- Department of Education and Special Education, Faculty of Education, Gothenburg University, Gothenburg, Sweden

This study presents findings based on the observation of a United Nations role-play task in a plurilingual high school (age of students 16–19) where CLIL pedagogical approaches are practiced. The integration and scaffolding of course content in the subjects of International Relations, History, Social Studies and English is explored via examples of student language use in learners of English. Formal and informal examples of prepared as well as spontaneously produced speech have been collected in a specialized learner corpus and are being analyzed in reference to subject-literacy aims. This “game” provided a rich arena for students to practice skills such as public speaking and debate, negotiation, and the writing of texts such as resolutions, presentations of policy and reflections. Through this integrated approach to learning students further consolidated subject matter knowledge gained during study of the history of conflict in the Middle East, with new understandings of geopolitical interests via the policy precedents set by the nations studied, together with language suitable to express this knowledge. Furthermore, students developed arguments for or against perspectives, which they held regarding the conflict in question. This exercise illustrates integration of language and content learning with the potential for lasting and transformative learning outcomes, beyond assessment. It also provides an authentic example of simultaneous language learning and subject-literacy practices, responding directly to the question of how learning in L2 affects subject knowledge in this academic environment.

1 Introduction

Content and language integrated learning (CLIL) centers on both language and subject content aims. This necessitates placing the students in the center of the learning scenario, their background knowledge and language skills being key attributes on which to scaffold new subject knowledge. Subject-literacy is needed for subject content learning as students require not only the disciplinary language of a subject, but also knowledge of the texts and genres encountered in it, together with the patterns of language use students might expect to encounter. In academic environments where L1 is used for instruction, e.g., in the subjects of social studies or history, the relationship between language, literacy development, and subject matter acquisition may be taken for granted. Subject teachers in these environments may focus on subject specific learning outcomes, leaving language matters for language teachers (e.g., Snow et al., 1989). By contrast, in environments of content and language integration where the target language is a second language1 (L2) the inseparable nature of the relationship between subject content and language is unavoidable. Gaps present in a student’s language skills may make learning and demonstrating subject knowledge difficult. The acquisition of new subject content in an additional language may be a slower process, requiring more practice, and careful consideration of the best ways to connect with students’ previous knowledge (Walqui, 2006). Teaching exercises, adapted to address the needs of English language learners such as simulations, demonstrations or use of realia in subject teaching can address gaps by affording students varied opportunities for input of content (Walqui, 2006; Gibbons, 2002). Students may then build on what they have experienced in L2, by adding new language to their previous understanding of topics. The study which follows may be considered alongside the pedagogical framework of Pluriliteracies for Deeper Learning (PTDL), which emphasizes an ecological approach to sustainable literacy development (Coyle and Meyer, 2021). This approach advocates an explicit focus on textual fluency and being pluriliterate across text types, subject disciplines and languages (Coyle and Meyer, 2021). The students in the present study may be said to be engaging in activities which target sustainable subject-literacy outcomes. Subject-literacy (SL), a bridge between content and language knowledge in CLIL classrooms, will be looked at in its integration with English.

There is much yet to be learned about how students take in and demonstrate subject knowledge in a language other than L1. The present study, which employs classroom observation as one method of generating ethnographic linguistic data, aims to address this knowledge gap by providing an example of integrative classroom practices. A dual focused approach to language and subject content acquisition (Mehisto et al., 2008) was observed during a United Nations Role-play (UNRP) task in a course in International Relations (IR). In the course, students developed content knowledge related to the ongoing conflict between Israel and Palestine in preparation for a RP simulation which mirrored the acting United Nations Security Council. This study considers how a UNRP task has been used as an instrument for learning in a CLIL context. SL is defined here as the academic language, subject specific discourse, and genres which are used to present and/or demonstrate subject knowledge on the part of teacher or student, where language competence is a key factor.

The following questions related to SL outcomes are explored:

1. What are the potential contributions of role-play for the development of subject-literacy in an environment where language and content teaching are integrated?

2. What are the genre specific characteristics of the speeches presented by students during a model United Nations role-play?

3. How (in what way) do the disciplinary language choices in the speeches demonstrate subject specific knowledge of the conflict studied?

2 Pedagogical framework

2.1 Curricular content

The national steering documents produced by the Swedish National Agency for Education (Skolverket) provided course aims and assessment objectives for the observed International Relations (IR) course (Skolverket, 2012c). The course builds on a foundation of previous courses in history, social studies, and English (Skolverket, 2012a, 2012b, 2012c), aiming to further students’ knowledge by widening the discourse of these subjects, to include the subject specific language, concepts, and genres of IR. IR is an interdisciplinary subject (Asal, 2005; Skolverket, 2012c), drawing from other social sciences, which has implications for how subject vocabulary within the discipline is defined. The core course content deals with subject knowledge outcomes regarding theoretical perspectives within IR, such as cooperation between countries, causes of conflict, and challenges faced by state actors in an international arena (Skolverket, 2012c). The disciplinary language of this subject includes a base in historical language (see Coffin, 2006; Schleppegrell et al., 2008, 2004; Martin, 2013; Halliday, 1973); broadened by a disciplinary perspective which relates to topics such as geopolitical positions and hierarchies between nation-state actors, the interests of individuals, countries and organizations, law, conflict and cooperation. Of interest regarding the integration of subject content and language objectives in this course, is the mention of “oral and written presentations in different forms, […] such as debates, articles, scientific reports and essays” as being among the core content in the course (Skolverket, 2012c).

In most Swedish High School settings, Swedish is used for instruction and assessment of language and subject content objectives. There is no official CLIL syllabus in Sweden to address the integration of content and L2 language teaching when a language such as English is used in subject content instruction. However, the syllabus for the subject of English may be considered here as it includes relevant aspects such as the language of argumentation and exposure to subject texts of different genres (Skolverket, 2012a). Other content in the IR syllabus such as, e.g., the teaching of international law, does not directly mention language, however in practice this content requires an understanding and exposure to many varied and complex language structures and skills, as exemplified in the varied texts, which likely provide language challenges for L1 and L2 students alike. The disciplinary language of IR is both highly formulaic (e.g., as encountered in treaties and legal documents), and informal at times (e.g., negotiation in informal settings), requiring learners to flexibly employ a wide variety of language skills at many different levels of reception and production.

2.2 Role-play tasks in IR education

Role-Play has long been used in educational contexts to stimulate learner interest and mimic authentic scenarios to practice and demonstrate learning (Asal, 2005; Ellington et al., 1998). In “Playing Games with International Relations,” Asal develops pedagogy for using simulations to teach IR theory (2005). This work pinpoints the importance of finding a balance between fun and a focus on desired knowledge outcomes (Asal, 2005). Though RP is frequently used in language learning scenarios to mimic natural communication, its use in CLIL contexts to achieve subject-literacy aims is less documented. Language learners with lower levels of proficiency might role-play a telephone dialogue, or shop interaction in L2 to simulate an activity they hope to be successful doing outside of the classroom, while students with higher proficiency levels may similarly benefit from simulating scenarios of subject disciplinary communication, in anticipation of future professional usage. Thus, combined with pedagogical environments where subject content is taught in L2, RP offers integrated scaffolding of subject and language learning, creating opportunities for development through authentic use of language, in encounters with subject specific academic language.

The potential benefits of role-play in integrated learning scenarios include motivational aspects. If learners are involved in the practice of skills which directly relate to their perceptions of their ideal speaker selves, and/or professional environments in which they hope to use English in the future, they may be more invested in the learning outcome (Dörnyei and Ushioda, 2009; Henry et al., 2018). Indeed, if students are invested in the task at hand, through play, the enjoyment they experience in the task may facilitate desirable learning behaviors such as engagement and further practice. Sylvén and Thompson (2015) found there to be differences regarding motivation of language learners in CLIL and non CLIL environments in Sweden. Regarding game play, the concept of “the magic circle” (Salen and Zimmerman, 2004), a theoretical space inhabited by a player who is deeply immersed in a game, is interesting to consider in RP scenarios as they also have the potential for deep immersion and engagement from participants. Furthermore, in studies of STEM education, the use of immersive technologies such as augmented reality (AR) and virtual reality (VR), have been shown to positively affect engagement and performance (Tene et al., 2024). Related is the degree to which a real-world game simulation and immersive learning experiences may have the potential for similar benefits in L2 students.

3 Learning environment

Participating students attended the final term of a 3-year CLIL Social Science program aimed at further academic studies. More than half of the students2, 54%, identified as having more than two languages in their language repertoire. 4 of 18 students had English as their home language, though 61% of surveyed students used it as one of a few languages (including Swedish), spoken in the home. The country and context of participants’ educational backgrounds varied, some 40% of students had studied using a language other than Swedish in compulsory school. All subject content instruction during their high school education, except in modern languages and tuition in the Swedish language, was in English. The faculty in this setting is also bi/multilingual. The observed teachers had Swedish teaching accreditations within their subjects as well as multiple years of experience teaching in a CLIL setting.

3.1 The classroom teaching environment

The classroom learning which preceded the role-play took place on a weekly basis for 150 min in a block, roughly 100 h3 over the course of one academic year (2 terms). Units of study in the course included IR theory, international law, human rights, globalization and conflict resolution. Course assessment was based on written tasks which were submitted at the end of each unit of study, apart from written tasks completed in preparation for the RP. The RP itself was not assessed, though participation was mandatory. Assessed tasks included a study of the Israel Palestine conflict in relation to the specific country to be represented, a strategy document for each country/team and a formal conflict resolution. An after-action report was also submitted post-RP to evaluate learning outcomes and choices made by individual students during the RP in relation to the country portrayed. Tasks were supported by lectures on international actors and the UN body, digital content and power point presentations which were accessed via an online classroom portal, as well as by student research on the policies of various countries. A digital copy of an IR reference textbook was available, however lectures and power point materials created by the teacher, alongside relevant digital links to international bodies, such as the United Nations, provided the course content. There was a clear structure to the weekly lessons, each starting with approx. 20 min of students bringing forward news items of global relevance from the previous week, to be discussed. The teacher connected each mentioned item with its disciplinary relevance, contributing questions regarding the source of the item and international conflict perspectives or diplomatic aspects relate to the learning outcomes of the course. Lesson content in the form of a lecture or class activity to prepare for the RP then followed.

3.2 The UN role-play

The UN role-play took place during the spring term, however relevant subject knowledge needed for its completion is present from the beginning of the course, when historical perspectives on international relations are framed within the current geopolitical climate. The conflict topic was chosen by the students, followed by instruction on the UN, relevant charters, and the role of the security council. Students were then instructed on the RP itself and assigned to 1 of 15 member states. They then commenced learning the specifics of the chosen conflict and its relationship with the country being represented. Previous conflicts covered have included the civil war in Syria, the Iranian Nuclear Program, and the Myanmar conflict.

The aim of the present RP was to curb the cycle of violence in the escalating conflict between Israel and Palestine. Students were tasked with writing and passing a (UNSC) resolution. The materials used to guide the role-play task were developed by GR Utbildning, a regional group which focuses on supporting educational collaboration and training. These materials covered the rules for the task, with a large focus on the written language of resolution writing, by providing examples of language typical of the genre and instructing how to write a resolution (Utbildning, 2024). Students were guided in the writing of preamble and operative clauses through lists of subject relevant vocabulary. These took the form of active present tense verbs (e.g., authorizes, declares, urges) for use in the operative clauses, and participle phrases used in the preamble (e.g., acknowledging, expressing concern) to describe the problem a country wished to address alongside the measures suggested to address it (see example Supplementary material 1).

Four goals were also put forward by the teacher for the role-play task in alignment with the course aims, to gain:

a. a deeper understanding of how the UN and the Security Council (SC) work

b. knowledge of how the different countries in the SC act in the chosen conflict and their associated arguments

c. understanding of how diplomats act and the difficulties of reaching common decisions

d. to be able to analyze and propose a solution to the conflict in question

During both lesson time and homework, students researched the roots of the conflict, the historical, cultural and economic ties their country had with other member states, and the specific policy perspective of the country they were representing. Students were provided with links from UN proceedings and guidance on how to consider their countries’ perspective of the conflict. Lessons during the months prior to the RP were used for planning and background work necessary for students’ portrayal of their country and their development of a strategy for passing a resolution to resolve the conflict. Student teams4 wrote and submitted their resolution prior to the RP and presented it to other teams to gain signatories and support. These discussions often continued outside of lesson time.

On the day of the RP, students arrived at an auditorium where they were seated in alphabetical order, by country. In the front of the room there was a stage with a podium for speeches and a table for the secretariat, a teacher of social studies at the school and student secretary who noted motions to speak, changes to resolutions, and the results of votes. The RP simulation lasted 5 h, its conclusion, the result of a student vote. The participants dressed formally for the occasion and the serious nature of the conflict was reflected in the students’ portrayal of their roles.

The RP had the following central parts:

a. Start of session/opening speech

b. Formal debate consisting of unprepared speeches in promotion of a resolution

c. Informal debate consisting of sidebar discussions between individual representatives of different countries

d. Voting on resolutions

e. Closing the session: participants vote to end the session

After a brief talk welcoming students to the session, participating teams were invited to present an opening speech (approx. 2 min), which put forward policy perspectives, and established specific goals for the session (see example Supplementary material 2). This speech served as the first move in a game of chess; it was important to know not only what perspective to portray, but also to be able to predict the perspectives of fellow nations/teams. After the opening speeches, the secretariat recognized motions to speak during formal debate. This debate was either general or substantive; the former made space for all contributions, while the latter focused speeches on one resolution in consideration prior to a vote. Student teams (countries) then moved either to vote, shift to informal debate, to discuss another resolution, to limit the time for debate, or to end the session. Shorter unofficial breaks were taken during the informal debate; however, these were still very focused on the task. Informal debate consisted of sidebar discussions where students were able to meet with representatives of specific teams to discuss common interests and/or procure support for a specific resolution. Students voted on specific amounts of time for these informal debates; however, they ranged in time from 5–20 min. Roughly 2 of the 5 h spent in the role-play were in informal communication scenarios.

4 Results to date

All speeches made during the RP have been recorded, transcribed, and are being analyzed in a learner corpus. Speeches ranged in length from 30 s. to 4 min at the podium during each turn. All member states5, except two (n = 13), made an opening speech. Of the other vocalized interactions6 and speeches during the formal debate (n = 37), 12 of 15 participating countries made oral contributions to formal game play. These contributions varied in nature, some were motions, e.g., calls to vote or requests or the chair, while others were speeches.

In reference to the genre specific characteristics and patterns found, the speeches made were either argumentative or persuasive. Opening speeches established the actors’ objectives for the session and their policy perspectives. Later speeches made during the formal debate were identified as having the following aims. They were to:

1) present or support a resolution of another member state

2) defend a position after having been named by another team in debate

3) request information and/or clarification from another actor

4) offer clarification of a position

5) call out another member for their actions/beliefs/behavior

In contrast to the opening remarks, the speeches taking place during the formal debate were unprepared, as students needed to react to the content and motions put forward by other teams. These speeches can be said to be more representative of student language proficiency due to their spontaneous nature. They included more errors than the prepared remarks, however these errors did not generally impede communication. Many of the speeches included emotive language calling on arguments appealing to the listener demonstrating an understanding for how the classical rhetorical pillars of ethos, pathos and logos (Aristotle, 1991; e.g. Rocklage et al., 2018) may be employed when presenting information in this way. Generally, the tone was polite, including language which afforded respect to individual members/states, e.g., my dear delegates, honorable delegates, ladies and gentlemen of the security council. Some participants, however, made direct or indirect accusations of other countries drawing on logos and a factual basis in statistics as a means of persuading the audience, e.g., “We remind you that United States arms make up 40% of the world’s exports, and we ask you who benefits from not calling a ceasefire?” stated one representative. Still, other actors took to the podium to remind participants of the objective, “Japan believes that we should not be pointing fingers. We believe that we should be focusing on one of the main agendas of the United Nations.” This may be seen as behavior motivated by tactical choices used to pass a resolution, or by a deep (meta) understanding of the positioning of their represented country in this exercise; the later motivation being a more overt demonstration of subject learning.

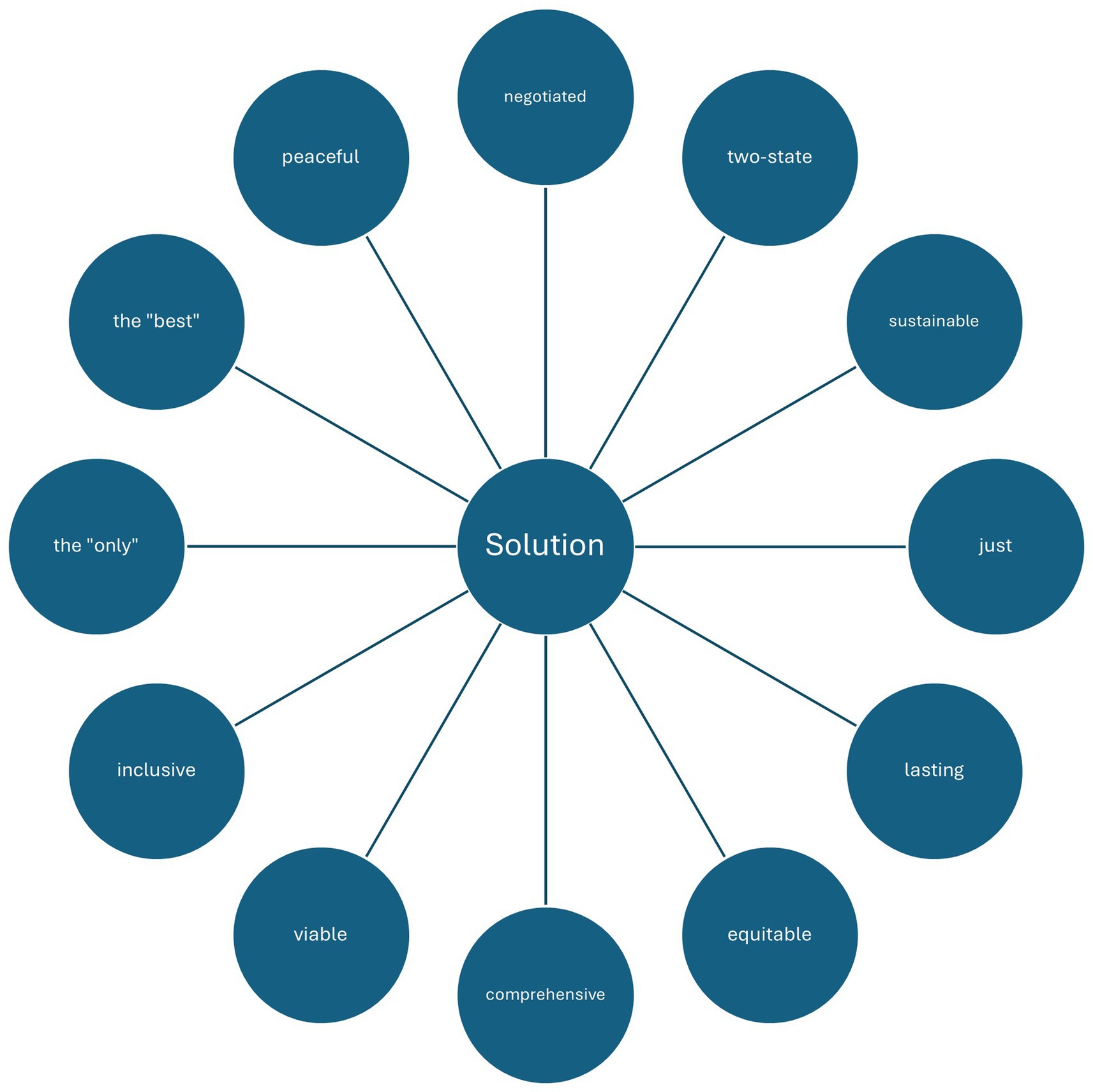

The breadth and variety of disciplinary language within the formal speeches varied and was most present in the pre-prepared opening remarks. However, ample examples of disciplinary vocabulary in the form of subject relevant collocations were seen in all transcribed speeches. Collocates of keywords such as conflict, solution, humanitarian, and ceasefire had functional roles, demonstrating both subject knowledge and language proficiency in their use (see Figure 1). The lexical cohesion (collocation) provided via language choices highlighted common goals and key differences shared between member states in the RP. These key nouns and the adjectives used to describe them presented the perspective of a specific country functioning as signposts of a member’s understanding of the conflict and position in reference to it. In Figure 1, collocates of the keyword solution from the student language in the RP are presented. These collocations contribute to subject-literacy through related discourse functions, communicated in their use. The best solution or the only solution as an expression of the stance (perspective) of a represented country, also communicates the so called ideational metafunctions of language, the mental processes engaged in by the students, which may be seen to demonstrate an understanding of the subject knowledge to be learned during this role-play task (e.g., Halliday, 1973; Halliday and Matthiessen, 2014; Martin and White, 2005). Interpersonal meaning between student participants is also communicated and shared by participants in the interaction itself, guided by the norms of language use in this CLIL environment, and between participating students and their teacher.

Consider the nuance in language use of, e.g., a two-state solution vs. an equitable solution as demonstrated in the transcribed concordance lines below:

…recognizing that sustainable peace can only be achieved through inclusive and equitable solutions that address the underlying causes of conflict. -Rep. of Russia.

…we strongly support that we come to this agreement at no expense of any more civilian lives, seizing the current moment to push for a two-state solution before opportunities to peace diminish further. -Rep. of Malta.

The foreign policy agendas of the two countries represented above are quite different. The choice represented in using solution in one way over the other, while on the surface seeming only to present state policy, is also indicative of a nuanced linguistic choice by an individual with a battery of language choices in their repertoire for use depending on what they wish to communicate. An equitable solution may or may not be a two-state solution. Language choices signaled a team’s stance and positioning in the RP (however ambiguous or shifting), knowledge of the conflict in question, and room for negotiation. The advanced language skills demanded by this exercise, combined with the subject knowledge needed in the positioning of the interests of state actors, were also at times in conflict with students’ personal views on the conflict. This tension appears to have been offset by students’ deep engagement in the RP task. Students demonstrated high levels of proficiency, communication and subject literacy. The language used during RP was communicative and largely fluent and students remained faithful to their assigned roles. A case which speaks to the level of student engagement was a student who admitted that on the day prior to the RP he strategically distanced himself from a friend, to avoid being asked to make promises of support for a resolution he knew he should not support in accordance with the foreign policy of his chosen country.

Another grammatical feature noted in the speeches was the use of pronouns together with specific verbs to present state policy (e.g., we believe, think, stand for, recognize) vs. our shared goals. Stance markers of identification and posturing statements e.g., as representatives of Albania, or we the country of x believe, as x we believe, we stand with y; of a countries’ policy perspective were common and served to open doors to negotiations by signaling perspectives and where there might be room for negotiation or agreement. This posturing was exaggerated at times, perhaps to make clear the students’ understanding of the foreign policy which they represented, but also to signal opportunities for collaboration. It also served to reinforce the nature of the task, supporting the importance of the objective to find a possible solution to the conflict.

Important interactional language contributions also came in the form of informal debate. It was impossible to record this interaction due to limitations of access, though collected informal memos have provided important insights into the role of this type of communication in the activity. These memos included shorter emphatic statements, e.g., we will sign it now and direct questions, like what is your response to our request? Considered together with reflections from participant interviews, these communiques suggest that informal avenues of negotiation played an integral part in the outcome of the RP. Some teams relied to a larger degree on writing memos as compared to speaking to the entire group at the podium. The example of Malta is a case in point, as they made only one contribution to the formal debate, yet their resolution was the first to pass a vote in the SC. Interviewed representatives of Malta, spoke of their communication strategy describing building a bond between countries during informal discussions and feeling like a key player in the action. The example of Malta in the exercise, further highlights the different levels of communication necessary and the variety of formats in the practice of this task.

5 Discussion

In this study I have explored how subject-literacy is developed through CLIL targeting L2 English in a plurilingual high school setting. The deep integration of language aims and literacy outcomes in the class observed, as viewed in the larger context of the program of studies, leads me to reflect on implicit and explicit course/program alignment in the language and subject-literacy outcomes. The choice of conflict covered was the will of the students expressed via a series of proposals and subsequent voting. This conflict had also been studied the year prior over several months as a part of a course in history. In this way, students were able to build on their knowledge, adding to it from the perspective of subject-specific content studied in IR. New elements of the conflict were also unfolding at the same time as preparations for the RP were taking place, and students were able to immediately engage with these developments as they already possessed background knowledge. Subject-literacy through English may be viewed in the framework of Vygotskian cyclical knowledge building (Vygotskij et al., 1987). In the enactment of this role-play, many elements of curricular alignment and newly learned knowledge built on previous academic exposure to the conflict topic in other adjacent disciplines studied (history, social studies, economics, political science). This was also noted in the form of the specific English language input needed to complete the role-play. Some students had studied extra courses in academic language and rhetorical skills which they expressed were of great help during this task, especially when it came to how to formulate a persuasive argument in speech.

The task itself, as combined with the pedagogical implications of the use of English in this learning environment with its multilingual students, in combination with the reiterative curricular content promoted an impactful learning outcome for students. The hard work, immersion in the subject specific language of the task, and both controlled and freer practice stemming from the different genres and types of texts produced in both the preparation for and evaluation of the task contributed to the integration of language and subject knowledge outcomes. Though interviewed teachers of subject knowledge in this study did not see themselves as language teachers, they act as de facto teachers of language as regards the literacy development of students in English. Furthermore, in practice the dialogic methods (e.g., Sybing, 2023) employed in the classroom environment provided a space for varied and open language input in which students are immersed in English over the course of their studies. The IR teacher reflected on the value of “small daily conversations” on key topics in his class, as did the students. These conversations over the course of tuition during the course, and perhaps their tenure as students at the school, have provided an immersive environment providing examples of language in context.

Owing to the international experiences and backgrounds of students in the group, a few had real world connections to this conflict. This might have been viewed as a reason for concern, out of fear that a divisive topic and active conflict was to be discussed. The international background and perspectives of students was instead viewed as valuable resource, as students were challenged to understand the conflict, and the reasons for their own perspectives in new ways. They were often called upon to share their personal experience within classroom content, giving it status and a currency of importance in the classroom. A connection with the topic, be it through learned knowledge (i.e., interactional identity), or personal experiences (i.e., transportable identity) (Henry et al., 2018; Zimmerman, 2014), required students at times to argue perspectives that they did not believe in, in a convincing way. The exercise of doing this is complex (and valuable) from both a language and subject-literacy perspective, as students must internalize what is necessary to convince others of an opinion, phrasing it in language appropriately, and in so doing they must understand the hinderances that others face in coming to an agreement on a specific point. What are the relevant historical and policy perspectives which shape the behaviors of international actors? To be able to do this in L2 adds yet another hurdle to this task. On this topic, one student reflected, “being in a scenario where you are not yourself, you need to put all that aside and look at it from the bias of an entire nation. I think that kind of pushed me towards more formal language.” Another participant reflected, “Our main goal when communicating with people wasn’t to get our way; it was to get their way,” a comment which highlights the communicative action together with the subject knowledge necessary to complete the task.

The multilingual profile of the students in the school also made it interesting to consider in the use of English in a Swedish context. In the exercise of a UNRP, participants shared a multilingual identity and background like the acting UN body, adding an interesting element of verisimilitude to the classroom exploration of this task. This affords students the opportunity to consider the language use of other, similar, multilingual speakers of English on which to model their own performances, offering an alternative ideal of spoken English to consider in their learning (Hüttner and Smit, 2017). This environment also affords students the opportunity to practice comprehension of spoken English daily with speakers who have a variety of accents in English, in promotion of the value of global Englishes (Jeong et al., 2021; Clyne and Sharifian, 2008). The international backgrounds of the students also contribute considerably to the subject learning on the course as students were observed to draw from and share their own experiences in different geographic parts of the world. This can be noted in the richness of expression in the language of their speeches and the knowledge brought forward for discussion in the course content. On the topic of international English one student reflected, “you speak some languages more metaphorically, others more straightforward, but in a different way… it means something else. And when everyone’s translating that to English, it like really, I would say, it opens up that language more than a native speaker.”

6 Conclusion

The challenges of preparation and execution of a model UN role-play task in a pedagogical environment where English is being employed for subject learning was met with both enthusiasm and some trepidation by students due to the nature of the task. The participants observed were well prepared, and in learning “through language” (Coyle, 2007), modeled their own language use on communicative acts and actors in a real-world context. The complexities of the language proficiency required during the UNRP combined with the subject specific knowledge it necessitated means that if students were focusing on playing a part, they shifted the focus from a specific language outcome to a more approachable and functional goal, allowing them to have fun in the process. Their fun was contextualized and framed by tuition provided and written texts which were used to assess the course aims. The learning outcomes were mediated by the role-play task, helping students to further integrate their use of English in the content of their subject learning while providing them with an authentic experience in which to practice, play and demonstrate their subject learning. This exercise illustrates integration of language and content learning with the potential for lasting and transformative learning outcomes.

Data availability statement

The datasets presented in this article are not readily available because data in this article is a subset of a data set which is currently in the process of being compiled.

Ethics statement

The requirement of ethical approval was waived by The Swedish Ethical Review Authority for studies involving humans as there was no processing of sensitive personal data as specified in Section 3 of the Ethical Review Act. The studies were conducted in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. The participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study.

Author contributions

MS: Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declare that no financial support was received for the research and/or publication of this article.

Acknowledgments

I am very grateful to my supervisors, Eva Olsson and Liss Kerstin Sylvén, for their help and support and to all readers and reviewers of this manuscript. I would also like to acknowledge the hard work and contributions of the teacher and student and participants in the study, as well as valued colleagues at Gothenburg University, and in the Gothenburg municipality.

Conflict of interest

The author declares that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The author(s) declare that no Gen AI was used in the creation of this manuscript.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Supplementary material

The Supplementary material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/feduc.2025.1685102/full#supplementary-material

Footnotes

1. ^The use of L2 and references to second language perspectives in this study are made in consideration of Ortega (2013), where L2 refers to all languages acquired after L1. Many of the participants in this study are multilingual and identify as having more than two languages in their repertoire.

2. ^This group had a higher percentage of multilingual students than what is currently the case in the average Swedish classroom.

3. ^20 weeks per term, 2 terms per year; 2.5 h. per week on average (150 min).

4. ^Junior students (in the same program of studies) were also added to the senior IR teams to scaffold the task within the program of studies, as these students would be completing the IR course during the following academic year.

5. ^Participating member states in the observed role-play: Albania, Brazil, China, Ecuador, France, Gabon, Ghana, Japan, Malta, Mozambique, Russia, Switzerland, The United Arab Emirates, The United States, The United Kingdom.

6. ^This includes only the speeches made at the podium, not motions or appeals to the chairman.

References

Aristotle (1991). On rhetoric: a theory of civic discourse. 2nd Edn. New York, NY: Oxford University Press. doi: 10.1111/j.1528-3577.2005.00213.x

Clyne, M., and Sharifian, F. (2008). English as an international language: challenges and possibilities. Aust. Rev. Appl. Ling. 31, 28–21. doi: 10.2104/aral0828

Coffin, C. (2006). Historical discourse: The language of time, cause and evaluation. London: Continuum.

Coyle, D. (2007). Content and language integrated learning: towards a connected research agenda for CLIL pedagogies. Int. J. Biling. Educ. Biling. 10, 543–562. doi: 10.2167/beb459.0

Coyle, D., and Meyer, O. (2021). Beyond CLIL: Pluriliteracies teaching for deeper learning. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Dörnyei, Z., and Ushioda, E. (2009). ‘The L2 motivational self system’, in motivation, language identity and the L2 self, vol. 9–42. United Kingdom: Multilingual Matters.

Ellington, H., Fowlie, J., and Gordon, M. (1998). Using games and simulations in the classroom: A practical guide for teachers. London: Routledge.

Gibbons, P. (2002). Scaffolding language, scaffolding learning: Teaching second language learners in the mainstream classroom. Portsmouth, NH: Heinemann.

Halliday, M. A. K., and Matthiessen, C. M. I. M. (2014). Halliday’s introduction to functional grammar. 4th Edn. New York: Routledge.

Henry, A., Korp, H., Sundqvist, P., and Thorsen, C. (2018). Motivational strategies and the reframing of English: activity design and challenges for teachers in contexts of extensive extramural encounters. TESOL Q. 52, 247–273. doi: 10.1002/tesq.394

Hüttner, J., and Smit, U. (2017). Negotiating political positions: subject-specific oral language use in CLIL classrooms. Int. J. Biling. Educ. Biling. 21, 287–302. doi: 10.1080/13670050.2017.1386616

Jeong, H., Elgemark, A., and Thorén, B. (2021). Swedish youths as listeners of global Englishes speakers with diverse accents: listener intelligibility, listener comprehensibility, accentedness perception, and accentedness acceptance. Frontiers. Education 6:651908. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2021.651908

Martin, J. R. (2013). Embedded literacy: knowledge as meaning. Linguist. Educ. 24, 23–37. doi: 10.1016/j.linged.2012.11.006

Martin, J. R., and White, P. R. R. (2005). The Language of Evaluation: Appraisal in English. 1st ed. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan. doi: 10.1057/9780230511910

Mehisto, P., Marsh, D., and Frigols, M. J. (2008). Uncovering CLIL: Content and language integrated learning in bilingual and multilingual education. Oxford, UK: Macmillan.

Ortega, L. (2013). SLA for the 21st century: disciplinary progress, transdisciplinary relevance, and the bi/multilingual turn. Lang. Learn. 63, 1–24. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9922.2012.00735.x

Rocklage, M. D., Rucker, D. D., and Nordgren, L. F. (2018). Persuasion, emotion, and language: the intent to persuade transforms language via emotionality. Psychol. Sci. 29, 749–760. doi: 10.1177/0956797617744797

Schleppegrell, M. J., Achugar, M., and Oteíza, T. (2004). The grammar of history: enhancing content-based instruction through a functional focus on language. TESOL Q. 38, 67–93. doi: 10.2307/3588259

Schleppegrell, M. J., Greer, S., and Taylor, S. (2008). Literacy in history: language and meaning. Aust. J. Lang. Lit. 31, 174–187. doi: 10.1007/BF03651796

Skolverket (2012a). English. Stockholm: Swedish National Agency for Education. Available online at: https://www.skolverket.se/download/18.4fc05a3f164131a74181056/1704689136733/English-swedish-school.pdf

Skolverket (2012b). History. Stockholm: Swedish National Agency for Education. Available online at: https://www.skolverket.se/download/18.4fc05a3f164131a7418105c/1535372297799/History-swedish-school.pdf

Skolverket (2012c). Social studies [translated text]. Stockholm: Swedish National Agency for Education. Swedish National Agency for Education. Available online at: https://www.skolverket.se/download/18.4fc05a3f164131a74181078/1535372299998/Social-studies-swedish-school.pdf

Snow, M. A., Met, M., and Genesee, F. (1989). A conceptual framework for the integration of language and content in second/foreign language instruction. TESOL Q. 23, 201–217. doi: 10.2307/3587333

Sybing, R. (2023). Dialogue in the language classroom theory and practice from a classroom discourse analysis. New York: Routledge.

Sylvén, L. K., and Thompson, A. (2015). Language learning motivation and CLIL. Is there a connection? Journal of immersion and content-based. Education 3, 28–50. doi: 10.1075/jicb.3.1.02syl

Tene, T., Marcatoma Tixi, J. A., Palacios Robalino, M., de, L., Mendoza Salazar, M. J., Vacacela Gomez, C., et al. (2024). Integrating immersive technologies with STEM education: a systematic review. Front. Educ. 9:141063. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2024.1410163

Utbildning, G. R. (2024). FN Roll-spel. Available online at: https://goteborgsregionen.se/ (Accessed October 2024)

Vygotskij, L. S., Rieber, R. W., and Carton, A. S. (1987). The collected works of L.S. Vygotsky Vol. 1 problems of general psychology including the volume thinking and speech. New York: Plenum P.

Walqui, A. (2006). Scaffolding instruction for English language learners: A conceptual framework. Int. J. Bilingual Educ. Bilingualism 9, 159–180. doi: 10.1080/13670050608668639

Keywords: content and language integrated learning, United Nations role-play, subject-literacy, international relations, high school, English, history, social studies

Citation: Segura Hudson M (2025) More than a game: strengthening subject-literacy through role-play in a content and language integrated classroom. Front. Educ. 10:1685102. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2025.1685102

Edited by:

Lies Sercu, KU Leuven, BelgiumReviewed by:

Vikrant Chap, Spring Education Group, CambodiaIsabela-Anda Dragomir, Nicolae Bălcescu Land Forces Academy, Romania

Copyright © 2025 Segura Hudson. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Marta Segura Hudson, bWFydGEuc2VndXJhLmh1ZHNvbkBndS5zZQ==

Marta Segura Hudson

Marta Segura Hudson