- Department of Pharmacy, University of Naples Federico II, Naples, Italy

Hypertriglyceridemia refers to the presence of elevated concentrations of triglycerides (TG) in the bloodstream (TG >200 mg/dL). This lipid alteration is known to be associated with an increased risk of atherosclerosis, contributing overall to the onset of atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease (CVD). Guidelines for the management of hypertriglyceridemia are based on both lifestyle intervention and pharmacological treatment, but poor adherence, medication-related costs and side effects can limit the success of these interventions. For this reason, the search for natural alternative approaches to reduce plasma TG levels currently represents a hot research field. This review article summarizes the most relevant clinical trials reporting the TG-reducing effect of different food-derived bioactive compounds. Furthermore, based on the evidence obtained from in vitro studies, we provide a description and classification of putative targets of action through which several bioactive compounds can exert a TG-lowering effect. Future research may lead to investigations of the efficacy of novel nutraceutical formulations consisting in a combination of bioactive compounds which contribute to the management of plasma TG levels through different action targets.

Introduction

Hypertriglyceridemia is defined as the presence of elevated concentrations of triglycerides (TG) in the bloodstream (TG >200 mg/dL) (1). Since these lipophilic molecules cannot travel freely within the blood, TG plasma concentration is represented by the sum of triglyceride-rich lipoproteins (TRLs), mainly, very-low-density lipoproteins (VLDL), chylomicrons and their remnants. Lipid disorders, including hypertriglyceridemia, are known to be associated with an increased risk of atherosclerosis, contributing overall to the onset of atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease (CVD) (2). Consequently, the management of lipid alterations for the prophylaxis of cardiovascular events is considered noteworthy. Guidelines for the reduction of plasma TG levels are based on both lifestyle intervention (e.g., decrease of body weight, reduction of dietary carbohydrates and alcohol intake, increased physical activity, etc.) and pharmacological treatment (1). However, it is well-known that poor adherence to lifestyle changes, medication-related costs, and side effects frequently associated with the pharmacological treatment, may limit the success of these interventions (3). Consequently, the search for alternative approaches to reduce plasma TG levels currently represents a hot research field. In this regard, an option for the management of hypertriglyceridemia may be represented by the supplementation with nutraceuticals, whose consumption is frequently associated with a good safety and tolerability profile (4).

The beneficial effects exerted on plasma lipid levels by numerous natural bioactive compounds are widely described in the scientific literature (5). Additionally, the metabolic targets through which these substances may improve TG levels seem to be different, suggesting a potential synergistic effect if administered in a properly combined way. The aim of this review is to summarize evidence about food-derived bioactive compounds involved in the management of plasma TG levels, with a specific focus on the data obtained from human studies and the putative action targets through which these natural substances may exert their beneficial effect.

Search Strategy

For the section on the main putative targets of action for the TG-lowering effect, we focused on pre-clinical studies. A comprehensive literature search was conducted using the PubMed-NCBI database listings for relevant publications. The combinations of the following keywords were used: “nutraceuticals,” “natural compounds,” “bioactive compounds,” “cardiovascular risk,” “hypertriglyceridemia,” “dyslipidemia,” “mechanisms of action,” and “targets of action.” A thorough screening in scientific literature databases was conducted for the section on the evidence from clinical trials. We exclusively included (i) published studies from the last 5 years, (ii) studies investigating the effects of chronic administration with food-derived bioactive compound-based supplements, excluding both acute studies and diet-intervention studies, and (iii) studies reporting the effect of exclusive nutraceutical supplementation, excluding those investigating the administration with pharmaceutical treatments.

Evidence From Clinical Trials

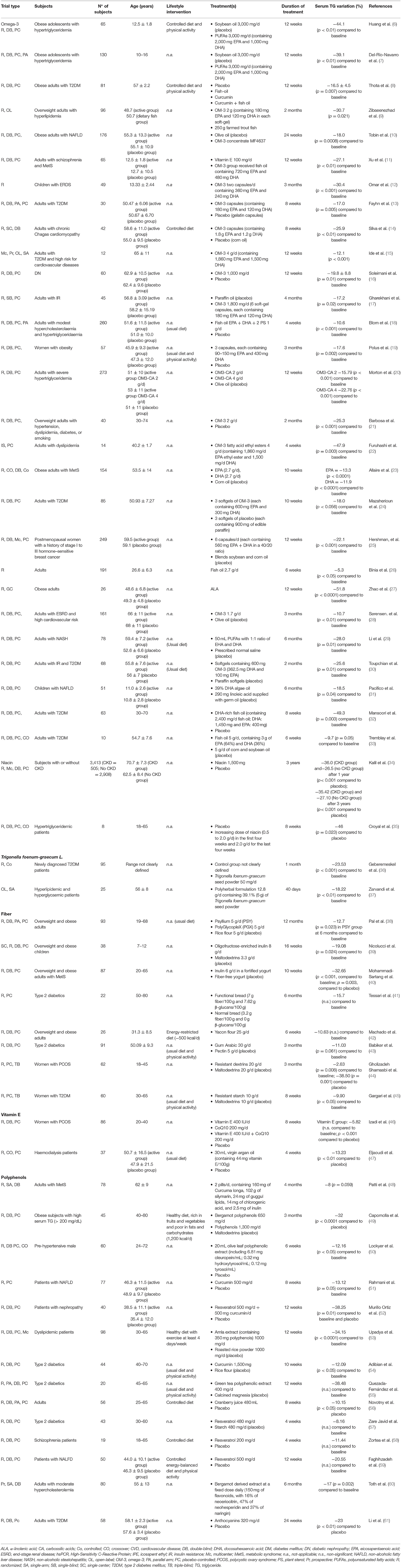

Although not directly investigating TG-reducing effects, several studies have reported the ability of such food-derived bioactive compounds to modulate lipid metabolism-related biomarkers, including serum TG. In various studies, these observations derived from investigation on diverse subjects, with or without pathological conditions, and, in many cases, within the evaluation of different outcomes. However, a modest number of studies described marked and significant TG-reducing effects, providing evidence for individuation of such effective phytochemicals for designing nutraceutical formulations. In this section we summarize the most relevant clinical trials reporting the TG-reducing effect of food-derived bioactive compounds (listed and detailed in Table 1), including omega-3 (6–33), niacin (34, 35), Trigonella foenum-graecum L. (36, 37), fiber (38–45), vitamin E (46, 47), and polyphenols (48–61).

Table 1. Most relevant published clinical trials from the last 5 years reporting TG-reducing effect after chronic supplementation with food-derived bioactive compounds.

Main Putative Targets of Action for the Reduction of Plasma Triglyceride Levels

Influence on Fatty Acid Beta-Oxidation

Fatty acid beta-oxidation is a metabolic process taking place in the mitochondrial matrix by which fatty acids (FAs) are broken down into acetyl-CoA units, with the release of energy in the form of adenosine triphosphate (ATP). The main regulation of this aerobic process occurs at the level of carnitine palmitoyltransferase I (CPT1), which is in turn inhibited by high concentrations of malonyl-CoA, the first intermediate in FA synthesis. For this reason, FA catabolism and FA synthesis represent opposite metabolic pathways that cannot occur simultaneously (62). Plasma TG levels in humans are represented by the sum of the TG content in TG-rich lipoproteins (TRLs), mainly, postprandial chylomicrons and VLDL. Being plasma free fatty acids (FFA) one of the main sources for TRL synthesis (63), reduced availability of these substrates through the improvement of FA oxidation may represent a useful strategy, in order to achieve a decrease in plasma TG levels. Moreover, in a study conducted by Vega et al. (64), moderately obese patients with hypertriglyceridemia showed lower levels of 3-hydroxybutyrate (regarded as fatty acid oxidation marker) compared with normotriglyceridemic control group, suggesting that an impaired FA oxidation process may lead to an increase of plasma TG levels. Based on these observations, the study of bioactive compounds which act by improving FA degradation, appears currently noteworthy. In this regard, peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor alpha (PPARα) represents a key regulator of lipid metabolism, enhancing FA oxidation process and reducing fat storage (65). PPARα is one of the three subtypes of ligand-inducible transcription factors belonging to the superfamily of PPARs. The transcription factor PPARα is considered a sensor of endogenous lipids and it is found in organs subjected to lipid catabolism, such as liver, skeletal muscle, kidneys, heart, and brown fat (66). The improved expression of this nuclear receptor has several effects in the liver, including an up-regulation of the transcription of genes involved in peroxisomal and mitochondrial oxidation of FAs, such as acyl-CoA oxidase, CPT-I, and CPT-II (67).

The main pharmacological treatment that shows PPARα as a target of action is based on fibrates (68), drugs currently recommended for the management of hypertriglyceridemia by the European Society of Cardiology (ESC) and the European Atherosclerosis Society (EAS) (1). In the group of bioactive substances capable to affect TG metabolism through a PPARα-mediated pathway, a growing interest is focused on the supplementation with omega-3 fatty acids. Omega-3 and omega-6 fatty acids represent two categories of polyunsaturated fatty acids (PUFAs), whose consumption through diet is considered essential, due to the mammalian lack of ability to introduce double bonds into FAs. Fish is the main source of long-chain omega-3 FAs, mainly eicosapentaenoic acid (EPA) and docosahexaenoic acid (DHA), while some plant-based foods (such as flaxseed oil, soy and canola oil, chia seeds, pumpkin seeds and walnuts) contain omega-3 in the form of precursor alpha-linolenic acid (ALA) (69). PPARα is well-recognized to be directly bound and activated by omega-3, leading to the induction of genes involved in FA oxidation (70). An in vitro study also showed that the 9-oxo-10(E),12(Z),15(Z)-octadecatrienoic acid (9-oxo-OTA), an active compound deriving from ALA occurring in tomato fruit extract, was able to activate PPARα and induce mRNA expression of PPARα target genes in murine hepatocytes (71). Overall, based on this mechanism of action, and through other mechanisms described below, omega-3 may allow to address liver lipid metabolism toward a state of oxidation, rather than synthesis or accumulation.

It is still a matter of debate whether ALA itself mediates the effects on lipid metabolism and inflammation or if these beneficial effects are mediated by EPA and DHA. In this regard, a recent 12-week RCT investigated the effects of diets enriched with lean fish and fatty fish (animal source of omega-3) or Camelina sativa oil (vegetable source of omega 3 in the form of precursor ALA) in subjects with impaired fasting glucose. At the end of the study, the beneficial effects of fatty fish and Camelina Sativa oil on lipid metabolism were confirmed, while the increased concentrations of anti-inflammatory lipid mediator appeared to be associated with the intake of both plant and animal-based omega-3 PUFAs (72). Another evidence derives from a study conducted on healthy subjects with moderate dyslipidemia, in which the effect of a nutraceutical formulation, based on gastro-resistant capsules containing cryo-micronized chia seeds and vitamin E, was tested (73). Among plant-based sources of omega-3, chia (Salvia hispanica L.) is of major interest, not only as regards its high content of precursor ALA, but also for its omega-3:omega-6 FA ratio (~4:1) and its high content of dietary fiber, minerals, vitamins (e.g., niacin), and polyphenolic compounds (74). Considering the significant beneficial effects on plasma TG levels observed after 8 weeks of supplementation (−27.5%; p = 0.0095), this study provides further demonstration of ALA-mediated beneficial effects on lipid metabolism. Although omega-6 and omega-3 series are both essential, the balance of these FAs in the diet is critical. Based on the analysis of available literature, it was suggested an omega-6:omega-3 ratio of ~6:1, which results instead unbalanced in favor of omega-6 PUFAs in the typical Western diet, reaching a ratio of 15:1 or even greater. Since the long chain derivatives of omega-6 and omega-3 PUFAs depend on the same enzymes for their production (75), the efficiency of endogenous conversion of ALA into EPA and DHA is limited by the presence of high levels of omega-6 in the Western diet. In parallel, higher intake of omega-6 leads to an increased production of linoleic acid (LA) metabolites (such as arachidonic acid, ARA) compared to ALA metabolites (such as EPA and DHA). This has important practical implications in relation to the profoundly different biological effects of LA and ALA metabolites, especially for their inflammatory and anti-inflammatory activity, respectively (76).

Recently, curcumin, the active principle of turmeric (Curcuma longa), has gained a greater attention by scientific research as a potential agent for the management of hyperlipidemia (77). As regards the effects exerted on TG metabolism, curcumin was suggested to positively regulate FA beta-oxidation through the up-regulation of PPARα expression (78). PPARα was also reported to be directly bound and activated by astaxanthin, a carotenoid particularly abundant in seafood (e.g., kill oil), which demonstrated to reduce TG concentration in HepG2 cells through a PPARα-mediated mechanism of action (79). Furthermore, results from in vitro studies on bioactive compounds of tea suggested the regulation of PPARs subtypes as a putative mechanism of action that may lead to the hypotriglyceridemic effects observed in vivo. As previously reviewed (80), the activation of PPARα by epigallocatechin-3-gallate (EGCG) of tea would take place through an indirect mechanism of action. Blocking of the inhibitor of kB phosphorylation induced by EGCG may in fact determine the reduced activation of the nuclear transcription factor-kB (NF-kB). Since NF-kB may counteract the PPARα-mediated expression of genes involved in FA oxidation, its inhibition allows to avoid this undesirable interaction (81). In contrast, a dose-dependent direct interaction with the PPARα ligand-binding domain was reported in the case of linalool, an aromatic terpenoid found in tea (82).

Finally, among the natural bioactive compounds which could decrease plasma TG levels via PPARα, polyphenols play an important role, with particular regard to the class of flavonoids. For instance, cyanidin has proven to be a moderate PPARα ligand (83), while recent evidence has highlighted that proanthocyanidins from a grape seed extract could indirectly act on PPARα expression through the in vitro and in vivo inhibition of the activity of histone deacetylase class I (HDACs), mainly, of HDAC-3. Since the latter is a well-recognized repressor of PPARα expression (84), its inhibition can lead to an increase in PPARα phosphorylation and activation, resulting in an improvement of its targeted gene expression (85).

Reduction of Free Fatty Acid Flux to the Liver

Obesity is known to potentially contribute to the onset of several metabolic alterations, including hypertriglyceridemia, resulting in an overall increased risk of CVD (86). The increase in plasma TG levels may be related to an alteration of adipose tissue function. This alteration, called as “adiposopathy,” often occurs in the presence of visceral fat accumulation and can lead to a rise of intra-adipocyte lipolysis process (87). Free fatty acids (FFA) derived from adipose tissue lipolysis are subsequently released into the circulation and transported to the liver by hepatic artery and portal vein, causing an increase in the synthetic rate of TG (63). Hormone-sensitive lipase (HSL) is well-recognized as the key enzyme for TG mobilization, mainly, in adipose tissue and skeletal muscle, with an opposite function to that the lipoprotein lipase (LPL) (88). Among the TG-lowering agents, nicotinic acid (also known as niacin or vitamin B3), has proven to exert lipid-regulating effects when administered at high doses (1.5–6 g/d) (89). Although the mechanism of action of nicotinic acid in the management of lipid profile remains unclear, the potential of this organic compound to reduce the expression of HSL has been described (90). In addition, the niacin-mediated inhibition of HSL expression would occur more specifically in peripheral fat (91), where HSL seems to exert a major lipolytic capacity (92). Overall, the inhibition of this lipase may result in a decrease of FAs output from the adipose tissue, a reduced delivery of these molecules to the liver, and the consequent inhibition of hepatic TG synthesis.

Inhibition of Fatty Acid Synthesis

As described above, the main regulator of FA beta-oxidation is CPT1, which contributes to the transport of long-chain FA into the mitochondrial matrix. CPT1 is allosterically inhibited by high concentrations of malonyl-CoA, the first intermediate in the biosynthesis of FA. For this reason, FA catabolism and FA synthesis are opposite metabolic pathways which cannot occur simultaneously (62). The first enzyme involved in FA synthesis, and consequently in the intermediate production of malonyl-CoA, is acetyl CoA carboxylase (ACC). In turn, the activity of this enzyme results to be suppressed by the phosphorylation induced from adenosine monophosphate-activated protein kinase (AMPK), an essential regulator of energy metabolism (93). In this scenario, bioactive compounds with AMPK-activating capacity, represent potential candidate to help direct lipid metabolism toward a state of oxidation, rather than synthesis or accumulation. In this regard, as recently reviewed by Vazirian et al. (94), different bioactive compounds (e.g., curcumin, quercetin, resveratrol, berberine, ginsenosides and EGCG), demonstrated to activate AMPK, thus, contributing to the inhibition of ACC and FA synthesis.

Sterol-regulatory-element-binding protein 1c (SREBP-1c), together with the PPARs nuclear receptors, is recognized as one of the main transcription factors for the regulation of lipid metabolism. The activation of several FA synthase genes is regulated by this transcription factor, such as ACC, fatty acid synthase (FAS), and stearoyl-CoA desaturase (SCD). Therefore, the inhibition of SREBP-1c may lead to the lack of conversion of acetyl-CoA into FAs and the consequent process of lipogenesis (95). The expression of the nuclear receptor SREBP-1c is widely reported to be inhibited by PUFAs, but not from monounsaturated or saturated FAs (95, 96). Among PUFAs which can affect the activity of SREBP-1c, omega-3 play a major role. The hypotriglyceridemic effect of omega-3 is well-recognized, deriving not only from an increased lipolysis, as described above, but also from a reduction in the lipogenesis process. In particular, genes involved in the lipogenesis process (e.g., FAS, SCD1, and Δ6-desaturase) contain a sequence responsive to omega-3 in the promoter region, to which the transcription factor SREBP-1c binds (97). Moreover, different studies suggest that omega-3 may reduce SREBP-1c activity also through the proteasome-mediated degradation of this transcription factor (98, 99). Altogether, these effects lead to a reduced synthesis of fatty acids and triglycerides, followed by the lack of formation of nascent VLDL particles. Interestingly, it has been shown that the expression, as well as the nuclear transcription of SREBP-1c, could be also inhibited by dietary curcumin (100, 101).

The inhibition of SREBP-1c activity, as a putative mechanism of action which may contribute to the reduction of lipid synthesis, is also described in a study performed by Vijayakumar et al. (102). The authors conducted an in vitro study on HepG2 cells in which a down-regulation of SREBP-1c expression, both at the mRNA and protein level, was observed after treatment with a thermostable extract of fenugreek seeds. This effect was accompanied by a decreased expression of FAS enzyme and, consequently, a decrease in lipid synthesis. It is important to underline that, at a molecular level, the expression of SREBP-1c is suppressed by the farnesoid X receptor (FXR), another important transcription factor, belonging to nuclear receptors superfamily. This interaction is mediated by a signaling pathway involving small heterodimer partner (SHP) (103). This observation strongly suggests the use of substances capable of improving the activity of FXR, in order to obtain a plasma TG-lowering effect. Interestingly, results deriving from an in vitro study, showed the potential of procyanidins occurring in a grape seed extract in modulating positively FXR activity, enhancing the natural binding of this transcription factor by bile acids (104), and determining the in vivo reduction of plasma TG content. In addition, an in vitro study conducted by Zhao et al. (105) reported that PUFAs are selective modulators of FXR, specifically regarding ALA, DHA, and ARA. Since FXR plays a critical role in lipid metabolism, the interaction of PUFAs with this transcription factor was suggested as a further mechanism of action which may contribute to their beneficial effects on lipid profile.

Finally, an additional mechanism of action potentially involved in the inhibition of hepatic lipogenesis is the reduction of activity of TG-synthesize key enzymes, mainly, diacylglycerol O-acyltransferase (DGAT) and phosphatidic acid phosphatase (PAP). PAP is an enzyme which catalyzes the conversion of phosphatidic acid into diacylglycerol, while DGAT1 and DGAT2 are two enzymes which catalyze the last step in the biosynthesis of TG, both in the glycerol phosphate and monoacylglycerol pathways (106). Several studies suggest the beneficial effects of different bioactive compounds on lipid metabolism via the inhibition of these two enzymes, including omega-3 and nicotinic acid (107–111).

Increased Clearance of Plasma Triglyceride

Plasma TG levels are represented by the TG content of TRLs, mainly, postprandial chylomicrons and VLDL. Chylomicrons are the largest lipoprotein particles (about 1,000 nm) and are composed of TG (85–90%), phospholipids, cholesterol esters and 1–2% of different types of apolipoprotein (apoB48, apoCIII, apoCII, and apoE). These exogenous lipoproteins are formed in the small intestine after the ingestion of dietary fats and subsequently enter the blood circulation through the lymphatic system. In the vascular endothelium, the apoCII present on the surface of the chylomicrons activates the LPL which favors the lipolysis of TG. FFA and chylomicron remnants will result from this hydrolyzing process: the first products (FFA), based on individual metabolic needs, can be used by muscle cells as a source of energy or resynthesized into TG and stored in adipose cells, while the second products (chylomicron remnant particles) are removed from the circulation by the liver. Dietary fats are not the only source of TG, but can also be synthesized in liver cells and, together with apoB100, apoCIII, apoCII, and apoE, form VLDL particles, which are released into the bloodstream (112).

One of the putative strategies to obtain a plasma TG-lowering effect is represented by the supplementation with substances capable to increase the clearance of plasmatic TRLs. In this regard, LPL is considered a key enzyme for TG clearance and is known to be regulated by several factors. Particularly, apoCII represents an essential co-factor for LPL activation, whereas apoCIII may inhibit its action and, consequently, the resulting lipolysis process (113). In addition, apoCIII may contribute to the onset of hypertriglyceridemia through the stimulation of VLDL synthesis and the inhibition of hepatic remnants uptake (114). In this scenario, omega-3, whose use as a food supplement is widely extended for the management of TG levels, showed to act also through the increased LPL activity. Dietary long-chain omega-3 PUFAs have demonstrated to direct up-regulate LPL gene expression and PPARγ mRNA expression in cultured adipocytes (115, 116), and the agonism of this latter transcription factor may further contribute to enhance the LPL activity (117). Moreover, results obtained from an in vivo study showed a significant reduction in plasma TG levels in mice fed a high-fat diet, with the source of fat represented by omega-3 from fish oil, compared to other three diets (soy oil, a mix of soy oil and fish oil and a normal chow diet). Based on the obtained data, it was suggested that plasma TG-lowering effect, observed in the group of mice fed with fish oil, could depend on the increased LPL activity and, consequently, on the improved clearance of TRLs induced by omega-3 (118). Besides, the reduction of apoCIII plasma levels, as a mechanism that lead to an increased TRL cycle, was also observed in humans after the supplementation with EPA and DHA combined, or purified EPA (119, 120). Evidence from scientific literature also suggest a putative action of FXR in down-regulating apoCIII gene expression and up-regulating apoCII and VLDL-receptor gene expression (121–123). This observation may additionally support the hypothesis that bioactive compounds, capable of interacting with FXR, could exert beneficial effects on TG metabolism. Furthermore, as reviewed by Giglio et al. (124), polyphenols have demonstrated to reduce plasma TG levels via increasing the activity of LPL. In this context, flavonoids, phenolic acids (cinnamic acid), curcumin and sylimarin are the polyphenols with the most demonstrated beneficial efficacy (124).

Lipid metabolism is known to be also influenced by oxidative stress: an increase of oxidative state of the organism may contribute to lipid peroxidation, and this process may influence the activity of hepatic lipases, especially regarding LPL (125). As a proof of this, a positive correlation between the LPL activity and the serum total antioxidant capacity (TAC) of the organism was described (126). Based on this observation, two in vivo studies on streptozocin-induced diabetic rats showed the efficacy of a high supplementation with vitamin E in bringing TG back to normal levels. Considering the well-known antioxidant potential of vitamin E, these studies propose the efficacy of vitamin E in removing lipid peroxides in plasma and liver, as the potential mechanism that may lead to an increased activity of LPL (127, 128). In addition, a study performed on triton-treated hyperlipidemic rats showed a decrease in plasma TG levels after chronic feeding with fenugreek seed extract at a dosage of 200 mg/kg body weight. This lipid-lowering effect was accompanied by the activation of different hepatic lipases, including LPL, and by the concomitant reduction of plasma lipid peroxidation, as observed in vitro (129). However, these preliminary results should be deepened thoroughly, especially by performing clinical trials. Nevertheless, it is also important to underline the widely recognized importance of antioxidant dietary compounds, especially vitamin E, in counteracting the onset of diseases related to both liver fat accumulation and oxidative stress, such as non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) (130, 131).

Inhibition of Triglyceride Intestinal Absorption

The absorption of TG across the intestinal mucosa requires the conversion of these molecules from insoluble macroscopic particles into soluble micelles, which can be specific targets of intestinal enzymes. In this regard, the main enzyme responsible for the hydrolysis of total dietary fats is pancreatic lipase, which converts TG into diglycerides, monoglycerides, FFA, and glycerol (132). Orlistat, a drug approved by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for obesity treatment, acts as an inhibitor of pancreatic lipase enzyme activity and its administration also promotes the reduction of plasma TG levels in humans (133). In this scenario, interest in the use of natural bioactive compounds, capable of inhibiting pancreatic lipase, is increasingly emerging. The inhibition of pancreatic lipase by plant-derived molecules was recently reviewed by Rajan et al. (134), with a specific focus on the role of flavonoids, alkaloids, saponins and terpenoids. Among these bioactive compounds, the class of flavonoids showed the most powerful inhibiting activity on pancreatic lipase enzyme, and this potential effect was mainly dependent on molecule weight and position of hydroxyl groups (129). However, investigation of new classes of bioactive compounds with this potential beneficial activity is extensive and still ongoing (135).

Dietary fibers are other significant food components capable to counteract the absorption of postprandial TG. It is known that fiber can reduce the absorption of fats in the small intestine, thus decreasing the production of TRLs, mainly chylomicrons (136). In particular, in vitro studies have shown that dietary fibers may affect lipid metabolism mainly through two different mechanisms of action: (1) soluble fibers are capable of creating viscous solutions in the gastrointestinal tract delaying lipid absorption and transit in the small intestine (137); (2) other fibers, such as chitosan, can directly bind lipid globules, with the final result of inhibiting lipolysis (138). At this regard, animal-based studies with chitosan supplementation have demonstrated the ability of this biopolymer in reducing plasma TG levels, supporting a chitosan derived reduction in lipid absorption (139). Nonetheless, different studies showed that dietary fiber, such as pectin, can inhibit lipase enzyme activity (140–142). Overall, research on bioactive substances potentially capable of reducing the absorption of dietary fats, may be considered as an interesting strategy for the management of plasma TG levels, especially during the postprandial state.

Conclusion

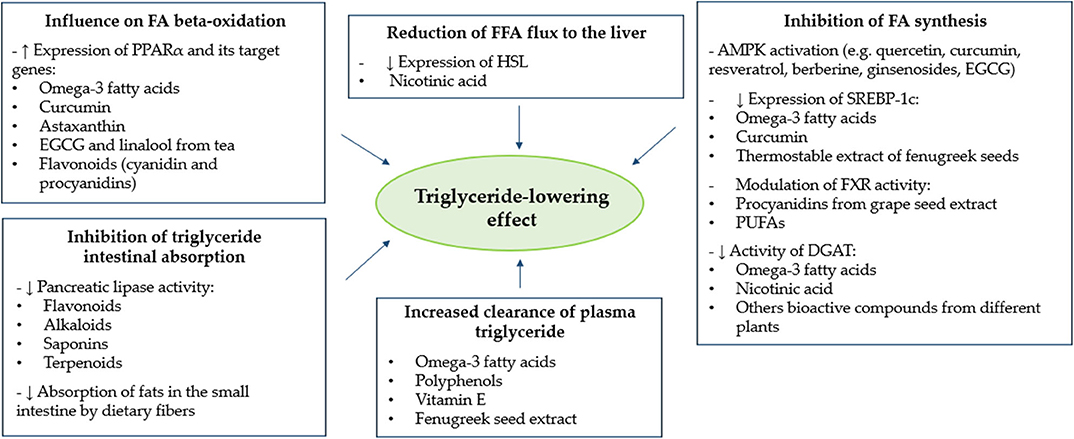

In the present review, we summarized the most relevant evidence about the TG-reducing effect of different food-derived bioactive compounds. In this regard, after analysis of the available scientific evidence, we have identified omega-3, niacin, vitamin E, Trigonella foenum-graecum L, fibers and polyphenols, as agents with a demonstrated plasma TG-lowering effect after a chronic supplementation in humans. Moreover, analysis of data obtained from in vitro studies allowed us to describe and classify the main putative targets of action through which several bioactive compounds may exert a beneficial effect on plasma TG metabolism. As shown in Figure 1, such action targets include (a) influence on FA beta-oxidation, (b) reduction of FFA flux to the liver, (c) inhibition of FA synthesis, (d) increased clearance of plasma TG, and (e) inhibition of TG intestinal absorption. The increase of FA beta-oxidation and the inhibition of FA synthesis represent two different and opposite targets of action which, in both cases, may lead to an increased rate of FA oxidation, rather than synthesis or accumulation. Since TG molecules are composed of FAs, it is reasonable to hypothesize that the effects of food-derived bioactive compounds on these two targets may lead to a final TG-lowering effect. Furthermore, two other putative metabolic targets are the reduction of FFA flux to the liver and the increased clearance of plasma TG. In both cases, the effect of bioactive compounds described above would be mediated by the reduced and increased activity of HSL and LPL, respectively. Plasma TG can origin from FAs provided from both endogenous and exogenous sources (112). The inhibition of intestinal absorption of TG represents the last target of action described in this review, and it refers, specifically, to the improved metabolism of TG from exogenous sources (dietary food).

Figure 1. Main putative action targets of different bioactive compounds for the reduction of plasma triglyceride levels. AMPK, adenosine monophosphate-activated protein kinase; DGAT, diacylglycerol O-acyltransferase; EGCG, epigallocatechin-3-gallate; FA, fatty acid; FFA, free fatty acid; FXR, farnesoid X receptor; HSL, hormone-sensitive lipase; PPARα, peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor alpha; PUFAs, polyunsaturated fatty acids; SREBP-1c, sterol-regulatory-element-binding protein 1c.

To our knowledge, this is the first report focusing on the description and categorization of putative mechanisms of action through which different natural bioactive substances may determine, in a directly or indirectly manner, a TG-reduction effect. Notably, the TG metabolic targets of nutraceuticals may be different, and the same substance can exert a beneficial effect at distinct levels. It could be hypothesized that the appropriate combination of different bioactive compounds may determine an additional, or even synergistic, beneficial effect on plasma TG levels in humans. The investigation of these possible synergistic actions currently represents an interesting line of research. More scientific evidence, deriving from well-designed intervention studies, are needed to deepen this aspect.

Author Contributions

All authors listed have made a substantial, direct and intellectual contribution to the work, and approved it for publication.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

References

1. Mach F, Baigent C, Catapano AL, Koskinas KC, Casula M, Badimon L, et al. 2019 ESC/EAS Guidelines for the management of dyslipidaemias: Lipid modification to reduce cardiovascular risk. Eur Heart J. (2020) 41:111–88. doi: 10.15829/1560-4071-2020-3826

2. Rygiel K. Hypertriglyceridemia - common causes, prevention and treatment strategies. Curr Cardiol Rev. (2018) 14:67–76. doi: 10.2174/1573403X14666180123165542

3. Marzec LN, Maddox TM. Medication adherence in patients with diabetes and dyslipidemia: associated factors and strategies for improvement. Curr Cardiol Rep. (2013) 15:418. doi: 10.1007/s11886-013-0418-7

4. Cicero AFG, Colletti A, Bajraktari G, Descamps O, Djuric DM, Ezhov M, et al. Lipid lowering nutraceuticals in clinical practice: position paper from an International lipid expert panel. Arch Med Sci. (2017) 13:965–1005. doi: 10.5114/aoms.2017.69326

5. Rizzo M, Patti AM, Al-Rasadi K, Giglio RV, Nikolic D, Mannina C, et al. State of the art paper natural approaches in metabolic syndrome management. Arch Med Sci. (2018) 14:422–41. doi: 10.5114/aoms.2017.68717

6. Huang F, del-Río-Navarro BE, Leija-Martinez J, Torres-Alcantara S, Ruiz-Bedolla E, Hernández-Cadena L, et al. Effect of omega-3 fatty acids supplementation combined with lifestyle intervention on adipokines and biomarkers of endothelial dysfunction in obese adolescents with hypertriglyceridemia. J Nutr Biochem. (2019) 64:162–9. doi: 10.1016/j.jnutbio.2018.10.012

7. Del-Rió-Navarro BE, Miranda-Lora AL, Huang F, Hall-Mondragon MS, Leija-Martínez JJ. Effect of supplementation with omega-3 fatty acids on hypertriglyceridemia in pediatric patients with obesity. J Pediatr Endocrinol Metab. (2019) 32:811–9. doi: 10.1515/jpem-2018-0409

8. Thota RN, Acharya SH, Garg ML. Curcumin and/or omega-3 polyunsaturated fatty acids supplementation reduces insulin resistance and blood lipids in individuals with high risk of type 2 diabetes: a randomised controlled trial. Lipids Health Dis. (2019) 18:31. doi: 10.1186/s12944-019-0967-x

9. Zibaeenezhad MJ, Ghavipisheh M, Attar A, Aslani A. Comparison of the effect of omega-3 supplements and fresh fish on lipid profile: a randomized, open-labeled trial. Nutr Diabetes. (2017) 7:1. doi: 10.1038/s41387-017-0007-8

10. Tobin D, Brevik-Andersen M, Qin Y, Innes JK, Calder PC. Evaluation of a high concentrate omega-3 for correcting the omega-3 fatty acid nutritional deficiency in non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (CONDIN). Nutrients. (2018) 10:1126. doi: 10.20944/preprints201807.0240.v1

11. Xu F, Fan W, Wang W, Tang W, Yang F, Zhang Y, et al. Effects of omega-3 fatty acids on metabolic syndrome in patients with schizophrenia: a 12-week randomized placebo-controlled trial. Psychopharmacology. (2019) 236:1273–9. doi: 10.1007/s00213-018-5136-9

12. Omar ZA, Montser BA, Farahat MAR. Effect of high-dose omega 3 on lipid profile and inflammatory markers in chronic hemodialysis children. Saudi J Kidney Dis Transpl. (2019) 236:1273–9. doi: 10.4103/1319-2442.261337

13. Fayh APT, Borges K, Cunha GS, Krause M, Rocha R, de Bittencourt PIH, et al. Effects of n-3 fatty acids and exercise on oxidative stress parameters in type 2 diabetic: a randomized clinical trial. J Int Soc Sports Nutr. (2018) 15:18. doi: 10.1186/s12970-018-0222-2

14. Silva PS Da, Mediano MFF, Silva GMS Da, Brito PD De, Cardoso CSDA, Almeida CF De, et al. Omega-3 supplementation on inflammatory markers in patients with chronic chagas cardiomyopathy: a randomized clinical study. Nutr J. (2017) 16:36. doi: 10.1186/s12937-017-0259-0

15. Ide K, Koshizaka M, Tokuyama H, Tokuyama T, Ishikawa T, Maezawa Y, et al. N-3 polyunsaturated fatty acids improve lipoprotein particle size and concentration in Japanese patients with type 2 diabetes and hypertriglyceridemia: a pilot study. Lipids Health Dis. (2018) 17:51. doi: 10.1186/s12944-018-0706-8

16. Soleimani A, Taghizadeh M, Bahmani F, Badroj N, Asemi Z. Metabolic response to omega-3 fatty acid supplementation in patients with diabetic nephropathy: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Clin Nutr. (2017) 36:79–84. doi: 10.1016/j.clnu.2015.11.003

17. Gharekhani A, Dashti-Khavidaki S, Lessan-Pezeshki M, Khatami MR. Potential effects of omega-3 fatty acids on insulin resistance and lipid profile in maintenance hemodialysis patients a randomized placebo-controlled trial. Iran J Kidney Dis. (2016) 10:310–8.

18. Blom WAM, Koppenol WP, Hiemstra H, Stojakovic T, Scharnagl H, Trautwein EA. A low-fat spread with added plant sterols and fish omega-3 fatty acids lowers serum triglyceride and LDL-cholesterol concentrations in individuals with modest hypercholesterolaemia and hypertriglyceridaemia. Eur J Nutr. (2019) 58:1615–24. doi: 10.1007/s00394-018-1706-1

19. Polus A, Zapala B, Razny U, Gielicz A, Kiec-Wilk B, Malczewska-Malec M, et al. Omega-3 fatty acid supplementation influences the whole blood transcriptome in women with obesity, associated with pro-resolving lipid mediator production. Biochim Biophys Acta. (2016) 1861:1746–55. doi: 10.1016/j.bbalip.2016.08.005

20. Morton AM, Furtado JD, Lee J, Amerine W, Davidson MH, Sacks FM. The effect of omega-3 carboxylic acids on apolipoprotein CIII–containing lipoproteins in severe hypertriglyceridemia. J Clin Lipidol. (2016) 10:1442–51.e4. doi: 10.1016/j.jacl.2016.09.005

21. Barbosa MM, de AL, Melo ALTR de, Damasceno NRT. The benefits of ω-3 supplementation depend on adiponectin basal level and adiponectin increase after the supplementation: a randomized clinical trial. Nutrition. (2017) 34:7–13. doi: 10.1016/j.nut.2016.08.010

22. Furuhashi M, Hiramitsu S, Mita T, Omori A, Fuseya T, Ishimura S, et al. Reduction of circulating FABP4 level by treatment with omega-3 fatty acid ethyl esters. Lipids Health Dis. (2016) 15:5. doi: 10.1186/s12944-016-0177-8

23. Allaire J, Couture P, Leclerc M, Charest A, Marin J, Lépine MC, et al. A randomized, crossover, head-to-head comparison of eicosapentaenoic acid and docosahexaenoic acid supplementation to reduce inflammation markers in men and women: the comparing EPA to DHA (ComparED) study. Am J Clin Nutr. (2016) 104:280–7. doi: 10.3945/ajcn.116.131896

24. Mazaherioun M, Djalali M, Koohdani F, Javanbakht MH, Zarei M, Beigy M, et al. Beneficial effects of n-3 fatty acids on cardiometabolic and inflammatory markers in type 2 diabetes mellitus: a clinical trial. Med Princ Pract. (2018) 26:535–41. doi: 10.1159/000484089

25. Hershman DL, Unger JM, Crew KD, Awad D, Dakhil SR, Gralow J, et al. Randomized multicenter placebo-controlled trial of omega-3 fatty acids for the control of aromatase inhibitor - induced musculoskeletal pain: SWOG S0927. J Clin Oncol. (2015) 33:1910–7. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2014.59.5595

26. Binia A, Vargas-Martínez C, Ancira-Moreno M, Gosoniu LM, Montoliu I, Gámez-Valdez E, et al. Improvement of cardiometabolic markers after fish oil intervention in young Mexican adults and the role of PPARα L162V and PPARγ2 P12A. J Nutr Biochem. (2017) 43:98–106. doi: 10.1016/j.jnutbio.2017.02.002

27. Zhao N, Wang L, Guo N. α-Linolenic acid increases the G0/G1 switch gene 2 mRNA expression in peripheral blood mononuclear cells from obese patients: a pilot study. Lipids Health Dis. (2016) 15:36. doi: 10.1186/s12944-016-0207-6

28. Sørensen GVB, Svensson M, Strandhave C, Schmidt EB, Jørgensen KA, Christensen JH. The effect of n-3 fatty acids on small dense low-density lipoproteins in patients with end-stage renal disease: a randomized placebo-controlled intervention study. J Ren Nutr. (2015) 25:376–80. doi: 10.1053/j.jrn.2015.01.021

29. Li YH, Yang LH, Sha KH, Liu TG, Zhang LG, Liu XX. Efficacy of poly-unsaturated fatty acid therapy on patients with nonalcoholic steatohepatitis. World J Gastroenterol. (2015) 21:7008–13. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v21.i22.7008

30. Toupchian O, Sotoudeh G, Mansoori A, Nasli-Esfahani E, Djalali M, Keshavarz SA, et al. Effects of DHA-enriched fish oil on monocyte/macrophage activation marker sCD163, asymmetric dimethyl arginine, and insulin resistance in type 2 diabetic patients. J Clin Lipidol. (2016) 10:798–807. doi: 10.1016/j.jacl.2016.02.013

31. Pacifico L, Bonci E, Di Martino M, Versacci P, Andreoli G, Silvestri LM, et al. A double-blind, placebo-controlled randomized trial to evaluate the efficacy of docosahexaenoic acid supplementation on hepatic fat and associated cardiovascular risk factors in overweight children with nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Nutr Metab Cardiovasc Dis. (2015) 25:734–41. doi: 10.1016/j.numecd.2015.04.003

32. Mansoori A, Sotoudeh G, Djalali M, Eshraghian MR, Keramatipour M, Nasli-Esfahani E, et al. Effect of DHA-rich fish oil on PPARγ target genes related to lipid metabolism in type 2 diabetes: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled clinical trial. J Clin Lipidol. (2015) 9:770–7. doi: 10.1016/j.jacl.2015.08.007

33. Tremblay AJ, Lamarche B, Hogue JC, Couture P. N-3 polyunsaturated fatty acid supplementation has no effect on postprandial triglyceride-rich lipoprotein kinetics in men with type 2 diabetes. J Diabetes Res. (2016) 2016:2909210. doi: 10.1155/2016/2909210

34. Kalil RS, Wang JH, De Boer IH, Mathew RO, Ix JH, Asif A, et al. Effect of extended-release niacin on cardiovascular events and kidney function in chronic kidney disease: a post hoc analysis of the AIM-HIGH trial. Kidney Int. (2015) 87:1250–7. doi: 10.1038/ki.2014.383

35. Croyal M, Ouguerram K, Passard M, Ferchaud-Roucher V, Chétiveaux M, Billon-Crossouard S, et al. Effects of extended-release nicotinic acid on apolipoprotein (a) kinetics in hypertriglyceridemic patients. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. (2015) 35:2042–7. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.115.305835

36. Geberemeskel GA, Debebe YG, Nguse NA. Antidiabetic effect of fenugreek seed powder solution (Trigonella Foenum-Graecum L.) on hyperlipidemia in diabetic patients. J Diabetes Res. (2019) 2019:8507453. doi: 10.1155/2019/8507453

37. Zarvandi M, Rakhshandeh H, Abazari M, Shafiee-Nick R, Ghorbani A. Safety and efficacy of a polyherbal formulation for the management of dyslipidemia and hyperglycemia in patients with advanced-stage of type-2 diabetes. Biomed Pharmacother. (2017) 89:69–75. doi: 10.1016/j.biopha.2017.02.016

38. Pal S, Ho S, Gahler RJ, Wood S. Effect on insulin, glucose and lipids in overweight/obese australian adults of 12 months consumption of two different fibre supplements in a randomised trial. Nutrients. (2017) 9:91. doi: 10.3390/nu9020091

39. Nicolucci AC, Hume MP, Martínez I, Mayengbam S, Walter J, Reimer RA. Prebiotics reduce body fat and alter intestinal microbiota in children who are overweight or with obesity. Gastroenterology. (2017) 153:711–22. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2017.05.055

40. Mohammadi-Sartang M, Bellissimo N, Totosy de Zepetne JO, Brett NR, Mazloomi SM, Fararouie M, et al. The effect of daily fortified yogurt consumption on weight loss in adults with metabolic syndrome: a 10-week randomized controlled trial. Nutr Metab Cardiovasc Dis. (2018) 28:565–74. doi: 10.1016/j.numecd.2018.03.001

41. Tessari P, Lante A. A multifunctional bread rich in beta glucans and low in starch improves metabolic control in type 2 diabetes: a controlled trial. Nutrients. (2017) 9:297. doi: 10.3390/nu9030297

42. Machado AM, da Silva NBM, Chaves JBP, de Alfenas RCG. Consumption of yacon flour improves body composition and intestinal function in overweight adults: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled clinical trial. Clin Nutr ESPEN. (2019) 29:22–9. doi: 10.1016/j.clnesp.2018.12.082

43. Babiker R, Elmusharaf K, Keogh MB, Saeed AM. Effect of gum arabic (Acacia Senegal) supplementation on visceral adiposity index (VAI) and blood pressure in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus as indicators of cardiovascular disease (CVD): a randomized and placebo-controlled clinical trial. Lipids Health Dis. (2018) 17:56. doi: 10.1186/s12944-018-0711-y

44. Gholizadeh Shamasbi S, Dehgan P, Mohammad-Alizadeh Charandabi S, Aliasgarzadeh A, Mirghafourvand M. The effect of resistant dextrin as a prebiotic on metabolic parameters and androgen level in women with polycystic ovarian syndrome: a randomized, triple-blind, controlled, clinical trial. Eur J Nutr. (2019) 58:629–40. doi: 10.1007/s00394-018-1648-7

45. Gargari BP, Namazi N, Khalili M, Sarmadi B, Jafarabadi MA, Dehghan P. Is there any place for resistant starch, as alimentary prebiotic, for patients with type 2 diabetes? Complement Ther Med. (2015) 23:810–5. doi: 10.1016/j.ctim.2015.09.005

46. Izadi A, Shirazi S, Taghizadeh S, Gargari BP. Independent and additive effects of coenzyme q10 and vitamin E on cardiometabolic outcomes and visceral adiposity in women with polycystic ovary syndrome. Arch Med Res. (2019) 50:1–10. doi: 10.1016/j.arcmed.2019.04.004

47. Eljaoudi R, Elkabbaj D, Bahadi A, Ibrahimi A, Benyahia M, Errasfa M. Consumption of argan oil improves anti-oxidant and lipid status in hemodialysis patients. Phyther Res. (2015) 29:1595–9. doi: 10.1002/ptr.5405

48. Patti AM, Al-Rasadi K, Katsiki N, Banerjee Y, Nikolic D, Vanella L, et al. Effect of a natural supplement containing curcuma longa, guggul, and chlorogenic acid in patients with metabolic syndrome. Angiology. (2015) 66:856–61. doi: 10.1177/0003319714568792

49. Capomolla AS, Janda E, Paone S, Parafati M, Sawicki T, Mollace R, et al. Atherogenic index reduction and weight loss in metabolic syndrome patients treated with a novel pectin-enriched formulation of bergamot polyphenols. Nutrients. (2019) 11:1271. doi: 10.3390/nu11061271

50. Lockyer S, Rowland I, Spencer JPE, Yaqoob P, Stonehouse W. Impact of phenolic-rich olive leaf extract on blood pressure, plasma lipids and inflammatory markers: a randomised controlled trial. Eur J Nutr. (2017) 56:1421–32. doi: 10.1007/s00394-016-1188-y

51. Rahmani S, Asgary S, Askari G, Keshvari M, Hatamipour M, Feizi A, et al. Treatment of non-alcoholic fatty liver disease with curcumin: a randomized placebo-controlled trial. Phyther Res. (2016) 30:1540–8. doi: 10.1002/ptr.5659

52. Ortiz BOM, Preciado ARF, Emiliano JR, Garza SM, Rodríguez ER, de Alba Macías LA. Recovery of bone and muscle mass in patients with chronic kidney disease and iron overload on hemodialysis and taking combined supplementation with curcumin and resveratrol. Clin Interv Aging. (2019) 14:2055–62. doi: 10.2147/CIA.S223805

53. Upadya H, Prabhu S, Prasad A, Subramanian D, Gupta S, Goel A. A randomized, double blind, placebo controlled, multicenter clinical trial to assess the efficacy and safety of Emblica officinalis extract in patients with dyslipidemia 11 medical and health sciences 1103 clinical sciences. BMC Complement Altern Med. (2019) 19:27. doi: 10.1186/s12906-019-2430-y

54. Adibian M, Hodaei H, Nikpayam O, Sohrab G, Hekmatdoost A, Hedayati M. The effects of curcumin supplementation on high-sensitivity C-reactive protein, serum adiponectin, and lipid profile in patients with type 2 diabetes: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Phyther Res. (2019) 33:1374–83. doi: 10.1002/ptr.6328

55. Quezada-Fernández P, Trujillo-Quiros J, Pascoe-González S, Trujillo-Rangel WA, Cardona-Müller D, Ramos-Becerra CG, et al. Effect of green tea extract on arterial stiffness, lipid profile and sRAGE in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus: a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Int J Food Sci Nutr. (2019) 70:977–85. doi: 10.1080/09637486.2019.1589430

56. Novotny JA, Baer DJ, Khoo C, Gebauer SK, Charron CS. Cranberry juice consumption lowers markers of cardiometabolic risk, including blood pressure and circulating c-reactive protein, triglyceride, and glucose concentrations in adults. J Nutr. (2015) 145:1185–93. doi: 10.3945/jn.114.203190

57. Zare Javid A, Hormoznejad R, Yousefimanesh H allah, Zakerkish M, Haghighi-zadeh MH, Dehghan P, et al. The impact of resveratrol supplementation on blood glucose, insulin, insulin resistance, triglyceride, and periodontal markers in type 2 diabetic patients with chronic periodontitis. Phyther Res. (2017) 31:108–14. doi: 10.1002/ptr.5737

58. Zortea K, Franco VC, Francesconi LP, Cereser KMM, Lobato MIR, Belmonte-De-Abreu PS. Resveratrol supplementation in schizophrenia patients: a randomized clinical trial evaluating serum glucose and cardiovascular risk factors. Nutrients. (2016) 8:73. doi: 10.3390/nu8020073

59. Faghihzadeh F, Adibi P, Hekmatdoost A. The effects of resveratrol supplementation on cardiovascular risk factors in patients with non-alcoholic fatty liver disease: a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled study. Br J Nutr. (2015) 114:796–803. doi: 10.1017/S0007114515002433

60. Toth PP, Patti AM, Nikolic D, Giglio RV, Castellino G, Biancucci T, et al. Bergamot reduces plasma lipids, atherogenic small dense LDL, and subclinical atherosclerosis in subjects with moderate hypercholesterolemia: a 6 months prospective study. Front Pharmacol. (2016) 6:299. doi: 10.3389/fphar.2015.00299

61. Li D, Zhang Y, Liu Y, Sun R, Xia M. Purified anthocyanin supplementation reduces dyslipidemia, enhances antioxidant capacity, and prevents insulin resistance in diabetic patients. J Nutr. (2015) 145:742–8. doi: 10.3945/jn.114.205674

62. Houten SM, Wanders RJA. A general introduction to the biochemistry of mitochondrial fatty acid β-oxidation. J Inherit Metab Dis. (2010) 33:469–77. doi: 10.1007/s10545-010-9061-2

63. Julius U. Influence of plasma free fatty acids on lipoprotein synthesis and diabetic dyslipidemia. Exp Clin Endocrinol Diabetes. (2003) 111:246–50. doi: 10.1055/s-2003-41284

64. Vega GL, Dunn FL, Grundy SM. Impaired hepatic ketogenesis in moderately obese men with hypertriglyceridemia. J Investig Med. (2009) 57:590–4. doi: 10.2310/JIM.0b013e31819e2f61

65. Lemberger T, Desvergne B, Wahli W. Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptors: a nuclear receptor signaling pathway in lipid physiology. Annu Rev Cell Dev Biol. (1996) 12:335–63. doi: 10.1146/annurev.cellbio.12.1.335

66. Bougarne N, Weyers B, Desmet SJ, Deckers J, Ray DW, Staels B, et al. Molecular actions of PPARα in lipid metabolism and inflammation. Endocr Rev. (2018) 39:760–802. doi: 10.1210/er.2018-00064

67. Kersten S, Rakhshandehroo M, Knoch B, Müller M. Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor alpha target genes. PPAR Res. (2010) 2010:612089. doi: 10.1155/2010/612089

68. Staels B, Schoonjans K, Fruchart JC, Auwerx J. The effects of fibrates and thiazolidinediones on plasma triglyceride metabolism are mediated by distinct peroxisome proliferator activated receptors (PPARs). Biochimie. (1997) 79:95–9. doi: 10.1016/S0300-9084(97)81497-6

69. Shahidi F, Ambigaipalan P. Omega-3 polyunsaturated fatty acids and their health benefits. Annu Rev Food Sci Technol. (2018) 9:345–81. doi: 10.1146/annurev-food-111317-095850

70. Jump DB, Botolin D, Wang Y, Xu J, Christian B, Demeure O. Recent advances in nutritional sciences fatty acid regulation of hepatic gene transcription. J Nutr. (2005) 135:2503–6. doi: 10.1093/jn/135.11.2503

71. Takahashi H, Kamakari K, Goto T, Hara H, Mohri S, Suzuki H, et al. 9-Oxo-10:12:15(Z)-Octadecatrienoic Acid Activates Peroxisome Proliferator-Activated Receptor α in Hepatocytes. Lipids. (2015) 50:1083–91. doi: 10.1007/s11745-015-4071-3

72. Meuronen T, Lankinen MA, Fauland A, Shimizu B ichi, de MelloMello VD, Laaksonen DE, et al. Intake of camelina sativa oil and fatty fish alter the plasma lipid mediator profile in subjects with impaired glucose metabolism – a randomized controlled trial. Prostaglandins Leukot Essent Fat Acids. (2020) 159:102143 doi: 10.1016/j.plefa.2020.102143

73. Tenore GC, Caruso D, Buonomo G, D'Avino M, Ciampaglia R, Novellino E. Plasma lipid lowering effect by a novel chia seed based nutraceutical formulation. J Funct Foods. (2018) 42:38–46. doi: 10.1016/j.jff.2018.01.007

74. Hrnčič MK, Ivanovski M, Cör D, Knez Ž. Chia Seeds (Salvia Hispanica L.): an overview-phytochemical profile, isolation methods, and application. Molecules. (2020) 25:11. doi: 10.3390/molecules25010011

75. Simopoulos AP. Evolutionary aspects of the dietary Omega-6:Omega-3 fatty acid ratio: medical implications. World Rev Nutr Diet. (2009) 100:1–21. doi: 10.1159/000235706

76. Schmitz G, Ecker J. The opposing effects of n-3 and n-6 fatty acids. Prog Lipid Res. (2008) 47:147–55. doi: 10.1016/j.plipres.2007.12.004

77. Panahi Y, Ahmadi Y, Teymouri M, Johnston TP, Sahebkar A. Curcumin as a potential candidate for treating hyperlipidemia: a review of cellular and metabolic mechanisms. J Cell Physiol. (2018) 233:141–52. doi: 10.1002/jcp.25756

78. Shin SK, Ha TY, McGregor RA, Choi MS. Long-term curcumin administration protects against atherosclerosis via hepatic regulation of lipoprotein cholesterol metabolism. Mol Nutr Food Res. (2011) 55:1829–40. doi: 10.1002/mnfr.201100440

79. Jia Y, Kim JY, Jun HJ, Kim SJ, Lee JH, Hoang MH, et al. The natural carotenoid astaxanthin, a PPAR-α agonist and PPAR-γ antagonist, reduces hepatic lipid accumulation by rewiring the transcriptome in lipid-loaded hepatocytes. Mol Nutr Food Res. (2012) 56:878–88. doi: 10.1002/mnfr.201100798

80. Lee SJ, Jia Y. The effect of bioactive compounds in tea on lipid metabolism and obesity through regulation of peroxisome proliferator-activated receptors. Curr Opin Lipidol. (2015) 26:3–9. doi: 10.1097/MOL.0000000000000145

81. Lin JK, Liang YC, Lin-Shiau SY. Cancer chemoprevention by tea polyphenols through mitotic signal transduction blockade. Biochem Pharmacol. (1999) 58:911–5. doi: 10.1016/S0006-2952(99)00112-4

82. Jun HJ, Lee JH, Kim J, Jia Y, Kim KH, Hwang KY, et al. Linalool is a PPARα ligand that reduces plasma TG levels and rewires the hepatic transcriptome and plasma metabolome. J Lipid Res. (2014) 55:1098–110. doi: 10.1194/jlr.M045807

83. Jia Y, Kim JY, Jun HJ, Kim SJ, Lee JH, Hoang MH, et al. Cyanidin is an agonistic ligand for peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-alpha reducing hepatic lipid. Biochim Biophys Acta. (2013) 1831:698–708. doi: 10.1016/j.bbalip.2012.11.012

84. Li H, Gao Z, Zhang J, Ye X, Xu A, Ye J, et al. Sodium butyrate stimulates expression of fibroblast growth factor 21 in liver by inhibition of histone deacetylase 3. Diabetes. (2012) 61:797–806. doi: 10.2337/db11-0846

85. Downing LE, Ferguson BS, Rodriguez K, Ricketts ML. A grape seed procyanidin extract inhibits HDAC activity leading to increased Pparα phosphorylation and target-gene expression. Mol Nutr Food Res. (2017) 61:85–98. doi: 10.1002/mnfr.201770021

86. Klop B, Elte JWF, Cabezas MC. Dyslipidemia in obesity: mechanisms and potential targets. Nutrients. (2013) 5:1218–40. doi: 10.3390/nu5041218

87. Bays HE. Adiposopathy: is “sick fat” a cardiovascular disease? J Am Coll Cardiol. (2011) 57:2461–73. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2011.02.038

88. Lagin D, Holm C, Lafontan M. Adipocyte hormone-sensitive lipase : a major regulator of lipid metabolism Lipase hormono-sensible de l ' adipocyte : un rCgulateur important du mCtabolisme lipidique. Proc Nutr Soc. (1996) 55:93–109. doi: 10.1079/PNS19960013

89. Salakhutdinov NF, Laev SS. Triglyceride-lowering agents. Bioorganic Med Chem. (2014) 22:3551–64. doi: 10.1016/j.bmc.2014.05.008

90. Chow DC, Tasaki A, Ono J, Shiramizu B, Souza SA. Effect of extended-release niacin on hormone-sensitive lipase and lipoprotein lipase in patients with HIV-associated lipodystrophy syndrome. Biol Targets Ther. (2008) 2:917–21. doi: 10.2147/BTT.S3959

91. Farmer JA, Gotto AM. Choosing the right lipid-regulating agent: a guide to selection. Drugs. (1996) 52:649–61. doi: 10.2165/00003495-199652050-00003

92. Reynisdottir S, Dauzats M, Thörne A, Langin D. Comparison of hormone-sensitive lipase activity in visceral and subcutaneous human adipose tissue. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. (1997) 82:4162–6. doi: 10.1210/jc.82.12.4162

93. Hardie DG, Pan DA. Regulation of fatty acid synthesis and oxidation by the AMP-activated protein kinase. Biochem Soc Trans. (2002) 30:1064–70. doi: 10.1042/bst0301064

94. Vazirian M, Nabavi SM, Jafari S, Manayi A. Natural activators of adenosine 5′-monophosphate (AMP)-activated protein kinase (AMPK) and their pharmacological activities. Food Chem Toxicol. (2018) 122:69–79. doi: 10.1016/j.fct.2018.09.079

95. Shimano H, Yahagi N, Amemiya-Kudo M, Hasty AH, Osuga JI, Tamura Y, et al. Sterol regulatory element-binding protein-1 as a key transcription factor for nutritional induction of lipogenic enzyme genes. J Biol Chem. (1999) 274:35832–9. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.50.35832

96. Xu J, Nakamura MT, Cho HP, Clarke SD. Sterol regulatory element binding protein-1 expression is suppressed by dietary polyunsaturated fatty acids. a mechanism for the coordinate suppression of lipogenic genes by polyunsaturated fats. J Biol Chem. (1999) 274:23577–83. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.33.23577

97. Tabor DE, Kim JB, Spiegelman BM, Edwards PA. Identification of conserved cis-elements and transcription factors required for sterol-regulated transcription of stearoyl-CoA desaturase 1 and 2. J Biol Chem. (1999) 274:20603–10. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.29.20603

98. Takeuchi Y, Yahagi N, Izumida Y, Nishi M, Kubota M, Teraoka Y, et al. Polyunsaturated fatty acids selectively suppress sterol regulatory element-binding protein-1 through proteolytic processing and autoloop regulatory circuit. J Biol Chem. (2010) 285:11681–91. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.096107

99. Botolin D, Wang Y, Christian B, Jump DB. Docosahexaneoic acid (22:6,n-3) regulates rat hepatocyte SREBP-1 nuclear abundance by Erk- and 26S proteasome-dependent pathways. J Lipid Res. (2006) 47:181–92. doi: 10.1194/jlr.M500365-JLR200

100. Shao W, Yu Z, Chiang Y, Yang Y, Chai T, Foltz W, et al. Curcumin prevents high fat diet induced insulin resistance and obesity via attenuating lipogenesis in liver and inflammatory pathway in adipocytes. PLoS ONE. (2012) 7:e28784. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0028784

101. Yuan HY, Kuang SY, Zheng X, Ling HY, Yang YB, Yan PK, et al. Curcumin inhibits cellular cholesterol accumulation by regulating SREBP-1/caveolin-1 signaling pathway in vascular smooth muscle cells. Acta Pharmacol Sin. (2008) 29:555–63. doi: 10.1111/j.1745-7254.2008.00783.x

102. Vijayakumar M V., Pandey V, Mishra GC, Bhat MK. Hypolipidemic effect of fenugreek seeds is mediated through inhibition of fat accumulation and upregulation of LDL receptor. Obesity. (2010) 18:667–74. doi: 10.1038/oby.2009.337

103. Watanabe M, Houten SM, Wang L, Moschetta A, Mangelsdorf DJ, Heyman RA, et al. Bile acids lower triglyceride levels via a pathway involving FXR, SHP, and SREBP-1c. J Clin Invest. (2004) 113:1408–18. doi: 10.1172/JCI21025

104. Bas JM Del, Ricketts ML, Vaqué M, Sala E, Quesada H, Ardevol A, et al. Dietary procyanidins enhance transcriptional activity of bile acid-activated FXR in vitro and reduce triglyceridemia in vivo in a FXR-dependent manner. Mol Nutr Food Res. (2009) 53:805–14. doi: 10.1002/mnfr.200800364

105. Zhao A, Yu J, Lew JL, Huang L, Wright SD, Cui J. Polyunsaturated fatty acids are FXR ligands and differentially regulate expression of FXR targets. DNA Cell Biol. (2004) 23:519–26. doi: 10.1089/1044549041562267

106. Bhatt-Wessel B, Jordan TW, Miller JH, Peng L. Role of DGAT enzymes in triacylglycerol metabolism. Arch Biochem Biophys. (2018) 655:1–11. doi: 10.1016/j.abb.2018.08.001

107. Harris WS, Bulchandani D. Why do omega-3 fatty acids lower serum triglycerides? Curr Opin Lipidol. (2006) 17:387–93. doi: 10.1097/01.mol.0000236363.63840.16

108. Ganji SH, Tavintharan S, Zhu D, Xing Y, Kamanna VS, Kashyap ML. Niacin noncompetitively inhibits DGAT2 but not DGAT1 activity in HepG2 cells. J Lipid Res. (2004) 45:1835–45. doi: 10.1194/jlr.M300403-JLR200

109. Lin X, Li BB, Zhang L, Li HZ, Meng X, Jiang YY, et al. Four new compounds isolated from Psoralea corylifolia and their diacylglycerol acyltransferase (DGAT) inhibitory activity. Fitoterapia. (2018) 128:130–4. doi: 10.1016/j.fitote.2018.05.004

110. Chung MY, Rho MC, Ko JS, Ryu SY, Jeune KH, Kim K, et al. In vitro inhibition of diacylglycerol acyltransferase by prenylflavonoids from Sophora flavescens. Planta Med. (2004) 70:258–60. doi: 10.1055/s-2004-815545

111. Choi JH, Choi JN, Lee SY, Lee SJ, Kim K, Kim YK. Inhibitory activity of diacylglycerol acyltransferase by glabrol isolated from the roots of licorice. Arch Pharm Res. (2010) 33:237–42. doi: 10.1007/s12272-010-0208-3

112. Alves-Bezerra M, Cohen DE. Triglyceride metabolism in the liver. Compr Physiol. (2018) 8:1–22. doi: 10.1002/cphy.c170012

113. Kersten S. Physiological regulation of lipoprotein lipase. Biochim Biophys Acta. (2014) 1841:919–33. doi: 10.1016/j.bbalip.2014.03.013

114. Kohan AB. Apolipoprotein C-III: a potent modulator of hypertriglyceridemia and cardiovascular disease. Curr Opin Endocrinol Diabetes Obes. (2015) 22:119–25. doi: 10.1097/MED.0000000000000136

115. Khan S, Minihane AM, Talmud PJ, Wright JW, Murphy MC, Williams CM, et al. Dietary long-chain n-3 PUFAs increase LPL gene expression in adipose tissue of subjects with an atherogenic lipoprotein phenotype. J Lipid Res. (2002) 43:979–85.

116. Chambrier C, Bastard JP, Rieusset J, Chevillotte E, Bonnefont-Rousselot D, Therond P, et al. Eicosapentaenoic acid induces mRNA expression of peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor γ. Obes Res. (2002) 10:518–25. doi: 10.1038/oby.2002.70

117. Leibowitz MD, Fiévet C, Hennuyer N, Peinado-Onsurbe J, Duez H, Berger J, et al. Activation of PPARδ alters lipid metabolism in db/db mice. FEBS Lett. (2000) 473:333–6. doi: 10.1016/S0014-5793(00)01554-4

118. Qi K, Fan C, Jiang J, Zhu H, Jiao H, Meng Q, et al. Omega-3 fatty acid containing diets decrease plasma triglyceride concentrations in mice by reducing endogenous triglyceride synthesis and enhancing the blood clearance of triglyceride-rich particles. Clin Nutr. (2008) 27:424–30. doi: 10.1016/j.clnu.2008.02.001

119. Ballantyne CM, Bays HE, Braeckman RA, Philip S, Stirtan WG, Doyle RT, et al. Icosapent ethyl (eicosapentaenoic acid ethyl ester): effects on plasma apolipoprotein C-III levels in patients from the MARINE and ANCHOR studies. J Clin Lipidol. (2016) 10:635–45.e1. doi: 10.1016/j.jacl.2016.02.008

120. Dunbar RL, Nicholls SJ, Maki KC, Roth EM, Orloff DG, Curcio D, et al. Effects of omega-3 carboxylic acids on lipoprotein particles and other cardiovascular risk markers in high-risk statin-treated patients with residual hypertriglyceridemia: a randomized, controlled, double-blind trial. Lipids Health Dis. (2015) 14:98. doi: 10.1186/s12944-015-0100-8

121. Claudel T, Inoue Y, Barbier O, Duran-Sandoval D, Kosykh V, Fruchart J, et al. Farnesoid X receptor agonists suppress hepatic apolipoprotein CIII expression. Gastroenterology. (2003) 125:544–55. doi: 10.1016/S0016-5085(03)00896-5

122. Kast HR, Nguyen CM, Sinal CJ, Jones SA, Laffitte BA, Reue K, et al. Farnesoid X-activated receptor induces apolipoprotein C-II transcription: a molecular mechanism linking plasma triglyceride levels to bile acids. Mol Endocrinol. (2001) 15:1720–8. doi: 10.1210/mend.15.10.0712

123. Sirvent A, Claudel T, Martin G, Brozek J, Kosykh V, Darteil R, et al. The farnesoid X receptor induces very low density lipoprotein receptor gene expression. FEBS Lett. (2004) 566:173–7. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2004.04.026

124. Giglio RV, Patti AM, Cicero AFG, Lippi G, Rizzo M, Toth PP, et al. Polyphenols: potential use in the prevention and treatment of cardiovascular diseases. Curr Pharm Des. (2018) 24:239–58. doi: 10.2174/1381612824666180130112652

125. Marette A, Gavino VC, Nadeau MH. Effects of dietary saturated and polyunsaturated fats on adipose tissue lipoprotein lipase activity. Nutr Res. (1990) 10:683–95. doi: 10.1016/S0271-5317(05)80514-7

126. Yang RL, Le G, Li A, Zheng J, Shi Y. Effect of antioxidant capacity on blood lipid metabolism and lipoprotein lipase activity of rats fed a high-fat diet. Nutrition. (2006) 22:1185–91. doi: 10.1016/j.nut.2006.08.018

127. Pritchard KA, Patel ST, Karpen CW, Newman HAI, Panganamala RV. Triglyceride-lowering effect of dietary vitamin E in streptozocin-induced diabetic rats. Increased lipoprotein lipase activity in livers of diabetic rats fed high dietary vitamin E. Diabetes. (1986) 35:278–81. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.35.3.278

128. Karasu Ç, Ozansoy G, Bozkurt O, Erdogan D, Ömeroglu S. Antioxidant and triglyceride-lowering effects of vitamin E associated with the prevention of abnormalities in the reactivity and morphology of aorta from streptozotocin-diabetic rats. Metabolism. (1997) 46:872–9. doi: 10.1016/S0026-0495(97)90072-X

129. Chaturvedi U, Shrivastava A, Bhadauria S, Saxena JK, Bhatia G. A mechanism-based pharmacological evaluation of efficacy of trigonella foenum graecum (fenugreek) seeds in regulation of dyslipidemia and oxidative stress in hyperlipidemic rats. J Cardiovasc Pharmacol. (2013) 61:505–12. doi: 10.1097/FJC.0b013e31828b7822

130. Perumpail B, Li A, John N, Sallam S, Shah N, Kwong W, et al. The role of vitamin E in the treatment of NAFLD. Diseases. (2018) 6:86. doi: 10.3390/diseases6040086

131. Ganji SH, Kashyap ML, Kamanna VS. Niacin inhibits fat accumulation, oxidative stress, and inflammatory cytokine IL-8 in cultured hepatocytes: impact on non-alcoholic fatty liver disease. Metabolism. (2015) 64:982–990. doi: 10.1016/j.metabol.2015.05.002

132. Ros E. Intestinal absorption of triglyceride and cholesterol. dietary and pharmacological inhibition to reduce cardiovascular risk. Atherosclerosis. (2000) 151:357–79. doi: 10.1016/S0021-9150(00)00456-1

133. Sahebkar A, Simental-Mendía LE, Reiner Ž, Kovanen PT, Simental-Mendía M, Bianconi V, et al. Effect of orlistat on plasma lipids and body weight: a systematic review and meta-analysis of 33 randomized controlled trials. Pharmacol Res. (2017) 122:53–65. doi: 10.1016/j.phrs.2017.05.022

134. Rajan L, Palaniswamy D, Mohankumar SK. Targeting obesity with plant-derived pancreatic lipase inhibitors: a comprehensive review. Pharmacol Res. (2020) 155:104681. doi: 10.1016/j.phrs.2020.104681

135. Bhutani KK, Jagtap SC, Lunagariya NA, Patel NK. Inhibitors of pancreatic lipase: state of the art and clinical perspectives. EXCLI J. (2014) 13:897–921.

136. Lairon D, Play B, Jourdheuil-Rahmani D. Digestible and indigestible carbohydrates: interactions with postprandial lipid metabolism. J Nutr Biochem. (2007) 18:217–27. doi: 10.1016/j.jnutbio.2006.08.001

137. Pasquier B, Armand M, Castelain C, Guillon F, Borel P, Lafont H, et al. Emulsification and lipolysis of triacylglycerols are altered by viscous soluble dietary fibres in acidic gastric medium in vitro. Biochem J. (1996) 314:269–75. doi: 10.1042/bj3140269

138. Ausar SF, Landa CA, Bianco ID, Castagna LF, Beltramo DM. Hydrolysis of a chitosan-induced milk aggregate by pepsin, trypsin and pancreatic lipase. Biosci Biotechnol Biochem. (2001) 65:2412–8. doi: 10.1271/bbb.65.2412

139. Patti AM, Katsiki N, Nikolic D, Al-Rasadi K, Rizzo M. Nutraceuticals in lipid-lowering treatment: a narrative review on the role of chitosan. Angiology. (2015) 66:416–21. doi: 10.1177/0003319714542999

140. Hansen WE. Effect of dietary fiber on pancreatic lipase activity in vitro. Pancreas. (1987) 2:195–8. doi: 10.1097/00006676-198703000-00012

141. Espinal-Ruiz M, Parada-Alfonso F, Restrepo-Sánchez LP, Narváez-Cuenca CE, McClements DJ. Impact of dietary fibers [methyl cellulose, chitosan, and pectin] on digestion of lipids under simulated gastrointestinal conditions. Food Funct. (2014) 5:3083–95. doi: 10.1039/C4FO00615A

142. Espinal-Ruiz M, Parada-Alfonso F, Restrepo-Sánchez LP, Narváez-Cuenca CE, McClements DJ. Interaction of a dietary fiber (pectin) with gastrointestinal components (bile salts, calcium, and lipase): a calorimetry, electrophoresis, and turbidity study. J Agric Food Chem. (2014) 62:12620–30. doi: 10.1021/jf504829h

Keywords: hypertriglyceridemia, nutraceutical, food-derived bioactive compounds, cardiovascular risk, obesity

Citation: Schiano E, Annunziata G, Ciampaglia R, Iannuzzo F, Maisto M, Tenore GC and Novellino E (2020) Bioactive Compounds for the Management of Hypertriglyceridemia: Evidence From Clinical Trials and Putative Action Targets. Front. Nutr. 7:586178. doi: 10.3389/fnut.2020.586178

Received: 22 July 2020; Accepted: 26 October 2020;

Published: 30 November 2020.

Edited by:

Marcello Iriti, University of Milan, ItalyReviewed by:

Angelo Maria Patti, University of Palermo, ItalyRobert Hegele, Western University, Canada

Copyright © 2020 Schiano, Annunziata, Ciampaglia, Iannuzzo, Maisto, Tenore and Novellino. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Gian Carlo Tenore, Z2lhbmNhcmxvLnRlbm9yZUB1bmluYS5pdA==

†These authors have contributed equally to this work and share first authorship

Elisabetta Schiano

Elisabetta Schiano Giuseppe Annunziata

Giuseppe Annunziata Roberto Ciampaglia

Roberto Ciampaglia Fortuna Iannuzzo

Fortuna Iannuzzo Ettore Novellino

Ettore Novellino