Abstract

Microplastics are <5 mm in size, made up of diverse chemical components, and come from multiple sources. Due to extensive use and unreasonable disposal of plastics, microplastics have become a global environmental issue and have aroused widespread concern about their potential ecological risks. This review introduces the sources, distribution and migration of microplastics in agricultural soil ecosystems. The effects of microplastics on soil physicochemical properties and nutrient cycling are also discussed. Microplastics can alter a series of key soil biogeochemical processes by changing their characteristics, resulting in multiple effects on the activities and functions of soil microorganisms. The effects of microplastics on soil animals and plants, the combined effects of microplastics and coexisting pollutants (organic pollutants and heavy metals), and their potential risks to human health are also discussed. Finally, prevention and control strategies of microplastic pollution in agricultural soil ecosystems are put forward, and knowledge gaps and future research suggestions about microplastic pollution are given. This review improves the understanding of environmental behavior of microplastics in agricultural soil ecosystems, and provides a theoretical reference for a better assessment of the ecological and environmental risks of microplastics.

1 Introduction

The invention of plastic is an important innovation in material field. With the advancement of its production technology, the advantages of plastics in economy, efficiency, and substitutability have become more obvious. There are many types of plastic products that have become an important part of daily production and life. According to statistics, the cumulative global production of plastics has reached 8.3 billion tons (PlasticsEurope, 2019). However, only about 20% of plastics are recycled, while the remaining 80% are eventually accumulated in soil, rivers, and ocean environment (Trevor, 2020). The plastic wastes that accumulate in environment are broken down into smaller fragments and particles under physical, chemical or biological action, gradually forming microplastic (MP) particles that are <5 mm in size (Thompson et al., 2004). MPs are classified according to their origin, with primary MPs originally manufactured in sizes smaller than 5 mm, while secondary MPs are derived from the fragmentation of larger plastics or primary MPs (Akdogan and Guven, 2019). MPs may accumulate, migrate and diffuse in environment due to their strong hydrophobicity, small particle size, large specific surface area, and stable chemical properties and carrying other environmental pollutants (such as antibiotics and heavy metals). MP pollution has become a new type of environmental problem faced by the world (Alimi et al., 2018; Kumar et al., 2020; Karbalaei et al., 2018; Moreno-Jiménez et al., 2022; Rillig and Lehmann, 2020). Soil is one of the most precious resources on Earth, providing a range of important ecosystem functions and services for humans and other organisms. Due to human activities, such as plastic mulching (Huang et al., 2020), sewage irrigation (Li et al., 2018), soil amendment application (Weithmann et al., 2018; Vithanage et al., 2021), fertilizer coatings (Bian et al., 2022), and littering (Yang L. et al., 2021), and environmental media, such as runoff (Nizzetto et al., 2016a) and air (Dris et al., 2016) transmission (Figure 1), soil has become the largest reservoir of MPs, which may be 4 to 23 times that of the ocean (Nizzetto et al., 2016b). Furthermore, MPs are more abundant in agricultural soils rather than in urban soils. Therefore, it is vitally important to evaluate ecological and environmental risks of microplastics in agroecosystems.

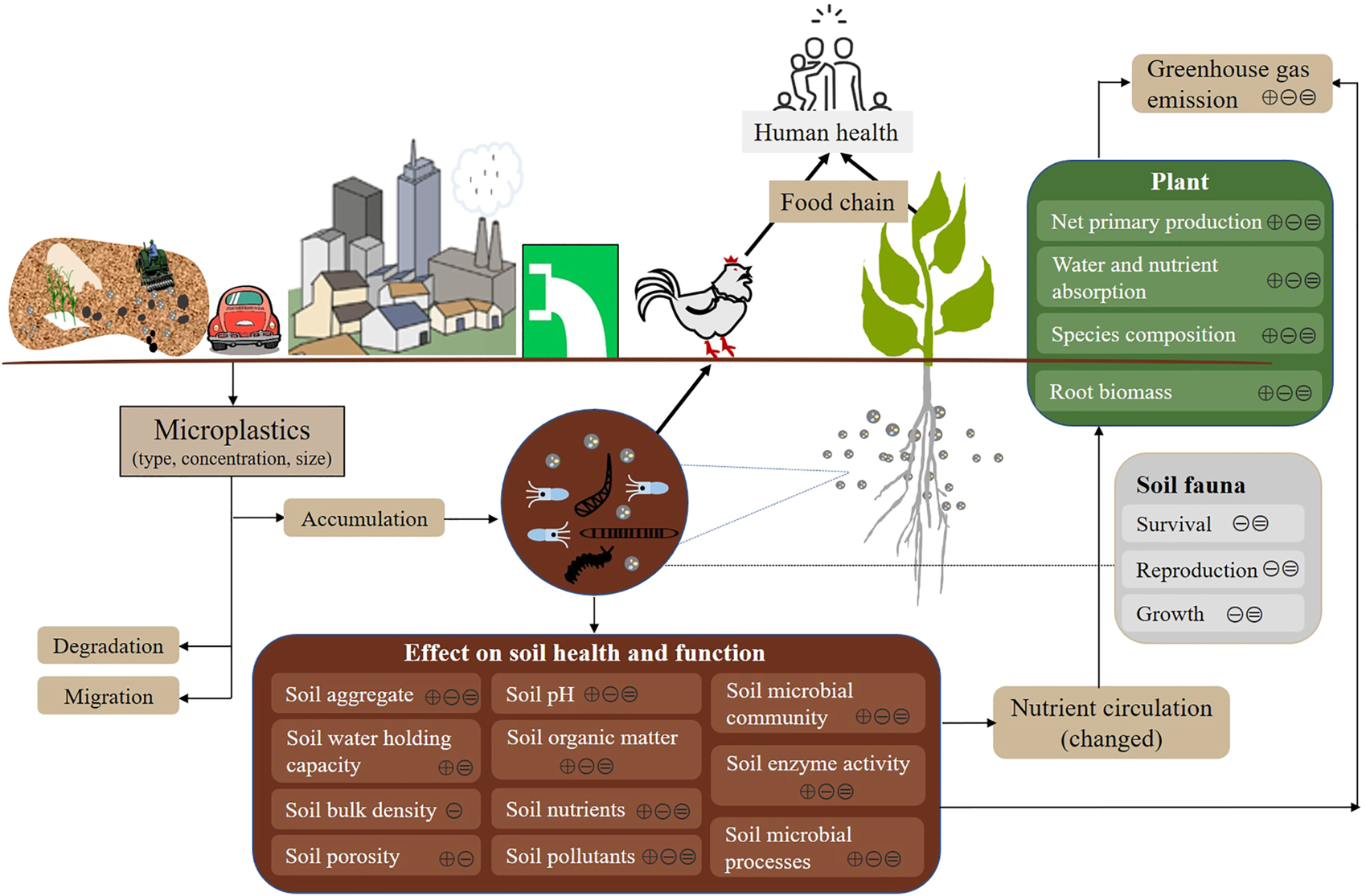

FIGURE 1

Sources of microplastics in agricultural soils and their impacts on the ecological environment. The symbols of⊕, ⊝and⊜ represent positive, negative and insignificant effects of MPs, respectively.

After entering soil environment, MPs are dispersed in soil matrix under the effects of dry and wet cycles, soil management measures, and biological disturbances (O’Connor et al., 2019), thereby changing soil physicochemical properties, including its changing C, N, and P content and pH (Zhang D. et al., 2020; Qi et al., 2020; Wang F. et al., 2022). Under the action of MPs, soil enzyme activities may be inhibited or activated (Awet et al., 2018; de Souza Machado et al., 2018, 2019; Qian et al., 2018; Fei et al., 2020; Yu et al., 2020; Guo et al., 2021; Wang F. et al., 2022; Ren et al., 2022). MPs also affect soil microorganisms, inhibit or activate microbial activities, and affect microbial diversity and community structures (Liu et al., 2017; Awet et al., 2018; de Souza Machado et al., 2018; Hou et al., 2021). In addition, MPs release chemical additives and can adsorb various toxic substances, further aggravating soil pollution and affecting soil properties (Hahladakis et al., 2018; Zhang Z. et al., 2021). MPs affect the normal metabolic activities of soil organisms through physical and chemical toxic effects and multiple carriers, affect ecosystem health and service functions, and pose potential threats to human food safety, thereby causing harm to human health (Senathirajah et al., 2021).

At present, the impact of MPs on soil ecosystem has become a research hotspot. Recent findings revealed the prevalence and persistence of MPs in soil, and the effects of MPs on soil physical, chemical and biological properties, and the toxicological effects of MPs on the growth, reproduction, survival, and immunity level of the soil biota (animals, plants, and microorganisms) (Wang F. et al., 2022; Hartmann et al., 2022; Okeke et al., 2022; Ren et al., 2022). However, overall research on MP pollution in agricultural soils is still in an embryonic stage, and few comprehensive reviews systematically summarize the ecological and environmental risks of MPs in agricultural soils. Given that MPs are more abundant in agricultural soils than in urban soils, there is an urgent need to systematically analyze the ecological and environmental risks of MPs in agricultural soils to draw attention to MPs in agroecosystems.

The present review begins with a summary of the source, characteristics, migration discipline and degradation of MPs in agricultural soils. Then we highlight the hazard of MPs on agricultural soil ecosystems, including the effects on soil physical and chemical properties, soil animals, plants and microorganisms and discuss the risks of MPs to human health. Finally, prevention and control strategies of microplastic pollution in agricultural soil ecosystems are put forward, and knowledge gaps and future research suggestions about microplastic pollution are given.

2 Source and Migration of Agricultural Soil Microplastic(s)

The sources of MPs in agricultural soils mainly include soil amendments application, plastic film mulching, fertilizer and pesticide packaging wastes, wastewater irrigation, runoff, and atmospheric deposition (Horton et al., 2017; Chae and An 2018; He et al., 2019; Lu et al., 2019; Chen W. L. et al., 2020; Zhou B. et al., 2020; Han et al., 2021; Okeke et al., 2022).

2.1 Sources of Microplastic(s) in Agricultural Soil

2.1.1 Sludge and Compost Products

Sludge and compost products contain a large amount of MPs, and they are often applied to soil as an amendment, resulting in abundant MPs entering soil environment (Blasing and Amelung 2018; Weithmann et al., 2018). The content of microplastics in soil is positively correlated with the duration and dosage of sludge application (Corradini et al., 2019). Blasing and Amelung (2018) estimated that the application of 7 t hm−1 and 35 t hm−1 compost products can lead to the input of MPs reaching 0.016–1.2 kg hm−1 and 0.08–6.3 kg hm−1 in cultivated land, respectively. The annual flux ranges of MPs in European and North American farmlands from sewage-sludge applications are estimated to be 63,000–430,000 and 44,000–300,000 tons, respectively (Nizzetto et al., 2016b).

2.1.2 Plastic Film Mulching

Plastic films are widely used because they could regulate soil temperature and increase water use efficiency, thereby promoting and improving crop growth and quality. More than 128,652 km2 of agricultural land in the world is covered with plastic films (Briassoulis and Giannoulis, 2018). Plastic film residues are broken down into small fragments under the action of weathering, ultraviolet radiation and mechanical farming, and thus enter the soil environment causing MP pollution. Mulched soils have more plastic films than non-mulched soils (Zhou B. et al., 2020). There is a significant linear correlation between the consumption of plastic films and the amount of soil plastic residues, and the concentrations of soil MPs of continuous film mulching for 5, 15, and 24 years are 80.3 ± 49.3 pieces kg−1, 308 ± 138.1 pieces kg−1, and 1,075.6 ± 346.8 pieces kg−1, respectively (Huang et al., 2020). Plastic film mulching is considered of being a key microplastic source in terrestrial ecosystems because of its widespread use, lack of plastic waste residues and inappropriate handling (Qadeer et al., 2021). In addition, dust-proof nets have also become one of the sources of soil MPs (Lu et al., 2019; Chen et al., 2021). For example, the abundance of MPs in soil covered by dust-proof nets ranges from 272 to 13,752 pieces kg−1 in Beijing, China, and the dominant MP types are polyethylene (50.12%) and polypropylene (41.25%) (Chen et al., 2021).

2.1.3 Sewage Irrigation

It is estimated that about 20 million hm2 of farmland in 50 countries are directly irrigated with partially treated or untreated sewage (Carter et al., 2019). Untreated sewage contains a large amount of MPs. Even after treatment, 1% of MPs in sewage still flow into the natural environment (Carr et al., 2016). Regardless of whether the sewage is treated or not, it is estimated that 1.5 × 104 4.5 × 106 MPs are discharged into the environment every day (Hoellein et al., 2016). The main sources of these MPs are textile fibers from household washing machines and personal care products, such as toothpaste, soap, and facial scrubs (Napper et al., 2015; Carr et al., 2016). In eastern Spain, the abundance of MPs in farmland with sewage irrigation is 5,190 pieces kg−1, while that in farmland without sewage irrigation is 2030 pieces kg−1 (Nizzetto et al., 2016a; van den Berg et al., 2020).

2.1.4 Other sources

Other sources of MPs in agroecosystems include plastic bag residues and containers (for fertilizers and agrochemicals), domestic wastes, mismanaged solid waste landfills, atmospheric deposition, and tire wear (Dris et al., 2016; Wang W. et al., 2020; Zhou B. et al., 2020). For example, the annual input of MPs in Paris due to atmospheric deposition is as high as 10 tons (Dris et al., 2016). The annual tire dust emission in Sweden is as high as 10,000 tons, and in Germany it even reaches 110,000 tons (Blasing and Amelung, 2018). The bottom ash from waste incineration is also an important source of MPs, and about 360–102,000 particles MPs are produced per ton of waste incineration (Yang et al., 2020). MPs from these sources can enter agricultural soils through atmospheric transport and runoff.

2.2 Distribution of Microplastic Abundance

MPs are widely found in agricultural soils, and there are significant differences in their abundance in different regions (Table 1). Fragments, films, and fibers are common shapes of MPs in agricultural soils, and PP, PE, and PET account for a large proportion of MPs (Ding et al., 2020; Wang J. et al., 2021; Choi et al., 2021; Feng et al., 2021). The abundance of MPs in agricultural soils is closely related to plant types and climatic factors (Ding et al., 2020). The MP content in soil of grain land soils in eastern Spain is 2,130 ± 950 particles kg−1 (van den Berg et al., 2020), while that in soil of vegetable field soils in the southeast is 2,116 ± 1,024 particles kg−1 (Beriot et al., 2021). The concentrations of MPs in vegetable, rice, corn, and fallow soils along the lower reaches of the Yangtze River in China are 41.7 particles kg−1, 32.2 particles kg−1, 51.5 particles kg−1 and 28.4 particles kg−1, respectively (Cao et al., 2021). The different planting types in central, northern and southern Shaanxi Province, China, resulted in significantly higher abundance of MPs in agricultural soils in northern region than in central and southern region. And due to the heavy rainfall and high temperature in south region, the agricultural soil is dominated by MPs of small size (0–0.49 mm) (Ding et al., 2020). The abundance of MPs decreases with an increase in soil depth. For example, the abundance of MPs in the shallow and deep soils of vegetable plots is 78.0 particles kg−1 and 62.5 particles kg−1, respectively (Liu et al., 2018), and the contribution of MPs with sizes <0.5 mm in the 10–25 cm layer of facility agricultural soils is significantly higher than that in the 0–5 cm soil layer (Yu L. et al., 2021). The distribution of MPs in soil is also related to soil texture. For example, their abundance in sandy loam is higher than that in clay loam or loam (Yu L. et al., 2021).

TABLE 1

| Site | Land use | Main sources | Sampling depth (cm) | Concentrations (p kg−1) | Sizes (mm) | Shapes | Polymer types | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Shaanxi | — | SA, WI, MF | — | 1,430–3,410 | 0–0.49 (81%) | Fiber, fragment, film | PS, PE, PP, PVC, PET | Ding et al. (2020) |

| China | ||||||||

| Hebei, Shandong, Shaanxi, Hubei | Wheat land | SA, WI, MF | — | 3,910 ± 1,031 | <5 | Fiber, fragment, film, sphere | PVC, PA, PP, PS, PE, Acr, polyester | Wang et al. (2021a) |

| Jilin | Paddy land | 5,490 ± 573 | <1 mm (80%) | |||||

| Orchard land | 3,386 ± 593 | — | ||||||

| China | Mulching land | 5,386 ± 835 | — | |||||

| Greenhouse land | 5,124 ± 632 | — | ||||||

| Shihezi | Cotton fields | MF(5,15, 24y) | 0–40 | 80.3 ± 49.3 | <5 | Fragment | PE | Huang et al. (2020) |

| China | 308 ± 138.1 | |||||||

| 1,075.6 ± 346.8 | ||||||||

| Qinghai–Tibet Plateau, China | Farmland | MF, WI, LI | 0–3 | 53.2 ± 29.7, 43.9 ± 22.3 | <0.5 (66.27%) | Film, fragments, fibers, foams, spherules | PP, PE, PS, PA, and others | Feng et al. (2021) |

| Mulching land | 3–6 | <0.5 (78.31%) | ||||||

| Greenhouse land | — | — | ||||||

| Enshi, China | Tobacco field | MF, SA, OF | 0–20 | 646.67–2,840 | ≤1.0 (55.20–71.85%) | Fragment, film, fiber, foam, pellet | — | Zhang et al. (2021a) |

| Kunming | Vegetable land | SA, WI, MF | 0–5, 5–10 | 13,470–42,960 | 0.05–0.25 (82%) | Film, fragment | — | Zhang and Liu, (2018) |

| China | ||||||||

| Harbin | Vegetable land | MF | 0–20 | 50 ± 87–400 ± 692 | 0.05–5 | — | PE | Zhang et al. (2020b) |

| China | corn land | 20–30 | ||||||

| Wuhan | Vegetable land | SA, WI, MF, LI | 0–5 | 4.3 × 104–6.2 × 105 | 0.01–0.1 (81.7%) | Fragment, fiber, pellet, film, foam | PE, PA, PP, PS, PVC and others | Zhou et al. (2019) |

| China | ||||||||

| Wuhan | Vegetable land | SA, MF | 0–5 | 320–12,560 | <0.2 (70%) | fiber, pellet, fragment, foam | PA, PP, PS, PE, PVC | Chen et al. (2020b) |

| China | ||||||||

| Hangzhou Bay, China | Vegetable land | SA, WI, MF, LI | 0–10 | 571 (mulching) | 0.06–5 | Film, fiber, fragment and others | PE, PP, PA, PES, Acr, nylon, and others | Zhou et al. (2020a) |

| 263 (non-mulching) | 1–3 (60%) | |||||||

| Shouguang | Vegetable land | MF, LI, OF, RO | 0–5 | 275–5,411 | <0.5 (65.2%) | Fiber, fragment, film, pellet, foam | PP, EPC, PE, PS, PES, PU, ABS, PMMA, and others | Yu et al. (2021a) |

| China | 5–10 | 179–7,175 | ||||||

| 10–25 | 307–4,507 | |||||||

| Mellipilla | corn land | SA | 0–25 | 600–10,400 | <5 | Fiber | — | Corradini et al. (2019) |

| Chile | ||||||||

| Ontario | — | SA | 0–15 | 4–541 | >0.3 | Fiber, fragment | PS, PE, PP, PES, Arc, PU, PA, PMMA, and others | Crossman et al. (2020) |

| Canada | ||||||||

| Southeast Germany | — | — | 0–5 | 0.34 ± 0.36 | 1–5 | Film, fragment, fiber | PE, PS, PP | Piehl et al. (2018) |

| Schleswig-Holstein | winter rapeseed—winter wheat—winter barley | WI, OF | 0–10 | 0–217.8 | 1–5 | Fragment, fiber, film | PE, PP, PA, others | Harms et al. (2021) |

| Germany | 10–20 | |||||||

| 20–30 | ||||||||

| Fars | — | MF | 0–10 | 156 ± 153–400 ± 305 | 0.040–0.74 | — | Light density (LD) MPs | Rezaei et al. (2019) |

| Iran | ||||||||

| Valencia | Cereal field, olive field | SA, others | 0–10 | no SA:930 ± 740 (LD) | >0.05 | Fragment, fiber, film | LD or high density (HD) MPs | van den Berg et al. (2020) |

| — | — | 1,100 ± 570 (HD) | ||||||

| — | — | SA:2,130 ± 950 (LD) | ||||||

| 3,060 ± 1,680 (HD) | ||||||||

| Yeoju, Korea | Orchard field, greenhouse field, paddy field, upland | MF, CT, AD | 0–5 | 664–3,440 | <5 | Fragment, film, fiber, pellet | PE, PP, PS, PVC | Choi et al. (2021) |

| Yong-In, Korea | Paddy land | MF, LI | 0–5 | 20–325 | <5 | Fragment, fiber, sheet | PE, PP, PET | Kim et al. (2021) |

| Mulching land | 10–265 | |||||||

| Greenhouse land | 75–7,630 |

Summary of MP pollution in agricultural soil.

The abbreviations used in this table are as follows: sludge application (SA), organic fertilizer (OF), wastewater irrigation (WI), mulching film (MF), littering (LI), car tires (CT), atmospheric deposition (AD), runoff (RO).

2.3 Migration and Degradation of Soil Microplastic(s)

Soil characteristics (such as soil cracks and pores), soil biota (such as fungi, bacteria, plants and animals), soil management (cultivation and harvesting), and climatic conditions (dry and wet alternate, freeze-thaw, wind, air currents, etc.,) affect the horizontal and vertical migration of MPs in soil (Zhu B.-K et al., 2018; Al-Jaibachi et al., 2019; Yu et al., 2019; Zhang et al., 2019). Soil is a porous medium with macropores and cracks, and small plastic particles can easily migrate through the soil profile (Blasing and Amelung, 2018). Soil fauna, such as earthworms, mites, and bouncing bugs, transport MPs through feeding and burrowing behaviors (Huerta Lwanga et al., 2016; Maass et al., 2017). MPs can be swallowed by earthworms and excreted from their body. MPs can also be transported from shallow to deep soils through earthworm burrows (Huerta Lwanga et al., 2016; Rillig et al., 2017a). MPs can be moved by Folsomia candida and Proisotoma minuta; the larger Folsomia candida transports larger MPs farther and faster than the smaller Proisotoma minuta (Maass et al., 2017). Mites, bullet tails, gophers and moles can scrape or chew to disperse and redistribute MPs (Rillig, 2012; Maass et al., 2017; Zhu D et al., 2018). The growth of plant roots can also affect MP migration. For example, corn roots produce more soil pores and gaps, which are conducive for the upward movement of MPs in the middle soil (7–12 cm) (Li H. et al., 2021). Tillage activities, such as tilling and ridging, could turn over surface and deep soils, directly contributing to the movement of microplastics (Piehl et al., 2018). Furthermore, wetting-drying cycle can accelerate the downward migration of MPs. The smaller the particle size, the higher the dry-wetting cycle frequency and the faster the vertical migration speed (O’Connor et al., 2019).

In addition to migrating in soil, MPs in soil can also migrate to surrounding environmental media, like air and water, through runoff, erosion and wind. MPs migrate through soil pore infiltration (<4%) and surface soil-water loss (>96%) (Zhang S. et al., 2020). Runoff allows soil MPs enter rivers and coastal waters, thereby causing potential impacts on aquatic ecosystems (Nizzetto et al., 2016a; Wang W. et al., 2020). MPs on the soil surface can be suspended in the atmosphere by wind and may become a component of PM2.5; they can also be transported through atmospheric circulation and become an important source of MPs in glaciers and lakes in remote areas (Zhang et al., 2019; Zhang Y. et al., 2021).

In addition, MP properties (such as hydrophobicity, degree of surface weathering and size, etc.,) affect their migration. It has been proven that the penetration depth of PE-MPs in soil is much higher than that of PP-MPs (O’Connor et al., 2019). MPs containing -COOH functional groups are easier to migrate than those containing -NH2, and hydrophilic polystyrene particles have greater mobility than hydrophobic polystyrene particles (Dong et al., 2019). Microbeads and microfibers also exhibit different interactions with soil aggregates (de Souza Machado et al., 2018), which may cause differences in migration in soil.

3 Effects of Microplastic(s) on Agricultural Soil Ecosystems

MPs that are widely distributed in agricultural soils can affect soil physicochemical properties, reduce soil fertility, and even alter soil microbial community, thereby affecting soil quality and nutrient cycling. During the manufacturing and processing of plastic products, various additives (such as plasticizers, flame retardants, and stabilizers) are used to improve product performance and applications. After long-term exposure to the natural environment, these additives are slowly released into soils, causing adverse effects on soil microbial diversity and functions (Hahladakis et al., 2018). In addition, MPs can adsorb various pollutants, including PAHs, PCBs, DDTs, HCHs, PPCPs, PFASs and heavy metals, and act as carriers for their migration in environment (Hartmann et al., 2017; Huffer et al., 2019), thereby further affecting the health of soil ecosystems. MPs can affect soil physicochemical properties, enzyme activities, microbial communities, soil animals, and plant growth, and these effects can be positive, negative, or insignificant (Figure 1), which can be attributed to variations in MPs (e.g. polymer type, content, size, and shape), soil properties, and exposure time.

3.1 Effects of Microplastic(s) on Soil Physicochemical Properties and Nutrient Cycling

After entering soil, MPs agglomerate with SOM and microbial secretions and become embedded in the microstructure of the soil (Rillig et al., 2017b), affecting soil physicochemical properties by increasing its porosity and water holding capacity, reducing its bulk density and moisture permeability (de Souza Machado et al., 2018, 2019; Zhang D. et al., 2020), destroying its structural integrity (Huerta Lwanga et al., 2017; Wan et al., 2019), and changing its structure (Zhao et al., 2021). MPs can also increase or decrease soil pH. For example, PA-MPs and HDPE-MPs can increase soil pH (Yang W. et al., 2021), while PS-MPs and PTFE can lower it (Dong et al., 2021a). The effect of MPs on soil properties is related to plant species. For example, research has found that PCF-MPs in corn crop ZNT 488 significantly increased soil pH and EC, and had no significant impact on SWC and DOC, while corn crop ZTN 182 significantly reduced SWC, pH, EC, and DOC (Lian et al., 2021).

MPs can change the cycle of soil nutrients (such as C, N, and P) (Liu et al., 2017; Zhang D. et al., 2020). Liu et al. (2017) found that high-concentration PP-MPs (28% w/w) significantly increased the accumulation of SOM and promoted the release of soil nutrients, such as DOC, DON, and DOP. In contrast, low-concentration MPs (7% w/w) had no significant effect on DOM solutions in 0–7 days, but these significantly increased the soil nutrient contents during 14–30 days. MPs exerted stronger effects on the dynamics of soil nutrients cycling (Meng et al., 2021). MPs may reduce the content of SOM, available P, alkaline N, and available K (Zhang D. et al., 2020; Dong et al., 2021a; Wang F. et al., 2022), thereby impairing soil health. Among different soil aggregate fractions, MPs have different effects on soil fertility. For example, polyester microfibers changed TOC concentration in large (>2 mm) and small (2–0.25 mm) aggregate fractions, but these did not change concentration of TOC in micro-aggregate fractions (0.25–0.05 mm) (Zhang and Zhang, 2020). MPs themselves have a high C content (almost 90% of PE or PS is C), so they can contribute to soil C storage (Rillig, 2018).

Alterations in soil physicochemical properties and nutrient element cycle by MPs in agricultural ecosystems lead to unpredictable impact on greenhouse gas emissions. Studies showed that MPs have different effects on soil CO2, N2O and CH4 emissions (Ren et al., 2020; Sun et al., 2020; Gao B. et al., 2021; Yu et al., 2021b). In the context of straw incorporation, MPs reduce the mineralization and decomposition of SOC, and reduce CO2 and N2O emissions (Yu et al., 2021b). In view of the importance of greenhouse gases to global warming and climate change, the potential impact of different MPs on greenhouse gas emissions should be an integral part of future soil ecological impact assessment.

3.2 Effects of Microplastic(s) on Soil Enzyme Activities

Soil enzymes are closely related to various soil biological and biochemical processes, and play an important role in regulating the cycle of soil nutrients, such as C, N, and P (Burns et al., 2013). These can also be used to assess the status of soil fertility (Bandick and Dick, 1999), which can give early warning signs of soil ecosystem changes. Therefore, many studies reported the effect of MPs on soil enzyme activities, which have large differences in existing studies. MPs may inhibit or activate enzyme activities or have no significant effect on enzyme activity. MPs significantly reduced the activities of FDAse, dehydrogenase, and urease (Yi et al., 2020; Yu et al., 2020) and reduced the dehydrogenase activity and activities of enzymes involved in N-(leucine-aminopeptidase), P-(alkaline-phosphatase), and C-(beta-glucosidase and cellobiohydrolase) cycles in the soil (Awet et al., 2018). The effect of MPs on soil enzyme activities depend on their concentration. Liu et al. (2017) found that high-concentration PP-MPs (28% w/w) could activate the activities of FDAse and phenoloxidase, while low-concentration PP-MPs (7% w/w) had no significant effect. High-dose (2% w/w) PLA-MPs, PBS-MPs, and PHB-MPs increased the activities of urease, phosphatase, and catalase; low-dose MPs (0.2% w/w) decreased the activity of phosphatase, but did not change the activities of urease and catalase (Feng et al., 2022). Then, the impacts of MPs also depend on polymer type. PE-MPs could activate urease and catalase activities but had no significant effect on sucrase activity (Huang et al., 2019). Both PVC-MPs and PE-MPs had inhibitory effects on FDAse activity, but had activating effects on urease and acid phosphatase activities (Fei et al., 2020). Furthermore, the shape of MPs also determines the effect of MPs on soil enzyme activity. For example, the effect of fiber PP-MPs on urease and alkaline phosphatase activities is stronger than that of microsphere PP-MPs, while the effect on dehydrogenase is opposite (Yi et al., 2020). The effects of MPs on soil enzyme activities vary with exposure time. Chen et al. found that PA-MPs had no significant effect on urease, catalase, and β-glucosidase activities during a 70-day incubation period, but these significantly reduced the soil enzyme activity in the first 20 days (Chen H. et al., 2020). In short, the degree and direction of the effects of MPs on soil enzyme activities depend on the type, concentration, size, and shape of MPs as well as the soil environment and other factors, and their mechanism of influence is complex.

3.3 Effects of Microplastic(s) on Soil Microorganisms

The effects of MPs on soil are diversified; these can not only change the soil microenvironment but also further affect the soil microbial community and diversity. Different types of MPs have different degrees of influence on soil microorganisms. For example, PE-MPs and PVC-MPs significantly reduce the abundance and diversity of microbial communities, and the degree of influence of PE is stronger than that of PVC (Fei et al., 2020). Different concentrations of soil MPs have different effects on microbial activities. Low concentrations of MPs reduce soil microbial activity, while high concentrations increase it (Kumar et al., 2020). The effects of MPs on soil microorganisms vary with exposure time. MPs increase the richness and diversity of bacterial communities at the beginning of incubation and decrease these at the later stages (Ren et al., 2020). Studies have also found that MPs have no significant effect on the diversity and activity of microbial communities (Judy et al., 2019; Blöcker et al., 2020; Chen H. et al., 2020). Huang et al. (2019) found that PE-MPs did not significantly change the α diversity of soil microbial communities, and the diversity index of microbial communities on MPs was significantly lower than that of soil. These inconsistent effects can be attributed to variations in MP (e.g. polymer type, content, size, and shape), soil properties and exposure time.

MPs may serve as novel ecological habitats for microorganisms living in soil-plastic interface (i.e., microplastisphere), thereby forming unique microbial communities (Zhou et al., 2021a; Yu et al., 2021c). MPs can enrich specific microbial communities and affect the interaction between plants and microorganisms, forming microbial hotspots on MP surfaces (Zang et al., 2020; Zhou et al., 2021a; Yu et al., 2021c). Zettler et al. (2013) found that the abundance of bacterial communities on MPs was much higher than that of surrounding environment, and these microorganisms are important for ecosystem processes involving C or S cycles (Xie et al., 2021). MPs enrich the microbial communities involved in self-degradation (Huang et al., 2019; Hou et al., 2021). For example, Chloroplast, Cladosporiaceae, Tremellales, Didymellaceae, and Filobasidiaceae are significantly abundant on microplastic surfaces (Yu et al., 2021c). PHBV-MPs increase the abundance of oligotrophic microorganisms and reduce fast-growing vegetative microorganisms (Zhou et al., 2021a). MPs can provide new microbial niches promoting the proliferation of specific microbial groups, which may have unpredictable consequences on ecosystem functions.

In summary, there are two main ways that MPs affect soil microbial communities. On the one hand, the living environment of microorganisms is altered by changing soil physicochemical properties, thereby affecting the microbial community. On the other hand, MPs serve as novel ecological habitats for microorganisms, or the release of plasticizers affects their growth.

3.4 Effects of Microplastic(s) on Plants

MPs may induce a widespread toxic effect on many physiological and biochemical processes in plants, such as delaying or reducing seed germination, inhibiting plant growth, changing root traits, reducing biomass, delaying and reducing fruit yield, interfering with photosynthesis, causing oxidative damage and producing genotoxicity (Qi et al., 2018; Boots et al., 2019; Bosker et al., 2019; Yu et al., 2021d; Hernandez-Arenas et al., 2021). MPs can affect plant growth and performance through various different mechanisms, including: 1) direct toxicity to plants, mainly NPs; 2) indirect effects on plant growth through changes in soil properties and microbial communities; and 3) direct toxicity of contaminants (e.g., plasticizers flame, retardants, antioxidants, and colorings, etc.,) present in MPs (Rillig et al., 2019).

3.4.1 Direct Toxicity of Microplastic(s) to Plants

On the one hand, MPs can affect plants through adsorption. For example, MPs may attach to plant roots and change their properties, thereby hindering the absorption of water and nutrients by plants. MPs with a small particle size are more toxic to plants (Jiang et al., 2019). On the other hand, NPs and MPs at submicrometer or micron levels may enter the plant body and cause harm by changing the state of cell membranes and intracellular molecules and causing oxidative stress (Giorgetti et al., 2020; Li et al., 2020; Gong et al., 2021; Yin et al., 2021; Liu et al., 2022). Both nano- and micro-sized MPs may accumulate in the interspace tissues of plant roots and then transfer to the leaves, stems, flowers, and fruits (Li Z. et al., 2021; Liu et al., 2022). In addition, MPs can also affect the absorption of other substances, such as Fe, Mn, Cu, and Zn, by plants (Lian et al., 2020a), and the phytotoxicity of MPs is clearly plant species-dependent (Gong et al., 2021).

3.4.2 Indirect Effects on Plants Through Changes in Soil Properties and Microbial Communities

The performance of plants depends on soil properties, soil biological community, and diversity to a large extent. MPs cause changes in soil physicochemical properties and microbial communities, which may change the rhizosphere, growth conditions and nutrient supply of plants, thereby indirectly affecting plants. For example, MPs significantly increase the rate of soil water evaporation, which may lead to soil drying (Wan et al., 2019), potentially negatively affecting plant performance. The presence of MPs may reduce soil fertility and cause plant nutrient loss. In addition, MPs can reduce soil microbial diversity or the abundance of rhizosphere fungal symbionts, which may cause subsequently decrease plant diversity (van der Heijden et al., 2016).

3.4.3 Direct Toxicity of Contaminants Present in Microplastic(s)

Plastics additives, such as plasticizers and flame retardants, or other environmental pollutants (organic pollutants and heavy metals) adsorbed on the surface of MPs can also affect plants (Wang W. et al., 2020). These chemical additives easily leach into the soil, resulting in adverse effects on plant growth. These adverse effects increase as the adsorption capacity of MPs increases, depending on the shape, polymer structure, degradation, additives, concentration and location of MPs (Lozano and Rillig, 2020; Zhou et al., 2021b; Okeke et al., 2022).

3.5 Effects of Microplastic(s) on Soil Fauna

It is well known that medium-sized fauna, such as earthworms, mites, and springtails, are essential in maintaining soil quality, but the impact of MPs on these key organisms may pose a significant threat to agroecosystem functions (George et al., 2017). MPs may be ingested by terrestrial organisms including ciliates, amoeba, flagellates, springtails and earthworms, leading to decreased survival and growth rates, intestinal damage, immune disorders, oxidative stress, neurotoxicity, DNA damage and abnormally expressed genes (Wang W. et al., 2020; Sarker et al., 2020; Wang Q. et al., 2021); these can even be transferred along the food chain (Huerta Lwanga et al., 2016). The adverse effects of MPs are mainly due to their large accumulation in the guts and stomachs of soil organisms, which can damage their immune system and affect their feeding behavior and development (Eltemsah and Bohn, 2019; Liu et al., 2019; Ding et al., 2021). MPs also damage the gut cells and DNA of earthworms (Jiang et al., 2020), and have harmful effects on invertebrate sperms (Kwak and An, 2021). In addition, MPs may also change the diversity and richness of the gut microbiome of soil animals, which may participate in the cycle of essential elements and SOM decomposition (Lu et al., 2018; Zhu D et al., 2018). The effects of MPs on animals are closely related to the exposure concentration, shape, size, type and additives of MPs (Huerta Lwanga et al., 2016; Lambert et al., 2017; Wang H.-T. et al., 2019; Chen et al., 2020d; Li B. et al., 2021).

3.6 Combined Effects of Microplastic(s) and Toxic Substances

3.6.1 Toxic Substances Released by Microplastic(s)

Most plastic products contain various additives, such as plasticizers, flame retardants, antioxidants, light and heat stabilizers, lubricants, and pigments (Table 2), that are generally not chemically bound to plastic polymers and may be prone to leaching into the soil matrix (Hahladakis et al., 2018; Ge et al., 2021). The plastics in soil are subject to physical, chemical and microbial action to age or degrade, resulting in release of various harmful substances in additives, including phthalates, bisphenol A, polybrominated diphenyl ethers and heavy metals (Hahladakis et al., 2018). These substances have harmful effects on soil ecosystems. Studies showed that the toxicity soil MPs is related to their characteristics and extractable additives (Kim et al., 2020). For example, plasticizers significantly inhibit wheat seed germination, affect plant antioxidant enzyme activities, and induce programmed cell death in seed cells by changing relative gene expressions (Liu et al., 2013). In addition, when MPs and dibutyl phthalate (a common plasticizer) are exposed together, the cell wall separation in roots of lettuce is intensified and various root growth indicators, such as root vitality, total root length, total root number, root surface area, average root diameter and root hair number (Gao M. et al., 2021).

TABLE 2

| Additives | Typical concentrations (% w/w) | Substances | Description | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Functional additives | Plasticizer | 10–70 | Short and medium chain chlorinated paraffins (SCCP/MCCP); Diisoheptyl phthalate (DIHP); DHNUP; Benzyl butyl phthalate (BBP); Bis (2-ethylhexyl)phthalate (DEHP): Bis(2-methoxyethyl) phthalate (DMEP): Dibutyl phthalate (DBP); diisobutyl phthalate (DiBP); Tris (2-chloroethyl)phosphate (TCEP) | Improves the fluidity of plastics during processing and flexibility at room temperature. About 80% is used in PVC while the remaining 20% in cellulose plastic |

| Flame retardants | 3–25 (for brominated | Short, medium, long chain chlorinated paraffins (SCCP/MCCP/LCCP): Boric acid; Brominated flame retardants with antimony (Sb) as synergist [e.g. Polybrominated diphenyl ethers (PBDEs); Decabromodiphenyl ethane; TetraBromoBisphenol A (TBBPA)]; Phosphorous flame retardant (e.g. Tris (2-chloroethyl) phosphate (TCEP) Tris (2-chlorisopropyl) phosphate (TCPP)) | Reduce the flammability of material. Three groups: organic nonreactive, inorganic nonreactive, reactive | |

| Antioxidant stabilisers | 0.1–3 | Pentaerythritol tetrakis (3-(3,5-di-tert-butyl-4-hydroxyphenyl) propionate), butylated hydroxytoluene, tris(2,4-di-tert-butylphenyl) phosphite, triphenyl phosphate, distearyl 3,3′-thiodipropionate, 4,4′-dioctyldiphenylamin | Prevent oxidation and deterioration caused by heat | |

| Light stabilisers | 0.1–3 | Bis(1,2,2,6,6-pentamethyl-4-piperidyl) sebacate | Prevent oxidation and deterioration caused by light | |

| UV-absorbing stabilisers | 0.1–3 | Bumetrizole, 2-(2H-benzotriazol-2-yl)-4,6-ditertpentylphenol, oxybenzone, 2,2′,4,4′-tetrahydroxybenzophenone | Prevent the breakage of molecular bonds by UV light and radicals | |

| Thermal stabilisers | 0.5–3 | Cadmium and Lead compounds; Nonylphenol (barium and calcium salts) | Inhibit thermal degradation of vinyl chloride resin during processing. Mainly used in PVC. Based on Pb, Sn, Ba, Cd and Zn compounds. Pb is the most efficient and it is used in lower amounts | |

| Lubricants and slip agents | 0.1–3 | Fatty acid amides (primary erucamide and oleamide), fatty acid esters, metallic stearates (for example, zinc stearate), and waxes (for example, Paraffin, carnauba, montan) | Prevent adhesion of plastic to processing equipment, improve fluidity and reduce surface friction. Amounts depend on the chemical structure of the slip agent and the plastic polymer type | |

| Curing agents | 0.1–2 | 4,4′- Diaminodiphenylmethane (MDA); 2,2′-dichloro-4,4′- methylenedianiline (MOCA); formaldehyde—reaction products with aniline; hydrazine; 1,3,5-Tris (oxiran-2-ylmethyl)- 1,3,5-triazinane-2,4,6-trione (TGIC)/1,3,5-tris [(2S and 2R)- 2,3-epoxypropyl]-1,3,5- triazine-2,4,6-(1H,3H,5H)- trione (β-TGIC) | Peroxides and other crosslinkers, catalysts, accelerators | |

| Blowing (foaming) agents | Dependent on density of foam | Azodicarbonamide, benzene disulphonyl hydrazide (BSH), pentane, CO2 | Used in foam manufacturing to create cellular foam structure | |

| Biocides | 0.001–1 | Arsenic compounds; Organic tin compounds; triclosan | Prevents degradation of plastics from microorganisms, often used with other additives. Soft PVC and foamed polyurethanes are the major consumers of biocides | |

| Colorants | Soluble | 0.25–5 | 4,4′-diamino (1,1′-bianthracene)-9,9′,10,10′-tetraone | Enhance aesthetics and reduce light permeability |

| Organic pigments | 0.001–2.5 | Cobalt (II) diacetate | ||

| Inorganic pigments | 0.01–10 | Cadmium compounds; Chromium compounds; Lead compounds | ||

| Special effect | Varies with the effect and substance in question | Al and Cu powder, lead carbonate or bismuthoxichloride and substances with fluorescence | ||

| Fillers | 0–50% | Calcium carbonate, talk, clay, zinc oxide, glimmer, metal powder, wood powder, asbest, barium sulphate, glass microspheres, silicious earth | Increase bulk at low price and enhance a diversity of properties of the plastics, mainly stiffness, thermal and photo stability, and abrasion resistance | |

| Reinforcements | 15–30 | Glass fibers, carbon fibers, aramide fibers | Fibers added to improve mechanical properties. 15–30% is for glass only due to is high density | |

Additives used in plastics (Hahladakis et al., 2018; Barrick et al., 2021; Bridson et al., 2021).

3.6.2 Combined Effects of MPs and Environmental Pollutants

The toxicity of MPs to organisms in the environment is not just a single effect. Due to their large specific surface area and good hydrophobic properties, MPs could load other hydrophobic organic pollutants, such as polychlorinated biphenyls, polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons, petroleum hydrocarbons, and organochlorine pesticides, and heavy metals, affecting the migration, transformation, and other environmental behaviors of pollutants and affecting their toxic effects on soil organisms (Table 3). The toxic effects of MPs and coexisting environmental pollutants are considered to be another risk of MPs. When MPs and environmental pollutants coexist in an agricultural soil environment, the following three situations may occur.

TABLE 3

| Species | MPs | Exposure time | Pollutants | Ecological effects | Effect factors | References | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Type | Size | Concentration | ||||||

| Lettuce (Lactuca sativa) | PMFs | 2.55 mm (length) | 0.1%, 0.2% (w/w) | 2 months | Cd | Single PMFs and co-PMFs/Cd affected the physicochemical properties of lettuce, and altered the leaf metabolic profile of lettuce plant and key functional bacteria involved in the C, N cycles | Exposure dose | Zeb et al. (2022) |

| Wheat (Triticum aestivum L.) | PS | 0.5 µm | 100 mg/L | 8 days | Cu, Cd | PS had no effect on wheat seedlings growth, photosynthesis and ROS content, but reduced the bioavailability and toxicity of Cu and Cd. Co-exposure enhanced photosynthesis and reduced ROS accumulation | Exposure environment | Zong et al. (2021) |

| Soybean (Glycine max L. Merrill) | PS | 100 nm | 10 mg kg−1 | 30 days | Phe | MPs and phenanthrene co-exposure produced higher phytotoxicity and genotoxicity; PS decreased the uptake of phenanthrene in soybean and inhibited relative abundance of Proteobacteria in rhizosphere soil | Exposure dose, particle size | Xu et al. (2021) |

| 1 μm | ||||||||

| 10 μm | ||||||||

| 100 μm | ||||||||

| Carrots (Kurodagosun) | PS | 0.1–1 μm | 10–20 mg L−1 | 7 days | As (III) | Combined exposure of PS and As(III) causes greater PS to enter roots and leaves, more PS enter carrot tissues and results in greater health risks | Exposure dose | Dong et al. (2021b) |

| 5 μm | ||||||||

| Rice (Oryza sativa) | PTFE, PS | 10 μm | 0.04, 0.1, 0.2 g L−1 | 17 days | As (III) | Combined exposure of MPs and As(III) restrained rice growth, root activity, RuBisCO activity and photosynthesis; PS and PTEF decreased As(III) uptake of rice seedling | Exposure dose | Dong et al. (2020) |

| Wheat (Triticum aestivum L.) | PS | 100 nm | 10 mg L−1 | 21 days | Cd | PS decreased Cd content in leaves, enhanced carbohydrate and amino acid metabolism, and alleviated Cd toxicity to wheat, but had no significant effect on antioxidant enzyme activity | — | Lian et al. (2020b) |

| Maize (Zea mays L. var. Wannuoyihao) | PE, PLA | 100–154 µm | 0.1, 1, 10% (w/w) | 1 month | Cd | PLA decreased the biomass and chlorophyll content of maize; PE and PLA increased extractable Cd concentration; CO-exposure changed the structure and diversity of AMF community, plant performance and root symbiosis | Exposure dose, MPs type | Wang et al. (2020c) |

| Maize (Zea mays L. var. Wannuoyihao) | HDPE, PS | 100–154 µm | 0.1, 1, 10% (w/w) | 1 month | Cd | Combined exposure of MPs and Cd resulted in the increase of Cd phytotoxicity, the decrease of plant biomass, and the increase of extractable Cd concentration | Exposure dose, MPs type | Wang et al. (2020b) |

| Green lettuce, purple lettuce | PE | 23 μm | 0.25, 0.5, 1.0 mg ml−1 | 28 days | DBP | PE decreased DBP transport from the culture solution to the roots, thereby decreasing DBP content in roots and leaves | Plant species | Gao et al. (2021b) |

| Earthworm (Metaphire californica) | PVC | — | 2 g/kg | 28 days | As | PVC prevented the reduction of As(V) and accumulation of total arsenic in the gut which resulted in a lower toxicity on earthworm | Exposure environment | Wang et al. (2019a) |

| Earthworm (Eisenia fetida) | PE, PS | PE, ≤300 μm | 1, 5, 10, 20% (w/w) | 14 days | PAHs, PCBs | PE or PS particles increased the activity of catalase and peroxidase and the level of lipid peroxidation, while inhibited the activity of superoxide dismutase and glutathione S-transferase in E. fetida. MPs reduced bioaccumulation of PAHs and PCBs | Exposure dose | Wang et al. (2019b) |

| PS, ≤250 μm | ||||||||

| Earthworm (Eisenia foetida) | PP | <150 μm | 0.03, 0.3, 0.6, 0.9% | 42 days | Cd | Combined exposure to MPs and Cd posed higher negative effects on E. foetida, and MPs had the potential to increase the bioavailability of Cd | Exposure dose and times | Zhou et al. (2020b) |

| Earthworm (Metaphire vulgaris) | PE | NPs | 200, 45 mg kg−1 | 28 days | As | NPs reduced bioaccumulation of arsenic in the earthworm body. Exposure to arsenic and NPs caused shifts of ABG profiles in earthworm gut | — | Wang et al. (2022b) |

| Earthworm (Eisenia fetida) | PE | 30 μm | 0.1, 0.5, 1 mg/g | 21 days | Cu, Ni | PE enhanced the accumulation of metals in earthworms, and damaged earthworms | Exposure dose, particle size | Li et al. (2021d) |

| 100 μm | ||||||||

| mice (Mus musculus, CD-1) | PE, PS | 0.5–1.0 μm | 2 mg/L | 90 days | OPFRs | Co-exposure of MPs and OPFRs induced greater neurotoxicity and oxidative stress on mice compared with single OPFRs exposure, and enhanced disruption of amino acid metabolism and energy metabolism in mice | — | Deng et al. (2018) |

Combined effects of MPs and environmental pollutants.

Firstly, MPs increase the load and toxic effects of environmental pollutants on agricultural soil organisms. Due to the small particle size, large surface area and hydrophobic surface of MPs, environmental pollutants are easily enriched from surrounding environment, making their concentration in MPs hundreds or even thousands of times higher than that in surrounding environment (Zhao et al., 2020). In the process of co-exposure of MPs and environmental pollutants, MPs may transfer pollutants and increase their accumulation in organisms (Hodson et al., 2017; Zhou Y. et al., 2020), thereby promoting the toxicity of MPs and pollutants. The co-exposure of MPs and OPFRs induced greater neurotoxicity and oxidative stress in mice compared with a single OPFR exposure, and it also enhanced the disruption of amino acid metabolism and energy metabolism in mice (Deng et al., 2018). The combined exposure of MPs and heavy metals may lead to stronger phytotoxicity, including reducing plant biomass, affecting photosynthesis, inhibiting root activities, and causing oxidative damage (Wang et al., 2020b; Dong et al., 2020; Dong et al., 2021a).

Secondly, MPs may reduce the biological load and toxic effects of environmental pollutants. MPs alleviate the effects of arsenic on gut microbiota, possibly by adsorbing/binding As (V) and lowering the arsenic bioavailability; this prevents the reduction of As (V) and accumulation of total As in the gut. This indicates that the coexistence of MPs and arsenic may reduce the toxicity of arsenic on earthworms (Wang H.-T. et al., 2019). The interaction between PS-MPs and As reduces the bioavailability of As in soil, thereby inhibiting its effects on rice rhizosphere soil microorganisms (Dong et al., 2021b).

Thirdly, MPs have no significant effects on the accumulation and toxicity of environmental pollutants. When there is no interaction between MPs and environmental pollutants, their effects on organisms are independent. MPs have no obvious toxic effects on soil organisms, and the toxicity of environmental pollutants to organisms may remain unchanged.

4 Risks of Microplastic(s) to Human Health

Through direct absorption (through exposed/contaminated food and beverages-especially those from edible animals and drinks from plastics) or indirect absorption (through contaminated edible plants and animals), MPs move from a trophic level to another trophic level until they reach the top of the human food chain (Mercogliano et al., 2020). In the daily diet, a large number of MPs have been detected in various food/beverages, including honey and sugar (Liebezeit and Liebezeit, 2013), beer (Liebezeit and Liebezeit, 2014), and drinking water (Pivokonsky et al., 2018; Mintenig et al., 2019). In addition, 0.2 and 2 μm MPs can penetrate the roots of wheat and lettuce, and enter the leaves (Li et al., 2020). These studies indicate that MPs (especially NPs) may enter the seeds/fruits of crops and the human body through food intake. After entering the human body, MPs may cause adverse health effects through particle toxicity, chemical toxicity, pathogens, and parasite vectors (Vethaak and Leslie, 2016). Studies found that MPs can accumulate in the intestines after entering the human body. These may cause local inflammation, disrupt endocrine regulation, and affect normal gastrointestinal functions; these may also destroy the community composition and diversity of intestinal microbes and cause disorders in the intestinal microbial community (Fackelmann and Sommer, 2019; Teles et al., 2020), thereby affecting human health. MPs can also pass through the intestinal barrier and enter the circulatory system, including the liver and spleen (Teles et al., 2020). In addition, MP additives, such as bisphenols and phthalates, are related to endocrine disorders and many health problems, such as diabetes, cancer, and obesity (Okeke et al., 2022). MPs in agricultural soil can be transferred to humans through food, respiration, and contact, causing respiratory tract irritation, asthma, obesity, gastrointestinal diseases, and cardiovascular diseases, which pose a serious threat to human health.

Microplastics in agricultural soil enter the human body through food, respiration and contact, causing respiratory irritation, asthma, obesity, gastrointestinal diseases and cardiovascular diseases, which pose a serious threat to human health.

5 Prevention and Control Strategies

The massive use of plastic products and the improper disposal of plastic wastes have made farmland a major pollution sink for various plastic wastes and MPs. Due to their stability and non-degradability, a large amount of MPs accumulate in agricultural soils, which may pose a risk to the ecosystem. At present, there is still a lack of specific prevention and control strategies for MP pollution in agroecosystems. However, it is generally believed that the development of biodegradable plastic products as alternatives, the “Plastic Restriction Order” to restrict the use of initial MPs and plastic products, the recycling and proper disposal of plastic waste and the removal of plastic waste stocks have positive effects on controlling the source of MPs and on cutting off their way to be transported and accumulated in agricultural soils. The main prevention and control strategies include the implementation of control policies, the development and application of biodegradable plastics, and the regulation of plastic waste recycling and disposal.

5.1 Legislative Measures

Some legal and administrative measures have been taken around the world to control the serious trend of MP pollution. In 2015, the United Nations Environment Programme initiated the progress or phasing out the use of MPs in cosmetics; the European Commission also listed MP pollution as a key area of concern; China issued the “Plastic Restriction Order” and “Opinions on Further Strengthening the Control of Plastic Pollution” in 2008 and 2020 respectively. These policies are mainly aimed to reduce plastic pollution by controlling the source of their production, use process, and recycling process, and to fundamentally control the source of MPs. Nevertheless, the laws and regulations on the prevention and control of agricultural soil MP pollution still need to be improved. At the legal level, it is necessary to advance legislation and amendments to the problem of plastic waste, especially plastic recycling, and strengthen the legal construction of special MP control. At the level of government supervision, the responsibilities of enterprises in the life cycle of plastic products should be clarified. At the public level, the public’s awareness and attention to MP pollution should be strengthened.

5.2 Use of Alternative Products and Biodegradable Plastics

Plastic film mulching has a significant contribution to the accumulation of MPs in agricultural soils (Huang et al., 2020). Therefore, the use of biodegradable (biological) plastic mulch is an important means to solve the problem of plastic film residue and MP pollution. Currently, there are mainly two types of biodegradable plastics. One type is derived from agricultural products, such as corn and other agricultural products, and its representative product is PLA; the other type is biodegradable plastics derived from petrochemical products (RameshKumar et al., 2020). However, due to their high production cost and performance problems, their application and promotion have brought certain challenges. The development of low-cost degradable agricultural films should be carried out, and low-cost degradation-promoting additives should be developed to further improve the controllability and stability of degradable plastic films, thereby effectively shortening the natural degradation time of agricultural films in soil and reducing the ecological and environmental impact of plastic film residues. In addition, after a large-scale use of biodegradable mulch films, the recycling of waste and its impact on agroecosystems need further research.

5.3 Recycling and Disposal of Plastic Wastes

Carrying out garbage classification is a necessary way to realize the recycling and utilization of plastic wastes, which can avoid or reduce the input of plastics into agroecosystems during landfill or stacking. Reasonable and scientific classification, recycling and processing of different types of plastic wastes, which may convert plastic wastes into usable raw materials, effectively solve the environmental pollution caused by improper plastic waste disposal, and realize the reuse of materials and energy of plastic wastes. It is necessary to build a complete industrial chain for the recycling and utilization of plastic wastes, thereby increasing the recycling rate of plastic wastes and effectively promoting the comprehensive utilization of plastic wastes.

6 Challenges and Future Directions

This study summarized the source, occurrence, pollution degree, and environmental fate of soil MPs and their effects on soil physical and chemical properties, enzyme activities, microorganisms, animals, and plants. In addition, the effects of the combined pollution of MPs and other pollutants on soil ecosystems were also discussed, especially the risks of MPs to human health. To better understand the occurrence, distribution, and ecological risks of MPs in farmland ecosystems, some challenges need to be solved.

1) Global and regional data inventories for MP pollution in agroecosystems is rare, and more detailed investigations are needed. Secondly, the lack of a unified evaluation standard for MP pollution led to a lack of comparison of existing research data. In future studies, the qualitative and quantitative evaluation of MPs in agroecosystem of different planting systems under different agricultural practices should be expanded. It is necessary to investigate the MP pollution in different farmland ecosystems and agricultural practices to determine their baseline concentration and quantify their potential impact on soil biodiversity and the exposure risk of soil biota.

2) There are many types of MPs, and MPs of different types, sizes, shapes, and product uses have different effects on soil ecosystems due to their structure and properties. Therefore, various types of MPs of different uses and sources should be included in experiments to study their impact on the ecological environment. In addition, most current studies are focused on the ecotoxicity of a single MP to individual organisms, and it is urgent to study the comprehensive effects of different types of MP mixtures on the soil-microbe-plant system.

3) MPs are hard-to-degrade organic pollutants that stay in soil for a long period. The influence mechanism and process of MPs must be identified on a long-term scale. However, the research time scale of most relevant experiments is relatively short and only reflects the preliminary impact profile. In future, long-term field-scale experiments are needed to evaluate the ecological and environmental effects of MPs, in order to more objectively and truly reflect their comprehensive effects on soil environment under long-term conditions.

4) MPs in agricultural soils often coexist with environmental pollutants such as heavy metals and organics. Coexisting MPs and soil pollutants may have synergistic or antagonistic effects, which will have more complex impacts and uncertain environmental risks on soil, especially on soil ecosystems. Future research should pay more attention to the compound effects of the coexistence of MPs and other pollutants.

5) The cycling of soil nutrients and the maintenance of soil functions are dependent on soil microorganisms. At present, most studies mainly focus on microbial communities and their activities, while there are few studies on specific microbial communities and their functions, especially microbial processes involving biogeochemical cycles of C, N, and P, such as greenhouse gas emissions. Future research needs to clarify the impact of MPs on key microbial species that are critical to major soil functions.

Statements

Author contributions

HY: Conceptualization, Investigation, Data curation, Funding acquisition, Writing—original draft. YZ: Data curation, Formal analysis. WT: Writing—review and editing. ZZ: Data curation, Methodology.

Funding

This work was financially supported by the National Key Research and Development Program of China (No. 2020YFC1909502), the National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 41977030).

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Glossary

- ABS

acrylonitrile-butadiene-styrene copolymer

- Acr

acrylic

- AMF

arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi

- DBP

dibutyl phthalate

- DOC

dissolved organic carbon

- DON

dissolved organic nitrogen

- DOP

dissolved organic phosphorus

- EC

electrical conductivity

- EPC

ethylene-propylene copolymer

- FDAse

fluorescein diacetate hydrolase

- HCHs

hexachlorocyclohexane

- HDPE

high-density polyethylene

- LDPE

low-density polyethylene

- MPs

microplastic(s)

- NPs

nanoplastic(s)

- OPFRs

organophosphorus flame retardant(s)

- PA

polylactic acid

- PAHs

polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbon(s)

- PCBs

polychlorinated biphenyl(s)

- PCF

polymer-coated fertilizer

- PE

polyethylene

- PES

polyester fibers

- PET

polyethylene terephthalate

- PFASs

perfluoroalkyl compound(s)

- Phe

phenanthrene

- PLA

polylactic acid

- PMFs

polyester microfiber(s)

- PMMA

polymethyl methacrylate

- PP

polypropylene

- PPCPs

pharmaceutical and personal care product(s)

- PS

polystyrene

- PTFE

polytetrafluorethylene

- PU

polyurethane

- PVC

polyvinyl chloride

- SOC

soil organic carbon

- SOM

soil organic matter

- SON

soil organic nitrogen

- SOP

soil organic phosphorus

- SWC

soil water content

- TOC

total organic carbon

References

1

AkdoganZ.GuvenB. (2019). Microplastics in the Environment: a Critical Review of Current Understanding and Identification of Future Research Needs. Environ. Pollut.254, 113011. 10.1016/j.envpol.2019.113011

2

Al-JaibachiR.CuthbertR. N.CallaghanA. (2019). Examining Effects of Ontogenic Microplastic Transference on Culex Mosquito Mortality and Adult Weight. Sci. Total Environ.651 (Pt 1), 871–876. 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2018.09.236

3

AlimiO. S.Farner BudarzJ.HernandezL. M.TufenkjiN. (2018). Microplastics and Nanoplastics in Aquatic Environments: Aggregation, Deposition, and Enhanced Contaminant Transport. Environ. Sci. Technol.52 (4), 1704–1724. 10.1021/acs.est.7b05559

4

AwetT. T.KohlY.MeierF.StraskrabaS.GrünA.-L.RufT.et al (2018). Effects of Polystyrene Nanoparticles on the Microbiota and Functional Diversity of Enzymes in Soil. Environ. Sci. Eur.30 (1), 11. 10.1186/s12302-018-0140-6

5

BandickA. K.DickR. P. (1999). Field Management Effects on Soil Enzyme Activities. Soil Biol. Biochem.31 (11), 1471–1479. 10.1016/s0038-0717(99)00051-6

6

BarrickA.ChampeauO.ChatelA.ManierN.NorthcottG.TremblayL. A. (2021). Plastic Additives: Challenges in Ecotox hazard Assessment. PeerJ9, e11300. 10.7717/peerj.11300

7

BeriotN.PeekJ.ZornozaR.GeissenV.Huerta LwangaE. (2021). Low Density-Microplastics Detected in Sheep Faeces and Soil: A Case Study from the Intensive Vegetable Farming in Southeast Spain. Sci. Total Environ.755 (Pt1), 142653. 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2020.142653

8

BianW.AnL.ZhangS.FengJ.SunD.YaoY.et al (2022). The Long-Term Effects of Microplastics on Soil Organomineral Complexes and Bacterial Communities from Controlled-Release Fertilizer Residual Coating. J. Environ. Manage.304, 114193. 10.1016/j.jenvman.2021.114193

9

BlasingM.AmelungW. (2018). Plastics in Soil: Analytical Methods and Possible Sources. Sci. Total Environ.612, 422–435. 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2017.08.086

10

BlöckerL.WatsonC.WichernF. (2020). Living in the Plastic Age - Different Short-Term Microbial Response to Microplastics Addition to Arable Soils with Contrasting Soil Organic Matter Content and Farm Management Legacy. Environ. Pollut.267, 115468. 10.1016/j.envpol.2020.115468

11

BootsB.RussellC. W.GreenD. S. (2019). Effects of Microplastics in Soil Ecosystems: above and below Ground. Environ. Sci. Technol.53 (19), 11496–11506. 10.1021/acs.est.9b03304

12

BoskerT.BouwmanL. J.BrunN. R.BehrensP.VijverM. G. (2019). Microplastics Accumulate on Pores in Seed Capsule and Delay Germination and Root Growth of the Terrestrial Vascular Plant Lepidium Sativum. Chemosphere226, 774–781. 10.1016/j.chemosphere.2019.03.163

13

BriassoulisD.GiannoulisA. (2018). Evaluation of the Functionality of Bio-Based Plastic Mulching Films. Polym. Test.67, 99–109. 10.1016/j.polymertesting.2018.02.019

14

BridsonJ. H.GauglerE. C.SmithD. A.NorthcottG. L.GawS. (2021). Leaching and Extraction of Additives from Plastic Pollution to Inform Environmental Risk: A Multidisciplinary Review of Analytical Approaches. J. Hazard. Mater.414, 125571. 10.1016/j.jhazmat.2021.125571

15

BurnsR. G.DeForestJ. L.MarxsenJ.SinsabaughR. L.StrombergerM. E.WallensteinM. D.et al (2013). Soil Enzymes in a Changing Environment: Current Knowledge and Future Directions. Soil Biol. Biochem.58, 216–234. 10.1016/j.soilbio.2012.11.009

16

CaoL.WuD.LiuP.HuW.XuL.SunY.et al (2021). Occurrence, Distribution and Affecting Factors of Microplastics in Agricultural Soils along the Lower Reaches of Yangtze River, China. Sci. Total Environ.794, 148694. 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2021.148694

17

CarrS. A.LiuJ.TesoroA. G. (2016). Transport and Fate of Microplastic Particles in Wastewater Treatment Plants. Water Res.91, 174–182. 10.1016/j.watres.2016.01.002

18

CarterL. J.ChefetzB.AbdeenZ.BoxallA. B. A. (2019). Emerging Investigator Series: towards a Framework for Establishing the Impacts of Pharmaceuticals in Wastewater Irrigation Systems on Agro-Ecosystems and Human Health. Environ. Sci. Process. Impacts21 (4), 605–622. 10.1039/c9em00020h

19

ChaeY.AnY.-J. (2018). Current Research Trends on Plastic Pollution and Ecological Impacts on the Soil Ecosystem: A Review. Environ. Pollut.240, 387–395. 10.1016/j.envpol.2018.05.008

20

ChenH.WangY.SunX.PengY.XiaoL. (2020c). Mixing Effect of Polylactic Acid Microplastic and Straw Residue on Soil Property and Ecological Function. Chemosphere243, 125271. 10.1016/j.chemosphere.2019.125271

21

ChenW. L.FanT. L.WangS. Y.LiS. Z.ZhangJ. J.GangZ.et al (2020a). Quantity and Distribution of Microplastics in Film Mulching farmland Soil of Northwest China. J. Agro-Environment Sci.39 (11), 2561–2568.

22

ChenY.LengY.LiuX.WangJ. (2020b). Microplastic Pollution in Vegetable Farmlands of Suburb Wuhan, central China. Environ. Pollut.257, 113449. 10.1016/j.envpol.2019.113449

23

ChenY.LiuX.LengY.WangJ. (2020d). Defense Responses in Earthworms (Eisenia fetida) Exposed to Low-Density Polyethylene Microplastics in Soils. Ecotoxicology Environ. Saf.187, 109788. 10.1016/j.ecoenv.2019.109788

24

ChenY.WuY.MaJ.AnY.LiuQ.YangS.et al (2021). Microplastics Pollution in the Soil Mulched by Dust-Proof Nets: A Case Study in Beijing, China. Environ. Pollut.275, 116600. 10.1016/j.envpol.2021.116600

25

ChoiY.KimY. N.YoonJ. H.DickinsonN.KimK. H. (20211962–1973). Plastic Contamination of forest, Urban, and Agricultural Soils: a Case Study of Yeoju City in the Republic of Korea. J. Soil Sediment.21. 10.1007/s11368-020-02759-0

26

CorradiniF.MezaP.EguiluzR.CasadoF.Huerta-LwangaE.GeissenV. (2019). Evidence of Microplastic Accumulation in Agricultural Soils from Sewage Sludge Disposal. Sci. Total Environ.671, 411–420. 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2019.03.368

27

CrossmanJ.HurleyR. R.FutterM.NizzettoL. (2020). Transfer and Transport of Microplastics from Biosolids to Agricultural Soils and the Wider Environment. Sci. Total Environ.724, 138334. 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2020.138334

28

de Souza MachadoA. A.LauC. W.KloasW.BergmannJ.BachelierJ. B.FaltinE.et al (2019). Microplastics Can Change Soil Properties and Affect Plant Performance. Environ. Sci. Technol.53 (10), 6044–6052. 10.1021/acs.est.9b01339

29

de Souza MachadoA. A.LauC. W.TillJ.KloasW.LehmannA.BeckerR.et al (2018). Impacts of Microplastics on the Soil Biophysical Environment. Environ. Sci. Technol.52 (17), 9656–9665. 10.1021/acs.est.8b02212

30

DengY.ZhangY.QiaoR.BonillaM. M.YangX.RenH.et al (2018). Evidence that Microplastics Aggravate the Toxicity of Organophosphorus Flame Retardants in Mice (Mus musculus). J. Hazard. Mater.357, 348–354. 10.1016/j.jhazmat.2018.06.017

31

DingL.ZhangS.WangX.YangX.ZhangC.QiY.et al (2020). The Occurrence and Distribution Characteristics of Microplastics in the Agricultural Soils of Shaanxi Province, in north-western China. Sci. Total Environ.720, 137525. 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2020.137525

32

DingW.LiZ.QiR.JonesD. L.LiuQ.LiuQ.et al (2021). Effect Thresholds for the Earthworm Eisenia fetida: Toxicity Comparison between Conventional and Biodegradable Microplastics. Sci. Total Environ.781, 146884. 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2021.146884

33

DongY.GaoM.QiuW.SongZ. (2021a). Effect of Microplastics and Arsenic on Nutrients and Microorganisms in rice Rhizosphere Soil. Ecotoxicology Environ. Saf.211, 111899. 10.1016/j.ecoenv.2021.111899

34

DongY.GaoM.QiuW.SongZ. (2021b). Uptake of Microplastics by Carrots in Presence of as (III): Combined Toxic Effects. J. Hazard. Mater.411, 125055. 10.1016/j.jhazmat.2021.125055

35

DongY.GaoM.SongZ.QiuW. (2020). Microplastic Particles Increase Arsenic Toxicity to rice Seedlings. Environ. Pollut.259, 113892. 10.1016/j.envpol.2019.113892

36

DongZ.ZhuL.ZhangW.HuangR.LvX.JingX.et al (2019). Role of Surface Functionalities of Nanoplastics on Their Transport in Seawater-Saturated Sea Sand. Environ. Pollut.255 (Pt 1), 113177. 10.1016/j.envpol.2019.113177

37

DrisR.GasperiJ.SaadM.MirandeC.TassinB. (2016). Synthetic Fibers in Atmospheric Fallout: A Source of Microplastics in the Environment?Mar. Pollut. Bull.104 (1-2), 290–293. 10.1016/j.marpolbul.2016.01.006

38

EltemsahY. S.BøhnT. (2019). Acute and Chronic Effects of Polystyrene Microplastics on Juvenile and Adult Daphnia magna. Environ. Pollut.254 (Pt A), 112919. 10.1016/j.envpol.2019.07.087

39

FackelmannG.SommerS. (2019). Microplastics and the Gut Microbiome: How Chronically Exposed Species May Suffer from Gut Dysbiosis. Mar. Pollut. Bull.143, 193–203. 10.1016/j.marpolbul.2019.04.030

40

FeiY.HuangS.ZhangH.TongY.WenD.XiaX.et al (2020). Response of Soil Enzyme Activities and Bacterial Communities to the Accumulation of Microplastics in an Acid Cropped Soil. Sci. Total Environ.707, 135634. 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2019.135634

41

FengS.LuH.LiuY. (2021). The Occurrence of Microplastics in farmland and Grassland Soils in the Qinghai-Tibet Plateau: Different Land Use and Mulching Time in Facility Agriculture. Environ. Pollut.279, 116939. 10.1016/j.envpol.2021.116939

42

FengX.WangQ.SunY.ZhangS.WangF. (2022). Microplastics Change Soil Properties, Heavy Metal Availability and Bacterial Community in a Pb-Zn-Contaminated Soil. J. Hazard. Mater.424, 126374. 10.1016/j.jhazmat.2021.127364

43

GaoB.YaoH.LiY.ZhuY. (2021a). Microplastic Addition Alters the Microbial Community Structure and Stimulates Soil Carbon Dioxide Emissions in Vegetable‐Growing Soil. Environ. Toxicol. Chem.40, 352–365. 10.1002/etc.4916

44

GaoM.LiuY.DongY.SongZ. (2021b). Effect of Polyethylene Particles on Dibutyl Phthalate Toxicity in Lettuce (Lactuca sativa L.). J. Hazard. Mater.401, 123422. 10.1016/j.jhazmat.2020.123422

45

GeJ.LiH.LiuP.ZhangZ.OuyangZ.GuoX. (2021). Review of the Toxic Effect of Microplastics on Terrestrial and Aquatic Plants. Sci. Total Environ.791, 148333. 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2021.148333

46

GeorgeP. B. L.KeithA. M.CreerS.BarrettG. L.LebronI.EmmettB. A.et al (2017). Evaluation of Mesofauna Communities as Soil Quality Indicators in a National-Level Monitoring Programme. Soil Biol. Biochem.115, 537–546. 10.1016/j.soilbio.2017.09.022

47

GiorgettiL.SpanòC.MucciforaS.BottegaS.BarbieriF.BellaniL.et al (2020). Exploring the Interaction between Polystyrene Nanoplastics and Allium cepa during Germination: Internalization in Root Cells, Induction of Toxicity and Oxidative Stress. Plant Physiol. Biochem.149, 170–177. 10.1016/j.plaphy.2020.02.014

48

GongW.ZhangW.JiangM.LiS.LiangG.BuQ.et al (2021). Species-dependent Response of Food Crops to Polystyrene Nanoplastics and Microplastics. Sci. Total Environ.796, 148750. 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2021.148750

49

GuoQ. Q.XiaoM. R.MaY.NiuH.ZhangG. S. (2021). Polyester Microfiber and Natural Organic Matter Impact Microbial Communities, Carbon-Degraded Enzymes, and Carbon Accumulation in a Clayey Soil. J. Hazard. Mater.405, 124701. 10.1016/j.jhazmat.2020.124701

50

HahladakisJ. N.VelisC. A.WeberR.IacovidouE.PurnellP. (2018). An Overview of Chemical Additives Present in Plastics: Migration, Release, Fate and Environmental Impact during Their Use, Disposal and Recycling. J. Hazard. Mater.344, 179–199. 10.1016/j.jhazmat.2017.10.014

51

HanL. H.XuL.LiQ. L.LuA. X.YinJ. W.TianJ. Y. (2021). Levels, Characteristics, and Potential Source of Micro(meso)plastic Pollution of Soil in Liaohe River basin. Environ. Sci.42 (04), 1781–1790.

52

HarmsI. K.DiekötterT.TroegelS.LenzM. (2021). Amount, Distribution and Composition of Large Microplastics in Typical Agricultural Soils in Northern Germany. Sci. Total Environ.758, 143615. 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2020.143615

53

HartmannG. F.RicachenevskyF. K.SilveiraN. M.Pita-BarbosaA. (2022). Phytotoxic Effects of Plastic Pollution in Crops: what Is the Size of the Problem?Environ. Pollut.292, 118420. 10.1016/j.envpol.2021.118420

54

HartmannN. B.RistS.BodinJ.JensenL. H.SchmidtS. N.MayerP.et al (2017). Microplastics as Vectors for Environmental Contaminants: Exploring Sorption, Desorption, and Transfer to Biota. Integr. Environ. Assess. Manag.13 (3), 488–493. 10.1002/ieam.1904

55

HeP.ChenL.ShaoL.ZhangH.LüF. (2019). Municipal Solid Waste (MSW) Landfill: A Source of Microplastics? -Evidence of Microplastics in Landfill Leachate. Water Res.159, 38–45. 10.1016/j.watres.2019.04.060

56

Hernández-ArenasR.Beltrán-SanahujaA.Navarro-QuirantP.Sanz-LazaroC. (2021). The Effect of Sewage Sludge Containing Microplastics on Growth and Fruit Development of Tomato Plants. Environ. Pollut.268 (Pt B), 115779. 10.1016/j.envpol.2020.115779

57

HodsonM. E.Duffus-HodsonC. A.ClarkA.Prendergast-MillerM. T.ThorpeK. L. (2017). Plastic Bag Derived-Microplastics as a Vector for Metal Exposure in Terrestrial Invertebrates. Environ. Sci. Technol.51 (8), 4714–4721. 10.1021/acs.est.7b00635

58

HoelleinT.KellyJ.McCormickA.LondonM. (2016). Consider a Source: Microplastic in Rivers Is Abundant, mobile, and Selects for Unique Bacterial Assemblages. San Francisco: American Geophysical Union, Ocean Sciences Meeting. abstract #HI41A-02.

59

HortonA. A.WaltonA.SpurgeonD. J.LahiveE.SvendsenC. (2017). Microplastics in Freshwater and Terrestrial Environments: Evaluating the Current Understanding to Identify the Knowledge Gaps and Future Research Priorities. Sci. Total Environ.586, 127–141. 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2017.01.190

60

HouJ.XuX.YuH.XiB.TanW. (2021). Comparing the Long-Term Responses of Soil Microbial Structures and Diversities to Polyethylene Microplastics in Different Aggregate Fractions. Environ. Int.149, 106398. 10.1016/j.envint.2021.106398

61

HuangY.LiuQ.JiaW.YanC.WangJ. (2020). Agricultural Plastic Mulching as a Source of Microplastics in the Terrestrial Environment. Environ. Pollut.260, 114096. 10.1016/j.envpol.2020.114096

62

HuangY.ZhaoY.WangJ.ZhangM.JiaW.QinX. (2019). LDPE Microplastic Films Alter Microbial Community Composition and Enzymatic Activities in Soil. Environ. Pollut.254 (Pt A), 112983. 10.1016/j.envpol.2019.112983

63

Huerta LwangaE.GertsenH.GoorenH.PetersP.SalánkiT.van der PloegM.et al (2017). Incorporation of Microplastics from Litter into Burrows of Lumbricus Terrestris. Environ. Pollut.220 (Pt A), 523–531. 10.1016/j.envpol.2016.09.096

64

Huerta LwangaE.GertsenH.GoorenH.PetersP.SalánkiT.van der PloegM.et al (2016). Microplastics in the Terrestrial Ecosystem: Implications for Lumbricus Terrestris (Oligochaeta, Lumbricidae). Environ. Sci. Technol.50 (5), 2685–2691. 10.1021/acs.est.5b05478

65

HüfferT.MetzelderF.SigmundG.SlawekS.SchmidtT. C.HofmannT. (2019). Polyethylene Microplastics Influence the Transport of Organic Contaminants in Soil. Sci. Total Environ.657, 242–247. 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2018.12.047

66

JiangX.ChangY.ZhangT.QiaoY.KlobučarG.LiM. (2020). Toxicological Effects of Polystyrene Microplastics on Earthworm (Eisenia fetida). Environ. Pollut.259, 113896. 10.1016/j.envpol.2019.113896

67

JiangX.ChenH.LiaoY.YeZ.LiM.KlobučarG. (2019). Ecotoxicity and Genotoxicity of Polystyrene Microplastics on Higher Plant Vicia faba. Environ. Pollut.250, 831–838. 10.1016/j.envpol.2019.04.055

68

JudyJ. D.WilliamsM.GreggA.OliverD.KumarA.KookanaR.et al (2019). Microplastics in Municipal Mixed-Waste Organic Outputs Induce Minimal Short to Long-Term Toxicity in Key Terrestrial Biota. Environ. Pollut.252, 522–531. 10.1016/j.envpol.2019.05.027

69

KarbalaeiS.HanachiP.WalkerT. R.ColeM. (2018). Occurrence, Sources, Human Health Impacts and Mitigation of Microplastic Pollution. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res.25 (36), 36046–36063. 10.1007/s11356-018-3508-7

70

KimS.-K.KimJ.-S.LeeH.LeeH.-J. (2021). Abundance and Characteristics of Microplastics in Soils with Different Agricultural Practices: Importance of Sources with Internal Origin and Environmental Fate. J. Hazard. Mater.403, 123997. 10.1016/j.jhazmat.2020.123997

71

KimS. W.WaldmanW. R.KimT.-Y.RilligM. C. (2020). Effects of Different Microplastics on Nematodes in the Soil Environment: Tracking the Extractable Additives Using an Ecotoxicological Approach. Environ. Sci. Technol.54 (21), 13868–13878. 10.1021/acs.est.0c04641

72

KumarM.XiongX.HeM.TsangD. C. W.GuptaJ.KhanE.et al (2020). Microplastics as Pollutants in Agricultural Soils. Environ. Pollut.265 (Pt A), 114980. 10.1016/j.envpol.2020.114980

73

KwakJ. I.AnY.-J. (2021). Microplastic Digestion Generates Fragmented Nanoplastics in Soils and Damages Earthworm Spermatogenesis and Coelomocyte Viability. J. Hazard. Mater.402, 124034. 10.1016/j.jhazmat.2020.124034

74

LambertS.SchererC.WagnerM. (2017). Ecotoxicity Testing of Microplastics: Considering the Heterogeneity of Physicochemical Properties. Integr. Environ. Assess. Manag.13, 470–475. 10.1002/ieam.1901

75

LiB.SongW.ChengY.ZhangK.TianH.DuZ.et al (2021c). Ecotoxicological Effects of Different Size Ranges of Industrial-Grade Polyethylene and Polypropylene Microplastics on Earthworms Eisenia fetida. Sci. Total Environ.783, 147007. 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2021.147007

76