- 1Department of Health Administration and Hospitals, College of Public Health and Health Informatics, Umm Al Qura University, Makkah, Saudi Arabia

- 2General Directorate of Research and Studies, Ministry of Health, Riyadh, Saudi Arabia

- 3Department of Preventive Dental Sciences, College of Dentistry, Princess Nourah Bint Abdulrahman University, Riyadh, Saudi Arabia

- 4Department of Family and Community Medicine, College of Medicine, Taibah University, Madinah, Saudi Arabia

- 5Department of Respiratory Therapy, College of Applied Medical Sciences, King Saud bin Abdulaziz University for Health Sciences, Riyadh, Saudi Arabia

- 6King Abdullah International Medical Research Center, Riyadh, Saudi Arabia

- 7Department of Respiratory Services, King Abdulaziz Medical City, Ministry of National Guard Health Affairs, Riyadh, Saudi Arabia

- 8Department of Public Health and Community Medicine, Faculty of Medicine, Menoufia University, Shebin El Kom, Egypt

- 9Department of Preventive Dental Sciences, College of Dentistry, Jazan University, Jazan, Saudi Arabia

- 10Tobacco Control Program, Ministry of Health, Riyadh, Saudi Arabia

Introduction: Tobacco use is a major global public health challenge, causing millions of deaths annually. In Saudi Arabia, increasing adult smoking rates highlight the need for improved tobacco control measures.

Aim: This study examined trends in tobacco use among youth in Saudi Arabia from 2007 to 2022, evaluating shifts in the determinants of tobacco use and the effectiveness of control measures over time.

Methods: We analyzed three waves of the Global Youth Tobacco Survey (GYTS) conducted in Saudi Arabia (2007, n = 2,574; 2010, n = 1,797; 2022, n = 5,610). The GYTS uses a two-stage cluster sampling design to select students aged 13–15 from intermediate schools, with a focus on tobacco use trends and related behaviors.

Results: This study revealed a substantial decline in current tobacco product usage, dropping significantly from 15.9% in 2007 to 9.4% in 2022 (B = −0.44, p = 0.030), and a decrease in exposure to second-hand smoke from 27.9% in 2007 to 18.1% in 2022. However, the proportion of individuals aged 7 years or younger who initiated cigarette smoking rose from 9.1% in 2007 to 17.1% in 2022. There was a 6.4% increase among female youth who thought that smoking made people feel comfortable across this time period (B = 0.55, p = 0.033), and this population demonstrated a significant decrease in the intention to quit smoking from 65.7 to 52.2% (B = −0.895, p = 0.010).

Conclusion: Although overall tobacco use decreased, alarming trends, emerged, such as earlier smoking initiation and declining intentions to quit among females. Future interventions should focus on preventing early tobacco use initiation by addressing misconceptions, promoting cessation, and enforcing restrictions on youth access to tobacco products.

1 Introduction

1.1 Tobacco use in Saudi Arabia

The burden of tobacco use remains a significant global public health challenge, causing over 8 million deaths annually, primarily in low- and middle-income countries (1). In Saudi Arabia, the prevalence of current smoking among adults was approximately 12% in 2013 (2). By 2018, data from the Saudi Food and Drug Authority (SFDA) indicated an increased prevalence of smoking, with 21% of adults reporting current smoking (3). In 2019, the Global Adult Tobacco Survey (GATS) revealed that the prevalence of tobacco use among adults aged 15 years and above in Saudi Arabia reached 19%, with a higher prevalence among men (30%) than among women (4%). The survey also revealed that the average age of daily smoking initiation is 18 years (4). These factors position tobacco control as a critical public health priority in Saudi Arabia, particularly given that smoking is responsible for an estimated 70,000 deaths annually (5).

1.2 Youth and tobacco use in Saudi Arabia

Youth is considered the largest segment of the population in Saudi Arabia (6). Maintaining a healthy status for youth is essential to reduce the risk of many preventable chronic diseases, particularly those related to tobacco use, such as hypertension, cardiovascular diseases, and cancers (7). In Saudi Arabia, the prevalence of hypertension is greater than that in other Arab countries (8), and there is a specific increasing trend of cardiovascular disease among youth (9). In addition, the tobacco industry has historically employed aggressive marketing strategies targeting adolescents, referring to them as “replacement smokers” (10, 11). In Saudi Arabia, approximately 15% of adolescents reported using tobacco in 2010 (12). A systematic review of studies published between 2007 and 2018 revealed that the prevalence of tobacco smoking among adolescents in Saudi Arabia ranged from 12.7 to 39.6% (13). These data indicate a wide range of prevalence rates attributable to various sampling methodologies employed across the included studies.

Furthermore, several studies have demonstrated similar variations in cigarette smoking prevalence according to region and sex (2, 12–14). One 2025 article revealed that the prevalence of youth who had ever used e-cigarettes in Saudi Arabia was 14.2% (15). Despite the implementation of educational programs and anti-tobacco campaigns, younger individuals continue to use tobacco (16).

1.3 Tobacco control efforts in Saudi Arabia

The Saudi Ministry of Health (MOH) launched a national tobacco control program following Saudi Arabia’s ratification of the World Health Organization (WHO) Framework Convention on Tobacco Control (FCTC) in 2005 (5, 17). Efforts to combat smoking began in the early 2000s. In 2009, the Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC) Standardization Organization (GSO) introduced a technical regulation that included provisions for limits on cigarette emissions, such as tar, nicotine, and carbon monoxide (18). This was followed in 2011 by GSO regulations mandating labeling requirements for tobacco product packaging (19). That same year, the MOH established specialized tobacco cessation clinics to support individuals seeking to quit smoking (12). Between 2012 and 2022, the government adopted more aggressive measures to control tobacco use (20). In 2015, Royal Decree No. 56 introduced the Anti-Smoking Law, a comprehensive framework for tobacco control in Saudi Arabia. The law imposed restrictions on smoking in public places, limited tobacco advertising, promotion, and sponsorship, and set requirements for health warnings on tobacco packaging (21). Additional measures followed, including a substantial 100% increase in tobacco taxes, an expansion of the smoking ban to include public establishments and restaurants, and the implementation of penalties for violations of smoking regulations.

Furthermore, the MOH ensures better access to high-quality treatment and preventive services; thus, it has collaborated with the Ministries of Education, Transportation, Interior Affairs, and the SFDA. The MOH has also launched several anti-smoking campaigns through mass media and social media platforms, aiming to raise awareness about the dangers of smoking (20). To support individuals who wish to quit, various smoking cessation services, including free treatment programs and the “937” Smoking Cessation Help Service hotline, have been established for citizens, residents, and visitors in the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia (22). In 2018, the SFDA issued a circular to tobacco product importers, mandating compliance with plain packaging regulations for tobacco products (20). By 2019, these services were made widely accessible through a network of 274 hospital-based clinics, 321 primary healthcare centers, 890 fixed smoking cessation clinics, 100 mobile cessation clinics, 283 home care services, and 14 specialized hospitals (12).

Although Saudi Arabia was recognized by the World Health Organization (WHO) in 2018 as one of 23 “best practice” countries for its exemplary efforts in providing effective tobacco dependence treatment (23), systematically tracking cigarette smoking prevalence since the implementation of these regulations has remained critically important. Despite increasing concerns about adolescent smoking in Saudi Arabia, comprehensive national-level evidence to fully understand its prevalence and associated factors is lacking.

Monitoring smoking trends over time is essential for informing public health policies and designing effective interventions, enabling the development of targeted strategies to prevent smoking initiation and reduce overall prevalence. Furthermore, these insights are crucial for optimizing resource allocation to address tobacco-related health challenges. The lack of a nationally representative tobacco survey in the past has limited the ability to analyze trends over time. Saudi Arabia conducted two waves of the Global Youth Tobacco Survey (GYTS), a nationally representative survey, in 2007 and 2010; however, these surveys were undertaken prior to the ratification of the FCTC (24). The recent administration of the GYTS by the Saudi MOH in 2022 presents an opportunity to assess tobacco trends in Saudi Arabia and examine whether tobacco-related health risks have changed over time. Such analyses could provide a better estimate of the current and future health burden of tobacco use, including its contribution to chronic diseases and its economic impact on the healthcare system. Therefore, this study investigated trends in tobacco use among youth in Saudi Arabia from 2007 to 2022 and evaluated whether the determinants of tobacco use and control have evolved over time.

2 Methodology

2.1 Study design and data source

This study employed an observational, cross-sectional design. GYTS data, which are nationally representative, were utilized. The GYTS is a cross-sectional, school-based survey of grade 1–3 intermediate school students (typically aged 13–15 years). In Saudi Arabia, the GYTS was conducted in 2007, 2010, and 2022. Three waves of the GYTS were included in this study. GYTS data from two waves (2007 and 2010) are publicly available,1 whereas 2022 GYTS data were obtained with permission from the Ministry of Health in Saudi Arabia (IRB log No: 23–106 M).

2.2 Study tool

The GYTS, a component of the Global Tobacco Surveillance System (GTSS), is a global standard for systematically monitoring youth tobacco use and tracking key indicators of tobacco control. The survey uses a standard core questionnaire, sample design, and data collection protocol. The questionnaire is self-administered via scannable paper-based bubble sheets. The questionnaire covers the following topics: tobacco use, cessation, second-hand smoke (SHS), pro- and anti-tobacco advertising and promotion, access to and availability of tobacco products, and knowledge and attitudes regarding tobacco use. Demographic data, including age, sex, income, and residency, were also collected.

2.3 Sampling technique

The GYTS employs a global standardized methodology that incorporates a two-stage sample design, where schools are selected with probability proportional to their enrollment size. The classes within the selected schools were chosen randomly, and all the students in the selected classes were eligible to participate in the survey. A two-stage cluster sample design was used to produce a representative sample of the students.

School Level—The first-stage sampling frame included all schools with 1st–3rd-grade intermediate classes of 40 or more students (mainly aged 13–15 years). Schools were selected with a probability proportional to the school enrollment size.

Class Level—The second sampling stage involved systematic, equal-probability sampling (with a random start) of classes from each participating school. All classes in the selected schools were included in the sampling frame. All the students in the selected classes were eligible to participate in the survey.

2.4 Study inclusion/exclusion criteria

The GYTS was conducted by the Saudi Arabia MOH in 2007, 2010, and 2022. All GYTS waves were included in this study. Male and female students aged 13–15 years were considered.

2.5 Analysis

Various personal characteristics, including demographic, intra- and interpersonal, environmental, and social factors, were analyzed. Additionally, variables related to tobacco control policies, which included smoke-free policies, restrictions on tobacco advertisements, awareness-raising initiatives, and measures to prevent minors from accessing tobacco, among others, were examined. Appendix 1 presents the key questions considered in the study.

Variables similar across the three studies were integrated into a single dataset for analysis. During data management and cleaning, some variables were recoded to standardize them across the 3 years, aiming to simplify the analysis and interpretation. Subsequently, descriptive and linear regression analyses were performed to determine the rate of change over time (independent variable) while controlling for confounding factors, including age, sex, and grade level. The dependent variables across the analyses were categorized into the following domains: (A) tobacco prevalence; (B) age of smoking initiation; (C) exposure to second-hand smoke; (D) exposure to marketing activities; (E) tobacco-related attitudes, perceptions, and knowledge; and (F) intention to quit smoking (Appendix 1). Detailed information is provided regarding the chosen variables within each domain. The analyses were conducted using IBM SPSS Statistics 27 software.

3 Results

3.1 Study population characteristics

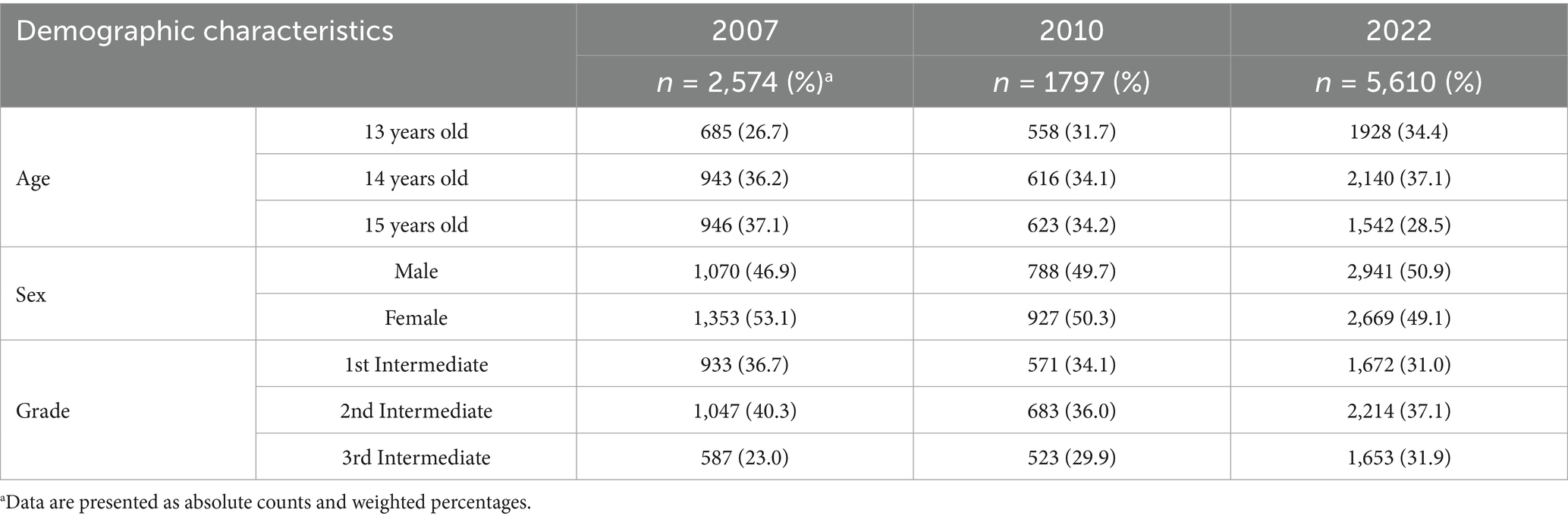

The data from GYTS surveys conducted in 2007 (n = 2,574), 2010 (n = 1,797), and 2022 (n = 5,610) were analyzed. As presented in Table 1, the age distribution across surveys showed slight variation, with the 2022 survey having a greater proportion of 13-year-olds (34.4%) than the 2007 (26.7%) and 2010 (31.7%) surveys. The sex distribution remained relatively balanced across all three surveys, with male participation ranging from 46.9 to 50.9%. Most of the participants were enrolled in the 1st–3rd intermediate grades, with the 2nd intermediate grade consistently representing the largest proportion of students (37.1–40.3%).

3.2 Trends in tobacco use prevalence and age of smoking initiation

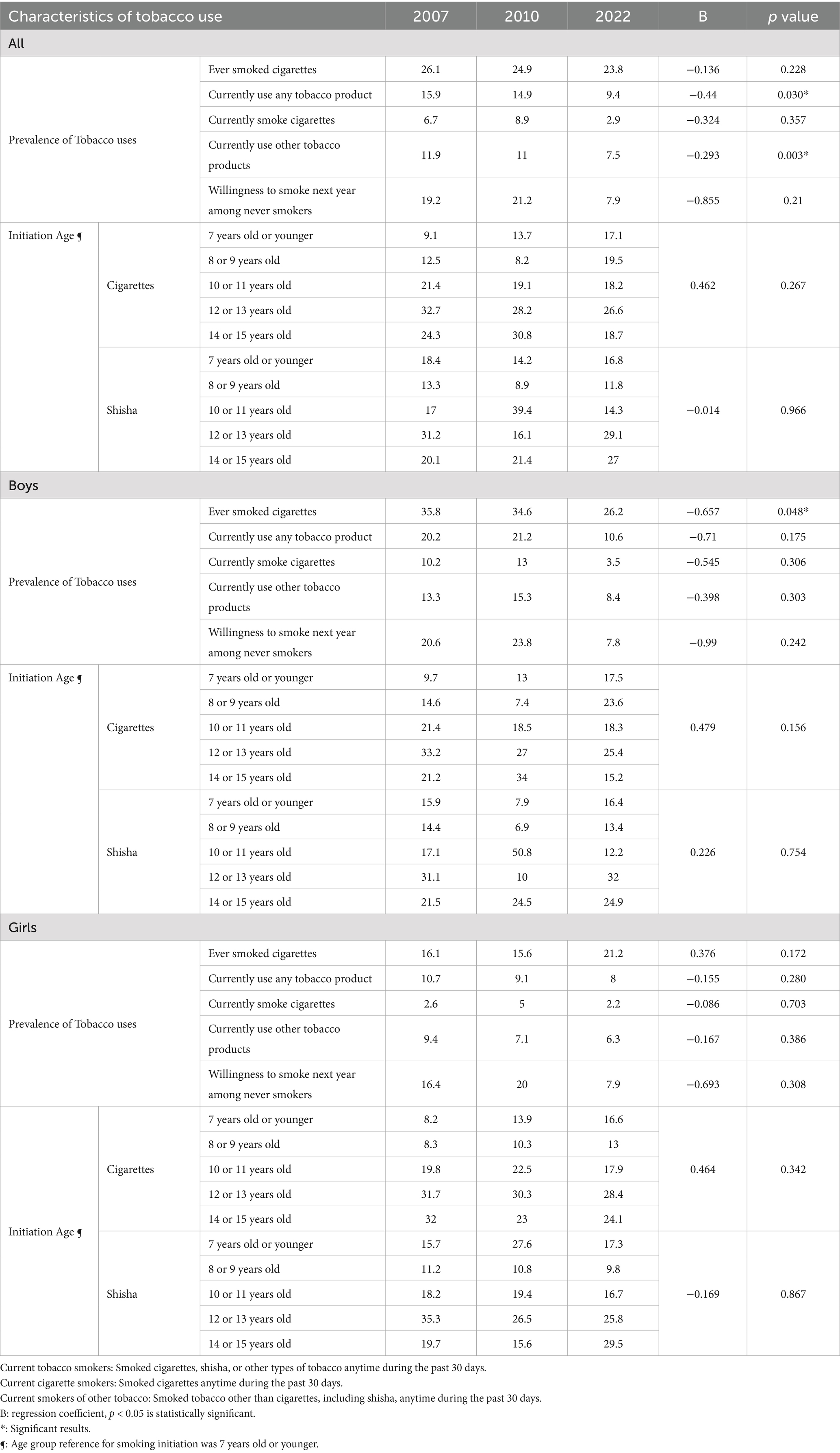

The analysis of tobacco use behaviors revealed several significant trends between 2007 and 2022 (Table 2). The prevalence of current tobacco product use significantly decreased by 6.5% (B = −0.44, p = 0.030), declining from 15.9% in 2007 to 9.4% in 2022. Similarly, the use of other tobacco products demonstrated a significant reduction of 4.4% (B = −0.293, p = 0.003), dropping from 11.9 to 7.5% over the study period. Sex-specific analysis revealed that boys experienced a significant decrease in ever-smoking cigarettes, with a 9.6% decrease (B = −0.657, p = 0.048), resulting in a decline in prevalence from 35.8% in 2007 to 26.2% in 2022. Girls showed no significant trend in ever smoking cigarettes; however, the prevalence increased slightly, albeit not significantly, rising by 5.2% from 16.1% in 2007 to 21.2% in 2022 (B = 0.376, p = 0.172). Current cigarette smoking rates notably decreased across both genders, dropping by 3.8 percentage points from 6.7% in 2007 to 2.9% in 2022. The intention to initiate smoking among never smokers decreased substantially from 19.2% in 2007 to 7.9% in 2022, a change of 11.3 percentage points. Although findings related to the age of smoking initiation were not significant, they showed concerning trends, with an increase in early initiation (Table 2). The proportion of students who started smoking cigarettes at the age of 7 or younger increased by 8%, from 9.1% in 2007 to 17.1% in 2022. Similar patterns were observed for shisha use, with substantial proportions initiating use at young ages across all survey years.

Table 2. Trends in tobacco use prevalence and age of smoking initiation among Saudi adolescents by gender, 2007–2022.

3.3 Exposure to secondhand smoke and tobacco marketing activities

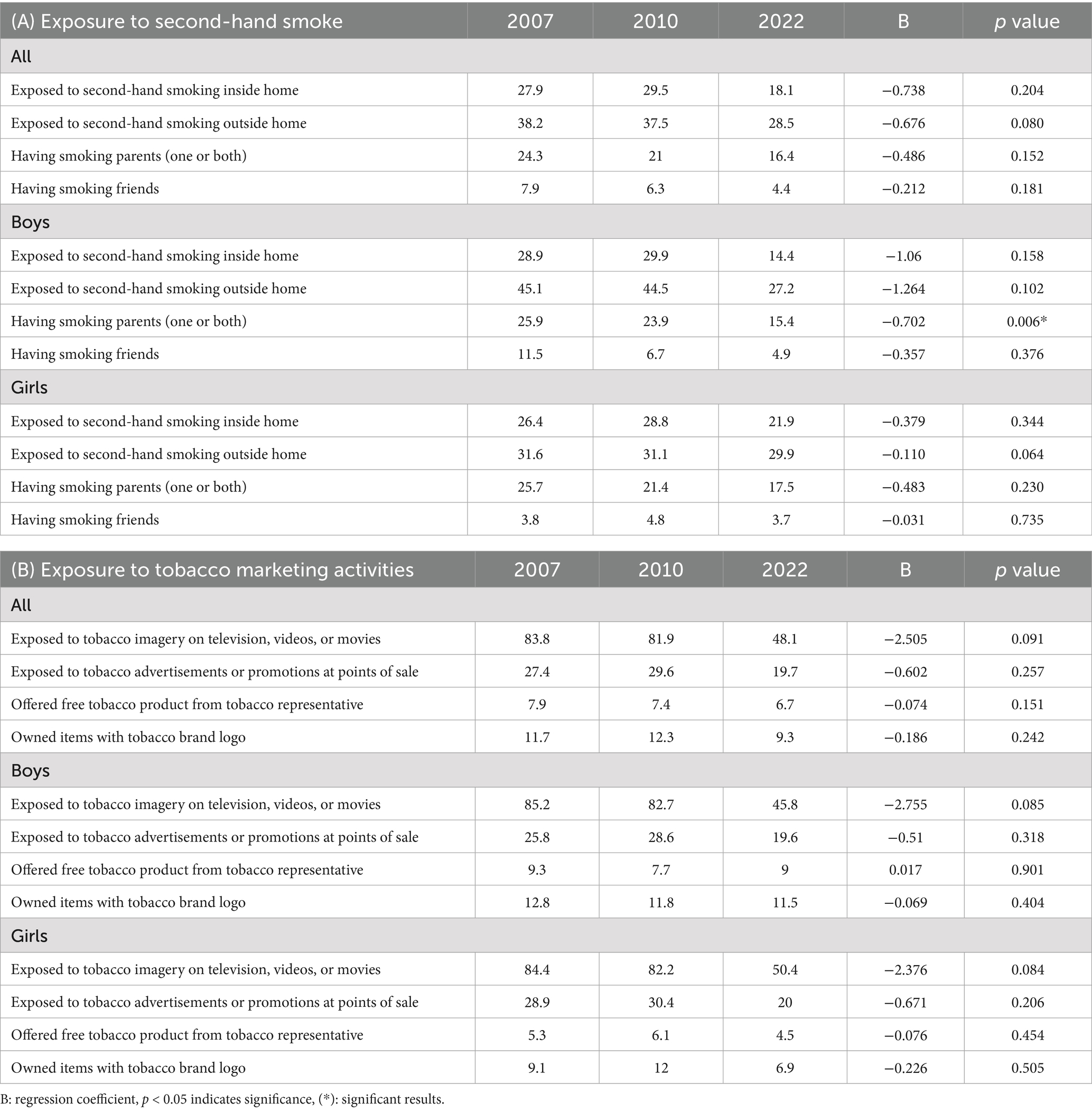

Exposure to second-hand smoke tended to decrease across all measured indicators (Table 3). The percentage of students living in homes where others smoke decreased by 9.8%, from 27.9% in 2007 to 18.1% in 2022. Notably, the percentage of boys with one or more parents who smoked significantly decreased by 10.5% from 25.9 to 15.4% (B = −0.702, p = 0.006). Exposure to smoke outside the home also decreased by 9.7%, from 38.2 to 28.5%, over the study period. Moreover, exposure to tobacco marketing activities such as advertisements and promotions showed a declining trend, with the percentage of students who reported seeing tobacco use in the media decreasing by 35.7%, from 83.8 to 48.1% (Table 3).

Table 3. Changes in exposure to second-hand smoke and marketing activities among Saudi adolescents by gender and setting, 2007–2022.

3.4 Tobacco-related attitudes, perceptions, knowledge, and intention to quit

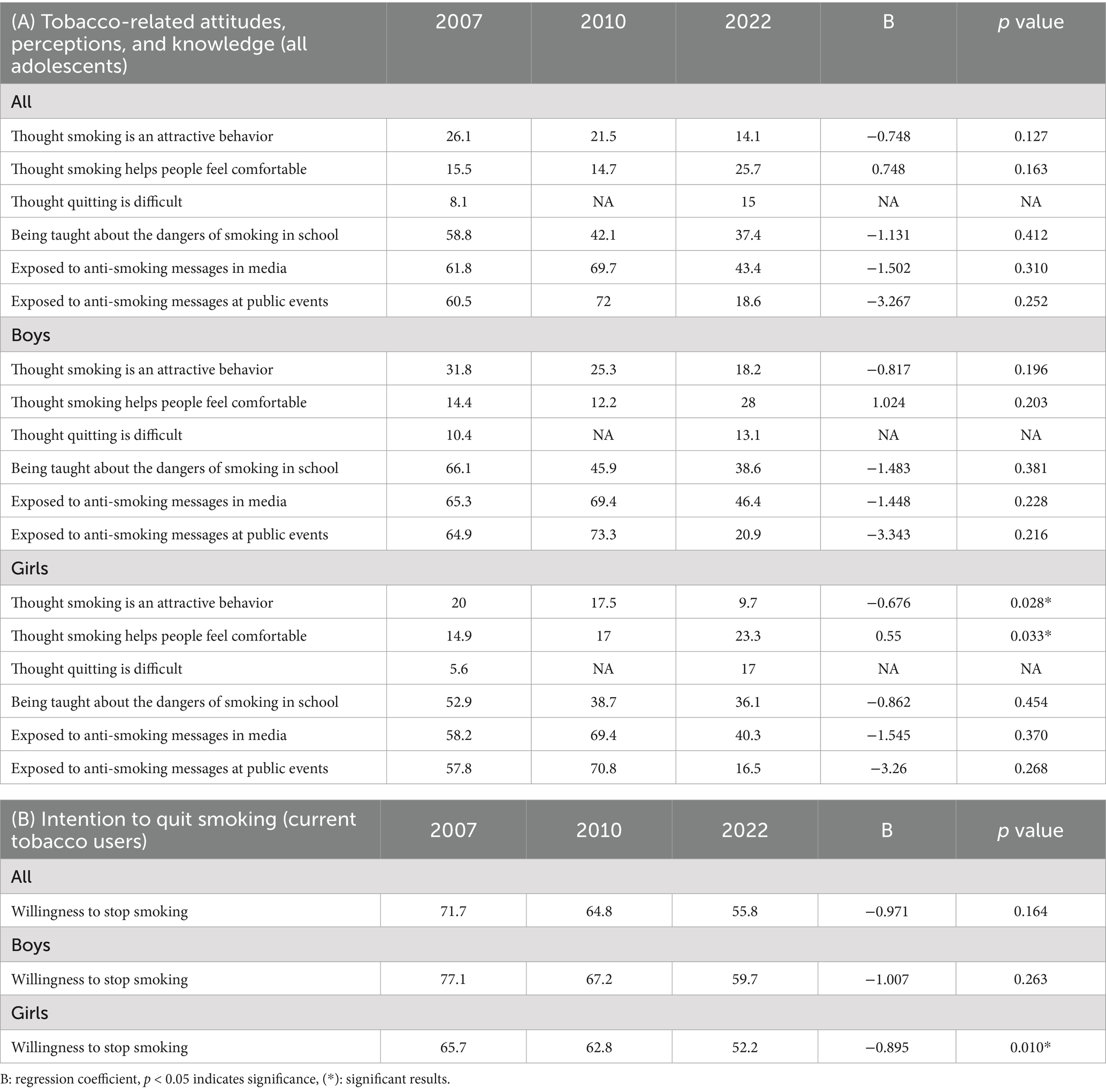

Perceptions of smoking showed significant changes among girls (Table 4). There was a 6.8% decrease in those who thought that smokers were attractive (B = −0.676, p = 0.028), whereas there was a 6.4% increase in those who believed that smoking helped people feel more comfortable (B = 0.55, p = 0.033). The proportion of students taught about the dangers of smoking in class decreased by 21.4%, from 58.8% in 2007 to 37.4% in 2022, whereas exposure to anti-smoking media messages declined by 18.4%, from 61.8 to 43.4%. Further subanalysis of intentions to quit smoking among current tobacco users revealed a significant declining trend among girls, with their quit intention decreasing by 13.5%, from 65.7 to 52.2% (B = −0.895, p = 0.010). Compared with girls, boys had a higher but declining quit intention rate of 17.4%, decreasing from 77.1 to 59.7% (Table 4).

Table 4. Trends in tobacco-related attitudes, perceptions, knowledge and intentions among Saudi adolescents by gender, 2007–2022.

4 Discussion

The goal of this study was to assess the prevalence of tobacco use among youth in Saudi Arabia from 2007 to 2022 using data from the GYTS. The findings highlight progress, including a significant decrease in the prevalence of tobacco use among adolescents in intermediate schools, typically aged 13 and 15, particularly in overall and current cigarette smoking rates. However, trends such as an increase in early smoking initiation and persistent exposure to tobacco advertisements and promotions emphasize the need for continued monitoring and the implementation of targeted behavioral public health interventions to combat and prevent the spread and persistence of this issue. These findings may provide valuable insights for enhancing tobacco control efforts and further reducing tobacco-related health risks among Saudi youth. Moreover, our study offers a comprehensive overview of tobacco use trends among youth over time, serving as a critical resource for decision-makers, researchers, and governments seeking to develop effective strategies to address this pressing public health challenge.

Our findings revealed a significant trend in tobacco use, with a marked decrease over the study period. This decline may be attributable to global efforts to combat tobacco use, alongside initiatives implemented by the Saudi government to limit and prevent tobacco consumption across different age groups. These initiatives included increased value-added taxes on tobacco, the launch of anti-smoking campaigns, and the establishment of anti-smoking clinics, including the introduction of a mobile app. These comprehensive measures reflect Saudi Arabia’s commitment to reducing tobacco use and its associated health risks among its population (5, 25). Furthermore, our study may be among the first to measure the influence of these initiatives on tobacco prevalence in Saudi Arabia.

This study highlights a significant decrease in exposure to second-hand smoke over time. A previous study by Al-Zalabani et al. (26) highlighted a concerning prevalence of second-hand smoke exposure in public places and homes, particularly among adolescents, indicating an urgent need for increased awareness regarding the harmful effects of passive smoking. The reduction in exposure to second-hand smoke observed in our study can be attributable to the implementation of comprehensive tobacco control initiatives and policies aimed at mitigating factors enhancing tobacco use (5). This reduction has significant implications for the overall decrease in tobacco use among youth in Saudi Arabia, as subjective norms reflecting the collective attitudes of smokers in public have changed, leading to a lower risk of tobacco use initiation (27). Collectively, these measures demonstrate the effectiveness of strategic public health interventions in creating a healthier, smoke-free environment.

The findings of this study revealed a noticeable shift in students’ perceptions of tobacco use. Although the proportion of students who associated smoking with attractiveness decreased over time, the proportion of those who perceived smoking as a positive behavior in social contexts increased, particularly among girls. In addition to our findings, previous studies have demonstrated a positive attitude toward smoking (28, 29), suggesting a concerning change in the social appeal of smoking among youth. While the findings of this study revealed a decreasing trend in exposure to tobacco advertisements and promotions, the persistence of the belief that smoking facilitates comfort may be influenced by media portrayals that depict tobacco use as a means of relaxation and social acceptance (30). Therefore, future research should consider the sources from which misconceptions about tobacco use arise when developing tobacco control interventions targeting youth.

Furthermore, our study revealed a concerning decline in the proportion of individuals receiving formal education on the dangers of smoking and exposure to anti-smoking media campaigns. Despite the implementation of strong public health policies, such as graphic warning labels on cigarette packaging, comprehensive bans on tobacco advertising, and the rise of social media platforms promoting healthier lifestyles in general (5, 31), our findings indicate a lag in health awareness and education regarding the harmful effects of tobacco use. Although official reports document ongoing anti-tobacco educational campaigns (32), the results of this study suggest a lack of visibility for anti-tobacco messages. This interpretation is further supported by previous research, which indicates that more effective tobacco control educational campaigns rely on several key factors, including reach, the informational content of messages, message intensity, delivery mode, and duration (33).

The declining trend observed in our study is alarming, as such interventions have been critical in reinforcing knowledge about the risk of tobacco use, fostering community awareness, and ultimately reducing tobacco use among young adults (34, 35). Future efforts should focus on creating effective and culturally tailored anti-tobacco educational campaigns that resonate with the target audience. Investing in anti-tobacco educational interventions within schools and universities, as well as enhancing anti-smoking media campaigns, is crucial for addressing the issue of tobacco use among youth. However, it is equally important to accompany knowledge dissemination with the development of social competence skills that empower youth to resist tobacco product offers (36). Strengthening these efforts can help counter the influence of smoking and reinforce the importance of limiting tobacco use among youth.

Moreover, the intention to quit smoking demonstrated a substantial declining trend, particularly among girls. Several factors may influence the intention to quit smoking among youth, including sociodemographic, social, behavioral, and environmental factors (37, 38). Further investigation into the factors associated with the lack of intention to quit smoking among youth, especially females, is needed to promote smoking cessation. In addition, the findings of this study highlight a critical area for intervention, emphasizing the need for tailored cessation support and targeted public health strategies to address the decreasing motivation to quit smoking. The age of smoking initiation showed troubling trends, with a notable proportion of students reporting their first experience with tobacco at 7 years of age or younger. This increasing trend may be attributable to easy access to tobacco products through social or commercial sources (39), as the GYTS fact sheet mentioned that 51.7% of youth were not refused the purchase of tobacco products due to their age (40). Consequently, there is an urgent need to implement targeted prevention strategies and actively enforce existing tobacco control measures to address early tobacco experimentation and use among youth.

4.1 Limitations

This study has several limitations. First, the use of secondary data from the GYTS may impact reliability, as inconsistencies in survey administration and variations in sampling methods may have existed across the years. Second, relying on self-reported data may imply the possibility of recall and social desirability biases, which could influence the accuracy of the reported prevalence of tobacco use and related behaviors. Third, owing to the cross-sectional nature of the study design, establishing temporal relationships between variables was not possible. Incorporating longitudinal follow-up data could help in assessing changes in tobacco trends and enhance the development of causal relationships. Fourth, the study analysis focused on adolescents aged 13–15 years, which limits the generalizability of the findings to other age groups, such as young adults. Thus, expanding the age range of participants to include young adults would enhance the generalizability of the findings and help in capturing tobacco use beyond the cohort of 13–15 years. Finally, variations in the implementation of tobacco control policies over time may not be fully captured by the study design, limiting the ability to attribute changes in tobacco use directly to specific interventions.

5 Conclusion

The findings from this study show a decline in the prevalence of tobacco use among Saudi adolescents between 2007 and 2022, highlighting progress in tobacco control efforts within the country. However, trends such as early smoking initiation, limited exposure to anti-tobacco education, and misconceptions related to tobacco use underscore the urgent need for ongoing and targeted public health interventions. Understanding the trends of tobacco use among youth over time in Saudi Arabia and assessing changes in factors associated with tobacco use could help policymakers initiate targeted tobacco control initiatives and allocate resources efficiently. Addressing gaps in anti-smoking education, limiting access to tobacco products, and promoting cessation support for youth remain critical priorities. Our study encourages future initiatives to maintain progress and achieve long-term reductions in tobacco-related morbidity and mortality in Saudi Arabia.

Data availability statement

Publicly available datasets were analyzed in this study. This data can be found here: https://www.cdc.gov/tobacco/global/.

Ethics statement

The studies involving humans were approved by the Ministry of Health in Saudi Arabia (IRB log No: 23-M). The studies were conducted in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. The participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study.

Author contributions

SM: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Funding acquisition, Investigation, Methodology, Project administration, Resources, Software, Supervision, Validation, Visualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. ED: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Resources, Software, Validation, Visualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. SA: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Resources, Software, Validation, Visualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. AA-Z: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Resources, Software, Validation, Visualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. MMA: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Resources, Software, Validation, Visualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. MD: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Resources, Software, Validation, Visualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. MS: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Resources, Software, Validation, Visualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. AE: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Resources, Software, Validation, Visualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. MSA: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Project administration, Resources, Software, Validation, Visualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declare that no financial support was received for the research and/or publication of this article.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The authors declare that no Gen AI was used in the creation of this manuscript.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Supplementary material

The Supplementary material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fpubh.2025.1608394/full#supplementary-material

Footnotes

References

1. Institute of Health Metrics. (2019). Global burden of disease database. Available Online at:https://www.healthdata.org/research-analysis/gbd

2. Moradi-Lakeh, M, El Bcheraoui, C, Tuffaha, M, Daoud, F, Al Saeedi, M, Basulaiman, M, et al. Tobacco consumption in the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia, 2013: findings from a national survey. BMC Public Health. (2015) 15:611–10. doi: 10.1186/s12889-015-1902-3

3. Algabbani, AM, Almubark, R, Althumiri, N, Alqahtani, A, and BinDhim, N. The prevalence of cigarette smoking in Saudi Arabia in 2018. Food Drug Regul Sci J. (2018) 1:1 1. doi: 10.32868/rsj.v1i1.22

4. Ministry of Health, World Health Organization, Center for Disease Control and Prevention. Global Adult Tobacco Survey: Fact Sheet Saudi Arabia 2019. (2020). Available online at:https://cdn.who.int/media/docs/default-source/ncds/ncd-surveillance/data-reporting/saudi-arabia/ksa_gats_2019_factsheet_rev_4feb2021-508.pdf?sfvrsn=c349a97a_1&download=true

5. Itumalla, R, and Aldhmadi, B. Combating tobacco use in Saudi Arabia: a review of recent initiatives. East Mediterr Health J. (2020) 26:858–63. doi: 10.26719/emhj.20.019

6. Saudi Statistics Authority. (2023). Saudi youth statistics report 2023. Available online at:https://www.stats.gov.sa/en/

7. DiClemente, RJ, Santelli, JS, and Crosby, R. Adolescent health: Understanding and preventing risk behaviors. California, USA: John Wiley & Sons (2009).

8. Almahmoud, OH, Arabiat, DH, and Saleh, MY. Systematic review and meta-analysis: prevalence of hypertension among adolescents in the Arab countries. J Pediatr Nurs. (2022) 65:e72–9. doi: 10.1016/j.pedn.2022.03.002

9. Alsaidan, AA. Cardiovascular disease management and prevention in Saudi Arabia: strategies, risk factors, and targeted interventions. Int J Clin Pract. (2025) 2025. doi: 10.1155/ijcp/7233591

10. Truth tobacco industry documents. Discussion draft of sociopolitical strategy. (2023). Available online at:https://www.industrydocuments.ucsf.edu/tobacco/docs/#id=zswh0127

11. Aldukhail, S, Alabdulkarim, A, and Agaku, IT. Population-level impact of ‘the real Cost’campaign on youth smoking risk perceptions and curiosity, united sates 2018–2020. Tob Induc Dis. (2023) 21, 1–18. doi: 10.18332/tid/174900

12. World Health Organization. Tobacco free initiative, Saudi Arabia: Offering help to quit tobacco use. (2019). Available online at:https://www.emro.who.int/tfi/news/saudi-arabia-offering-help-to-quit-tobacco-use.html

13. Alasqah, I, Mahmud, I, East, L, and Usher, K. A systematic review of the prevalence and risk factors of smoking among Saudi adolescents. Saudi Med J. (2019) 40:867. doi: 10.15537/smj.2019.9.24477

14. World Health Organization. (2024). WHO global report on trends in prevalence of tobacco use 2000–2030. Available online at:https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789240088283

15. AlDukhail, SK, El Desouky, ED, Monshi, SS, Al-Zalabani, AH, Alanazi, AM, El Dalatony, MM, et al. Electronic cigarette use among adolescents in Saudi Arabia: a national study, 2022. Tob Induc Dis. (2025) 23:4. doi: 10.18332/tid/197410

16. Tobaiqy, M, Thomas, D, MacLure, A, and MacLure, K. Smokers’ and non-smokers’ attitudes towards smoking cessation in Saudi Arabia: a systematic review. Int J Environ Res Public Health. (2020) 17:21. doi: 10.3390/ijerph17218194

17. United Nations. WHO framework convention on tobacco control. Geneva; (2003). Available online at:https://treaties.un.org/pages/viewdetails.aspx?src=treaty&mtdsg_no=ix-4&chapter=9&clang=_en

18. GCC Standardization Organization (GSO). The standards Organization of the Cooperation Council for the Arab states of the Gulf GCC Standardization Organization (GSO). Cigarettes (2009). Report No.: GSO Standard No.597/2009 (E). Available online at:https://assets.tobaccocontrollaws.org/uploads/legislation/Saudi%20Arabia/Saudi-Arabia-GSO-5972009.pdf

19. The Standards Organization of the Cooperation Council for the Arab States of the Gulf GCC STANDARDIZATION ORGANIZATION (GSO). Labeling of tobacco product packages. (2011). Available online at:https://assets.tobaccocontrollaws.org/uploads/legislation/Saudi%20Arabia/Saudi-Arabia-GSO-2462011.pdf

20. Campaign for Tobacco-Free Kids. Legislation by country/jurisdiction, Saudi Arabia. (2024). Available online at:https://www.tobaccocontrollaws.org/legislation/saudi-arabia/laws

21. National Committee for Tobacco Control. (2015). Anti-smoking law royal decree. Report no.: No. (M/56). Available online at:https://assets.tobaccocontrollaws.org/uploads/legislation/Saudi%20Arabia/Saudi-Arabia-Anti-Smoking-Law.pdf

22. Saudi Ministry of Health. Smoking cessation help service. (2023). Available online at:https://www.moh.gov.sa/en/eServices/cards/Pages/TCP.aspx

23. World Health Organization. (2019). WHO report on the global tobacco epidemic 2019: Offer help to quit tobacco use. Geneva, Switzerland; Available online at:https://www.who.int/teams/health-promotion/tobacco-control/who-report-on-the-global-tobacco-epidemic-2019

24. Monshi, SS, Wu, J, Collins, BN, and Ibrahim, JK. Youth susceptibility to tobacco use in the Gulf cooperation council countries, 2001–2018. Prev Med Rep. (2022) 26:101711. doi: 10.1016/j.pmedr.2022.101711

25. Monshi, SS, Arbaein, TJ, Alzhrani, AA, Alzahrani, AM, Alharbi, KK, Alfahmi, A, et al. Factors associated with the desire to quit tobacco smoking in Saudi Arabia: evidence from the 2019 global adult tobacco survey. Tob Induc Dis. (2023) 21:33. doi: 10.18332/tid/159735

26. Al-Zalabani, AH, Amer, SM, Kasim, KA, Alqabshawi, RI, and Abdallah, AR. Second-hand smoking among intermediate and secondary school students in Madinah, Saudi Arabia. Biomed Res Int. (2015) 2015:1–8. doi: 10.1155/2015/672393

27. Shubayr, MA, Alhazmi, AS, El Dalatony, MM, El Desouky, ED, Al-Zalabani, AH, Monshi, SS, et al. Factors associated with tobacco use among Saudi Arabian youth: application of the theory of planned behavior. Tob Induc Dis. (2024) 22:1. doi: 10.18332/tid/196678

28. Show, KL, Phyo, AP, Saw, S, Zaw, KK, Tin, TC, Tun, NA, et al. Perception of the risk of tobacco use in pregnancy and factors associated with tobacco use in rural areas of Myanmar. Tobacco Prevention & Cessation. (2019) 5:36. doi: 10.18332/tpc/112719

29. Grard, A, Schreuders, M, Alves, J, Kinnunen, JM, Richter, M, Federico, B, et al. Smoking beliefs across genders, a comparative analysis of seven European countries. BMC Public Health. (2019) 19:1321–12. doi: 10.1186/s12889-019-7700-6

30. Monshi, SS, Collins, BN, Wu, J, Alzahrani, MAJ, and Ibrahim, JK. Tobacco advertisement, promotion and sponsorship in Arabic media between 2017 and 2019. Health Policy Plan. (2022) 37:990–9. doi: 10.1093/heapol/czac039

31. Ministry of Health. MOH: Anti-smoking awareness campaign launched. (2018); Available online at:https://www.moh.gov.sa/en/Ministry/MediaCenter/News/Pages/News-2018-05-30-006.aspx

32. World Health Organization. (2023). WHO report on the global tobacco epidemic, 2023: Protect people from tobacco smoke. Geneva. Available online at:https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789240077164

33. Durkin, S, Brennan, E, and Wakefield, M. Mass media campaigns to promote smoking cessation among adults: an integrative review. Tob Control. (2012) 21:127–38. doi: 10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2011-050345

34. Rosen, L, Rosenberg, E, McKee, M, Gan-Noy, S, Levin, D, Mayshar, E, et al. A framework for developing an evidence-based, comprehensive tobacco control program. Health Res Policy Syst. (2010) 8:1–13. doi: 10.1186/1478-4505-8-17

35. Institute of Medicine. (2009). Combating tobacco use in military and veteran populations. Available online at:https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK215333/

36. Thomas, RE, McLellan, J, and Perera, R. Effectiveness of school-based smoking prevention curricula: systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ Open. (2015) 5:e006976. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2014-006976

37. Vallata, A, O’Loughlin, J, Cengelli, S, and Alla, F. Predictors of cigarette smoking cessation in adolescents: a systematic review. J Adolesc Health. (2021) 68:649–57. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2020.09.025

38. Bitar, S, Collonnaz, M, O’loughlin, J, Kestens, Y, Ricci, L, Martini, H, et al. A systematic review of qualitative studies on factors associated with smoking cessation among adolescents and young adults. Nicotine Tob Res. (2024) 26:2–11. doi: 10.1093/ntr/ntad167

39. Doubeni, CA, Li, W, Fouayzi, H, and DiFranza, JR. Perceived accessibility as a predictor of youth smoking. Ann Fam Med. (2008) 6:323–30. doi: 10.1370/afm.841

40. World Health Organization. (2022). Global youth tobacco survey: Fact sheet, Saudi Arabia. Available online at:https://www.emro.who.int/images/stories/tfi/documents/saudi_arabia_gyts_2022_factsheet_ages_13-15.pdf?ua=1

Keywords: tobacco use, smoking, shisha, adolescent health, youth, Saudi Arabia

Citation: Monshi SS, Desouky EDE, Aldukhail SK, Al-Zalabani AH, Alqahtani MM, Dalatony MME, Shubayr MA, Elkhobby AA and Aldossary MS (2025) Tobacco use trends among youth in Saudi Arabia: 2007–2022. Front. Public Health. 13:1608394. doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2025.1608394

Edited by:

Ibrahim Alasqah, Qassim University, Saudi ArabiaReviewed by:

Romate John, Central University of Karnataka, IndiaJamie Tam, Yale University, United States

Copyright © 2025 Monshi, Desouky, Aldukhail, Al-Zalabani, Alqahtani, Dalatony, Shubayr, Elkhobby and Aldossary. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Sarah S. Monshi, c3Ntb25zaGlAdXF1LmVkdS5zYQ==

†ORCID: Sarah S. Monshi, https://orcid.org/0000-0002-2360-8575

Sarah S. Monshi

Sarah S. Monshi Eman D. El Desouky2

Eman D. El Desouky2 Abdulmohsen H. Al-Zalabani

Abdulmohsen H. Al-Zalabani Mervat M. El Dalatony

Mervat M. El Dalatony Mohammed S. Aldossary

Mohammed S. Aldossary