Abstract

This study aims to verify the effects of “legume-based noodles” as a staple food for lunch, specifically: blood glucose, cognitive function tests, Kansei value, work questionnaires, typing, and body weight. The experiment is divided into two groups: the intervention group (legumes-based noodle) and the control group (regular lunch). Both groups have similar menu except the staple food. The intervention group resulted in a statistically significant lower blood glucose area under the curve (AUC) and lower maximum blood glucose levels during the afternoon work hours on weekdays. In addition, the Kansei value “concentration” decreased at the end of the workday in the control group compared to before and after lunch but did not decrease in the intervention group. Furthermore, the number of typing accuracy was higher in the intervention group than in the control group, and the questionnaire responses for “work efficiency” and “motivation” were more positive. These results suggest that eating legume-based noodles may lead to improved performance of office workers.

Introduction

According to the United Nation's World Population Aging report in 2019, Japan was one of the countries with the most-aged population (34% aged 60 or over), and it is projected to remain so through 2050 (43.9% aged 60 or over) (1). It was also predicted that Japan's workforce will be 40% smaller in 2050, compared to 2000 (2). The long working hours are a major problem in many countries including Japan (3). A study reviewing diseases attributed to long working hours highlighted that: “The Western Pacific, South-East Asia, men, and older people carried higher burdens” (4). Consequently, increasing work efficiency while maintaining the health and well-being of workers in Japan is an important problem to solve.

Along with the aging society comes the health conditions related to old age, such as hearing loss, low vision, back and neck pain, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), diabetes, depression, and dementia (5). Diet has been investigated in relation to its ability to promote cognitive function (6–9), and the findings indicate that a healthy diet may have benefits on cognitive function. The cognitive function here refers to one's performance of various mental processes such as memory, learning, reasoning, and language (American Psychological Association).

Additionally, the correlation between sugar and mental concentration was also found in several studies (10–12); although, hyperglycemia is generally not desirable and is linked with the aforementioned diseases (13–15). Furthermore, an unhealthy diet was found to be directly or indirectly correlated with productivity loss (16–18), while the worksite nutrition intervention program was proven effective to improve the wellbeing of the workers (19).

Legumes have been known to produce some health benefits in humans (20–22). They are protein sources with high vitamins, minerals, and antioxidants concentration, and they were also said to be beneficial for patients with diabetes and celiac diseases, as well as for weight management purposes (23). A vegetarian-based diet intervention has also been found to improve work performance, quality-of-life, manage body weight, and cardiovascular diseases (24–26). As such, this study aims to verify the effects of the noodles that are created from legumes, named “legume-based noodles,” as a staple food for lunch, specifically its effects on blood glucose, emotion, work questionnaires, and typing test.

Materials and Methods

This study was approved by the ethics committees of Keio University and performed in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. This study design was registered in UMIN (University hospital Medical Information Network) with registration number UMIN000041239. The study was a non-randomized, open-label, single-arm intervention study. In this section, the foods used in this study and the devices, software, and tools for obtaining the study outcomes are described.

Foods and Devices

The Memory Performance Index (MPI) score: obtained from the Japanese version of “The MCI Screen” (27, 28) was provided by Millennia Corporation.

Continuous glucose monitoring device: Freestyle Libre from Abbott (29).

Kansei values: An emotion analyzer from Dentsu ScienceJam was used (30). Kansei values were computed from the subject's brainwaves. The participants' brainwaves were obtained by an EEG with a sampling rate of 512 Hz (Dentsu ScienceJam Inc.). Kansei is originally a Japanese word, and Kansei engineering is commonly synonymous with “affective engineering” (American Psychological Association). Originally, Kansei engineering meant using a user's subjective feelings to improve a product. In this study, Kansei values are the five types of feelings that are converted into numbers. The Kansei values are as follows: Stress, Like, Interest, Calmness, and Concentration.

Typing test: C-type software (31) was used for this test. Typical computers were utilized for the typing test, with Windows Operating System and Japanese-layout keyboard (QWERTY JIS).

Questionnaire: The perceived work performance (morning work and afternoon work), motivation (for afternoon work and the day after), and meal contents. The participants were asked to score the questionnaire on a scale of 1–10 points, except for meal contents.

Test foods: White bread (Pasco Shikishima Corporation), Hamburg steak with mixed greens (Seven-Eleven Japan Co., Ltd.), protein drink (Meiji Holdings Co., Ltd.), white rice (Sato Foods Co., Ltd.), salt-grilled mackerel with mixed greens (Seven-Eleven Japan Co., Ltd.), udon noodles (Shidamaya Corporation), simmered flounder with 4 side dishes (Nichirei Corporation), grilled beef (Yoshinoya Co., Ltd.), and legume-based noodles (ZENB Japan Co., Ltd.). The nutrients of these foods are described in Table 1.

Table 1

| Energy | Protein | Fat | Carbohydrate | Sodium | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (kcal) | (g) | (g) | (g) | (g) | |

| White bread | 197 | 5.9 | 3.1 | 36.3 | 0.9 |

| White rice | 191 | 2.7 | 0 | 44.1 | 0 |

| Udon noodles | 225 | 5 | 1 | 49.1 | 1.2 |

| Egg | 74 | 6.29 | 4.97 | 0.38 | 0.07 |

| Legumes-based noodles | 261 | 16.6 | 2.5 | 55.1 | 0.05 |

| Protein drink | 75 | 12.5 | 0 | 6.3 | 0 |

| Hamburg steak | 281 | 17 | 17.3 | 16.5 | 2 |

| Salt-grilled mackerel | 336 | 17.4 | 29.5 | 0.2 | 1 |

| Mixed greens | 20 | 1 | 0.1 | 4.5 | 0 |

| Simmered flounder with | 268 | 15.3 | 15.1 | 20 | 0.705 |

| 4 side dishes | |||||

| Grilled beef | 286 | 12.6 | 22.3 | 8.8 | 0.8 |

Energy and nutrients from each food used in this study.

Data Acquisition

The experiment was performed for 15 days, with the first week (day 1 to day 7) acting as a control and the second week (day 8 to day 14) as an intervention. Day 15 consists only of MPI measurement, which was conducted before breakfast. The first day of the week (day 1 and day 8) was Saturday, and the last day of the week (day 7 and day 14) was Friday.

The participants were asked to measure their weight every day. The blood glucose level was measured every day, while the Kansei score, typing test, and questionnaire were conducted only during working days (Monday–Friday). During Saturdays, only the weight measurement and the MPI test were conducted. The legume-based noodles were boiled in hot water for 6 min just before consumption. Other foods are ready to eat.

During both the control session and the intervention session, the participants' lunch was restricted, as depicted in Table 2. The fat, protein, and carbohydrates in lunch were controlled to be equal. Nevertheless, the time when the participants took their lunch was not regular. The contents and the time of the participant's breakfast were not regular nor restricted. The flowchart of the experiment is described in Figure 1.

Table 2

| Control week | Intervention week | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Staple food | Dish | Drink | Staple food | Side dish | Drink | |

| Day 1 Sat | White bread | Hamburg steak with mixed greens | Protein milk | Legumes-based noodles | Hamburg steak with mixed greens | Water |

| Day 2 Sun | Japanese Rice | Salt-grilled mackerel with mixed greens | Protein milk | Legumes-based noodles | Salt-grilled mackerel with mixed greens | Water |

| Day 3 Mon | Udon noodles with raw eggs | Grilled beef | Protein milk | Legumes-based noodles with raw eggs | Grilled beef | Water |

| Day 4 Tue | Japanese Rice | Simmered flounder with 4 side dishes | Protein milk | Legumes-based noodles | Simmered flounder with 4 side dishes | Water |

| Day 5 Wed | Udon noodles with raw eggs | Grilled beef | Protein milk | Legumes-based noodles with raw eggs | Grilled beef | Water |

| Day 6 Thu | White bread | Hamburg steak | Protein milk | Legumes-based noodles | Hamburg steak | Water |

| Day 7 Fri | Japanese Rice | Simmered flounder | Protein milk | Legumes-based noodles | Simmered flounder | Water |

Participants' meal plan during the experiments.

Figure 1

Experimental flow.

Participants

A total of 10 persons (average age = 37 ± 6.43 years; 7 men, 3 women) voluntarily participated in this study and provided written informed consent. Blood glucose level, MPI score, Kansei score, Profile of Mood States (POMS) questionnaire, typing test result, and body weight were recorded, as described in Table 3.

Table 3

| Blood glucose level | 6 days |

| 1 day-off (Sunday) + 5 working days | |

| MPI score | 2 times |

| first day of the week and last day of the week | |

| Kansei score from EEG | 15 times |

| 3 times per day, 5 working days | |

| POMS Questionnaire | 10 times |

| 2 times per day, 5 working days | |

| Typing test result | 5 times |

| 1 time per day, 5 working days | |

| Weight | 7 times |

| 1 time per day |

Obtained data from each of the control experiment and intervention experiment.

The inclusion criteria of this study were:

Healthy men and women aged between 20 and 60;

Company employees who usually work in an office; and

Those who understand the contents of the test and provide informed consent.

The exclusion criteria of this study were as follows:

Those with a significant medical history (including receiving medical treatment) or mental illness; and

Those who are judged by the responsible investigator to be inappropriate for participation in the study.

Of which, 2 Kansei scores from the intervention sessions were corrupted, 1 typing test result during the intervention session was lost, and 1 typing test result during the control session was corrupted. These lost and corrupted data were not considered for the analysis. In this article, the weight and the MPI score were not analyzed.

Statistical Analysis

Statistical analysis was performed using MATLAB and Python in a typical computer. The significance testing was made using a paired t-test.

Results

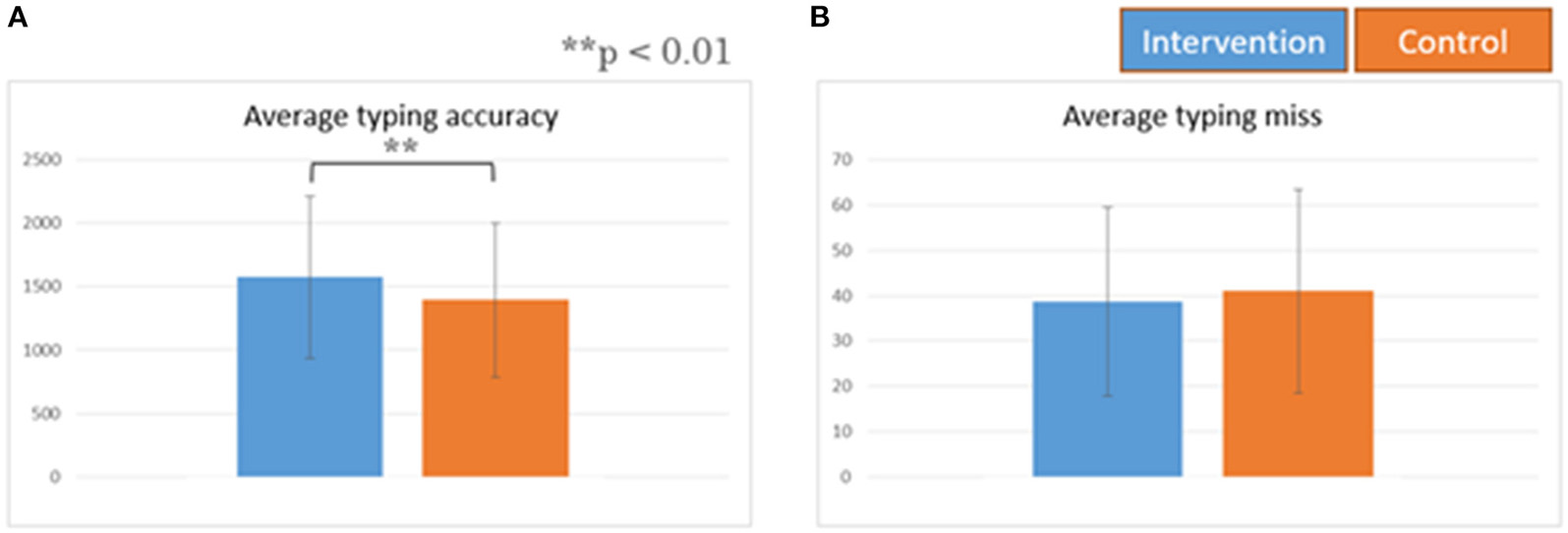

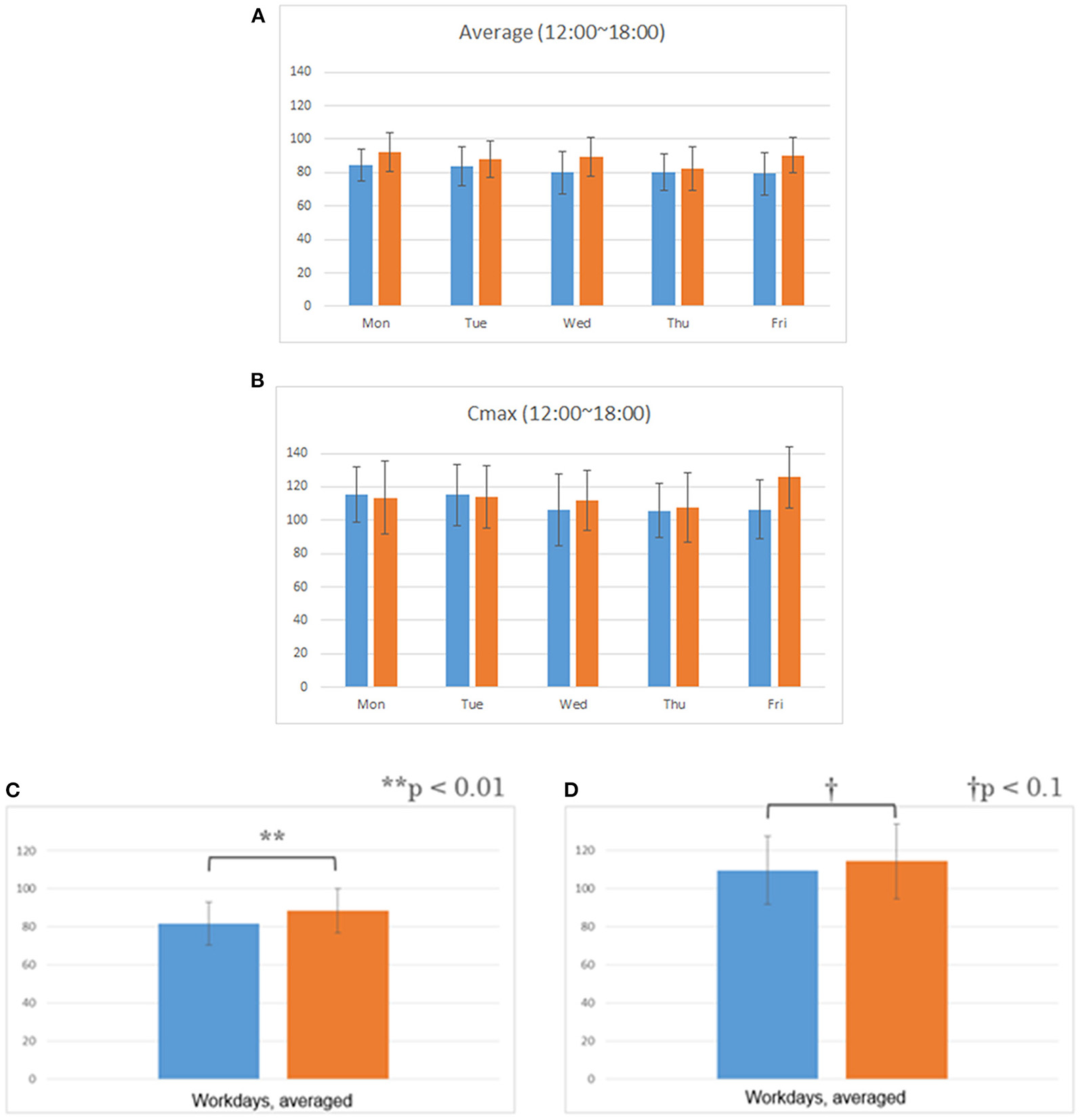

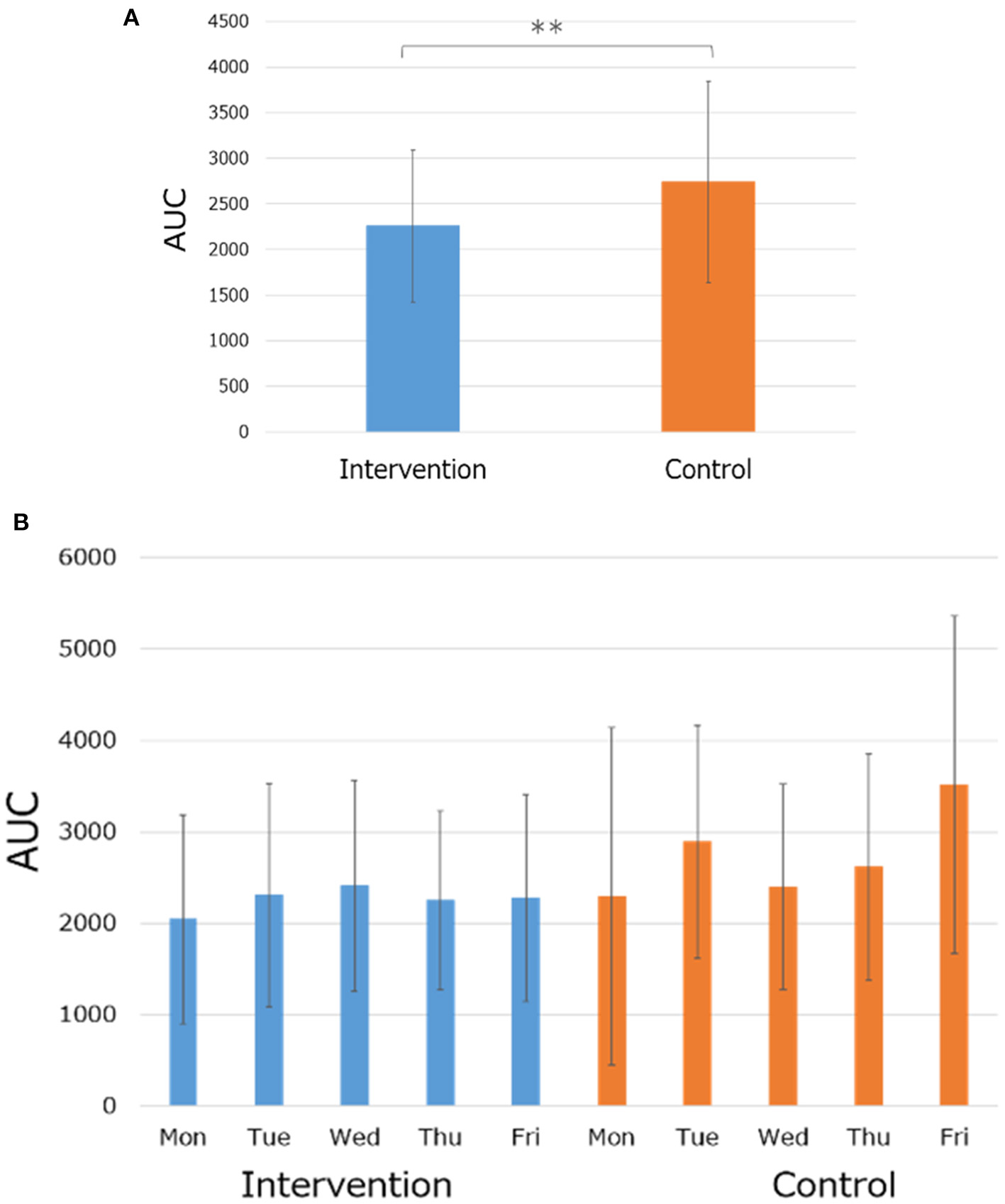

The consumption of legume-based noodles as lunch resulted in a statistically significant increase in the typing accuracy score, but no difference in the typing miss score (Figure 2). It also resulted in lower blood glucose levels, compared to the control. The comparison of Cmax (highest blood glucose level) also showed similar results: the intervention session results showed a lower Cmax compared to the control session (Figure 3). Similar results were also found in the blood area under the curve (AUC) (Figure 4).

Figure 2

Average typing performance. All data are means ± SD of 10 subjects. (A) Average typing accuracy. (B) Average typing miss.

Figure 3

Blood glucose level after lunch. All data are means ± SD of 10 subjects. (A) Daily average of blood glucose level. (B) Daily average of blood glucose Cmax level. (C) Weekly average of blood glucose level. (D) Weekly average of blood glucose Cmax level.

Figure 4

Postprandial blood glucose AUC. All data are means ± SD of 10 subjects. (A) Average of five weekdays. (B) Data of each weekday.

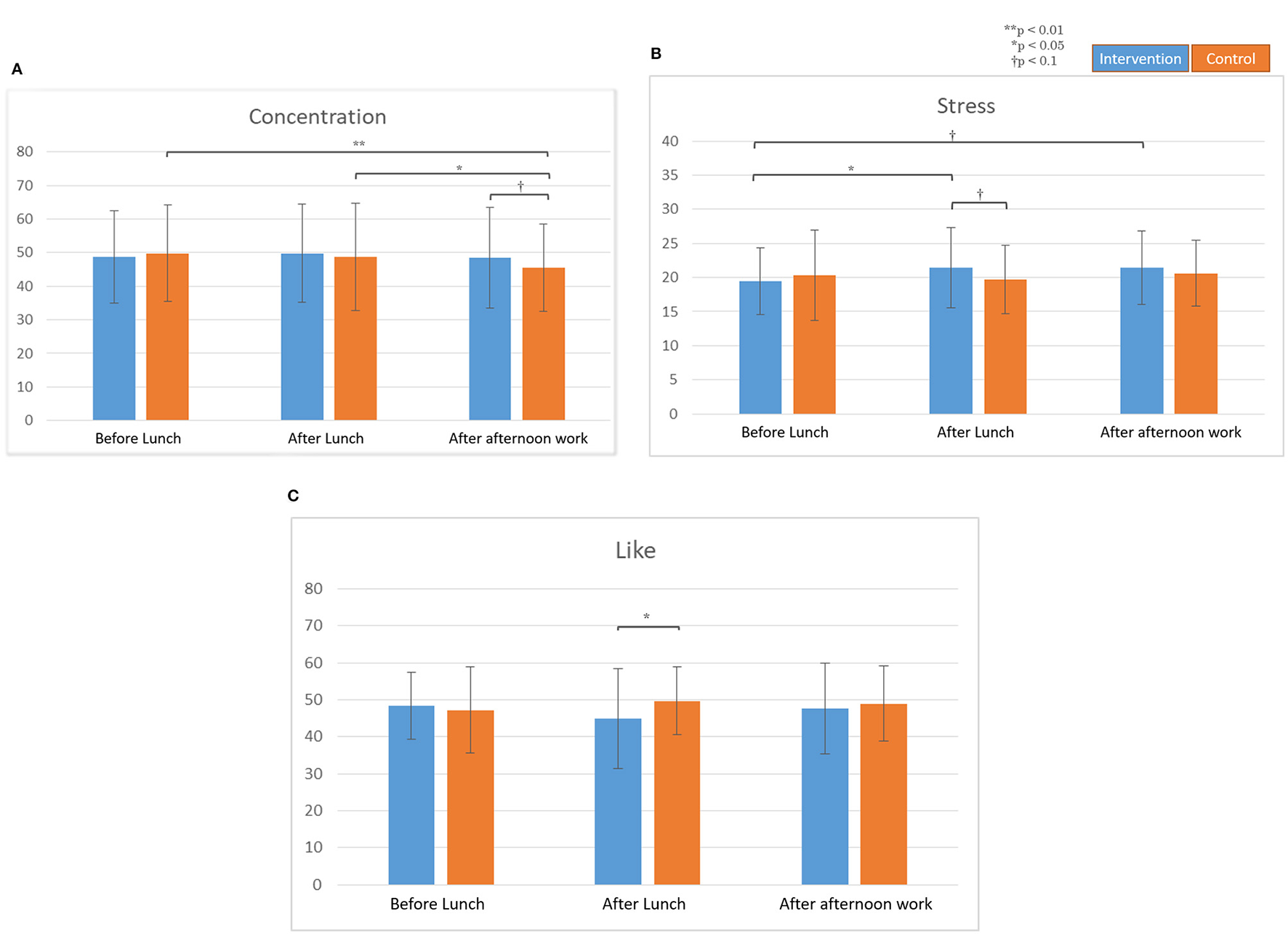

From the results of Kansei values, higher concentration values were observed from the subjects during an intervention session (post-afternoon work) compared to the control session (Figure 5A). Higher stress values were observed from the participants during the intervention session (post-meal) compared to the control session. Lower like values were observed from participants during the intervention session (post-meal) compared to the control session (Figures 5B,C).

Figure 5

Kansei values before and after lunch, and after afternoon work. All data are means ± SD of 10 subjects. (A) Concentration values. (B) Stress values. (C) Like values.

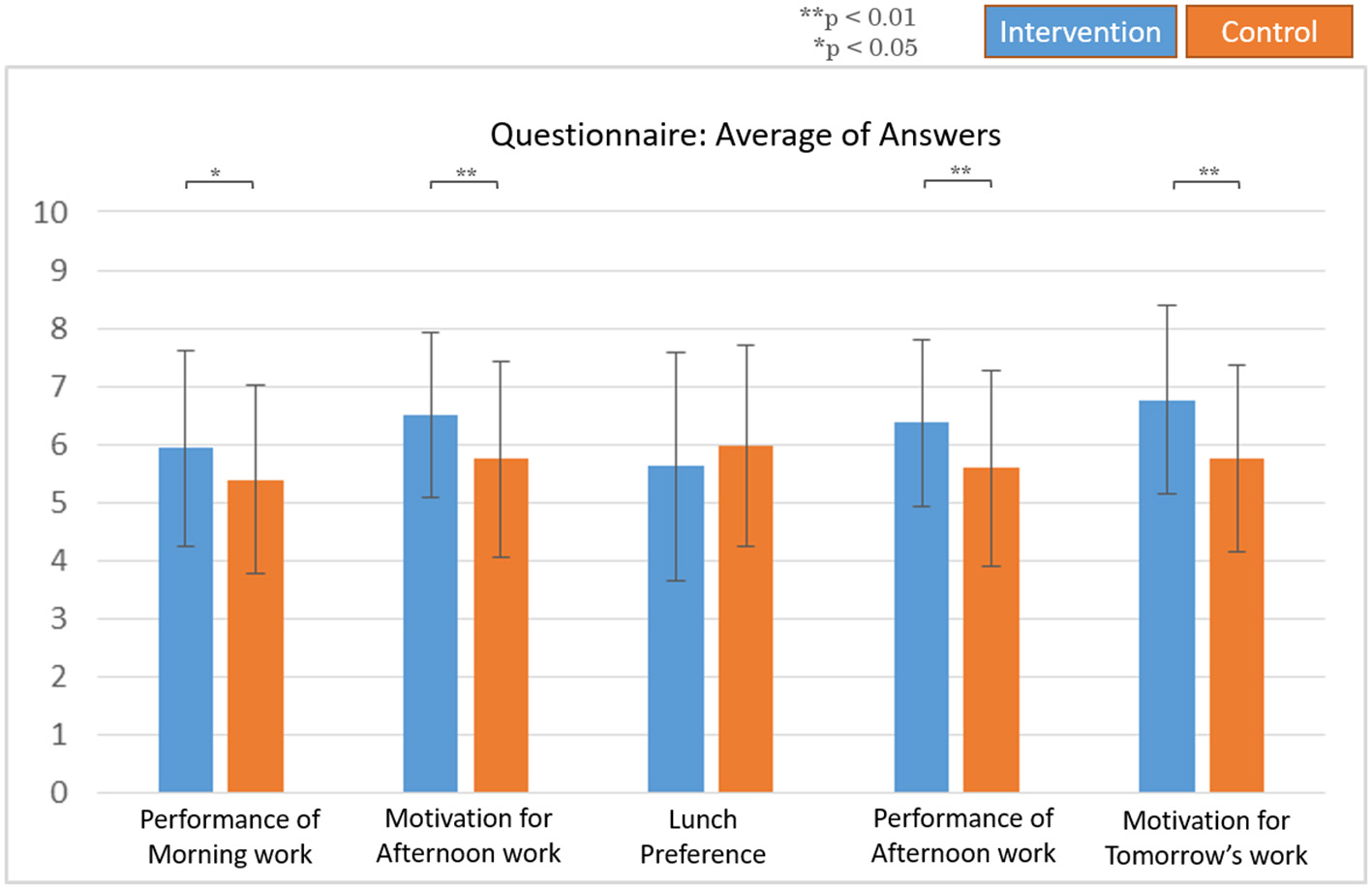

In the questionnaire, the participants answered that they have better performance during both their morning work and afternoon work and have higher motivation toward the afternoon work and tomorrow's work during the intervention session, compared to the control session (Figure 6).

Figure 6

Questionnaire results. All data are means ± SD of 10 subjects.

Discussion

During the intervention session, the participants were asked to consume legume-based noodles as their staple food for lunch and during the control session. The participants were asked to consume rice, white bread, and Udon noodles as their staple food. Blood glucose levels, Kansei values from EEG, POMS questionnaire, and typing test scores were obtained from both sessions. Statistical analysis was made to compare the values obtained from the intervention session and the control session.

From the results of the afternoon work, the intervention session showed a statistically significant lower average blood glucose level, blood glucose AUC, and blood glucose Cmax compared to the control session. The legume-based noodles used in this study were proven to be low GI in a previous study, so these results are consistent with it (32).

It is generally believed that average blood glucose level, blood glucose AUC, and blood glucose Cmax increase after meals (33). In particular, it is considered that the increase is even higher in a diet that is high in sugar such as white rice (34).

Not increasing the average blood glucose level, blood glucose AUC, and blood glucose Cmax after meals reduces the burden on the body and is good for the health (35–40).

In this study, the intervention session showed a significantly higher typing score at the end of the workday than the control group. This may be related to the gradual increase in blood glucose when the subject ingested the test food at lunch. Eating low glycemic index (GI) foods has positive effects on cognitive performance, and it is possible that the same thing happened in this study (41, 42).

Additionally, while the subjects from the control session had a significantly lower average concentration at the end of their afternoon work compared to their average concentration during pre-lunch and post-lunch, the reversed phenomena were found during the intervention session; the average concentration values at the end of the afternoon work were significantly higher compared to the pre-lunch and post-lunch values.

Both typing tests and questionnaires were utilized to measure the outcomes related to work. The typing accuracy, as quantified work performance along with the questionnaire's motivation and work performance, were compared, and in all cases, the intervention session showed better results.

From the results of this study, it was shown that legume-based noodles may improve short-term work performance and motivation, so, we believe that a long-term intake is expected to improve cognitive ability and prevent dementia.

However, some limitations of this study must be considered when interpreting the results of this study. First, the number of study subjects is relatively small. Second, as this study is performed in Japan, most of the ethnicity of the subjects are Asian. Third, the subjects of this study consumed their meal based on their self-control; this might lead to more variance compared to a more restrictive experiment.

In an age where people are expected to live longer and healthier lives, we believe it is highly worthwhile to research foods that are less likely to raise blood glucose levels and have the potential to improve health and/or work performance.

Conclusions

This study aimed to verify the effects of “legume-based noodles.” Several measures were taken in this study and as the outcome, the intervention group resulted in statistically significant lower blood glucose for AUC, lower maximum blood glucose levels, and preventing the decrease of “concentration” aspect in kansei. Furthermore, the typing accuracy was better in the intervention group than in the control group, and the questionnaire responses for “work efficiency” and “motivation” were more positive. This study found that the consumption of legume-based noodles improves the work performance of office workers, with several objective outcomes. As future work, more participants, both in number, age group, and ethnicity, are needed. Additionally, less variability in the control and intervention group may lead to more specific results. Analysis of the weight and the MPI scores might also yield interesting results.

Publisher's Note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Statements

Data availability statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

Ethics statement

The studies involving human participants were reviewed and approved by Keio University Bioethics Committee. The patients/participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study.

Author contributions

BS, JY, HK, MY, TM, and YM: conceptualization, writing, reviewing, and editing. BS and YM: methodology, validation, formal analysis, and writing the original draft preparation. BS: software. YM: investigation, data curation, supervision, project administration, and funding acquisition. JY, HK, MY, and TM: resources and visualization. All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

Conflict of interest

JY, HK, MY, and TM are employees of Mizkan Holdings, Co., Ltd. None of the principal investigators involved in this study or their family members are shareholders in Mizkan Holdings Co., Ltd., or are company officers, directors, or advisors. The remaining authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

References

1.

United Nations. World Population Ageing Report 2019. (2019). Available online at: https://population.un.org/ProfilesOfAgeing2019/index.html (accessed October 28, 2021).

2.

Ministry of Land Infrastructure Transport and Tourism Japan. Ministry of Land, Infrastructure, Transport and Tourism White Paper. (2000). Available online at: https://www.mlit.go.jp/hakusyo/mlit/h14/H14/html/E1023110.html (accessed October 28, 2021).

3.

Organisation For Economic Co-Operation and Development. (2020). Available online at: https://data.oecd.org/emp/hours-worked.htm (accessed October 28, 2021).

4.

PegaFNáfrádiBMomenNCUjitaYStreicherKNPrüss-ÜstünA.et al. Global, regional, and national burdens of ischemic heart disease and stroke attributable to exposure to long working hours for 194 countries, 2000–2016: A systematic analysis from the WHO/ILO Joint Estimates of the Work-related Burden of Disease and Injury. Environ Int. (2021) 154:106595. 10.1016/j.envint.2021.106595

5.

World Health Organization. Ageing and Health. (2018). Available online at: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/ageing-and-health

6.

MazzaEFavaAFerroYMoracaMRotundoSColicaCet al. Impact of legumes and plant proteins consumption on cognitive performances in the elderly. J Transl Med. (2017) 15:1–8. 10.1186/s12967-017-1209-5

7.

McGrattanAMMcEvoyCTMcGuinnessBMcKinleyMCWoodsideJV. Effect of dietary interventions in mild cognitive impairment: a systematic review. Br J Nutr. (2018) 120:1388–405. 10.1017/S0007114518002945

8.

VlachosGSScarmeasN. Dietary interventions in mild cognitive impairment and dementia. Dialogues Clin Neurosci. (2019) 21:69–82. 10.31887/DCNS.2019.21.1/nscarmeas

9.

WengreenHMungerRGCutlerAQuachABowlesACorcoranCet al. Prospective study of Dietary Approaches to Stop Hypertension–and Mediterranean-style dietary patterns and age-related cognitive change: the Cache County Study on Memory, Health and Aging. Am J Clin Nutr. (2013) 98:1263–71. 10.3945/ajcn.112.051276

10.

BellisleF. Effects of diet on behaviour and cognition in children. Br J Nutr. (2004) 92:S227–32. 10.1079/BJN20041171

11.

RibyLMLawASMclaughlinJMurrayJ. Preliminary evidence that glucose ingestion facilitates prospective memory performance. Nutr Res. (2011) 31:370–7. 10.1016/j.nutres.2011.04.003

12.

Sünram-LeaSIFosterJKDurlachPPerezC. Glucose facilitation of cognitive performance in healthy young adults: examination of the influence of fast-duration, time of day and pre-consumption plasma glucose levels. Psychopharmacology. (2001) 157:46–54. 10.1007/s002130100771

13.

PistroschFNataliAHanefeldM. Is hyperglycemia a cardiovascular risk factor?. Diab Care. (2011) 34:S128–31. 10.2337/dc11-s207

14.

Kubis-KubiakAMRorbach-DolataAPiwowarA. Crucial players in Alzheimer's disease and diabetes mellitus: friends or foes?Mech Ageing Dev. (2019) 181:7–21. 10.1016/j.mad.2019.03.008

15.

YayanEHZenginMAkinciA. The relationship between the quality of life and depression levels of young people with type I diabetes. Perspect Psychiatr Care. (2019). 55:291–9. 10.1111/ppc.12349

16.

MerrillRMAldanaSGPopeJEAndersonDRCoberleyCRWhitmer. Presenteeism according to healthy behaviors, physical health, and work environment. Popul Health Manag. (2012) 15:293–301. 10.1089/pop.2012.0003

17.

YangRHaleLBranasCPerlisMGallagherRKillgoreWet al. 0189 Work productivity loss associated with sleep duration, insomnia severity, sleepiness, and snoring. Sleep. (2018) 41:A74. 10.1093/sleep/zsy061.188

18.

CagampangFRBruceKD. The role of the circadian clock system in nutrition and metabolism. Br J Nutr. (2012) 108:381–92. 10.1017/S0007114512002139

19.

SutliffeJTCarnotMJFuhrmanJHSutliffeCAScheidJC. A worksite nutrition intervention is effective at improving employee well-being: a pilot study. J Nutr Metab. (2018) 2018:8187203. 10.1155/2018/8187203

20.

ClementeAOliasR. Beneficial effects of legumes in gut health. Curr Opin Food Sci. (2017) 14:32–6. 10.1016/j.cofs.2017.01.005

21.

PolakRPhillipsEMCampbellA. Legumes: health benefits and culinary approaches to increase intake. Clin Diab. (2015) 33:198–205. 10.2337/diaclin.33.4.198

22.

RobinsonGHJBalkJDomoneyC. Improving pulse crops as a source of protein, starch and micronutrients. Nutr Bull. (2019) 44:202–15. 10.1111/nbu.12399

23.

MaphosaYVictoriaAJ. The role of legumes in human nutrition. Funct Food. (2017) 1:13. 10.5772/intechopen.69127

24.

MishraSXuJAgarwalUGonzalesJLevinSBarnardND. A multicenter randomized controlled trial of a plant-based nutrition program to reduce body weight and cardiovascular risk in the corporate setting: the GEICO study. Eur J Clin Nutr. (2013) 67:718–24. 10.1038/ejcn.2013.92

25.

AgarwalUMishraSXuJLevinSGonzalesJBarnardND. A multicenter randomized controlled trial of a nutrition intervention program in a multiethnic adult population in the corporate setting reduces depression and anxiety and improves quality of life: the GEICO study. Am J Health Promot. (2015) 29:245–54. 10.4278/ajhp.130218-QUAN-72

26.

FerdowsianHRBarnardNDHooverVJKatcherHILevinSMGreenAAet al. A multicomponent intervention reduces body weight and cardiovascular risk at a GEICO corporate site. Am J Health Promot. (2010) 24:384–7. 10.4278/ajhp.081027-QUAN-255

27.

Medical Care Corp. (2012). MCI Screen Validation & Application. Available online at: http://mciscreen.com/pdf/review2012.pdf (accessed October 28, 2021).

28.

Medical Care Corp. THE MCI SCREEN A Pragmatic Clinical Tool for Assessing Memory Concerns in a Primary Care Setting. (2012). Available online at: https://www.millennia-corporation.jp/ninchi/images/about/whitepaper.pdf (accessed October 28, 2021).

29.

BaileyTBodeBWChristiansenMPKlaffLJAlvaS. The performance and usability of a factory-calibrated flash glucose monitoring system. Diab Technol Therap. (2015) 17:787–94. 10.1089/dia.2014.0378

30.

Dentsu Sciencejam Inc. Emotion Analyzer. (2013). Available online at: https://www.dentsusciencejam.com/kansei-analyzer/en/index.html (accessed January 25, 2022).

31.

SawaY,. C-Type. (2002). Available online at: http://www.vector.co.jp/magazine/softnews/020323/n0203231.html

32.

YoshimotoJKatoYBanMKishiMHorieHYamadaCet al. Palatable noodles as a functional staple food made exclusively from yellow peas suppressed rapid postprandial glucose increase. Nutrients. (2020) 12:1839. 10.3390/nu12061839

33.

CrevoisierCHandschinJBarreJRoumenovDKleinbloesemC. Food increases the bioavailability of mefloquine. Eur J Clin Pharmacol. (1997) 53:135–9. 10.1007/s002280050351

34.

AtkinsonFSFoster-PowellKBrand-MillerJC. International tables of glycemic index and glycemic load values: 2008. Diab Care. (2008) 31:2281–3.10.2337/dc08-1239

35.

MannJCummingsJHEnglystHNKeyTLiuSRiccardiGet al. FAO/WHO scientific update on carbohydrates in human nutrition: conclusions. Eur J Clin Nutr. (2007) 61:S132–7. 10.1038/sj.ejcn.1602943

36.

ObaSNanriAKurotaniKGotoAKatoMMizoueTet al. Dietary glycemic index, glycemic load and incidence of type 2 diabetes in Japanese men and women: the Japan Public Health Center-based Prospective Study. Nutr J. (2013) 12:1–10. 10.1186/1475-2891-12-165

37.

NakagamiT. Hyperglycaemia and mortality from all causes and from cardiovascular disease in five populations of Asian origin. Diabetologia. (2004) 47:385–94. 10.1007/s00125-004-1334-6

38.

TominagaMEguchiHIManakaHIIgarashiKKatoTASekikawaAK. Impaired glucose tolerance is a risk factor for cardiovascular disease, but not impaired fasting glucose. Funagata Diab Study Diab Care. (1999) 22:920–4. 10.2337/diacare.22.6.920

39.

YanaiHKatsuyamaHHamasakiHAbeSTadaNSakoA. Effects of carbohydrate and dietary fiber intake, glycemic index and glycemic load on HDL metabolism in Asian populations. J Clin Med Res. (2014) 6:321. 10.14740/jocmr1884w

40.

GeijselaersSLSepSJClaessensDSchramMTVan BoxtelMPHenryRMet al. The role of hyperglycemia, insulin resistance, and blood pressure in diabetes-associated differences in cognitive performance—the Maastricht Study. Diabetes Care. (2017) 40:1537–47. 10.2337/dc17-0330

41.

CooperSBBandelowSNuteMLMorrisJGNevillME. Breakfast glycaemic index and cognitive function in adolescent school children. Br J Nutr. (2012) 107:1823–32. 10.1017/S0007114511005022

42.

TakiYHashizumeHSassaYTakeuchiHAsanoMAsanoKet al. Breakfast staple types affect brain gray matter volume and cognitive function in healthy children. PLoS ONE. (2010) 5:e15213. 10.1371/journal.pone.0015213

Summary

Keywords

legume-based noodles, blood glucose level, work performance, Kansei engineering, statistical analysis

Citation

Sumali B, Yoshimoto J, Kobayashi H, Yamada M, Maeda T and Mitsukura Y (2022) A Study on Legume-Based Noodles as Staple Food for Office Workers. Front. Nutr. 9:807350. doi: 10.3389/fnut.2022.807350

Received

02 November 2021

Accepted

31 January 2022

Published

11 March 2022

Volume

9 - 2022

Edited by

Maria Fernanda Silva, Universidad Nacional de Cuyo, Argentina

Reviewed by

Jagmeet Madan, SNDT Women's University, India; Azlin Ahmad, Universiti Teknologi MARA, Malaysia

Updates

Copyright

© 2022 Sumali, Yoshimoto, Kobayashi, Yamada, Maeda and Mitsukura.

This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Yasue Mitsukura mitsukura@keio.jp

This article was submitted to Nutrition and Food Science Technology, a section of the journal Frontiers in Nutrition

Disclaimer

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.