- Department of Anesthesiology, Northwest Women's and Children's Hospital, Xi'An, China

Background: With the increasing use of assisted reproductive technology (ART) as a solution for infertility, understanding patient knowledge, attitudes, and practices (KAP) is essential. This study aimed to assess the KAP of infertile women in Northwest China regarding ART and painless egg retrieval.

Methods: This cross-sectional study enrolled infertile female population in the Northwest Region of China from April to September.

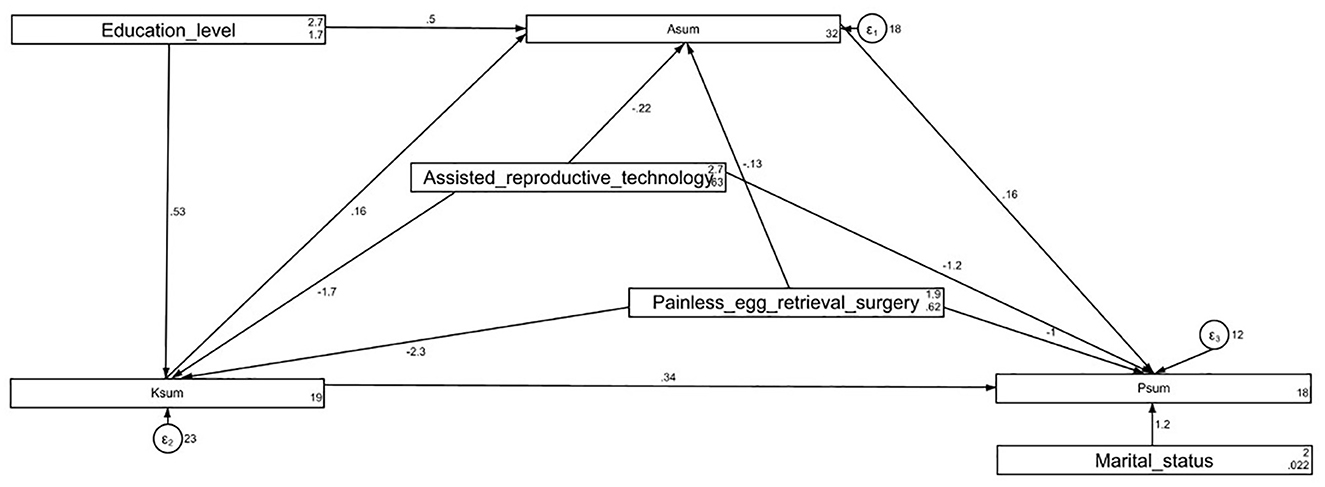

Results: A total of 403 participants were included, with scores of 12.16 ± 5.63 (range: 0–20) for knowledge, 34.30 ± 4.38 (range: 10–50) for attitudes, and 25.28 ± 4.89 (range: 7–35) for practices. Spearman correlation analysis demonstrated the positive correlations between KAP (r = 0.246–0.589, P < 0.001). Structural equation modeling (SEM) showed that knowledge and attitudes are key predictors of practices. Notably, knowledge not only directly influenced practice (β = 0.33, P < 0.001) but also had an indirect effect through its positive impact on attitudes (β = 0.02, P = 0.007).

Conclusion: Infertile women in Northwest China have moderate KAP scores. To improve their adoption of ART, interventions should focus on enhancing their knowledge and improving their attitudes. Tailored support systems, including improved doctor-patient communication and peer support, are particularly vital for women with lower education and less experience with ART.

Background

Infertility is a multifactorial condition, which refers to the inability to conceive after 1 year of regular, unprotected sexual intercourse (1). Infertility affects around 17.5% of the adult population worldwide, with the highest rates found in the Americas, Europe, and the Western Pacific (2). In China, the overall infertility rate among women of reproductive age is estimated to be 15.5% (3). Additionally, a study conducted in Henan Province, China, found a higher infertility prevalence of 24.58% among women aged 20–49 (4). Egg retrieval is a pivotal component, and painless egg retrieval has gained attention as an innovative solution to reduce the discomfort of traditional procedures (5, 6).

Research has reported that the efficacy of ART and egg retrieval varies considerably among infertile women (7). This variation is influenced not only by clinical factors such as age, underlying medical conditions, and ovarian reserve, but also by the knowledge, attitudes, and practices (KAP) of the women undergoing these treatments (8). Knowledge of ART, risks, success rates, and pain management significantly influences a woman's experience with fertility treatments. An informed patient can make decisions aligned with the goals, reduce anxiety, and improve treatment adherence. Positive attitudes toward ART, including acceptance of painless egg retrieval, enhance psychological outcomes and treatment satisfaction. As for practices, women undergoing ART typically engage in medical interventions such as ovarian stimulation, hormone injections, and egg retrieval (8). To optimize success, maintaining a healthy lifestyle, adhering to medical advice on hormone therapies, and managing stress through psychological support are essential (9). Additionally, clear communication with healthcare providers about pain management preferences, including painless egg retrieval, ensures personalized treatment plans.

The KAP study has been commonly used to provide valuable insights into gaps in understanding, positive attitudes and behaviors in a certain health issue (10). Despite the increasing prevalence of infertility, limited KAP evidence has been available regarding painless egg retrieval. A study in China explored women undergoing in vitro fertilization and embryo transfer (IVF-ET), who had inadequate knowledge and negative attitudes, but proactive engagement toward the procedure (11). However, no comprehensive KAP study has been conducted on the broader range of assisted reproductive technologies (ART), including painless egg retrieval, or the interrelationships between KAP.

This study aimed to investigate the KAP of infertile women in the Northwest Region of China regarding ART and painless egg retrieval. The following hypotheses were formulated: (H1) Infertile women's knowledge positively influences their attitudes; (H2) Infertile women's knowledge positively impacts their practices; (H3) Infertile women's attitudes positively affect their practices. By addressing this gap, the study sought to provide a deeper understanding of how these factors shape women's experiences with ART, guide health interventions, and improve patient care.

Methods

Study design and subjects

This cross-sectional study enrolled infertile female population in the Northwest Region of China from April to September. Inclusion criteria: (1) females aged 18 years or older with a desire for fertility treatment; (2) complete medical records available for review; (3) Informed consent and willingness to participate in the survey. Exclusion criteria: (1) presence of endometriosis, adenomyosis, uterine malformations, or other relevant gynecological conditions; (2) presence of mental disorders that may impede participation in the questionnaire survey. This study was approved by the Clinical Research Management Committee of Northwest Women's and Children's Hospital (No. 2024-041), and informed consent was obtained from the study participants.

Questionnaire introduction

A self-designed questionnaire was developed based on existing guidelines and literature (12, 13). The final questionnaire, in Chinese, covered four areas: demographic data, knowledge, attitudes, and practices. The knowledge dimension consisted of 10 questions scored as follows: “Very familiar” for 2 points, “Heard of it” for 1 point, and “Not clear” for 0 points. The total score in the dimension ranged from 0 to 20 points. The attitude dimension included 10 questions on a five-point Likert scale, from “Strongly disagree” (1 point) to “Strongly agree” (5 points). Reverse scoring was applied for items 2, 5, 8, 9, and 10. The total score in the dimension ranged from 10 to 50 points. The practice dimension comprised 7 questions on a five-point Likert scale, from “Always” (5 points) to “Never” (1 point). The total score in the dimension ranged from 7 to 35 points. Overall KAP scores were categorized using Bloom's cut-off values: good (80%−100%), moderate (60%−79%), and poor (< 60%) (14).

Questionnaire distribution and quality control

The survey was distributed via the WeChat-based Wenjuanxing mini-program, accessible through a QR code. To ensure data integrity, only one submission per IP address was allowed, and all questions were mandatory. The research team reviewed completed questionnaires for accuracy, internal consistency, and logical coherence. Responses were excluded if they met any of the following criteria: completion time under 90 s, inconsistent answers, incorrect responses to trap questions, multiple selections, or uniform answers across all KAP items.

A pre-test was conducted among 32 participants with valid responses. The overall Cronbach's α coefficient was 0.891, with 0.935 for knowledge, 0.822 for attitude, and 0.895 for practice, indicating strong internal consistency. In addition to reliability, content validity was ensured by an expert panel of reproductive medicine and nursing specialists who evaluated item relevance and clarity. Face validity was confirmed during the pre-test by collecting participant feedback. Construct validity was assessed using confirmatory factor analysis (CFA), and the results demonstrated good model fit. Detailed factor loadings and fit indices are provided in Supplementary File 1.

Sample size calculation

The calculation of sample size was based on the following formula employed in the cross-sectional study (15):

where n denoted the sample size. Besides, p value was assumed to be 0.5 to achieve the maximum sample size. a refers to the type I error, which was set to 0.05 in this case. Subsequently, was yielded 1.96. δ represents the effect sizes between groups, which was determined as 0.05, and at least 384 participants should be required.

Statistical methods

Statistical analyses were conducted using SPSS 26.0 and AMOS 24.0 (IBM, Armonk, NY, USA). Normality of continuous data was assessed using the Kolmogorov-Smirnov test. For normally distributed data, results are presented as means ± standard deviations (SD), with comparisons made using Student's t-test or ANOVA. Non-normally distributed variables are presented as medians (ranges), with comparisons using the Wilcoxon–Mann–Whitney U-test or Kruskal–Wallis test. Categorical variables are expressed as frequencies (n, %). Spearman's correlation assessed relationships between KAP scores. Multivariate linear regression identified factors influencing practice scores. Structural equation modeling (SEM), based on the KAP framework, examined whether attitudes mediate the relationship between knowledge and practice. Direct and indirect effect sizes were computed and compared. Model fit was evaluated using indices including root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA), standardized root mean square residual (SRMR), Tucker-Lewis index (TLI), and comparative fit index (CFI). A two-tailed P-value < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

Baseline participant information

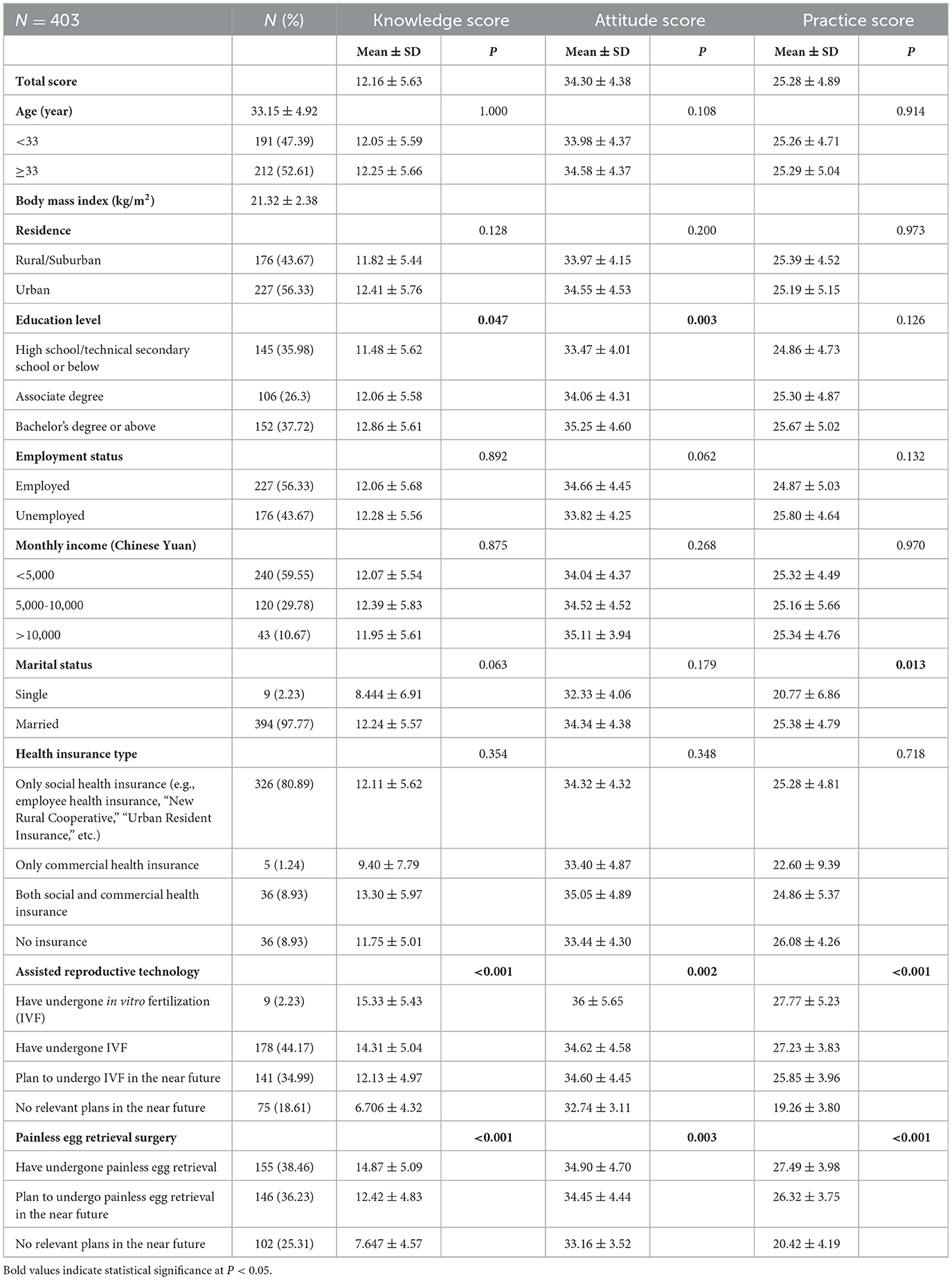

A total of 512 samples were collected, with 109 samples excluded due to the following reasons: one sample had a response time < 90 s, two samples answered trap questions incorrectly, 49 samples had multiple selections for question 7 in the knowledge section, and 55 samples had multiple selections for question 4 in the attitude section. The final dataset consisted of 403 valid participants. The majority of participants were aged ≥33 years (52.61%), urban residents (56.33%), employed (56.33%), earned a monthly income < 5,000 Chinese Yuan (59.55%), and were married (97.77%). Most participants (80.89%) had only social health insurance, including employee health insurance, “New Rural Cooperative,” and “Urban Resident Insurance.” Among the participants, 44.17% had undergone IVF, and 34.99% planned to undergo IVF in the near future. Additionally, 38.46% had undergone painless egg retrieval, and 36.23% planned to do so in the near future (Table 1).

Knowledge dimension

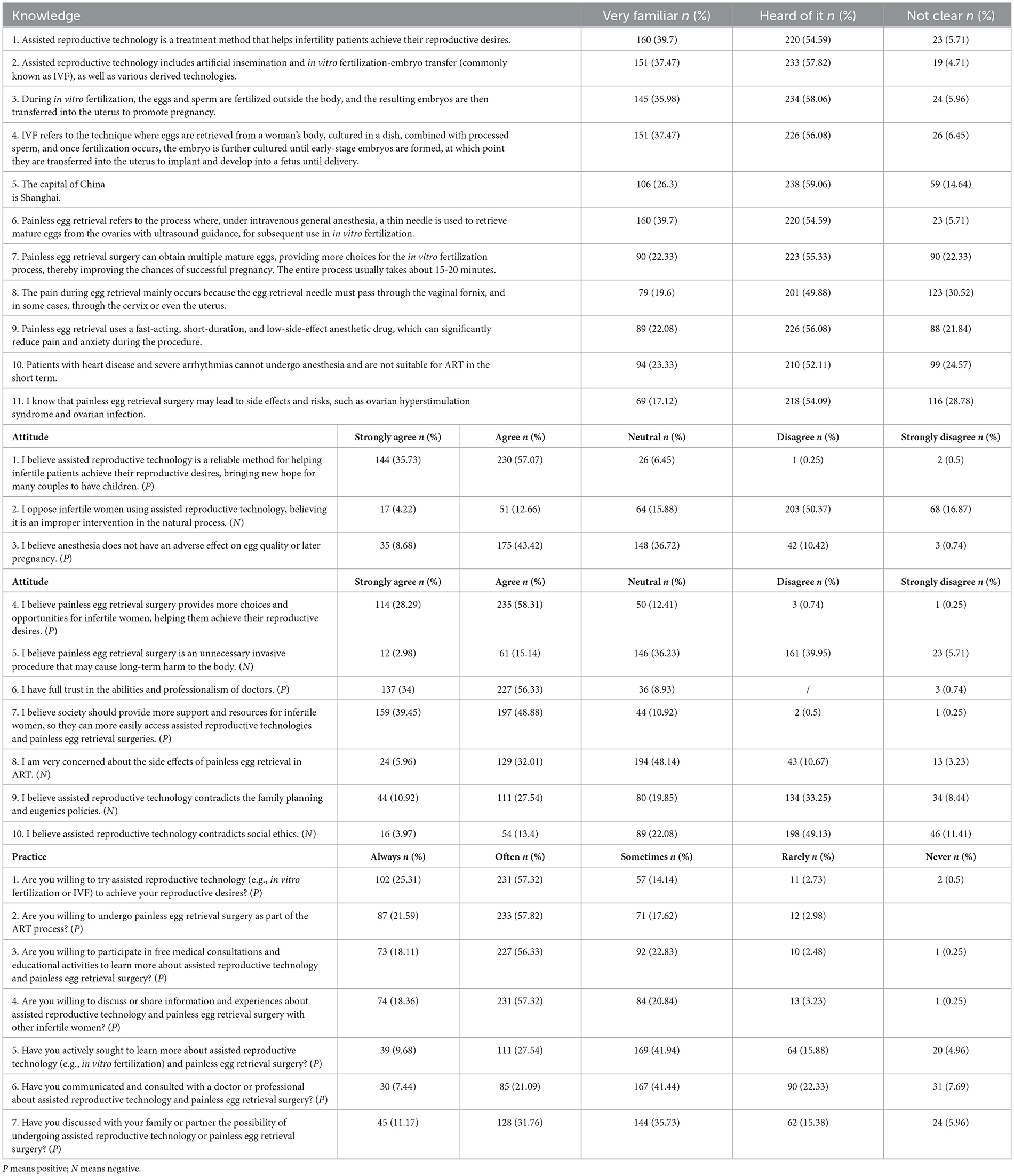

The average knowledge score was 12.16 ± 5.63. Knowledge scores varied significantly by education level (P = 0.047), experience with ART (P < 0.001), and experience with painless egg retrieval (P < 0.001) (Table 1). Familiarity with knowledge items ranged from 17.12% to 39.70%. The highest familiarity (39.70%) was with the statement that ART helps infertility patients achieve reproductive goals (K1), and with the definition of painless egg retrieval (K6). The lowest familiarity (17.12%) was with the potential side effects and risks of painless egg retrieval, such as ovarian hyperstimulation syndrome and ovarian infection (K11). Furthermore, only 19.60% were familiar with the item that pain during egg retrieval results from the needle passing through the vaginal fornix, and sometimes the cervix or uterus (K8) (Table 2).

Attitude dimension

The mean attitude score was 34.30 ± 4.38. Attitude scores varied significantly by education level (P = 0.003), experience with ART (P = 0.002), and experience with painless egg retrieval (P = 0.003) (Table 1). Positive responses (i.e., “Strongly agree” and “Agree” for positive attitude items, and “Strongly disagree” and “Disagree” for negative attitude items) ranged from 13.90% to 92.80%. The highest agreement (92.80%) was with the statement that ART is a reliable method for helping infertile patients achieve reproductive goals, offering hope to many couples (A1). The lowest agreement (13.90%) was with the statement that painless egg retrieval has no concerning side effects (A8). Additionally, a limited proportion (41.69%) expressed a positive attitude toward ART not conflicting with family planning and eugenics policies (A9) (Table 2).

Practice dimension

The average practice score was 25.28 ± 4.89. Practice scores differed significantly by marital status (P = 0.013), experience with ART (P < 0.001), and experience with painless egg retrieval (P < 0.001) (Table 1). Adherence to practice items (“Always” and “Often”) ranged from 28.53% to 82.63%. The highest adherence (82.63%) was to the willingness to try ART (e.g., IVF) to achieve reproductive goals (P1). The lowest adherence (28.53%) was to communicating and consulting with a doctor or professional about ART and painless egg retrieval (P6). Furthermore, only 37.22% of participants actively sought more information about ART and painless egg retrieval (P5) (Table 2).

Spearman correlation

Spearman's correlation analysis revealed significant positive associations between knowledge and attitude (r = 0.246, P < 0.001), knowledge and practice (r=0.589, P < 0.001), and attitude and practice (r = 0.301, P < 0.001) (Supplementary Table S1).

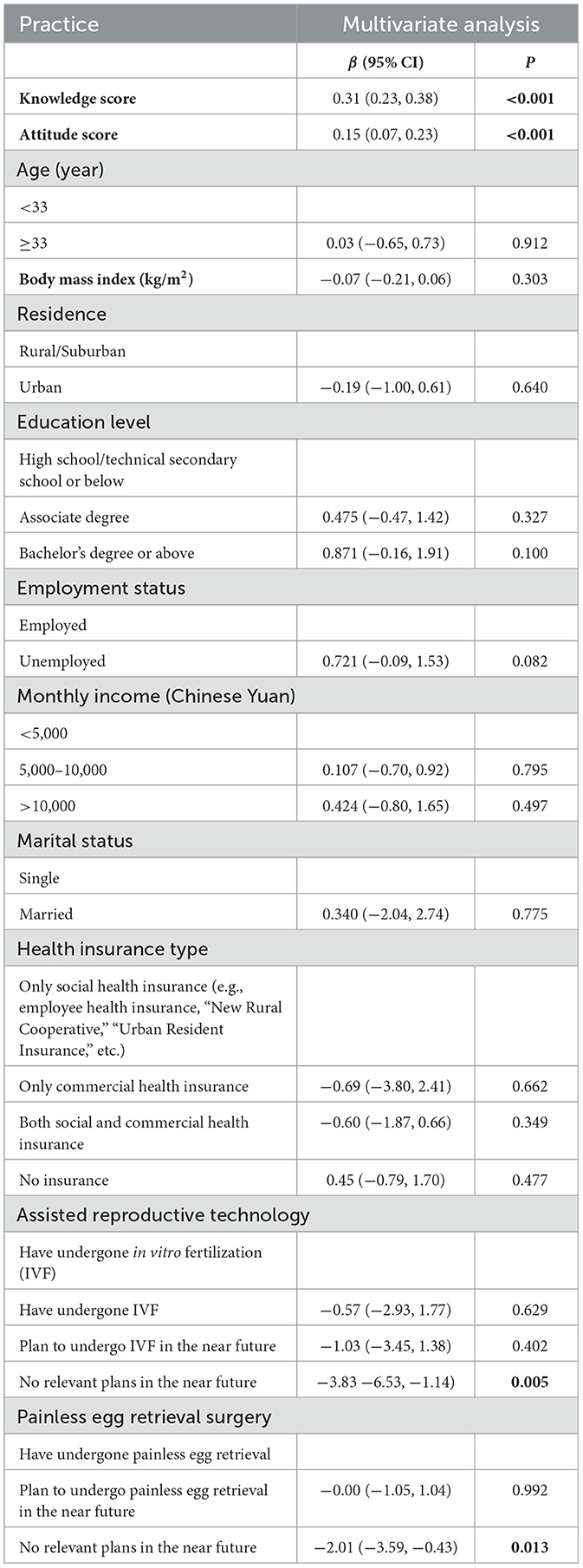

Linear regression analysis

Multivariate regression analysis indicated that both knowledge (β = 0.31, 95% CI: 0.23, 0.38, P < 0.001) and attitude (β = 0.15, 95% CI: 0.07, 0.23, P < 0.001) were positively associated with practice. In contrast, the absence of near-term plans for ART (β = −3.83, 95% CI: −6.53, −1.14, P = 0.005) and painless egg retrieval (β = −2.01, 95% CI: −3.59, −0.43, P = 0.013) negatively influenced practice (Table 3).

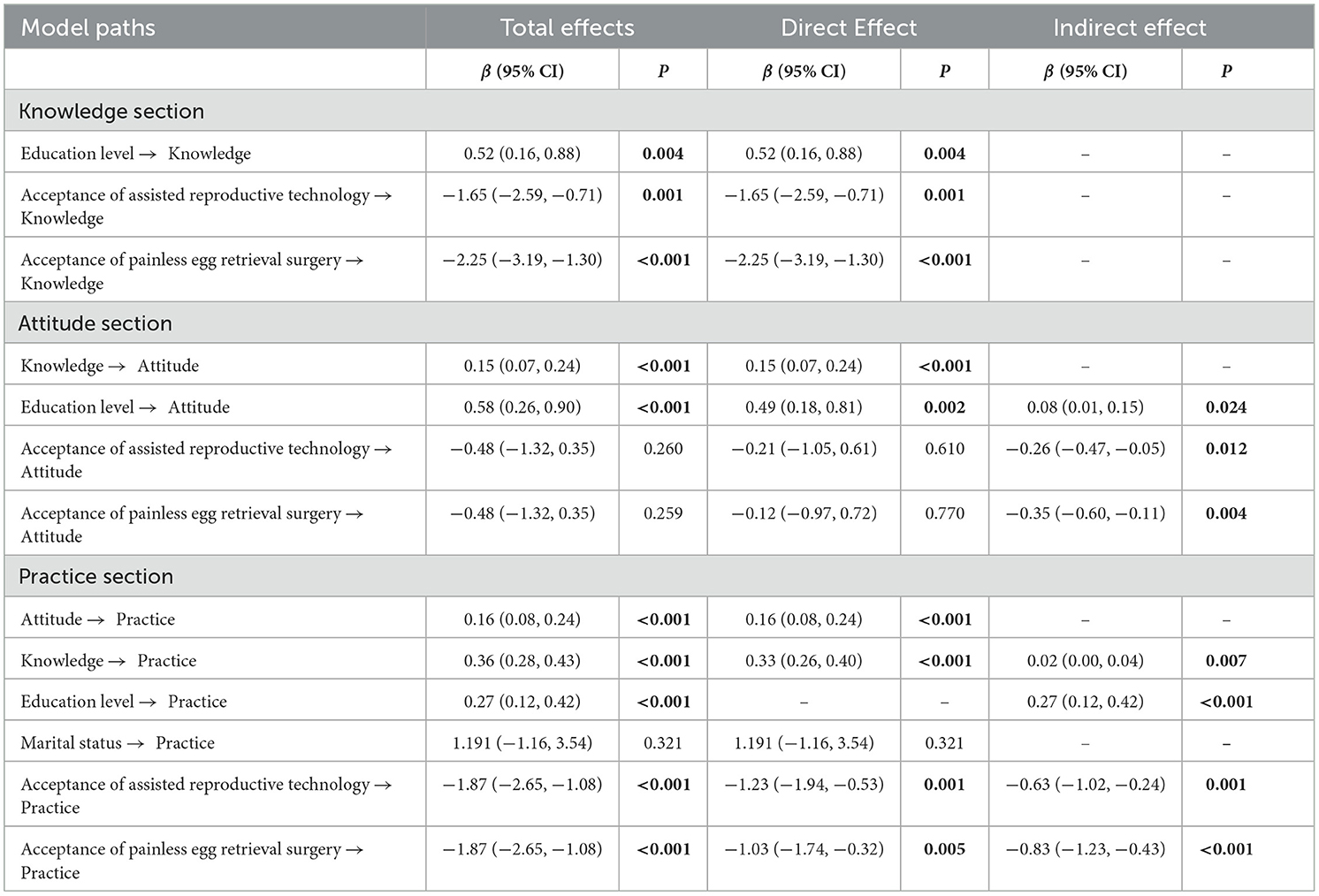

SEM analysis

SEM analysis demonstrated a good model fit (RMSEA < 0.001, SRMR=0.009, TLI = 1.025, CFI = 1.000) (Supplementary Table S2). The analysis showed direct effects of education level (β = 0.52, 95% CI: 0.16, 0.88, P = 0.004), acceptance of ART (β = −1.65, 95% CI: −2.59,−0.71, P = 0.001), and acceptance of painless egg retrieval (β = −2.25, 95% CI: −3.19, −1.30, P < 0.001) on knowledge. Knowledge (β = 0.15, 95% CI: 0.07, 0.24, P < 0.001) and education level (β = 0.49, 95% CI: 0.18, 0.81, P = 0.002) directly impacted attitudes. Additionally, knowledge (β = 0.33, 95% CI: 0.26, 0.40, P < 0.001), attitude (β = 0.16, 95% CI: 0.08, 0.24, P < 0.001), acceptance of ART (β = −1.23, 95% CI: −1.94, −0.53, P = 0.001), and acceptance of painless egg retrieval (β = −1.03, 95% CI: −1.74, −0.32, P = 0.005) had direct effects on practice. Furthermore, knowledge (β = 0.02, 95% CI: 0.00, 0.04, P = 0.007), education level (β = 0.27, 95% CI: 0.12, 0.42, P < 0.001), acceptance of ART (β = −0.63, 95% CI: −1.02, −0.24, P = 0.001), and acceptance of painless egg retrieval (β = −0.83, 95% CI: −1.23, −0.43, P < 0.001) were indirectly associated with practice (Table 4, Figure 1). The structural equation model (SEM) was constructed based on the KAP theoretical framework, in which knowledge was hypothesized to influence attitudes, and both knowledge and attitudes were expected to affect practices. This pathway (knowledge → attitude → practice) reflects the assumption that greater understanding of ART and painless egg retrieval promotes more positive attitudes, which in turn facilitate corresponding health behaviors. Education level and prior acceptance of ART or painless egg retrieval were included as exogenous variables to capture demographic and experiential influences on knowledge, attitudes, and practices. The path diagram is provided in Supplementary File 1.

Table 4. Structural equation modeling (SEM) analysis of direct and indirect effects among KAP scores.

Figure 1. Structural equation model (SEM) model analysis results of KAP scores. All variables are observed variables. Direction of causality is indicated by single-headed arrows. The standardized path coefficients are presented alongside the arrows.

Discussion

Our study revealed that infertile women in the Northwest Region displayed moderate levels of KAP concerning ART and painless egg retrieval. Significant positive correlations existed among the KAP scores, with knowledge indirectly influencing practice. Education level and experience with assisted reproductive technology and painless egg retrieval were key factors affecting KAP scores.

Aligning with our results, only 12.7% of Australian women seeking fertility assistance could accurately identify the fertile window of their menstrual cycle (16). Comparably, although women in the Northwest Region had a basic understanding of ART, many were unaware of more nuanced details, such as treatment procedures and side effects. Contrasting with our results, a study from Iran indicated that the infertile couples held predominantly negative attitudes toward ART (17). Also, another study reported that women undergoing IVF-ET procedures had inadequate knowledge and negative attitudes toward embryo transfer (11). Healthcare providers should enhance counseling with visual aids and digital platforms for better accessibility. Besides, peer support groups are encouraged to inform decision-making and alleviate concerns. The relatively high attitude scores in our study may be attributed to increasing social acceptance of ART in the sampling region and a growing awareness of its benefits. As for practices, only limited proportion of infertile women in our study actually pursued ART treatments and related information. The low uptake could be explained by several factors, including financial constraints, geographic disparities in access to healthcare facilities offering ART, and cultural hesitancy (18). Policymakers should also consider subsidizing ART services and expanding insurance coverage to reduce financial barriers, ultimately promoting equitable access to fertility treatments.

In the knowledge dimension, the high familiarity was with the primary goal of ART and the definition of painless egg retrieval. The findings suggest that the participants had basic understandings of ART, which aligned with previous evidence of women undergoing ART (19). However, the substantial lack of familiarity with the risks of painless egg retrieval underscored a critical gap in the education of infertile women. Ovarian hyperstimulation syndrome arises from ovarian stimulation during ART procedures, which be life-threatening in severe cases (20). Also, ovarian infection can lead to pelvic infections, abdominal pain, and even long-term fertility issues (21). The low level of awareness can be attributed to the focus of healthcare professionals on treatment success rather than on educating patients about risks. Besides, only 19.60% were familiar with the anatomical cause of pain during egg retrieval. Since ART clinics typically prioritize medical explanations over patient-centered education, patients can get insufficient preparation for the physical sensations during egg retrieval (22). Educating women about the side effects and risks of painless egg retrieval, as well as the physiological basis of pain during the procedure, could improve the overall patient experience.

In the attitude dimension, the highest agreement was with the reliability of ART in helping infertile patients achieve reproductive goals. Consistently, the success rates of ART have significantly improved over the years, bolstering its reputation as a viable solution to infertility (23). Conversely, the least proportion held positive attitudes toward the negligible side effects of painless egg retrieval. Consistently, a survey-based study from the United States reported medium or high levels of ART-related stress and depression among infertile individuals (24). Besides, due to the use of sedation and anesthesia in painless egg retrieval, the lack of understanding or inadequate communication can lead to persistent concerns (25). Moreover, less than half of participants expressed a positive attitude toward ART not conflicting with family planning and eugenics policies. The hesitancy in accepting ART could be related to concerns about its ethical implications, potential for “designer babies”, or fear of unintended societal consequences (26). In light of these concerns, patient education must not only focus on the medical and procedural aspects of ART, but also provide a comprehensive understanding of the legal, cultural, and ethical dimensions of ART. Ensuring that women feel supported in navigating these issues will be essential for improving their attitudes toward ART.

Most participants expressed the willingness to try ART, particularly IVF, to achieve reproductive goals. In line with our findings, about 13% of US women of reproductive age seek infertility services, with ART being a common treatment choice (27). This growing willingness can be attributed to advancements in ART technology, improved clinical outcomes, and the broader social acceptance of these procedures. In contrast, the lowest adherence was observed for communicating and consulting with a doctor or professional about ART. Similarly, only limited proportion of participants actively sought more information about ART and painless egg retrieval. One possible explanation was that many women may feel overwhelmed by the medical aspects of ART, leading them to avoid consultations and information-seeking behaviors. Previous research has highlighted that the emotional and psychological burden of infertility can discourage women from actively seeking information or professional advice (28). Additionally, barriers such as insufficient time, financial constraints, and a lack of accessible healthcare resources may play a role in limiting consultations. Clinicians should ensure that their consultations are patient-centered, transparent, and inclusive of comprehensive discussions about ART procedures, potential risks, and the emotional aspects of treatment. Furthermore, providing women with easily accessible resources, such as pamphlets and online content, could help increase their engagement and understanding of ART. Beyond these practical barriers, sociocultural factors may also contribute to the low levels of communication with doctors and limited proactive learning about ART. In China, reproductive health topics are often regarded as private or sensitive, which can discourage open dialogue with healthcare providers. Moreover, traditional family structures may place decision-making power with spouses or older adult, further reducing women's initiative to seek information independently. In comparison, studies in Western countries, such as the United States and Australia, report higher rates of proactive information-seeking and patient–doctor communication, partly due to greater emphasis on patient autonomy and readily available digital health resources (16, 27). These cross-cultural contrasts suggest that interventions in China must not only address financial and logistical challenges, but also consider cultural norms and family dynamics when designing patient education strategies.

In alignment with the health belief theory, positive and direct relationships were identified among KAP scores (29). In other words, individuals with higher levels of knowledge may be more likely to view ART and painless egg retrieval positively, increasing their willingness to pursue these treatments. Besides, knowledge and education level had an indirect association with practice. The results suggest that knowledge serves as a foundational element that can influence psychological and behavioral factors, leading to altered practices. Several influential factors of KAP were reported. First, the negative influence of a lack of acceptance toward ART and painless egg retrieval on practice was found. This highlighted the importance of addressing misconceptions about the treatments to increase patient readiness. Second, women with higher education levels had better knowledge and attitude scores, possibly due to elevated health literacy and socioeconomic status (30).

This study had several limitations. The cross-sectional design restricted causal inferences between KAP and baseline factors. Additionally, the small sample size and regional sampling may limit generalizability of our findings. Self-reported data may also introduce social desirability bias, potentially inflating KAP scores (31). Moreover, as the survey was distributed via the WeChat-based Wenjuanxing platform, participants may have been skewed toward those who are more digitally literate and predominantly urban residents, potentially limiting representativeness of the findings.

In China, national conditions such as the high financial burden of ART, limited health insurance coverage, and regional disparities in ART service availability also affect women's knowledge, attitudes, and practices. These factors may partly explain the moderate KAP levels observed in this study.

Conclusion

In conclusion, infertile women in the Northwest Region of China exhibited moderate KAP regarding ART and painless egg retrieval. Positive and direct correlations were found among KAP scores, with knowledge indirectly influencing practice. Targeted educational interventions on doctor-patient communication and peer support should be implemented, particularly for women with lower education levels and limited ART experience.

Data availability statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/Supplementary material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Ethics statement

The studies involving humans were approved by the Ethics Committee of Northwest Women and Children's Hospital (No: 2024-041). The studies were conducted in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. The participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study.

Author contributions

QZ: Writing – original draft, Conceptualization, Writing – review & editing. JW: Data curation, Conceptualization, Writing – original draft. TL: Data curation, Conceptualization, Writing – original draft. XW: Writing – review & editing, Investigation, Methodology. JG: Project administration, Methodology, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declare that no financial support was received for the research and/or publication of this article.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The author(s) declare that no Gen AI was used in the creation of this manuscript.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Publisher's note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Supplementary material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fpubh.2025.1614206/full#supplementary-material

References

1. Akalewold M, Yohannes GW, Abdo ZA, Hailu Y, Negesse A. Magnitude of infertility and associated factors among women attending selected public hospitals in Addis Ababa, Ethiopia: a cross-sectional study. BMC Womens Health. (2022) 22:1–11. doi: 10.1186/s12905-022-01601-8

2. Cox CM, Thoma ME, Tchangalova N, Mburu G, Bornstein MJ, Johnson CL, et al. Infertility prevalence and the methods of estimation from 1990 to 2021: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Hum Reprod Open. (2022) 2022:hoac051. doi: 10.1093/hropen/hoac051

3. Zhou Z, Zheng D, Wu H, Li R, Xu S, Kang Y, et al. Prevalence of infertility in China: a population based study. Fertil Steril. (2017) 108:e114. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2017.07.348

4. Liang S, Chen Y, Wang Q, Chen H, Cui C, Xu X, et al. Prevalence and associated factors of infertility among 20-49 year old women in Henan Province, China. Reprod Health. (2021) 18:254. doi: 10.1186/s12978-021-01298-2

5. Ockhuijsen HDL, Ophorst I, Van Den Hoogen A. The experience of Dutch women using a coping intervention for oocyte retrieval: a qualitative study. J Reprod infertil. (2020) 21:207.

6. Shao X, Qin J, Li C, Zhou L, Guo L, Lu Y, et al. Tetracaine combined with propofol for painless oocyte retrieval: from a single center study. Ann Palliat Med. (2020) 9:1606613–1613. doi: 10.21037/apm-19-273

7. Bai F, Wang DY, Fan YJ, Qiu J, Wang L, Dai Y, et al. Assisted reproductive technology service availability, efficacy and safety in Mainland China: 2016. Hum Reprod. (2020) 35:446–52. doi: 10.1093/humrep/dez245

8. Graham ME, Jelin A, Hoon Jr AH, Wilms Floet AM, Levey E, Graham EM. Assisted reproductive technology: short-and long-term outcomes. Dev Med Child Neurol. (2023) 65:38–49. doi: 10.1111/dmcn.15332

9. Cirillo M, Coccia ME, Fatini C. Lifestyle and comorbidities: do we take enough care of preconception health in assisted reproduction? J Family Reprod Health. (2020) 14:150. doi: 10.18502/jfrh.v14i3.4667

10. Zarei F, Dehghani A, Ratansiri A, Ghaffari M, Raina SK, Halimi A, et al. Checkap: a checklist for reporting a knowledge, attitude, and practice (Kap) study. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev. (2024) 25:2573–7. doi: 10.31557/APJCP.2024.25.7.2573

11. Xu Y, Hao C, Zhang H, Liu Y, Xue W. Knowledge, attitude, and practice of embryo transfer among women who underwent in vitro fertilization-embryo transfer. Front Cell Dev Biol. (2024) 12:1405250. doi: 10.3389/fcell.2024.1405250

12. ESHRE ESHRE Working Group on Ultrasound in ART, D'Angelo A, Panayotidis C, Amso N, Marci R, Matorras R, et al. Recommendations for good practice in ultrasound: oocyte pick up. Hum Reprod Open. (2019) 2019:hoz025. doi: 10.1093/hropen/hoz025

13. ESHRE ESHRE Guideline Group on Viral infection/disease, Mocanu E, Drakeley A, Kupka MS, Lara-Molina EE, Le Clef N, et al. ESHRE guideline: medically assisted reproduction in patients with a viral infection/disease. Hum Reprod Open. (2021) 2021:hoab037. doi: 10.1093/hropen/hoab037

14. Feleke BT, Wale MZ, Yirsaw MT. Knowledge, attitude and preventive practice towards Covid-19 and associated factors among outpatient service visitors at debre markos compressive specialized hospital, North-West Ethiopia, 2020. PLoS ONE. (2021) 16:e0251708. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0251708

15. Pourhoseingholi MA, Vahedi M, Rahimzadeh M. Sample size calculation in medical studies. Gastroenterol Hepatol Bed Bench. (2013) 6:14–7.

16. Hampton KD, Mazza D, Newton JM. Fertility-awareness knowledge, attitudes, and practices of women seeking fertility assistance. J Adv Nurs. (2013) 69:1076–84. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2648.2012.06095.x

17. Sheikhian M, Hasanzadeh P, Tavakol Z. Knowledge, attitudes, and practice of infertile couples about assisted reproductive technology, 2020: a cross-sectional study. Health Tech Ass Act. (2023) 6. doi: 10.18502/htaa.v6i4.12817

18. Zhou Q, Zeng H, Wu L, Diao K, He R, Zhu B. Geographic disparities in access to assisted reproductive technology centers in China: spatial-statistical study. JMIR Public Health Surveill. (2024) 10:e55418. doi: 10.2196/55418

19. Anaman-Torgbor JA, Jonathan JWA, Asare L, Osarfo B, Attivor R, Bonsu A, et al. Experiences of women undergoing assisted reproductive technology in Ghana: a qualitative analysis of their experiences. PLoS ONE. (2021) 16:e0255957. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0255957

20. Nahid S, Alansari L, Ummunnisa F, Amara UE, Ramireddy N, Almarzooqi T. Ovarian hyperstimulation syndrome. In: Updates in Intensive Care of Obgy Patients. Cham: Springer (2024). p. 181–208. doi: 10.1007/978-981-99-9577-6_11

21. Frock-Welnak DN, Tam J. Identification and treatment of acute pelvic inflammatory disease and associated sequelae. Obstet Gynecol Clin. (2022) 49:551–79. doi: 10.1016/j.ogc.2022.02.019

22. Péloquin S, Garcia-Velasco JA, Blockeel C, Rienzi L, de Mesmaeker G, Lazure P, et al. Educational needs of fertility healthcare professionals using art: a multi-country mixed-methods study. Reprod Biomed Online. (2021) 43:434–45. doi: 10.1016/j.rbmo.2021.06.020

23. Chambers GM, Dyer S, Zegers-Hochschild F, de Mouzon J, Ishihara O, Banker M, et al. International committee for monitoring assisted reproductive technologies world report: assisted reproductive technology, 2014. Hum Reprod. (2021) 36:2921–34. doi: 10.1093/humrep/deab198

24. Zanettoullis AT, Mastorakos G, Vakas P, Vlahos N, Valsamakis G. Effect of stress on each of the stages of the Ivf procedure: a systematic review. Int J Mol Sci. (2024) 25:726. doi: 10.3390/ijms25020726

25. Egan M, Schaler L, Crosby D. Anaesthesia considerations for assisted reproductive technology: a focused review. Int J Obstet Anesth. (2024) 60:104248. doi: 10.1016/j.ijoa.2024.104248

26. Raposo VL. From public eugenics to private eugenics: what does the future hold? JBRA Assist Reprod. (2022) 26:666–74. doi: 10.5935/1518-0557.20220032

27. Mayette E, Scalise A, Li A, McGeorge N, James K, Mahalingaiah S. Assisted reproductive technology (Art) patient information-seeking behavior: a qualitative study. BMC Womens Health. (2024) 24:346. doi: 10.1186/s12905-024-03183-z

28. Buran G, Toptaş Acar B. The effect of social and emotional capacities on coping strategies and stress in infertile individuals. Curr Psychol. (2024) 43:29984–94. doi: 10.1007/s12144-024-06504-5

29. Hossain MB, Alam MZ, Islam MS, Sultan S, Faysal MM, Rima S, et al. Health belief model, theory of planned behavior, or psychological antecedents: what predicts covid-19 vaccine hesitancy better among the bangladeshi adults? Front Public Health. (2021) 9:711066. doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2021.711066

30. Coughlin SS, Vernon M, Hatzigeorgiou C, George V. Health literacy, social determinants of health, and disease prevention and control. J Environ Health Sci. (2020) 6:3061.

Keywords: infertility, assisted reproductive technology, painless egg retrieval, knowledge, attitudes, practice

Citation: Zhang Q, Wang J, Li T, Wang X and Geng J (2025) Knowledge, attitudes, and practices toward assisted reproductive technology and painless egg retrieval among infertile women in the northwest region of China. Front. Public Health 13:1614206. doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2025.1614206

Received: 18 April 2025; Accepted: 01 September 2025;

Published: 02 October 2025.

Edited by:

Luna Samanta, Ravenshaw University, IndiaReviewed by:

Gisoo Shin, Chung-Ang University, Republic of KoreaFatema-Tuz- Zohora, University of Asia Pacific, Bangladesh

Copyright © 2025 Zhang, Wang, Li, Wang and Geng. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Juan Geng, NDkxNjk4MDU0QHFxLmNvbQ==

Qiaomei Zhang

Qiaomei Zhang Juan Geng

Juan Geng