Abstract

Open Learner Models (OLMs) are increasingly positioned as pedagogical tools capable of enhancing self-regulated learning (SRL) within higher education. Despite considerable technological progress, the pedagogical mechanisms through which OLMs support students' regulatory behaviors, metacognitive processes and motivational engagement remain insufficiently theorized. This review synthesizes empirical studies exploring OLMs that intentionally integrate pedagogical strategies in order to deepen understanding of how these models influence SRL across its preparatory, performance and reflective phases. Drawing on thematic meta-synthesis of 26 studies, the review identifies a continuum of OLMs—Inspectable, Negotiable, Editable, and Persuasive/Adaptive—that reflects progressively greater levels of learner agency, transparency, and co-regulation. Across this continuum, the pedagogical design of OLMs emerges as a critical determinant of their educational value: inspectable models predominantly support monitoring and awareness; negotiable models foster active calibration and dialogic feedback; editable models strengthen autonomy and goal-setting; and adaptive models, frequently mediated by artificial intelligence, offer personalized scaffolding that sustains engagement and reflection. Together, these findings illuminate how pedagogically enriched OLMs can operate as metacognitive mediators rather than purely analytical systems, enabling students to interpret feedback, make informed learning decisions and assume increasing ownership of their learning trajectories. The review offers a theoretically grounded framework that informs the design of transparent, ethical, and learner-centered OLMs, with implications for instructional practice, digital pedagogy, and the broader field of educational research.

Systematic review registration:

CRD420251237223.

Introduction

Open Learner Models (OLMs) have emerged as a significant innovation in educational technology (Kay et al., 2022), enabling students to visualize, reflect on, and regulate their learning processes through interactive representations of their knowledge and skills (Hernandez-de-Menendez et al., 2020). By making learning models transparent, OLMs encourage learners to engage with their academic progress and develop metacognitive and self-regulatory capabilities (Hooshyar et al., 2019). Despite the growing body of research on OLMs, much of the literature has focused on their technical development or their impact on specific cognitive outcomes (Ding and Zhang, 2025). The role of pedagogical strategies—such as instructional, motivational, and self-regulation-enhancing techniques—in augmenting the effectiveness of OLMs has received comparatively little attention (Rahimi and Cheraghi, 2024).

Emerging technologies, including artificial intelligence (AI) and learning analytics, have further expanded the potential of OLMs to support learners (Alotaibi, 2024). However, critical questions remain about how these technologies interact with pedagogical strategies to support the different phases of self-regulated learning (SRL): preparation, performance, and appraisal (Wong et al., 2019). While prior reviews have examined OLMs in the context of higher education, none have systematically explored the integration of pedagogical strategies within OLMs (Alotaibi, 2024; Kay et al., 2022) nor assessed their collective impact on the full spectrum of SRL dimensions, including cognition, metacognition, motivation, and emotion (Alam and Mohanty, 2024).

This systematic review aims to address these gaps by synthesizing evidence on how pedagogical strategies embedded in OLMs influence SRL in higher education settings. The objective is to develop a comprehensive conceptual framework that maps the relationships between OLM features, pedagogical strategies, and SRL phases, thereby informing the design of future educational technologies.

Methods

Search strategy

A comprehensive literature search was conducted across multiple electronic databases, including Scopus, Web of Science, ERIC, and PsycINFO (EBSCO). The search covered studies published from inception to July 2025 in order to capture both foundational and recent developments in the field. The strategy combined controlled vocabulary terms and free-text keywords related to “Open Learner Models,” “Pedagogical Strategies,” “Self-Regulated Learning,” and “Higher Education.” Boolean operators were applied to refine the search results. No language restrictions were imposed, allowing the inclusion of studies from diverse cultural and educational contexts. The reference lists of all included studies and relevant reviews were also screened manually to identify additional eligible publications. The complete search strategies for each database, including search strings, fields, limits, and dates, are provided in Supplementary Table 1.

Eligibility criteria

Studies were included if they met the following criteria: they investigated the implementation of OLMs in higher education and incorporated explicit pedagogical strategies (instructional, motivational, or self-regulatory). Eligible designs included experimental (randomized controlled), quasi-experimental, and pre-experimental studies that examined the integration of pedagogical strategies within their findings. Systematic reviews, theoretical papers without empirical data, conference abstracts, and studies focusing exclusively on primary or secondary education were excluded.

Outcome

The review included studies reporting outcomes related to at least one SRL dimension. The primary outcomes encompassed the core dimensions of Self-Regulated Learning—cognition, metacognition, motivation, and emotion—as well as academic performance, engagement, persistence, accuracy in self-assessment, confidence, autonomy/ownership of learning, and learning efficiency.

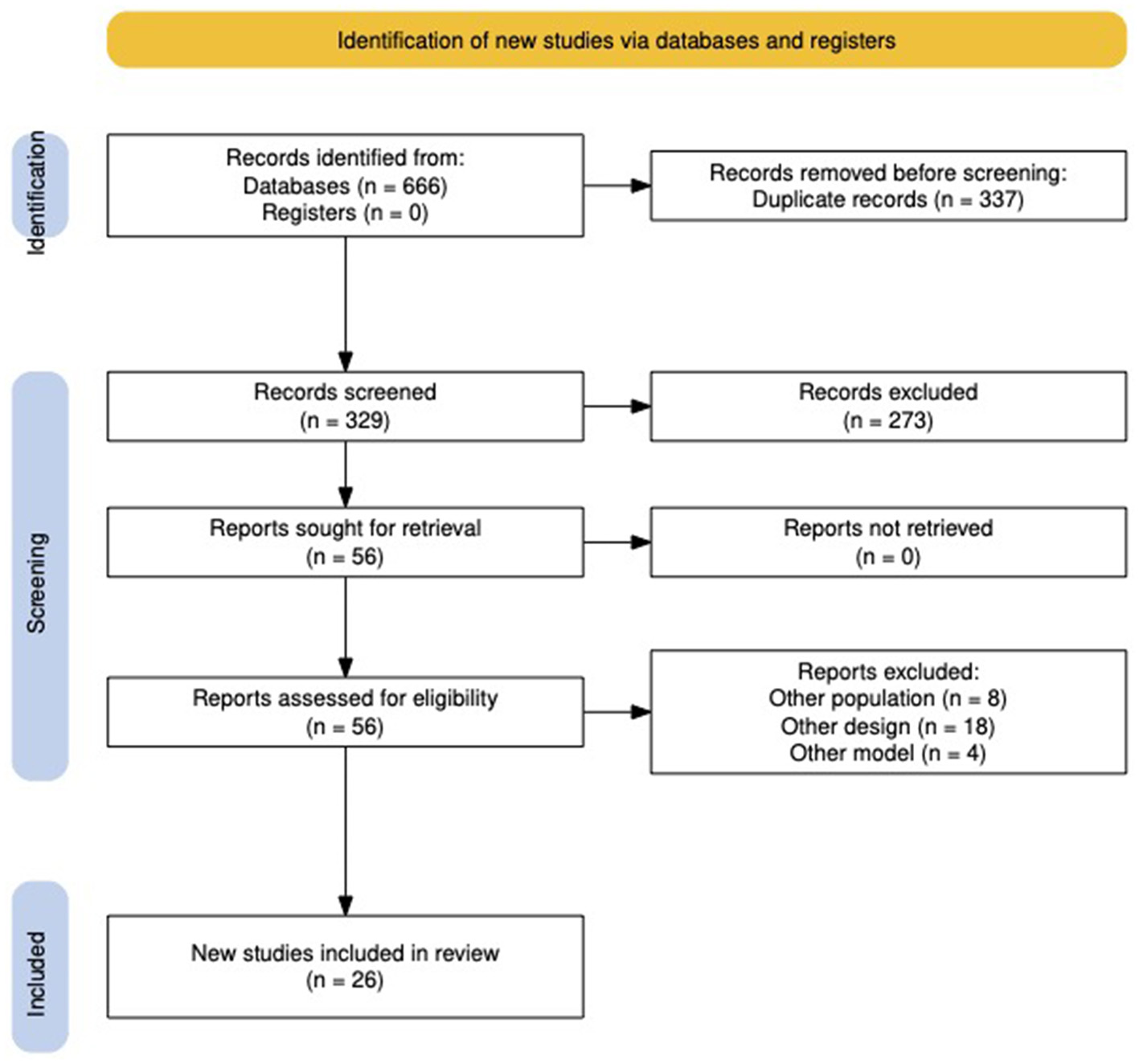

Study selection

Eight independent reviewers screened titles, abstracts, and full texts using the Rayyan platform to ensure systematic and unbiased inclusion. A senior reviewer resolved disagreements through discussion or adjudication. To ensure transparency, the full selection process, including reasons for exclusion at each stage, was documented in a PRISMA flow diagram.

Data extraction

Data extraction was conducted using a standardized form that captured key study characteristics. Extracted data included author information, year of publication, country, study design, participant demographics, educational settings, type of OLM (inspectable, negotiable, editable, persuasive), pedagogical strategies applied, SRL phases addressed (preparation, performance, appraisal), and reported outcomes across SRL dimensions. Additional contextual variables—such as technology type (AI, learning analytics dashboards), disciplinary focus, and socioeconomic setting—were also documented. Eight reviewers independently extracted the data and resolved discrepancies through consensus.

Data synthesis

The review adopted a meta-synthesis approach employing thematic synthesis as described by Thomas and Harden. This process involved three stages: initial line-by-line coding of qualitative findings, development of descriptive themes, and generation of higher-order analytical themes to capture conceptual insights into the interactions between OLMs and pedagogical strategies. RStudio software was used to support qualitative data management and coding. Subgroup analyses examined differences in outcomes by OLM type, pedagogical strategy, and degree of learner model interactivity.

In line with Thomas and Harden's approach, the thematic synthesis focused on qualitative content extracted from all included studies, regardless of their methodological design. “Qualitative findings” were operationalized as narrative results, authors' interpretations, and descriptive accounts related to the role of Open Learner Models, embedded pedagogical strategies, and self-regulated learning processes, typically reported in results and discussion sections. Quantitative outcomes were not statistically synthesized; instead, they were used to contextualize and support emerging themes where relevant. Coding was conducted independently by multiple reviewers, with discrepancies discussed and resolved through consensus, and adjudicated by a senior reviewer when necessary to ensure consistency and analytical rigor.

PROSPERO registration

This review protocol was registered in the PROSPERO International Prospective Register of Systematic Reviews under the registration number CRD420251237223.

Ethics and dissemination

This review analyzed secondary data from published studies and therefore did not require ethical approval. Findings will be disseminated through peer-reviewed journal publications, presentations at international conferences, and participation in educational technology forums. The results aim to guide educators, instructional designers, and policymakers in optimizing OLM design and integrating effective pedagogical strategies for enhancing self-regulated learning.

Results

Selection of studies

A total of 666 registers were identified through database searching across Scopus, Web of Science, ERIC, and EBSCO, covering the period from inception to July 2025. After removing 337 duplicates, 329 unique records remained for title and abstract screening.

During the initial screening phase, 273 records were excluded for being irrelevant to Open Learner Models (OLMs), lacking a higher education context, or lacking explicit pedagogical strategies. Consequently, 56 full-text articles were assessed for eligibility. At the end of the full-text evaluation, 30 were considered ineligible for inclusion.

Finally, 26 studies met the inclusion criteria and were incorporated into the qualitative synthesis (Complete references in Supplementary Table 2). The PRISMA flow diagram (Figure 1) summarizes the entire selection process, including identification, screening, eligibility assessment, and final inclusion stages.

Figure 1

PRISMA Flow chart.

Characteristics of included studies

This review included 26 empirical studies, representing a diverse range of educational contexts, technological frameworks, and methodological approaches (Table 1). Most studies were conducted within higher education environments, primarily at the undergraduate level, with a smaller proportion targeting postgraduate or professional learning settings. The research was geographically diverse, spanning North America, Europe, Asia, and the Middle East, reflecting the global adoption of Open Learner Models (OLMs) as tools for supporting self-regulated learning (SRL).

Table 1

| Study (Authors) | Year | Country | Academic discipline | Teaching mode/technology | Main reported outcomes or effects | Educational context |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Filipe Montez Coelho Madeira; Salvador Abreu; Rui Filipe Cerqueira Quaresma | 2013 | Portugal | Computer networks/computer science | Blended (classroom + LMS) | Recommendations reflected interests; MAE 0.79 (all), 0.43 (non-cold-start); 60.5% selections were relevant; 32 unique paths | Higher Education (formal) |

| Lars de Vreugd; Anouschka van Leeuwen; Marieke van der Schaaf | 2025 | Netherlands | Educational sciences/biomedical sciences | Blended (Dashboard + Curriculum Integration) | 77% attained goals; peer frame had no significant effect; LAD perceived as motivating | Higher Education (Undergraduate) |

| Lamiya Al-Shanfari; Carrie Demmans Epp; Chris Baber; Mahvish Nazir | 2020 | Oman; Canada; UK | Computer science/engineering education | Online adaptive system (OLMlets) | Alignment visualization improved monitoring and confidence judgment accuracy, especially for low-achievers | Higher Education (Java Programming course) |

| Md. I. Alam; Lauren Malone; Larysa Nadolny; Michael Brown; Cinzia Cervato | 2023 | USA | Geoscience/physical geology (stem) | Hybrid: in-person class meetings + LMS-based pre-class readings/homework | Students with dashboard averaged ~13 points higher (out of 100); first-gen proxy (children of college graduates higher); LMS page views positively associated; dashboard use frequency not significant among users | Undergraduate (introductory, large-enrollment) |

| Viktor Uglev; Georgy Smirnov | 2024 | Russia | Informatics and computer science | Individualized courses with ITS support | Simplified maps reduced reflection time and improved understanding; mode 4 preferred for quick analysis, mode 6 for deep analysis | Master's degree |

| Mengning Mu and Man Yuan | 2024 | People's Republic of China | Computer science students studying the university course “petroleum data organization and analysis” | Online learning system (CGLPRS) used for structured learning path recommendations. The final comprehensive course test was conducted offline | The experimental group (T2) significantly outperformed the control group (T1) (p = 0.001). 2′s mean score was higher (77.286 vs. 73.697). CGLPRS improved conceptual understanding and overall learning satisfaction | Third-year undergraduate students |

| Natercia Valle, Pavlo Antonenko, Denis Valle, Max Sommer, Anne Corinne Huggins-Manley, Kara Dawson, Dongho Kim, and Benjamin Baiser. | 2021 | United States | Statistics course. Statistics is often perceived as a difficult subject leading to anxiety, a critical issue in online learning environments | Online learning environment. The study utilized learning analytics dashboards (predictive/descriptive) as the intervention in an online graduate course | The predictive dashboard significantly reduced interpretation anxiety. Both predictive and descriptive dashboards reduced worth of statistics anxiety for learners with high initial anxiety levels. No significant effect on learning performance was found | Graduate students enrolled in an introductory online statistics course. |

| Chih-Yueh Chou and Nian-Bao Zou. | 2020 | Taiwan ROC | Computer programming course. Students learned basic programming knowledge and skills, including 6 meta-concepts and 16 concepts. The assessments used program-output-prediction problems | Blended approach. Learning activities involved a teacher's lecture followed by structured SRL activities mediated by the online OLM-SRL system in a computer classroom. | Students frequently displayed poor SRL (overestimated mastery: 75%; failed to achieve goals: 69%). However, 66% modified their self-assessment following OLM feedback. SRL tools/OLMs assisted most students in monitoring, goal setting, and reflection. | Undergraduate students enrolled in a programming course to learn basic programming knowledge and skills. |

| Gulipari Maimaiti and Khe Foon Hew | 2025 | Hong Kong | College english, studied as a foreign language (l2 english learning). Participants were majoring in software development. | Flipped Classroom (FC). The intervention was a Gamified Self-Regulated Flipped Learning (GSRFL) approach integrating online preparation and in-class active learning. | Gamification significantly improved English learning achievement. It also significantly increased overall SRL behaviors across all six strategies. Gamification moderated the natural decline in goal setting and time management strategies over time. | First-year university students. |

| Mohammed Alzaid and Sharon Hsiao. They are affiliated with the School of Computing, Informatics and Decision Systems Engineering, Arizona State University, Tempe, AZ, USA | 2019 | United States | Computer programming course (specifically, introductory java). The curriculum covered topics such as variables, methods, strings, loops, and arrays. | Used as a voluntary supplemental self-assessment tool supporting regular and blended course environments. The pedagogical approach emphasized daily distributed practice. | Higher effort levels correlated with increased course performance (up to one letter grade difference for persistent users). Quiz Adapt implementation reduced the average number of attempts needed to find the correct answer (from 2.1 to 1.5) | Undergraduate students who were novice programmers, enrolled in an introductory programming course. |

| Yung-Hsiang Hu, Bo-Kai Liao and Chieh-Lun Hsieh | 2024 | Taiwan | Business ethics | Self-paced, asynchronous online learning | The gamified LAD with CoRL had significant positive effects on SRL, learning engagement, and academic achievement compared to the conventional LAD | Higher Education (University) |

| Christopher C. Y. Yang, Jiun-Yu Wu and Hiroaki Ogata | 2024 | Taiwan | Accounting information systems | Blended Learning (BL) | The experimental group, using the LAD-based SRL approach, showed statistically significant improvements compared to the control group in learning outcomes, awareness of SRL, self-efficacy (SE), and all three measures of e-book reading engagement. | Undergraduate (Higher Education) |

| Damien S. Fleur, Wouter van den Bos, Bert Bredeweg | 2023 | Netherlands | Informatics-related programme | Experiment 1: Face-to-face (on-location lectures and seminars). Experiment 2: Fully Online (due to the COVID-19 pandemic) | The LAD intervention led to higher academic achievement and supported extrinsic motivation in both experiments. No significant effect on intrinsic motivation or metacognition was found | Undergraduate (Higher Education) |

| Damien S. Fleur, Max Marshall, Miguel Pieters, Natasa Brouwer, Gerrit Oomens, Angelos Konstantinidis, Koos Winnips, Sylvia Moes, Wouter van den Bos, Bert Bredeweg, and Erwin A. van Vliet. Their affiliations are mainly with the University of Amsterdam and the University of Groningen. | 2023 | Netherlands. | The study was conducted in a single elective course. The focus is on generic self-regulated learning (srl) and academic achievement. | The mode was a large-scale course where students had self-directed access to the IguideME Learning Analytics Dashboard (LAD). | Treatment students achieved higher scores for “metacognitive self-regulation” (MSLQ), “peer learning” (MSLQ), and “other-approach” (AGQ). They performed better on reading assignments and high-level Bloom exam questions. | Higher Education, specifically with a cohort of full-time 3rd-year bachelor students enrolled in an elective course. |

| Lars de Vreugd, Renée Jansen, Anouschka van Leeuwen, and Marieke van der Schaaf. They are affiliated with the Utrecht Center for Research and Development of Health Professions Education and Utrecht University in the Netherlands | 2023 | Netherlands | Participants were drawn from various study programs that implemented the dashboard, such as educational sciences, economics, and biomedical sciences | The context involves students using a Learning Analytics Dashboard (LAD) to reflect on study behavior. The data collection interviews were held via MS Teams in Dutch or English | The peer reference frame led to the most verbalizations of internal feedback (specifically Awareness) and potentially the most preparatory activities. Reference frames reduced the use of other external comparators | University students, including 1st, 2nd, and 3rd year bachelor students, and master students |

| Vinicius Hartmann Ferreira and Eliseo Reategui are the authors of the article. Their affiliation is the Faculdade de Educação, Universidade Federal do Rio Grande do Sul, located in Porto Alegre, Brazil. | 2020 | Brazil | The study focuses on introductory computer programming (introdução a programação de computadores). The curriculum covered five main topics, including conditionals, repetition, and modularization. | The intervention utilized a Virtual Learning Environment (AVA) centered on the Open Social Student Model (OSSM). | Students used the OSSM for monitoring, evaluating, organizing, and seeking help. A moderate positive correlation was found between KMA and general performance ($p=0.63$). However, the intervention did not cause significant changes in overall metacognitive awareness (MAI results). | The study was conducted in a course on introductory computer programming at the higher education level (ensino superior). |

| Ioana Jivet, Maren Scheffel, Marcel Schmitz, Stefan Robbers, Marcus Specht, and Hendrik Drachsler. Their affiliations include Open University of the Netherlands, Zuyd University of Applied Sciences, Delft University of Technology, Goethe University, and DIPF. | 2020 | Netherlands | The participants were enrolled at the faculty of computer science. The research investigated generic self-regulated learning and sense-making of learning analytics (la). | The study used a dashboard mock-up to support students' self-regulated learning (SRL). The SRL assessment utilized scales validated for blended and online learning environments. | SRL skills are highly significant predictors for the relevance of all three sense-making factors. Learner goals only had a significant effect on the perceived relevance of reference frames. Higher SRL correlates positively with higher relevance ratings. | The study focuses on Higher Education (HE). The quantitative study involved 247 1st- and 2nd-year Bachelor and Associate Degree students. |

| Georgios Psathas, Stergios Tegos, Stavros N. Demetriadis, and Thrasyvoulos Tsiatsos. | 2023 | Greece | Programming, focused on basic concepts, algorithmic thinking, and the python programming language. | Online, Distance Learning via a MOOC. It incorporated video lectures, mini-quizzes, weekly quizzes, weekly assignments, and chat-based collaborative activities. | Both general and personalized interventions increased participation in collaborative activities and improved learning outcomes compared to the control group. Personalized intervention significantly improved SRL profiles and reduced dropout rates more effectively than the control group. SRL profiles predicted participation. | Massive Open Online Courses (MOOCs). The course was “Programming for non-Programmers.” |

| Yung-Hsiang Hu. | 2021 | Taiwan | The research focused on students registered with the innovative thinking course. | Problem-Based Learning (PBL) classroom using an AI-supported Smart Learning Environment (SLE) to support collaborative learning. The study focused on the physical classroom. | Students who used the platform more frequently than average had higher course results and smaller standard deviation. All hypothesized relationships in the TAM model were significant, confirming Output Quality, PEOU, and PU influence Behavioral Intention and Transfer of Learning. | University level, involving 50 first-year students. |

| Natercia Valle, Pavlo Antonenko, Denis Valle, Kara Dawson, Anne Corinne Huggins-Manley, and Benjamin Balser. | 2021 | United States | Statistics. The research focused on students registered for a semester-long introductory online statistics course. | Online learning environment. The delivery was via Canvas™, supported by a predictive Learning Analytics Dashboard (LAD) for self-regulatory support. | No significant effect on motivation or learning performance. Task-value scaffolding significantly reduced computation anxiety and potentially increased worth anxiety for high anxiety learners. | Non-secondary education; university level, specifically an introductory online statistics course. |

| David P. Reid and Timothy D. Drysdale. They are affiliated with the School of Engineering at the University of Edinburgh, UK. | 2024 | United Kingdom | Engineering, specifically foundational skills, remote lab practical work, and controls engineering. Students came from mechanical, electrical, civil, and chemical engineering streams | Hybrid learning environment: remote access to the hardware (via web-browser) but located in an in-person, traditional classroom setting with staff and peers available | Students who used the dashboard achieved significantly better task completion (smaller TaskCompare score) than non-users. The rating of dashboard usefulness was significantly positive, above a neutral response (M = 5) | University students (undergraduate). The primary evaluation involved first-year students (typically 17–19 years old) in the Engineering Design 1 course. Validation data used third-year students |

| Yuko Toyokawa, Prajish Prasad, Izumi Horikoshi, Rwitajit Majumdar, and Hiroaki Ogata. Their affiliations include Kyoto University (Japan), FLAME University (India), and Kumamoto University (Japan) | 2025 | India | Computer science and programming, focusing specifically on program comprehension (pc) in programming courses | Face-to-face classes combined with the use of the LEAF system. The experiment involved four classes over 2 weeks, focusing on code reading activities | The experimental group showed significantly increased out-of-class reading time and faster code reading speed. Utilizing the dashboard positively influenced autonomous learning behavior outside the classroom | Second-year college students (average age 20) enrolled in a programming course for beginners at a liberal arts college |

| Tornike Giorgashvili, Ioana Jivet, Cordula Artelt, Daniel Biedermann, Daniel Bengs, Frank Goldhammer, Carolin Hahnel, Julia Mendzheritskaya, Julia Mordel, Monica Onofrei, Marc Winter, Ilka Wolter, Holger Horz, and Hendrik Drachsler. | 2025 | Germany | Educational sciences/pedagogy, specifically focusing on the use of digital media in teaching. The research focused on self-regulated learning (srl) processes | Online course structure delivered via the Moodle LMS. The instruction included video lectures, reading assignments, and interactive exercises | Personalized feedback led to reflection texts that focused on different aspects compared to minimal feedback. Feedback helpfulness predicted the incorporation of suggested behavioral changes. Specific hints significantly increased the likelihood of reflecting on Control and Elaboration strategies | First-semester university students. The participants were teacher students enrolled in an online course. The average age was 22 years old (std = 5) |

| Gulipari Maimaiti, Khe Foon Hew | 2025 | Hong Kong | English as a foreign language (efl) for software development majors | Flipped Classroom. The study implemented a “gamified self-regulated flipped learning (GSRFL) approach” which involves pre-class online activities and in-person sessions | Gamification significantly improved English learning performance and overall SRL behaviors. It positively influenced metacognitive monitoring and moderated the decline of goal setting and time management over time | Higher Education/University |

| Jerry Chih-Yuan Sun, Hsueh-Er Tsai, Wai Ki Rebecca Cheng | 2023 | Taiwan, UK | Research ethics | Self-directed online learning | Combining self-regulation and data visualization features significantly improved students' goal-setting and help-seeking behaviors. This combination also motivated students to review content after checking their performance charts | Higher Education (master and doctoral students) |

| Raja M. Suleman, Riichiro Mizoguchi, Mitsuru Ikeda | 2016 | Pakistan | Data structures (including topics like stacks, queues, and linked lists) | Self-directed online learning using an Intelligent Tutoring System (ITS) called NDLtutor with chatbot | Negotiation with the NDLtutor led to a significant improvement in students' self-assessment accuracy. Students also rated the dialogue quality and the usefulness of the reflection phase highly | Higher Education. Participants were undergraduate Software Engineering students. |

| Lamiya Al-Shanfari, Carrie Demmans Epp, Chris Baber, and Mahvish Nazir | 2020 | UK | The study was part of a course called “introduction to java programming” within a school of engineering | Not explicitly stated, but the system was used by students on their own time as a voluntary activity to prepare for class tests, suggesting a blended or supplemental online mode | Visualizing alignment supported more accurate confidence judgments, especially for low-achieving students, whose performance also increased significantly. The simple act of practicing self-assessment also appeared beneficial for the control group over time. | Undergraduate students in their 2nd year of study |

| Chih-Yueh Chou, K. Robert Lai, Po-Yao Chao, Chung Hsien Lan, Tsung-Hsin Chen | 2015 | Taiwan | Computer programming | E-learning systems (SALS, UALS, NALS) | The NALS group showed better calibration accuracy (self-assessment) and made better content choices (regulation) than the other groups. They also performed better on the delay test for one of the lessons | Undergraduate college students |

Characteristics of included studies.

In terms of disciplinary distribution, STEM-related fields—particularly computer science, engineering, and educational technology—were the most common, followed by studies in the social and health sciences. The majority of interventions used digital learning environments or blended instructional models, including learning management systems (e.g., Moodle, Canvas), learning analytics dashboards, and intelligent tutoring systems.

Methodologically, most studies adopted mixed-methods or quasi-experimental designs, complemented by qualitative analyses exploring learner perceptions, behavioral patterns, and motivational dynamics. A recurring emphasis across studies was the integration of pedagogical strategies—including goal setting, reflection on feedback, and confidence calibration—within OLM frameworks to enhance SRL phases related to performance and appraisal.

Overall, the included studies demonstrate a growing research trend toward adaptive, learner-centered technologies that combine transparent data visualization with pedagogical scaffolding to promote metacognitive engagement and autonomous learning. These collective findings, summarized in Table 1, provide the empirical foundation for the subsequent thematic synthesis of OLM categories and pedagogical strategies.

Meta-synthesis of open learner model categories

The meta-synthesis integrated evidence from twenty-six empirical studies exploring the intersection between Open Learner Models (OLMs), pedagogical strategies, and self-regulated learning (SRL) in higher education (Table 2). The synthesis revealed four overarching categories of OLMs—inspectable, Negotiable, Editable, and Persuasive/Adaptive—which collectively illustrate the spectrum of transparency, interactivity, and autonomy afforded to learners. Each category reflects a distinct pedagogical orientation and technological configuration that influences the mechanisms through which SRL is fostered.

Table 2

| Study | OLM category | OLM type/technology | Main outcomes | Educational context |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Madeira et al. (2013) (Portugal) | Persuasive/adaptive OLM | N/A – Hybrid recommender within LMS | Recommendations reflected interests; MAE 0.79 (all), 0.43 (non-cold-start); 60.5% selections were relevant; 32 unique paths | Higher Education (formal) |

| de Vreugd et al. (2025) (Netherlands) | Inspectable OLM | Learning Analytics Dashboard (not fully OLM) | 77% attained goals; peer frame had no significant effect; LAD perceived as motivating | Higher Education (Undergraduate) |

| Al-Shanfari et al. (2020) (Oman; Canada; UK) | Persuasive/adaptive OLM | Open Learner Model (visualized with skill meters) | Alignment visualization improved monitoring and confidence judgment accuracy, especially for low-achievers | Higher Education (Java Programming course) |

| Alam et al. (2023) (USA) | Persuasive/adaptive OLM | Gamified Learning Analytics Dashboard (LAD) integrated in LM | Students with dashboard averaged ~13 points higher (out of 100); first-gen proxy (children of college graduates higher); LMS page views positively associated; d | Undergraduate (introductory, large-enrollment) |

| Uglev and Smirnov (2024) (Russia) | Persuasive/adaptive OLM | Interactive cognitive mapping system (CMKD) within ITS | Simplified maps reduced reflection time and improved understanding; mode 4 preferred for quick analysis, mode 6 for deep analysis | Master's degree |

| Mu and Yuan (2024) (People's Republic of China) | Persuasive/adaptive OLM | The CGLPRS uses cognitive graph technology to visualize the | The experimental group (T2) significantly outperformed the control group (T1) (p = 0.001). 2′s mean score was higher (77.286 vs. 73.697). CGLPRS improved concept | Third-year undergraduate students |

| Valle et al. (2021) (United States) | Persuasive/Adaptive OLM | Learning Analytics Dashboards (LADs). Two types were designed | The predictive dashboard significantly reduced interpretation anxiety. Both predictive and descriptive dashboards reduced worth of statistics anxiety for learner | Graduate students enrolled in an introductory online |

| Chou and Zou (2020) (Taiwan ROC) | Inspectable OLM | Open Learner Models (OLMs). They visualize mastery levels of | Students frequently displayed poor SRL (overestimated mastery: 75%; failed to achieve goals: 69%). However, 66% modified their self-assessment following OLM fee | Undergraduate students enrolled in a programming c |

| Maimaiti and Hew (2025) (Hong Kong) | Inspectable OLM | Learning Analytics Dashboard (LAD), defined as a single display | Gamification significantly improved English learning achievement. It also significantly increased overall SRL behaviors across all six strategies. Gamification | First-year university students. |

| Alzaid and Hsiao (2019) (United States) | Editable OLM | Open Student Model (OSM) and Open Social Student Modeling (O) | Higher effort levels correlated with increased course performance (up to one letter grade difference for persistent users). Quiz Adapt implementation reduced the | Undergraduate students who were novice programmers |

Characteristics of outcomes assessed.

While all categories shared the goal of enhancing learners' metacognitive engagement, they differed in the degree of control granted to students and in the type of pedagogical scaffolding embedded in the system. The findings suggest that these OLM categories do not operate in isolation but rather along a continuum of learner agency, ranging from system-guided reflection (Inspectable models) to learner-driven regulation (Editable models), culminating in adaptive co-regulation mediated by artificial intelligence (Persuasive/Adaptive models).

Inspectable open learner models

Definition and pedagogical nature

Inspectable OLMs are the most widely identified form in the literature. These models allow students to view their learning progress, performance metrics, or conceptual mastery through dashboards, progress bars, or visual summaries without directly modifying the underlying data. They emphasize transparency and feedback awareness as mechanisms for supporting SRL.

Implementation and evidence

Studies employing learning management systems (e.g., Moodle, Canvas) or analytic dashboards exemplify this category. For instance, dashboards displaying performance trajectories and completion statistics prompted learners to reflect on their study habits and progress over time.

Pedagogical role and SRL impact

The pedagogical strategies embedded in inspectable models center on reflective monitoring and self-evaluation. Learners are encouraged to interpret visual feedback and compare their current progress against goals or peer benchmarks. These systems primarily influence the performance and appraisal phases of SRL by enhancing self-judgment awareness and accuracy. Quantitative evidence showed consistent gains in engagement, persistence, and academic outcomes, while qualitative findings highlighted increased perceived control and motivation.

Synthesis insight

In essence, inspectable OLMs act as mirrors of learning. Their strength lies in the cognitive activation of metacognitive monitoring, though their limited interactivity constrains deeper regulation or strategy adaptation.

Negotiable open learner models

Definition and pedagogical nature

Negotiable OLMs are characterized by bidirectional interaction between the learner and the system. Rather than passively observing their data, students engage in dialogue, calibration, or feedback negotiation with the OLM, thereby co-constructing their learner model.

Implementation and evidence

This category includes studies using OLMlets or systems with confidence rating interfaces and dialogic feedback. Learners were prompted to assess their confidence in their mastery of the topic, after which the system adjusted representations or provided opportunities for negotiation about the learner's understanding.

Pedagogical role and SRL impact

Negotiable OLMs embody a metacognitive calibration pedagogy that directly targets learners' capacity to evaluate and adjust their understanding. Empirical findings show improvements in confidence, accuracy, self-assessment precision, and motivation. These models operate across the performance and appraisal phases and also stimulate metacognitive reflection, thereby bridging the two.

Synthesis insight

Negotiable OLMs transform feedback into dialogue. They promote a dynamic exchange that strengthens awareness of learning processes, fostering self-efficacy and emotional regulation—key components of mature SRL.

Editable open learner models

Definition and pedagogical nature

Editable OLMs allow students to modify, annotate, or add information to their learner profiles. By empowering users to actively shape their learning models, these systems embody a philosophy of learner autonomy and self-determination.

Implementation and evidence

Examples include goal-setting interfaces, portfolio-based systems, or environments permitting self-reported progress tracking. These models often required pedagogical mediation to ensure that learners' inputs were reflective rather than arbitrary.

Pedagogical role and SRL impact

Editable models are tightly linked to the preparatory phase of SRL, particularly in goal planning, self-assessment, and strategy formulation. They operationalize pedagogical strategies such as self-regulated goal management and plan-do-review cycles. Studies reported that students exposed to editable systems exhibited stronger initiative, ownership, and persistence in achieving goals.

Synthesis insight

Editable OLMs move from reflection to ownership. Their pedagogical essence lies in transferring agency to learners, promoting accountability, and intentional regulation. However, they require scaffolding to mitigate risks of misjudgment or overconfidence.

Persuasive and adaptive open learner models

Definition and pedagogical nature

Persuasive or adaptive OLMs represent the most technologically advanced form. They integrate artificial intelligence, machine learning, or recommendation algorithms to deliver personalized feedback, nudges, or content adaptation aligned with the learner's evolving profile.

Implementation and evidence

Studies in this category employed intelligent tutoring systems (ITS), cognitive mapping interfaces, and recommender models. These tools dynamically adjusted instructional pathways based on learner behavior, engagement, or inferred needs.

Pedagogical role and SRL impact

Persuasive/Adaptive OLMs align with adaptive scaffolding pedagogy, wherein systems act as co-regulators that anticipate learner needs and deliver timely feedback. They support all three SRL phases—preparation, performance, and appraisal—by tailoring challenges, encouraging reflection, and sustaining motivation. Empirical evidence highlighted improvements in learning efficiency, time-on-task, and depth of cognitive engagement.

Synthesis insight

These models function as intelligent companions that blend automation with pedagogy. While they optimize regulation and engagement, concerns remain regarding transparency, learner dependency, and ethical accountability of AI-driven personalization.

Discussion

The present meta-synthesis provides a broad conceptual understanding of how Open Learner Models (OLMs), when enriched with pedagogical strategies, foster self-regulated learning (SRL) in higher education. The analysis of 26 empirical studies identified four distinct yet interconnected categories of OLMs: Inspectable, Negotiable, Editable, and Persuasive/Adaptive, which, taken together, constitute a continuum of student agency that ranges from system-guided reflection to adaptive co-regulation.

Overview of the main findings

Across the included studies, OLMs consistently demonstrated their potential to strengthen students' self-awareness, motivation, and autonomy (Al-Shanfari et al., 2020; Sun et al., 2023). Inspectable OLMs fostered awareness by visualizing learning progress (Ferreira and Reátegui, 2020), acting as “mirrors” that support self-assessment (Jivet et al., 2020; Yang et al., 2025). Negotiable OLMs deepened engagement by introducing interactive dialogue and confidence calibration, enabling students to co-construct their understanding together with the system (Al-Shanfari et al., 2020). Editable OLMs shifted responsibility for learning by allowing students to define their own goals (Kay et al., 2022). Finally, persuasive or adaptive OLMs, powered by artificial intelligence and machine learning algorithms (Chou and Zou, 2020), provided dynamic scaffolding that personalizes learning trajectories and sustains engagement across the different phases of SRL (de Vreugd et al., 2023). Taken together, these findings indicate that integrating pedagogical strategies into OLMs transforms them from static monitoring tools into interactive metacognitive systems that align technological capabilities with human learning processes.

Relationship to previous research

These results expand upon and refine the foundational frameworks proposed by Bull and Kay (2016) and Jivet et al. (2020), who highlighted transparency and interpretability as central elements of student models. While previous literature has primarily examined OLMs from technological or cognitive perspectives, this review centers the pedagogical dimension as a critical determinant of their educational effectiveness. The identified categories align with the conceptual progression described by Maré and Mutezo (2025), which ranges from awareness and reflection to monitoring and co-regulation. However, this synthesis goes further by explicitly linking each type of OLM to specific phases of SRL preparation, performance, and evaluation and by demonstrating that pedagogical scaffolding operates as a mediating mechanism that transforms transparency into self-regulatory competence (Khine, 2024).

The results are also consistent with metacognitive and self-directed learning (SRL) theories proposed by Zimmerman and Schunk (2001), which argue that students benefit most when technology supports the cyclical interaction between prediction, performance monitoring, and self-reflection. In this sense, online learning tools (OLMs) are not merely digital dashboards but metacognitive mediators that can enhance both cognitive and affective regulation when combined with strategies such as goal setting, reflection on feedback, and motivational stimuli (Toomla et al., 2025).

Theoretical and pedagogical implications

From a theoretical perspective, this study proposes an integrative framework that positions OLMs as dynamic interfaces mediating between data transparency and pedagogical intentionality. The typology identified suggests that each model type corresponds to a distinct level of learner autonomy and phase of SRL. Inspectable OLMs are particularly effective for performance monitoring, while negotiable and editable models facilitate metacognitive calibration and strategic planning, respectively. Persuasive or adaptive models transcend individual regulation by promoting co-regulated learning, in which artificial intelligence collaborates with human judgment to sustain motivation and engagement.

The results underscore that instructional design must move beyond visualization and integrate explicit self-regulatory scaffolds—for example, prompts for reflection, guided goal-setting modules, or adaptive feedback aligned with students' confidence levels. When pedagogical strategies are intentionally embedded, OLMs cease to be passive representations of learning and become active learning partners, supporting the cognitive, motivational, and emotional dimensions of self-regulation.

Design and practical implications

For instructional designers and developers, this synthesis provides evidence-based guidance for creating digital ecosystems centered on student learning. In this regard, future Online Learning Models (OLMs) should integrate transparent analytics systems that communicate learning processes in accessible and comprehensible terms; dialogic feedback mechanisms that promote negotiation and explanation among participants; editable components that allow students to express, adjust, and reformulate their learning goals; as well as adaptive engines capable of personalizing support or scaffolding without compromising learner autonomy. These features contribute to a more inclusive, reflective, and self-regulated digital educational environment in which students assume an active role in constructing their own knowledge.

For educators, the practical implication is the need to integrate OLMs within pedagogical sequences—not as isolated tools but as part of a reflective cycle that includes pre-task planning, ongoing monitoring, and post-task evaluation. Faculty development initiatives should also emphasize how to interpret learner analytics responsibly and how to guide students in using OLM feedback effectively. Policymakers, in turn, must consider the ethical and equity implications of AI-based OLMs, ensuring transparency, data privacy, and inclusivity in their deployment.

Methodological reflections and limitations

While this synthesis offers a comprehensive conceptual model, certain methodological limitations must be acknowledged. The predominance of STEM-based contexts may limit transferability to the humanities and social sciences, where learning outcomes and SRL dynamics differ. Furthermore, variations in the operationalization of SRL across studies introduce heterogeneity that constrains quantitative comparison. Most studies relied on short-term interventions, making it difficult to assess the longitudinal effects of OLM exposure on sustained self-regulation. Nonetheless, the convergence of findings across diverse methodological designs and cultural contexts supports the robustness of the identified themes.

Future research directions

Future investigations should empirically test the proposed typology across broader educational settings and disciplines. Experimental or longitudinal studies could evaluate how transitions between OLM categories influence the development of SRL competencies over time. Additionally, greater attention is needed on affective and motivational dimensions, exploring how emotions and self-efficacy interact with OLM feedback. Research should also address ethical design questions related to data transparency, algorithmic bias, and learner agency in AI-driven systems. Finally, mixed-methods approaches combining behavioral analytics with qualitative inquiry may provide richer insights into how learners interpret and act upon OLM-generated feedback.

Conclusion

This meta-synthesis demonstrates that the effectiveness of Open Learner Models in higher education depends not solely on their technological sophistication but on their pedagogical alignment with self-regulated learning principles. By conceptualizing OLMs as pedagogically enriched systems rather than purely analytical instruments, this review positions them at the intersection of educational technology, cognitive science, and instructional design. The typology developed—ranging from inspectable to persuasive/adaptive models—offers a framework for designing intelligent, transparent, and ethically grounded learning environments that empower students to become autonomous, reflective, and self-regulated learners.

Statements

Data availability statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/Supplementary material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Author contributions

JR: Writing – original draft, Formal analysis, Visualization, Supervision, Methodology, Writing – review & editing, Investigation, Validation, Conceptualization, Data curation. DA-G: Formal analysis, Writing – review & editing, Writing – original draft, Validation, Visualization, Investigation, Supervision, Conceptualization, Project administration, Methodology. VB-T: Investigation, Validation, Methodology, Conceptualization, Writing – review & editing, Supervision, Visualization, Formal analysis, Project administration, Writing – original draft, Data curation. NQ-M: Conceptualization, Writing – review & editing, Supervision, Investigation, Writing – original draft, Project administration, Validation, Methodology, Formal analysis, Data curation, Visualization. CA-J: Writing – original draft, Investigation, Visualization, Formal analysis, Writing – review & editing, Methodology, Validation, Data curation, Conceptualization, Supervision. HT: Writing – original draft, Visualization, Formal analysis, Validation, Conceptualization, Methodology, Supervision, Data curation, Investigation, Writing – review & editing. FL-V: Writing – review & editing, Formal analysis, Writing – original draft, Validation, Conceptualization, Visualization, Methodology, Data curation, Supervision, Investigation. KL-D: Formal analysis, Data curation, Visualization, Writing – original draft, Validation, Conceptualization, Writing – review & editing, Supervision, Investigation, Methodology. OR-L: Writing – review & editing, Supervision, Data curation, Methodology, Conceptualization, Investigation, Writing – original draft, Visualization, Validation, Formal analysis. AC: Supervision, Conceptualization, Investigation, Validation, Writing – review & editing, Formal analysis, Writing – original draft, Data curation, Methodology, Visualization. PJ: Formal analysis, Validation, Conceptualization, Writing – review & editing, Resources, Project administration, Writing – original draft, Methodology, Data curation, Visualization, Investigation. JB: Supervision, Project administration, Resources, Writing – review & editing, Writing – original draft, Formal analysis, Software, Data curation, Visualization, Conceptualization, Investigation, Validation, Methodology.

Funding

The author(s) declared that financial support was not received for this work and/or its publication.

Conflict of interest

The author(s) declared that this work was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The author(s) declared that generative AI was not used in the creation of this manuscript.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Supplementary material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/feduc.2025.1760183/full#supplementary-material

References

1

Alam A. Mohanty A. (2024). Framework of self-regulated cognitive engagement (FSRCE) for sustainable pedagogy: a model that integrates SRL and cognitive engagement for holistic development of students. Cogent Educ.11:2363157. doi: 10.1080/2331186X.2024.2363157

2

Alam M. I. Malone L. Nadolny L. Brown M. Cervato C. (2023). Investigating the impact of a gamified learning analytics dashboard: Student experiences and academic achievement. J. Comput. Assist. Learn.9, 1436–1449. doi: 10.1111/jcal.12853

3

Alotaibi N. S. (2024). The impact of AI and LMS integration on the future of higher education: opportunities, challenges, and strategies for transformation. Sustainability16:10357. doi: 10.3390/su162310357

4

Al-Shanfari L. Demmans Epp C. Baber C. Nazir M. (2020). Visualising alignment to support students' judgment of confidence in open learner models. User Model. User-adapt. Interact.30, 159–199. doi: 10.1007/s11257-019-09253-4

5

Alzaid M. Hsiao S. (2019). Utilising problem-solving: from self-assessment to self regulating. New Rev. Hypermedia Multimedia25, 222–244. doi: 10.1080/13614568.2019.1705922

6

Bull S. Kay J. (2016). SMILI?: a framework for interfaces to learning data in open learner models, learning analytics and related fields. Int. J. Artif. Intel. Educ.26, 293–331. doi: 10.1007/s40593-015-0090-8

7

Chou C.-Y. Zou N.-B. (2020). An analysis of internal and external feedback in self-regulated learning activities mediated by self-regulated learning tools and open learner models. Int. J. Educ. Technol. High. Educ.17, 1–23. doi: 10.1186/s41239-020-00233-y

8

de Vreugd L. Jansen R. van Leeuwen A. van der Schaaf M. (2023). The role of reference frames in learners' internal feedback generation with a learning analytics dashboard. Stud. Educ. Eval.79:101303. doi: 10.1016/j.stueduc.2023.101303

9

de Vreugd L. van Leeuwen A. van Der Schaaf M. (2025). Students' use of a learning analytics dashboard and influence of reference frames: goal setting, motivation, and performance. J. Comput. Assist. Learn.41:e70015. doi: 10.1111/jcal.70015

10

Ding L. Zhang H. (2025). The gradual cyclical process in adaptive gamified learning: generative mechanisms for motivational transformation, cognitive advancement, and knowledge construction strategy. Appl. Sci.15:9211. doi: 10.3390/app15169211

11

Ferreira V. H. Reátegui E. (2020). Programming learning supported by the open social student model. Rev. Latinoamer. Tecnol. Educ.19, 83–99. doi: 10.17398/1695-288X.19.2.83

12

Hernandez-de-Menendez M. Escobar Díaz C. Morales-Menendez R. (2020). Technologies for the future of learning: state of the art. Int. J. Inter. Des. Manuf.14, 683–695. doi: 10.1007/s12008-019-00640-0

13

Hooshyar D. Kori K. Pedaste M. Bardone E. (2019). The potential of open learner models to promote active thinking by enhancing self-regulated learning in online higher education learning environments. Br. J. Educ. Technol.50, 2365–2386. doi: 10.1111/bjet.12826

14

Jivet I. Scheffel M. Schmitz M. Robbers S. Specht M. Drachsler H. (2020). From students with love: an empirical study on learner goals, self-regulated learning and sense-making of learning analytics in higher education. Internet High. Educ.47:100758. doi: 10.1016/j.iheduc.2020.100758

15

Kay J. Bartimote K. Kitto K. Kummerfeld B. Liu D. Reimann P. (2022). Enhancing learning by Open Learner Model (OLM) driven data design. Comput. Educ.3:100069. doi: 10.1016/j.caeai.2022.100069

16

Khine M. S. (2024). “Machine Learning in Education,” in Artificial Intelligence in Education, ed. M. S. Khine (Singapore: Springer). doi: 10.1007/978-981-97-9350-1

17

Madeira F. M. C. Abreu S. Quaresma R. F. C. (2013). Hybrid recommender strategy in learning: An experimental investigation. Soc. Technol.3, 7–24. doi: 10.13165/ST-13-3-1-01

18

Maimaiti G. Hew K. F. (2025). Gamification bolsters self-regulated learning, learning performance and reduces strategy decline in flipped classrooms: a longitudinal quasi-experiment. Comput. Educ.230:105278. doi: 10.1016/j.compedu.2025.105278

19

Maré S. Mutezo A. T. (2025). The influence of self- and co-regulation on the community of inquiry for collaborative online learning: an ODeL context. J. Appl. Res. High. Educ.17, 349–364. doi: 10.1108/JARHE-08-2023-0325

20

Mu M. Yuan M. (2024). Research on a personalized learning path recommendation system based on cognitive graph with a cognitive graph. Interact. Learn. Environ.32, 4237–4255. doi: 10.1080/10494820.2023.2195446

21

Rahimi A. R. Cheraghi Z. (2024). Unifying EFL learners' online self-regulation and online motivational self-system in MOOCs: a structural equation modeling approach. J. Comput. Educ.11, 1–27. doi: 10.1007/s40692-022-00245-9

22

Sun J. C.-Y. Tsai H.-E. Cheng W. K. R. (2023). Effects of integrating an open learner model with AI-enabled visualization on students' self-regulation strategies usage and behavioral patterns in an online research ethics course. Comput. Educ.4:100120. doi: 10.1016/j.caeai.2022.100120

23

Toomla K. Xiaojing W. Kikas E. Malleus-Kotšegarov E. Aus K. Azevedo R. et al . (2025). “Measuring (meta)emotion, (meta)motivation, and (meta)cognition using digital trace data: a systematic review of K-12 self-regulated learning,” in Proceedings of the 40th ACM/SIGAPP Symposium on Applied Computing (Italy: ACM SAC). doi: 10.1145/3672608.3707961

24

Uglev V. Smirnov G. (2024). A cross-cutting approach to analysis of the learning situation in ITS using a mapping mechanism. J. Integr. Des. Process Sci.27, 288–303. doi: 10.1177/10920617241289777

25

Valle N. Antonenko P. Valle D. Dawson K. Huggins-Manley A. C. Baiser B. (2021). The influence of task-value scaffolding in a predictive learning analytics dashboard on learners' statistics anxiety, motivation, and performance. Comput. Educ.173:104288. doi: 10.1016/j.compedu.2021.104288

26

Wong J. Baars M. Davis D. Van Der Zee T. Houben G.-J. Paas F. (2019). Supporting self-regulated learning in online learning environments and MOOCs: a systematic review. Int. J. Hum. Comput. Inter.35, 356–373. doi: 10.1080/10447318.2018.1543084

27

Yang C. C. Y. Wu J. Y. Ogata H (2025). Learning analytics dashboard-based self-regulated learning approach for enhancing students' e-book-based blended learning. Educ. Inf. Technol.30, 35–56. doi: 10.1007/s10639-024-12913-7

28

Zimmerman B. J. Schunk D. H. (2001). “Self-regulated learning and academic achievement,” in Theoretical Perspectives (Routledge).

Summary

Keywords

artificial intelligence, higher education, learning analytics, meta-synthesis, open learner models, pedagogical strategies, self-regulated learning

Citation

Robles Mucho JL, Andrade-Girón DC, Benites-Tirado VR, Quispe-Maquera NB, Ayala-Jara C, Tito Chura HE, Luna-Victoria FM, Laura-De La Cruz KM, Rivera-Lozada O, Cerna Salcedo AA, Jaramillo Arica PS and Barboza JJ (2026) Open learner models and pedagogical strategies in higher education: a meta-synthesis of approaches to self-regulated learning. Front. Educ. 10:1760183. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2025.1760183

Received

03 December 2025

Revised

23 December 2025

Accepted

29 December 2025

Published

26 January 2026

Volume

10 - 2025

Edited by

Sergio Ruiz-Viruel, University of Malaga, Spain

Reviewed by

Isabela-Anda Dragomir, Nicolae Bălcescu Land Forces Academy, Romania

Aleksandra Tłuściak-Deliowska, The Maria Grzegorzewska University, Poland

Updates

Copyright

© 2026 Robles Mucho, Andrade-Girón, Benites-Tirado, Quispe-Maquera, Ayala-Jara, Tito Chura, Luna-Victoria, Laura-De La Cruz, Rivera-Lozada, Cerna Salcedo, Jaramillo Arica and Barboza.

This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Joshuan J. Barboza, bmecajos@uss.edu.pe

Disclaimer

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.