- 1Department of Respiratory and Critical Care Medicine, First Hospital of Quanzhou Affiliated to Fujian Medical University, Quanzhou, China

- 2Department of Gastric Surgery, Fujian Medical University Union Hospital, Fuzhou, China

Background: Tracheal, bronchus, and lung (TBL) cancer remains the leading cause of cancer-related mortality worldwide. While smoking is the primary risk factor, several non-smoking-related factors also significantly contribute to TBL cancer, notably second-hand smoke (SHS) exposure, which plays a substantial role in the disease’s burden. This study assesses and forecasts the temporal trends in the disease burden of TBL cancer attributable to SHS exposure at global, regional, and national levels.

Methods: We extracted data from the ≥ 25 years population in the Global Burden of Disease Study 2021 (GBD 2021) to assess deaths, disability-adjusted life years (DALYs), age-standardized mortality rate (ASMR), and age-standardized DALY rate (ASDR) at both global and regional levels. We evaluated temporal trends using descriptive statistics, estimated annual percentage change (EAPC), and both the age-period-cohort (APC) and Bayesian age-period-cohort (BAPC) models.

Results: From 1992 to 2021, absolute deaths and DALYs linked to TBL cancer due to SHS exposure increased, although ASMR and ASDR showed declining trends, with EAPC values of −0.92% and −1.30%, respectively. Regions with a high socio-demographic index (SDI) displayed the most significant improvements. In contrast, high-middle and middle SDI regions bore the greatest disease burden, and low SDI regions saw minimal progress. The highest ASMR in 2021 occurred mainly in Western Europe, North America, and East Asia, with ASMR correlating positively with SDI. The disease burden was consistently higher among males, particularly in the 65–74 age group, across both sexes. Future projections indicate a continuing decline in the disease burden from 2022 to 2046.

Conclusion: SHS exposure continues to be a significant factor in the disease burden of TBL cancer. Although there has been an overall declining trend globally, it still caused the deaths of more than 97,000 people in 2021. There exists considerable heterogeneity among regions, with some areas still bearing a substantial disease burden. These findings highlight the need for specific prevention and control strategies to mitigate the health impacts of SHS exposure.

1 Introduction

Tracheal, bronchus, and lung (TBL) cancer is recognized as one of the most formidable malignancies worldwide and poses a significant challenge to public health. According to the International Agency for Research on Cancer (IARC), in 2022, approximately 2,480,675 cases of TBL cancer were documented, representing 12.4% of all cancer cases globally. Furthermore, TBL cancer accounted for 1,817,469 deaths, or 18.7% of all cancer-related fatalities, ranking it highest in both incidence and mortality among malignancies, with a trend that continues to rise (1). Projections indicate that by 2050, TBL cancer will account for 13.1% of new global cancer cases and 19.2% of cancer-related deaths (2), highlighting its escalating impact and persistent threat to public health.

Smoking remains the predominant risk factor for TBL cancer. Although there has been a significant reduction in smoking-related TBL cancer cases due to effective tobacco control measures over recent decades, some studies report an increase in cases among never-smokers (3). Non-smoking risk factors contributing to TBL cancer include airborne particulate matter pollution, occupational exposures (such as asbestos), and second-hand smoke (SHS) exposure. SHS, also known as passive smoking or environmental tobacco smoke, refers to the inhalation of tobacco smoke by non-smokers, with sidestream smoke being the primary component of SHS, containing multiple harmful substances similar to those found in active smoking (4). Current research demonstrates that SHS is highly correlated with increased risk of cardiovascular disease (5), respiratory diseases (6), and TBL cancer (7). In 2019, the World Health Organization (WHO) estimated that SHS resulted in a global loss of 37 million DALYs and caused 1.3 million deaths (8). It is estimated that 37% of the global population remains exposed to smoke emitted from the burning end of tobacco products or exhaled by smokers (9, 10). The IARC has now classified SHS as a Group 1 carcinogen, confirming its established role in causing human cancers, particularly TBL cancer (11). Research has identified over 7,000 chemicals in SHS, including at least 80 recognized carcinogens (12). These substances initiate the malignant transformation of lung cells through various mechanisms such as genetic mutations, epigenetic alterations, and oxidative stress (13–15). The impact of SHS exposure on TBL cancer risk has gained significant attention in recent years. Studies have shown that non-smokers with long-term exposure to SHS have a 20–30% increased risk of developing TBL cancer (16, 17). A meta-analysis on the association between SHS and TBL cancer revealed that never-smokers exposed to SHS have a significantly higher risk of cancer compared to those unexposed, with a relative risk (RR) of 1.24 (95% CI: 1.16 to 1.32) (18). These epidemiological studies further validate the link between SHS exposure and the development of TBL cancer.

Given the significant disease burden of TBL cancer on public health, although numerous studies have explored the association of TBL cancer with smoking, outdoor particulate pollution, and occupational hazards (19–23), there are no published papers that describe and explore the long-term burden trends of TBL cancer caused by SHS categorized by age, gender, location, and SDI using APC and BAPC models. Therefore, this study aims to utilize APC and BAPC models to quantify and predict the TBL cancer burden attributable to SHS exposure in 204 countries and territories from 1992 to 2021, stratified by age, sex, location, and SDI. This approach not only separates the effects of aging, historical factors of risk exposure, and vulnerabilities specific to birth cohorts, but also projects the age-standardized mortality rates for secondhand smoke-attributable lung cancer from 2022 to 2046. Through this comprehensive analysis, we aim to provide robust and detailed scientific evidence to elucidate the long-term effects of SHS on TBL cancer, offer key insights for the development of targeted intervention strategies, and ultimately drive global advancements in TBL cancer prevention and control.

2 Materials and methods

2.1 Study data

The GBD study, initiated in 1990, offers a foundational data source for global health research through its comprehensive scope and systematic methodology. This international collaborative project covers 204 countries and territories, evaluating 371 diseases and injuries alongside 88 risk factors. These locations are further categorized into 21 regions and 7 super-regions (24). In our study, we utilized secondary data from the GBD collaborative platform to assess the burden of TBL cancer attributable to SHS exposure. We analyzed relevant data at global, national, and regional levels for 2021 and projected trends from 2022 to 2046.

The codes for TBL cancer were sourced from the International Classification of Diseases (ICD)-9 and ICD-10 coding books. The ICD-9 codes include 162-162.9, 209.21, V10.1-V10.20, V16.1-V16.2, and V16.4-V16.40, while ICD-10 codes include C33, C34-C34.92, Z12.2, Z80.1-Z80.2, and Z85.1-Z85.20 (25). SHS exposure is defined as the inhalation of tobacco smoke in household, occupational, or public environments (26). Regarding the attribution estimation methods for TBL cancer attributable to SHS exposure, GBD 2021 followed the general framework established by Comparative Risk Assessment (CRA), which can be divided into six key steps: identifying SHS-TBL cancer pairs based on systematic reviews and meta-regressions; estimating relative risks from SHS-TBL cancer risk curves using the meta-regressions, regularized, and trimmed (MR-BRT) method; estimating the age-sex-location-year distribution of ambient SHS exposure levels; setting the theoretical minimum risk exposure level (TMREL) as zero exposure, meaning complete avoidance of SHS exposure; considering different exposure scenarios in household environments, workplaces, and public places, using spatiotemporal modeling methods to estimate exposure distributions in data-sparse regions; and estimating population attributable fractions and attributable burden using formulas that account for risk functions, individual exposure distributions across age-sex-location-years, and TMREL, while quantifying uncertainty intervals of estimates through 1,000 uncertainty draws (8, 25, 27). Notably, the GBD 2021 database excludes data on SHS-attributable TBL cancer burden for populations under 25 years old; hence, our study focuses on those aged 25 and older. Through the GBD Results Tool1, we extracted annual data on SHS-attributable TBL cancer deaths, disability-adjusted life years (DALYs), age-standardized mortality rate (ASMR), and age-standardized DALY rate (ASDR) from 1992 to 2021, stratified by sex, age, and geographic location. The GBD database includes 21 GBD regions and 204 countries or territories, which are categorized into five SDI quintiles: low, low-middle, middle, high-middle, and high. The SDI is a composite development indicator comprising total fertility rate, average educational attainment, and per capita disposable income. It ranges from 0 (theoretical minimum development) to 1 (theoretical maximum development), reflecting a country’s overall social and economic development. Moreover, this study uses 15 age groups (in 5-year intervals from 25 to 94 years and ≥95 years), providing a multidimensional, detailed framework for evaluating the global burden of TBL cancer attributable to SHS exposure.

2.2 Statistical analysis

To examine the burden of TBL cancer attributable to SHS exposure, we implemented a multi-level statistical analysis. We used the Estimated Annual Percentage Change (EAPC) to quantify long-term trends in the ASMR and ASDR rate from 1992 to 2021. We applied a log-linear regression model:

Temporal trends were categorized as increasing if the 95% CI of the EAPC estimate exceeded 0, decreasing if the 95% CI was below 0, and stable if the 95% CI included 0.

We evaluated the associations between ASMR/ASDR and the SDI using Pearson correlation and linear regression analyses, with statistical significance determined by two-tailed p-values < 0.05.

The age-period-cohort (APC) model, a cornerstone in contemporary epidemiological research, disentangles epidemiological indicators into three temporal dimensions: age, period, and birth cohort. Age effects describe the impact of biological aging on disease occurrence, period effects capture the impact of specific historical periods on disease incidence, and cohort effects reflect variations in risk factor exposure across different birth cohorts (28). We divided the study population into 15 consecutive 5-year age groups (from 25 to 99 years) during the period from 1992 to 2021, covering 20 consecutive birth cohorts. We analyzed key parameters, using the APC Web Tool provided by the National Cancer Institute. Parameter significance was assessed with Wald chi-square tests.

Furthermore, we employed the Bayesian age-period-cohort (BAPC) model with integrated nested Laplace approximations (using R packages BAPC and INLA) to project ASMR for TBL cancer attributable to SHS exposure from 2022 to 2046 (29). The ‘BAPC ()’ and ‘INLA ()’ functions were employed to fit the age-period-cohort model and estimate posterior distributions of model parameters, respectively. Data were structured into 5-year age intervals (specific age groups were categorized as under 5 years, 5–9 years, 10–14 years, etc., up to 95 years and above, totaling 20 age groups), with a time span from 1990 to 2021, incrementing annually. Population data and disease rates for each age group and period were prepared in matrix format, with rows representing age groups and columns representing periods. These data were input into the ‘BAPC ()’ function, with age and time dimensions specified accordingly. Standard population data were sourced from the GBD Study 2021, available at [IHME GBD 2021 Demographics] (Global Burden of Disease Study 2021 (GBD 2021) Demographics 1950-2021|GHDx). This dataset provides age-specific population weights from 1950 to 2021, which were used for standardized analysis in this study. The 95% uncertainty intervals (UIs) for predicted rates were calculated using posterior distributions derived from the BAPC model. These data were obtained through the ‘INLA’ package, which provides posterior marginal distributions for each parameter. The uncertainty intervals were calculated as the 2.5th and 97.5th percentiles of the posterior distributions (29). Compared to other forecasting methods, this approach not only provides superior prediction coverage and accuracy, but also offers important scientific evidence for future public health policy development (30). All statistical analyses were conducted in R software (version 4.4.1), ensuring methodological consistency and reproducibility.

3 Results

3.1 TBL cancer burden attributable to SHS exposure by global, SDI and GBD regions

The global burden of TBL cancer attributable to SHS exposure has shown significant changes from 1992 to 2021. The number of global deaths increased from 59,998.3 (95% Uncertainty Interval [UI]: 7,076.9 to 113,306.0) in 1992 to 97,910.8 (95% UI: 11,955.2 to 184,912.9) in 2021. Despite the rise in absolute numbers, the ASMR decreased from 1.44 (95% UI: 0.17 to 2.73) to 1.14 (95% UI: 0.14 to 2.15) per 100,000 population, with an EAPC of −0.92 (95% CI: −0.98 to −0.87). DALYs increased from 1,654,275.7 (95% UI: 195,097.3 to 3,113,584.6) to 2,355,866.0 (95% UI: 290,210.9 to 4,442,996.3), while the ASDR decreased from 38.09 (95% UI: 4.49 to 71.66) to 26.93 (95% UI: 3.32 to 50.83) per 100,000 population, with an EAPC of −1.30 (95% CI: −1.35 to −1.25) (Table 1).

Table 1. Global, SDI, and GBD regional burden of TBL cancer attributable to SHS exposure in 1992 and 2021, and the temporal trends from 1992 to 2021.

Significant disparities in the burden and trends of TBL cancer were evident across SDI regions in 2021. High-middle SDI regions experienced the highest burden with 39,124.1 deaths (95% UI: 4,613.2 to 73,341.1), followed by middle SDI regions with 35,511.4 deaths (95% UI: 4,496.6 to 67,456.6). In contrast, low SDI regions had the lowest burden with 769.7 deaths (95% UI: 93.9 to 1,556.2) (Table 1). High SDI regions demonstrated the most significant improvements in both the ASMR (EAPC: −2.64 [95% CI: −2.75 to −2.54]) and ASDR (EAPC: −3.01 [95% CI: −3.12 to −2.90]), with deaths decreasing to 16,945.3 (95% UI: 2,216.0 to 32,742.6) and DALYs declining to 380,284.8 (95% UI: 49,959.2 to 738,239.8) (Table 1). Conversely, both high-middle and middle SDI regions showed increases in absolute deaths and DALYs, despite moderate decreases in age-standardized rates.

Among GBD regions in 2021, East Asia, Western Europe, and High-income North America bore substantial burdens. East Asia faced the highest burden with 59,196.3 deaths (95% UI: 7,267.3 to 111,539.5) and 1,387,974.7 DALYs (95% UI: 172,610.9 to 2,594,495.8), showing minimal improvement in ASMR (EAPC: 0.06 [95% CI: −0.07 to 0.18]) (Table 1). Western Europe ranked second with 6,226.9 deaths (95% UI: 775.5 to 12,307.0) and 150,798.7 DALYs (95% UI: 19,175.0 to 295,048.8), followed by High-income North America, which demonstrated the largest improvements in both ASMR (EAPC: −3.87 [95% CI: −4.01 to −3.73]) and ASDR (EAPC: −4.22 [95% CI: −4.36 to −4.09]). Western Europe also showed notable improvements (EAPC in ASMR: −2.64 [95% CI: −2.73 to −2.54]; EAPC in ASDR: −2.85 [95% CI: −2.97 to −2.73]), while Oceania notably exhibited an upward trend in ASMR (EAPC: 0.29 [95% CI: 0.21 to 0.38]) (Table 1).

3.2 TBL cancer burden attributable to SHS exposure by national regions

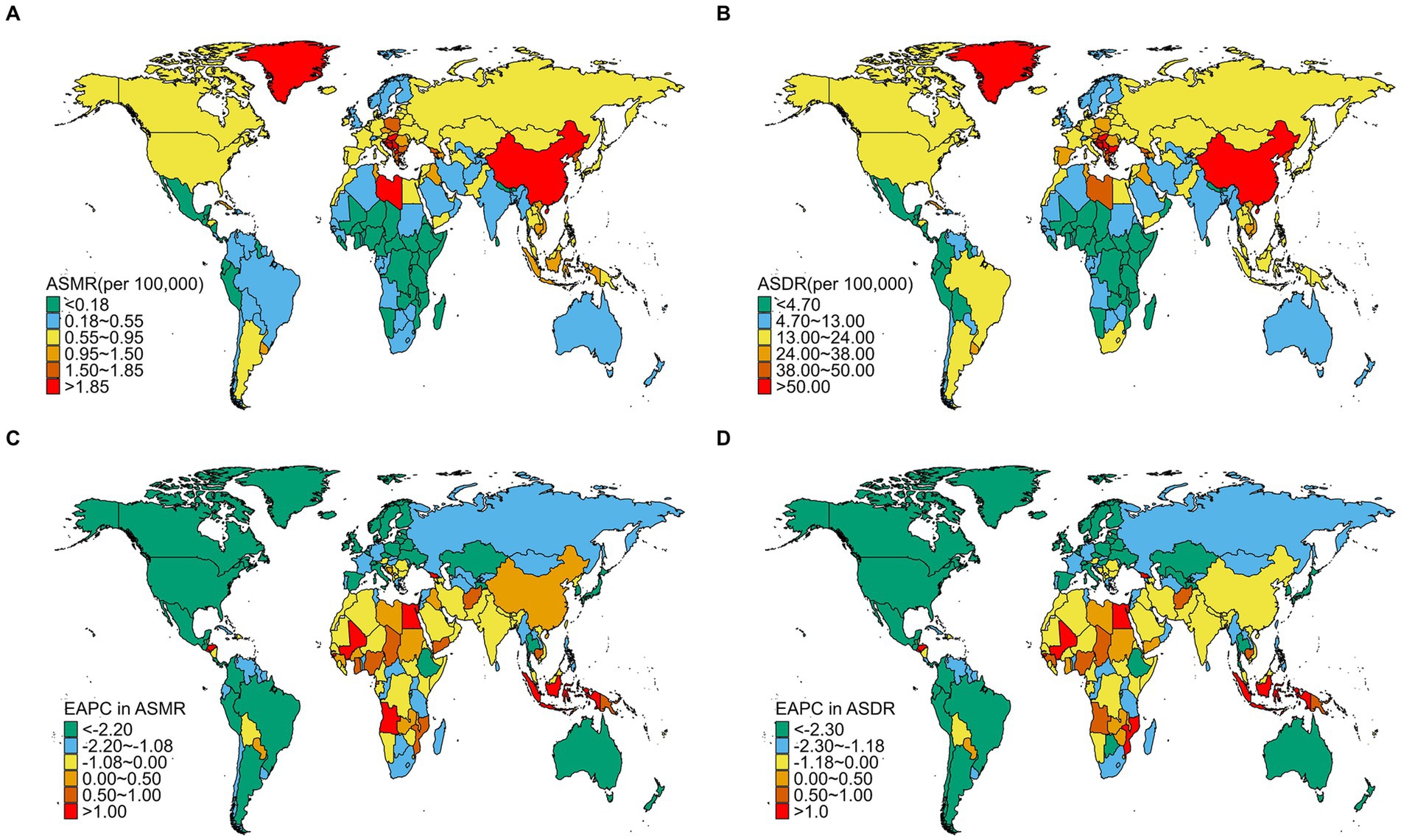

In 2021, significant disparities in the disease burden of TBL cancer attributable to SHS exposure were observed across national regions. The highest ASMR were recorded in Montenegro (3.45, 95% UI: 0.38 to 7.06), China (2.80, 95% UI: 0.35 to 5.27), and North Macedonia (2.55, 95% UI: 0.29 to 5.31) (Supplementary Table S1; Figure 1A). A similar distribution pattern was seen in the ASDR rates, with Montenegro (84.34, 95% UI: 9.36 to 170.96), China (63.32, 95% UI: 7.95 to 117.85), and North Macedonia (63.26, 95% UI: 7.03 to 132.65) reporting the highest burdens (Supplementary Table S1; Figure 1B). Conversely, the lowest burdens were predominantly observed in African regions, with Nigeria (0.02, 95% UI: 0.00 to 0.04), Kenya (0.04, 95% UI: 0.01 to 0.09), and Burundi (0.05, 95% UI: 0.01 to 0.11) reporting the lowest rates (Supplementary Table S1; Figure 1A). Between 1992 and 2021, most countries showed declining trends in both ASMR and ASDR rates, mainly in Western Europe and North America, such as the United Kingdom, Ireland, Denmark, Switzerland, the United States, Canada and Mexico (Supplementary Table S3; Supplementary Figure S2). In contrast, a few countries showed an upward trend mainly in Africa, such as Egypt, Lesotho, Guinea-Bissau, Mali, Mozambique, Angola, Georgia (Supplementary Table S3; Supplementary Figure S2). Developed nations typically demonstrated sustained improvements, whereas certain developing regions faced deteriorating conditions. Notably, some African countries consistently reported the lowest disease burdens, exemplified by Nigeria and Burundi. This pattern likely reflects limitations in disease surveillance and healthcare system capacities rather than genuinely lower disease burdens.

Figure 1. The spatial distribution of TBL cancer ASMR (A) and ASDR (B) attributable to SHS exposure in 2021, and the EAPC in TBL cancer ASMR (C) and ASDR (D) attributable to SHS exposure from1992 to 2021.

3.3 TBL cancer burden attributable to SHS exposure by sexes

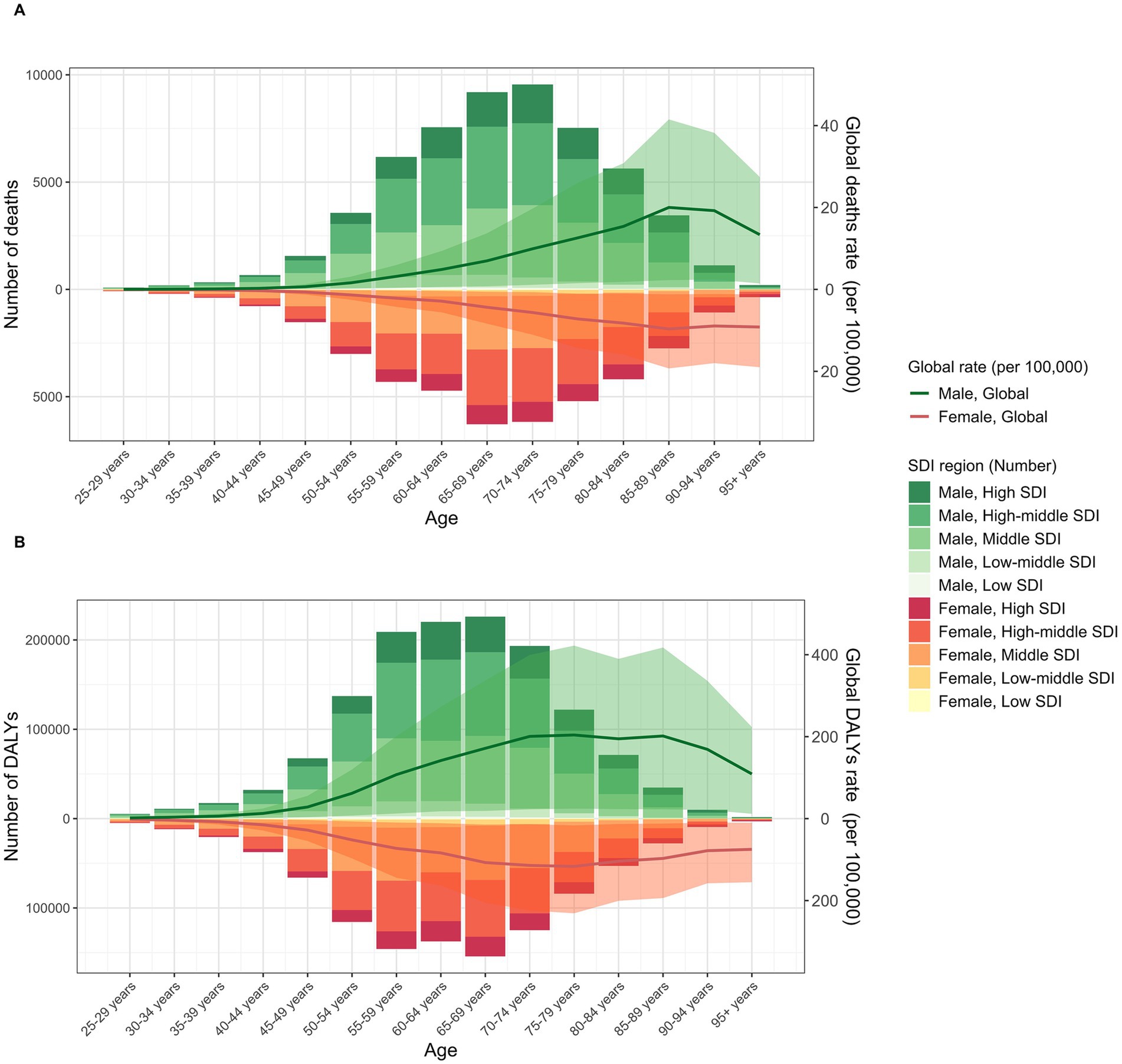

The disease burden of TBL cancer attributable to SHS exposure also shows significant differences between genders. Across both sexes, males consistently experienced a higher burden, with 56,848.1 deaths (95% UI: 6,655.0 to 109,070.9) and an ASMR of 1.44 (95% UI: 0.17 to 2.78) in 2021, compared to 41,062.7 deaths (95% UI: 5,535.9 to 78,059.2) and an ASMR of 0.89 (95% UI: 0.12 to 1.69) in females. Likewise, DALYs for males rose to 1,359,556.6 (95% UI: 158,640 to 2,596,453.4) with an ASDR of 32.88 (95% UI: 3.85 to 62.82), while DALYs for females reached 996,309.4 (95% UI: 135,988.2 to 1,907,079) with an ASDR of 21.81 (95% UI: 2.98 to 41.75) (Table 1). However, males showed greater improvement in age-standardized rates compared to females (EAPC in ASMR: −1.11 [95% CI: −1.19 to −1.03]; EAPC in ASDR: −1.51 [95% CI: −1.58 to −1.44]) (Table 1). Notably, TBL cancer deaths attributable to SHS exposure for both sexes followed a similar age pattern, increasing with age before gradually decreasing, predominantly concentrated in the 65–74 age group (Figure 2A). The burden of DALYs showed similar age and sex distribution patterns but peaked earlier at ages 65–69, with the primary burden concentrated in the 55–69 age group (Figure 2B). Notably, the disease burden was consistently higher in males than in females, a pattern that persisted across both developed and developing countries.

Figure 2. The burden of TBL cancer deaths (A) and DALYs (B) attributable to SHS exposure. The bars represent the number of TBL deaths and DALYs attributable to SHS exposure. The line with 95% UI represents ASMR and ASDR attributable to SHS exposure.

3.4 TBL cancer burden attributable to SHS exposure by SDI

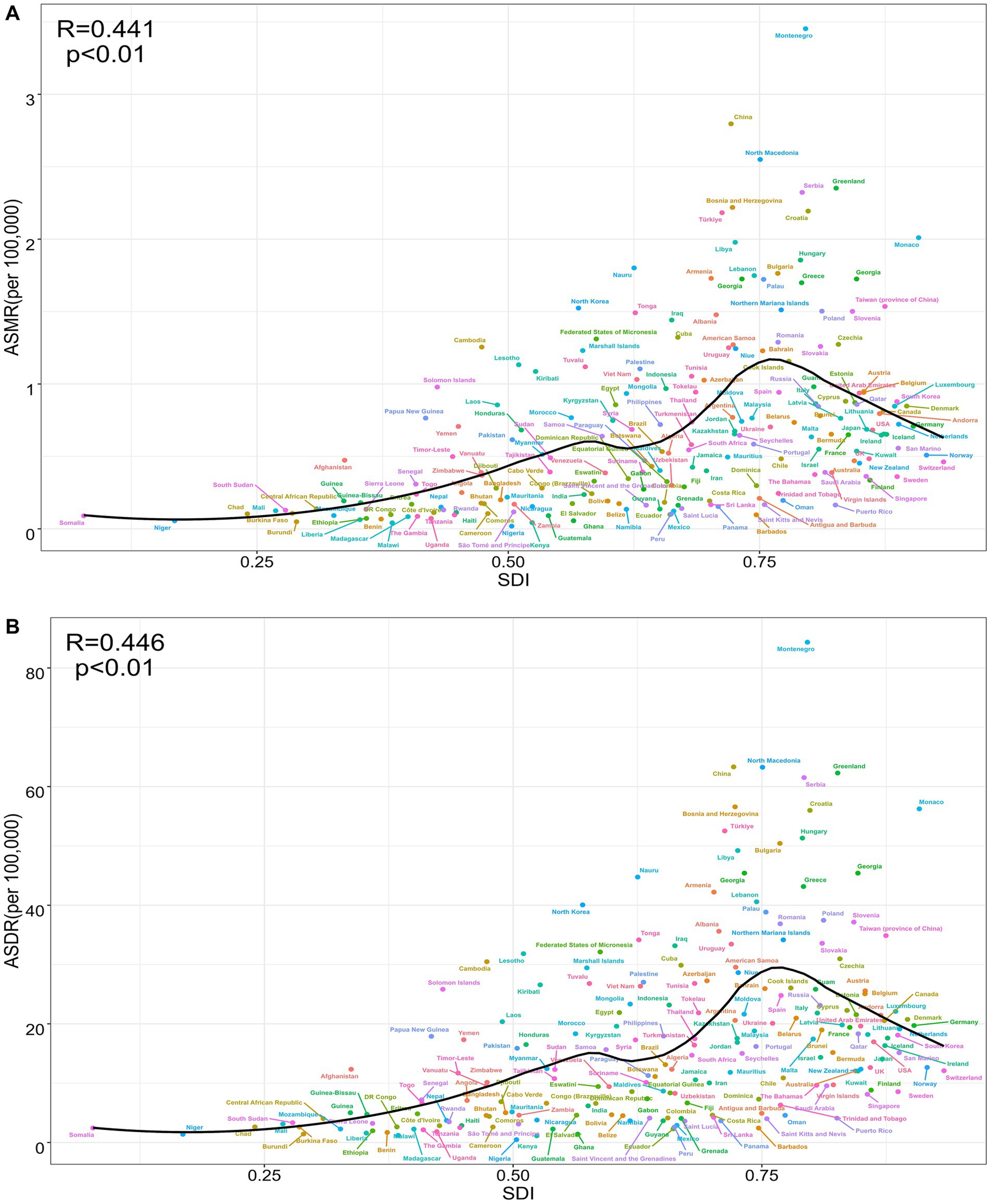

A national-level analysis in 2021 revealed a significant positive correlation between the ASMR of TBL cancer attributable to SHS exposure and the SDI (R = 0.441, p < 0.01) (Figure 3A). This relationship exhibited a distinct non-linear pattern: when SDI < 0.75, ASMR gradually increased with rising SDI; however, when SDI > 0.75, ASMR began to decline, forming an inverted U-shaped distribution. Significant geographical disparities were evident in the regional distribution. Several countries deviated notably from expected ASMR levels. Montenegro, China, North Macedonia, and Greenland exhibited substantially higher ASMR than anticipated based on their SDI. At the same time, many African countries — including Nigeria, Malawi, Kenya, and Burundi — demonstrated significantly lower ASMR compared to nations with similar SDI levels (Figure 3A). Notably, several high-SDI countries such as Switzerland, Sweden, Finland, and Singapore maintained relatively low ASMR levels (Figure 3A). The ASDR displayed distribution patterns highly consistent with ASMR, showing a significant positive correlation with SDI (R = 0.446, p < 0.01) and exhibiting the same inverted U-shaped trend (Figure 3B). This consistency not only reinforces the reliability of the findings but also underscores the complex relationship between the TBL cancer burden attributable to SHS exposure and socioeconomic development levels.

Figure 3. The correlation between TBL cancer attributable to SHS exposure in ASMR and SDI (R = 0.441, p < 0.01) (A), between TBL cancer attributable to SHS exposure in ASDR and SDI (R = 0.446, p < 0.01) (B).

3.5 APC analysis for TBL cancer burden attributable to SHS exposure

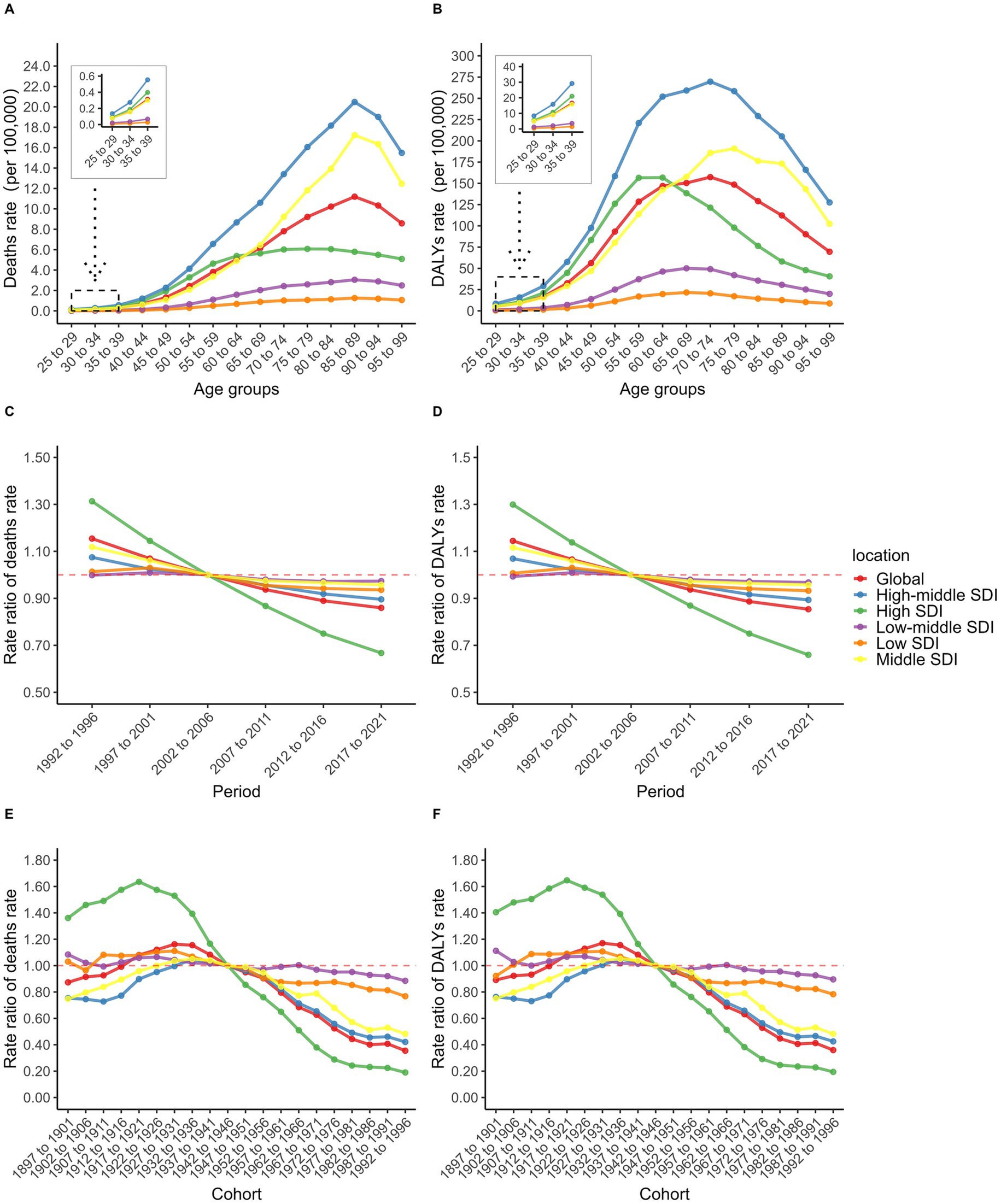

The age effect revealed significant heterogeneity across different SDI regions. The high-middle SDI region exhibited the highest death rates across all age groups, with a linear increase from ages 25–29 to 85–89, followed by a gradual decline (Figure 4A). This may be due to the fact that these two regions experienced decades of high smoking rates and SHS exposure, and the implementation of relevant tobacco control policies lagged behind that of High SDI regions. The middle SDI region and the global average displayed similar inverted V-shaped distributions, peaking at ages 85–89 before decreasing (Figure 4A). The high SDI region showed a distinct pattern: death rates increased gradually from ages 25–29 to 65–69 (second only to the high-middle SDI region), then stabilized and declined below the global average (Figure 4A). Notably, in the middle SDI region, the death rate surpassed both the high SDI region and the global average at ages 65–69, rising to the second-highest level. In contrast, the low-middle and low SDI regions showed gradual increases in death rates from ages 25–29 to 75–79, followed by relative stability, with the disease burden consistently remaining below the global level (Figure 4A).

Figure 4. Age-specific TBL cancer deaths rate (A) and DALYs rate (B); Period RR of TBL cancer deaths rate (C) and DALYs rate (D); Cohort RR of TBL cancer deaths rate (E) and DALYs rate (F) attributable to SHS exposure.

Sex-stratified analyses revealed notable differences, despite similar overall mortality patterns between males and females. In the high-middle SDI region, middle SDI region, and globally, male death rates peaked at ages 90–94 before declining rapidly (Supplementary Figure S5A). In contrast, female death rates peaked at 85–89, followed by an initial decline and then a secondary increase (Supplementary Figure S5B). Particularly in the high SDI region, male death rates remained relatively stable after ages 65–69, consistently staying below the global average (Supplementary Figure S5A). In comparison, female death rates began to fall below the global level from ages 55–59, displaying this trend approximately 10 years earlier than males (Supplementary Figure S5B). This may be due to female having less cumulative effects from SHS exposure than males.

Period effect analysis revealed an overall declining trend from 1992 to 2021. The high SDI region demonstrated the most substantial improvement, with the period rate ratio (RR) decreasing steadily from its peak in 1992–1996 to the lowest level in the most recent period (Figure 4C). Although other SDI regions also exhibited declining trends, their period RR values exceeded the global average after 2002–2006, particularly in the low-middle SDI region (Figure 4C). This region showed a progressive increase, rising from the lowest level in 1992–1996 to the highest level after 2002–2006 (Figure 4C). This may be related to the industrialization process and economic development. Notably, before 2002–2006, the high SDI region had the highest period RR among males (Supplementary Figure S5C), while the middle SDI region exhibited the highest period RR among females (Supplementary Figure S5D). After 2002–2006, period RR values in all SDI regions—except the high SDI region—exceeded the global average among females (Supplementary Figure S5D).

Cohort effect analysis showed that in the high SDI region, the cohort RR increased slightly between the 1897–1901 and 1917–1921 birth cohorts before declining, then decreased consistently from the highest to the lowest level after the 1942–1946 cohort (Figure 4E). This could be related to the development of medical and the improvement of people’s health awareness. The middle SDI and high-middle SDI regions, along with the global average, followed a similar trend, with brief increases from the 1897–1901 to 1932–1936 cohorts before gradually declining (Figure 4E). However, these regions maintained cohort RR values above the global average after 1942–1946 (Figure 4E). In contrast, the low-middle and low SDI regions showed minimal improvement in cohort RR, eventually surpassing other regions and the global average after 1942–1946 (Figure 4E). Sex disparities were most evident before the 1942–1946 cohort. Among males, the middle SDI region recorded the lowest cohort RR (Supplementary Figure S5E), while among females, the high-middle SDI region had the lowest (Supplementary Figure S5F). Importantly, the burden of DALYs from TBL cancer attributable to SHS exposure exhibited similar patterns to death rates across age, period, and cohort effects (Supplementary Figure S6).

3.6 ASMR projection for TBL cancer attributable to SHS exposure from 2022 to 2046

The ASMR for TBL cancer attributable to SHS exposure is projected to decline gradually from 2022 to 2046, with notable differences between sexes. In 2022, the overall ASMR is estimated at 1.12 (95% UI: 1.10 to 1.15), with significantly higher ASMR in men than in women (Figure 5). By 2046, the overall ASMR is expected to further decline to 0.90 (95% UI: 0.24 to 1.56), with the male ASMR projected to decrease to 1.03 (95% UI: 0.19 to 1.87) and the female ASMR is expected to decline to 0.85 (95% UI: 0.15 to 1.55) (Figure 5).

Figure 5. The temporal trends of ASMR in TBL cancer for both sexes (A), females (B), males (C) attributable to SHS exposure from 1992 to 2046. The solid line represents the observational values, while the dashed line shows the predicted values.

4 Discussion

Based on the GBD data, this research systematically evaluated the global disease burden of TBL cancer attributable to SHS exposure from 1992 to 2021. Through stratified analyses, we comprehensively investigated the evolving characteristics of this public health issue across multiple dimensions, including geographic regions, national development levels, and demographic variables (sex and age). The findings revealed that over the past 30 years, while the absolute number of deaths and DALYs due to SHS-attributable TBL cancer increased to varying degrees worldwide, both the ASMR and ASDR exhibited declining trends. These trends may be linked to global population growth and aging (31).

When examining disease burden trends from 1992 to 2021, marked heterogeneity was observed across SDI regions. The high SDI region achieved the most substantial progress over this period, with significant reductions in both absolute deaths and DALYs, as well as the fastest declines in ASMR and ASDR. This significant improvement is primarily attributed to several key factors: the implementation of comprehensive tobacco control programs (32–34), the widespread adoption of low-dose computed tomography (LDCT) screening (35) and increased health awareness (36). LDCT screening for individuals with long-term exposure to SHS environments can detect TBL cancer early and reduce TBL cancer mortality rates (37–40). The current increase in health awareness has also prompted people to advocate for the implementation of smoking cessation legislation (41–43). However, improvements in ASMR were relatively limited in low-middle and low SDI regions. Although some developing countries have begun to recognize the harmful risks of SHS exposure (44), these countries and regions lack the necessary resources for advanced diagnostic and treatment methods, and must balance multiple health threats within limited public health resources, making it difficult for TBL cancer prevention and treatment to receive adequate attention (45). Period and cohort effects further underscored the dynamic differences among SDI regions. In high SDI regions, early economic development was associated with increased smoking rates and limited awareness of SHS hazards, resulting in higher SHS exposure among earlier birth cohorts. However, in more recent periods, the intensity of SHS exposure and the associated TBL cancer burden declined due to improved health awareness, better access to healthcare, the implementation of smoking bans and cessation initiatives (27, 46, 47) and the implementation of the WHO Framework Convention on Tobacco Control (WHO FCTC). Conversely, later birth cohorts in low SDI regions may be experiencing increased SHS exposure due to industrialization, economic growth, rising tobacco use, and slower healthcare development (48–50). Notably, although current data indicate a relatively low disease burden in low SDI regions, this may be influenced by issues related to data availability and quality (51–53), necessitating cautious interpretation.

A national-level analysis in 2021 revealed that the top ten countries with the highest ASMR for TBL cancer attributable to SHS exposure were predominantly located in East Asia, Western Europe, and North America. This geographic distribution closely aligns with the historical patterns of tobacco use in these regions (45), reflecting the cumulative effects of long-term SHS exposure. Among them, European countries account for half, a phenomenon that deserves particular attention. Although both global ASMR and ASDR have shown declining trends over the past 30 years, indicating that the WHO Framework Convention on Tobacco Control (WHO FCTC) has made significant progress in reducing tobacco use since its implementation in 2003, Europe’s deeply entrenched social smoking culture continues to hinder the effective control of SHS exposure. In particular, the high social acceptance of smoking in public and social settings contributes to persistent SHS exposure, thereby exacerbating the population-level burden of TBL cancer (54). China, as the world’s largest consumer of tobacco (8), ranks second globally in ASMR for TBL cancer attributable to SHS exposure. Although China has ratified the WHO FCTC, it has yet to enact national smoke-free legislation prohibiting smoking in public places and workplaces (55). Previous research has shown that over 70% of adult males and 50 to 60% of adult females in China are exposed to SHS in the home and workplace environments (56). Therefore, multidimensional intervention strategies are urgently needed to reduce the disease burden of TBL cancer. In addition to enhancing smoking cessation services and improving healthcare accessibility, raising public awareness about the health hazards of SHS is crucial. Meta-analyses have shown that lifelong non-smokers living with smokers face a 20 to 30% higher risk of developing TBL cancer compared to those without SHS exposure—a finding that warrants serious attention (57, 58).

Stratified analysis by sex revealed significant sex disparities in the disease burden of TBL cancer attributable to SHS exposure. This disparity can be interpreted through three key dimensions. First, it may relate to differences in smoking prevalence, with higher smoking rates among males resulting in greater SHS exposure for men in both social and occupational settings. Second, although females generally have lower smoking rates, their proportion as passive smokers is substantial. Global data indicate that 35% of non-smoking women are regularly exposed to SHS (51), particularly in domestic settings (59). This pattern of chronic, low-dose exposure may explain why the SHS-related TBL cancer burden remains significant among females despite their lower active smoking rates. Third, women may exhibit heightened biological sensitivity to certain tobacco-related carcinogens, potentially due to a greater susceptibility to p53 and K-RAS gene mutations, as well as interactions between tobacco carcinogens and estrogen (14, 60). These molecular-level differences may help explain why females could face elevated carcinogenic risks even at comparable exposure levels. Nevertheless, in terms of observed disease burden, males demonstrate significantly higher levels than females, both in absolute numbers and age-standardized rates.

This study revealed a significant non-linear association between the disease burden of TBL cancer attributable to SHS exposure and the SDI, demonstrating a characteristic inverse U-shaped relationship. This pattern may be explained by the similarly shaped relationship between smoking prevalence and socioeconomic development (61). At the low SDI stage, limited economic development restricts access to tobacco products, resulting in lower smoking prevalence and, consequently, relatively low levels of SHS exposure within the population. In the middle SDI stage, rapid economic growth is often accompanied by a substantial rise in tobacco consumption. However, due to underdeveloped tobacco control policies and lagging public health regulations, the risks of SHS exposure increase significantly. Finally, at the high SDI stage, greater awareness of the health hazards of smoking and SHS exposure, combined with improved public health consciousness and the implementation of stricter tobacco control measures, leads to a decline in the disease burden. Based on these findings, countries at the middle SDI level should prioritize strengthening health education and implementing tobacco taxation and control policies to help reduce the burden of SHS-attributable TBL cancer.

Predictive modeling indicates a declining trend in the ASMR for TBL cancer attributable to SHS exposure. This decline is largely due to the implementation of multi-level tobacco control interventions worldwide, including tobacco taxation, packaging regulations, and anti-tobacco media campaigns (62–64). However, with approximately 37% of the global population still exposed to SHS environments (65), and this study reporting 97,910 SHS-attributable TBL cancer deaths and 2,355,866 DALYs in 2021, SHS exposure remains a critical public health challenge that requires continued and targeted intervention.

Four key recommendations emerge for addressing this issue. First, for middle SDI regions, strengthening smoke-free environment policies: bans on indoor and workplace smoking can significantly reduce SHS exposure, with particular emphasis on indoor smoking restrictions, as indoor exposure rates often exceed workplace exposure due to the amount of time people spend indoors. Second, optimizing TBL cancer screening strategies: incorporating SHS exposure into screening criteria could enhance early detection rates, though implementation should be region-specific. High SDI regions could integrate SHS exposure into existing low-dose computed tomography (LDCT) screening programs; middle SDI regions might adopt stratified screening approaches prioritizing high-risk populations; and low SDI regions, given resource constraints, should prioritize cost-effective preventive measures such as robust tobacco control programs or improved indoor ventilation systems to reduce SHS exposure. Third, for low SDI regions, enhancing risk communication: increasing public awareness about the health risks of SHS exposure, especially concerning vulnerable groups such as pregnant women and children (66–69), is essential for promoting health-conscious behaviors and reducing long-term disease burden. Fourth, we recommend adopting the theoretical framework of a “life-course strategy” (70). During childhood and adolescence, emphasis should be placed on promoting awareness of the harms of SHS exposure and fostering healthy behavioral consciousness. During the middle-aged population stage, tobacco control management in workplaces and public environments should be strengthened. In the older adult stage, TBL screening and health monitoring should be enhanced.

This study is the first to describe and explore long-term trends in the disease burden of TBL cancer attributable to SHS by age, gender, location, and SDI, utilizing APC and BAPC models. It fills an important research gap in this field, which represents a unique contribution of our study. However, several limitations should be acknowledged. First, the accuracy and robustness of GBD estimates heavily depend on the quality and completeness of input data used for modeling. GBD2021 did not include TBL data from SHS exposure for populations under 25 years of age, and the indicators for SHS exposure do not include new tobacco products such as e-cigarettes or secondhand aerosols (71). This may have led us to underestimate the disease burden trends of TBL caused by SHS exposure, and future research should further incorporate monitoring and assessment of such exposures. Moreover, in low SDI regions and sparsely populated countries, systematic underreporting may occur due to inadequate disease surveillance and vital registration systems. Consequently, trend analyses for these regions should be interpreted with caution and validated by future research. Second, our research findings are based on ecological data. In analyzing the non-linear association between TBL cancer burden attributable to SHS exposure and the SDI, we calculated simple linear Pearson correlation coefficients, which may not accurately reflect the true strength of non-linear relationships. Moreover, we did not employ multivariable ecological models to adjust for other potential confounding factors (such as indoor air pollution, dietary factors, genetic factors, etc.) and measurement heterogeneity that could impact TBL cancer outcomes. Furthermore, our predictions of disease burden trends are based on the assumption that risk factor exposure trends remain unchanged; however, this assumption may no longer hold if new tobacco control measures are introduced. We anticipate that these issues can be addressed in future research. Finally, the lag effect of interventions may influence our assessment of the effectiveness of current prevention and control measures. Although many countries have implemented tobacco control policies, the full population-level health benefits of these interventions may take time to be reflected in disease burden data. Despite these limitations, a key strength of the GBD study framework lies in its regular update mechanism. With ongoing improvements in data availability and methodology, future estimates will more accurately capture dynamic changes in the global burden of SHS-related TBL cancer. We look forward to future studies that conduct comparative risk assessments between SHS and other TBL risk factors (such as indoor air pollution, outdoor particulate matter, etc.), or evaluate the cost-effectiveness of specific SHS intervention measures under different environmental conditions.

Data availability statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/Supplementary material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Ethics statement

The data used in this study were obtained from the Global Burden of Disease (GBD) Study database. The GBD study data followed the guidelines for Accurate and Transparent Health Estimation Reporting for Population Health Research (GATHER). Since GBD information is entirely anonymized and does not include personal data, this analysis did not require approval from a research ethics committee.

Author contributions

H-mL: Writing – original draft. BL: Writing – original draft. X-pL: Writing – original draft, Methodology. HH: Writing – original draft, Data curation. X-tC: Writing – original draft, Data curation. X-bZ: Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declare that no financial support was received for the research and/or publication of this article.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Editage (www.editage.cn) for English language editing.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The authors declare that no Gen AI was used in the creation of this manuscript.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Supplementary material

The Supplementary material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fpubh.2025.1625876/full#supplementary-material

Footnotes

References

1. Bray, F, Laversanne, M, Sung, H, Ferlay, J, Siegel, RL, Soerjomataram, I, et al. Global cancer statistics 2022: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA Cancer J Clin. (2024) 74:229–63. doi: 10.3322/caac.21834

2. Bizuayehu, HM, Ahmed, KY, Kibret, GD, Dadi, AF, Belachew, SA, Bagade, T, et al. Global disparities of Cancer and its projected burden in 2050. JAMA Netw Open. (2024) 7:e2443198. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2024.43198

3. LoPiccolo, J, Gusev, A, Christiani, DC, and Jänne, PA. Lung cancer in patients who have never smoked — an emerging disease. Nat Rev Clin Oncol. (2024) 21:121–46. doi: 10.1038/s41571-023-00844-0

4. Samet, JM, Avila-Tang, E, Boffetta, P, Hannan, LM, Olivo-Marston, S, Thun, MJ, et al. Lung cancer in never smokers: clinical epidemiology and environmental risk factors. Clin Cancer Res. (2009) 15:5626–45. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-09-0376

5. Khoramdad, M, Vahedian-Azimi, A, Karimi, L, Rahimi-Bashar, F, Amini, H, and Sahebkar, A. Association between passive smoking and cardiovascular disease: a systematic review and meta-analysis. IUBMB Life. (2020) 72:677–86. doi: 10.1002/iub.2207

6. Kaur, J, Upendra, S, and Barde, S. Inhaling hazards, exhaling insights: a systematic review unveiling the silent health impacts of secondhand smoke pollution on children and adolescents. Int J Environ Health Res. (2024) 34:4059–73. doi: 10.1080/09603123.2024.2337837

7. Kim, AS, Ko, HJ, Kwon, JH, and Lee, JM. Exposure to secondhand smoke and risk of Cancer in never smokers: a Meta-analysis of epidemiologic studies. Int J Environ Res Public Health. (2018) 15:1981. doi: 10.3390/ijerph15091981

8. GBD 2019 Tobacco Collaborators. Spatial, temporal, and demographic patterns in prevalence of smoking tobacco use and attributable disease burden in 204 countries and territories, 1990–2019: a systematic analysis from the global burden of disease study 2019. Lancet. (2021) 397:2337–60. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(21)01169-7

9. Mbulo, L, Palipudi, KM, Andes, L, Morton, J, Bashir, R, Fouad, H, et al. Secondhand smoke exposure at home among one billion children in 21 countries: findings from the global adult tobacco survey (GATS). Tob Control. (2016) 25:e95–e100. doi: 10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2015-052693

10. GBD 2016 Risk Factors Collaborators. Global, regional, and national comparative risk assessment of 84 behavioural, environmental and occupational, and metabolic risks or clusters of risks, 1990-2016: a systematic analysis for the global burden of disease study 2016. Lancet. (2017) 390:1345–422. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(17)32366-8

11. IARC Working Group on the Evaluation of Carcinogenic Risks to Humans. Tobacco smoke and involuntary smoking. IARC Monogr Eval Carcinog Risks Hum. (Lyon: IARC Press). (2004) 83.

12. Li, Y, and Hecht, SS. Carcinogenic components of tobacco and tobacco smoke: a 2022 update. Food Chem Toxicol. (2022) 165:113179. doi: 10.1016/j.fct.2022.113179

13. Weeden, CE, Hill, W, Lim, EL, Grönroos, E, and Swanton, C. Impact of risk factors on early cancer evolution. Cell. (2023) 186:1541–63. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2023.03.013

14. Izzotti, A, and Pulliero, A. Molecular damage and lung tumors in cigarette smoke-exposed mice. Ann N Y Acad Sci. (2015) 1340:75–83. doi: 10.1111/nyas.12697

15. Izzotti, A, Cartiglia, C, Longobardi, M, Bagnasco, M, Merello, A, You, M, et al. Gene expression in the lung of p53 mutant mice exposed to cigarette smoke. Cancer Res. (2004) 64:8566–72. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-04-1420

16. Law, MR, and Hackshaw, AK. Environmental tobacco smoke. Br Med Bull. (1996) 52:22–34. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.bmb.a011528

17. Sun, S, Schiller, JH, and Gazdar, AF. Lung cancer in never smokers--a different disease. Nat Rev Cancer. (2007) 7:778–90. doi: 10.1038/nrc2190

18. Possenti, I, Romelli, M, Carreras, G, Biffi, A, Bagnardi, V, Specchia, C, et al. Association between second-hand smoke exposure and lung cancer risk in never-smokers: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur Respir Rev. (2024) 33:240077. doi: 10.1183/16000617.0077-2024

19. Yang, X, Man, J, Chen, H, Zhang, T, Yin, X, He, Q, et al. Temporal trends of the lung cancer mortality attributable to smoking from 1990 to 2017: a global, regional and national analysis. Lung Cancer. (2021) 152:49–57. doi: 10.1016/j.lungcan.2020.12.007

20. Yang, X, Zhang, T, Zhang, X, Chu, C, and Sang, S. Global burden of lung cancer attributable to ambient fine particulate matter pollution in 204 countries and territories, 1990-2019. Environ Res. (2022) 204:112023. doi: 10.1016/j.envres.2021.112023

21. Zhang, Y, Mi, M, Zhu, N, Yuan, Z, Ding, Y, Zhao, Y, et al. Global burden of tracheal, bronchus, and lung cancer attributable to occupational carcinogens in 204 countries and territories, from 1990 to 2019: results from the global burden of disease study 2019. Ann Med. (2023) 55:2206672. doi: 10.1080/07853890.2023.2206672

22. Rushton, L, Hutchings, SJ, Fortunato, L, Young, C, Evans, GS, Brown, T, et al. Occupational cancer burden in Great Britain. Br J Cancer. (2012) 107:S3–7. doi: 10.1038/bjc.2012.112

23. Cheng, ES, Weber, M, Steinberg, J, and Yu, XQ. Lung cancer risk in never-smokers: an overview of environmental and genetic factors. Chin J Cancer Res. (2021) 33:548–62. doi: 10.21147/j.issn.1000-9604.2021.05.02

24. GBD 2021 Causes of Death Collaborators. Global burden of 288 causes of death and life expectancy decomposition in 204 countries and territories and 811 subnational locations, 1990-2021: a systematic analysis for the global burden of disease study 2021. Lancet. (2024) 403:2100–32. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(24)00367-2

25. GBD 2017 Disease and Injury Incidence and Prevalence Collaborators. Global, regional, and national incidence, prevalence, and years lived with disability for 354 diseases and injuries for 195 countries and territories, 1990–2017: a systematic analysis for the global burden of disease study 2017. Lancet. (2018) 392:1789–858. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(18)32279-7

26. Zhai, C, Hu, D, Yu, G, Hu, W, Zong, Q, Yan, Z, et al. Global, regional, and national deaths, disability-adjusted life years, years lived with disability, and years of life lost for the global disease burden attributable to second-hand smoke, 1990-2019: a systematic analysis for the global burden of disease study. Sci Total Environ. (2023) 862:160677. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2022.160677

27. GBD 2019 Risk Factors Collaborators. Global burden of 87 risk factors in 204 countries and territories, 1990–2019: a systematic analysis for the global burden of disease study 2019. Lancet. (2020) 396:1223–49. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30752-2

28. Rosenberg, PS, Check, DP, and Anderson, WF. A web tool for age-period-cohort analysis of cancer incidence and mortality rates. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. (2014) 23:2296–302. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-14-0300

29. Riebler, A, and Held, L. Projecting the future burden of cancer: Bayesian age-period-cohort analysis with integrated nested Laplace approximations. Biom J. (2017) 59:531–49. doi: 10.1002/bimj.201500263

30. Knoll, M, Furkel, J, Debus, J, Abdollahi, A, Karch, A, and Stock, C. An R package for an integrated evaluation of statistical approaches to cancer incidence projection. BMC Med Res Methodol. (2020) 20:257. doi: 10.1186/s12874-020-01133-5

31. Miller, KD, Nogueira, L, Devasia, T, Mariotto, AB, Yabroff, KR, Jemal, A, et al. Cancer treatment and survivorship statistics, 2022. CA Cancer J Clin. (2022) 72:409–36. doi: 10.3322/caac.21731

32. Mojtabai, R, Riehm, KE, Cohen, JE, Alexander, GC, and Rutkow, L. Clean indoor air laws, cigarette excise taxes, and smoking: results from the current population survey-tobacco use supplement, 2003–2011. Prev Med. (2019) 126:105744. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2019.06.002

33. Chaloupka, FJ, Yurekli, A, and Fong, GT. Tobacco taxes as a tobacco control strategy. Tob Control. (2012) 21:172–80. doi: 10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2011-050417

34. Stevenson, L, Campbell, S, Bohanna, I, Gould, GS, Robertson, J, and Clough, AR. Establishing smoke-free homes in the indigenous populations of Australia, New Zealand, Canada and the United States: a systematic literature review. Int J Environ Res Public Health. (2017) 14:1382. doi: 10.3390/ijerph14111382

35. Tomonaga, Y, Ten Haaf, K, Frauenfelder, T, Kohler, M, Kouyos, RD, Shilaih, M, et al. Cost-effectiveness of low-dose CT screening for lung cancer in a European country with high prevalence of smoking-a modelling study. Lung Cancer. (2018) 121:61–9. doi: 10.1016/j.lungcan.2018.05.008

36. Brownson, RC, Eriksen, MP, Davis, RM, and Warner, KE. Environmental tobacco smoke: health effects and policies to reduce exposure. Annu Rev Public Health. (1997) 18:163–85. doi: 10.1146/annurev.publhealth.18.1.163

37. The International Early Lung Cancer Action Program Investigators. Survival of patients with stage I lung cancer detected on CT screening. N Engl J Med. (2006) 355:1763–71. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa060476

38. National Lung Screening Trial Research Team. Reduced lung-cancer mortality with low-dose computed tomographic screening. Massachusetts Medical Society. N Engl J Med. (2011) 365:395–409. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1102873

39. Yu, H, Wang, Y, Yue, X, and Zhang, H. Influence of the atmospheric environment on spatial variation of lung cancer incidence in China. PLoS One. (2024) 19:e0305345. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0305345

40. Detterbeck, FC, Mazzone, PJ, Naidich, DP, and Bach, PB. Screening for lung cancer. Chest. (2013) 143:e78S–92S. doi: 10.1378/chest.12-2350

41. National Association for Public Health Policy. Finding common ground: how public health can work with organized labor to protect workers from environmental tobacco smoke. J Public Health Policy. (1997) 18:453–64. doi: 10.2307/3343524

42. Jones, S, Love, C, Thomson, G, Green, R, and Howden-Chapman, P. Second-hand smoke at work: the exposure, perceptions and attitudes of bar and restaurant workers to environmental tobacco smoke. Aust N Z J Public Health. (2001) 25:90–3. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-842X.2001.tb00557.x

43. Brownson, RC, Hopkins, DP, and Wakefield, MA. Effects of smoking restrictions in the workplace. Annu Rev Public Health. (2002) 23:333–48. doi: 10.1146/annurev.publhealth.23.100901.140551

44. Owusu-Dabo, E, Lewis, S, McNeill, A, Gilmore, A, and Britton, J. Support for smoke-free policy, and awareness of tobacco health effects and use of smoking cessation therapy in a developing country. BMC Public Health. (2011) 11:572. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-11-572

45. Deng, Y, Zhao, P, Zhou, L, Xiang, D, Hu, J, Liu, Y, et al. Epidemiological trends of tracheal, bronchus, and lung cancer at the global, regional, and national levels: a population-based study. J Hematol Oncol. (2020) 13:98. doi: 10.1186/s13045-020-00915-0

46. GBD 2016 Healthcare Access and Quality Collaborators. Measuring performance on the healthcare access and quality index for 195 countries and territories and selected subnational locations: a systematic analysis from the global burden of disease study 2016. Lancet. (2018) 391:2236–71. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(18)30994-2

47. Chung-Hall, J, Craig, L, Gravely, S, Sansone, N, and Fong, GT. Impact of the WHO FCTC over the first decade: a global evidence review prepared for the impact assessment expert group. Tob Control. (2019) 28:s119–28. doi: 10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2018-054389

48. Nazar, GP, Lee, JT, Arora, M, and Millett, C. Socioeconomic inequalities in secondhand smoke exposure at home and at work in 15 low- and middle-income countries. Nicotine Tob Res. (2016) 18:1230–9. doi: 10.1093/ntr/ntv261

49. Bilano, V, Gilmour, S, Moffiet, T, d’Espaignet, ET, Stevens, GA, Commar, A, et al. Global trends and projections for tobacco use, 1990-2025: an analysis of smoking indicators from the WHO comprehensive information systems for tobacco control. Lancet. (Elsevier) (2015) 385:966–76. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(15)60264-1

50. GBD 2015 Tobacco Collaborators. Smoking prevalence and attributable disease burden in 195 countries and territories, 1990–2015: a systematic analysis from the global burden of disease study 2015. Lancet. (2017) 389:1885–906. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(17)30819-X

51. Öberg, M, Jaakkola, MS, Woodward, A, Peruga, A, and Prüss-Ustün, A. Worldwide burden of disease from exposure to second-hand smoke: a retrospective analysis of data from 192 countries. Lancet. (2011) 377:139–46. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(10)61388-8

52. Zhang, D, Liu, S, Li, Z, Shen, M, Li, Z, and Wang, R. Burden of gastrointestinal cancers among adolescent and young adults in Asia-Pacific region: trends from 1990 to 2019 and future predictions to 2044. Ann Med. (2024). 56:2427367. doi: 10.1080/07853890.2024.2427367

53. GBD Chronic Respiratory Disease Collaborators. Prevalence and attributable health burden of chronic respiratory diseases, 1990-2017: a systematic analysis for the global burden of disease study 2017. Lancet Respir Med. (2020) 8:585–96. doi: 10.1016/S2213-2600(20)30105-3

54. Stefler, D, Murphy, M, Irdam, D, Horvat, P, Jarvis, M, King, L, et al. Smoking and mortality in Eastern Europe: results from the PrivMort retrospective cohort study of 177 376 individuals. Nicotine Tob Res. (2018) 20:749–54. doi: 10.1093/ntr/ntx122

55. Wang, N, Xu, Z, Lui, CW, Wang, B, Hu, W, and Wu, J. Age-period-cohort analysis of lung cancer mortality in China and Australia from 1990 to 2019. Sci Rep. (2022) 12:8410. doi: 10.1038/s41598-022-12483-z

56. Katanoda, K, Jiang, Y, Park, S, Lim, MK, Qiao, YL, and Inoue, M. Tobacco control challenges in East Asia: proposals for change in the world’s largest epidemic region. Tob Control. (2014) 23:359–68. doi: 10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2012-050852

57. Hori, M, Tanaka, H, Wakai, K, Sasazuki, S, and Katanoda, K. Secondhand smoke exposure and risk of lung cancer in Japan: a systematic review and meta-analysis of epidemiologic studies. Jpn J Clin Oncol. (2016) 46:942–51. doi: 10.1093/jjco/hyw091

58. Mochizuki, A, Shiraishi, K, Honda, T, Higashiyama, RI, Sunami, K, Matsuda, M, et al. Passive smoking-induced mutagenesis as a promoter of lung carcinogenesis. J Thorac Oncol. (2024) 19:984–94. doi: 10.1016/j.jtho.2024.02.006

59. Du, Y, Cui, X, Sidorenkov, G, Groen, HJM, Vliegenthart, R, Heuvelmans, MA, et al. Lung cancer occurrence attributable to passive smoking among never smokers in China: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Transl Lung Cancer Res. (2020) 9:204–17. doi: 10.21037/tlcr.2020.02.11

60. Stapelfeld, C, Dammann, C, and Maser, E. Sex-specificity in lung cancer risk. Int J Cancer. (2020) 146:2376–82. doi: 10.1002/ijc.32716

61. Lopez, AD, Collishaw, NE, and Piha, T. A descriptive model of the cigarette epidemic in developed countries. Tob Control. (1994) 3:242–7. doi: 10.1136/tc.3.3.242

62. Wise, J. Government considers outdoor smoking ban in England. BMJ. (2024) 30:q1908. doi: 10.1136/bmj.q1908

63. Hoffman, SJ, and Tan, C. Overview of systematic reviews on the health-related effects of government tobacco control policies. BMC Public Health. (2015) 15:744. doi: 10.1186/s12889-015-2041-6

64. Printz, C. New smoke-free Laws and Increased tobacco taxes would have Nationwide impact. Cancer. (2011) 117:5247–7. doi: 10.1002/cncr.26672

65. Flor, LS, Anderson, JA, Ahmad, N, Aravkin, A, Carr, S, Dai, X, et al. Health effects associated with exposure to secondhand smoke: a burden of proof study. Nat Med. (2024) 30:149–67. doi: 10.1038/s41591-023-02743-4

66. Leonardi-Bee, J, Britton, J, and Venn, A. Secondhand smoke and adverse fetal outcomes in nonsmoking pregnant women: a meta-analysis. Pediatrics. (2011) 127:734–41. doi: 10.1542/peds.2010-3041

67. den Dekker, HT, AMMS, V, de Jongste, JC, Reiss, IK, Hofman, A, Jaddoe, VWV, et al. Tobacco smoke exposure, airway resistance, and asthma in school-age children: the generation R study. Chest. (2015) 148:607–17. doi: 10.1378/chest.14-1520

68. Johansson, E, Martin, LJ, He, H, Chen, X, Weirauch, MT, Kroner, JW, et al. Second-hand smoke and NFE2L2 genotype interaction increases paediatric asthma risk and severity. Clin Exp Allergy. (2021) 51:801–10. doi: 10.1111/cea.13815

69. Vineis, P, Airoldi, L, Veglia, F, Olgiati, L, Pastorelli, R, Autrup, H, et al. Environmental tobacco smoke and risk of respiratory cancer and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease in former smokers and never smokers in the EPIC prospective study. BMJ. (2005) 330:277. doi: 10.1136/bmj.38327.648472.82

70. Saleem, SM, and Bhattacharya, S. Reducing the infectious diseases burden through “life course approach vaccination” in India—a perspective. AIMS Public Health. (2021) 8:553–62. doi: 10.3934/publichealth.2021045

Keywords: second-hand smoke (SHS), tracheal, bronchus, and lung (TBL) cancer, Global Burden of Disease(GBD), age-standardized mortality rate (ASMR), age-standardized DALY rate (ASDR), estimated annual percentage change (EAPC)

Citation: Lin H-m, Lin B, Liao X-p, Hong H, Cai X-t and Zhuang X-b (2025) Global burden of tracheal, bronchus, and lung cancer attributable to second-hand smoke exposure from 1992 to 2021: an age-period-cohort analysis and 25-year mortality projections. Front. Public Health. 13:1625876. doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2025.1625876

Edited by:

Xinming Wang, Chinese Academy of Sciences (CAS), ChinaReviewed by:

Yanfeng Gong, Fudan University, ChinaOm Prakash Bera, Global Health Advocacy Incubator, India

Paolo Scanagatta, ASST Valtellina e Alto Lario, Italy

Copyright © 2025 Lin, Lin, Liao, Hong, Cai and Zhuang. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Xi-bin Zhuang, enhicXpAMTYzLmNvbQ==

†These authors have contributed equally to this work

Hong-ming Lin1†

Hong-ming Lin1† Xi-bin Zhuang

Xi-bin Zhuang