- 1Hypertension Prevention and Treatment Centre of Henan Province, Fuwai Central China Cardiovascular Hospital, Zhengzhou, China

- 2Community Health Centre of Chaohe, Zhengzhou, China

- 3School of Medicine and Health, Technical University of Munich, Munich, Germany

- 4Zhengzhou Community Health Association, Zhengzhou, China

- 5Grassroots Health and Health Department, Health Commission of Henan Province, Zhengzhou, China

- 6Department of Pharmacy, Fuwai Central China Cardiovascular Hospital, Zhengzhou, China

- 7Department of Pharmacy, Henan Provincial People's Hospital, Zhengzhou, China

- 8Centre for Community Child Health, Murdoch Children's Research Institute, Melbourne, VIC, Australia

- 9Department of Pediatrics, University of Melbourne, Melbourne, VIC, Australia

Background: The relationship between personal health literacy and health outcomes is clear, but the role of health literacy environments is often overlooked. This study examined associations between personal health literacy, school health literacy environments and health outcomes among schoolteachers.

Methods: A cross-sectional study was conducted among 7,364 schoolteachers in Zhengzhou, China. Personal health literacy was measured by the Health Literacy Population Survey 2019–2021 (excellent/sufficient/problematic/inadequate) and school health literacy environments were measured by the Organisational Health Literacy of School Questionnaire (supportive/less supportive). Health outcomes included health status (poor/good), health-compromising behaviours (yes/no), health service use (yes/no), and healthcare cost (≥RMB 1,000/<RMB 1,000).

Results: Over half of teachers had inadequate or problematic health literacy. Teachers with inadequate health literacy had higher odds of poor health status, health-compromising behaviour, health service use, and high healthcare cost than those with excellent health literacy. Similarly, teachers who perceived less supportive school health literacy environments had higher odds of poor health outcomes.

Conclusion: Both personal health literacy and school health literacy environments are important to schoolteachers' health outcomes. Educational programs and organisational change are needed to improve personal health literacy and school environments to improve schoolteachers' health and wellbeing.

1 Introduction

Health literacy is a fundamental determinant of health (1). Extant literature has shown that low health literacy is associated with a range of negative health outcomes, including poor health status, health-compromising behaviours, more health service use, and high healthcare costs (2). In the global health promotion agenda from the World Health Organization (3), addressing low health literacy is a part of the strategy to address population health inequities. Many national governments and international organisations have integrated health literacy into their health agendas and initiatives and even developed national action plans to improve population health literacy and reduce health disparities (3, 4).

Health literacy is about how an individual manages health information in everyday life to make critical health judgments and inform healthy behaviours (5, 6). However, health literacy goes beyond the individual and should be understood as an interactive outcome between personal health skills and the broad environment in which an individual lives. The Australian Commission on Safety and Quality in Health Care defines health literacy as comprising two components (7): personal health literacy that represents one's ability to access, understand, appraise, and apply health information to maintain and improve personal health, and health literacy environments which refer to the systems and relationships that influence how health information is communicated.

Currently, there have been a number of studies that examine the measures, levels, influencing factors, and impact of personal health literacy across populations and contexts (2, 8, 9). Findings from the 2019–2021 European health literacy survey showed that low health literacy was prevalent across countries, ranging from 25% in Slovakia to 72% in Germany (9). In Southeast Asian countries, the prevalence of low health literacy ranged from 6.0% to 94.2% (10). In China, the 2021 national health literacy survey showed 65.9% of Chinese residents aged 15–69 years had low health literacy (11). However, most existing studies focus on personal health literacy in adults, neglecting the role of health literacy environments, which are an integral part of understanding health literacy in its fullest sense. This is more so true when it comes to children and settings relevant to their health and health literacy (12). Addressing this issue requires considering certain professionals working in school such as schoolteachers.

Schoolteachers play a crucial role in shaping the intellectual and emotional development of school-aged children, but also in the development of children's health literacy (13). They are uniquely positioned to deliver health education, equipping children with essential health knowledge, attitudes, and behaviours. In addition, they often engage with families and communities (12), creating a holistic approach to developing children's health literacy that extends beyond the classroom. Understanding schoolteachers' health literacy is of paramount importance as it not only influences their own health and wellbeing, but also influences the way they provide health education, thus impacting children's health literacy (13).

Schools are formal educational organisations and offer infrastructures, resources, and environments that can enable the success of health education (12), and in particular regarding school health literacy environments (14). The Health Promoting School (HPS) framework highlights five key action areas of health promotion in school settings (15): (i) building healthy public policy, (ii) creating supportive environments for health, (iii) strengthening community action for health, (iv) developing personal skills, and (v) re-orienting health services. Empirical evidence shows that all these components have a critical role in equipping both children's and schoolteachers' health literacy and fostering their health and wellbeing (16, 17). Understanding school health literacy environments is crucial for identifying possible ways to better support children's and schoolteachers' health and wellbeing.

Although it has been raised more than two decades (13), schoolteachers' health literacy has only gained increasing attention as part of school health promotion programs in the last decade (13, 18). Findings from previous national (19) and international studies (20–22) showed that schoolteachers' health literacy was generally low and there were disparities in health literacy by sociodemographics such as age, gender, and marital status. However, very few studies have examined the association between schoolteachers' health literacy and health outcomes (16). Furthermore, the role of school health literacy environments is often overlooked. To fill these gaps, the present study aimed to investigate the associations of personal health literacy and school health literacy environments with schoolteachers' health outcomes.

2 Materials and methods

2.1 Study design and settings

A cross-sectional study was designed to recruit teachers from 11 schools (five urban and six rural) in Zhengzhou, Henan Province, China, using convenience cluster sampling. In brief, two districts (Jingkai District/Zhongmou County) were selected according to their socioeconomic levels, one representing high and the other representing low. Based on previous successful collaborations with schools, we selected five or six schools in each district (Jingkai District: three primary schools and two middle schools; Zhongmou County: four primary schools and two middle schools). At each school, all teaching staff were invited to complete an online self-administered questionnaire via Wenjuanxing. Participants received written online information about the study in Chinese. Informed consent was obtained from all respondents prior to filling out the questionnaire. Based on previous prevalence studies in Chinese teachers (23) and sample size calculation formula [], we estimated a sample size of at least 232 in each district (where p = 0.185, z = 1.96, e = 0.05). Considering the potential non-response rate of 30%, the final sample size should be at least 664. Data collection was undertaken between 20 September 2022 and 13 June 2023. We used the Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) checklist as guidelines to ensure the reporting quality of the present study (see Supplementary Table S1).

2.2 The questionnaire

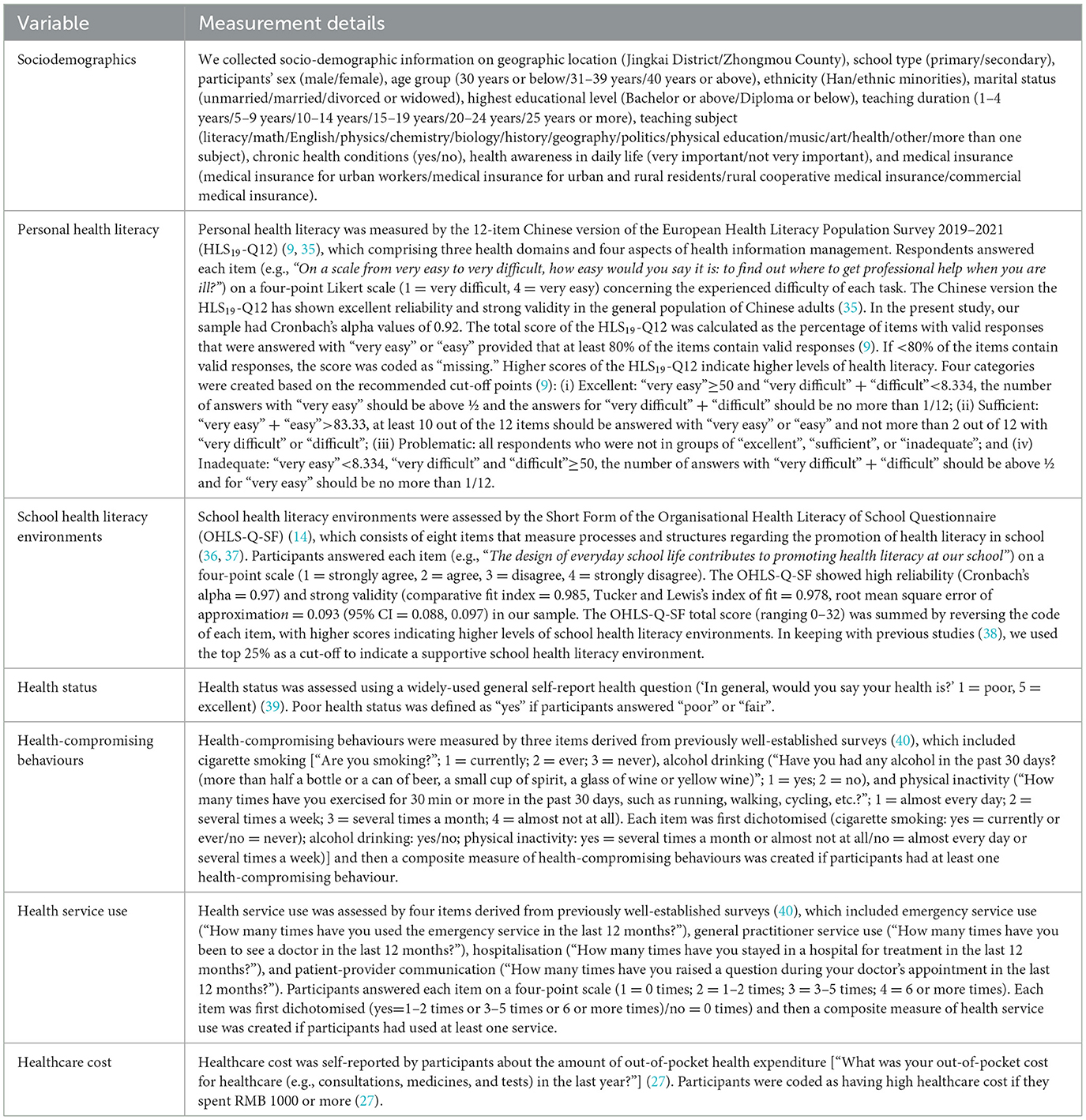

Data collected included key sociodemographics, personal health literacy, school health literacy environments, and health outcomes (see Table 1 for measurement details). In total, there were four parts in this questionnaire (Part 1: You and Your Family; Part 2: Your Health Literacy; Part 3: Your School; Part 4: Your Personal Health), with each part having 8–12 questions. The average time to complete the survey was 10 min.

Table 1. Measurement details of sociodemographics, personal health literacy, school health literacy environments and health outcomes.

2.3 Statistical analysis

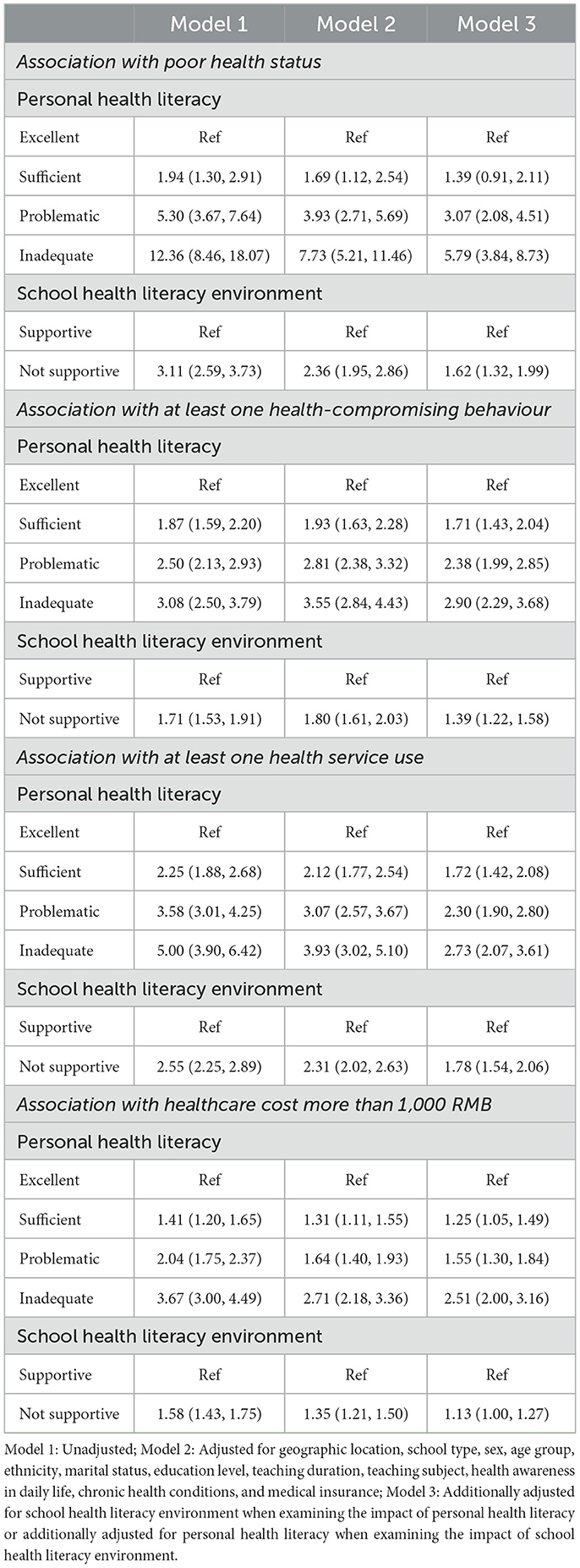

All statistical analyses were performed using Stata 18.0 (StataCorp, Texas, USA). Descriptive statistics were conducted to show the distribution of participants' characteristics, personal health literacy, school health literacy environments, and each health outcome. Univariate analysis was used to examine the relationship between participants' characteristics and levels of personal health literacy/school health literacy environments. Next, a series of logistic regression analyses were conducted to examine the associations between personal health literacy/school health literacy environments and each health outcome. Model 1 was unadjusted. Model 2 was adjusted for all covariates (i.e., geographic location, school type, sex, age group, ethnicity, marital status, highest educational level, teaching duration, teaching subject, chronic health conditions, health awareness in daily life, and medical insurance). Model 3 was additionally adjusted for school health literacy environments/personal health literacy when examining the association between personal health literacy/school health literacy environments and each health outcome.

2.4 Missing data

The proportion of respondents with complete data across all study variables was 89.9% (see Appendix 1 for details). To examine the potential impact of missing data, we used multiple imputation by chained equations to reduce the potential bias due to incomplete records (24). The imputation model included all study variables. Based on the percentage of missing data, we produced 10 imputed datasets and used Rubin's rules to obtain the final imputed estimates of the parameters of interest. Results using multiply imputed data were reported for all association analyses in the main text.

2.5 Sensitivity analyses

We also conducted sensitivity analyses to cheque the robustness of our findings using each indicator of health-compromising behaviours (cigarette smoking, alcohol drinking, and physical inactivity) and health service use (emergency service use, general practitioner service use, hospitalisation, and patient-provider communication).

3 Results

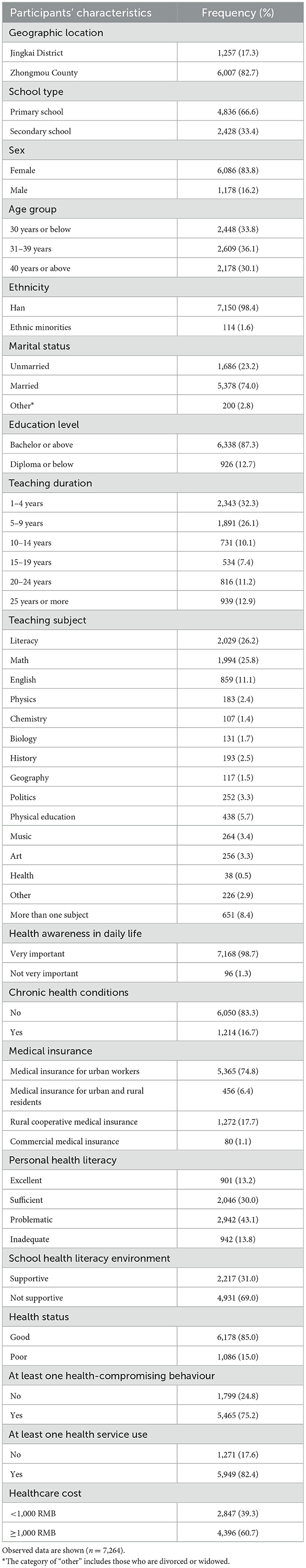

3.1 Participants' sociodemographics

In total, 7,264 teaching staff completed the survey, with a response rate of 93.9% (7,264/7,738). The average age of participants was 35.7 ± 8.3 years (age range: 18–68). Most participants were female (83.8%), from Han ethnicity (98.4%), and from married families (74.0%). The top three subjects of teaching were literacy (26.2%), math (25.8%) and English (11.1%) (see Table 2).

Table 2. Summary of participants' characteristics and distribution of health literacy and health outcomes.

3.2 Distribution of health literacy and health outcomes

Overall, schoolteachers had an average score of 75.17 ± 25.97 for personal health literacy and scored school health literacy environments with 25.30 ± 6.35. We found 43.1% and 13.8% of teachers had problematic and inadequate health literacy, respectively (see Table 2). Only one third (31.0%) of schoolteachers perceived their schools had supportive health literacy environments. 15.0% of schoolteachers had poor health status, 75.2% had at least one health-compromising behaviour, 82.4% had at least one health service use, and 60.7% spent 1,000 RMB or more for the out-of-pocket health expenditure.

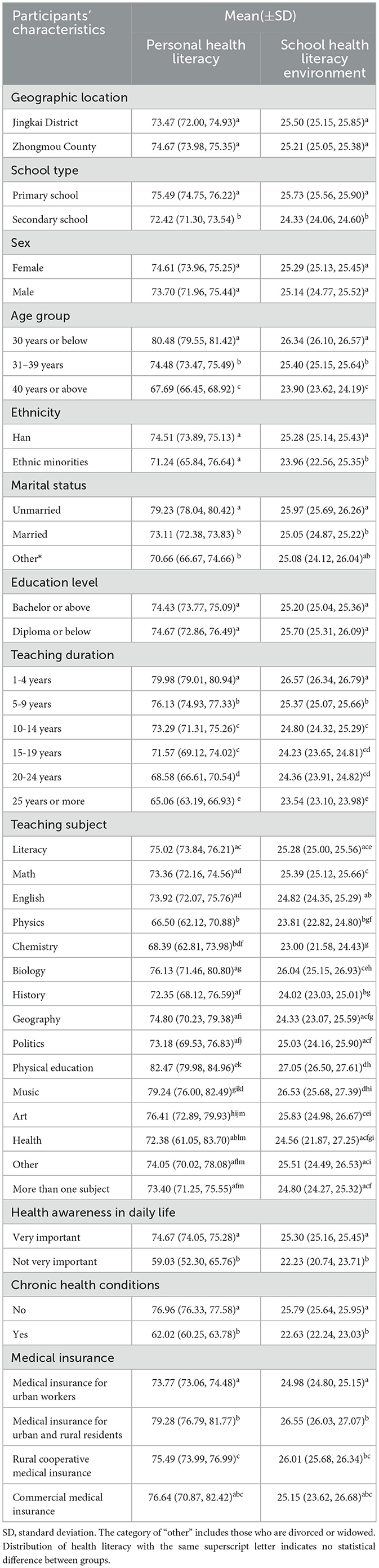

3.3 Distribution of health literacy by participants' characteristics

Table 3 shows the distribution of personal health literacy and school health literacy environments by participants' characteristics. Schoolteachers had high personal health literacy scores if they were from primary schools, female, younger, unmarried, taught physical education, had high health awareness in daily life, had no chronic health conditions, and had medical insurance for urban and rural residents. Similarly, schoolteachers perceived high levels of school health literacy environments if they were from primary schools, younger, from Han ethnicity backgrounds, unmarried, taught physical education, had high health awareness in daily life, had no chronic health conditions, and had medical insurance for urban and rural residents.

Table 3. Distribution of health literacy by participants' characteristics, using imputed samples (n = 7,264).

3.4 Associations between health literacy with health outcomes

Compared with those who had excellent health literacy, schoolteachers with inadequate health literacy had higher odds of poor health status [odds ratio (OR) = 5.79, 95% CI = 3.84, 8.73], at least one health-compromising behaviour (OR = 2.90, 95% CI = 2.29, 3.68), at least one health service use (OR = 2.73, 95% CI = 2.07, 3.61), and more healthcare cost (OR = 2.51, 95% CI = 2.00, 3.16), after adjusting for all covariates and school health literacy environments (see Table 4). Similarly, schoolteachers who perceived their school had low levels of school health literacy environments had higher odds of poor health status (OR = 1.62, 95% CI = 1.32, 1.99), at least one health-compromising behaviour (OR = 1.39, 95% CI = 1.22, 1.58), at least one health service use (OR = 1.78, 95% CI = 1.54, 2.06), and more healthcare cost (OR = 1.13, 95% CI = 1.00, 1.27), after adjusting for all covariates and personal health literacy.

Table 4. Associations between health literacy and health outcomes, using imputed samples (n = 7,264).

We also found similar results when examining the associations of personal health literacy and school health literacy environments with each indicator of health-compromising behaviours (see Appendix 2) and health service use (see Appendix 3).

4 Discussion

4.1 Main findings of this study

Using a cross-sectional study design, we examined the relationships between personal health literacy, school health literacy environments, and a range of health outcomes among Chinese schoolteachers. This was the first study in Asia to assess organisational health literacy in school settings. Specifically, we had three main findings: (i) there was a high proportion (56.9%) of schoolteachers with inadequate or problematic health literacy; (ii) there were clear sociodemographic differences (e.g., age, marital status, school type) in schoolteacher's personal health literacy and school health literacy environments; (iii) Both personal health literacy and school health literacy environments were associated with health status, health-compromising behaviours, health service use, and healthcare cost.

Consistent with findings from previous research (20, 22), we found that low health literacy was prevalent (56.9%) in our sample when using the HLS19-Q12. The 2012 Chinese national health literacy survey found that 81.5% of Chinese schoolteachers had low health literacy (23). Internationally, Yilmazel and Cetinkaya (20) used the 6-item Newest Vital Sign to measure 500 primary and secondary schoolteachers' health literacy in Turkey and found that 73.8% of teachers had low health literacy. Denuwara and Gunawardena (22) found that 32.5% of secondary teachers had low health literacy in Sri Lanka when using the 47-item European Health Literacy Survey Questionnaire, whereas Rahimi and Elahe (25) found 48.3%−60% of primary teachers had low health literacy in Iran when using the 36-item Test of Functional Health Literacy in Adults. While these studies use different instruments to measure health literacy, there is consistent evidence on the high prevalence of low health literacy among schoolteachers, indicating the pressing need to improve their health literacy.

We found that schoolteachers' health literacy levels varied by school type, age group, marital status, teaching duration, teaching subject, health awareness in daily life, chronic health condition status, and medical insurance type. Most of these findings align with previous similar studies (20, 22), showing that schoolteachers tended to have low levels of health literacy if they were older, had longer teaching duration, and had chronic health conditions. This highlights that future intervention studies should consider these characteristics when targeting schoolteachers' health literacy. However, we did not find differences in health literacy by geographic location, sex, and highest educational level, which was contrary to previous research (20, 21). One possible reason could be the convenience sampling approach, in which we recruited schoolteachers from two districts in one city, thus contributing to the homogeneity of our samples (e.g., 87.3% had a Bachelor's degree or above). Future research is needed to use more representative samples to investigate these influencing factors of schoolteachers' health literacy.

Compared to previous studies that examined influencing factors of schoolteachers' health literacy (20–22, 25), we added evidence on the association between personal health literacy and health outcomes. We found teachers with lower health literacy were likely to have poorer health status, more health-compromising behaviours, more health service use, and more healthcare costs. These findings are consistent with previous systematic reviews (2, 26) and other population-based studies (27, 28). The potential pathways linking personal health literacy with health outcomes include both personal factors (e.g., self-efficacy, health knowledge) and system factors (e.g., social support, provider competence) (29). Our findings suggest promoting schoolteachers' health literacy skills has the potential to improve their health outcomes. As shown in the recent evidence base (30, 31), health literacy interventions can lead to improved health outcomes in the general population. Future experimental research is needed among schoolteachers to evaluate the effectiveness of tailored health literacy interventions to improve their health and wellbeing.

The present study also extends the current literature by examining the school health literacy environment. In keeping with the distribution of personal health literacy, we found a similar pattern of school health literacy environments. Teachers perceived lower levels of school health literacy environments if they were older, from ethnic minority backgrounds, married, had longer teaching duration, taught subjects other than physical education and biology, had low health awareness, had chronic health conditions, and had medical insurance for urban workers. We also found lower levels of school health literacy environments were associated with poor health status, more health-compromising behaviours, more health service use, and more healthcare costs among teachers. Aligning with previous HPS research (16, 17), we found that school health literacy environments were an important situational factor in influencing schoolteachers' health and wellbeing, with potential direct and indirect pathways through personal health literacy (5), social support (16), and mental health (32).

4.2 Limitations of this study

There were several limitations that should be noted. First, we used convenience sampling to recruit schoolteachers from two districts of Zhengzhou, Henan Province. Our findings may not generalise to other geographic regions or populations. Future research is needed to recruit more representative samples to replicate our findings. Second, measurement errors may exist for self-report instruments. In the present study, we used previously validated items or instruments to enhance the validity and reliability of key measures, thus minimising the self-report bias. It would be interesting in future research to use objective instruments (e.g., Newest Vital Sign) to measure health literacy and compare whether results are consistent between objective and subjective instruments. Finally, our findings are based on the cross-sectional study design, therefore we could not establish causality. Further research using longitudinal or experimental designs is needed to confirm our findings.

4.3 Implications for future research and practise

Findings from the present study shed light on the critical relationships between personal health literacy, school health literacy environments, and health outcomes among Chinese schoolteachers. Future research may consider using similar approaches to examining the role of personal health literacy and health literacy environments in other populations (e.g., children, older adults, patients) or settings (e.g., workplaces, hospitals, communities). It would be also worthwhile to explore whether personal health literacy interacts with health literacy environments to contribute to health outcomes in future.

We found that more than half of schoolteachers had inadequate or problematic health literacy. It is imperative for governments and schools to design and implement interventions to improve schoolteachers' health literacy. To improve health outcomes for schoolteachers, both educational programs and organisational change are needed to improve personal health literacy and school environments. Findings from a recent systematic review show that educational and motivational health literacy interventions with different strategies (e.g., websites, leaflets, smartphone apps) are effective to improve health outcomes (33). Recently, there has been increasing attention to school-based programs that aim to promote schoolteachers' health literacy and improve their health outcomes. The HeLit-Schools (14) and HealthLit4Kids (34) are two successful programs that highlight the need for organisational change to create supportive environments that foster health literacy. For example, the HeLit-Schools (14) program encourages schools to become health literate, not just by delivering health education to students, but by aligning school structures, communication, and leadership with health literacy goals. This includes, but not limited to, integrating health literacy into school planning documents and policies, providing professional development to enhance schoolteachers' health literacy, and empowering students through participatory activities. Only through a whole-of-school approach can a supportive environment be created that improves the wellbeing of both schoolteachers and children.

5 Conclusion

This study examined the relationship between health literacy and schoolteachers' health outcomes from two aspects: personal health literacy and school health literacy environments. Our findings highlight that both personal health literacy and school health literacy environments are important to schoolteachers' health outcomes. Promoting health literacy at both individual and organisational levels has the potential to improve population health and reduce health disparities.

Data availability statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

Ethics statement

The studies involving humans were approved by the Institutional Review Board of Fuwai Central China Cardiovascular Hospital. The studies were conducted in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. The participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study.

Author contributions

MY: Project administration, Data curation, Writing – original draft, Conceptualization, Methodology, Writing – review & editing. RL: Writing – original draft, Project administration, Methodology, Resources, Investigation, Writing – review & editing, Conceptualization, Funding acquisition. QZ: Conceptualization, Methodology, Writing – review & editing. JW: Conceptualization, Methodology, Writing – review & editing. YB: Conceptualization, Investigation, Methodology, Writing – review & editing. XY: Conceptualization, Investigation, Methodology, Writing – review & editing. SL: Conceptualization, Investigation, Methodology, Writing – review & editing. OO: Conceptualization, Methodology, Writing – review & editing. BH: Conceptualization, Methodology, Writing – review & editing. ND: Conceptualization, Methodology, Writing – review & editing. SX: Conceptualization, Methodology, Writing – review & editing. SG: Conceptualization, Formal analysis, Methodology, Supervision, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declare that financial support was received for the research and/or publication of this article. This work was supported by the Henan Province Medical Science and Technology Research Program Joint Construction Project [grant number SBGJ202302033]; the Henan Provincial Academy of Medical Sciences Young Medical Experts Project [grant number QNYJ2023006]; the Henan Province Medical Science and Technology Joint Construction Project [grant number LHGJ20240162]; and the Henan Province Medical Science and Technology Research Program Soft Science Project [grant number RKX202201002].

Acknowledgments

We thank all the schools and teachers who participated in the study. The HLS19 Instrument used in this research was developed within “HLS19—the International Health Literacy Population Survey 2019–2021” of Measuring Population and Organisational Health Literacy (M-POHL). We also thank the HLS19 Consortium who provided authorisation for the research use of the HLS19-Q12 instrument.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The author(s) declare that no Gen AI was used in the creation of this manuscript.

Publisher's note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Supplementary material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fpubh.2025.1570615/full#supplementary-material

References

1. Nutbeam D, Lloyd JE. Understanding and responding to health literacy as a social determinant of health. Annu Rev Public Health. (2021) 42:159–73. doi: 10.1146/annurev-publhealth-090419-102529

2. Berkman ND, Sheridan SL, Donahue KE, Halpern DJ, Crotty K. Low health literacy and health outcomes: an updated systematic review. Ann Intern Med. (2011) 155:97–107. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-155-2-201107190-00005

3. World Health Organisation. Shanghai Declaration on Promoting Health in the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development. Geneva, Switzerland: WHO (2016).

4. Rowlands G, Russell S, O'Donnell A, Kaner E, Trezona A, Rademakers J, et al. What is the evidence on existing policies and linked activities and their effectiveness for improving health literacy at national, regional and organizational levels in the WHO European region?. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization. Regional Office for Europe (2018).

5. Sørensen K, Van den Broucke S, Fullam J, Doyle G, Pelikan J, Slonska Z, et al. Health literacy and public health: a systematic review and integration of definitions and models. BMC Public Health. (2012) 12:80. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-12-80

6. Nutbeam D. Health literacy as a public health goal: a challenge for contemporary health education and communication strategies into the 21st century. Health Promot Int. (2000) 15:259–67. doi: 10.1093/heapro/15.3.259

7. Australian Commission on Safety and Quality in Health Care. National Statement on Health Literacy. Taking Action to Improve Safety and Quality. Sydney, NSW: Australian Commission on Safety and Quality in Health Care (2014).

8. Tavousi M, Mohammadi S, Sadighi J, Zarei F, Kermani RM, Rostami R, et al. Measuring health literacy: a systematic review and bibliometric analysis of instruments from 1993 to 2021. PLoS ONE. (2022) 17:e0271524. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0271524

9. Pelikan JM, Link T, Straßmayr C, Waldherr K, Alfers T, Bøggild H, et al. Measuring comprehensive, general health literacy in the general adult population: the development and validation of the HLS(19)-Q12 instrument in seventeen countries. Int J Environ Res Public Health. (2022) 19:14129. doi: 10.3390/ijerph192114129

10. Rajah R, Hassali MAA, Murugiah MK, A. systematic review of the prevalence of limited health literacy in Southeast Asian countries. Public Health. (2019) 167:8–15. doi: 10.1016/j.puhe.2018.09.028

11. Mei X, Chen G, Zuo Y, Wu Q, Li J, Li Y. Changes in the health literacy of residents aged 15-69 years in central China: a three-round cross-sectional study. Front Public Health. (2023) 11:1092892. doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2023.1092892

12. Okan O, Paakkari L, Dadaczynski K. Health Literacy in Schools. State of the art Haderslev, Denmark: Schools for Health in Europe Network Foundation (2020).

13. Peterson FL, Cooper RJ, Laird JA. Enhancing teacher health literacy in school health promotion a vision for the new millennium. J School Health. (2001) 71:138–44. doi: 10.1111/j.1746-1561.2001.tb01311.x

14. Kirchhoff S, Dadaczynski K, Pelikan JM, Zelinka-Roitner I, Dietscher C, Bittlingmayer UH, et al. Organizational health literacy in schools: concept development for health-literate schools. Int J Environ Res Public Health. (2022) 19:8795. doi: 10.3390/ijerph19148795

15. St Leger L. Schools, health literacy and public health: possibilities and challenges. Health Promot Int. (2001) 16:197–205. doi: 10.1093/heapro/16.2.197

16. Bae EJ, Yoon JY. Health literacy as a major contributor to health-promoting behaviors among Korean teachers. Int J Environ Res Public Health. (2021) 18:3304. doi: 10.3390/ijerph18063304

17. Lee A. Health-promoting schools. Appl Health Econ Health Policy. (2009) 7:11–7. doi: 10.1007/BF03256138

18. Otten C, Nash R, Patterson K. HealthLit4Kids: teacher experiences of health literacy professional development in an Australian primary school setting. Health Promot Int. (2023) 38:daac053. doi: 10.1093/heapro/daac053

19. Shangguan L, Chen S, Cao L. Research on the current situation, causes, and countermeasures of primary school physical education teachers' health literacy. J Healthcare Eng. (2022) 29:7851028. doi: 10.1155/2022/7851028

20. Yilmazel G, Çetinkaya F. Health literacy among schoolteachers in Çorum, Turkey. EMHJ-East Mediterr Health J. (2015) 21:598–605. doi: 10.26719/2015.21.8.598

21. Ahmadi F, Montazeri A. Health literacy of pre-service teachers from Farhangian University: a cross-sectional survey. Int J School Health. (2019) 6:1–5. doi: 10.5812/intjsh.82028

22. Denuwara H, Gunawardena NS. Level of health literacy and factors associated with it among school teachers in an education zone in Colombo, Sri Lanka. BMC Public Health. (2017) 17:631. doi: 10.1186/s12889-017-4543-x

23. Li L, Li Y, Nie X, Huang X, Shi M. Analysis on the status of teachers' health literacy in Chinese residents' health literacy monitoring in 2012. Chin J Health Educ. (2015) (2):141–6.

24. White IR, Royston P, Wood AM. Multiple imputation using chained equations: issues and guidance for practice. Stat Med. (2011) 30:377–99. doi: 10.1002/sim.4067

25. Rahimi B, Tavassoli E. Measuring health literacy of elementary school teachers in Shahrekord. J Health Liter. (2019) 4:25–32. doi: 10.22038/jhl.2019.38770.1039

26. Fleary SA, Joseph P, Pappagianopoulos JE. Adolescent health literacy and health behaviors: a systematic review. J Adolesc. (2018) 62:116–27. doi: 10.1016/j.adolescence.2017.11.010

27. Li L, Li Y, Nie X, Wang L, Zhang G. The association between health literacy and medical out-of-pocket expenses among residents in China. J Public Health. (2023) 32:1–9. doi: 10.1007/s10389-022-01792-2

28. Svendsen MT, Bak CK, Sørensen K, Pelikan J, Riddersholm SJ, Skals RK, et al. Associations of health literacy with socioeconomic position, health risk behavior, and health status: a large national population-based survey among Danish adults. BMC Public Health. (2020) 20:1–12. doi: 10.1186/s12889-020-08498-8

29. Paasche-Orlow MK, Wolf MS. The causal pathways linking health literacy to health outcomes. Am J Health Behav. (2007) 31:S19–26. doi: 10.5993/AJHB.31.s1.4

30. Walters R, Leslie SJ, Polson R, Cusack T, Gorely T. Establishing the efficacy of interventions to improve health literacy and health behaviours: a systematic review. BMC Public Health. (2020) 20:1–17. doi: 10.1186/s12889-020-08991-0

31. Meherali S, Punjani NS, Mevawala A. Health literacy interventions to improve health outcomes in low- and middle-income countries. Health Liter Res Pract. (2020) 4:e251–e66. doi: 10.3928/24748307-20201118-01

32. Spratt J, Shucksmith J, Philip K, Watson C. ‘Part of who we are as a school should include responsibility for wellbeing': links between the school environment, mental health and behaviour. Pastoral Care Educ. (2006) 24:14–21. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-0122.2006.00374.x

33. Rosário J, Raposo B, Santos E, Dias S, Pedro AR. Efficacy of health literacy interventions aimed to improve health gains of higher education students—a systematic review. BMC Public Health. (2024) 24:882. doi: 10.1186/s12889-024-18358-4

34. Nash R, Elmer S, Thomas K, Osborne R, MacIntyre K, Shelley B, et al. HealthLit4Kids study protocol; crossing boundaries for positive health literacy outcomes. BMC Public Health. (2018) 18:690. doi: 10.1186/s12889-018-5558-7

35. Liu R, Zhao Q, Yu M, Chen H, Yang X, Liu S, et al. Measuring General Health Literacy in Chinese adults: validation of the HLS19-Q12 instrument. BMC Public Health. (2024) 24:1036. doi: 10.1186/s12889-024-17977-1

36. Okan O, Kirchhoff S, Krudewig C. Organizational health literacy of schools (OHLS-Q). Questionnaire Long Form English HeLit-Schools Funded by the Federal Ministry of Health. Germany: Technical University of Munich (2022).

37. Kirchhoff S, Krudewig C, Okan O. Organizational health literacy of schools questionnaire – short form (OHLS-Q-SF). Funded by the Federal Ministry of Health, Germany: Technical University of Munich (2022).

38. Guo S, O'Connor M, Mensah F, Olsson CA, Goldfeld S, Lacey RE, et al. Measuring Positive Childhood Experiences: Testing the structural and predictive validity of the Health Outcomes from Positive Experiences (HOPE) framework. Acad Pediatr. (2022) 22:942–51. doi: 10.1016/j.acap.2021.11.003

39. Haddock CK, Poston WS, Pyle SA, Klesges RC, Vander Weg MW, Peterson A, et al. The validity of self-rated health as a measure of health status among young military personnel: evidence from a cross-sectional survey. Health Qual Life Outcomes. (2006) 4:57. doi: 10.1186/1477-7525-4-57

Keywords: personal health literacy, organisational health literacy, health outcomes, teachers, HLS19-Q12

Citation: Yu M, Liu R, Zhao Q, Wang J, Bai Y, Yang X, Liu S, Okan O, Hua B, Dai N, Xu S and Guo S (2025) The impact of personal health literacy and school health literacy environments on schoolteachers' health outcomes. Front. Public Health 13:1570615. doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2025.1570615

Received: 04 February 2025; Accepted: 25 April 2025;

Published: 15 May 2025.

Edited by:

Svein Barene, Inland Norway University of Applied Sciences, NorwayReviewed by:

Karolina Sobczyk, Medical University of Silesia, PolandMukaddes Örs, Akdeniz University, Türkiye

Copyright © 2025 Yu, Liu, Zhao, Wang, Bai, Yang, Liu, Okan, Hua, Dai, Xu and Guo. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Shuaijun Guo, Z3NoajE5ODZAZ21haWwuY29t; Rongmei Liu, bGl1eW9uZ21laTAyMDNAMTYzLmNvbQ==

†These authors share first authorship

‡These authors have contributed equally to this work

Mingyang Yu

Mingyang Yu Rongmei Liu1*†‡

Rongmei Liu1*†‡ Qiuping Zhao

Qiuping Zhao Xiaomo Yang

Xiaomo Yang Orkan Okan

Orkan Okan Shuaijun Guo

Shuaijun Guo