Abstract

Background:

The agony and economic strain of cancer and HIV/AIDS therapies severely impact patients' psychological wellbeing. Meanwhile, sexual minorities experience discrimination and mental illness. LGBT individuals with cancer and HIV/AIDS play two roles. It is important to understand and examine this groups mental wellbeing.

Objective:

The purpose of this study is to synthesize current studies on the impact of HIV/AIDS and cancer on LGBT patients' psychological wellbeing.

Methods:

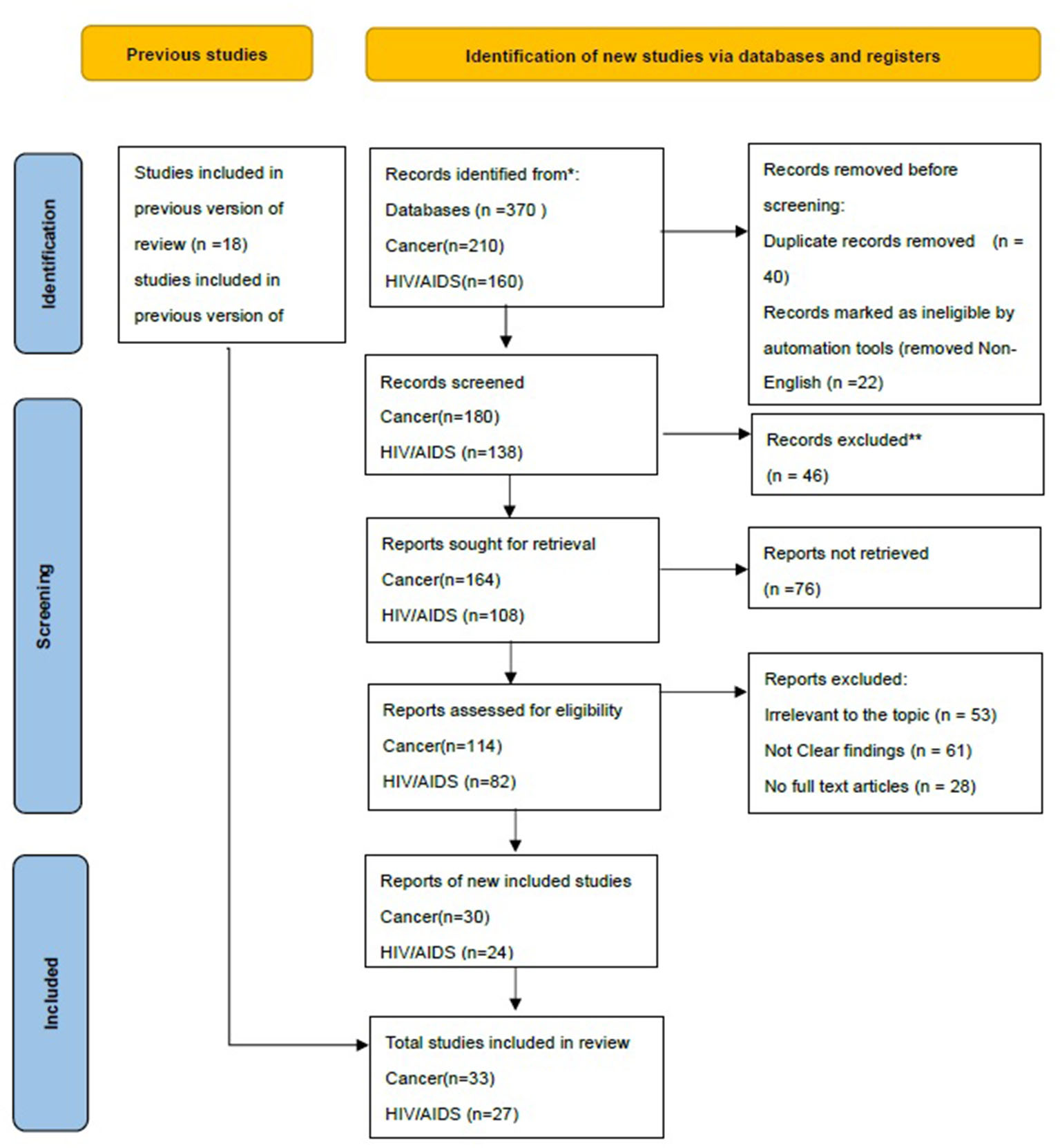

This research uses a systematic literature review at first and later stage a meta-analysis was run on the same review. In this study, data from Google academic and Web of Science has been used to filter literature. PRISMA 2020 Flow Diagram seeks research on LGBT cancer and HIV/AIDS patients. The above sites yielded 370 related papers, some of which were removed due to age or inaccuracy. Finally, meta-analyses was done on 27 HIV/AIDS and 33 cancer patients's analyse.

Results:

The research included 9,898 LGBT cancer sufferers with AIDS and 14,465 cancer sufferers with HIV/AIDS. Using meta-analysis, we discovered the gap in psychological wellbeing scores between HIV/AIDS LGBT and non-LGBT groups ranged from −10.86 to 15.63. The overall score disparity between the HIV/AIDS LGBT and non-LGBT groups was 1.270 (95% CI = 0.990–1.560, Z = 86.58, P < 0.1). The disparity in psychological wellbeing scores between cancer LGBT group and general group varies from −8.77 to 20.94 in the 34 papers examined in this study. Overall, the psychological wellbeing score disparity between the cancer LGBT subset and the general group was 12.48 (95% CI was 10.05–14.92, Test Z-value was 268.40, P-value was <0.1).

Conclusion:

Inflammation and fibrosis in HIV/AIDS and cancer sufferers adversely affect their psychological wellbeing.

Introduction

Non-Hodgkin lymphoma, Kaposi's sarcoma, and cervical cancer, which are known as AIDS-defining cancers (ADCs), occur more frequently in HIV/AIDS patients than in HIV-negative individuals (1, 2). In other words, the HIV/AIDS conditions contribute to the development of these cancers in HIV-positive individuals. Aside from this, there is evidence that HIV/AIDS patients are at a higher risk for developing certain non-AIDS-defining cancers (NADCs), despite the fact that there is no known direct pathological relationship between HIV/AIDS and these cancers, unlike the relationship between HIV/AIDS and ADCs (1).

In addition to being one of these NADCs, prostate cancer is the second leading cause of cancer death among men in the United States. While the effects of prostate cancer detection and treatment on the mental health of sexual minorities, such as males who are sexually attracted to males or transgender females, remain unknown, there is a growing body of evidence that suggests that these treatments may be beneficial (3, 4). The infrequency with which information on patients' sexual orientation is collected makes it difficult to conduct research on this population. In fact, several epidemiological studies involving prostate cancer patients from sexual minorities have demonstrated varying rates of prostate cancer screening, diagnosis, and treatment (5).

According to a number of qualitative studies, sexual minority communities have substantial cancer health inequalities (6, 7). As a consequence of differences in sexual behavior, social support networks, and links to the health sector, sexual minorities' experiences with prostate cancer are distinct and need individualized medical attention (8, 9). Notably, sexual minorities among prostate cancer patients were found to have more severe health-related quality of life consequences than heterosexual male patients: having weaker support networks, experiencing greater mental disturbance due to sexual problems such as undefined fields after therapies, being excluded from the health sector, and expressing greater dissatisfaction with therapies (10).

Additionally, few oncology professionals have received training on how to best serve the needs of Sexual and Gender Minority (SGM) patients, and few cancer centers have implemented policies or regular procedures to gather sexual orientation and gender identity information in the electronic medical record, utilize gender-neutral language on forms, provide SGM-specific support services, and/or mandate SGM cultural humility training for all personnel (11). Until doctors receive adequate training on the clinical and behavioral requirements of SGM patients, patients will continue to be responsible for teaching their physicians how to care for them, leading to inadequate treatment and perhaps reinforcing the stigmatizing actions of clinicians (12, 13).

Consequently, the effects of HIV/AIDS and cancer on the mental health of HIV/AIDS-related cancer patients are deserving of study. Although there has historically been a paucity of literature on sexual minorities among cancer patients, there has been a substantial increase in research on the topic in recent years, solidifying its position as an important area of inquiry. This study aims to synthesize current research on the impact of HIV/AIDS and cancer on the psychological wellbeing of LGBT patients.

Literature review

Sexual minorities

When it comes to defining sexual minorities, because they are a notion brought and transferred from outside, the academic field largely agrees with the United Nations Development Programme's 2016 survey report on the survival of sexual minorities in refer to those belonging to minorities in terms of sexual orientation, gender identity and gender expression (14). Sexual orientation refers to individuals of a particular gender who are the subject of emotional inclination and sex drive. For instance, if the target of emotional inclination and sex drive is homosexual, it is referred to as homosexual; if the target is both gay and heterosexual, it is referred to as bisexual (15–17).

Gender identity refers to an individual's emotional proclivity and psychological identification with a certain gender. Transgender individuals, for instance, identify as females when their biological gender at birth is male, despite the fact that their biological gender was female, or as males when their biological gender was female, thus constituting a minority in terms of gender identity (18, 19). Gender expression is the process of expressing one's gender through clothing, grooming, and conduct. For instance, males who dress up as females or females who dress up as males are considered minority groups in terms of gender expression and are referred to as transvestites (20). Nevertheless, the academic world turns a blind eye to these communities (21, 22). Sexual minorities, as defined above, primarily comprise homosexuals, bisexuals, transgenders, and intersexual. As a result, some academics think that sexual minorities are sexual orientation minorities in comparison to heterosexual people, including lesbians, gay men, bisexuals, and transgender people (LGBT) (23). Its flaw is that its restricted reach excludes various sexual minorities and does not promote the rights and welfare of diverse groups based on sexual orientation, gender identity, and gender expression as civilization develops (24–26).

Impacts on psychological wellbeing among cancer patients

Individuals will experience significant pain in their body, mind, and interpersonal connection following cancer diagnosis and therapy, leading to a variety of mental conditions (27, 28). Such biological and cognitive shifts have a detrimental effect on the psychological wellbeing and prognosis of breast cancer sufferers, perpetuating the cycle. Numerous empirical researches conducted domestically and overseas demonstrates that good psychological tools benefit the psychological wellbeing of Anzheng sufferers (29, 30). Deimling et al. (31) and Sardella et al. (32) discovered that the degree of psychological optimism in elderly cancer patients may predict disease progression. According to Sitanggang et al. (33), cancer sufferers with a high level of expectation to be more pleased and acknowledged in their marriage (partnership). Putri and Makiyah (34) discovered that cancer sufferers with a poor ego are more receptive to more invasive treatment approaches.

Simultaneously, the greater the level of self-esteem, the more satisfied patients are with their therapy (35). Self-esteem is a critical protective element for cancer sufferers' psychological wellbeing (36). Ristevska-Dimitrovska and Batic (37) discovered that sufferers with improved psychological wellbeing also improved their quality of life, while their functioning improved. While successfully relieved cancer-related symptoms, Ristevska-Dimitrovska and Batic (37) also noted that adaptability was a potential mechanism against depression and psychological illnesses (38). Carver stresses that early sufferers who have a high level of hopeful may not only have more realistic predictions about their state, but also have a more favorable impact on postoperative recovery (39, 40). Garner and de Visser (41) discovered that optimism not only has a significant impact on depression alleviation, but also has an additional impact through social connectedness. To summarize, there is a relationship between cancer and sufferers' psychological wellbeing. While the suffering associated with cancer therapy has a direct impact on patients' psychological wellbeing, the level of patients' psychological wellbeing also has a significant impact on the curative implication and therapy intensity of cancer (42–45).

Study on psychological wellbeing HIV/AIDS patients

Currently, there is no real treatment for HIV/AIDS (46). When infected, it will be with you for the rest of your life. It is incapable of eradicating severe infections, which is why AIDS is transmitting throughout the globe. HIV/AIDS cases are rising (47). According to UNAIDS data, 38 million individuals globally are HIV-positive. HIV infected 1 million 700,000 of the globe's newly infected individuals in 2019. Six hundred ninety thousand individuals died of AIDS-related diseases in 2019 (48). According to the existing state of knowledge, the majority of analyses presume that current HIV/AIDS patients suffer from serious mental issues marked by depression and anxiety (49–52). Social discrimination and isolation are significant contributors to psychological wellbeing issues among HIV-positive individuals (53–56).

Discrimination against HIV/AIDS-related groups is primarily motivated by two factors. To begin, a large percentage of AIDS patients are men who have sex with men, intravenous drug users, and commercial sex traders (57). These individuals are frequently not approved by the majority of the general public, and they are viewed as having moral flaws and character flaws. Two, the HIV/AIDS group is highly contagious and poses a threat to others. HIV/AIDS communities are frequently portrayed negatively in news coverage, and are frequently categorized as “dangerous” and “revenge society” (58, 59). With such a social paradigm, it is not only challenging to be completely compassionate and selfless, but also frequently confronts the conundrum of causing more difficulties for oneself by exposing identity (60). As a result of their shame and self-protection, many HIV-positive individuals are hesitant to disclose their infection to their neighbors or even family members (61). Additionally, they reject some individuals access to clinical, mental, and community services. Individuals with HIV have mental issues as a result of their dual physiological and psychological problems, and they may be dealing with mental anxiety, depression, or even the Dutch act (17), which happens regularly (62, 63).

Methods

This research used a systematic review and meta-analysis as its methodology. The primary techniques of study include literature review, questionnaires, and meta-analysis. Meta-analysis is a mathematical process that integrates the findings of many studies conducted in the same field under similar circumstances. The researcher mostly utilizes stata.16 as the statistical analysis program to generate the meta-analysis table and forest map, and the statistics are obtained from the internet and Google academic. The PRISMA 2020 Flow Diagram is employed to conduct a literature screening for publications involving older men who have sex with men with cancer. The authors gathered a total of 370 relevant papers through Google academic and websites, and eliminated several due to their younger age and imprecise statistical representation. Lastly, the meta-analysis comprised 27 papers on HIV/AIDS and 33 studies on cancer.

Search strategy

Numerous researches have been conducted on the psychological wellbeing of HIV/AIDS and Cancer sufferers, but few on the psychological wellbeing of HIV/AIDS and Cancer LGBT sufferers. This research performed a systematic review and meta-analysis of articles published between August 1, 2018 and August 1, 2021 in Google scholarly and Web of Science. Such personal records investigated homosexuality, cancer sufferers, geriatric populations, and psychotherapy treatments. The authors mostly utilizes PRISMA 2020 Flow Diagram (Registered Code: CRD42022314571) to conduct literature searches (Figure 1).

Figure 1

Study selection based on PRISMA 2020 flow diagram.

Study inclusion and exclusion criteria

To conduct research on the effect of cancer and HIV/AIDS on the mental wellbeing of the LGBT community, we must collect data on the psychological wellbeing of gays and cancer sufferers. We solely considered retrospective or prospective observational research and omitted other kinds of literature (like reviewing, editing, case study, consensus therapy, or recommendations). Additionally, research lacking the whole text was eliminated.

All databases were queried using the keywords, and the results were exported to the citation management system EndNote Reference, where the duplicates were removed. The second stage is to review the abstracts and titles of the remaining publications to determine which are relevant to the study at hand. Before evaluating the papers based on the qualifying criteria, three reviewers (ASWC, WLH, and JMCH) conducted a preliminary screening. After title screening, full-text research must meet inclusion and exclusion criteria. The qualifying conditions are shown in Table 1 below.

Table 1

| Inclusion | Exclusion | |

|---|---|---|

| Participants | • Studies that included adult or older male participants | • Studies that did not clearly state the classification of participants according to their gender |

| Study type and details | • Studies with transparent findings • Studies with full-text manuscripts • English published studies • Primary and observational studies | • Studies that lacked interpretable and clear findings • Studies without full-text manuscripts • Non-English published articles • Case reports, other systematic reviews, and meta-analyses |

| Outcome | • Studies evaluating HIV/AIDS and Cancer and impacts of Psychological Wellbeing among Sexual Minorities | • Studies evaluating other outcomes apart from Studies evaluating HIV/ AIDS and Cancer and impacts of Psychological Wellbeing among Sexual Minorities |

Inclusion and exclusion criteria.

Literature selection

Upon removing redundant publications from the bibliographic database's research outcomes, three independent researchers (ASWC, WLH, and JMCH) evaluated the remaining titles and abstracts for papers that may qualify for full-text evaluation. Additionally, the bibliography of publications included in this manner is carefully researched. Following an examination of the raw data and consultation with another researcher (ANOSI), any discrepancies were addressed through conversation.

Meta-analysis

Data collection and extraction

The same scholars finished and inspected data extraction. Gender, cancer, demographic factors (age, gender, sexuality, household income, and geographic area), clinical signs (primarily inflammation and fibrosis), and patient objective records (like psychological wellbeing) are all retrieved (64–67).

A meta-analysis of the psychological effects of HIV/AIDS LGBT patients

As per clinical capability at the time of writing, AIDS is an untreatable illness. In the present research, there are limited papers on the impact of inflammation and fibrosis on the psychological wellbeing of AIDS sufferers. Prisma 2020 was used to conduct a search of the literature, some of which had issues including a huge sample size or a lack of clarity in the reporting of findings. Ultimately, twenty-seven papers were chosen for meta-analysis. The following are the findings:

Table 2 summarizes a meta-analysis of the impact of inflammation and fibrosis on the psychological wellbeing of HIV/AIDS sufferers. The SMD column in the table indicates the meta-analysis's associated response value. A comparison experiment was used to perform the meta-analysis. The control group consisted of healthy individuals. The control group consisted of an HIV/AIDS LGBT patient who acted as an inhibitor of HIV/AIDS-related inflammation and fibrosis. Through looking at the average scores for the two factors on psychological wellbeing factors, we may determine if HIV/AIDS-related inflammation and fibrosis have a substantial impact on the psychological wellbeing of LGBT patients. The greater the value, the more dysfunctional the psychological state. SMD one denotes the disparity in scores between the two categories.

Table 2

| Author(s) (year) | SMD | [95% Conf. interval] | [95% Conf. interval] | % Weight | Study quality |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Tomar et al. (2021) (61) | 6.41 | 4.13 | 8.69 | 1.6 | Good |

| Philpot et al. (2021) (68) | −6.96 | −8.59 | −5.33 | 3.12 | Good |

| Liboro et al. (2021) (69) | 10.48 | 8.94 | 12.02 | 3.52 | Good |

| Gonzales et al. (2017) (70) | 18.90 | 17.23 | 20.56 | 2.99 | Good |

| Freese et al. (2017) (71) | 9.94 | 8.68 | 11.21 | 5.22 | Good |

| Batchelder et al. (2017) (72) | 7.24 | 5.47 | 9.01 | 2.66 | Moderate |

| Wilson et al. (2016) (73) | 3.94 | 2.44 | 5.44 | 3.72 | Good |

| Rodriguez et al. (2016) (74) | 13.67 | 12.42 | 14.92 | 5.34 | Good |

| Liboro et al. (2016) (75) | 15.61 | 17.44 | 13.77 | 2.48 | Good |

| Dowshen et al. (2016) (76) | −2.17 | −3.75 | −0.59 | 3.34 | Good |

| Swartz et al. (2015) (77) | 2.81 | 1.83 | 3.79 | 8.7 | Moderate |

| Lewis et al. (2015) (78) | −3.08 | −4.38 | −1.79 | 4.95 | Moderate |

| Jadwin et al. (2015) (79) | 6.39 | 4.86 | 7.93 | 3.52 | Good |

| Garland et al. (2014) (80) | 2.21 | 0.84 | 3.59 | 4.41 | Good |

| DiNapoli et al. (2014) (81) | −10.86 | −12.30 | −9.42 | 4.01 | Good |

| Coulter et al. (2014) (82) | 1.10 | −1.55 | 1.55 | 3.46 | Good |

| Cahill et al. (2014) (83) | −6.42 | −8.09 | −4.76 | 3.01 | Good |

| Hergenrather et al. (2013) (84) | −3.94 | −5.42 | −2.46 | 3.78 | Good |

| Grey et al. (2013) (85) | −2.11 | −4.02 | −0.19 | 2.27 | Moderate |

| Brennan et al. (2013) (86) | −0.40 | −2.06 | 1.27 | 3 | Good |

| Wight et al. (2012) (87) | −6.88 | −8.59 | −5.18 | 2.86 | Good |

| Haile et al. (2011) (88) | 1.67 | 0.28 | 3.06 | 4.32 | Good |

| Pantalone et al. (2010) (89) | 6.28 | 4.53 | 8.04 | 2.7 | Good |

| Tritt (2010) et al. (90) | 3.82 | 2.26 | 5.38 | 3.43 | Good |

| McDowell et al. (2007) (91) | −5.22 | −6.51 | −3.94 | 5.03 | Good |

| Countenay et al. (2006) (92) | 1.69 | 0.01 | 3.37 | 2.95 | Good |

| Wilson et al. (2004) (93) | −5.92 | −7.43 | −4.40 | 3.63 | Good |

| Overall, IV | 1.270 | 0.990 | 1.560 | 100 |

Mental health meta-analysis of HIV/AIDS LGBT patients.

Test of overall effect = 0: z = 86.58, p < 0.0001.

The majority of the research reports a favorable score disparity. This demonstrates that AIDS-related inflammation and fibrosis will have a detrimental effect on the psychological wellbeing of LGBT AIDS sufferers. After analyzing 27 publications on the psychological wellbeing of the AIDS LGBT community, we discovered that the gap in psychological wellbeing scores between the HIV/ AIDS LGBT community and the general population ranges from −10.86 to 15.63. The overall findings indicated a 1.270 point gap in psychological wellbeing scores between the AIDS LGBT population and the general population (95% confidence interval 0.990–1.560, Z = 86.58 and P < 0.001).

Although the mental health measurement methods or scales used in these studies are different in different kinds of literature, as a meta-analysis, this study did not consider different intervention therapies. As can be seen from the above table, the final overall Z-value is 86.58 and the P < 0.1, which indicates that the average score of mental health in the control group is 1.270 points higher than that in the experimental group. That is, the inflammation and fibrosis of HIV/AIDS have a significant effect on the negative mental health of the LGBT group.

Table 3 summarizes the heterogeneity test findings from 27 research studies. Like the table indicates, the p-value is 0.04, which is smaller than 0.001, suggesting heterogeneity. The heterogeneity score is 99.0%, suggesting that available research has a high degree of heterogeneity. Lastly, we can observe that the associated Cochran's Q-value is 2,476.47 and the accompanying p < 0.1, indicating that inflammation and fibrosis in HIV/AIDS have a substantial detrimental effect on LGBT sufferers' psychological wellbeing.

Table 3

| Measure | Value | df | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cochran's Q | 2,476.47 | 26 | 0.0001 |

| H | 9.760 | 1.000 | |

| I2 (%) | 99.0% | 0.0% | 0.0% |

Heterogeneity analysis of related studies.

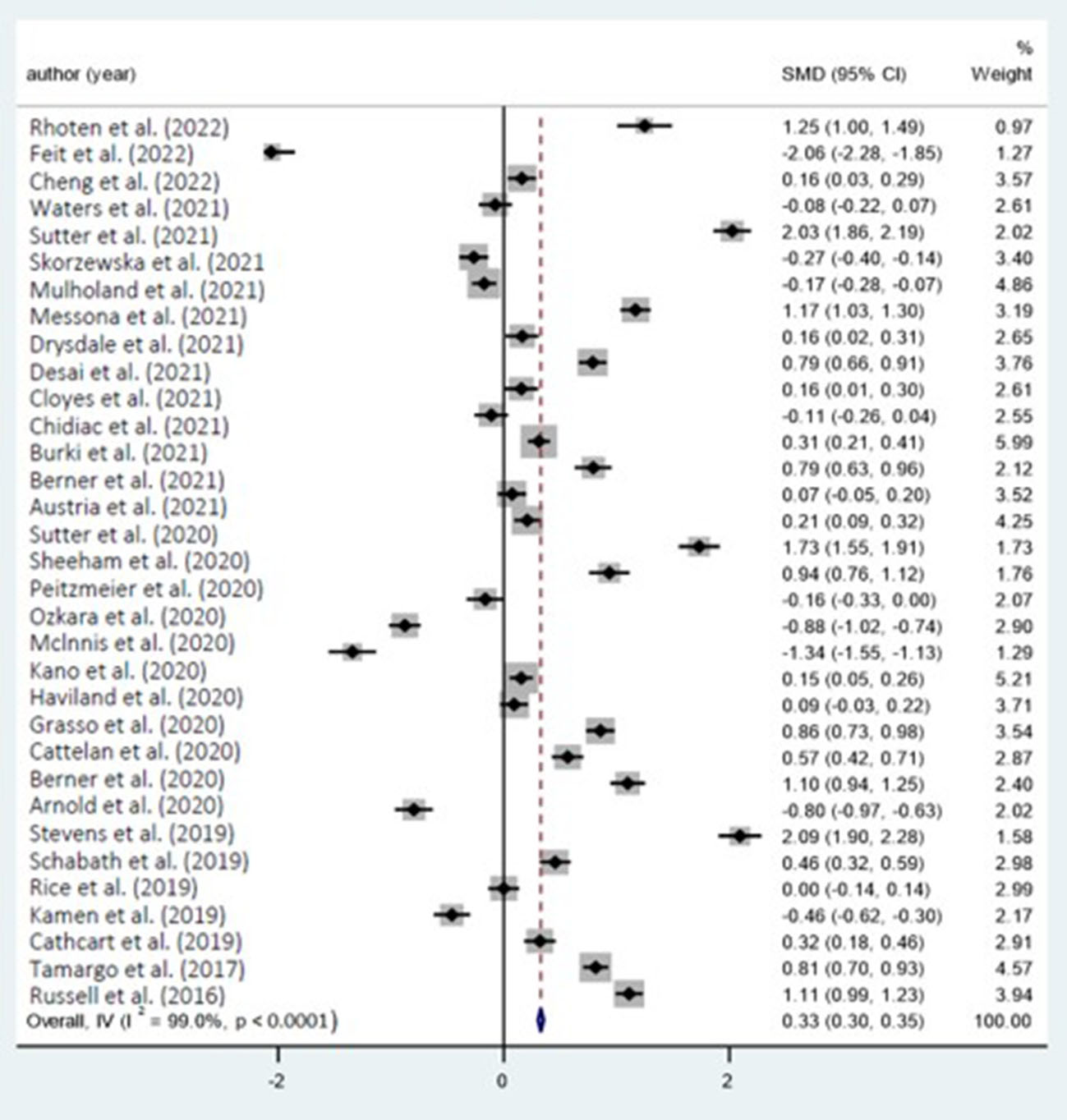

Cancer remains an untreatable illness in the present state of medical science. There is minimal research on the effect of inflammation and fibrosis on patients' mental wellbeing at the moment, which limits the volume of publications used for the meta-analysis. Prisma 2020 was used to conduct a search of the literature, and a few of those had issues including a huge sample size or a lack of clarity in the reporting of findings. Ultimately, 33 papers (Figure 2) were chosen for meta-analysis. The following are the findings:

Figure 2

Forest plot with included studies on the effect of HIV/AIDS and mental health.

Table 4 summarizes the findings of a meta-analysis on the potential effect of inflammation and fibrosis on the psychological wellbeing of LGBT sufferers. The SMD column in the table indicates the effect value that corresponds to the literature in the meta-analysis. All of the studies included in the meta-analysis are comparative studies where the control group is either ordinary or LGBT patients with cancer who have inflammation and fibrosis. Through looking at the mean scores on psychological wellbeing factors for the two groups, we can determine if cancer-related inflammation and fibrosis have a substantial effect on the psychological wellbeing of LGBT sufferers. The greater the value, the more dysfunctional the psychological state.

Table 4

| Author(s) (year) | SMD | [95% Conf. interval] | [95% Conf. interval] | % Weight | Study quality |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rhoten et al. (2022) (94) | 12.48 | 10.05 | 14.92 | 0.97 | Good |

| Feit et al. (2022) (95) | 20.63 | 18.5 | 22.76 | 1.27 | Good |

| Cheng et al. (2022) (96) | 1.60 | 0.33 | 2.87 | 3.57 | Good |

| Waters et al. (2021) (97) | −0.75 | −2.23 | 0.73 | 2.61 | Good |

| Sutter et al. (2021) (6) | 20.25 | 18.57 | 21.94 | 2.02 | Good |

| Skorzewska et al. (2021) (98) | −2.66 | −3.96 | −1.36 | 3.4 | Moderate |

| Mulholand et al. (2021) (99) | −1.74 | −2.83 | −0.66 | 4.86 | Good |

| Messona et al. (2021) (100) | 11.68 | 10.34 | 13.02 | 3.19 | Good |

| Drysdale et al. (2021) (101) | 1.63 | 0.16 | 3.10 | 2.65 | Good |

| Desai et al. (2021) (102) | 7.88 | 6.64 | 9.12 | 3.76 | Good |

| Cloyes et al. (2021) (103) | 1.56 | 0.08 | 3.05 | 2.61 | Moderate |

| Chidiac et al. (2021) (104) | −1.10 | −2.60 | 0.40 | 2.55 | Moderate |

| Burki et al. (2021) (105) | 3.11 | 2.13 | 4.09 | 5.99 | Good |

| Berner et al. (2021) (106) | 7.93 | 6.28 | 9.58 | 2.12 | Good |

| Austria et al. (2021) (107) | 0.73 | −0.55 | 2.01 | 3.52 | Good |

| Sutter et al. (2020) (108) | 2.08 | 0.92 | 3.24 | 4.25 | Good |

| Sheeham et al. (2020) (109) | 17.32 | 15.50 | 19.14 | 1.73 | Good |

| Peitzmeier et al. (2020) (110) | 9.36 | 7.55 | 11.16 | 1.76 | Good |

| Ozkara et al. (2020) (111) | −1.63 | −3.30 | 0.03 | 2.07 | Moderate |

| Mclnnis et al. (2020) (112) | −8.77 | −10.18 | −7.36 | 2.9 | Good |

| Kano et al. (2020) (113) | −13.42 | −15.53 | −11.30 | 1.29 | Good |

| Haviland et al. (2020) (114) | 1.54 | 0.49 | 2.59 | 5.21 | Good |

| Grasso et al. (2020) (115) | 0.91 | −0.33 | 2.16 | 3.71 | Good |

| Cattelan et al. (2020) (116) | 8.57 | 7.29 | 9.84 | 3.54 | Good |

| Berner et al. (2020) (117) | 5.66 | 4.25 | 7.07 | 2.87 | Good |

| Arnold et al. (2020) (118) | 10.98 | 9.43 | 12.53 | 2.4 | Good |

| Stevens et al. (2019) (119) | −7.97 | −9.66 | −6.29 | 2.02 | Good |

| Schabath et al. (2019) (120) | 20.94 | 19.03 | 22.84 | 1.58 | Moderate |

| Rice et al. (2019) (121) | 4.55 | 3.16 | 5.94 | 2.98 | Good |

| Kamen et al. (2019) (122) | 2.11 | −1.67 | 2.48 | 2.99 | Good |

| Cathcart et al. (2019) (123) | −4.59 | −6.22 | −2.97 | 2.17 | Moderate |

| Tamargo et al. (2017) (124) | 3.20 | 1.80 | 4.61 | 2.91 | Good |

| Russell et al. (2016) (125) | 8.14 | 7.02 | 9.26 | 4.57 | Good |

| overall | 12.48 | 10.05 | 14.92 | 100 |

Meta-analysis of mental health of cancer LGBT patients.

Test of overall effect = 0: z = 268.40, p < 0.0001.

SMD is the disparity in scores between the two categories, and the majority of research shows that cancer inflammation and fibrosis have a detrimental effect on the psychological wellbeing of LGBT cancer sufferers. According to the 33 research on the psychological wellbeing of cancer LGBT individuals examined in this study, the disparity in psychological wellbeing scores between cancer LGBT individuals and the general population varies between −8.77 and 20.94. The overall findings indicated that there was a 12.48 point gap in psychological wellbeing scores between the cancer LGBT subgroup and the general group (95% confidence interval was 10.05–14.92, egger Test Z-value = 268.40, p < 0.1).

While the techniques or ratings used to assess psychological wellbeing in such research vary throughout the publications, as a meta-analysis, this study excluded various intervention treatments. As shown in the preceding table, the ultimate overall effect Z-value = 268.40 and the p < 0.0001, suggesting that the mean psychological wellbeing score in the control group is 12.48 points higher compared to the experimental sample, and that is noteworthy. This demonstrates that cancer's inflammation and fibrosis have a substantial detrimental effect on the psychological wellbeing of the LGBT community.

The preceding Table 5 summarizes the heterogeneity test outcomes from 33 analyses. Like the table indicates, the p < 0.0001, which is < 0.001, suggesting heterogeneity. The heterogeneity score is 99.0%, suggesting that available research has a high degree of heterogeneity. Eventually, the associated Cochran's Q-value is 3,300.34 and the accompanying p < 0.1, suggesting that inflammation and fibrosis in cancer will have a substantial detrimental effect on sufferers' psychological wellbeing (Figure 3).

Table 5

| Measure | Value | df | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cochran's Q | 3,300.34 | 33 | 0.0001 |

| H | 10.001 | 1.000 | |

| I2 (%) | 99.0% | 0.0% | 0.0% |

Heterogeneity analysis of related studies.

Figure 3

Forest plot with included studies on the cancer and mental health.

Discussion

Cancer and HIV/AIDS are significant illnesses affecting contemporary population wellbeing (20, 126). More effective technical strategies for HIV/AIDS and cancer do not exist at present. Cancer is often treated with surgery, radiation, and chemotherapy (127). The majority of cancer therapies, particularly chemotherapy, are very painful for sufferers. Unpleasant sensations have a direct effect on the psychological wellbeing of cancer sufferers, lowering their standard of living even more (128). For HIV/AIDS sufferers, the many difficulties created by social groups' intrinsic prejudice and immunity will have a major detrimental effect on their psychological wellbeing. Current research has examined the detrimental impact of inflammation and fibrosis on the psychological wellbeing of cancer and HIV/AIDS sufferers (129). Additionally, because of societal discrimination and marginalization, it is always challenging for LGBT communities to develop regular human ties, and as a result, they frequently struggle with autism and even depression, raising concerns about their psychological wellbeing (130). According to available studies, the effect of LGBT group psychological wellbeing issues, cancer, and HIV/AIDS on LGBT community psychological wellbeing has piqued the interest of numerous academics (131, 132). Nevertheless, actual studies on the psychological wellbeing of LGBT cancer and HIV/AIDS sufferers are scarce. The researcher examined just over a hundred datasets, including Google Academic and Web of Science. Twenty-seven meta-analyses evaluating the effect of inflammation and fibrosis on the psychological wellbeing of the LGBT community were performed, omitting certain prospective studies and inadequate data reporting. A meta-analysis of the effect of inflammation and fibrosis on LGBT community psychological wellbeing was conducted on 33 of them.

Based on the findings, the ultimate overall cancer test has a Z-value = 86.58 and a p < 0.0001. LGBT cancer sufferers had a substantially higher score than overall LGBT participants. Cancer-related inflammation and fibrosis have a detrimental effect on the psychological wellbeing of LGBT patients. Moreover, the ultimate HIV/AIDS overall test results show a Z-value of 268.40 and a P < 0.1, HIV/AIDS sufferers with LGBT scores are substantially higher than participants from the general LGBT category, and inflammation and fibrosis in cancer have a substantial adverse effect on the psychological wellbeing of LGBT sufferers.

Results

Using a total of 48 entries from Google academic, the Web of Science, and the paper's citations, we discovered 370 articles that were connected to the research. Thirty-nine of the studies were retrospective, while the remaining 27 were prospective. They focused on 9,898 pieces of information regarding the psychological health of LGBT cancer patients and 14,465 cancer patients with HIV/AIDS.

We discovered through meta-analysis that the disparity in psychological wellbeing scores between HIV/AIDS LGBT individuals and the general population ranged between −10.86 and 15. The overall findings revealed a 1.270-point difference in psychological wellbeing scores between the HIV/AIDS LGBT group and the general population (95% confidence interval 0.990–1.560, Z = 86.58 and P < 0.1). The disparity in psychological wellbeing scores between cancer LGBT individuals and the general population ranges between −8.77 and 20.94, according to the 33 papers on the psychological wellbeing of cancer LGBT individuals examined for this study. The overall findings revealed a 12.48-point difference in psychological wellbeing scores between the cancer LGBT subgroup and the general population (95% confidence interval: 10.05–14.92; egger Test Z-value = 268.40; P < 0.1). The aforementioned findings indicate that the inflammation and fibrosis associated with HIV/AIDS and cancer have a significant negative impact on the psychological wellbeing of the LGBT community.

Limitations

This research performed a meta-analysis of the effects of cancer and HIV/AIDS on LGBT sufferers' psychological wellbeing. To begin, it gathered pertinent research evidence through Google Academic and Web of Science. Due to the limited number of participants in this research and the tiny proportion of relevant publications, the researcher chooses 27 of them as meta-analysis samples for HIV/AIDS impact and 34 as meta-analysis samples for cancer impact. We could tell from meta-analysis that inflammation and fibrosis associated with cancer and HIV/AIDS have a substantial detrimental effect on the psychological wellbeing of LGBT people. The primary drawback of this paper is the minimal amount of literature used for the meta-analysis, and it is mostly attributable to the researcher's limited research subjects.

Future implications

The needs and concerns reported by LGBT individuals in the studies included in this systematic review indicate the need for additional research on LGBT HIV/AIDS and cancer care policy and practice. It has been determined that LGBT individuals accept questions about their sexual orientation or gender identity in healthcare settings, which has a positive effect on their behaviors and attitudes regarding healthcare. Inclusive and reflective practitioners in the healthcare system who were proactive in their profession by, for example, recognizing the identities of LGBT people and providing them with specialized cancer care (133). The LGBT patients reported feeling safe and content with the cancer care they received. This suggests that LGBT cancer patients require interventions that are culturally competent. There is a need for care providers to be aware of the potential susceptibility of LGBT cancer patients to specific issues (53).

Concerning their mental health or identity disclosure, it is necessary to develop programs to educate care providers on their responsibility to assist SGM in their gender disclosure and assist them in overcoming adverse experiences. It has been suggested that inclusive language can foster a sense of safety and comfort in individuals who identify as SGM. However, if they wish to maintain their anonymity, this should also be respected (20). Regarding the LGBT community's healthcare disparities, we must direct programs to be cognizant of the issues and concerns they face. More effort is required to educate nurses and other health care professionals about patient care and meet the specific needs of LGBT HIV/AIDS and cancer patients.

Moreover, leadership styles such as transformational leadership and authentic leadership, as well as intersectionality, could be integrated into the cultural opportunities to structure clinical cancer care and address disparities in cancer care experienced by SGM populations. To further improve the health impartiality of SGM, clinicians and researchers require guidance and training regarding the culturally appropriate compilation of sexual orientation and gender identity data and the applicability of this information for cancer prevention, diagnosis, treatment, and survivorship in SGM.

Conclusion

A meta-analysis was conducted to determine the impact of inflammation and fibrosis in HIV/AIDS and cancer on LGBT patients' psychological wellbeing. The study included 55 papers that were deemed relevant by the researcher, who then culled 27 for use in an HIV/AIDS meta-analysis and saved 33 for use in a cancer meta-analysis. The researcher then used stata.16 to evaluate the data. This analysis led to the following conclusions: The inflammation and fibrosis associated with HIV/AIDS and cancer have a negative impact on the psychological wellbeing of LGBT individuals. Moreover, the test for heterogeneity reveals that the findings of 30 publications exhibit substantial heterogeneity. This demonstrates that some research suggests that the effects of HIV/AIDS, inflammation and fibrosis on cancer are negligible, and this could be explained by the use of diverse methods for assessing psychological wellbeing. On the other hand, inflammation and fibrosis continue to have a major detrimental impact on the psychological wellbeing of LGBT individuals with cancer and HIV/AIDS.

Funding

The preparation of this manuscript was partially supported by the funding from the Department of Applied Social Sciences, The Hong Kong Polytechnic University, Hong Kong SAR, China, Research Grants Council of Hong Kong (General Research Fund 14106518, 14111019, 14111720, and Postdoctoral Fellowship Scheme PDFS2122- 4S06), State Key Laboratory of Translational Oncology, The Chinese University of Hong Kong's Faculty Innovation Award (4620528), Direct Grant for Research (4054510 and 4054668), and Postdoctoral Fellowship Scheme 2021-22 (NL/LT/PDFS2022/0360/22lt).

Publisher's note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Statements

Data availability statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/supplementary material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding authors.

Author contributions

Conceptualization: AC, LL, EY, PT and JL. Methodology: AC, LL, and JL. Validation: AC, JL, and JH. Formal analysis: AC, JL, and PT. Investigation and writing—original draft preparation: AC and JL. Data curation: HT, AC, JL, and JH. Visualization: AC, JL, JH, WH, AI, and PT. Supervision: PT and EY. All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

Acknowledgments

AC would like to express his gratitude to Dr. Ben Ku from the Department of Applied Social Sciences, Hong Kong Polytechnic University.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

References

1.

YarchoanRUldrickTS. HIV-Associated Cancers and Related Diseases. N Engl J Med. (2018) 378:1029–41. 10.1056/NEJMra1615896

2.

FrischMBiggarRJEngelsEAGoedertJJAIDS Cancer Match Registry StudyGroupAIDS Cancer Match Registry StudyGroup. Association of cancer with AIDS-related immunosuppression in adults. JAMA. (2001) 285:1736–45. 10.1001/jama.285.13.1736

3.

GillessenSAttardGBeerTMBeltranHBjartellABossiAet al. Management of patients with advanced prostate cancer: report of the advanced prostate cancer consensus conference 2019. Euro Urol. (2020) 77:508–47. 10.1016/j.eururo.2020.01.012

4.

MaSJOladeruOTWangKAttwoodKSinghAKHaas-KoganDAet al. Prostate cancer screening patterns among sexual and gender minority individuals. Euro Urol. (2021) 79:588–92. 10.1016/j.eururo.2020.11.009

5.

Pratt-ChapmanMLGoltzHLatiniDGoerenWSuarezRZhangYet al. Affirming care for sexual and gender minority prostate cancer survivors: results from an online training. J Cancer Educ. (2020) 37:1137–43. 10.1007/s13187-020-01930-y

6.

SutterMESimmonsVNSuttonSKVadaparampilSTSanchezJABowman-CurciMet al. Oncologists' experiences caring for LGBTQ patients with cancer: qualitative analysis of items on a national survey. Pat Educ Counsel. (2021) 104:871–6. 10.1016/j.pec.2020.09.022

7.

JackmanKBBosseJDEliasonMJHughesTL. Sexual and gender minority health research in nursing. Nurs Outlook. (2019) 67:21–38. 10.1016/j.outlook.2018.10.006

8.

WebsterRDrury-SmithH. How can we meet the support needs of LGBT cancer patients in oncology? A systematic review. Radiography. (2021) 27:633–44. 10.1016/j.radi.2020.07.009

9.

MaingiSBagabagAEO'mahonyS. Current best practices for sexual and gender minorities in hospice and palliative care settings. J Pain Symp Manage. (2018) 55:1420–7. 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2017.12.479

10.

HoytMAFrostDMCohnEMillarBMDiefenbachMARevensonTA. Gay men's experiences with prostate cancer: implications for future research. J Health Psychol. (2020) 25:298–310. 10.1177/1359105317711491

11.

ArdKLKeuroghlianAS. Training in sexual and gender minority health—expanding education to reach all clinicians. N Engl J Med. (2018) 379:2388–91. 10.1056/NEJMp1810522

12.

Lelutiu-WeinbergerCPachankisJ. Evaluation of an LGBT-affirmative mental health practice training in a stigmatizing national context. Eur J Public Health. (2018) 28. 10.1093/eurpub/cky212.863

13.

PoteatTGermanDKerriganD. Managing uncertainty: A grounded theory of stigma in transgender health care encounters. Soc Sci Med. (2013) 84:22–9. 10.1016/j.socscimed.2013.02.019

14.

SuenYTChanRCH. A nationwide cross-sectional study of 15,611 lesbian, gay and bisexual people in China: disclosure of sexual orientation and experiences of negative treatment in health care. Int J Equity Health. (2020) 19:1–12. 10.1186/s12939-020-1151-7

15.

SkorskaMNBogaertAF. Fraternal birth order, only-child status, and sibling sex ratio related to sexual orientation in the add health data: a re-analysis and extended findings. Arch Sex Behav. (2020) 49:557–73. 10.1007/s10508-019-01496-x

16.

AllenMSRobsonDA. Personality and sexual orientation: new data and meta-analysis. J Sex Res. (2020) 57:953–65. 10.1080/00224499.2020.1768204

17.

PittmanDMRiedy RushCHurleyKBMingesML. Double jeopardy: intimate partner violence vulnerability among emerging adult women through lenses of race and sexual orientation. J Am Coll Health. (2020) 70:265–73. 10.1080/07448481.2020.1740710

18.

PecoraLAHancockGIHooleyMDemmerDHAttwoodTMesibovGBet al. Gender identity, sexual orientation and adverse sexual experiences in autistic females. Mol Autism. (2020) 11:1–16. 10.1186/s13229-020-00363-0

19.

CandrianCCloyesKG. “She's dying and i can't say we're married?”: end-of-life care for LGBT older adults. Gerontologist. (2020) 61:1197–201. 10.1093/geront/gnaa186

20.

AndersonBTDanforthADaroffRStaufferCEkmanEAgin-LiebesGet al. Psilocybin-assisted group therapy for demoralized older long-term AIDS survivor men: an open-label safety and feasibility pilot study. EClinicalMedicine. (2020) 27:100538. 10.1016/j.eclinm.2020.100538

21.

LusenoWKFieldSHIritaniBJOdongoFSKwaroDAmekNOet al. Pathways to depression and poor quality of life among adolescents in Western Kenya: role of anticipated HIV stigma, HIV risk perception, sexual behaviors. AIDS Behav. (2021) 25:1423–37. 10.1007/s10461-020-02980-5

22.

DomlynAMJiangYHarrisonSQiaoSLiX. Stigma and psychosocial wellbeing among children affected by parental HIV in China. AIDS Care. (2020) 32:500–7. 10.1080/09540121.2019.1687834

23.

AndersonSM. Gender matters: the perceived role of gender expression in discrimination against cisgender and transgender LGBQ individuals. Psychol Women Q. (2020) 44:323–41. 10.1177/0361684320929354

24.

ChiangLHowardAStoebenauKMassettiGMApondiRHegleJet al. Sexual risk behaviors, mental health outcomes and attitudes supportive of wife-beating associated with childhood transactional sex among adolescent girls and young women: findings from the Uganda violence against children survey. PLoS ONE. (2021) 16:e0249064. 10.1371/journal.pone.0249064

25.

RajanSKumarPSangalBKumarARamanathanSAmmassariS. HIV/AIDS-Related risk behaviors, HIV prevalence, and determinants for HIV prevalence among hijra/transgender people in India: findings from the 2014–2015 integrated biological and behavioural surveillance. Indian J Public Health. (2020) 64:53. 10.4103/ijph.IJPH_55_20

26.

TamCCBenotschEGLiX. Sexual enhancement expectancy, non-medical use of prescription drugs, and sexual risk behaviors in college students. Subst Abuse. (2020) 42:577–86. 10.1080/08897077.2020.1803177

27.

LiLLeeS.-J.JiraphongsaCKhumtongSLamsirithawornSet alImproving the health and mental health of people living with HIV/AIDS:12-month assessment of a behavioral intervention in Thailand. Am J Public Health. (2010) 100:2418–25. 10.2105/AJPH.2009.185462

28.

SeayJHicksAMarkhamMJSchlumbrechtMBowman-CurciMWoodardJet al. Web-based LGBT cultural competency training intervention for oncologists: pilot study results. Cancer. (2020) 126:112–20. 10.1002/cncr.32491

29.

MengJRainsSAAnZ. How cancer patients benefit from support networks offline and online: extending the model of structural-to-functional support. Health Commun. (2021) 36:198–206. 10.1080/10410236.2019.1673947

30.

CataldiSAmatoAMessinaGIovaneAGrecoGGuariniAet al. Effects of combined exercise on psychological and physiological variables in cancer patients: a pilot study. Acta Medica. (2020) 36:1105–33. 10.19193/0393-6384_2020_2_174

31.

DeimlingGTBowmanKFSternsSWagnerLJKahanaB. Cancer-related health worries and psychological distress among older adult, long-term cancer survivors. Psycho Oncol. (2006) 15:306–20. 10.1002/pon.955

32.

SardellaALenzoVBonannoGAMartinoGBasileGQuattropaniMC. Dispositional optimism and context sensitivity: psychological contributors to frailty status among elderly outpatients. Front Psychol. (2021) 11:3934. 10.3389/fpsyg.2020.621013

33.

SitanggangJSSiregarKBSitanggangHHVinolinaNS. Prevalence and characteristics of cancer patients with COVID-19: a meta-analysis study. F1000Research. (2021) 10:975. 10.12688/f1000research.53539.1

34.

PutriDSRMakiyahSNN. Factors affecting sleep quality of breast cancer patients with chemotherapy. Open Access Macedon J Med Sci. (2021) 9:130–6. 10.3889/oamjms.2021.5816

35.

YektatalabSGhanbariE. The relationship between anxiety and self-esteem in women suffering from breast cancer. J Mid Life Health. (2020) 11:126. 10.4103/jmh.JMH_140_18

36.

Perez-TejadaJAizpurua-PerezILabakaAVegasOUgartemendiaGArregiA. Distress, proinflammatory cytokines and self-esteem as predictors of quality of life in breast cancer survivors. Physiol Behav. (2021) 230:113297. 10.1016/j.physbeh.2020.113297

37.

Ristevska-DimitrovskaGBaticD. The impact of COVID-19 on mental health of healthcare workers and police/army forces in the Republic of North Macedonia. Euro Neuropsychopharmacol. (2020) 40:S479. 10.1016/j.euroneuro.2020.09.622

38.

ChanASWLoIPYYanE. Health and social inclusion: The impact of psychological well-being and suicide attempts among older men who have sex with men. Am J Men Health. (2022) 16:15579883221120985. 10.1177/15579883221120985

39.

JinXSenaratneSPereraSFuYAntalaL. Cause, effect, and alleviation of stress for project management practitioners in the built environment: a conceptual framework. In: ICCREM 2020 Intelligent Construction and Sustainable Buildings. Reston, VA: American Society of Civil Engineers (2020). p. 622–31. 10.1061/9780784483237.073

40.

Van EgmondMAEngelbertRHKlinkenbijlJHvan Berge HenegouwenMIVan Der SchaafM. Physiotherapy with telerehabilitation in patients with complicated postoperative recovery after esophageal cancer surgery: feasibility study. J Med Internet Res. (2020) 22:e16056. 10.2196/16056

41.

GarnerHde VisserKE. Immune crosstalk in cancer progression and metastatic spread: a complex conversation. Nat Rev Immunol. (2020) 20:483–97. 10.1038/s41577-019-0271-z

42.

ChaudhuryPBanerjeeD. “Recovering with nature”: a review of ecotherapy and implications for the COVID-19 pandemic. Front Public Health. (2020) 8:604440. 10.3389/fpubh.2020.604440

43.

GuidiJFavaGA. The emerging role of euthymia in psychotherapy research and practice. Clin Psychol Rev. (2020) 82:101941. 10.1016/j.cpr.2020.101941

44.

NnateDAAnyachukwuCCIgweSEAbaraoguUO. Mindfulness-based interventions for psychological wellbeing and quality of life in men with prostate cancer: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Psycho Oncol. (2021) 30:1680–90. 10.1002/pon.5749

45.

MadanASiglinJKhanA. Comprehensive review of implications of COVID-19 on clinical outcomes of cancer patients and management of solid tumors during the pandemic. Cancer Med. (2020) 9:9205–18. 10.1002/cam4.3534

46.

DreherMC. Remaking a life: how women living with HIV/AIDS confront inequality: celeste watkins-hayes. J Assoc Nurses AIDS Care. (2020) 31:197–8. 10.1097/JNC.0000000000000151

47.

WangZZhangRGongZLiuLShenYChenJet al. Real-world outcomes of AIDS-related Burkitt lymphoma: a retrospective study of 78 cases over a 10-year period. Int J Hematol. (2021) 113:903–9. 10.1007/s12185-021-03101-1

48.

AjayiAIAwopegbaOEAdeagboOAUshieBA. Low coverage of HIV testing among adolescents and young adults in Nigeria: implication for achieving the UNAIDS first 95. PLoS ONE. (2020) 15:e0233368. 10.1371/journal.pone.0233368

49.

MarbaniangISangleSNimkarSZarekarKSalviSChavanAet al. The burden of anxiety among people living with HIV during the COVID-19 pandemic in Pune, India. BMC Public Health. (2020) 20:1598. 10.1186/s12889-020-09656-8

50.

DwyerJBAftabARadhakrishnanRWidgeARodriguezCICarpenterLLet al. Hormonal treatments for major depressive disorder: state of the art. Am J Psychiatry. (2020) 177:686–705. 10.1176/appi.ajp.2020.19080848

51.

AlikhaniMEbrahimiAFarniaVKhazaieHRadmehrFMohamadiEet al. Effects of treatment of sleep disorders on sleep, psychological and cognitive functioning and biomarkers in individuals with HIV/AIDS and under methadone maintenance therapy. J Psychiatr Res. (2020) 130:260–72. 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2020.07.043

52.

SenthilkumarASubithaLSaravananEGiriyappaDKSatheeshSMenonV. Depressive Symptoms and health-related quality of life in patients with cardiovascular diseases attending a tertiary care hospital, Puducherry—a cross-sectional study. J Neurosci Rural Pract. (2021) 12:376–81. 10.1055/s-0041-1724227

53.

DewiDMSKSariJDEFatahMZAstutikE. Stigma and discrimination against people living with HIV and AIDS in Banyuwangi, East Java, Indonesia. In: 4th International Symposium on Health Research (ISHR 2019). Atlantis Press (2020). p. 154–9. 10.2991/ahsr.k.200215.030

54.

MeoCMSukartiniTMisutarnoM. Social support for HIV AIDS sufferers who experience stigma and discrimination: a systematic review. STRADA J Ilmiah Kesehatan. (2021) 10:1174–85. 10.30994/sjik.v10i1.727

55.

SindarrehSEbrahimiFNasirianM. Stigma and discrimination in the view of people living with human immunodeficiency virus in Isfahan, Iran. HIV & AIDS Rev Int J HIV-Relat Prob. (2020) 19:132–8. 10.5114/hivar.2020.96489

56.

ChanASWWuDLoIPYHoJMCYanE. Diversity and inclusion: Impacts on psychological wellbeing among lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, and queer communities. Front Psychol. (2022) 13:726343. 10.3389/fpsyg.2022.726343

57.

LiYZhangXWLiaoBLiangJHeWJLiuJet al. Social support status and associated factors among people living with HIV/AIDS in Kunming city, China. BMC Public Health. (2021) 21:1413. 10.1186/s12889-021-11253-2

58.

MurariuAHanganuCLiviaBOBUStafieCSSavinCAl HageWEet al. Ethical issues, discrimination and social responsibility related to HIV-infected patients. Rev Cercetare Interv Soc. (2021) 72:311. 10.33788/rcis.72.19

59.

ChanASWTangPMKYanE. Chemsex and its risk factors associated with human immunodeficiency virus among men who have sex with men in Hong Kong. World J Virol. (2022) 11:208–11. 10.5501/wjv.v11.i4.208

60.

Koseoglu OrnekOTabakFMeteB. Stigma in hospital: an examination of beliefs and attitudes towards HIV/AIDS patients, Istanbul. AIDS Care. (2020) 32:1045–51. 10.1080/09540121.2020.1769833

61.

TomarASpadineMNGraves-BoswellTWigfallLT. COVID-19 among LGBTQ+ individuals living with HIV/AIDS: Psycho-social challenges and care options. AIMS Public Health. (2021) 8:303–8. 10.3934/publichealth.2021023

62.

LuoRSilenzioVHuangYChenXLuoD. The disparities in mental health between gay and bisexual men following positive HIV diagnosis in China: a one-year follow-up study. Int J Environ Res Public Health. (2020) 17:3414. 10.3390/ijerph17103414

63.

LogieCHPerez-BrumerAMothopengTLatifMRanotsiABaralSD. Conceptualizing LGBT stigma and associated HIV vulnerabilities among LGBT persons in Lesotho. AIDS Behav. (2020) 24:3462–72. 10.1007/s10461-020-02917-y

64.

XiongCBiscardiMAstellANalderECameronJIMihailidisAet al. Sex and gender differences in caregiving burden experienced by family caregivers of persons with dementia: a systematic review. PLoS ONE. (2020) 15:e0231848. 10.1371/journal.pone.0231848

65.

ZhangYAminSLungKISeaburySRaoNToyBC. Incidence, prevalence, and risk factors of infectious uveitis and scleritis in the United States: a claims-based analysis. PLoS ONE. (2020) 15:e0237995. 10.1371/journal.pone.0237995

66.

Nakimuli-MpunguEMusisiSSmithCMVon IsenburgMAkimanaBShakarishviliAet al. Mental health interventions for persons living with HIV in low-and middle-income countries: a systematic review. J Int AIDS Soc. (2021) 24:e25722. 10.1002/jia2.25722

67.

St-JeanMTafessuHClossonKPattersonTLLavergneMRElefanteJet al. The syndemic effect of HIV/HCV co-infection and mental health disorders on acute care hospitalization rate among people living with HIV/AIDS: a population-based retrospective cohort study. Can J Public Health. (2019) 110:779–91. 10.17269/s41997-019-00253-w

68.

PhilpotSPHoltMMurphyDHaireBPrestageGMaherLet al. Qualitative Findings on the Impact of COVID-19 Restrictions on Australian Gay and Bisexual Men: Community Belonging and Mental Well-being. Qual Health Res. (2021) 31:2414–25. 10.1177/10497323211039204

69.

LiboroRMYatesTCBellSRanuschioBDa SilvaGFehrCet al. Protective factors that foster resilience to HIV/AIDS: Insights and lived experiences of older gay, bisexual, and other men who have sex with men. Int J Environ Res Public Health. (2021). 18:8548. 10.3390/ijerph18168548

70.

GonzalesGNavazaB. Lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender (LGBT) health in Cuba: A report from the field. J Health Care Poor Underserved. (2021) 32:30–6. 10.1353/hpu.2021.0005

71.

FreeseTEPadwaHOeserBTRutkowskiBASchulteMT. Real-world strategies to engage and retain racial-ethnic minority young men who have sex with men in HIV prevention services. AIDS Patient Care STDS. (2017) 31:275–81. 10.1089/apc.2016.0310

72.

BatchelderAWSafrenSMitchellADIvardicIO'CleirighC. Mental health in 2020 for men who have sex with men in the United States. Sex Health. (2017) 14:59–71. 10.1071/SH16083

73.

WilsonPAValeraPMartosAJWittlinNMMuñoz-LaboyMAParkerRG. Contributions of qualitative research in informing HIV/AIDS interventions targeting black msm in the United States. J Sex Res. (2016) 53:642-54. 10.1080/00224499.2015.1016139

74.

Rodríguez-DíazCEJovet-ToledoGGVélez-VegaCMOrtiz-SánchezEJSantiago-RodríguezEIVargas-MolinaRLet al. Discrimination and health among lesbian, gay, bisexual and trans people in Puerto Rico. P R Health Sci J. (2016) 35:154-9.

75.

LiboroRMWalshRT. Understanding the irony: Canadian gay men living with HIV/AIDS, their catholic devotion, and greater well-being. J Relig Health. (2016) 55:650–70. 10.1007/s10943-015-0087-5

76.

DowshenNMatoneMLuanXLeeSBelzerMFernandezMIet al. Behavioral and health outcomes for HIV+ young transgender women (ytw) linked to and engaged in medical care. LGBT Health. (2016) 3:162–7. 10.1089/lgbt.2014.0062

77.

SwartzJA. The relative odds of lifetime health conditions and infectious diseases among men who have sex with men compared with a matched general population sample. Am J Mens Health. (2015) 9:150–62. 10.1177/1557988314533379

78.

LewisNMBauerGRColemanTABlotSPughDFraserMet al. Community cleavages: Gay and bisexual men's perceptions of gay and mainstream community acceptance in the post-aids, post-rights era. J Homosex. (2015) 62:1201–27. 10.1080/00918369.2015.1037120

79.

Jadwin-CakmakLAPingelESHarperGWBauermeisterJA. Coming out to dad: Young gay and bisexual men's experiences disclosing same-sex attraction to their fathers. Am J Mens Health. (2015) 9:274–88. 10.1177/1557988314539993

80.

Garland-ForsheeRYFialaSCNgoDLMoseleyK. Sexual orientation and sex differences in adult chronic conditions, health risk factors, and protective health practices, Oregon, 2005-2008. Prev Chronic Dis. (2014) 11:E136. 10.5888/pcd11.140126

81.

DiNapoliJMGarcia-DiaMJGarcia-OnaLO'FlahertyDSillerJA. theory-based computer mediated communication intervention to promote mental health and reduce high-risk behaviors in the LGBT population. Appl Nurs Res. (2014) 27:91–3. 10.1016/j.apnr.2013.10.003

82.

CoulterRWSKenstKSBowenDJScout. Research funded by the National Institutes of Health on the health of lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender populations. Am J Public Health. (2014) 104:e105–12. 10.2105/AJPH.2013.301501

83.

CahillSMakadonH. Sexual orientation and gender identity data collection in clinical settings and in electronic health records: A key to ending LGBT health disparities. LGBT Health. (2014) 1:34–41. 10.1089/lgbt.2013.0001

84.

HergenratherKCGeisheckerSClarkGRhodesSD. A pilot test of the HOPE Intervention to explore employment and mental health among African American gay men living with HIV/AIDS: Results from a CBPR study. AIDS Educ Prev. (2013) 25:405-22. 10.1521/aeap.2013.25.5.405

85.

GreyJARobinsonBBEColemanEBocktingWO. A systematic review of instruments that measure attitudes toward homosexual men. J Sex Res. (2013) 50:329–52. 10.1080/00224499.2012.746279

86.

Brennan DJ Emlet CA Brennenstuhl S Rueda S OHTN Cohort Study Research Team and Staff. Socio-demographic profile of older adults with HIV/AIDS: gender and sexual orientation differences. Can J Aging. (2013) 32:31–43. 10.1017/S0714980813000068

87.

WightRGLeBlancAJde VriesBDetelsR. Stress and mental health among midlife and older gay-identified men. Am J Public Health. (2012) 102:503–10. 10.2105/AJPH.2011.300384

88.

HaileRPadillaMBParkerEA. 'Stuck in the quagmire of an HIV ghetto': the meaning of stigma in the lives of older black gay and bisexual men living with HIV in New York City. Cult Health Sex. (2011) 13:429-42. 10.1080/13691058.2010.537769

89.

PantaloneDWHesslerDMSimoniJM. Mental health pathways from interpersonal violence to health-related outcomes in HIV-positive sexual minority men. J Consult Clin Psychol. (2010) 78(3):387-97.

90.

TrittRJ. [Introduction to LGBT: definitions, some historical facts, and evolution of thinking in the era of HIV/AIDS–hopes and challenges]. Ann Acad Med Stetin. (2010) 56:126–30. 10.1037/a0019307

91.

McDowellTLSerovichJM. The effect of perceived and actual social support on the mental health of HIV-positive persons. AIDS Care. (2007) 19:1223–9. 10.1080/09540120701402830

92.

Courtenay-QuirkCWolitskiRJParsonsJTGómezCA; Seropositive Urban Men's Study Team. Is HIV/AIDS stigma dividing the gay community? Perceptions of HIV-positive men who have sex with men. AIDS Educ Prev. (2006) 18:56-67. 10.1521/aeap.2006.18.1.56

93.

WilsonPAYoshikawaH. Experiences of and responses to social discrimination among Asian and Pacific Islander gay men: their relationship to HIV risk. AIDS Educ Prev. (2004) 16:68–83. 10.1521/aeap.16.1.68.27724

94.

RhotenBBurkhalterJEJooRMujawarIBrunerDScoutNet al. Impact of an LGBTQ cultural competence training program for providers on knowledge, attitudes, self-efficacy, and intensions. J Homosex. (2022) 69:1030–41. 10.1080/00918369.2021.1901505

95.

FeitNZWangZDemetresMRDrenisSAndreadisKRameauA. healthcare disparities in laryngology: A scoping review. Laryngoscope. (2022) 132:375–90. 10.1002/lary.29325

96.

ChengPJ. Sexual dysfunction in men who have sex with men. Sex Med Rev. (2022) 10:130–41. 10.1016/j.sxmr.2021.01.002

97.

WatersARTennantKCloyesKG. Cultivating LGBTQ+ competent cancer research: Recommendations from LGBTQ+ cancer survivors, care partners, and community advocates. Semin Oncol Nurs. (2021) 37:151227. 10.1016/j.soncn.2021.151227

98.

SkórzewskaMKurylcioARawicz-PruszyńskiKChumpiaWPunnananBJirapongvanichSet al. Impact of mastectomy on body image and sexuality from a LGBTQ perspective: A narrative review. J Clin Med. (2021) 10:567. 10.3390/jcm10040567

99.

MulhollandHMcIntyreJCHaines-DelmontAWhittingtonRComerfordTCorcoranR. Investigation to identify individual socioeconomic and health determinants of suicidal ideation using responses to a cross-sectional, community-based public health survey. BMJ Open. (2021) 11:e035252. 10.1136/bmjopen-2019-035252

100.

MessinaMPD'AngeloAGiovagnoliRNapolitanoMPetrellaCRalliMet al. Cancer screenings among sexual and gender minorities by midwives' point of view. Minerva Obstet Gynecol. (2021). 10.23736/S2724-606X.21.04802-8 [Epub ahead of print].

101.

DrysdaleKCamaEBotfieldJBearBCerioRNewmanCE. Targeting cancer prevention and screening interventions to LGBTQ communities: A scoping review. Health Soc Care Community. (2021) 29:1233–48. 10.1111/hsc.13257

102.

DesaiMJGoldRSJonesCKDinHDietzACShliakhtsitsavaKet al. Mental health outcomes in adolescent and young adult female cancer survivors of a sexual minority. J Adolesc Young Adult Oncol. (2021) 10:148–55. 10.1089/jayao.2020.0082

103.

CloyesKGCandrianC. Palliative and end-of-life care for sexual and gender minority cancer survivors: A review of current research and recommendations. Curr Oncol Rep. (2021) 23:39. 10.1007/s11912-021-01034-w

104.

ChidiacCGraysonKAlmackK. Development and evaluation of an LGBT+ education programme for palliative care interdisciplinary teams. Palliat Care Soc Pract. (2021) 15:26323524211051388. 10.1177/26323524211051388

105.

BurkiTK. The challenges of cancer care for the LGBTQ+ community. Lancet Oncol. (2021) 22:1061. 10.1016/S1470-2045(21)00389-2

106.

BernerAMWebsterRHughesDJTharmalingamHSaundersDJ. Education to improve cancer care for LGBTQ+ patients in the UK. Clin Oncol (R Coll Radiol). (2021) 33:270–3. 10.1016/j.clon.2020.12.012

107.

AustriaMDLynchKLeTWaltersCBAtkinsonTMVickersAJet al. Sexual and gender minority persons' perception of the female sexual function index. J Sex Med. (2021) 18:2020–7. 10.1016/j.jsxm.2021.09.012

108.

SutterMEBowman-CurciMLArevaloLFDSuttonSKQuinnGPSchabathMBet al. survey of oncology advanced practice providers' knowledge and attitudes towards sexual and gender minorities with cancer. J Clin Nurs. (2020) 29:2953–66. 10.1111/jocn.15302

109.

SheehanEBennettRLHarrisMChan-SmutkoG. Assessing transgender and gender non-conforming pedigree nomenclature in current genetic counselors' practice: The case for geometric inclusivity. J Genet Couns. (2020) 29:1114–25. 10.1002/jgc4.1256

110.

PeitzmeierSMBernsteinIMMcDowellMJPardeeDJAgénorMAlizagaNMet al. Enacting power and constructing gender in cervical cancer screening encounters between transmasculine patients and health care providers. Cult Health Sex. (2020) 22:1315–32. 10.1080/13691058.2019.1677942

111.

OzkaraSan E. The influence of the oncology-focused transgender-simulated patient simulation on nursing students' cultural competence development. Nurs Forum. (2020) 55:621–30. 10.1111/nuf.12478

112.

McInnisMKPukallCF. Sex after prostate cancer in gay and bisexual men: A review of the literature. Sex Med Rev. (2020) 8:466–72. 10.1016/j.sxmr.2020.01.004

113.

KanoMSanchezNTamí-MauryISolderBWattGChangS. Addressing cancer disparities in sgm populations: recommendations for a national action plan to increase sgm health equity through researcher and provider training and education. J Cancer Educ. (2020) 35:44–53. 10.1007/s13187-018-1438-1

114.

HavilandKSSwetteSKelechiTMuellerM. Barriers and facilitators to cancer screening among LGBTQ individuals with cancer. Oncol Nurs Forum. (2020) 47:44–55. 10.1188/20.ONF.44-55

115.

GrassoCGoldhammerHBrownRJFurnessBW. Using sexual orientation and gender identity data in electronic health records to assess for disparities in preventive health screening services. Int J Med Inform. (2020) 142:104245.

116.

CattelanLGhazawiFMLeMSavinEZubarevALagacéFet al. Investigating epidemiologic trends and the geographic distribution of patients with anal squamous cell carcinoma throughout Canada. Curr Oncol. (2020) 27:e294–306. 10.3747/co.27.6061

117.

BernerAMHughesDJTharmalingamHBakerTHeyworthBBanerjeeSet al. An evaluation of self-perceived knowledge, attitudes and behaviours of UK oncologists about LGBTQ+ patients with cancer. ESMO Open. (2020) 5:e000906. 10.1136/esmoopen-2020-000906

118.

ArnoldEDhingraN. Health care inequities of sexual and gender minority patients. Dermatol Clin. (2020) 38:185-90. 10.1016/j.det.2019.10.002

119.

StevensEEAbrahmJL. Adding silver to the rainbow: Palliative and end-of-life care for the geriatric LGBTQ patient. J Palliat Med. (2019) 22:602–6. 10.1089/jpm.2018.0382

120.

SchabathMBBlackburnCASutterMEKanetskyPAVadaparampilSTSimmonsVNet al. National survey of oncologists at national cancer institute-designated comprehensive cancer centers: Attitudes, knowledge, and practice behaviors about LGBTQ patients with cancer. J Clin Oncol. (2019) 37:547–58. 10.1200/JCO.18.00551

121.

RiceD. LGBTQ: The communities within a community. Clin J Oncol Nurs. (2019) 23:668–71. 10.1188/19.CJON.668-671

122.

KamenCSAlpertAMargoliesLGriggsJJDarbesLSmith-StonerMet al. “Treat us with dignity”: a qualitative study of the experiences and recommendations of lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, and queer (LGBTQ) patients with cancer. Support Care Cancer. (2019) 27:2525–32. 10.1007/s00520-018-4535-0

123.

Cathcart-RakeEJBreitkopfCRKaurJO'ConnorJRidgewayJLJatoiA. Teaching health-care providers to query patients with cancer about sexual and gender minority (SGM) status and sexual health. Am J Hosp Palliat Care. (2019) 36:533–7. 10.1177/1049909118820874

124.

TamargoCLQuinnGPSanchezJASchabathMB. Cancer and the LGBTQ population: Quantitative and qualitative results from an oncology providers' survey on knowledge, attitudes, and practice behaviors. J Clin Med. (2017) 6:93. 10.3390/jcm6100093

125.

RussellAMGalvinKMHarperMMClaymanML. Erratum to: A comparison of heterosexual and LGBTQ cancer survivors' outlooks on relationships, family building, possible infertility, and patient-doctor fertility risk communication. J Cancer Surviv. (2016) 10:943. 10.1007/s11764-016-0534-7

126.

BradleyCIlieGMacDonaldCMassoeursLCam-TuJDRutledgeRDH. Treatment regret, mental and physical health indicators of psychosocial well-being among prostate cancer survivors. Curr Oncol. (2021) 28:3900–17. 10.3390/curroncol28050333

127.

MorrowMKhanAJ. Locoregional management after neoadjuvant chemotherapy. J Clin Oncol. (2020) 38:2281. 10.1200/JCO.19.02576

128.

SatrianegaraMFMallongiA. Analysis of cancer patients characteristics and the self-ruqyah treatment to the patients spiritual life quality. Open Access Macedon J Med Sci. (2020) 8:224–8. 10.3889/oamjms.2020.5238

129.

KoetheJRLagathuCLakeJEDomingoPCalmyAFalutzJet al. HIV and antiretroviral therapy-related fat alterations. Nat Rev Dis Primers. (2020) 6:1–20. 10.1038/s41572-020-0181-1

130.

FuchsMAMultaniAGMayerKHKeuroghlianAS. Anal cancer screening for HIV-negative men who have sex with men: making clinical decisions with limited data. LGBT Health. (2021) 8:317–21. 10.1089/lgbt.2020.0257

131.

LoebAJWardellDJohnsonCM. Coping and healthcare utilization in LGBTQ older adults: a systematic review. Geriatr Nurs. (2021) 42:833–42. 10.1016/j.gerinurse.2021.04.016

132.

SriningsihRPutraAAYuniartiESolehM. Construction of mathematical model between HIV-AIDS and lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender (LGBT) transmission in a population. J Phys. (2020) 1554:012055. 10.1088/1742-6596/1554/1/012055

133.

BoehmerU. LGBT populations' barriers to cancer care. Semin Oncol Nurs. (2018) 34:21–9. 10.1016/j.soncn.2017.11.002

Summary

Keywords

HIV/AIDS, cancer, psychological wellbeing, sexual minorities, patient care, LGBT, health care strategies

Citation

Chan ASW, Leung LM, Li JSF, Ho JMC, Tam HL, Hsu WL, Iu ANOS, Tang PMK and Yan E (2022) Impacts of psychological wellbeing with HIV/AIDS and cancer among sexual and gender minorities: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Front. Public Health 10:912980. doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2022.912980

Received

06 May 2022

Accepted

27 October 2022

Published

18 November 2022

Volume

10 - 2022

Edited by

Roberto Nuevo, Rey Juan Carlos University, Spain

Reviewed by

Tushar Singh, Banaras Hindu University, India; Sushma Kumari, Defense Institute of Psychological Research (DIPR), India; Shalini Mittal, Amity Insitute of Psychology and Allied Sciences, India; Harleen Kaur, Banaras Hindu University, India, in collaboration with reviewer TS

Updates

Copyright

© 2022 Chan, Leung, Li, Ho, Tam, Hsu, Iu, Tang and Yan.

This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Alex Siu Wing Chan chansw.alex@gmail.com; alexsw.chan@connect.polyu.hkElsie Yan elsie.yan@polyu.edu.hkPatrick Ming Kuen Tang patrick.tang@cuhk.edu.hk

†These authors share first authorship

This article was submitted to Public Mental Health, a section of the journal Frontiers in Public Health

‡ORCID: Alex Siu Wing Chan orcid.org/0000-0003-4420-8789

Patrick Ming Kuen Tang orcid.org/0000-0002-3194-3736

Elsie Yan orcid.org/0000-0002-0604-6259

Disclaimer

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.