- 1Department of Women and Children’s Health, School of Life Course and Population Sciences, King’s College London, London, United Kingdom

- 2The ENGAGE Study Patient and Public Involvement and Engagement Advisory Group, King’s College London, London, United Kingdom

- 3Department of Psychology, Institute of Population Health, University of Liverpool, Liverpool, United Kingdom

Background: Delayed or reduced antenatal care use by pregnant women may result in poorer outcomes. ‘Candidacy’ is a synthetic framework which outlines how people’s eligibility for healthcare is jointly negotiated. This meta-ethnography aimed to identify – through the lens of candidacy – factors affecting experiences of care-seeking during pregnancy by women from underserved communities in high-income countries (HICs).

Methods: Six electronic databases were systematically searched, extracting papers published from January 2018 to January 2023, updated to May 2025, and having relevant qualitative data from marginalized and underserved groups in HICs. Methodological quality of included papers was assessed using the Critical Appraisal Skills Program. Meta-ethnography was used for analytic synthesis and findings were mapped to the Candidacy Framework.

Results: Studies (N = 51), with data from 1,347 women across 14 HICs were included. A total of 12 sub-themes across five themes were identified: (1) Autonomy, dignity, and personhood; (2) Informed choice and decision-making; (3) Trust in and relationship with healthcare professionals; (4) Differences in healthcare systems and cultures; and (5) Systemic barriers. Candidacy constructs to which themes were mapped were predominantly joint- (navigation of health system), health system- (permeability of services), and individual-level (appearances at health services). Mapping to Candidacy Framework was partial for seven sub-themes, particularly for individuals with a personal or family history of migration. The meta-ethnography allowed for the theory: ‘Respect, informed choice, and trust enhances candidacy while differences in healthcare systems, culture, and systemic barriers have the propensity to diminish it’.

Conclusion: Improvements in antenatal care utilization must focus on the joint (service-user and -provider) nature of responsibility for care-seeking, through co-production. We suggest two additional Candidacy Framework constructs: ‘intercultural dissonance’ and ‘hostile bureaucracy’, which reflect the multi-generational impact of migration on healthcare utilization and the intersection of healthcare utilization with a hostile and bureaucratic environment.

Systematic review registration: https://www.crd.york.ac.uk/PROSPERO/view/CRD42023389306, CRD42023389306.

1 Introduction

Routine antenatal care is a globally recommended public health service enabling healthcare professionals (HCPs) to provide essential information, counseling, maternal and fetal assessments, and encourage use of maternity services (1, 2). Delayed or reduced antenatal care use, in both high- (HICs) and low−/middle-income countries (LMICs), is linked to adverse pregnancy outcomes, including stillbirth (3), and neonatal morbidity (4).

Research on maternity care-seeking has largely focused on LMICs, where barriers are often financial, geographic, or linked to knowledge gaps beliefs about the importance of maternity care (5). In contrast, many HICs offer free healthcare at point of access, yet barriers remain. Even with structurally accessible services, uptake remains low in certain communities, including those of lower socio-economic status (SES), minority ethnic groups, sexual minorities, and people living with disabilities (6–8).

A recent meta-synthesis of qualitative studies in HICs highlighted multiple barriers (e.g., socio-demographic disadvantage, system navigation, lack of tailored care, frequent carer changes) and facilitators (e.g., positive pregnancy attitudes, good HCP interactions, social support) (9). Furthermore, the pandemic introduced additional barriers to care-seeking (i.e., social isolation, personal infection risk (10), poorer mental well-being (11), continuing restrictions for perinatal populations after lockdowns (12), and navigating healthcare service reconfigurations (13, 14)), with experiences of care being reported more negatively with poorer mental health outcomes (11–18).

‘Candidacy’ refers to people’s eligibility for accessing healthcare. It was developed to explain unequal access to healthcare, despite universal health coverage, and to go beyond simple measurement of health utilization, particularly by marginalized groups (19). The theoretical framework of ‘candidacy’ refers to healthcare access as negotiated jointly between service-user and healthcare system. It describes a dynamic process, subject to external influences, from people and their social context, as well as available resources and service structure (19). There are seven constructs of: identification, navigation, permeability of services, appearances at health services, adjudication, offers and resistance, and local production of candidacy (19). This framework was chosen to guide this systematic review in order to establish a theory driven structure, moving beyond simply identifying barriers to rather describe the process by which access is negotiated. This is crucial in perinatal contexts where marginalised women face layered challenges related to stigma, institutional bias, and bureaucratic hurdles in the process of accessing and engaging with care (20). Mapping systematic review results to the constructs of the Candidacy framework allowed comparison of evidence across diverse populations in a coherent way. As used previously in healthcare research, this framework lends itself well to understanding the latent factors influencing care-seeking among marginalised groups, for which it was first developed (21–26). The framework was employed within the systematic review in order to strengthen analytical rigor and improve the potential to generate actionable insights.

The aim of this systematic review and meta-ethnography was to synthesize qualitative evidence from HICs, to identify – through the lens of candidacy – factors affecting experiences of care-seeking during pregnancy, by women and birthing people from underserved communities. We expand on previous work by focusing solely on underserved groups known to face additional barriers to care access, utilization, and engagement.

2 Methods

This review was registered with PROSPERO [CRD42023389306] and adheres to the PRISMA 2020 statement (Supplementary Table S1) (27).

2.1 Inclusion and exclusion criteria

The PEO (Population, Exposure, and Outcome) framework was used to formulate the search strategy as per the research aim (Supplementary Table S2).

• Population: Women and/or birthing people planning pregnancy, pregnant, or postpartum, in an HIC setting (as classified by the World Bank, 2024), and from an underserved community, defined as individuals or groups with one or more social risk factors, which may have resulted in them being systematically excluded or denied full opportunity to participate in economic, social, or civic life. Social risk factors were as expansive as possible, including: young or advanced maternal age; single mothers; low SES; any group identified as a minority within the study setting (e.g., ethnicity or sexual orientation); refugee, or asylum-seeker; facing homelessness, victim/survivor of domestic abuse; living in a deprived area; having a diagnosed mental health condition or learning disability; physical disability or chronic illness; substance abuse; and not speaking the language local to the country in which the healthcare was provided.

• Exposure: All routine antenatal and intrapartum care, comprising planned care before and during labor and birth, to optimize outcomes for mothers and babies, as defined by WHO guidelines (WHO, 2016). This care includes the minimal number of planned antenatal care appointments, health promotion activities (such as advice on healthy diet and exercise), urine and blood tests (such as to screen for anemia), vaccination and supplementation (such as with iron), monitoring of fetal wellbeing, additional care for women and/or birthing people at higher risk, and care provided for labor and birth (such as for progress in labor and skilled birth attendance). The setting could be within hospitals, the community, or at home.

• Outcome: Care-seeking experiences, including health knowledge, behaviors, perceptions, and healthcare utilizations.

Study designs included: descriptive, exploratory, and interpretive qualitative studies; ethnographies; and observational or mixed-methods studies (including surveys with open-ended questions) where qualitative data had been formally analyzed and presented (24). Studies were published between Jan 2018–23, updated to May 2025, and only considered if published in English-language. Studies of postnatal care were excluded due to its variation between countries, and its fragmented nature, often spanning services in primary through to quaternary care settings.

2.2 Search strategy and selection

Electronic databases of SCOPUS, MEDLINE, EMBASE, CINAHL, Global Health, PsychINFO, and MIDRIS were systematically searched for articles published between 1 January 2018 and 1 January 2023, updated to May 2025 (28). For details of the search terms and keywords used, see Supplementary Table S2.

Duplicate references were removed using Mendeley reference manager software, and citations were uploaded to Rayyan (29), a web-based tool for conducting systematic reviews. At least two members of the study team (TD, HRJ, GH, SAS, LAM) independently screened each record, by title and abstract, followed by full-text review. Regular discussions were held to resolve by consensus any disagreements in screening decisions.

2.3 Data extraction

Data extraction was randomly allocated to one of two reviewers (TD, GH), with 20% of included studies extracted independently by both reviewers to check between-reviewer reliability. A bespoke Microsoft Excel spreadsheet was used to abstract study characteristics (i.e., title, reference, publication year, study setting, aim, participant inclusion criteria, intersectional approach, data collection and analytic methodologies), and any impact of the pandemic on care-seeking. Regular discussions were organized to discuss any disagreements, and to collaborate on the creation of a consolidated set of themes with consistent labels.

2.4 Quality assessment

The Critical Appraisal Skills Program (CASP) was used to assess the quality of included studies (30) across 10 items: clearly-stated objective, appropriateness of using qualitative study design, justification of research design, recruitment strategy, data collection method, author reflexivity, ethical considerations, data analysis method, clear findings, and value of the findings. CASP does not assign a score, but for ease of interpretation, we assigned points to answers for each checklist item: 0 points for ‘No’, 1 for ‘Cannot tell’, and 2 for ‘Yes’.

2.5 Data synthesis

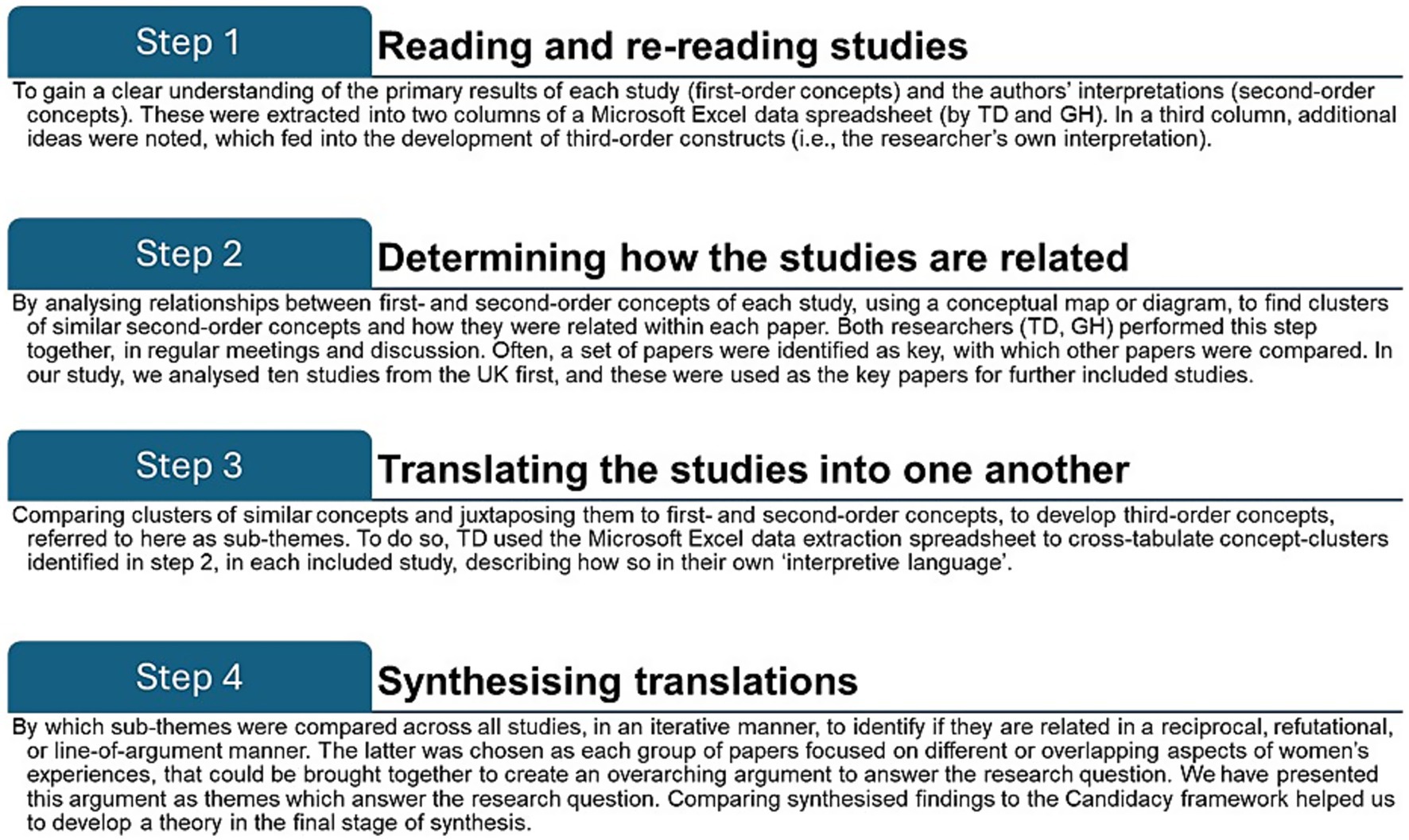

Meta-ethnography (31) was employed for analytic data synthesis, which is a particularly useful approach when addressing complex questions, as it enables comparison between and across published studies, and creates higher-order themes which can be newly-interpreted, based on the wealth of integrated data (31, 32). Syntheses can be reciprocal (studies are similar to each other and shared themes across the studies are summarized), refutational (studies refute each other and themes are juxtaposed against each other), or ‘line of argument’ (studies interpret the same phenomenon but from different aspects, the synthesis creating a whole greater than the sum of its individual parts) (32). Typically, there are four main steps, as employed by other researchers (33, 34), outlined in Figure 1, (32–34).

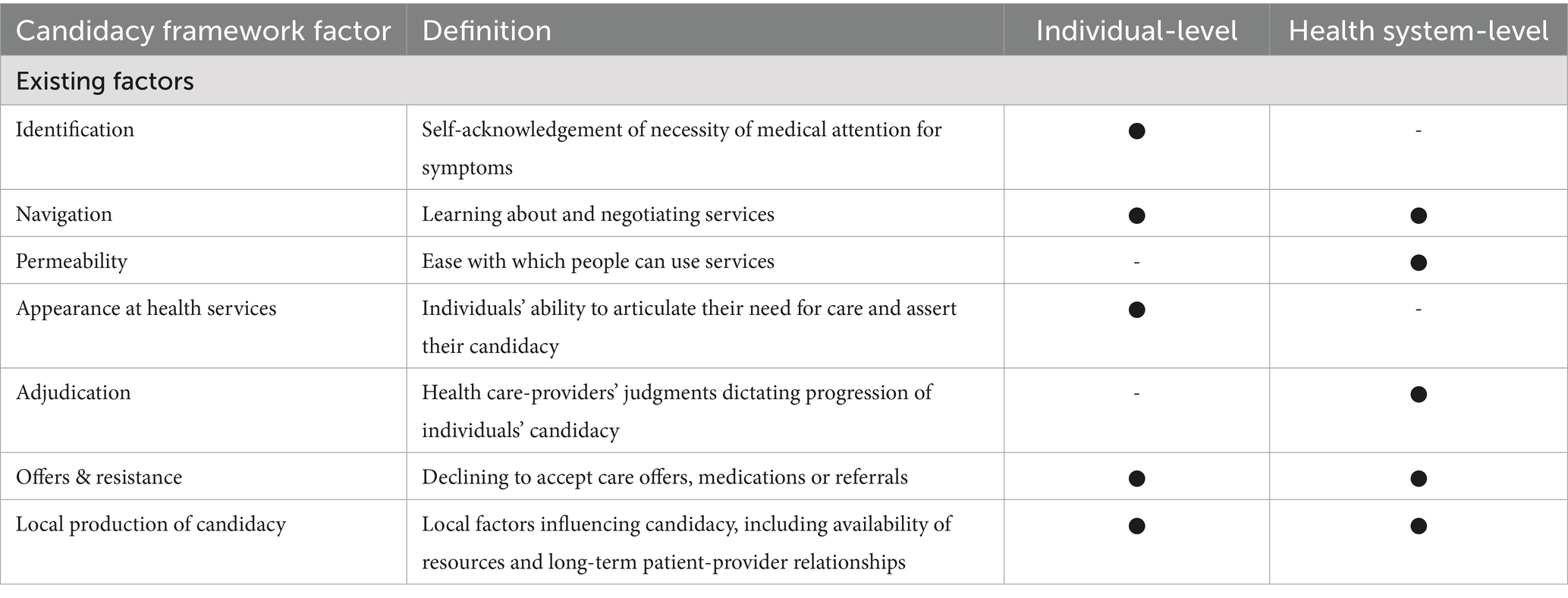

Intersectional approaches in included studies were considered to compare participant groups. Synthesized themes and sub-themes were mapped to one or more of the seven components of the Candidacy Framework (19), as in Table 1, to determine how the identified factors influence eligibility of candidacy; with the weight of each theme contributing to candidacy was calculated.

3 Results

3.1 Search and selection

Of 3,098 records identified, 2,493 underwent title and abstract screening, 68 underwent full-text review, and 45 were included (35–79) (see Supplementary Figure S1). An updated search to May 2025, identified six additional records for analysis (80–85).

3.2 Description of included studies

The 51 included studies provided data from 1,347 service-users. Studies were published between 2018 and 2025, from 14 countries, most commonly the USA (n = 13 studies) (36–38, 46, 52, 53, 57, 61, 64, 67, 68, 80) and the UK (n = 13) (58, 70–79, 84, 85), followed in frequency by Australia (n = 5) (43, 49, 56, 66, 82), Norway (47, 50, 69), Denmark (45, 62, 63), Sweden (35, 48, 51), Switzerland (41, 42), Netherlands (40, 65), New Zealand (44, 81), Canada (39), Germany (60), Israel (55), Russia (83), and Saudi Arabia (59). The most common data collection method was in-depth interviews (n = 34) (35, 39–41, 43, 45, 48–51, 53–60, 62–64, 67–69, 71, 75, 76, 78–83, 85), followed by focus groups (n = 13) (36–38, 42, 44, 46, 47, 52, 61, 65, 70, 72, 74), surveys with open-ended questions (66, 73, 77, 84), and ethnographic observations (70). Some studies used multiple methods (n = 6) (36, 44, 46, 47, 70, 74). Most studies utilized thematic analyses (n = 31) (37, 38, 41, 42, 44, 47, 52, 54–59, 61, 63, 65, 66, 68–71, 73, 74, 77–82, 84, 85); others used framework analyses (n = 5) (40, 64, 72, 75, 76), content analyses (n = 5) (35, 48, 51, 60, 67), grounded theory analysis (n = 4) (36, 39, 46, 53), interpretative phenomenological analysis (49, 83), systematic text condensation (45, 50), qualitative comparative analysis (43, 57), or interpretive description analysis (68). Two studies (50, 66) evaluated the impact of the pandemic on care-seeking experiences.

Social risk factors included: being migrants, refugees, or asylum-seekers (n = 18) (35, 36, 42, 45–48, 50, 51, 56, 60, 65, 67–70, 74, 75, 79); being racial, ethnic or religious minorities (n = 9) (37–39, 44, 52, 54, 55, 72, 81); having low SES (n = 8) (71–73, 76, 79–82); not being able to speak the local language (n = 7) (41, 51, 54, 57, 58, 60, 66, 85); having previous interaction with social services or child protection services (n = 4) (62, 63, 76, 84); having substance abuse issues (n = 4) (53, 55, 62–65, 84, 86) having learning, intellectual, or physical disability or impairment (n = 3) (77, 81, 84); being a victim of domestic abuse or intimate partner violence (n = 3) (43, 79, 84); being a young mother (n = 3) (79, 81, 84); living in a rural setting (n = 3) (52, 82, 83); having missed or delayed antenatal care (n = 2) (59, 64); experiencing homelessness (n = 2) (78, 84); or having transgender pregnancy (n = 1) (81). Nine studies described participants with medical complexity such as preterm birth and gestational diabetes (36, 38, 40, 48, 52, 56, 61–63). For further details, see Supplementary Table S3.

3.3 Quality assessment

Study quality was moderate-to-high (Supplementary Table S4). Of a possible score of 20, all studies scored ≥14, as follows (60):14/20 (n = 2) (39, 66), 15/20 (n = 4) (35, 54, 75, 84), 16/20 (n = 4) (53, 61, 69, 73), 17/20 (n = 15) (36, 44, 47–49, 57, 59, 60, 63, 65, 67, 74, 76, 78, 79), 18/20 (n = 13) (41, 42, 45, 50, 52, 55, 56, 64, 71, 72, 77, 83, 85), 19/20 (n = 5) (37, 43, 46, 58, 80, 81), and 20/20 (n = 7) (38, 40, 51, 62, 68, 70, 82). Those highest-scoring studies which did not reach 20/20 often fell short by missing consideration of the relationship between researchers and participants and associated ethical issues.

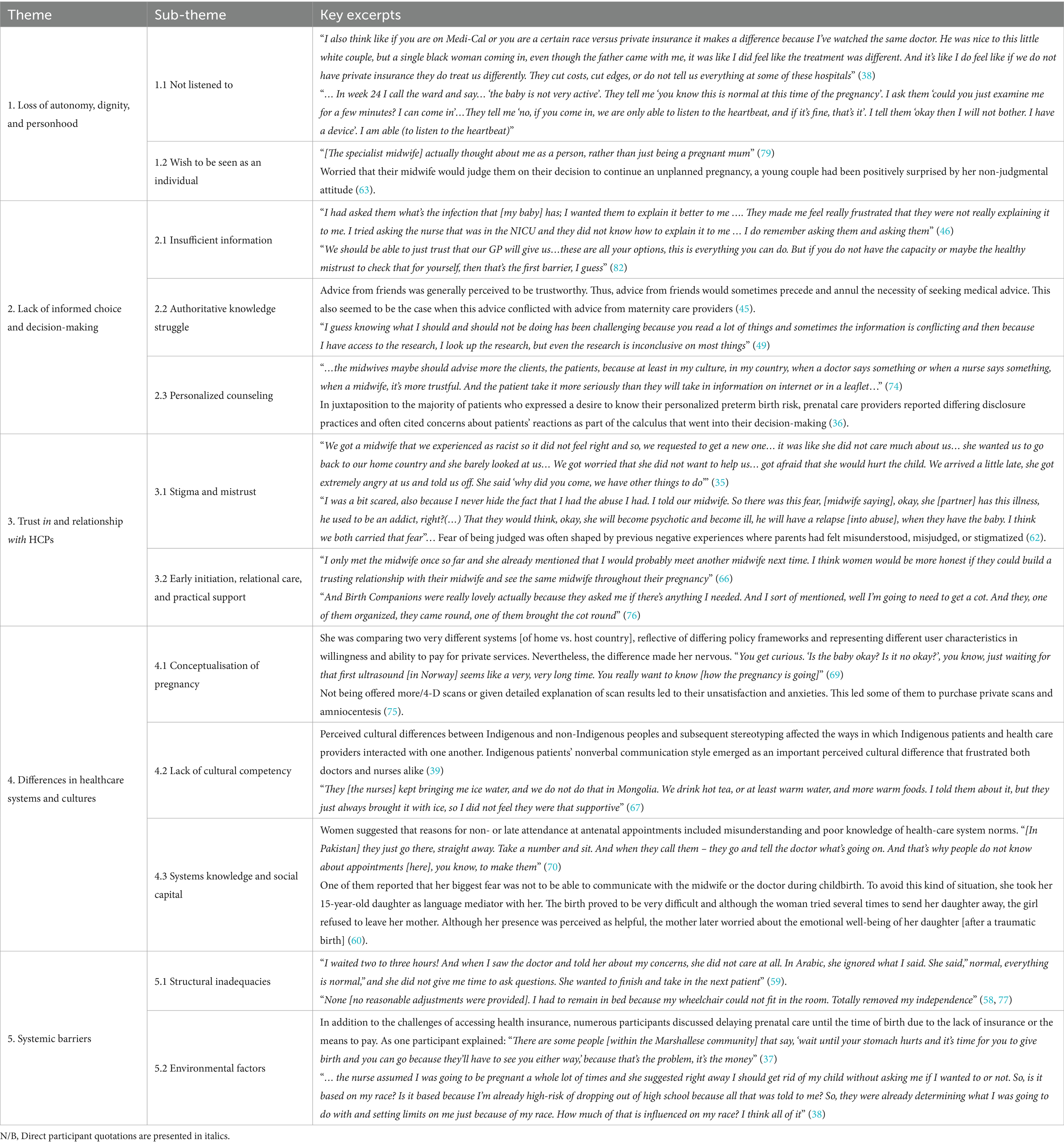

3.4 Analytic synthesis and findings

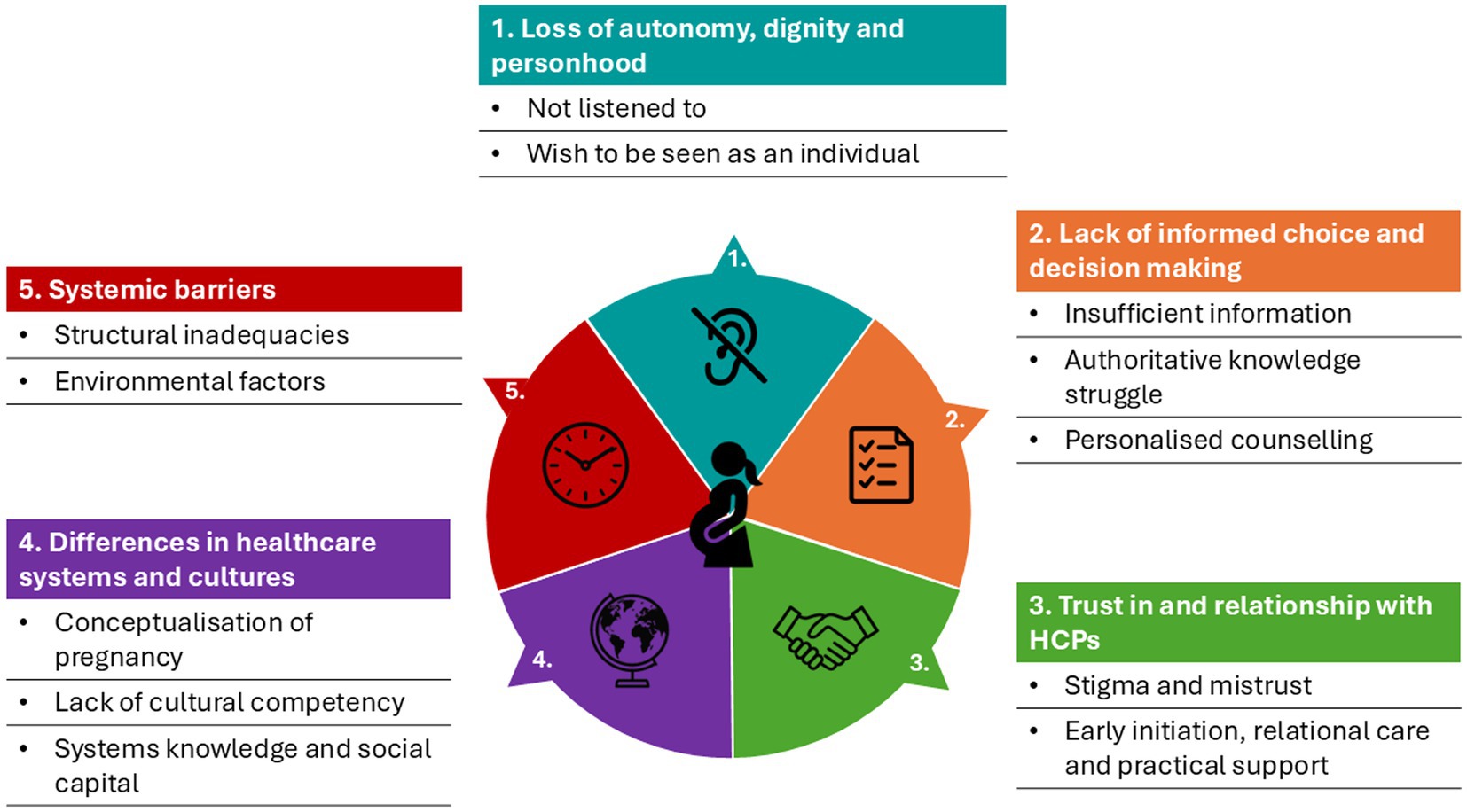

Figure 2 depicts the theory derived from the data: ‘Respect, informed choice, and trust enhances candidacy whilst differences in healthcare systems, culture, and systemic barriers have the propensity to diminish it’. The 12 sub-themes were grouped into five main themes: (1) Autonomy, dignity, and personhood; (2) Informed choice and decision-making; (3) Trust in and relationship with HCP; (4) Differences in healthcare systems and cultures; and (5) Systemic factors. Excerpts of text from individual studies are presented in Table 2 to support the synthesised findings (direct participant quotations are in italics), selected to be the most representative of the analytical theme and idea being described.

Figure 2. Findings of factors affecting women’s experience of care-seeking. Illustrations created using Chat GPT.

3.4.1 Theme 1: Autonomy, dignity and personhood

This theme was identified in 16 studies (35, 38, 42, 45, 46, 55, 59, 63, 67, 71, 76–79), and had two sub-themes.

3.4.1.1 Not listened to

Participants expressed they were not listened to, their concerns were dismissed, or they were made to feel unintelligent and judged for asking questions (38). Some attributed this treatment to personal characteristics, such as ethnicity. This led women to hesitate to ask further questions, attending appointments unless absolutely necessary, or engaging with maternity care overall (78). Some were unaware of their rights and the level of care to expect and request. This made women accept poor quality-of-care and discriminatory practices as part of standard maternity care (55).

3.4.1.2 Wish to be seen as an individual

Women wished to be respected and treated as individuals. They valued when effort was made to understand their background and life beyond pregnancy (79); this often had a protective effect on care-seeking and engagement and built capacity for positive parenting and health (76).

3.4.2 Theme 2: Informed choice and decision-making

This theme was identified in 25 studies (36, 37, 40, 43, 44, 46, 48–51, 56–59, 61, 69, 70, 72–74, 76, 79), and had three sub-themes.

3.4.2.1 Insufficient information

Women felt information was inadequate, and lacked justification for recommendations, which left them wanting more control over their care (56). Some studies reported women feeling HCPs’ own bias and perceptions of patients influenced the information they provided, so they offered only the information they deemed would be relevant for the patient (60). Women felt it fell to them to seek-out information (via friends and family, or online sources, often unofficial (75)), and make decisions about which recommendations to follow, although they felt those decisions were seldom fully-informed (40).

3.4.2.2 Authoritative knowledge struggle

Women often faced balancing information from various sources (70). This included differences in care between their home countries and their current healthcare system, between friends/family and HCPs, between care-providers, or between protocols in different hospitals (58, 70).

3.4.2.3 Personalised counseling

Women emphasized the value of personalized counseling by their HCP, peer support from their communities, and HCPs having the right tools to support women and families, such as knowledge of cultural practices (43, 74).

3.4.3 Theme 3: Trust in and relationship with HCPs

This theme was identified in 25 studies (35, 38–41, 48, 50–53, 58, 62, 63, 66, 68, 71, 76–79), and had two sub-themes.

3.4.3.1 Stigma and mistrust

The underserved populations studied were often already anxious about being pregnant, so trust played a particularly important role in determining if they attended appointments, disclosed their circumstances, or participated in maternity care (58). Many had established mistrust in HCPs and institutions in general, due to prior negative interactions with social care, immigration, or law enforcement (63, 78). Some feared being reported and their child being removed to services, and so they did not engage honestly with maternity HCPs (78). Women reported feeling unfit as mothers, and stigmatized when honest about social risk factors (e.g., prior drug use or homelessness) (53, 68).

3.4.3.2 Early initiation, relational care, and practical support

When maternity care was initiated early and there was relational care, this built trusting relationships with HCPs and facilitated open discussions (66, 78). Women with mental health issues felt more likely to fully disclose during psychosocial assessments, and those with disabilities did not have to reiterate their accessibility requirements at every appointment (66, 78).

Practical support (e.g., with baby food, blankets, or pushchairs), or emotional support when attending social care appointments helped women embrace new motherhood (48, 68). When they were supported in such ways, it enabled women to make long-lasting changes and prevent relapse to pre-pregnancy habits such as substance abuse.

3.4.4 Theme 4: Differences in healthcare systems and cultures

This theme was identified in 21 studies (37–39, 42, 45, 47, 48, 52, 56–58, 60, 61, 69–73, 75), and had three sub-themes.

3.4.4.1 Conceptualisation of pregnancy

Studies emphasized how pregnancy is conceptualized differently by setting. In some countries, antenatal care was described as highly-medicalised, with multiple appointments and ultrasound scans. In other settings, there may be only two or three contacts throughout pregnancy, even though official guidelines and recommendations may suggest more (42, 60). Such differences often concerned mothers who had migrated from one country to another and altered their health literacy and ability to risk-assess their pregnancies. Some women did take on board new opportunities; when given the choice and relevant information, women from minority ethnic communities in the UK expressed a desire to have more home births (72).

3.4.4.2 Lack of cultural competency

Differences in social norms around pregnancy, information shared, standard practice, role of the birth partner or other family members, and religious beliefs, greatly-influenced women’s views of the acceptability of care offered, or even the decision to attend appointments (39, 47, 56). Women felt that HCPs lacked cultural understanding and did not treat them with respect, which led to negative interactions.

3.4.4.3 Systems knowledge and social capital

Migrant women had trouble understanding how to access or use maternity care services in their host country, including when and how to make appointments (37, 47). Many such women lacked social capital, described as playing a protective role, particularly postnatally. Often, they lacked support from wider familial networks during maternity care, and in life generally, to interpret for them if they did not speak the local language (69).

3.4.5 Theme 5: Systemic barriers

This theme was identified in 24 studies (37–39, 42, 44, 47, 48, 51, 52, 55, 58–61, 64, 66, 71, 75–77), and had two sub-themes.

3.4.5.1 Structural inadequacies

Lack of flexibility in scheduling appointments, long wait-times in hospital, and rushed appointments with HCPs, posed barriers to engagement with maternity care (44, 61, 71). Studies reported poor communication between women and HCPs, due to a lack of interpreters or availability of healthcare information in other languages. Often, women resorted to methods such as Google Translate, which is not reliable for translating medical terminology, jargon, or medications (75). For those with physical disabilities and accessibility needs, lack of relevant provision left some women feeling that they had lost their dignity (77). Staff were reported as unaware of service users’ accessibility requirements (having not read their file beforehand), or unaccommodating.

3.4.5.2 Environmental factors

Social, economic, political, and religious aspects played roles in how women from underserved groups were treated in hospital (55). Societal prejudices and systemic discriminatory practices were reported to permeate personal care interactions (48). In systems where care is not free-to-access at the point-of-contact (such as in the United States), even with certain health insurance plans, financial constraints deterred women from seeking care until absolutely necessary (37).

3.5 Contribution to the candidacy framework

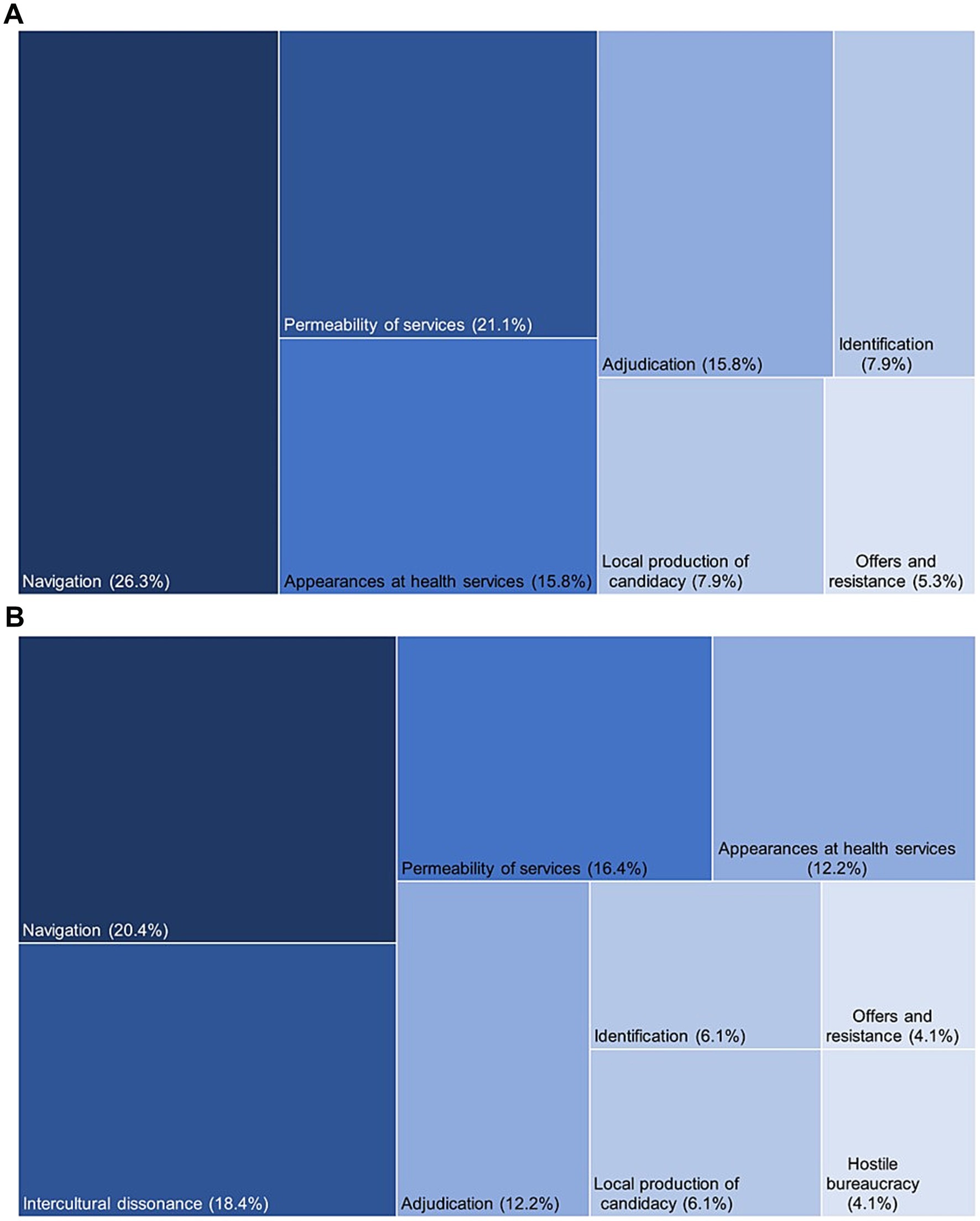

The 12 sub-themes of this meta-ethnography mapped onto all seven components of the Candidacy Framework, with two key observations: First, most sub-themes aligned with ‘navigation’ (n = 9) and ‘permeability of services’ (n = 6), which are joint and health system-level influences. Fewer connections were observed with other constructs: ‘adjudication’ (n = 6), ‘local production of candidacy’ (n = 3), ‘offers and resistance’ (n = 2), ‘appearances at health services’ (n = 5), and ‘identification’ (n = 3). Second, seven sub-themes only partially mapped to existing constructs: ‘authoritative knowledge struggle’, ‘stigma and mistrust’, ‘conceptualisation of pregnancy’, ‘lack of cultural competency’, ‘systems knowledge and social capital’, ‘structural inadequacies’, and ‘environmental factors’. This was especially true for those with a migrant background, suggesting the need for two additional constructs: intercultural dissonance (individual-level) and hostile bureaucracy (health system-level).

Intercultural dissonance encompasses additional barriers faced by those who are not native-born and experience a distinct difference in social norms and culture, medical and social knowledge and expectations, and language. Here, intergenerational relationships are altered by migration; for example, children (but not their parents) often speak (or speak more proficiently) the host country’s language, and are more familiar with the system, by virtue of having grown up there from a young age. As such, children take on more active roles in their parents’ healthcare decisions, such as acting as unofficial interpreters at care appointments, which may affect their parents’ ‘appearances at health services’ and ‘offers and resistance’ to care, as well as expose them to uncomfortable and potentially traumatic conversations and experiences.

Hostile bureaucracy sees migrant women often subject to discriminatory policies and precarious administrative practices in the host-country as compared to their home-country (86). These hostile, discriminatory immigration policies exist in most HICs, such as: restrictions on health coverage, welfare support, and right to rental properties; high visa application costs; and limits on qualifying employment. These policies, alongside negative societal attitude toward migrants and refugees, pose further barriers to integration into the host country, establishing a thriving life there, and accessing and engaging with healthcare. ‘Local production of candidacy’ is particularly diminished by these policies for migrant and refugee women.

Figure 3 shows a visual representation of the thematic contribution of our sub-themes to the original seven and extended 7 + 2 components of the Candidacy framework, respectively. For further details of the mapping process and candidacy framework components, see Supplementary Table S5, S6, respectively.

Figure 3. (A,B) Thematic contribution to the original and extended 7 + 2 Candidacy Framework, respectively.

4 Discussion

4.1 Main findings

This systematic review identified 51 qualitative studies documenting, across 14 HICs, maternity care-seeking experiences of more than 1,300 women from minoritised and underserved groups. Twelve sub-themes emerged across five themes: (1) Loss of dignity, autonomy, and personhood; (2) Lack of informed choice and decision-making; (3) Trust in and relationships with HCPs; (4) Differences between healthcare systems and cultures; and (5) Systemic barriers. Experiences were largely negative. While sub-themes aligned with all seven components of the Candidacy Framework, most mapped to ‘navigation’, ‘permeability of services’, and ‘appearances at health services’, highlighting shared responsibility for improving care. Two new constructs—intercultural dissonance and hostile bureaucracy—emerged, particularly affecting migrants through altered intergenerational roles and exclusionary immigration policies. The meta-ethnography provided an analytic synthesis, rendering the theory: ‘Respect, informed choice, and trust enhances candidacy whilst differences in healthcare systems, culture, and systemic barriers have the propensity to diminish it’.

4.2 Comparison with the literature

To our knowledge, this is the first systematic review focused exclusively on care-seeking experiences of diverse minoritised and underserved groups in HICs. Unlike our qualitative approach, most care-seeking research is quantitative, measuring attendance, visit frequency, or utilizations—often inconsistently defined (87) —and linking these to pregnancy outcomes. Frameworks like the social determinants of health (SDoH) model have been used to assess drivers of care-seeking, especially non-attendance (19, 26), including socio-cultural, political, and economic factors (19).

We build on a small number of reviews examining antenatal care among underserved groups (e.g., ethnic minorities, immigrants), which highlight complex barriers such as limited language skills, poor awareness of services, immigration and financial constraints, prior negative care experiences, and structural or organizational challenges (6, 88, 89).

This review found that care-seeking experiences were largely negative. A key issue was the lack of respectful treatment—dismissed concerns, unanswered questions, and unkind interactions—which left women feeling dehumanized (76, 79, 90). Prior research in LMICs shows that disrespectful care erodes trust and delays healthcare use (91, 92). For women with physical disabilities, inadequate attention to accessibility worsened this, leading to a loss of dignity (77). Stigma, discrimination, and insufficient information further undermined autonomy (56, 79). Quantitative studies also associate physical disability and one or more social risk factors to increased experiences of identity-related disrespect and reduced autonomy in maternity care (93, 94).

Our work demonstrates barriers to healthcare-seeking in pregnancy are jointly-driven, based on how frequently our sub-themes map to factors within the Candidacy Framework (19). Previous studies support this, identifying both system-level factors (e.g., organizational processes and system policies) (95–98) and individual-level factors (e.g., poor doctor-patient relationship (99), stigmatization (100), or being dismissed) (101). Improving care engagement for underserved women requires joint negotiation and co-production of services—such as the UK’s Maternity and Neonatal Voices Partnerships (MNVPs). The limited literature speaking to the constructs of the Candidacy Framework: ‘offers and resistance’ and ‘identification’ – joint- and individual-level factors – often places blame on women for low engagement attributing it to poor health literacy (58), problematising their language skils (102, 103), and further stigmatizing this already marginalised population.

A unique contribution of our study is the identification of intercultural dissonance and hostile bureaucracy as additions to the Candidacy Framework, reflecting the lasting and intergenerational effects of migration on care-seeking, including during pregnancy. Events of the last decade have emphasized the underserved nature of this population which has grown exponentially in the recent past due to various humanitarian crises. Differences in healthcare systems and cultures between ‘home’ countries and ‘host’ countries, significantly shape decisions about when and how to seek care, navigate services, and act on medical advice (70). This can lead to an authoritative knowledge struggle, where contradictory information (60, 104), may cause women to disengage from care altogether (45). Additionally, psychological research highlights how generational trauma and inherited knowledge influence wellbeing and behavior (105). A UK review of eight studies on asylum-seeking women identified barriers such as poor awareness of services, communication struggles, and stigma but did not explore how differing healthcare norms affect maternity experiences (98). Our meta-ethnographic approach, being generative and interpretive, was likely more attuned to these dynamics. Our proposed extension complements and builds on prior applications of the Candidacy Framework that have highlighted the unique challenges faced by migrants and minoritised groups in navigating healthcare (22, 106, 107). These have demonstrated how asylum seekers encounter systemic exclusions and bureaucratic hurdles (106, 107) that cannot be fully explained by the existing seven constructs (106, 107), and how cultural differences and intergenerational dynamics shape access (22). By adding the constructs of intercultural dissonance and hostile bureaucracy, our work extends this trajectory, offering conceptual tools that better capture the multi-generational, structural, and cultural dimensions of exclusion in perinatal care-seeking among underserved women.

While our synthesis identifies common themes in migrant women’s experiences, the 13 HICs represented (e.g., United Kingdom, United States, Saudi Arabia) vary widely in healthcare models, migrant entitlements, and cultural expectations. For instance, healthcare fees in the US or restrictions on undocumented migrants in Europe may intensify systemic barriers compared to countries with universal access. These structural and cultural differences affect the transferability of findings, particularly in relation to how barriers manifest and are addressed. Tools such as the WHO Health Financing Progress Matrix or Migrant Integration Policy Index which examines how well a country’s health financing policies align with achieving universal coverage (108), and policies to integrate migrants and other marginalised groups into society (109) respectively show marked difference between our 14 included countries. Only two countries (Sweden and Canada) ranked highly in both assessments. Such factors are likely to influence care-seeking behavior, shaping the relevance of our findings.

Additionally, while our sample includes a diverse group of marginalised communities with several complex social risk factors, only two (55, 81) of the 51 studies consider the idea of intersectionality. It has now been well-established that individuals with multiple marginalised identities face compounded barriers to care access and utilizations (110), and future research is crucial to understanding these unique intersections of disadvantage.

4.3 Strengths, limitations, and future directions

A key strength of our review is the use of meta-ethnography, allowing us to build on themes from individual studies—all of which were of moderate-to-high quality—and identify gaps in existing theory. Notably, we highlight the multi-generational impact of immigration on care-seeking as a missing component of the Candidacy Framework, supporting its expansion. Our focus on women’s care-seeking excluded perspectives of fathers, partners, non-gestational parents, providers, and policymakers. While we observed similarities across groups and countries, we may have missed group-specific or system-level differences, which we plan to explore further. A planned sub-group analysis on the pandemic’s impact was not possible due to limited studies; questions remain on how service reconfigurations and misinformation shaped care-seeking during this time and will be explored by is in future qualitative work. Future research should also examine the roles of families, professionals, and health systems, and empirically validate the proposed construct of intercultural dissonance.

5 Conclusion

In HICs, maternity care-seeking is a joint responsibility between service-users and service-providers. As such, interventions to remove barriers to care-seeking should be co-produced through collaborative means between stakeholders. Efforts to improve utilization of, and engagement with, antenatal care services should prioritize alleviating system-level barriers. We suggest an expansion of the Candidacy Framework to include two further dimensions which reflect the multigenerational effect of migration on care experience and the often hostile and precarious bureaucratic environment in which women find themselves when attempting to seek maternity care.

Data availability statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/Supplementary material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Author contributions

TD: Methodology, Writing – review & editing, Formal analysis, Software, Writing – original draft, Investigation, Conceptualization, Visualization, Project administration, Validation, Data curation, Funding acquisition, Resources. HR-J: Supervision, Formal analysis, Investigation, Data curation, Writing – review & editing, Validation, Visualization, Resources, Conceptualization. GH: Software, Formal analysis, Writing – review & editing. YB: Validation, Writing – review & editing. MP: Validation, Writing – review & editing. SS: Writing – review & editing, Conceptualization, Validation, Methodology, Investigation, Supervision, Resources. LM: Supervision, Resources, Writing – review & editing, Investigation, Conceptualization, Validation.

Funding

The author(s) declare that financial support was received for the research and/or publication of this article. Tisha Dasgupta is in receipt of an Economic and Social Research Council [ESRC] doctoral training fellowship from the London Interdisciplinary Social Science Doctoral Training Partnership [LISS DTP], (ES/P000703/1). Hannah Rayment-Jones is funded by a NIHR Advanced Fellowship (NIHR 303183).

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The authors declare that Gen AI was used in the creation of this manuscript. During the preparation of this work the author(s) used ChatGPT in order to make the manuscript more concise and reduce words. After using this tool/service, the author(s) reviewed and edited the content as needed and take(s) full responsibility for the content of the publication.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Supplementary material

The Supplementary material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fpubh.2025.1683740/full#supplementary-material

Abbreviations

UK, United Kingdom; HIC, High-income country; LMIC, Low- and middle-income country; HCP, Healthcare professional; SES, Socioeconomic status; USA, United States of America; WHO, World Health Organization; SDoH, Social determinants of Health; CASP, Critical Appraisal Skills Program; IPV, Intimate partner violence.

References

1. World Health Organization. WHO recommendations on antenatal care for a positive pregnancy experience. Geneva: World Health Organization (2016).

2. Tunçalp, Ӧ, Pena-Rosas, JP, Lawrie, T, Bucagu, M, Oladapo, OT, Portela, A, et al. WHO recommendations on antenatal care for a positive pregnancy experience—going beyond survival. BJOG. (2017) 124:860–2. doi: 10.1111/1471-0528.14599

3. Stacey, T, Thompson, JMD, Mitchell, EA, Zuccollo, JM, Ekeroma, AJ, and McCowan, LME. Antenatal care, identification of suboptimal fetal growth and risk of late stillbirth: findings from the Auckland stillbirth study. Aust N Z J Obstet Gynaecol. (2012) 52:242–7. doi: 10.1111/j.1479-828X.2011.01406.x

4. Kuhnt, J, and Vollmer, S. Antenatal care services and its implications for vital and health outcomes of children: evidence from 193 surveys in 69 low-income and middle-income countries. BMJ Open. (2017) 7:e017122. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2017-017122

5. Sarikhani, Y, Najibi, SM, and Razavi, Z. Key barriers to the provision and utilization of maternal health services in low-and lower-middle-income countries; a scoping review. BMC Womens Health. (2024) 24:325. doi: 10.1186/s12905-024-03177-x

6. Downe, S, Finlayson, K, Tunçalp, Ö, and Gülmezoglu, AM. Provision and uptake of routine antenatal services: a qualitative evidence synthesis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. (2019) 2019. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD012392.pub2

7. Mamrath, S, Greenfield, M, Turienzo, CF, Fallon, V, and Silverio, SA. Experiences of postpartum anxiety during the COVID-19 pandemic: a mixed methods study and demographic analysis. PLoS One. (2024) 19:e0297454. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0297454

8. Redshaw, M, and Heikkila, K. Delivered with care: Delivered with care: A national survey of women’s experience of maternity care 2010. Oxford, England: University of Oxford (2010).

9. Escañuela Sánchez, T, Linehan, L, O’Donoghue, K, Byrne, M, and Meaney, S. Facilitators and barriers to seeking and engaging with antenatal care in high-income countries: a meta-synthesis of qualitative research. Health Soc Care Community. (2022) 30:e3810–28. doi: 10.1111/hsc.14072

10. Peterson, L, Bridle, L, Dasgupta, T, Easter, A, Ghobrial, S, Ishlek, I, et al. Oscillating autonomy: a grounded theory study of women’s experiences of COVID-19 infection during pregnancy, labour and birth, and the early postnatal period. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. (2024) 24:511. doi: 10.1186/s12884-024-06685-8

11. Jackson, L, Greenfield, M, Payne, E, Burgess, K, Oza, M, Storey, C, et al. A consensus statement on perinatal mental health during the COVID-19 pandemic and recommendations for post-pandemic recovery and re-build. Front Glob Womens Health. (2024) 21:1347388. doi: 10.3389/fgwh.2024.1347388

12. Silverio, SA, Harris, EJ, Jackson, L, Fallon, V, Easter, A, von Dadelszen, P, et al. Freedom for some, but not for mum: the reproductive injustice associated with pandemic ‘freedom day’ for perinatal women in the United Kingdom. Front Public Health. (2024) 12:1389702. doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2024.1389702

13. Montgomery, E, De Backer, K, Easter, A, Magee, LA, Sandall, J, and Silverio, SA. Navigating uncertainty alone: a grounded theory analysis of women’s psycho-social experiences of pregnancy and childbirth during the COVID-19 pandemic in London. Women Birth. (2023) 36:e106–17. doi: 10.1016/j.wombi.2022.05.002

14. Jardine, J, Relph, S, Magee, LA, von Dadelszen, P, Morris, E, Ross-Davie, M, et al. Maternity services in the UK during the coronavirus disease 2019 pandemic: a national survey of modifications to standard care. BJOG. (2021) 128:880–9. doi: 10.1111/1471-0528.16547

15. Bridle, L, Walton, L, van der Vord, T, Adebayo, O, Hall, S, Finlayson, E, et al. Supporting perinatal mental health and wellbeing during COVID-19. Int J Environ Res Public Health. (2022) 19:1777. doi: 10.3390/ijerph19031777

16. Dasgupta, T, Horgan, G, Peterson, L, Mistry, HD, Balls, E, Wilson, M, et al. Women’s experiences of maternity care in the United Kingdom during the COVID-19 pandemic: a follow-up systematic review and qualitative evidence synthesis. Women Birth. (2024) 37:101588. doi: 10.1016/j.wombi.2024.02.004

17. Jackson, L, De Pascalis, L, Harrold, JA, Fallon, V, and Silverio, SA. Postpartum women’s experiences of social and healthcare professional support during the COVID-19 pandemic: a recurrent cross-sectional thematic analysis. Women Birth. (2022) 35:511–20. doi: 10.1016/j.wombi.2021.10.002

18. Silverio, SA, De Backer, K, Easter, A, von Dadelszen, P, Magee, LA, and Sandall, J. Women’s experiences of maternity service reconfiguration during the COVID-19 pandemic: a qualitative investigation. Midwifery. (2021) 102:103116. doi: 10.1016/j.midw.2021.103116

19. Dixon-Woods, M, Cavers, D, Agarwal, S, Annandale, E, Arthur, A, Harvey, J, et al. Conducting a critical interpretive synthesis of the literature on access to healthcare by vulnerable groups. BMC Med Res Methodol. (2006) 6:1–13. doi: 10.1186/1471-2288-6-35

20. Downe, S, Finlayson, K, Walsh, D, and Lavender, T. ‘Weighing up and balancing out’: a meta-synthesis of barriers to antenatal care for marginalised women in high-income countries. BJOG. (2009) 116:518–29. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-0528.2008.02067.x

21. Tookey, S, Renzi, C, Waller, J, Von Wagner, C, and Whitaker, KL. Using the candidacy framework to understand how doctor-patient interactions influence perceived eligibility to seek help for cancer alarm symptoms: a qualitative interview study. BMC Health Serv Res. (2018) 18:937. doi: 10.1186/s12913-018-3730-5

22. Koehn, S. Negotiating candidacy: ethnic minority seniors’ access to care. Ageing Soc. (2009) 29:585–608. doi: 10.1017/S0144686X08007952

23. Mackenzie, M, Conway, E, Hastings, A, Munro, M, and O’Donnell, C. Is ‘candidacy’ a useful concept for understanding journeys through public services? A critical interpretive literature synthesis. Soc Policy Adm. (2013) 47:806–25. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9515.2012.00864.x

24. Liberati, E, Richards, N, Parker, J, Willars, J, Scott, D, Boydell, N, et al. Qualitative study of candidacy and access to secondary mental health services during the COVID-19 pandemic. Soc Sci Med. (2022) 296:114711. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2022.114711

25. Rayment-Jones, H, Silverio, SA, Harris, J, Harden, A, and Sandall, J. Project 20: midwives’ insight into continuity of care models for women with social risk factors: what works, for whom, in what circumstances, and how. Midwifery. (2020) 84:102654. doi: 10.1016/j.midw.2020.102654

26. Hinton, L, Kuberska, K, Dakin, F, Boydell, N, Martin, G, Draycott, T, et al. A qualitative study of the dynamics of access to remote antenatal care through the lens of candidacy. J Health Serv Res Policy. (2023) 28:222–32. doi: 10.1177/13558196231165361

27. Page, MJ, McKenzie, JE, Bossuyt, PM, Boutron, I, Hoffmann, TC, Mulrow, CD, et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: an updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. Syst Rev. (2021) 10:n71. doi: 10.1136/bmj.n71

28. LISS DTP. Tisha Dasgupta - LISS DTP. Available online at: https://liss-dtp.ac.uk/students/tisha-dasgupta/ (Accessed Jan 17, 2025).

29. Ouzzani, M, Hammady, H, Fedorowicz, Z, and Elmagarmid, A. Rayyan—a web and mobile app for systematic reviews. Syst Rev. (2016) 5:210. doi: 10.1186/s13643-016-0384-4

30. Critical Appraisal Skills Programme. CASP Qualitative Checklist. (2018). Available online at: https://casp-uk.net/checklists/casp-qualitative-studies-checklist-fillable.pdf (Accessed May 22, 2024).

32. Sattar, R, Lawton, R, Panagioti, M, and Johnson, J. Meta-ethnography in healthcare research: a guide to using a meta-ethnographic approach for literature synthesis. BMC Health Serv Res. (2021) 21:50. doi: 10.1186/s12913-020-06049-w

33. Britten, N, Campbell, R, Pope, C, Donovan, J, Morgan, M, and Pill, R. Using meta ethnography to synthesise qualitative research: a worked example. J Health Serv Res Policy. (2002) 7:209–15. doi: 10.1258/135581902320432732

34. Malpass, A, Shaw, A, Sharp, D, Walter, F, Feder, G, Ridd, M, et al. “Medication career” or “moral career”? The two sides of managing antidepressants: a meta-ethnography of patients’ experience of antidepressants. Soc Sci Med. (2009) 68:154–68. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2008.09.068

35. Barkensjö, M, Greenbrook, JTV, Rosenlundh, J, Ascher, H, and Elden, H. The need for trust and safety inducing encounters: a qualitative exploration of women’s experiences of seeking perinatal care when living as undocumented migrants in Sweden. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 18:217. doi: 10.1186/s12884-018-1851-9

36. Tesfalul, MA, Feuer, SK, Castillo, E, Coleman-Phox, K, O’Leary, A, and Kuppermann, M. Patient and provider perspectives on preterm birth risk assessment and communication. Patient Educ Couns. (2021) 104:2814–23. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2021.03.038

37. Ayers, BL, Purvis, RS, Bing, WI, Rubon-Chutaro, J, Hawley, NL, Delafield, R, et al. Structural and socio-cultural barriers to prenatal care in a US Marshallese community. Matern Child Health J. (2018) 22:1067–76. doi: 10.1007/s10995-018-2490-5

38. McLemore, MR, Altman, MR, Cooper, N, Williams, S, Rand, L, and Franck, L. Health care experiences of pregnant, birthing and postnatal women of color at risk for preterm birth. Soc Sci Med. (2018) 1:127–35. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2018.02.013

39. Vang, ZM, Gagnon, R, Lee, T, Jimenez, V, Navickas, A, Pelletier, J, et al. Interactions between indigenous women awaiting childbirth away from home and their southern, non-indigenous health care providers (2018) 28:1858–70. doi: 10.1177/1049732318792500,

40. Holten, L, Hollander, M, and De Miranda, E. When the hospital is no longer an option: a multiple case study of defining moments for women choosing home birth in high-risk pregnancies in the Netherlands. Qual Health Res. (2018) 28:1883–96. doi: 10.1177/1049732318791535

41. Origlia Ikhilor, P, Hasenberg, G, Kurth, E, Asefaw, F, Pehlke-Milde, J, and Cignacco, E. Communication barriers in maternity care of allophone migrants: experiences of women, healthcare professionals, and intercultural interpreters. J Adv Nurs. (2019) 75:2200–10. doi: 10.1111/jan.14093

42. Sami, J, Lötscher, KCQ, Eperon, I, Gonik, L, De Tejada, BM, Epiney, M, et al. Giving birth in Switzerland: a qualitative study exploring migrant women’s experiences during pregnancy and childbirth in Geneva and Zurich using focus groups. Reprod Health. (2019) 16:112. doi: 10.1186/s12978-019-0771-0

43. Spangaro, J, Koziol-McLain, J, Rutherford, A, and Zwi, AB. “Made me feel connected”: a qualitative comparative analysis of intimate partner violence routine screening pathways to impact. Violence Women. (2019) 26:334–58. doi: 10.1177/1077801219830250

44. Holden, G, Corter, AL, Hatters-Friedman, S, and Soosay, I. Brief Report. A qualitative study of maternal mental health services in New Zealand: perspectives of Māori and Pacific mothers and midwives. Asia Pacific Psychiatry. (2019) 12:e12369. doi: 10.1111/appy.12369

45. Johnsen, H, Christensen, U, Juhl, M, and Villadsen, SF. Contextual factors influencing the MAMAACT intervention: a qualitative study of non-Western immigrant women’s response to potential pregnancy complications in everyday life. Int J Environ Res Public Health. (2020) 17:1040. doi: 10.3390/ijerph17031040

46. Decker, MJ, Pineda, N, Gutmann-Gonzalez, A, and Brindis, CD. Youth-centered maternity care: a binational qualitative comparison of the experiences and perspectives of Latina adolescents and healthcare providers. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. (2021) 21:349. doi: 10.1186/s12884-021-03831-4

47. Bains, S, Skråning, S, Sundby, J, Vangen, S, Sørbye, IK, and Lindskog, BV. Challenges and barriers to optimal maternity care for recently migrated women - a mixed-method study in Norway. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. (2021) 21:1–14. doi: 10.1186/s12884-021-04131-7

48. Hjelm, K, Bard, K, and Apelqvist, J. A qualitative study of developing beliefs about health, illness and healthcare in migrant African women with gestational diabetes living in Sweden. BMC Womens Health. (2018) 18:34. doi: 10.1186/s12905-018-0518-z

49. Nottingham-Jones, J, Simmonds, JG, and Snell, TL. First-time mothers’ experiences of preparing for childbirth at advanced maternal age. Midwifery. (2020) 1:102558. doi: 10.1016/j.midw.2019.102558

50. Utne, R, Antrobus-Johannessen, CL, Aasheim, V, Aaseskjær, K, and Vik, ES. Somali women’s experiences of antenatal care: a qualitative interview study. Midwifery. (2020) 83:102656. doi: 10.1016/j.midw.2020.102656

51. Bitar, D, and Oscarsson, M. Arabic-speaking women’s experiences of communication at antenatal care in Sweden using a tablet application—part of development and feasibility study. Midwifery. (2020) 84:102660. doi: 10.1016/j.midw.2020.102660

52. Oza-Frank, R, Conrey, E, Bouchard, J, Shellhaas, C, and Weber, MB. Healthcare experiences of low-income women with prior gestational diabetes. Matern Child Health J. (2018) 22:1059–66. doi: 10.1007/s10995-018-2489-y

53. Byatt, N, Straus, J, Stopa, A, Biebel, K, Mittal, L, and Simas, TAM. Massachusetts child psychiatry access program for moms: utilization and quality assessment. Obstet Gynecol. (2018) 132:345–53. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0000000000002688

54. Drago, MJ, Guillén, U, Schiaratura, M, Batza, J, Zygmunt, A, Mowes, A, et al. Constructing a culturally informed Spanish decision-aid to counsel Latino parents facing imminent extreme premature delivery. Matern Child Health J. (2018) 22:950–7. doi: 10.1007/s10995-018-2471-8

55. Daoud, N, Abu-Hamad, S, Berger-Polsky, A, Davidovitch, N, and Orshalimy, S. Mechanisms for racial separation and inequitable maternal care in hospital maternity wards. Soc Sci Med. (2022) 292:114551. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2021.114551

56. Wah, YYE, McGill, M, Wong, J, Ross, GP, Harding, AJ, and Krass, I. Self-management of gestational diabetes among Chinese migrants: a qualitative study. Women Birth. (2019) 32:e17–23. doi: 10.1016/j.wombi.2018.03.001

57. Farewell, CV, Jewell, J, Walls, J, and Leiferman, JA. A mixed-methods pilot study of perinatal risk and resilience during COVID-19. J Prim Care Community Health. (2020) 11:44074. doi: 10.1177/2150132720944074

58. Savory, NA, Hannigan, B, and Sanders, J. Women’s experience of mild to moderate mental health problems during pregnancy, and barriers to receiving support. Midwifery. (2022) 108:103276. doi: 10.1016/j.midw.2022.103276

59. Alanazy, W, Rance, J, and Brown, A. Exploring maternal and health professional beliefs about the factors that affect whether women in Saudi Arabia attend antenatal care clinic appointments. Midwifery. (2019) 76:36–44. doi: 10.1016/j.midw.2019.05.012

60. Henry, J, Beruf, C, and Fischer, T. Access to health Care for Pregnant Arabic-Speaking Refugee Women and Mothers in Germany. Qual Health Res. (2019) 30:437–47. doi: 10.1177/1049732319873620

61. Barkin, JL, Bloch, JR, Smith, KER, Telliard, SN, McGreal, A, Sikes, C, et al. Knowledge of and attitudes toward perinatal home visiting in women with high-risk pregnancies. J Midwifery Womens Health. (2021) 66:227–32. doi: 10.1111/jmwh.13204

62. Frederiksen, MS, Schmied, V, and Overgaard, C. Living with fear: experiences of Danish parents in vulnerable positions during pregnancy and in the postnatal period. Qual Health Res. (2021) 31:564–77. doi: 10.1177/1049732320978206

63. Frederiksen, MS, Schmied, V, and Overgaard, C. Supportive encounters during pregnancy and the postnatal period: an ethnographic study of care experiences of parents in a vulnerable position. J Clin Nurs. (2021) 30:2386–98. doi: 10.1111/jocn.15778

64. Reid, CN, Fryer, K, Cabral, N, and Marshall, J. Health care system barriers and facilitators to early prenatal care among diverse women in Florida. Birth. (2021) 48:416–27. doi: 10.1111/birt.12551

65. Fontein Kuipers, YJ, and Mestdagh, E. The experiential knowledge of migrant women about vulnerability during pregnancy: a woman-centred mixed-methods study. Women Birth. (2022) 35:70–9. doi: 10.1016/j.wombi.2021.03.004

66. Mule, V, Reilly, NM, Schmied, V, Kingston, D, and Austin, MPV. Why do some pregnant women not fully disclose at comprehensive psychosocial assessment with their midwife? Women Birth. (2022) 35:80–6. doi: 10.1016/j.wombi.2021.03.001

67. McClellan, C, and Madler, B. Lived experiences of Mongolian immigrant women seeking perinatal care in the United States. J Transcult Nurs. (2022) 33:594–602. doi: 10.1177/10436596221091689

68. Njenga, A. Somali refugee women’s experiences and perceptions of Western health care. J Transcul Nurs. (2022) 34:8–13. doi: 10.1177/10436596221125893

69. Mehrara, L, Olaug Gjernes, TK, and Young, S. Immigrant women’s experiences with Norwegian maternal health services: implications for policy and practice. Int J Qual Stud Health Wellbeing. (2022) 17:2066256. doi: 10.1080/17482631.2022.2066256

70. Goodwin, L, Hunter, B, and Jones, A. The midwife–woman relationship in a South Wales community: experiences of midwives and migrant Pakistani women in early pregnancy. Health Expect. (2018) 21:347–57. doi: 10.1111/hex.12629

71. Wilson, R, Paterson, P, and Larson, HJ. Strategies to improve maternal vaccination acceptance. BMC Public Health. (2019) 19:342. doi: 10.1186/s12889-019-6655-y

72. Naylor Smith, J, Taylor, B, Shaw, K, Hewison, A, and Kenyon, S. “I didn’t think you were allowed that, they didn’t mention that.” a qualitative study exploring women’s perceptions of home birth. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. (2018) 18:105. doi: 10.1186/s12884-018-1733-1

73. Husain, F, Powys, VR, White, E, Jones, R, Goldsmith, LP, Heath, PT, et al. COVID-19 vaccination uptake in 441 socially and ethnically diverse pregnant women. PLoS One. (2022) 17:e0271834. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0271834

74. Stacey, T, Haith-Cooper, M, Almas, N, and Kenyon, C. An exploration of migrant women’s perceptions of public health messages to reduce stillbirth in the UK: a qualitative study. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. (2021) 21:394. doi: 10.1186/s12884-021-03879-2

75. Gong, Q, and Bharj, K. A qualitative study of the utilisation of digital resources in pregnant Chinese migrant women’s maternity care in northern England. Midwifery. (2022) 115:103493. doi: 10.1016/j.midw.2022.103493

76. Balaam, MC, and Thomson, G. Building capacity and wellbeing in vulnerable/marginalised mothers: a qualitative study. Women Birth. (2018) 31:e341–7. doi: 10.1016/j.wombi.2017.12.010

77. Hall, J, Hundley, V, Collins, B, and Ireland, J. Dignity and respect during pregnancy and childbirth: a survey of the experience of disabled women. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. (2018) 18:328. doi: 10.1186/s12884-018-1950-7

78. Gordon, ACT, Burr, J, Lehane, D, and Mitchell, C. Influence of past trauma and health interactions on homeless women’s views of perinatal care: a qualitative study. Br J Gen Pract. (2019) 69:e760. doi: 10.3399/bjgp19X705557

79. McLeish, J, and Redshaw, M. Maternity experiences of mothers with multiple disadvantages in England: a qualitative study. Women Birth. (2019) 32:178–84. doi: 10.1016/j.wombi.2018.05.009

80. George, EK, Dominique, S, Irie, W, and Edmonds, JK. “It’s my home away from home:” a hermeneutic phenomenological study exploring decision-making experiences of choosing a freestanding birth Centre for perinatal care. Midwifery. (2024) 139:104164. doi: 10.1016/j.midw.2024.104164

81. Parker, G, Miller, S, Ker, A, Baddock, S, Kerekere, E, and Veale, J. “Let all identities bloom, just let them bloom”: advancing trans-inclusive perinatal care through intersectional analysis. Qual Health Res. (2025) 35:403–17. doi: 10.1177/10497323241309590

82. Faulks, F, Shafiei, T, Mogren, I, and Edvardsson, K. “It’s just too far…”: a qualitative exploration of the barriers and enablers to accessing perinatal care for rural Australian women. Women Birth. (2024) 37:101809. doi: 10.1016/j.wombi.2024.101809

83. Nechaeva, E, Kharkova, O, Postoev, V, Grjibovski, AM, Darj, E, and Odland, JØ. Awareness of postpartum depression among midwives and pregnant women in Arkhangelsk, Arctic Russia. Glob Health Action. (2024) 17:2354008. doi: 10.1080/16549716.2024.2354008

84. Pierce, P, Whitten, M, and Hillman, S. The impact of digital healthcare on vulnerable pregnant women: a review of the use of the MyCare app in the maternity department at a Central London tertiary unit. Front Digit Health. (2023) 5:1155708. doi: 10.3389/fdgth.2023.1155708

85. Yuill, C, Sinesi, A, Meades, R, Williams, LR, Delicate, A, Cheyne, H, et al. Women’s experiences and views of routine assessment for anxiety in pregnancy and after birth: a qualitative study. Br J Health Psychol. (2024) 29:958–71. doi: 10.1111/bjhp.12740

86. Rules, TA. Paper, status migrants and precarious bureaucracy in contemporary Italy. Redwood City, CA: Stanford University Press (2018).

87. Mackian, S, Bedri, N, and Lovel, H. Up the garden path and over the edge: where might health-seeking behaviour take us? Health Policy Plan. (2004) 19:137–46. doi: 10.1093/heapol/czh017

88. Sharma, E, Tseng, PC, Harden, A, Li, L, and Puthussery, S. Ethnic minority women’s experiences of accessing antenatal care in high income European countries: a systematic review. BMC Health Serv Res. (2023) 23:612. doi: 10.1186/s12913-023-09536-y

89. Higginbottom, G, Evans, C, Morgan, M, Bharj, K, Eldridge, J, and Hussain, B. Experience of and access to maternity care in the United Kingdom (UK) by immigrant women: A narrative synthesis systematic review. BMJ Open. (2019) 9:e029478. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2019-029478

90. Silverio, SA, Varman, N, Barry, Z, Khazaezadeh, N, Rajasingam, D, Magee, LA, et al. Inside the ‘imperfect mosaic’: minority ethnic women’s qualitative experiences of race and ethnicity during pregnancy, childbirth, and maternity care in the United Kingdom. BMC Public Health. (2023) 23:2555. doi: 10.1186/s12889-023-17505-7

91. Puthussery, S, Bayih, WA, Brown, H, and Aborigo, RA. Promoting a global culture of respectful maternity care. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. (2023) 23:798. doi: 10.1186/s12884-023-06118-y

92. Bohren, MA, Hunter, EC, Munthe-Kaas, HM, Souza, JP, Vogel, JP, and Gülmezoglu, AM. Facilitators and barriers to facility-based delivery in low- and middle-income countries: a qualitative evidence synthesis. Reprod Health. (2014) 11:71. doi: 10.1186/1742-4755-11-71

93. Glover, A, Holman, C, and Boise, P. Patient-centered respectful maternity care: a factor analysis contextualizing marginalized identities, trust, and informed choice. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. (2024) 24:267. doi: 10.1186/s12884-024-06491-2

94. Rayment-Jones, H, Dalrymple, K, Harris, JM, Harden, A, Parslow, E, Georgi, T, et al. Project20: maternity care mechanisms that improve access and engagement for women with social risk factors in the UK – a mixed-methods, realist evaluation. BMJ Open. (2023) 13:e064291. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2022-064291

95. Stanton, ME, Higgs, ES, and Koblinsky, M. Investigating financial incentives for maternal health: an introduction. J Health Popul Nutr. (2013) 31:S1.

96. Whitaker, KL, Macleod, U, Winstanley, K, Scott, SE, and Wardle, J. Help seeking for cancer ‘alarm’ symptoms: a qualitative interview study of primary care patients in the UK. Br J Gen Pract. (2015) 65:e96–e105. doi: 10.3399/bjgp15X683533

97. Richard, L, Furler, J, Densley, K, Haggerty, J, Russell, G, Levesque, JF, et al. Equity of access to primary healthcare for vulnerable populations: the IMPACT international online survey of innovations. Int J Equity Health. (2016) 15:64. doi: 10.1186/s12939-016-0351-7

98. McKnight, P, Goodwin, L, and Kenyon, S. A systematic review of asylum-seeking women’s views and experiences of UK maternity care. Midwifery. (2019) 77:16–23. doi: 10.1016/j.midw.2019.06.007

99. Brennan, N, Barnes, R, Calnan, M, Corrigan, O, Dieppe, P, and Entwistle, V. Trust in the health-care provider–patient relationship: a systematic mapping review of the evidence base. Int J Qual Health Care. (2013) 25:682–8. doi: 10.1093/intqhc/mzt063

100. Earnshaw, VA, and Quinn, DM. The impact of stigma in healthcare on people living with chronic illnesses (2011) 17:157–68. doi: 10.1177/1359105311414952,

101. Barry, CA, Stevenson, FA, Britten, N, Barber, N, and Bradley, CP. Giving voice to the lifeworld. More humane, more effective medical care? A qualitative study of doctor–patient communication in general practice. Soc Sci Med. (2001) 53:487–505. doi: 10.1016/s0277-9536(00)00351-8

102. Bridle, L, Bassett, S, and Silverio, SA. “We couldn’t talk to her”: a qualitative exploration of the experiences of UK midwives when navigating women’s care without language. Int J Hum Rights Healthc. (2021) 14:359–73. doi: 10.1108/IJHRH-10-2020-0089

103. Rayment-Jones, H, Harris, J, Harden, A, Silverio, SA, Turienzo, CF, and Sandall, J. Project20: interpreter services for pregnant women with social risk factors in England: what works, for whom, in what circumstances, and how? Int J Equity Health. (2021) 20:233. doi: 10.1186/s12939-021-01570-8

104. Khan, Z, Vowles, Z, Fernandez Turienzo, C, Barry, Z, Brigante, L, Downe, S, et al. Targeted health and social care interventions for women and infants who are disproportionately impacted by health inequalities in high-income countries: a systematic review. Int J Equity Health. (2023) 22:131. doi: 10.1186/s12939-023-01948-w

105. Wolynn, M. It didn’t start with you: How inherited family trauma shapes who we are and how to end the cycle. New York: Random House (2022).

106. Chase, LE, Cleveland, J, Beatson, J, and Rousseau, C. The gap between entitlement and access to healthcare: an analysis of “candidacy” in the help-seeking trajectories of asylum seekers in Montreal. Soc Sci Med. (2017) 182:52–9. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2017.03.038

107. Van der Boor, CF, and White, R. Barriers to accessing and negotiating mental health services in asylum seeking and refugee populations: the application of the candidacy framework. J Immigr Minor Health. (2019) 22:156–74. doi: 10.1007/s10903-019-00929-y

108. World Health Organization. Health Financing Progress Matrix. Geneva: World Health Organization. Available online at: https://www.who.int/teams/health-financing-and-economics/health-financing/diagnostics/health-financing-progress-matrix (Accessed Jun 13, 2025).

Keywords: health care-seeking, maternity care, high-income countries, women, health inequality, marginalized groups

Citation: Dasgupta T, Rayment-Jones H, Horgan G, Begum Y, Peter M, Silverio SA and Magee LA (2025) Understanding care-seeking of pregnant women from underserved groups: a systematic review and meta-ethnography. Front. Public Health. 13:1683740. doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2025.1683740

Edited by:

Jaime Miller, Northumbria University, United KingdomReviewed by:

Elena Neiterman, Faculty of Applied Health Sciences, University of Waterloo, CanadaStephen Okumu Ombere, Maseno University, Kenya

Copyright © 2025 Dasgupta, Rayment-Jones, Horgan, Begum, Peter, Silverio and Magee. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Tisha Dasgupta, dGlzaGEuZGFzZ3VwdGFAa2NsLmFjLnVr

†ORCID: Tisha Dasgupta, orcid.org/0000-0002-7874-9519

Hannah Rayment-Jones, orcid.org/0000-0002-3027-8025

Gillian Horgan, orcid.org/0009-0001-0827-0481

Yesmin Begum, orcid.org/0009-0009-2658-3471

Michelle Peter, orcid.org/0000-0002-4977-8708

Sergio A. Silverio, orcid.org/0000-0001-7177-3471

Laura A. Magee, orcid.org/0000-0002-1355-610X

Tisha Dasgupta

Tisha Dasgupta Hannah Rayment-Jones1†

Hannah Rayment-Jones1† Michelle Peter

Michelle Peter Sergio A. Silverio

Sergio A. Silverio Laura A. Magee

Laura A. Magee