- Day Surgery Center of General Practice Medical Center, West China Hosptial of Sichuan Universtiy, Chengdu, China

Background: Caregivers of patients with chronic respiratory diseases, such as heart failure, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, and asthma, often experience significant physical, emotional, and psychological strain. This study aims to evaluate the effectiveness of various interventions designed to reduce caregiver burden and improve caregiver well-being.

Design: Meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials (RCTs).

Methods: A comprehensive literature search was conducted across multiple electronic databases, identifying randomized controlled trials (RCTs) that assessed interventions aimed at reducing caregiver burden in caregivers of chronic dyspnea patients. A total of 25 RCTs, involving 2,425 participants, were included. The included studies evaluated a variety of interventions, including psychological support, education programs, and physical activity. Data were extracted and analyzed using standardized mean differences (SMD) to assess intervention effects, with heterogeneity and publication bias considered.

Results: A total of 25 RCTs involving 2,425 participants were included in the meta-analysis. Interventions significantly reduced caregiver burden (SMD = −0.65, 95% CI −0.96 to −0.34) with notable heterogeneity (I2 = 82.7%). Subgroup analysis showed a more pronounced reduction in studies conducted in Asia (SMD = −0.80). Improvements were also observed across caregiver burden categories, with the most significant reduction in social burden (SMD = −1.07). Family function improved (SMD = 0.53), but no significant change in social support (SMD = 0.55) or quality of life (SMD = 0.16) was found. Anxiety (SMD = −0.28) showed no significant reduction. Stress (SMD = −0.59) and depression (SMD = −0.45) were significantly reduced. Sensitivity analysis confirmed the robustness of the results.

Conclusion: Interventions significantly reduce caregiver burden, particularly in emotional, physical, and social aspects, with improvements in family function, stress, and depression. However, no substantial changes were observed in anxiety or quality of life. The evidence quality is moderate, and future studies should focus on improving methodological rigor and exploring long-term effects.

Tweetable abstract: Caregivers of chronic respiratory disease patients face significant strain. Our meta-analysis of 25 RCTs (2,425 participants) found that interventions significantly reduce caregiver burden, especially in emotional, physical, and social aspects, improving family function, stress, and depression. However, anxiety and quality of life showed no substantial changes. Future research should focus on long-term effects and methodological rigor.

Systematic review registration: https://www.crd.york.ac.uk/PROSPERO/, identifier CRD420251034352.

Introduction

Chronic respiratory diseases, such as chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), heart failure, and asthma, are leading causes of morbidity and mortality worldwide (1). Globally, COPD, heart failure and asthma affect more than 550 million adults, accounting for over 7% of the world’s population and contributing to more than 6 million deaths annually, ranking among the top five causes of mortality (2). Among which, most of patients with moderate-to-severe disease rely on informal family caregivers, whose depression, physical comorbidities and lost labor further amplify the economic impact on health systems. Current international standards—namely the 2024 Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease report (3), the 2023 European Society of Cardiology guidelines for HF (4), and the Global Initiative for Asthma strategy (5)—all recommend integrating patient self-management with caregiver support. Yet, these documents focus primarily on pharmacological and device-based management of patients, offering limited guidance on interventions specifically designed to alleviate caregiver burden. Across the continuum of COPD, heart failure and asthma care, family caregivers perform multifaceted tasks that extend from acute exacerbation management to long-term stability maintenance. Caregivers of patients with chronic dyspnea often experience high levels of physical, emotional, and psychological stress, which can lead to caregiver burnout and negatively impact their own health (6–9). The “caregiver-as-second-patient” framework advanced by Schulz and Sherwood posits that family caregivers of chronically ill patients constitute a distinct population at risk for parallel trajectories of physical morbidity, emotional distress, and diminished quality of life (10). Within this paradigm, caregivers are not merely ancillary resources for the patient, but rather “hidden patients” who require systematic screening, risk stratification, and evidence-based interventions in their own right. Consequently, any therapeutic strategy targeting patients with chronic breathlessness that overlooks the caregiver’s burden risks sub-optimal overall effectiveness. Given the growing global prevalence of chronic respiratory diseases, addressing caregiver burden has become an essential component of healthcare management.

Caregiver burden refers to the emotional, physical, and financial strain experienced by individuals who provide care for patients with chronic conditions (11, 12). In the context of chronic dyspnea, caregiver burden can be particularly pronounced due to the ongoing nature of the disease, the complexity of care, and the emotional toll of managing a patient’s condition over extended periods (6). High caregiver burden is associated with increased rates of anxiety, depression, stress, and decreased quality of life, which can further complicate caregiving and reduce the caregiver’s ability to provide optimal care (13). Therefore, identifying effective interventions that alleviate caregiver burden is crucial for improving both caregiver well-being and the overall caregiving process.

Numerous interventions have been proposed to reduce caregiver burden, ranging from psychological and emotional support to practical assistance and training in caregiving techniques (14, 15). However, the effectiveness of these interventions varies, and there is a need for a comprehensive understanding of which interventions are most effective in different contexts. This meta-analysis aims to assess the impact of various interventions on caregiver burden for individuals caring for patients with chronic dyspnea, by synthesizing data from randomized controlled trials (RCTs). Specifically, we focus on examining the effects of these interventions on emotional, social, financial, and physical dimensions of caregiver burden, as well as their impact on anxiety, stress, confidence, depression, family function, and quality of life.

By consolidating evidence from multiple studies, this meta-analysis seeks to provide a clearer understanding of the effectiveness of interventions in alleviating caregiver burden and improving the well-being of caregivers. The findings from this analysis may help inform healthcare policies and intervention strategies aimed at supporting caregivers, thereby enhancing the overall care and quality of life for both patients with chronic respiratory conditions and their caregivers.

Methods

Study design and overall framework

This study is a systematic review and meta-analysis designed to evaluate the efficacy of interventions in reducing caregiver burden among informal carers of patients with COPD, heart failure or asthma. The review was conducted in strict accordance with the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (version 6.4) and is reported following the PRISMA 2020 statement. The study protocol was prospectively registered with PROSPERO (registration number: CRD420251034352).

Data sources and search strategy

A comprehensive literature search was conducted from inception to 18 April 2025 in multiple electronic databases, including PubMed, Cochrane Library, Embase, and Web of Science. The search strategy was designed to capture RCTs that evaluated the effects of interventions on caregiver burden for caregivers of patients with chronic dyspnea. The search terms included combinations of the following keywords: “caregiver burden,” “chronic dyspnea,” “chronic respiratory disease,” “heart failure,” “COPD,” “asthma,” “caregiver interventions,” and “randomized controlled trial.” Detailed strategy was demonstrated in Supplementary Table 1. Additionally, relevant gray literature, such as conference abstracts and dissertations, were reviewed to minimize publication bias. The reference lists of included studies and relevant review articles were also manually searched for additional studies that met the inclusion criteria.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

The inclusion criteria for this meta-analysis were as follows: (1) Population: Informal, unpaid adult caregivers (older than 18 years) of community-dwelling patients with chronic respiratory diseases, including heart failure, COPD, asthma, or other chronic dyspnea conditions. (2) Any type of intervention aimed at reducing caregiver burden, including psychological support, education programs, training in caregiving techniques, or pharmacological treatments. (3) Studies were required to report at least one of the following outcomes: caregiver burden, anxiety, stress, depression, family function, quality of life, social support, or confidence in managing stress. (4) Studies had to be RCTs. (5) The research was published from inception to 18 April 2025. Exclusion criteria were applied to remove non-randomized trials, observational studies, and studies that did not involve structured interventions or report on caregiver burden or related outcomes. Additionally, studies involving caregivers of patients with diseases unrelated to chronic dyspnea or respiratory diseases were excluded. Finally, the entire selection process was managed in EndNote X9.

Quality assessment and data extraction

Two reviewers independently assessed the quality of the included studies using the RoB 2.0 tool for randomized trials, which evaluates risk of bias across five domains: randomization process, deviations from intended interventions, missing outcome data, measurement of outcomes, and selection of the reported result. During the assessment, the randomization process was assessed by random allocation and baseline differences, the deviation from intended interventions was assessed by application of blinding. Any disagreements between the reviewers were resolved through discussion or consultation with a third reviewer. Data extraction was performed independently by two reviewers using a pre-designed data extraction form. The following data were extracted from each included study: study characteristics, population characteristics, intervention details, and outcomes.

Statistical analysis

All statistical analyses were conducted using Stata 15 software. The effect size for continuous outcomes was expressed as standardized mean difference (SMD). A negative SMD indicates a reduction in caregiver burden or improvement in outcomes in the experimental group compared to the control group, while a positive SMD indicates the opposite. Heterogeneity among studies was assessed using the I2 statistic and Cochran’s Q test. If significant heterogeneity was found (I2 > 50%), a random-effects model was used to pool the effect sizes; otherwise, a fixed-effects model was used. Subgroup analyses were conducted to explore potential sources of heterogeneity based on factors such as study region, type of chronic respiratory disease, and duration of the intervention. Sensitivity analyses were performed by sequentially removing each study from the analysis to assess the robustness of the findings. Publication bias was assessed using Egger’s test when more than 10 studies contributed to a meta-analysis, and the trim-and-fill method was applied if publication bias was detected. The overall certainty of the evidence was assessed using the Grading of Recommendations Assessment, Development, and Evaluation (GRADE) system. Finally, Test Sequential Analysis (TSA) was employed to determine the required information size (RIS) and visualize the cumulative Z-curve to ensure statistical significance and rule out random variation in the results. The significance level for all statistical tests was set at p < 0.05.

Ethical considerations

This meta-analysis was based on previously published studies, so ethical approval was not required. However, all studies included in the analysis were required to have received appropriate ethical approval by their respective institutional review boards or ethics committees.

Results

Research selection

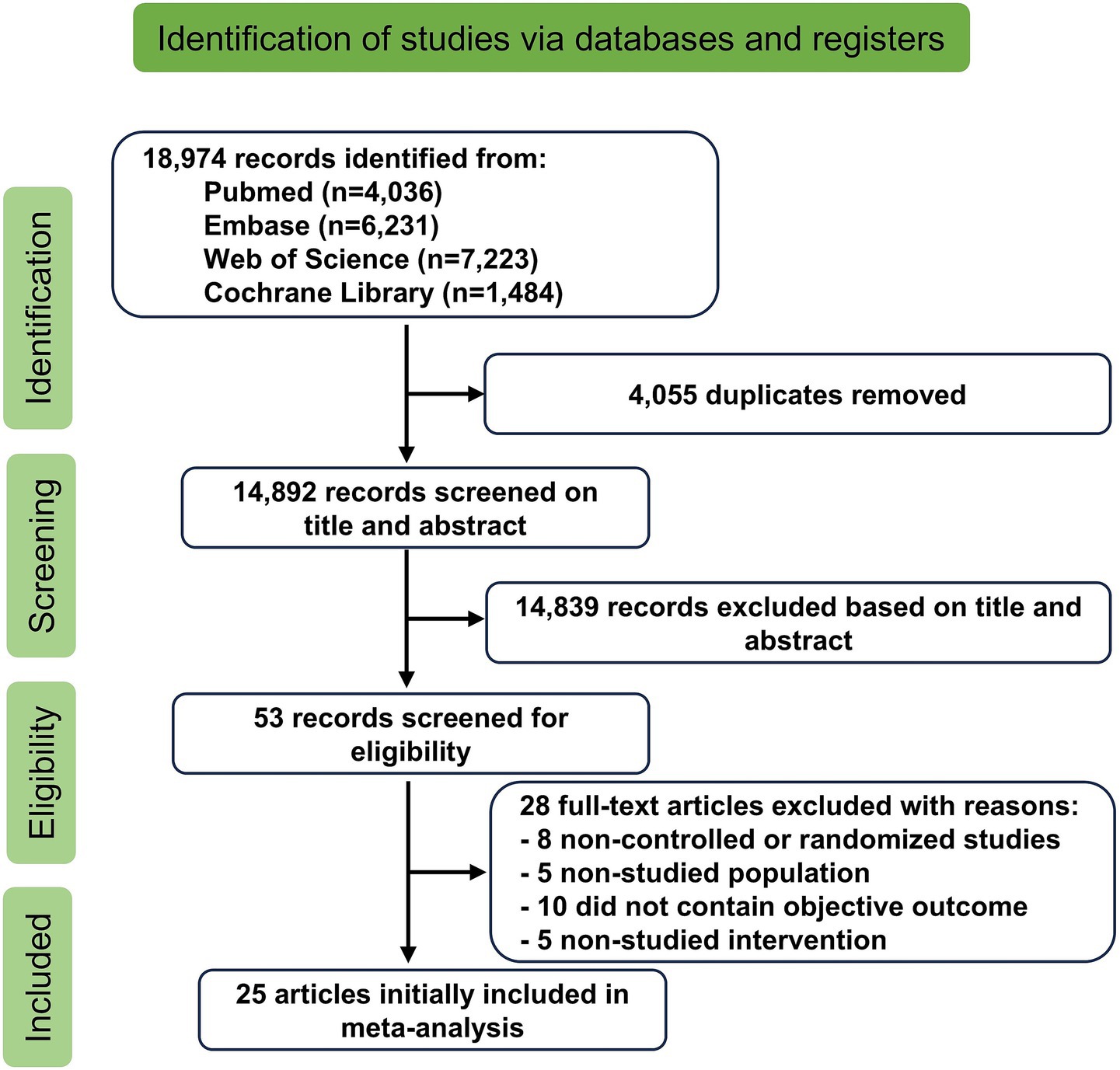

A total of 18,974 studies were initially identified through database searches and other sources. After removing duplicates, 14,892 studies remained. Following a screening of titles and abstracts, 14,839 unrelated studies were excluded. A full-text review resulted in the exclusion of an additional 28 studies for various reasons: 8 were not RCTs (16–23), 5 involved unrelated populations (24–28), 10 did not measure the intended outcomes (29–38), and 5 lacked the relevant interventions (39–43). In total, 25 RCTs were included in the systematic evaluation (44–68). The study selection process is illustrated in Figure 1.

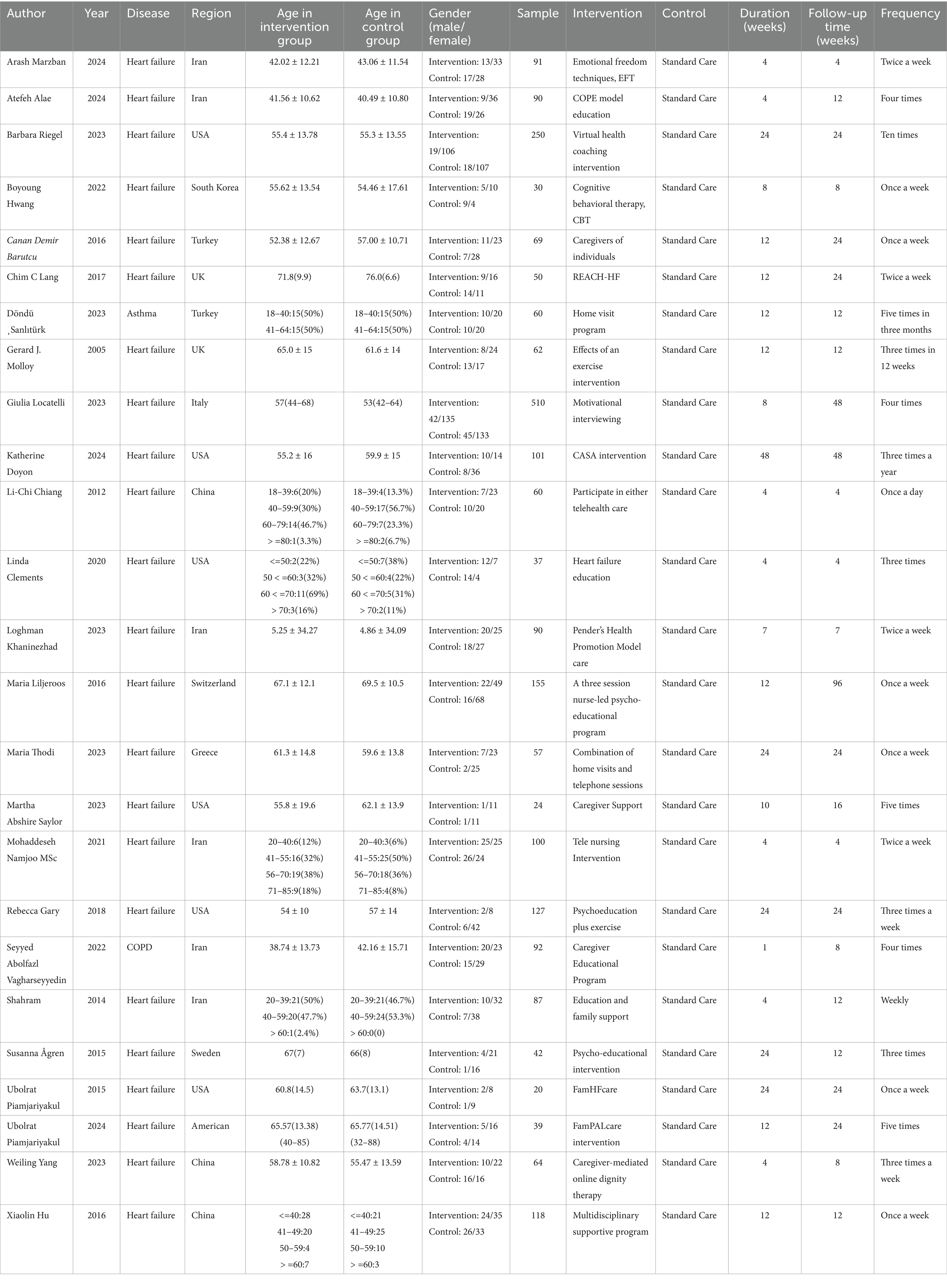

Description of included studies

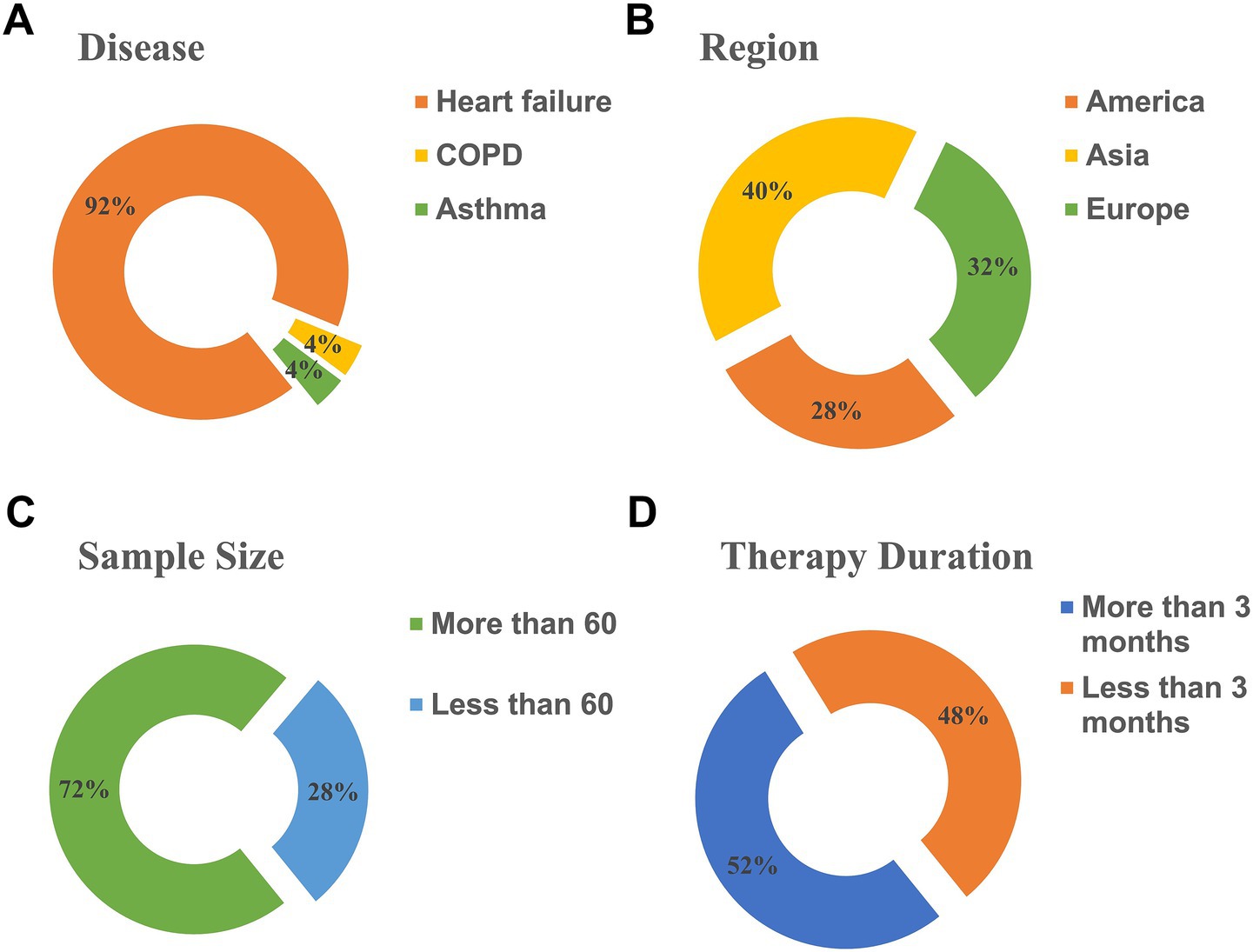

Twenty-five studies were included, involving 2,425 participants. Of these, 23 studies focused on caregivers of patients with heart failure, 1 study focused on COPD, and 1 study on asthma. Seven studies were conducted in the United States, 10 in Asia, and 8 in Europe. Sample sizes ranged from 20 to 510 participants; 18 studies included more than 60 individuals, while 7 studies had fewer than 60. Regarding the duration of interventions, 12 studies lasted less than 3 months, while 13 lasted longer than 3 months. The basic characteristics of the included studies are summarized in Figure 2 and Table 1.

Figure 2. Characteristics of studies included in the analysis. (A) Diseases. (B) Region. (C) Sample size. (D) Therapy duration.

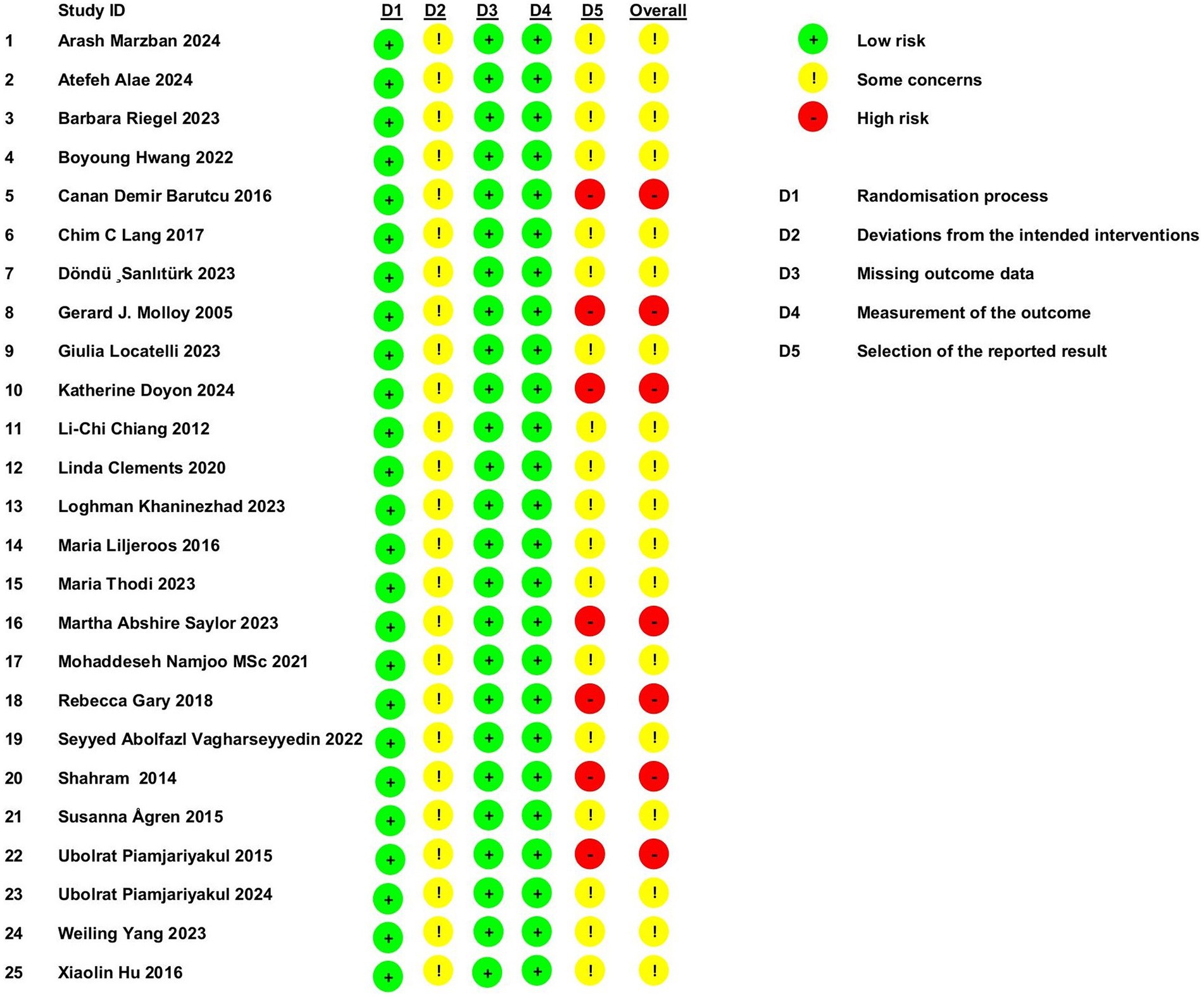

Risk of bias assessment

According to the RoB 2.0 tool for assessing the risk of bias in randomized trials, the following observations were made: All studies employed random allocation and showed no baseline differences, suggesting a low risk of bias in the randomization process. However, none of the studies employed blinding, raising concerns about potential deviations in the delivery of the interventions. All studies reported complete data, minimizing the risk of bias in this domain. Objective outcome measures were used, which further reduced the risk of bias in outcome assessment. Seven studies were deemed high risk due to inadequate methods for measuring outcomes, and 18 studies raised concerns about selective reporting, lacking adequate justification for outcome measures. These findings are summarized in Figure 3.

Meta-analysis

Improvement in caregiver burden

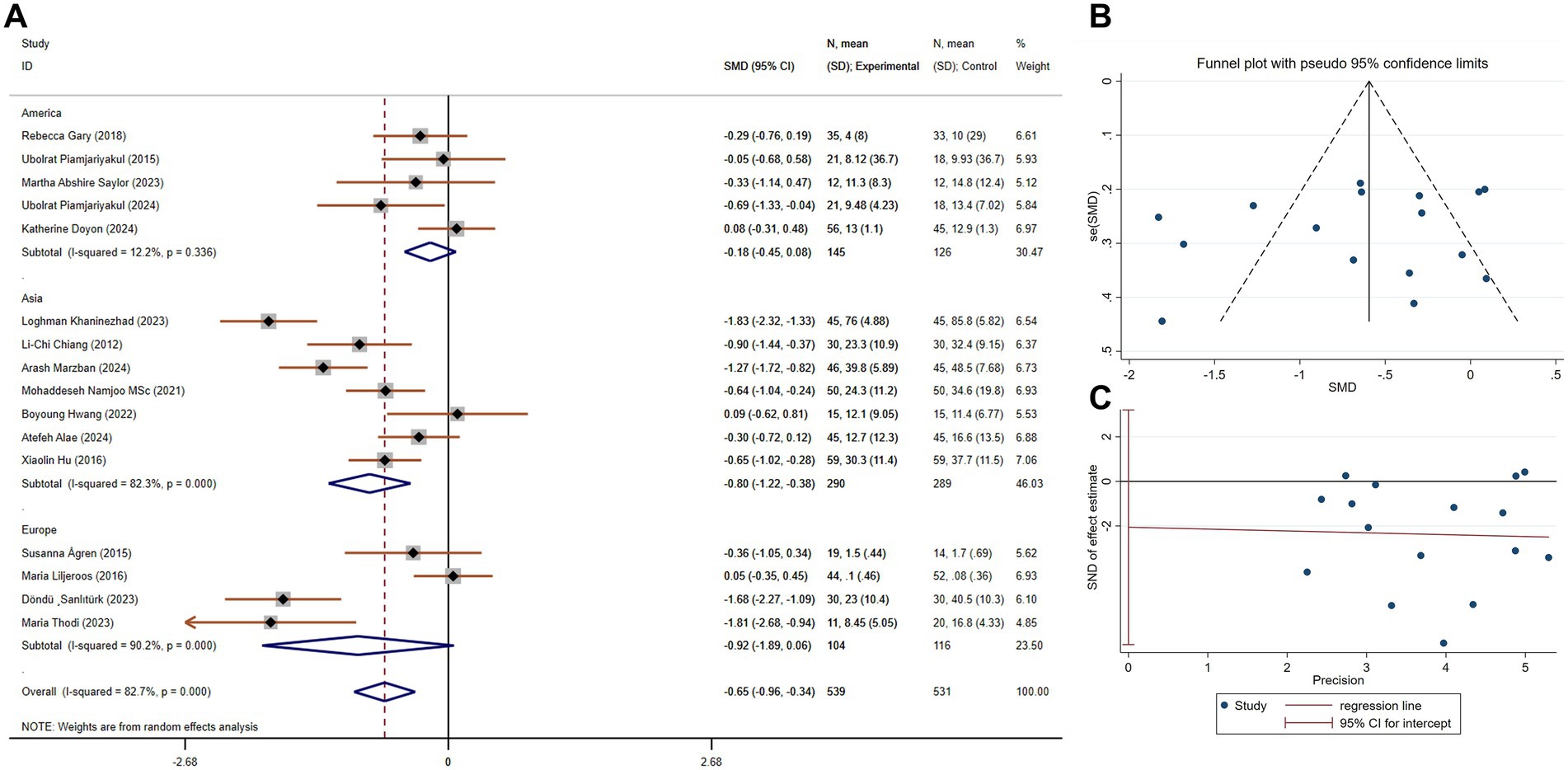

Caregiver burden is a critical measure for understanding the emotional, physical, and financial strain experienced by those caring for patients with chronic conditions like chronic dyspnea. A reduction in caregiver burden can prevent burnout, enhance caregivers’ ability to provide care, and potentially improve patient outcomes by allowing caregivers to continue their role with better health and support. A total of 16 studies, involving 1,070 participants (539 in the experimental group and 531 in the control group), compared caregiver burden. These studies showed significant heterogeneity (p < 0.001, I2 = 82.7%). Using a random-effects model, the pooled SMD was −0.65 (95% CI −0.96 to −0.34), indicating a statistically significant reduction in caregiver burden in the experimental group compared to the control group. A subgroup analysis based on study region revealed that studies conducted in Asia showed a more pronounced reduction in caregiver burden (SMD = −0.80, 95% CI −1.22 to −0.38), with some reduction in heterogeneity (Figure 4A). No publication bias was detected via Egger’s test (p = 0.416, Figures 4B,C).

Figure 4. The effect size and 95% CI for intervention on caregiver burden. (A) Forest plot. (B) Funnel plot. (C) Egger’s test results. SMD, standard mean differences; CI, confidence intervals.

Improvement in categories of caregiver burden

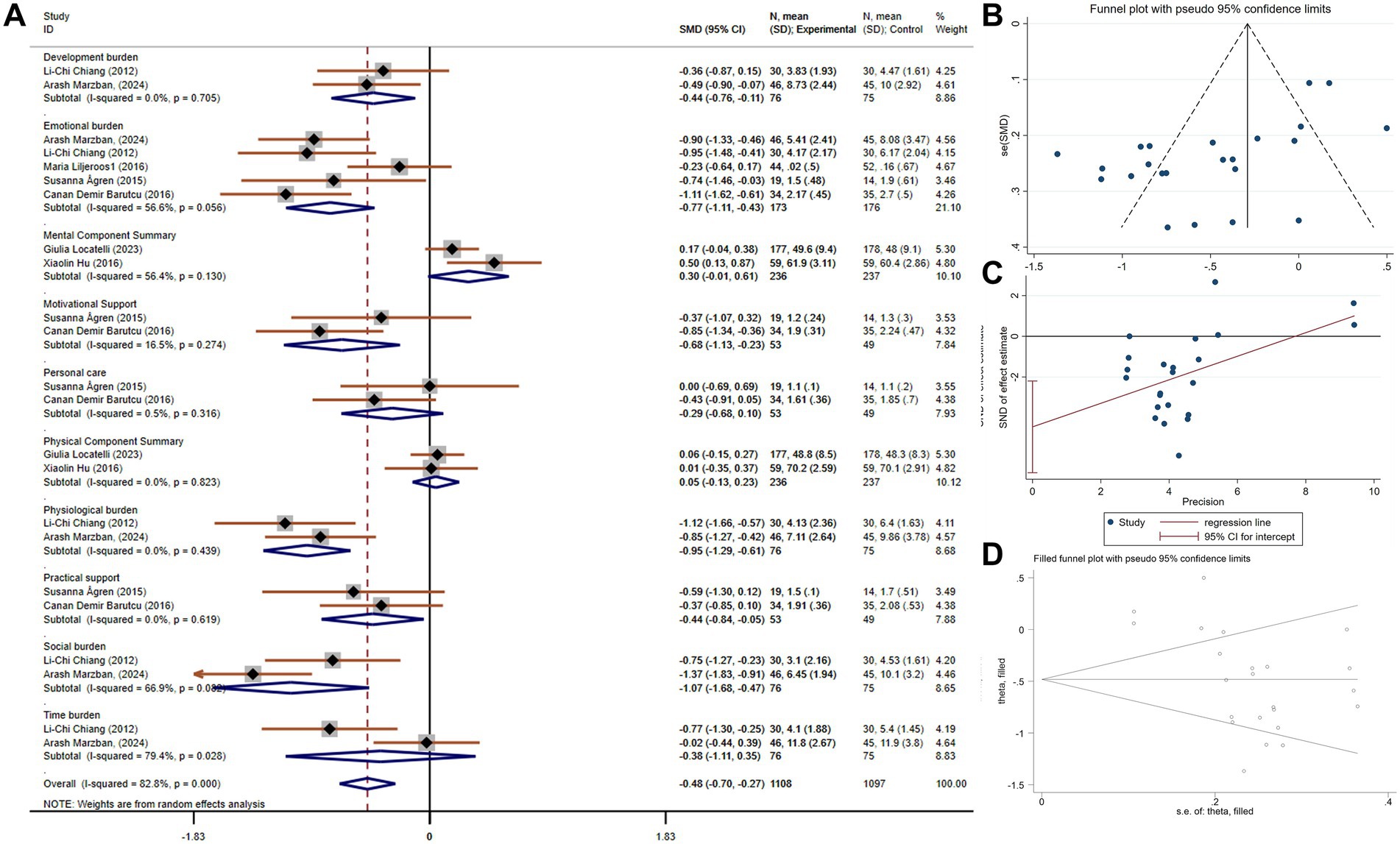

Caregiver burden can be broken down into various categories, such as emotional, social, financial, and physical burden. Each of these categories impacts the caregiver in different ways. Twenty-three studies, involving 2,205 participants (1,108 in the experimental group and 1,097 in the control group), compared categories of caregiver burden. These studies exhibited substantial heterogeneity (p < 0.001, I2 = 82.8%). The pooled SMD, derived from a random-effects model, was −0.48 (95% CI −0.70 to −0.27), indicating significant improvement across all categories of caregiver burden in the experimental group. A subgroup analysis by category of burden showed the most significant improvement in social burden (SMD = −1.07, 95% CI −1.68 to −0.47, Figure 5A). Publication bias was present in this analysis (p = 0.001, Figures 5B,C), but further examination with the trim-and-fill method indicated that this bias did not substantially affect the results (i.e., no trimming was necessary as the data remained unchanged, Figure 5D).

Figure 5. The effect size and 95% CI for intervention on categories of caregiver burden. (A) Forest plot. (B) Funnel plot. (C) Egger’s test results. (D) Trim and fill method application. SMD, standard mean differences; CI, confidence intervals.

Improvement in family function

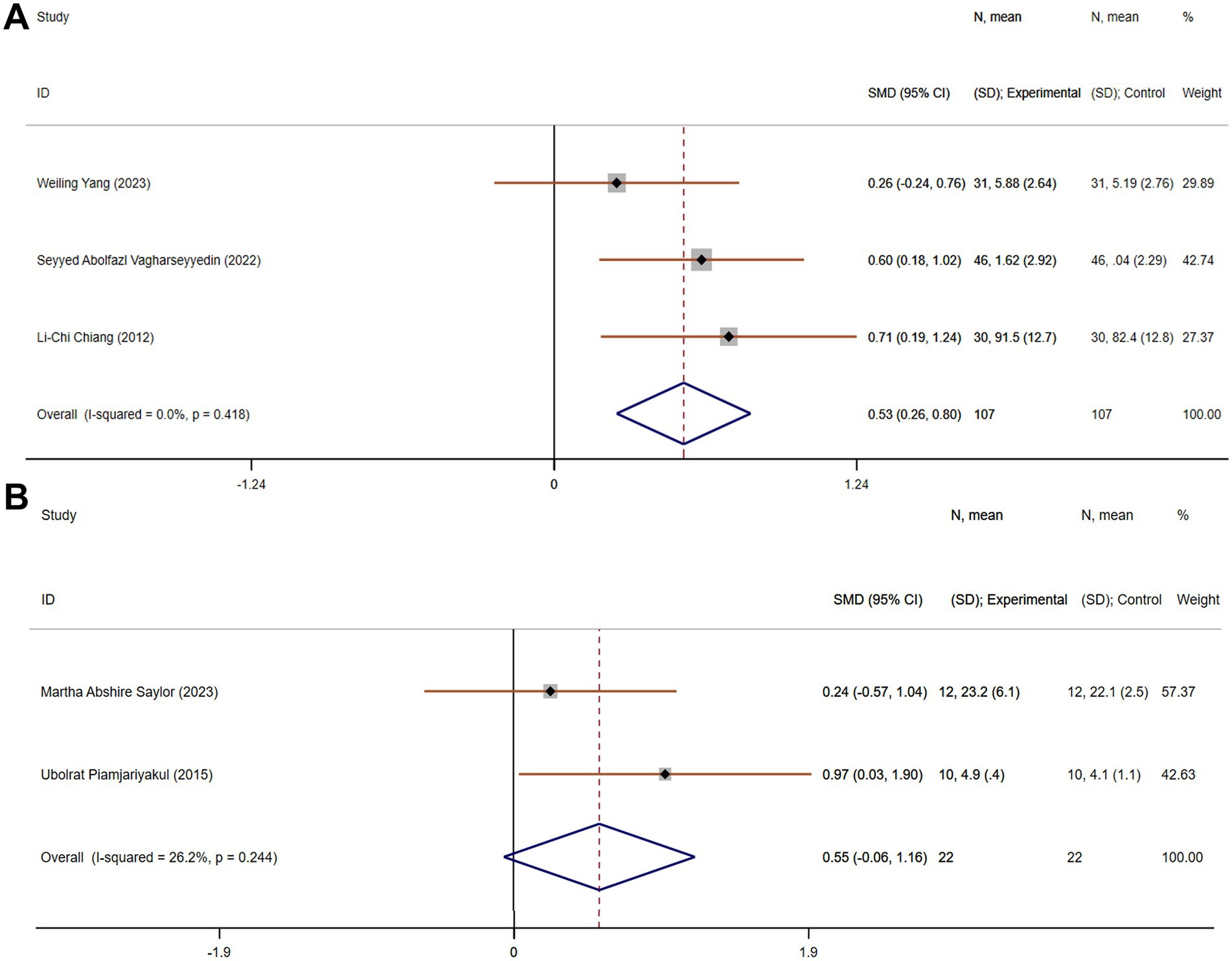

Family function reflects the dynamics within a caregiver’s household and the ability of family members to support one another. Improving family function can strengthen the emotional and logistical support systems for caregivers, making caregiving tasks more manageable and reducing the overall strain. Four studies comparing family function included 214 participants (107 in each group). There was no heterogeneity (p = 0.418, I2 = 0). Using a fixed-effects model, the pooled SMD was 0.53 (95% CI 0.26 to 0.80), indicating a significant improvement in family function in the experimental group compared to the control group (Figure 6A).

Figure 6. The effect size and 95% CI for intervention on family function and social support. (A) Forest plot of family function. (B) Forest plot of social support. SMD, standard mean differences; CI, confidence intervals.

Improvement in social support

Social support is crucial for caregivers, as it provides emotional reassurance, practical help, and an outlet for stress. Two studies, with a total of 44 participants (22 in each group), assessed social support. These studies exhibited acceptable heterogeneity (p = 0.244, I2 = 26.2%). The pooled SMD, derived from a fixed-effects model, was 0.55 (95% CI −0.06 to 1.16), suggesting no statistically significant improvement in social support in the experimental group compared to the control group (Figure 6B).

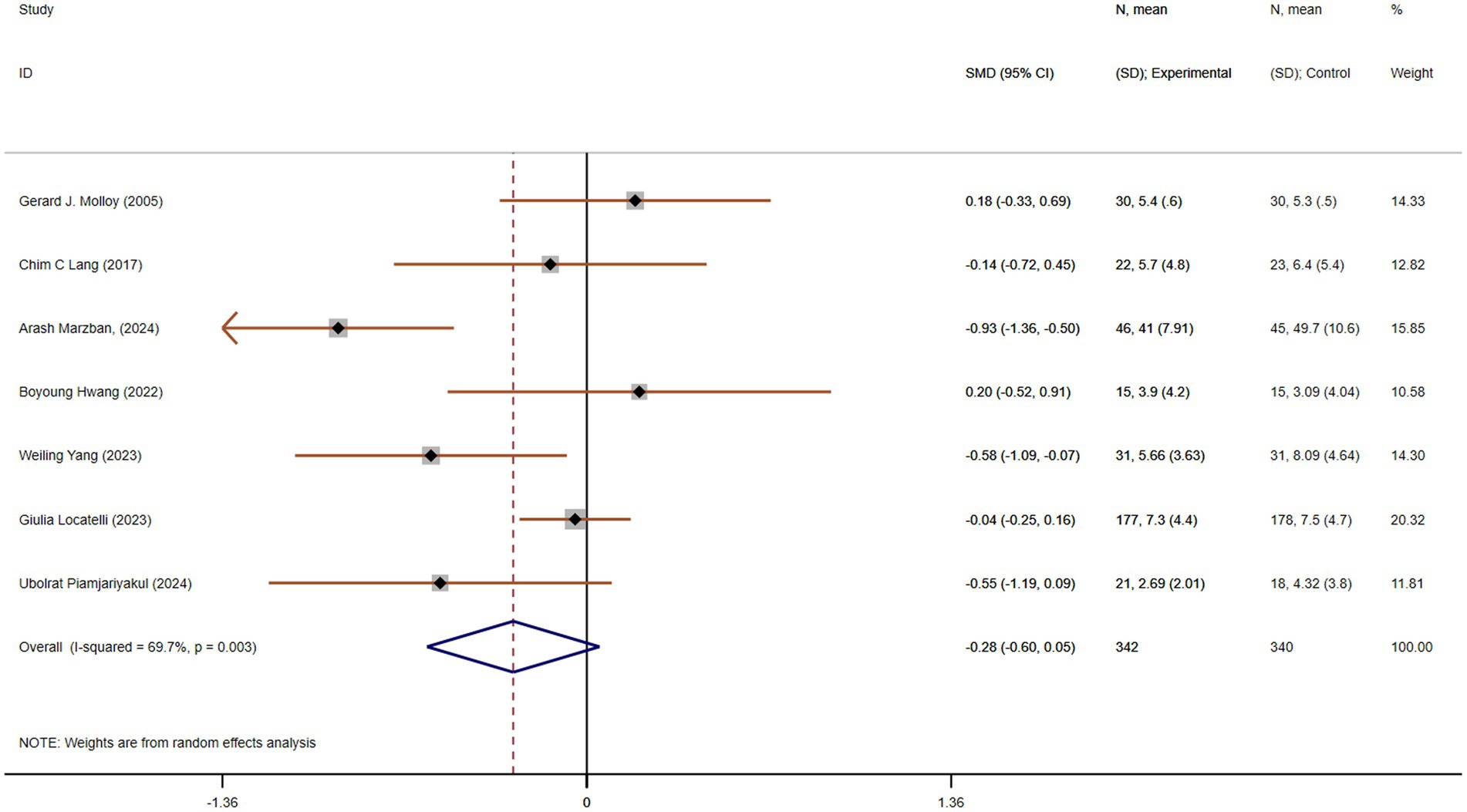

Improvement in anxiety

Anxiety is a common emotional response among caregivers, particularly those caring for individuals with chronic conditions. Chronic stress and anxiety can negatively affect caregivers’ physical and mental health, leading to fatigue, depression, and burnout. Seven studies, with a total of 682 participants (342 in each group), compared anxiety. These studies showed moderate heterogeneity (p = 0.003, I2 = 69.7%). The pooled SMD, derived from a random-effects model, was −0.28 (95% CI −0.60 to 0.05), indicating no statistically significant reduction in anxiety in the experimental group compared to the control group (Figure 7). Subgroup analysis based on the region or intervention duration showed a decreased heterogeneity, indicating region or intervention duration might be the cause of heterogeneity (Supplementary Figure 1).

Figure 7. The effect size and 95% CI for intervention on anxiety. SMD, standard mean differences; CI, confidence intervals.

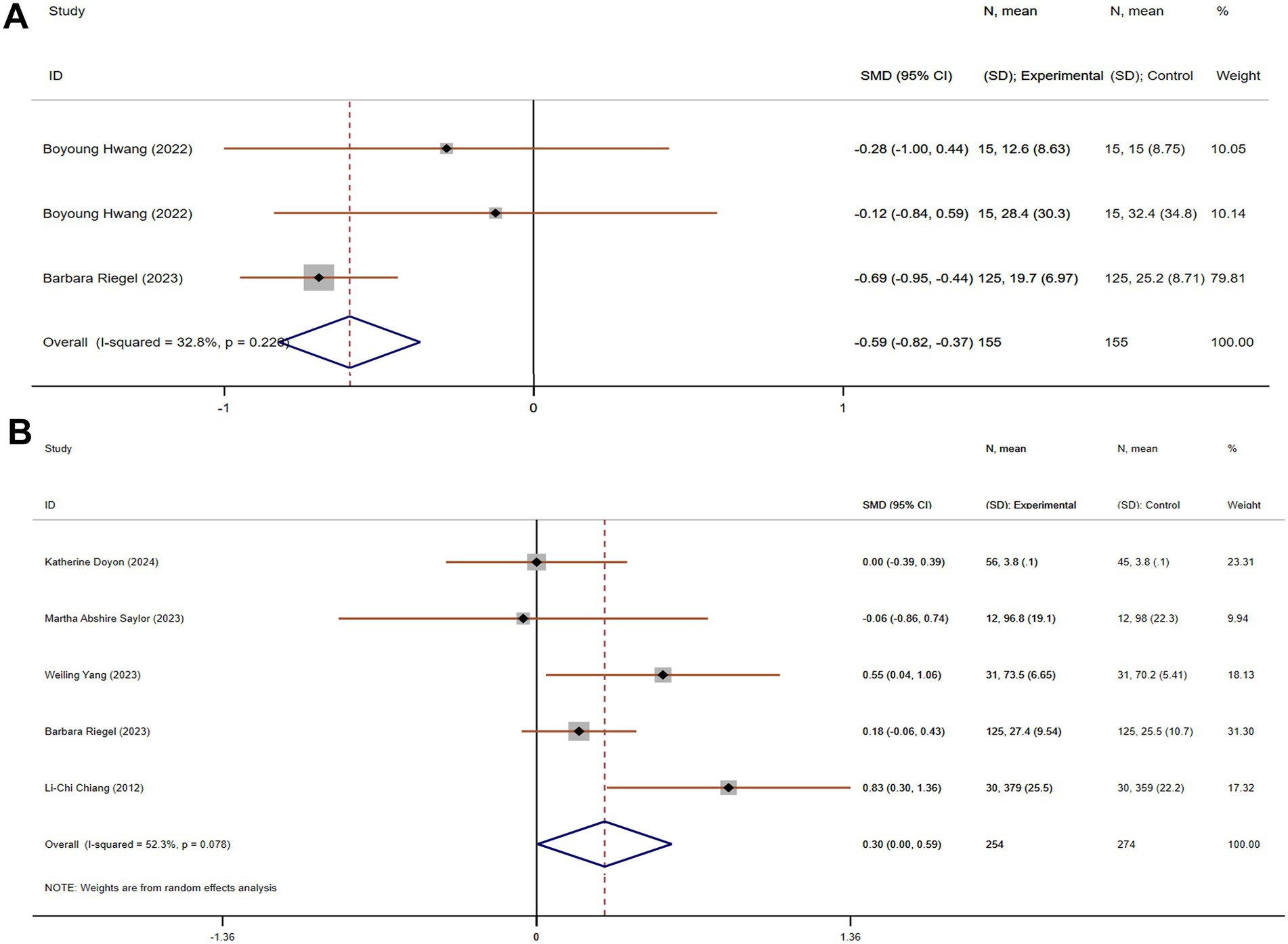

Improvement in stress

Stress is a key factor contributing to caregiver burden, particularly for those caring for individuals with chronic, life-limiting conditions like chronic dyspnea. Chronic stress can lead to various health issues, including cardiovascular problems, insomnia, and depression. Three studies, including 310 participants (155 in each group), compared stress. These studies showed acceptable heterogeneity (p = 0.228, I2 = 32.8%). The pooled SMD, derived from a fixed-effects model, was −0.59 (95% CI −0.82 to −0.37), indicating a statistically significant reduction in stress in the experimental group compared to the control group (Figure 8A).

Figure 8. The effect size and 95% CI for intervention on stress and confidence facing stress. (A) Forest plot of family function. (B) Forest plot of social support. SMD, standard mean differences; CI, confidence intervals.

Improvement in confidence for facing stress

Confidence in managing stress is an important predictor of how well caregivers can cope with their responsibilities. Caregivers with higher confidence are less likely to feel overwhelmed and are better equipped to handle challenging situations. Five studies, with 528 participants (254 in the experimental group and 274 in the control group), compared confidence for facing stress. These studies showed acceptable heterogeneity (p = 0.078, I2 = 52.3%). Using a random-effects model, the pooled SMD was 0.30 (95% CI 0.00 to 0.59), suggesting a statistically significant improvement in confidence for facing stress in the experimental group compared to the control group (Figure 8B).

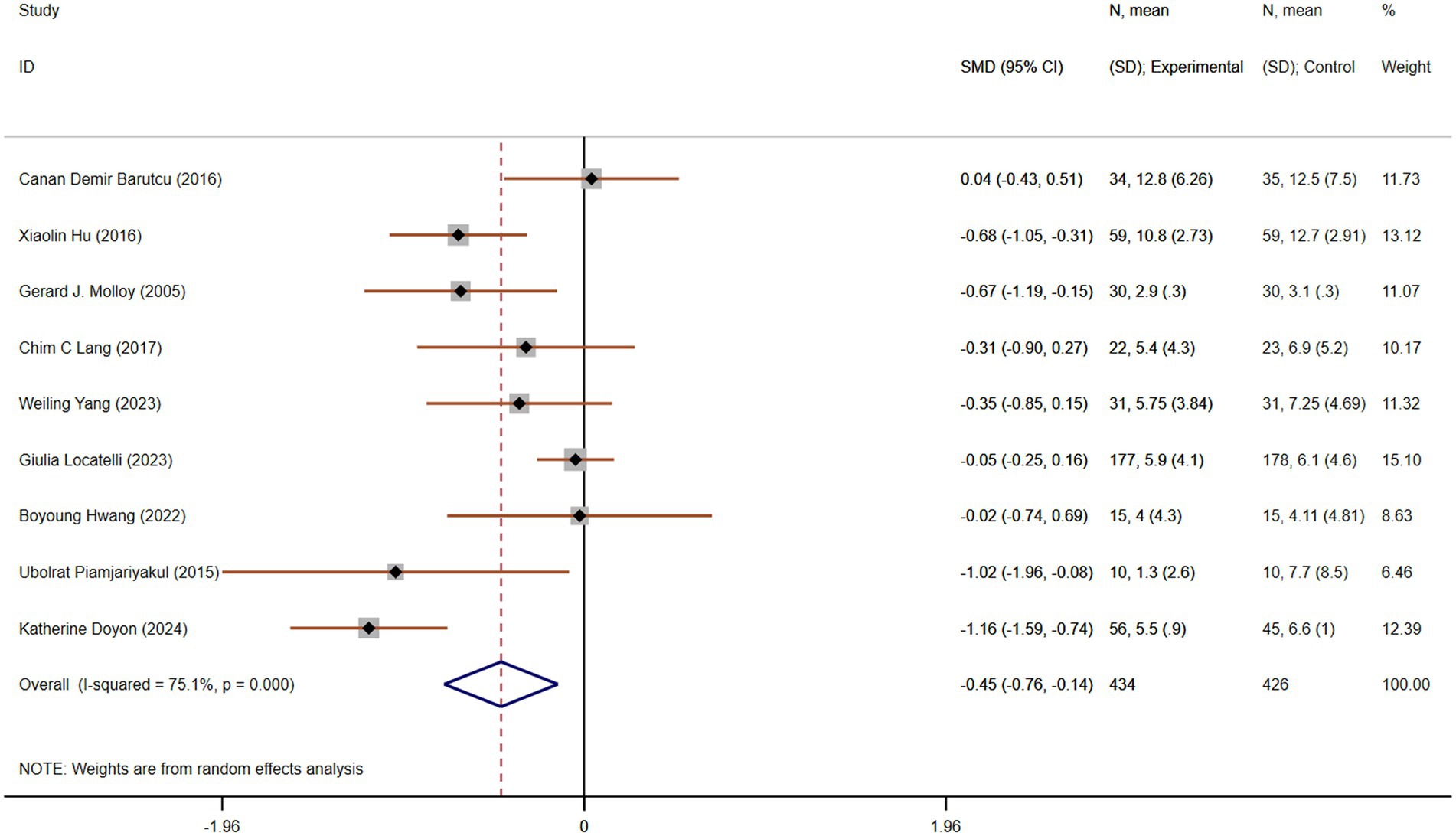

Improvement in depression

Depression is a significant concern for caregivers, as the emotional toll of caregiving can lead to or exacerbate existing mental health issues. Nine studies, involving 860 participants (434 in the experimental group and 426 in the control group), compared depression. These studies showed moderate heterogeneity (p < 0.001, I2 = 75.1%). The pooled SMD, derived from a random-effects model, was −0.45 (95% CI −0.76 to −0.14), indicating a statistically significant reduction in depression in the experimental group compared to the control group (Figure 9). Subgroup analysis based on the region or intervention duration showed a decreased heterogeneity, indicating region or intervention duration might be the cause of heterogeneity (Supplementary Figure 1).

Figure 9. The effect size and 95% CI for intervention on depression. SMD, standard mean differences; CI, confidence intervals.

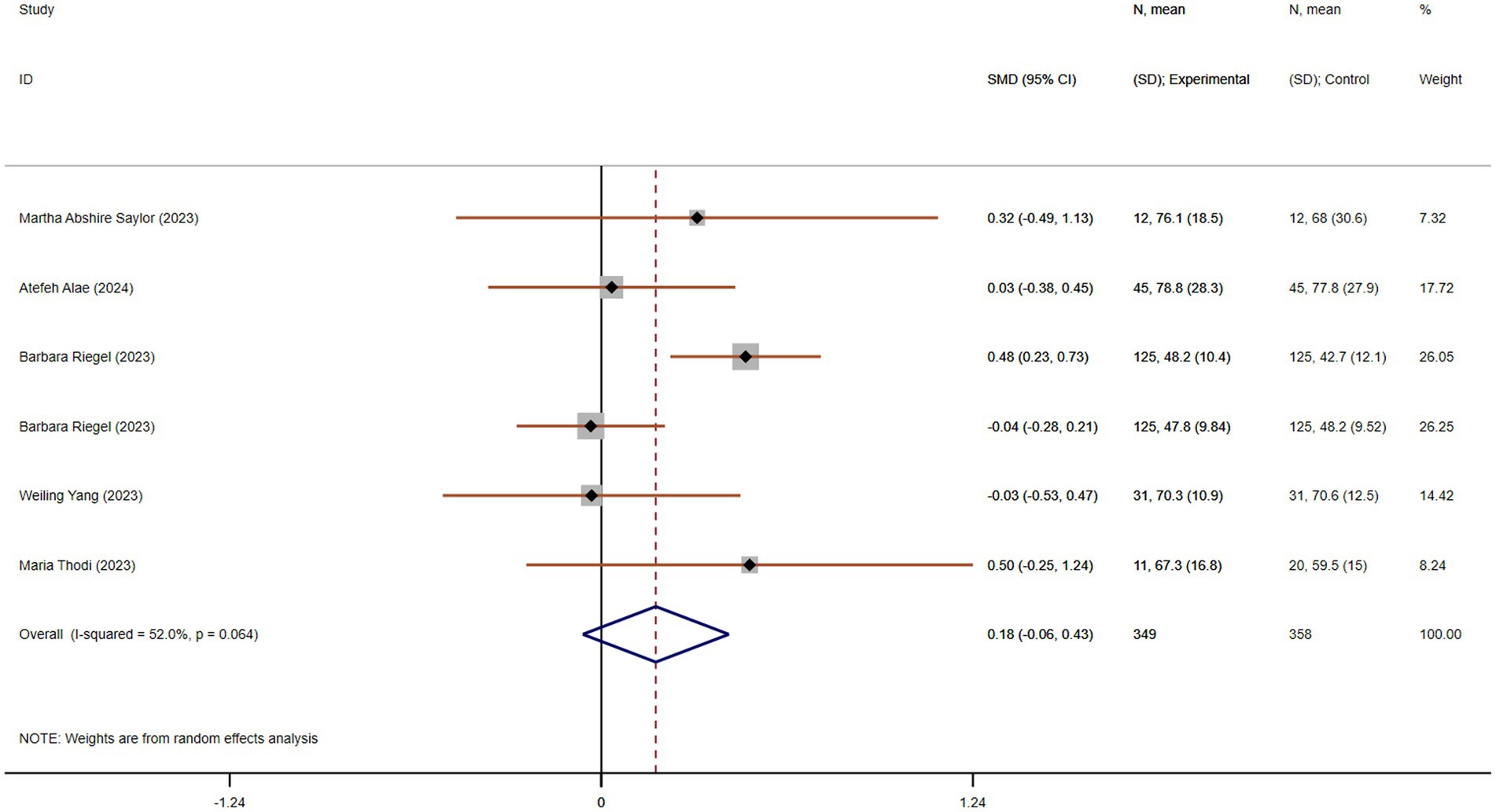

Improvement in quality of life

Quality of life is a comprehensive measure that captures the physical, emotional, and social well-being of caregivers. Their role over the long term. Six studies, with 707 participants (349 in the experimental group and 358 in the control group), compared quality of life. These studies showed acceptable heterogeneity (p = 0.064, I2 = 52.0%). The pooled SMD, derived from a random-effects model, was 0.16 (95% CI −0.06 to 0.43), suggesting no statistically significant improvement in quality of life in the experimental group compared to the control group (Figure 10). Subgroup analysis based on the region or intervention duration showed a decreased heterogeneity, indicating region or intervention duration might be the cause of heterogeneity (Supplementary Figure 1).

Figure 10. The effect size and 95% CI for intervention on quality of life. SMD, standard mean differences; CI, confidence intervals.

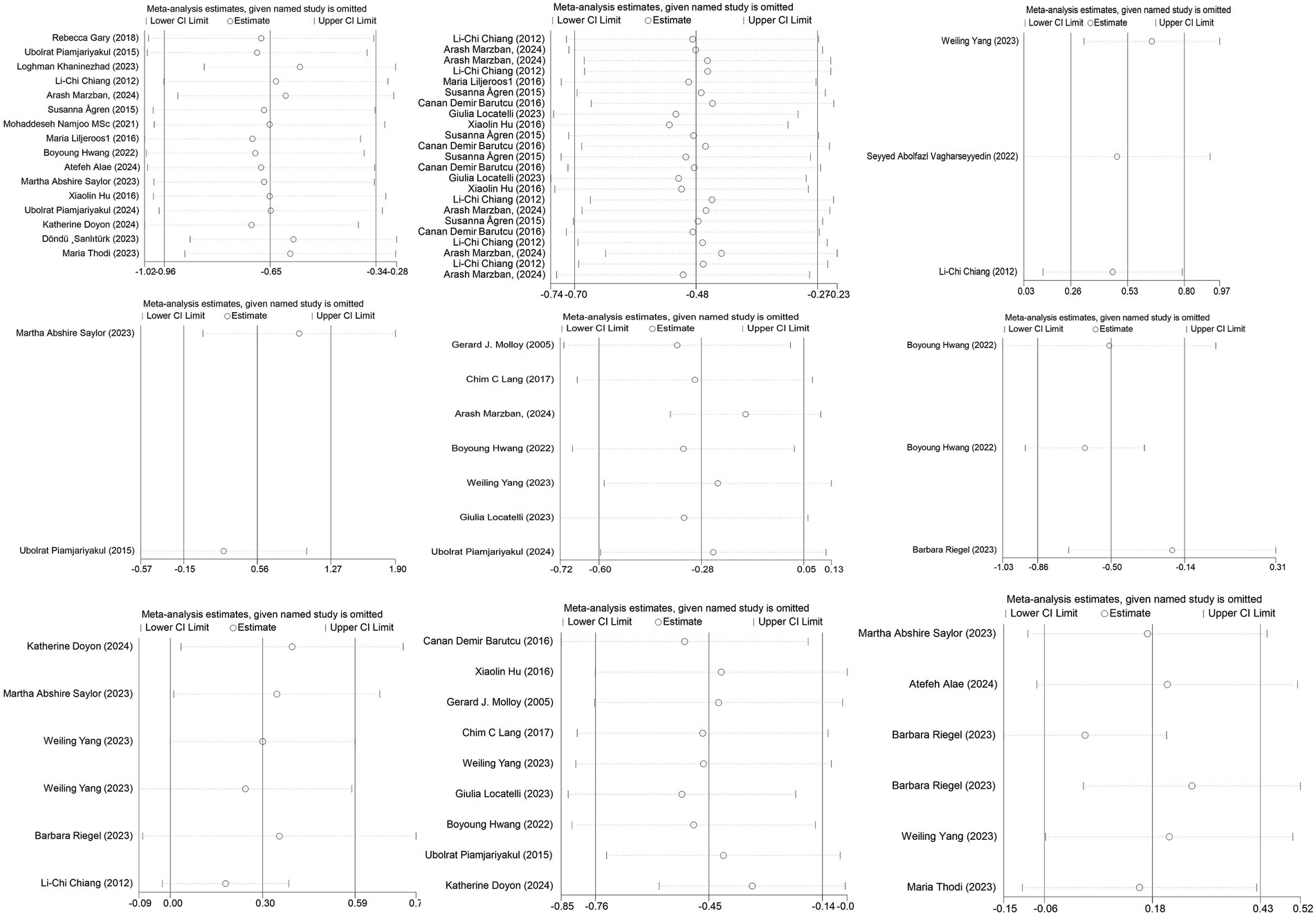

Sensitivity analysis

Sensitivity analyses, performed by systematically excluding one study at a time, revealed consistent results, without significant changes in the outcomes (see Figure 11). This reinforces the validity and reliability of the analysis, indicating that the overall findings are robust and not unduly influenced by any single study.

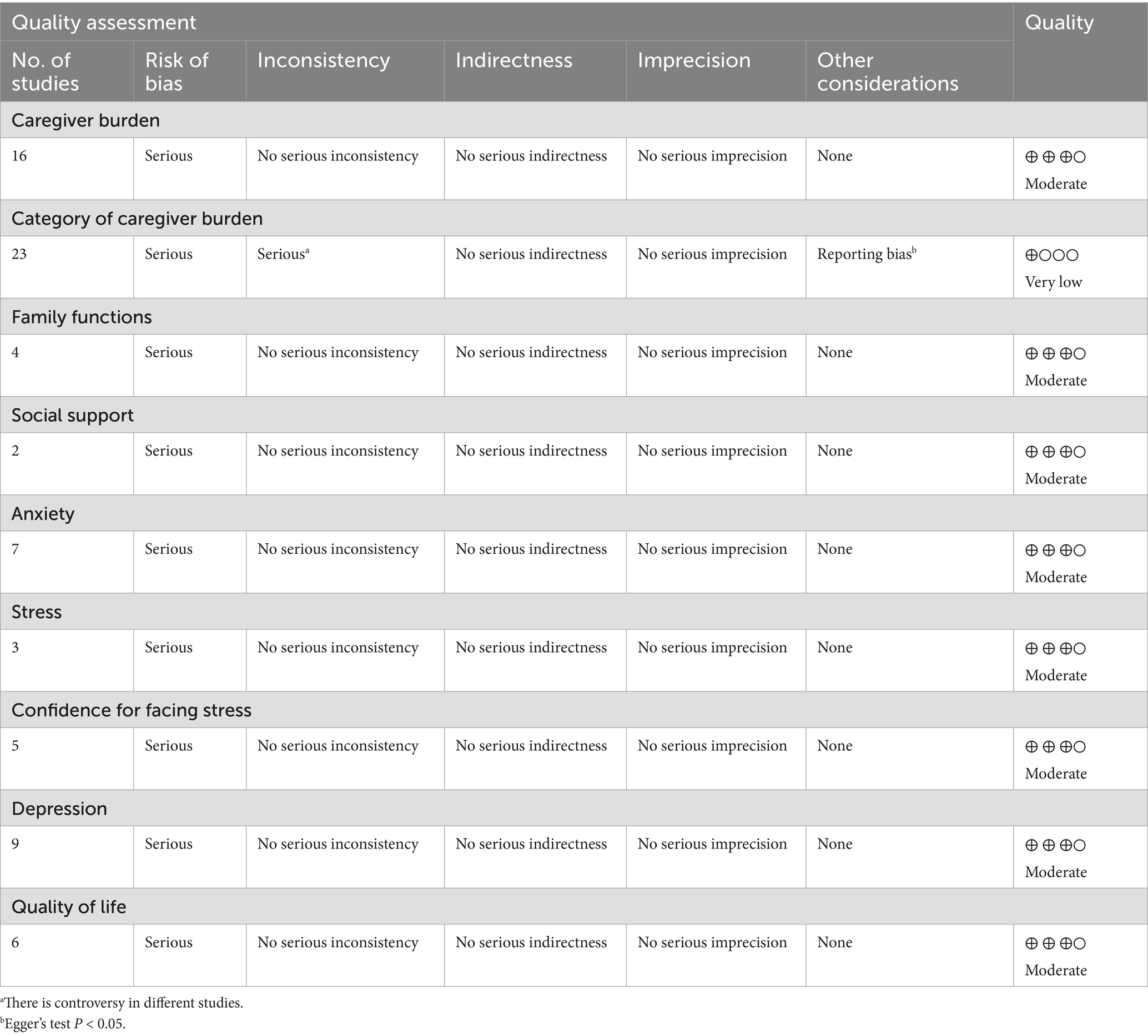

Certainty of the evidence

Based on the assessment of bias risk, reporting bias, and consistency across trials, the evidence was graded as follows: moderate quality for caregiver burden, family function, social support, anxiety, stress, confidence for facing stress, depression, and quality of life. The evidence for the categories of caregiver burden was graded as very low quality (see Table 2). These quality assessments highlight areas where further research is needed to strengthen the evidence base.

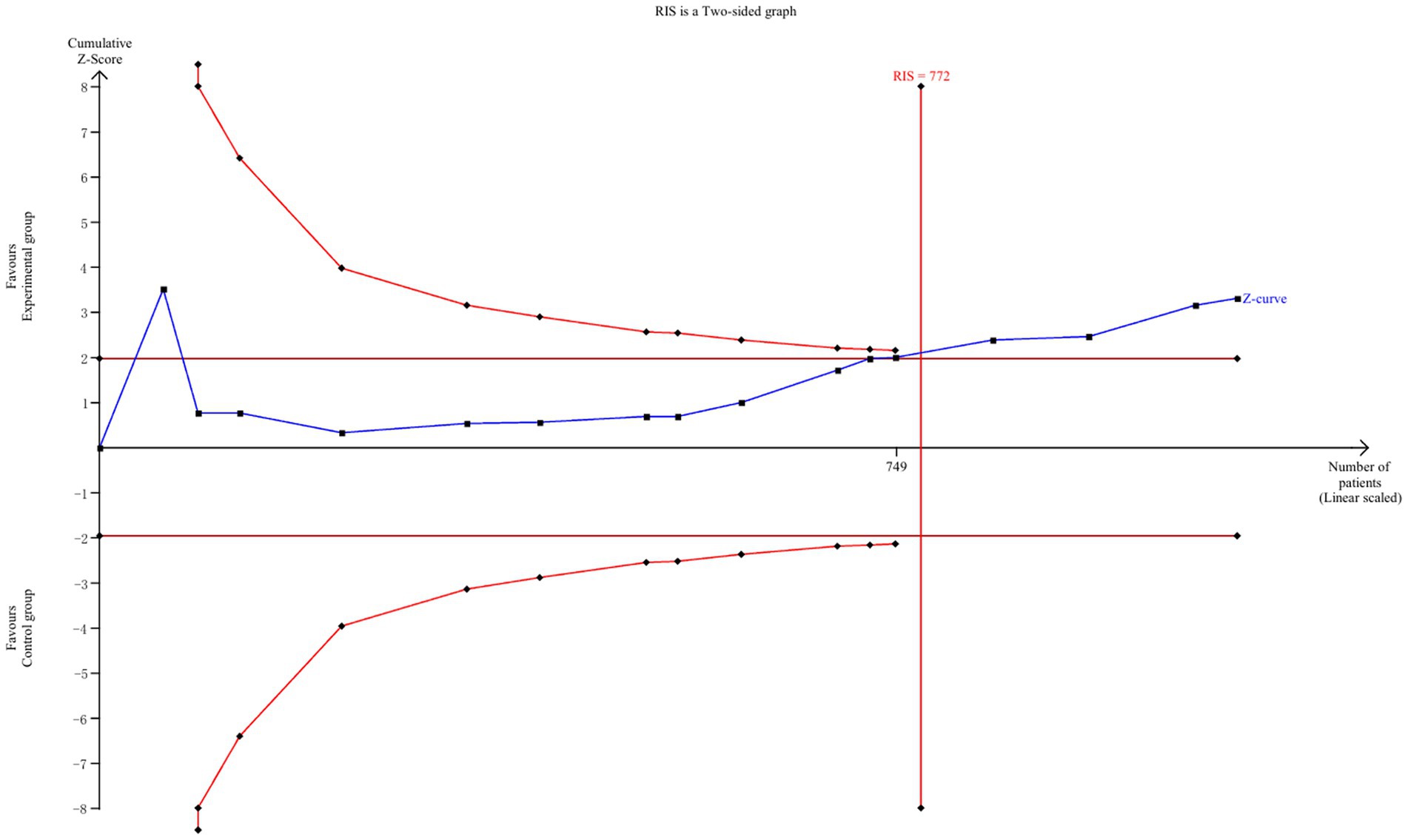

Test sequential analyses

The TSA boundary graph depicting the effects of interventions on caregiver burden for caregivers of chronic dyspnea patients, based on the RIS, is shown in the Figure 12. The RIS is 772, and the cumulative Z-curve crosses both the traditional boundary (Z = 1.96) and the RIS, suggesting that the experimental group experienced a lower burden than the control group, with false positive results ruled out.

Figure 12. TSA for intervention on caregiver burden. TSA, trial sequential analysis; RIS, required information size.

Discussion

This meta-analysis aimed to assess the impact of various interventions on the caregiver burden of individuals caring for patients with chronic dyspnea. A total of 25 RCTs were included, providing a comprehensive view of interventions aimed at alleviating the emotional, physical, and financial strain experienced by caregivers. The analysis identified significant improvements across multiple aspects of caregiver burden, with notable variation in the outcomes based on region, intervention type, and specific burden categories.

The pooled analysis of 16 studies involving 1,070 participants demonstrated a significant reduction in overall caregiver burden in the experimental group compared to the control group (SMD = −0.65). The substantial heterogeneity observed (I2 = 82.7%) suggests that various factors, such as study design, population characteristics, and types of interventions, may have contributed to the variability in results. Notably, studies conducted in Asia reported a more pronounced reduction in caregiver burden (SMD = −0.80), which may be attributed to cultural differences in caregiving practices, the type of interventions employed, or the specific characteristics of caregiver populations in these regions (69–71).

Further analysis of subcategories of caregiver burden revealed that the most significant improvements occurred in the social burden domain (SMD = −1.07), indicating that interventions were particularly effective in reducing the social strain caregivers experience. This is consistent with previous research that highlights the social isolation and lack of support often experienced by caregivers (72, 73). Interestingly, the reduction in emotional burden was less pronounced, suggesting that while caregivers may experience relief from practical or logistical aspects of caregiving, emotional support interventions may require more targeted approaches (74, 75). The categorization of caregiver burden allows for a nuanced understanding of the areas most impacted by interventions. It also highlights the need for multifaceted interventions that address not only the physical and financial aspects of caregiving but also the emotional and social dimensions. As caregivers are often under stress due to a lack of social support and emotional resources, interventions focusing on improving emotional well-being and social interactions may offer a more holistic approach to caregiver support (76, 77).

Improvements in family function were observed across four studies, with a significant positive effect (SMD = 0.53), suggesting that caregiver interventions can strengthen family dynamics and support systems. However, the effect on social support was less clear, with no statistically significant improvement (SMD = 0.55). These findings underscore the importance of targeting both individual caregivers and their broader support networks. While family function improved, social support interventions might require more intensive or sustained efforts to foster meaningful changes in caregivers’ social environments (78, 79).

The analysis also evaluated several psychological outcomes, including anxiety, stress, and depression. Statistically significant reductions in stress (SMD = −0.59) and depression (SMD = −0.45) were observed, which align with the broader literature suggesting that caregiving for patients with chronic conditions can exacerbate these mental health issues (77, 80). However, no significant reduction in anxiety was found (SMD = −0.28), which may reflect the complexity of anxiety as an emotional response and the challenge of addressing it through short-term interventions. It is possible that longer-term or more specific interventions are necessary to achieve meaningful reductions in caregiver anxiety (81). Confidence for managing stress was also improved (SMD = 0.30), which is an encouraging outcome. Increased confidence is a protective factor against caregiver burnout and may contribute to long-term well-being, enabling caregivers to handle stress more effectively (82, 83). This finding highlights the importance of equipping caregivers with the skills and strategies to manage the challenges they face.

No significant improvement in quality of life (SMD = 0.16) was found, suggesting that while interventions can alleviate caregiver burden in specific areas, they may not always lead to broad improvements in overall quality of life. It is possible that quality of life is influenced by factors beyond caregiver burden, including the severity of the patient’s condition, social and economic support, and personal coping strategies (84). Further research may explore how different types of interventions interact with these factors to affect caregivers’ overall quality of life.

Limitation

This meta-analysis provides strong evidence for the positive impact of interventions on reducing caregiver burden in chronic dyspnea caregivers, particularly in terms of emotional, physical, and social strain. However, there are some limitations that could not be ignored. In the 25 included studies, only 8 studies from Europe, and 7 from the United State of America. This may limit the generalizability of our findings to European or North-American populations. This geographical imbalance partly reflects the growing research interest in caregiver burden across Asia. Given the differences in disease epidemiology, healthcare systems, and family-centered care cultures between regions, well-designed RCTs in Europe and the Americas are warranted to confirm the external validity of the observed effects. In addition, significant variability in study quality, intervention types, and outcome measures highlights the need for more rigorous and standardized trials in this field. Future research should focus on improving the methodological quality of RCTs, particularly in terms of blinding, outcome measurement, and reporting. Additionally, more studies are needed to explore the long-term effects of caregiver interventions, particularly on anxiety and quality of life, as these factors may require more sustained and targeted approaches.

Conclusion

This meta-analysis provides compelling evidence that various interventions can significantly reduce caregiver burden in individuals caring for patients with chronic dyspnea, particularly in the areas of emotional, physical, and social strain. Significant improvements were observed in caregiver burden, family function, stress, depression, and confidence for managing stress, although no substantial changes were noted in anxiety or quality of life. The findings underscore the importance of tailored interventions that address specific dimensions of caregiver burden, especially social and emotional support, and aim to move the “caregiver-as-second-patient” concept from theory to routine practice and policy.

Data availability statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/Supplementary material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Author contributions

FL: Writing – original draft. HZ: Investigation, Data curation, Writing – review & editing. SL: Writing – review & editing. XW: Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. XL: Writing – review & editing. YL: Funding acquisition, Project administration, Resources, Writing – original draft.

Funding

The author(s) declare that financial support was received for the research and/or publication of this article. This research was funded by National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant number 71804118).

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The authors declare that no Gen AI was used in the creation of this manuscript.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Supplementary material

The Supplementary material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fpubh.2025.1659063/full#supplementary-material

Abbreviations

RCTs, Randomized Controlled Trials; SMD, Standardized mean differences; COPD, Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; GRADE, Grading of Recommendations Assessment, Development, and Evaluation; TSA, Test Sequential Analysis; RIS, Required Information Size; I2, I-squared.

References

1. Zhou, Y, Lai, H, and Xu, C. Global trends and age-period-cohort effects of chronic respiratory disease mortality attributed to industrial gaseous pollutants from 1990 to 2021. Sci Rep. (2025) 15:11924. doi: 10.1038/s41598-025-90406-4

2. Collaborators GCRD. Prevalence and attributable health burden of chronic respiratory diseases, 1990-2017: a systematic analysis for the global burden of disease study 2017. Lancet Respir Med. (2020) 8:585–96. doi: 10.1016/S2213-2600(20)30105-3

3. Cornelius, T. Clinical guideline highlights for the hospitalist: GOLD COPD update 2024. J Hosp Med. (2024) 19:818–20. doi: 10.1002/jhm.13416

4. McDonagh, TA, Metra, M, Adamo, M, Gardner, RS, Baumbach, A, Böhm, M, et al. 2023 focused update of the 2021 ESC guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of acute and chronic heart failure. Eur Heart J. (2023) 44:3627–39. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehad195

5. Levy, ML, Bacharier, LB, Bateman, E, Boulet, LP, Brightling, C, Buhl, R, et al. Key recommendations for primary care from the 2022 global initiative for asthma (GINA) update. NPJ Prim Care Respir Med. (2023) 33:7. doi: 10.1038/s41533-023-00330-1

6. Blütgen, S, Pralong, A, Wilharm, C, Eisenmann, Y, Voltz, R, and Simon, ST. BreathCarer: informal carers of patients with chronic breathlessness: a mixed-methods systematic review of burden, needs, coping, and support interventions. BMC Palliat Care. (2025) 24:33. doi: 10.1186/s12904-025-01670-0

7. Al-Gamal, E, and Yorke, J. Perceived breathlessness and psychological distress among patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and their spouses. Nurs Health Sci. (2014) 16:103–11. doi: 10.1111/nhs.12073

8. Bernabeu-Mora, R, García-Guillamón, G, Montilla-Herrador, J, Escolar-Reina, P, García-Vidal, JA, and Medina-Mirapeix, F. Rates and predictors of depression status among caregivers of patients with COPD hospitalized for acute exacerbations: a prospective study. Int J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis. (2016) 11:3199–205. doi: 10.2147/COPD.S118109

9. Jesus, LA, Malaguti, C, Evangelista, DG, Azevedo, FM, França, BP, Santos, LT, et al. Caregiver burden is associated with the physical function of individuals on long-term oxygen therapy. Respir Care. (2022) 67:1413–9. doi: 10.4187/respcare.09619

10. Schulz, R, and Sherwood, PR. Physical and mental health effects of family caregiving. Am J Nurs. (2008) 108:23–7. doi: 10.1097/01.NAJ.0000336406.45248.4c

11. Choi, JY, Lee, SH, and Yu, S. Exploring factors influencing caregiver burden: a systematic review of family caregivers of older adults with chronic illness in local communities. Healthcare (Basel). (2024) 12:1002. doi: 10.3390/healthcare12101002

12. Sisk, RJ. Caregiver burden and health promotion. Int J Nurs Stud. (2000) 37:37–43. doi: 10.1016/S0020-7489(99)00053-X

13. Vu, TT, Johnson, G, Fleary, S, Nguyen, VT, and Ngo, VK. Examining the relations between psychosocial and caregiving factors with mental health among Vietnamese family caregivers of hospitalized lung cancer patients. Sci Rep. (2025) 15:14078. doi: 10.1038/s41598-025-96409-5

14. Palacio, GC, Krikorian, A, Gómez-Romero, MJ, and Limonero, JT. Resilience in caregivers: a systematic review. Am J Hosp Palliat Care. (2020) 37:648–58. doi: 10.1177/1049909119893977

15. Li, Y, Li, J, Zhang, Y, Ding, Y, and Hu, X. The effectiveness of e-health interventions on caregiver burden, depression, and quality of life in informal caregivers of patients with cancer: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Int J Nurs Stud. (2022) 127:104179. doi: 10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2022.104179

16. Abshire Saylor, M, Clair, CA, Curriero, S, DeGroot, L, Nelson, K, Pavlovic, N, et al. Analysis of action planning, achievement and life purpose statements in an intervention to support caregivers of persons with heart failure. Heart Lung. (2023) 61:8–15. doi: 10.1016/j.hrtlng.2023.04.002

17. Bandini, JI, Kogan, AC, Olsen, B, Phillips, J, Sudore, RL, Bekelman, DB, et al. Feasibility of group visits for advance care planning among patients with heart failure and their caregivers. J Am Board Fam Med. (2021) 34:171–80. doi: 10.3122/jabfm.2021.01.200184

18. DeGroot, L, Gillette, R, Villalobos, JP, Harger, G, Doyle, DT, Bull, S, et al. Feasibility of a digital palliative care intervention (convoy-pal) for older adults with heart failure and multiple chronic conditions and their caregivers: a waitlist randomized control trial. BMC Palliat Care. (2024) 23:234. doi: 10.1186/s12904-024-01561-w

19. Eghøj, M, Zinckernagel, L, Brinks, TS, Kristensen, ALS, Hviid, SS, Tolstrup, JS, et al. Adapting an evidence-based, home cardiac rehabilitation programme for people with heart failure and their caregivers to the Danish context: DK:REACH-HF study. Eur J Cardiovasc Nurs. (2024) 23:728–36. doi: 10.1093/eurjcn/zvae037

20. Kuzu, F, and Tel Aydın, H. Effects of education on care burden and quality of life to caregivers of patients with COPD. Turk Thorac J. (2022) 23:155–22. doi: 10.5152/TurkThoracJ.2022.21002

21. McIlvennan, CK, Thompson, JS, Matlock, DD, Cleveland, JC Jr, Dunlay, SM, LaRue, SJ, et al. A multicenter trial of a shared decision support intervention for patients and their caregivers offered destination therapy for advanced heart failure: DECIDE-LVAD: rationale, design, and pilot data. J Cardiovasc Nurs. (2016) 31:E8–e20. doi: 10.1097/JCN.0000000000000343

22. Purcell, C, Purvis, A, Cleland, JGF, Cowie, A, Dalal, HM, Ibbotson, T, et al. Home-based cardiac rehabilitation for people with heart failure and their caregivers: a mixed-methods analysis of the roll out an evidence-based programme in Scotland (SCOT:REACH-HF study). Eur J Cardiovasc Nurs. (2023) 22:804–13. doi: 10.1093/eurjcn/zvad004

23. Takayama, S, Arita, R, Kikuchi, A, and Ishii, T. Bukuryoingohangekobokuto may improve recurrent aspiration pneumonia in patients with brain damage and reduce the caregiver burden. J Family Med Prim Care. (2021) 10:558–60. doi: 10.4103/jfmpc.jfmpc_1627_20

24. Dionne-Odom, JN, Ejem, DB, Wells, R, Azuero, A, Stockdill, ML, Keebler, K, et al. Effects of a telehealth early palliative care intervention for family caregivers of persons with advanced heart failure: the ENABLE CHF-PC randomized clinical trial. JAMA Netw Open. (2020) 3:e202583. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2020.2583

25. Ng, AYM, and Wong, FKY. Effects of a home-based palliative heart failure program on quality of life, symptom burden, satisfaction and caregiver burden: a randomized controlled trial. J Pain Symptom Manag. (2018) 55:1–11. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2017.07.047

26. Santos, GC, Liljeroos, M, Tschann, K, Denhaerynck, K, Wicht, J, Jurgens, CY, et al. Feasibility, acceptability, and outcome responsiveness of the SYMPERHEART intervention to support symptom perception in persons with heart failure and their informal caregivers: a feasibility quasi-experimental study. Pilot Feasibility Stud. (2023) 9:168. doi: 10.1186/s40814-023-01390-3

27. Timonet-Andreu, E, Morales-Asencio, JM, Alcalá Gutierrez, P, Cruzado Alvarez, C, López-Moyano, G, Mora Banderas, A, et al. Health-related quality of life and use of hospital services by patients with heart failure and their family caregivers: a multicenter case-control study. J Nurs Scholarsh. (2020) 52:217–28. doi: 10.1111/jnu.12545

28. Villalobos, JP, Bull, SS, and Portz, JD. Usability and acceptability of a palliative care Mobile intervention for older adults with heart failure and caregivers: observational study. JMIR Aging. (2022) 5:e35592. doi: 10.2196/35592

29. Barsuk, JH, Wilcox, JE, Cohen, ER, Harap, RS, Shanklin, KB, Grady, KL, et al. Simulation-based mastery learning improves patient and caregiver ventricular assist device self-care skills: a randomized pilot trial. Circ Cardiovasc Qual Outcomes. (2019) 12:e005794. doi: 10.1161/CIRCOUTCOMES.119.005794

30. Campbell, ML, and McErlane, L. Feasibility of a study to test the effectiveness of a dyspnea assessment and treatment bundle to improve family caregiving of patients in home hospice. J Palliat Med. (2018) 21:1547. doi: 10.1089/jpm.2018.0409

31. Ferreira, D, Kochovska, S, Honson, A, Phillips, J, and Currow, D. Patients' and their caregivers' experiences with regular, low-dose, sustained-release morphine for chronic breathlessness associated with COPD: a qualitative study. BMJ Open Respir Res. (2022) 9. doi: 10.1136/bmjresp-2022-001210

32. Ferreira, DH, Boland, JW, Kochovska, S, Honson, A, Phillips, JL, and Currow, DC. Patients' and caregivers' experiences of driving with chronic breathlessness before and after regular low-dose sustained-release morphine: a qualitative study. Palliat Med. (2020) 34:1078–87. doi: 10.1177/0269216320929549

33. Locatelli, G, Zeffiro, V, Occhino, G, Rebora, P, Caggianelli, G, Ausili, D, et al. Effectiveness of motivational interviewing on contribution to self-care, self-efficacy, and preparedness in caregivers of patients with heart failure: a secondary outcome analysis of the MOTIVATE-HF randomized controlled trial. Eur J Cardiovasc Nurs. (2022) 21:801–11. doi: 10.1093/eurjcn/zvac013

34. Moody, LE, Webb, M, Cheung, R, and Lowell, J. A focus group for caregivers of hospice patients with severe dyspnea. Am J Hosp Palliat Care. (2004) 21:121–30. doi: 10.1177/104990910402100210

35. Najafi, E, Rafiei, H, Rashvand, F, and Pazoki, A. The effects of teach-Back and blended training on self-care and care burden among caregivers of patients with heart failure caregivers. Home Healthc Now. (2024) 42:354–63. doi: 10.1097/NHH.0000000000001305

36. Piette, JD, Striplin, D, Fisher, L, Aikens, JE, Lee, A, Marinec, N, et al. Effects of accessible health technology and caregiver support Posthospitalization on 30-day readmission risk: a randomized trial. Jt Comm J Qual Patient Saf. (2020) 46:109–17. doi: 10.1016/j.jcjq.2019.10.009

37. Piette, JD, Striplin, D, Marinec, N, Chen, J, Trivedi, RB, Aron, DC, et al. A Mobile health intervention supporting heart failure patients and their informal caregivers: a randomized comparative effectiveness trial. J Med Internet Res. (2015) 17:e142. doi: 10.2196/jmir.4550

38. Yang, W, Sun, L, Hao, L, Zhang, X, Lv, Q, Xu, X, et al. Effects of the family customised online FOCUS programme on patients with heart failure and their informal caregivers: a multicentre, single-blind, randomised clinical trial. eClinicalMedicine. (2024) 69:102481. doi: 10.1016/j.eclinm.2024.102481

39. Oliver, TL, Hetland, B, Schmaderer, M, Zolty, R, and Pozehl, B. A feasibility study of qualitative methods using the Zarit burden interview in heart failure caregivers. Appl Nurs Res. (2024) 79:151826. doi: 10.1016/j.apnr.2024.151826

40. Piette, JD, Striplin, D, Marinec, N, Chen, J, and Aikens, JE. A randomized trial of mobile health support for heart failure patients and their informal caregivers: impacts on caregiver-reported outcomes. Med Care. (2015) 53:692–9. doi: 10.1097/MLR.0000000000000378

41. Pucciarelli, G, Occhino, G, Locatelli, G, Baricchi, M, Ausili, D, Rebora, P, et al. The effectiveness of a motivational interviewing intervention on mutuality between patients with heart failure and their caregivers: a secondary outcome analysis of the MOTIVATE-HF randomized controlled trial. J Cardiovasc Nurs. (2024) 39:107–17. doi: 10.1097/JCN.0000000000000991

42. van Harlingen, AOW, van de Ven, LG, Hasselaar, J, Thalen, J, Jukema, J, Vissers, K, et al. Developing a toolkit for patients with COPD or chronic heart failure and their informal caregivers to improve person-centredness in conversations with healthcare professionals: a design thinking approach. Patient Educ Couns. (2022) 105:3324–30. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2022.07.002

43. Vellone, E, Chung, ML, Cocchieri, A, Rocco, G, Alvaro, R, and Riegel, B. Effects of self-care on quality of life in adults with heart failure and their spousal caregivers: testing dyadic dynamics using the actor-partner interdependence model. J Fam Nurs. (2014) 20:120–41. doi: 10.1177/1074840713510205

44. Abshire Saylor, M, Pavlovic, N, DeGroot, L, Peeler, A, Nelson, KE, Perrin, N, et al. Feasibility of a multi-component strengths-building intervention for caregivers of persons with heart failure. J Appl Gerontol. (2023) 42:2371–82. doi: 10.1177/07334648231191595

45. Ågren, S, Strömberg, A, Jaarsma, T, and Luttik, ML. Caregiving tasks and caregiver burden; effects of an psycho-educational intervention in partners of patients with post-operative heart failure. Heart Lung. (2015) 44:270–5. doi: 10.1016/j.hrtlng.2015.04.003

46. Alaei, A, Babaei, S, Farzi, S, and Hadian, Z. Effect of a supportive-educational program, based on COPE model, on quality of life and caregiver burden of family caregivers of heart failure patients: a randomized clinical trial study. BMC Nurs. (2024) 23:72. doi: 10.1186/s12912-024-01709-2

47. Barutcu, CD, and Mert, H. Effect of support group intervention applied to the caregivers of individuals with heart failure on caregiver outcomes. Holist Nurs Pract. (2016) 30:272–82. doi: 10.1097/HNP.0000000000000164

48. Chiang, LC, Chen, WC, Dai, YT, and Ho, YL. The effectiveness of telehealth care on caregiver burden, mastery of stress, and family function among family caregivers of heart failure patients: a quasi-experimental study. Int J Nurs Stud. (2012) 49:1230–42. doi: 10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2012.04.013

49. Clements, L, Frazier, SK, Lennie, TA, Chung, ML, and Moser, DK. Improvement in heart failure self-care and patient readmissions with caregiver education: a randomized controlled trial. West J Nurs Res. (2023) 45:402–15. doi: 10.1177/01939459221141296

50. Doyon, K, Flint, K, Albright, K, and Bekelman, D. Improving benefit and reducing burden of informal caregiving for patients with heart failure: a mixed methods study. J Cardiovasc Nurs. (2024) 40:406–12. doi: 10.1097/JCN.0000000000001137

51. Etemadifar, S, Bahrami, M, Shahriari, M, and Farsani, AK. The effectiveness of a supportive educative group intervention on family caregiver burden of patients with heart failure. Iran J Nurs Midwifery Res. (2014) 19:217–23.

52. Gary, R, Dunbar, SB, Higgins, M, Butts, B, Corwin, E, Hepburn, K, et al. An intervention to improve physical function and caregiver perceptions in family caregivers of persons with heart failure. J Appl Gerontol. (2020) 39:181–91. doi: 10.1177/0733464817746757

53. Hu, X, Dolansky, MA, Su, Y, Hu, X, Qu, M, and Zhou, L. Effect of a multidisciplinary supportive program for family caregivers of patients with heart failure on caregiver burden, quality of life, and depression: a randomized controlled study. Int J Nurs Stud. (2016) 62:11–21. doi: 10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2016.07.006

54. Hwang, B, Granger, DA, Brecht, ML, and Doering, LV. Cognitive behavioral therapy versus general health education for family caregivers of individuals with heart failure: a pilot randomized controlled trial. BMC Geriatr. (2022) 22:281. doi: 10.1186/s12877-022-02996-7

55. Khaninezhad, L, Valiee, S, Moradi, Y, and Mahmoudi, M. The effect of a caring program based on the Pender's health promotion model on caregiver burden in family caregivers of patients with chronic heart failure: a quasi-experimental study. J Educ Health Promot. (2024) 13:303. doi: 10.4103/jehp.jehp_1024_23

56. Lang, CC, Smith, K, Wingham, J, Eyre, V, Greaves, CJ, Warren, FC, et al. A randomised controlled trial of a facilitated home-based rehabilitation intervention in patients with heart failure with preserved ejection fraction and their caregivers: the REACH-HFpEF pilot study. BMJ Open. (2018) 8:e019649. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2017-019649

57. Liljeroos, M, Ågren, S, Jaarsma, T, Årestedt, K, and Strömberg, A. Long-term effects of a dyadic psycho-educational intervention on caregiver burden and morbidity in partners of patients with heart failure: a randomized controlled trial. Qual Life Res. (2017) 26:367–79. doi: 10.1007/s11136-016-1400-9

58. Locatelli, G, Rebora, P, Occhino, G, Ausili, D, Riegel, B, Cammarano, A, et al. The impact of an intervention to improve caregiver contribution to heart failure self-care on caregiver anxiety, depression, quality of life, and sleep. J Cardiovasc Nurs. (2023) 38:361–9. doi: 10.1097/JCN.0000000000000998

59. Marzban, A, Akbari, M, Moradi, M, and Fanian, N. The effect of emotional freedom techniques (EFT) on anxiety and caregiver burden of family caregivers of patients with heart failure: a quasi-experimental study. J Educ Health Promot. (2024) 13:128. doi: 10.4103/jehp.jehp_609_23

60. Molloy, GJ, Johnston, DW, Gao, C, Witham, MD, Gray, JM, Argo, IS, et al. Effects of an exercise intervention for older heart failure patients on caregiver burden and emotional distress. Eur J Cardiovasc Prev Rehabil. (2006) 13:381–7. doi: 10.1097/01.hjr.0000198916.60363.85

61. Namjoo, M, Nematollahi, M, Taebi, M, Kahnooji, M, and Mehdipour-Rabori, R. The efficacy of telenursing on caregiver burden among Iranian patients with heart failure: a randomized clinical trial. ARYA Atheroscler. (2021) 17:1–6. doi: 10.22122/arya.v17i0.2102

62. Piamjariyakul, U, Smothers, A, Wang, K, Shafique, S, Wen, S, Petitte, T, et al. Palliative care for patients with heart failure and family caregivers in rural Appalachia: a randomized controlled trial. BMC Palliat Care. (2024) 23:199. doi: 10.1186/s12904-024-01531-2

63. Piamjariyakul, U, Werkowitch, M, Wick, J, Russell, C, Vacek, JL, and Smith, CE. Caregiver coaching program effect: reducing heart failure patient rehospitalizations and improving caregiver outcomes among African Americans. Heart Lung. (2015) 44:466–73. doi: 10.1016/j.hrtlng.2015.07.007

64. Riegel, B, Quinn, R, Hirschman, KB, Thomas, G, Ashare, R, Stawnychy, MA, et al. Health coaching improves outcomes of informal caregivers of adults with chronic heart failure: a randomized controlled trial. Circ Heart Fail. (2024) 17:e011475. doi: 10.1161/CIRCHEARTFAILURE.123.011475

65. Şanlıtürk, D, and Ayaz-Alkaya, S. The effect of a nurse-led home visit program on the care burden of caregivers of adults with asthma: a randomized controlled trial. Public Health Nurs. (2023) 40:895–902. doi: 10.1111/phn.13247

66. Thodi, M, Bistola, V, Lambrinou, E, Keramida, K, Nikolopoulos, P, Parissis, J, et al. A randomized trial of a nurse-led educational intervention in patients with heart failure and their caregivers: impact on caregiver outcomes. Eur J Cardiovasc Nurs. (2023) 22:709–18. doi: 10.1093/eurjcn/zvac118

67. Vagharseyyedin, SA, Arbabi, M, Rahimi, H, and Moghaddam, SGM. Effects of a caregiver educational program on interactions between family caregivers and patients with advanced COPD. Home Healthc Now. (2022) 40:75–81. doi: 10.1097/NHH.0000000000001049

68. Yang, W, Zhang, X, Li, Y, Lv, Q, Gao, X, Lin, M, et al. Advanced heart failure patients and family caregivers health and function: randomised controlled pilot trial of online dignity therapy. BMJ Support Palliat Care. (2023) doi: 10.1136/spcare-2022-003945

69. Tran, JT, Theng, B, Tzeng, HM, Raji, M, Serag, H, Shih, M, et al. Cultural diversity impacts caregiving experiences: a comprehensive exploration of differences in caregiver burdens, needs, and outcomes. Cureus. (2023) 15:e46537. doi: 10.7759/cureus.46537

70. Cho, J, Nakagawa, T, Martin, P, Gondo, Y, Poon, LW, and Hirose, N. Caregiving centenarians: cross-national comparison in caregiver-burden between the United States and Japan. Aging Ment Health. (2020) 24:774–83. doi: 10.1080/13607863.2018.1544221

71. Ng, R, and Indran, N. Societal perceptions of caregivers linked to culture across 20 countries: evidence from a 10-billion-word database. PLoS One. (2021) 16:e0251161. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0251161

72. Nemcikova, M, Katreniakova, Z, and Nagyova, I. Social support, positive caregiving experience, and caregiver burden in informal caregivers of older adults with dementia. Front Public Health. (2023) 11:1104250. doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2023.1104250

73. Bongelli, R, Busilacchi, G, Pacifico, A, Fabiani, M, Guarascio, C, Sofritti, F, et al. Caregiving burden, social support, and psychological well-being among family caregivers of older Italians: a cross-sectional study. Front Public Health. (2024) 12:1474967. doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2024.1474967

74. Panzeri, A, Bottesi, G, Ghisi, M, Scalavicci, C, Spoto, A, and Vidotto, G. Emotional regulation, coping, and resilience in informal caregivers: a network analysis approach. Behav Sci (Basel). (2024) 14:709. doi: 10.3390/bs14080709

75. Cui, P, Yang, M, Hu, H, Cheng, C, Chen, X, Shi, J, et al. The impact of caregiver burden on quality of life in family caregivers of patients with advanced cancer: a moderated mediation analysis of the role of psychological distress and family resilience. BMC Public Health. (2024) 24:817. doi: 10.1186/s12889-024-18321-3

76. Taher, M, Azizi, N, Rohani, M, Koukamari, PH, Rashidi, F, Araban, M, et al. Exploring the role of perceived social support, and spiritual well-being in predicting the family caregiving burden among the parents of disabled children. BMC Public Health. (2025) 25:567. doi: 10.1186/s12889-025-21654-2

77. Yu, Q, Xu, L, Zhou, L, Jiang, X, Xu, N, Lang, Z, et al. A study of the relationship between social support, caregiving experience and depressed mood of family caregivers of home-dwelling older adults with disability – a cross-sectional study. BMC Public Health. (2025) 25:1021. doi: 10.1186/s12889-025-22276-4

78. Song, JY, Liu, M, Zhang, M, Sulaiman, Z, Ismail, TAT, Li, SM, et al. Comparative effectiveness of psychosocial interventions on family function and resilience for Cancer caregivers: a systematic review with pairwise and network Meta-analysis. Cancer Nurs. (2025). doi: 10.1097/NCC.0000000000001476

79. Wallace, PM, and Sterns, HL. Considerations of family functioning and clinical interventions. Gerontol Geriatr Med. (2022) 8:23337214221119054. doi: 10.1177/23337214221119054

80. Rahimi, F, Shakibazadeh, E, Ashoorkhani, M, Hosseini, H, Foroughan, M, Aghayani, Z, et al. Effect of a web-based intervention on the mental health of informal caregivers of the elderly: a randomized controlled trial. BMC Psychiatry. (2025) 25:404. doi: 10.1186/s12888-025-06819-y

81. Hou, RJ, Wong, SY, Yip, BH, Hung, AT, Lo, HH, Chan, PH, et al. The effects of mindfulness-based stress reduction program on the mental health of family caregivers: a randomized controlled trial. Psychother Psychosom. (2014) 83:45–53. doi: 10.1159/000353278

82. Alborzkouh, P, Nabati, M, Zainali, M, Abed, Y, and Shahgholy Ghahfarokhi, F. A review of the effectiveness of stress management skills training on academic vitality and psychological well-being of college students. J Med Life. (2015) 8:39–44. doi: 10.15171/jml.2015.109

83. Sahranavard, S, Esmaeili, A, Dastjerdi, R, and Salehiniya, H. The effectiveness of stress-management-based cognitive-behavioral treatments on anxiety sensitivity, positive and negative affect and hope. Biomedicine (Taipei). (2018) 8:23. doi: 10.1051/bmdcn/2018080423

Keywords: caregiver burden, chronic respiratory diseases, heart failure, COPD, asthma, interventions, meta-analysis

Citation: Liu F, Zhang H, Li S, Wang X, Long X and Liu Y (2025) Interventions for reducing caregiver burden in chronic dyspnea: a meta-analysis. Front. Public Health. 13:1659063. doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2025.1659063

Edited by:

Margarida Vilaça, University of Minho, PortugalReviewed by:

Claudia Andrea Ramirez Perdomo, South Colombian University, ColombiaGiovanna Casella, University Hospital of Parma, Italy

Copyright © 2025 Liu, Zhang, Li, Wang, Long and Liu. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Yang Liu, bGl1eWFuZ0B3Y2hzY3UuY24=

†These authors have contributed equally to this work

Fang Liu

Fang Liu Han Zhang†

Han Zhang† Shihan Li

Shihan Li Xianshan Wang

Xianshan Wang Xiaoqing Long

Xiaoqing Long