- School of Public Health, Bielefeld University, Bielefeld, Germany

Introduction: Participatory health research and promotion aims to foster inclusive knowledge production and address health inequities. Migrant communities, given their diverse backgrounds and health needs, are regularly engaged in PHR/P. However, the extent and ways of their participation across research phases and the integration of critical reflections in published studies from Germany remain underexplored.

Methods: This scoping review followed Arksey and O’Malley’s framework and adhered to PRISMA guidelines. Four databases were systematically searched for eligible studies. A total of 17 publications representing 13 projects were included and analysed using a structured codebook.

Results: Migrants’ participation was described unevenly across different phases of the research process, with more frequent engagement in operational aspects such as data collection than in research design, analysis, or dissemination. Reflexivity was inconsistently reported. While some studies provided theoretical reflections on participation, explicit links to how these reflections shaped to research practices were often missing. Reflections also focused more on methodological and external challenges than on power dynamics, ethics, or researcher positionality.

Discussion: Since our analysis is based on published accounts, the extent to which participation and reflexivity were practiced beyond what was documented remains unclear. More systematic documentation of participatory processes and reflexivity would enhance transparency, reflect the complexities of PHR/P with migrants more deeply, and inform future practice.

Introduction

In Germany, nearly a quarter of the total population has a migration background Statistisches (1). This includes first- and second-generation migrants from different regions of the world, with varying legal statuses, socio-economic conditions, and linguistic diversity as well as diverse health perceptions, risk factors, and access to healthcare (2, 3); Statistisches (1, 4). Thus, Germany is characterized by a highly diverse and continuously growing migrant population and one of the main countries of immigration in Europe.

Because understandings of the relationship between migration experiences and health remain inadequate and fragmented, migrants have become a focal point for participatory health research globally, including Germany (5–8). Participatory approaches foster collaboration among academic researchers and affected communities and thereby aim for a deeper understanding of sociocultural contexts relevant for health, bridging the gap between academic knowledge and everyday realities and promoting health equity (9, 10). Although becoming increasingly common in health promotion and health research, the versatility of participatory approaches comes with their own challenges (11, 12). These include debates on classifications and rigor (13) as well as tensions between ideals of co-creation and realities shaped by representation, resources, group and power dynamics (6, 14). These challenging dynamics are particularly pronounced in research with migrant communities, where structural inequalities, socio-economic exclusion, legal uncertainties, and other barriers (such as language, cultural norms, and competing priorities) can intersect with participatory processes in ways that shape both the extent and nature of involvement (6, 7, 15, 16).

While Germany’s participatory health research landscape is expanding [(see 17)], there is no comprehensive overview of how migrant communities are engaged in participatory health approaches – especially who participates, during which phases of the research process, and how reflections on participation are reported. To address this gap, our scoping review systematically identifies and synthesises published research on participatory approaches with migrant communities in Germany.

Conceptual framework of participatory approaches in health

There is a wide spectrum of participatory approaches with diverse, sometimes overlapping terminology (6, 8, 18). In this article, we focus on two forms of participatory approaches related to health: participatory health research (PHR) and participatory health promotion (PHP) that can be distinguished by their core objectives. PHR is designed to generate knowledge through systematic inquiry in close collaboration with the communities involved with the research process itself, often serving as a means of empowerment and social change (18). By contrast, PHP aims to improve health outcomes by co-creating, implementing, and evaluating interventions with communities, with research often a secondary rather than primary aim (19, 20). Given the broad terminology in participatory health approaches, we use the term participatory health research/promotion (PHR/P) to encompass both forms (21), acknowledging their shared emphasis on collaboration while recognizing their distinct orientations toward knowledge production or practical intervention.

PHR/P is rooted in the principles of collaboration, shared ownership, and the redistribution of power in research processes (22, 23). It challenges conventional research paradigms by emphasizing equity between academic and community partners, valuing experiential knowledge alongside scientific expertise (18, 21). It bridges research and practice, aiming to ensure that interventions reflect lived realities, while also empowering participants and strengthening local capacities (6, 24)

Working within an open and holistic paradigm, PHR/P embraces methodological diversity, allowing research approaches to be tailored to the specific needs and contexts of participating communities (21). The inherent flexibility of PHR/P is its hallmark, enabling it to adapt to diverse settings and participants’ needs. However, this adaptability also introduces challenges in defining how participation is structured and whose voices are represented (12, 24, 25). Moreover, with the increasing adoption of PHR/P, concerns have emerged regarding tokenistic and ritualistic participation, where involvement is superficial rather than substantive (6). While there is a range of existing frameworks to guide PHR/P, there is limited systematic analysis of how the principles of PHR/P translate into practice, particularly in Germany, where a large and diverse migrant population intersects with a federal health system, complex access pathways, and policy frameworks that differ from those of other countries (26).

Given Germany’s particular context as a major European country of immigration, this review examines how participation in PHR/P with migrant communities in Germany is described in publications. It addresses the overarching research question:

How are participatory health research and promotion (PHR/P) with migrant communities in Germany described in the scientific literature?

To address this question, we examine four sub-dimensions:

a. Stated health- and participatory-related objectives in PHR/P with migrant communities

PHR/P often combines health-related aims, such as improving health literacy, behavioral change, or access to services (25, 27), with participatory aims, including capacity building, empowerment, and challenging hierarchies in knowledge production (6, 21). While these objectives are interrelated, we explore how they are framed in the literature, and to what extent health impact or participatory processes are emphasized.

b. Described participants in PHR/P with migrant communities

PHR/P emphasizes collaborations and partnerships, with participant composition varying widely depending on the context and project (9, 28). Collaborations may involve academic researchers, non-academically trained co-researchers (hereafter referred to as “co-researchers”), such as migrants or representatives from participating communities, and other stakeholders like NGOs, healthcare providers, or policymakers (9, 18, 29). We examine how participant groups are described, whose voices are represented and whose are not, and how inclusion or exclusion is addressed in German studies.

c. Participation in research phases in PHR/P with migrant communities

PHR/P aspires to enable the most comprehensive participation from those individuals directly involved or impacted by the study (18). Ideally, co-researchers engage across all phases, from defining questions to sharing results. A range of scales or typologies [for an overview (see 30)] have been developed to guide those conducting PHR/P, yet authors acknowledge that this level of participation is not always possible, taking into account factors such as distinct resource availability (e.g., time, financial means, research experience, legal uncertainties), administrative frameworks and what can and cannot be imposed on co-researchers such as migrants. The International Collaboration for Participatory Health Research (31) hence calls for optimum participation and using the potential of participation where and whenever possible. We examine how German studies describe participation in different research phases, and how participation is adapted to resources, contexts, and constraints.

d. Project-related reflections in PHR/P with migrant communities

Reflexivity is central to PHR/P, encouraging researchers to critically examine power dynamics, roles, and relationships within the research process (6, 18, 32, 33). Reflexivity fosters awareness of social positions, resource allocation, and methodological choices, which often become spaces where power is negotiated and redefined (32, 34). In the context of PHR/P with migrant communities, reflexivity takes on additional significance due to structural inequalities, legal uncertainties, and the precarious access to healthcare and research participation that many migrants face. We explore how studies reflect on these dynamics when working with migrant communities.

Methodology

This scoping review was conducted following the methodological framework by Arksey and O’Malley (35). The reporting adheres to the PRISMA guidelines (36).

Databases searches and search strategy

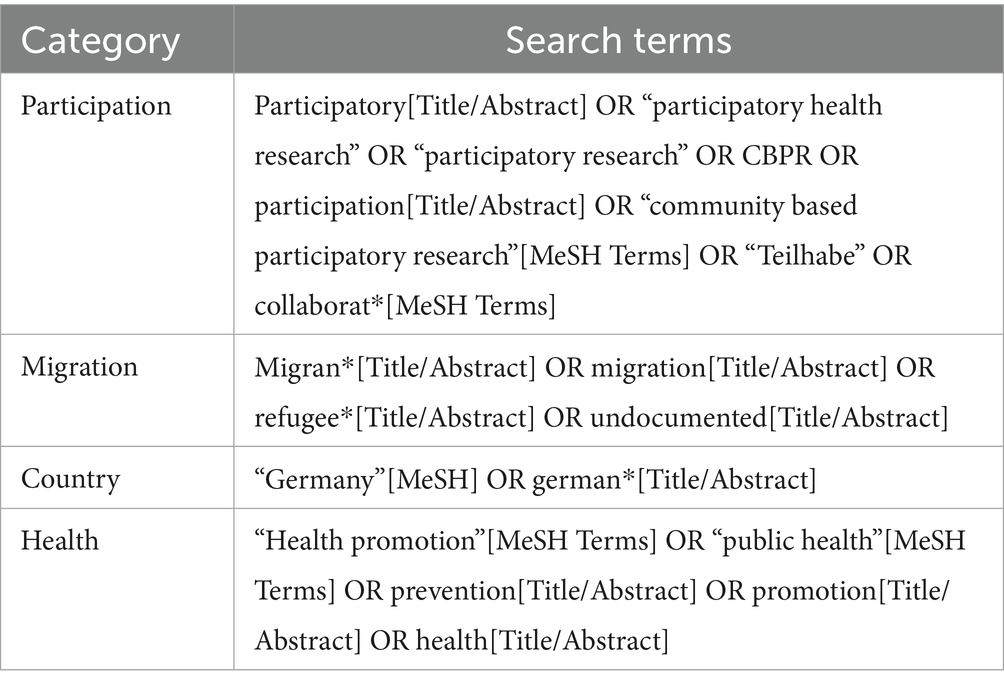

We searched for peer-reviewed and non-peer-reviewed (e.g., book chapters) literature with a Digital Object Identifier (DOI) published in English or German in four databases (Web of Science, PubMed, Psyndex, LIVIVO). We limited our search to literature published since 2000, as this period marks the increasing formalization of quality criteria in health promotion and the growing institutional recognition of participation in research and policy (37). The literature search was conducted on 12 of September 2023. Four search categories guided our search string: participatory research; migrant; Germany; and health. The categories and their synonyms were linked between each by the Boolean operators and/or as shown in Table 1.

The here displayed search string used for PubMed was adapted accordingly to match the indexing and search functionalities of the other databases. Moreover, we sent an email to the mailing list of PartNet, asking the researching community for further literature we might have missed during the database search.

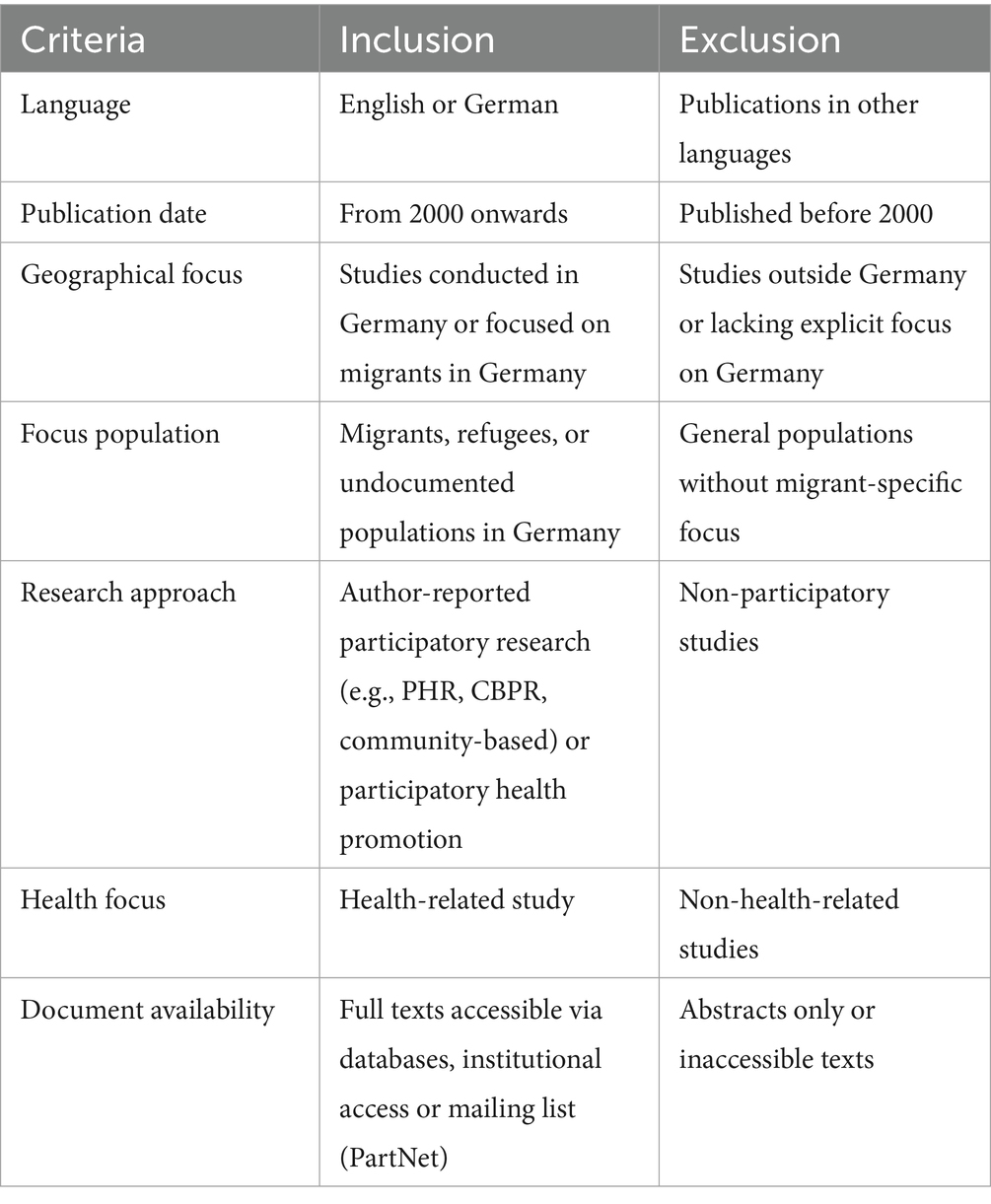

Selection of studies

Titles, abstracts and citations from all the searches were downloaded and duplicates removed manually by two reviewers. The records were screened by three reviewers (first author and two student assistants) against the inclusion and exclusion criteria (Table 2). To ensure accuracy and consistency in the coding process, records retrieved from one database (PSYNDEX, n = 68) were screened by all three reviewers; no disagreements were found. Following this, the abstracts from the remaining databases and responses from the mailing list of PartNet were screened by two reviewers each, i.e., one student assistant and the first author. Each record was marked as either “exclude,” “include” or “unsure” and disagreements were discussed between the reviewers. Similarly, publications that were considered eligible for the review were retained for a full-text review, each independently reviewed by a student assistant and the first or second author.

During the study selection process, we identified multiple publications related to the same projects. If these publications met the inclusion criteria and were deemed non-redundant—such as reporting on different aspects, methods, or outcomes of the project—they were included in the review. As a result, our final analysis included 13 distinct projects represented by 17 publications, with four projects contributing two publications each.

Data extraction and analysis

The code book for our review was operationalized using the International Collaboration for Participatory Health Research “Characteristics of Participatory Health Research” (31) (see Supplementary file for the full code book). Code categories evolved around general publication descriptions (e.g., type of article, health topic, authorship, backgrounds of authors); theoretical conceptualization and terminology of the participatory study (e.g., use of theoretical models, participation framework, terminology for non-academic researchers); methodological approach (e.g., study design; recruitment, inclusion and exclusion criteria); participation in the research process (described phases of the research process with participation described); and reflections (e.g., effects of the participation design, ethical concerns, resources and context factors, positionality of the research team). The code book included closed and open categories for quantitative and qualitative data extraction. Due to our focus on how PHR/P is conducted with migrants in Germany, we neither focused on the results relating to the health topic of the publication, nor did we do a quality assessment of the overall study and rigor of the methods. This was an intentional decision, as the included studies were highly heterogeneous and our primary aim was to analyse participatory approaches rather than study quality or intervention effects.

Based on the codebook, an Excel sheet was created to tabulate the extracted data. The coding process involved both quantitative and qualitative approaches. While our coding framework was structured around the research dimensions (deductive), for open categories and in the dimension of reflections, we explicitly employed inductive coding to allow for the emergence of new themes and insights from the material. Three student assistants and two mid-career researchers (first and second author) participated in coding. To ensure consistency, a test coding phase was conducted at the start, during which all reviewers independently coded the same publication. Discrepancies were discussed, and the codebook was refined to ensure a shared understanding by clarifying the meaning of key terms, distinguishing between categories, and adding relevant examples where needed. For the main analysis, each included full text was coded independently by two reviewers—a student assistant and either the first or second author. The coded results were compared, and discrepancies were resolved through discussion between the two reviewers. Disagreements were classified as either human errors (e.g., inattention) or more systematic issues, which are reflected upon in the discussion section.

Quantitative coding

Closed categories in the codebook were coded numerically (e.g., 1 = Yes, 2 = Unclear, 3 = Not named), allowing for systematic analysis and the calculation of inter-rater reliability. Inter-rater reliability was determined using the ReCal2 tool (38) to compute Cohen’s kappa for each coding team. Kappa values varied slightly across teams, with an overall kappa value of 0.75, indicating substantial agreement. The distinction between the coding categories was carefully defined to ensure clarity and consistency. For example, “Yes” indicated explicit mention and elaboration, “Unclear” referred to instances where it was not evident whether a particular reflection was related to the project or theoretical aspects, or when certain concepts were mentioned without further explanation or connection to the project, and “Not Named” denoted the complete absence of reference to the category.

Qualitative coding

For open categories (often following quantitative coding of “Yes” or “Other,” see codebook), text passages relevant to the codes were copied into Excel cells. In addition, all passages were highlighted and marked in the original PDF files, ensuring traceability between the extracted data and the corresponding texts. Using the extracted text data, the first author conducted a qualitative content analysis, as described by Mayring (39), employing an inductive approach to identify emerging themes. This process involved iterative coding and the creation of new categories based on the data. For RQ 4, which focused on reflections, we combined deductive and inductive coding. Predefined categories (e.g., ethical aspects) were used to structure the analysis, ensuring coverage of key reflection areas. Within these categories, inductive coding was applied to capture additional nuances and emergent themes in how reflections were framed. This approach allowed for both systematic classification and deeper qualitative interpretation of how participatory processes were documented across the reviewed publications.

For projects with two publications, the analysis was conducted at the project level to avoid duplication. If a category was coded as “Yes” across all publications, it was recorded as a single “Yes.” If the category appeared in only one publication, this was still considered sufficient for a “Yes” designation. Conversely, if the category was absent across all publications, it was coded as “No.” This approach ensured that each project contributed a single, non-redundant entry to the overall analysis. Generative AI (ChatGPT from Open AI) was used for language refinement during manuscript preparation.

Results

Identification and selection of studies

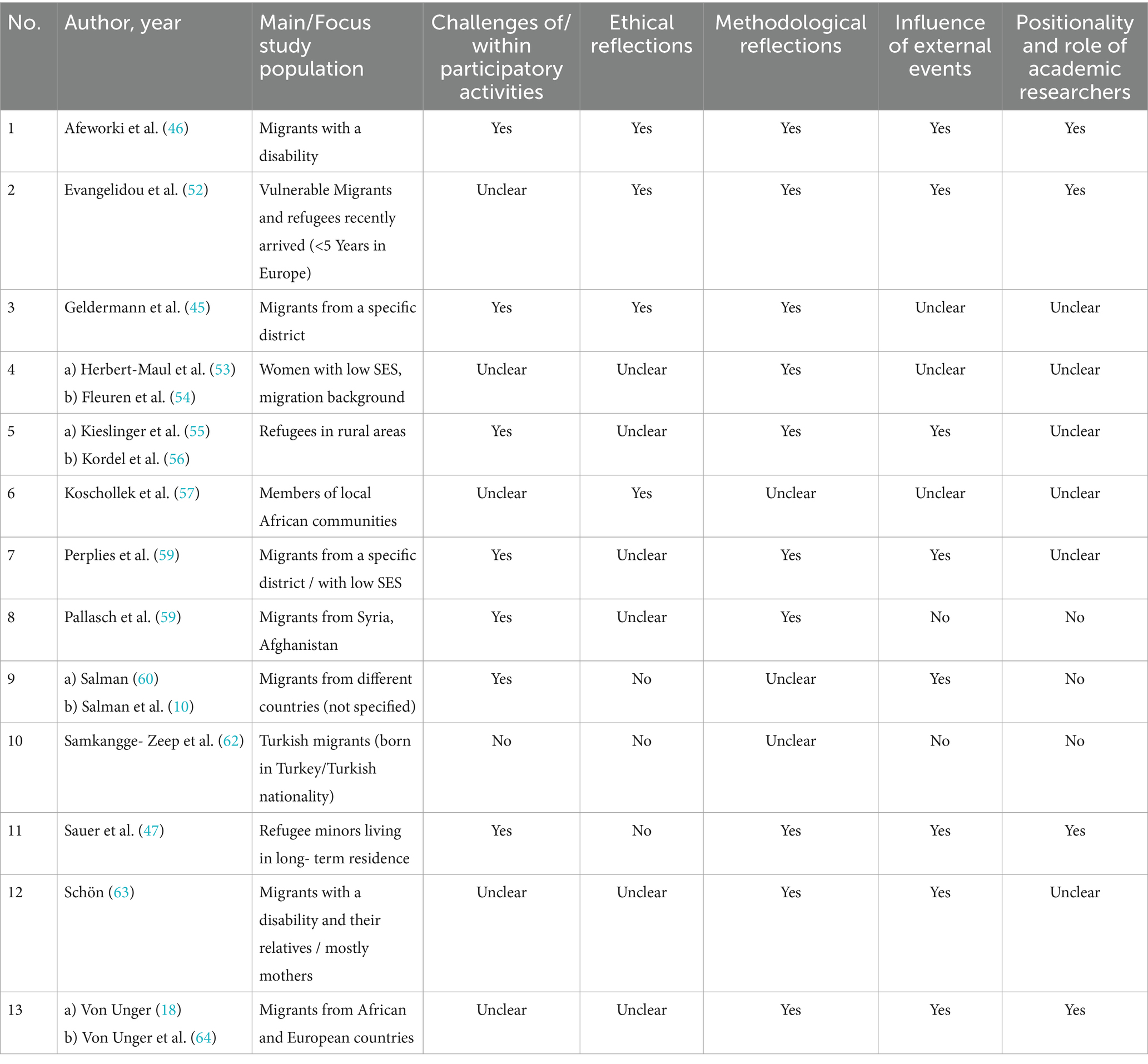

The PRISMA flow diagram (see Figure 1) summarizes the processes used to identify and select studies for inclusion in this review. The search strategy identified 1,100 records from four databases (Web of Science, LIVIVO, PubMed, and Psyndex), along with 32 additional records received after our email to the PartNet mailing list. After the removal of 52 duplicates, 1,076 records remained for screening. Title and abstract screening led to the exclusion of 1,032 records, and 44 full-text studies were obtained for further review.

Figure 1. PRISMA-based flow diagram (65) depicting literature search, screening and selection processes.

During the full-text review, 29 studies were excluded for the following reasons: no focus on migrants (n = 14), no health-related topic (n = 10), or no participatory project (n = 5). Ultimately, 13 distinct projects, represented across 17 publications, were included in the final analysis, with four projects contributing two publications each.

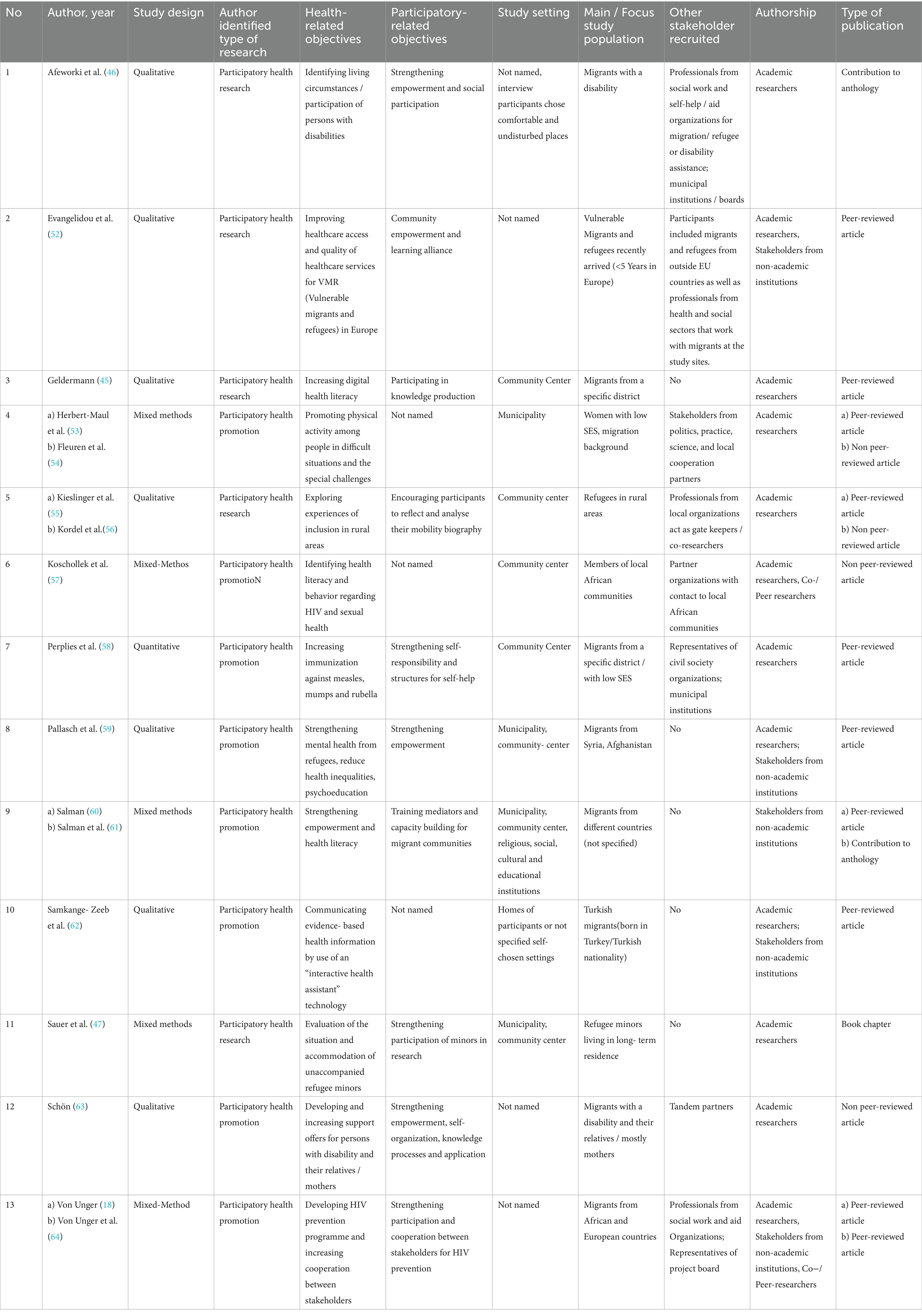

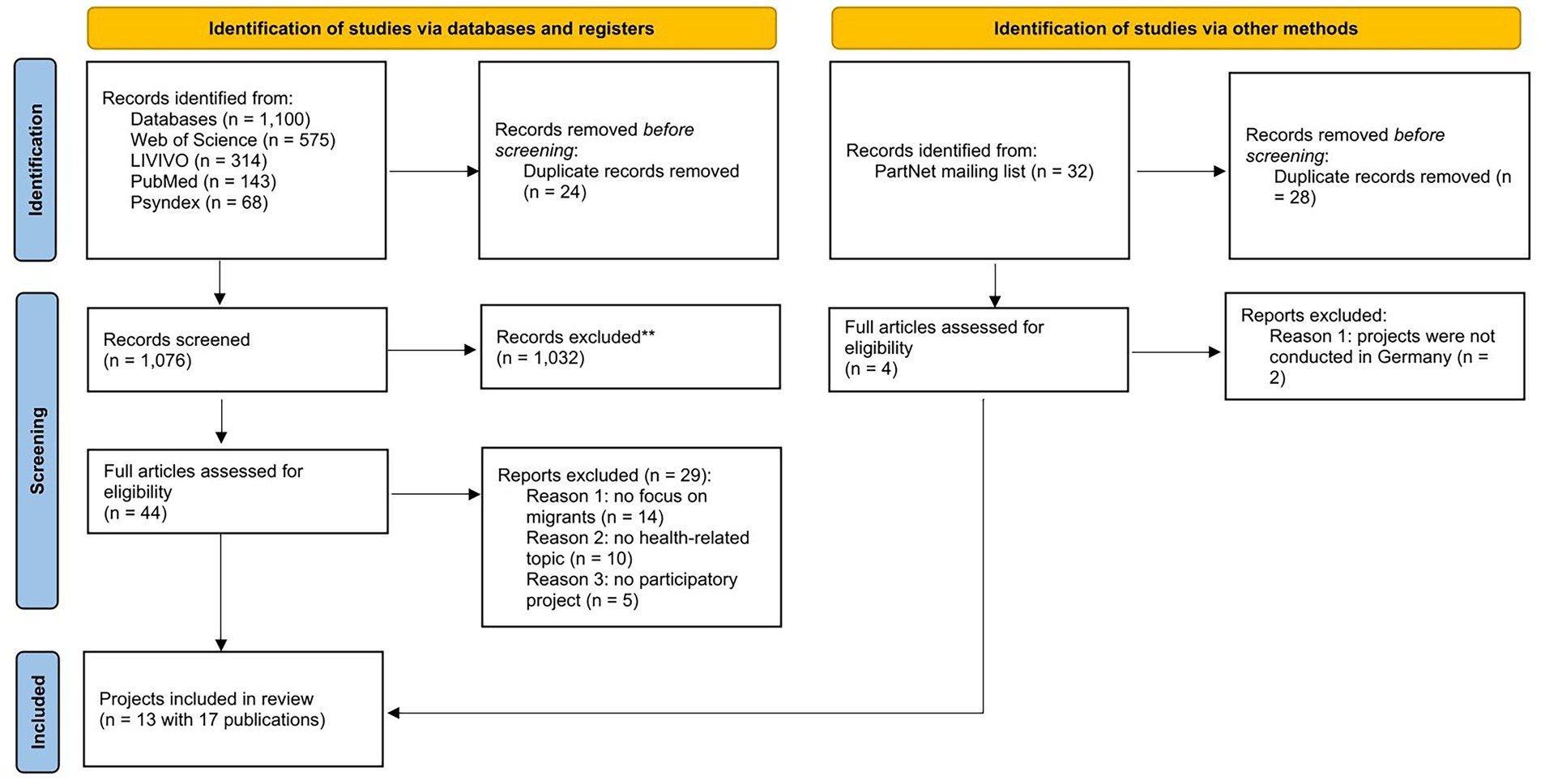

Characteristics of included projects

The characteristics of the 13 included projects are presented in Table 3, with each project numbered for reference. Around one third of the projects (n = 5) were published between 2005 and 2014, while the majority of the included projects (n = 9) were published in the last 10 years. The majority of publications (counting N = 17) published their findings in peer-reviewed journals (n = 10), three in non-peer-reviewed journals, two as anthology contributions and one as a book chapter. The methodological landscape shows a predominant preference for qualitative (n = 7) and mixed-method designs (n = 5), with only one quantitative study (No. 7) (Table 3).

a. Stated health- and participatory-related objectives in PHR/P with migrant communities

Across the 13 projects, slightly more than half were coded as PHP (n = 8), with the remainder as PHR (n = 5). Across projects, objectives (health- and participatory-related) often ran in parallel with their coding as either PHP or PHR. PHP projects commonly targeted behavior change or service uptake (e.g., vaccination uptake, No. 7), while PHR projects more often emphasized knowledge generation, capacity building, or community empowerment (e.g., community and stakeholder strengthening, No. 13). Health literacy was reported as an objective across both types (No. 3, 9, 10). An observable finding is the variability in the explicitness of participatory objectives: in three PHP projects (No. 6, 9, 10), participatory-related aims were only stated implicitly by describing community-facing activities elsewhere; this points to inconsistencies in how explicitly participatory intent is articulated at the level of reported objectives. Where health- and participatory-related objectives were reported together (e.g., No. 1, 3, 11, 12), the publications framed health improvement and participatory strengthening as mutually reinforcing (Table 3).

b. Participants described in PHR/P with migrant communities

Across studies, project teams consistently combined academic researchers with migrant co-researchers, and, variably, additional stakeholders (n = 7). Recruitment frequently added further criteria beyond “migrant,” for instance, low socioeconomic status (SES) or vulnerability (No. 2–4, 7, 11), country-of-origin (No. 8–9), disability status (No. 1, 11), or rural residence (No. 5–6). Stakeholders often functioned as gatekeepers, facilitators, or co-investigators, hence, their participation appeared purpose-built for community entry or logistics (No. 5, 7, 13) and were often included in projects working with ‘hard-to-reach-groups’, such as rural communities, low-SES groups, or migrants living with disabilities (Table 3).

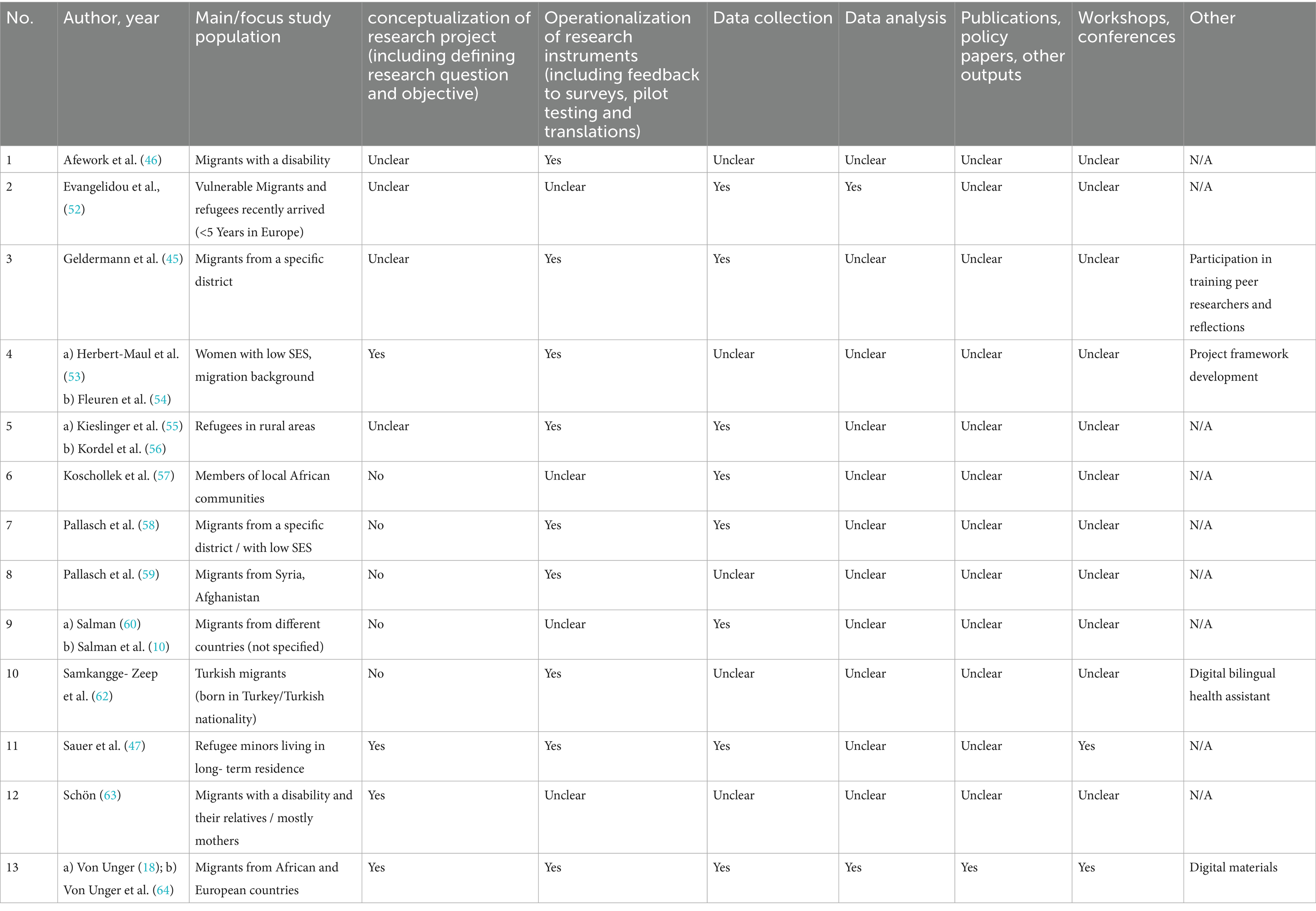

c. Participation in research phases in PHR/P with migrant communities

Reported participation varied markedly across the six phases as participation peaked during instrument development and data collection and dropped sharply for analysis and outputs. In operationalization, migrants frequently piloted or adapted tools (e.g., translations, feedback; No. 1, 3–5, 7, 8, 10–11, 13). Data collection was also commonly participatory (No. 2, 3, 5–7, 9, 11, 13). By contrast, explicit involvement in analysis (No. 2, 12) and outputs/dissemination was less frequent; where reported, outputs included trainings, frameworks, and health materials (No. 3, 4, 10, 13). A noticeable aspect is the extent of “unclear/not named” reporting in early (conceptualization: No. 1–3, 5) and late phases (outputs: most projects except No. 13). This pattern indicates that participation often peaks where tasks are operational and time-bound, while roles in interpretive and disseminative tasks were either rare or insufficiently reported. Only two projects shared authorship in the reviewed publications with co-researchers (No. 6, 13) and five projects included the authorship of stakeholders from non-academic institutions (No. 2, 8–10, 13) (Table 4).

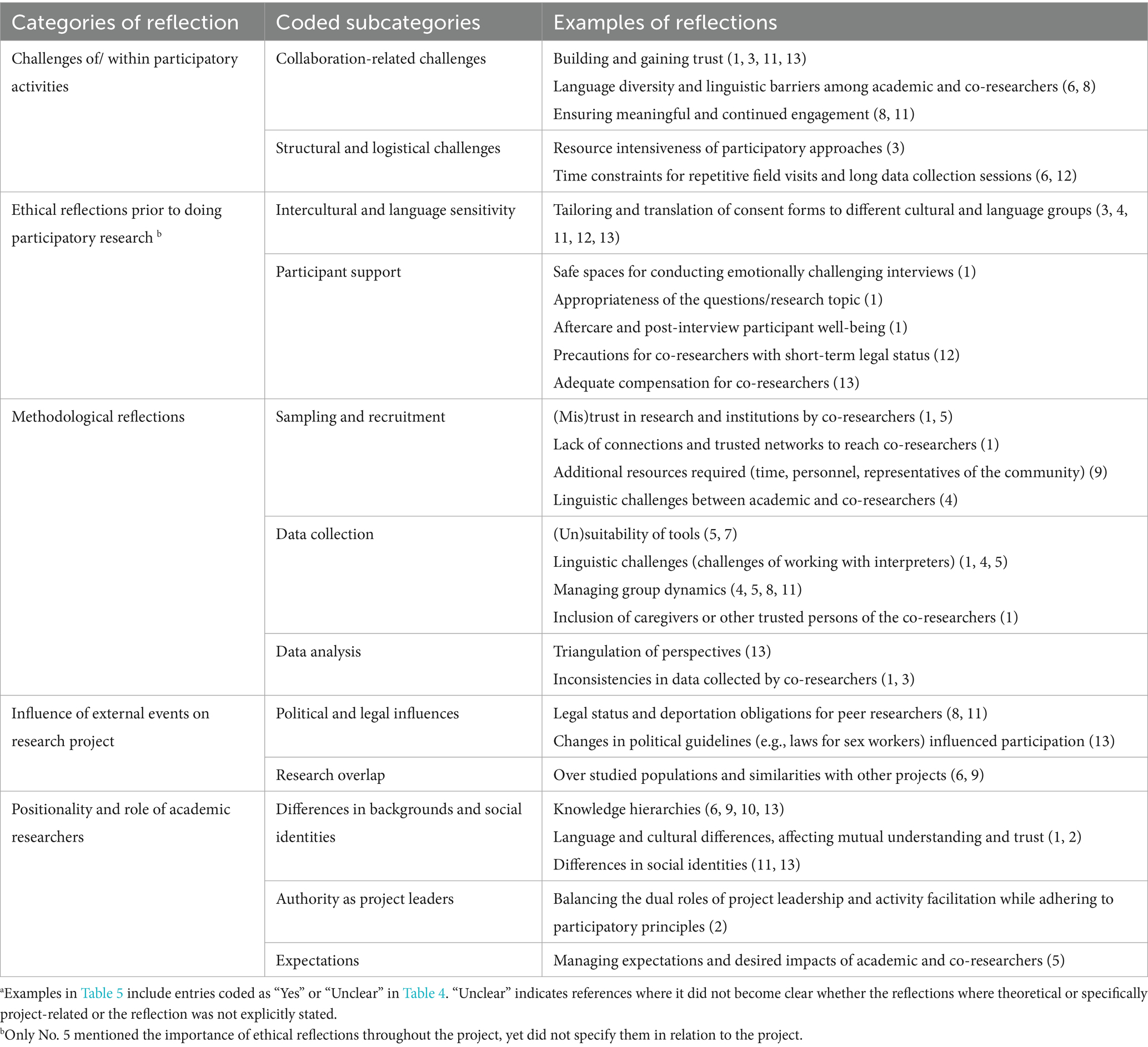

d. Described project-related reflections in PHR/P with migrants

We recorded whether reflections were explicitly reported and then inductively grouped the reported content (see Tables 5, 6). An observable finding is the concentration of reported reflections on methods (10 projects) and influence of external events (8 projects), while ethics (4 projects) and positionality (4 projects: No. 1, 2, 11, 13) appeared less often. Notably, methodological challenges in relation to different research phases were recurring topics. For example, mistrust towards research or institutions during recruitment (No. 1, 5), managing group dynamics (No. 4, 5, 8, 11) and difficulties with interpreter-mediated interviews during data collection were highlighted (No. 1, 5). Reflections on collaboration-related challenges (7 projects) were also common.

Table 6. Overview of inductively coded subcategories and their examplesa.

An observable pattern is the reference to external factors, impacting research processes, including changes in deportation laws (No. 8, 11) and sector-specific regulations (No. 13). This suggests that participatory research with migrant communities is shaped not only by internal project dynamics but also by broader political and legal environments. Reflections on collaboration and logistics, such as trust-building (No. 1, 3, 11, 13) and sustaining engagement (No. 8, 11) were also common. In contrast, considerations of positionality and power imbalances were less systematically discussed and limited to brief mentions.

Overall, the distribution of reflections indicates a focus on practical and contextual challenges, with less emphasis on ethical and positionality-related aspects, which mirrors the participation in specific research phases as described earlier (see c). While some projects were reflection-heavy (e.g., No. 1, 11), others contained little reflections (e.g., No. 4, 6, 10). Noteworthy is also the high number of codings as ‘unclear’. This coding was used when papers provided rich theoretical reflections in their introduction or theoretical framework but lacked clear connections to the actual reflexive activities within the project.

Discussion

This scoping review mapped how participatory health research and promotion (PHR/P) with migrant communities in Germany is described in the scientific literature. In the following, key patterns and recurring gaps are discussed across the four analytical dimensions (a–d).

Our review revealed that PHR/P projects with migrant communities in Germany encompassed a diverse range of health-related and participatory-related objectives (a). Especially in projects identified as PHP, the extent to which participation was an explicit objective varied and appeared to function primarily as a methodological tool rather than as a guiding principle. This aligns with debates in PHR about the risk of instrumental participation and the importance of making participatory purposes explicit (6, 21, 32).

On who participated (b), projects consistently involved academic researchers and migrant co-researchers, with additional stakeholders variably included. These constellations appeared to enable access to diverse groups, but it also raises questions familiar in the literature about gatekeeping and knowledge hierarchies: stakeholder presence can open doors while also shaping who is seen and which forms of knowledge are legitimized (40, 41). Authorship patterns reinforced this concern as migrant co-researchers were less often visible as authors than other stakeholders, converging with prior reviews that showed limited crediting of co-researchers from marginalized groups (42, 43). This matters because authorship is both recognition and a public record of who is allowed to speak for the research.

For participation across phases (c), the drop-off after data collection was noticeable: publications most often reported involvement in operationalization and fieldwork, much less in conceptualization, analysis, or outputs. This finding aligns with broader critiques that participatory processes tend to be phase-bound in practice (44) and risk reproducing the hierarchies PHR/P sets out to unsettle. This is especially problematic when co-researchers are not consistently included in those phases, where meaning is negotiated and disseminated (6). The idea of optimum participation (31) is helpful here as it acknowledges limitations of participation. Our data, especially the omissions and unclear coded participation in early and late phases, suggests that such routes might have been taken, yet reasons for excluding participation during certain research phases should be more explicit.

Reflections on participatory processes varied greatly (d). Notably, reflections on methods and external influences were more frequently discussed than ethical concerns or researcher positionality, suggesting that while structural constraints are acknowledged, internal power dynamics within research teams are less reported. We also noted great variations in how reflexivity was integrated and reported across the studies reviewed. This disconnect led to some inconsistencies during our coding process as mentioned in the methods section, and required the refinement of coding categories to theoretical and project-related reflections. The noted gaps and differences in how reflexivity was reported may be partially influenced by the type of publication. Traditional research articles adhering to structured formats, such as introduction, background, methods, and results, often provided limited reflections on participatory processes, although this was not universally consistent [(e.g., 45)]. In contrast, book chapters and anthologies tended to offer more detailed and nuanced accounts of these experiences [(e.g., 46, 47)]. Moreover, we noticed that among those projects who had published more than one publication, different aspects or phases of the projects were focused upon in the different publications. This suggests that what is omitted in one publication may not necessarily be absent in practice, but rather a reflection of the constraints of scientific publishing.

Implications

The findings of this review carry implications for the practice, publishing routines, and theoretical development of PHR/P with (and without) migrant communities. A key implication for practice concerns the operationalization of participation itself. While participation is a defining feature of PHR/P, our review demonstrates that migrants’ involvement across research phases often appeared limited. These patterns may reflect both structural constraints and varying interpretations of participatory principles (6, 44). We suggest more context-sensitive and flexible approaches to participation, grounded in ongoing negotiation and reflexivity on the constraints that shape migrants’ participation in participatory research (34, 48).

Regarding publishing routines, the review underscores the influence of publication formats on what is made visible. Journal articles, constrained by length and structure, tended to underreport reflexive and participatory dynamics. In contrast, alternative formats, such as anthologies or reports, offered more space for discussing team processes and tensions. This raises broader questions about how knowledge production is shaped by academic conventions (49). Promoting inclusive forms of authorship and offering explicit rationales when co-researchers are not named can support transparency, especially when anonymity or ethical concerns play a role. Additionally, expanding publishing standards to accommodate methodological reflections, e.g., via Supplementary materials or reflexivity statements, could help make participatory work more visible and learnable (50, 51).

Theoretically, the findings of this review do not imply a failure of participatory research itself but rather highlight the need for a more critical engagement with the conditions under which participation occurs and what is made visible in published accounts. They reinforce the existing demand for more differentiated understandings of participation, reflexivity, and power in PHR/P (6, 30, 33). A more explicit interrogation of how participation is defined, negotiated, and documented could help ensure that PHR/P does not merely include migrant communities but also critically reflects on the conditions that enable – or limit – their engagement. This is particularly relevant in contexts where questions of epistemic authority, selective inclusion, and representation intersect. Building on existing work (40, 43), further theorisation may help clarify how participatory principles can be meaningfully translated into practice.

Strengths and limitations

This review contributes to the growing body of research critically examining participatory health research by offering a structured synthesis of how participation and reflexivity are enacted and reported in studies with migrant communities. It is, to our knowledge, the first review to focus specifically on the German context and synthesises a diverse and heterogeneous body of literature. Methodically, the combined approach of deductive and inductive coding categories allowed for a nuanced analysis of reflexivity- related aspects.

Several limitations must be acknowledged. First, by restricting the scope to studies from Germany, the transferability of findings to other contexts may be limited. Second, despite comprehensive search strategies, it is possible that relevant studies, particularly those published in formats not indexed in the selected databases or written in non-German or non-English languages, were excluded. In addition, we did not assess the methodological quality or health-related results of the included studies, as our focus was intentionally directed towards participatory processes rather than study outcomes or rigor, due to the heterogeneity of study designs and topics. Third, the review relied on what was explicitly reported in the publications. As many studies provided limited details on participatory processes, particularly in traditional journal articles constrained by word limits, the findings may not fully reflect the extent or nature of participation or reflexivity in practice. Lastly, while our coding process sought to ensure consistency, some subjectivity in the interpretation of reflexivity and participatory practices is unavoidable, particularly given the varied ways these concepts were reported across studies.

Conclusion

This review mapped current descriptions of PHR/P with migrant communities in Germany, providing an overview of how participation and reflexivity are presented in published studies. While the included studies illustrate a broad thematic and methodological range, they also reflect recurring challenges in operationalizing participatory principles across research phases and documenting reflexive practice. The observed inconsistencies in reflexivity and its documentation emphasize the need for more structured yet adaptable approaches to reflect critically on power dynamics, roles, and methodologies. These findings contribute to a better understanding of the current state of the field and support further methodological development in how PHR/P with structurally marginalized groups is implemented and reported.

Data availability statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

Author contributions

HLL: Conceptualization, Data curation, Funding acquisition, Methodology, Writing – original draft. JL: Conceptualization, Data curation, Methodology, Writing – review & editing. DR: Funding acquisition, Validation, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declare that financial support was received for the research and/or publication of this article. This study was funded by Stiftung Deutsche Krebshilfe (German Cancer Aid) (Grant number: 70115255).

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The authors declare that Gen AI was used in the creation of this manuscript. Generative AI (ChatGPT from Open AI) was used for language refinement during manuscript preparation.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Supplementary material

The Supplementary material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fpubh.2025.1585178/full#supplementary-material

References

1. Statistisches Bundesamt (2022) Migrationshintergrund. Available online at: https://www.destatis.de/DE/Themen/Gesellschaft-Umwelt/Bevoelkerung/Migration-Integration/Glossar/migrationshintergrund.html (Accessed December 13, 2024).

2. Brzoska, P, and Razum, O. Die Gesundheit von Menschen mit Migrationshintergrund aus sozialepidemiologischer Sicht In: P Kriwy and M Jungbauer-Gans, editors. Handbuch Gesundheitssoziologie. Wiesbaden: Springer Fachmedien Wiesbaden (2020). 319–35.

3. Scuzzarello, S, and Moroşanu, L. Integration and intersectionality: boundaries and belonging “from above” and “from below”. Introduction to the special issue. Ethnic Racial Stud. (2023) 46:2991–3013. doi: 10.1080/01419870.2023.2182649

4. Will, A-K. The German statistical category “migration background”: historical roots, revisions and shortcomings. Ethnicities. (2019) 19:535–57. doi: 10.1177/1468796819833437

5. Kia-Keating, M, and Juang, LP. Participatory science as a decolonizing methodology: leveraging collective knowledge from partnerships with refugee and immigrant communities. Cultur Divers Ethnic Minor Psychol. (2022) 28:299–305. doi: 10.1037/cdp0000514

6. Roura, M, Dias, S, LeMaster, JW, and MacFarlane, A. Participatory health research with migrants: opportunities, challenges, and way forwards. Health Expect. (2021) 24:188–97. doi: 10.1111/hex.13201

7. Rustage, K., Crawshaw, A., Majeed-Hajaj, S., Deal, A., Nellums, L. B., Ciftci, Y., et al. Participatory research in health intervention studies involving migrants: a systematic review. BMJ Open. (2021) 11:e053678. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2021-053678

8. World Health Organization. Participatory health research with migrants: A country implementation guide: Country implementation support for impact (CIS). Geneva: World Health Organization (2022).

9. Goedhart, NS, Pittens, CACM, Tončinić, S, Zuiderent-Jerak, T, Dedding, C, and Broerse, JEW. Engaging citizens living in vulnerable circumstances in research: a narrative review using a systematic search. Res Involv Engagem. (2021) 7:59. doi: 10.1186/s40900-021-00306-w

10. Salmon, A, Browne, AJ, and Pederson, A. 'Now we call it research': participatory health research involving marginalized women who use drugs. Nurs Inq. (2010) 17:336–45. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1800.2010.00507.x

11. Dedding, C, Goedhart, NS, Broerse, JE, and Abma, TA. Exploring the boundaries of ‘good’ participatory action research in times of increasing popularity: dealing with constraints in local policy for digital inclusion. Educ Action Res. (2021) 29:20–36. doi: 10.1080/09650792.2020.1743733

12. Russell, J, Fudge, N, and Greenhalgh, T. The impact of public involvement in health research: what are we measuring? Why are we measuring it? Should we stop measuring it? Res Involv Engag. (2020) 6:63. doi: 10.1186/s40900-020-00239-w

13. Nitsch, M, Waldherr, K, Denk, E, Griebler, U, Marent, B, and Forster, R. Participation by different stakeholders in participatory evaluation of health promotion: a literature review. Eval Program Plann. (2013) 40:42–54. doi: 10.1016/j.evalprogplan.2013.04.006

14. Wilson, E, Kenny, A, and Dickson-Swift, V. Ethical challenges in community-based participatory research: a scoping review. Qual Health Res. (2018) 28:189–99. doi: 10.1177/1049732317690721

16. Dias, D., & Paulo Silva Cunha, J. Wearable health devices-vital sign monitoring, systems and technologies. Sensors, (2018), 18,:414. doi: 10.3390/s18082414

17. PartNet (2025) Network for Participatory Health Research Available online at: http://partnet-gesundheit.de/ (Accessed December 13, 2024).

18. von Unger, H. Partizipative Gesundheitsforschung: Wer partizipiert woran? Forum Qualit Sozialforschung. (2012) 13:1. doi: 10.17169/fqs-13.1.1781

19. Harting, J, Kruithof, K, Ruijter, L, and Stronks, K. Participatory research in health promotion: a critical review and illustration of rationales. Health Promot Int. (2022) 37:ii7-ii20. doi: 10.1093/heapro/daac016

20. Marent, B, Forster, R, and Nowak, P. Theorizing participation in health promotion: a literature review. Soc Theory Health. (2012) 10:188–207. doi: 10.1057/sth.2012.2

21. Cornwall, A, and Jewkes, R. What is participatory research? Soc Sci Med. (1995) 41:1667–76. doi: 10.1016/0277-9536(95)00127-S

22. Borda, OF. Investigating reality in order to transform it: the Colombian experience. Dialect Anthropol. (1979) 4:33–55. doi: 10.1007/BF00417683

24. Israel, BA, Schulz, AJ, Parker, EA, and Becker, AB. Review of community-based research: assessing partnership approaches to improve public health. Annu Rev Public Health. (1998) 19:173–202. doi: 10.1146/annurev.publhealth.19.1.173

25. Lütke Lanfer, H., and Landwehr, J. (2023). Methodische Herausforderungen der Partizipativen: Gesundheitsforschung: Reflexionen aus zwei Praxisprojekten. In D. Reifegerste, P. Kolip, and A. Wagner (Hrsg.), Wer macht wen für Gesundheit (und Krankheit) verantwortlich? Beiträge zur Jahrestagung der Fachgruppe Gesundheitskommunikation 2022 (S. 1–15). Bielefeld: Deutsche Gesellschaft für Publizistik- und Kommunikationswissenschaft e.V. doi: 10.21241/ssoar.88478

26. Baumeister, A, Chakraverty, D, Aldin, A, Seven, ÜS, Skoetz, N, Kalbe, E, et al. "The system has to be health literate, too" - perspectives among healthcare professionals on health literacy in transcultural treatment settings. BMC Health Serv Res. (2021) 21:716. doi: 10.1186/s12913-021-06614-x

27. Baillergeau, E, Veltkamp, G, Bröer, C, Helleve, A, Kulis, E, Lien, N, et al. Democratising participatory health promotion: power and knowledge involved in engaging European adolescents in childhood obesity prevention. Health Risk Soc. (2024) 26:201–21. doi: 10.1080/13698575.2024.2338120

28. Reason, P, and Bradbury, H. The SAGE handbook of action research. London: SAGE Publications Ltd (2008).

29. Cook, T., Abma, T., Gibbs, L., Gangarova, T., Harris, J., Kleba, M.E., et al. (2020). Impact in participatory Health Research: Icphr position paper. 3. doi: 10.13140/RG.2.2.15462.37440

30. Cornwall, A. Unpacking 'participation': models, meanings and practices. Community Dev J. (2008) 43:269–83. doi: 10.1093/cdj/bsn010

31. International Collaboration for Participatory Health Research (2013) Position paper 1: What is participatory Health Research? Available online at: http://www.icphr.org/uploads/2/0/3/9/20399575/ichpr_position_paper_1_defintion_-_version_may_2013.pdf (Accessed December 13, 2024).

32. Egid, BR, Roura, M, Aktar, B, Amegee Quach, J, Chumo, I, Dias, S, et al. 'You want to deal with power while riding on power': global perspectives on power in participatory health research and co-production approaches. BMJ Glob Health. (2021) 6:978. doi: 10.1136/bmjgh-2021-006978

33. von Unger, H, Huber, A, Kühner, A, Odukoya, D, and Reiter, H. Reflection labs: a space for researcher reflexivity in participatory collaborations. Int J Qual Methods. (2022) 21:16094069221142460. doi: 10.1177/16094069221142460

34. Bourke, L. Reflections on doing participatory research in health: participation, method and power. Int J Soc Res Methodol. (2009) 12:457–74. doi: 10.1080/13645570802373676

35. Arksey, H, and O'Malley, L. Scoping studies: Towards a methodological framework. Int J Soc Res Methodol. (2005) 8:19–32. doi: 10.1080/1364557032000119616

36. Tricco, AC, Lillie, E, Zarin, W, O'Brien, KK, Colquhoun, H, Levac, D, et al. Prisma extension for scoping reviews (PRISMA-ScR): checklist and explanation. Ann Intern Med. (2018) 169:467–73. doi: 10.7326/M18-0850

37. Bethmann, A, Hilgenböcker, E, and Wright, M. Partizipative Qualitätsentwicklung in der Prävention und Gesundheitsförderung In: M Tiemann and M Mohokum, editors. Springer Reference Pflege – Therapie – Gesundheit. Prävention und Gesundheitsförderung. Cham: Springer Berlin Heidelberg (2020). 1–13.

38. Freelon, D. ReCal: intercoder reliability calculation as a web service. Int J Internet Sci. (2010) 5:20–33.

39. Mayring, P. Qualitative Inhaltsanalyse: Grundlagen und Techniken. 13th ed. Wieselburg: Beltz (2022).

40. Askheim, OP. The co-researcher role in the tension between recognition, co-option and tokenism In: K Driessens and V Lyssens-Danneboom, editors. Involving service users in social work education, research and policy. Bristol: Policy Press (2021). 133–44.

41. Walker, M., and Boni, A. (2020). Epistemic justice, participatory research and valuable capabilities. In M. Walker and A. Boni (Eds.), Participatory research, capabilities and epistemic justice: A transformative agenda for higher education (1st ed. 2020, pp. 1–25). Cham: Springer International Publishing.

42. Groot, B, Haveman, A, and Abma, T. Relational, ethically sound co-production in mental health care research: epistemic injustice and the need for an ethics of care. Crit Public Health. (2022) 32:230–40. doi: 10.1080/09581596.2020.1770694

43. James, H, and Buffel, T. Co-research with older people: a systematic literature review. Ageing Soc. (2023) 43:2930–56. doi: 10.1017/S0144686X21002014

44. Jackson, T, Pinnock, H, Liew, SM, Horne, E, Ehrlich, E, Fulton, O, et al. Patient and public involvement in research: from tokenistic box ticking to valued team members. BMC Med. (2020) 18:79. doi: 10.1186/s12916-020-01544-7

45. Geldermann, A, Falge, C, Betscher, S, Jünger, S, Bertram, C, and Woopen, C. Diversitäts- und kultursensible Gesundheitsinformationen für mehr digitale Gesundheitskompetenz: Eine kollaborative Community-Forschung zu Barrieren und Bedarfen. Prävention Gesundheitsförderung. (2023) 19:75–94. doi: 10.1007/s11553-023-01012-z

46. Afeworki Abay, R, and Engin, K. Partizipative Forschung: Machbarkeit und Grenzen – Eine Reflexion am Beispiel der MiBeH-Studie In: B Behrensen and M Westphal, editors. Fluchtmigrationsforschung im Aufbruch: Methodologische und methodische Reflexionen. Wiesbaden; Heidelberg: Springer VS (2019). 379–96.

47. Sauer, M, Thomas, S, and Zalewski, I. Potentiale und Fallstricke von Peer-Research im Rahmen partizipativer Forschung mit unbegleiteten minderjährigen Geflüchteten In: C Frank, M Jooß-Weinbach, S Loick Molina, and G Schoyerer, editors. Eine Veröffentlichung des Deutschen Jugendinstituts e.V. (DJI). Der Weg zum Gegenstand in der Kinder- und Jugendhilfeforschung: Methodologische Herausforderungen für qualitative Zugänge. Weinheim, Basel: Beltz Juventa (2019). 222–44.

48. Santoro Lamelas, V, Valente, R, and Gresle, A-S. Evaluating participatory research projects through a harmonized, online, self-reflection, and impact-assessment methodology. Res Eval. (2024) 33:Article rvae051. doi: 10.1093/reseval/rvae051

49. Alley, S, Jackson, SF, and Shakya, YB. Reflexivity: a methodological tool in the knowledge translation process? Health Promot Pract. (2015) 16:426–31. doi: 10.1177/1524839914568344

50. Bordeaux, BC, Wiley, C, Tandon, SD, Horowitz, CR, Brown, PB, and Bass, EB. Guidelines for writing manuscripts about community-based participatory research for peer-reviewed journals. Progress Community Health Partnerships. (2007) 1:281–8. doi: 10.1353/cpr.2007.0018

51. Sarna-Wojcicki, D, Perret, M, Eitzel, MV, and Fortmann, L. Where are the missing coauthors? Authorship practices in participatory research. Rural Sociol. (2017) 82:713–46. doi: 10.1111/ruso.12156

52. Evangelidou, S, Schouler-Ocak, M, Movsisyan, N, Gionakis, N, Ntetsika, M, Kirkgoeze, N, et al. Health promotion strategies toward improved healthcare access for migrants and refugees in Europe: Myhealth recommendations. Health Promot Int. (2023) 38:47. doi: 10.1093/heapro/daac047

53. Herbert-Maul, A, Abu-Omar, K, Streber, A, Majzik, Z, Hefele, J, Dobslaw, S, et al. Scaling up a community-based exercise program for women in difficult life situations in Germany-the BIG project as a case-study. Int J Environ Res Public Health. (2021) 18:9432. doi: 10.3390/ijerph18189432

54. Fleuren, T, Herbert-Maul, A, Linder, S, Geidl, W, Reimers, A, and Abu-Omar, K. Bewegungsförderung bei Menschen in schwierigen Lebenslagen. Bewegungstherapie Gesundheitssport. (2020) 36:257–63. doi: 10.1055/a-1292-6711

55. Kieslinger, J, Kordel, S, and Weidinger, T. Capturing meanings of place, time and social interaction when analyzing human (im)mobilities: strengths and challenges of the application of (im)mobility biography. Forum Qualit Sozialforschung. (2020) 21:347. doi: 10.17169/fqs-21.2.3347

56. Kordel, S., Weidinger, T., and Hachmeister, S. (2018) Lebenswelten geflüchteter Menschen in ländlichen Regionen qualitativ erforschen: methodische Überlegungen zu einem partizipativ orientierten Forschungsansatz. Thünen Working Paper 106. Available online at: https://www.thuenen.de/media/publikationen/thuenen-workingpaper/ThuenenWorkingPaper_106.pdf (Accessed September 15, 2023).

57. Koschollek, C, Kuehne, A, Amoah, S, Batemona-Abeke, H, Bursi, T, Mayamba, P, et al. From peer to peer: reaching migrants from sub-Saharan Africa with research on sexual health utilizing community-based participatory health research. Survey Methods Insights Field. (2019). doi: 10.13094/SMIF-2019-00011

58. Pallasch, G, Salman, R, and Hartwig, C. Verbesserung des Impfschutzes für sozial benachteiligte Gruppen unter Mitarbeit von Vertrauenspersonen - Ergebnisse einer kultur- und sprachsensiblen intervention des Gesundheitsamtes Stade und des ethno-Medizinischen Zentrums für Migrantenkinder im Altländer Viertel [improvement of protection given by vaccination for socially underprivileged groups on the basis of "key persons approach" -- results of an intervention based on cultural and language aspects for children of immigrants in Altlander Viertel provided by the health Department of Stade]. Gesundheitswesen. (2005) 67:33–8. doi: 10.1055/s-2004-813912

59. Perplies, C, Biddle, L, Benson-Martin, J, Joggerst, B, and Bozorgmehr, K. Förderung der psychischen Gesundheit von geflüchteten Menschen. Prävention Gesundheitsförderung. (2022) 17:505–11. doi: 10.1007/s11553-021-00899-w

60. Salman, R. Gesundheit mit Migranten für Migranten – die MiMi Präventionstechnologie als interkulturelles Health-Literacy-Programm. Public Health Forum. (2015) 23:109–12. doi: 10.1515/pubhef-2015-0040

61. Salman, R, and Weyers, S. Mimi project - with migrants for migrants In: T Koller, World Health Organization, editors. Poverty and social exclusion in the WHO European region: Health systems respond. Copenhagen: WHO Regional Office for Europe (2010). 52–63.

62. Samkange-Zeeb, F, Ernst, SA, Klein-Ellinghaus, F, Brand, T, Reeske-Behrens, A, Plumbaum, T, et al. Assessing the acceptability and usability of an internet-based intelligent health assistant developed for use among Turkish migrants: results of a study conducted in Bremen, Germany. Int J Environ Res Public Health. (2015) 12:15339–51. doi: 10.3390/ijerph121214987

63. Schön, E. Gesellschaftliche Teilhabe von Menschen mit Behinderung und Migrationshintergrund in ländlichen Regionen: Erkenntnisse aus der wissenschaftlichen Begleitung des Modellprojekts Willkommen. Teilhabe. (2013) 52:102–8.

64. von Unger, H., Gangarova, T., Ouedraogo, O., Flohr, C., and Spennemann, N., & T.Wright, M. (2013). Stärkung von Gemeinschaften: Partizipative Forschung zu HIV-Prävention mit Migrant/innen. Prävention Gesundheitsförderung, 8, 171–180. doi: 10.1007/s11553-013-0399-9

Keywords: participatory health research, migrant health, peer research, health equity, reflexivity, scoping review

Citation: Luetke Lanfer H, Landwehr J and Reifegerste D (2025) Participatory health research and promotion with migrant communities in Germany: a scoping review. Front. Public Health. 13:1585178. doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2025.1585178

Edited by:

Jeff Bolles, Francis Marion University, United StatesReviewed by:

Sergio Villanueva Baselga, University of Barcelona, SpainCatharina Thiel Sandholdt, University of Copenhagen, Denmark

Copyright © 2025 Luetke Lanfer, Landwehr and Reifegerste. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Hanna Luetke Lanfer, aGFubmEubHVldGtlbGFuZmVyQHVuaS1iaWVsZWZlbGQuZGU=

Hanna Luetke Lanfer

Hanna Luetke Lanfer Janna Landwehr

Janna Landwehr Doreen Reifegerste

Doreen Reifegerste