- Earth Innovation Institute, San Francisco, CA, United States

Tropical forests are posited to hold up to one-third of the solution to slow climate change. It is estimated that over two-hundred million “forest peoples”—including indigenous peoples and local communities—live within and depend upon tropical forests. To successfully mitigate climate change, we must find new forms of collaboration that meet the goals of forest-dependent communities for secure land rights, equitable participation in decision-making, and dignified livelihoods in conjunction with meeting commitments to reduce greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions. In 2018, 34 subnational governments and 18 indigenous and local community organizations announced their endorsement of the “Guiding Principles for Collaboration between Subnational Governments, Indigenous Peoples, and Local Communities.” The Guiding Principles of Collaboration (GPC) are a set of 13 universal tenets which lay out a blueprint for collaboration between subnational state actors, indigenous peoples and local communities to recognize rights, support livelihoods, strengthen participation of forest-dependent communities in decision-making, and protect indigenous and community environmental defenders within the context of joint action for climate change mitigation. Their implementation would advance the integration of climate justice in subnational efforts for forest conservation. Taking the GPC as a point of departure, we explore how jurisdictional approaches to sustainability can protect and enhance the rights and livelihoods of indigenous peoples (IP) and local communities (LC). We develop and apply a suite of indicators to assess existing conditions across 11 tropical forest jurisdictions toward meeting the commitments described in the GPC. Our findings suggest that while the rights of indigenous peoples and local communities are recognized within national legal frameworks, implementation and security of those rights is uneven across subnational jurisdictions. Participation of IP and LC is not yet formalized as part of jurisdictional climate change mitigation initiatives in most cases, limiting their potential to inform policy outcomes and benefit-sharing mechanisms. Monitoring the implementation of the GPC may foster greater accountability for commitments, as well as collective action and learning to support regional transformations to sustainability.

Introduction

Tropical forests represent one important front in the fight against climate change. Slowing tropical deforestation and speeding the recovery and conservation of standing forests are crucial to avoid the 1.5°C threshold of warming above pre-industrial levels. Tropical forests are also home to an estimated two-hundred million indigenous peoples and local communities who live within and depend upon the tropical forests in the Amazon, Southeast Asia, Mesoamerica and the Congo Basin (Chao, 2012). Indigenous peoples (IP)1 and local communities (LC)2 are important stewards of forest carbon stocks; a 2018 study estimated that collective lands held and/or managed by IP and LC account for 17% of total carbon stored in forestlands across 64 countries encompassing 69% of the world's forests (Frechette et al., 2018). In the Amazon basin, over one-third (34%, 24,641 MtC) of the region's above-ground carbon is stored in indigenous territories (IT) (Walker et al., 2020).

Forest-dependent communities living within these tropical forests contribute to forest conservation through low intensity land uses, active protection of their boundaries, and as a result of legal restrictions imposed by governments, ostensibly protecting indigenous lands from natural resource exploitation by outsiders (Nepstad et al., 2006; Ricketts et al., 2010; Soares-Filho et al., 2012; Fa et al., 2020). IP and LC also suffer disproportionately from the impacts of deforestation and climate change. Across many tropical forest regions, deforestation drivers operate in conjunction with other threats to indigenous and traditional lands, with impacts not just on ecosystems, but also on health, well-being, livelihoods and tenure security (Olsson et al., 2014; Sunderlin et al., 2014). These findings have strengthened arguments for the inclusion of IP and LC in broader policy processes related to climate change and land use, based on arguments that their participation will enhance climate change mitigation as well as on the basis of human rights and climate justice (Garnett et al., 2018; Robinson and Shine, 2018). A number of recent international commitments and agreements, including the 2014 Rio Branco Declaration, the 2014 New York Declaration on Forests, and the 2015 Paris Agreement, reflect growing recognition regarding the importance of IP and LC rights and participation as part of effective climate solutions. Most recently, an international coalition of subnational governments, the Governors' Climate and Forest (GCF) Task Force3, and representative IP and LC organizations endorsed the Guiding Principles for Collaboration between Subnational Governments, Indigenous Peoples, and Local Communities (referred to here as the “Principles” or “GPC”), making an ambitious call for collaboration in efforts to mitigate climate change.

The increasing visibility and recognition of the role of IP and LC in forest conservation has opened important opportunities to protect and enhance IP and LC rights and livelihoods through jurisdictional approaches to sustainability that seek broader transformations in environmental governance. Recent studies have found, however, that the engagement of IP and LC in jurisdictional sustainability remains uneven and insufficient (DiGiano et al., 2016; Stickler et al., 2018b). Barriers to deeper engagement of IP and LC include the fact that subnational governments may view IP and LC as outside their purview and authority, the sheer diversity of IP and LC and threats to their rights and livelihoods, and insufficient models of incentives that achieve both environmental and social benefits (DiGiano et al., 2016). Further, to date, we do yet have a systematic way to capture the current status of jurisdictional sustainability with regards to the protection and enhancement of IP and LC rights and livelihoods, or measure progress toward meeting the goals laid out in the Principles.

In this paper, we build upon recent research on jurisdictional sustainability to examine how these approaches may protect and enhance IP and LC rights and livelihoods. We first look to the GPC to identify key issues to be considered for the protection and enhancement of IP and LC rights and livelihoods. We then develop and apply a suite of indicators to assess existing conditions across 11 tropical forest jurisdictions. We discuss the findings and implications for the protection and enhancement of IP and LC rights and livelihoods within jurisdictional sustainability, highlighting three critical gaps between existing conditions and aspirations described in the GPC. Finally, we reflect upon our pilot methodology in the context of broader efforts to track progress toward jurisdictional sustainability and propose future directions for monitoring the translation of commitments, such as the GPC, into practice.

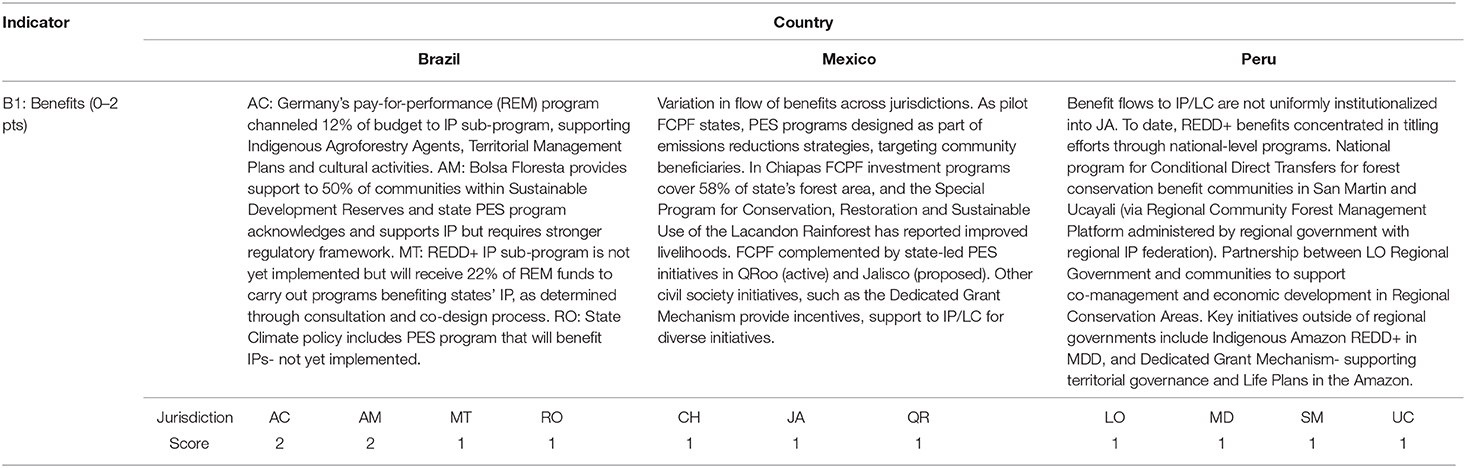

The GPC4 were borne out of a number of international commitments and agreements, including the 2014 Rio Branco Declaration5, the 2014 New York Declaration on Forests6, and the 2015 Paris Agreement7, which highlighted the importance of IP and LC as part of effective climate solutions. Specifically, the GPC seek to operationalize the 2014 Rio Branco Declaration, which committed subnational governments to partner with IP and traditional communities on initiatives to reduce emissions from deforestation and forest degradation at the subnational level. Following the signing of the Rio Branco Declaration in 2014, members of the GCF Task Force, indigenous and local community leaders began collaborating to identify pathways toward the implementation of the Rio Branco Declaration. This coalition-building led to the establishment of a working group within the GCF Task Force, including governmental, IP, LC, and civil society representatives, to provide recommendations to the broader GCF Task Force membership to realize their commitment to partner with IP and LC as part of jurisdictional approaches to sustainability. The working group convened in 2017 and began co-designing a set of universal principles to guide the actions of GCF Task Force members. The initial drafting process was followed by on-going discussions and negotiations between subnational government representatives, indigenous and community leaders, along with civil society partners so that the Principles aligned with the roles and authorities of GCF Task Force members and included key demands of indigenous and community leaders. For example, Brazilian GCF Task Force member states sought to ensure that language regarding rights recognition reflected their subordinate role to federal authorities on IP and LC issues, and IP and LC leaders successfully advocated for the inclusion of a principle to protect environmental defenders (Scanlan-Lyons et al., 2018). Throughout 2018, the GPC were socialized and vetted among GCF Task Force members, IP and LC organizations and civil society groups, with the goal of securing the formal endorsement of the Principles by GCF Task Force members and IP and LC organizations.

The final set of 13 GPC (Table 1) lay out a blueprint for collaboration between subnational state actors, IP and LC to recognize rights, support livelihoods, strengthen participation of forest-dependent communities in decision-making, and protect indigenous and community environmental defenders within the context of joint action for climate change mitigation. The GPC seek to provide a model of how governments can more effectively engage IP and LC in the design and implementation of policies and programs that impact their communities. More broadly, their implementation would advance a deeper engagement of climate justice in subnational efforts for forest conservation.

Table 1. The Guiding Principles, organized by the four thematic categories used in our analysis of baseline conditions.

The Principles were endorsed by GCF Task Force member states during their annual meeting in 2018, and then announced at the 2018 Global Climate Action Summit in San Francisco, California. Endorsers included 34 GCF Task Force member states and provinces and 18 indigenous and local community organizations, including some of the global south's largest representative organizations such as Indonesia's Indigenous Alliance of the Archipelago (AMAN), the Mesoamerican Alliance of Peoples and Forests (AMPB), and the Coordinator of Indigenous Organizations of the Amazon Basin (COICA), which represent hundreds of thousands of members.

While the GPC do not represent a legally binding agreement, their endorsement signals a deeper institutionalization of commitments to protect and enhance IP and LC rights and livelihoods as part of jurisdictional sustainability. However, to date, there is no systematic analysis of how far tropical forest jurisdictions are from fully integrating the Principles into jurisdictional approaches to sustainability. Nor do we have a means for tracking progress toward meeting these commitments. By developing and piloting a methodology to capture the status of progress to date toward adoption of the GPC within select tropical forest jurisdictions, we seek to contribute to greater understanding of how jurisdictional sustainability can protect and enhance the rights and livelihoods of IP and LC, and identify barriers and opportunities to advance commitments going forward.

Methods

Data Sources

We used two separate datasets to develop and test a set of indicators to assess baseline conditions of 11 select tropical forest jurisdictions in implementing the GPC. The first dataset was derived from an analysis of barriers and opportunities for IP and LC in the context of subnational jurisdictional approaches to REDD+ (Reducing Emissions from Deforestation and forest Degradation) (DiGiano et al., 2016). The second data set was part of a large-scale study conducted by Earth Innovation Institute (EII) and the Center for International Forestry Research (CIFOR) on the State of Jurisdictional Sustainability (Stickler et al., 2018a,b). In the DiGiano et al. (2016) study, data were collected regarding IP and LC rights recognition within legal frameworks, tenure regimes, Free Prior and Informed Consent, IP and LC participation in policy dialogues, and threats to IP and LC territorial rights for six tropical forest regions in Latin America and Asia. Data were collected by regional experts through the review of policy and legal documents, white papers and relevant literature, using a structured survey to compile data across regions. Stickler et al. (2018b) conducted a comprehensive assessment of jurisdictional sustainability across 39 jurisdictions using secondary data and interviews with key stakeholders. Data were collected for GCF Task Force jurisdictions using the Sustainable Landscapes Rating Tool (SLRT, 2019). The tool was adapted by EII and CIFOR and then applied in jurisdictions by CIFOR and EII teams. We complemented these two datasets with additional secondary data, including white papers, publicly available databases, and peer-reviewed publications, to triangulate findings, fill gaps, and update data from the previous studies where possible (see Supplementary Material for sources by indicator).

GPC Indicator Typology

Because the GPC were developed and vetted by both subnational governments and IP and LC organizations, they serve to identify issues deemed important in defining jurisdictional sustainability by these groups. We began our assessment by classifying the Principles into broad categories representing key aspects found in our previous studies to be relevant to IP and LC in the context of jurisdictional sustainability (DiGiano et al., 2016, 2018; Stickler et al., 2018b) and based on our review of current literature. We identified four categories: (1) IP and LC rights recognition (Rights Recognition), (2) the implementation and security of IP and LC rights (Rights Security), (3) participation of IP and LC (Participation), and (4) benefit-sharing with IP and LC (Benefits). Within each category, we then developed indicators to measure baseline conditions, referencing or adapting indicators used in our two datasets. Below we provide further details with regard to how we determined these four thematic areas, their relevance to jurisdictional sustainability, and the indicators developed for each thematic category.

Rights Recognition

We identified GPC 1, 2, 3, 5, and 9 as addressing issues of rights recognition. Rights recognition and respect for international legal instruments and commitments that recognize IP and LC rights, such as International Labor Organization Convention (ILO) 169 on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples8 and the United Nations Declaration of the Rights of Indigenous Peoples9 (2007) figure prominently in the Principles. Climate change mitigation became more broadly considered a human rights issue in the early 2000s, with the UNFCCC expanding references to IP in its decision-text in 2005, followed by the Cancun negotiations which established safeguards for REDD+10 (2010), inclusion of IP rights in the preface of the Paris Agreement11 (2015), and the establishment of the IP and LC Platform as part of the UNFCCC (2017) (Lyster, 2011; Ford et al., 2016). In countries like Indonesia, Panama and Peru, debates surrounding REDD+ opened critical spaces to address rights recognition and tenure security, which in turn resulted in specific actions and initiatives to secure IP and LC rights within national REDD+ programs (White, 2013; Astuti and McGregor, 2015; Holmes et al., 2017; Fay and Denduangrudee, 2018; Lozano, 2018). While authority to recognize IP and LC rights generally resides with national-level governments (Busch and Amarjargal, 2020), there is a role for subnational governments in implementing those rights (Libert-Amico and Larson, 2020).

The three indicators for Rights Recognition are:

• Formal rights recognition (R1): We assessed the extent to which IP and LC rights are recognized by national and subnational governments. We coded this indicator as 0 if IP and LC rights were not recognized by national governments, 1 if IP and LC rights were recognized by national governments and international agreements, such as endorsement of ILO 169, and 2 if IP and LC rights were recognized by national governments, international agreements and in addition referenced in national or subnational level climate change laws.

• Types of land and resource rights (R2): We assessed the bundles of formal rights designated on IP and LC lands. A full bundle of rights includes access, withdrawal, use, management and alienation (Schlager and Ostrom, 1992). We coded this indicator as 0 if no formal rights were designated, 1 if a partial bundle of rights was designated (some but not all of rights listed above), and 2 if a full bundle of rights was designated.

• Legal framework for consultation (R3): We assessed the status of Free Prior and Informed Consent (FPIC) in legal frameworks at national and subnational levels. We coded this indicator as 0 if there was no legal framework for FPIC at the national or subnational level, 1 if FPIC was required for activities affecting IP or LC, but not both, and 2 if FPIC requirement applied to both IP and LC. We also added an additional point if subnational legal frameworks mandated consultation of IP and LC.

Rights Security

We categorized GPC 5, 9, and 13 as referring to issues of rights security. De jure rights recognition is distinct from implementation of those rights and their security in practice (Rights Resources Initiative, 2015). Therefore, rights security is thought of most broadly as the confidence that rights will be upheld by society at large (see Chhatre et al., 2012; Naughton-Treves and Wendland, 2014 on tenure security). GPC 5 commits to integrating IP and LC rights into jurisdictional strategies, GPC 9 establishes a commitment to “respect and ensure consistency” with international agreements, such as ILO 169, that guarantee the rights of IP and LC to consultation, and GPC 13 commits in broad terms to ensuring the protection of IP and LC environmental defenders. In regions with weak governance or state presence, formal rights recognition may be insufficient to protect those rights. Rights may be undermined by lack of enforcement, corruption, conflicting policies, or structural violence. Tenure insecurity persists due to insufficient titling (e.g., poor implementation of formal rights recognition), overlapping claims, contested ownership, direct threats from other land users, and ambiguities in legal frameworks themselves (Larson et al., 2013; Sunderlin et al., 2014). Human security is defined as the capacity of people and communities to adequately manage stresses to their needs, rights and values, and to live free from violence or threat (Adger et al., 2014); human insecurity is often linked with rights insecurity (Duchelle et al., 2014). Ending the criminalization of and violence against IP and LC leaders is one of five key demands from the Guardians of the Forest, a global Alliance of IP and LC12 and is reiterated in their 2018 statement in response to the IPCC Special Report on Climate Change and Land13. Addressing rights insecurity, including violence against IP and LC environmental defenders, will require political and institutional reforms at multiple scales, and includes a role for subnational governments to clarify rights, address conflicting policies and direct threats in the context of jurisdictional sustainability.

The six indicators we developed to assess Rights Security are as follows:

• Land titling/customary rights designation (S1): We assessed the status of the titling of IP and LC lands as a metric to evaluate implementation of formally recognized rights. We coded this indicator to 0 if no land rights had been designated, 1 if land rights had been partially designated, and 2 if land titling processes had been completed.

• Clarity of IP and LC land rights (S2): We assessed if IP and LC land rights are integrated into official maps, the extent to which maps address overlapping land rights, and if processes exist to clarify overlapping rights. We coded this indicator to 0 if there were no official maps, 1 if official maps existed but they did not address overlapping land rights, 2 if official maps demonstrated overlapping land rights but overlapping rights were not addressed in practice, and 3 if maps demonstrated overlapping rights and processes existed to clarify overlapping rights.

• Grievance Mechanisms (S3): This indicator assessed the extent to which mechanisms for conflict resolution related to IP and LC rights existed at subnational or national level (e.g., ombudsman). We scored this indicator as 0 if there was no evidence of mechanisms to address conflict or express grievances, 1 if mechanisms existed but lacked evidence of conflicts registered and resolved, and 2 if public reports of conflicts registered and resolved over the last 5 years demonstrated the functioning of conflict resolution and grievance mechanisms.

• Subnational Consultation of IP and LC (S4): We assessed if subnational jurisdictions were implementing consultations with IP and LC regarding sustainable development, climate change mitigation and low-emissions development strategies. We coded this indicator to 0 if there was no evidence of state-led consultation processes, 1 if IP and LC were included in some dialogues regarding relevant programs and policies, but not as part of formally defined consultation processes, and 2 if a state-wide consultation process of IP and LC had been implemented or designed.

• Legal threats to IP and LC rights (S5): We examined the extent to which IP and LC formally recognized rights were subject to direct or indirect threats by legal measures that undermine those rights (e.g., measures that allow involuntary resettlement). We coded this indicator to 0 if IP and LC rights were subject to significant threats from legal instruments- either proposed or enacted; 1 if IP and LC rights were subject to minimal threats from legal measures.

• Violence against IP and LC environmental defenders (S6): We assess to what extent IP and LC were subject to violence and death in defense of land and resource rights during the 5 year period between 2013 and 2018. We coded this indicator to presence (0) or absence (1) of reported deaths of IP and LC environmental defenders.

Participation

A third key theme salient in the Principles centers on the effective participation of IP and LC in decision-making related to jurisdictional sustainability. This theme is addressed by GPC 6, 7, 8, 11, and 12. The GPC establish commitments to enhance the participation of IP and LC in decision-making regarding jurisdictional sustainability (GPC 7 and 8), to facilitate IP and LC participation in the design of benefits and incentives (GPC 11 and 12), and to help foster partnerships between IP and LC and subnational governments (GPC 6). Over the last decade, REDD+ has brought increased attention to the role of local stakeholders, or lack thereof, in decision-making around REDD+ strategies at local, national and global scales. Stakeholder participation is posited to enhance equitable and effective outcomes of initiatives to reduce deforestation (Murdiyarso et al., 2012; Marion Suiseeya and Caplow, 2013) as well as the legitimacy of decision-making processes and institutions (Brown and Corbera, 2003). Despite these claims, many studies assert that participation of local stakeholders is still not adequate (Lawlor et al., 2013; Duchelle et al., 2018), and IP and LC participation in decision-making processes around REDD+, low-emissions development strategies and nature-based climate solutions remains low (McDermott et al., 2012; Brondizio and Le Tourneau, 2016; DiGiano et al., 2016; Pasgaard et al., 2016). By asserting the importance of IP and LC participation in the design and implementation of jurisdictional sustainability, the GPC establish a basis for broadening spaces for participation at the subnational level.

We developed two indicators to assess participation of IP and LC:

• Participation Spaces (P1): We assessed the extent to which spaces existed within subnational jurisdictions that facilitate IP and LC participation in dialogues and decision-making related to jurisdictional sustainability. We coded this indicator to 0 if no spaces existed to facilitate IP and LC participation. We coded this indicator to 1 if spaces exist around certain projects or initiatives but were time-bound; 2 if multi-stakeholder forums related to jurisdictional sustainability included IP and LC representation; and 3 if a specific space existed to address IP and LC issues within the context of jurisdictional sustainability.

• Level of IP and LC Participation (P2): We assessed the level of IP and LC participation in the aforementioned spaces. We coded this indicator to 0 if there was evidence of little to no participation of IP and LC, to 1 if there was evidence of intermittent participation, and to 2 if there was evidence of continued participation via specified forums or institutional arrangements.

Benefit-Sharing

GPC 4 and 10 relate to the question of benefit-sharing, which reaffirm the commitments made by subnational governments in 2014 to share a significant portion of benefits from climate change finance with IP and LC (Rio Branco Declaration, 2014). Specifically, GPC 4 references the intention to support territorial governance, implementation of Life Plans and support for traditional livelihoods. Relative to their total numbers and to the large portion of forest carbon stocks they protect, and despite the advances of REDD+ as a potential compensation vehicle, IP and LC have received very few concrete benefits to date from climate change mitigation. Soanes et al. (2017) estimates that between 2003 and 2015, <10% (USD 1.5 billion) of international, national and regional climate finance reached local communities, and of that 10%, an even smaller fraction has gone to IP. Benefits can be more broadly defined than just financial- they may include programs and incentives to address needs identified by stakeholders themselves, such as the need for titling, support for cultural activities or food security (DiGiano et al., 2016). The importance of IP and LC participation in the design of benefit-sharing and financial mechanisms, in ways that align with IP and LC culture, vision and demands, as described in GPC 4 and reflected in the principles related to Participation, underscores the importance of legitimacy and procedural equities in decision-making processes regarding jurisdictional sustainability, as highlighted in existing REDD+ initiatives (Luttrell et al., 2013).

We developed one indicator to assess benefits to IP and LC:

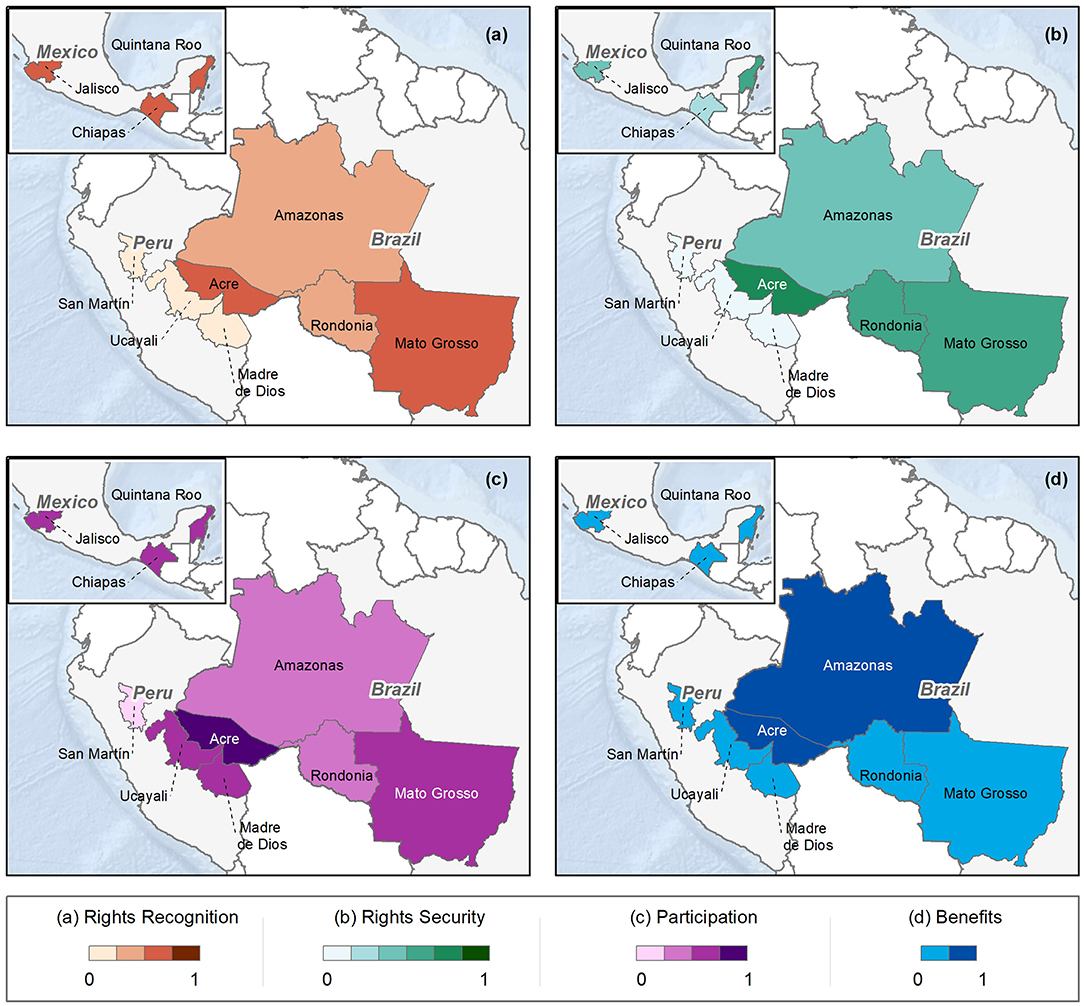

• Benefits (B1): We assessed to what extent benefits and incentives to protect and enhance the rights and livelihoods of IP and LC are included in jurisdictional sustainability approaches, including support for titling, territorial governance, life plans and forest management. We coded this indicator to 0 if there were no benefits channeled to IP and LC via jurisdictional sustainability programs. We coded to 1 if the study jurisdiction demonstrated “intermediate” benefits to IP and LC, where intermediate was defined as limited in number or scope. We coded this indicator to 2 where we considered benefits to be “advanced,” referring to the number or extent of benefits targeting IP and LC as part of jurisdictional programs. While we noted the presence of benefits channeled to subnational jurisdictions via national programs, we coded according to benefits administered by subnational governments.

Applying Indicators to Selected Jurisdictions

Site Selection

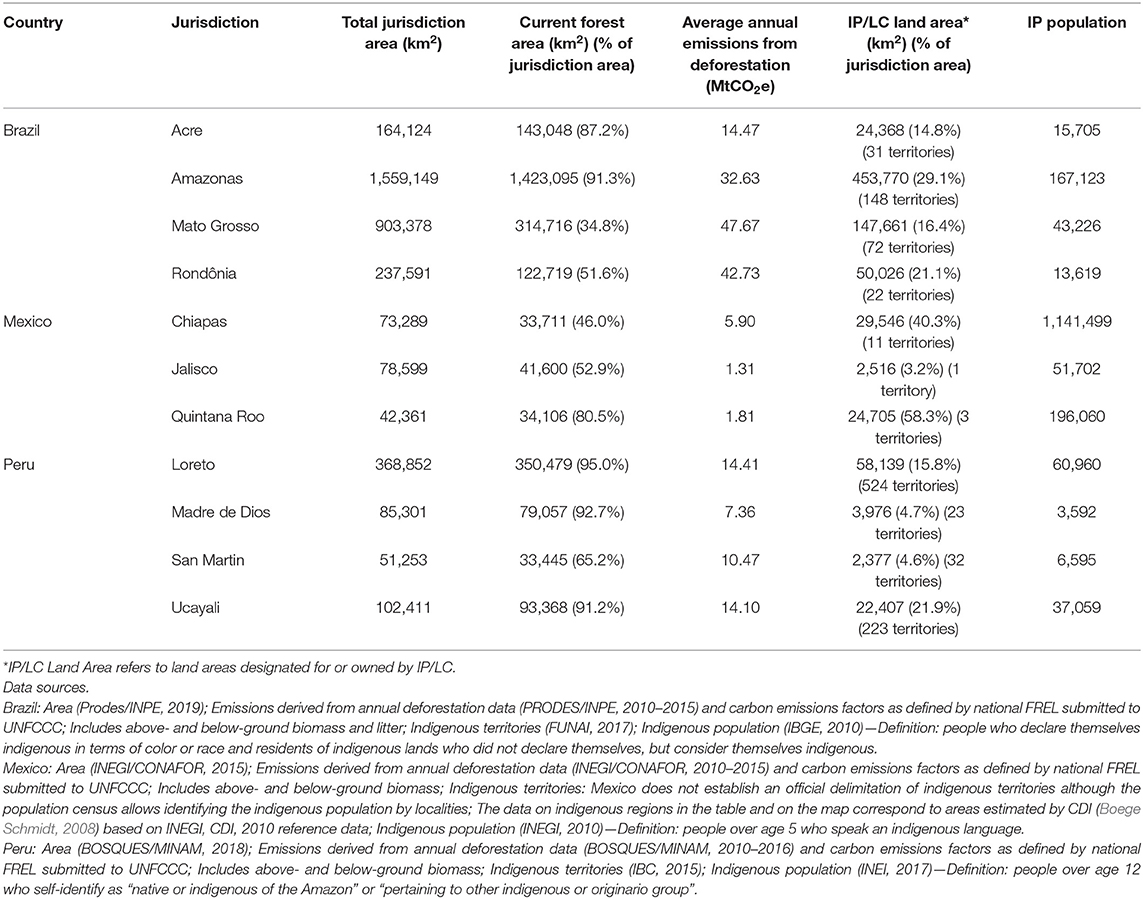

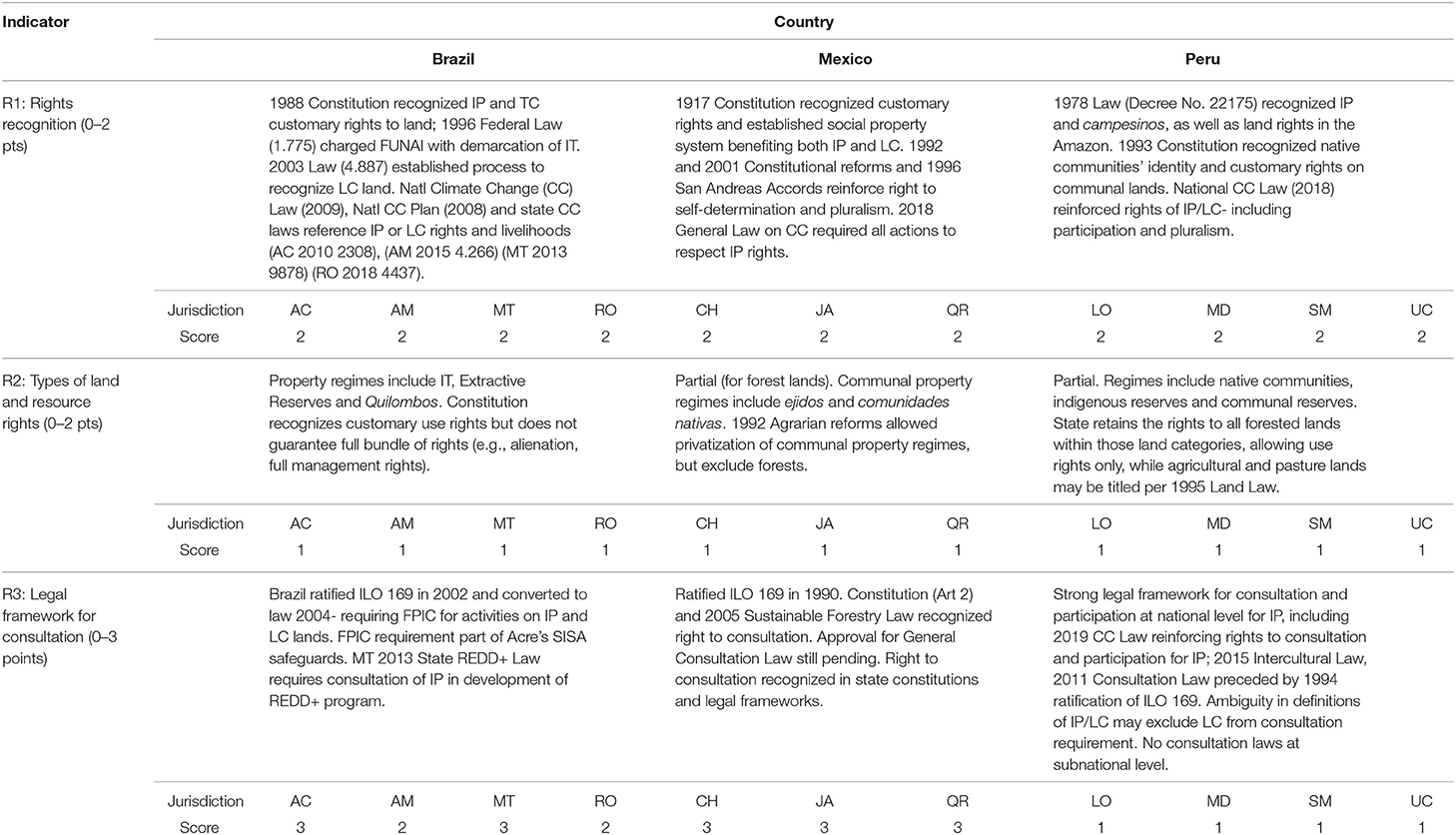

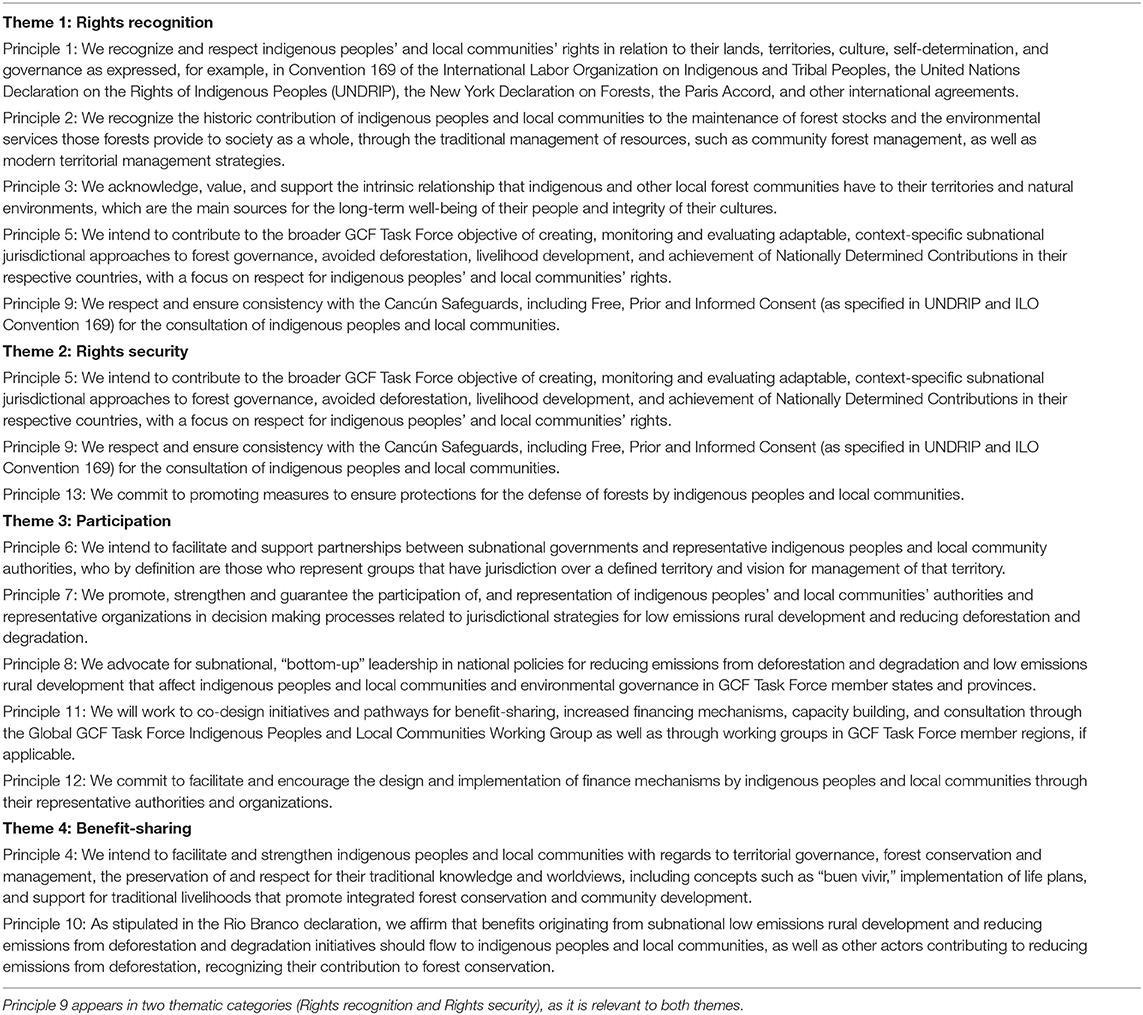

We applied the suite of indicators to 11 subnational tropical forest jurisdictions. The selected jurisdictions included four states from the Brazilian Amazon, four regional governments from the Peruvian Amazon and three Mexican states (Figure 1), all of which are members of the GCF Task Force and endorsers of the GPC. We included jurisdictions that were part of the DiGiano et al. (2016) study- Acre, Mato Grosso, Rondônia, Loreto, Madre de Dios, and Chiapas- for which we also had data from Stickler et al. (2018b). We then included 1 additional jurisdiction from Peru (Ucayali), and 2 additional jurisdictions from Mexico (Quintana Roo and Jalisco) to examine diversity across subnational jurisdictions within the same national context. These three additional jurisdictions were also included in Stickler et al. (2018a,b). The study jurisdictions demonstrate a range of characteristics related to rights designation and forest cover (see Table 2), as well as diverse experiences with jurisdictional approaches to sustainability (Stickler et al., 2018a,b). Mexican state governments and Peruvian regional governments have advanced subnational approaches under national REDD+ and pay-for-performance finance initiatives, while Brazilian states have advanced jurisdictional approaches in parallel or independent of national climate change mitigation initiatives (Stickler et al., 2020). The study jurisdictions do not reflect the full range of contexts within which jurisdictional approaches are being implemented (for comprehensive assessment of jurisdictional sustainability across 39 subnational jurisdictions, see Stickler et al., 2018b). That said, the study jurisdictions demonstrate diverse commitments under the broad framework of jurisdictional approaches, sufficient variation in terms of advancement of jurisdictional sustainability (Stickler et al., 2018b), and sufficient data to pilot the indicators and consider their potential for broader application.

Figure 1. Map showing the 11 tropical forest jurisdictions assessed for baseline conditions in implementation of the GPC.

Scoring

For each study jurisdiction we calculated a baseline score for each of the indicators by totaling the number of points coded to each indicator within each of the four categories. The scores were then scaled for each of the four categories, based on the total number of indicators per category and total number of possible points, to establish a baseline category score (0–1).

Results

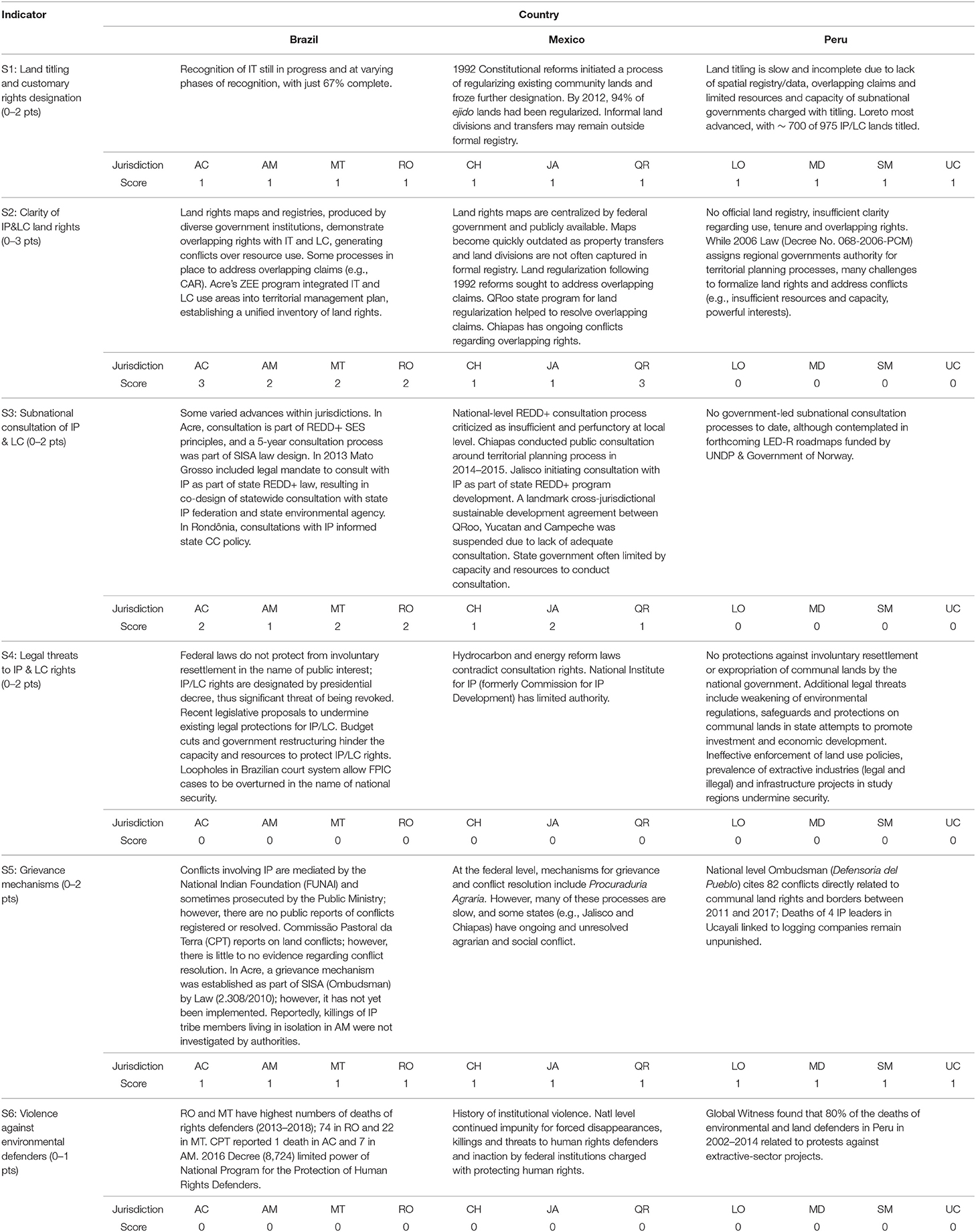

Rights Recognition

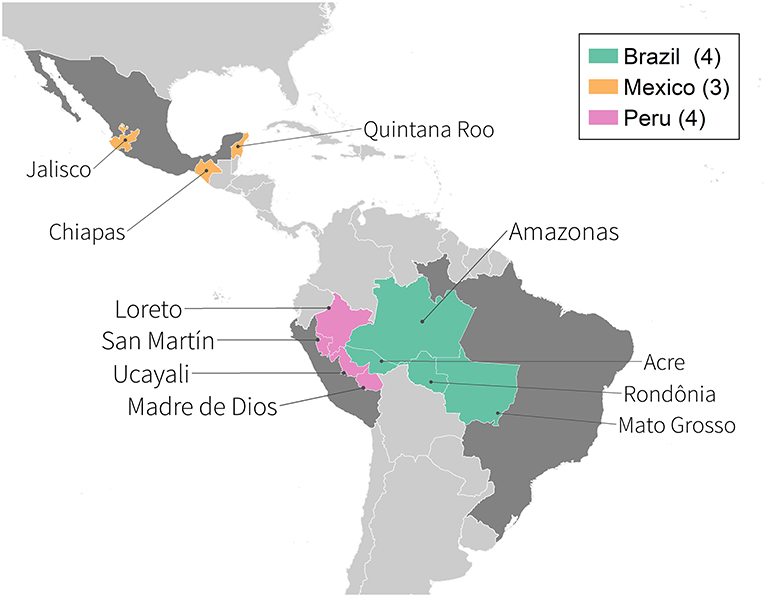

We found that all case study jurisdictions have legal frameworks in place that recognize IP and LC rights at the national level (R1) (Table 3; Figure 2A). All countries recognize the rights of IP in their Constitutions, and have additional legislation pertaining to the designation of land rights for IP and LC. National climate change laws in Peru (2018)14 and Mexico (2012)15 also explicitly reference IP and LC rights. While Brazil's National Climate Change Law16 and Plan17 do not reference IP and LC, state climate change laws for Acre, Amazonas, Mato Grosso, and Rondônia do. Across all three countries, IP and LC are considered to have partial rights (R2), which include use and access rights, with the central government maintaining alienation rights18. With respect to legal frameworks for consultation (R3), all three countries ratified ILO 169, recognizing the right to FPIC for IP, and all include national legislation requiring FPIC. Several subnational jurisdictions include specific legislation regarding consultation of IP and LC, including Mato Grosso's 2013 State REDD+ Law19, Jalisco's 2006 Law on the Rights of IP20, and Chiapas' 1999 Law on the Rights and Culture of IP21. Since legislation pertaining to IP and LC rights falls under the domain of federal authorities in these countries, consistency across jurisdictions within the same country is not surprising.

Figure 2. Map indicating the baseline assessment of 11 tropical forest jurisdictions in implementation of the Principles. Panels correspond to summary score per category (scaled from 0–1) for each of the four thematic categories across the 11 study jurisdictions.

Rights Security

Across the board, jurisdictions demonstrated lower scores on the indicators of rights security (S1–S6) (Table 4; Figure 2B). We found that land titling remains partially complete in all study jurisdictions (S1)—often due to complex procedures for land registration, insufficient resources and capacity of governments to carry out titling and to resolve conflicts related to overlapping claims, and in some cases, definitional ambiguities regarding who qualifies as a rights holder (Le Tourneau, 2015; Blackman et al., 2017).

We found varying degrees of clarity over land rights (S2) across study jurisdictions. Our findings indicate that for the most part, subnational jurisdictions lack publicly available integrated maps to demonstrate IP and LC rights and address overlapping rights claims, with the exception of Acre, Rondônia and Quintana Roo, which have undergone territorial planning processes in an attempt to integrate land use and land rights maps. In Brazil, spatial information regarding indigenous territories and traditional community lands are provided by national agencies (e.g., National Indian Foundation- FUNAI and Brazilian Institute of Environment and Renewable Natural Resources- IBAMA), the Rural Environmental Registry (CAR) and state registries, sometimes with conflicting information. Acre and Rondônia are the most advanced in establishing jurisdictional spatial plans integrating information sources into one planning instrument through their Environmental and Economic Zoning (ZEE) processes (Bezerra and David, 2018; de los Rios et al., 2018). Indigenous territories were included as part of Acre's ZEE processes despite lacking complete formal recognition at the federal level, putting these lands “on the map” quite literally (DiGiano et al., 2018). However, we also found that zoning processes may exacerbate conflicts by designating areas for conservation that may be considered ancestral, yet unrecognized, territories by some groups, as in the case of San Martin, Peru.

Overall, Peruvian jurisdictions scored the lowest on clarity over land rights due to the absence of official maps or rights registry for the country. There, civil society groups, such as the Instituto del Bien Común, provide extensive information about land rights in the country, although they are not considered official by government agencies. Further, overlapping claims between hydrocarbon concessions and IP and LC lands (recognized and unrecognized) exacerbate conflicts and further stall processes to clarify rights. In 2010, researchers estimated that one-half of active oil and gas concessions overlapped with native communities in the Peruvian Amazon (Finer and Orta-Martínez, 2010). In Madre de Dios, the regional government estimated in 2013 that more than 2 million ha may be subject to overlapping claims (Monterroso et al., 2017). In Jalisco and Chiapas, our findings indicate the presence of unresolved overlapping claims and border disputes involving ejidos.

Although all countries are signatories of ILO 169 and have national legislation regarding consultation of IP and LC, implementation of consultation processes related to jurisdiction-wide climate change mitigation programs varied across countries and jurisdictions (S3). Four of the 11 jurisdictions demonstrated advances in statewide consultations of IP and LC as part of jurisdictional strategies. Acre carried out a multi-year public consultation of its State System of Environmental Incentives (SISA), involving IP and other potential beneficiaries. This process resulted in two important outcomes: a tailored set of REDD+ Social and Environmental Safeguards to guide program implementation as well as the original Principles of Collaboration to guide how the SISA program would engage with the states' indigenous peoples. More recently, Mato Grosso initiated a state-wide consultation of indigenous peoples to inform the indigenous peoples sub-program of its state REDD+ program. It is important to note that both Acre's SISA law (2010) and Mato Grosso's state climate change law (2013) mandate the consultation of IP as part of state programs for climate change. Rondônia also undertook a statewide consultation of IP as part of a public, multi-stakeholder dialogue regarding its climate change law; however, it was criticized for limited engagement of IP groups. While Mexico has one of the most advanced national level consultation processes for its REDD+ program via the Forest Carbon Partnership Facility (FCPF), Jalisco is the first subnational jurisdiction to design a statewide consultation processes involving IP and LC as part of the development of its state REDD+ strategy. Peruvian regional governments have not led consultation processes with IP and LC in the design of LED-R strategies currently supported with joint UNDP-Norway funding (UNDP, n.d.; see also Stickler et al., 2020), although consultations with IP and LC are to be included in upcoming phasing of strategy designs, according to reports from regional experts.

Our findings indicate that IP and LC rights security is undermined by legal actions that seek to curtail or rollback previously recognized rights (S4), insufficient or ineffective conflict resolution mechanisms (S5), as well as continued violence against IP and LC environmental defenders (S6). These results suggest that significant threats to IP and LC rights from conflicting laws and policies, insufficient enforcement of rights protections and/or institutional violence are present across study jurisdictions, which we assessed as “0.” In Brazil, a number of reforms to undermine constitutional rights of IP and LC have been proposed in recent years, and President Jair Bolsonaro's administration has further limited FUNAI's capacity to administer indigenous affairs through institutional restructuring and budget cuts. In Peru, federal laws have cut environmental safeguards affecting IP and LC and facilitated acquisition of IP and LC lands by private investors (Rights Resources Initiative, 2015; Lozano, 2018). In Mexico, a pervasive institutional norm of corruption, impunity for human rights offenses and violence undermines rights protections (Global Americans, 2017). In the Yucatan peninsula, two initiatives have brought the issue of consultation to the fore. The first is the previously lauded conservation agreement between the states of Quintana Roo, Yucatan and Campeche, which faces legal action by IP and LC for lack of consultation (Carrera Palí, 2018). The second is the controversial Tren Maya, which has brought to light tensions surrounding economic development and FPIC (Martin, 2019).

We found little evidence of conflicts resolved by means of grievance mechanisms or agencies charged with conflict resolution (S5), many of which are centralized at the national level, such as Mexico's Procuraduria Agraria, Peru's Defensoria del Pueblo, Brazil's FUNAI and Ministerio Publico. Acre created a state-level ombudsman as part of its State System for Environmental Incentives; however, we did not find evidence of implementation.

While data were difficult to find at the subnational level regarding violence against environmental defenders, we found that at the national level, violence against IP and LC leaders continues to go unpunished (S6). Global Witness (2018) reports continued violence against land and environmental defenders showing 542 deaths in Brazil, Mexico and Peru alone between 2008 and 201822. In Brazil, the only country for which we were able to obtain subnational level data, we found greater number of reported violence against rights defenders (including IP, LC members, organizational leaders) in Rondônia and Mato Grosso- with 74 deaths and 22 deaths, respectively, between 2013 and 2018 (CPT, 2017; Comissão Pastoral da Terra, 2020). In Peru, the unpunished death of four indigenous leaders in Ucayali in 2014 by illegal loggers is indicative of a climate of impunity (Amancio and Castro, 2020).

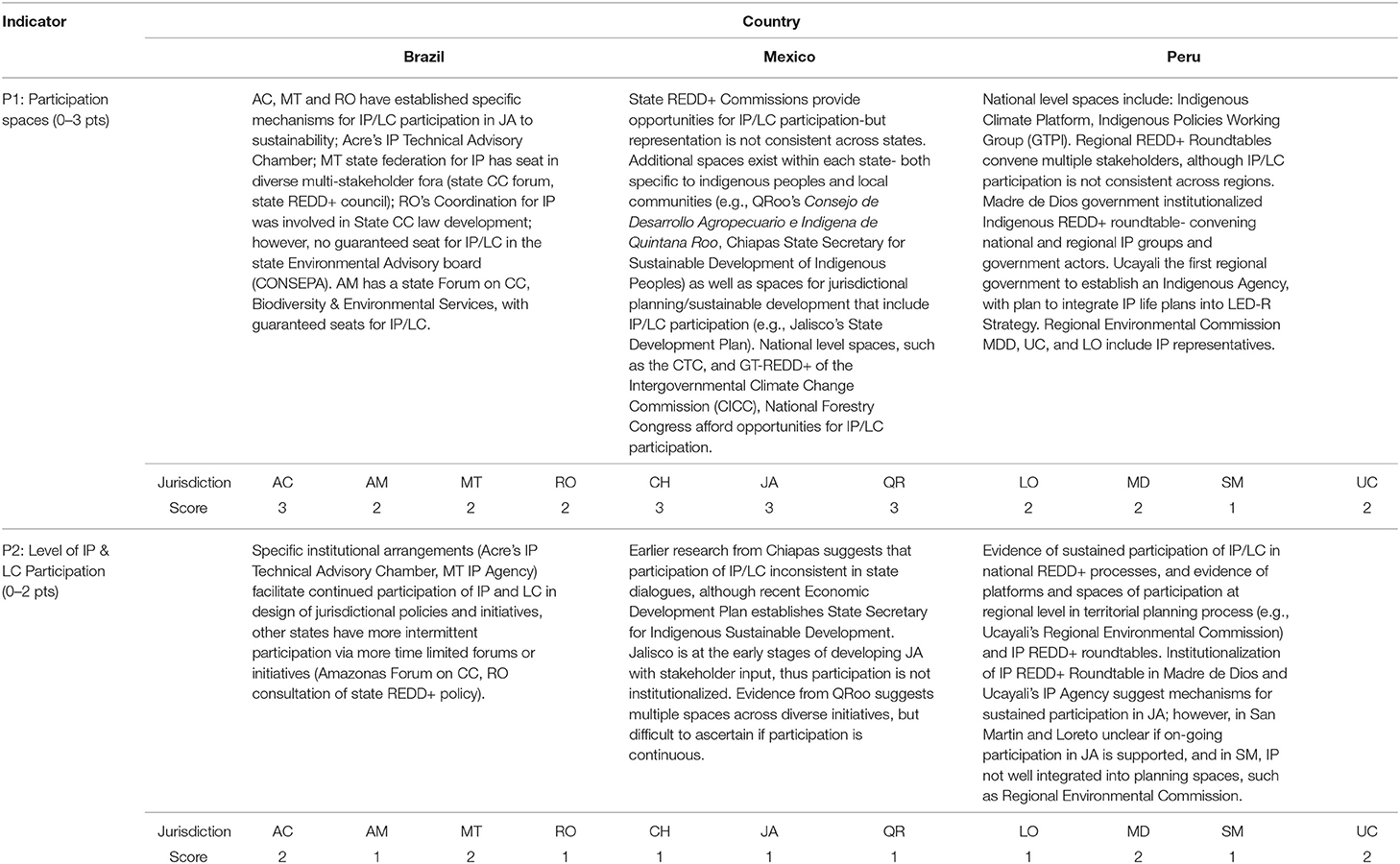

Participation

Our findings show that important spaces for participation and dialogue between IP and LC and subnational governmental actors are opening in tropical forest jurisdictions (Table 5; Figure 2C). The extent to which subnational jurisdictions have established and/or supported platforms for participation and inclusion of IP and LC in jurisdictional sustainability initiatives (P1) to date varies across study jurisdictions. Four subnational jurisdictions demonstrated progress in establishing institutional arrangements that are specific to IP and LC issues around climate change mitigation. These include Acre's Indigenous Peoples Technical Advisory Chamber, which advises the state government on SISA, and the newly formed space in Mato Grosso in which representatives of the state's indigenous peoples federation (FEPOIMT) worked with representatives of the state-level environmental agency to design and negotiate the IP sub-program as part of the state REDD+ Program.

An additional five jurisdictions demonstrated IP and LC representation in multi-stakeholder forums around jurisdictional initiatives for climate change mitigation, while some participation platforms are more temporary or ad-hoc. Where REDD+ processes have been more centralized, as in Peru and Mexico, IP and LC have made inroads in participation spaces at the subnational level via national processes, with varying degrees of success. In Mexico, the national framework for REDD+ established a hierarchical structure for stakeholder participation, with state and national level committees. The extent to which IP and LC are represented in state level committees varies from state to state. For example, our research in 2016 found that Oaxaca's state-level REDD+ committee was dominated by indigenous forestry organizations; in contrast, Chiapas' state committee had no indigenous representation at the time of the study (DiGiano et al., 2016). State-level agencies focused on IP and LC, as well as IP and LC engagement in state-level planning processes (e.g., Economic Development Plans), have facilitated IP and LC participation in initiatives, although the depth and effectiveness of this participation is difficult to measure. In Peru, the Regional Government of Ucayali established Peru's first Indigenous Peoples Agency in 2018. Importantly, this agency sits within the Agency of Regional Development, opening up new spaces for IP participation in regional development and planning processes. To date, no other regional level IP Agencies exist in Peru, although different types of formal spaces exist for IP and LC participation within government agencies and multi-stakeholder commissions. For example, Regional Environmental Commissions in Loreto, Madre de Dios and Ucayali have seats for IP and LC representatives.

Due to limitations of our data, assessing the level of participation of IP and LC (P2) within these fora was challenging. We assessed jurisdictions where participation spaces were institutionalized as indicating continued participation, as opposed to intermittent participation, linked to a specific initiative. Some examples of spaces that are institutionalized in subnational government processes for jurisdictional sustainability include Acre's IP Technical Advisory Chamber, Chiapas state secretary for Indigenous Sustainable Development (established via the state's 2018 Economic Development Plan), Madre de Dios' IP REDD+ roundtable, which was formalized by the Regional Government in 2013, and Ucayali's IP Agency. Findings suggested that while IP and LC were participating in diverse spaces at the subnational level (e.g., Amazonas Forum for Climate Change, dialogues around state REDD+ policy in Rondônia, Quintana Roo municipal councils), these spaces did not secure sustained and consistent participation by IP and LC.

Benefit-Sharing

We assessed the extent to which benefits to protect rights and enhance livelihoods (via support for titling, territorial governance, life plans, resource management) exist as part of jurisdictional programs for climate change mitigation and sustainable development (Indicator B1) (Table 6; Figure 2D). Only 2 of the 11 study jurisdictions (Acre and Amazonas) have disbursed benefits and incentives for IP and LC as part of jurisdictional programs; these include Acre's SISA and Amazonas' Forest Assistance (Bolsa Floresta) program. The state of Acre developed an IP sub-program as part of SISA, with performance-based finance from Germany's REDD+ Early Mover Program (REM). During the first REM Phase (2013–2017), USD 3 million of the state's 4-year contract was channeled to the IP sub-program of SISA. An Indigenous Peoples Working Group, comprised of state and federal government representatives and representatives of IP associations, determined the allocation of these funds to support Life Plans for 19 indigenous territories, as well as an Indigenous Agroforestry Agents rural extension program (DiGiano et al., 2018). Brazil's Amazon Fund directed $11 million USD to Amazonas' Forest Assistance Program to control deforestation and support the livelihoods of traditional populations in 16 protected areas (Stickler et al., 2020). Mato Grosso formally established the second state-level indigenous peoples Sub-program, as part of its state REDD+ program supported by REM, in 2018. After a statewide consultation process with IP and negotiations between the state Federation of Indigenous Peoples (FEPOIMT), Mato Grosso State Secretary for Environment and REM, a benefit distribution plan was established (Alencar et al., 2018). As REM benefits have yet to be distributed, we assigned Mato Grosso an intermediate score for benefit-sharing.

We found that outside of Brazil, very few jurisdictions demonstrate advanced baseline conditions in terms of benefits targeting IP and LC as part of jurisdictional approaches to sustainability; however, in some jurisdictions national or multilateral initiatives are bringing some benefits to the ground. In Peru, benefits to IP and LC were channeled through national programs financed by international results-based payment mechanisms, including Peru-Norway-Germany agreement committing USD 546 million in finance for reduction in emissions and the Forest Investment Program (FIP). Results based finance has been invested in initiatives to title and register lands, such as the Rural land titling and Registration Project (PTRT-3) and the Cuatro Cuencas project in Loreto (Lozano, 2018; Savedoff, 2018). A national-level forest conservation program (Programa Nacional de Conservación de Bosques—PNCB) has funded conservation agreements between regional governments and IP and LC communities for sustainable forest management activities via a payments for environmental services (PES) type program of conditional direct cash transfers, which also includes safeguards for IP. In Loreto, 30 IP communities have received funding through this program (Chan et al., 2018). In Mexico, the Forest Carbon Partnership Facility (FCPF) provides benefits to IP to LC within pilot jurisdictions through the Emissions Reductions Initiative (including all study sites), supporting programs for community forest management, silvopastoral systems, and river restoration, among other initiatives to support capacity building and REDD+ readiness. FCPF finance has been complemented by state-level PES initiatives benefiting IP and LC in Quintana Roo and Jalisco (proposed but not yet implemented).

Discussion

Jurisdictional sustainability initiatives represent new opportunities to strengthen environmental governance in tropical forest regions, as well as opportunities to test new models for collaboration among state and non-state actors (Turnhout et al., 2016). The Principles emerged as a potential blueprint for collaboration between subnational governments, indigenous peoples and local communities in the context of subnational action for climate change mitigation, and as a means to operationalize government commitments to partner with these critical stakeholders. The GPC define the terms of engagement between IP and LC and their potential subnational government partners within these experimental forms of environmental governance, focusing on critical demands of rights recognition, rights security, participation and benefits. Addressing those critical demands as part of jurisdictional strategies has the potential to facilitate regional transitions toward sustainability that strive to achieve systemic changes in governance, policies and incentives. Further, by expanding jurisdictional sustainability to include a mobilization around rights recognition, livelihoods and different ways of knowing and valuing forests, government-led climate change mitigation efforts can garner broader societal support, especially from forest-dependent peoples who see forests not just for their potential to reduce emissions, but also as sources of livelihoods, well-being and culture (Scoones, 2016). In doing so, the Principles could potentially help bridge a critical social justice gap in sustainable development strategies that has yet to be fully addressed. Our assessment of 11 tropical forest jurisdictions in Brazil, Mexico, and Peru in terms of their baseline conditions in meeting the commitments laid out in the GPC demonstrates that there is still a long road ahead in sufficiently bridging the social justice gap and realizing the potential of the GPC. Here we highlight three main gaps and suggest potential future directions in monitoring the Principles.

Bridging the Gap Between Rights Recognition and Rights Security

Findings from study jurisdictions demonstrate what scholars have found to be a critical gap between de jure rights recognition and the implementation and security of those rights on the ground (Rights Resources Initiative, 2015). The gap between rights recognition and rights security may undermine human rights, as well as our ability to mitigate climate change. Recent research provides further evidence that while IT and LC lands oftentimes act as a buffer to deforestation occurring outside their borders, lack of security of IP and LC rights may enable forest degradation and disturbance within IT and LC lands (Walker et al., 2020). Formal rights recognition of IT and community lands has been proposed as a critical pathway to slowing deforestation (Blackman et al., 2017; Fa et al., 2020), and recent global assessments by IPBES and IPCCC recommend strengthening IP and LC land rights as part of nature-based climate solutions (Díaz et al., 2019; IPCC, 2019). However, formal recognition is not enough to secure those rights.

Our findings highlight several barriers to effectively bridging the gap between rights recognition and rights security, as well as suggest some opportunities. One key barrier is a scale mismatch between domain of authority regarding IP and LC rights (oftentimes national) and the scale at which jurisdictional sustainability initiatives are most often being implemented (subnational). Despite legal frameworks in place to recognize IP and LC rights at the national level, subnational governments may or may not be able to fully recognize and respect IP and LC rights, including clarifying land tenure and implementing FPIC, due to limitations to their authority over indigenous and community lands and degree of decentralization of those authorities (Busch and Amarjargal, 2020; Libert-Amico and Larson, 2020). In Brazil, for example, as indigenous territories fall under the federal domain, states can and may defer any responsibilities regarding these lands to federal authorities, who are often geographically removed, with low capacity and limited resources to address issues related to territorial security. In Peru, land titling is decentralized, following a 2006 decree which gave regional governments the authority to title lands; however, absence of official land registries, insufficient resources and capacity, as well as conflicts with firmly entrenched interests and overlapping claims present major obstacles to progress (Monterroso et al., 2017).

We found that processes to clarify and secure rights are constrained in most study regions by insufficient integrated spatial planning, in some cases, complicated by lack of official maps of land rights (as in Peru), or land registries that are outdated and/or are from diverse and sometimes conflicting sources. Previous research has proposed that spatial planning is a critical aspect of jurisdictional sustainability approaches (Stickler et al., 2018b). Our findings suggest that subnational spatial planning processes have the potential to elucidate overlapping rights and advance recognition and protection of IP and LC rights despite lack of authority over titling per se. For example, Acre pioneered a state process of Environment and Economic zoning, which allowed IT that were not yet formally recognized by the federal government to be integrated into the state's land use plan (DiGiano et al., 2018). However, spatial planning processes must consider and reconcile diverse claims to rights and resources and mitigate risks that powerful interests will override ancestral or informally recognized rights holders.

Jurisdictional approaches to sustainability are opportunities to reconfigure governance, through bottom-up policy experimentation, as opposed to top-down, nationally-driven agendas, and protagonism of subnational governments (Boyd et al., 2018). Our findings suggest that multi-level governance structures, established in the context of REDD+ programs, offer opportunities to navigate, and perhaps reconcile, distinct levels of authority and decision-making, with the potential to bring the issue of rights recognition and rights security to the fore (Sikor et al., 2010). In both Brazil and Mexico, national and state-level REDD+ councils are spaces in which distinct levels of authority come together, in theory, to design and consult on REDD+ policies. These represent important spaces for coordination between national and subnational governments, as well as for leveraging IP and LC input to inform government actions, especially where IP and LC needs, interests and demands may be typically absent or marginalized (Ford et al., 2016). However, within these nested structures it is important to clarify decision-making power and its implications (Ravikumar et al., 2015); otherwise, there is a risk that commitments made by subnational governments will lack legitimacy if they are perceived to overstep their actual authority. Further, there is the risk of backlash by national governments in efforts to circumscribe subnational leadership, as evidenced by Brazilian President Jair Bolsonaro's (2020) decree excluding state governors from participating in Brazil's Council of the Legal Amazon (Matoso et al., 2020).

Direct threats to IP and LC rights, by means of legal reforms which curtail or undermine IP and LC rights, represent a second key barrier to bridging the gap between rights recognition and rights security within jurisdictional sustainability. In Brazil, President Bolsonaro's concerted attack on IP and LC rights in the name of economic development has gained international attention (Artaxo, 2019; Haaland and Wapichana, 2019; Londoño, 2019; Rocha, 2020) and sources cite increased violence against IP and traditional communities in Brazil (Ferrante and Fearnside, 2019; Cowie, 2020). In Peru and Mexico, proposed legal reforms, with the purported objective of facilitating investments and economic growth, loosen environmental regulations that protect community lands (Monterroso et al., 2017) and undermined rights to consultation to ease business for extractive industries (Ancheita and Wiesner, 2015). Scholars and human rights advocates have argued that legal reforms have worked in conjunction with stigmatization of IP and LC as “anti-development” to justify increasing violence against IP and LC who defend their rights (Zhouri, 2010; Andreucci and Kallis, 2017; Amnistía Internacional, 2018). Our findings indicate that across the study jurisdictions violence against IP and LC continues to go unpunished in many cases (Amancio and Castro, 2020).

The reconciliation of competing land uses and incentives has been posited as a critical component to advancing sustainable development (Nepstad et al., 2013; Sayer et al., 2013), and features prominently in jurisdictional approaches to sustainability (Stickler et al., 2018a). The explicit commitment to enhance protections of IP and LC environmental defenders in the GPC represents an opportunity to call greater attention to land and resource conflicts and human rights violations at the subnational level, and ultimately hold governments more accountable for addressing the root causes of conflicts.

Finally, international coalitions may play an important role in bridging the gap between rights recognition and rights security. Groups such as the GCF Task Force and global IP and LC organizations, which were critical in the design and endorsement of the Principles from 2016 to 2018, have used their collective voice to support mainstreaming the GPC into subnational policies (Scanlan-Lyons et al., 2018). Most recently, these groups successfully lobbied for the inclusion of the GPC as part of the criteria to be used by the state of California, USA, as it considers partnering with tropical forest jurisdictions on climate change mitigation initiatives (GCF Task Force Global Committee for Indigenous Peoples Local Communities, 2018). This represents an important step toward translating the Principles into legal frameworks and signals that tropical forest jurisdictions must demonstrate progress on their commitments, both environmental and social, to access potential performance-based incentives for reducing emissions. International actions and advocacy can also help foster and support local changes where IP and LC face barriers in making inroads at the national level (Keck and Sikkink, 1999).

Bridging the Gap Between Participation and Collaboration

Jurisdictional approaches to sustainability are considered effective pathways to change, in part, because they may be more finely attuned to the realities of stakeholders on the ground, as opposed to top-down or nationally driven agendas (Stickler et al., 2014, 2018b; Boyd et al., 2018). Along a similar vein, scholars have argued that effective nature-based climate solutions must involve IP and LC and be inclusive of their needs and perspectives (Brondizio and Le Tourneau, 2016). However, our understanding is still limited regarding how participation translates into effective collaboration and the increased ability of IP and LC to inform or co-design policies and programs that directly affect them. Our findings indicate that IP and LC and subnational governments are increasingly engaged in dialogues around climate change. New spaces for IP and LC participation have emerged in the context of national REDD+ programs in Peru and Mexico, and within state programs in Brazil, through programs such as Germany's REDD+ Early Mover Program. Acre's Indigenous Peoples Technical Advisory Chamber demonstrates how input from IP has been institutionalized into decisions regarding the state's SISA program (DiGiano et al., 2018). Members of the technical chamber make decisions regarding the allocation of REM benefits as part of the IP sub-program, which are then brought to the State Commission for Validation and Monitoring (CEVA), which is a multi-stakeholder commission made up of public authorities and civil society to approve investments (DiGiano et al., 2018).

Despite the existence of these participation spaces, there is little evidence regarding the extent to which IP and LC participation in these spaces is translating into input into policy outcomes at the subnational level, or into partnerships between IP and LC and governments, with some exceptions as referenced above. For example, there is no mandate requiring input from Mexico's state REDD+ committees into decision-making processes, and IP and LC participation in the national REDD+ consultation process was characterized by a one-way information flow to inform communities, rather than solicit input into program design (DiGiano et al., 2016; Špirić et al., 2016, 2019). Our analysis demonstrates that the simple existence of a participation space must be more explicitly distinguished from the effectiveness or efficacy of that space in informing the design and implementation of jurisdictional programs. As Paulson et al. (2012) notes, “Participation is a far more complex process than representation.” In other words, simply bringing the right actors into the room does not guarantee effective participation or collaboration, nor does consultation of IP and LC mean that participants can then influence decisions (Paavola, 2007; Brugnach et al., 2014).

As subnational jurisdictions strive to strengthen and guarantee participation of IP and LC in jurisdictional approaches, they must also recognize and address heterogeneity and diverging interests within and across diverse groups of IP and LC (Agrawal and Gibson, 1999; Kohler and Brondizio, 2017). Blom et al. (2010) found that many integrated conservation and development projects (ICDPs) did not pay sufficient attention to complexity, diversity and power imbalances within communities, in some cases leading to their failure. Transformative change at the jurisdictional scale will require not only the participation of IP and LC, but also actors from diverse sectors, including those with entrenched interests in a business-as-usual scenario (Di Gregorio et al., 2012). Looking to the precursors of jurisdictional approaches, such as ICDPs, REDD+ projects and sustainable supply chain initiatives, can help inform our understanding of how participation is shaped by existing power dynamics and histories, avoid past mistakes and assumptions regarding participation, as well as identify different tools for participation tailored to the distinct scales and contexts of jurisdictional programs (Reed, 2008; Blom et al., 2010; Scoones, 2016).

Bridging the Gap Between Recognition and Benefit-Sharing

We found that despite increased recognition of IP and LC contributions to climate change mitigation, far more benefits must reach the ground to support and enhance IP and LC livelihoods. Jurisdictional sustainability initiatives, in contrast to project-based approaches, are poised to bring more systemic benefits in the way of policies and programs that can meet the specific needs and demands of IP and LC and address the array of pressures on IP and LC lands from outside their borders (DiGiano et al., 2016). For example, Acre's jurisdictional program (SISA) has supported a program for indigenous agroforestry agents, who provide extension services to the majority of the state's IT (DiGiano et al., 2018). Importantly, the decision to channel benefits to this program was made in conjunction with the state's Indigenous Peoples Technical Advisory Chamber to SISA which determines benefits distribution within the indigenous peoples sub-program. Acre's experience in designing a benefit-sharing mechanism for pay-for-performance finance via the indigenous peoples sub-program has served as a model for other REM program beneficiaries, like the state of Mato Grosso, which has established guidelines for its own indigenous peoples sub-program through continued dialogue with the states' IP. The REM program has set stringent standards for benefit-sharing with IP as conditions for pay-for-performance finance, signaling an important role for donors in assuring that benefits reach IP and LC.

Within jurisdictional programs, benefits should reflect the values, agendas and goals of IP and LC, and may include a range of financial and non-financial benefits. IP have sought to integrate support for community Life Plans, which delineate a strategic vision for a community or tribe, into climate change mitigation benefit schemes. The Coordinator of Indigenous Organizations of the Amazon Basin (COICA) have established an Indigenous REDD Program (REDD Indígena Amazónica), which among other goals, seeks to channel benefits to support Life Plans. One indigenous leader from the Peruvian Amazon stated, “REDD+ should not define the long-term life plans of indigenous peoples, it is the life plans that should define REDD+” (DiGiano et al., 2016).

How benefits are designed and by whom is closely linked to self-determination, and the notion of justice when defined as the freedom to function and develop in a self-defined way (Sen, 2005; Schlosberg, 2013). In calling governments to integrate diverse knowledges and values of IP and LC into the design of policies and incentives, the GPC can support self-determination and enhance livelihoods. Some examples from our research and beyond demonstrate that IP, LC and governmental collaborations can support self-determination, and therefore advance social justice as part of climate change mitigation programs. The partnership between the state of California, USA and the Yurok Tribe demonstrates how a climate change policy, in this case California's forest offset program, served as a space for the Yurok tribe to assert their right to self-determination and as a space to co-design how the state program could benefit tribes in California (Scanlan-Lyons et al., 2018). Further analysis and metrics are needed to determine to what extent jurisdictional sustainability initiatives are providing direct financial benefits to IP and LC, better monitor and evaluate non-financial benefits to IP and LC and understand the implications of benefits for IP and LC self-determination.

Monitoring the Guiding Principles of Collaboration—Challenges and Future Directions

The objective of the GPC was to create a set of universal guidelines regarding how IP, LC and subnational governments could partner on climate change mitigation, with the intent that individual jurisdictions could adapt the Principles to fit their own contexts and targets (Scanlan-Lyons et al., 2018). The application of this pilot methodology underscores some important shortcomings and challenges that should be addressed in future efforts to monitor the GPC. Challenges arose in accounting for diversity across study jurisdictions with regards to different levels of centralization, decision-making, as well as the diversity of IP and LC. One potential solution would be to adapt the proposed methodology for specific national contexts, as discussed in the case of the Sustainable Development Goals (Biermann et al., 2017) or as various commodity certification bodies have done (e.g., national interpretation of the Roundtable for Sustainable Palm Oil's Principles and Criteria; Garrett et al., 2016). How different levels of authority influence the policies or other actions that the proposed indicators measure must be accounted for and made explicit in the methodology (Biermann et al., 2012). Many policies and actions measured by the indicators are determined by national level processes (e.g., rights designation, prosecution of crimes against environmental rights defenders) and, in fact, fall outside of the domain of authority of subnational governments. Measuring subnational jurisdictions by a yardstick over which they exert little or no authority poses a risk to the legitimacy of these assessments and may reduce the willingness of governments to make such commitments. Tailoring commitments to national and subnational contexts and priorities will help elucidate important nuances in how IP and LC are defined and how their rights are recognized across diverse tropical forest nations. For example, we found that local communities especially are a poorly defined category under many legal frameworks, and thus the ability to track the recognition of their rights and their inclusion in policy-making arenas is dependent on how these actors are recognized.

A participatory approach to developing and deploying locally relevant indicators to monitor the GPC may help address some of the challenges identified in this pilot study. Stakeholder-driven approaches to monitoring have been posited to improve transparency, and in addition, resulting instruments may be used for both evaluative purposes as well as communication tools to inform diverse actors regarding a shared vision and responsibility regarding target commitments or actions (Domingues et al., 2018). Engagement of stakeholders in developing appropriate regional and jurisdiction-specific indicators and validating monitoring results could address some methodological challenges that arose due to our reliance on diverse datasets and diverse independent expert assessments of indicators within the same regional contexts. Stakeholder validation of monitoring results could be used to triangulate findings from expert assessments. Additional bias controls could include greater standardization of methodology among researchers to reduce inter-observer variation in indicator assessment.

Despite distinct challenges inherent in monitoring them, ambitious and aspirational goals such as those laid out in the Principles represent opportunities to bring new actors and new ideas into the discussion of jurisdictional sustainability and to engage new partnerships outside of traditional governance arrangements to advance implementation of commitments (Stevens and Kanie, 2016; Biermann et al., 2017). Further, the inclusion of stakeholders in developing and implementing monitoring systems may increase their perceived legitimacy, by facilitating the diffusion of knowledge to diverse actors and building trust through information sharing and transparency (Biermann et al., 2012). Stakeholder input into monitoring efforts can be further enhanced by interdisciplinary and collaborative research efforts that can integrate perspectives from legal scholars, anthropologists, and others (Biermann et al., 2012; Duchelle et al., 2015). Acknowledging the construction of monitoring indicators as a social process and ensuring that indicators are grounded in the realities of key stakeholders and users will help translate monitoring tools into instruments to inform policy (Hezri and Dovers, 2006).

Conclusion

By strengthening collaboration between governmental actors, indigenous peoples and local communities, and by integrating concerns regarding rights recognition, effective, and equitable participation and flow of benefits to IP and LC, jurisdictional approaches to sustainability have the potential to bridge the current gap between social justice and climate change mitigation. The GPC reflect core demands of IP and LC in the context of climate change mitigation, as well as reflect a call to integrate climate change mitigation goals into broader governance transformations. In doing so, the Principles provide a potential roadmap for providing greater visibility to social justice concerns in subnational climate action. Our assessment of 11 subnational jurisdictions in terms of their baseline conditions toward translating these aspirational principles into practice highlights that there is still a ways to go, especially in terms of implementing rights on the ground, securing effective participation of IP and LC within subnational dialogues, and leveraging IP and LC participation into benefits to address their needs and demands. Monitoring the implementation of the GPC should be part of efforts to track progress on international commitments to climate change mitigation. Future adaptations of our pilot methodology should consider adapting indicators to national contexts, incorporating key stakeholders in the design and implementation of efforts to monitor progress toward the GPC, and balancing complexity with simplicity. Beyond use as a means of tracking progress, monitoring the Principles can serve as a means to foster learning and knowledge exchange within and across tropical forest regions, communicate progress in bringing traditionally marginalized people into climate change dialogues, as well as illuminate critical gaps in policies and practices that continue to undermine IP and LC rights and climate justice.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets generated for this study are available on request to the corresponding author.

Author Contributions

MD and CS wrote the text of the paper. MD led design of the paper, monitoring methodology, data collection, and analysis with respect to indictors of GPC. CS and OD contributed to design of monitoring methodology. OD collected data on select jurisdictions. MD, CS, and OD analyzed those data.

Funding

This research was supported by grants to Earth Innovation Institute from the International Climate Initiative (IKI) of the Federal Ministry for the Environment, Nature Conservation and Nuclear Safety (BMU) of Germany (Grant 16_III_071_Global_A_Low-Emissions Rural Development), and the Norwegian Agency for Development Cooperation (Norad) (Grant: QZA-0701 QZA−16/0162 -Forests, Farms and Finance Initiative). CIFOR contribution to data collection was part of the Global Comparative Study on REDD+ (www.cifor.org/gcs) through support from the Norwegian Agency for Development Cooperation (Norad), the International Climate Initiative (IKI) of the German Federal Ministry for the Environment, Nature Conservation, Building and Nuclear Safety (BMUB), and the CGIAR Research Program on Forests, Trees and Agroforestry (CRP-FTA), with financial support from the donors contributing to the CGIAR Fund.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Monica de los Rios (EII Brazil), Gustavo Suárez de Freitas (EII Peru) for contributing overarching analyses. We would also like to acknowledge Charlotta Chan (EII) for helping with data collection, formatting, and editing and Rafael Vargas (EII) for help with design and formatting of figures.

Supplementary Material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/ffgc.2020.00040/full#supplementary-material

Footnotes

1. ^We define indigenous peoples using the characteristics outlined by the UN Permanent Forum on Indigenous Issues, which include: “Self- identification as indigenous peoples at the individual level and accepted by the community as their Member; Historical continuity with pre-colonial and/or pre-settler societies; Indigenous Peoples using the characteristics outlined; Strong link to territories and surrounding natural resources; Distinct social, economic or political systems; Distinct language, culture and beliefs; Form non-dominant groups of society; Resolve to maintain and reproduce their ancestral environments and systems as distinctive peoples and communities.” source: https://www.un.org/esa/socdev/unpfii/documents/5session_factsheet1.pdf

2. ^We define local communities as those who “do not self-identify as indigenous but who share similar characteristics of social, cultural, and economic conditions that distinguish them from other sections of the national community, whose status is regulated wholly or partially by their own customs or traditions, and who have long-standing, culturally constitutive relations to lands and resources.”—Definition used by IP and LC groups in a 2019 statement in response to the UNFCCC report.

3. ^The Governors' Climate and Forest Task Force is a coalition of 39 states, provinces and departments committed to mitigating climate change through forest conservation. Members encompass one-third of the world's tropical forests. See www.gcftaskforce.org.

4. ^https://docs.wixstatic.com/ugd/cb5e0d_39355e4046ed4369afc1f3d7fc7193d7.pdf

5. ^Governors' Climate and Forest Task Force. 2014. Rio Branco Declaration. Available online at: https://earthinnovation.org/wp-content/uploads/2014/10/RioBrancoDeclaration_EN.pdf (accessed February 14, 2020).

6. ^New York Declaration on Forests. 2014. Available online at: https://www.undp.org/content/dam/undp/library/Environment%20and%20Energy/Forests/New%20York%20Declaration%20on%20Forests_DAA.pdf (accessed February 14, 2020).

7. ^UNFCCC Paris Agreement. 2015. Available online at: https://unfccc.int/process/conferences/pastconferences/paris-climate-change-conference-november-2015/paris-agreement (accessed February 14, 2020).

8. ^International Labor Organization (ILO). Indigenous and Tribal Peoples Convention, C169, 27 June 1989, C169. Available online at: https://www.ilo.org/dyn/normlex/en/f?p=NORMLEXPUB:12100:0::NO::P12100_ILO_CODE:C169 (accessed February 13, 2020).

9. ^https://undocs.org/A/RES/61/295

10. ^https://redd.unfccc.int/fact-sheets/safeguards.html (accessed April 15, 2020)

11. ^https://unfccc.int/sites/default/files/english_paris_agreement.pdf (accessed April 15, 2020)

12. ^Guardians of the Forest: https://www.alleyesontheamazon.org/assets/2018/04/DECLARATION-OF-THE-GUARDIANS-OF-THE-FOREST.pdf (accessed April 15, 2020)

13. ^https://ipccresponse.org/home-en (accessed April 15, 2020)

14. ^Congress of the Republic of National climate change laws in Peru. 2018. Law No. 30754, Framework Law on Climate Change. Available online at: https://busquedas.elperuano.pe/normaslegales/ley-marco-sobre-cambio-climatico-ley-n-30754-1638161-1/ (accessed February 13, 2020).

15. ^Government of Mexico. 2012, updated 2018. General Law on Climate Change (LGCC). Available online at: http://www.diputados.gob.mx/LeyesBiblio/pdf/LGCC_130718.pdf (accessed February 13, 2020).

16. ^Government of Brazil. 2009. Law No. 12.187 Instituting the National Policy on Climate Change (PNMC). Available online at: https://www.preventionweb.net/files/12488_BrazilNationalpolicyEN.pdf (accessed February 13, 2020).

17. ^Government of Brazil. 2007. Decree No. 6.263, National Climate Change Plan (PNMC). Available online at: https://www.mma.gov.br/estruturas/smcq_climaticas/_arquivos/plano_nacional_mudanca_clima.pdf (accessed February 13, 2020).

18. ^Mexico, alienation rights are applied under certain circumstances following 1992 Agrarian reforms on non-forested social property regimes.

19. ^Government of the State of Mato Grosso. 2013. Law No. 9.878, creation of the State REDD+ System. Available online at: http://al.mt.gov.br/storage/webdisco/leis/lei-9878-2013.pdf (accessed February 13, 2020).

20. ^Government of the State of Jalisco. 2007. Law No. 21746, State Law on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples. Available online at: https://info.jalisco.gob.mx/gobierno/documentos/3139 (accessed February 13, 2020).

21. ^Government of the State of Chiapas. 1999 (revised 2014). Law No. 207. Law on the Rights and Cultures of Indigenous Peoples. Available online at: https://www.cndh.org.mx/sites/default/files/doc/Programas/Indigenas/OtrasNormas/Estatal/Chiapas/Ley_DCIChis.pdf (accessed February 13, 2020).