Abstract

About one million Forcibly Displaced Myanmar Nationals (FDMN)/Rohingya refugees live in the refugee camps of Cox’s Bazar, experiencing recurring vaccine-preventable disease outbreaks despite established vaccination programs. This scoping review focused on the evidence for individual and context barriers, drivers, and interventions for childhood vaccination uptake of FDMN/Rohingya refugees in Cox’s Bazar. Four databases and grey literature were systematically searched. Theoretical frameworks were used to organize findings. 4,014 records were screened, and 21 articles included. The literature was heterogenous. Barriers and drivers for FDMN/Rohingya refugees receiving vaccination focused on motivation relating to trust, beliefs and fears (19 barriers and drivers in 11 articles), accessibility and information availability (19 barriers and drivers in 11 articles), as well as knowledge and ability (eight barriers and drivers in nine articles), and socio-cultural and gender-related norms and social support (seven barriers and drivers in eight articles). For health service providers facilitating vaccinations, context factors, such as the availability of vaccines and staff, were most frequently identified (13 barriers and drivers in 12 articles). Interventions mostly related to vaccination campaigns and information/education. They often lacked detail and formal evaluations. Future research and interventions on childhood vaccination should consider barriers and drivers for health service providers, the diversity of the camp population, and explore the role of community/religious leaders and gender-related social norms. Additionally, the reporting and evaluation of interventions should be strengthened.

Systematic review registration:

https://doi.org/10.17605/OSF.IO/N6D3URL; https://osf.io/n6d3z.

1 Introduction

1.1 Background

Vaccines are one of the most cost-effective and lifesaving public health measures to date, importantly reducing the burden of vaccine-preventable diseases (VPD) such as poliomyelitis, measles and rubella globally (1). However, they have not been able to reach their full potential in vulnerable groups like refugee populations. The global literature reports that the latter experience higher VPD burden and lower immunisation rates than other populations due to several reasons (2, 3): These include overcrowding in refugee camps and poor water, sanitation, and hygiene (WASH) conditions that facilitate the rapid spread of VPD (3, 4). Multiple challenges exist in accessing and delivering health services (including vaccines) in refugee camps on the context level (5). Vaccine hesitancy and lack of vaccine confidence can cause delay or refusal of vaccinations despite their availability on an individual level (6). This is a common phenomenon globally with reasons including vaccine misinformation, unfamiliarity with or mistrust of health systems, language barriers, and sociocultural differences (7).

One group especially at risk are Forcibly Displaced Myanmar Nationals (FDMN)/Rohingya refugees. In 2017, 700,000 FDMN/Rohingya fled to Cox’s Bazar, Bangladesh, following an increase in longstanding ethnic and religious persecution of Rohingya people in Myanmar (8). They joined approximately 300,000 previously settled Rohingya refugees. Access to health services and vaccinations in Myanmar was found to be highly inequitable for Rohingya with a study showing 60% of Rohingya children arriving in Bangladesh had never previously been vaccinated (9). Densely populated makeshift settlements, coupled with a poor health status and low immunisation coverage led to several VPD outbreaks (4), including the largest reported diphtheria outbreak in refugee settings so far (10).

Denied of citizenship in Myanmar, FDMN/Rohingya refugees are the largest stateless population in the world, currently estimated at just over 1 million people (11, 12). They live, spread over 35 camps, in two subdistricts of Cox’s Bazar, Uhyia and Teknaf (11, 12). The camps vary in size and accessibility, and function as self-organised, independent districts, each divided into blocks and subblocks. The health response including the vaccination program is led by the Health Sector Strategic Advisory Group with representatives from the Government of Bangladesh, United Nations bodies, national and international non-governmental organisations (NGOs) (8). To control and prevent further outbreaks, mass vaccination campaigns were initiated in September 2017, and routine immunisation services established in February 2018 (13). Essential health services including vaccinations are delivered by 93 health posts, 46 primary health care centres and five field hospitals provide essential health services including vaccinations (14). Vaccinations are provided via fixed vaccination sites and community outreach, and follow the Expanded Program on Immunisation for Bangladesh (15). Multiple professional groups are involved in facilitating vaccinations. Community health workers (CHWs) from the refugee and local host population counsel community members and support vaccination provision. Vaccinators are mostly from the local host community and receive special training. The health service provision of each facility is overseen by a health facility manager. Additionally, the community-based Camp-in-Charge (CiC) group in each camp and around 15 Immunisation partners (including BRAC, UNHCR, UNICEF and IOM) support the vaccination program (13). Official numbers for vaccination coverage of Rohingya children in Cox’s Bazar are lacking, and estimates range from 23–78% (16). Modelling studies have suggested that VPD outbreaks are still likely and a threat to FDMN/Rohingya refugees as well as host communities (10, 17).

To increase vaccination coverage, it is essential to understand the complex and multifaceted nature of vaccination behaviours and processes (18). This includes examining both demand and supply-side factors, including assessment of the barriers and drivers for patients or caregivers in receiving vaccinations, as well as the barriers and drivers for health service providers (HSP) in facilitating them (18). A global evidence review found that for HSP working in migrant or refugee settings, numerous barriers to delivering vaccinations exist (19). These may include resource and capacity constraints, cold chain limitations, inaccessibility, insufficient safety for professionals, or lacking knowledge of migrant health care needs and culturally competent care (19).

To date, the available evidence on barriers, drivers and interventions for childhood vaccination for FDMN/Rohingya refugees and HSP in Cox’s Bazar has not been reviewed.

1.2 Aim and objectives

The aim of this scoping review was to gain understanding and review the research landscape of childhood vaccinations in FDMN/Rohingya refugees in Cox’s Bazar to inform future research and strategies to increase vaccination uptake.

The objectives were to identify individual and context barriers and drivers to receiving childhood vaccination amongst FDMN/Rohingya refugee caregivers and facilitating childhood vaccinations by HSP in Cox’s Bazar. Exploring these different perspectives ensured that both the demand and supply side of vaccination coverage are considered (20). A further objective was to identify vaccination interventions that have been recommended or implemented (with or without evaluation), in this population.

2 Methods

2.1 Scoping review approach

This review was conducted as part of a broader scoping review focusing on childhood vaccinations and COVID-19 protective behaviours (including vaccinations) of FDMN/Rohingya refugees in Cox’s Bazar. This paper presents the childhood vaccination part only. This scoping review followed the methodology of the Joanna Briggs Institute (JBI) (21) based on the Arksey and O’Malley framework for scoping reviews (22). A protocol was uploaded onto the Open Science Framework (OSF) website prior to accessing the data.1 The Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic reviews and Meta-Analysis extension for Scoping Reviews (PRISMAScR) guided the reporting (see Supplementary material 1 for PRISMAScR Checklist) (23).

2.2 Theoretical background: modified COM-B framework and behaviour change wheel

This review was underpinned by the Capability-Opportunity-Motivation-Behaviour (COM-B) framework and Behaviour Change Wheel (BCW) (24), modified for vaccination behaviours (see Figure 1 and Table 1).

Figure 1

Modified COM-B framework for vaccination (18).

Table 1

| Intervention type | Intervention description | COM-factor addressed by the intervention type | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Capability | Physical opportunity | Social opportunity | Motivation | ||

| Information/education | Increasing knowledge or understanding | X | X | ||

| Persuasion | Using communication to induce positive/negative feelings or stimulate action | X | |||

| Incentivisation | Creating an expectation of a reward | X | |||

| Coercion | Creating an expectation of punishment or cost | X | |||

| Training | Imparting skills | X | X | X | |

| Restriction | Using rules to reduce the opportunity to engage in the target behaviour or in competing behaviours | X | X | ||

| Environmental restructuring | Changing the physical or social context. | X | X | X | |

| Modelling | Providing an example of people to aspire to or imitate. | X | X | ||

The modified COM-B framework suggests that four inter-linked factors influence vaccination behaviour: Capability (e.g., knowledge, skills), physical opportunity (information, access, health systems), social opportunity (support, norms) and motivation (attitudes, confidence, trust). All factors affect an individual’s motivation for positive vaccination behaviours, with caregivers bringing their children to receive vaccinations and HSP facilitating the provision of vaccinations. The framework’s comprehensive approach, incorporating both individual and context influences (20) on the demand and supply side, was deemed particularly appropriate to categorize the barriers and drivers.

The modified BCW links the four COM factors with eight types of interventions: Information/education, persuasion, incentivisation, coercion, training, restriction, environmental restructuring, and modelling. These intervention types have proved effective at addressing specific COM-factors, and hence ensure that the appropriate interventions are employed (24). Table 1 describes the intervention types and shows which COM-factors they effectively address. The four COM-factors and eight intervention types of the BCW were used throughout this review to organise the barriers, drivers, and intervention data, respectively.

2.3 Search strategy and information sources

The electronic databases Ovid MEDLINE, Excerpta Medica database (Embase), Global Health and Web of Science were searched using Boolean operators, keywords, and subject headings. Initial database searches and screening were conducted simultaneously for both topics up to October 2021. In June 2024, an update search was conducted. Details on search strings are provided in Supplementary material 3. Grey literature was searched systematically through the websites Google, http://Reliefweb.int and http://Humanitarianresponse.info. In addition, individual websites from development partners of the Ministry of Health, United Nations (UN) and non-governmental organizations (NGO) in Cox’s Bazar were searched (see Supplementary material 4). A snowball search of reference lists was conducted.

2.4 Eligibility criteria

The protocol used the Population, Concept, Context (PCC) framework for inclusion and exclusion criteria (21) as recommended for scoping reviews as per the JBI methodology (see Supplementary material 2).

Childhood vaccinations in this review are defined as vaccinations given to a person aged 0–18 years of age as part of routine or supplemental immunisation programs (such as mass vaccination campaigns).

Regarding the concept of vaccination, two distinct target behaviours were defined. Receiving vaccinations refers to FDMN/Rohingya refugee caregivers accepting and accessing vaccination services and bringing their child(ren) for vaccination. Facilitating vaccinations involves HSPs educating, enabling, and administering childhood vaccinations.

2.5 Study selection

Articles were screened at title/abstract [using Rayyan (25)] and full-text level by two independent investigators (ZY, SR). A third researcher (CJ) was involved when there were disagreements on eligibility.

A data extraction matrix based on the PCC framework was developed in Microsoft Excel, and data on barriers, drivers and interventions were extracted from full texts by one researcher (ZY). This followed a pilot data extraction of three studies in which results were compared with two other researchers for consistency (SR, CJ). Queries were discussed among the researchers and agreed by consensus. Records and data were managed with Endnote and Excel programs.

2.6 Data extraction and synthesis

Data synthesis was guided by the principles of textual narrative synthesis (26), for which a table of COM-factors and target behaviours (receiving, facilitating) was developed to organise barriers and drivers. It was also noted whether this was the perspective of FDMN/Rohingya refugees, HSP, or both. Where data permitted, similarities and differences across camps and population groups (e.g., age, gender) were identified. Similarly, a table was developed to organise intervention data into recommended, implemented or evaluated interventions and by intervention types of the BCW (24).

2.7 Critical appraisal of evidence sources

Though critical appraisal is optional for scoping reviews (22), it was deemed useful in the context of mapping out the evidence base and assessing the quality of the literature landscape. Three tools were used to critically appraise different article types: The Mixed Method Assessment Tool (MMAT) for research studies (27), the Authority, Accuracy, Coverage, Objectivity, Date, Significance Checklist (AACODS) for grey literature (28), and the JBI Checklist for text and opinion pieces (29). This was done by two researchers independently (ZY, SL). Scores were compared and agreed by consensus (see Supplementary material 6).

3 Results

3.1 Overview of results

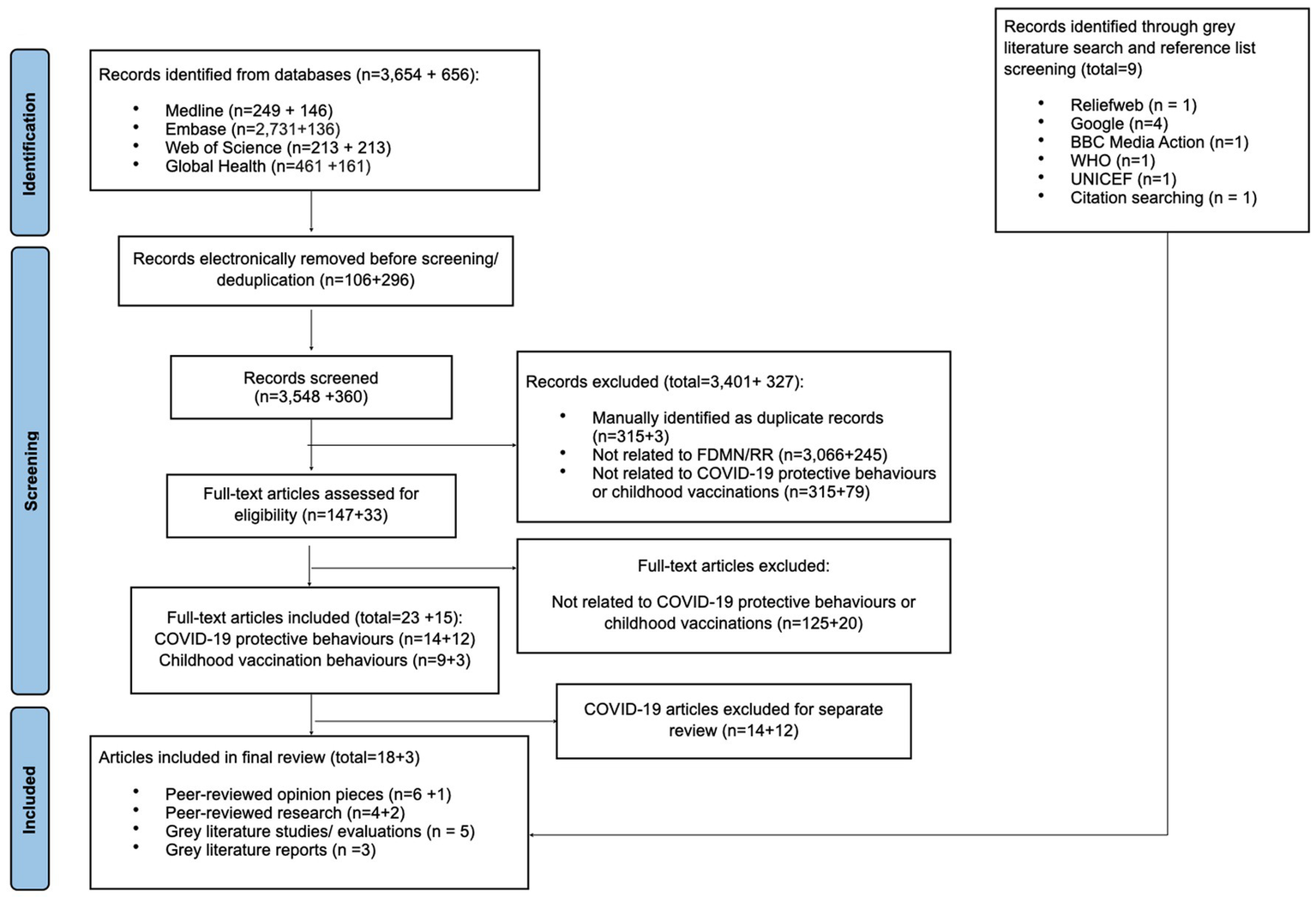

The results shown here comprise of the original search in 2021 and the update search in 2024, Numbers are given as totals with the breakdown of each search in brackets. The systematic search identified a total of 4,310 (3,654 in 2021 + 656 in 2024) entries. After de-duplication, title/abstract screening of 3,908 (3,548 in 2021 + 360 in 2024) and full-text screening of 180 (147 in 2021 + 33 in 2024) records, 12 (9 in 2021 + 3 in 2024) articles were found to be eligible. Nine additional articles were added through grey literature searches and citation screening, leading to a total of 21 included articles (see Figure 2). Articles were excluded as not aligned with the target population, scoping review concepts or context (as per PCC see Supplementary material 2).

Figure 2

PRISMA flowchart of included studies (18).

An overview of all included articles is provided in Tables 2, 3 (for further details see Supplementary material 5). The research landscape consists of heterogenous article types. Thirteen articles were published in peer-reviewed journals of which seven were opinion pieces (4, 30–35) and six were research articles (16, 36–40). Eight grey literature articles were found, comprised of three reports (13, 41, 42), three NGO/UN response evaluation reports (11, 43, 44) and two non-peer reviewed research studies (45, 46). For peer-reviewed and grey literature based on research, qualitative (16, 36, 40, 45) approaches and mixed methods were predominantly applied (11, 43, 44, 46), followed by quantitative (cross-sectional) (37–39) approaches. All articles were published between 2018 and 2023. Most interventions were reported from 2017 and 2018 (4, 11, 13, 30–34, 36–39, 42, 43), and one from 2020 (41).

Table 2

| First author, year | Evidence source | Type of research | Target group | Location | Target behaviour | Critical appraisal (quality criteria met/total) | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Primary research | Opinion piece | Quantitative | Qualitative | Mixed methods | FDMN/Rohingya refugees | HSP | Both | Cox’s Bazar – general | Specific camps | Receiving | Facilitating | ||

| Ahmed, 2023 (16) | 7/7 | ||||||||||||

| Chan, 2018 (30) | 6/6 | ||||||||||||

| Feldstein, 2020 (38) | 6/7 | ||||||||||||

| Jalloh, 2019 (36) | 7/7 | ||||||||||||

| Jalloh, 2020 (31) | 5/6 | ||||||||||||

| Hsan, 2019 (33) | 5/6 | ||||||||||||

| Hsan, 2020 (32) | 5/6 | ||||||||||||

| Khan, 2019 (37) | 6/7 | ||||||||||||

| Khan, 2023 (35) | 4/5 | ||||||||||||

| Qadri, 2018 (34) | 5/6 | ||||||||||||

| Qayum, 2023 (40) | 7/7 | ||||||||||||

| Rahman, 2019 (4) | 5/6 | ||||||||||||

| Summers, 2018 (39) | 6/7 | ||||||||||||

Characteristics of included peer-reviewed literature.

Grey: Applies; White: Does not Apply.

Table 3

| First author, year | Evidence source | NGO/UN | Target group | Location | Target behaviour | Critical appraisal (quality criteria met/total) | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Primary research | Report | Response evaluation report | Situation report | NGO | UN agency | FDMN/Rohingya refugees | HSP | Both | Cox’s Bazar – general | Specific camps | Receiving | Facilitating | ||

| Bangladesh Health Watch 2019 (42) | 22/29 | |||||||||||||

| BBC Media Action, Translators without Borders, 2019 (45) | 16/24 | |||||||||||||

| BRAC, 2019 (46) | 28/30 | |||||||||||||

| Red R India, 2018 (43) | 22/30 | |||||||||||||

| UNHCR, 2018 (11) | 28/30 | |||||||||||||

| UNICEF, 2018 (44) | 28/30 | |||||||||||||

| UNICEF, 2020 (41) | 15/23 | |||||||||||||

| SEARO WHO, 2019 (13) | 22/29 | |||||||||||||

Characteristics of included grey literature.

Grey: Applies; White: Does not Apply.

Most articles included barriers and drivers from the perspectives of FDMN/Rohingya refugee population (4, 16, 31–33, 35–40, 45), or both HSP and FDMN/Rohingya refugees’ perspectives (11, 34, 41–44, 46). Only two articles related to HSP views only (13, 30). Information on location in the camps and population subgroups was collected. However, it was not possible to organise findings by these characteristics due to a lack of detail and heterogeneity of studied outcomes. Only one evaluation study on vaccination specific interventions was found (40), the impact for most interventions was described through authors’ reflections, post vaccination campaign coverage surveys or general evaluations of the NGO/UN response.

Critical appraisal found that included articles met a moderate to high range (between 65 and 100%) of quality criteria. On average, 80% of quality criteria were met for grey literature appraised with the AACODS, 86% for opinion pieces appraised with the JBI checklist and 90% for research studies appraised with the MMAT. Most research studies lost scores on the risk of non-response bias, whilst grey literature lost scores for lack of peer-review and editing by reputable authority (see Supplementary material 6).

3.2 Main barriers and drivers identified

3.2.1 Individual factors

As demonstrated in Tables 4, 5, barriers and drivers relating to the capability factor of the COM-B model were only identified for FDMN/Rohingya refugees receiving vaccination (eight barriers and drivers reported by nine articles) and were mostly related to knowledge. No articles reported on capability barriers or drivers to HSPs facilitating vaccinations.

Table 4

| Individual factors | Context factors | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Capability | Motivation | Social opportunity | Physical opportunity |

| Barriers and drivers (N = 8), articles (N = 9) | Barriers and drivers (N = 19), articles (N = 11) | Barriers and drivers (N = 7), articles (N = 8) | Barriers and drivers (N = 19), articles (N = 11) |

| Knowledge + Knowledge of why childhood vaccination is important (36, 40, 41, 43, 45), in registered camps only (16) + Parental/Father’s education (16) + Knowledge about own children’s vaccination status (46) – Lack of knowledge about vaccination campaigns in camps (37, 38), for makeshift more than registered camps (40) – Lack of knowledge about vaccine preventable diseases, vaccinations (16, 37), vaccination schedule (41) or need to get multiple vaccinations on the same day (36) – Spread of misinformation via face-to-face and electronic communication with FDMN/Rohingya refugees in camps, hosts and home county (45) Ability – Sickness so cannot bring children for vaccination (37) or receive vaccination (40) – In makeshift camps, forgetting to attend (40) | Confidence/trust + Confidence from not seeing/hearing of children with serious side effects or dying after vaccination campaigns (36) + Confidence in receiving good care from vaccination campaign staff (36) +Trust in religious leaders, elders, village doctors, pharmacists, mothers trained by NGOs as sources of information (36) + Increased trust of SP from previous vaccination campaigns (42) – Lack of trust in appointed community leaders “mahjees” on health issues due to their liaison role with the army (36) – Feeling misled by some religious leaders due to their initial instructions to refuse vaccination (36) or their practices not grounded in Qur’an (36) – Lack of trust in vaccinators’ skills and treatment of children (36) – Lack of trust in volunteers reassurance about not becoming Christian after vaccination (45) – Being denied access to healthcare in home country (4, 32, 33) Values/beliefs + Belief that vaccines prevent disease (36) – Belief that combination vaccinations are designed to kill the Rohingya population (36) – Beliefs that vaccination will leave mark forbidden in Islam and people will become a Christian if vaccinated (36, 45) – Competing priorities, e.g., poor health, drinking water, relief collection of adult (36, 37) and of child (38) – Do not believe that vaccines are important (40) Emotions/impulses/feelings + Having previously lost at least one child (16) + History of previous admission (16) – Fear of vaccine (40, 42) or multiple vaccines (36), side effects (4, 36, 37, 40, 45) including weakness, death (36, 45) and needles (38) – Fear of contracting COVID-19 in vaccination facility (41) – Fear of pain for child (37) and fear amongst children when see other children in pain who receive vaccinations (36) – Dislike taste of vaccine (in registered more than makeshift camps (40) | Social and cultural norms – Women and girls cannot interact or show part of their body to men outside their family (31, 36) – Norm in Myanmar for children to receive one vaccination (not combination vaccinations) (36, 37) – Norm to seek healthcare outside of formal healthcare system (39, 46) Social Support + Use of female vaccinators, who encourages vaccinations for women and girls and provides opportunity to ask questions (13) + Ability to ask questions to HSP and inform Camp in Charge if concerns arise (45) + Having more than two children (16) – Recent arrival of refugees – registered vs. makeshift camps (16) | Availability of information + Receiving information about immunization via Friday prayers, household visit, community meetings, information centres, megaphones, video documentary (13, 16, 36, 44) + Presence of electronic device (16) – Lack of information from vaccinators about vaccines and side effects (36), on why cholera vaccination is needed (37) and on time and place of vaccination campaigns (37) – Language barriers between service providers and caregivers (36, 37) Geographical access + Preference for vaccination sites to be in close proximity (43, 46) – Vaccination sites located too far away (37) – First access to vaccines upon arrival in camps (46) Convenience, appeal, and appropriateness of vaccination – Long queues at vaccination sites (37) and waiting times (40) – Short campaign durations (37) – No privacy or gender sensitivity in place at vaccination sites (31, 36) leading to preference amongst women for household visits (36) – Absence from camp during vaccination campaign–makeshift and registered camps (40) – For makeshift camps-not having time or being too busy (40) Availability of resources – Insufficient vaccines at vaccination sites (11, 37) – Insufficient vaccinators (36, 37) and predominantly male (36) + Father’s employment (16) – Vaccinator refusing to vaccinate (40) – Clinic was closed (40) Rights/regulation/legislation – Vaccination services suspended due to COVID-19 pandemic (41) – Restrictions on movement during COVID-19 pandemic (41) |

Overview of barriers (−) and drivers (+) to receiving vaccinations (FDMN/Rohingya refugees) arranged by COM-factors.

Table 5

| Individual factors | Context factors | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Capability | Motivation | Social opportunity | Physical |

| Barriers and drivers (N = 0), articles (N = 0) | Barriers and drivers (N = 3), articles (N = 3) | Barriers and drivers (N = 6), articles (N = 4) | Barriers and drivers (N = 13), articles (N = 12) |

| Emotions/impulses/feelings – Campaign fatigue with multiple dose vaccinations and continuous influx (38) Confidence/trust + Confidence amongst religious leaders after several months of vaccination campaigns (36) – Difficulties in convincing parents to bring children for vaccination in MSs and spontaneous settlements (13) | Social, cultural norms and values + Female vaccinators have easier access to families and teenage girls (13) – Socio-cultural issues (38) – Disapproval amongst religious leaders of women and girls being publicly vaccinated by men (36) Social support + Collaborative and efficient partnerships with other organizations (13) + Good relationship with government (13, 44) – Lack of community engagement (44) | Availability of resources + WHO/GAVI deliver OCV vaccinations free of charge (13) – Lack of evidence of Rohingya children’s vaccination status (36, 37) – Problems with vaccination record management (30) – Challenges establishing fully functioning health facilities (44) – Vaccination services suspended due to COVID-19 pandemic (41) – Insufficient vaccines at vaccination sites (11, 32, 34, 38) – Insufficient vaccinators (36) Geographical access – Scattered settlements over a large area (37) – Constant new arrivals during vaccination campaign (34, 37–39) and population movement (13, 30, 37) – Rapidly evolving conflict situation (38) Convenience – Inconvenience of administering multiple vaccinations compared to one (32) and intramuscular vaccinations compared to oral vaccinations (37, 38) Rights/regulation/legislation – Rohingya are unregistered (30, 39) – Political and resource constraints (38) | |

Overview of barriers (−) and drivers (+) to facilitating vaccinations (HSP) arranged by COM-factors.

The main capability driver was refugees’ knowledge of why childhood vaccinations are important (16, 36, 40, 41, 43, 45, 46). Barriers included a lack of knowledge about how to access vaccinations such as details on the time and place of campaigns (37, 38, 40), poor awareness of the available vaccines (16, 37) and vaccination schedules (36, 41), and vaccination misinformation (45). Other barriers, each mentioned by one article, were sickness causing inability to bring children for vaccination (37) and forgetting to attend (40).

Motivation-related factors were also predominantly found for caregivers’ receiving vaccinations (19 barriers and drivers reported by 11 articles) rather than HSPs facilitating vaccinations (3 barriers and drivers reported by 3 articles). They could be subcategorised into motivation related factors linked to confidence/trust, values/beliefs, and emotions/impulses or feelings.

Emotion, impulse and feeling related barriers were mostly found for FDMN/Rohingya refugees receiving vaccinations. These included fear of vaccines (40, 42), pain (36, 37), side effects (4, 36, 37, 40, 45), needles (38), weakness and death (36, 45). Fear of contracting COVID-19 from vaccination facilities was also mentioned in one article (41). Drivers included previous experiences of having lost a child or previous admission to hospital (16). For HSP facilitating vaccinations, one article mentioned ‘campaign fatigue’ for multidose vaccines, when too many campaigns were undertaken (38).

Various values and beliefs around vaccinations were identified. Barriers for FDMN/Rohingya refugees included beliefs that vaccines cause people to become Christian, vaccines leave marks forbidden in Islam that prevent the vaccinated individual from going to heaven (36, 45), or that vaccines were designed to kill the Rohingya population (36). Both supportive and opposing beliefs about the importance of vaccination were reported in terms of their impact on preventing disease. Some believed that vaccines were not important (40), whilst others were motivated by the belief that vaccines effectively prevent disease (36). Three articles discussed competing priorities for FDMN/Rohingya refugees, e.g., around poor health, collection of drinking water, relief collection and attending school (36–38).

Confidence and trust were described as important factors with conflicting data regarding the role of community/religious leaders and vaccinators, being both a driver and a barrier to receiving vaccinations. A lack of trust in appointed leaders “mahjees” was noted due to their liaison role in the army and in religious leaders when they had initially instructed to refuse vaccinations, or claimed vaccination practices were not grounded in the Qur’an (36). However, trust in vaccinations was also noted when community leaders, elders, village doctors, and in particular religious leaders recommended vaccinations, following training by NGOs (36). Evidence of both confidence in receiving good care from vaccinators (36), as well as problems with vaccinators or volunteers were found. These encompassed a lack of trust in vaccinators or volunteers’ treatment of children (36), and their attempts to reassure FDMN/Rohingya refugees that they would not become Christian following a vaccination (45).

A further barrier included a lack of trust due to having been denied access to health care in their home country (4, 32, 33). Encouragingly, for caregivers and religious leaders, trust in vaccines appeared to be correlated with time and experience in Cox`s Bazar, having increased confidence in vaccines from not seeing or hearing of children having serious side effects following vaccination campaigns (36, 42). Encouragingly, for caregivers and religious leaders, trust in vaccines appeared to be correlated with time and experience in Cox`s Bazar, having increased confidence in vaccines from not seeing or hearing of children having serious side effects following vaccination campaigns (36, 42). Corresponding to the aforementioned lack of trust by FDMN/Rohingya refugees, a barrier for HSPs facilitating vaccinations discussed by one article was the difficulty in convincing parents to bring children for vaccination in makeshift and spontaneous settlements (13), whilst a driver for HSPs was the increased confidence amongst religious leaders after several months of vaccination campaigns (36).

3.2.2 Context factors

Barriers and drivers related to physical and social opportunity (context factors) were identified for both caregivers and HSPs. Physical opportunity barriers and drivers were most reported for caregivers receiving vaccinations (19 barriers and drivers reported by 11 articles) and for HSPs facilitating vaccinations (13 barriers and drivers reported by 12 articles). In contrast, fewer social opportunity barriers and drivers were reported for caregivers receiving vaccinations (seven barriers and drivers across eight articles) and for HSPs facilitating vaccinations (six barriers and drivers across four articles).

Physical opportunity related barriers and drivers could be categorised into several key areas: the availability of information, geographical access, convenience/appeal of vaccination, availability of resources, and rights/regulation and legislation.

A common barrier and driver for receiving vaccinations for FDMN/Rohingya refugees was the availability (or lack) of information. Issues included a lack of information about the vaccines from vaccinators, the vaccination campaigns/services being held (36, 37) and language barriers (36, 37). On the other hand, information provided via different communication/awareness campaigns was a driver to increase vaccination uptake for FDMN/Rohingya refugees receiving vaccinations (13, 16, 36, 44). One article commented on the presence of an electronic device in the household being associated with higher vaccination rates (16).

The availability of resources was another significant barrier for both caregivers and HSP. Barriers involved the (in) availability of vaccines (11, 32, 34, 37, 38) and a lack of vaccinators (36, 37), which were predominantly male when available (36). For HSP specifically, further barriers such as the lack of, or problems with, vaccination records (30, 36, 37) and difficulties establishing health facilities (44) were identified.

Geographical access, logistical and appeal issues also played a crucial role for caregivers receiving vaccinations and HSPs facilitating vaccinations. The scattered settlements made accessing and delivering vaccinations difficult (37, 43, 46), with a preference for vaccination sites to be in close proximity (43, 46). In addition, the influx and constant movement of refugees made facilitating vaccinations for HSP challenging (13, 30, 34, 37–40). Logistical issues for HSPs included the relatively complex administration of multidose and/or intramuscular vaccinations (32, 37, 38) in comparison to oral vaccines (37). For FMDN/Rohingya refugees, long queues (37), short campaign durations (37), and vaccination sites with limited privacy or gender considerations (31, 36), and insufficient female vaccinators, reduced the appeal of vaccination facilities (31, 36). This led to FDMN/Rohingya refugee women preferring to receive vaccinations during household visits (36).

Rights, regulation and legislation related barriers were also found for both caregivers and HSP, though these were less frequently mentioned. Amongst these were restriction of movements and vaccination activities during the COVID-19 pandemic (41), lack of registration (30, 39), and political and resource constraints (38).

Social opportunity barriers and drivers could be subcategorised to social and culture-related norms, and social support.

Socio-cultural barriers were linked to healthcare and gender norms. These related to norms in Myanmar to seek healthcare outside the formal healthcare system (39, 46), or it being common to receive one single vaccination a day, instead of multiple or combination vaccines offered in Cox’s Bazar (36, 37). Gender norm barriers were reported for receiving and facilitating vaccination in three articles (13, 31, 36), corresponding with the aforementioned physical opportunity barrier of having predominantly male vaccinators. These included women and girls not being able to interact or show parts of their body to men outside their family (31, 36), and religious leaders not recommending vaccinations as they disapproved of women and girls being publicly vaccinated by men (36). Accordingly, female vaccinators were described as drivers to facilitate vaccinations for HSP as they had easier access to families and teenage girls (13).

Social support was shown to be a driver for both refugees receiving as well as for HSPs facilitating vaccinations. For FDMN/Rohingya refugees, being able to ask questions to NGO or camp staff (45)—particularly through the use of female vaccinators who could encourage and enable women and girls to speak up—was identified as a driver (13). In contrast, the recent arrival of refugees in registered and makeshift camps was seen as a barrier (16). For HSP, collaborative partnerships and good relationships with the government (13, 44) were identified as drivers. Barriers here included a lack of community engagement to facilitating vaccinations (44).

3.2.3 Assessing differences

All four COM factors were relevant to FDMN/Rohingya refugees, while three COM factors (excluding capability) applied to HSP. For refugees receiving vaccinations, motivation and physical opportunity related barriers and drivers were the most identified, whereas for HSPs facilitating vaccinations, physical opportunity related barriers and drivers were most reported.

Some authors investigated differences between makeshift and registered camps (16, 38, 40), registered and unregistered refugees (39) or different lengths of stay (37), though it was difficult to draw clear conclusions. Lower vaccination rates were generally found in recently arrived, unregistered FDMNs or those living in makeshift camps in comparison to those who had lived there since before 2017 in registered camps (16, 38, 39), explained by registered refugees being more aware of local practices and improved access to health facilities (38, 39). However, Khan et al. found relatively higher coverage of the oral cholera vaccine among people living in camps for 4–6 months compared to people living there for more than 6 months, but no association between vaccination coverage and length of stay for all other vaccines (37). Although we did not look specifically focus on the host community, it is noteworthy that Qayum et al. highlighted higher oral cholera vaccine coverage in the registered and makeshifts camps in comparison to the host community (40). This was attributed to the host community being unaware of the vaccination campaigns, unavailability of vaccines, and unawareness of where vaccines were available (40). Ahmed et al. also investigated other factors associated with good vaccination practices and found higher vaccination rates among families where fathers were employed and where parents had a higher level of education (16).

3.3 Interventions related to childhood vaccinations

Interventions to remove barriers and strengthen drivers to receiving and facilitating childhood vaccination are shown in Table 6. Implemented interventions were identified in 20 articles, described as part of authors’ reflections (4, 30, 32–34), post-campaign vaccination coverage surveys (31, 35, 37–39), reports (13, 41, 42), NGO/ UN response evaluation reports (11, 43, 44, 46) and research studies (16, 36). Just one evaluation study of a vaccination campaign was found (40). Generally, descriptions of interventions were brief and lacked detail, which made separate charting of interventions for different populations and their target behaviours impossible.

Table 6

| Intervention type* | COM-factor addressed* | Intervention |

|---|---|---|

| Information/education |

|

|

| Persuasion |

| |

| Incentivisation |

| / |

| Coercion |

| / |

| Training |

| |

| Restriction |

| / |

| Environmental restructuring |

|

|

| Modelling |

|

Implemented interventions (with and without evaluation) charted by COM-factor and intervention type from the BCW.

Intervention types as per the BCW included mostly environmental restructuring interventions (12 interventions reported by 20 articles), and most frequently involved supplemental (4, 11, 16, 30, 32–34, 37–41, 44, 46) and routine immunisation campaigns (13, 16, 37, 41, 43, 44, 46). Other types of interventions were information/education (seven interventions reported by six articles) (13, 31, 35, 36, 42, 44), modelling (two interventions reported by four articles) (31, 34, 36, 42), with least interventions in the areas of persuasion (one intervention reported by three articles) (31, 34, 42) and training (two interventions reported by three articles) (13, 31, 37). No interventions relating to incentivisation, coercion and restriction were identified. Combining interventions for vaccinations with other measures (e.g., WASH, health education) and intersectoral partnerships were also reported and deemed successful or important (13, 34–37, 39, 42, 44).

We also reviewed the author’s recommendations for possible future interventions. Five articles recommended five interventions (30, 32, 36, 40, 46) for which from the included literature no evidence of their implementation was found. These recommendations were rather broad and included information/education type interventions such as investigating interactions between HSP and caregivers (36), exploring alternative vaccination schedules (46), and providing vaccination cards and medical summaries (30). Correlating with previously mentioned drivers to vaccination uptake, it was recommended to work closely with religious leaders to identify appropriate passages from the Qur’an and Hadith which can be used to support vaccination uptake (31), or encourage the presence of the camp administration during vaccination campaigns to improve efficiency (40). Given the dynamic and evolving conflict situation, some recommendations from older articles were subsequently implemented and reported in more recent articles (see Table 6).

4 Discussion

We reviewed 21 articles that explored barriers, drivers and interventions regarding childhood vaccination behaviours in Cox’s Bazar, guided by the COM-B framework (18) and BCW (24). Only six articles were peer-reviewed primary research, with remaining articles being opinion pieces, grey literature reports/studies and response evaluations. Evidence was available for barriers and drivers to FDMN/Rohingya refugees receiving and HSP facilitating vaccinations. The barriers and drivers were mostly linked to the COM factors of physical opportunity, followed by motivation. Most frequently reported implemented interventions focused on environmental restructuring and information/education. Only one evaluation study of an intervention was found. Below we discuss the scope of, and gaps in the research landscape followed by a brief discussion of key barriers and their implications for interventions.

4.1 Barriers and drivers to childhood vaccination behaviours

The review identified a range of barriers and drivers on both the demand (FDMN/Rohingya refugee) and supply (HSP) side, though more evidence for barriers and drivers for FDMN/Rohingya refugees was found than for HSPs. Barriers and drivers for all four COM factors was described for FDMN/Rohingya refugees receiving vaccinations, whilst for HSPs facilitating vaccinations, three COM factors were found with no articles reporting capability barriers or drivers. Both motivation factors (e.g., fears, trust) and physical opportunity factors (e.g., availability of vaccines) were most reported for FDMN/Rohingya refugees receiving vaccinations, whilst physical opportunity factors (e.g., geographical access, availability of resources) were most reported for HSPs facilitating vaccinations. The less frequent reporting of barriers and drivers for HSPs highlights a need for further exploration of their perspectives in the vaccination efforts, given the well-established and critical role of HSPs in improving vaccination coverage (47–49).

The multiple individual and context influences on childhood vaccination behaviours identified in this review align closely with those reported in the WHO ‘Global Evidence Review on Health and Migration’ (19). Wide-ranging environmental (physical opportunity) barriers for caregivers and HSPs alike are expected in a challenging environment such as Cox’s Bazar, where a lack of infrastructure and resources are an obvious and immediate barrier to service delivery (19, 50). Indeed many of the environmental barriers reflect the six building blocks of the WHO health systems Building Blocks framework (51): (i) service delivery; (ii) health workforce; (iii) information; (iv) medical products, vaccines and technologies; (v) financing; and (vi) leadership and governance. Additionally, motivation related barriers identified may be linked to a lack of vaccine confidence, which is known to be influenced by political and medical mistrust (52–54). For FDMN/Rohingya refugees in particular, this may be associated with persecution and violence experienced in their home country (13, 44). Additionally for many caregivers, Cox’s Bazar provided first time exposure to vaccinations (38, 40, 55), particularly combination vaccines, highlighting knowledge gaps and a lack of confidence. This was further evidenced by increased vaccination rates in those that lived in registered camps and had been in the area for longer (40). Though there was some evidence of increasing trust and confidence in vaccines and vaccinators with time (36), ongoing issues with mistrust—a common phenomenon seen globally—suggest that further modes of trust building may need to be explored (56).

Social norms, social support and community/religious leader engagement have been found to be crucial for effective vaccination programs (57), though only one article explored community/religious leaders recommending vaccinations. Gender norms are likely to be important for a Muslim community where teenage girls and women practice “purdah,” the Islamic practice requiring women to be veiled from public gazes or remain within private spaces of the family (58). Understanding and addressing these leaders’ barriers and drivers may be a potential opportunity for vaccination promotion (31, 59) as they play a central role in trust building for vaccination campaigns (60).

A further evidence gap emerged with regard to different camps and subgroups of FDMN/Rohingya refugees. There was insufficient detail in most studies to identify barriers and drivers that were specific to camps or population subgroups. This is a limitation in the existing literature as treating FDMN/Rohingya refugees as a homogeneous group prevents the development of tailored and targeted interventions (20). It was notable that a few more recent studies did compare FDMN populations in registered and makeshift camps, though further research comparing barriers and drivers for different population groups and different camps would be helpful.

4.2 Interventions

The high number of articles describing implemented interventions with some information on impact is a strength of the literature, and the implemented interventions identified are in line with a global review of interventions to reduce VPD burden amongst migrants and refugees (61). However, the interventions lacked detail on intervention rationale, theoretical underpinning, and target populations or behaviours. Furthermore, evaluating their impact was difficult due to limited descriptions of the intervention’s impact and a lack of formal evaluation studies, and instead reliance on author’s reflections or using single indicators to measure vaccination coverage in many articles. It is therefore difficult to understand if and how these interventions work, and if they should be replicated. This lack of detailed description and evaluation is evident in the wider vaccination (62–64) and public health intervention literature (65, 66). Standardized reporting checklists for interventions (65) and increasing the publication of monitoring and evaluation reports (65, 67) would allow effective interventions to be transferred and scaled up, and increase overall transparency (62, 68, 69).

Interventions to remove barriers and strengthen drivers to childhood vaccination behaviours encompassed five intervention types (18, 24)—mainly environmental restructuring and information/education, less often modelling, persuasion and training—which means that in theory, all COM factors can be addressed (see Table 1). Environmental restructuring interventions reduce the physical and social opportunity and motivation related barriers and strengthen these drivers, whilst education interventions address capability and motivation related barriers and drivers. Overall, the interventions found correlate theoretically with the COM-factors of the most identified barriers and drivers. Those focused on improving the health system, once again align with the WHO health systems Building Blocks framework (51). No article described incentivisation, coercion or restriction interventions, which may offer additional strategies.

The limited available intervention impact data suggests that vaccination campaigns, routine immunisation services, community mobilisation and gender specific interventions may improve vaccination uptake (4, 11, 13, 31, 32, 36, 37, 39, 41–44, 46), aligning with findings of a systematic review (19, 63). Tailored environmental restructuring interventions, such as the provision of female vaccinators and private vaccination areas, were found to address gender specific barriers to vaccination uptake (13, 31), and strengthening these would be in line with the Global Immunization Agenda 2030 which includes gender equity as a strategic priority (70). In addition, collaborating with community leaders may offer alternative, culturally appropriate intervention strategies (31, 71).

4.3 Research landscape

Regarding the research landscape, encouragingly, critical appraisal found the articles themselves to be of moderate to high quality. However, the literature and data were frequently scattered, and difficult to collate as embedded in different parts of articles and described in varying detail. This is in keeping with the known difficulty in humanitarian conflict settings to collate and share information systematically, due to logistical challenges, problematic data collection and a lack of health information sharing mechanisms (72, 73).

4.4 Strengths and limitations

To our knowledge, this is the first scoping review on childhood vaccinations in the Rohingya population. Its strengths include the comprehensive search strategy applying the JBI methodology, and a theory-informed analysis utilising the COM-B model and BCW that are useful in understanding and addressing public health challenges (18, 24). These behaviour frameworks have been extensively applied to childhood and adult vaccination behaviours (74–76) and provide the theoretical underpinning of the WHO Tailoring Immunization Programmes (18). Their use enabled a holistic and systematic examination of individual and context barriers and drivers reported in the literature, avoiding “blind spots” (20), and classification of different types of reported interventions into a well-accepted framework (BCW). In addition, given the scattered evidence base, this review adds value by providing and overarching overview of barriers and drivers. Furthermore, this review provides a nuanced examination of vaccination behaviours related to receiving and facilitating vaccinations, thereby reviewing demand and supply side influences on vaccination coverage and equity outcomes.

However, several limitations should be acknowledged. Despite an extensive search strategy and screening four databases, reference lists, and grey literature sources, further literature may exist. We used the Google Advanced Search function which has a low reproducibility, but it was useful as we found reports which were not displayed on the respective organisation’s websites. This emphasises again the need for improved mechanisms to share and collate evidence. The results may also be affected by publication bias. As mentioned before, especially in conflict settings, frontline organisations and researchers may not have the capacity to publish findings (73). Additionally, even though no language restrictions were set, we only used English search terms and only found English articles. Studies exploring barriers and drivers to health behaviours typically use self-reported accounts and this was evident for most of the included articles. We were unable to clearly differentiate barriers and drivers by the specific type of vaccine or disease such as measles due to limited detail of the data, and it would be useful for future research to investigate this. It is important to recognise that frequency counts were undertaken to describe the range of evidence and identify most reported barriers or drivers. However, frequency of reporting may not correlate with the impact of this barrier or driver, and configuration of the data as a whole is equally important.

A limitation of the BCW is the wide range of interventions captured in the intervention type “environmental restructuring” potentially resulting in vague guidance for appropriate interventions to change the social or physical context. This was sufficient for classifying interventions in our review. However, researchers could usefully employ more specific behaviour change techniques or mechanisms of action (77) to improve the links between barriers and interventions.

5 Conclusion

A wide range of barriers and drivers for FDMN/Rohingya refugees receiving and HSPs facilitating vaccinations in Cox’s Bazar exist, with more barriers and drivers reported from FDMN/Rohingya refugees perspective compared to HSPs perspective. Context and motivation related factors were the most frequently identified barriers and drivers. Salient gender and social norms also played a significant role in influencing both behaviours. However, available data was insufficiently described to assess geographical or subgroup differences within Cox’s Bazar. Encouragingly, several interventions were reported that address these barriers and drivers, though reported interventions lacked detail and the description of their impact and evaluation were very limited. Community and faith leaders play an influential role in Rohingya culture and could be key partners in strengthening vaccination programs and community mobilisation efforts in the future. Overall, this review emphasised the need for further research, particularly on HSP perspectives, subgroups within the Rohingya population, and better reporting, monitoring, and evaluation of interventions to design targeted strategies for increasing vaccination uptake in the Rohingya community in Cox’s Bazar.

Statements

Data availability statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/Supplementary material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Author contributions

ZY: Methodology, Validation, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing, Data curation, Formal analysis, Investigation, Software, Visualization. SR: Data curation, Investigation, Methodology, Validation, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. JH: Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing, Funding acquisition, Resources, Supervision. CJ: Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing, Conceptualization, Formal analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Validation. BC: Investigation, Methodology, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing, Data curation. AJ: Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing, Conceptualization, Funding acquisition, Resources. SL: Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing, Methodology. JM: Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing, Supervision. EM: Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. JN: Methodology, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. AS: Investigation, Methodology, Project administration, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. EW: Methodology, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. MZ: Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. BK: Conceptualization, Funding acquisition, Methodology, Project administration, Resources, Supervision, Validation, Visualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declare that financial support was received for the research and/or publication of this article. This work was supported by the German Federal Ministry of Health (grant number: ZMI1-2521GHP908). The funders had no role in the design, data collection and analysis, or in the decision to write and submit this paper for publication.

Acknowledgments

We acknowledge the FDMN/Rohingya refugees who contributed indirectly to the findings of this review (e.g., by participating in included studies), and everyone involved in the FDMN/Rohingya refugees response in Cox’s Bazar, including the Ministry of Health in Bangladesh, the WHO Emergency Sub-Office in Cox’s Bazar, the WHO Country Office Bangladesh, the office of RRRC and Civil Surgeon Cox’s Bazar and all the organizations who shared their studies and reports.

Conflict of interest

CJ is self-employed with her company being Valid Research Ltd.

The remaining authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The authors declare that no Gen AI was used in the creation of this manuscript.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Supplementary material

The Supplementary material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fpubh.2025.1592452/full#supplementary-material

Footnotes

References

1.

World Health Organization. Global vaccine action plan 2011–2020 (2013). Available online at: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/global-vaccine-action-plan-2011-2020 (Accessed August 16, 2022).

2.

Rojas-VenegasMCano-IbáñezNKhanKS. Vaccination coverage among migrants: A systematic review and meta-analysis. SEMERGEN. (2022) 48:96–105. doi: 10.1016/j.semerg.2021.10.008

3.

CharaniaNAGazeNKungJYBrooksS. Vaccine-preventable diseases and immunisation coverage among migrants and non-migrants worldwide: A scoping review of published literature, 2006 to 2016. Vaccine. (2019) 37:2661–9. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2019.04.001

4.

RahmanMRIslamK. Massive diphtheria outbreak among Rohingya refugees: lessons learnt. J Travel Med. (2019) 26:1–3. doi: 10.1093/jtm/tay122

5.

DahalPKRawalLBKandaKBiswasTTanimMIIslamMRet al. Health problems and utilization of health services among forcibly displaced Myanmar nationals in Bangladesh. Glob Health Res Policy. (2021) 6:39. doi: 10.1186/s41256-021-00223-1

6.

LarsonHJJarrettCEckersbergerESmithDMPatersonP. Understanding vaccine hesitancy around vaccines and vaccination from a global perspective: a systematic review of published literature, 2007-2012. Vaccine. (2014) 32:2150–9. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2014.01.081

7.

TankwanchiASBowmanBGarrisonMLarsonHWiysongeCS. Vaccine hesitancy in migrant communities: a rapid review of latest evidence. Curr Opin Immunol. (2021) 71:62–8. doi: 10.1016/j.coi.2021.05.009

8.

InterSector Coordination Group. Joint response plan Rohingya humanitarian crisis 2022 (2022). Available online at: https://reliefweb.int/report/bangladesh/2022-joint-response-plan-rohingya-humanitarian-crisis-january-december-2022 (Accessed June 1, 2022)

9.

BhatiaAMahmudAFullerAShinRRahmanAShatilTet al. The Rohingya in Cox's Bazar: when the stateless seek refuge. Health Hum Rights. (2018) 20:105–22.

10.

PolonskyJAIveyMMazharMKARahmanZle Polain de WarouxOKaroBet al. Epidemiological, clinical, and public health response characteristics of a large outbreak of diphtheria among the Rohingya population in Cox's Bazar, Bangladesh, 2017 to 2019: A retrospective study. PLoS Med. (2021) 18:e1003587. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1003587

11.

United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees. Independent evaluation of UNHCR’s emergency response to the Rohingya refugees influx in Bangladesh August 2017–2018. (2018). Available online at: https://www.unhcr.org/sites/default/files/legacy-pdf/5c811b464.pdf (Accessed June 15, 2021)

12.

United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees. Operational data portal. Available online at: https://data.unhcr.org/en/country/bgd (Accessed January 8, 2025])

13.

World Health Organzation South East Asia Regional Office. Invisible-the Rohingyas, the crisis, the people and their health (2019). Available online at: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789290227243 (Accessed August 30, 2021])

14.

Rohingya Refugee Response. 2024 joint response plan Rohingya humanitarian crisis (2024). Available online at: https://rohingyaresponse.org/project/2024-jrp/#:~:text=The%202024%20JRP%20requests%20%24852.4,Agencies%2C%20Bangladeshi%20and%20international%20NGOs (Accessed May 10, 2025).

15.

World Health Organization South East Asia Regional Office. Expanded programme on immunization (EPI) factsheet 2024: Bangladesh (2024). Available online at: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/bangladesh-epi-factsheet-2024 (Accessed May 10, 2025).

16.

AhmedNIshtiakASMRozarsMFKBonnaASAlamKMPHossanMEet al. Factors associated with low childhood immunization coverage among Rohingya refugee parents in Cox's Bazar, Bangladesh. PLoS One. (2023) 18:e0283881. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0283881

17.

ChinTBuckeeCOMahmudAS. Quantifying the success of measles vaccination campaigns in the Rohingya refugee camps. Epidemics. (2020) 30:100385. doi: 10.1016/j.epidem.2020.100385

18.

World Health Organization. Tip: tailoring immunization programmes (2019). Available online at: https://www.who.int/europe/publications/i/item/9789289054492 (Accessed May 10, 2021)

19.

World Health Organization. Ensuring the integration of refugees and migrants in immuniztion policies, planning and service delivery globally (2022). Available online at: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789240051843 (Accessed July 15, 2022)

20.

HabersaatKBJacksonC. Understanding vaccine acceptance and demand-and ways to increase them. Bundesgesundheitsblatt Gesundheitsforschung Gesundheitsschutz. (2020) 63:32–9. doi: 10.1007/s00103-019-03063-0

21.

PetersMDJGodfreyCMcInerneyPBaldini SoaresCKhalilHParkerD. Chapter 11: scoping reviews In: AromatarisEMunnZ, editors. JBI manual for evidence synthesis. Johanna Briggs Institute. (2020)

22.

ArkseyHO'MalleyL. Scoping studies: towards a methodological framework. Int J Soc Res Methodol. (2005) 8:19–32. doi: 10.1080/1364557032000119616

23.

TriccoALillieEZarinWO'BrienKColquhounHLevacDet al. PRISMA extension for scoping reviews (PRISMA-ScR): checklist and explanation. Ann Intern Med. (2018) 169:467–73. doi: 10.7326/M18-0850

24.

MichieSVan StrahlenMMWestR. The behaviour change wheel: a new method for characterising and designing behaviour change interventions. Implement Sci. (2011) 6:1–11. doi: 10.1186/1748-5908-6-42

25.

OuzzaniMHammadyHFedorowiczZElmagarmidA. Rayyan-a web and mobile app for systematic reviews. Syst Rev. (2016) 5:210. doi: 10.1186/s13643-016-0384-4

26.

Barnett-PageEThomasJ. Methods for the synthesis of qualitative research: a critical review. BMC Med Res Methodol. (2009) 9:59. doi: 10.1186/1471-2288-9-59

27.

HongQNPluyePFàbreguesSBartlettGBoardmanFCargoMet al Mixed methods appraisal tool (MMAT) user guide version 2018. McGill Department of Family Medicine; (2018).

28.

TyndallJ. Aacods checklist Flinders University (2010). Available online at: http://dspace.flinders.edu.au/dspace/ (Accessed July 7, 2022)

29.

McArthurAKlugarovaJYanHFlorescuS. Innovations in the systematic review of text and opinion. Int J Evid Based Healthc. (2015) 13:188–95. doi: 10.1097/XEB.0000000000000060

30.

ChanEYYChiuCPChanGKW. Medical and health risks associated with communicable diseases of Rohingya refugees in Bangladesh 2017. Int J Infect Dis. (2018) 68:39–43. doi: 10.1016/j.ijid.2018.01.001

31.

JallohMFWilhelmEAbadNPrybylskiD. Mobilize to vaccinate: lessons learned from social mobilization for immunization in low and middle-income countries. Hum Vaccin Immunother. (2020) 16:1208–14. doi: 10.1080/21645515.2019.1661206

32.

HsanKMamunMAMistiJMGozalDGriffithsMD. Diphtheria outbreak among the Rohingya refugees in Bangladesh: what strategies should be utilized for prevention and control?Travel Med Infect Dis. (2020) 34:101591. doi: 10.1016/j.tmaid.2020.101591

33.

HsanKNaherSGozalDGriffithsMDFurkan SiddiqueMR. Varicella outbreak among the Rohingya refugees in Bangladesh: lessons learned and potential prevention strategies. Travel Med Infect Dis. (2019) 31:101465. doi: 10.1016/j.tmaid.2019.101465

34.

QadriFAzadAKFloraMSKhanAIIslamMTNairGBet al. Emergency deployment of oral cholera vaccine for the Rohingya in Bangladesh. Lancet (London, England). (2018) 391:1877–9. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(18)30993-0

35.

KhanAIIslamMTKhanZHTanvirNAAminMAKhanIIet al. Implementation and delivery of oral cholera vaccination campaigns in humanitarian crisis settings among Rohingya Myanmar nationals in Cox's Bazar, Bangladesh. Vaccines (Basel). (2023) 11:1–10. doi: 10.3390/vaccines11040843

36.

JallohMFBennettSDAlamDKoutaPLourencoDAlamgirMet al. Rapid behavioral assessment of barriers and opportunities to improve vaccination coverage among displaced Rohingyas in Bangladesh, January 2018. Vaccine. (2019) 37:833–8. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2018.12.042

37.

KhanAIIslamMTSiddiqueSAAhmedSSheikhNSiddikAUet al. Post-vaccination campaign coverage evaluation of oral cholera vaccine, oral polio vaccine and measles-rubella vaccine among forcibly displaced Myanmar nationals in Bangladesh. Hum Vaccin Immunother. (2019) 15:2882–6. doi: 10.1080/21645515.2019.1616502

38.

FeldsteinLRBennettSDEstivarizCFCooleyGMWeilLBillahMMet al. Vaccination coverage survey and seroprevalence among forcibly displaced Rohingya children, Cox's Bazar, Bangladesh, 2018: A cross-sectional study. PLoS Med. (2020) 17:e1003071. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1003071

39.

SummersAHumphreysALeidmanEMilLTvWilkinsonCNarayanAet al. Diarrhea and acute respiratory infection, oral cholera vaccination coverage, and care-seeking behaviors of Rohingya refugees – Cox's Bazar, Bangladesh, October-November 2017. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep (2018); 67: 533–535. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm6718a6

40.

QayumMOBillahMMSarkerMFRAlamgirASMNurunnaharMKhanMHet al. Oral cholera vaccine coverage evaluation survey: forcibly displaced Myanmar nationals and host community in Cox's Bazar, Bangladesh. Front Public Health. (2023) 11:1147563. doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2023.1147563

41.

United Nations Children's Fund. Bangladesh humanitarian situation report no. 55 end of the year 2020 (2020). Available online at: https://www.unicef.org/documents/bangladesh-humanitarian-situation-report-end-year-2020 (Accessed August 30, 2021)

42.

Bangladesh Health Watch. Humanitarian crisis in Rohingya camps a health perspective 2018–2019. (2019). Available online at: https://app.bangladeshhealthwatch.org/docs/reports_pdf/bhw-reports/bangladesh-health-watch-report-2018-2019-1643129470.pdf (Accessed August 30, 2021)

43.

Red R India. Integrated emergency humanitarian response to the Rohingya population in Cox’s Bazar-endline evaluation report (2018). Available online at: https://admin.concern.net/sites/default/files/documents/2020-09/Bangladesh%20ENDLINE%20EVALUATION%20REPORT%20.pdf (Accessed August 30, 2021])

44.

United Nations Children's Fund. Evaluation of UNICEF's response to the Rohingya refugee crisis in Bangladesh (2018). Available online at: https://www.unevaluation.org/member_publications/evaluation-unicefs-response-rohingya-refugee-crisis-bangladesh (Accessed August 30, 2021)

45.

BBC Media Action, Translators without Borders. What-matters-humanitarian feedback-bulletin spread of misinformation in the Rohingya camps (2019). Available online at: https://translatorswithoutborders.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/11/What-Matters-Humanitarian-Feedback-Bulletin_Issue_30_English.pdf (Accessed August 30, 2021)

46.

NasarKSAkhterIKhaledNHossainMRMajidTTamannaSet al Health care needs and health seeking behaviour among Rohingya refugees in Cox’s Bazar: study in selected camps served by BRAC’s health care facilities (2019). Available online at: https://bracjpgsph.org/assets/pdf/research/research-reports/Health-Care-Needs-and-Health_October-2019.pdf (Accessed August 30, 2021)

47.

Julie LeaskPKJacksonCCheaterFBedfordHRowlesG. Communicating with parents about vaccination: a framework for health professionals. BMC Pediatr. (2012) 12:1–11. doi: 10.1186/1471-2431-12-154

48.

KaufmanJRyanRWalshLHoreyDLeaskJRobinsonPet al. Face-to-face interventions for informing or educating parents about early childhood vaccination. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. (2018) 5:CD010038. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD010038.pub3

49.

DubéELeaskJWolffBHicklerBBalabanVHoseinEet al. The WHO tailoring immunization programmes (TIP) approach: review of implementation to date. Vaccine. (2018) 36:1509–15. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2017.12.012

50.

GrundyJBiggsBA. The impact of conflict on immunisation coverage in 16 countries. Int J Health Policy Manag. (2019) 8:211–21. doi: 10.15171/ijhpm.2018.127

51.

World Health Organization. Everybody's business – strengthening health systems to improve health outcomes (2007). Available online at: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/everybody-s-business----strengthening-health-systems-to-improve-health-outcomes (Accessed May 16, 2025)

52.

de FigueiredoASimasCKarafillakisEPatersonPLarsonHJ. Mapping global trends in vaccine confidence and investigating barriers to vaccine uptake: a large-scale retrospective temporal modelling study. Lancet. (2020) 396:898–908. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)31558-0

53.

PertweeESimasCLarsonHJ. An epidemic of uncertainty: rumors, conspiracy theories and vaccine hesitancy. Nat Med. (2022) 28:456–9. doi: 10.1038/s41591-022-01728-z

54.

Godoy-RamirezKBystromELindstrandAButlerRAscherHKulaneA. Exploring childhood immunization among undocumented migrants in Sweden - following qualitative study and the World Health Organizations guide to Tailoring Immunization Programmes (TIP). Public Health. (2019) 171:97–105. doi: 10.1016/j.puhe.2019.04.008

55.

EstivarizCFBennettSDLicknessJSFeldsteinLRWeldonWCLeidmanEet al. Assessment of immunity to polio among Rohingya children in Cox's Bazar, Bangladesh, 2018: a cross-sectional survey. PLoS Med. (2020) 17:e1003070. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1003070

56.

LarsonHJSahinovicIBalakrishnanMRSimasC. Vaccine safety in the next decade: why we need new modes of trust building. BMJ Glob Health. (2021) 6:1–5. doi: 10.1136/bmjgh-2020-003908

57.

Oyo-ItaABosch-CapblanchXRossAOkuAEsuEAmehSet al. Effects of engaging communities in decision-making and action through traditional and religious leaders on vaccination coverage in Cross River state, Nigeria: a cluster-randomised control trial. PLoS One. (2021) 16:e0248236. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0248236

58.

CoyleDJainulMASandberg PetterssonMS. Aarar Dilor Hota. Voices of Our Hearts Honour in Transition: Changing gender norms among the Rohingya. UN Women (2020). Available online at: https://asiapacific.unwomen.org/sites/default/files/Field%20Office%20ESEAsia/Docs/Publications/2020/06/Honour%20in%20Transition-reduced.pdf (Accessed August 25, 2022)

59.

ZarocostasJ. UNICEF taps religious leaders in vaccination push. Lancet. (2004) 363:1709. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(04)16294-6

60.

OzawaSPainaLQiuM. Exploring pathways for building trust in vaccination and strengthening health system resilience. BMC Health Serv Res. (2016) 16:639. doi: 10.1186/s12913-016-1867-7

61.

CharaniaNAGazeNKungJYBrooksS. Interventions to reduce the burden of vaccine-preventable diseases among migrants and refugees worldwide: A scoping review of published literature, 2006-2018. Vaccine. (2020) 38:7217–25. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2020.09.054

62.

MarzoukMOmarMSirisonKAnanthakrishnanADurrance-BagaleAPheerapanyawaranunCet al. Monitoring and evaluation of National Vaccination Implementation: A scoping review of how frameworks and indicators are used in the public health literature. Vaccines (Basel). (2022) 10:1–8. doi: 10.3390/vaccines10040567

63.

JarrettCWilsonRO'LearyMEckersbergerELarsonHJSAGE Working Group on Vaccine Hesitancy. Strategies for addressing vaccine hesitancy – a systematic review. Vaccine. (2015) 33:4180–90. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2015.04.040

64.

DubéEGagnonDMacDonaldNEEskolaJLiangXChaudhuriMet al. Strategies intended to address vaccine hesitancy: review of published reviews. Vaccine. (2015) 33:4191–203. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2015.04.041

65.

HoffmannTCGlasziouPPBoutronIMilneRPereraRMoherDet al. Better reporting of interventions: template for intervention description and replication (TIDier) checklist and guide. BMJ. (2014) 348:g1687. doi: 10.1136/bmj.g1687

66.

GlasziouPMeatsEHeneghanCShepperdS. What is missing from descriptions of treatment in trials and reviews?BMJ. (2008) 336:1472–4. doi: 10.1136/bmj.39590.732037.47

67.

NutlandWWigginsM. Monitoring and evaluating health promotion interventions and programmes In: NutlandWCraigL, editors. Health promotion practice. Maidenhead, UK and New York, NY: McGraw Hill Education/Open University Press (2015)

68.

Global Alliance for Vaccines and Immunization. Monitoring and evaluation framework strategy-2016-2020 (2017). Available online at: https://www.gavi.org/sites/default/files/document/gavi-monitoring-and-evaluation-framework-and-strategy-2016-2020pdf.pdf (Accessed August 25, 2022)

69.

SodhaSVDietzV. Strengthening routine immunization systems to improve global vaccination coverage. Br Med Bull. (2015) 113:5–14. doi: 10.1093/bmb/ldv001

70.

World Health Organization. Immunization agenda 2030, strategic priorities, gender and equity (2020). Available online at:https://www.immunizationagenda2030.org/strategic-priorities/coverage-equity (Accessed August 25, 2022)

71.

World Health Organization. Immunization agenda 2030, strategic priorities, outbreaks and emergencies (2020). Available online at: https://www.immunizationagenda2030.org/strategic-priorities/outbreaks-emergencies (Accessed August 25, 2022)

72.

KohrtBAMistryASAnandNBeecroftBNuwayhidI. Health research in humanitarian crises: an urgent global imperative. BMJ Glob Health. (2019) 4:e001870. doi: 10.1136/bmjgh-2019-001870

73.

NairSAttal-JuncquaAReddyASorrellEMStandleyCJ. Assessing barriers, opportunities and future directions in health information sharing in humanitarian contexts: a mixed-method study. BMJ Open. (2022) 12:e053042. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2021-053042

74.

JacksonCSmithSAghasaryanAAndreasyanDAregayAKHabersaatKBet al. Barriers and drivers of positive COVID-19 vaccination behaviours among healthcare workers in Europe and Central Asia: a qualitative cross-country synthesis. Humanit Soc Sci Commun. (2023) 10:1–15. doi: 10.1057/s41599-023-02443-x

75.

GauldNMartinSSinclairOPetousis-HarrisHDumbleFGrantCC. Influences on pregnant women's and health care professionals' behaviour regarding maternal vaccinations: A qualitative interview study. Vaccines (Basel). (2022) 10:1–10. doi: 10.3390/vaccines10010076

76.

CarlsonSJTomkinsonSHannahAAttwellK. What happens at two? Immunisation stakeholders' perspectives on factors influencing sub-optimal childhood vaccine uptake for toddlers in regional and remote Western Australia. BMC Health Serv Res. (2024) 24:968. doi: 10.1186/s12913-024-11371-8

77.

CareyRNConnellLEJohnstonMRothmanAJde BruinMKellyMPet al. Behavior change techniques and their mechanisms of action: A synthesis of links described in published intervention literature. Ann Behav Med. (2019) 53:693–707. doi: 10.1093/abm/kay078

Summary

Keywords

Rohingya, Forcibly Displaced Myanmar Nationals/Rohingya refugees, childhood, vaccination, Cox’s Bazar, review

Citation

Yusuf Z, Reda S, Hanefeld J, Jackson C, Chawla BS, Jansen A, Lange S, Martinez J, Meyer ED, Neufeind J, Singh AS, Wulkotte E, Zaman MS and Karo B (2025) Barriers and drivers to childhood vaccinations in Forcibly Displaced Myanmar Nationals (FDMN)/Rohingya refugees in Cox’s Bazar, Bangladesh: a scoping review. Front. Public Health 13:1592452. doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2025.1592452

Received

12 March 2025

Accepted

18 June 2025

Published

18 July 2025

Volume

13 - 2025

Edited by

Andrea Haekyung Haselbeck, Prevent Infect GmbH, Germany

Reviewed by

Mselenge Hamaton Mdegela, University of Greenwich, United Kingdom

Ibrahim Dadari, United Nations Children’s Fund, NYHQ, United States

Updates

Copyright

© 2025 Yusuf, Reda, Hanefeld, Jackson, Chawla, Jansen, Lange, Martinez, Meyer, Neufeind, Singh, Wulkotte, Zaman and Karo.

This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Basel Karo, karob@rki.de

Disclaimer

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.