- 1Department of Epidemiology and Community Health, College of Health and Human Services, UNC Charlotte, Charlotte, NC, United States

- 2Division of Infectious Diseases, Department of Medicine, UNC-Chapel Hill School of Medicine, Chapel Hill, NC, United States

- 3Center for AIDS Research, UNC-Chapel Hill, Chapel Hill, NC, United States

- 4Department of Health Behavior, Gillings School of Global Public Health, UNC-Chapel Hill, Chapel Hill, NC, United States

- 5Division of General Internal Medicine and Clinical Epidemiology, Department of Medicine, UNC-Chapel Hill School of Medicine, UNC-Chapel Hill, Chapel Hill, NC, United States

- 6Department of Psychology, College of Humanities and Social Sciences, North Carolina State University, Raleigh, NC, United States

- 7Violence Prevention Center, UNC Charlotte, Charlotte, NC, United States

Background: Members of Black sexual and gender minority (BSGM) groups in the Southern US experience disparities across all pillars of the HIV prevention continuum. Social network strategy (SNS) is an intervention that trains people with reasons to test for HIV to reach out to peers to increase HIV testing and may improve uptake of pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP). We conducted formative research to design an enhanced SNS to implement within partner services.

Methods: In 2022–2024, we conducted four focus groups among HIV public health services staff and 12 in-depth interviews with local health department officials, clinicians, and community-based organization leaders. In addition, we interviewed four BSGM community members who recently used prevention services (i.e., testing or PrEP). Focus groups and interviews were transcribed and iteratively coded. Themes included salient barriers and facilitators to HIV services and mapped to a modified socio-ecological model after analysis. Narratives from the four BSGM were integrated with the summary analyses from HIV service providers.

Results: Service providers and community members identified persistent barriers to HIV prevention services: (1) basic human needs for survival and (2) lack of compassion within the healthcare system. Inadequate living necessities (e.g., housing and transportation), education, mistrust, stigma, and discrimination limit HIV prevention service use. Conversely, wrap-around services, transparency, representation, and compassionate care facilitate service access.

Conclusion: Enhancing HIV prevention services for BSGM groups necessitates reducing healthcare access barriers and leveraging facilitators. Our findings informed an enhanced SNS intervention to increase HIV testing, prevention, and care linkage among BSGM in the Southern US.

Background

The ‘Ending the HIV Epidemic’ (EHE) US policy identified 57 priority jurisdictions, many in the US South, that account for more than 50% of all new HIV diagnoses in the US (1). Mecklenburg County, North Carolina (NC), and the neighboring state of South Carolina are two priority jurisdictions where interventions are necessary to reduce frequent HIV transmissions. Black sexual and gender minority (BSGM) communities, including men who have sex with men and transgender women, consistently face disproportionate and worsening health inequities (e.g., social stigma, health insurance coverage, and inadequate education), with the greatest number of new HIV diagnoses occurring within these groups (1–4). Such disparities across the HIV prevention continuum result in higher rates of HIV incidence and lower engagement in prevention services like pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) (5–7).

Additionally, BSGM face a constellation of challenges within their social networks, (e.g., social, sexual, and geographic proximity to networks with greater incidence of HIV) that contribute to the urgent need to increase PrEP utilization among BSGM priority areas in the US South (8–10). BSGM face significantly higher levels of multiple marginalization, social stigmas, and discrimination, which increase their vulnerability to HIV exposure compared to non-BSGM groups (11). Data from the 2014–2018 Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System examined the intersectionality of being Black in the US and identifying as a gender minority (such as transfeminine, transmasculine, or another gender-diverse identity). The findings revealed that BSGM are disproportionately affected by race and gender intersectionality, thus experience worsening forms of oppression (11). BSGM are more likely than cisgender Black individuals and gender minority white individuals to self-report recent injection drug use, exposure to sexually transmitted infections, history of sex work, condomless sex, and more than four sex partners yearly (11). Higher rates of HIV-related stigma have been reported in the US South, where social conservatism and stigmatizing faith beliefs persist (2, 12, 13). Stigma, medical mistrust, geographic accessibility, lack of health insurance, financial assistance programs, and insufficient HIV awareness are universal barriers to prevention and care engagement (4). Compared to other regions, Southern states report greater religiosity, lower levels of HIV-related public health funding, and fewer nondiscrimination protections for sexual and gender minorities (2, 14, 15). These factors contribute to heightened stigma, medical mistrust, and limited access to culturally competent care, further increasing HIV risk factors (16–18). Analyses of national survey data reveal that rural identity, which is disproportionately represented in the South, predicts less supportive attitudes toward LGBTQ people and policies; and peer-reviewed syntheses and Southern samples document persistently lower social acceptance and fewer protections in the South than in the Northeast or West (19, 20). These cultural and structural differences make the South a critical region for studying BSGM experiences of HIV prevention and care engagement.

Improving these systemic disparities is critical to reducing health disparities among BSGM (3). In addition, social capital within BSGM networks may impact the likelihood of HIV transmission by increasing awareness and acceptability of PrEP, especially among those who experience multiple forms of marginalization (3). Social network approaches for HIV prevention leverage existing network relationships and network structures to promote behavior changes (i.e., increased HIV testing and PrEP uptake) (21). Just as exposures or behaviors can cluster within networks, beneficial health information can also cluster in networks, promoting healthier behavioral norms (22).

The CDC’s Social Network Strategy (SNS) is an evidence-supported intervention designed to motivate individuals from disproportionately affected groups, such as BSGM, to test for HIV (23–26). SNS enlists people living with HIV or those with a greater chance of acquiring HIV to recruit peers for HIV testing based on relationships with shared social similarities (27). Demonstration projects have shown SNS to be effective in increasing HIV testing among BSGM, including in the US South (25, 28). The present study aims to build upon understandings of SNS by identifying lived experiences with HIV prevention services among BSGM communities and service providers. Public health professionals, advocates, and members of BSGM networks shared their experiences through focus groups and in-depth interviews, describing barriers and facilitators to HIV prevention services.

Methods

Design and setting

This cross-sectional qualitative study explored potential barriers and facilitators to HIV prevention services for BSGM from the perspective of two participant groups: leadership participants and BSGM community members. This study will report on barriers and facilitators to HIV service utilization to inform the development and implementation of enhanced Social Network Strategy (eSNS) in response to identified needs of BSGM in recent transmission networks. This methodical response aims to increase HIV service utilization in Charlotte, NC for BSGM. This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board (IRB) at the University of North Carolina Chapel Hill.

This study was guided by an interpretivist epistemology, which views knowledge as co-constructed through lived experience, relationship, and context rather than discovered as objective fact. We approached the research with the understanding that participants’ narratives reflect situated truths shaped by their intersecting identities as BSGM individuals living in the US South. Within this framework, meaning emerges through dialog, reflexivity, and embodied understanding, recognizing that experiences of trust, stigma, and compassion are both personal and socially produced. The research team engaged in ongoing reflexive practice to acknowledge how our identities, disciplines, and proximity to the work influenced interpretation. This stance allowed us to center BSGM participants’ meaning-making processes and to interpret their stories as expressions of resilience, survival, and care within systems that have historically marginalized them.

Our interdisciplinary team included public health professionals, physicians, and social scientists from UNC Chapel Hill and UNC Charlotte with diverse identities across race, gender, sexuality, age, and geography. Two team members identify as Black women, one of whom is Kenyan-born and has lived in the US South for nearly two decades; others identify as white, with one genderfluid and several queer or non-heterosexual members. While most team members are outsiders to the lived experiences of BSGM communities and to living with HIV, all share commitments to equity, compassion, and community-engaged research. We approached analysis reflexively, using paired coding across institutions, memoing, and regular discussion to examine how our positionalities shaped interpretation. Black and queer team members provided critical insight into intersectional stigma, helping redirect analysis toward structural accountability rather than individual deficit. None of the interviewers had prior personal relationships with participants. Throughout the study, reflexive dialog emphasized humility and an intent to center participants’ voices and lived expertise.

Data collection

Participants

We purposively recruited HIV leadership participants (i.e., public health professionals and advocates) to participate in in-depth interviews (IDIs) and focus groups discussions (FGDs). Participants were recruited through the investigators’ networks by email invitation to county health department leadership and local community-based organizations (CBO), and clinics. Additionally, we recruited BSGM community members (i.e., local community members in sexual contact with someone recently diagnosed with HIV, who received routine partner services like HIV testing) to participate in IDIs. Eligible participants were sent an electronic consent form to read and sign before participating. Leadership FGDs and IDIs were conducted from December 2022 to February 2023. BSGM community member IDIs were conducted from June 2023 to February 2024. FGDs and IDIs were conducted over Zoom by interviewers and audio recorded.

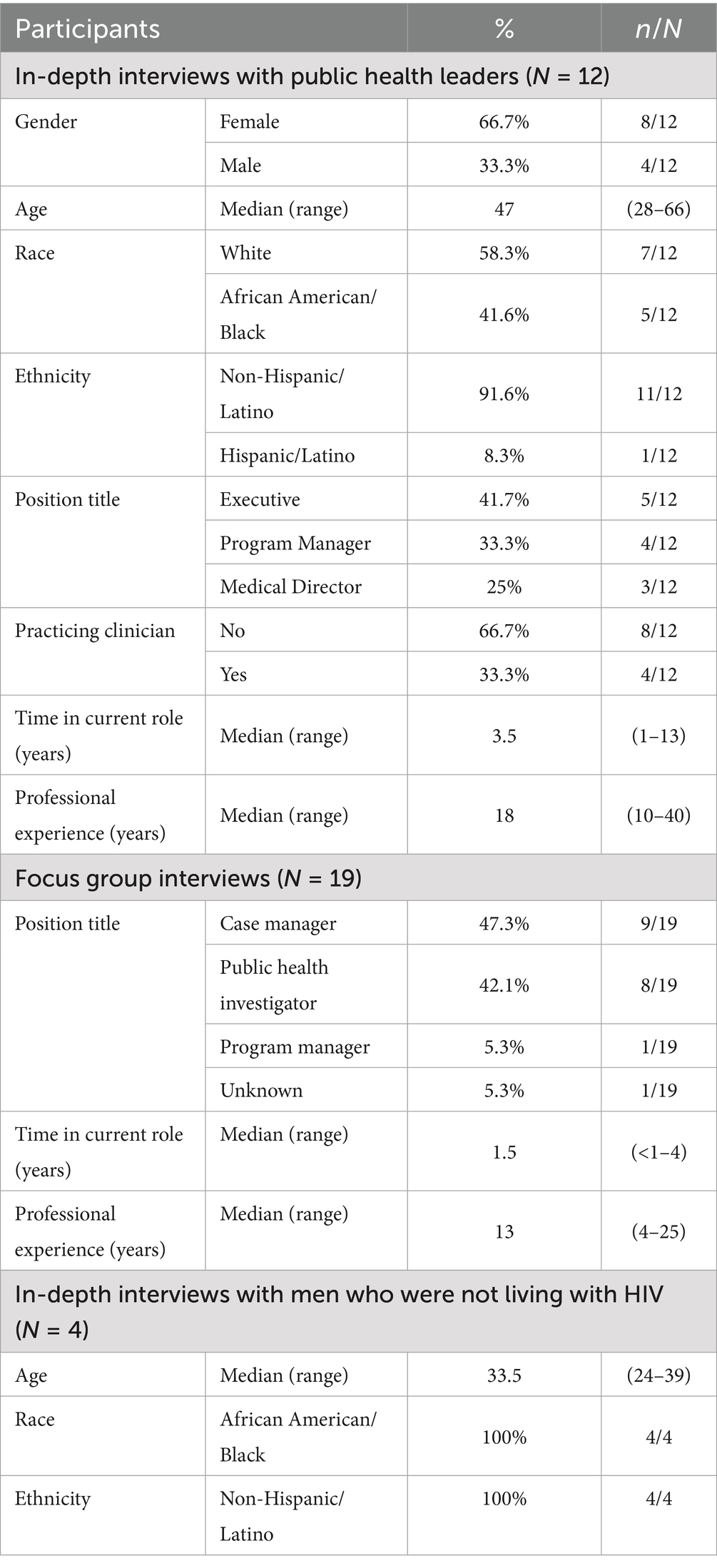

To ensure rigor, all interviewers reviewed the interview guides with the analysis team and practiced one mock interview with a member of the study team prior to conducting participant interviews. All IDI interviewers reviewed the interview guides with the analysis team and each one practiced one mock IDI with a member of the study team prior to conducting participant interviews. The two staff members who facilitated the FGDs have close to 20 and 10 years of experience in qualitative research respectively, including in data collection. Team members attended data collection trainings, including formal Qualitative Research trainings. The RESPOND-study specific training included first reading, aloud as a group, the study protocol, ICFs, data collection guides and data collection SOP, followed by conducting mock interviews. Two FGD mock interviews were conducted facilitated by the two most experienced qualitative researchers. Each team member also conducted one mock interview per IDI activity (i.e., Leadership IDIs and BSGM IDIs) (see Table 1).

Finally, IDI’s were conducted with leadership who do not necessarily perform partner services. FGDs were conducted with DIS and other folks involved in partner services who could possibly implement eSNS. Given the power differentials, IDIs with leadership were required. FGDs shared more common work responsibilities and experiences.

Leadership focus group discussions (FGDs)

Four FGDs, which each lasted approximately 120 min, were comprised of 4–6 leadership participants. In total, 19 staff from the local health department or CBOs who provide direct services to clients participated in FGDs 9 case managers, 8 HIV/STI disease intervention specialists (DIS)/public health field investigators, and 2 supervisors of partner services and/or linkage to care programs. Three of the four FGDs included at least one CBO staff member; participants’ time in their current roles ranged from less than 1 to 15 years. FGDs occurred during regular work hours and were not compensated. Interviewers practiced with two mock FGDs (i.e., one per facilitator) with one note-taker and at least three other team members.

Leadership and BSGM community member in-depth interviews (IDIs)

IDIs were conducted with 12 participants in leadership roles (5 public health departments, 4 CBOs, and 3 local clinics). Additionally, four BSGM community member IDIs were conducted with BSGM participants, all of whom were not living with HIV and identified as cisgender men. Interviews lasted approximately 60 min. Interview participants were given a $50 gift card for their time.

Interview guides

The IDI and FGD guides for leadership participants explored how they perceived BGSM groups’ engagement in local prevention services, barriers to access, and factors that could enhance engagement. Additionally, we aimed to understand effective methods for peer recruitment for HIV testing and PrEP engagement. IDI guides for BSGM community members were informed by theories of social networks and health, and we considered how social networks, shaped by socio-geographical factors, may influence behaviors and ultimately impact group and population outcomes (29). Additionally, we explored the influence of social and interpersonal behaviors, like social support, social influence, and access to various resources (30). Questions from the FGD and IDI guides are provided in Supplementary Tables S1, S2.

Data analysis

Audio-recorded FGDs and IDIs were transcribed using Landmark transcription services. Transcripts were initially coded using NVivo 1.7 by QSR International and then uploaded to Atlas. Ti to make coded data accessible to team members across institutions. Leadership data were collected from December 2022 to February 2023 (FGDs in December 2022 and IDIs through February 2023), while BSGM community member data were collected from June 2023 to February 2024, with data analysis conducted sequentially and formal analyses continuing through November 2024. Recruitment continued until data saturation was achieved, as indicated by the repetition of prior findings in transcripts and debriefs. FGDs were not stratified, and data were monitored using constant comparison during data collection to assess general and across-group saturation on core HIV prevention topics (i.e., testing and PrEP). Saturation for FGDs was determined through an emergent design, as participants consistently identified overlapping barriers and facilitators to eSNS across discussions. The team used Cohen’s Kappa scores to facilitate discussion to improve consensus of the codebook application. During coding meetings, the team discussed agreement rates below 80% to reconcile discrepancies in coding and make iterative modifications to the codebook to improve coding consistency. The final codebook included inductive and deductive codes and was applied to leadership FGD and IDI transcripts. Two separate groups of coders independently coded one FGD and one IDI transcript, performed inter-rater reliability checks in NVivo, and resolved any discrepancies before coding the remaining transcripts. For the BSGM community member IDI analysis, three pairs of coders applied inductive codes using a Modified Social Ecological Model (MSEM) iteratively.

Thematic analysis of IDIs and FGDs was guided by Braun and Clarke’s approach (31) through November of 2024. The coded data were reviewed in framework matrices characterizing perceptions about engagement in HIV prevention services among BSGM in Charlotte, NC and sorted into potential themes and sub-themes, discussed among the study team, and mapped onto each level of the MSEM Framework (e.g., individual, social network, community, and policy). Analysts grouped data coded with HIV prevention into potential barriers and facilitators, discussed emerging themes, and iteratively drafted analytical memos to enhance credibility. Results were refined and organized into two reports, one for each participant group. Subsequently, JSE and MCZ developed overarching themes across data sources to integrate results from providers with personal experiences shared by BSGM community members. We modified quotations for conciseness by removing pauses or repeated phrases.

Results

Participant demographics are displayed in Table 1. Among the 12 individuals from the IDIs with public health leaders, the majority were non-Hispanic (91.6%), White (58.3%), and Female (66.7%), with a median age of 47 years (range: 28–66). All four participants from the IDIs with men who were not living with HIV were non-Hispanic and African American/Black, with a median age of 33.5 years (range: 24–39).

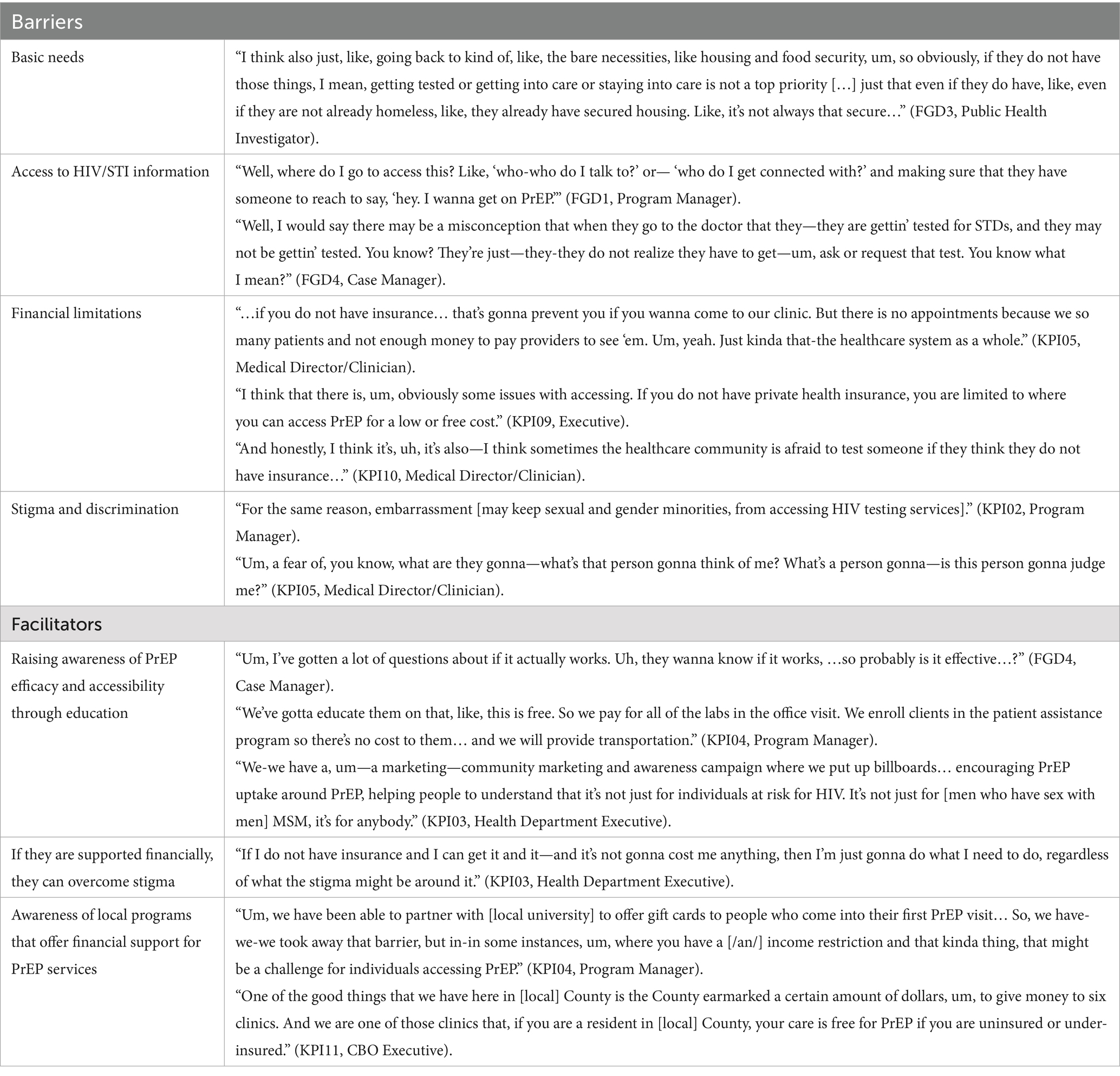

Overview of barriers to HIV prevention services from leadership participants

Leadership participants described HIV testing and PrEP access barriers for BSGM. Overarching barriers to HIV prevention services reported in both leadership FGDs and IDIs included: (1) lack of HIV prevention/PrEP knowledge; (2) confidentiality/disclosure concerns; (3) socio-economic obstacles; (4) HIV self “risk” perceptions; (5) PrEP inaccessibility; (6) experienced PrEP burden; (7) experienced stigma; (8) unclear PrEP campaign messaging (e.g., undefined access options); and (9) lack of provider trust. HIV testing results wait-time, PrEP efficacy, and PrEP modalities were other recurring barriers discussed in IDIs only. Additional barriers mentioned in the IDIs included mental health, fear of needles, lack of representation in health care facilities and staffing issues.

Overview of facilitators to HIV prevention services from leadership participants

Overarching facilitators reported in both leadership FGDs and IDIs included: (1) PrEP education; (2) PrEP accessibility; (3) PrEP modality options; (4) PrEP campaign messaging; and (5) trust in providers. Confidentiality/disclosure and socio-economic factors were other recurring themes reported in the IDIs only, while PrEP efficacy was reported in the FGDs only. Additional facilitators reported in the IDIs only included sexual health education and HIV self-testing/mobile testing, while fewer PrEP side effects were reported as an issue in the FGDs only.

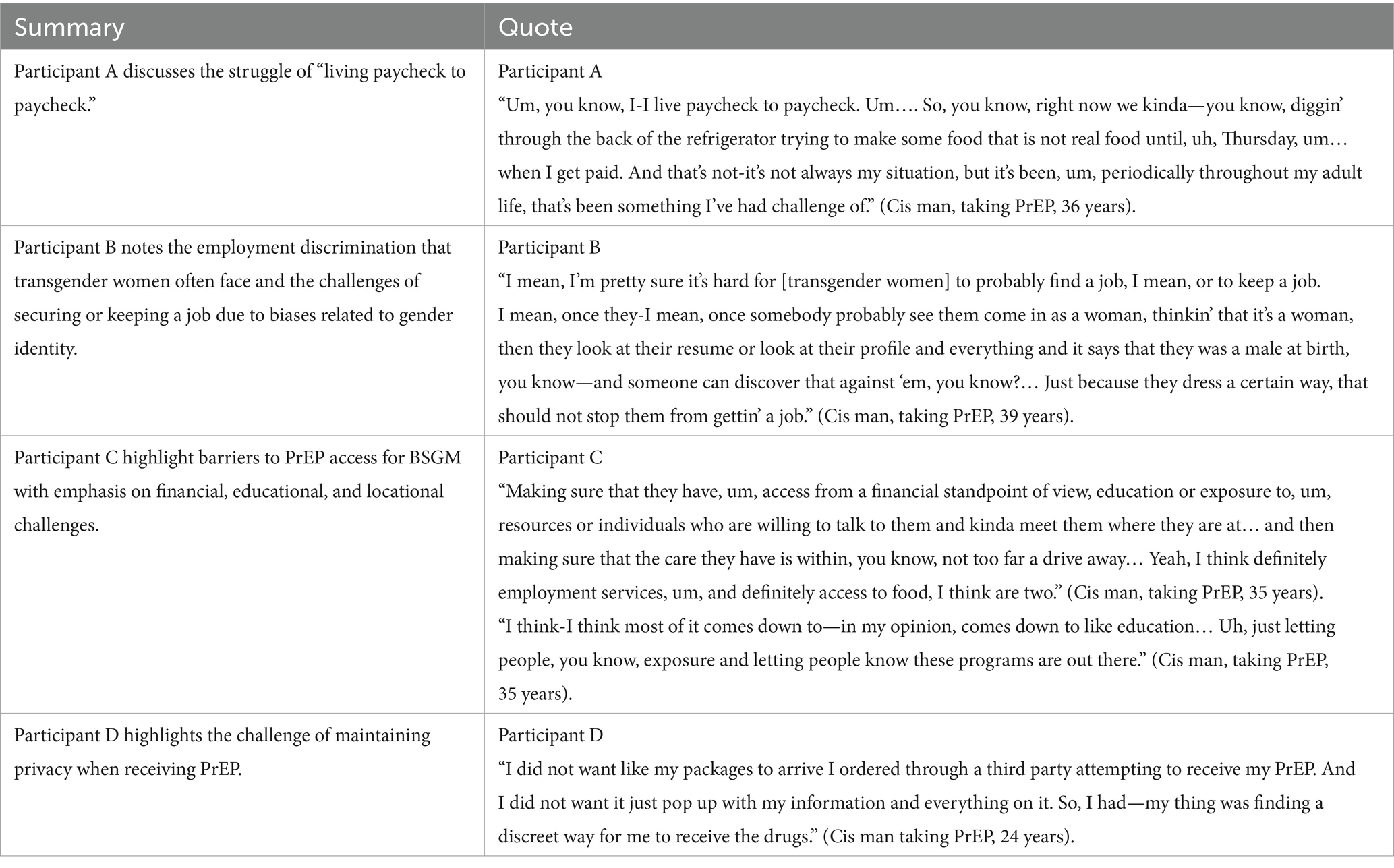

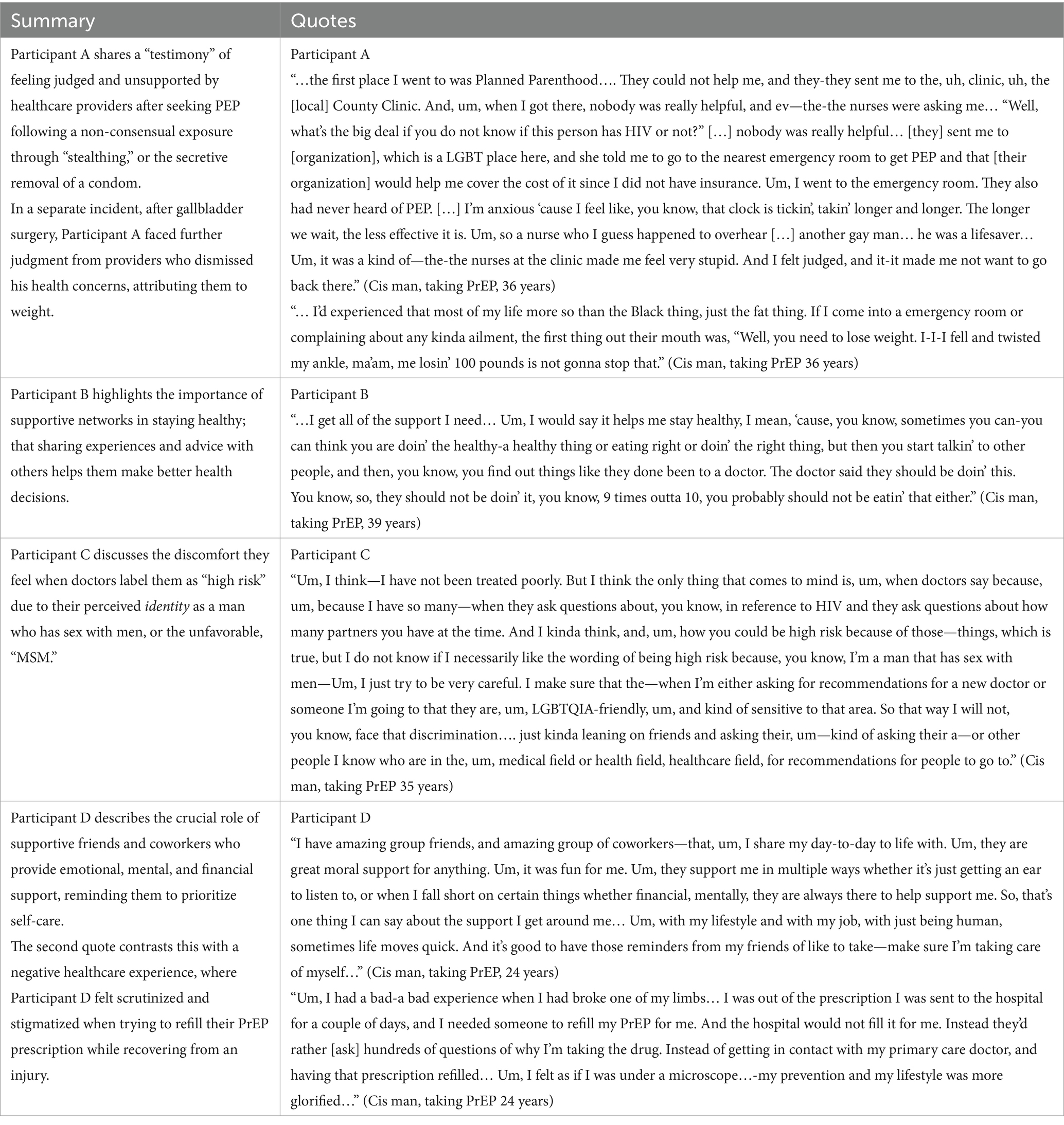

Using these overarching barriers and facilitators provided by leadership participants, we describe themes that were also highlighted and reinforced by stories shared by four BSGM community member interviews (three of whom were taking PrEP). Below, we define two central themes that collectively represent dominating barriers and facilitators described in leadership participant FGDs and IDIs, and BSGM community member IDIs: (1) How do We Navigate and Negotiate PrEP When the Options are “Survival” vs. “Health”? (see Tables 2, 3), and (2) Compassion from Others is the Antidote to Mistrust When We Do not Know Who to Believe (see Tables 4, 5).

Table 2. BSGM community member perspectives: Navigating and Negotiating PrEP: “Survival” vs. “Health.”

Table 4. BSGM community member perspectives: Compassion from Others is the Antidote to Mistrust When We Do Not Know Who to Believe.

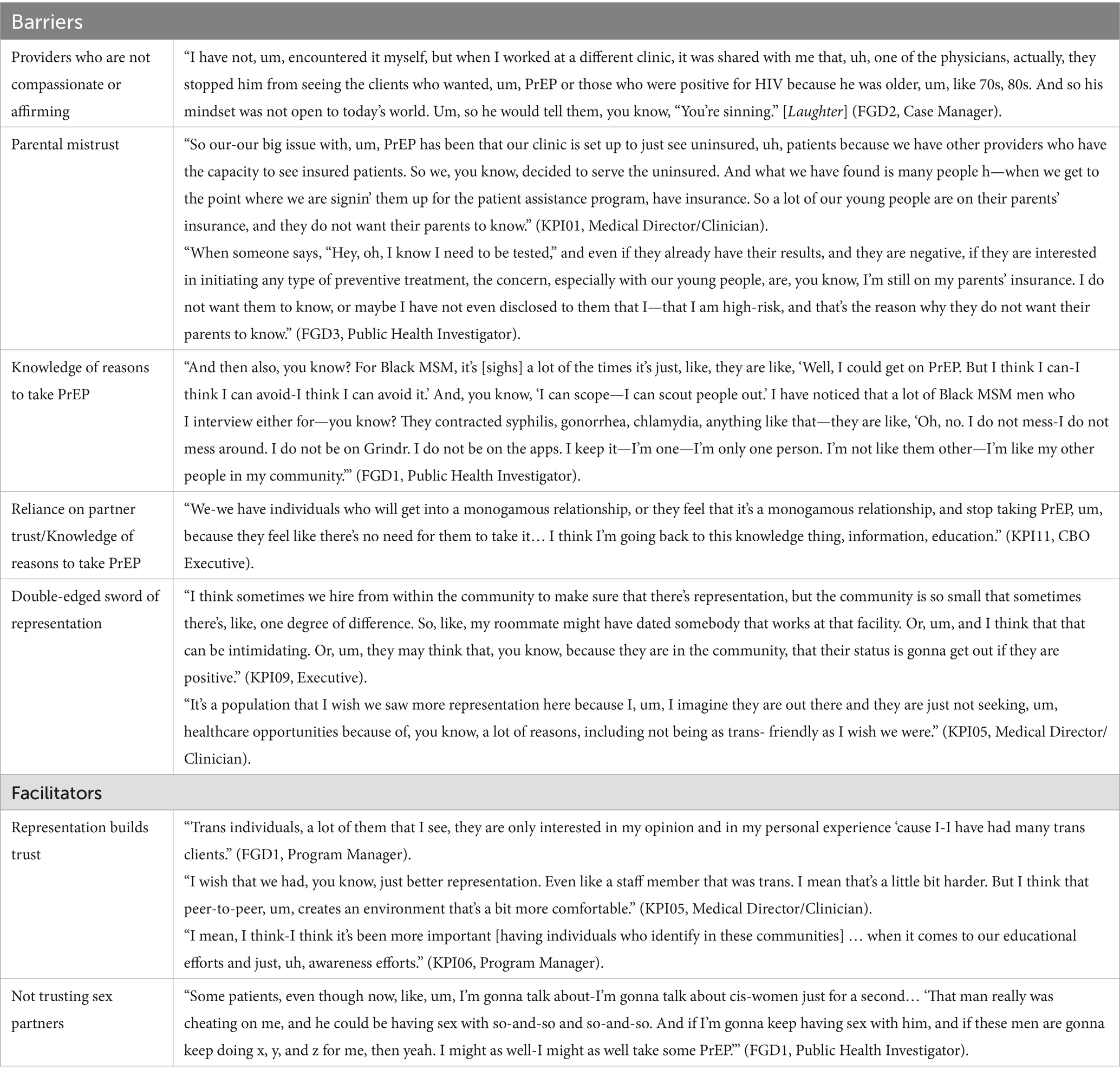

Table 5. Leadership perspectives: Compassion from Others is the Antidote to Mistrust When We Do Not Know Who to Believe.

Theme 1: Navigating and Negotiating PrEP: “Survival” vs. “Health”

Leadership participants and BSGM community members highlighted the tension between survival and accessing PrEP services for BSGM. “Survival” in this context refers to meeting basic survival needs, including employment, financial stability, general education, and access to food and transportation. Participants emphasized the need for comprehensive healthcare, which may include social services such as employment assistance and other economic mobility drivers like educational and medical resource provision. Once able to access prevention services, BSGM participants listed challenges such as lack of privacy and discretion when receiving PrEP medication and discomfort with identifiable medication packaging.

Leadership perspectives

The experiences of BSGM community members align closely with leadership perspectives, reinforcing the systemic and individual-level barriers that hinder access to HIV prevention services from both perspectives. Leadership participants also highlighted socioeconomic barriers such as housing instability, food insecurity, and education (i.e., lack of awareness regarding PrEP access). Both groups emphasized the importance of having readily available and clear information about PrEP programs to help overcome these barriers.

Theme 2: Compassion from Others is the Antidote to Mistrust When We Do Not Know Who to Believe

Participants across data sources described the complex role of trust in accessing HIV prevention services. BSGM community members revealed that trust in healthcare providers and within social networks may be essential for engaging with HIV prevention. Though not always related to seeking HIV services, BSGM described significant barriers resulting from negative experiences with healthcare providers, where biases and lack of understanding lead to poor treatment and a deep mistrust in the medical system. Supportive relationships with peers and providers, accurate information, and finding empathetic, lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, and queer plus (LGBTQ+) friendly healthcare providers were identified as crucial facilitators for overcoming these barriers.

Leadership perspectives

Leadership participants reflected similar concerns about trust and the dissemination of accurate information within BSGM communities. Trust in providers, particularly those with shared lived experiences, may enhance engagement with services. Conversely, a lack of trust or misinformation can lead to reduced uptake of preventive services. Participants emphasized the need for compassionate care and trustworthy relationships with providers to overcome these barriers and encourage consistent use of HIV prevention services. Leadership participants shared concerns related to medical mistrust and lack of provider compassion, similar to experiences shared by BSGM community members.

Discussion

This study addresses critical gaps in HIV prevention for BSGM communities in the US South, where social and structural barriers exacerbate health disparities. Our findings reveal two key themes: (1) How do We Navigate and Negotiate PrEP when the Options are “Survival” vs. “Health”? and (2) Compassion from Others is the Antidote to Mistrust When We Do not Know Who to Believe.

Within the first theme, BSGM perspectives reveal a tension between accessing HIV prevention services and satisfying basic needs for stable housing and food. Participants described how a lack of education and access to health information and limited financial resources hinder prioritizing HIV prevention or “health.” Additionally, leadership and BSGM community members expressed concerns about confidentiality, fears of stigmatization, and mistrust of healthcare providers, which further impede accessing services like PrEP. Together, these findings underscore how clear, accessible information about PrEP and discreet service delivery options can foster a supportive, safe(r), stigma-reduced environment for BSGM individuals seeking HIV prevention services.

Within the second theme, BSGM community members shared negative experiences, spanning judgmental treatment, feelings of being unsupported, and directly dismissive attitudes from health care providers, resulting in tangible delays in care and mistreatment. These encounters were shared as additional drivers of mistrust in the healthcare system, further exacerbating a series of discouraging HIV prevention engagement experiences for BSGM. Conversely, participants identified how trusted, compassionate, LGBTQIA-friendly providers, and empathetic support from social networks are vital to alleviate stigma and medical mistrust. BSGM community members highlighted instances where compassionate interventions—such as guidance from peers or LGBTQIA-friendly healthcare providers—helped restore trust and encouraged proactive health behaviors. Collectively, study insights speak to the urgent need for equitable, dignified, and compassionate care tailored to the basic human rights and needs of BSGM individuals. Without compassionate care, the route to informing and supporting BSGM is unclear, and likely remains a major pitfall of access to HIV prevention services.

These findings support and expand upon existing literature on BSGM engagement in HIV prevention services, underscoring how structural and social determinants, particularly in the US South, exacerbate healthcare disparities (2). They reveal the unique barriers BSGM individuals face, often compounded by intersecting issues of stigma, socioeconomic disadvantage, and discrimination. Addressing these barriers necessitates tailored, locally responsive interventions, especially for transgender women and other underrepresented groups who face additional structural challenges in accessing PrEP and related services (4, 32, 33).

For instance, we know that social networks play a pivotal role in bridging gaps in healthcare by providing trusted, peer-driven guidance and emotional support, which can mitigate experiences of stigma and mistrust (34). Participants highlighted the value of community and social networks in encouraging HIV prevention engagement and providing a source of accurate, non-judgmental health information. Social networks may help to overcome systemic mistrust that arises from negative healthcare experiences, especially where provider biases and lack of LGBTQIA+ sensitivity have led to disengagement and harm from care.

Additionally, across the two themes, stigma drove barriers to prevention services uptake: participants’ internal struggles, compounded by anticipated or experienced judgment from providers, often resulted in delayed care or avoidance of services. These results confirm existing literature that highlights the multifaceted nature of stigma and its detrimental effects on health outcomes (2, 3). The driving force of stigma imbues the need for initiatives that reduce stigma, enhance health literacy, and empower BSGM individuals through education and self-advocacy.

Lastly, to foster long-term engagement in HIV prevention, programs are needed that engage and empower BSGM where they are. Study results will be used to develop an enhanced Social Network Strategy (eSNS) to leverage social networks to disseminate accurate, culturally responsive health information and bolster community support. Social network interventions may be critical to increase PrEP uptake and inform how we can create more positive experiences within HIV preventive healthcare. Through eSNS, the power of trusted social networks may counter stigma, rebuild trust in healthcare systems, and enhance BSGM access to HIV prevention services. Consistent with qualitative inquiry principles, our findings emphasize transferability rather than generalizability, offering insights that may apply to similar sociocultural contexts within and beyond the US South.

Limitations

While the study provides valuable insights from leadership perspectives and BSGM community members, future research incorporating diverse viewpoints, including those from more than four community members, and including transgender women, is warranted to ensure a comprehensive understanding of HIV prevention service engagement among BSGM populations. Despite efforts to foster open dialog, the possibility of groupthink in focus groups—a phenomenon where the desire for conformity leads to the suppression of dissenting opinions—cannot be entirely discounted (35). However, rigorous interview techniques and facilitation aimed at promoting diverse perspectives were employed to mitigate this potential bias. The multi-site nature of the research team may also have implications for understanding local contexts. To address this limitation, follow-up interviews post-implementation are planned to expand findings and enhance data validity.

It is also important to discern the meaning of emerging themes alongside social network theory. Although the BSGM community member interview guide was informed by social network theory, participants rarely described their experiences using explicit “network” language. Instead, they emphasized trust, representation, and compassion, which are relational elements that operate as the social mechanisms within networks. This pattern may reflect how BSGM participants conceptualize connection less as a structural network and more as relational trust grounded in shared experience and community care. These insights inform eSNS by placing focus on relational trust and compassion as the foundation of effective network-based HIV prevention strategies.

Lastly, this work does not address more structural issues (i.e., policy) identified by both leadership and community members. Rather, the study’s purpose was to identify barriers and facilitators that will guide the design of the forthcoming eSNS intervention; and, while our findings are situated within the Southern context, similar dynamics may manifest in other regions where systemic inequities, stigma, or limited access to affirming care persist. Our findings involve both contextual specificity and potential transferability. Future studies should focus on strategies to address barriers rooted in structural policies and advocate for reforms to eliminate discriminatory practices and promote inclusive healthcare environments.

Conclusion

Our qualitative study explored HIV prevention services for BSGM groups in the US South from the perspectives of HIV service leadership and members of the community. Participants indicated that without basic living needs met, HIV prevention remains a lower priority among BSGM. If BSGM can access HIV prevention services, it is important that they are met with compassion, which necessitates interventions that identify and address modifiable barriers and actionable facilitators. These findings will inform an eSNS intervention tailored with inclusive messaging, local service information, PrEP modalities, and stigma reduction strategies to bolster HIV prevention among BSGM.

First, the findings illustrate the need for wraparound services that address living necessities as a determinant of accessing HIV preventive care. Second, compassion and empathy are synonymous with ethical and responsible approaches to HIV prevention and are critical to supporting BSGM and reducing harm. Finally, our findings illustrate that stigma is a pervasive barrier at every level of the HIV prevention continuum, significantly impacting the health and wellbeing of individuals living with and at increased chance of acquiring HIV. By tackling stigma across levels, it is possible to create an environment where individuals feel safe and supported in seeking the health services they need, ultimately improving health outcomes and quality of life for anyone whose lives may be touched by HIV.

Data availability statement

The datasets analyzed in this study contain sensitive qualitative information. Participants did not consent to public sharing. Data may be available upon reasonable request to the corresponding author, subject to ethical approval.

Ethics statement

The studies involving humans were approved by Institutional Review Board at the UNC Chapel Hill [IRB #22-1988] in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. The studies were conducted in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. The participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study. Written informed consent was obtained from the individual(s) for the publication of any potentially identifiable images or data included in this article.

Author contributions

JE: Data curation, Formal analysis, Investigation, Supervision, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. IaD: Data curation, Supervision, Writing – review & editing. EO: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Writing – review & editing. MaZ: Formal analysis, Writing – review & editing. CG: Conceptualization, Data curation, Writing – review & editing. JM: Data curation, Investigation, Writing – review & editing. ME: Data curation, Formal analysis, Investigation, Writing – review & editing. IsD: Writing – review & editing. DC: Writing – review & editing. UO: Data curation, Formal analysis, Investigation, Writing – review & editing. SM-C: Writing – review & editing. AlD: Conceptualization, Data curation, Writing – review & editing. MI: Writing – review & editing. AnD: Conceptualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. MeZ: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Methodology, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declare that financial support was received for the research and/or publication of this article. The project described was supported by the NIH through grant award number R01AI169602, the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill Center for AIDS Research (P30 AI50410), and the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (F31HD114366 to Jordyn McCrimmon). The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

Acknowledgments

We express our gratitude to all participants in this study, members of the Community Advisory Group, and additional study contributors including Mecklenburg County Public Health Department Staff and members of the UNC CFAR Social and Behavior Science (SBS) Core, including Grace Galphin.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The authors declare that no Gen AI was used in the creation of this manuscript.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Supplementary material

The Supplementary material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fpubh.2025.1695474/full#supplementary-material

Abbreviations

eSNS, Enhanced Social Network Strategy; PrEP, Pre-exposure prophylaxis; PEP, Post-exposure prophylaxis; LGBTQIA+, Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Transgender, Queer, Intersex, Asexual, Plus; BSGM, Black sexual and gender minority/ies; MSM, Men who have sex with men; MSEM, Modified Social Ecological Model; FGD, Focus group discussions; IDI, In-depth interviews; CBO, Community-based organization; EHE, Ending the HIV epidemic.

References

1. CDC. Ending the HIV epidemic in the US goals. In: Ending the HIV epidemic in the US (EHE). (2024). Available online at: https://www.cdc.gov/ehe/php/about/goals.html (Accessed January 20, 2025).

2. Reif, S, Safley, D, McAllaster, C, Wilson, E, and Whetten, K. State of HIV in the US deep south. J Community Health. (2017) 42:844–53. doi: 10.1007/s10900-017-0325-8

3. Zarwell, M, Ransome, Y, Barak, N, Gruber, D, and Robinson, WT. PrEP indicators, social capital and social group memberships among gay, bisexual and other men who have sex with men. Cult Health Sex. (2019) 21:1349–66. doi: 10.1080/13691058.2018.1563912

4. Carter, JW, and Flores, SA. Improving the HIV prevention landscape to reduce disparities for black MSM in the south. AIDS Behav. (2019) 23:331–9. doi: 10.1007/s10461-019-02671-w

5. Dasgupta, S, Tie, Y, Bradley, H, Beer, L, Rosenberg, ES, Holtgrave, D, et al. Characteristics of sexual partnerships among men with diagnosed HIV who have sex with men, United States and Puerto Rico-2015-2019. JAIDS J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. (2020) 84:443–52. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0000000000002388

6. Marano, M, Stein, R, Song, W, Patel, D, Taylor-Aidoo, N, Xu, S, et al. HIV testing, linkage to HIV medical care, and interviews for partner services among black men who have sex with men - non-health care facilities, 20 southern U.S. Jurisdictions, 2016. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. (2018) 67:778–81. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm6728a3

7. Rosenberg, ES, Millett, GA, Sullivan, PS, Rio, C, and Curran, JW. Understanding the HIV disparities between black and White men who have sex with men in the USA using the HIV care continuum: a modelling study. Lancet HIV. (2014) 1:e112–8. doi: 10.1016/S2352-3018(14)00011-3

8. Dodge, B, Ford, JV, Bo, N, Tu, W, Pachankis, J, Herbenick, D, et al. HIV risk and prevention outcomes in a probability-based sample of gay and bisexual men in the United States. JAIDS J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. (2019) 82:355–61. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0000000000002151

9. Hernández-Romieu, AC, Sullivan, PS, Rothenberg, R, Grey, J, Luisi, N, Kelley, CF, et al. Heterogeneity of HIV prevalence among the sexual networks of black and White men who have sex with men in Atlanta: illuminating a mechanism for increased HIV risk for young black men who have sex with men. Sex Transm Dis. (2015) 42:505–12. doi: 10.1097/OLQ.0000000000000332

10. Hurt, CB, Beagle, S, Leone, PA, Sugarbaker, A, Pike, E, Kuruc, J, et al. Investigating a sexual network of black men who have sex with men: implications for transmission and prevention of HIV infection in the United States. JAIDS J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. (2012) 61:515–21. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0b013e31827076a4

11. Lett, E, Dowshen, NL, and Baker, KE. Intersectionality and health inequities for gender minority blacks in the U.S. Am J Prev Med. (2020) 59:639–47. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2020.04.013

12. Kerr, JC, Valois, RF, Diclemente, RJ, Fletcher, F, Carey, MP, Romer, D, et al. HIV-related stigma among African-American youth in the northeast and southeast US. AIDS Behav. (2014) 18:1063–7. doi: 10.1007/s10461-013-0687-6

13. Scott, HM, Irvin, R, Wilton, L, Tieu, H, Watson, C, Magnus, M, et al. Sexual behavior and network characteristics and their association with bacterial sexually transmitted infections among black men who have sex with men in the United States. PLoS One. (2015) 10:0146025. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0146025

14. Wiertz, D, and Lim, C. The rise of the nones across the United States, 1973 to 2018: state-level trends of religious affiliation and participation in the general social survey. Soc Sci. (2021) 8:429–54. doi: 10.15195/v8.a21

15. Flores, AR, Herman, JL, and Mallory, C. Transgender inclusion in state non-discrimination policies: the democratic deficit and political powerlessness. Res Polit. (2015) 2:12246. doi: 10.1177/2053168015612246

16. Spence, AB, Wang, C, Michel, K, Ocampo, JM, Kharfen, M, Merenstein, D, et al. HIV related stigma among healthcare providers: opportunities for education and training. J Int Assoc Provid AIDS Care. (2022) 21:4797. doi: 10.1177/23259582221114797

17. Eaton, LA, Driffin, DD, Kegler, C, Smith, H, Conway-Washington, C, White, D, et al. The role of stigma and medical mistrust in the routine health care engagement of black men who have sex with men. Am J Public Health. (2015) 105:e75–82. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2014.302322

18. Hatzenbuehler, ML, Lattanner, MR, McKetta, S, and Pachankis, JE. Structural stigma and LGBTQ+ health: a narrative review of quantitative studies. Lancet Public Health. (2024) 9:e109–27. doi: 10.1016/S2468-2667(23)00312-2

19. Thompson, J. Rural identity and LGBT public opinion in the United States. Public Opin Q. (2023) 87:956–77. doi: 10.1093/poq/nfad045

20. Caldwell, JA, Borsa, A, Rogers, BA, Roemerman, R, and Wright, ER. Outness, discrimination, and psychological distress among LGBTQ+ people living in the southern United States. LGBT Health. (2023) 10:237–44. doi: 10.1089/lgbt.2021.0295

21. Tobin, KE, and Latkin, CA. Social networks of HIV positive gay men: their role and importance in HIV prevention In: L Wilton, editor. Understanding prevention for HIV positive gay men: Innovative approaches in addressing the AIDS epidemic. New York: Springer (2017). 349–66.

22. Zhang, J, and Centola, D. Social networks and health: new developments in diffusion, online and offline. Annu Rev Sociol. (2019) 45:91–109. doi: 10.1146/annurev-soc-073117-041421

23. CDC Social Network Strategy for HIV Testing Recruitment. (2023). Available online at: https://www.cdc.gov/hiv/effective-interventions/diagnose/social-network-strategy/index.html (Accessed October 10, 2024).

24. Lightfoot, MA, Campbell, CK, Moss, N, Treves-Kagan, S, Agnew, E, Kang Dufour, MS, et al. Using a social network strategy to distribute HIV self-test kits to African American and Latino MSM. JAIDS J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. (2018) 79:38–45. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0000000000001726

25. McCree, DH, Millett, G, Baytop, C, Royal, S, Ellen, J, Halkitis, PN, et al. Lessons learned from use of social network strategy in HIV testing programs targeting African American men who have sex with men. Am J Public Health. (2013) 103:1851–6. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2013.301260

26. Schumann, C, Kahn, D, Broaddus, M, Dougherty, J, Elderbrook, M, Vergeront, J, et al. Implementing a standardized social networks testing strategy in a low HIV prevalence jurisdiction. AIDS Behav. (2019) 23:41–7. doi: 10.1007/s10461-018-2146-x

27. Amirkhanian, YA. Social networks, sexual networks and HIV risk in men who have sex with men. Curr HIV/AIDS Rep. (2014) 11:81–92. doi: 10.1007/s11904-013-0194-4

28. McGoy, SL, Pettit, AC, Morrison, M, Alexander, LR, Johnson, P, Williams, B, et al. Use of social network strategy among young black men who have sex with men for HIV testing, linkage to care, and reengagement in care, Tennessee, 2013-2016. Public Health Rep. (2018) 133:43S–51S. doi: 10.1177/0033354918801893

29. Baral, S, Logie, CH, Grosso, A, Wirtz, AL, and Beyrer, C. Modified social ecological model: a tool to guide the assessment of the risks and risk contexts of HIV epidemics. BMC Public Health. (2013) 13:482. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-13-482

30. Berkman, LF, Glass, T, Brissette, I, and Seeman, TE. From social integration to health: Durkheim in the new millennium☆. Soc Sci Med. (2000) 51:843–57. doi: 10.1016/S0277-9536(00)00065-4

31. Bruan, V, and Clarke, V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual Res Psychol. (2006) 3:77–101. doi: 10.1191/1478088706qp063oa

32. Zarwell, M, Walsh, JL, Quinn, KG, Kaniuka, A, Patton, A, Robinson, WT, et al. A psychometric assessment of a network social capital scale among sexual minority men and gender minority individuals. BMC Public Health. (2021) 21:1918. doi: 10.1186/s12889-021-11970-8

33. Dang, M, Scheim, AI, Teti, M, Quinn, KG, Zarwell, M, Petroll, AE, et al. Barriers and facilitators to HIV pre-exposure prophylaxis uptake, adherence, and persistence among transgender populations in the United States: a systematic review. AIDS Patient Care STDs. (2022) 36:236–48. doi: 10.1089/apc.2021.0236

34. Øgård-Repål, A, Berg, RC, and Fossum, M. A scoping review of the empirical literature on peer support for people living with HIV. J Int Assoc Provid AIDS Care. (2021) 20:66401. doi: 10.1177/23259582211066401

Keywords: HIV, PrEP, sexual and gender minority health, social network strategy, prevention

Citation: Elkins JS, Dale I, Okumu E, Zinck M, Golin C, McCrimmon J, Esposito M, Duguid IT, Craven DM, Onyeama U, Marin-Cespedes S, Diggs A, Indyg M, Dennis AM and Zarwell M (2025) Survival, trust, and compassion: persistent HIV prevention concerns faced by Black sexual and gender minority communities in the US South – a qualitative study. Front. Public Health. 13:1695474. doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2025.1695474

Edited by:

Hao Wu, Capital Medical University, ChinaReviewed by:

Catherine Clair, Johns Hopkins University, United StatesGail Broder, Fred Hutchinson Cancer Center, United States

Copyright © 2025 Elkins, Dale, Okumu, Zinck, Golin, McCrimmon, Esposito, Duguid, Craven, Onyeama, Marin-Cespedes, Diggs, Indyg, Dennis and Zarwell. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Meagan Zarwell, bXphcndlbGxAY2hhcmxvdHRlLmVkdQ==

†ORCID: Meagan Zarwell, orcid.org/0000-0002-3562-7415

Jesse Strunk Elkins1

Jesse Strunk Elkins1 Ian Dale

Ian Dale Marielle Indyg

Marielle Indyg Ann M. Dennis

Ann M. Dennis Meagan Zarwell

Meagan Zarwell