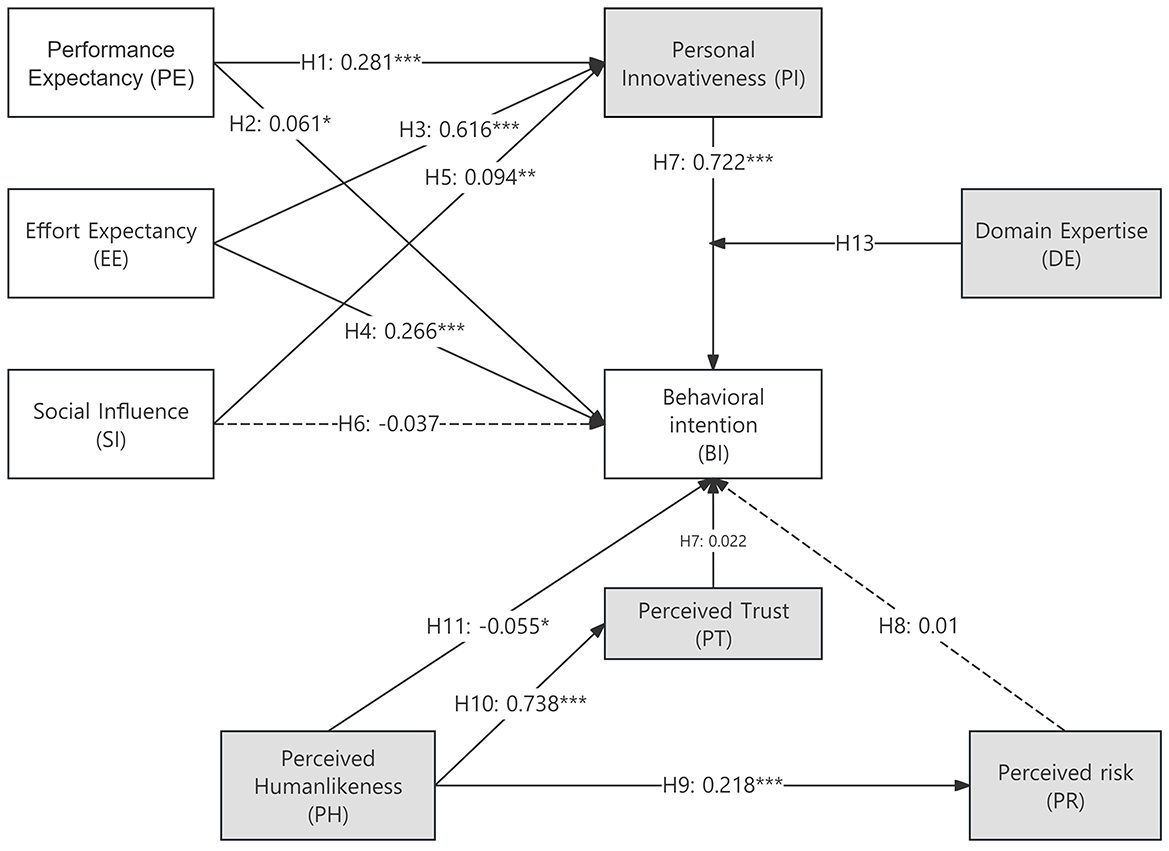

To conclude, we made a few changes to reflect the special features of GAI services for university students. Figure 2 illustrates this extended model below, arrows between different determinants represent research hypotheses as stated above.

Following the procedures by DeVellis (2003), we prepared 3–5 questions for each variable to measure its effect, and most of them are based on previous studies. A Seven-point Likert was adopted to quantify the construct. Inspired by Hair et al. (2012), a pilot study was conducted to check the reliability and the validity of the questionnaire, showing a return rate of 77.0% (n = 100, 100 pretest questionnaires distributed). After reliability and validity analyses, we verified the effectiveness of our solution. It is worth mentioning that this survey is for Chinese college students, and we distributed the Chinese version developed by translation experts to our participants for adequate understanding. The formal questionnaire with a parallel Chinese version is attached in Appendix A.

4.2 Data collection and descriptive analysis

The target respondents are Chinese college students with GAI services experience. Our questionnaire was distributed on the wjx.cn platform, a data analysis platform with over 60% market share in China, to obtain information. On bias mitigation, by specifying our requirements on participants, only registered Chinese college students on this platform can be selected. Additionally, all participants need to confirm their basic information and GAI experience prior to answering questions. Therefore, we can ensure all participants satisfy our requirements. Ultimately, probability sampling was employed to mitigate bias and minimize the confounding effect.

The formal survey was conducted between April 11 and April 20, 2024. A total of 433 answers were collected, and we deleted some answers because they were completed in an either too long or too short time, or given by GAI freshmen (answered “I do not have GAI use experience”). As a result, 378 valid questionnaires were returned, for a valid return rate of 87.2%, which meets the requirement of AMOS software that the number of samples should be 10 times the measurement questions.

The basic information of the participants was as follows: male respondents accounted for a relatively large proportion of the sample, 60.3%, while females accounted for 39.7%. In terms of education level, undergraduate students accounted for the highest proportion of 80.7%, master's and doctoral students accounted for 14.5%, and junior college students accounted for 4.8%. In terms of major, 76.5% of the students studied science, medicine, and engineering, and 23.5% of the participants majored in arts and social sciences. From a regional perspective, the sample covered 15 provinces across China, with Hunan Province accounting for the highest proportion.

5 Results

Our analysis was arranged using the two-step approach developed by Anderson and Gerbing (1988). We employed IBM SPSS AMOS (v. 26) to perform structural equation modeling (SEM), which is a comprehensive tool employed to test both the reliability and validity of the measures of theoretical constructs and the hypothesized relationships between determinants (Barclay et al., 1995; Hair et al., 2010). Since DE was introduced as a moderator, this analysis also should include another step: Analyzing the moderating effect (see Appendix for brevity).

5.1 Measurement model

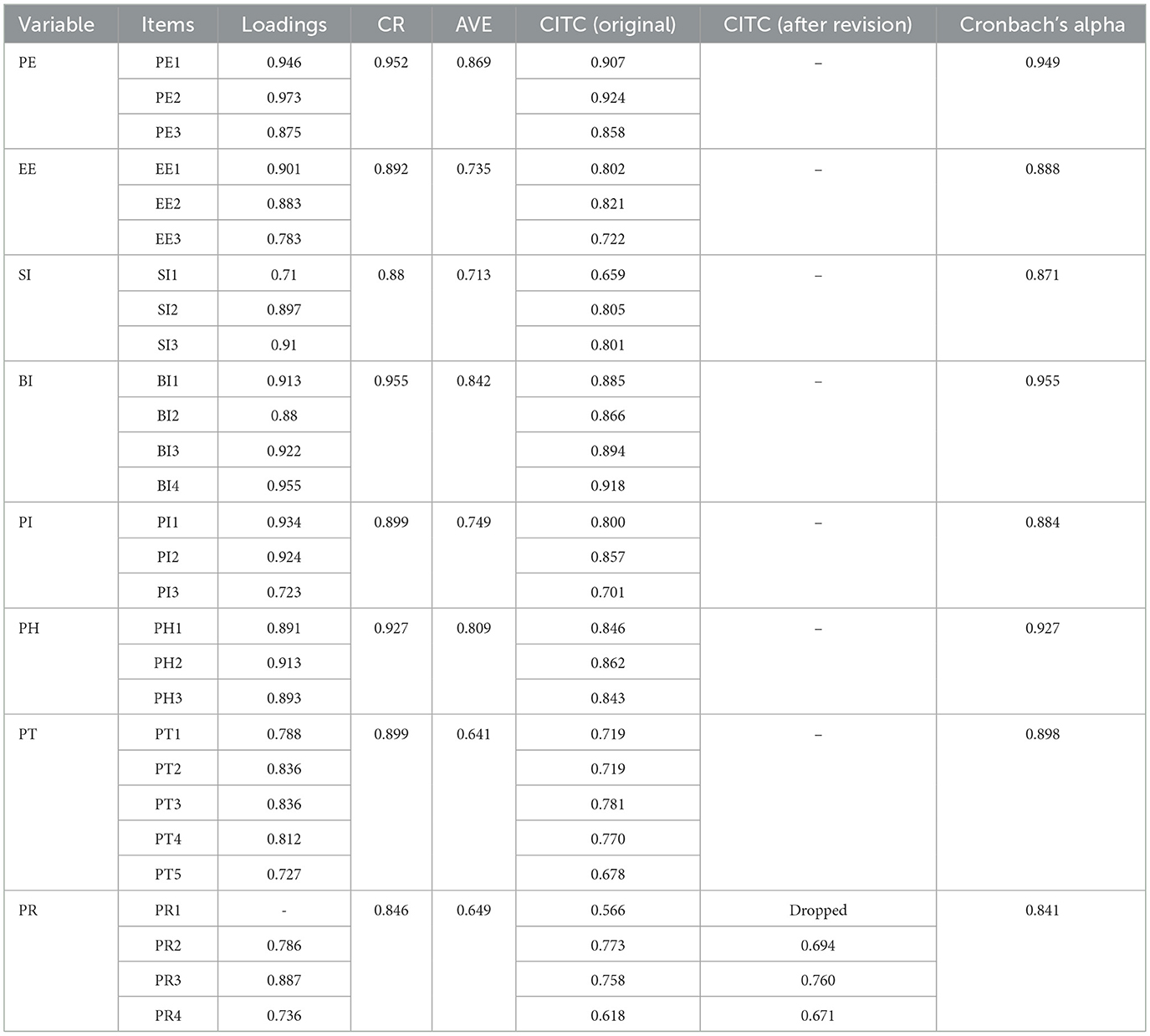

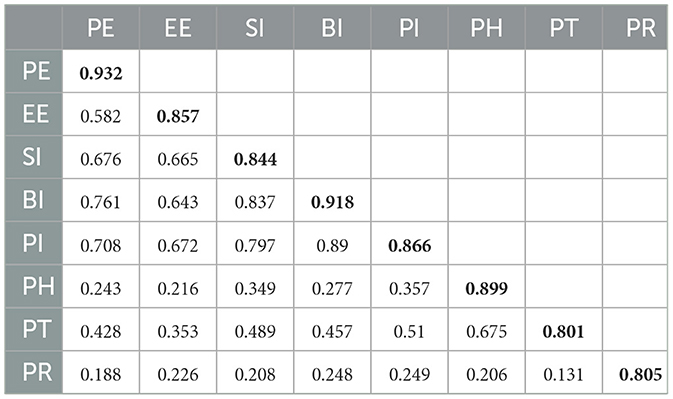

Reliability testing is used to verify the consistency and stability of the scale, and validity testing is used to show the extent to which the scale reveals the features, reflecting the accuracy and usefulness of the scale. After the literature review, factor loadings, composite reliability (CR), average variance extracted (AVE), Corrected item-total correlation (CITC), cross-loadings criteria, and Cronbach's alpha values are adopted as quality criteria. The results are as Tables 1, 2 shown.

The measurement model was assessed for construct reliability, indicator reliability, convergence validity, and discriminant validity (Baptista and Oliveira, 2015; Ustun et al., 2024). Based on the results, all Cronbach's alpha and CR are greater than 0.80, suggesting strong construct reliability (Straub, 1989); All loadings are higher than 0.7, suggesting indicator reliability (Churchill, 1979); The convergence validity was tested with AVE, and it is proven as all constructs compared positively against the minimum acceptable value of 0.50 (Fornell and Larcker, 1981).

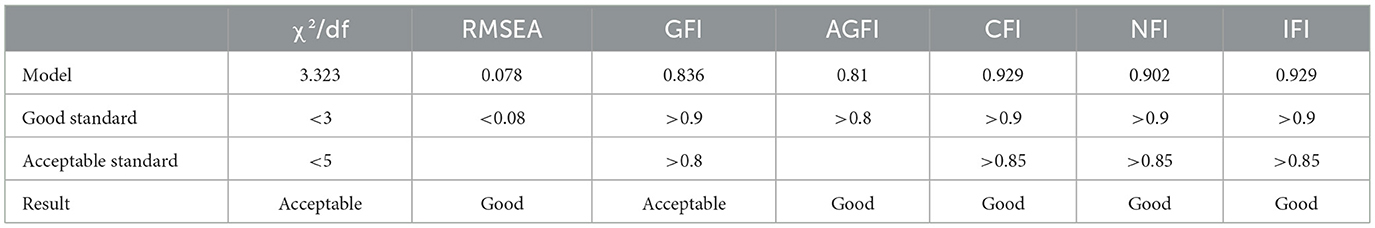

To test the discriminant validity, CITC, the square root of the AVE, and maximum likelihood estimation (MLE) are applied. The original CITC indicates that PR1 failed to pass the test, and it was dropped. CITC of PR2, PR3, and PR4 remains greater than 0.6 (Ustun et al., 2024) after the revision. Simultaneously, Table 2 shows the square root of the AVE in bold along the diagonal and is greater than its correlations with the rest of the constructs (Fornell and Larcker, 1981); For further MLE, the data were also tested for normality. The results showed that the absolute values of the skewness of variables in the model were all less than 2, which was lower than the reference value of 3; the absolute values of the kurtosis were all less than 7, which was lower than the reference value of 8. Results can verify that the data distribution conforms to the normal distribution, and the MLE can be employed to examine the model. The MLE results are shown in Table 3, as the χ2/df of the model is 3.323, GFI (goodness-of-fit index) is 0.836, and AGFI (adjusted goodness-of-fit index) is 0.81, which are acceptable for the complexity of our model; and the rest of the indicators of RMSEA (root-mean-square error of approximation), CFI (Comparative Fit Index), NFI (normed-fit index), and IFI (incremental fit index) are all within the good standard. Therefore, CITC, the square root of the AVE, and MLE verify the discriminant validity among variables successfully. Another sensitive and reliable indicator is Heterotrait-Monotrait (HTMT) ratio, and our findings remained robust because all HTMT figures are lower than the required threshold figures of 0.80.

The measurement model results indicate that the model has adequate construct reliability, indicator reliability, convergence validity, and discriminant validity, and it conforms to the normal distribution. We can conclude that the constructs are statistically distinct and it is suitable for further structural model testing.

5.2 Structural model

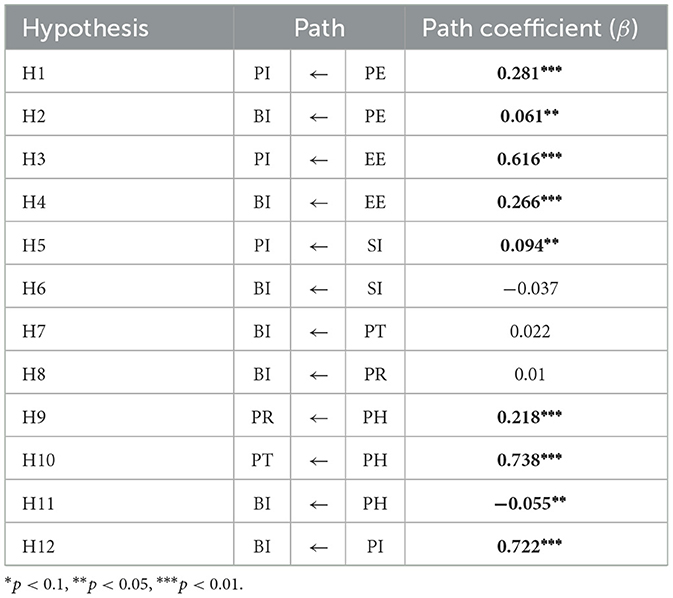

The structural model is the next step after confirming the measurement model, and it consists of three tests on path coefficients, mediation effects, and moderating effects (see Appendix). We analyze path coefficients (β) and p-values of proposed hypotheses, and the results are shown in Table 4. Simultaneously, we filled all results into Figure 3, and marked path coefficients for each hypothesis to visualize the result of the path analysis. Arrows using dashed lines mean this hypothesis is not supported by the test.

From the test results, personal innovativeness (PI), effort expectancy (EE), performance expectancy (PE), and personal humanlikeness (PH) were statistically significant in explaining behavioral intention; PE, EE, and SI were proved to have a positive effect on PI, this reveals that college students' innovativeness is under the influence of the effectiveness, convenience and other people around them using generative AI tools, and the ease of use of tools is more important. H6, H7, and H8 showed no statistical significance after the test, indicating that the effects of SI, PT, and PR were not supported by the data. At the same time, we found that H9 and H10 were verified by the data, namely, PH has a significant influence on students' PT and PR, this finding means that when students are aware of the human-like behavior of generative AI, it has a dual impact on their attitude toward it, and this feature foster more trust than fear among participants as H10 has a higher path coefficient compared to H9.

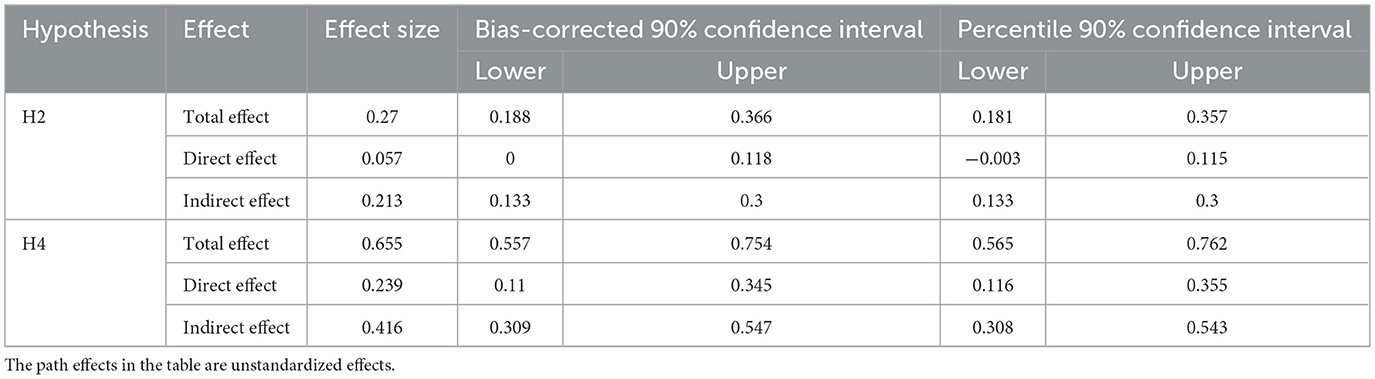

We analyzed the mediation effect of PI using the Bootstrap resampling method (Fornell and Larcker, 1981) for a comprehensive evaluation of the structural model, and PI is estimated to have mediation effects on PE-BI and EE-BI. After the estimation with 1,000 iterations of resampling, the results are summarized in Table 5.

By analyzing the path between PE and BI, it was found that the bias-corrected 90% confidence interval and 90% percentile confidence interval of the total effect did not contain 0, proving that the total effect between PE and BI was significant, with the effect size of 0.27; The bias-corrected 90% confidence interval and 90% percentile confidence interval of the direct effect contained 0, i.e., the direct effect between PE and BI does not exist; The bias-corrected 90% confidence interval and 90% percentile confidence interval of the indirect effect did not contain 0, i.e., the indirect effect between PE and BI exists. The analysis illustrates the full mediation effect of PI on the path between PE and BI.

By analyzing the path between EE and BI, it was found that the bias-corrected 90% confidence interval and 90% percentile confidence interval of the total effect did not contain 0, proving that the total effect between PE and BI was significant, with the effect size of 0.655; the bias-corrected 90% confidence interval and 90% percentile confidence interval of the direct effect and the indirect effect did not contain 0, i.e., the direct effect and the indirect effect both have significance. The analysis shows the partial mediation effect of PI on the path between EE and BI.

6 Discussion

6.1 Determinants from original UTAUT model

Among the three variables of PE, EE, and SI in the UTAUT model, PE and EE was found to have a significant positive impact on BI, which aligns with similar research on Pakistani university students (Shahzad et al., 2025). In contrast, SI did not exhibit significant effects, indicating that college students' perceived proficiency in using generative AI tools significantly and positively influences their willingness to adopt these tools. It is reasonable to speculate that PE and EE's positive impact on BI is partly mediated through PI based on our examination, because extant literature has elucidated that the assistance of GAI can improve the education outcomes of students in different scales and contexts, which could lead to higher motivation (Lo et al., 2025; Chiang et al., 2025). SI also failed to predict BI in another similar study conducted among UK students (Siu and White, 2025), suggesting that this item needs different measurements for the use behavior of GAI.

Although PE exhibited a positive effect on BI, this impact was not statistically significant, and some studies reached the same results (Utomo et al., 2021). SI demonstrated a negative effect on BI. This finding is contrary to the classic UTAUT hypothesis, but similar to a previous study on the use of e-wallets (Tusyanah et al., 2021), and some studies also found this variable to be non-significant (Abbad, 2021). A potential explanation is that as more institutional instructions and regulations are introduced, the endorsement from institutions and lecturers may play a more crucial role in the adoption of GAI among college students, which results in the increased weight of “perceived pedagogical fit” and the diminishing influence of peers and media (Lo et al., 2025; Chiu et al., 2024). Consequently, measurement instruments should be refined to capture this specific institutional influence rather than focusing on the traditional concept of trust if that is the case.

6.2 Extended determinants

The model analysis shows that the PH has a significant effect, while the PT and PR have no significant impact on the BI. As a unique feature in the field of AI, PH has a good explanatory power in the current study, which shows the necessity of introducing this determinant. Contrary to this study's hypothesis, PH was verified to exert a negative effect on BI. It is also noteworthy that PH shows positive effects on both PT and PR after the test, which illustrates the complex and contradictory attitudes of the users, and offers a more in-depth understanding of anthropomorphism than a simple relation with trust by extant research in Korea (Kim et al., 2025). More nuanced research emphasized the importance of mixed solutions, i.e., GAI teaching assistance under the supervision of teachers, on enhancing students' motivation (Neji et al., 2023; Chan et al., 2024). Our results support the effectiveness of human-AI collaboration from the opposite side.

The test validated the positive effect of PI on the BI, and its path coefficient (β) reached 0.772, which is very significant. This is completely consistent with the definition and assumption that people with innovative traits are more eager to try new technologies such as generative AI services. The H13 that DE will have the moderating effect on the path between PI and BI was not verified, this indicates that the role of PI in promoting the intention to use generative AI tools is not moderated by DE In particular, our study confirmed the positive effects of PE and EE on PI. It appears that good experience and result feedback make innovative behavior (in this study, using generative AI tools) valuable and conducive to college students to complete tasks, and effortless usage also lowers the barrier to innovation. These two possible factors likely work in concert to stimulate users' innovative motivation and activate their inherent innovative traits.

6.3 Other findings

This study also conducted a moderation effect test (see Appendix B), taking gender and educational background as control variables, and launched the moderating effect test based on acquired data to examine if the two variables have a significant effect on other variables. According to our report, different attitudes and motivations of college students exist toward the use of generative AI tools. However, it is still reasonable to study it as a whole.

7 Conclusion

This study refines the classical UTAUT model, thereby constructing a model that can better describe the use behavior of generative AI tools by introducing variables such as PH and PR. The proposed model was validated and refined by using quantitative analysis methods with the data acquired from Chinese college students, and it provides novel insights into factors driving university students' behavioral intention to use GAI. The results suggest that EE and PI have the most significant positive effect on BI, and PE also has an effect on willingness to use through the mediation of PI. Our analysis confirms the key facilitating factors behind GAI behavioral intentions.

Notably, some of the hypotheses from the classic UTAUT model failed to be proved in the structural model evaluation, such as H2 and H6. Among the extended variables in the current study, the test shows that the positive effects of PH, PT, and PR on BI, and the moderating effect of DE do not have statistical significance. This finding rejects the effectiveness of education replacing teachers with GAI tutors and appeals for a balance between human and AI in the education sector. However, more in-depth research on this point needs to be conducted. Furthermore, the college students' attitude toward GAI is illuminated by the results here, as PH both increased PT and PR.

Given our findings, being easy-to-use and productive remain key features for attracting college users, and most of the current GAI models adopt a user-friendly design and an interaction way similar to instant messaging software. For universities that are ambitious in promoting GAI among students, it is necessary to strike a balance between teaching staff and AI assistants, and to explore integrations with existing teaching resources, thus attracting students with performance and pedagogical fit. Simultaneously, both universities and technology companies should act cautiously regarding the issue of humanlikeness, as our study reveals that student attitudes are ambivalent and that PH can adversely influence motivation to use.

This study also has limitations that need to be addressed. More appropriate solution to verify CB-SEM sample adequacy and introducing more effective variance mitigation methods is still necessary. The number of participants in our survey is limited, and the heterogeneity of samples is not adequately considered since most of them are from Chinese universities. Previous research mentioned that individuals' cultural background can influence people's predispositions to anthropomorphize (Ruijten et al., 2019), and it might affect the determinant of PH. For further studies, we suggest including a larger and more culturally diverse participant pool, which might provide more generalizable and nuanced insights.

Data availability statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/Supplementary material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Ethics statement

The studies involving humans were approved by Research Ethical Committee of Central South University. The studies were conducted in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. The participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study. Written informed consent was obtained from the individual(s) for the publication of any potentially identifiable images or data included in this article.

Author contributions

CC: Supervision, Writing – review & editing, Conceptualization, Formal analysis, Methodology, Project administration, Resources, Writing – original draft. ZL: Data curation, Formal analysis, Investigation, Validation, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. MN: Supervision, Writing – review & editing. FL: Funding acquisition, Supervision, Writing – review & editing. CL: Supervision, Writing – review & editing, Funding acquisition.

Funding

The authors declare that financial support was received for the research and/or publication of this article. This work was supported by: The 2025 General Project of MOE (Ministry of Education) Foundation on Humanities and Social Sciences: research on Ideological Risk Identification and Prevention in University Networks Based on Multimodal Large Model (Grant No.: 25YJCZH007); The 2025 Hunan Provincial Higher Education Ideological and Political Work Research Project: Research on Network Information Risks and Governance Strategies Caused by Generative Artificial Intelligence (Grant No. 25A01); The 2025 Hunan Provincial Postgraduate Scientific Research and Innovation Project: Research on the Temporal Thematic Correlation and Evolutionary Path of Ideological Security Risks Induced by Generative AI (Grant No.: CX20250001); The 2024 Hunan Provincial Higher Education Ideological and Political Work Research Project: Identification and Governance Simulation of Network Ideological Security Risks in Higher Education Institutions under Multi-Source Data Fusion (Grant No.: 24A03); Key Project of Hunan Provincial “14th Five-Year Plan” on Educational Science: Research on the Evolution of Internet Public Opinion and Emergency Response Mechanism in Colleges and Universities (Grant No.: XJK22ZDJD18).

Acknowledgments

Authors would also like to appreciate PENG Chuyun for her assistance in modeling, and all suggestions from reviewers, all of which improve the quality of our manuscript enormously.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The author(s) declare that Gen AI was used in the creation of this manuscript. Authors used Gemini 2.5 and DeepSeek R1 during the preparation of this article to improve language only, and we confirm that we have reviewed and edited the content as needed and we are fully responsible for the publication.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Publisher's note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Supplementary material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/feduc.2025.1673150/full#supplementary-material

References

Abbad, M. M. (2021). Using the UTAUT model to understand students' usage of e-learning systems in developing countries. Educ. Inf. Technol. 26, 7205–7224. doi: 10.1007/s10639-021-10573-5

Alasadi, E. A., and Baiz, C. R. (2023). GAI in education and research: opportunities, concerns, and solutions. J. Chem. Educ. 100, 2965–2971. doi: 10.1021/acs.jchemed.3c00323

Alqahtani, T., Badreldin, H. A., Alrashed, M., Alshaya, A. I., Alghamdi, S. S., bin Saleh, K., et al. (2023). The emergent role of artificial intelligence, natural learning processing, and large language models in higher education and research. Res. Soc. Admin. Pharm. 19, 1236–1242. doi: 10.1016/j.sapharm.2023.05.016

Al-Saedi, K., Al-Emran, M., Ramayah, T., and Abusham, E. (2020). Developing a general extended UTAUT model for M-payment adoption. Technol. Soc. 62:101293. doi: 10.1016/j.techsoc.2020.101293

Anderson, J. C., and Gerbing, D. W. (1988). Structural equation modeling in practice: a review and recommended two-step approach. Psychol. Bull. 103:411. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.103.3.411

Baidoo-Anu, D., and Ansah, L. O. (2023). Education in the era of generative artificial intelligence (AI): understanding the potential benefits of ChatGPT in promoting teaching and learning. J. AI 7, 52–62. doi: 10.61969/jai.1337500

Baptista, G., and Oliveira, T. (2015). Understanding mobile banking: the unified theory of acceptance and use of technology combined with cultural moderators. Comput. Human Behav. 50, 418–430. doi: 10.1016/j.chb.2015.04.024

Barclay, D. W., Thompson, R., and Higgins, C. (1995). The partial least squares (PLS) approach to causal modeling: Personal computer use as an illustration. Technol. Stud. 2, 285–309.

Bates, T., Cobo, C., Mariño, O., and Wheeler, S. (2020). Can artificial intelligence transform higher education? Int. J. Educ. Technol. Higher Educ. 17, 1–12. doi: 10.1186/s41239-020-00218-x

Bauer, R. A. (1967). Consumer behavior as risk taking. Market. Crit. Perspect. Business Manage. 593, 13–21.

Bhagat, R., and Sambargi, S. (2019). Evaluation of personal innovativeness and perceived expertise on digital marketing adoption by women entrepreneurs of micro and small enterprises. Int. J. Res. Anal. Rev. 6, 338–351. Available online at: http://www.ijrar.org/IJRAR19J2947.pdf

Chan, C. K. Y., and Tsi, L. H. (2024). Will generative AI replace teachers in higher education? A study of teacher and student perceptions. Stud. Educ. Eval. 83:101395. doi: 10.1016/j.stueduc.2024.101395

Chan, S., Lo, N., and Wong, A. (2024). Generative AI and essay writing: impacts of automated feedback on revision performance and engagement. Reflections 31, 1249–1284. doi: 10.61508/refl.v31i3.277514

Chen, C., Wu, Z., Lai, Y., Ou, W., Liao, T., and Zheng, Z. (2023). Challenges and remedies to privacy and security in AIGC: exploring the potential of privacy computing, blockchain, and beyond. arXiv preprint arXiv:2306.00419.

Chen, X., Hu, Z., and Wang, C. (2024). Empowering education development through AIGC: a systematic literature review. Educ. Inf. Technol. 29, 17485–17537. doi: 10.1007/s10639-024-12549-7

Chi, O. H., Denton, G., and Gursoy, D. (2020). Artificially intelligent device use in service delivery: a systematic review, synthesis, and research agenda. J. Hospital. Market. Manage. 29, 757–786. doi: 10.1080/19368623.2020.1721394

Chiang, Y. H., Huang, C. S., Hung, L. S., and Huang, T. C. (2025). Enhancing enterprise resource planning learning through generative AI teaching assistants: a motivation-opportunity-ability perspective. Innov. Educ. Teach. Int. 62, 1447–1466. doi: 10.1080/14703297.2025.2533390

Chidambaram, V., Chiang, Y. H., and Mutlu, B. (2012). “Designing persuasive robots: how robots might persuade people using vocal and nonverbal cues,” in Proceedings of the Seventh Annual ACM/IEEE International Conference on Human-Robot Interaction (New York, NY: Association for Computing Machinery), 293–300. doi: 10.1145/2157689.2157798

Chiu, T. K., Moorhouse, B. L., Chai, C. S., and Ismailov, M. (2024). Teacher support and student motivation to learn with Artificial Intelligence (AI) based chatbot. Interactive Learn. Environ. 32, 3240–3256. doi: 10.1080/10494820.2023.2172044

Churchill, G. A. (1979). A paradigm for developing better measures of marketing constructs. J. Market. Res. 16, 64–73. doi: 10.1177/002224377901600110

Dai, J., Zhang, X., and Wang, C. (2024). A meta-analysis of learners' continuance intention toward online education platforms. Educ. Inf. Technol. 29, 21833–21868. doi: 10.1007/s10639-024-12654-7

Davis, F. D. (1989). Perceived usefulness, perceived ease of use, and user acceptance of information technology. MIS Q. 319–340. doi: 10.2307/249008

DeVellis, R. F. (2003). Scale Development: Theory and Applications, 2nd Edn. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications.

Diao, Y., Li, Z., Zhou, J., Gao, W., and Gong, X. (2024). A meta-analysis of college students' intention to use generative artificial intelligence. arXiv preprint arXiv:2409.06712. doi: 10.48550/arXiv.2409.06712

du Boulay, B. (2016). Artificial intelligence as an effective classroom assistant. IEEE Intell. Syst. 31, 76–81. doi: 10.1109/MIS.2016.93

Du, L., and Lv, B. (2024). Factors influencing students' acceptance and use generative artificial intelligence in elementary education: an expansion of the UTAUT model. Educ. Inf. Technol. 29, 24715–24734. doi: 10.1007/s10639-024-12835-4

Dwivedi, Y. K., Rana, N. P., Jeyaraj, A., Clement, M., and Williams, M. D. (2019). Re-examining the unified theory of acceptance and use of technology (UTAUT): towards a revised theoretical model. Inf. Syst. Front. 21, 719–734. doi: 10.1007/s10796-017-9774-y

Feuerriegel, S., Hartmann, J., Janiesch, C., and Zschech, P. (2024). Generative AI. Business Inf. Syst. Eng. 66, 111–126. doi: 10.1007/s12599-023-00834-7

Fornell, C., and Larcker, D. (1981). Evaluating structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error. J. Market. Res. 18, 39–50. doi: 10.1177/002224378101800104

Glikson, E., and Woolley, A. W. (2020). Human trust in artificial intelligence: review of empirical research. Acad. Manage. Ann. 14, 627–660. doi: 10.5465/annals.2018.0057

Global Education Monitoring Report Team (2023). Global Education Monitoring Report, 2023: Technology in Education: A Tool on Whose Terms? Available online at: https://unesdoc.unesco.org/ark:/48223/pf0000386165 (Accessed November 8, 2024).

Hair, J. F., Black, W., Babin, B. J., and Anderson, R. E. (2010). Multivariate Data Analysis: A Global Perspective. Pearson Education.

Hair, J. F., Sarstedt, M., Ringle, C. M., and Mena, J. A. (2012). An assessment of the use of partial least squares structural equation modeling in marketing research. J. Acad. Market. Sci. 40, 414–433. doi: 10.1007/s11747-011-0261-6

Hu, S., Laxman, K., and Lee, K. (2020). Exploring factors affecting academics' adoption of emerging mobile technologies-an extended UTAUT perspective. Educ. Inf. Technol. 25, 4615–4635. doi: 10.1007/s10639-020-10171-x

Jaboob, M., Hazaimeh, M., and Al-Ansi, A. M. (2025). Integration of GAI techniques and applications in student behavior and cognitive achievement in Arab higher education. Int. J. Hum. Comput. Interact. 41, 353–366. doi: 10.1080/10447318.2023.2300016

Kanbach, D. K., Heiduk, L., Blueher, G., Schreiter, M., and Lahmann, A. (2024). The GenAI is out of the bottle: generative artificial intelligence from a business model innovation perspective. Rev. Managerial Sci. 18, 1189–1220. doi: 10.1007/s11846-023-00696-z

Kang, E., and Kang, Y. A. (2024). Counseling chatbot design: the effect of anthropomorphic chatbot characteristics on user self-disclosure and companionship. Int. J. Human Comput. Interaction 40, 2781–2795. doi: 10.1080/10447318.2022.2163775

Khanfar, A. A., Kiani Mavi, R., Iranmanesh, M., and Gengatharen, D. (2024). Determinants of artificial intelligence adoption: research themes and future directions. Inf. Technol. Manage. 1–21. doi: 10.1007/s10799-024-00435-0

Kim, D., Kim, S., Kim, S., and Lee, B. H. (2025). Generative AI characteristics, user motivations, and usage intention. J. Comput. Inf. Syst. 1–16. doi: 10.1080/08874417.2024.2442438

Kim, J., Kang, S., and Bae, J. (2022). Human likeness and attachment effect on the perceived interactivity of AI speakers. J. Bus. Res. 144, 797–804. doi: 10.1016/j.jbusres.2022.02.047

Konya-Baumbach, E., Biller, M., and Von Janda, S. (2023). Someone out there? A study on the social presence of anthropomorphized chatbots. Comput. Human Behav. 139:107513. doi: 10.1016/j.chb.2022.107513

Kshetri, N. (2023). The future of education: generative artificial intelligence's collaborative role with teachers. IT Prof. 25, 8–12. doi: 10.1109/MITP.2023.3333070

Lee, M. C. (2009). Factors influencing the adoption of internet banking: an integration of TAM and TPB with perceived risk and perceived benefit. Electron. Commer. Res. Appl. 8, 130–141. doi: 10.1016/j.elerap.2008.11.006

Leschanowsky, A., Rech, S., Popp, B., and Bäckström, T. (2024). Evaluating privacy, security, and trust perceptions in conversational AI: a systematic review. Comput. Human Behav. 159:108344. doi: 10.1016/j.chb.2024.108344

Lo, N., Chan, S., and Wong, A. (2025). Evaluating teacher, AI, and hybrid feedback in English language learning: impact on student motivation, quality, and performance in Hong Kong. SAGE Open 15:21582440251352907. doi: 10.1177/21582440251352907

Mahmud, H., Islam, A. N., Luo, X. R., and Mikalef, P. (2024). Decoding algorithm appreciation: unveiling the impact of familiarity with algorithms, tasks, and algorithm performance. Decis. Support Syst. 179:114168. doi: 10.1016/j.dss.2024.114168

Neji, W., Boughattas, N., and Ziadi, F. (2023). Exploring new AI-based technologies to enhance students' motivation. Iss. Informing Sci. Inf. Technol. 20, 95–110. doi: 10.28945/5149

Nestor, M., Fattorini, L., Perrault, P., Parli, V., Reuel, A., Brynjolfsson, E., et al. (2024). The AI Index 2024 Annual Report. AI Index Steering Committee, Institute for Human-Centered AI, Stanford University. Available online at: https://hai.stanford.edu/ai-index/2024-ai-index-report

Oye, N. D., Iahad, N. A., and Rahim, N. A. (2014). The history of UTAUT model and its impact on ICT acceptance and usage by academicians. Educ. Inf. Technol. 19, 251–270. doi: 10.1007/s10639-012-9189-9

Park, J., Woo, S. E., and Kim, J. (2024). Attitudes towards artificial intelligence at work: scale development and validation. J. Occup. Org. Psychol. 97, 920–951. doi: 10.1111/joop.12502

Patil, P., Tamilmani, K., Rana, N. P., and Raghavan, V. (2020). Understanding consumer adoption of mobile payment in India: extending Meta-UTAUT model with personal innovativeness, anxiety, trust, and grievance redressal. Int. J. Inf. Manage. 54:102144. doi: 10.1016/j.ijinfomgt.2020.102144

Ruijten, P. A., Haans, A., Ham, J., and Midden, C. J. (2019). Perceived human-likeness of social robots: testing the Rasch model as a method for measuring anthropomorphism. Int. J. Soc. Robot. 11, 477–494. doi: 10.1007/s12369-019-00516-z

Schei, O. M., Møgelvang, A., and Ludvigsen, K. (2024). Perceptions and use of AI chatbots among students in higher education: a scoping review of empirical studies. Educ. Sci. 14:922. doi: 10.3390/educsci14080922

Schillewaert, N., Ahearne, M. J., Frambach, R. T., and Moenaert, R. K. (2005). The adoption of information technology in the sales force. Indus. Market. Manage. 34, 323–336. doi: 10.1016/j.indmarman.2004.09.013

Seok, J., Lee, B. H., Kim, D., Bak, S., Kim, S., Kim, S., et al. (2025). What emotions and personalities determine acceptance of generative AI?: focusing on the CASA paradigm. Int. J. Hum. Comput. Interact. 41, 1–23. doi: 10.1080/10447318.2024.2443263

Sergeeva, O. V., Zheltukhina, M. R., Shoustikova, T., Tukhvatullina, L. R., Dobrokhotov, D. A., and Kondrashev, S. V. (2025). Understanding higher education students' adoption of generative AI technologies: an empirical investigation using UTAUT2. Contemp. Educ. Technol. 17:ep571. doi: 10.30935/cedtech/16039

Shahzad, M. F., Xu, S., and Asif, M. (2025). Factors affecting generative artificial intelligence, such as ChatGPT, use in higher education: an application of technology acceptance model. Br. Educ. Res. J. 51, 489–513. doi: 10.1002/berj.4084

Shaper, L. K., and Pervan, G. P. (2007). ICT and OTS a model of information and communication technology acceptance and utilizations by occupational therapist. Int. J. Med. Inform. 76, 212–221. doi: 10.1016/j.ijmedinf.2006.05.028

Sharma, S. K., and Sharma, M. (2019). Examining the role of trust and quality dimensions in the actual usage of mobile banking services: an empirical investigation. Int. J. Inf. Manage. 44, 65–75. doi: 10.1016/j.ijinfomgt.2018.09.013

Siu, B., and White, J. (2025). When ease becomes a barrier: what influences student intentions to use generative AI in higher education? Br. Educ. Res. J. 1–27. doi: 10.1002/berj.4206

Stojanov, A. (2023). Learning with ChatGPT 3.5 as a more knowledgeable other: an autoethnographic study. Int. J. Educ. Technol. Higher Educ. 20:35. doi: 10.1186/s41239-023-00404-7

Strzelecki, A., and ElArabawy, S. (2024). Investigation of the moderation effect of gender and study level on the acceptance and use of generative AI by higher education students: comparative evidence from Poland and Egypt. Br. J. Educ. Technol. 55, 1209–1230. doi: 10.1111/bjet.13425

Sun, L., and Zhou, L. (2024). Does generative artificial intelligence improve the academic achievement of college students? A meta-analysis. J. Educ. Comput. Res. 62, 1676–1713. doi: 10.1177/07356331241277937

Turel, O., and Kalhan, S. (2023). Prejudiced against the machine? Implicit associations and the transience of algorithm aversion. MIS Q. 47, 1369–1394. doi: 10.25300/MISQ/2022/17961

Tusyanah, T., Wahyudin, A., and Khafid, M. (2021). Analyzing factors affecting the behavioral intention to use e-wallet with the UTAUT model with experience as moderating variable. J. Econ. Educ. 10, 113–123. Available online at: https://journal.unnes.ac.id/sju/jeec/article/download/44824/18178

Twum, K. K., Ofori, D., Keney, G., and Korang-Yeboah, B. (2022). Using the UTAUT, personal innovativeness and perceived financial cost to examine student's intention to use E-learning. J. Sci. Technol. Policy Manage. 13, 713–737. doi: 10.1108/JSTPM-12-2020-0168

Ustun, A. B., Karaoglan-Yilmaz, F. G., Yilmaz, R., Ceylan, M., and Uzun, O. (2024). Development of UTAUT-based augmented reality acceptance scale: a validity and reliability study. Educ. Inf. Technol. 29, 11533–11554. doi: 10.1007/s10639-023-12321-3

Utomo, P., Kurniasari, F., and Purnamaningsih, P. (2021). The effects of performance expectancy, effort expectancy, facilitating condition, and habit on behavior intention in using mobile healthcare application. Int. J. Community Serv. Engage. 2, 183–197. doi: 10.47747/ijcse.v2i4.529

Venkatesh, V., Morris, M. G., Davis, G. B., and Davis, F. D. (2003). User acceptance of information technology: toward a unified view. MIS Q. 27, 425–478. doi: 10.2307/30036540

Venkatesh, V., Thong, J. Y., and Xu, X. (2012). Consumer acceptance and use of information technology: extending the unified theory of acceptance and use of technology. MIS Q. 36, 157–178. doi: 10.2307/41410412

Wang, C., Wang, H., Li, Y., Dai, J., Gu, X., and Yu, T. (2025). Factors influencing university students' behavioral intention to use generative artificial intelligence: integrating the theory of planned behavior and AI literacy. Int. J. Hum. Comput. Interact. 41, 6649–6671. doi: 10.1080/10447318.2024.2383033

Wrycza, S., Marcinkowski, B., and Gajda, D. (2017). The enriched UTAUT model for the acceptance of software engineering tools in academic education. Inf. Syst. Manage. 34, 38–49. doi: 10.1080/10580530.2017.1254446

Keywords: UTAUT, generative AI tool, behavioral intention, college students, perceived humanlikeness

Citation: Cao C, Li Z, Ni M, Luo F and Ling C (2025) Will human-like features effect the adoption of generative AI tools? A study in Chinese University students. Front. Educ. 10:1673150. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2025.1673150

Received: 25 July 2025; Accepted: 08 September 2025;

Published: 05 December 2025.

Edited by:

Galina Ilieva, Plovdiv University “Paisii Hilendarski”, BulgariaReviewed by:

Dennis Arias-Chávez, Universidad Continental - Arequipa, PeruNoble Lo, Lancaster University, United Kingdom

Copyright © 2025 Cao, Li, Ni, Luo and Ling. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Chunyu Ling, NzA1MDc0QGNzdS5lZHUuY24=

†ORCID: Chao Cao orcid.org/0009-0009-8426-9827

Ziyu Li orcid.org/0009-0007-2536-6278

Chao Cao

Chao Cao Ziyu Li

Ziyu Li Mang Ni5

Mang Ni5 Chunyu Ling

Chunyu Ling