- 1Climate-Resilient Food Systems Division, International Development Research Center, Nairobi, Kenya

- 2Climate-Resilient Food Systems Division, International Development Research Center, Ottawa, ON, Canada

As we approach 2030, Africa remains distant from achieving the second sustainable development goal of zero hunger. Approximately 307 million people in Africa experience hunger, a number that may continue to rise. Therefore, it is imperative to urgently transform food systems to secure access to healthy and sustainable diets for all. Following the 2021 United Nations Food Systems Summit (UNFSS), countries developed commitments to transform their food systems. This paper aims to: (i) review the food system transformation commitments made by five Eastern African countries (Kenya, Uganda, Tanzania, Ethiopia, and Rwanda) following the UNFSS, and (ii) assess their alignment with the UNFSS action areas and the Kampala Comprehensive Africa Agriculture Development Program (CAADP) Declaration. The Food System Transformation Pathways (FSTPs) of each of the five countries were comprehensively reviewed and thematically analyzed. A total of 199 commitments were found. Regarding the UNFSS action areas, many commitments were focused on building resilience to vulnerabilities, shocks and stresses (n = 97), accelerating the means of implementation (n = 79), and advancing equitable livelihoods (n = 60). Regarding the Kampala Declaration, most commitments (n = 91) aligned with building resilient agrifood systems while only a few (n = 13) aligned with strengthening agrifood systems governance. Only 23.6% and 25.6% of the commitments aligned with nourish all people and food and nutrition security, respectively. While all the commitments indicate each country’s ambition in transforming their food systems towards healthiness and sustainability, none of the five country-level FSTPs outline a plan on how the commitments would be delivered, and only two commitments by Tanzania had explicit measurable metrics. Additionally, only Tanzania has so far developed a costed action plan for the implementation of the strategy. Since sustainable food systems are fundamental in promoting food and nutrition security, fostering social equity, and tackling climate change, it is essential for these countries to develop action plans with suitable indicators and monitoring and evaluation (M&E) frameworks to guide the implementation of their commitments. Countries should also regularly review their commitments to ensure their alignment with global and regional food systems transformation agendas, and that they are on track to achieve sustainability in their food systems.

1 Introduction

Despite being five years away from 2030, the world is not yet on track to achieve Zero Hunger, the Sustainable Development Goal (SDG) 2. This is due to malnutrition, unsustainable diets, or a combination of both (Sachs et al., 2024). For instance, in 2024, approximately 8.2% of the global population and 307 million people in Africa faced hunger (FAO et al., 2025). Although there has been some progress in reducing hunger in some regions of the world, Africa remains the continent with the largest percentage of its population facing hunger (20.2%) (FAO et al., 2025). It is estimated that by 2030, approximately 512 million people globally will be facing hunger, 60% of whom will be from Africa (FAO et al., 2025). There remains an urgent need to improve the sustainability of food systems in Africa to ensure that everyone has access to healthy and sustainable diets. In recognition, the United Nations Food Systems Summit (UNFSS) was convened in 2021. The aim of the summit was to inspire nations to transform their food systems to achieve the SDGs (United Nations, 2021). One of the major achievements of the summit was that it was able to revive political will to transform food systems (Kalibata, 2022). For instance, due to the summit, countries developed their Food Systems Transformation Pathways (FSTPs). FSTPs are living documents that contain the commitments made by nations that will help them achieve their food systems vision.1

Laar et al. (2023) recently reviewed the commitments to food systems change that African governments made during the UNFSS. The study reported that the commitments may successfully contribute to feeding the people of Africa but may not nourish them. However, that study did not use the FSTPs of African countries to analyze the commitments and focused on statements made by African Heads of State during the UNFSS. We hypothesize that the FSTPs are more detailed and should give a better perspective of the commitments made by each country. Additionally, there is limited research on the commitments made in the FSTPs of Eastern African countries. Therefore, this project aimed to fill this gap by using the FSTPs of five Eastern African countries (Kenya, Uganda, Tanzania, Rwanda, and Ethiopia) to review their commitments to food systems change. These countries were selected because they face major challenges in achieving zero hunger. Additionally, although Uganda’s progress to achieving zero hunger is moderately increasing, the rest are stagnating (Sachs et al., 2024).

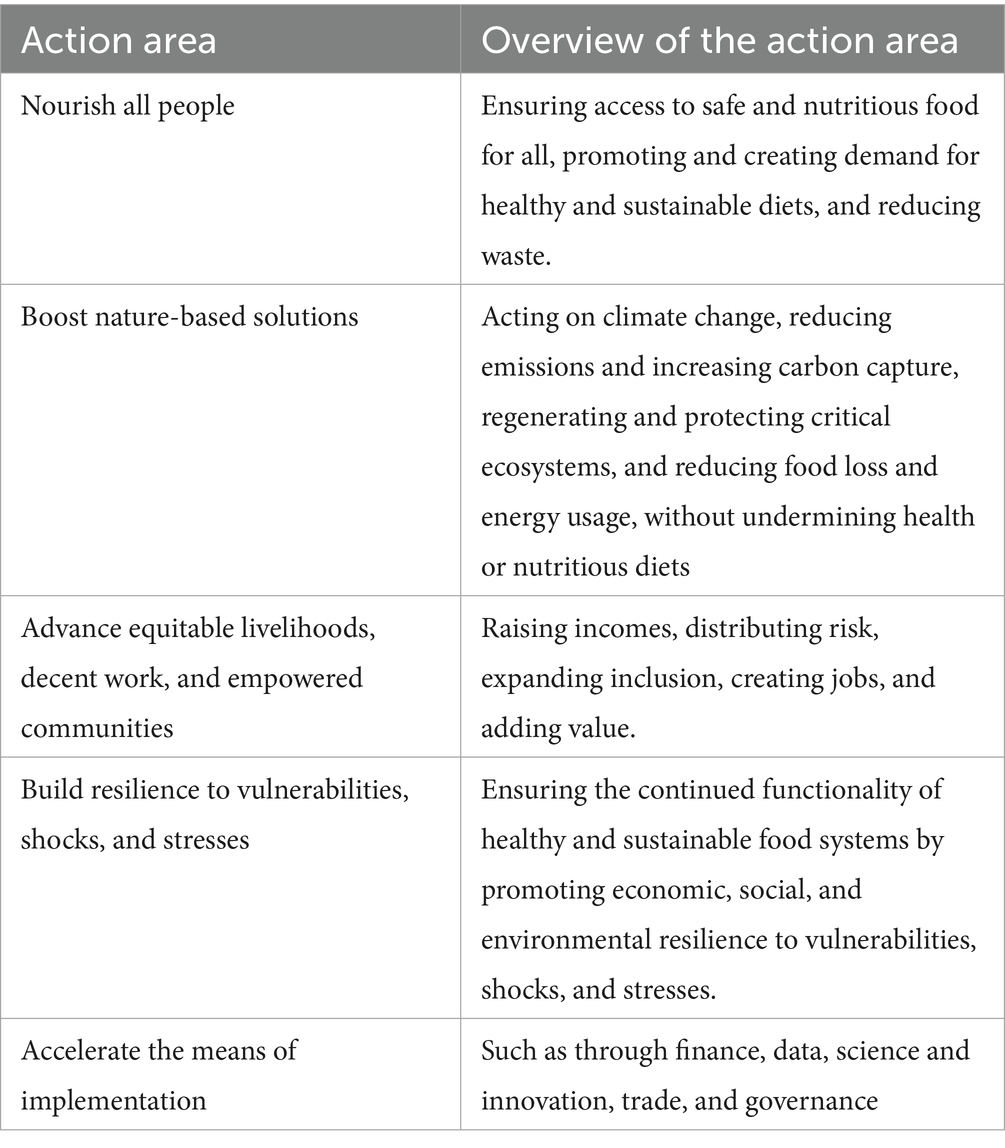

There is also limited research on the extent to which the commitments made by these countries align with the action areas of the UNFSS and the Kampala Comprehensive Africa Agriculture Development Program (CAADP) Declaration on Building Resilient and Sustainable Agrifood Systems in Africa (hereinafter referred to as the Kampala Declaration). The UNFSS has five action areas that are deemed vital in helping nations transform their food systems to achieve the SDGs. The action areas are listed in Table 1 (Laar et al., 2023).

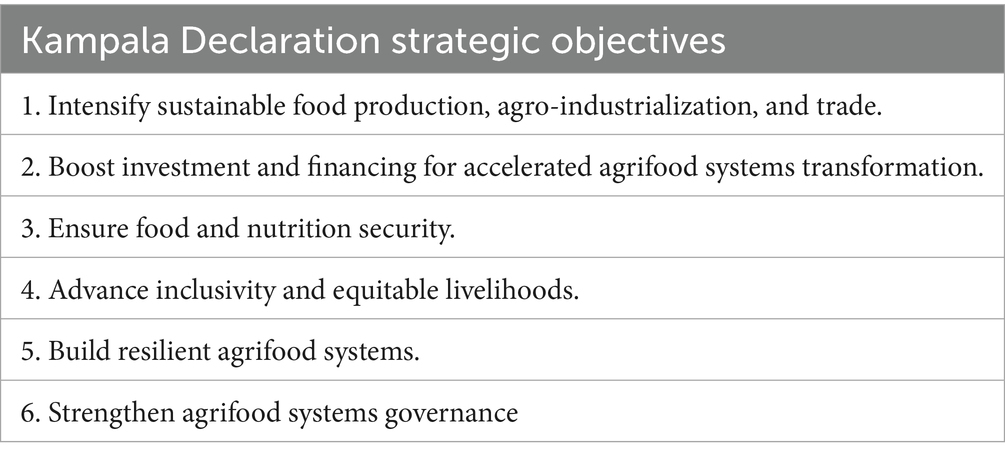

The Kampala Declaration, adopted by the African Union in January 2025, is a decade-long strategy and action plan for Africa’s agrifood systems transformation. The strategy, which will run from 2026 to 2035, has six strategic objectives aimed at enhancing the resilience, inclusivity, and sustainability of Africa’s agrifood systems. The six strategic objectives of the Kampala Declaration are listed in Table 2 (African Union, 2025).

In addition to reviewing the commitments made by the Eastern African countries in their FSTPs, this study will assess the alignment of those commitments to both the UNFSS action areas and the Kampala Declaration. The alignment is critical in not only ensuring that African countries are in line with global and regional food system transformation agendas, but also in examining specific areas where African nations need to strengthen their food system commitments to achieve resilient, inclusive, and sustainable food systems.

2 Methods

This study aims to: (i) review the food system transformation commitments made by five Eastern African countries (Kenya, Uganda, Tanzania, Ethiopia, and Rwanda) following the UNFSS, and (ii) assess their alignment with the UNFSS action areas and the Kampala CAADP Declaration. The study is based on a comprehensive document review of the FSTP of each of the five countries to provide a cross-country comparative analysis. The FSTPs were obtained from the UNFSS website (see text footnote 1). To ensure the updated FSTPs were used, a further search was conducted on relevant government websites of the countries using the following search terms: “food systems transformation pathway,” “transformation pathway,” and “food systems transformation.” This search led to the finding of the revised Ethiopia’s FSTP updated in May 2024.2 All the commitments in the FSTPs were thematically analyzed (see Supplementary Table 1). The thematic analysis of the commitments used a deductive approach which entailed assessing the alignment of each commitment with the five UNFSS action areas and the six Kampala Declaration objectives. To minimize bias and ensure a valid thematic analysis was generated, a thorough check was done on how each of the 5 action areas and 6 objectives are described by the UN3,4 and the African Union, respectively (African Union, 2025). This led to the generation of a coding rubric that was used to guide the analysis (see Supplementary Table 2). To enhance rigor in the analysis, two independent researchers with a background in nutrition and food systems underwent training to get acquainted with the coding rubric and practice coding test data. Next, they assessed the alignment of each commitment with the 5 action areas and 6 objectives, and this led to the creation of a draft Supplementary Table 1. Supplementary Table 1 was then validated by comparing whether the data charted by the researchers were consistent. The data was found to be consistent. However, in case of any inconsistencies, a third expert would have been invited to give their input. In addition to the updated FSTPs, the study also derived information about any relevant updates made by the countries regarding their food systems transformation, from the latest report by the UN food systems coordination hub.5

3 Results

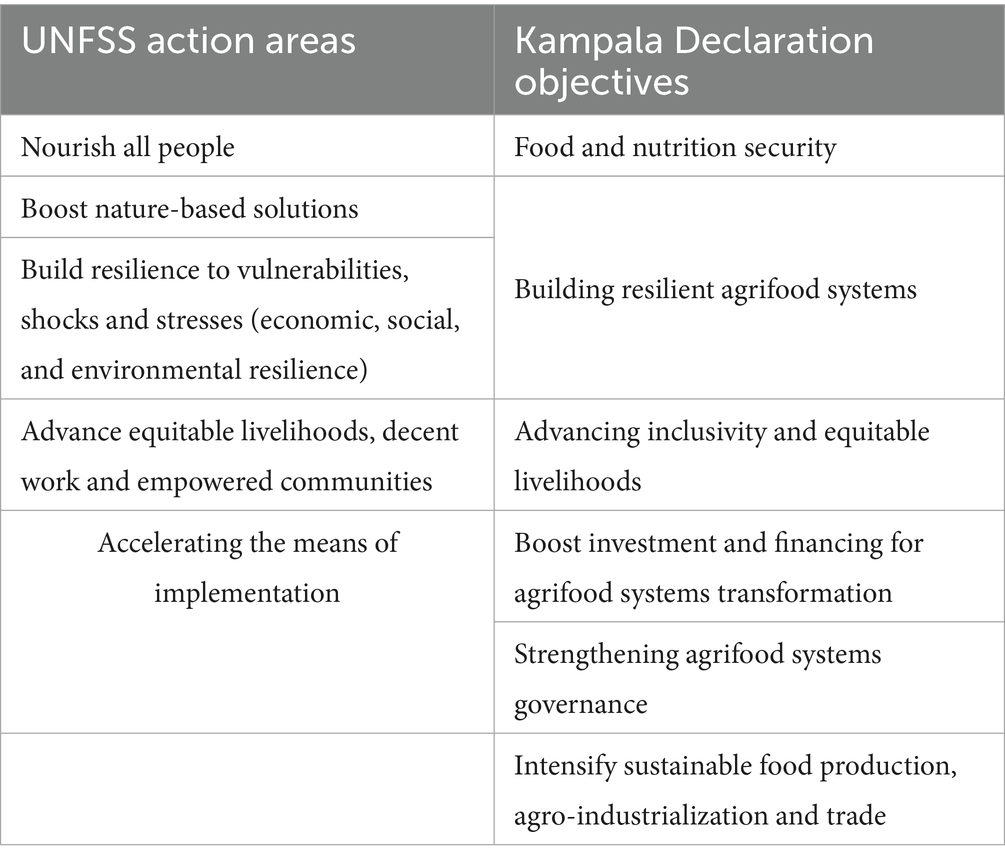

There is coherence between the UNFSS action areas, and the Kampala Declaration objectives as shown in Table 3. The nourish all people action area of UNFSS is coherent with the nutrition security aspect of the food and nutrition security objective of the Kampala declaration. Both the boost nature-based solutions and build resilience to vulnerabilities, shocks and stresses action areas of UNFSS are coherent with the building resilient agrifood systems objective of the Kampala declaration. Additionally, the advance equitable livelihoods action area (UNFSS) is consistent with advancing inclusivity and equitable livelihoods (Kampala declaration). Furthermore, actions aimed at boosting investment and financing for agrifood systems transformation and strengthening agrifood systems governance (Kampala declaration) will contribute to accelerating the means of implementation (UNFSS). Although the intensify sustainable food production objective (Kampala declaration) is not directly coherent with the UNFSS thematic action areas, promoting sustainable food production will indirectly contribute to the nourishing all people action area of the UNFSS.

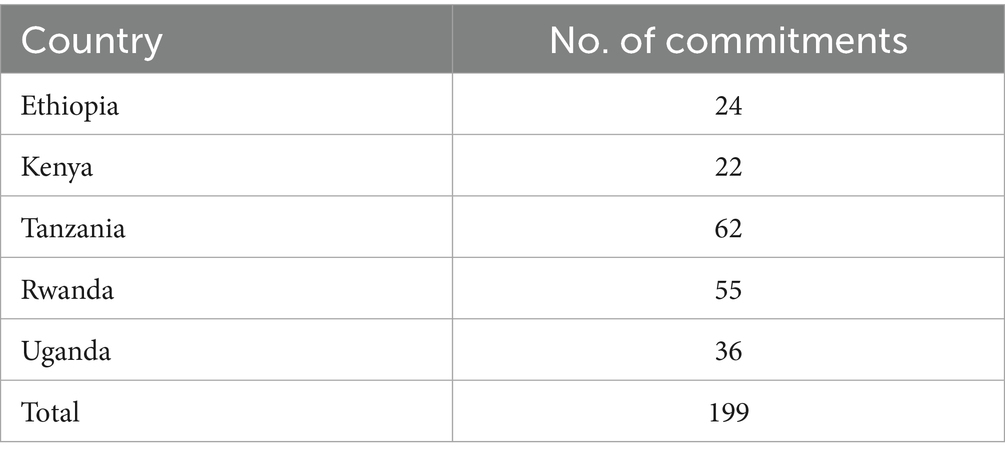

There are a total of 199 commitments in the FSTPs of the five countries (Supplementary Table 1), with the number of commitments varying per country as shown in Table 4. Among the five Eastern African countries, Tanzania has the highest number of commitments (n = 62), while Kenya has the lowest number of commitments (n = 22). However, the variation in the number of commitments may not be significant in understanding the state of food systems transformation in a country. Different nations have different number of commitments since the reporting formats used in the national pathways were not standardized. In preparation for the UNFSS, governments were encouraged to develop strategies that are responsive to local conditions, addressing unique challenges and capitalizing on opportunities within their respective food systems (Candel et al., 2025).

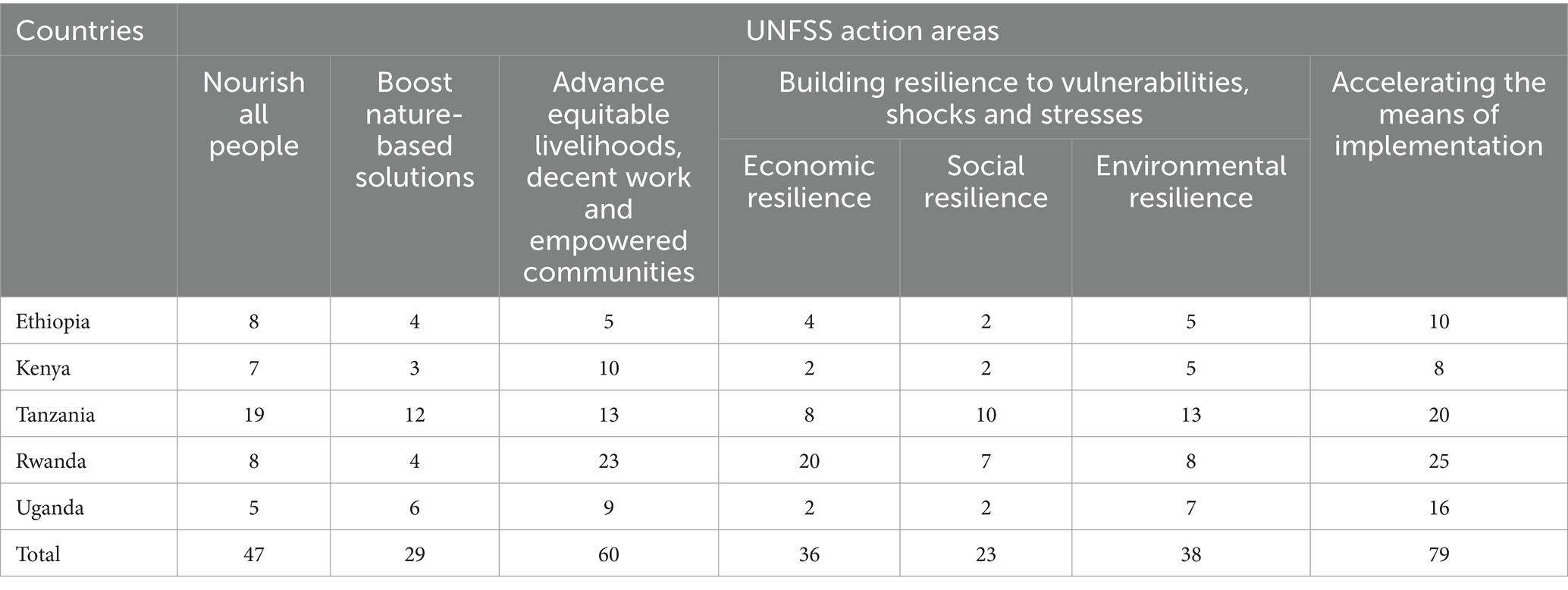

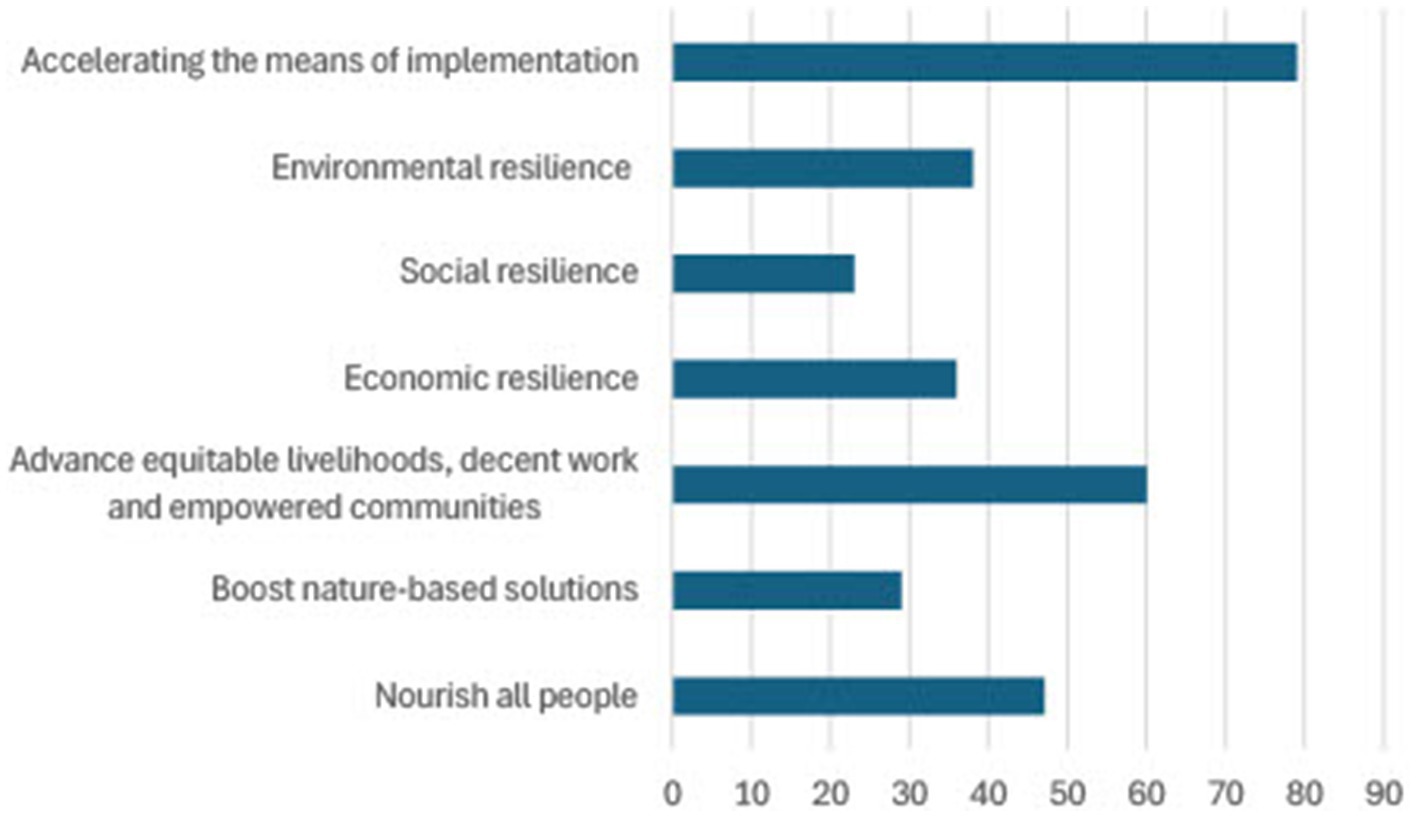

Supplementary Table 1 shows the UNFSS action area and Kampala Declaration objective that each commitment aligns with. Each commitment aligns with at least one UNFSS action area and at least one Kampala Declaration objective, with some commitments aligning with multiple action areas and objectives (see Supplementary Table 1). With regards to the UNFSS action areas, Table 5 and Figure 1 show that most of the commitments (n = 79) align with accelerating the means of implementation followed by advance equitable livelihoods (n = 60) and nourish all people (n = 47). However, adding up all the commitments aligning with the subdivisions of building resilience to vulnerabilities, shocks and stresses [economic resilience (n = 36), social resilience (n = 23), and environmental resilience (n = 38)] totals to (n = 97) thus making this action area to have the highest number of commitments.

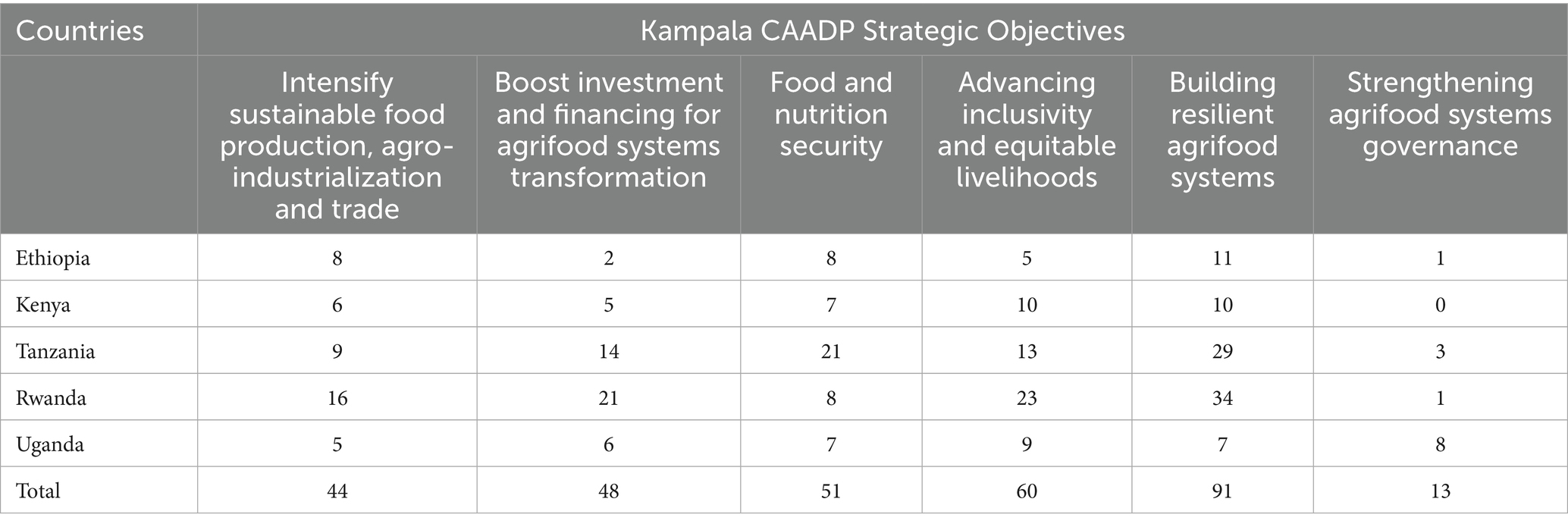

Similarly, with regards to the Kampala Declaration strategic objectives, Table 6 and Figure 2 show that most of the commitments (n = 91) align with building resilient agrifood systems followed by advancing inclusivity and equitable livelihoods (n = 60) and food and nutrition security (n = 51). In contrast, only a few commitments (n = 13) align with strengthening agrifood systems governance.

Promoting school feeding seems to be significant in the transformation of East African food systems since all the countries, apart from Uganda, make specific references to school feeding as shown in Table 7. However, it is noted in the Uganda’s FSTP that the country’s food system transformation process will be supported by existing policy and legislation frameworks. Among these frameworks includes the Uganda Vision 2040 which recommends the development of a school feeding policy.

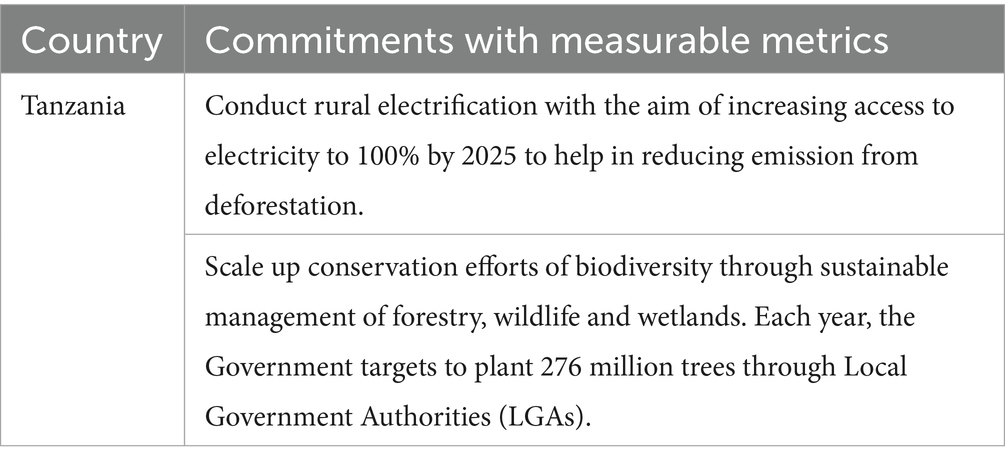

Furthermore, while all the commitments demonstrate that the countries are ambitious in transforming their food systems towards healthiness and sustainability, none of the five FSTPs outlines a plan on how the commitments would be delivered. Similarly, apart from two commitments by Tanzania (Table 8), none of the commitments had explicit defined indicators or measurable metrics.

4 Discussion and recommendations

This study assessed the food systems transformation commitments in Eastern Africa and their alignment with the UNFSS action areas and the Kampala Declaration. The study determined that despite varying commitments, all countries share an ambitious vision for sustainable food systems. For instance, Rwanda is committed to ensuring each poor family has at least one cow, while Tanzania is committed to planting 276 million trees per year (see Supplementary Table 1). This is in line with an analysis of 107 FSTPs that showed the commitments of many countries demonstrate their determination of having sustainable, resilient, equitable, and healthy food systems (EAT, 2022). Laar et al. (2023) also indicated that the commitments are capable of leading to food systems transformation. Although the variation in the number of commitments is not a strong indicator of the extent of food systems transformation within a country, Laar et al. (2023) suggested that the differences may be due to the different levels at which the countries may be in their efforts towards food systems transformation – countries with less commitments may already be at an advanced level of food system transformation than countries with many commitments. The number of commitments per country may also be influenced by each country’s priority focus areas in food systems transformation (United Nations, 2022). Similarly, some countries’ food systems transformation process is embedded in already existing policy and legal frameworks. For instance, in the Uganda’s FSTP, it is noted that the Third National Development Plan (NDP III), one of the key policy frameworks, has five programs that focus on food systems transformation. This existing policy framework integrates with the FSTP to support the food systems transformation process. The results of our study that each commitment aligns with one or more UNFSS action areas are similar to those reported by Kalibata (2022) and Laar et al. (2023). Since the findings have also indicated that the UNFSS action areas have some coherence to the Kampala Declaration objectives, it is also expected that the commitments should align with the latter, as this study has revealed.

In our study, the majority of the commitments were focused on building resilience to vulnerabilities, shocks and stresses, accelerating the means of implementation, and advancing equitable livelihoods. This is partly consistent with Laar et al. (2023) who report that most of the commitments made by Heads of States during the UNFSS were focused on building resilience to shocks, sustainable production systems, hunger and food security. The focus on advancing equitable livelihoods is critical in ensuring the long-term sustainability of food systems. Neufeld et al. (2023) reveal that the livelihoods of vulnerable groups are disproportionately affected by environmental, economic, and political factors, among others, yet they play a role in contributing to better food systems, such as through food production. Similarly, inequalities can prevent vulnerable groups from benefiting from actions aimed at improving their lives. The capacities of the vulnerable need to be enhanced to promote the long-term sustainability of food systems and to ensure they benefit from better food systems as sustainable food systems should improve nutrition and food security for everyone.

Out of the 199 commitments, 23.6% (n = 47) and 25.6% (n = 51) aligned with nourish all people and food and nutrition security, respectively. Laar et al. (2023) pointed out that although most of the commitments made by Heads of States during the UNFSS were focused on addressing hunger and food security, the health and nutrition dimension of sustainability was featured in only a few countries. Laar et al. (2023) further revealed that although the commitments may successfully contribute to feeding Africa, this may not automatically translate to nourishing people. This is because nutrition security not only considers food security but also the nutritional value of food (Sibanda and Mwamakamba, 2021). Thus, it is important for countries to promote nutrition security in addition to food security. Nonetheless, health and diets can be improved by improving food systems (Sibanda and Mwamakamba, 2021). Therefore, while efforts to nourish all people need to be enhanced, the multi-dimensional focus of sustainable food systems is equally important in promoting gains in nutrition.

Furthermore, Ethiopia, Kenya, Rwanda and Tanzania make specific references to school feeding in their FSTPs and the Uganda Vision 2040 recommends the development of a school feeding policy. School feeding seems to be prominent in Africa since a study revealed that 95% of African countries have school meal programs (Wineman et al., 2022). This prominence may be attributed to the fact that school meals serve multiple purposes including providing a safety net, enhancing the nutrition of children, promoting the attainment of education goals, and strengthening rural economies (Wineman et al., 2022). Since the nutrition crisis disproportionately affects children, school feeding can help in tackling this challenge (Pastorino et al., 2023). Furthermore, in addition to the co-benefits for children and the wider society that school feeding programs have, they also act as a catalyst for equitable, resilient, and sustainable food systems (Pastorino et al., 2023). Consequently, investment in school feeding is critical in contributing to the transformation of food systems.

The current study determined that only 13 commitments align with strengthening agrifood systems governance. Given the critical role governance plays in driving systemic change, this is a serious gap. Kraak and Niewolny (2024) report that to sustainably transform food systems, effective governance is needed, because desirable changes can be inhibited or promoted by different political ideologies. For instance, unsustainable food systems could be reformed or maintained depending on the existing governance approaches. Kraak and Niewolny (2024) also suggest that to support food systems transformation, multilevel and multistakeholder collaboration is essential. According to the UN food systems coordination hub (see text footnote 5), good governance mechanisms have been adopted by some African countries. For example, Uganda has established a National Food Systems Coordination Committee to coordinate the realization of the country’s food systems agenda, while Kenya has a National Food Systems Steering Committee and a National Food Systems Technical Working Group to support the country’s food systems transformation effort. This shows that African countries are not completely off track in strengthening governance for better food systems. However, since few commitments align with strengthened food systems governance, the recommendation of this study is that these countries review their food systems transformation strategies to strengthen and adopt the best practices in food systems governance. An example of a best practice in food systems governance is having both multilevel and multistakeholder governance structures (de Vries and Keats, 2024; Kraak and Niewolny, 2024).

Although the commitments are promising, none of the five FSTPs outline a plan on how the commitments would be delivered, and only two commitments (Table 8) had measurable metrics. This finding is in line with another study that showed very few countries globally have outlined a plan of executing their commitments (EAT, 2022). Among the five Eastern African countries, only Tanzania has developed a costed action plan, so far, for the implementation of their commitments (see text footnote 5). There is a need for the other countries to develop action plans with appropriate indicators and M&E frameworks to guide the implementation of the commitments. This will help in promoting accountability, allocating sufficient resources, and tracking the progress of food systems transformation to ensure the countries stay on track. Having appropriate matrices also helps in measuring the costs of inaction (Sibanda and Mwamakamba, 2021). Nigeria has a detailed food systems transformation implementation strategy that has well-defined actions for execution of the strategy, appropriate indicators, and M&E framework (Federal Ministry of Budget and Economic Planning, 2024). This detailed implementation strategy provides one example from which other African countries might draw relevant insights as they develop implementation strategies tailored to their specific contexts. Burgaz et al. (2025) determined that inadequate finances are a barrier to the development and implementation of food systems policies in Sub-Saharan Africa. Thus, recognizing that inadequate financing could be a potential barrier to the development of costed action plans, African countries can explore innovative financing models, including public-private partnerships, to help overcome this barrier.

4.1 Strengths and limitations

The major strength of this study is that it used updated versions of the countries’ FSTPs. Unlike the statements made by Heads of States during the UNFSS, the updated pathway documents provide detailed information about the countries’ food systems transformation commitments. However, although the FSTPs are detailed, the information available in the FSTPs may not be an accurate representation of the total food systems transformation initiatives of a country. In addition to the updated FSTPs, the study also derived information about the development of action plans from the latest available report by the UN food systems coordination hub report published on 22 April 2024 (see text footnote 5). Any progress that the Eastern African countries may have made afterwards regarding the development of action plans or M&E frameworks, that have not yet been documented online, may have been missed. Furthermore, there may have been researcher bias in the placement of the commitments into themes. However, measures to reduce this bias, such as prior training and use of two researchers, were put in place.

5 Conclusion

This paper makes a significant contribution to existing knowledge on the subject. While Eastern African countries have made commitments to sustainable food systems, none of the five countries studied in this review have outlined implementation strategies for these commitments, except Tanzania which has developed a costed action plan. To actualize these commitments, countries should create detailed implementation plans with measurable indicators and clear M&E strategies. Regular reviews of commitments and implementation strategies are essential to align with global and regional food systems transformation agendas and ensure progress towards sustainability in food systems.

Data availability statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/Supplementary material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Author contributions

SJ: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Funding acquisition, Investigation, Methodology, Visualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. VM: Supervision, Writing – review & editing. KT: Writing – review & editing. MR: Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declare that financial support was received for the research and/or publication of this article. This work was carried out with the aid of funding from the International Development Research Centre (IDRC), Ottawa, Canada.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The authors declare that no Gen AI was used in the creation of this manuscript.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Author disclaimer

The views expressed herein do not necessarily represent those of IDRC or its Board of Governors.

Supplementary material

The Supplementary material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fsufs.2025.1653570/full#supplementary-material

Abbreviations

CAADP, Comprehensive Africa Agriculture Development Program; FSTP, Food Systems Transformation Pathways; UNFSS, United Nations Food Systems Summit.

Footnotes

1. ^Convenors and Pathways, https://www.unfoodsystemshub.org/member-state-dialogue/dialogues-and-pathways/en.

2. ^Ethiopian-Food-System-and-Nutrition-Synthesis-Report.pdf, https://www.dpgethiopia.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/07/Ethiopian-Food-System-and-Nutrition-Synthesis-Report.pdf.

3. ^Secretary-General’s Chair Summary and Statement of Action on the UN Food Systems Summit | United Nations, https://www.un.org/en/food-systems-summit/news/making-food-systems-work-people-planet-and-prosperity.

4. ^Chapter 2 Action Tracks, https://www.unfoodsystemshub.org/fs-summit-legacy/food-systems-summit-compendium/chapter-2-action-tracks/en.

5. ^PowerPoint Presentation, https://www.unfoodsystemshub.org/docs/unfoodsystemslibraries/regional-progress-reviews/africa/national-pathway-progress-review_unfs-coordination-hub.pdf.

References

African Union (2025) Kampala CAADP Declaration on Building Resilient and Sustainable Agrifood Systems in Africa. Available online at: 44699-doc-OSC68072_E_Original_CAADP_Declaration.pdf (Accessed April 01, 2025).

Burgaz, C., Van Dam, I., Diouf, A., Kouakou, K. P., Mama, O. M., Kou’santa Amouzou, S., et al. (2025). Barriers and facilitators to the development and implementation of public policies addressing food systems in five sub-Saharan African countries and five of their cities. Int. J. Health Policy Manag. 14:8592. doi: 10.34172/ijhpm.8592

Candel, J., Sietsma, A. J., and Biesbroek, R. (2025). National pathways for food systems transformation are limited in scope and degree of ambition. Nature Food 6, 809–816. doi: 10.1038/s43016-025-01206-y

de Vries, A., and Keats, S. (2024) The unique role of governments in food systems governance. Food Systems Governance Brief No. 4. Global Alliance for Improved Nutrition (GAIN). Available online at: https://www.gainhealth.org/sites/default/files/publications/documents/food-systems-governance-brief-4th-18apr24-final.pdf (Accessed May 19, 2025).

EAT. (2022). Food systems summit National Pathways: Analysis report. EAT Forum. Food_System_Summit_National_Pathwyas.pdf

FAOIFADUNICEF, WFP, and WHO (2025). The state of food security and nutrition in the world 2025 – Addressing high food price inflation for food security and nutrition. Rome: FAO et al.

Federal Ministry of Budget and Economic Planning. (2024). National Pathways for Food Systems Transformation in Nigeria: Implementation Strategy. NPFST-Implementation-Strategy-Draft_March_2024.pdf

Kalibata, A. (2022). Reflections on food systems transformation: an African perspective. Global Soc. Challenges J. 1, 138–150. doi: 10.1332/OYYL3696

Kraak, V. I., and Niewolny, K. L. (2024). A scoping review of food systems governance frameworks and models to develop a typology for social change movements to transform food systems for people and planetary health. Sustainability 16:1469. doi: 10.3390/su16041469

Laar, A., Tagwireyi, J., and Hassan-Wassef, H. (2023). From dialogues to action: commitments by African governments to transform their food systems and assure sustainable healthy diets. Curr. Opin. Environ. Sustain. 65:101380. doi: 10.1016/j.cosust.2023.101380

Neufeld, L. M., Huang, J., Badiane, O., Caron, P., and Forsse, L. S. (2023). Advance equitable livelihoods. In J. Braunvon (Eds.), et al., Science and innovations for food systems transformation. (pp. 135–163). Cham: Springer. doi: 10.1007/978-3-031-15703-5_8

Pastorino, S., Hughes, D., Schultz, L., Owen, S., Morris, K., Backlund, U., et al. (2023) School meals and food systems: Rethinking the consequences for climate, environment, biodiversity, and food sovereignty. Discussion Paper. London School of Hygiene & Tropical Medicine, London. doi: 10.17037/PUBS.04671492

Sachs, J. D., Lafortune, G., and Fuller, G. (2024). The SDGs and the UN summit of the future. Sustainable Development Report 2024. Paris: SDSN, Dublin: Dublin University Press

Sibanda, L. M., and Mwamakamba, S. N. (2021). Policy considerations for African food systems: towards the United Nations 2021 food systems summit. Sustainability 13:9018. doi: 10.3390/su13169018

United Nations. (2021). The 2021 United Nations Food Systems Summit. 23 September 2021, New York, NY USA. Available online at https://www.un.org/en/food-systems-summit

United Nations. (2022). Food Systems Sumit Dialogues: Member State Dialogues Synthesis Report 4. Member-State-Dialogue-Synthesis-Report-4-March-2022-EN.pdf (Accessed March 3, 2025).

Keywords: food systems, United Nations Food Systems Summit, CAADP, Food Systems Transformation Pathway, food systems transformation commitments

Citation: Jomo S, Mbao V, Tiessen KHD and Robertson M (2025) Food systems transformation commitments in Eastern Africa and their alignment with the UNFSS action areas and the Kampala CAADP Declaration. Front. Sustain. Food Syst. 9:1653570. doi: 10.3389/fsufs.2025.1653570

Edited by:

Olutosin Ademola Otekunrin, University of Ibadan, NigeriaReviewed by:

Barthelemy Harerimana, Chinese Academy of Sciences (CAS), ChinaSusan Cheruiyot, Aga Khan University, Kenya

Copyright © 2025 Jomo, Mbao, Tiessen and Robertson. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Sofia Jomo, am9tb3NvZmlhQGdtYWlsLmNvbQ==

Sofia Jomo

Sofia Jomo Victor Mbao

Victor Mbao Kevin H. D. Tiessen

Kevin H. D. Tiessen Melanie Robertson

Melanie Robertson