Abstract

The application of biochar in soil has demonstrated benefits in reducing greenhouse gas emissions, improving soil properties, enriching soil microbial communities, and effectively adsorbing pollutants to limit their mobility. This study focuses on the adsorption capacity of biochar for pollutants, specifically targeting Cr(VI) and atrazine. The research investigates the ability of biochar to immobilize Cr(VI) and atrazine within soil environments and explores how acidification of biochar can enhance its adsorption capacity for atrazine. The mechanism behind the enhanced adsorption capacity of acid-modified biochar is also examined. The results indicate that applying just 1% biochar can significantly improve the soil system’s capacity to immobilize Cr(VI). Fine-grained biochar shows a markedly higher adsorption and fixation capacity for Cr(VI), exhibiting up to three times the adsorption amount compared to larger biochar particles under certain conditions, with minimal desorption under acid rain leaching. Acidification was found to enhance the adsorption capacity of biochar for atrazine under certain conditions. Both the pre- and post-acidification biochar adsorption isotherms fit the Freundlich model, and adsorption capacity was notably affected by temperature, increasing with rising temperatures. The adsorption kinetics of pre-acid-modified biochar align with the Elovich model, whereas post-acidification biochar follows a pseudo-second-order kinetic model. The enhanced adsorption capacity of acid-modified biochar for atrazine is attributed to an increase in surface area, pore size, and pore volume, providing more adsorption sites and stronger van der Waals forces. Additionally, acidification alters the surface charge of biochar, leading to strong electrostatic attraction between biochar and atrazine.

1 Introduction

Soil pollution has become a significant concern in China, gaining widespread attention as soil remediation research advances. There is an increasing awareness of the impact of soil pollutants on soil biota and the substantial environmental harm caused by the mobility of pollutants. Evaluations of soil quality now place greater emphasis on the bioavailability and mobility of contaminants (Swartjes, 1999; Fernández et al., 2005). In recent years, researchers have favored in situ remediation techniques for environmental restoration due to their generally lower cost. This approach primarily involves the addition of soil amendments to immobilize pollutants within the soil, simultaneously promoting plant growth and enhancing the self-purification capacity of the ecosystem (Adriano et al., 2004). Soil conditioners derived from plant and animal residues have recently attracted significant attention, such as activated carbon (Downie et al., 2011; Renner, 2007; Whitman et al., 2011), which has been trialed on a small scale in contaminated soil remediation due to its effectiveness in reducing pollutant bioavailability (Brändli et al., 2008). Biochar, derived mainly from agricultural and forestry waste like straw, has shown in numerous studies a high adsorption capacity for common organic pollutants (Wang et al., 2010; Yang et al., 2010; Gomez-Eyles et al., 2011; Beesley and Dickinson, 2011; Cho et al., 2009), such as phenanthrene (Zhang et al., 2010), and inorganic pollutants (Fellet et al., 2011; Cao et al., 2009; Karami et al., 2011). Additionally, biochar can significantly improve soil physicochemical properties (Novak et al., 2009; Atkinson et al., 2010), enhance soil fertility, amend acidic soils (Rondon et al., 2007; Liang et al., 2006; Sohi et al., 2010), reduce nutrient leaching (Poerschmann et al., 2013), increase crop yield (Graber et al., 2010; Asai et al., 2009; Major et al., 2010), stimulate soil microbial growth (Hamer et al., 2004; Atkinson et al., 2010; Yang et al., 2006; Steiner et al., 2007), and reduce greenhouse gas emissions like CO2 (Zhang A. F. et al., 2013; Zhang et al., 2012a; Zhang et al., 2012b).

Cr(VI) and atrazine are two common soil pollutants in China. Cr and its compounds are widely used as raw materials in industries such as electroplating and metallurgy (Su et al., 2016). The emission of various gases, wastewater, and solid wastes can easily lead to the accumulation of Cr in the soil. The presence of Cr in the soil adversely affects plant growth (Arshad et al., 2017) and can also enter the human body through the food chain, thereby posing a threat to human health. Studies have shown that biochar has a certain degree of adsorption capacity for Cr (Wang et al., 2016). However, the environmental conditions in which biochar is applied to soil are complex, and the adsorption effect of biochar on Cr in soil requires consideration of multiple factors. For instance, some studies have indicated that different biochars exhibit varying adsorption efficiencies for Cr, with charcoal showing better adsorption of Cr (VI) than biochars derived from chicken manure and cattle manure (Choppala et al., 2013). Other research suggests that the adsorption and passivation effects of biochar on Cr (VI) are pH-dependent (Ahmad et al., 2012). Therefore, it is of practical significance to investigate whether straw-based biochar demonstrates good adsorption of Cr (VI) in a simulated soil environment under acid rain conditions, although related studies are limited. On the other hand, Atrazine is also a highly hazardous pollutant. Developed by Geigy, Atrazine is a triazine herbicide that was widely used in China as a weed killer. Currently, Atrazine is recognized as a pollutant, and several studies have highlighted its adverse effects on animal and human health (Cooper et al., 1996; Swan et al., 2003; Donson et al., 1999; Leeuwen et al., 1999; Ribas and Surralles, 1998). Consequently, the adsorption of Atrazine by biochar has been a focal point of research. Different studies have shown varying degrees of biochar’s adsorption capacity for Atrazine (Liu et al., 2015; Cheng et al., 2014; Delwiche et al., 2014), but research on the adsorption ability of acid-modified biochar for Atrazine is relatively scarce.

This study uses soil column leaching experiments to investigate the effect of biochar addition on Cr(VI) mobility under simulated normal rainfall and acid rain conditions. Subsequently, biochar was modified through “acid activation,” and the adsorption capacity of the acid-activated biochar for atrazine was tested experimentally. The adsorption mechanisms of biochar and acid-activated biochar for Cr(VI) and atrazine were analyzed to provide fundamental research data supporting the broader application of biochar.

2 Key characteristics and preparation methods of biochar

2.1 Key characteristics of biochar

The term “biochar” first appeared in Lehmann’s book Biochar for Environmental Management: Science and Technology. Lehmann and Joseph (2009) define biochar as a carbon-rich, porous fine particle material produced by the pyrolysis of biomass in an oxygen-limited or anaerobic environment at relatively low temperatures. Biochar primarily comprises carbon (C), hydrogen (H), and oxygen (O) elements, with carbon as the predominant element, typically making up 70%–80% of the content (Lehmann and Rondon, 2006). The carbon structure in biochar consists mainly of aliphatic and aromatic compounds. The biochar surface contains various organic functional groups, primarily oxygen-containing groups, with fewer polar groups; key functional groups include carboxyl, phenolic hydroxyl, and lactone groups (Lehmann and Joseph, 2012). The elemental composition and surface functional groups of biochar are influenced by feedstock type and production methods. For example, studies have shown that biochar derived from animal residues has a lower C/N ratio, higher N, P, and K content, greater ash production, higher porosity, and electrical conductivity than biochar from plant residues (Shinogi et al., 2003; Singh et al., 2010). Bridle’s research found higher levels of heavy metals like copper, zinc, chromium, and nickel in biochar derived from sludge (Bridle and Pritchard, 2004). Gaskin observed that poultry manure-derived biochar contained higher concentrations of aluminum, chromium, nickel, and molybdenum, whereas biochar from peanut shells and pine contained lower levels of these metals (Gaskin et al., 2008). Biochars from different feedstocks also vary in pH, conductivity, and specific surface area. For instance, Raveendran studied biochar made from rosewood, poultry manure, coffee bean husks, and sawdust, finding pH values of 7.64, 9.64, 4.81, and 3.48, and electrical conductivities of 0.4 m/cm, 5.02 m/cm, 5.99 m/cm, and 0.43 m/cm, respectively (Raveendran et al., 1995). Samsuri et al. (2014) examined biochar made from oil palm, noting concentrations of -OH, -CO, and -COOH functional groups at 0.33, 0.34, and 0.31 mmol/g, respectively, with a total oxygen-containing functional group concentration of 0.98 mmol/g. By comparison, rice husk biochar had -OH, -CO, and -COOH concentrations of 0.09, 0.27, and 0.24 mmol/g, with a total concentration of 0.60 mmol/g. Due to the feedstock, biochar surfaces may also contain metal elements; for instance, biochar derived from animal manure contains higher levels of Cu and Zn. Biochar is typically alkaline (Zhang et al., 2011), with its alkalinity attributed mainly to inorganic minerals (Zhang et al., 2011) or the reduction reactions between surface metal oxides and water molecules, generating hydroxide ions in moist environments (Yip et al., 2010). Biochar is relatively stable and resistant to microbial degradation (Lehmann et al., 2008), allowing for long-term preservation. Its large specific surface area and high cation exchange capacity (CEC) are additional notable features of biochar.

2.2 Preparation methods of biochar

The primary method for preparing biochar is pyrolysis (Lehmann and Joseph, 2009; González et al., 2009; Hu et al., 2010). During pyrolysis, raw materials are converted into three components: solid, gas, and liquid. The yield and composition of each component depend on factors such as the properties of the raw materials and the pyrolysis temperature (Mohan et al., 2006). The gaseous phase mainly consists of hydrocarbons like CH4, H2, CO, CO2, and C2H2 (Mohan et al., 2006). The liquid phase, also known as bio-oil, primarily contains methanol, acetic acid, volatile organic acids, and tar (Mullen et al., 2010; Mohan et al., 2006).

Depending on the heating temperature and duration, pyrolysis can be divided into slow pyrolysis, fast pyrolysis, gasification, and hydrothermal carbonization. Slow pyrolysis, also known as conventional carbonization, typically occurs at temperatures of 400 °C–600 °C with prolonged heating times, sometimes lasting days, yielding a biochar production rate of 20%–40% (Uchimiya et al., 2011; Antal et al., 2000). Fast pyrolysis operates at similar temperatures (400 °C–600 °C) but with a short pyrolysis time of around one second, producing a biochar yield of 10%–20% (Wei et al., 2006; DeSisto et al., 2010). The main difference between slow and fast pyrolysis is that slow pyrolysis yields more biochar, while fast pyrolysis produces a higher quantity of bio-oil.

Gasification involves converting biomass at high temperatures (800 °C–1000 °C) into a syngas mixture containing CO, H2, and CO2, with a pyrolysis duration of 5–20 s and a biochar yield of approximately 10% (Meyer et al., 2011). Hydrothermal carbonization (HTC) is a method of biochar production through the pyrolysis of biomass in hot, pressurized water. HTC can be classified based on water temperature: high-temperature HTC (300 °C–800 °C) produces mainly syngas, while low-temperature HTC (below 300 °C) primarily yields biochar. Low-temperature HTC mimics natural coalification of organic matter, though natural coalification occurs over extended periods. HTC pyrolysis times range from 1 to 12 h, with a biochar yield of 30%–60% (Poerschmann et al., 2013; Kruse et al., 2013).

The pyrolysis method, maximum heating temperature, and heating rate significantly affect biochar properties. Studies indicate that increasing pyrolysis temperature enhances the degree of carbonization, enlarges the surface area, but reduces the content of organic functional groups (Chen et al., 2008). Higher pyrolysis temperatures and increased surface areas have also been shown to improve biochar’s adsorption capacity for organic pollutants (Zhou et al., 2010; Kasozi et al., 2010; Wang et al., 2010). The increased surface area of biochar at high temperatures is thought to result from the collapse of micropore walls at elevated temperatures (Sharma et al., 2004).

3 Experiment on the effect of biochar on Cr(VI) mobility

3.1 Experimental materials

Soil samples were collected from areas surrounding Beijing. Surface soil (0–20 cm) was sampled from three points near the collection site and combined to form a composite soil sample. Biochar was prepared using corn stalks as the raw material, which were washed with deionized water and then dried in an 80 °C oven for 12 h. The dried stalks were then ground, placed in a crucible, sealed, and subjected to oxygen-limited conditions. They were heated at a rate of 8.0 °C/min in a muffle furnace until reaching 400 °C, where they were held for 90 min before being naturally cooled. The resulting biochar was removed, washed with 1 mol/L hydrochloric acid, rinsed repeatedly with deionized water, and dried.

A simulated acid rain solution was prepared with a pH of 4.0. This pH was chosen based on data on acid rain in Beijing from 2003 to 2009, which showed an average pH of approximately 4.5 and an increasing number of acid rain occurrences with pH around 4.0 in recent years (Pu et al., 2010).

3.2 Experimental method

The soil column leaching experiment was conducted as a parallel control experiment using four vertically placed glass soil columns, each 19 cm high with an internal diameter of 4 cm. Quartz sand (1 cm thick) was added to both the top and bottom of each soil column to facilitate even water distribution during leaching. Filtrate was collected at the lower outlet of each column in glass containers.

Biochar was applied to the soil in two ways: (1) thorough mixing with the soil and (2) direct surface application on farmland. To account for these two application methods, the soil column experiment setup was designed as shown in Figure 1.

FIGURE 1

Experimental design of soil column.

As shown in Figure 1, column S serves as the control, containing 100 g of soil. In column BS1, 100 g of soil is placed with 1.0 g of biochar spread uniformly on the soil surface. In columns BS2 and BS3, 100 g of soil is thoroughly mixed with 1.0 g of biochar. The biochar particle size in BS2 is greater than 0.3 mm, while in BS3, it is smaller than 0.3 mm. Given that soil density is approximately 1.8 g/mL and biochar density is around 0.3 g/mL, the addition of biochar does not significantly alter the overall weight, so the density across the four columns can be considered approximately uniform (Beesley et al., 2010). The biochar application rate in the columns is 1.0 g, equivalent to about 8 t/ha in agricultural fields, aligning with biochar application rates reported in the literature (Van Zwieten et al., 2010).

After setting up the soil columns, the soil was initially saturated with deionized water (Beesley et al., 2010). A Cr(VI) solution with a concentration of 60 mg/L was then leached from the top of each column, with 20 mL applied at a drip rate of 5 mL/h once per day for 6 days, totaling 120 mL. Filtrate was collected promptly from the bottom of each column to measure the Cr(VI) content in both the soil and the filtrate, assessing the soil/biochar adsorption efficiency for Cr(VI).

Based on the annual average rainfall of 461.21 mm in Beijing from 2003 to 2008 and an acid rain occurrence frequency of 50%, the average acid rainfall is estimated at 230.6 mm. In this experiment, leaching was conducted daily with 20 mL of simulated acid rain for 6 days, totaling 120 mL. Filtrate was promptly collected at the bottom of each column, and the Cr(VI) content in both the soil and filtrate was measured to evaluate the impact of acid rain leaching on Cr(VI) adsorption by the soil/biochar system.

3.3 Experimental results

3.3.1 Properties of soil and biochar

The basic properties of the soil and biochar, as obtained through analytical testing, are presented in Tables 1–3. As shown in Table 1, the soil sample primarily consists of coarse sand (1.0–0.5 mm) at approximately 55.6%, with medium sand (0.5–0.25 mm) at about 27.2%, and fine sand (0.5–0.05 mm) comprising roughly 14.9%. The soil sample has a pH of 8.69, and the content of metal elements like Fe and Mn is relatively low. This sample represents a typical soil from the North China region, differing from the acidic soils commonly found in southern China, making it representative of this area. The Cr content in the soil sample is 74.83 μg/g, below the national standard for uncontaminated dryland soils of 90 μg/g (GB15618-1995), indicating that the soil can be considered uncontaminated with respect to Cr.

TABLE 1

| Particle size | pH | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Silt (<0.05 mm) | Fine sand (0.25 mm-0.05 mm) | Medium sand (0.5 mm-0.25 mm) | Coarse sand (1.0 mm-0.5 mm) | |

| 2.3% | 14.9% | 27.2% | 55.6% | 8.69 |

The elemental properties of soil.

TABLE 2

| Element | Content | Element | Content |

|---|---|---|---|

| CaO | 2.819% | MgO | 2.636% |

| K2O | 2.804% | MnO | 0.120% |

| Fe2O3 | 5.762% | Na2O | 1.748% |

| Cr | 74.83 μg/g | P2O5 | 0.171% |

| TiO2 | 0.680% | SiO2 | 60.155% |

| Al2O3 | 14.805% |

The main elements of soil.

TABLE 3

| Particle size/mm | pH | Specific surface Area (m2/g) | Pore volume/(cm3/g) | Pore size/nm | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| >0.5 | 0.5–0.3 | <0.3 | ||||

| 11% | 63% | 26% | 6.87 | 4.346 | 0.008 | 1.451 |

The elemental properties of biochar.

The biochar sample has a relatively uniform particle size distribution, with most particles ranging from 0.3 to 0.5 mm, and a specific surface area of 4.346 m2/g. Scanning electron microscopy (SEM) and energy-dispersive spectroscopy (EDS) analysis, shown in Figure 2, reveal the porous and loose structure of biochar, which significantly increases its surface area and enhances soil aeration. Biochar itself is a gray-black substance, and when incorporated into soil, it darkens the overall soil color, increasing solar radiation absorption and promoting crop germination and growth. EDS analysis indicates that the main elements in biochar are carbon (C) and oxygen (O), with platinum (Pt) appearing in Figure 2 due to Pt coating applied during sample preparation for EDS characterization. Adding biochar to soil can also increase soil carbon storage, helping to balance the atmospheric carbon cycle.

FIGURE 2

Energy dispersive spectrometer image of biochar.

3.3.2 Adsorption effect of biochar on Cr(VI)

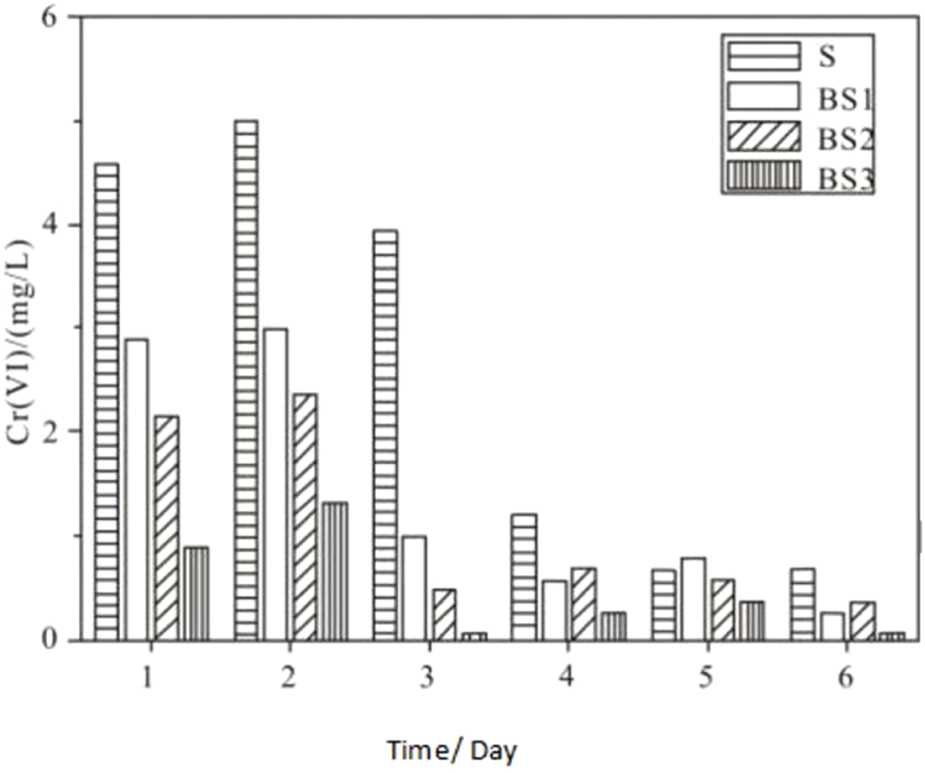

After six leaching cycles, each with 20 mL of Cr(VI) aqueous solution (60 mg/L), the filtrate collected after each leaching was analyzed. The results, shown in Figures 3, 4, indicate that in column S, which contains only soil, the Cr(VI) concentration in the filtrate consistently increased with each leaching cycle, reaching relatively high levels. This suggests that the soil alone cannot effectively adsorb Cr(VI), allowing it to readily enter the soil solution and potentially migrate to groundwater.

FIGURE 3

Cr(VI) concentration in leaching.

FIGURE 4

Cr(VI) cumulative change in leaching.

In contrast, the filtrate from biochar-containing columns (BS1, BS2, and BS3) also showed an increase in Cr(VI) concentration over time, but the levels were significantly lower compared to the control column. This demonstrates that adding biochar makes the soil more effective at adsorbing Cr(VI), providing a “locking” effect that immobilizes more Cr(VI) ions and reduces the downward mobility of Cr(VI) in the solution. These findings are similar to those of Beesley et al., who reported that biochar has an enhanced ability to adsorb heavy metals such as As, Cd, and Zn compared to soil particles.

The mechanism behind biochar’s ability to adsorb and immobilize heavy metals is still debated. Some researchers attribute this to the polarity and surface functional groups on biochar, with studies confirming that the adsorption of Pb2+ or Cd2+ increases as the content of polar groups on biochar surfaces increases.

Furthermore, this study examines the effects of different biochar application methods and particle sizes on Cr(VI) adsorption. As shown in Figures 3, 4, the Cr(VI) concentration and content in the leachate from columns BS1 and BS2 are similar, suggesting that the application method of biochar has little impact on its Cr(VI) adsorption capacity. This also indicates that the increase in Cr(VI) adsorption is primarily due to the presence of biochar itself, with the adsorption process occurring between biochar and Cr(VI).

Column BS3, which contains smaller biochar particles (<0.3 mm), shows significantly lower Cr(VI) concentrations in the leachate than columns BS1 and BS2, demonstrating that particle size has a notable influence on Cr(VI) adsorption. Since the leachate volumes were consistent across all columns, the total Cr(VI) content in the filtrate for columns BS2 and BS3 was calculated from concentration and volume. The difference between the initial and leachate Cr(VI) content represents the total Cr(VI) adsorption in the columns. The data reveal that BS3, with smaller biochar particles, adsorbed approximately three times more Cr(VI) than BS2, which had larger particles. This is because smaller biochar particles can adsorb more Cr(VI) in a shorter period, with adsorption capacity increasing as particle size decreases and saturation reached more quickly.

Saito et al. also found that smaller biochar particles achieve adsorption equilibrium more rapidly. Therefore, the Cr(VI) adsorption capacity of biochar is not only related to surface charge and functional groups but is also closely associated with particle size. When biochar is incorporated into soil, these properties can alter the soil’s physicochemical characteristics, thereby affecting the leaching behavior of pollutants in soil environments.

3.3.3 Effect of simulated acid rain on the immobilization of Cr(VI) by biochar

The data from the soil column leaching experiment indicate that adding biochar to soil effectively adsorbs Cr(VI) in the leachate, thereby immobilizing Cr(VI). However, this adsorption and immobilization capacity may be influenced by external natural conditions, such as acid rain leaching. This raises the question of whether biochar can continue to immobilize Cr(VI) under such conditions, preventing Cr(VI) from desorbing and migrating back into the soil solution or groundwater.

To address this, the experiment was extended to simulate natural conditions by leaching the Cr(VI)-treated soil columns with simulated acid rain. This phase aimed to evaluate the effectiveness of biochar in immobilizing Cr(VI) under acid rain conditions. The experimental results are presented in Figures 5, 6.

FIGURE 5

Cr(VI) concentration in eluate solution under acid rain leaching.

FIGURE 6

Cumulative change in eluate solution under acid rain leaching.

In Figures 5, 6, a comparison between columns BS1, BS2, BS3 (containing biochar) and column S (control) shows that leaching the columns with simulated acid rain did not result in significant desorption of Cr(VI) from the biochar. Figure 5 demonstrates that more Cr(VI) remained immobilized within the biochar-containing columns, while Figure 6 shows a lower Cr(VI) concentration in the acid rain leachate from the biochar columns. These results confirm that the addition of biochar provides a notable immobilizing effect for Cr(VI), as the Cr(VI) adsorbed onto the biochar surface resists desorption by acid rain. This stability may be due to the formation of more robust chelates and complexes between biochar and Cr(VI) ions, making biochar a more stable adsorbent for Cr(VI) compared to soil particles.

The column with smaller biochar particles (BS3) exhibited over 50% less Cr(VI) desorption during acid rain leaching compared to columns BS1 and BS2, which contained larger biochar particles. This finding suggests that smaller biochar particles have a stronger Cr(VI) immobilization capacity, likely for two reasons: First, smaller particles offer a larger effective adsorption surface area and greater adsorption capacity, enabling stronger binding with Cr(VI) than larger biochar particles. Mechanistically, this means a reduction in van der Waals interactions in favor of surface functional group binding, forming more stable complexes or chelates, allowing smaller biochar particles to more effectively and stably adsorb Cr(VI). Second, in columns with smaller biochar particles, biochar contributes more to Cr(VI) adsorption compared to soil particles, which hold a smaller portion of Cr(VI). Soil particles tend to desorb Cr(VI) more readily than biochar, as reflected by the higher Cr(VI) concentrations in the leachate from columns with larger biochar particles.

Additionally, monitoring the pH changes in the leachate (Figure 7) reveals that, although the initial simulated acid rain solution was acidic with a low pH, the leachate pH remained slightly basic for all columns. This is likely due to the strong buffering capacity of the soil, which is inherently alkaline in this experiment. Although higher pH levels can enhance metal ion precipitation and reduce solubility (Bridle and Pritchard, 2004), with studies showing significant pH effects on biochar’s adsorption of Cd and Zn within a pH range of 4-6 and Pb within a range of 2–4, the soil’s buffering capacity in this experiment maintained stable pH conditions. Therefore, biochar’s Cr(VI) immobilization capacity in this experiment primarily depends on particle size and surface functional group interactions as discussed earlier.

FIGURE 7

pH of acid rain leaching eluate solution.

3.3.4 Cr(VI) residual amount in different soil columns

The previous leaching experiments analyzed the Cr(VI) concentration in the filtrate, examining the effect of biochar addition on Cr(VI) immobilization and migration. Correspondingly, this section further explores the adsorption effect of biochar on Cr(VI) by analyzing the residual Cr(VI) content within each soil column. As shown in Figure 8 (OS for soil analysis and System for biochar/soil mixture analysis), the Cr(VI) concentration in the soil sample (Soil) was initially 74.8345 μg/g. After leaching with the Cr(VI) solution, the Cr content in each column increased to varying degrees. Column S, which lacks biochar, showed the highest Cr(VI) concentration in soil, reaching 112.19 μg/g. Possible reasons for this is:

FIGURE 8

Cr(VI) residue in different soil column.

3.3.4.1 Competitive adsorption

The process of Cr(VI) adsorption by biochar is dynamic, involving competition between biochar and soil for Cr(VI) ions. Biochar not only has a larger specific surface area but also contains various surface functional groups, such as carboxyl, hydroxyl, and phenolic groups (Uchimiya et al., 2011). These functional groups give biochar significant surface polarity and a strong capacity for both physical and chemical adsorption. This interaction may help to stabilize Cr(VI) in the soil-biochar mixture. Previous studies have confirmed complexation reactions between Cu, Pb, and biochar surface functional groups, showing biochar’s effective adsorption of these ions (Uchimiya et al., 2011).

Although the overall system shows a greater immobilization of Cr(VI), the soil fraction within that system retains a lesser amount due to the superior and predominant adsorptive capacity of biochar. As a result, under identical pollution conditions, the total amount of Cr(VI) adsorbed by soil particles in biochar-amended columns is lower than in the column without biochar. A comparison between BS2 and BS3 shows that when biochar is evenly mixed with soil, it is more effective at reducing Cr(VI) concentration in the soil.

4 Adsorption experiment of acid-modified biochar for atrazine in water

4.1 Experimental materials

The raw material for biochar was agricultural corn stalks, which were washed with deionized water and dried in an 80 °C oven for 12 h. After drying, the stalks were ground using a micro plant sample grinder, then placed in a tubular atmosphere furnace. Nitrogen gas was introduced to create an anaerobic environment, and the temperature was raised to 450 °C at a rate of 5.0 °C/min, held for 120 min, then naturally cooled. The biochar was then sieved through a 2 mm screen to produce the original biochar (C). After testing, the pH value of the original biochar(C) was measured at 6.51. The acid-modified biochar (SC) was prepared by soaking the original biochar in 1 mol/L hydrochloric acid for 24 h, after which the acid solution was removed, and the biochar was dried.

Atrazine Stock Solution: Dissolve 0.20 g of atrazine (Anpu Shanghai, standard, 99% purity) in methanol (Shanghai Anpu, HPLC grade) and dilute to 200 mL. Sonicate for 10 min to obtain a 1.0 g/L atrazine stock solution.

CaCl2 Solution: Dissolve 11.09 g of dry CaCl2 (analytical grade, Beijing Chemical Plant) in deionized water and dilute to 1 L, yielding a 0.1 mol/L CaCl2 background solution.

4.2 Experimental methods

4.2.1 Adsorption kinetics experiment

Using CaCl2 as the background solution, prepare a 40 mg/L atrazine solution, adding 50 mL of this solution to a 50 mL glass Erlenmeyer flask. Weigh 0.1 g each of C and SC and add to separate flasks for the adsorption experiment. The flasks are sealed with parafilm, placed on a constant-temperature shaker set at 298.15 K, and shaken in the dark at 200 r/min. Samples are collected at intervals of 5, 10, 20, 40, 60, 180, 360, 720, and 1440 min, with three replicates for each time point.

4.2.2 Adsorption thermodynamics experiment

Using CaCl2 as the background solution, prepare atrazine solutions with concentrations of 10.0, 20.0, 30.0, 40.0, and 50.0 mg/L, each with a volume of 50 mL in 50 mL glass Erlenmeyer flasks. Weigh 0.1 g each of C and SC and add to separate flasks for the adsorption experiment. The experiment is conducted at set temperatures of 288.15 K, 298.15 K, and 308.15 K. The flasks are sealed with parafilm, placed on a constant-temperature shaker, and shaken in the dark at 200 r/min for 24 h. Samples are collected with three replicates for each condition.

4.2.3 Adsorption mechanism experiment of acid-modified biochar

Using CaCl2 as the background solution, prepare atrazine solutions (30 mg/L) with pH values of 3, 5, 7, and 9, adding 50 mL of each to 50 mL glass Erlenmeyer flasks. Weigh 0.1 g each of C and SC and add to separate flasks for the adsorption experiment. The flasks are sealed with parafilm, placed on a constant-temperature shaker set at 298.15 K, and shaken in the dark at 200 r/min for 24 h. Samples are collected with three replicates for each condition.

4.3 Experimental results

4.3.1 Measurement of biochar surface potential

The measurement results are shown in Table 4 and Figures 9, 10.

TABLE 4

| Biochar | Zeta potential (mV) | Deviation (mV) | Electric conductivity (mS/cm) |

|---|---|---|---|

| SC | −16.8 | 5.26 | 0.170 |

| C | −30.0 | 8.87 | 0.073 |

Zeta potential report of biochars.

FIGURE 9

Zeta potential distribution(C).

FIGURE 10

Zeta potential distribution (SC).

The test results indicate that the unacid-modified biochar (C) exhibited a stronger electronegativity, reaching −30.0 mV. After acidification, the biochar (SC) showed a reduced electronegativity of −16.8 mV, while acidification also increased the biochar’s electrical conductivity.

4.3.2 Adsorption kinetics experiment

The experimental data were fitted using the pseudo-first-order kinetic equation, the pseudo-second-order kinetic equation, and the Elovich equation.

Pseudo-First-Order Kinetic Equation:

In the equation:

q is the amount of atrazine adsorbed by biochar at time t (mg/kg),

qe is the amount of atrazine adsorbed by biochar at equilibrium (mg/kg),

k is the adsorption rate constant (h-1).

Pseudo-Second-Order Kinetic Equation:

In the equation:

qt is the amount of atrazine adsorbed by biochar at time tt (mg/kg),

qe is the amount of atrazine adsorbed by biochar at equilibrium (mg/kg),

k is the adsorption rate constant (h-1).

Elovich Equation:

In the Elovich equation:

a and b are experimental constants.

A larger value of a and a smaller value of b indicate a higher adsorption rate.

The experimental results, presented in Table 5, show that all three models effectively fit the adsorption processes of both types of biochar. The original biochar conforms more closely to the Elovich equation, while the acid-modified biochar exhibits the highest correlation coefficient with the pseudo-second-order kinetic model. This suggests that atrazine adsorption by the original biochar involves a heterogeneous diffusion process, resulting from multiple concurrent reactions. In contrast, the adsorption mechanism for atrazine on acid-modified biochar tends toward a multi-layer adsorption effect.

TABLE 5

| Biochar | Pseudo-first-order kinetic equation | Pseudo-second-order kinetic equation | Elovich equation | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| K1 (h-1) | qe (mg/kg) | R2 | K2 (h-1) | qe (mg/kg) | R2 | α | β | R2 | |

| C | 0.018 | 6403.155 | 0.923 | 3.062 | 7013.371 | 0.967 | 285.963 | 7.862 | 0.973 |

| SC | 0.020 | 6683.298 | 0.956 | 3.339 | 7243.502 | 0.982 | 356.545 | 7.705 | 0.971 |

Fitting parameters and correlation coefficients.

The change in the suitable kinetic model for each biochar type indicates that acidification alters the properties of biochar, thereby affecting its adsorption mechanism for atrazine.

As shown in Figures 11, 12, the adsorption rate of atrazine by both types of biochar exhibits a rapid initial phase followed by a slower phase. In the rapid adsorption phase, both biochars primarily rely on physical adsorption, with surface diffusion being the main influencing factor. This stage requires low activation energy, allowing atrazine to quickly occupy the adsorption sites on the biochar surface and form more stable chemical bonds, effectively anchoring it to the biochar.

FIGURE 11

Elovich equation adsorption kinetics curves (C).

FIGURE 12

Pseudo-second order kinetic curves (SC).

In the slower adsorption phase, the process mainly involves the diffusion of the adsorbate into the pores of the biochar, which requires higher activation energy, thus resulting in a lower adsorption rate. This stage of adsorption is directly related to factors such as the pore size and volume of the adsorbent, as well as the concentration of the adsorbate. In general, larger pore sizes and volumes in the adsorbent, along with higher adsorbate concentrations, can increase the adsorption rate in this phase.

4.3.3 Adsorption thermodynamics experiment

Isothermal adsorption models are used to describe the adsorption behavior of biochar for organic pollutants. The two most commonly used models are the Langmuir and Freundlich equations.

Langmuir Equation:

In the equations:

qmax and K are adsorption constants,

qe is the equilibrium adsorption amount (mg/kg),

Ce is the equilibrium concentration (mg/L),

K is the adsorption parameter, with larger values indicating stronger adsorption capacity (L/kg).

Freundlich Equation:

In the equation:

Kf represents the adsorption capacity,

1/n is an empirical constant related to adsorption intensity,

Fitting the adsorption data of atrazine for both types of biochar to the above two isothermal adsorption models, the fitting parameters are shown in Table 6. According to the fitting data, the Freundlich equation has a higher correlation coefficient for both types of biochar, indicating that the Freundlich model better describes the adsorption process of atrazine on both types of biochar.

TABLE 6

| Bio-chars | T(K) | Freundlich | Langmuir | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| KF(mg/kg)/(mg/L)1/n | 1/n | R2 | Qmax(mg/kg) | KL (L/mg) | R2 | ||

| C | 288.15 | 1295.794 | 0.415 | 0.987 | 7791.333 | 0.086 | 0.993 |

| 298.15 | 1653.664 | 0.388 | 0.949 | 8279.208 | 0.095 | 0.974 | |

| 308.15 | 1516.75 | 0.460 | 0.969 | 12050.155 | 0.054 | 0.966 | |

| SC | 288.15 | 1192.547 | 0.499 | 0.996 | 9374.140 | 0.079 | 0.979 |

| 298.15 | 1496.740 | 0.455 | 0.975 | 10310.035 | 0.071 | 0.925 | |

| 308.15 | 1573.214 | 0.497 | 0.999 | 10274.348 | 0.106 | 0.973 | |

Freundlich, langmuir isotherm parameters for sorption of atrazine on biochars at different temperatures.

Figures 13, 14 present the adsorption isotherms and Freundlich model fitting curves of the two types of biochar at different temperatures. From these figures, it is evident that for both the original biochar and the acidified biochar, the adsorption capacity increases with rising temperature at the same equilibrium concentration. This indicates that temperature is a factor influencing the ability of biochar to adsorb atrazine; higher temperatures promote the adsorption process. This finding has practical significance for the future application of biochar, suggesting that in regions or seasons with higher temperatures, using biochar to remove atrazine can yield more favorable results.

FIGURE 13

Adsorption isotherm and freundlich curve for atrazine on biochars (SC) at different.

FIGURE 14

Adsorption isotherm and freundlich curve for atrazine on biochars (C) at different temperatures.

The figures also show that at all temperatures, the total adsorption capacity of the acid-modified biochar exceeds that of the original biochar. This phenomenon becomes more pronounced with increasing temperature and higher initial concentrations of atrazine. Under the conditions of 308.15 K and an atrazine concentration of 50 mg/L, the total adsorption capacity of the acid-modified biochar is 1,500 mg/kg higher than that of the original biochar (C). This demonstrates that, on an equal mass basis, acid-modified biochar can adsorb and immobilize more atrazine molecules than the original biochar, especially under conditions of high temperature and high initial atrazine concentration. This suggests that acidification modification effectively enhances the biochar’s adsorption capacity for atrazine. When addressing atrazine pollution, particularly at high concentrations, acid-modified biochar can achieve more optimal results.

The change in free energy during the adsorption of atrazine by biochar is an important parameter reflecting the adsorption capacity. Based on the variation of adsorption free energy, the adsorption mechanism of biochar for atrazine can be inferred. When the change in free energy is less than 40 kJ/mol, the process is considered physical adsorption; otherwise, it is chemical adsorption (Carter et al., 1995).

Gibbs Free Energy:

In the equation:

ΔG is the change in Gibbs free energy (kJ/mol),

ΔH0 is the standard enthalpy change of adsorption (kJ/mol),

ΔS0 is the standard entropy change of adsorption (J/(mol·K)),

R is the universal gas constant (8.314 J/(mol·K)),

TTis the absolute temperature (K),

Kf is the adsorption equilibrium constant derived from the Freundlich isotherm constant.

To determine ΔH0 and ΔS0, a plot of lnKf versus 1/T is created. The slope and intercept of the regression equation from this plot allow for the calculation of ΔH0 and ΔS0. The results are shown in Table 7.

TABLE 7

| Parameters | Temperature (K) | C | SC |

|---|---|---|---|

| ΔG0 (kJ/mol) | 288.15 | −17.170 | −16.971 |

| 298.15 | −18.371 | −18.123 | |

| 308.15 | −18.763 | −18.764 | |

| ΔS0 (J/(mol•K) | 1.035 | 1.207 | |

| ΔH0 (kJ/mol) | −3.213 | −6.879 |

Thermodynamic parameters for the sorption of atrazine on biochars.

From the thermodynamic parameters, we observe that ΔG0 is less than 0, indicating that the adsorption of atrazine by both types of biochar is a spontaneous process. As the temperature increases, the absolute value of ΔG0 also increases, suggesting enhanced spontaneity at higher temperatures. Previous research has found that when the absolute value of ΔG0 for an adsorption reaction falls within the range of 0–20 kJ/mol, the adsorption is primarily physical (Feng et al., 2013). According to Table 7, the absolute values of ΔG0 for both types of biochar at all three temperatures lie within the 0–20 kJ/mol range, indicating that the adsorption of atrazine by both biochars is predominantly a physical adsorption process.

4.3.4 Adsorption mechanism experiment of acid-modified biochar

The experimental results are shown in Figure 15. The adsorption mechanism experiment demonstrates that acid-modified biochar generally exhibits a stronger adsorption capacity for atrazine compared to original biochar. However, under different pH conditions, the adsorption capacities of the two types of biochar change. In this experiment, as pH decreases, the original biochar’s adsorption capacity for atrazine increases. Previous studies have also observed that regular biochar performs better in atrazine adsorption under acidic conditions. This is thought to be due to the high concentration of hydrogen ions in acidic environments, which leads to the protonation of atrazine, promoting the formation of triazine cations. The presence of triazine cations enhances electrostatic attraction between the positively charged pesticide and the negatively charged biochar surface, thereby significantly improving biochar’s adsorption of atrazine (Zheng et al., 2010).

FIGURE 15

The sorption capacity of atrazine on biochars at different temperatures.

In an acidic environment, the surface of regular biochar adsorbs a large amount of H+. Given that atrazine has a pKa of 1.7 and is weakly acidic, it can ionize to release H+ in aqueous solution, acquiring a negative charge. The resulting electrostatic attraction enhances the adsorption capacity of regular biochar in acidic conditions (Zhao et al., 2013). Conversely, under alkaline conditions, the adsorption capacity of acid-modified biochar (SC) decreases. This is due to the adsorption of OH− ions by SC in the alkaline environment, which alters its surface charge. Thus, the surface charge of SC contributes to its superior atrazine adsorption capacity compared to regular biochar (C).

According to experimental data, at pH 7, the adsorption capacity of acid-modified biochar is approximately 700 mg/kg higher than that of regular biochar, due to the combined effects of increased surface area and altered surface charge. At pH 9, the adsorption capacity of SC decreases by about 400 mg/kg, mainly due to surface charge effects. These results suggest that SC’s enhanced adsorption capacity compared to C is primarily due to its increased surface area, porosity, and altered surface charge, with the change in surface charge being the key factor in improving adsorption performance.

In the adsorption process of atrazine by biochar, physical adsorption, chemical adsorption, and ion-exchange adsorption are not isolated phenomena but rather the result of their combined effects. Considering the large surface area and porous nature of biochar, regular biochar primarily adsorbs atrazine through physical adsorption. Since both atrazine and biochar contain polar functional groups, such as hydroxyl and carboxyl groups, which facilitate hydrogen bonding, the formation of hydrogen bonds is possible. If hydrogen bonds are present, dipole-dipole interactions may also contribute to the adsorption process. Some researchers suggest that the ester functional groups on the biochar surface can enable π-bond interactions between atrazine and biochar (Zhang P. et al., 2013), indicating that the adsorption process likely involves van der Waals forces, hydrogen bonds, and dipole interactions.

For acid-modified biochar, the abundance of H+ ions on its surface imparts a high positive charge density, which enhances electrostatic attraction with the weakly acidic atrazine ions. This increased electrostatic attraction provides SC with a superior adsorption performance compared to regular biochar, as it strengthens the overall adsorption effect beyond that of the original biochar.

5 Conclussion

The primary aim of this study was to investigate the adsorption and immobilization capacity of biochar for Cr(VI) and atrazine in soil environments. We specifically focused on acidifying biochar to enhance its adsorption capacity for atrazine and conducted experiments to explain how this modification affects the adsorption mechanism of atrazine. For Cr(VI) adsorption, the study examined the impact of biochar addition to surface soil on Cr(VI) mobility, using simulated acid rain leaching to test the stability of biochar’s adsorption. For atrazine adsorption, we prepared an acid-modified biochar and examined its adsorption effectiveness and mechanisms compared to the original biochar. Soil environments were also simulated to evaluate the practical effectiveness of both types of biochar in immobilizing atrazine in soil. The main conclusions from the experiments are as follows:

Effect on Cr(VI) Migration in Soil: In soil column leaching experiments, we investigated the effect of adding biochar to soil on Cr(VI) migration, particularly by conducting simulated acid rain leaching to further study the immobilization capacity and effectiveness of biochar in soil for Cr(VI). Results indicate that adding only 1% biochar to soil significantly enhances the overall system’s ability to immobilize Cr(VI). Small-particle biochar exhibited a distinct advantage over larger particles, with adsorption capacities approximately three times higher under certain conditions. Additionally, Cr(VI) bound to small-particle biochar demonstrated stability against desorption even under acid rain leaching.

Enhanced Atrazine Adsorption by Acid-modified biochar: The experiments confirmed that acidification enhances the adsorption capacity of biochar for atrazine. Both pre- and post-acidification biochars fit the Freundlich isotherm model, with temperature significantly affecting adsorption capacity, as adsorption increases with temperature. The original biochar aligns with the Elovich kinetic model, while the acid-modified biochar conforms to the pseudo-second-order kinetic model, indicating that acidification has altered the adsorption mechanism. The acid-modified biochar demonstrates superior adsorption capacity for atrazine, primarily due to the increased surface area, pore size, and pore volume resulting from acidification. These structural changes provide more adsorption sites and stronger van der Waals forces. Furthermore, acidification changes the surface charge of biochar, creating a stronger electrostatic attraction with atrazine. This electrostatic force is a key factor behind the enhanced adsorption performance of acid-modified biochar.

6 Future perspectives

Biochar, as an environmentally sustainable method for treating agricultural and forestry waste, demonstrates strong adsorption capacity for soil pollutants when applied, while also serving as a soil amendment that can improve soil physicochemical properties, enhance fertility, reduce nutrient loss, and increase crop yield. However, due to the complexity of soil systems, the widespread application of biochar still requires extensive experimental data for a comprehensive evaluation of its effects.

With the advancement of deep learning techniques, data augmentation has gained significant attention as a means to expand dataset size and improve model generalizability. Within tailored modeling frameworks, deep learning can be employed to integrate hundreds of influencing factors such as climate, soil type, pollutants, microorganisms, and flora and fauna in order to simulate the real-world impacts of biochar on soil environments. This approach will ultimately support a more rigorous assessment of biochar’s suitability for soil applications.

Statements

Data availability statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/supplementary material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Author contributions

MJ: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal Analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Writing – original draft. ZM: Funding acquisition, Project administration, Resources, Supervision, Writing – review and editing.

Funding

The author(s) declared that financial support was received for this work and/or its publication. Cores and Samples Center of Natural Resources, China Geological Survey, Selection, Collection and Service Application Demonstration of Strategic Mineral Physical Geological Data (No: DD20240126).

Conflict of interest

The author(s) declared that this work was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The author(s) declared that generative AI was not used in the creation of this manuscript.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

1

Adriano D. C. Wenzel W. W. Vangronsveld J. Bolan N. (2004). Role of assisted natural remediation in environmental cleanup. Geoderma122, 121–142. 10.1016/j.geoderma.2004.01.003

2

Ahmad M. Lee S. S. Dou X. Mohan D. Sung J. K. Yang J. E. et al (2012). Effects of pyrolysis temperature on soybean stover-and peanut shell-derived biochar properties and TCE adsorption in water. Bioresour. Technol.118536–544. 10.1016/j.biortech.2012.05.042

3

Antal M. J. Allen S. G. Dai X. F. er al Tam M. S. Grønli M. (2000). Attainment of the theoretical yield of carbon from biomass. Industrial Eng. Chem. Res.39 (11), 4024–4031. 10.1021/ie000511u

4

Arshad M. Khan A. H. A. Hussain I. Badar-uz-Zaman M. Anees M. Iqbal M. et al (2017). The reduction of chromium(VI) phytotoxicity and phytoavailability to wheat using biochar and bacteria. Appl. Soil Ecol.11490–98. 10.1016/j.apsoil.2017.02.021

5

Asai H. Samson B. K. Stephan H. M. Songyikhangsuthor K. Homma K. Kiyono Y. et al (2009). Biochar amendment techniques for upland rice production in northern Laos: 1. Soil physical properties, leaf SPAD and grain yield. Field Crops Res.111 (1-2), 81–84. 10.1016/j.fcr.2008.10.008

6

Atkinson C. J. Fitzgerald J. D. Hipps N. A. (2010). Potential mechanisms for achieving agricultural benefits from biochar application to temperate soils: a review. Plant Soil337 (1-2), 1–18. 10.1007/s11104-010-0464-5

7

Beesley L. Dickinson N. (2011). Carbon and trace element fluxes in the pore water of an urban soil following greenwaste compost, woody and biochar amendments, inoculated with the earthworm Lumbricus terrestris. Soil Biol. Biochem.43 (1), 188–196. 10.1016/j.soilbio.2010.09.035

8

Beesley L. Moreno-Jimenez E. Gomez-Eyles J. L. (2010). Effects of biochar and greenwaste compost amendments on mobility, bioavailability and toxicity of inorganic and organic contaminants in a multi-element polluted soil. Environ. Pollut.158 (6), 2282–2287. 10.1016/j.envpol.2010.02.003

9

Brändli R. C. Hartnik T. Henriksen T. Cornelissen G. (2008). Sorption of native polyaromatic hydrocarbons (PAH) to black carbon and amended activated carbon in soil. Chemosphere73 (11), 1805–1810. 10.1016/j.chemosphere.2008.08.034

10

Bridle T. Pritchard D. (2004). Energy and nutrient recovery from sewage sludge via pyrolysis. Water Sci. Technol.50 (9), 169–175. 10.2166/wst.2004.0562

11

Cao X. D. Ma L. N. Gao B. Harris W. (2009). Dairy-manure derived biochar effectively sorbs lead and atrazine. Environ. Sci. Technol.43 (9), 3285–3291. 10.1021/es803092k

12

Carter M. C. Kilduff J. E. Weber J. W. J. (1995). Site energy distribution analysis of preloaded adsorbents. Environ. Sci. Technol.29 (7), 1773–1780. 10.1021/es00007a013

13

Chen B. L. Zhou D. D. Zhu L. Z. (2008). Transitional adsorption and partition of nonpolar and polar aromatic contaminants by biochars of pine needles with different pyrolytic temperatures. Environ. Sci. Technol.42 (14), 5137–5143. 10.1021/es8002684

14

Cheng C. H. Lin T. P. Lehmann J. Fang L. J. Yang Y. W. Menyailo O. V. et al (2014). Soption properties for black carbon (wood char) after long exposure in soilsp. Org. Geochem.70, 53–61. 10.1016/j.orggeochem.2014.02.013

15

Cho Y. M. Ghosh U. Kennedy A. J. Grossman A. Ray G. Tomaszewski J. E. et al (2009). Field application of activated carbon amendment for in-situ stabilization of polychlorinated biphenyls in marine sediment. Environ. Sci. Technol.43 (10), 3815–3823. 10.1021/es802931c

16

Choppala G. Bolan N. Seshadri B. (2013). Chemodynamics of chromium reduction in soils: implications to bioavailability. J. Hazard. Mater.261718–724. 10.1016/j.jhazmat.2013.03.040

17

Cooper R. L. Stoker T. E. Goldman J. M. Er A. Tyrey L. (1996). Effect of atrazine on ovarian function in the rat. Reprod. Toxicol.10 (4), 257–264. 10.1016/0890-6238(96)00054-8

18

Delwiche K. B. Lehmann J. Walter M. T. (2014). Atrazine leaching from biochar-amended soils. Chemosphere95, 346–352. 10.1016/j.chemosphere.2013.09.043

19

DeSisto W. J. Hill N. Beis S. H. Mukkamala S. Joseph J. Baker C. et al (2010). Fast pyrolysis of pine sawdust in a fluidized-bed reactor. Energy Fuels24 (4), 2642–2651. 10.1021/ef901120h

20

Donson S. L. Merritt C. M. Shannahan J. P. Shults C. M. (1999). Low exposure concentrations of atrazine increase male production in daphnia pulicaria. Environ. Toxicol. Chem.18 (7), 1568–1573. 10.1897/1551-5028(1999)018<1568:lecoai>2.3.co;2

21

Downie A. E. Van Zwieten L. Smemik R. J. (2011). Terra preta australis: reassessing the carbon storage capacity of temperate soils. Agric. Ecosyst. Environ.140 (1- 2), 137–147. 10.1016/j.agee.2010.11.020

22

Fellet G. Marchiol L. Delle Vedove G. Peressotti A. (2011). Application of biochar on mine tailings: effects and perspectives for land reclamation. Chemosphere83 (9), 1262–1297. 10.1016/j.chemosphere.2011.03.053

23

Feng Y. F. Dionysiou D. D. Wu Y. H. Zhou H. Xue L. He S. et al (2013). Adsorption of dyestuff from aqueous solutions through oxalic acid-modified swede rape straw: adsorption process and disposal methodology of depleted bioadsorbents. Bioresour. Technol.138, 191–197. 10.1016/j.biortech.2013.03.146

24

Fernández M. D. Cagigal E. Vega M. M. Urzelai A. Babín M. Pro J. et al (2005). Ecological risk assessment of contaminated soils through direct toxicity assessment. Ecotoxicologial. Environ. Saf.62 (2), 174–184. 10.1016/j.ecoenv.2004.11.013

25

Gaskin J. W. Steiner C. Harris K. K. C. Das B. Bibens (2008). Effect of low-temperature pyrolysis conditions on biochar for agricultural use. Trans. Asabe51 (6), 2061–2069. 10.13031/2013.25409

26

Gomez-Eyles J. L. Sizmur T. Collins C. D. Hodson M. E. (2011). Effects of biochar and the earthworm Eisenia fetida on the bioavailability of polycyclic aromatic hydrocarb. Environ. Pollut.159 (2), 616–622. 10.1016/j.envpol.2010.09.037

27

González J. F. Román S. Encinar J. M. Martínez G. (2009). Pyrolysis of various biomass residues and char utilization for the production of activated carbons. J. Anal. Appl. Pyrolysis85 (1-2), 134–141. 10.1016/j.jaap.2008.11.035

28

Graber E. R. Meller Harel Y. Kolton M. Cytryn E. Silber A. Rav David D. et al (2010). Biochar impact on development and productivity of pepper and tomato grown in fertigated soilless media. Plant Soil337 (1-2), 481–496. 10.1007/s11104-010-0544-6

29

Hamer U. Marschner B. Brodowski S. Amelung W. (2004). Interactive priming of black carbon and glucose mineralisation. Org. Geochem.35 (7), 823–830. 10.1016/j.orggeochem.2004.03.003

30

Hu B. Wang K. Wu L. Yu S. H. Antonietti M. Titirici M. M. (2010). Engineering carbon materials from the hydrothermal carbonization process of biomass. Adv. Mater.22 (7), 813–828. 10.1002/adma.200902812

31

Karami N. Clemente R. Moreno-Jiménez E. Lepp N. W. Beesley L. (2011). Efficiency of green waste compost and biochar soil amendments for reducing lead and copper mobility and uptake to ryegrass. J. Hazard. Mater.191 (1-3), 41–48. 10.1016/j.jhazmat.2011.04.025

32

Kasozi G. N. Zimmerman A. R. Nkedi-Kizza P. Gao B. (2010). Catecholand humic acid sorption onto a range of laboratory-produced black carbons (biochars). Environ. Sci. Technol.44 (16), 6189–6195. 10.1021/es1014423

33

Kruse A. Funke A. Titirici M. M. (2013). Hydrothermal conversion of biomass to fuels and energetic materials. Curr. Opin. Chem. Biol.17 (3), 515–521. 10.1016/j.cbpa.2013.05.004

34

Leeuwen J. A. Walnter-Toews D. Abernathy T. Smit B. Shoukri M. (1999). Associations between stomach cancer incidence and drinking water contamination with atrazine and nitrate in Ontario (Canada) agroecosystems, 1987–1991. Int. J. Epidemiol.28 (5), 836–840. 10.1093/ije/28.5.836

35

Lehmann J. Joseph S. (2009). Biochar for environmental management: science and technology. London: Earthscan.

36

Lehmann J. Joseph S. (2012). Biochar for environmental management; science and technology. London: Earthscan.

37

Lehmann J. Rondon M. (2006). Bio-char soil management on highly weathered soils in the humid tropics, biological approaches to sustainable soil systems. Boca Raton, FL: CRC Press, 517–530.

38

Lehmann J. Nguyen B. T. Kinyangi J. Smernik R. Riha S. J. Engelhard M. H. (2008). Long-term black carbon dynamics in cultivated soil. Biogeochemistry89 (3), 295–308. 10.1007/s10533-008-9220-9

39

Liang B. Lehmann J. Solomon D. Kinyangi J. Grossman J. O'Neill B. et al (2006). Black carbon increases cation exchange capacity in soils. Soil Sci. Soc. Am. J.70 (5), 1719–1730. 10.2136/sssaj2005.0383

40

Liu N. Charrua A. B. Weng C. H. Yuan X. L. Ding F. (2015). Characterization of biochars derived from agriculture wastes and their adsorptive removal of atrazine from aqueous solution: a comparative study. Bioresour. Technol.198, 55–62. 10.1016/j.biortech.2015.08.129

41

Major J. Rondon M. Molina D. Riha S. J. Lehmann J. (2010). Maize yield and nutrition during 4 years after biochar application to a Columbian savanna oxisol. Plant Soil333 (1-2), 117–128. 10.1007/s11104-010-0327-0

42

Meyer S. Glaser B. Quicker P. (2011). Technical, economical, and climate-related aspects of biochar production technologies: a literature review. Environ. Sci. Technol.45 (22), 9473–9483. 10.1021/es201792c

43

Mohan D. Pittman C. U. Steele P. H. (2006). Pyrolysis of wood/biomass for bio-oil: a critical review. Energy Fuels20 (3), 848–889. 10.1021/ef0502397

44

Mullen C. A. Boateng A. A. Goldberg N. M. Lima I. M. Laird D. A. Hicks K. B. (2010). Bio-oil and bio-char production from corn cobs and stover by fast pyrolysis. Biomass Bioenergy34 (1), 67–74. 10.1016/j.biombioe.2009.09.012

45

Novak J. M. Busscher W. J. Laird D. L. Ahmedna M. Watts D. W. Niandou M. A. S. (2009). Impact of biochar amendment on fertility of a southeastern coastal plain soil. Soil Sci.174 (2), 105–112. 10.1097/ss.0b013e3181981d9a

46

Poerschmann J. Baskyr I. Weiner B. Koehler R. Wedwitschka H. Kopinke F. D. (2013). Hydrothermal carbonization of olive mill wastewater. Bioresour. Technol.133, 581–588. 10.1016/j.biortech.2013.01.154

47

Pu W. W. Zhang X. L. Xu J. Zhao X. J. Xu X. F. Dong F. et al (2010). Characteristics and impact factors of acid rain in Beijing. J. Appl. Meteorol. Climatol.21(4), 464–472.

48

Raveendran K. Ganesh A. Khilar K. C. (1995). Influence of mineral matter on biomass pyrolysis characteristics. Fuel74 (12), 1812–1822. 10.1016/0016-2361(95)80013-8

49

Renner R. (2007). Rethinking biochar. Environ. Sci. Technol.41 (17), 5932–5933. 10.1021/es0726097

50

Ribas G. Surralles J. Creus A. Xamena N. Marcos R. (1998). Lack of genotoxicity of the herbicide atrazine in cultured human lymphocytes. Toxicol. Environ. Mutagen.416, 93–99. 10.1016/s1383-5718(98)00081-3

51

Rondon M. A. Lehmann J. Ramirez J. Hurtado M. (2007). Biological nitrogen fixation by common beans (Phaseolus vulgaris L.) increases with bio-char additions. Biol. Fertil. Soils43 (6), 699–708. 10.1007/s00374-006-0152-z

52

Samsuri A. W. Sadegh-Zadeh F. Seh-Bardan B. J. (2014). Characterization of biochars produced from oil palm and rice husks and their adsorption capacities for heavy metals. Int. J. Environ. Sci. Technol.11 (4), 967–976. 10.1007/s13762-013-0291-3

53

Sharma R. K. Wooten J. B. Baliga V. L. Lin X. Geoffrey Chan W. Hajaligol M. R. (2004). Characterization of chars from pyrolysis of lignin. Fuel83 (11-12), 1469–1482. 10.1016/j.fuel.2003.11.015

54

Shinogi Y. Yoshida H. Koizumi T. Yamaoka M. Saito T. (2003). Basic characteristics of low-temperature carbon products from waste sludge. Adv. Environ. Res.7 (3), 661–665. 10.1016/s1093-0191(02)00040-0

55

Singh B. P. Hatton B. J. Singh B. Cowie A. L. Kathuria A. (2010). Influence of biochars on nitrous oxide emission and nitrogen leaching from two contrasting soils. J. Environ. Qual.39 (4), 1224–1235. 10.2134/jeq2009.0138

56

Sohi S. P. Krull E. Lopez-Capel E. Bol R. (2010). A review of biochar and its use and function in soil. Adv. Agron.105, 47–82. 10.1016/s0065-2113(10)05002-9

57

Steiner C. de Arruda M. R. Teixeira W. G. Zech W. (2007). Soil respiration curves as soil fertility indicators in perennial central Amazonian plantations treated with charcoal, and mineral or organic fertilisers. Trop. Sci.47 (4), 218–230. 10.1002/ts.216

58

Su H. Fang A. Tsang P. E. Fang J. Zhao D. (2016). Stabilisation of nanoscale Zero—Valent iron with biochar for enhanced transport and in-situ remediation of hexavalent chromium in soil. Environ. Pollut.21494–100. 10.1016/j.envpol.2016.03.072

59

Swan S. H. Kruse R. L. Liu F. Barrd D. B. Drobnis E. Z. Redmon J. B. et al (2003). Semen quality in relation to biomarkers of pesticide exposure. Environ. Health Perspect.111 (12), 1478–1484. 10.1289/ehp.6417

60

Swartjes F. A. (1999). Risk-based assessment of soil and groundwater quality in the Netherlands: standards and remediation urgency. Risk Anal.19 (6), 1235–1249. 10.1111/j.1539-6924.1999.tb01142.x

61

Uchimiya M. Wartelle L. H. Klasson K. T. Fortier C. A. Lima I. M. (2011). Influence of pyrolysis temperature on biochar property and function as a heavy metal sorbent in soil. J. Agric. Food Chem.59 (6), 2501–2510. 10.1021/jf104206c

62

Van Zwieten L. Kimber S. Morris S. Chan K. Y. Downie A. Rust J. et al (2010). Effects of biochar from slow pyrolysis of papermill waste on agronomic performance and soil fertility. Plant Soil327 (1-2), 235–246. 10.1007/s11104-009-0050-x

63

Wang H. L. Lin K. D. Hou Z. N. Richardson B. Gan J. (2010). Sorption of the herbicide terbuthylazine in two New Zealand forest soils amended with biosolids and biochars. J. Soils Sediments10 (2), 283–289. 10.1007/s11368-009-0111-z

64

Wang C. Gu L. Liu X. Zhang X. Cao L. Hu X. (2016). Sorption behavior of Cr(VI) on pineapple-peel-derived biochar and the influence of coexisting pyrene.Int. Biodeterior. & Biodegrad.11178–84. 10.1016/j.ibiod.2016.04.029

65

Wei L. Xu S. Zhang L. Zhang H. Liu C. Zhu H. et al (2006). Characteristics of fast pyrolysis of biomass in a free fall reactor. Fuel Process. Technol.87 (10), 863–871. 10.1016/j.fuproc.2006.06.002

66

Whitman T. Nicholson C. F. Torres D. Lehmann J. (2011). Climate change impact of biochar cook stoves in western kenyan farm households: system dynamics model analysis. Environ. Sci. Technol.45 (8), 3687–3694. 10.1021/es103301k

67

Yang Y. N. Sheng G. Y. Huang M. S. (2006). Bioavailability of diuron in soil containing wheat-straw- derived char. Sci. Total Environ.354 (2-3), 170–178. 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2005.01.026

68

Yang X. B. Ying G. G. Peng P. A. Wang L. Zhao J. L. Zhang L. J. et al (2010). Influence of biochars on plant uptake and dissipation of two pesticides in an agricultural soil. J. Agric. Food Chem.58 (13), 7915–7921. 10.1021/jf1011352

69

Yip K. Tian F. J. Hayashi J. Wu H. (2010). Effect of alkali and alkaline earth metallic species on biochar reactivity and syngas compositions during steam gasification. Energy Fuels24 (1), 173–181. 10.1021/ef900534n

70

Zhang H. Lin K. Wang H. Gan J. (2010). Effect of Pinus radiata derived biochars on soil sorption and desorption of phenanthrene. Environ. Pollut.158 (9), 2821–2825. 10.1016/j.envpol.2010.06.025

71

Zhang H. Xu R. K. Yuan J. H. (2011). The forms of alkalis in the biochar produced from crop residues at different temperatures. Bioresour. Technol.102 (3), 3488–3497. 10.1016/j.biortech.2010.11.018

72

Zhang A. F. Bian R. J. Pan G. X. Cui L. Hussain Q. Li L. et al (2012a). Effects of biochar amendment on soil quality, crop yield and greenhouse gas emission in a Chinese rice paddy:A field study of 2 consecutive rice growing cycles. Field Crop Res.12, 153–160. 10.1016/j.fcr.2011.11.020

73

Zhang A. F. Liu Y. M. Pan G. X. Hussain Q. Li L. Zheng J. et al (2012b). Effect of biochar amendment on maize yield and greenhouse gas emissions from a soil organic carbon poor calcareous loamy soil from central China plain. Plant Soil351 (1-2), 263–275. 10.1007/s11104-011-0957-x

74

Zhang A. F. Bian R. J. Hussaina Q. Li L. Pan G. Zheng J. et al (2013). Change in net global warming potential of a rice-wheat cropping system with biochar soil amendment in a rice paddy from China. Agriculture. Agric. Ecosyst. Environ.173, 37–45. 10.1016/j.agee.2013.04.001

75

Zhang P. Sun H. W. Yu L. Sun T. (2013). Adsorption and catalytic hydrolysis of carbaryl and atrizine on pig manure-derived biochars: impact of structural properties of biochars. J. Hazard. Mater.244-245, 217–224. 10.1016/j.jhazmat.2012.11.046

76

Zhao X. Ouyang W. Hao F. Lin C. Wang F. Han S. et al (2013). Properties comparison of biochars from corn straw with different retreatment and sorption behavior of atrazine. Bioresour. Technol.147, 338–344. 10.1016/j.biortech.2013.08.042

77

Zheng W. Guo M. Chow T. Bennett D. N. Rajagopalan N. (2010). Sorption properties of greenwaste biochar for two triazine pesticides. J. Hazard. Mater.181 (1-3), 121–126. 10.1016/j.jhazmat.2010.04.103

78

Zhou Z. L. Shi D. J. Qiu Y. P. Sheng G. D. (2010). Sorptive domains of pine chars as probed by benzene and nitrobenzene. Environ. Pollut.158 (1), 201–206. 10.1016/j.envpol.2009.07.020

Summary

Keywords

acidification, atrazinatrazine, biochar, cr(VI), soil contamination

Citation

Jing M and Ma Z (2026) Study on the adsorption of Cr(VI) and atrazine by biochar. Front. Earth Sci. 13:1714988. doi: 10.3389/feart.2025.1714988

Received

16 October 2025

Revised

12 December 2025

Accepted

16 December 2025

Published

05 February 2026

Volume

13 - 2025

Edited by

Ramanathan Alagappan, Independent Researcher, Tiruchirappalli, India

Reviewed by

Ahmed Abdelhafez, The New Valley University, Egypt

Yuexing Wei, Taiyuan University of Technology, China

Updates

Copyright

© 2026 Jing and Ma.

This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Zhaoyang Ma, mzy130682@163.com

†These authors have contributed equally to this work and share first authorship

Disclaimer

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.