- 1Dipartimento di Sanità Pubblica, Università degli Studi di Napoli Federico II, Napoli, Italy

- 2Dipartimento di Medicina Clinica e Chirurgia, Università degli Studi di Napoli Federico II, Napoli, Italy

- 3Dipartimento di Studi Umanistici, Università degli Studi di Napoli Federico II, Napoli, Italy

- 4Dipartimento di Architettura, Università degli Studi di Napoli Federico II, Napoli, Italy

- 5Dipartimento di Neuroscienze e Scienze Riproduttive ed Odontostomatologiche, Università degli Studi di Napoli Federico II, Napoli, Italy

- 6Centro Italiano per la Cura e il Benessere del Paziente con Obesità (C.I.B.O), Azienda Ospedaliera Universitaria Federico II, Napoli, Italy

- 7Dipartimento di Benessere, Nutrizione e Sport, Università Telematica Pegaso, Napoli, Italy

- 8Dipartimento di Farmacia, Università degli Studi di Napoli Federico II, Napoli, Italy

Background: Frailty and multimorbidity in older adults require integrated, multidomain care models. Digital health solutions offer potential for improving self-management, but a structured methodology to translate the complex unmet needs of this population into tailored digital interventions is still lacking.

Objectives: To propose and illustrate a mixed-methods, persona-based approach for mapping unmet needs of older adults with multimorbidity to candidate digital interventions.

Methods: This study employed an explanatory sequential mixed-methods design. First, quantitative data from the SUNFRAIL+ frailty screening tool were analyzed for a sub-cohort of community-dwelling older adults with polypharmacy (n = 54). These findings informed a qualitative phase conducted through a multidisciplinary Focus Group (FG) of 15 healthcare and social care experts. FG transcripts were thematically analyzed to identify unmet needs across clinical, psychological, social, and environmental domains. These insights were synthesized using the European Commission’s Blueprint methodology to create a realistic persona, “Gennaro,” representing common challenges. Finally, the FG systematically mapped potential digital solutions to address the identified needs. We descriptively profiled a polypharmacy subgroup (n = 54) from the F2UH site of the multicentre SUNFRAIL+ study; no hypothesis testing was performed.

Results: SUNFRAIL+ data revealed a high prevalence of perceived memory loss (44.4%), reduced physical activity (40.7%), loneliness (29.6%), and gaps in primary care access (25.9%). Thematic analysis highlighted unmet needs in medication management, motivation for lifestyle change, social isolation, and environmental barriers. The persona “Gennaro” embodied these challenges, facilitating the identification of targeted digital solutions, including Shared Care Plans, Telemonitoring, smart pillboxes for Medication Adherence, Adapted Physical Activity programs, Motivational Interviewing apps, and Ambient Assisted Living (AAL) systems. A foundational dataset and interoperability requirements for implementation were also defined.

Conclusion: This descriptive, hypothesis-generating study integrates quantitative screening and multidisciplinary expert insights to propose a structured, persona-guided approach for profiling the multifaceted unmet needs of older adults with multimorbidity. We outline candidate digital options mapped to specific challenges as a preliminary framework to hypothesize person-centered, digitally supported care models. End-user co-design and validation are planned next to evaluate feasibility, usability, acceptability, and potential impact on self-management and adherence.

1 Introduction

Multimorbidity, defined as the coexistence of more than one chronic condition in a single individual (1), is increasingly common in older adults, with prevalence >75% after 65 years (2). Its prevalence increases with age, exhibits gender disparities (3), and is a global phenomenon observed in both high- and low-income countries (4). Frailty, an age-related multifactorial condition, increases the risk of hospitalization, disability and death (5). It frequently coexists with multimorbidity (6) and contributes to reduced quality of life and mortality mainly from cardiovascular, oncological, respiratory and metabolic diseases.

Older adults with multimorbidity, especially when frail, show frequent hospitalizations and require complex, structured care plans that address overall health beyond single-disease management (7–9). Therapeutic adherence is a key determinant in managing multimorbidity and polypharmacy: low adherence worsens quality of life and increases costs, while effective interventions must be tailored to individual and contextual risk factors (10–12).

Given that frailty and multimorbidity affect nearly half of the older population (46.2%), early diagnosis, prevention, and integrated management are healthcare priorities to sustain healthcare systems and improve self-management (13). Managing multiple chronic diseases requires sustained psychological adaptation and coping skills (14–16). Social relationships and socioeconomic conditions are equally crucial, as disadvantage and barriers in access to services increase health disparities and vulnerability in older adults (17–20). Addressing multimorbidity requires holistic, integrated strategies across health and social services, supported by data sharing and personalized care plans (21–24). Digital health can facilitate self-management, adherence, and communication with professionals, while also supporting diagnosis, therapy, and clinical decision-making (25, 26). Its effectiveness, however, depends on health literacy, usability, and contextual adaptation, as adoption is limited by organizational, technical, economic, and cultural barriers (27–31). In this context, the European Commission’s ‘Blueprint on the Digital Transformation of Health and Care for an Ageing Society’ provides a structured methodology to define demand-driven use cases and personas that capture unmet needs, possible IT solutions, and enabling technologies for active and healthy ageing (32, 33). This study aimed to identify the socio-health unmet needs of community-dwelling older adults with multimorbidity and polypharmacy using a mixed-methods approach. A secondary objective was to translate these findings into a structured Blueprint persona and systematically map potential digital health solutions to address the identified needs.

2 Materials and methods

The study implemented a mixed qualitative-quantitative method aimed at identifying and analyzing key digital solutions and high-impact usage scenarios applied to community-dwelling older adults with two or more chronic conditions. A Focus Group (FG) was set up at Federico II University and Hospital (F2UH) to empathetically engage key professionals with extensive knowledge of healthcare services for older patients with multimorbidity, aimed at identifying care processes that could be enhanced by digital tools (34, 35). This was a mixed-methods study that combined quantitative screening data from the SUNFRAIL+ tool with qualitative insights from a multidisciplinary Focus Group. The quantitative component provided a profile of risk factors, while the qualitative component enabled an in-depth exploration of unmet needs, which were subsequently translated into digital health requirements.

2.1 Focus group—procedure

A multidisciplinary professionals’ focus group was conducted at F2UH with participants from internal medicine (n = 2), endocrinology (n = 1), geriatrics (n = 1), nursing (n = 1), pharmacy (n = 1), psychology (n = 1), nutrition (n = 3), biology (n = 1), digital health/biomedical engineering (n = 2), and architecture (n = 2). Professionals were recruited via purposive sampling (role/seniority and direct involvement in the care of older adults with multimorbidity at F2UH); the sample size was determined pragmatically to ensure multidisciplinary coverage and was deemed adequate by thematic sufficiency across four sessions. The FG met four times (Sept 2023–Mar 2024) and followed a semi-structured guide covering: (i) unmet needs relevant to multimorbidity, (ii) candidate digital functions and data/interoperability requirements, and (iii) barriers/facilitators and acceptability. Each session lasted approximately 90 min, was audio-recorded, and a rapporteur kept structured minutes on a standardized electronic template; outputs were member-checked by participants before consolidation. The verbatim prompts used with professionals and the stimulus technologies are provided in Supplementary material S1. Any disagreements on item wording or categorization were noted in the minutes and finalized in a subsequent consensus meeting; unresolved items were adjudicated by a third senior investigator.

2.2 Qualitative analysis

To analyze the focus-group discussions, audio recordings were transcribed verbatim and examined using reflexive thematic analysis following Braun & Clarke’s phases: (i) familiarization; (ii) generation of initial codes; (iii) construction of candidate themes; (iv) review of themes against coded extracts and the full dataset; (v) theme definition and naming; and (vi) reporting. Two researchers independently coded all materials using an inductive, primarily semantic approach (allowing latent insights when warranted). A shared codebook was iteratively developed and refined; discrepancies were resolved by consensus, with escalation to a third senior investigator when needed. To support trustworthiness, we maintained an audit trail (audio files, structured minutes, versioned matrices), sought negative/contradictory cases, and conducted a member-check of key takeaways at the end of sessions. In line with a reflexive approach to thematic analysis, we did not compute inter-rater reliability coefficients (e.g., Cohen’s κ); rigor was ensured through double coding, consensus meetings, and transparent documentation. The codebook (labels and definitions) and a textual theme map are provided in Supplementary material S2; anonymized exemplar extracts can be supplied to editors upon reasonable request.

2.3 SUNFRAIL+

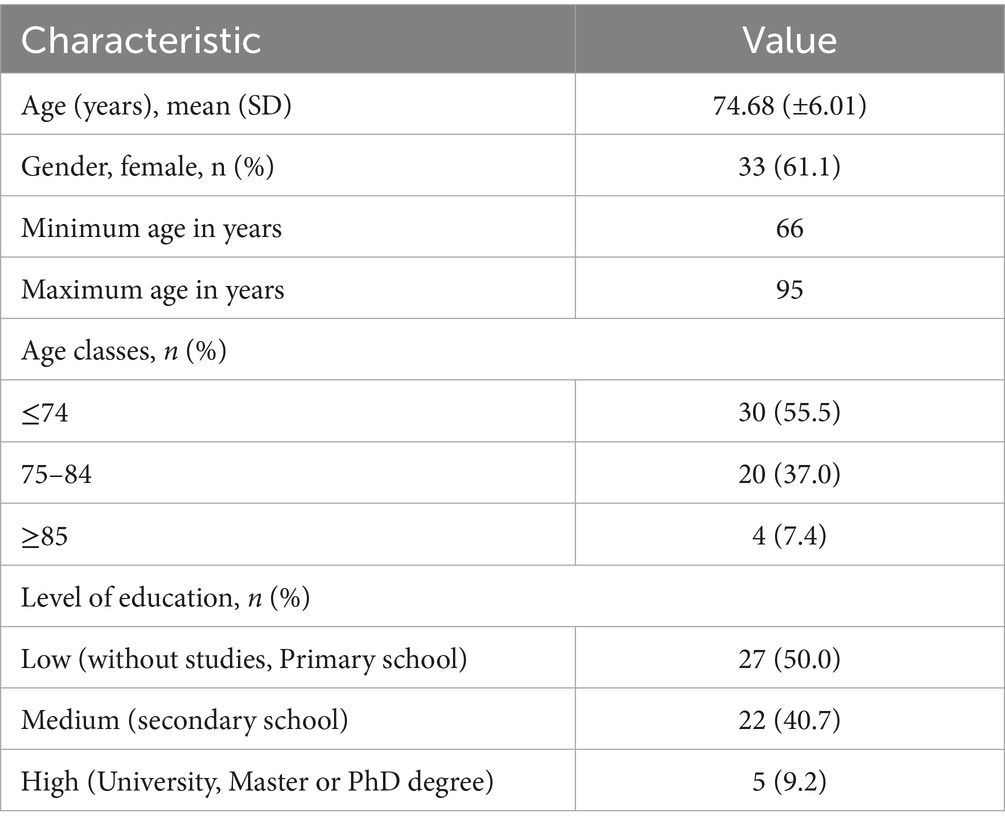

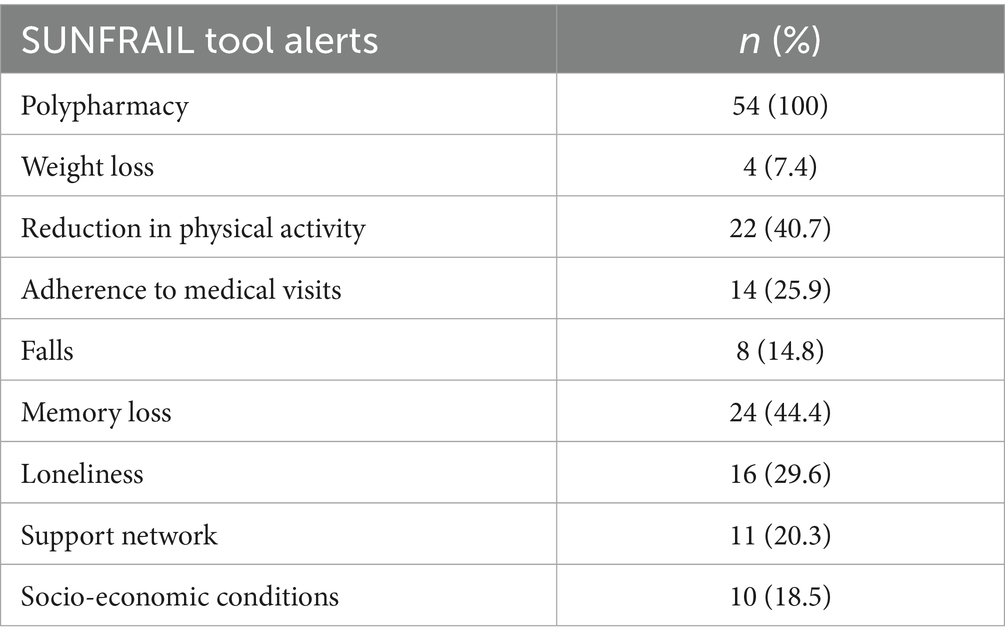

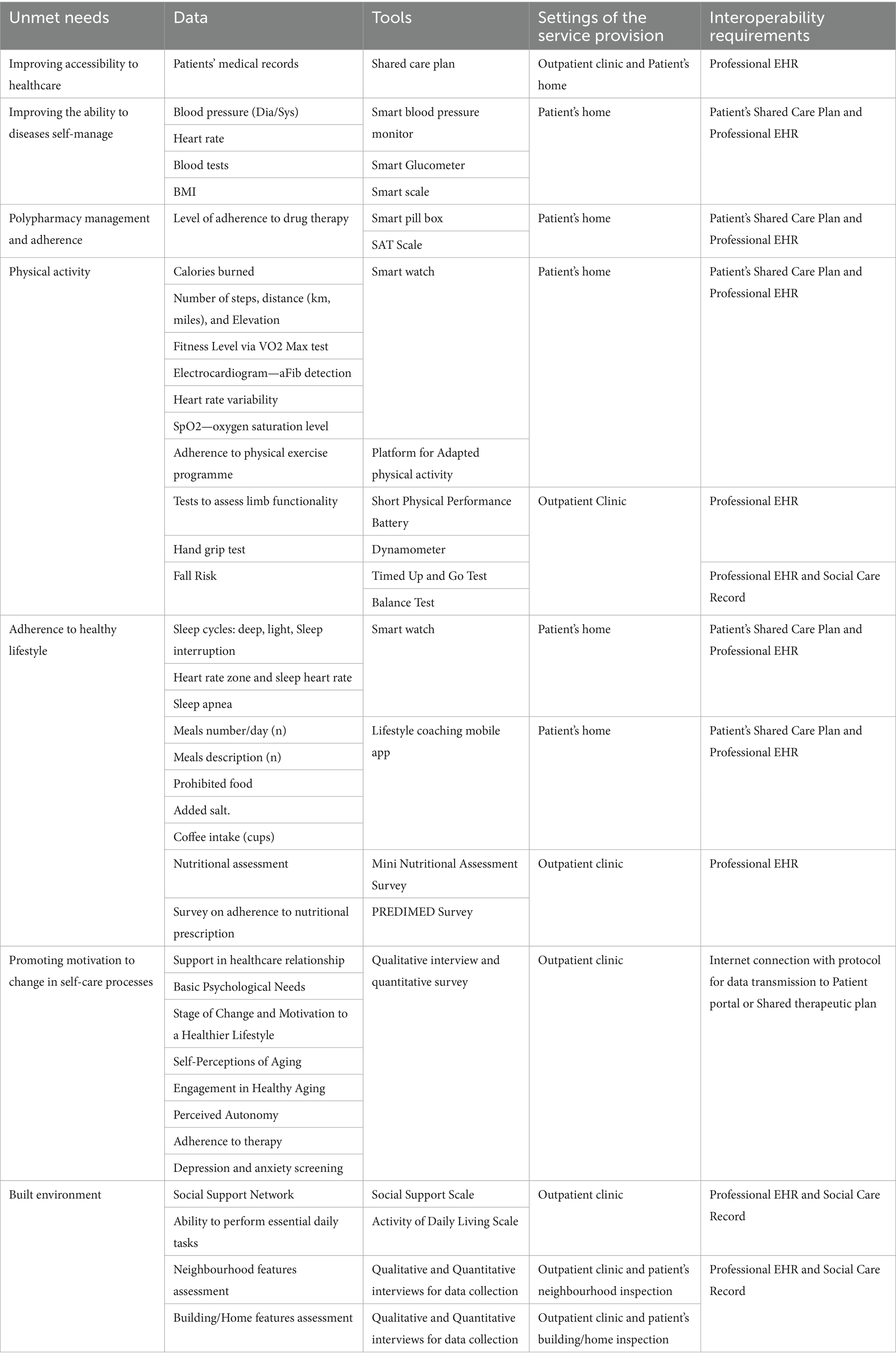

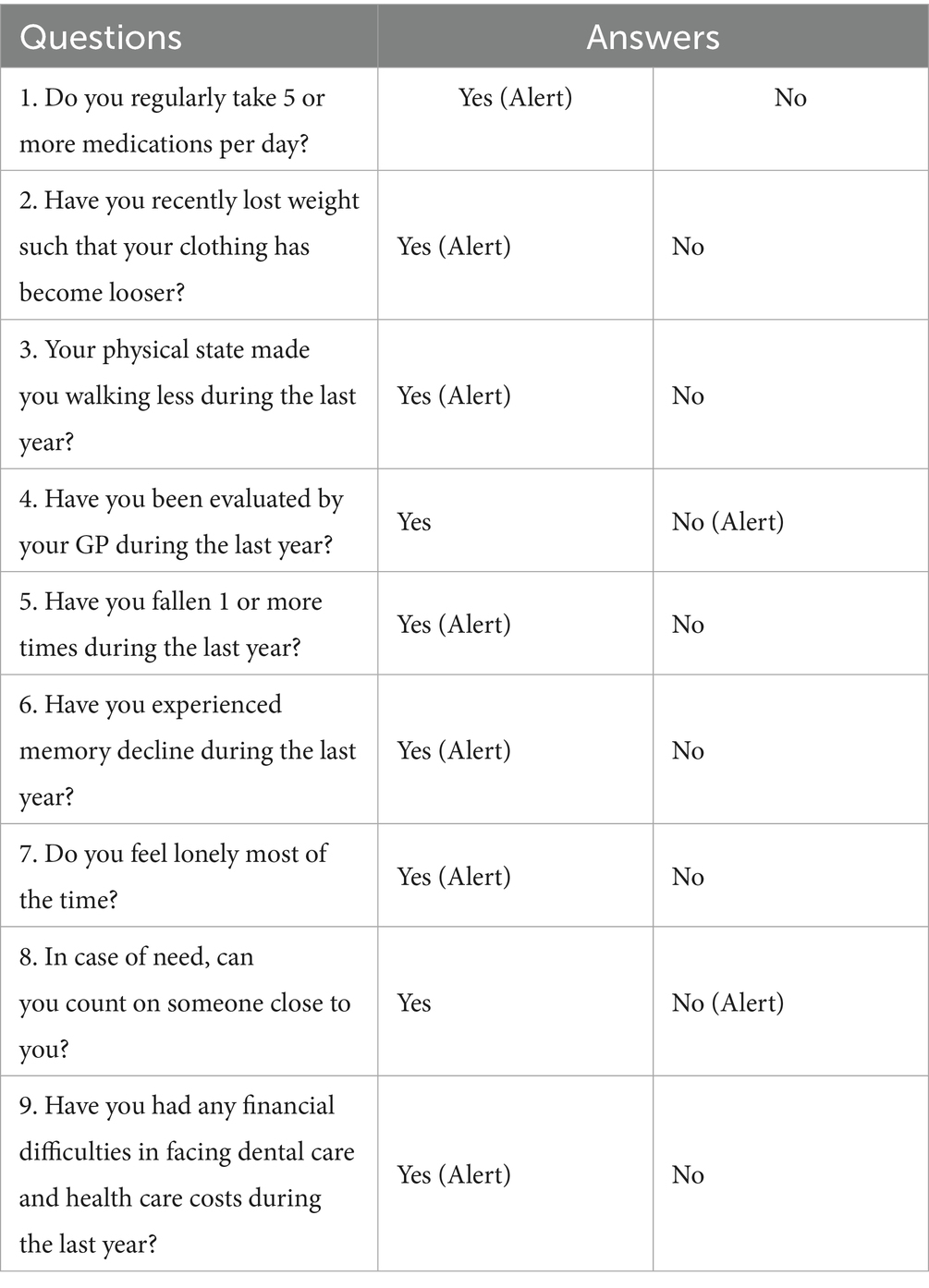

In this manuscript, we analysed SUNFRAIL+ screening data collected at the Federico II University Hospital (F2UH) site. Patients with multiple chronic conditions are more likely to receive multiple drug treatments (36); accordingly, many studies use two or more conditions (multimorbidity) and five or more medications (polypharmacy) as consistent endpoints (37). The Focus Group (FG) reviewed preliminary data from the multicentre SUNFRAIL+ study promoted by the PROMIS network (38), with contributions from eight Italian regions and coordinated by F2UH (39). The study aimed to validate an innovative model of frailty screening in community-dwelling older adults, supported by information technology (IT). The screening model adopts the SUNFRAIL tool, consisting of nine questions investigating the physical, psychological, and socio-economic domains (Table 1) (40). After written informed consent, screening data were collected by clinicians during outpatient visits across five F2UH departments (Adapted Physical Activity Prescription, Geriatrics, Neurology, Diabetology, Maxillofacial Surgery). A total of n = 113 older adults were enrolled at the F2UH site of the multicentre SUNFRAIL+ study (see Ethical approval, Section 2.4). Analyses focused on the polypharmacy subgroup (n = 54) and were strictly descriptive. Given this descriptive aim, no a priori power calculation was performed. To profile common characteristics, the FG selected older adults who answered “yes” to the question “Do you regularly take five or more medications per day?” and identified the frailty risk factors they presented. Only counts and percentages are reported; no inferential statistics (e.g., p-values, confidence intervals) were computed.

Table 1. The SUNFRAIL checklist (40).

2.4 Blueprint persona

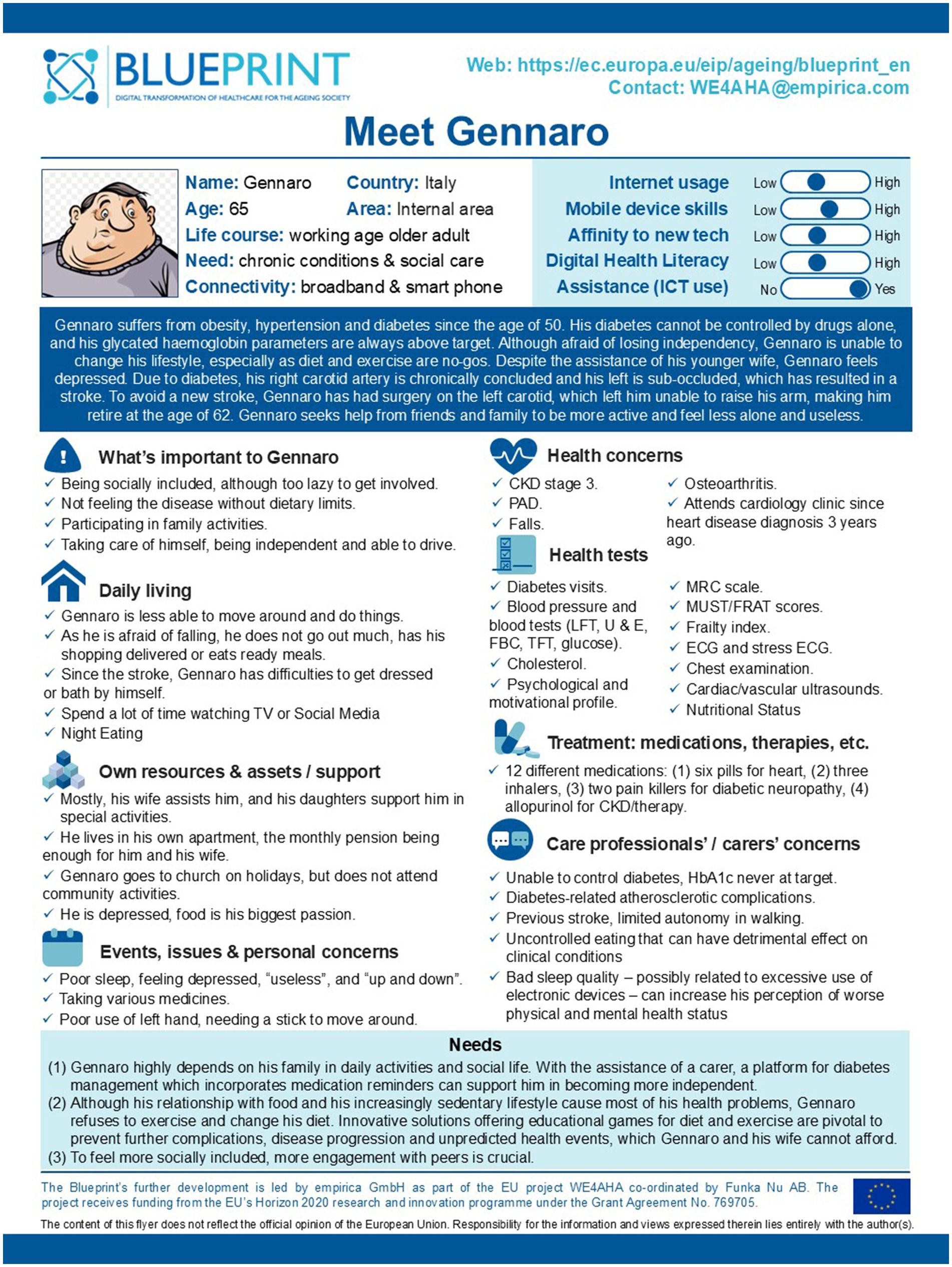

The European Commission’s Blueprint methodology is a patient-centred approach for the design of IT-supported interventions that highlight patients’ unmet needs to design key use scenarios (41). The health, social and technological needs of the target population are represented through a “Persona” use case, a single, specific, hypothetical patient, with a realistic name and a brief description of their needs, goals, hopes, dreams and attitudes (42). In addition, the use case reports the typical behavioral characteristics of the target population, based on the experience of the experts contributing to the definition. Based on the analysis of the risk factors resulting from SUNFRAIL+ questionnaire, a theoretical elaboration of the Blueprint persona was developed by the FG. The professionals involved in the FG answered iteratively to the questions in the Blueprint Persona Development tool (Supplementary material S3) and agreed on the final response. Persona development followed the European Commission’s Blueprint methodology. The process combined SUNFRAIL+ data with qualitative insights from the FG to build a realistic profile, including socio-demographic characteristics, health status, behavioural traits, and contextual factors. The persona (‘Gennaro’) was iteratively refined until consensus was reached among FG members. This persona represents an expert-informed synthesis step intended to structure design hypotheses. End-user co-design and validation were not undertaken at this stage and are planned as a subsequent phase within the broader UCD (User-Centered Design) pipeline.

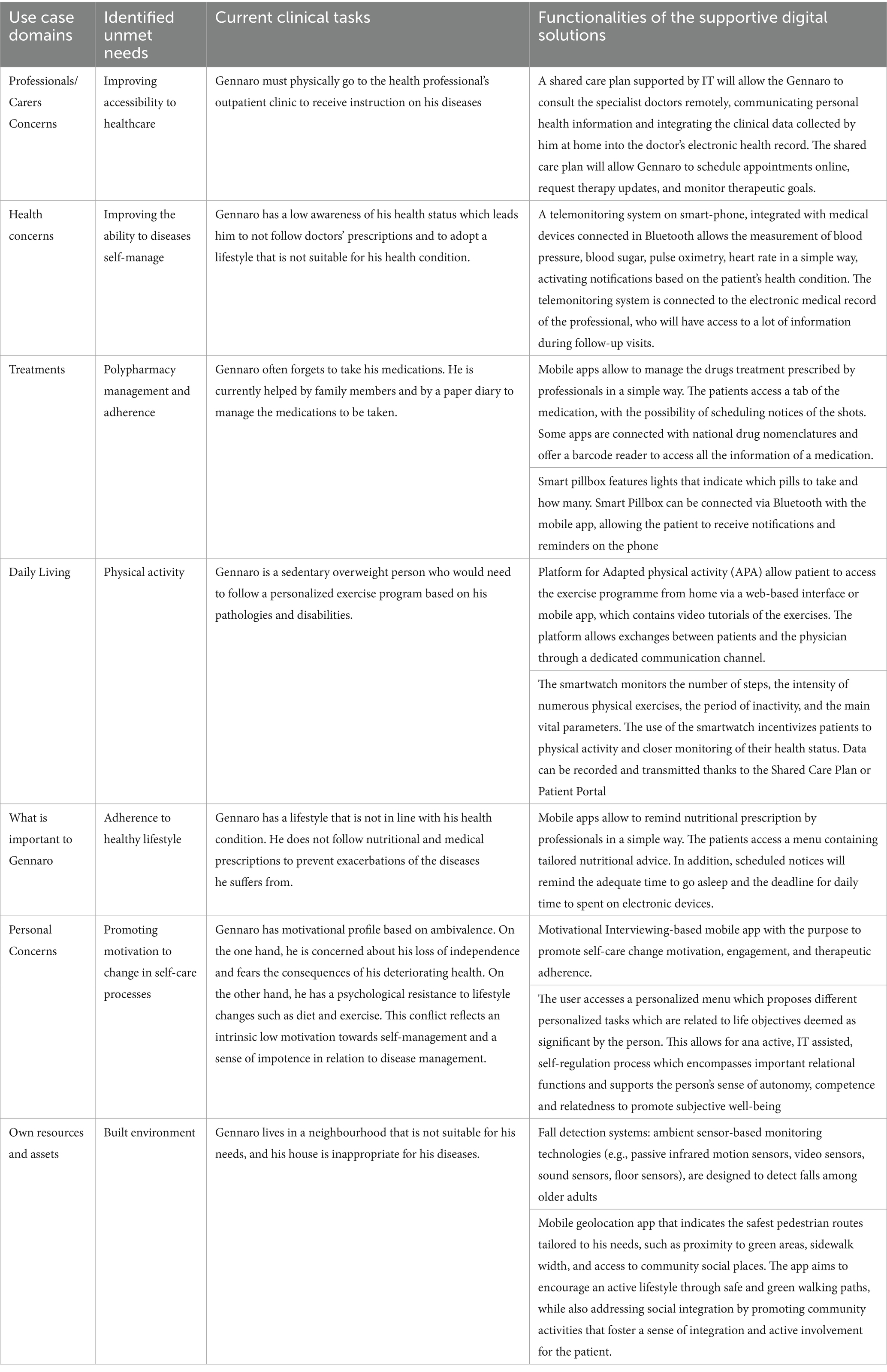

2.5 Design of digital intervention

Based on the Persona use case, the FG identified digital solutions that can help meet the needs of patients in healthcare and other domains, such as social, psychological, environmental, etc., to design a digitally supported intervention, integrated into the current service provision, from organizational and technological perspectives. Finally, the FG identified the dataset to be collected through digitally supported intervention. In particular, the FG focused on the type of data, the tools adopted for data collection, the setup and interoperability requirements. Such a minimum dataset helps to collect and manage data from multiple sources (EHR, medical devices, wearables, etc.), identifying the interoperability requirements that digitally supported interventions must provide.

2.6 Ethical approval

The studies involving humans were approved by the local Ethics Committee of University “Federico II”—Azienda Ospedaliera di Rilievo Nazionale “A. Cardarelli” (N. 284/22). The research protocol was registered at ClinicalTrials.gov on 9 December 2022 (registration number: NCT05646472). The studies were conducted in accordance with local legislation and institutional requirements. Written informed consent for participation was obtained from the participants’ legal guardians or next of kin.”

3 Results

3.1 SUNFRAIL+ questionnaire results

The FG extracted and analyzed preliminary data of the SUNFRAIL+ study collected at the F2UH, the answers provided by n = 54 patients who declared they took 5 or more drugs. These data were not intended to provide inferential statistics, but rather to generate a descriptive profile of multimorbid patients with polypharmacy, which served to contextualize and enrich the identification of unmet needs in the subsequent qualitative phase. The mean age of this subpopulation is 74.68 (±6.01) and an age range between 66 and 95. More than half of the participants (55.5%) are aged 74 years or younger. n = 33 are women. Half of participants (50%; n = 27) have a low level of education. Only n = 5 (9.2%) had attained a university degree (Table 2). The most recurrent risk factor in this sub-population is the perception of memory loss (n = 24; 44.4%). This finding corresponds to the cognitive domain of the SUNFRAIL+ tool, highlighting early vulnerability that may interact with pharmacological complexity. This symptom could be linked both to the age-related loss of cognitive function and to the side effects of polypharmacy. In 40.7% of cases, participants reported a decrease in physical activity and the adoption of a more sedentary lifestyle, linked to health conditions and loss of independence. This result is aligned with the physical activity domain of SUNFRAIL+, reinforcing the link between reduced mobility, frailty progression, and loss of independence. The feeling of loneliness found in n = 16 participants (29.6%) highlight a vulnerable psychological state and a weakening of social relationships due to the loss of independence. This indicator belongs to the social domain of SUNFRAIL+, underlining how psychological vulnerability and social isolation interact with health status. 25.9% (n = 14) of participants declared that they had not been visited by their General Practitioner (GP) in the last year. This could be explained by difficult communication with GP, or a problem with the accessibility of doctor’s outpatient clinic. Finally, it could be a question of low trust in GP and inappropriate use of specialist services (Table 3). Overall, these descriptive results provided an empirical foundation across the main SUNFRAIL+ domains (cognitive, physical, social, and healthcare access). They guided the Focus Group in selecting the most relevant unmet needs for persona development and digital health solution mapping.”

3.2 Persona profile

Using the Blueprint method and drawing on the SUNFRAIL+ questionnaire results of the sub-cohort, the Focus Group (FG) constructed a fictitious but realistic profile, named ‘Gennaro’. This persona was inspired by common characteristics and unmet needs observed in patients with multimorbidity and polypharmacy, and was iteratively refined through multidisciplinary discussion. Gennaro is a 78-year-old man with obesity, hypertension, and poorly controlled type 2 diabetes, complicated by cardiovascular disease and a previous stroke, which reduced his autonomy and forced early retirement. Despite the support of his wife, he reports depressive symptoms and feelings of loneliness. Living in a suburban area, in a third-floor apartment without a lift and with poor transport connections, he struggles to access healthcare services and maintain social contacts. This persona highlights unmet needs in pharmacological management, physical activity, sociability, disease self-management, and psychological well-being. These needs were systematically linked to potential mHealth and digital solutions identified in the subsequent analysis (Figure 1).

3.3 Applicable digital health solution

Based on the persona profile and SUNFRAIL+ data, the FG systematically mapped digital health solutions to the identified unmet needs. The following categories summarize the main solutions, which were organized by domain and technology to ensure a clear link between needs and interventions.

3.3.1 Shared care plan

The Shared Care Plan (SCP) was identified as a priority to address fragmented communication between professionals and patients, allowing shared goal-setting, monitoring, and integration of data from medical devices.

3.3.2 Telemonitoring

Telemonitoring solutions, including wearables and home devices, were proposed to improve real-time monitoring of clinical parameters and support proactive treatment adjustments.

3.3.3 Medication adherence

Mobile apps and smart pillboxes were highlighted as strategies to simplify medication management and improve adherence in polypharmacy.

3.3.4 Physical activity

Adapted physical activity programs delivered via apps or VR-based rehabilitation tools were suggested to counter sedentary behaviors and support functional recovery.

3.3.5 Healthy lifestyle coaching

Digital coaching platforms were proposed to sustain diet and exercise adherence through personalized feedback and progress tracking.

3.3.6 Promotion of motivation to change in self-care processes

Motivational apps based on self-regulation and interactive tasks were identified as tools to strengthen autonomy and adherence to self-care.

3.3.7 Ambient assisted living (AAL)

Ambient Assisted Living (AAL) systems were identified as relevant for supporting autonomy, safety, and fall prevention among older adults. The FG emphasized their potential to integrate information from daily activities and living environments, providing timely alerts and promoting safer ageing at home and in the community.

A summary of the identified needs and digital solutions is provided in Table 4, which links each domain (clinical, psychological, social, environmental) with potential technological interventions. This analytical structure reduces redundancy and highlights the alignment between unmet needs and feasible solutions.

3.4 Digital intervention

The FG identified requirements for a digital intervention to support integration of the proposed solutions. Specifically, participants outlined the types of data, the tools for data collection, the implementation contexts, and the interoperability standards needed for a shared database capable of managing inputs from multiple sources (e.g., clinical settings, self-monitoring devices, and wearables). These elements are summarized in Table 5.

4 Discussion

This study explored the unmet needs of older adults with multimorbidity, linking SUNFRAIL+ data with a FG-based persona development process, and mapped potential digital solutions. Multimorbidity, highly prevalent in older adults (43), is closely associated with polypharmacy and adverse outcomes such as increased mortality, reduced quality of life, and functional decline (44). Our findings suggest that polypharmacy, memory loss, reduced physical activity, and isolation represent prominent challenges in our study population. The high prevalence of polypharmacy and self-reported memory loss in our cohort underscores the interplay between cognitive vulnerability and complex therapeutic regimens. Similarly, reduced physical activity and social isolation reflect multidimensional frailty that can accelerate functional decline. These findings were embodied in the persona ‘Gennaro’, which synthesized the most recurrent trajectories of risk and unmet needs identified through SUNFRAIL+ data and FG discussion. In this context, the “Personas” approach, developed by the “Blueprint on Digital Transformation in Health and Care in an Aging Society,” offers a concise and intuitive method to identify unmet needs among specific subgroups of patients.

4.1 Principal findings and persona development

While the persona approach provided a useful synthesis of quantitative and qualitative findings, it remains a theoretical construct. In our study, patient co-design was not directly included, which may limit ecological validity. Future studies should integrate patients’ perspectives to refine and validate personas against real-life experiences. Despite this limitation, the efforts of the interdisciplinary focus group in the present study allowed us to identify the IT solutions and the dataset pivotal to implement a digitally supported intervention addressing the identified needs. This approach aims both to enhance cost-effective healthcare services (45) and facilitate multidisciplinary integration in the management of non-communicable chronic diseases (46).

4.2 Digital solutions for clinical management

According to FG insights, shared care plans and telemonitoring systems were identified as potentially supporting patients’ day-to-day self-management and potentially assisting healthcare professionals in treatment optimization, though this requires prospective evaluation. Adherence to multiple medications therapy in multimorbid NCD patients is challenging (47). In our FG, medication adherence emerged as a critical issue for multimorbid patients. Among the solutions identified, smart pillboxes and mobile apps were considered relevant to simplify complex regimens. This aligns with previous evidence showing their role in reducing adverse events and improving compliance (48). The FG also emphasized the importance of supporting clinicians in managing polypharmacy. Clinical decision support systems were identified as potential enablers, in line with prior studies showing their value in improving prescribing and deprescribing practices (49, 50). Diabetes represents one of the prevalent chronic conditions within multimorbidity scenarios (51). To effectively manage diabetes, non-invasive blood glucose monitoring may help empower patients to make informed decisions regarding dietary choices, physical activity levels, and medication usage (52). Maintaining glucose levels within the target range contributes to mitigating additional health complications associated with diabetes (45).

4.3 Supporting lifestyle and behavioral change

Proper nutrition is essential for managing chronic diseases and improving overall health. Mobile apps can provide tailored nutritional advice and reminders and may support adherence to dietary prescriptions. These tools facilitate regular monitoring and adjustment of dietary plans based on the patient’s health status and taste preferences (53). Sedentary behavior is linked to an increased risk of multimorbidity and falls among older adults, highlighting the importance of public policies promoting physical activity (54). Adapted physical activity programs, administered at home through a web-based platform interface, coupled with smartwatches or other wearable monitoring devices, may encourage physical exercise and may enhance the overall health status of patients in some contexts, subject to validation (55). Self-care is a dynamic and complex process that requires psychological adjustment of NCD patients to their medical conditions (56). Motivational processes and emotional self-regulation are relevant both to adapt to disease conditions and to manage and maintain self-care behaviors (57). Personal motivation is a key element for patients to be ready for changes in disease self-management. Motivational Interviewing (MI) may constitute a very appropriate intervention in those cases in which the behavioural changes (i.e., dietary changes, physical activity, etc.) are hindered by ambivalence, resistance and denial (58). MI enhance patient engagement and self-care by providing personalized tasks and goals, fostering a sense of autonomy and competence. MI contribute to address psychological barriers to lifestyle changes, such as fear of losing independence or depressive symptoms. Technology-delivered motivational interviewing interventions (TAMIs) offer considerable potential to reduce costs, minimize therapist and training burden, and expand the range of clients that may benefit from adaptations of MI (59).

4.4 Environmental and technological integration

Beyond psychological support, the FG also emphasized environmental and technological solutions that directly sustain autonomy in daily life. Our FG highlighted the relevance of Ambient Assisted Living (AAL) systems to promote autonomy and safety in older adults. This finding is consistent with studies on indoor monitoring and data integration (60, 61) and on outdoor navigation support and fall prevention (62, 63). Nonetheless, the integration of heterogeneous data sources remains a challenge, as underlined by El Murabet et al. (64). Last but not least, the built environment significantly influences the health and well-being of older adults, both in outdoor and indoor settings (65, 66). Outdoor activities, such as walking, shopping, socialising, and engaging in physical exercise—are essential to prevent functional decline in older adults. Providing an adequate functional mix within neighbourhoods, together with accessible parks and green spaces, creates opportunities for movement and spatial orientation in open areas, while alternative, comfortable, and safe mobility systems support high levels of walkability. In addition, the smart-home modification process for ageing in place involves not only structural refurbishment or the rearrangement of the housing layout to increase usability and safety, but also the installation of smart technology devices (67, 68). Therefore, qualitative and quantitative assessments of neighbourhood and home features are instrumental in identifying modifications that support ageing in place. Technologies such as fall-detection systems and geolocation apps may help enhance safety and support an active lifestyle by reducing fall and wandering risks, pending prospective validation. Next, steps include multi-site, cross-context studies to co-design and prospectively validate the mapped digital options, evaluating feasibility, usability, acceptability, and contextual fit across different healthcare systems.

4.5 Implications for implementation and policy

To move beyond isolated pilots, digitally supported home care should be embedded within governance and reimbursement frameworks; otherwise adoption risks remaining fragmented and time-limited (69). Integration through platforms interoperable with the Electronic Health Record (EHR) would allow clinicians to prescribe digital interventions within existing care pathways and reduce siloed use. Although this study did not assess social prescribing of digital tools, such an approach could be promising for prevention and health promotion; however, organisational and cost evaluations are required before scale-up (70). Future work should also broaden clinical perspectives by involving additional specialties (e.g., vestibular, somatosensory, visual) to capture needs that influence independence and well-being in older adults (71–73). In low-resource contexts, staged adoption can prioritise low-cost, high-impact functions (e.g., medication reminders, basic vitals logging) delivered via SMS/IVR or USSD and offline-first workflows. A minimal dataset (only safety-critical fields) and interoperability through open standards reduce technical burden and vendor lock-in. Task-shifting to community health workers, short micro-trainings for patients/caregivers, and clear governance/reimbursement micro-paths (e.g., bundles or capitated add-ons) can improve feasibility. A lean monitoring plan (simple indicators for uptake, adherence, flags) supports iterative scale-up. As a single-centre Italian study, the present findings are context-dependent. The methodological approach (persona-guided, expert-informed mapping) is portable, but content and priorities will require local adaptation to reflect cultural norms, service organisation, and reimbursement rules.

4.6 Limits

This study has several limitations. First, the persona and digital options were developed through expert insight rather than direct patient co-design; co-design and end-user validation are necessary next steps. Second, qualitative data reflect a single-center, professionals-only focus group in Italy, which may limit transferability to other contexts. Transferability may also be constrained by cultural factors in aging and care-seeking, which were not explored in this study. Third, the quantitative component is descriptive and restricted to a polypharmacy subgroup (n = 54), and therefore does not support inferential claims. Fourth, although multidisciplinary, the focus-group composition may have under-represented some clinical domains (e.g., vestibular, somatosensory, visual), and priority-setting reflected resource constraints. Fifth, we adopted reflexive thematic analysis and therefore did not compute inter-rater reliability coefficients; rigor was supported via double coding, consensus meetings (with third-investigator adjudication when needed), an audit trail, member-checks, and a search for negative cases. Sixth, the study did not assess social prescribing or the economic/organizational implications (e.g., cost-effectiveness, reimbursement models) of implementation. Despite these safeguards, residual interpretive bias may persist; future work will include patient/caregiver co-design, multi-site validation, and holistic feasibility assessment.

5 Conclusion

This study provides a structured methodological basis for identifying unmet needs in older adults with multimorbidity and mapping tailored digital health solutions. By integrating SUNFRAIL+ data with FG insights through the Blueprint persona approach, we described critical challenges such as polypharmacy, memory loss, reduced physical activity, and social isolation, and linked them to concrete technological options including telemonitoring, shared care plans, medication adherence tools, and Ambient Assisted Living systems. These findings suggest that, when embedded in a holistic model of care, digital interventions may help support adherence, continuity of care, and autonomy and well-being, pending co-design and prospective validation. While further validation and patient co-design are required, this approach represents a promising pathway to strengthen the long-term management of multimorbidity.

Data availability statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors without undue reservation.

Ethics statement

The studies involving humans were approved by the local Ethics Committee of University “Federico II”—Azienda Ospedaliera di Rilievo Nazionale “A. Cardarelli” (N. 284/22). The research protocol was registered at ClinicalTrials.gov on 9 December 2022 (registration number: NCT05646472). The studies were conducted in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. Written informed consent for participation in this study was provided by the participants’ legal guardians/next of kin.

Author contributions

VL: Writing – review & editing, Conceptualization, Writing – original draft, Investigation, Formal analysis, Supervision, Project administration, Data curation, Methodology. MV: Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. AlC: Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. DL: Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. MP: Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. FC: Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. SA: Writing – review & editing, Writing – original draft. FM: Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. CV: Writing – review & editing, Writing – original draft. MF: Writing – review & editing, Writing – original draft. DA: Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. TR: Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. LM: Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. EA: Writing – review & editing, Writing – original draft. EM: Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. AnC: Writing – review & editing, Writing – original draft. GI: Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. MI: Writing – review & editing, Writing – original draft.

Funding

The author(s) declare that financial support was received for the research and/or publication of this article. The present research is based upon work from the Italian Ministry of University and Research‘s Enlarged Partnership 8 “A novel public-private alliance to generate socioeconomic, biomedical and technological solutions for an inclusive Italian ageing society – Age-It” (Project number: PE0000015), supported by the Italian National Recovery and Resilience Plan, financed by Next Generation Europe programme.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

The author(s) declared that they were an editorial board member of Frontiers, at the time of submission. This had no impact on the peer review process and the final decision.

Generative AI statement

The authors declare that no Gen AI was used in the creation of this manuscript.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Supplementary material

The Supplementary material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fpubh.2025.1637748/full#supplementary-material

References

1. Moffat, K, and Mercer, SW. Challenges of managing people with multimorbidity in today's healthcare systems. BMC Fam Pract. (2015) 16:129. doi: 10.1186/s12875-015-0344-4

2. Calderón-Larrañaga, A, Vetrano, DL, Onder, G, Gimeno-Feliu, LA, Coscollar-Santaliestra, C, Carfí, A, et al. Assessing and measuring chronic multimorbidity in the older population: a proposal for its operationalization. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. (2017) 72:1417–23. doi: 10.1093/gerona/glw233

3. Nguyen, H, Manolova, G, Daskalopoulou, C, Vitoratou, S, Prince, M, and Prina, AM. Prevalence of multimorbidity in community settings: a systematic review and meta-analysis of observational studies. J Comorbidity. (2019) 9:2235042X19870934. doi: 10.1177/2235042X19870934

4. Xu, X, Mishra, GD, and Jones, M. Mapping the global research landscape and knowledge gaps on multimorbidity: a bibliometric study. J Glob Health. (2017) 7:010414. doi: 10.7189/jogh.07.010414

5. Fried, LP, Ferrucci, L, Darer, J, Williamson, JD, and Anderson, G. Untangling the concepts of disability, frailty, and comorbidity: implications for improved targeting and care. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. (2004) 59:255–63. doi: 10.1093/gerona/59.3.m255

6. Vetrano, DL, Palmer, K, Marengoni, A, Marzetti, E, Lattanzio, F, Roller-Wirnsberger, R, et al. Frailty and multimorbidity: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. (2019) 74:659–66. doi: 10.1093/gerona/gly110

7. Caughey, GE, Pratt, NL, Barratt, JD, Shakib, S, Kemp-Casey, AR, and Roughead, EE. Understanding 30-day re-admission after hospitalisation of older patients for diabetes: identifying those at greatest risk. Med J Aust. (2017) 206:170–5. doi: 10.5694/mja16.00671

8. Longman, J, Passey, M, Singer, J, and Morgan, G. The role of social isolation in frequent and/or avoidable hospitalisation: rural community-based service providers' perspectives. Aust Health Rev. (2013) 37:223–31. doi: 10.1071/AH12152

9. Roller-Wirnsberger, R, Liotta, G, Lindner, S, Iaccarino, G, De Luca, V, Geurden, B, et al. Public health and clinical approach to proactive management of frailty in multidimensional arena. Annali di igiene: medicina preventiva e di comunita. (2021) 33:543–54. doi: 10.7416/ai.2021.2426

10. Kardas, P, Lewek, P, and Matyjaszczyk, M. Determinants of patient adherence: a review of systematic reviews. Front Pharmacol. (2013) 4:91. doi: 10.3389/fphar.2013.00091

11. Maffoni, M, Traversoni, S, Costa, E, Midão, L, Kardas, P, Kurczewska-Michalak, M, et al. Medication adherence in the older adults with chronic multimorbidity: a systematic review of qualitative studies on patient's experience. Eur Geriatric Med. (2020) 11:369–81. doi: 10.1007/s41999-020-00313-2

12. Yang, C, Lee, DTF, Wang, X, and Chair, SY. Developing a medication self-management program to enhance medication adherence among older adults with multimorbidity using intervention mapping. Gerontologist. (2023) 63:637–47. doi: 10.1093/geront/gnac069

13. National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE). Multimorbidity: clinical assessment and management. United Kingdom: NICE (2016).

14. Diehl, M, Wahl, HW, Barrett, AE, Brothers, AF, Miche, M, Montepare, JM, et al. Awareness of aging: theoretical considerations on an emerging concept. Dev Rev. (2014) 34:93–113. doi: 10.1016/j.dr.2014.01.001

15. Moss-Morris, R. Adjusting to chronic illness: time for a unified theory. Br J Health Psychol. (2013) 18:681–6. doi: 10.1111/bjhp.12072

16. Walker, JG, Jackson, HJ, and Littlejohn, GO. Models of adjustment to chronic illness: using the example of rheumatoid arthritis. Clin Psychol Rev. (2004) 24:461–88. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2004.03.001

17. Arcaya, MC, Arcaya, AL, and Subramanian, SV. Inequalities in health: definitions, concepts, and theories. Glob Health Action. (2015) 8:27106. doi: 10.3402/gha.v8.27106

18. Fitzpatrick, KM, and Willis, D. Chronic disease, the built environment, and unequal health risks in the 500 largest U.S. cities. Int J Environ Res Public Health. (2020) 17:2961. doi: 10.3390/ijerph17082961

19. Irankhah, K, Asadimehr, S, Kiani, B, Jamali, J, Rezvani, R, and Sobhani, SR. Investigating the role of the built environment, socio-economic status, and lifestyle factors in the prevalence of chronic diseases in Mashhad: PLS-SEM model. Front Public Health. (2024) 12:1358423. doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2024.1358423

20. Liotta, G, Ussai, S, Illario, M, O'Caoimh, R, Cano, A, Holland, C, et al. Frailty as the future core business of public health: report of the activities of the A3 action group of the European innovation partnership on active and healthy ageing (EIP on AHA). Int J Environ Res Public Health. (2018) 15:2843. doi: 10.3390/ijerph15122843

21. Kernick, D, Chew-Graham, CA, and O'Flynn, N. Clinical assessment and management of multimorbidity: NICE guideline. Br J Gen Pract. (2017) 67:235–6. doi: 10.3399/bjgp17X690857

22. McIlvennan, CK, Eapen, ZJ, and Allen, LA. Hospital readmissions reduction program. Circulation. (2015) 131:1796–803. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.114.010270

23. Segal, M, Rollins, E, Hodges, K, and Roozeboom, M. Medicare-medicaid eligible beneficiaries and potentially avoidable hospitalizations. Medicare Medicaid Res Rev. (2014) 4:mmrr.004.01.b01. doi: 10.5600/mmrr.004.01.b01

24. Wannheden, C, Åberg-Wennerholm, M, Dahlberg, M, Revenäs, Å, Tolf, S, Eftimovska, E, et al. Digital health technologies enabling partnerships in chronic care management: scoping review. J Med Internet Res. (2022) 24:e38980. doi: 10.2196/38980

25. De Luca, V, Bozzetto, L, Giglio, C, Tramontano, G, De Simone, G, Luciano, A, et al. Clinical outcomes of a digitally supported approach for self-management of type 2 diabetes mellitus. Front Public Health. (2023) 11:1219661. doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2023.1219661

26. World Health Organization. Global strategy on digital health 2020–2025 (2021). Available online at: https://www.who.int/docs/default-source/documents/gs4dhdaa2a9f352b0445bafbc79ca799dce4d.pdf (Accessed March 26, 2025).

27. Barbabella, F, Melchiorre, MG, Quattrini, S, Papa, R, Lamura, G, Richardson, E, et al. eds. How can eHealth improve care for people with multimorbidity in Europe? Berlin, Germany: European Observatory on Health Systems and Policies (2017).

28. Bonet Olivencia, S, Rao, AH, Smith, A, and Sasangohar, F. Eliciting requirements for a diabetes self-management application for underserved populations: a multi-stakeholder analysis. Int J Environ Res Public Health. (2021) 19:127. doi: 10.3390/ijerph19010127

29. Slater, H, Campbell, JM, Stinson, JN, Burley, MM, and Briggs, AM. End user and implementer experiences of mHealth technologies for noncommunicable chronic disease management in young adults: systematic review. J Med Internet Res. (2017) 19:e406. doi: 10.2196/jmir.8888

30. Wang, Y, Xue, H, Huang, Y, Huang, L, and Zhang, D. A systematic review of application and effectiveness of mHealth interventions for obesity and diabetes treatment and self-management. Adv Nutr (Bethesda, Md). (2017) 8:449–62. doi: 10.3945/an.116.014100

31. World Health Organization. Facing the future: opportunities and challenges for 21st-century public health in implementing the sustainable development goals and the health 2020 policy framework (2018). Available online at: https://iris.who.int/handle/10665/340350 (Accessed March 26, 2025).

32. European Commission. Blueprint digital transformation of health care for the ageing society. (2017). Available online at: https://digital-strategy.ec.europa.eu/en/library/blueprint-digital-transformation-health-and-care-ageing-society (Accessed March 26, 2025).

33. European Commission. Blueprint digital transformation of health care for the ageing society personas (2023). Available online at: https://blueprint-personas.eu/ (Accessed March 26, 2025).

34. Roberts, JP, Fisher, TR, Trowbridge, MJ, and Bent, C. A design thinking framework for healthcare management and innovation. Healthcare (Amsterdam, Netherlands). (2016) 4:11–4. doi: 10.1016/j.hjdsi.2015.12.002

35. Tausch, AP, and Menold, N. Methodological aspects of focus groups in health research: results of qualitative interviews with focus group moderators. Glob Qual Nurs Res. (2016) 3:2333393616630466. doi: 10.1177/2333393616630466

36. Wehling, M. Multimorbidity and polypharmacy: how to reduce the harmful drug load and yet add needed drugs in the elderly? Proposal of a new drug classification: fit for the aged. J Am Geriatr Soc. (2009) 57:560–1. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2009.02131.x

37. Nicholson, K, Liu, W, Fitzpatrick, D, Hardacre, KA, Roberts, S, Salerno, J, et al. Prevalence of multimorbidity and polypharmacy among adults and older adults: a systematic review. Lancet Healthy Longevity. (2024) 5:e287–96. doi: 10.1016/S2666-7568(24)00007-2

38. Illario, M, De Luca, V, Tramontano, G, Menditto, E, Iaccarino, G, Bertorello, L, et al. The Italian reference sites of the European innovation partnership on active and healthy ageing: Progetto Mattone Internazionale as an enabling factor. Ann Ist Super Sanita. (2017) 53:60–9. doi: 10.4415/ANN_17_01_12

39. De Luca, V, Femminella, GD, Leonardini, L, Patumi, L, Palummeri, E, Roba, I, et al. Digital health service for identification of frailty risk factors in community-dwelling older adults: the SUNFRAIL+ study protocol. Int J Environ Res Public Health. (2023) 20:3861. doi: 10.3390/ijerph20053861

40. Maggio, M, Barbolini, M, Longobucco, Y, Barbieri, L, Benedetti, C, Bono, F, et al. A novel tool for the early identification of frailty in elderly people: the application in primary care settings. J Frailty Aging. (2020) 9:101–6. doi: 10.14283/jfa.2019.41

41. Patalano, R, De Luca, V, Vogt, J, Birov, S, Giovannelli, L, Carruba, G, et al. An innovative approach to designing digital health solutions addressing the unmet needs of obese patients in Europe. Int J Environ Res Public Health. (2021) 18:579. doi: 10.3390/ijerph18020579

42. World Health Organisation. Be, He@lthy. Be Mobile Personas Toolkit (2019). Available online at: https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/329947/9789241516525-eng.pdf?ua=1 (Accessed March 26, 2025).

43. Kuwabara, Y, Hamada, T, Nakai, T, Fujii, M, Kinjo, A, and Osaki, Y. Association between multimorbidity and utilization of medical and long-term care among older adults in a rural mountainous area in Japan. J Rural Med. (2024) 19:105–13. doi: 10.2185/jrm.2023-049

44. Moreno, A, Moreno, J, Salas, S, González, V, Valido, A, Guardia, P, et al. CroniCare: platform for the design and implementation of follow-up, control and self-management interventions for chronic and multimorbidity patients based on mobile technologies. Stud Health Technol Inform. (2022) 290:1012–3. doi: 10.3233/SHTI220243

45. Duke, DC, Barry, S, Wagner, DV, Speight, J, Choudhary, P, and Harris, MA. Distal technologies and type 1 diabetes management. Lancet Diabet Endocrinol. (2018) 6:143–56. doi: 10.1016/S2213-8587(17)30260-7

46. Muth, C, Blom, JW, Smith, SM, Johnell, K, Gonzalez-Gonzalez, AI, Nguyen, TS, et al. Evidence supporting the best clinical management of patients with multimorbidity and polypharmacy: a systematic guideline review and expert consensus. J Intern Med. (2019) 285:272–88. doi: 10.1111/joim.12842

47. Virgolesi, M, Pucciarelli, G, Colantoni, AM, D'Andrea, F, Di Donato, B, Giorgi, F, et al. The effectiveness of a nursing discharge programme to improve medication adherence and patient satisfaction in the psychiatric intensive care unit. J Clin Nurs. (2017) 26:4456–66. doi: 10.1111/jocn.13776

48. Al-Arkee, S, Mason, J, Lane, DA, Fabritz, L, Chua, W, Haque, MS, et al. Mobile apps to improve medication adherence in cardiovascular disease: systematic review and meta-analysis. J Med Internet Res. (2021) 23:e24190. doi: 10.2196/24190

49. Reeve, J, Maden, M, Hill, R, Turk, A, Mahtani, K, Wong, G, et al. Deprescribing medicines in older people living with multimorbidity and polypharmacy: the TAILOR evidence synthesis. Health Technol Assess (Winchester, England). (2022) 26:1–148. doi: 10.3310/AAFO2475

50. Shahmoradi, L, Safdari, R, Ahmadi, H, and Zahmatkeshan, M. Clinical decision support systems-based interventions to improve medication outcomes: a systematic literature review on features and effects. Med J Islam Repub Iran. (2021) 35:27. doi: 10.47176/mjiri.35.27

51. Sinclair, AJ, and Abdelhafiz, AH. Multimorbidity, frailty and diabetes in older people-identifying interrelationships and outcomes. J Personal Med. (2022) 12:1911. doi: 10.3390/jpm12111911

52. Tang, L, Chang, SJ, Chen, CJ, and Liu, JT. Non-invasive blood glucose monitoring technology: a review. Sensors (Basel, Switzerland). (2020) 20:6925. doi: 10.3390/s20236925

53. Paramastri, R, Pratama, SA, Ho, DKN, Purnamasari, SD, Mohammed, AZ, Galvin, CJ, et al. Use of mobile applications to improve nutrition behaviour: a systematic review. Comput Methods Prog Biomed. (2020) 192:105459. doi: 10.1016/j.cmpb.2020.105459

54. Eckstrom, E, Neukam, S, Kalin, L, and Wright, J. Physical activity and healthy aging. Clin Geriatr Med. (2020) 36:671–83. doi: 10.1016/j.cger.2020.06.009

55. Zangger, G, Bricca, A, Liaghat, B, Juhl, CB, Mortensen, SR, Andersen, RM, et al. Benefits and harms of digital health interventions promoting physical activity in people with chronic conditions: systematic review and meta-analysis. J Med Internet Res. (2023) 25:e46439. doi: 10.2196/46439

56. Maiello, A, Auriemma, E, De Luca Picione, R, Pacella, D, and Freda, MF. Giving meaning to non-communicable illness: mixed-method research on sense of grip on disease (SoGoD). Healthcare (Basel, Switzerland). (2022) 10:1309. doi: 10.3390/healthcare10071309

57. Riegel, B, Barbaranelli, C, Sethares, KA, Daus, M, Moser, DK, Miller, JL, et al. Development and initial testing of the self-care of chronic illness inventory. J Adv Nurs. (2018) 74:2465–76. doi: 10.1111/jan.13775

58. Mohan, A, Majd, Z, Johnson, ML, Essien, EJ, Barner, J, Serna, O, et al. A motivational interviewing intervention to improve adherence to ACEIs/ARBs among nonadherent older adults with comorbid hypertension and diabetes. Drugs Aging. (2023) 40:377–90. doi: 10.1007/s40266-023-01008-6

59. Shingleton, RM, and Palfai, TP. Technology-delivered adaptations of motivational interviewing for health-related behaviors: a systematic review of the current research. Patient Educ Couns. (2016) 99:17–35. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2015.08.005

60. Martirano, L, and Mitolo, M. Building automation and control systems (BACS): a review In: 2020 IEEE international conference on environment and electrical engineering and 2020 IEEE industrial and commercial power systems Europe (EEEIC / I&CPS Europe). New York City, USA: IEEE (2020). 1–8.

61. Woźniak, M, and Połap, D. Intelligent home systems for ubiquitous user support by using neural networks and rule-based approach. IEEE Trans Ind Inform. (2019) 16:2651–8. doi: 10.1109/TII.2019.2951089

62. Cicirelli, G, Marani, R, Petitti, A, Milella, A, and D'Orazio, T. Ambient assisted living: a review of technologies, methodologies and future perspectives for healthy aging of population. Sensors (Basel, Switzerland). (2021) 21:3549. doi: 10.3390/s21103549

63. Fernandes, CD. Hybrid indoor and outdoor localization for elderly care applications with LoRaWAN In: IEEE international symposium on medical measurements and applications (MeMeA). Bari, Italy: Institute of Electrical and Electronics Engineers Inc. (2020) 1–6.

64. El Murabet, A, Touhafi, A, Abtoy, A, and Tahiri, A. Ambient assisted living system’s models and architectures: a survey of the state of the art. J King Saud Univ Comput Inf Sci. (2020) 32:1–10. doi: 10.1016/j.jksuci.2018.04.009

65. Barnett, DW, Barnett, A, Nathan, A, Van Cauwenberg, J, and Cerin, ECouncil on Environment and Physical Activity (CEPA) – Older Adults working group. Built environmental correlates of older adults' total physical activity and walking: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act. (2017) 14:103. doi: 10.1186/s12966-017-0558-z

66. Song, Y, Liu, Y, Bai, X, and Yu, H. Effects of neighborhood built environment on cognitive function in older adults: a systematic review. BMC Geriatr. (2024) 24:194. doi: 10.1186/s12877-024-04776-x

67. Girdler, S, Packer, TL, and Boldy, D. The Impact of Age-Related Vision Loss. OTJR: OTJR. (2008) 28:110–120. doi: 10.3928/15394492-20080601-05

68. Ma, C, Guerra-Santin, O, and Mohammadi, M. Smart home modification design strategies for ageing in place: a systematic review. J Housing Built Environ. (2022) 37:625–51. doi: 10.1007/s10901-021-09888-z

69. De Luca, V, Tramontano, G, Riccio, L, Trama, U, Buono, P, Losasso, M, et al. "one health" approach for health innovation and active aging in Campania (Italy). Front Public Health. (2021) 9:658959. doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2021.658959

70. Ebrahimoghli, R, Pezeshki, MZ, Farajzadeh, P, Arab-Zozani, M, Mehrtak, M, and Alizadeh, M. Factors influencing social prescribing initiatives: a systematic review of qualitative evidence. Perspect Public Health. (2023) 145:157–66. doi: 10.1177/17579139231184809

71. Fancello, V, Hatzopoulos, S, Santopietro, G, Fancello, G, Palma, S, Skarżyński, PH, et al. Vertigo in the elderly: a systematic literature review. J Clin Med. (2023) 12:2182. doi: 10.3390/jcm12062182

72. Swenor, BK, Lee, MJ, Varadaraj, V, Whitson, HE, and Ramulu, PY. Aging With Vision Loss: A Framework for Assessing the Impact of Visual Impairment on Older Adults. The Gerontologist. (2020) 60:989–95. doi: 10.1093/geront/gnz117

Keywords: older adults, multimorbidity, frailty, polypharmacy, digital health, telemedicine, persona-based design, mixed-methods

Citation: De Luca V, Virgolesi M, Cuomo A, Lemmo D, Perillo M, Canfora F, Aprano S, Mezza F, Vetrani C, Freda MF, Adamo D, Rea T, Mercurio L, Attaianese E, Menditto E, Colao A, Iaccarino G and Illario M (2025) Digital interventions addressing the unmet needs of older adults with multimorbidity: a mixed-methods persona design approach. Front. Public Health. 13:1637748. doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2025.1637748

Edited by:

Yanwu Xu, Baidu, ChinaReviewed by:

Beenish Chaudhry, University of Louisiana at Lafayette, United StatesIzidor Mlakar, University of Maribor, Slovenia

Copyright © 2025 De Luca, Virgolesi, Cuomo, Lemmo, Perillo, Canfora, Aprano, Mezza, Vetrani, Freda, Adamo, Rea, Mercurio, Attaianese, Menditto, Colao, Iaccarino and Illario. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Vincenzo De Luca, dmluYy5kZWx1Y2FAZ21haWwuY29t

Vincenzo De Luca

Vincenzo De Luca Michele Virgolesi

Michele Virgolesi Alessandra Cuomo2

Alessandra Cuomo2 Daniela Lemmo

Daniela Lemmo Mariangela Perillo

Mariangela Perillo Federica Canfora

Federica Canfora Teresa Rea

Teresa Rea Lorenzo Mercurio

Lorenzo Mercurio Enrica Menditto

Enrica Menditto Guido Iaccarino

Guido Iaccarino Maddalena Illario

Maddalena Illario