Introduction

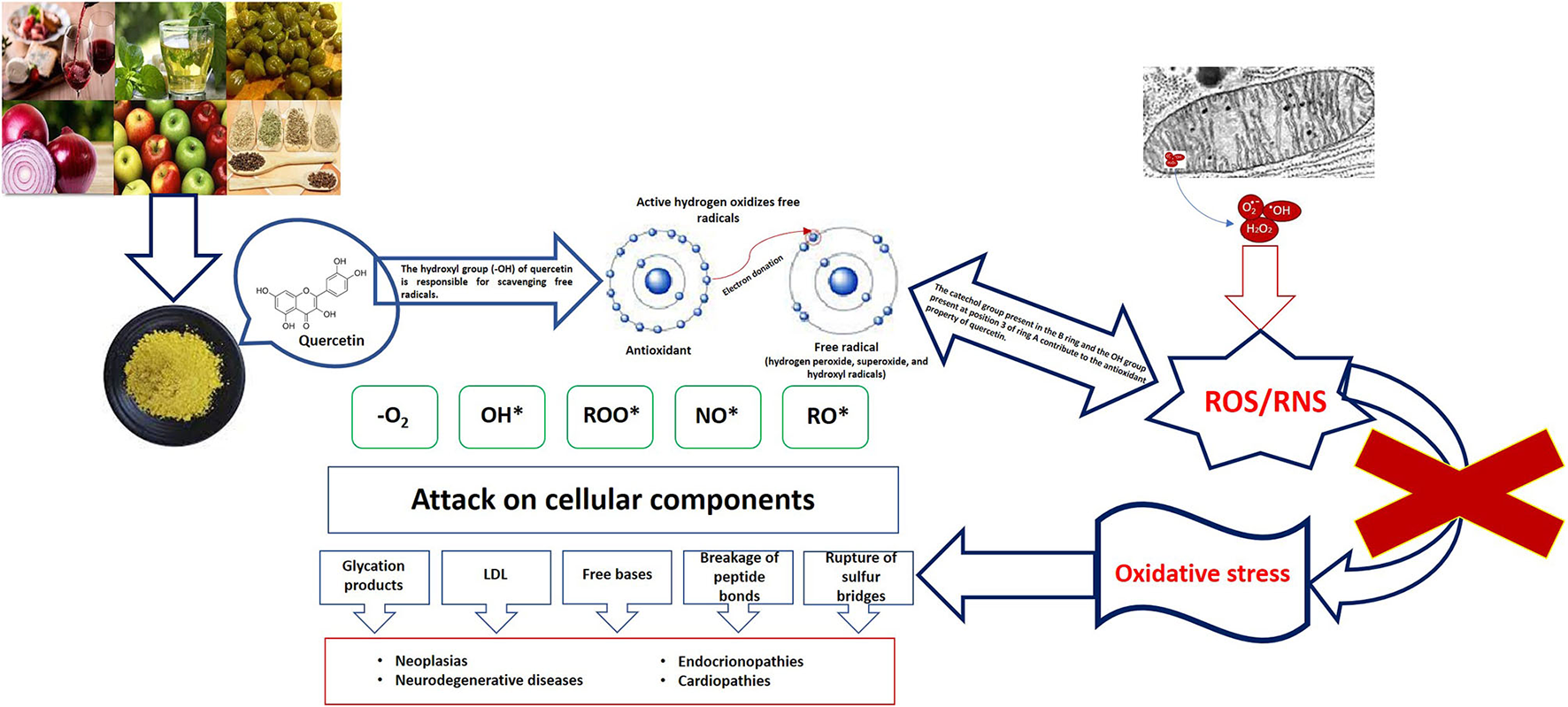

The health emergency resulting from the COVID-19 pandemic has come to an end, as announced by the World Health Organization (WHO) on 5 May this year. Three years after the onset of this health emergency, the WHO said that although the emergency phase is over, the pandemic is not over. However, the sequelae caused by the SARS-CoV-2 virus continue, the fact that patients experience symptoms after recovery from acute infection is not unexpected and is associated with an increased risk of post-infectious sequelae, known as persistent COVID or post-acute sequelae of COVID-19. These sequelae may present with various long-lasting symptoms in the absence of active infection, these symptoms include: the presence of musculoskeletal pain, aging fatigue, mood disturbance, and neurocognitive difficulties (1–4). Currently, persistent COVID does not have effective validated treatments; it is a multifactorial pathology, in which the literature mentions some causes, such as persistence of SARS-CoV-2 reservoirs in body tissues (5, 6); immune dysregulation with or without reactivation of the underlying pathogens (7, 8), the emergence of the Epstein-Barr virus or the human herpesvirus-6 (9–12), microbiota conditions derived from the SARS-CoV-2 attack (6, 13–15), autoimmunity (6, 16–18), microvascular blood coagulation with endothelial dysfunction (6, 19–21) as well as dysfunctional signaling in the brainstem and/or vagus nerve (6, 22, 23), this combined with risk factors such as type 2 diabetes mellitus, sex (mainly female), ethnicity (of Latino origin), socioeconomic factors (low income), exposure to COVID-19 reinfection, the presence of specific antibodies, connective tissue disorders, and attention deficit hyperactivity disorder, however, one third of people with persistent COVID have no preexisting conditions identified (23). Redox abnormalities that occur in persistent COVID are due to functional instability of the mitochondria in addition to alterations in the oxidative stress pathways (24, 25), not leaving aside the presence of a chronic hyperinflammatory condition (26). A lifestyle that involves a lower intake of ultraprocessed and processed foods, daily exercise, and the inclusion of nutritional supplements rich in carotenoids, omega 3, or flavonoids can help in the treatment of persistent COVID. Specifically, flavonoids are a group of natural polyphenolic substances naturally present in different flowers, fruits, vegetables, seeds, and beverages derived from plants such as tea and red wine, which are considered responsible for their characteristic color (27). Quercetin belongs to the classification of flavonoids, and its beneficial functions are associated with its chemical structure, which gives it antioxidant properties. Quercetin neutralizes free radicals such as superoxide anions, nitric oxide, and peroxynitrites (see Figure 1) (28, 29). It can inhibit enzymes such as xanthine oxidase, lipoxygenase, and NADPH oxidase, preventing cell death; in addition, it increases the production of endogenous antioxidants (30, 31). Derived from the antioxidant, anti-inflammatory, hypoglycemic and hypolipidemic properties of Quercetin, it is a good alternative for the treatment of Type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM). By reducing the concentration of glucose levels in the blood, it preserves the function of islet cells, increases the number of pancreatic β-cells, reduces dyslipidemia, increases insulin level and reduces damage from oxidative stress (increases the activity of catalase and heme oxygenase enzymes) (32, 33). Evidence of quercetin administration in diabetic mice for 10 days at 10–15 mg/kg shows a reduction in peripheral blood glucose and triglyceride levels, as well as increased enzyme activity of hexokinase and glucokinase (34). Mahadev et al. (35) recommends that the consumption of Quercetin (15–100 mg/kg) should be for a period of 14–70 days to be considered as a potential alternative in the treatment of T2DM. Quercetin has been shown to bring health benefits with respect to age-related diseases, such as neurodegenerative diseases, age-related macular degeneration, bone metabolism diseases, cardiovascular diseases, cancer, as well as having anti-inflammatory and hepatoprotective functions (33, 36–42).

Figure 1

Oxidative damage and role of quercetin.

Oxidative stress in persistent COVID

The oxidative stress that occurs in COVID-19 is related to the cytokine storm, the coagulation mechanism, and the exacerbation of hypoxia; elevated inflammatory and oxidative state in the pathology triggers mitochondrial oxidative stress and dysfunction, which contributes to dysbiosis or imbalance of the balance of the intestinal microbiota, increasing the inflammatory and oxidative response (43–45). Viral infections alter the antioxidant mechanisms, generating a pro-oxidant action, leading to an unbalanced oxidative-antioxidant state and consequent oxidative cell damage (45). Viral infection through SARS-CoV-2 allows the innate immune system to identify infection through pattern recognition receptors (PRRs); these involve toll-like receptors (TLRs), which trigger a pro-oxidant response of macrophages, resulting in activation of the TNF-α and NADPH-oxidase in leukocytes, as well as mediating the production of reactive oxygen species (ROS) (46). In subjects with persistent COVID, the hyperinflammatory state involves systemic disturbances in the host, such as iron dysregulation that manifests itself as hyperferritinemia associated with disease severity, which induces ROS production promoting oxidative stress (47). The enzyme nitric oxide synthase induces in neutrophils the production of oxygen free radicals capable of combining with nitric oxide (NO) to generate the compound peroxynitrite; neutrophilia generates an excess of ROS that exacerbates the host's immunopathological response, resulting in more severe disease (46, 47).

Quercetin and persistent COVID

Quercetin has antioxidant, anti-inflammatory, anticarcinogenic, and immunoprotective functions because it promotes mitochondrial biogenesis, inhibits lipid peroxidation, inhibits capillary permeability, and inhibits platelet aggregation; in viral infections inhibits the binding of viral capsid proteins and controls the production of proteases and polymerases (48, 49). Specifically, SARS-CoV-2 inhibits enzymes involved in virus replication (49–51). Quercetin alters the expression of 30% of genes encoding SARS-CoV-2 target proteins in human cells, potentially interfering with the activities of 85% of SARS-CoV-2 proteins (52). Quercetin inhibits protein disulfide isomerase (PDI), which is the enzyme involved in platelet-mediated thrombin formation, thus improving the coagulation abnormalities that can be found in subjects with persistent COVID (53). Quercetin has been shown to be an effective inhibitor against several viruses in vitro, such as rhinovirus serotypes, echovirus (type 7, 11, 12 and 19), coxsackievirus (A21 and B1), poliovirus (type 1 Sabin) at a minimum inhibitory concentration of 0.03–0.5 μg/ml in Hela or WI-38 cells (54). Quercetin significantly reduces RNA and DNA replication in herpes simplex virus 1 (HSV-1), parainfluenza type 3, polio type 1, showing anti-infectious and anti-replicative properties (55). Studies have shown that it inhibits HeLa cell replication inoculated with cytomegalovirus (CMV) at a mean inhibitory concentration of 3.2 ± 0.8 μM (56); work has been done on the replication of dengue virus type 2 (DENV-2) in Vero cells and in which Quercetin inhibited at a mean concentration of 35.7 μg/ml, causing a DENV-2 RNA reduction of 67%. This is attributed to the ability to block viral entry or inhibit viral replication enzymes, such as viral polymerases (57, 58). A mixture of Quercetin with Vitamin C can disrupt virus entry, replication, enzymatic activity, and assembly, while seeking to strengthen the immune response by promoting early IFN production, modulating interleukins, promoting T-cell maturation and phagocytic activity (58). Quercetin seeks to inhibit SARS 3CL protease by binding to its GLN189 site, which is expressed similarly in SARS-CoV-2, thus providing the mechanism for its experimental clinical use, in addition to its own immunomodulatory and anti-inflammatory actions (59, 60). It is important to mention that Quercetin can be found in foods and beverages of vegetable origin (grapes, red onion, broccoli, grapefruit, apples, cherries, green tea and red wine), it represents 60%−75% of the total flavonols consumed, its half-life in humans has been estimated to be 31–50 h, with a peak plasma concentration half an hour after consumption and another 8 h after 100 mg ingestion (61). However, the amount of Quercetin contained in the plant is conditioned by several factors: (a) the part of the plant in which it is found, the majority in the external areas; (b) the time of the year in which it develops, in summer and with greater exposure to the sun there will be more flavonoids, warm climates favor the synthesis of Quercetin; (c) the more mature the fruit, the higher the Quercetin content; (d) the process of preparation and processing of the food also has an influence, the fact that cooking these plants can reduce the amount of Quercetin they possess, in addition, it is also lost by removing the skin of the fruit or vegetable. The low bioavailability of Quercetin and its poor solubility are limitations to its use leading to the reduction of the antioxidant power it possesses; restricted transport across biological barriers and transient retention are challenges to overcome, and an alternative to the above is the use of nanotherapy. The use of conjugates and nanocarriers based on different materials is an option to consider for Quercetin; these nanocarriers have been used with natural compounds such as Ginkgo Biloba as well as targeted drugs for neurodegenerative diseases (62–64); these nanoparticles can be organic or inorganic, organic materials (liposomes, micelles, and polymeric nanoparticles) stand out for being compatible and degradable in their entirety. Inorganic nanoparticles (iron oxide nanoparticles, gold nanoparticles, and silica nanoparticles) have smaller size, stability, higher permeability, and a controlled release period (65–67).

Conclusion

In conclusion, we can say that the current prevalence of persistent COVID symptoms is striking, due to oxidative stress that plays an important role in the progression of this pathology. The use of antioxidants for the elimination of free radicals is an appropriate strategy, considering that in recent decades the intake of substances with antioxidant properties, such as quercetin, has increased; this increase in consumption can be achieved through diet or using food supplements with higher concentrations of the flavonoid than those naturally occurring in food. It is worth mentioning the role played by quercetin in the reduction of viral load, decrease in the release of pro-inflammatory cytokines, reduction of ROS, decrease in mucus production, with respect to the above we can say that it increases the resistance of the respiratory tract; moreover, quercetin has not yet shown any harmful effects in humans at a maximum dose of 1,500 mg per day.

Statements

Author contributions

DM-P: Investigation, Writing—original draft. CA-E: Investigation, Writing—original draft, Formal analysis, Methodology. AG-M: Formal analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Writing—original draft. KG-M: Formal analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Writing—original draft. EH-B: Investigation, Methodology, Writing—review & editing. IG-M: Investigation, Conceptualization, Supervision, Writing—original draft.

Funding

The author(s) declare that no financial support was received for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

1.

CebanFLingSLuiLMWLeeYGillHTeopizKMet al. Fatigue and cognitive impairment in post-Covid-19 syndrome: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Brain Behav Immun. (2022) 101:93–135. 10.1016/j.bbi.2021.12.020

2.

AlkodaymiMSOmraniOAFawzyNAShaarBAAlmamloukRRiazMet al. Prevalence of post-acute COVID-19 syndrome symptoms at different follow-up periods: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Clin Microbiol Infect. (2022) 28:657–66. 10.1016/j.cmi.2022.01.014

3.

López-SampaloABernal-LópezMRGómez-HuelgasR. Persistent Covid-19 syndrome. A narrative review. Rev Clin Esp. (2022) 222:241–50. 10.1016/j.rce.2021.10.003

4.

Al-HakeimHKAl-RubayeHTAl-HadrawiDSAlmullaAFMaesM. Long-COVID post-viral chronic fatigue and affective symptoms are associated with oxidative damage, lowered antioxidant defenses and inflammation: a proof of concept and mechanism study. Mol Psychiatry. (2023) 28:564–78. 10.1038/s41380-022-01836-9

5.

SwankZSenussiYManickas-HillZYuXGLiJZAlterGet al. Persistent circulating severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 spike is associated with post-acute coronavirus disease 2019 sequelae. Clin Infect Dis. (2023) 76:e487–90. 10.1093/cid/ciac722

6.

ProalADVanElzakkerMB. Long COVID or post-acute sequelae of COVID-19 (PASC): an overview of biological factors that may contribute to persistent symptoms. Front Microbiol. (2021) 12:698169. 10.3389/fmicb.2021.698169

7.

AntonelliMPenfoldRSCanasLDSSudreCRjoobKMurrayBet al. SARS-CoV-2 infection following booster vaccination: illness and symptom profile in a prospective, observational community-based case-control study. J Infect. (2023) 87:506–15. 10.1016/j.jinf.2023.08.009

8.

KleinJWoodJJaycoxJLuPDhodapkarRMGehlhausenJRet al. Distinguishing features of long COVID identified through immune profiling. medRxiv. (2022). 10.1101/2022.08.09.22278592

9.

GlynnePTahmasebiNGantVGuptaR. Long COVID following mild SARS-CoV-2 infection: characteristic T cell alterations and response to antihistamines. J Investig Med. (2022) 70:61–7. 10.1136/jim-2021-002051

10.

PhetsouphanhCDarleyDRWilsonDBHoweAMunierCMLPatelSKet al. Immunological dysfunction persists for 8 months following initial mild-to-moderate SARS-CoV-2 infection. Nat Immunol. (2022) 23:210–16. 10.1038/s41590-021-01113-x

11.

ZubchenkoSKrilINadizhkoOMatsyuraOChopyakV. Herpesvirus infections and post-COVID-19 manifestations: a pilot observational study. Rheumatol Int. (2022) 42:1523–30. 10.1007/s00296-022-05146-9

12.

PelusoMJDeveauTMMunterSERyderDBuckALuSet al. Evidence of recent Epstein-Barr virus reactivation in individuals experiencing long Covid. medRxiv. (2022). [Preprint]. 10.1101/2022.06.21.22276660

13.

YeohYKZuoTLuiGCZhangFLiuQLiAYet al. Gut microbiota composition reflects disease severity and dysfunctional immune responses in patients with COVID-19. Gut. (2021) 70:698–706. 10.1136/gutjnl-2020-323020

14.

LiuQMakJWYSuQYeohYKLuiGCNgSSSet al. Gut microbiota dynamics in a prospective cohort of patients with post-acute COVID-19 syndrome. Gut. (2022) 71:544–52. 10.1136/gutjnl-2021-325989

15.

Mendes de AlmeidaVEngelDFRicciMFCruzCSLopesÍSAlvesDAet al. Gut microbiota from patients with COVID-19 cause alterations in mice that resemble post-COVID symptoms. Gut Microbes. (2023) 15:2249146. 10.21203/rs.3.rs-1756189/v2

16.

WallukatGHohbergerBWenzelKFürstJSchulze-RotheSWallukatAet al. Functional autoantibodies against G-protein coupled receptors in patients with persistent long-COVID-19 symptoms. J Transl Autoimmun. (2021) 4:100100. 10.1016/j.jtauto.2021.100100

17.

SuYYuanDChenDGNgRHWangKChoiJet al. Multiple early factors anticipate post-acute COVID-19 sequelae. Cell. (2022) 185:881–95.e20. 10.1016/j.cell.2022.01.014

18.

ArthurJMForrestJCBoehmeKWKennedyJLOwensSHerzogCet al. Development of ACE2 autoantibodies after SARS-CoV-2 infection. PLoS ONE. (2021) 16:e0257016. 10.1371/journal.pone.0257016

19.

HaffkeMFreitagHRudolfGSeifertMDoehnerWScherbakovNet al. Endothelial dysfunction and altered endothelial biomarkers in patients with post-COVID-19 syndrome and chronic fatigue syndrome (ME/CFS). J Transl Med. (2022) 20:138. 10.1186/s12967-022-03346-2

20.

CharfeddineSIbn Hadj AmorHJdidiJTorjmenSKraiemSHammamiRet al. Long COVID 19 syndrome: is it related to microcirculation and endothelial dysfunction? insights from TUN-EndCOV study. Front Cardiovasc Med. (2021) 8:745758. 10.3389/fcvm.2021.745758

21.

PretoriusEVenterCLaubscherGJKotzeMJOladejoSOWatsonLRet al. Prevalence of symptoms, comorbidities, fibrin amyloid microclots and platelet pathology in individuals with long COVID/post-acute sequelae of COVID-19 (PASC). Cardiovasc Diabetol. (2022) 21:148. 10.1186/s12933-022-01579-5

22.

SpudichSNathA. Nervous system consequences of COVID-19. Science. (2022) 375:267–9. 10.1126/science.abm2052

23.

DavisHEMcCorkellLVogelJMTopolEJ. Long COVID: major findings, mechanisms and recommendations. Nat Rev Microbiol. (2023) 21:133–46. 10.1038/s41579-022-00846-2

24.

PaulBDLemleMDKomaroffALSnyderSH. Redox imbalance links Covid-19 and myalgic encephalomyelitis/chronic fatigue syndrome. Proc Nat Acad Sci. (2021) 118:1–10. 10.1073/pnas.2024358118

25.

QannetaR. Long COVID-19 and myalgic encephalomyelitis/chronic fatigue syndrome: similarities and differences of two peas in a pod. Reumatol Clín. (2022) 18:626–27. 10.1016/j.reuma.2022.05.003

26.

SorianoJBAncocheaJ. On the new post Covid condition. Arch Bronconeumol. (2021) 57:735–6. 10.1016/j.arbr.2021.10.011

27.

NijveldtRJvan NoodEvan HoornDEBoelensPGvan NorrenKvan LeeuwenPAet al. Flavonoids: a review of probable mechanisms of action and potential applications. Am J Clin Nutr. (2001) 74:418–25. 10.1093/ajcn/74.4.418

28.

AlugojuPPeriyasamyLDyavaiahM. Protective effect of quercetin in combination with caloric restriction against oxidative stress-induced cell death of Saccharomyces cerevisiae cells. Lett Appl Microbiol. (2020) 71:272–79. 10.1111/lam.13313

29.

SulOJRaSW. Quercetin prevents LPS-induced oxidative stress and inflammation by modulating NOX2/ROS/NF-kB in lung epithelial cells. Molecules. (2021) 26:6949. 10.3390/molecules26226949

30.

KashyapDGargVKTuliHSYererMBSakKSharmaAKet al. Fisetin and quercetin: promising flavonoids with chemopreventive potential. Biomolecules. (2019) 9:174. 10.3390/biom9050174

31.

ChenTZhangXZhuGLiuHChenJWangYet al. Quercetin inhibits TNF-α induced HUVECs apoptosis and inflammation via downregulating NF-kB and AP-1 signaling pathway in vitro. Medicine. (2020) 99:e22241. 10.1097/MD.0000000000022241

32.

ShabbirURubabMDaliriEBChelliahRJavedAOhDHet al. Curcumin, quercetin, catechins and metabolic diseases: the role of gut microbiota. Nutrients. (2021) 13:206. 10.3390/nu13010206

33.

DeepikaMauryaPK. Health benefits of quercetin in age-related diseases. Molecules. (2022) 27:2498. 10.3390/molecules27082498

34.

HosseiniARazaviBMBanachMHosseinzadehH. Quercetin and metabolic syndrome: a review. Phytother Res. (2021) 35:5352–64. 10.1002/ptr.7144

35.

MahadevMNandiniHSRamuRGowdaDVAlmarhoonZMAl-GhorbaniMet al. Fabrication and evaluation of quercetin nanoemulsion: a delivery system with improved bioavailability and therapeutic efficacy in diabetes mellitus. Pharmaceuticals. (2022) 15:70. 10.3390/ph15010070

36.

AmanzadehEEsmaeiliARahgozarSNourbakhshniaM. Application of quercetin in neurological disorders: from nutrition to nanomedicine. Rev Neurosci. (2019) 30:555–72. 10.1515/revneuro-2018-0080

37.

ShamsiAShahwanMKhanMSHusainFMAlhumaydhiFAAljohaniASMet al. Elucidating the interaction of human ferritin with quercetin and naringenin: implication of natural products in neurodegenerative diseases: molecular docking and dynamics simulation insight. ACS Omega. (2021) 6:7922–30. 10.1021/acsomega.1c00527

38.

InchingoloADInchingoloAMMalcangiGAvantarioPAzzolliniDBuongiornoSet al. Effects of resveratrol, curcumin and quercetin supplementation on bone metabolism-a systematic review. Nutrients. (2022) 14:3519. 10.3390/nu14173519

39.

BanezMJGeluzMIChandraAHamdanTBiswasOSBryanNSet al. A systemic review on the antioxidant and anti-inflammatory effects of resveratrol, curcumin, and dietary nitric oxide supplementation on human cardiovascular health. Nutr Res. (2020) 78:11–26. 10.1016/j.nutres.2020.03.002

40.

WardABMirHKapurNGalesDNCarrierePPSinghSet al. Quercetin inhibits prostate cancer by attenuating cell survival and inhibiting anti-apoptotic pathways. World J Surg Oncol. (2018) 16:108. 10.1186/s12957-018-1400-z

41.

CioneELa TorreCCannataroRCaroleoMCPlastinaPGallelliLet al. Quercetin, epigallocatechin gallate, curcumin, and resveratrol: from dietary sources to human microRNA modulation. Molecules. (2019) 25:63. 10.3390/molecules25010063

42.

HamzaRZAl-ThubaitiEHOmarAS. The antioxidant activity of quercetin and its effect on acrylamide hepatotoxicity in liver of rats. Lat Am J Pharm. (2019) 38:2057–62.

43.

CecchiniBLourenço-CecchiniA. SARS-CoV-2 infection pathogenesis is related to oxidative stress as a response to aggression. Med Hypotheses. (2020) 143:110102. 10.1016/j.mehy.2020.110102

44.

SalehJPeyssonnauxCSinghKKEdeasM. Mitochondria and microbiota dysfunction in the pathogenesis of COVID-19. Mitochondrion. (2020) 54:1–7. 10.1016/j.mito.2020.06.008

45.

Delgado-RocheLMestaF. Oxidative stress as a key player in severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus (SARS-CoV) infection. Arch Med Res. (2020) 51:384–87. 10.1016/j.arcmed.2020.04.019

46.

FirasRMazharAGhenaKDuniaSAmjadA. SARS-CoV2 and coronavirus disease 2019: what we know so far. Pathogens. (2020) 9:231. 10.3390/pathogens9030231

47.

EdeasMSalehJPeyssonnauxC. Iron: innocent or vicious bystander guilty of COVID-19 pathogenesis?Int J Infect Dis. (2020) 97:303–05. 10.1016/j.ijid.2020.05.110

48.

Di PetrilloAOrruGFaisAFantiniMC. Quercetin and its derivates as antiviral potentials: a comprehensive review. Phytother Res. (2022) 36:266–78. 10.1002/ptr.7309

49.

CatalanoAIacopettaDCeramellaJMaioACBasileGGiuzioFet al. Are nutraceuticals effective in COVID-19 and post-COVID prevention and treatment?Foods. (2022) 11:2884. 10.3390/foods11182884

50.

MoustaqilMOllivierEChiuHPVan TolSRudolffi-SotoPStevensCet al. SARS-CoV-2 proteases PLpro and 3CLpro cleave IRF3 and critical modulators of inflammatory pathways (NLRP12 and TAB1): implications for disease presentation across species. Emerg Microbes Infect. (2021) 10:178–95. 10.1080/22221751.2020.1870414

51.

NguyenTTHWooHJKangHKNguyenVDKimYMKimDWet al. Flavonoid-mediated inhibition of SARS coronavirus 3C-like protease expressed in Pichia pastoris. Biotechnol Lett. (2012) 34:831–38. 10.1007/s10529-011-0845-8

52.

GlinskyGV. Tripartite combination of candidate pandemic mitigation agents: vitamin D, quercetin, and estradiol manifest properties of medicinal agents for targeted mitigation of the COVID-19 pandemic defined by genomics-guided tracing of SARS-CoV-2 targets in human cells. Biomedicines. (2020) 8:129. 10.3390/biomedicines8050129

53.

SalamannaFMaglioMLandiniMPFiniM. Platelet functions and activities as potential hematologic parameters related to coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19). Platelets. (2020) 31:627–32. 10.1080/09537104.2020.1762852

54.

IshitsukaHOhsawaCOhiwaTUmedaISuharaY. Antipicornavirus flavone Ro 09-0179. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. (1982) 22:611–6. 10.1128/AAC.22.4.611

55.

KaulTNMiddleton EJrOgraPL. Antiviral effect of flavonoids on human viruses. J Med Virol. (1985) 15:71–9. 10.1002/jmv.1890150110

56.

EversDLChaoCFWangXZhangZHuongSMHuangESet al. Human cytomegalovirus-inhibitory flavonoids: studies on antiviral activity and mechanism of action. Antiviral Res. (2005) 68:124–34. 10.1016/j.antiviral.2005.08.002

57.

ZandiKTeohBTSamSSWongPFMustafaMRAbubakarSet al. Antiviral activity of four types of bioflavonoid against dengue virus type-2. Virol J. (2011) 8:560. 10.1186/1743-422X-8-560

58.

Colunga BiancatelliRMLBerrillMCatravasJDMarikPE. Quercetin and vitamin C: an experimental, synergistic therapy for the prevention and treatment of SARS-CoV-2 related disease (COVID-19). Front Immunol. (2020) 11:1451. 10.3389/fimmu.2020.01451

59.

ChenLLiJLuoCLiuHXuWChenGet al. Binding interaction of quercetin-3-beta-galactoside and its synthetic derivatives with SARS-CoV 3CL(pro): structure-activity relationship studies reveal salient pharmacophore features. Bioorg Med Chem. (2006) 14:8295–306. 10.1016/j.bmc.2006.09.014

60.

ZhangLLinDSunXCurthUDrostenCSauerheringLet al. Crystal structure of SARS-CoV-2 main protease provides a basis for design of improved α-ketoamide inhibitors. Science. (2020) 368:409–12. 10.1126/science.abb3405

61.

Vicente-VicenteLPrietoMMoralesAI. Efficacy and safety of quercetin as a dietary supplement. Rev Toxicol. (2013) 30:171–81.

62.

AkanchiseTAngelovaA. Ginkgo biloba and long COVID: in vivo and in vitro models for the evaluation of nanotherapeutic efficacy. Pharmaceutics. (2023) 15:1562. 10.3390/pharmaceutics15051562

63.

SonvicoFClementinoAButtiniFColomboGPescinaSStanisçuaski GuterresSet al. Surface-modified nanocarriers for nose-to-brain delivery: from bioadhesion to targeting. Pharmaceutics. (2018) 10:34. 10.3390/pharmaceutics10010034

64.

LeeDMinkoT. Nanotherapeutics for nose-to-brain drug delivery: an approach to bypass the blood brain barrier. Pharmaceutics. (2021) 13:2049. 10.3390/pharmaceutics13122049

65.

AkanchiseTAngelovaA. Potential of nano-antioxidants and nanomedicine for recovery from neurological disorders linked to long COVID syndrome. Antioxidants. (2023) 12:393. 10.3390/antiox12020393

66.

PoonCPatelA. Organic and inorganic nanoparticle vaccines for prevention of infectious diseases. Nano Express. (2020) 1:012001. 10.1088/2632-959X/ab8075

67.

Giner-CasaresJJHenriksen-LaceyMCoronado-PuchauMLiz-MarzánLM. Inorganic nanoparticles for biomedicine: where materials scientists meet medical research. Mater Today. (2016) 19:19–28. 10.1016/j.mattod.2015.07.004

Summary

Keywords

COVID-19, ROS, flavonoids, quercetin, post-pandemia

Citation

Matías-Pérez D, Antonio-Estrada C, Guerra-Martínez A, García-Melo KS, Hernández-Bautista E and García-Montalvo IA (2024) Relationship of quercetin intake and oxidative stress in persistent COVID. Front. Nutr. 10:1278039. doi: 10.3389/fnut.2023.1278039

Received

16 August 2023

Accepted

26 December 2023

Published

08 January 2024

Volume

10 - 2023

Edited by

Germano Guerra, University of Molise, Italy

Reviewed by

Angelina Angelova, UMR8612 Institut Galien Paris Sud (IGPS), France

Updates

Copyright

© 2024 Matías-Pérez, Antonio-Estrada, Guerra-Martínez, García-Melo, Hernández-Bautista and García-Montalvo.

This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Iván Antonio García-Montalvo ivan.garcia@itoaxaca.edu.mx

Disclaimer

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.