- 1Department of Anesthesiology, West China Hospital of Sichuan University, Chengdu, Sichuan, China

- 2Department of Anesthesiology, West China Tianfu Hospital, Sichuan University, Chengdu, Sichuan, China

- 3Operating Room Department, West China Tianfu Hospital, Sichuan University, Chengdu, Sichuan, China

Objective: By conducting a meta-synthesis of qualitative research, this study evaluates the real experiences and care needs of frail older patients, providing valuable references and insights for care service providers, policymakers, and medical researchers in developing intervention programs.

Design: PubMed, Web of Science, Scopus, Embase, CINAHL, and PsycINFO were searched from the establishment of the databases to August 25, 2024.

Setting: The real experiences and care needs of frail older patients are gradually becoming the focus of social attention. Qualitative research is of great significance for improving the quality of care services for such patients in the future.

Outcome measures: The quality of the studies included was appraised using the Joanna Briggs Institute Quality Assessment of Qualitative Research criteria. Data extraction was performed using NVivo (v14), and results were synthesized using a meta-synthesis approach.

Results: 511 frail older patients were included in 15 studies. Three main themes were identified: the negative impact of frailty on the physical, psychological, and behavioral aspects of older patients; positive attitudes toward the current situation among frail older patients; and the multidimensional care needs of frail older patients.

Conclusion: Frail older adults face multidimensional challenges in physiology, psychology, and behavior, and have care needs in areas such as professional services and social support.

Systematic review registration: https://www.crd.york.ac.uk/PROSPERO/view/CRD420251038626.

1 Introduction

Frailty is a complex clinical condition associated with aging and caused by multiple factors. Frailty is defined as the deterioration of bodily functions and age-related loss of reserve capacity, leading to a reduced ability to cope with internal and external stressors (1, 2). In recent years, with the rapid growth of the aging population, the prevalence of frailty among older individuals has increased significantly. A survey study on the time trend of frailty prevalence among middle-aged and older people in China from 2011 to 2020 showed that the standardized prevalence increased from 13.5% in 2011 to 16.3% in 2020 (3). The prevalence rates of frailty and pre-frailty among old inpatients in low- and middle-income countries reached 39.1 and 51.4%, respectively (4). The high prevalence of frailty exacerbates adverse outcomes among the old population and reduces their quality of life, posing new challenges to global healthcare resources and socioeconomic development. Therefore, we urgently need to address the issue of frailty among such populations to achieve the long-term goal of maintaining their ability to care for themselves.

Frailty is generally considered to be reversible (5) Early identification and intervention can help patients regain their ability to care for themselves and avoid adverse events such as disability, depression, falls, dementia, and even death (6–8). Currently, non-pharmacological interventions are the primary approach for treating and managing frailty (9), including multi-component interventions and nutritional interventions (10, 11). However, most studies have focused solely on quantitative outcomes related to frailty. The research methods used in randomized controlled trials (RCTs) fail to accurately reflect the real-life experiences and care needs of frail older patients, overlooking the varying degrees of harm caused by the disease and the actual care needs of older patients at all stages of the frailty process. Increased frailty often portends social isolation and loneliness for older patients in the future (12). At the same time, there will be an increased demand for care provided by families, community groups, nursing homes, and hospitals. Providing practical assistance in advance can help frail older patients actively address these issues and reduce their negative emotions.

Compared with meta-analyses that routinely include quantitative studies, meta-synthesis of qualitative studies may enrich our understanding of complex, multifaceted health experiences and healthcare practice environments, increase the depth of understanding of results, and improve the openness and transparency of results (13). Therefore, this study aims to conduct a comprehensive review of qualitative research on frailty in older adults using a meta-synthesis approach to assess the real experiences and care needs of frail older adults. It provides valuable references and insights for care providers, policymakers, and medical researchers in developing intervention programs.

2 Methods

This meta-synthesis of systematic reviews and qualitative studies was reported under the statement “Enhancing transparency in reporting the synthesis of qualitative research” (14, 15). The study protocol was registered in PROSPERO (CRD420251038626).

2.1 Literature search

Computerized searches were conducted in the English-language databases PubMed, Web of Science, Scopus, Embase, CINAHL, and PsycINFO, with search dates ranging from the establishment of each database to August 25, 2024. The English retrieval terms included Qualitative Research, qualitative study, Grounded theory, interview, phenomenology, content analysis, case analysis, action research, ethnography, aged, the aged, senior citizen, old people, older, elder, agedness, senium, old age, person of advanced age, geriatric, and frailty. Using PubMed as an example, the search strategy is manifested in Appendix 1.

2.2 Eligibility criteria

The inclusion and exclusion criteria were determined based on the PICoS principle recommended by the Joanna Briggs Institute (JBI) Library of Evidence-Based Medicine in Australia.

Inclusion criteria: (1) study population (P): old individuals diagnosed with frailty, aged ≥60 years; (2) phenomenon of interest (I): real experiences, feelings, attitudes, and care needs of frail older patients; (3) context (Co): home, community, and related care institutions; (4) study design (S): qualitative research, including phenomenology, grounded theory, ethnography, and descriptive qualitative research.

Exclusion criteria: (1) literature for which the full text cannot be obtained or data were incomplete; (2) duplicate publications; (3) non-English literature; (4) research subjects in the terminal stage of life, suffering from major injuries, or with severe cognitive impairment; (5) studies with a quality rating of Grade C. Detailed eligibility criteria are outlined in Supplementary Table S1.

2.3 Literature screening and data extraction

Endnote 21 was used to remove duplicates. Full-text articles that met the inclusion criteria were retrieved, screened, and retained for review. Two researchers independently screened the literature, extracted data, and cross-checked each other’s work. In case of disagreement, they discussed or negotiated with a third researcher to resolve the issue. Data extraction included the first author, publication year, country, research method, research subjects, phenomena of interest, contextual factors, and main results.

2.4 Quality appraisal

Two researchers independently conducted a methodological quality assessment using the criteria developed by JBI Centre for Evidence-Based Healthcare Quality Evaluation Criteria for qualitative research (16). The assessment consisted of 10 items, each of which was evaluated as “yes,” “no,” or “unclear.” Based on the evaluation results, study quality was categorized into three grades: A, B, and C, corresponding to meeting all evaluation criteria, partially meeting evaluation criteria, and not meeting evaluation criteria, respectively. In case of disagreement, they discussed or negotiated with the third researcher.

2.5 Data analysis and meta-synthesis

Thomas and Harden’s three-stage thematic synthesis method was employed to summarize and integrate the included literature (17), following the systematic iterative process outlined in the JBI meta-aggregation guidelines (13). NVivo 14 software was used to assist in data extraction and narrative analysis, mainly including the following steps: (1) coding of the initial data: two researchers independently performed line-by-line coding of all included studies; (2) grouping into sub-themes: the codes were organized into descriptive themes; (3) refinement of categories: similar findings were consolidated into analytical themes; and (4) validation and consistency checking: the entire research team iteratively reviewed and discussed the resulting themes until a consensus was reached regarding interpretive sufficiency and adequacy.

2.6 Reflexivity

In qualitative research, the personal experiences, academic backgrounds, and methods of data collection and interpretation of the research team members are important in the research process. Therefore, transparent clarification of our position and the measures taken to manage potential biases is essential to ensure methodological rigor. PS, WXY, and KJP are clinical senior nurses with extensive experience in caring for older patients and have previously participated in qualitative research. HHZ is a graduate researcher with experience as a psychologist’s assistant. LX and TYQ are senior researchers—a nurse-in-charge and an associate chief nurse, respectively—with substantial expertise in conducting qualitative studies and systematic reviews. Together, the team brought diverse perspectives and experiences to the synthesis process and overall investigation. A critical realism view was taken when dealing with the data. Regular meetings were held to critically discuss and challenge each other’s coding decisions and emerging thematic structures. This process helped uncover and mitigate individual biases, identify key similarities/themes within the dataset (while accounting for contradictory findings), and ultimately helps us to explore this dual reality.

3 Results

3.1 Screening results

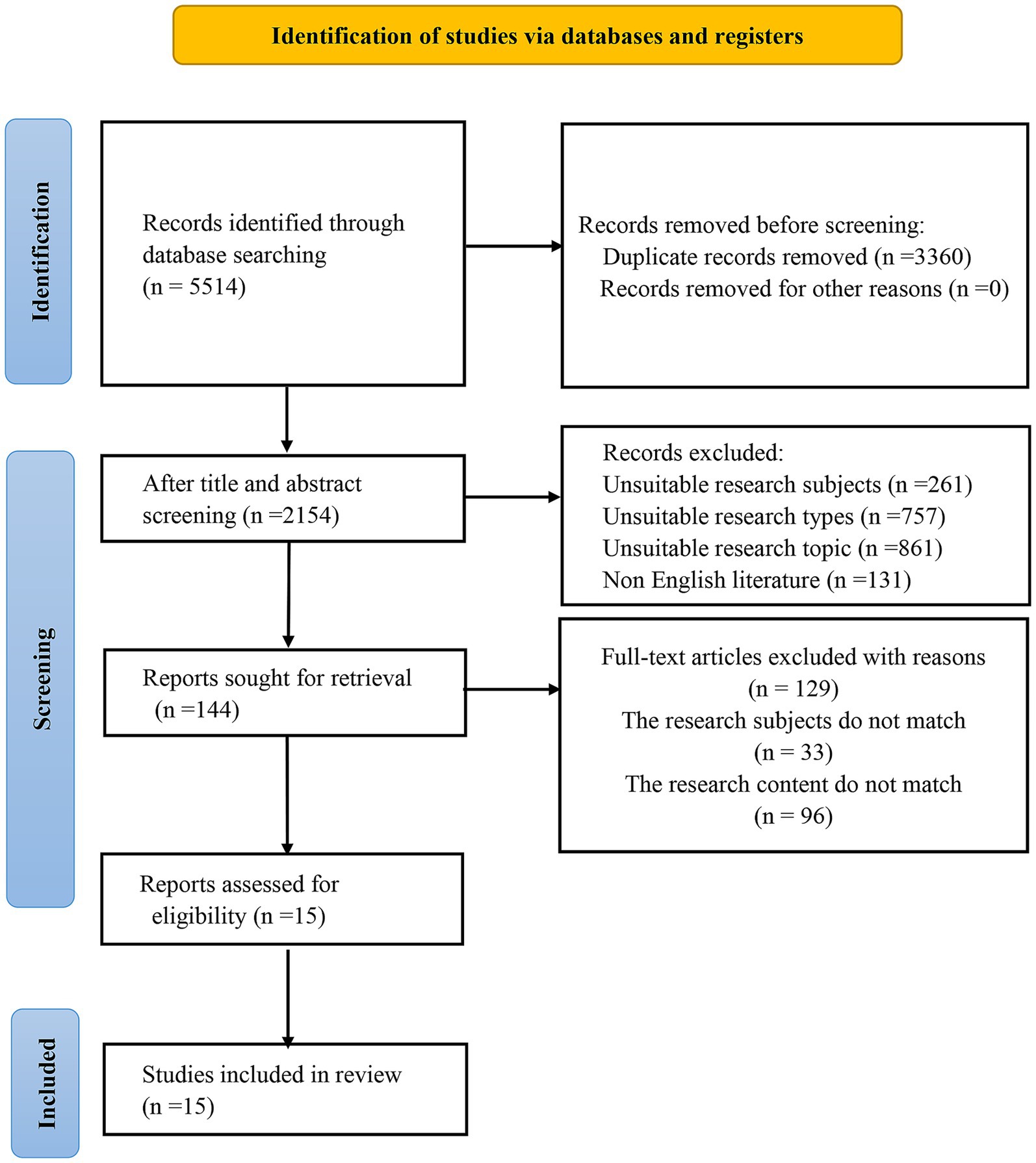

5,514 documents were retrieved, and 3,360 duplicate documents were excluded. After reading the titles and abstracts of 2,154 documents, 2,010 documents were excluded. After reading the full text of 144 documents, 129 documents were excluded because the research subjects or content did not meet the criteria. Finally, 15 documents were included. The screening process is manifested in Figure 1.

3.2 Basic information

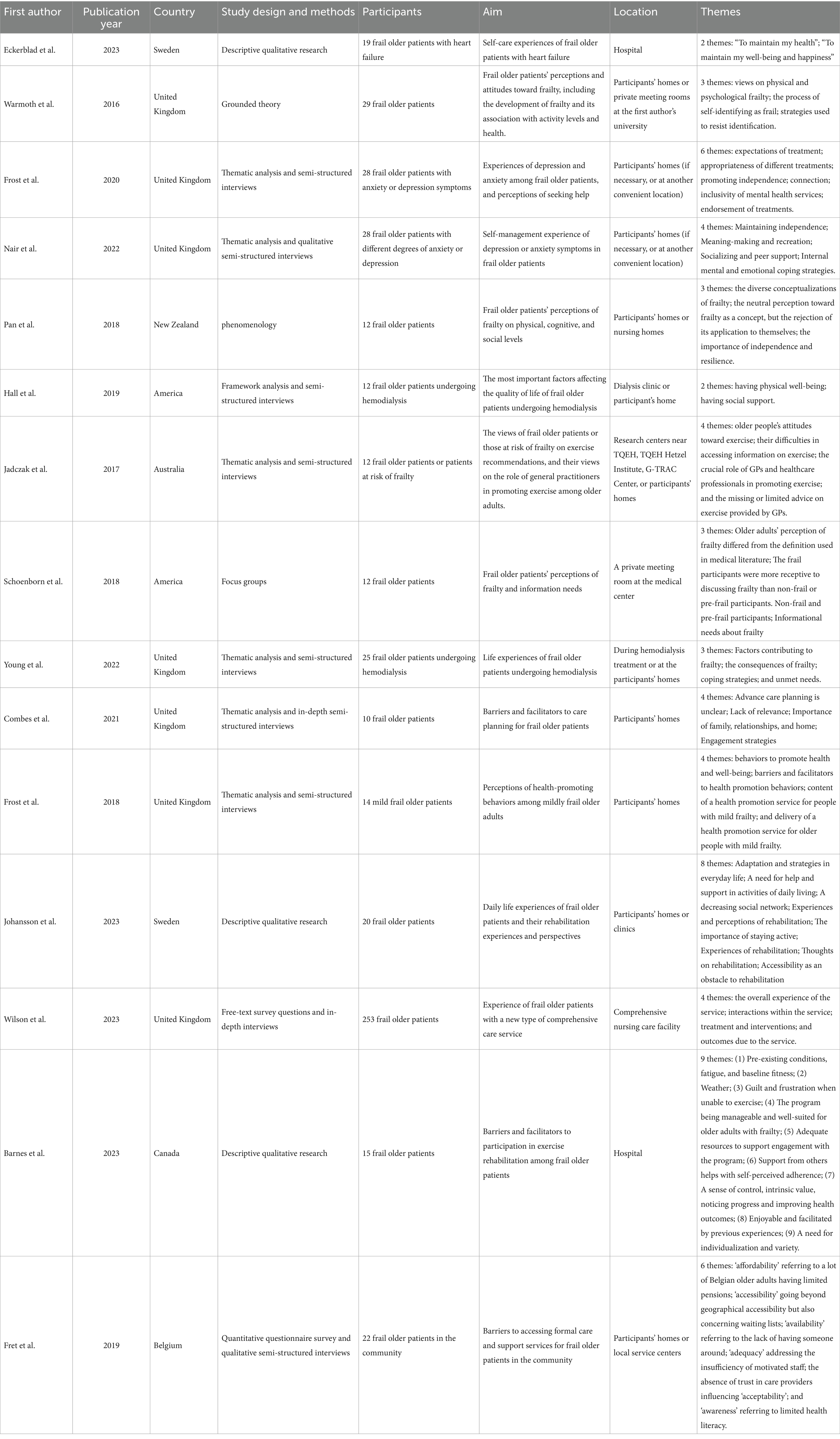

15 studies involving 511 frail older patients were included. The studies were published between 2016 and 2023. Seven studies were conducted in the United Kingdom (18–24), two in the United States (25, 26), two in Switzerland (27, 28), one in New Zealand (29), one in Canada (30), one in Belgium (31), and one in Australia (32). Three studies employed descriptive research designs and methods (27, 28, 33), five used thematic analysis and semi-structured interviews (19–21, 24, 32), one combined thematic analysis with in-depth semi-structured interviews (18), one utilized a mixed-methods approach (31), one incorporated open-ended survey questions and in-depth interviews (23), one employed focus groups (26), one applied grounded theory (22), one adopted a phenomenological research approach (29), and one utilized framework analysis combined with semi-structured interviews (25). The details are listed in Table 1.

3.3 Study quality

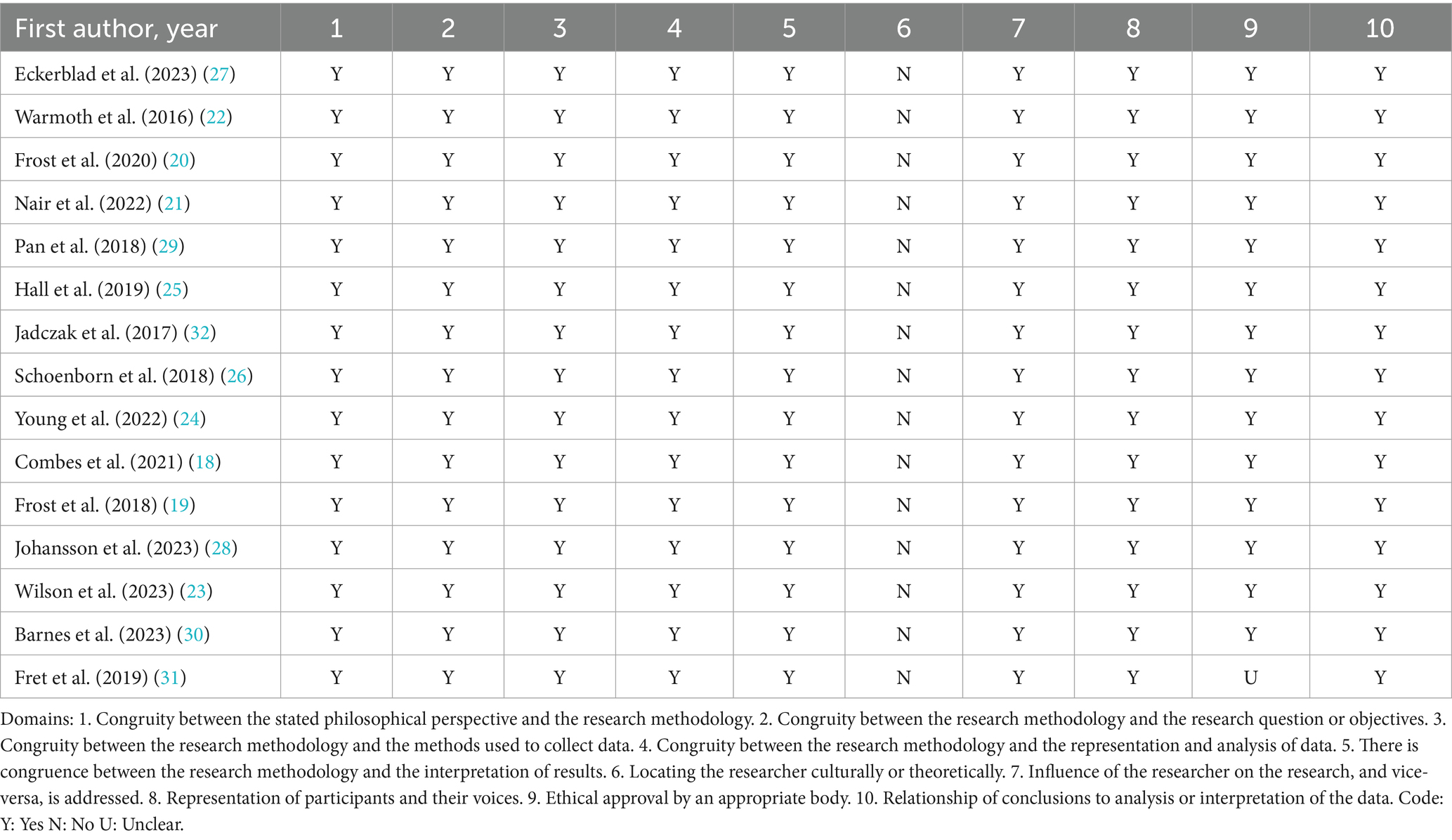

All studies reported consistency between philosophical foundations and methodology; consistency between methodology and research questions or objectives; consistency between methodology and data collection methods; consistency between methodology and research subjects, data analysis methods; and consistency between methodology and result interpretation methods. None of the studies explained the researchers’ circumstances from the perspective of cultural background or values. All studies described the influence of the researchers on the research and the influence of the research on the researchers. The research subjects were typical and fully reflected the research subjects and their views. Only one study was unclear as to whether it complied with current ethical standards, while the remaining 14 studies were compliant. The conclusions drawn were based on the analysis and interpretation of the data. The methodological quality of the 15 studies included was rated as Grade B. The details are listed in Table 2.

3.4 Meta-synthesis of qualitative studies

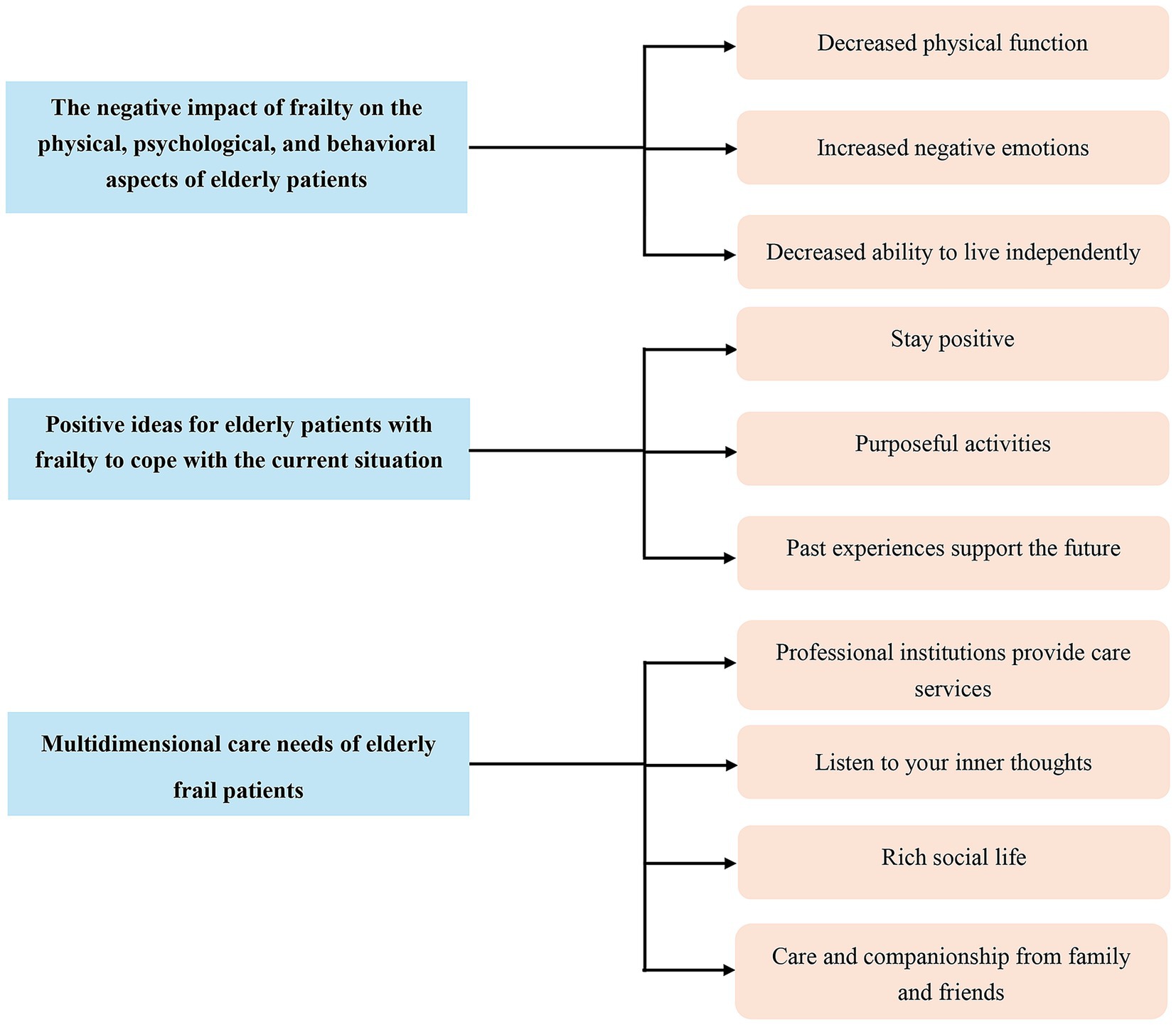

Through repeated reading, analyses, and comparisons of original data, the research results were summarized into 12 categories and 3 themes. An overview of the themes is manifested in Figure 2.

3.4.1 Theme 1: negative effects of frailty on the physical, psychological, and behavioral aspects of older patients

3.4.1.1 Category 1: decline in physical function

Over time, frailty causes older patients to move more slowly, reduces their sensitivity to bodily sensations, and undermines the function of their sensory organs (24). Severe frailty in older adults can even manifest as recognizable clinical symptoms (22). More specific symptoms of frailty include cognitive decline, frequent fatigue, significantly increased pain, and mental exhaustion due to poor sleep quality (24, 29).

3.4.1.2 Category 2: increased negative emotions

For frail older patients, the days ahead may be destined to become even more challenging (27). Some older patients even develop severe negative and pessimistic emotions (22, 24), and others’ perceptions exacerbate the stigma associated with frailty (22). They do not want to be a burden to their families (18, 24), and positive recommendations are also ignored (26). When a family member or friend suddenly passes away (29), or a doctor or other person informs them that they are experiencing frailty (26), the psychological stress caused by these events can exacerbate frailty in older patients, creating a vicious cycle. Frailty can also reduce older patients’ expectations for treatment outcomes, leading to anxiety (20).

3.4.1.3 Decline in independent living abilities

The coexistence of frailty and aging makes it difficult for older patients to cope with the challenges of daily life (18). They begin to rely on tools and adopt simpler methods to deal with the problems they encounter in their daily lives (29).

3.4.2 Theme 2: positive thoughts of frail older patients in coping with their current situations

3.4.2.1 Category 1: maintaining a positive mindset

Frail older adults remain hopeful about their future lives, and an optimistic and positive mindset is an effective way to cope with frailty (18). In addition to their thoughts, the stimulus of people around them gives them the motivation to cope with frailty (22).

3.4.2.2 Category 2: purposeful activities

Attempting to engage in and complete a new task can enhance their sense of self-identity and accomplishment. To overcome their current state of frailty, older patients need to learn to adjust and control their previous lifestyle habits and engage in more purposeful activities (19), such as exercise, paying attention to diet, social activities, improving mood and memory, and creating occupational activities (such as daily shopping).

3.4.2.3 Category 3: support from past experiences

Traumatic events experienced in the past can provide frail older patients with the courage and strength to face the future. With unwavering willpower, they can confront their frail conditions (21).

3.4.3 Theme 3: multidimensional care needs of frail older patients

3.4.3.1 Category 1: need for professional institutions to provide care services

Frail older patients often suffer from multiple coexisting conditions, which makes them more dependent on professional medical institutions than other populations to provide medication guidance and disease management and monitoring on behalf of their families. Self-management of their health status is no longer feasible in reality (31).

In addition, to maintain basic bodily functions, frail older patients attempt to alleviate the progression of frailty through exercise, but they require official channels or clear pathways (such as videos or written records) to obtain exercise guidance (30, 32).

3.4.3.2 Category 2: need for caregivers to listen to their inner thoughts

Different life experiences and social circumstances mean that they need caregivers to provide different types of psychological support, listening to their true feelings to offer emotional support (20). Effective communication can improve the quality of care and dispel their doubts about care plans (23).

3.4.3.3 Category 3: need for care institutions to provide a rich social life

Frail older patients tend to lead relatively monotonous lives in their later years, so it is important to involve them in interesting social activities (19, 27). This can be achieved by setting up more spaces or venues for informal gatherings, where more people can participate and share interesting things about their lives and the challenges they face (21).

They want to participate in enriching and quiet activities such as reading newspapers, crossword puzzles, Sudoku, jigsaw puzzles, or needlework to ensure that they become better and more energetic. They want to leverage the power of the group to help them train better and restore their health (28).

3.4.3.4 Category 4: need for care and companionship from family and friends

The company of family and friends is especially important for frail older patients. They are not only family members but also companions who accompany them in everything they do (19, 30). Having familiar family members or friends by their side makes patients feel warm and no longer lonely. Such moments are especially precious to them (18, 25).

4 Discussion

The integrated results show that frail older patients experience a decline in perception, cognition, and mobility, often accompanied by clinical symptoms such as fatigue, pain, and poor sleep quality. In addition to physical distress, they also experience corresponding negative emotions such as anxiety, psychological stress, burden, and shame, with severe cases leading to pessimistic emotions. Their ability to cope with problems in daily life declines. The above are the negative experiences of frail older patients in terms of their physical, psychological, and behavioral aspects. Of course, some optimistic frail older patients actively cope with these difficult problems in their way. They draw on their experiences of past traumatic events to support their current situation and try to maintain a positive mindset and engage in purposeful activities to slow down the process of frailty. Frail older patients need professional institutions to provide care services, caregivers to listen to their inner thoughts, care institutions to provide a rich social life, and the care and companionship of relatives and friends.

4.1 Dynamically assessing the physical and mental status of frail older patients and providing personalized multidimensional management plans

Frail older patients may have other diseases in addition to frailty and may be in a state of multidimensional frailty, comorbidity, or polypharmacy (34, 35). This complicates and challenges the assessment of the risks and benefits of a single chronic disease and makes it difficult to intervene with conventional care programs (36). Therefore, it is necessary to dynamically assess their physical and mental states and obtain the latest information promptly to formulate management plans tailored to their individual needs. Personalized management plans may include different levels of exercise training and equipment use, nutritional intervention plans, medication guidance, psychological intervention, and social support. An RCT demonstrated that a personalized fall prevention program based on multi-component and multi-factor interventions significantly reduced the incidence of falls among community-dwelling individuals with stroke, Parkinson’s disease, or frailty, and improved their balance function compared to standard care (37). Future studies may consider combining personalized multidimensional management programs with remote guidance and monitoring to overcome location and time constraints (38).

4.2 Listening to their inner thoughts and involving them in their care plans

A care management plan that is easy to adhere to and accept is even more important for frail old individuals. Involving them in the development of care plans (rehabilitation plans, dietary plans, exercise plans, daily schedules) and listening to their thoughts and feelings can help identify and reduce potential barriers to plan implementation (39). A compassionate, attentive, and polite care team can promote favorable cooperation and practices, thereby improving the quality of care (40, 41). This makes patients feel respected and understood, enabling them to receive treatment and care with dignity and follow people-oriented physical and psychological care. A qualitative study of preventive home visit services for patients over the age of 80 or with chronic illnesses showed that favorable communication skills can enhance patients’ self-esteem and make them feel that they can control their health, thereby motivating them to participate in health-promoting activities (33, 42).

4.3 Providing multi-channel information support

With the widespread development of information technology platforms, patients now have access to health management information in various ways. Currently, the most common method is based on the Internet of Things technology, which uses wearable devices and sensors to identify and monitor their digital biomarkers (such as gait, activity, sleep, heart rate, hand movements, and spatial mobility) to obtain more intuitive and dynamic health data (43, 44). In addition, VR technology can be combined with deep learning to enhance the immersive experience and dynamic adaptability of information platforms, thereby improving patient engagement and training compliance (45). Current research has mostly focused on getting and monitoring patient information to help prevent and control adverse events. Future research should focus on integrating these topics into broader research to meet the changing and personalized care needs of older adults.

4.4 Strengthening peer support and family support

Receiving care in familiar surroundings can help frail older patients feel more confident about their treatment, become more independent, and increase their motivation to achieve their rehabilitation goals. A prospective study found that “virtual contact with children less than once a week,” “loneliness,” and “social support that can provide financial assistance” were important factors affecting frailty in older adults (46). A scoping review of qualitative analysis indicated that interventions involving social engagement can enhance comfort, enjoyment, and self-worth among older adults with mild cognitive impairment (47). Therefore, it is recommended that future nursing plans consider patients’ social networks to provide maximum family and peer support. In addition, community or nursing homes can regularly hold group psychological support sessions and encourage family participation, which will help improve patients’ social weakness.

4.5 Strengths and limitations

To our knowledge, this is the first systematic review to propose a meta-integration of qualitative studies to comprehensively understand the real experiences and care needs of frail older patients through a multidimensional assessment. However, this study only focused on the real experiences and care needs of frail older patients and did not consider the views of caregivers or other professionals, which may affect the completeness of our findings. Future research should include more qualitative studies to explore the real experiences of frail older adults receiving care in different economic and cultural contexts. Based on these findings, targeted care measures should be developed to promote the physical and mental transition of frail older adults, alleviate their discomfort during the transition period, and improve their quality of life.

5 Conclusion

Our study uses meta-integration to gain an in-depth understanding of the real experiences and care needs of frail older patients. It reveals the multidimensional challenges faced by patients in physiology, psychology, and behavior. It also identifies the care needs of frail older patients in terms of professional services and social support. This suggests that care facilities and professionals should provide multi-channel, personalized, multidimensional care plans while increasing patient participation and emphasizing peer support and family support.

Data availability statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/Supplementary material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Author contributions

SP: Conceptualization, Methodology, Resources, Writing – original draft. HH: Conceptualization, Formal analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Resources, Writing – original draft. XL: Formal analysis, Methodology, Writing – original draft. JK: Conceptualization, Formal analysis, Investigation, Writing – original draft. XW: Formal analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Resources, Writing – review & editing. YT: Supervision, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declare that no financial support was received for the research and/or publication of this article.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The authors declare that no Gen AI was used in the creation of this manuscript.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Supplementary material

The Supplementary material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fpubh.2025.1679832/full#supplementary-material

References

1. Hoogendijk, EO, Afilalo, J, Ensrud, KE, Kowal, P, Onder, G, and Fried, LP. Frailty: implications for clinical practice and public health. Lancet. (2019) 394:1365–75. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(19)31786-6

2. Kojima, G, Liljas, AEM, and Iliffe, S. Frailty syndrome: implications and challenges for health care policy. Risk Manag Healthc Policy. (2019) 12:23–30. doi: 10.2147/RMHP.S168750

3. Tang, D, Sheehan, KJ, Goubar, A, Whitney, J, and Dl, O'CM. The temporal trend in frailty prevalence from 2011 to 2020 and disparities by equity factors among middle-aged and older people in China: a population-based study. Arch Gerontol Geriatr. (2025) 133:105822. doi: 10.1016/j.archger.2025.105822

4. Davidson, SL, Lee, J, Emmence, L, Bickerstaff, E, Rayers, G, Davidson, E, et al. Systematic review and meta-analysis of the prevalence of frailty and pre-frailty amongst older hospital inpatients in low- and middle-income countries. Age Ageing. (2025) 54:afae279. doi: 10.1093/ageing/afae279

5. Ofori-Asenso, R, Lee Chin, K, Mazidi, M, Zomer, E, Ilomaki, J, Ademi, Z, et al. Natural regression of frailty among community-dwelling older adults: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Gerontologist. (2020) 60:e286–98. doi: 10.1093/geront/gnz064

6. Dugravot, A, Fayosse, A, Dumurgier, J, Bouillon, K, Rayana, TB, Schnitzler, A, et al. Social inequalities in multimorbidity, frailty, disability, and transitions to mortality: a 24-year follow-up of the Whitehall II cohort study. Lancet Public Health. (2020) 5:e42–50. doi: 10.1016/S2468-2667(19)30226-9

7. He, X, Jing, W, Zhu, R, Wang, Q, Yang, J, Tang, X, et al. Association of Reversible Frailty with all-cause mortality risk in community-dwelling older adults and analysis of factors affecting frailty reversal in older adults. J Am Med Dir Assoc. (2025) 26:105527. doi: 10.1016/j.jamda.2025.105527

8. Wang, S, Li, Q, Wang, S, Huang, C, Xue, QL, Szanton, SL, et al. Sustained frailty remission and dementia risk in older adults: a longitudinal study. Alzheimers Dement. (2024) 20:6268–77. doi: 10.1002/alz.14109

9. Theou, O, Stathokostas, L, Roland, KP, Jakobi, JM, Patterson, C, Vandervoort, AA, et al. The effectiveness of exercise interventions for the management of frailty: a systematic review. J Aging Res. (2011) 2011:569194. doi: 10.4061/2011/569194

10. Sirikul, W, Buawangpong, N, Pinyopornpanish, K, and Siviroj, P. Impact of multicomponent exercise and nutritional supplement interventions for improving physical frailty in community-dwelling older adults: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Geriatr. (2024) 24:958. doi: 10.1186/s12877-024-05551-8

11. Sun, X, Liu, W, Gao, Y, Qin, L, Feng, H, Tan, H, et al. Comparative effectiveness of non-pharmacological interventions for frailty: a systematic review and network meta-analysis. Age Ageing. (2023) 52:afad004. doi: 10.1093/ageing/afad004

12. Mehrabi, F, Pomeroy, ML, Cudjoe, TKM, Jenkins, E, Dent, E, and Hoogendijk, EO. The temporal sequence and reciprocal relationships of frailty, social isolation and loneliness in older adults across 21 years. Age Ageing. (2024) 53:afae215. doi: 10.1093/ageing/afae215

13. Walsh, D, and Downe, S. Meta-synthesis method for qualitative research: a literature review. J Adv Nurs. (2005) 50:204–11. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2648.2005.03380.x

14. Cooper, C, Booth, A, Varley-Campbell, J, Britten, N, and Garside, R. Defining the process to literature searching in systematic reviews: a literature review of guidance and supporting studies. BMC Med Res Methodol. (2018) 18:85. doi: 10.1186/s12874-018-0545-3

15. Tong, A, Flemming, K, McInnes, E, Oliver, S, and Craig, J. Enhancing transparency in reporting the synthesis of qualitative research: ENTREQ. BMC Med Res Methodol. (2012) 12:181. doi: 10.1186/1471-2288-12-181

16. Lockwood, C, Munn, Z, and Porritt, K. Qualitative research synthesis: methodological guidance for systematic reviewers utilizing meta-aggregation. Int J Evid Based Healthc. (2015) 13:179–87. doi: 10.1097/XEB.0000000000000062

17. Thomas, J, and Harden, A. Methods for the thematic synthesis of qualitative research in systematic reviews. BMC Med Res Methodol. (2008) 8:45. doi: 10.1186/1471-2288-8-45

18. Combes, S, Gillett, K, Norton, C, and Nicholson, CJ. The importance of living well now and relationships: a qualitative study of the barriers and enablers to engaging frail elders with advance care planning. Palliat Med. (2021) 35:1137–47. doi: 10.1177/02692163211013260

19. Frost, R, Kharicha, K, Jovicic, A, Liljas, AE, Iliffe, S, Manthorpe, J, et al. Identifying acceptable components for home-based health promotion services for older people with mild frailty: a qualitative study. Health Soc Care Community. (2018) 26:393–403. doi: 10.1111/hsc.12526

20. Frost, R, Nair, P, Aw, S, Gould, RL, Kharicha, K, Buszewicz, M, et al. Supporting frail older people with depression and anxiety: a qualitative study. Aging Ment Health. (2020) 24:1977–84. doi: 10.1080/13607863.2019.1647132

21. Nair, P, Walters, K, Aw, S, Gould, R, Kharicha, K, Buszewicz, MC, et al. Self-management of depression and anxiety amongst frail older adults in the United Kingdom: a qualitative study. PLoS One. (2022) 17:e0264603. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0264603

22. Warmoth, K, Lang, IA, Phoenix, C, Abraham, C, Andrew, MK, Hubbard, RE, et al. ‘Thinking you're old and frail’: a qualitative study of frailty in older adults. Age Soc. (2016) 36:1483–500. doi: 10.1017/S0144686X1500046X

23. Wilson, I, Ukoha-Kalu, BO, Okoeki, M, Clark, J, Boland, JW, Pask, S, et al. Experiences of a novel integrated Service for Older Adults at risk of frailty: a qualitative study. J Patient Experience. (2023) 10:23743735231199827. doi: 10.1177/23743735231199827

24. Young, HM, Ruddock, N, Harrison, M, Goodliffe, S, Lightfoot, CJ, Mayes, J, et al. Living with frailty and haemodialysis: a qualitative study. BMC Nephrol. (2022) 23:260. doi: 10.1186/s12882-022-02857-w

25. Hall, RK, Cary, MP Jr, Washington, TR, and Colón-Emeric, CS. Quality of life in older adults receiving hemodialysis: a qualitative study. Qual Life Res. (2020) 29:655–63. doi: 10.1007/s11136-019-02349-9

26. Schoenborn, NL, Van Pilsum Rasmussen, SE, Xue, Q-L, Walston, JD, McAdams-Demarco, MA, Segev, DL, et al. Older adults’ perceptions and informational needs regarding frailty. BMC Geriatr. (2018) 18:1–7. doi: 10.1186/s12877-018-0741-3

27. Eckerblad, J, Klompstra, L, Heinola, L, Rojlén, S, and Waldréus, N. What frail, older patients talk about when they talk about self-care—a qualitative study in heart failure care. BMC Geriatr. (2023) 23:818. doi: 10.1186/s12877-023-04538-1

28. Johansson, MM, Nätt, M, Peolsson, A, and Öhman, A. Frail community-dwelling older persons’ everyday lives and their experiences of rehabilitation–a qualitative study. Scand J Occup Ther. (2023) 30:65–75. doi: 10.1080/11038128.2022.2093269

29. Pan, E, Bloomfield, K, and Boyd, M. Resilience, not frailty: a qualitative study of the perceptions of older adults towards “frailty”. Int J Older People Nursing. (2019) 14:e12261. doi: 10.1111/opn.12261

30. Barnes, K, Hladkowicz, E, Dorrance, K, Bryson, GL, Forster, AJ, Gagné, S, et al. Barriers and facilitators to participation in exercise prehabilitation before cancer surgery for older adults with frailty: a qualitative study. BMC Geriatr. (2023) 23:356. doi: 10.1186/s12877-023-03990-3

31. Fret, B, De Donder, L, Lambotte, D, Dury, S, Van der Elst, M, De Witte, N, et al. Access to care of frail community-dwelling older adults in Belgium: a qualitative study. Prim Health Care Res Dev. (2019) 20:e43. doi: 10.1017/S1463423619000100

32. Jadczak, AD, Dollard, J, Mahajan, N, and Visvanathan, R. The perspectives of pre-frail and frail older people on being advised about exercise: a qualitative study. Fam Pract. (2018) 35:330–5. doi: 10.1093/fampra/cmx108

33. Behm, L, Ivanoff, SD, and Zidén, L. Preventive home visits and health--experiences among very old people. BMC Public Health. (2013) 13:378. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-13-378

34. Radcliffe, E, Saucedo, AR, Howard, C, Sheikh, C, Bradbury, K, Rutter, P, et al. Development of a complex multidisciplinary medication review and deprescribing intervention in primary care for older people living with frailty and polypharmacy. PLoS One. (2025) 20:e0319615. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0319615

35. Zhao, L, Chang, B, Hu, Q, Chen, X, Du, J, and Shao, S. The health care needs of multidimensional frail elderly patients with multimorbidity in primary health-care settings: a qualitative study. BMC Prim Care. (2025) 26:128. doi: 10.1186/s12875-025-02836-8

36. Oboh, L. Deprescribing in people living with frailty, multimorbidity and polypharmacy. Prescriber. (2024) 35:9–16. doi: 10.1002/psb.2137

37. La Porta, F, Lullini, G, Caselli, S, Valzania, F, Mussi, C, Tedeschi, C, et al. Efficacy of a multiple-component and multifactorial personalized fall prevention program in a mixed population of community-dwelling older adults with stroke, Parkinson's disease, or frailty compared to usual care: the PRE.C.I.S.A. randomized controlled trial. Front Neurol. (2022) 13:943918. doi: 10.3389/fneur.2022.943918

38. Scherrenberg, M, Marinus, N, Giallauria, F, Falter, M, Kemps, H, Wilhelm, M, et al. The need for long-term personalized management of frail CVD patients by rehabilitation and telemonitoring: a framework. Trends Cardiovasc Med. (2023) 33:283–97. doi: 10.1016/j.tcm.2022.01.015

39. Michie, S, Johnston, M, Francis, J, Hardeman, W, and Eccles, M. From theory to intervention: mapping theoretically derived behavioural determinants to behaviour change techniques. Appl Psychol. (2008) 57:660–80. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-0597.2008.00341.x

40. Mastellos, N, Gunn, L, Harris, M, Majeed, A, Car, J, and Pappas, Y. Assessing patients' experience of integrated care: a survey of patient views in the north West London integrated care pilot. Int J Integr Care. (2014) 14:e015. doi: 10.5334/ijic.1453

41. Stephen Ekpenyong, M, Nyashanu, M, Ossey-Nweze, C, and Serrant, L. Exploring the perceptions of dignity among patients and nurses in hospital and community settings: an integrative review. J Res Nurs. (2021) 26:517–37. doi: 10.1177/1744987121997890

42. Williams, V, Smith, A, Chapman, L, and Oliver, D. Community matrons--an exploratory study of patients' views and experiences. J Adv Nurs. (2011) 67:86–93. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2648.2010.05458.x

43. Huang, J, Zhou, S, Xie, Q, Yu, J, Zhao, Y, and Feng, H. Digital biomarkers for real-life, home-based monitoring of frailty: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Age Ageing. (2025) 54:afaf108. doi: 10.1093/ageing/afaf108

44. Tang, V, Choy, KL, Ho, GTS, Lam, HY, and Tsang, YP. An IoMT-based geriatric care management system for achieving smart health in nursing homes. Ind Manag Data Syst. (2019) 119:1819–40. doi: 10.1108/IMDS-01-2019-0024

45. Yu, Z, and Dang, J. The effects of the generative adversarial network and personalized virtual reality platform in improving frailty among the elderly. Sci Rep. (2025) 15:8220. doi: 10.1038/s41598-025-93553-w

46. Marcelino, KGS, Braga, LS, Andrade, FB, Giacomin, KC, Lima-Costa, MF, and Torres, JL. Frailty and social network among older Brazilian adults: evidence from ELSI-Brazil. Rev Saude Publica. (2024) 58:51. doi: 10.11606/s1518-8787.2024058005525

47. Mohammad Hanipah, J, Mat Ludin, AF, Singh, DKA, Subramaniam, P, and Shahar, S. Motivation, barriers and preferences of lifestyle changes among older adults with frailty and mild cognitive impairments: a scoping review of qualitative analysis. PLoS One. (2025) 20:e0314100. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0314100

Keywords: frailty, older adults, experience, needs, qualitative research, meta-synthesis

Citation: Peng S, He H, Luo X, Kang J, Wang X and Tan Y (2025) Real experiences and care needs of frail older patients: a systematic review of qualitative studies. Front. Public Health. 13:1679832. doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2025.1679832

Edited by:

Matthew Aplin-Houtz, Brooklyn College, United StatesCopyright © 2025 Peng, He, Luo, Kang, Wang and Tan. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Yongqiong Tan, MTEyNTg2NTQ3OEBxcS5jb20=

Shuo Peng

Shuo Peng Hongzhi He2

Hongzhi He2