- 1Department of Nutrition, Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health, Boston, MA, United States

- 2Brigham and Women's Hospital, Boston, MA, United States

Weight stigma is a pressing issue that affects individuals across the weight distribution. The role of social media in both alleviating and exacerbating weight bias has received growing attention. On one hand, biased algorithms on social media platforms may filter out posts from individuals in stigmatized groups and concentrate exposure to content that perpetuates problematic norms about weight. Individuals may also be more likely to engage in attacks due to increased anonymity and lack of substantive consequences online. The critical influence of social media in shaping beliefs may also lead to the internalization of weight stigma. However, social media could also be used as a positive agent of change. Movements such as Body Positivity, the Fatosphere, and Health at Every Size have helped counter negative stereotypes and provide more inclusive spaces. To support these efforts, governments should continue to explore legislative solutions to enact anti-weight discrimination policies, and platforms should invest in diverse content moderation teams with dedicated weight bias training while interrogating bias in existing algorithms. Public health practitioners and clinicians should leverage social media as a tool in weight management interventions and increase awareness of stigmatizing online content among their patients. Finally, researchers must explore how experiences of stigma differ across in-person and virtual settings and critically evaluate existing research methodologies and terminology. Addressing weight stigma on social media will take a concerted effort across an expansive set of stakeholders, but the benefits to population health are consequential and well-worth our collective attention.

Introduction

The prevalence of weight discrimination has increased dramatically in the United States (US), as much as 66% between 1995 and 2006 (1), and 71% of adolescents reported being bullied about their weight in the past year (2). Weight stigma, also commonly referred to as “weight bias,” “weight discrimination,” or “weight prejudice” (3), refers to the labeling, stereotyping, separation, and discrimination of individuals, populations, and organizations on the basis of weight (2). While conversations about weight stigma have historically centered on individuals who are classified with overweight or obesity, evidence suggests that those classified as underweight also experience stigma that exacerbates poor health (4–7). Experiences of weight stigma manifest across different contexts, but there is growing recognition of the role of social media in both promoting and reducing weight stigma, especially amongst youth. The use of social media, which refers to internet-based platforms that enable people to connect virtually to share experiences, information and ideas (8), has become ubiquitous. More than 3.6 billion people are connected worldwide, and this number is projected to increase to 4.41 billion by 2025 (9). Problematic social media use has become especially concerning during the COVID-19 pandemic (10–14). Emerging research on “#quarantine15,” a hashtag on platforms including Instagram and Twitter that features stigmatizing-posts related to weight gain during the pandemic, shows that individuals may be increasingly exposed to content that emphasizes thinness as a normative ideal and perpetuates disputed notions of the self-controllability of weight (10, 14). Given the need for greater clarity and social media saturation, this review aimed to synthesize the evidence surrounding the intersections of weight stigma and social media and discuss implications for policy, industry, practitioners, and research.

Weight Stigma and Health

Understanding the mechanisms by which weight stigma inhibits health and well-being is critical to any discussion of the relationship between weight stigma and social media. These pathways are cyclical in nature, and as outlined by Tomiyama, involve the influence of weight stigma on stress, disordered eating, homeostatic imbalance, and subsequent weight change (15). First, weight stigma correlates with adverse indicators of physical health. For example, a randomized trial of US women conducted by Major et al. found that weight stigmatizing scenarios led to reduced executive functioning (16). Weight stigma has been associated with higher likelihood of developing key risk factors for chronic disease. Randomized studies of women by Himmelstein et al. and Schvey et al. found that exposure to stigmatizing statements or conditions resulted in elevated levels of cortisol (17, 18), a glucocorticoid that inhibits inflammation clearance (19) and is associated with the development of hypertension, hyperglycemia, insulin resistance, and hyperlipidemia (20). Other studies, including a 10-year longitudinal analysis of U.S. adults in the MIDUS Biomarker Substudy by Vadiveloo and Mattei, suggests that perceived weight discrimination may be associated with chronic health conditions such as allostatic load, glucose dysregulation, inflammation, atherosclerosis, diabetes, hypercholesterolemia, myocardial infarctions, and stomach ulcers (21–26). However, the causal relationships between weight stigma and distal health outcomes remain unresolved.

Weight stigma may also drive adverse psychosocial health outcomes, such as anxiety, depression, body image dissatisfaction, and negative self-esteem (20). Using a structural equation mediation modeling approach with a diverse sample of US adults, Himmelstein et al. found that perceived weight stigma was related to intermediary outcomes such as exercise avoidance, maladaptive eating, lifestyle behaviors, and negative affect, which in turn were associated with depressive symptoms, poorer physical health, and higher frequency of dieting. (27). A recent meta-analysis of 22 studies across various countries by Zhang et al. found an adverse relationship between use of social networking sites and disordered eating behaviors (28). For example, individuals exposed to weight-related stigma in experimental settings have been shown to have increased ad libitum total energy intake (29–31), to be more likely to binge eat and less likely to adhere to weight loss treatments (32, 33), and to be less likely to engage in physical activity (31, 34–39).

These relationships seem to hold true across genders (40), but heterogeneity by race/ethnicity exists. While weight stigma is similarly prevalent across different racial/ethnic groups, Black men and women report lower weight bias internalization compared to White men and women. However, a cross-sectional analysis of US adults found that Black men and Hispanic women were more likely to cope with stigma by disordered eating relative to White men and women, suggestive of distinct internalizing mechanisms and social norms across racial/ethnic groups (41). Weight stigma also varies across the life course. For example, pregnant women classified with higher body mass index (BMI) are more likely to report stigmatizing interactions with their providers and lower satisfaction with care (42), which in turn may prevent them from seeking additional health care resources (43). In addition, the high prevalence of weight stigma among youth is well-documented, and evidence suggests that children who experience weight-based teasing or bullying are more likely to binge eat or decrease levels of physical activity, and are at higher risk of developing obesity or overweight in adolescence (2). This intersectionality complicates our conceptualization of weight stigma and highlights the need for high-quality studies that assess the effects of weight stigma in diverse populations, as well as the different ways in which social media use may mediate this relationship (44). Because social media use is becoming increasingly accessible as technologies become less expensive to produce and purchase, interventions that aim to improve population health by addressing weight stigma exposure on social media may be cost-effective and wide-reaching.

Influence of Social Media on Weight Attitudes and Stigma

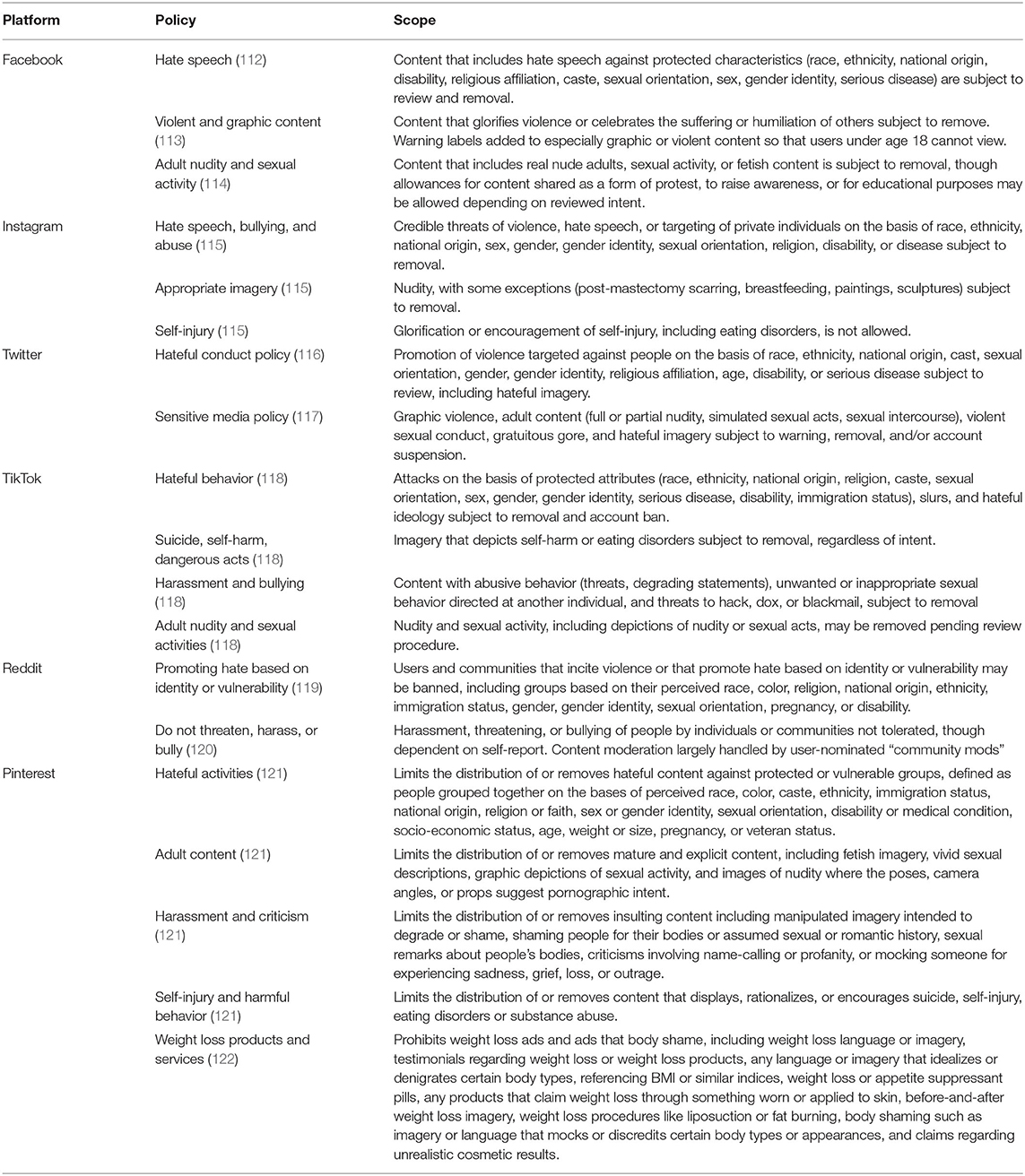

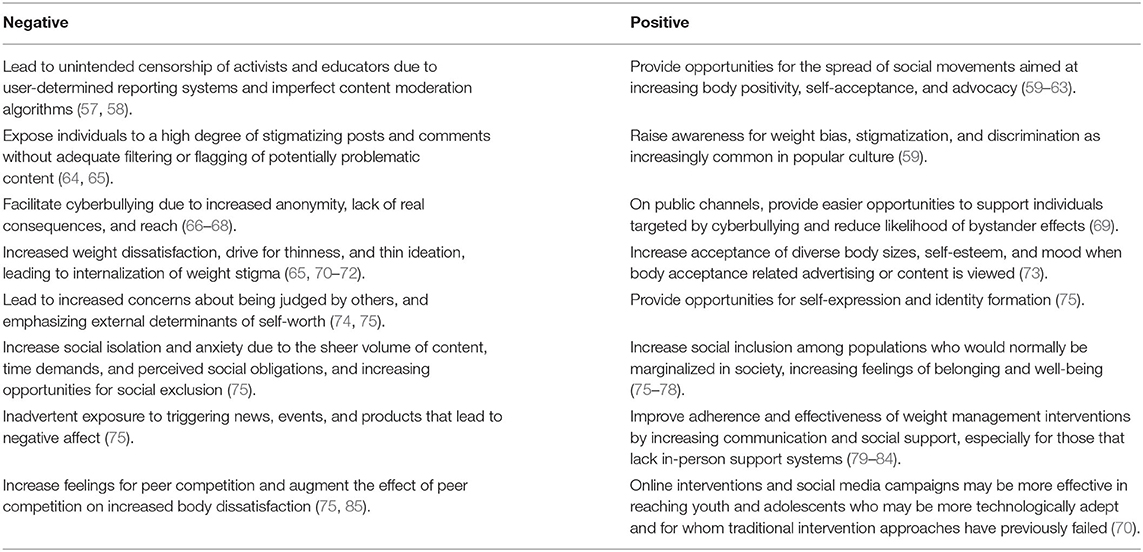

Social media, such as Instagram, Facebook, or Twitter, refers to online, virtual-based platforms that allow individuals to connect and share content, either in private or public capacities (8). Due to its widespread use and theoretical ability to connect individuals across different experiences and perspectives, social media has a potentially prominent role in both exacerbating and lessening weight stigma. The utility of social media and networks as a valuable tool in shaping health attitudes and behaviors is well-established, particularly in the case of adolescent smoking. The “truth” campaign, which uses a counter-marketing strategy to reduce initiation and improve cessation of youth smoking by counteracting tobacco advertising seen by adolescents on digital media, has organized initiatives on TikTok (45), Vine (46), Facebook (47), Instagram (48), Twitter (49), and LinkedIn (50), and has shown to be effective in increasing awareness for and shifting youth attitudes against tobacco and tobacco companies (51–56). Similarly, social media may have both negative and positive influences on weight stigma (Table 1).

Table 1. Summary of the positive and negative influences of social media on weight stigma and body shape perceptions.

Negative Influences of Social Media

Using ecological theory, weight stigma can be characterized into three distinct subtypes: structural, interpersonal, and intrapersonal (3). Negative influences of social media may manifest across each of these levels and ultimately contribute to poor health. Structural weight stigma describes weight discrimination and negative beliefs encoded into societal systems such as medical institutions and consumed media. On social media, structural weight bias may lead to unintended algorithmic or policy decisions that filter out or flag content from individuals in stigmatized weight classes. For example, some have speculated that an algorithm designed to censor inappropriate images on Instagram, a platform now owned by Facebook which itself has recently been publicly criticized for censorship and misinformation concerns (86), has led to posts by larger-bodied “influencers” being disproportionately targeted for removal and to the selective filtering of content shown to users of a platform that may reflect normative ideals of weight (57, 58). These algorithms might have a “silo-ing” effect for consumers that leads to repeated exposure to stigmatizing content and reinforces harmful norms about weight (70). Because these algorithms are proprietary and their mechanisms opaque, research on structural forms of weight stigma on social media is largely absent.

Interpersonal experiences of stigma derive from person-to-person interactions. This may be especially problematic in virtual settings where a higher degree of anonymity can reduce the influence of normative beliefs and subjective norms in an individuals' decision to engage in cyberbullying (66–68). For example, Jeon et al. found that attacks on individuals classified as overweight were twice as frequent as comments in their defense on YouTube (64). A content analysis by Chou et al. of 1.37 million posts from major social media sites and their respective comments found that 92% of posts related to obesity used the term “fat,” and that these posts were more often associated with negative, derogatory, and misogynist connotations (65). In addition, the authors found that the large majority (91.5%) of all obesity-related interactions occurred on Twitter (65). These negative weight-based aggressive comments have feedback effects (15), resulting in greater risk of depression and anxiety in individuals classified as overweight. For example, a cross-sectional analysis of adults with obesity in the US by Friedman et al. found that higher frequency of interpersonal stigmatizing experiences was correlated with more severe phobic anxiety as assessed by the Symptoms Checklist-90-R (SCL-90-R) and higher Beck Depression Inventory scores (87).

Last, intrapersonal weight stigma refers to the internalization and embodiment of weight bias into an individual's beliefs and perceptions about their abilities and intrinsic worth. Social media plays a key role in social, cultural, and political identity construction (88, 89), such that individuals may develop weight-related attitudes and beliefs that reflect their differential exposure to stigmatizing or non-stigmatizing online content. For example, social media may spread information that focuses on behavioral or lifestyle determinants (e.g., diet or physical activity) of weight change, rather than on more upstream environmental or social factors such as obesogenic neighborhood retail or food environments. In addition, social media may serve to augment existing norms on thinness and body image that are driven by peer comparison and competition. In an analysis of 237 pre-adolescent and adolescent girls, Ferguson et al. found that social media use at baseline was positively correlated with greater feelings of peer competition, which were in turn positively correlated with body dissatisfaction and eating disorder symptoms at follow up (85). In a content analysis of nearly a thousand tweets following a major fashion show, Chrisler et al. found that users of social media platforms frequently engaged in upwards social comparisons to models and expressed sentiments related to body dissatisfaction, disordered eating, and self-harm (90). Social comparison may also occur among peers on social media. For example, Fardouly et al. found that the frequency of comparison to peers on Facebook mediated the positive association between Facebook usage and body image concerns (91).

Food industry and lifestyle groups are also more likely to promote purchasable items on Facebook and Instagram, and health promotion organizations are more likely to feature information about fruits, vegetables, and grains (92). While each entity may have different motives, the key assumption behind the types of messages users may see on social media is that the locus of responsibility is centrally on the individual, rather than on corporations, governments, or society. As a result, people living in large bodies may be implicitly or explicitly portrayed in stigmatizing ways as unintelligent or undisciplined (65, 71). Messaging on social media may promote individual blame beliefs, leading to negative self-perception and internalization of stigma in individuals with underweight, overweight, or obesity classifications and increase the likelihood of maladaptive coping behaviors that may persist over time (73). Exposure to “thin-ideal” images and advertising are also prevalent across different forms of media. In a randomized study of 475 female students over 18 years of age in the United States, Selensky and Carels found that exposure to thin-idealizing advertising resulted in greater dislike of persons with overweight and obesity and lower self-satisfaction of body shape or weight (73). In another randomized study of college-age women enrolled in classes at Utah State University by Hawkins et al., exposure to thin-ideal magazines elicited higher body dissatisfaction, negative affect, eating disorder symptoms, and decreased self-esteem (72).

Positive Influences of Social Media

While social media may exacerbate experiences of stigma, it may also serve to provide a space to build solidarity, reduce social isolation, and increase awareness of weight bias. The Body Positivity (BoPo) movement is a prominent social movement to reduce weight bias on social media, which, while largely decentralized, has been heralded by some influential personas (59). BoPo, which has roots in the 1960s feminist fat-acceptance movements in the US, aims to challenge and subvert traditional ideals about beauty by promoting body appreciation, acceptance, and self-empowerment (60–63). Unsurprisingly, the BoPo movement has predominantly focused on social media sites that feature images. Viewing BoPo content is associated with lower negative affect and higher positive affect and body satisfaction among college students, while exposure to “thinspiration” content that emphasizes thin-ideals is associated with lower body satisfaction, higher negative affect, and lower positive affect (60). In experimental settings, randomized exposure to body positive photos, quotes, and no-makeup selfies has been shown to result in better mood and self-perception with larger benefits seen among participants with disordered eating symptoms or low self-compassion (93, 94). For example, an experimental study conducted by Cohen et al. found that women who were randomized to view body-positive Instagram posts were more likely to express positive mood, body satisfaction, and body appreciation, relative to those who were randomized to view thin-idealizing or neutral content (95). However, some have raised concerns on whether the BoPo movement may inadvertently perpetuate evaluations of self-worth that are dependent on appearance, pointing to the commodification and co-opting of the movement by large corporations that use the platform to promote the sale of their products (74, 96–99), and have instead proposed a “radical body positive” that seeks to critique how we are expected to understand and inhabit our bodies in the first place (74).

A second typology of movements on social media that aims to address weight stigma involves reclamation of the term “fat” in order to challenge traditional connotations of the word. For example, “Notes from the Fatosphere (i.e., Fatosphere),” an online community where individuals who self-identify as “fat” share their experiences and promote health without a focus on weight loss, has shown to foster a sense of inclusion, empowerment, and well-being, and to help individuals better cope with stigmatizing situations (76, 77). The “Health at Every Size (HAES)” movement, present on Instagram and TikTok, also encourages a weight-neutral approach to health and aims to promote self-acceptance across a diversity of body sizes, though content analyses suggest that posts using the hashtag may still contain stigmatizing sentiments (100). Clearly, social media has the potential to positively impact behaviors and attitudes, and researchers will need to continue to evaluate the influence of structure and content in real-world applied settings to assess the most effective type of messaging. These efforts may be simultaneously supported by policies and programs implemented by social media platforms and governments that reduce the accessibility of stigmatizing content.

Implications for Policy and Industry Practice

Public Policies and Programs

Because of the demonstrated detrimental effects of weight stigma on individuals' nutritional habits and physical and mental well-being, social media public policy development should be a central concern and advocacy focus for companies, public health professionals, parents, educators, and policymakers. The vast reach of social media globally and the prevalence of use among teens and young adults (101) suggest that problematic social media use is both a concern and a potential area for intervention. However, only a few states, such as Massachusetts (102), have proposed legislation that would codify weight-based discrimination as illegal. Michigan is the only example where such policy has been passed into law (103). While potential laws prohibiting weight discrimination in the US have widespread public support (104–106), it remains unknown how such a policy would regulate social media platforms and their users. Given apparent political difficulties in successfully legislating to regulate weight-based discrimination, industry self-regulation and accountability can be key intermediate alternatives to protect vulnerable populations. Potential options for industry self-regulation are discussed below.

Industry Practices

The majority of comments directed toward individuals living in larger bodies on social media express negative sentiment (107), which can drown out positive health messages from public health officials and institutions as well as undermine individuals who seek social support via social media in their efforts to lose weight and/or adopt healthier lifestyles. Big Tech has come under criticism recently for its failure to limit the spread of misinformation (108), hate speech (109), and racial bias (110), as well as for its active role in suppressing content from users deemed physically unattractive, lower income, or disabled in the case of TikTok (111). Anti-weight bias advocates can capitalize on this momentum to reform how companies operate. First, weight bias and discrimination must be included in the articulated community guidelines outlined by social media platforms. While most platforms have policies that flag or prohibit posts that include potentially harmful or offensive content (Table 2) such as violence, suicide, bullying, eating disorders, misinformation, or hate speech (112, 116, 123), enforcement is especially absent on newer platforms (124). Recently, however, Pinterest has proposed policies that limits forms of bias, shame or discrimination based on individuals' body size or weight in content, as well as those that prohibit the advertisement of weight loss products, their testimonials, and the use of language idealizing certain body types (121, 122, 125). Meanwhile, Facebook's policy on hate speech covers content related to race, gender, sexual orientation, religious affiliation, and disease/disability, not weight stigma or body image bias (112). Pinterest's new policies ought to act as a model for change, motivating other social media companies to re-invest in developing robust content moderation teams that feature diverse experiences and backgrounds with adequate training in identifying weight stigmatizing content. Similar training is already available for medical professionals (126, 127), and even modest interventions have been shown to improve beliefs about individuals classified with obesity or overweight (128). Last, training data for machine learning algorithms that are used to identify potentially discriminatory content should include labels for weight stigmatizing material. For example, the algorithm could help prevent offensive comments and posts before they are posted by showing users prompts suggesting their comment might be harmful to others and asking if they would like to rephrase (112, 129, 130). Recent analyses of innovative hate speech detection algorithms have shown promise in identifying and reducing racial bias, and similar strategies could be applied for weight (131). Together, these technologies could be leveraged to prevent weight stigma by identifying words and word combinations (e.g., “fat” and “lazy” in the same comment) associated with fat-shaming and weight stigmatization through a process of algorithmic detection, human review, and subsequent removal.

Implications for Practitioners and Researchers

Implications for Public Health Practitioners and Clinicians

Public health practitioners and clinicians must grapple with the tension between promoting body positivity while helping patients understand that behaviors associated with an unhealthy body mass are strong risk factors for morbidity and mortality. This is especially crucial given the pervasiveness of weight bias among medical students (132) and medical professionals, even those who specialize in treating individuals with obesity (133). Therefore, practitioners and clinicians have a pivotal role in encouraging healthy (both physical and psychological) weight maintenance. Some evidence suggests that leveraging the social network basis of many social media sites including Facebook or Instagram can augment and support healthy weight interventions. For example, Facebook based peer-group interventions have been shown to be effective in improving feeding practices among families with infants at high risk for developing obesity (79), and in improving parent engagement in a preschool obesity prevention curriculum among households participating in Head Start (80). Clinicians or counselors, who may actively monitor or even lead these interactions on social media (81), should receive training in weight bias and ensure that instances of weight stigmatization are absent. As a general practice, clinicians should aim to increase patient awareness of the pervasiveness of weight stigma on social media so that individuals can identify problematic ideals and content themselves. Mental health clinicians should also receive the appropriate resources and training to recognize sources of weight stigmatization, both in their own use of language as well as in their patients' experiences, that may contribute to mental health diagnoses, especially given the role of social media in identity formation.

Implications for Research

Measurement of individuals' exposure to stigmatizing situations has typically ignored differences by online vs. in-person settings. For example, the commonly used Myers and Rosen Stigmatizing Situations Inventory includes assessment of weight-related stigma in public spaces, in medical settings, at school, at work, and at home (134, 135). Because digital interactions are increasingly common (136), and because online social interactions may be distinctly different than in-person social interactions due to increased anonymity, non-verbal cues, and the ability to easily connect across physical geographies (137–139), research that relies on participant questionnaire data should consider developing and implementing measures that assess exposure to weight stigma on social media specifically.

A recent joint international consensus statement on ending weight stigma, published by a panel of 36 experts across diverse disciplines and institutions, emphasized the need for academic institutions, professional organizations, the media, public health authorities, and governments to receive education on weight stigma consistent with current scientific knowledge (140). A natural extension, and one that has received little attention in the literature, is an evaluation of the ways in which research methods themselves might expose participants to stigmatizing scenarios. A survey of forty questionnaires and scales used in weight stigma research by Lacroix et al. found that only one used people-first language, and measures evaluating weight bias internalization frequently included terms such as “my weight,” “my weight problems” or “being overweight” (3). In solidarity with critiques of racism, ableism, sexism, and genderism in research (141–145), investigators should evaluate how weight terminology in their work and methods implicitly stigmatizes participants and alters responses. Doing so acknowledges the presence of weight stigma in other facets of life, including on social media, while attempting to minimize any additional burden to populations participating in scientific studies.

Conclusion

Weight stigma describes an unfounded societal value placed on individuals based on appearance and anthropometry. It can be detrimental to one's physical and psychological health. Social media serves as both a platform fostering weight stigma and body shaming, as well as a safe haven for communities to find support and body positivity promotion. While policies are in place to mediate harmful dialogue on these various platforms, there remains opportunity for improved sensitivity within nutrition communications and within the medical field alike. The health impact of imposed weight stigma on social media is of increasing public health concern and warrants further research and action.

Author Contributions

OC and ML conceptualized the topic, researched and analyzed the background literature, and wrote the manuscript, including interpretations. MLJ, EO'D, and YY researched and analyzed the background literature and wrote portions of the manuscript, including interpretations. AM, MT, SB, and JM provided substantial scholarly guidance on the conception of the topic, manuscript draft and interpretation, and revised the manuscript critically for intellectual content. All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher's Note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Acknowledgments

The authors appreciate the comments and feedback from our colleagues from the 2020 Introduction to Nutrition in Public Health course at Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health. JM is a faculty member of the Strategic Training Initiative for the Prevention of Eating Disorders (STRIPED) at the Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health and Boston Children's Hospital.

References

1. Puhl RM, Heuer CA. The stigma of obesity: a review and update. Obesity. (2009) 17:941–64. doi: 10.1038/oby.2008.636

2. Pont SJ, Puhl R, Cook SR, Slusser W, Obesity SO, Society TO. Stigma experienced by children and adolescents with obesity. Pediatrics. (2017) 140:e20173034. doi: 10.1542/peds.2017-3034

3. Lacroix E, Alberga A, Russell-Mathew S, McLaren L, von Ranson K. Weight bias: a systematic review of characteristics and psychometric properties of self-report questionnaires. Obes Facts. (2017) 10:223–37. doi: 10.1159/000475716

4. Health TLP. Addressing weight stigma. Lancet Public Health. (2019) 4:e168. doi: 10.1016/S2468-2667(19)30045-3

5. Davies A, Burnette CB, Mazzeo SE. Real women have (just the right) curves: investigating anti-thin bias in college women. Eat Weight Disord. (2020) 25:1711–8. doi: 10.1007/s40519-019-00812-7

6. Himmelstein MS, Puhl RM, Quinn DM. Weight stigma in men: what, when, and by whom? Obesity. (2018) 26:968–76. doi: 10.1002/oby.22162

7. Sikorski C, Spahlholz J, Hartlev M, Riedel-Heller SG. Weight-based discrimination: an ubiquitary phenomenon? Int J Obesity. (2016) 40:333–7. doi: 10.1038/ijo.2015.165

8. Ventola CL. Social media and health care professionals: benefits, risks, and best practices. P T. (2014) 39:491–520.

9. Clement J. Number of Social Media Users Worldwide 2010-2021. Statistica (2020). Available online at: https://www.statista.com/statistics/278414/number-of-worldwide-social-network-users/ (accessed June 15, 2021).

10. Pearl RL. Weight stigma and the “Quarantine-15.” Obesity. (2020) 28:1180–1. doi: 10.1002/oby.22850

11. Fung XCC, Siu AMH, Potenza MN, O'Brien KS, Latner JD, Chen C-Y, et al. Problematic use of internet-related activities and perceived weight stigma in schoolchildren: a longitudinal study across different epidemic periods of COVID-19 in China. Front Psychiatry. (2021) 12:675839. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2021.675839

12. Chen C-Y, Chen I-H, O'Brien KS, Latner JD, Lin C-Y. Psychological distress and internet-related behaviors between schoolchildren with and without overweight during the COVID-19 outbreak. Int J Obes. (2021) 45:677–86. doi: 10.1038/s41366-021-00741-5

13. Puhl RM, Lessard LM, Larson N, Eisenberg ME, Neumark-Stzainer D. Weight stigma as a predictor of distress and maladaptive eating behaviors during COVID-19: longitudinal findings from the EAT study. Ann Behav Med. (2020) 54:738–46. doi: 10.1093/abm/kaaa077

14. Lucibello KM, Vani MF, Koulanova A, deJonge ML, Ashdown-Franks G, Sabiston CM. #quarantine15: a content analysis of Instagram posts during COVID-19. Body Image. (2021) 38:148–56. doi: 10.1016/j.bodyim.2021.04.002

15. Tomiyama AJ. Weight stigma is stressful. A review of evidence for the Cyclic Obesity/Weight-Based Stigma model. Appetite. (2014) 82:8–15. doi: 10.1016/j.appet.2014.06.108

16. Major B, Eliezer D, Rieck H. The psychological weight of weight stigma. Soc Psychol Pers Sci. (2012) 3:651–8. doi: 10.1177/1948550611434400

17. Schvey NA, Puhl RM, Brownell KD. The Stress of stigma: exploring the effect of weight stigma on cortisol reactivity. Psychosom Med. (2014) 76:156–62. doi: 10.1097/PSY.0000000000000031

18. Himmelstein MS, Belsky ACI, Tomiyama AJ. The weight of stigma: cortisol reactivity to manipulated weight stigma. Obesity. (2015) 23:368–74. doi: 10.1002/oby.20959

19. Nijm J, Jonasson L. Inflammation and cortisol response in coronary artery disease. Ann Med. (2009) 41:224–33. doi: 10.1080/07853890802508934

20. Wu Y-K, Berry DC. Impact of weight stigma on physiological and psychological health outcomes for overweight and obese adults: a systematic review. J Adv Nurs. (2018) 74:1030–42. doi: 10.1111/jan.13511

21. Braveman P, Egerter S, Williams DR. The social determinants of health: coming of age. Annu Rev Public Health. (2011) 32:381–98. doi: 10.1146/annurev-publhealth-031210-101218

22. Walker BR. Glucocorticoids and cardiovascular disease. Eur J Endocrinol. (2007) 157:545–59. doi: 10.1530/EJE-07-0455

23. McEwen CA, McEwen BS. Social structure, adversity, toxic stress, and intergenerational poverty: an early childhood model. Annu Rev Sociol. (2017) 43:445–72. doi: 10.1146/annurev-soc-060116-053252

24. Alberga AS, McLaren L, Russell-Mayhew S, von Ranson KM. Canadian senate report on obesity: focusing on individual behaviours versus social determinants of health may promote weight stigma. J Obes. (2018) 2018:e8645694. doi: 10.1155/2018/8645694

25. Udo T, Purcell K, Grilo CM. Perceived weight discrimination and chronic medical conditions in adults with overweight and obesity. Int J Clin Pract. (2016) 70:1003–11. doi: 10.1111/ijcp.12902

26. Vadiveloo M, Mattei J. Perceived weight discrimination and 10-year risk of allostatic load among US adults. Ann Behav Med. (2017) 51:94–104. doi: 10.1007/s12160-016-9831-7

27. Himmelstein MS, Puhl RM, Quinn DM. Weight stigma and health: the mediating role of coping responses. Health Psychol. (2018) 37:139–47. doi: 10.1037/hea0000575

28. Zhang J, Wang YH, Li Q, Wu C. The relationship between SNSs usage and disordered eating behaviors: a meta-analysis. Front Psychol. (2021) 12:641919. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2021.641919

29. Major B, Hunger JM, Bunyan DP, Miller CT. The ironic effects of weight stigma. J Exp Soc Psychol. (2014) 51:74–80. doi: 10.1016/j.jesp.2013.11.009

30. Schvey NA, Puhl RM, Brownell KD. The impact of weight stigma on caloric consumption. Obesity. (2011) 19:1957–62. doi: 10.1038/oby.2011.204

31. Vartanian LR, Novak SA. Internalized societal attitudes moderate the impact of weight stigma on avoidance of exercise. Obesity. (2011) 19:757–62. doi: 10.1038/oby.2010.234

32. Wott CB, Carels RA. Overt weight stigma, psychological distress and weight loss treatment outcomes. J Health Psychol. (2010) 15:608–14. doi: 10.1177/1359105309355339

33. Papadopoulos S, Brennan L. Correlates of weight stigma in adults with overweight and obesity: a systematic literature review. Obesity. (2015) 23:1743–60. doi: 10.1002/oby.21187

34. Puhl R, Latner J. Stigma, obesity, and the health of the nation's children. Psychol Bull. (2007) 133:557–80. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.133.4.557

35. Puhl R, Suh Y. Health consequences of weight stigma: implications for obesity prevention and treatment. Curr Obes Rep. (2015) 4:182–90. doi: 10.1007/s13679-015-0153-z

36. O'Brien KS, Latner JD, Puhl RM, Vartanian LR, Giles C, Griva K, et al. The relationship between weight stigma and eating behavior is explained by weight bias internalization and psychological distress. Appetite. (2016) 102:70–6. doi: 10.1016/j.appet.2016.02.032

37. Puhl RM, Moss-Racusin CA, Schwartz MB. Internalization of weight bias: implications for binge eating and emotional well-being. Obesity. (2007) 15:19–23. doi: 10.1038/oby.2007.521

38. Friedman KE, Reichmann SK, Costanzo PR, Zelli A, Ashmore JA, Musante GJ. Weight stigmatization and ideological beliefs: relation to psychological functioning in obese adults. Obes Res. (2005) 13:907–16. doi: 10.1038/oby.2005.105

39. Ashmore JA, Friedman KE, Reichmann SK, Musante GJ. Weight-based stigmatization, psychological distress, & binge eating behavior among obese treatment-seeking adults. Eating Behav. (2008) 9:203–9. doi: 10.1016/j.eatbeh.2007.09.006

40. Himmelstein MS, Puhl RM, Quinn DM. Overlooked and understudied: health consequences of weight stigma in men. Obesity. (2019) 27:1598–605. doi: 10.1002/oby.22599

41. Himmelstein MS, Puhl RM, Quinn DM. Intersectionality: an understudied framework for addressing weight stigma. Am J Prev Med. (2017) 53:421–31. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2017.04.003

42. Mulherin K, Miller YD, Barlow FK, Diedrichs PC, Thompson R. Weight stigma in maternity care: women's experiences and care providers' attitudes. BMC Preg Childb. (2013) 13:19. doi: 10.1186/1471-2393-13-19

43. Incollingo Rodriguez AC, Smieszek SM, Nippert KE, Tomiyama AJ. Pregnant and postpartum women's experiences of weight stigma in healthcare. BMC Preg Childb. (2020) 20:499. doi: 10.1186/s12884-020-03202-5

44. Reece RL. Coloring weight stigma: on race, colorism, weight stigma, and the failure of additive intersectionality. Sociol Race Ethnicity. (2019) 5:388–400. doi: 10.1177/2332649218795185

45. Truth Initiative. New TikTok Challenge Kicks Off National Truth® Campaign. Truth Initiative (2020). Available online at: https://truthinitiative.org/press/press-release/new-tiktok-challenge-kicks-national-truthr-campaign-underscoring-young-peoples (accessed June 16, 2021).

46. Truth Initiative. Vine Stars Debunk Social Smoking Myths With Truth. Truth Initiative (2015). Available online at: https://truthinitiative.org/press/press-release/vine-stars-debunk-social-smoking-myths-truth (accessed June 16, 2021).

47. Truth Initiative. Truth Initiative. Facebook. Available online at: https://www.facebook.com/truthinitiative/ (accessed June 16, 2021).

48. Truth Initiative. Truth Initiative. Instagram. Available online at: https://www.instagram.com/truthinitiative/ (accessed June 16, 2021).

49. Truth Initiative. Truth Initiative. Twitter. Available online at: https://twitter.com/truthinitiative (accessed June 16, 2021).

50. Truth Initiative. Truth Initative. LinkedIn. Available online at: https://www.linkedin.com/company/truth-initiative/ (accessed June 16, 2021).

51. Hershey JC, Niederdeppe J, Evans WD, Nonnemaker J, Blahut S, Holden D, et al. The theory of “truth”: how counterindustry campaigns affect smoking behavior among teens. Health Psychol. (2005) 24:22–31. doi: 10.1037/0278-6133.24.1.22

52. Hair EC, Niederdeppe J, Rath JM, Bennett M, Romberg A, Pitzer L, et al. Using aggregate temporal variation in ad awareness to assess the effects of the truth® campaign on youth and young adult smoking behavior. J Health Commun. (2020) 25:223–31. doi: 10.1080/10810730.2020.1733144

53. Evans WD, Rath JM, Hair EC, Snider JW, Pitzer L, Greenberg M, et al. Effects of the truth FinishIt brand on tobacco outcomes. Prev Med Rep. (2018) 9:6–11. doi: 10.1016/j.pmedr.2017.11.008

54. Farrelly MC, Healton CG, Davis KC, Messeri P, Hersey JC, Haviland ML. Getting to the truth: evaluating national tobacco countermarketing campaigns. Am J Public Health. (2002) 92:901–7. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.92.6.901

55. Hair E, Pitzer L, Bennett M, Halenar M, Rath J, Cantrell J, et al. Harnessing youth and young adult culture: improving the reach and engagement of the truth® campaign. J Health Commun. (2017) 22:568–75. doi: 10.1080/10810730.2017.1325420

56. Vallone D, Greenberg M, Xiao H, Bennett M, Cantrell J, Rath J, et al. The effect of branding to promote healthy behavior: reducing tobacco use among youth and young adults. IJERPH. (2017) 14:1517. doi: 10.3390/ijerph14121517

57. Jennings R. Can Social Media Ever be Truly “Body Positive”? Vox (2021). Available online at: https://www.vox.com/the-goods/22226997/body-positivity-instagram-tiktok-fatphobia-social-media (accessed June 15, 2021).

58. Richman J. This Is the Impact of Instagram's Accidental Fat-Phobic Algorithm. Fast Company (2019). Available online at: https://www.fastcompany.com/90415917/this-is-the-impact-of-instagrams-accidental-fat-phobic-algorithm (accessed June 15, 2021).

59. Freed A. Body Image Through the Platform of Lizzo: Looking Through the Lens of Social Media and Influencers. Media and Communication Studies Presentations (2021). Available online at: https://digitalcommons.ursinus.edu/media_com_pres/18 (accessed June 16, 2021).

60. Stevens A, Griffiths S. Body positivity (#BoPo) in everyday life: an ecological momentary assessment study showing potential benefits to individuals' body image and emotional wellbeing. Body Image. (2020) 35:181–91. doi: 10.1016/j.bodyim.2020.09.003

61. Cohen R, Newton-John T, Slater A. The case for body positivity on social media: perspectives on current advances and future directions. J Health Psychol. (2020) 1359105320912450. doi: 10.1177/1359105320912450

62. Kelly L, Daneshjoo S. 263. Instagram & body positivity among female adolescents & young adults. J Adolesc Health. (2019) 64:S134–5. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2018.10.280

63. Cohen R, Irwin L, Newton-John T, Slater A. #bodypositivity: a content analysis of body positive accounts on Instagram. Body Image. (2019) 29:47–57. doi: 10.1016/j.bodyim.2019.02.007

64. Jeon YA, Hale B, Knackmuhs E, Mackert M. Weight stigma goes viral on the internet: systematic assessment of youtube comments attacking overweight men and women. Interact J Med Res. (2018) 7:e9182. doi: 10.2196/ijmr.9182

65. Chou W-YS, Prestin A, Kunath S. Obesity in social media: a mixed methods analysis. Transl Behav Med. (2014) 4:314–23. doi: 10.1007/s13142-014-0256-1

66. Peebles E. Cyberbullying: hiding behind the screen. Paediatr Child Health. (2014) 19:527–8. doi: 10.1093/pch/19.10.527

68. Ajzen I. The theory of planned behavior. Organiz Behav Hum Decis Process. (1991) 50:179–211. doi: 10.1016/0749-5978(91)90020-T

69. Anderson J, Bresnahan M, Musatics C. Combating weight-based cyberbullying on Facebook with the dissenter effect. Cyberpsychol Behav Soc Netw. (2014) 17:281–6. doi: 10.1089/cyber.2013.0370

70. Perloff RM. Social media effects on young women's body image concerns: theoretical perspectives and an agenda for research. Sex Roles. (2014) 71:363–77. doi: 10.1007/s11199-014-0384-6

71. Ata RN, Thompson JK. Weight bias in the media: a review of recent research. Obes Facts. (2010) 3:41–6. doi: 10.1159/000276547

72. Hawkins N, Richards PS, Granley HM, Stein DM. The impact of exposure to the thin-ideal media image on women. Eat Disord. (2004) 12:35–50. doi: 10.1080/10640260490267751

73. Selensky JC, Carels RA. Weight stigma and media: an examination of the effect of advertising campaigns on weight bias, internalized weight bias, self-esteem, body image, and affect. Body Image. (2021) 36:95–106. doi: 10.1016/j.bodyim.2020.10.008

74. Sastre A. Towards a radical body positive. Feminist Media Stud. (2014) 14:929–43. doi: 10.1080/14680777.2014.883420

75. Weinstein E. The social media see-saw: positive and negative influences on adolescents' affective well-being. New Media Soc. (2018) 20:3597–623. doi: 10.1177/1461444818755634

76. Dickins M, Thomas SL, King B, Lewis S, Holland K. The role of the fatosphere in fat adults' responses to obesity stigma: a model of empowerment without a focus on weight loss. Qual Health Res. (2011) 21:1679–91. doi: 10.1177/1049732311417728

77. Dickins M, Browning C, Feldman S, Thomas S. Social inclusion and the Fatosphere: the role of an online weblogging community in fostering social inclusion. Sociol Health Illness. (2016) 38:797–811. doi: 10.1111/1467-9566.12397

78. Voelker DK, Reel JJ, Greenleaf C. Weight status and body image perceptions in adolescents: current perspectives. Adolesc Health Med Ther. (2015) 6:149–58. doi: 10.2147/AHMT.S68344

79. Fiks AG, Gruver RS, Bishop-Gilyard CT, Shults J, Virudachalam S, Suh AW, et al. A social media peer group for mothers to prevent obesity from infancy: the Grow2Gether randomized trial. Childhood Obes. (2017) 13:356–68. doi: 10.1089/chi.2017.0042

80. Swindle TM, Ward WL, Whiteside-Mansell L. Facebook: the use of social media to engage parents in a preschool obesity prevention curriculum. J Nutr Educ Behav. (2018) 50:4–10.e1. doi: 10.1016/j.jneb.2017.05.344

81. Li JS, Barnett TA, Goodman E, Wasserman RC, Kemper AR. Approaches to the prevention and management of childhood obesity: the role of social networks and the use of social media and related electronic technologies. Circulation. (2013) 127:260–7. doi: 10.1161/CIR.0b013e3182756d8e

82. He C, Wu S, Zhao Y, Li Z, Zhang Y, Le J, et al. Social media–promoted weight loss among an occupational population: cohort study using a WeChat mobile phone app-based campaign. J Med Internet Res. (2017) 19:e7861. doi: 10.2196/jmir.7861

83. Das L, Mohan R, Makaya T. The bid to lose weight: impact of social media on weight perceptions, weight control and diabetes. Curr Diabetes Rev. (2014) 10:291–7. doi: 10.2174/1573399810666141010112542

84. Pagoto S, Schneider KL, Evans M, Waring ME, Appelhans B, Busch AM, et al. Tweeting it off: characteristics of adults who tweet about a weight loss attempt. J Am Med Inform Assoc. (2014) 21:1032–7. doi: 10.1136/amiajnl-2014-002652

85. Ferguson CJ, Muñoz ME, Garza A, Galindo M. Concurrent and prospective analyses of peer, television and social media influences on body dissatisfaction, eating disorder symptoms and life satisfaction in adolescent girls. J Youth Adolesc. (2014) 43:1–14. doi: 10.1007/s10964-012-9898-9

86. Vynck G, Zakrzewski C, Dwoskin E, Lerman R. Big tech CEOs face lawmakers in House Hearing on Social Media's Role in Extremism, Misinformation. Washington Post. Available online at: https://www.washingtonpost.com/technology/2021/03/25/facebook-google-twitter-house-hearing-live-updates/ (accessed June 15, 2021).

87. Friedman KE, Ashmore JA, Applegate KL. Recent experiences of weight-based stigmatization in a weight loss surgery population: psychological and behavioral correlates. Obesity. (2008) 16:S69–74. doi: 10.1038/oby.2008.457

88. Gündüz U. The effect of social media on identity construction. Mediterran J Soc Sci. (2017) 8:85. doi: 10.1515/mjss-2017-0026

89. Calvert SL. Identity construction on the Internet. In: Children in the Digital Age: Influences of Electronic Media on Development. Westport, CT: Praeger Publishers/Greenwood Publishing Group (2002). p. 57–70.

90. Chrisler JC, Fung KT, Lopez AM, Gorman JA. Suffering by comparison: twitter users' reactions to the Victoria's Secret Fashion Show. Body Image. (2013) 10:648–52. doi: 10.1016/j.bodyim.2013.05.001

91. Fardouly J, Vartanian LR. Negative comparisons about one's appearance mediate the relationship between Facebook usage and body image concerns. Body Image. (2015) 12:82–8. doi: 10.1016/j.bodyim.2014.10.004

92. Klassen KM, Borleis ES, Brennan L, Reid M, McCaffrey TA, Lim MS. What people “Like”: analysis of social media strategies used by food industry brands, lifestyle brands, and health promotion organizations on Facebook and Instagram. J Med Internet Res. (2018) 20:e10227. doi: 10.2196/10227

93. Rutter H, Michael K, Repak B, Campoverde-Reinoso C, Hoang T, Berenson K. #Bopo: The Effect of Body Positive Social Media Content on Women's Mood and Self-Compassion. Student Publications (2020). Available online at: https://cupola.gettysburg.edu/student_scholarship/896 (accessed June 16, 2021).

94. Lee M, Lee H-H. Effects of body positivity and types of expression on social media, and women's subjective body size on mood and appearance satisfaction. Fashion Textile Res J. (2020) 22:170–80. doi: 10.5805/SFTI.2020.22.2.170

95. Cohen R, Fardouly J, Newton-John T, Slater A. #BoPo on Instagram: an experimental investigation of the effects of viewing body positive content on young women's mood and body image. New Media Soc. (2019) 21:1546–64. doi: 10.1177/1461444819826530

96. Brathwaite KN, DeAndrea DC. BoPopriation: how self-promotion and corporate commodification can undermine the body positivity (BoPo) movement on Instagram. Commun Monogr. (2021) 1–22. doi: 10.1080/03637751.2021.1925939

97. Miller AL. Eating the other Yogi: Kathryn Budig, the yoga industrial complex, and the appropriation of body positivity. Race Yoga. (2016) 1:1–22. doi: 10.5070/R311028507

98. Cwynar-Horta J. The commodification of the body positive movement on Instagram. Stream. (2016) 8:36–56. doi: 10.21810/strm.v8i2.203

99. Lazuka RF, Wick MR, Keel PK, Harriger JA. Are we there yet? Progress in depicting diverse images of beauty in instagram's body positivity movement. Body Image. (2020) 34:85–93. doi: 10.1016/j.bodyim.2020.05.001

100. Webb JB, Vinoski ER, Bonar AS, Davies AE, Etzel L. Fat is fashionable and fit: a comparative content analysis of Fatspiration and Health at Every Size® Instagram images. Body Image. (2017) 22:53–64. doi: 10.1016/j.bodyim.2017.05.003

101. Perrin A, Anderson M. Share of U.S. Adults Using Social Media, Including Facebook, Is Mostly Unchanged Since 2018. Pew Research Center (2019). Available online at: https://www.pewresearch.org/fact-tank/2019/04/10/share-of-u-s-adults-using-social-media-including-facebook-is-mostly-unchanged-since-2018/ (accessed December 7, 2020).

102. The Commonwealth of Massachusetts Joint Committee on the Judiciary. An Act Making Discrimination on the Basis of Height and Weight Unlawful. S.2495 Jan (2020).

103. Michigan Department of Civil Right. For Victims of Unlawful Discrimination. (2020). Available online at: https://www.michigan.gov/mdcr/0,4613,7-138-4954_4997-16288–,00.html (accessed June 15, 2021).

104. Puhl RM, Suh Y, Li X. Legislating for weight-based equality: national trends in public support for laws to prohibit weight discrimination. Int J Obes. (2016) 40:1320–4. doi: 10.1038/ijo.2016.49

105. Suh Y, Puhl R, Liu S, Milici FF. Support for laws to prohibit weight discrimination in the united states: public attitudes from 2011 to 2013. Obesity. (2014) 22:1872–9. doi: 10.1002/oby.20750

106. Puhl RM, Latner JD, O'brien KS, Luedicke J, Danielsdottir S, Salas XR. Potential policies and laws to prohibit weight discrimination: public views from 4 countries. Milbank Quart. (2015) 93:691–731. doi: 10.1111/1468-0009.12162

107. Lydecker JA, Cotter EW, Palmberg AA, Simpson C, Kwitowski M, White K, et al. Does this Tweet make me look fat? A content analysis of weight stigma on Twitter. Eat Weight Disord. (2016) 21:229–35. doi: 10.1007/s40519-016-0272-x

108. Alba D. On Facebook, Misinformation Is More Popular Now Than in 2016. The New York Times (2020). Available online at: https://www.nytimes.com/2020/10/12/technology/on-facebook-misinformation-is-more-popular-now-than-in-2016.html (accessed June 16, 2021).

109. Ortutay B, Arbel T. Social Media Platforms Face a Reckoning Over Hate Speech. Associated Press (2021). Available online at: https://apnews.com/article/donald-trump-ap-top-news-ca-state-wire-social-media-technology-6d0b3359ee5379bd5624c9f1024a0eaf (accessed June 16, 2021).

110. Solon O. Facebook Management Ignored Internal Research Showing Racial Bias, Current and Former Employees Say. NBC News. Available online at: https://www.nbcnews.com/tech/tech-news/facebook-management-ignored-internal-research-showing-racial-bias-current-former-n1234746 (accessed June 17, 2021).

111. Biddle S, Ribeiro PV, Dias T. Invisible Censorship: TikTok Told Moderators to Suppress Posts by “Ugly” People and the Poor to Attract New Users. The Intercept (2020). Available online at: https://theintercept.com/2020/03/16/tiktok-app-moderators-users-discrimination/ (accessed June 17, 2021).

112. Facebook Inc. Community Standards: Hate Speech. Facebook Community Standards. Available online at: https://www.facebook.com/communitystandards/objectionable_content (accessed June 15, 2021).

113. Facebook Inc. Community Standards: Violent and Graphic Content. Available online at: https://www.facebook.com/communitystandards/graphic_violence (accessed June 17, 2021).

114. Facebook Inc. Community Standards: Adult Nudity and Sexual Activity. Available online at: https://www.facebook.com/communitystandards/graphic_violence (accessed June 17, 2021).

115. Instagram Inc. Community Guidelines F. Available online at: https://about.instagram.com/blog/announcements/instagram-community-guidelines-faqs (accessed June 17, 2021).

116. Twitter Inc. Twitter's Policy on Hateful Conduct. (2021). Available online at: https://help.twitter.com/en/rules-and-policies/hateful-conduct-policy (accessed June 17, 2021).

117. Twitter Inc. Sensitive Media Policy. Available online at: https://help.twitter.com/en/rules-and-policies/hateful-conduct-policy (accessed June 17, 2021).

118. TikTok. Community Guidelines. Available online at: https://www.tiktok.com/community-guidelines?lang=en#38 (accessed June 17, 2021).

119. Reddit Inc. Promoting Hate Based on Identity or Vulnerability. Reddit Help. Available online at: https://reddit.zendesk.com/hc/en-us/articles/360045715951-Promoting-Hate-Based-on-Identity-or-Vulnerability (accessed June 17, 2021).

120. Reddit Inc. Do Not Threaten, Harass, or Bully. Reddit Help. Available online at: https://reddit.zendesk.com/hc/en-us/articles/360045715951-Promoting-Hate-Based-on-Identity-or-Vulnerability (accessed June 17, 2021).

121. Pinterest. Community Guidelines. Pinterest Policy (2021). Available online at: https://policy.pinterest.com/en/community-guidelines (accessed July 4, 2021).

122. Pinterest. Advertising Guidelines. Pinterest Policy (2021). Available online at: https://policy.pinterest.com/en/advertising-guidelines (accessed July 4, 2021).

123. Google. Hate Speech Policy. YouTube (2021). Available online at: https://support.google.com/youtube/answer/2801939?hl=en&ref_topic=2803176 (accessed June 16, 2021).

124. Weimann G, Masri N. Research note: spreading hate on TikTok. Stud Conflict Terrorism. (2020) 1–14. doi: 10.1080/1057610X.2020.1780027

125. Pinterest. Pinterest Embraces Body Acceptance With New Ad Policy. Pinterest Newsroom (2021). Available online at: https://newsroom.pinterest.com/en/post/pinterest-embraces-body-acceptance-with-new-ad-policy (accessed July 4, 2021).

126. Brown I, Flint SW. Weight bias and the training of health professionals to better manage obesity: what do we know and what should we do? Curr Obes Rep. (2013) 2:333–40. doi: 10.1007/s13679-013-0070-y

127. Cravens JD, Pratt KJ, Palmer E, Aamar R. Marriage and family therapy students' views on including weight bias training into their clinical programs. Contemp Fam Ther. (2016) 38:210–22. doi: 10.1007/s10591-015-9366-2

128. Poustchi Y, Saks NS, Piasecki AK, Hahn KA, Ferrante JM. Brief intervention effective in reducing weight bias in medical students. Fam Med. (2013) 45:345–8.

129. Facebook Inc. Misleading Claims. Facebook Advertising Policies. Available online at: https://m.facebook.com/policies/ads/prohibited_content/misleading_claims (accessed June 16, 2021).

130. Katy Steinmetz. Inside Instagram's Ambitious Plan to Fight Bullying | Time. Time (2019). Available online at: https://time.com/5619999/instagram-mosseri-bullying-artificial-intelligence/ (accessed June 15, 2021).

131. Mozafari M, Farahbakhsh R, Crespi N. Hate speech detection and racial bias mitigation in social media based on BERT model. PLoS ONE. (2020) 15:e0237861. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0237861

132. Phelan SM, Dovidio JF, Puhl RM, Burgess DJ, Nelson DB, Yeazel MW, et al. Implicit and explicit weight bias in a national sample of 4,732 medical students: the medical student CHANGES study. Obesity. (2014) 22:1201–8. doi: 10.1002/oby.20687

133. Schwartz MB, Chambliss HO, Brownell KD, Blair SN, Billington C. Weight bias among health professionals specializing in obesity. Obesity Res. (2003) 11:1033–9. doi: 10.1038/oby.2003.142

134. Myers A, Rosen JC. Obesity stigmatization and coping: relation to mental health symptoms, body image, and self-esteem. Int J Obe. (1999) 23:221–30. doi: 10.1038/sj.ijo.0800765

135. Vartanian LR. Development and validation of a brief version of the Stigmatizing Situations Inventory. Obes Sci Pract. (2015) 1:119–25. doi: 10.1002/osp4.11

136. Nguyen MH, Gruber J, Fuchs J, Marler W, Hunsaker A, Hargittai E. Changes in digital communication during the COVID-19 global pandemic: implications for digital inequality and future research. Soc Media Soc. (2020) 6:1–6. doi: 10.1177/2056305120948255

137. Lieberman A, Schroeder J. Two social lives: how differences between online and offline interaction influence social outcomes. Curr Opin Psychol. (2020) 31:16–21. doi: 10.1016/j.copsyc.2019.06.022

138. Subrahmanyam K, Frison E, Michikyan M. The relation between face-to-face and digital interactions and self-esteem: a daily diary study. Hum Behav Emerg Technol. (2020) 2:116–27. doi: 10.1002/hbe2.187

139. Okdie BM, Guadagno RE, Bernieri FJ, Geers AL, Mclarney-Vesotski AR. Getting to know you: face-to-face versus online interactions. Comput Hum Behav. (2011) 27:153–9. doi: 10.1016/j.chb.2010.07.017

140. Rubino F, Puhl RM, Cummings DE, Eckel RH, Ryan DH, Mechanick JI, et al. Joint international consensus statement for ending stigma of obesity. Nat Med. (2020) 26:485–97. doi: 10.1038/s41591-020-0803-x

141. McKnight L, Whitburn B. The fetish of the lens: persistent sexist and ableist metaphor in education research. Int J Qual Stud Educ. (2017) 30:821–31. doi: 10.1080/09518398.2017.1286407

143. Pérez-Sabater C. Research on sexist language in EFL literature: towards a non-sexist approach. In: Porta Linguarum Revista Internacional de Didáctica de las Lenguas Extranjeras. Universidad de Granada (2015). p. 187–203. Available online at: https://riunet.upv.es/handle/10251/63096 doi: 10.30827/Digibug.53766 (accessed June 17, 2021).

144. Covarrubias A, Vélez V. Critical race quantitative intersectionality: an anti-racist research paradigm that refuses to “Let the Numbers Speak for Themselves.” In: Handbook of Critical Race Theory in Education. New York, NY: Routledge (2013).

Keywords: weight stigma, social media, disordered eating, obesity, weight bias internalization

Citation: Clark O, Lee MM, Jingree ML, O'Dwyer E, Yue Y, Marrero A, Tamez M, Bhupathiraju SN and Mattei J (2021) Weight Stigma and Social Media: Evidence and Public Health Solutions. Front. Nutr. 8:739056. doi: 10.3389/fnut.2021.739056

Received: 09 July 2021; Accepted: 18 October 2021;

Published: 12 November 2021.

Edited by:

Shaojing Sun, Fudan University, ChinaReviewed by:

Reza Rastmanesh, Independent Researcher, Tehran, IranWesley Barnhart, Bowling Green State University, United States

Xiaomeng Xie, China-US (Henan) Hormel Cancer Institute, China

Copyright © 2021 Clark, Lee, Jingree, O'Dwyer, Yue, Marrero, Tamez, Bhupathiraju and Mattei. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Josiemer Mattei, am1hdHRlaUBoc3BoLmhhcnZhcmQuZWR1

†These authors have contributed equally to this work

Olivia Clark1†

Olivia Clark1† Matthew M. Lee

Matthew M. Lee Muksha Luxmi Jingree

Muksha Luxmi Jingree Abrania Marrero

Abrania Marrero Martha Tamez

Martha Tamez Josiemer Mattei

Josiemer Mattei