- 1Division of Epidemiology and Public Health, University of Nottingham, Nottingham, United Kingdom

- 2The Nottingham Centre for Evidence-Based Healthcare: A Joanna Briggs Institute Centre of Excellence, Nottingham, United Kingdom

- 3Centre for Chronic Disease Control, New Delhi, India

- 4Swami Vivekananda Yoga Anusandhana Samsthana, Bengaluru, India

- 5Population Health Research Institute, St. George's University of London, London, United Kingdom

- 6Division of Surgery and Interventional Science, Institute Sport Exercise and Health, University College London, London, United Kingdom

- 7Institute of Applied Health Research, University of Birmingham, Birmingham, United Kingdom

- 8Department of Endocrinology, Metabolism and Diabetes, All India Institute of Medical Sciences, New Delhi, India

- 9London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine, London, United Kingdom

Introduction: Many Indians are at high-risk of type-2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM). Yoga is an ancient Indian mind-body discipline, that has been associated with improved glucose levels and can help to prevent T2DM. The study aimed to systematically develop a Yoga program for T2DM prevention (YOGA-DP) among high-risk people in India using a complex intervention development approach.

Materials and Methods: As part of the intervention, we developed a booklet and a high-definition video for participants and a manual for YOGA-DP instructors. A systematic iterative process was followed to develop the intervention and included five steps: (i) a systematic review of the literature to generate a list of Yogic practices that improves blood glucose levels among adults at high-risk of or with T2DM, (ii) validation of identified Yogic practices by Yoga experts, (iii) development of the intervention, (iv) consultation with Yoga, exercise, physical activity, diet, behavior change, and/or diabetes experts about the intervention, and (v) pretest the intervention among Yoga practitioners and lay people (those at risk of T2DM and had not practiced Yoga before) in India.

Results: YOGA-DP is a structured lifestyle education and exercise program, provided over a period of 24 weeks. The exercise part is based on Yoga and includes Shithilikarana Vyayama (loosening exercises), Surya Namaskar (sun salutation exercises), Asana (Yogic poses), Pranayama (breathing practices), and Dhyana (meditation) and relaxation practices. Once participants complete the program, they are strongly encouraged to maintain a healthy lifestyle in the long-term.

Conclusions: We systematically developed a novel Yoga program for T2DM prevention (YOGA-DP) among high-risk people in India. A multi-center feasibility randomized controlled trial is in progress in India.

Introduction

India has the second-largest type-2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM) population in the world, a disorder with major health and socioeconomic consequences (1). More than 77 million Indians are at high-risk of T2DM—their blood glucose levels are higher than normal but lower than the established threshold for T2DM itself (2). These people are more likely to develop T2DM and its complications than those with normal blood glucose levels (3). Unhealthy lifestyle (i.e., physical inactivity and unhealthy diet) is a major risk factor for T2DM (3). Physical activity levels are low among Indians (4). Similarly, unhealthy diets, high in fat (especially saturated fat) and low in fiber, are more prevalent among Indians (5, 6). Screening of people who are at high-risk of T2DM, followed by an effective lifestyle intervention is a cost-effective approach that can normalize blood glucose levels and has other health benefits (3, 7, 8).

Health interventions should be informed by and compatible with the sociocultural expectations of people and their health beliefs (9). The prevention and management of chronic diseases like T2DM using traditional Indian therapies have been prioritized by the Indian government (10). Yoga, an ancient Indian mind-body discipline, covers not only physical activity but also a healthy diet (11). Many different styles of Yoga are undertaken, focusing on similar core elements of physical, mental, and spiritual practices. No particular style of Yoga is necessarily better or more authentic than the others (12). Indians usually have high acceptability of Yoga because it fits their health beliefs and culture (13, 14). Generally, it uses a gentle approach, is easy to learn, is safe, requires a low to moderate level of guidance, is inexpensive to maintain, and can be practiced indoors and outdoors (13). It can be practiced by older adults and those with a wide range of comorbidities (12, 13). As a form of physical activity, some of the Yogic practices are of low-intensity (<3.5 kcal/min) and some are of moderate-intensity (3.5–7.0 kcal/min) (12, 15). For example, Surya Namaskar (sun salutation exercises) burns about 3.8–6.7 kcal/min (16, 17). Yoga is also a muscle-strengthening activity (12). Thus, it can contribute to the aim of routine lifestyle advice given to people at high-risk of T2DM to prevent it.

The beneficial effects of Yoga on T2DM-related risk profiles appear to occur via two main pathways. First, by reducing the activation and reactivity of the sympathoadrenal system and the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis and by promoting the feelings of well-being, Yoga may alleviate the effects of stress and foster multiple positive downstream effects on the neuroendocrine status, metabolic function, and related systemic inflammatory responses (18). Second, by directly stimulating the vagus nerve, Yoga may enhance the parasympathetic activity and lead to positive changes in the cardiovagal function, mood, energy state, and related neuroendocrine, metabolic, and inflammatory responses (18). In addition, Yoga may lead to weight loss, which itself lowers the risk of T2DM (18).

The beneficial effects of Yoga on T2DM-related outcomes in T2DM (as adjuvant therapy) and metabolic syndrome have been reported in several systematic reviews of clinical trials (19–22). For example, a review of 44 randomized controlled trials (RCTs), conducted among T2DM, metabolic syndrome, or healthy participants (n = 3,168), found that Yoga improves blood glucose levels compared to usual care or no intervention (mean difference = −0.45%; 95% confidence interval = −0.87 to −0.02), without any major safety issues (19). However, most of the included studies were short-term (≤ 3 months) and were often associated with considerable methodological limitations, such as small sample sizes in treatment groups, resulting in lack of statistical power for outcome assessment, and lack of blinding of outcome assessors, leading to potential analysis bias. In addition, some of the relevant previous studies have not described the intervention in detail, and it is difficult to replicate successful interventions. Most studies have not reported the intervention development process. It is hard to know whether these interventions were carefully thought out (e.g., their safety and acceptability) and comprehensive in their development. Thus, it is difficult to select (and replicate) one successful intervention over the other. Another selection barrier is their heterogeneous contents (i.e., different Yogic practices were included in these interventions), which needed to be summarized for utilization in T2DM prevention. Thus, our study aimed to address these issues by systematically developing a Yoga program for T2DM prevention (YOGA-DP) among high-risk people in India.

Materials and Methods

We followed a systematic iterative process to develop the intervention, guided by the UK's Medical Research Council (MRC) guidance on developing and evaluating complex interventions and Sherman's guideline for developing Yoga interventions for RCTs (9, 23). The template for intervention description and replication (TIDieR) checklist and guide were used to report the intervention (24). As part of the intervention, we developed a booklet and a high-definition video for participants and a manual for YOGA-DP instructors. An external filmmaking company was hired to convert the booklet (Yoga part) into a video to aid audio-visual learning. It was decided to use USB flash drives (having a compressed video—2.08 gigabyte (GB) in MPEG-4 Part 14 (MP4) file format) after discussing the technological advancements as well as accessibility issues in India with the relevant stakeholders (e.g., those in the field of film making). All these are available in English and two other Indian languages, Hindi and Kannada.

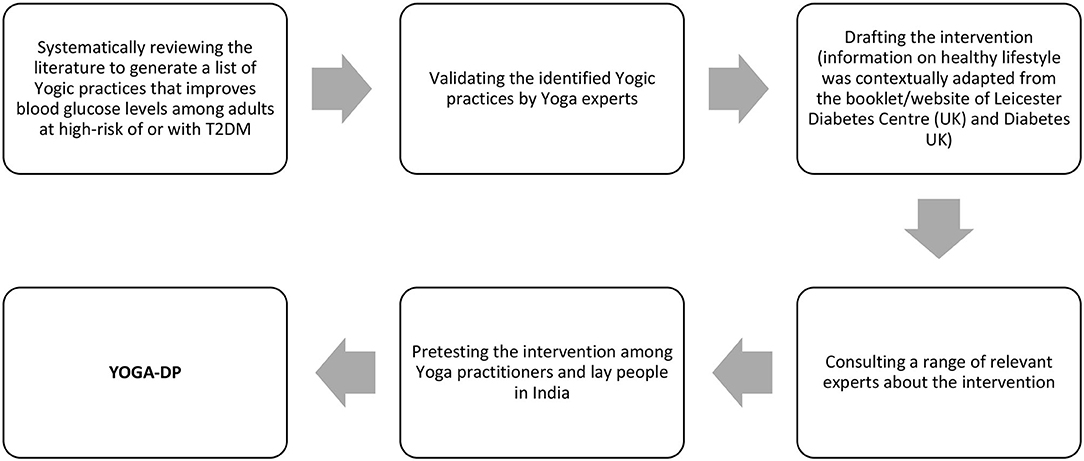

Figure 1 shows the development process of YOGA-DP, which consisted of five steps:

(1) We conducted a systematic review of scientific literature to generate a list of Yogic practices that improves blood glucose levels among adults at high-risk of or with T2DM. The PROSPERO protocol informed the systematic review process (PROSPERO registration number CRD42018097216) (25). The process was guided by the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) documents (26). Two Joanna Briggs Institute (JBI) accredited systematic reviewers (KC/HW) were involved in the process and independently screened the titles and abstracts and full-text of studies, assessed the methodological quality of studies, and extracted data from the studies. Any disagreements between them were resolved through discussion.

Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

Population, intervention, comparator, and outcome: Studies targeting adults (≥18 years) at high-risk of or with T2DM were eligible. The diagnosis was based on blood glucose levels. Studies comparing Yoga intervention to no or any intervention and reporting successful Yoga interventions were eligible i.e., Yogic practices which improved blood glucose levels. At least one of the following needed to be statistically significant in the Yoga intervention group as compared to the control group: fasting blood glucose (FBG), postprandial blood glucose (PPBG), or glycated hemoglobin (HbA1c). Studies reporting at least one Yogic practice (i.e., Asana (Yogic pose), Pranayama (breathing practice), or Dhyana (meditation) and relaxation practice), based on classical Yoga texts, were eligible. Studies were excluded if they did not report the Sanskrit name of the Yogic practice. No restrictions were made regarding the frequency or duration of the Yoga intervention. Studies on multimodal interventions that included Yoga amongst others were excluded. Studies allowing individual co-interventions were eligible i.e., studies allowing participants to continue their individual treatment were not excluded as long as all the study groups were allowed to do so.

Study design: Only RCTs were eligible.

Language of publication: No language restrictions were applied.

Search Strategy

(a) Using existing full-text peer-reviewed systematic reviews as a starting point for identifying the relevant RCTs (and interventions), systematic reviews were searched on PubMed from its inception date to 7th May 2018. The systematic review authors (reviewers) searched a range of databases, the reference list of identified original and review articles, and the table of contents of relevant journals, trial registers, proceedings, and abstracts from relevant symposiums, conferences, and colloquiums. These systematic review authors also approached the relevant experts. The search strategy used was: (Yoga[MeSH] OR Yoga*[tiab] OR Yogi*[tiab] OR Asana* [tiab] OR Pranayam* [tiab] OR Dhyan* [tiab]) AND systematic[sb].

(b) To supplement the above step, we searched on PubMed to directly identify any full-text peer-reviewed RCTs that were published between 1st January 2015 and 7th May 2018. The search strategy used was: (Yoga[MeSH] OR Yoga*[tiab] OR Yogi*[tiab] OR Asana* [tiab] OR Pranayam* [tiab] OR Dhyan* [tiab]) AND random*[mp] NOT systematic[sb].

(c) We also searched IndMED and Google Scholar for additional systematic reviews and RCTs, using different words for Yoga, prediabetes, diabetes, systematic review, and RCT. For Google Scholar, the advanced search tool was used (with all of the words in the title of the article) and excluded patents and citations. The reference list of all the relevant RCTs was also screened for additional RCTs.

Screening and Full-Text Reading

Following the search, all identified citations were collated and uploaded into EndNote X8.2, a reference management software (27). Titles and abstracts were screened for eligibility using the inclusion and exclusion criteria. The full-texts of studies identified as potentially eligible or those without an abstract were retrieved and assessed against the inclusion and exclusion criteria. The full-texts of studies that did not meet the inclusion criteria were excluded, and the reasons for exclusion were reported (Supplementary Table 1).

Methodological Quality Assessment

In terms of methodological quality of the included RCTs, the following were assessed: randomization method, allocation concealment, blinding of outcome assessors, and withdrawals and dropouts. The Jadad score was also calculated. The Jadad score ranges from zero to five points—two points are given for randomization, two points for blinding, and one point for dropouts (28). A low-quality study receives a score of two points or less, and a high-quality study receives a score of at least three points (28). The Jadad score is easy to use, contains many of the important elements that have empirically been shown to correlate with bias, and has known reliability and external validity (29). Data were extracted and synthesized from all the included RCTs, regardless of their methodological quality.

Data Extraction

Study characteristics of the included RCTs and the intervention details were extracted using a standardized data extraction tool.

Data Synthesis

Narrative data synthesis was conducted as the aim of the systematic review was to generate a list of Yogic practices that improves blood glucose levels among adults at high-risk of or with T2DM.

(2) We required at least 40 Yoga experts (41 responders) to validate each of the identified Yogic practices, based on Lawshe's content validity ratio (CVR) formula (30). Highly qualified and experienced Yoga practitioners and/or Yoga researchers with an interest in diabetes (including those with high-level authority) were purposively selected in India for this purpose. One of the study authors (NKM) is a key person in the field of Yoga, and this helped us to gain access to these Yoga experts. A questionnaire with all the identified practices was administered electronically through email, and they marked the content validity of each practice on a three-point scale (zero = not necessary, one = useful but not essential, two = essential), taking into account the safety aspect. CVR was calculated for each practice but only those with CVR ≥ 0.29 were included in the intervention (30, 31).

Where,

ne = number of experts indicating “essential”

N = total number of experts.

(3) We drafted the intervention, with texts and pictorials. With permission, the information on being at high-risk of T2DM and how to prevent T2DM by being more physically active, keeping a healthy weight, eating less fat (especially saturated fat), and eating more fiber was extracted from an existing booklet of Leicester Diabetes Centre (UK) and the Diabetes UK website and adapted to the Indian context (32, 33). Any traditional advice which is based on anecdotal (or contradictory) evidence was not included in the intervention e.g., dietary advice to consume ghee, a type of clarified butter composed almost entirely of fat, especially saturated fat.

(4) We conducted a consultation on the intervention with 16 experts in Yoga, exercise, physical activity, diet, behavior change, and/or diabetes from India and the UK. Like step number two, we used our multidisciplinary team's contact to approach these experts. The intervention was shared with them through email, and they further reviewed its structure and content, especially from the safety point of view. Their feedback (through email) was used to improve it.

(5) We pre-tested the intervention among eight Yoga practitioners (teachers) and six lay people (those at risk of T2DM and had not practiced Yoga before) at Swami Vivekananda Yoga Anusandhana Samsthana (S-VYASA), India. The objectives were to identify any difficulties they had in reading and understanding the intervention (i.e., comprehension of content/instructions) and to explore the acceptability of the intervention and ways to promote its uptake and adherence. In addition, Yoga practitioners were asked about the overall sequence and flow of the intervention and any difficulties they had in delivering the intervention, especially within the intended timeframe. They were purposively selected to ensure representation of diversity by age and sex. The intervention was shared with them prior to the following activities—to enable them to read and understand it in their free time:

(a) Yoga practitioners: A face-to-face meeting was held with them.

(b) Lay people: A Yoga session, based on the intervention, was delivered to them by two Yoga practitioners (one male and one female). This was followed by a face-to-face meeting with them.

With consent, the feedback was noted and digitally-recorded. Their feedback was used to finalize the intervention.

Results

The results describe the outcome of each step of the intervention development process.

(1) A total of nine RCTs were included in our systematic review. Supplementary Figure 1 shows the flowchart depicting the search and screening process of systematic reviews and RCTs.

(a) 501 systematic review records were identified until 7th May 2018. 468 records were excluded at the title and abstract screening stage. The full-texts of 33 systematic reviews were assessed for eligibility and 21 were excluded at this stage. The remaining 12 systematic reviews were included containing potential RCTs (19, 21, 22, 34–42). The full-texts of 67 potential RCTs were assessed for eligibility and 58 were excluded at this stage. The remaining eight RCTs (two similar articles from the same RCT were published in two different journals) were included in our systematic review (43–51).

(b) To supplement the above step, 384 RCT records were directly identified between 1st January 2015 and 7th May 2018. 374 records were excluded at the title and abstract screening stage. The full-texts of 10 RCTs were assessed for eligibility and nine were excluded at this stage. The remaining one RCT was included in our systematic review (52).

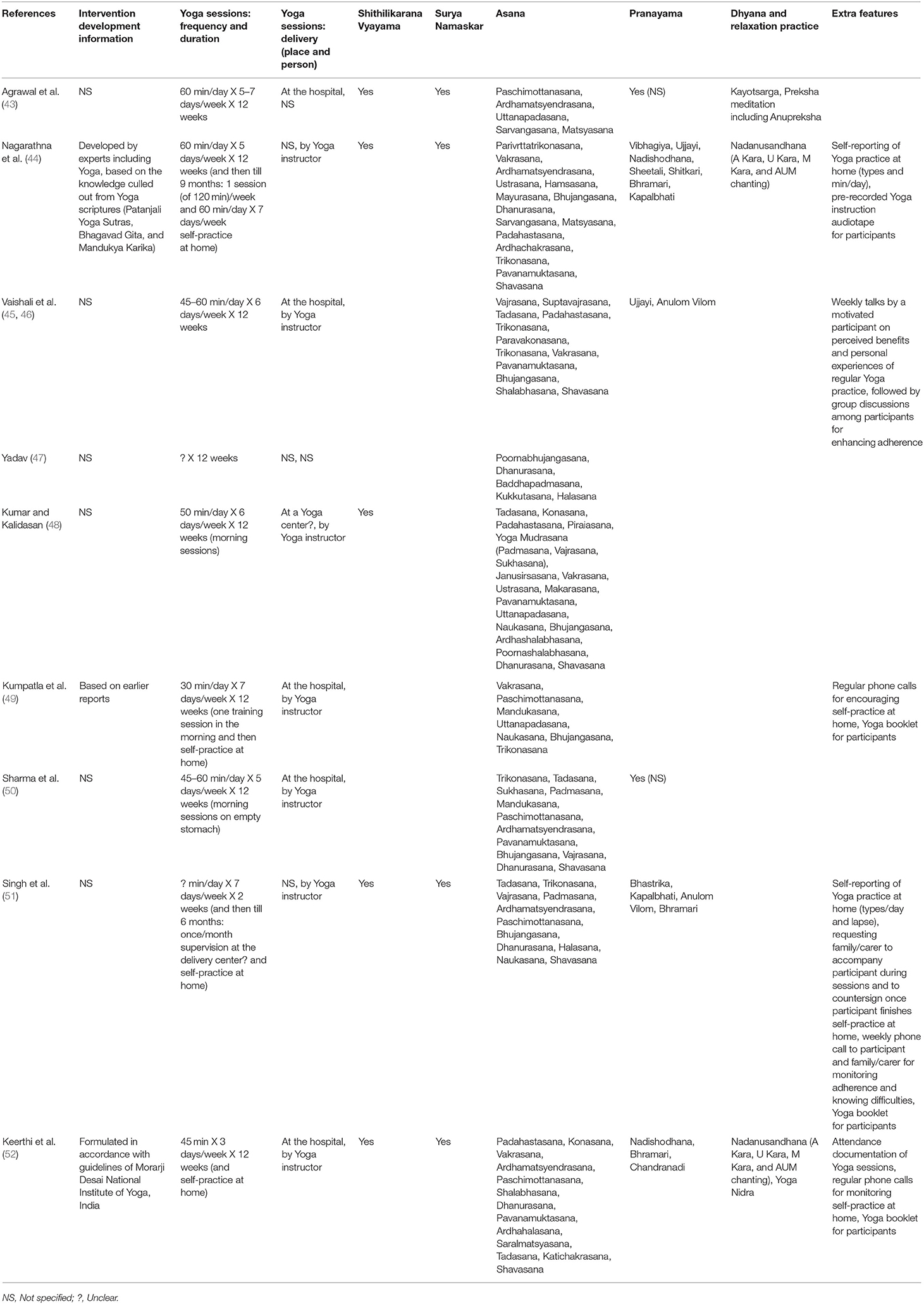

Supplementary Tables 2, 3 report the study characteristics and critical appraisal of the nine included RCTs, respectively. Briefly, all the RCTs were conducted in India. The sample size ranged from 30 to 337. Yoga was an adjuvant therapy in all the RCTs—all the RCTs were conducted among T2DM patients and one study also included people with prediabetes. The improvement in blood glucose levels was measured using FBG, PPBG, and/or HbA1c tests. One RCT mentioned that no adverse event occurred and four reported limited information on adverse events. The Jadad score of only four RCTs was high. Only four RCTs mentioned the allocation concealment (two provided only limited information). Table 1 reports the intervention details of the included RCTs. More specifically, 58 Yogic practices that improve blood glucose levels among adults at high-risk of or with T2DM were identified.

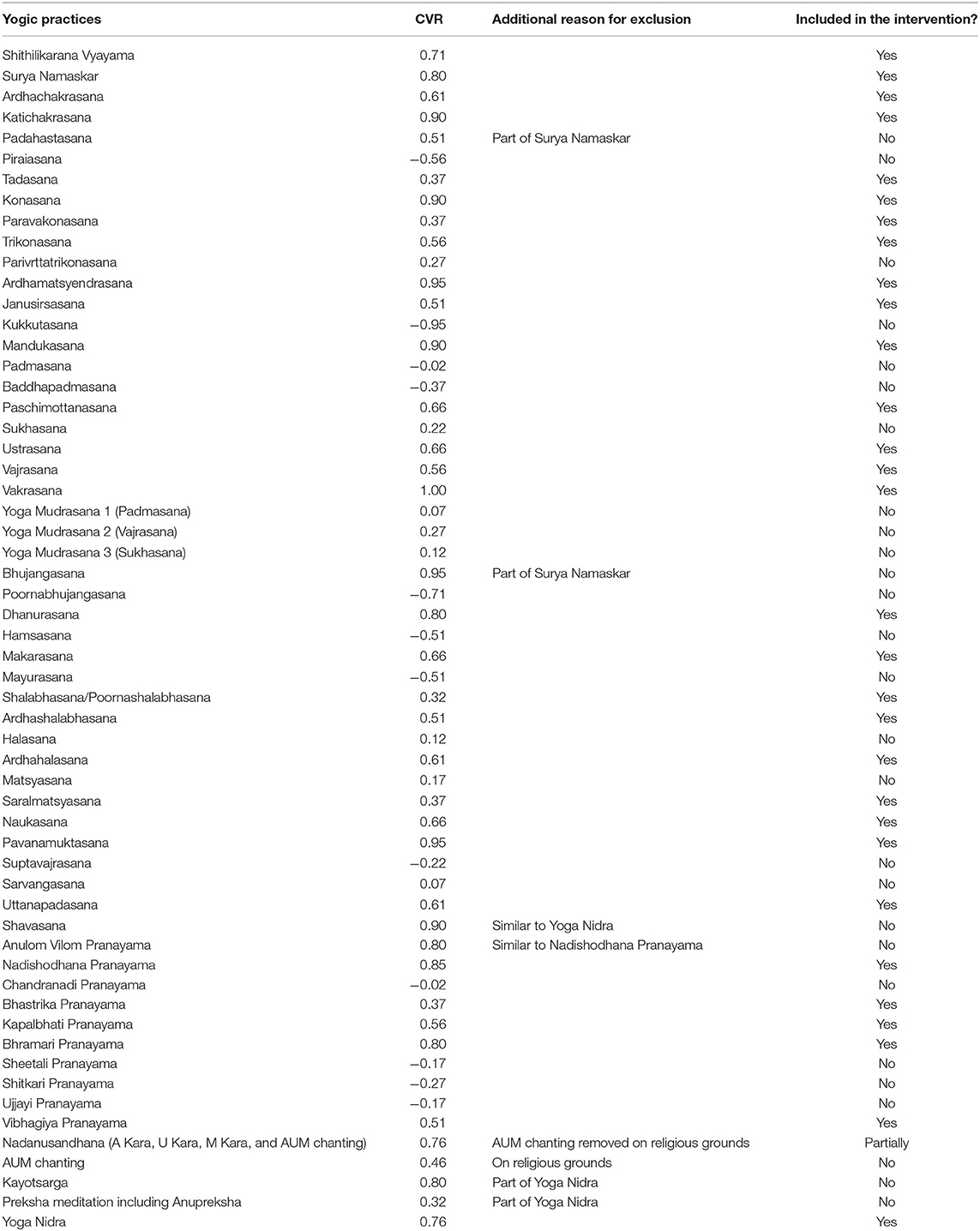

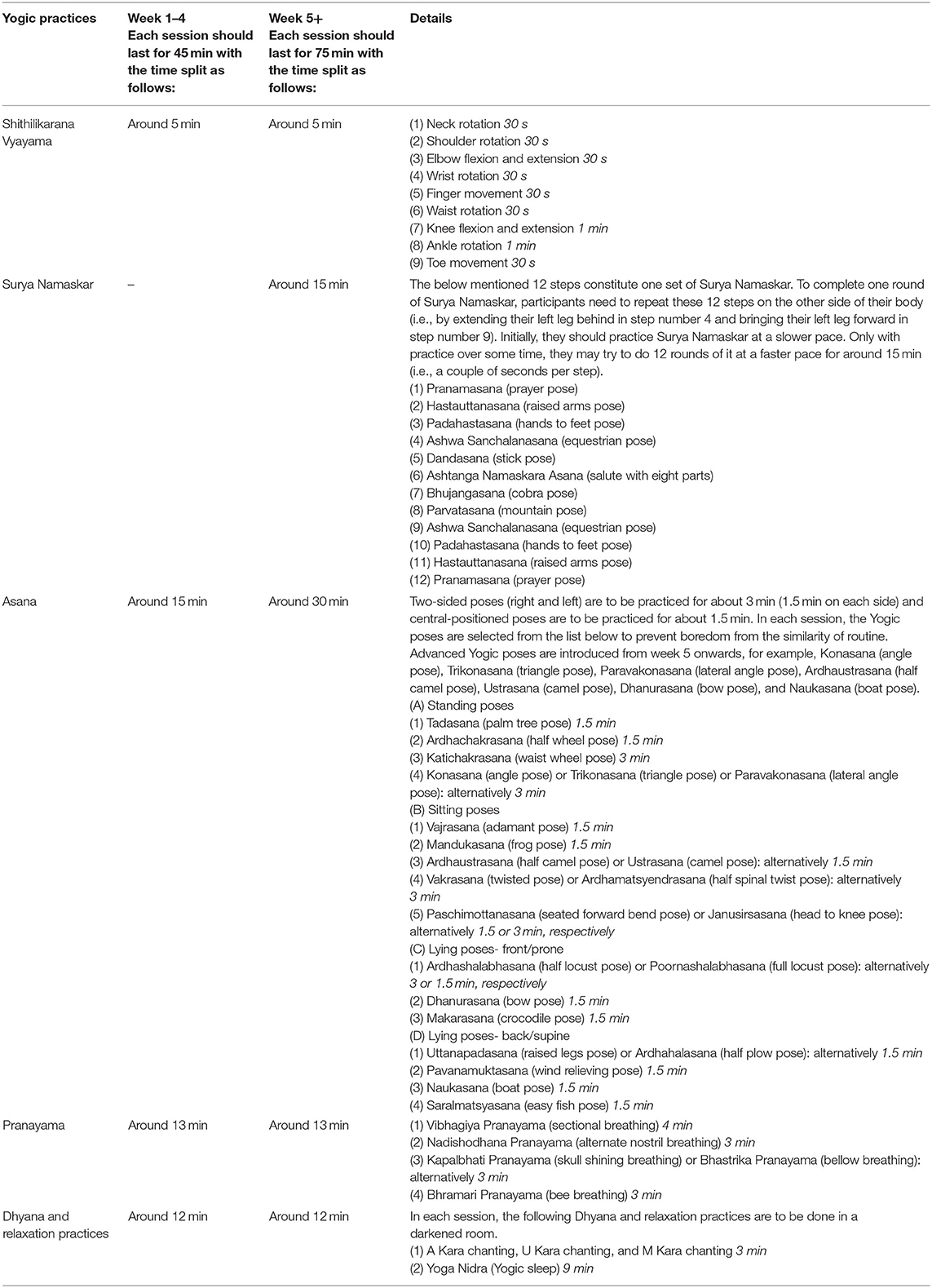

(2) Table 2 reports the validation of the identified Yogic practices. Out of the 58 identified Yogic practices, 31 were included in the intervention, namely, Shithilikarana Vyayama (loosening exercises), Surya Namaskar, 22 Asana (six standing poses, seven sitting poses, four lying poses-front/prone, and five lying poses-back/supine), five Pranayama, and two Dhyana and relaxation practices. There was one exception—Ardhaustrasana, a simplified form of Ustrasana (a sitting pose included in the intervention), was additionally included in the intervention as recommended by the Yoga experts during the validation work.

(3–5) The intervention is for adults (18–74 years) who are at high-risk of T2DM and are currently safe to do physical activity, determined by the Physical Activity Readiness Questionnaire (PAR-Q)/clinician. The intervention is not suitable for pregnant women; people with chest pain, a heart condition, or any serious or uncontrolled medical condition; or people who have recently undergone surgery. People with high blood pressure are required to check first with their clinician that their blood pressure is well-controlled before taking part in the intervention.

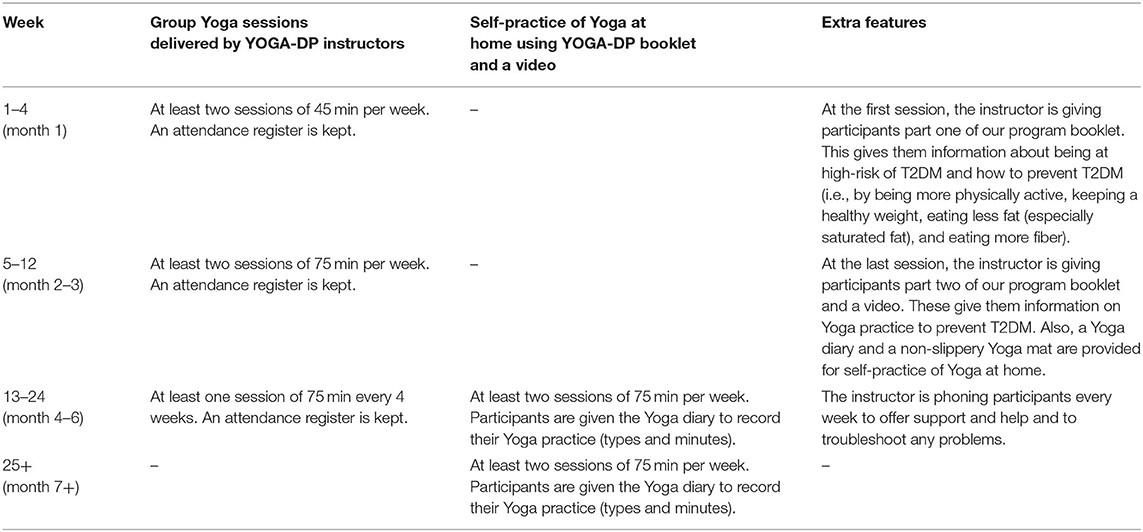

Tables 3, 4 report the structure of YOGA-DP and structure and content of the Yoga sessions, respectively. The intervention is a structured lifestyle education and exercise program, provided over a period of 24 weeks. The exercise part is based on Yoga and includes 32 Yogic practices, namely, Shithilikarana Vyayama, Surya Namaskar, 23 Asana (six standing poses, eight sitting poses, four lying poses-front/prone, and five lying poses-back/supine), five Pranayama, and two Dhyana and relaxation practices. Once participants complete the intervention, they are strongly encouraged to maintain a healthy lifestyle in the long-term, using the intervention booklet and video. It should be noted that, initially, we planned 52 supervised center-based group sessions (75 min/session X two sessions/week X 26 weeks). However, the intervention structure was modified after the consultation work to enhance intervention uptake and adherence i.e., based on the recommendations of experts in step number four. In the first instance, 75 min/session might appear a huge amount of time for the participants to commit to, and thus, we designed 45 min session in weeks 1–4 to avoid any physical or mental exhaustion and to gradually build their fitness. Second, to avoid the excessive burden of attending center-based sessions, weeks 13–24 comprise of one center-based session every 4 weeks and self-practice at home (using the intervention booklet and video) is recommended from week 13 onwards. Initial supervised center-based sessions are deemed to be appropriate for wider use in India due to the low levels of literacy. Similarly, initial group sessions are deemed to be appropriate for benefits from shared experiences and peer support. To improve intervention uptake and adherence, the group Yoga sessions are run locally (e.g., at Yoga centers and community centers) and at different time points of the day (with evening and weekend sessions), and participants can join as per their convenience. Some of their local travel costs for attending these sessions are reimbursed. A family member or someone close to the participant is invited to join them in these sessions. The intervention is delivered by YOGA-DP instructors—qualified and experienced Yoga teachers with formal training provided on the program, and they can speak the local languages. Female instructors are available for female participants.

Discussion

We report the systematic development of a novel Yoga program for T2DM prevention (YOGA-DP) among high-risk people in India. The duration of our intervention (24 weeks) is longer than many other Yoga interventions (43, 45–50, 52). Even after formally completing the intervention, participants are strongly encouraged to maintain a healthy lifestyle in the long-term, using the intervention booklet and video. The long-term maintenance of a healthy lifestyle is required, not just for preventing T2DM but also for overall health (3). However, lifestyle interventions' poor uptake and adherence (especially over the long-term) are well-recognized and can negatively affect the effectiveness of these interventions (53). This is the reason we incorporated multiple strategies to enhance uptake and adherence to our intervention. Some of these have already been used in previous successful studies (44–46, 49, 51, 52) and some came up during the intervention development process (e.g., female YOGA-DP instructors for female participants). In fact, as mentioned in the results section, the structure of our intervention evolved during the development process to enhance its uptake and adherence. Similar to many other Yoga interventions, our intervention includes Shithilikarana Vyayama, Asana (standing, sitting, and lying poses), Pranayama, and Dhyana and relaxation practices (43, 44, 52). Surya Namaskar is something additional in our intervention which is not always found in Yoga interventions. It can help in the prevention of T2DM, as it is considered a moderate-intensity activity and burns about 3.8–6.7 kcal/min (16, 17). Second, based on the suggestion of Yoga experts, AUM chanting (under Dhyana and relaxation practices) was not retained on religious grounds. Thus, the acceptance of the intervention could be high among people irrespective of their religious beliefs.

Yoga is a complex intervention, and the MRC guidance on developing and evaluating complex interventions provided the overall framework to develop the intervention (9). In fact, intervention development is the first step, and there are other steps as well, such as feasibility/piloting, evaluation, and implementation. There are questions throughout this guidance which helped us to design the study and to follow a systematic iterative process. It is not a “one size fits all” guidance but a generic one, and thus, not all the questions were relevant in our context. A major challenge was to systematically integrate traditional and western medical systems for T2DM prevention. Any traditional advice which is based on anecdotal (or contradictory) evidence was not included in the intervention. A similar systematic approach could be used to develop other local and cross-cultural health interventions.

The study has several strengths and weaknesses. This is one of the few studies to report the systematic development of a Yoga intervention. Another example is a Yoga-based cardiac rehabilitation (Yoga-CaRe) program which has been developed for secondary prevention of myocardial infarction in India (54). The interventions, study participants, and outcomes are different in the two studies. We followed a systematic process and reviewed the scientific literature as part of the process. In other words, we summarized the heterogeneous contents of successful and relevant Yoga interventions. The process also helped us to reach consensus on this complex intervention. A range of stakeholders (including healthcare, medical, and Yoga experts and practitioners and the public) were involved to explore issues like safety and acceptability of the intervention. The systematic review included only those studies that showed evidence of effectiveness in one of the prespecified outcomes. It should be noted that this was not a typical effectiveness systematic review, and the ultimate aim was to develop an intervention based on previous successful interventions. We also excluded studies if they did not report the Sanskrit name of the Yogic practice. Without the Sanskrit name, the English translation could mean more than one Yogic practice (and sometimes even modified or patented Yoga), and it is difficult to replicate such interventions for multiple reasons. There is a chance of missing a relevant Yogic practice. However, Yoga experts were involved in the next step, and they confirmed the inclusion of all the essential Yogic practices. Second, the Jadad score was calculated as part of the methodological quality assessment of the included RCTs. Apart from its many advantages, as mentioned before, it has disadvantages as well. For example, it is over-simplistic and does not take into account many essential methodological issues, such as the concealment of treatment allocation (55). Therefore, in addition to the Jadad score calculation, we assessed the allocation concealment. Third, due to the accessibility issues in India, we had to compress the video, which affected its quality. However, we have archived the original high-quality video for future use.

A multi-center feasibility RCT is currently in progress in India to determine the feasibility of undertaking the main RCT (56). If the feasibility is acceptable, we will design and conduct the main RCT. If the intervention is found to be effective, it will be a low-cost, acceptable, and local solution for preventing T2DM among high-risk people in India and for improving their overall health. It will also prevent the future clinical, personal, and economic burden of T2DM on patients, their families, the health system, and the economy. The advantages of preventing T2DM may extend to the prevention of T2DM related complications. More evidence-based choices will be available to people for preventing T2DM. The intervention will simultaneously empower people to manage their health. Given that T2DM and its related costs are global concerns and Yoga is popular or is becoming popular globally, there will be worldwide interest in this low-cost Yoga-based T2DM prevention program, particularly in other South Asian countries and in countries with South Asian ethnic minorities (57, 58). The intervention could be adapted, evaluated, and implemented to prevent T2DM in other settings or populations.

In conclusion, we systematically developed a novel Yoga program for T2DM prevention (YOGA-DP) among high-risk people in India. A multi-center feasibility RCT is in progress in India.

Data Availability Statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

Ethics Statement

The study was approved by four research ethics committees, namely, Faculty of Medicine and Health Sciences, University of Nottingham (UK); Centre for Chronic Disease Control (CCDC, India); Swami Vivekananda Yoga Anusandhana Samsthana (S-VYASA, India); and Bapu Nature Cure Hospital and Yogashram (BNCHY, India). The patients/participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study.

Author Contributions

KC conceptualized, designed, and conducted the study with the help of other authors, wrote the first draft of the manuscript, and other authors contributed significantly to the revision of the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

This study was funded by the UK's DFID/MRC/NIHR/Wellcome Trust Joint Global Health Trials (MR/R018278/1). The funding agencies had no role in developing the intervention or writing the manuscript.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

We thank all the people who have contributed to the development of YOGA-DP, Leicester Diabetes Centre, and Diabetes UK.

Supplementary Material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fpubh.2020.548674/full#supplementary-material

References

2. Anjana RM, Pradeepa R, Deepa M, Datta M, Sudha V, Unnikrishnan R, et al. Prevalence of diabetes and prediabetes in urban and rural India: Phase I results of the ICMR-INDIAB study. Diabetologia. (2011) 54:3022–7. doi: 10.1007/s00125-011-2291-5

3. National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE). Preventing Type 2 Diabetes: Risk Identification and Interventions for Individuals at High Risk. Manchester: NICE (2012).

4. Anjana RM, Pradeepa R, Das AK, Deepa M, Bhansali A, Joshi SR, et al. Physical activity and inactivity patterns in India: Results from the ICMR-INDIAB study (Phase-1) [ICMR-INDIAB-5]. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act. (2014) 11:26. doi: 10.1186/1479-5868-11-26

5. Gulati S, Misra A, Sharma M. Dietary fats and oils in India. Curr Diabetes Rev. (2017) 13:438–43. doi: 10.2174/1573399812666160811165712

6. Minocha S, Thomas T, Kurpad AV. Are ‘fruits and vegetables' intake really what they seem in India? Eur J Clin Nutr. (2018) 72:603–8. doi: 10.1038/s41430-018-0094-1

7. Gong QH, Kang JF, Ying YY, Li H, Zhang XH, Wu YH, et al. Lifestyle interventions for adults with impaired glucose tolerance: A systematic review and meta-analysis of the effects on glycemic control. Intern Med. (2015) 54:303–10. doi: 10.2169/internalmedicine.54.2745

8. World Health Organization (WHO). Global Strategy on Diet, Physical Activity and Health. Geneva: WHO (2015).

9. Medical Research Council (MRC). Developing and Evaluating Complex Interventions. London: MRC (2008).

10. Samal J. Situational analysis and future directions of AYUSH: An assessment through 5-year plans of India. J Intercult Ethnopharmacol. (2015) 4:348–54. doi: 10.5455/jice.20151101093011

11. Feuerstein G. The Deeper Dimensions of Yoga: Theory and Practice. Boston, MA: Shambhala Publications (2003).

12. National Health Service (NHS). A Guide to Yoga: Exercise. NHS (2018). Available online at: https://www.nhs.uk/live-well/exercise/guide-to-yoga/ (accessed September 2, 2019).

13. Anderson JG, Taylor AG. The metabolic syndrome and mind-body therapies: A systematic review. J Nutr Metab. (2011) 2011:276419. doi: 10.1155/2011/276419

14. Anjana RM, Ranjani H, Unnikrishnan R, Weber MB, Mohan V, Venkat Narayan KM. Exercise patterns and behaviour in Asian Indians: Data from the baseline survey of the diabetes community lifestyle improvement program. Diabetes Res Clin Pract. (2015) 107:77–84. doi: 10.1016/j.diabres.2014.09.053

15. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) and American College of Sports Medicine (ACSM). General Physical Activities Defined by Level of Intensity. Atlanta, GA: CDC (2015).

16. Sinha B, Ray US, Pathak A, Selvamurthy W. Energy cost and cardiorespiratory changes during the practice of Surya Namaskar. Indian J Physiol Pharmacol. (2004) 48:184–90.

17. Mody BS. Acute effects of Surya Namaskar on the cardiovascular and metabolic system. J Bodyw Mov Ther. (2011) 15:343–7. doi: 10.1016/j.jbmt.2010.05.001

18. Cramer H, Innes KE, Michalsen A, Vempati R, Langhorst J, Dobos GJ. Yoga for adults with type 2 diabetes mellitus (protocol). Cochrane Database Syst Rev. (2015) 4:CD011658. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD011658

19. Cramer H, Lauche R, Haller H, Steckhan N, Michalsen A, Dobos G. Effects of Yoga on cardiovascular disease risk factors: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Int J Cardiol. (2014) 173:170–83. doi: 10.1016/j.ijcard.2014.02.017

20. Cramer H, Langhorst J, Dobos G, Lauche R. Yoga for metabolic syndrome: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur J Prev Cardiol. (2016) 23:1982–93. doi: 10.1177/2047487316665729

21. Kumar V, Jagannathan A, Philip M, Thulasi A, Angadi P, Raghuram N. Role of Yoga for patients with type II diabetes mellitus: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Complement Ther Med. (2016) 25:104–12. doi: 10.1016/j.ctim.2016.02.001

22. Cui J, Yan JH, Yan LM, Pan L, Le JJ, Guo YZ. Effects of Yoga in adults with type 2 diabetes mellitus: A meta-analysis. J Diabetes Investig. (2017) 8:201–9. doi: 10.1111/jdi.12548

23. Sherman KJ. Guidelines for developing Yoga interventions for randomised trials. Evid Based Complement Alternat Med. (2012) 2012:143271. doi: 10.1155/2012/143271

24. Hoffmann TC, Glasziou PP, Boutron I, Milne R, Perera R, Moher D, et al. Better reporting of interventions: Template for intervention description and replication (TIDieR) checklist and guide. BMJ. (2014) 348:g1687. doi: 10.1136/bmj.g1687

25. Chattopadhyay K. Yogic Practices for Improving Blood Glucose Levels among Adults at High-Risk of or with Type 2 Diabetes: A Systematic Review. PROSPERO (2018). Available online at: https://www.crd.york.ac.uk/prospero/display_record.php?ID=CRD42018097216 (accessed September 29, 2020).

26. Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG, PRISMA Group. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: The PRISMA statement. BMJ. (2009) 339:b2535. doi: 10.1136/bmj.b2535

28. Jadad AR, Moore RA, Carroll D, Jenkinson C, Reynolds DJ, Gavaghan DJ, et al. Assessing the quality of reports of randomized clinical trials: Is blinding necessary? Control Clin Trials. (1996) 17:1–12. doi: 10.1016/0197-2456(95)00134-4

29. Olivo SA, Macedo LG, Gadotti IC, Fuentes J, Stanton T, Magee DJ. Scales to assess the quality of randomized controlled trials: A systematic review. Phys Ther. (2008) 88:156–75. doi: 10.2522/ptj.20070147

30. Lawshe CH. A quantitative approach to content validity. Pers Psychol. (1975) 28:563–75. doi: 10.1111/j.1744-6570.1975.tb01393.x

31. Patil NJ, Nagarathna R, Tekur P, Patil DN, Nagendra HR, Subramanya P. Designing, validation, and feasibility of integrated Yoga therapy module for chronic low back pain. Int J Yoga. (2015) 8:103–8. doi: 10.4103/0973-6131.158470

32. Leicester Diabetes Centre. Are You at Risk of Type-2 Diabetes? Information Booklet. Leicester: Leicester Diabetes Centre (2015).

33. Diabetes UK. Preventing Type 2 Diabetes. London: Diabetes UK (2018). Available online at: https://www.diabetes.org.uk/preventing-type-2-diabetes (accessed June 4, 2018).

34. Aljasir B, Bryson M, Al-Shehri B. Yoga practice for the management of type II diabetes mellitus in adults: A systematic review. Evid Based Complement Alternat Med. (2010) 7:399–408. doi: 10.1093/ecam/nen027

35. Bhurji N, Javer J, Gasevic D, Khan NA. Improving management of type 2 diabetes in South Asian patients: A systematic review of intervention studies. BMJ Open. (2016) 6:e008986. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2015-008986

36. Chu P, Gotink RA, Yeh GY, Goldie SJ, Hunink MG. The effectiveness of Yoga in modifying risk factors for cardiovascular disease and metabolic syndrome: A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Eur J Prev Cardiol. (2016) 23:291–307. doi: 10.1177/2047487314562741

37. Innes KE, Selfe TK. Yoga for adults with type 2 diabetes: A systematic review of controlled trials. J Diabetes Res. (2016) 2016:6979370. doi: 10.1155/2016/6979370

38. Pai LW, Li TC, Hwu YJ, Chang SC, Chen LL, Chang PY. The effectiveness of regular leisure-time physical activities on long-term glycemic control in people with type 2 diabetes: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Diabetes Res Clin Pract. (2016) 113:77–85. doi: 10.1016/j.diabres.2016.01.011

39. Vizcaino M, Stover E. The effect of Yoga practice on glycemic control and other health parameters in type 2 diabetes mellitus patients: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Complement Ther Med. (2016) 28:57–66. doi: 10.1016/j.ctim.2016.06.007

40. Eun CS, Dol KS. Effects of Yogic exercise on glycemic control and lipid profiles in type 2 diabetes: A meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Indian J Tradit Knowl. (2017) 16:S109–16.

41. Thind H, Lantini R, Balletto BL, Donahue ML, Salmoirago-Blotcher E, Bock BC, et al. The effects of Yoga among adults with type 2 diabetes: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Prev Med. (2017) 105:116–26. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2017.08.017

42. Jayawardena R, Ranasinghe P, Chathuranga T, Atapattu PM, Misra A. The benefits of Yoga practice compared to physical exercise in the management of type 2 diabetes mellitus: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Diabetes Metab Syndr. (2018) 12:795–805. doi: 10.1016/j.dsx.2018.04.008

43. Agrawal RP, Aradhana R, Hussain S, Beniwal R, Sabir M, Kochar DK, et al. Influence of Yogic treatment on quality of life outcomes, glycemic control and risk factors in diabetes mellitus. Int J Diab Dev Countries. (2003) 23:130–4.

44. Nagarathna R, Usharani MR, Rao AR, Chaku R, Kulkarni R, Nagendra HR. Efficacy of Yoga based life style modification program on medication score and lipid profile in type 2 diabetes: A randomized control study. Int J Diabetes Dev Ctries. (2012) 32:122–30. doi: 10.1007/s13410-012-0078-y

45. Vaishali K, Kumar V, Adhikari P, Unnikrishnan B. Effects of Yoga-based program on glycosylated hemoglobin level and serum lipid profile in community dwelling elderly subjects with chronic type 2 diabetes mellitus: A randomized controlled trial. Indian J Ancient Med Yoga. (2011) 4:69–76.

46. Vaishali K, Kumar V, Adhikari P, Unnikrishnan B. Effects of Yoga-based program on glycosylated hemoglobin level serum lipid profile in community dwelling elderly subjects with chronic type 2 diabetes mellitus: A randomized controlled trial. Phys Occupat Ther Geriatr. (2012) 30:22–30. doi: 10.3109/02703181.2012.656835

48. Kumar MU, Kalidasan R. Effect of selected Yoga asanas on blood sugar lipid profile and blood pressure parameters among type 2 diabetes mellitus patients. Acad Sports Scholar. (2014) 3:1–7.

49. Kumpatla S, Michael C, Viswanathan V. Effect of Yogasanas on glycaemic, haemodynamic and lipid profile in newly diagnosed subjects with type 2 diabetes. Int J Diabetes Dev Ctries. (2015) 35:S181–8. doi: 10.1007/s13410-014-0255-2

50. Sharma A, Sharma M, Sharma R, Meena PD, Gupta M, Meena M. Effect of Yoga on blood glucose and glycosylated haemoglobin level in diabetes mellitus type-2 patients. Int J Med Sci Educ. (2015) 2:1–9.

51. Singh VP, Khandelwal B, Sherpa NT. Effect of Yoga and music therapy with standard diabetes care in type II diabetes mellitus: A randomized control study. Int J Adv Res. (2015) 3:386–99.

52. Keerthi GS, Pal P, Pal GK, Sahoo JP, Sridhar MG, Balachander J. Effect of 12 weeks of Yoga therapy on quality of life and Indian diabetes risk score in normotensive Indian young adult prediabetics and diabetics: Randomized control trial. J Clin Diagn Res. (2017) 11:CC10–4. doi: 10.7860/JCDR/2017/29307.10633

53. Middleton KR, Anton SD, Perri MG. Long-term adherence to health behavior change. Am J Lifestyle Med. (2013) 7:395–404. doi: 10.1177/1559827613488867

54. Chattopadhyay K, Chandrasekaran AM, Praveen PA, Manchanda SC, Madan K, Ajay VS, et al. Development of a Yoga-based cardiac rehabilitation (Yoga-CaRe) programme for secondary prevention of myocardial infarction. Evid Based Complement Alternat Med. (2019) 2019:7470184. doi: 10.1155/2019/7470184

55. Hempel S, Suttorp MJ, Miles JNV, Wang Z, Maglione M, Morton S, et al. Empirical Evidence of Associations Between Trial Quality and Effect Size. Rockville, MD: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (2011).

56. Chattopadhyay K, Mishra P, Singh K, Tess Harris T, Hamer M, Greenfield SM, et al. Yoga programme for type-2 diabetes prevention (YOGA-DP) among high risk people in India: A multicentre feasibility randomised controlled trial protocol. BMJ Open. (2020) 10:e036277. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2019-036277

57. Birdee GS, Legedza AT, Saper RB, Bertisch SM, Eisenberg DM, Phillips RS. Characteristics of Yoga users: Results of a national survey. J Gen Intern Med. (2008) 23:1653–8. doi: 10.1007/s11606-008-0735-5

Keywords: Yoga, prevention, prediabetes, lifestyle, physical activity, diet

Citation: Chattopadhyay K, Mishra P, Manjunath NK, Harris T, Hamer M, Greenfield SM, Wang H, Singh K, Lewis SA, Tandon N, Kinra S and Prabhakaran D (2020) Development of a Yoga Program for Type-2 Diabetes Prevention (YOGA-DP) Among High-Risk People in India. Front. Public Health 8:548674. doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2020.548674

Received: 03 April 2020; Accepted: 02 October 2020;

Published: 17 November 2020.

Edited by:

Lambert Felix, The University of Manchester, United KingdomReviewed by:

Raj Maturi, Indiana University Bloomington, United StatesAnju Devianee Keetharuth, The University of Sheffield, United Kingdom

Copyright © 2020 Chattopadhyay, Mishra, Manjunath, Harris, Hamer, Greenfield, Wang, Singh, Lewis, Tandon, Kinra and Prabhakaran. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Kaushik Chattopadhyay, a2F1c2hpay5jaGF0dG9wYWRoeWF5QG5vdHRpbmdoYW0uYWMudWs=

Kaushik Chattopadhyay1,2*

Kaushik Chattopadhyay1,2* Tess Harris

Tess Harris Sheila Margaret Greenfield

Sheila Margaret Greenfield Haiquan Wang

Haiquan Wang Kavita Singh

Kavita Singh Sanjay Kinra

Sanjay Kinra