Abstract

The Xiaotazigou gold deposit is located in the eastern section of the Chifeng–Chaoyang gold metallogenic belt on the northern margin of the North China Craton. In this study, rare earth and trace element compositions of ores and host rocks, together with sulfur isotope data, were applied to constrain the geochemical characteristics of ore-forming fluids and the sources of ore-forming materials. The results show that the ores are enriched in light rare earth elements (LREE) and display negative Eu anomalies, with Hf/Sm, Nb/La, and Th/La ratios all <1. These features indicate that the ore-forming fluids were Cl-rich, reducing, medium–low temperature NaCl–H2O–CO2 hydrothermal solutions. Pyrite from the ores yields Co/Ni ratios >1, suggesting a magmatic–hydrothermal origin. Variations in Y/Ho and Zr/Hf ratios, coupled with relatively stable Nb/Ta ratios, imply that the hydrothermal system was influenced by fluid mixing with meteoric water during evolution. The δ34S values of pyrite (2.67‰–3.70‰, avg. 3.14‰) are close to mantle-derived sulfur, indicating a dominant mantle source for the ore-forming materials. Moreover, similar rare earth element distribution patterns and trace element geochemical behaviors between ores, monzogranite, and gneiss suggest that the granitoids and gneiss also contributed essential material to the mineralization. Integrating geochemical data and regional tectonic setting, the Xiaotazigou gold deposit is classified as an orogenic gold deposit formed in an intracontinental orogenic regime after the collision between the North China Craton and the Siberian Plate. This study provides new constraints on ore genesis and contributes to understanding gold metallogeny in the northern margin of the North China Craton.

1 Introduction

The North China Craton (NCC) is one of the oldest continental nuclei in the world and has undergone a complex tectonic evolution involving multiple collisional and accretionary events. Its northern margin represents a key metallogenic domain, hosting numerous gold deposits that collectively form the Chifeng–Chaoyang gold belt. This belt has been recognized as one of the most important gold-producing provinces in China, and is therefore a crucial natural laboratory for investigating the genesis of orogenic gold deposits in an intracontinental setting. The Xiaotazigou gold deposit is situated in the eastern part of this metallogenic belt. Since the 1950s, geological surveys have revealed more than 200 gold occurrences in the area, including deposits such as Jinchanggouliang, Dongwujiazi, and Xiaotazigou (Poulsen et al., 1990) (Figure 1c). Although the Xiaotazigou deposit contains proven reserves of approximately 4 tonnes of gold, its scientific significance goes far beyond its economic importance. The deposit provides an excellent opportunity to investigate fluid evolution, material sources, and tectonic controls on gold mineralization in the northern NCC.

FIGURE 1

(a) Tectonic location map of the study area; (b) Simplified geological map of the Chifeng-Chaoyang region (modified after Mao et al., 2003); (c) Geological map of the Xiaotazigou gold deposit.

Previous studies on the Xiaotazigou and nearby deposits have mainly focused on fluid inclusions and stable isotopes (Park et al., 2008; Li et al., 2010). Fluid inclusion data suggest homogenization temperatures of 174 °C–348 °C and salinities of 2.06–11.72 wt% NaCleqv, pointing to NaCl–H2O–CO2 magmatic fluids. Hydrogen–oxygen isotopic compositions indicate a mixture of magmatic and meteoric water sources. However, these studies are largely descriptive and leave several critical questions unresolved. First, the chemical composition and evolution of the ore-forming fluids remain poorly constrained, and the mechanisms responsible for gold precipitation are not well understood. Second, the relative contribution of mantle versus crustal sources to ore-forming materials is still debated. Third, there has been no comprehensive attempt to integrate trace element and sulfur isotope evidence into a unified genetic model. Globally, rare earth elements (REE) and trace elements have been proven to be powerful tracers of fluid chemistry, fluid–rock interaction, and material sources in mineralized systems (Michard and Albarède, 1986; Bau et al., 2003; Mao et al., 2009). Their relatively immobile behavior during hydrothermal processes makes them particularly useful for distinguishing magmatic and crustal contributions. Sulfur (S) isotopes, on the other hand, act as a powerful tracer, revealing the sources of ore-forming fluids in gold deposits. They help decipher the physical-chemical conditions under which gold was transported and deposited. An integrated study of REE, trace elements, and sulfur isotopes is therefore essential for building a more complete understanding of ore genesis.

In this study, we present new S isotopes, REE and trace element data from ores, gneisses, and granitoids in the Xiaotazigou district, together with sulfur isotope data from pyrite. By combining these datasets with existing geological and tectonic information, we aim to determine the relative contributions of mantle and crustal components to the ore-forming system, establish a refined genetic model for the Xiaotazigou gold deposit; and place this model into a regional tectonic and metallogenic framework with implications for gold exploration along the northern margin of the NCC.

2 Geological setting

2.1 Regional geology

The Xiaotazigou gold deposit is situated on the northern margin of the North China Craton (NCC), at the junction between the Inner Mongolia Uplift and the Yanliao Depression Zone, bounded by the Chifeng–Kaiyuan and Chengde–Beipiao faults (Figure 1a). From the Paleozoic to the early Mesozoic orogeny, the NCC experienced multiple large-scale collisional and accretionary events. During the late Paleozoic, the NCC collided and accreted with the Siberian Craton, and subsequently, under a north–south compressional regime, interacted with the Yangtze Craton, resulting in deformation of the sedimentary cover, including widespread intraplate folding and faulting (Tang, 1990; Ames et al., 1993; Li, 1994). In the Mesozoic, within a compressional orogenic setting, lithospheric thinning facilitated the ascent of mantle-derived magmas into the deep crust, triggering widespread granitoid intrusion, volcanic activity, and large-scale metallogenic events (Jia et al., 2011). This complex tectono-magmatic evolution created favorable conditions for the formation of hundreds of gold deposits of varying scales along the northern NCC, accompanied by numerous Fe, Cu, and Mo deposits.

Regionally, Archean metamorphic rocks of the Jianping Group, widely exposed in the Chifeng-Chaoyang area, (Jia et al., 2011), represent an ancient crustal sequence and serve as the primary host rocks for gold mineralization (Figure 1b). These metamorphic rocks are dominated by gneisses, diorite–amphibolites, and banded magnetite–quartzites. Intrusive rocks are primarily granitoids, and faults are well-developed, with major NE- and N–S-trending structures. In the northern part of the region, the Early Yanshanian Jianggoushan pluton exhibits a close spatiotemporal and genetic relationship with regional gold mineralization. This pluton is predominantly composed of monzogranite and quartz monzonite. Numerous gold deposits, including Dongwujiazi, Beidi, and the Xiaotazigou deposit investigated in this study, are distributed within 5–8 km south of this pluton. The Beidashan pluton, which occurs as a stock south of the Jianggoushan pluton, represents a southward extension of the Jianggoushan intrusive system into the Xiaotazigou area. (Li et al., 2010). Industrially significant gold veins in the Xiaotazigou deposit are all hosted within a 0.5–1.5 km zone south of this pluton, indicating a strong genetic relationship between the plutonic intrusion and gold mineralization in the region.

2.2 Deposit geology

The exposed stratigraphy of the Xiaotazigou mining area is dominated by metamorphic rocks of the Archean Jianping Group Xiaotazigou Formation, including biotite–hornblende monzogranitic gneiss, biotite monzogranitic gneiss, hornblende monzogranitic gneiss, diorite–amphibolite interlayered with banded magnetite–quartzite, and lens-shaped diorite porphyry bodies. This formation constitutes the primary host rock for gold mineralization in the area (Figure 2a). Fault structures are well-developed throughout the mining district. Near east–west trending faults, NE-to ENE-trending faults, and NNW-trending faults are the main ore-controlling structures, with the NNW-trending faults interpreted as post-mineralization fractures. In the northern part of the district, the Beidashan monzogranite pluton is exposed, with most gold veins occurring along its southern margin. Polymetallic sulfide veins are locally observed in this rock mass (Figure 2b). Minor intrusions of porphyritic rocks, including syenite porphyry, diorite (or diorite porphyry), and quartz porphyry, are also present. Based on cross-cutting relationships, the quartz porphyry and diorite veins are pre-mineralization intrusions, whereas syenite porphyry represents post-mineralization intrusion.

FIGURE 2

Mineral assemblages of the ores from the Xiaotazigou gold deposit. (a) Field observation of the No. 1 vein in the 211 m middle section of the underground tunnel in Xiaotazigou mining area. (b) Field observation of Beidashan in the northern part of Xiaotazigou Mining Area. (c,d) Pyrite-quartz type ore, predominantly composed of quartz and pyrite. (e) Paragenetic association of sphalerite, chalcopyrite, and galena. (f) Chalcopyrite, galena, sphalerite, and native gold developed within fractures of pyrite. Abbreviations: Ccp - chalcopyrite; Gn - galena; Py - pyrite; Sp - sphalerite.

Currently, over 20 gold-bearing veins have been identified in the mining area, among which veins No. 1, 4, 5, and 6 are of economic significance. The majority of veins exhibit a NE-trending orientation, dipping northwest at angles between 64° and 86°. The largest vein, No. 1, has been traced over 1,200 m by trenching and deep drilling. Ore types are predominantly sulfide-bearing quartz veins (Figures 2c,d), with pyrite as the principal metallic mineral, accompanied by chalcopyrite, galena, and sphalerite. Ore textures include brecciated, inclusion, and replacement–dissolution structures, while ore fabrics are mainly veinlet, massive, and disseminated (Figures 2e,f). Gold occurs primarily as fracture-hosted mineralization. Alteration of the surrounding rocks is well-developed and includes silicification, sericitization, chloritization, and, carbonatization.

3 Samples and analytical methods

To better characterize the geochemical features of the ore-forming fluids and material sources of the Xiaotazigou gold deposit, the following samples were selected for further analysis. Ores were collected from the mid-section (−211 m) of the underground workings along Vein No. 1. Biotite–amphibole monzogranitic gneisses were taken from both sides of Vein No. 1 at the same −211 m level, and monzogranites were obtained from the Beidashan monzogranite pluton in the northern part of the mining area.

3.1 ICP-MS trace element analyses

Rare earth and trace element analysis of whole rock were conducted on Elan DRC-e ICP–MS at the Harbin Natural Resources Comprehensive Survey Center, China Geological Survey. The detailed sample-digesting procedure was as follows: (1) Sample powder (200 mesh) were placed in an oven at 105 °C for drying of 12 h; (2) 50 mg sample powder was accurately weighed and placed in a Teflon bomb; (3) 1 mL HNO3 and 1 mL HF were slowly added into the Teflon bomb; (4) Teflon bomb was putted in a stainless steel pressure jacket and heated to 190 °C in an oven for >24 h; (5) After cooling, the Teflon bomb was opened and placed on a hotplate at 140 °C and evaporated to incipient dryness, and then 1 mL HNO3 was added and evaporated to dryness again; (6) 1 mL of HNO3, 1 mL of MQ water and 1 mL internal standard solution of 1 ppm In were added, and the Teflon bomb was resealed and placed in the oven at 190 °C for >12 h; (7) The final solution was transferred to a polyethylene bottle and diluted to 100 g by the addition of 2% HNO3.

3.2 Sulfur isotope analyses

Sulfur isotope analyses were conducted at the Tianjin Center, China Geological Survey. Pyrite samples were first purified to >99% and ground to 200 mesh. For analysis, approximately 15 mg of sample powder was weighed into a tin capsule with ∼10 mg of tungstic oxide (WO3) as an accelerator. The mixture was flash-combusted at 1800 °C in an Elementar Vario Micro Cube elemental analyzer coupled to a Delta V Plus mass spectrometer. The released SO2 gas was purified by a He carrier stream and separated via a trap-and-purge method before isotopic measurement. The results were normalized against the international standard CDT (Cañon Diablo Troilite), with an analytical precision better than ±0.2‰ (2σ).

4 Results

4.1 Rare earth element geochemistry

The rare earth element (REE) compositions of ore, monzogranite, and gneiss from the Xiaotazigou mining area are summarized in Table 1. All data were normalized to C1 chondrite values (Boynton, 1984), and the resulting REE distribution patterns are shown in Figure 3.

TABLE 1

| Rock type | Ore | Monzogranite | Gneiss | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sample No. | XTZ01 | XTZ02 | XTZ03 | XTZ04 | XTZ07 | XTZ08 | XTZ09 | XTZ10 | XTZ11 | XTZ012 | XTZ013 |

| La | 6.63 | 6.60 | 7.86 | 5.76 | 16.80 | 20.20 | 18.40 | 19.90 | 15.40 | 10.80 | 34.00 |

| Ce | 9.02 | 9.25 | 9.05 | 8.24 | 20.8 | 25.6 | 23.8 | 31.05 | 33.20 | 22.10 | 56.90 |

| Pr | 1.03 | 1.04 | 0.92 | 0.86 | 2.83 | 3.72 | 3.32 | 3.73 | 4.66 | 3.32 | 6.74 |

| Nd | 4.37 | 4.26 | 4.17 | 3.62 | 10.40 | 14.20 | 14.90 | 14.2 | 19.40 | 14.90 | 25.60 |

| Sm | 0.95 | 0.80 | 0.92 | 0.88 | 1.81 | 2.76 | 3.30 | 3.54 | 3.64 | 3.30 | 4.38 |

| Eu | 0.21 | 0.16 | 0.19 | 0.18 | 0.41 | 0.67 | 0.61 | 0.72 | 0.72 | 0.74 | 0.86 |

| Gd | 0.79 | 0.67 | 0.73 | 0.69 | 1.44 | 2.24 | 1.92 | 2.14 | 2.93 | 2.61 | 3.65 |

| Tb | 0.13 | 0.10 | 0.08 | 0.09 | 0.19 | 0.34 | 0.31 | 0.26 | 0.42 | 0.40 | 0.44 |

| Dy | 0.70 | 0.55 | 0.54 | 0.61 | 0.96 | 1.80 | 1.93 | 1.43 | 2.34 | 2.14 | 2.39 |

| Ho | 0.13 | 0.10 | 0.15 | 0.12 | 0.18 | 0.33 | 0.31 | 0.21 | 0.43 | 0.40 | 0.46 |

| Er | 0.35 | 0.32 | 0.28 | 0.26 | 0.51 | 0.90 | 0.82 | 0.62 | 1.20 | 1.07 | 1.30 |

| Tm | 0.054 | 0.042 | 0.044 | 0.042 | 0.074 | 0.15 | 0.11 | 0.09 | 0.18 | 0.16 | 0.20 |

| Yb | 0.34 | 0.25 | 0.32 | 0.27 | 0.46 | 0.92 | 0.77 | 0.57 | 1.06 | 0.97 | 1.25 |

| Lu | 0.076 | 0.063 | 0.072 | 0.079 | 0.098 | 0.16 | 0.14 | 0.11 | 0.17 | 0.17 | 0.21 |

| Y | 3.27 | 2.89 | 2.05 | 2.78 | 5.70 | 9.03 | 9.25 | 8.85 | 11.00 | 9.88 | 11.80 |

| ∑REE | 28.05 | 27.10 | 27.38 | 24.48 | 62.66 | 83.02 | 79.89 | 87.42 | 96.75 | 72.96 | 150.18 |

| LREE | 22.21 | 22.11 | 23.11 | 19.54 | 53.05 | 67.15 | 64.33 | 73.14 | 77.02 | 55.16 | 128.48 |

| HREE | 5.84 | 4.99 | 4.27 | 4.94 | 9.61 | 15.87 | 15.56 | 14.28 | 19.73 | 17.80 | 21.70 |

| LREE/HREE | 3.80 | 4.44 | 5.42 | 3.95 | 5.52 | 4.23 | 4.13 | 5.12 | 3.90 | 3.10 | 5.92 |

| (La/Yb)N | 13.99 | 18.94 | 17.62 | 15.30 | 26.20 | 15.75 | 17.14 | 25.04 | 10.42 | 7.99 | 19.51 |

| (La/Sm)N | 4.51 | 5.33 | 5.52 | 4.23 | 5.99 | 4.72 | 3.60 | 3.63 | 2.73 | 2.11 | 5.01 |

| (Gd/Yb)N | 1.92 | 2.22 | 1.89 | 2.11 | 2.59 | 2.01 | 2.06 | 3.11 | 2.29 | 2.23 | 2.42 |

| Y/Ho | 25.15 | 28.90 | 13.67 | 23.17 | 31.67 | 27.36 | 29.84 | 42.14 | 25.58 | 24.70 | 25.65 |

| δEu | 0.72 | 0.65 | 0.68 | 0.68 | 0.75 | 0.80 | 0.68 | 0.74 | 0.65 | 0.74 | 0.64 |

| δCe | 0.76 | 0.78 | 0.69 | 0.81 | 0.68 | 0.67 | 0.69 | 0.82 | 0.95 | 0.90 | 0.87 |

REE composition of ores, monzogranite, and gneiss in the Xiaotazigou gold deposit.

FIGURE 3

Chondrite-normalized REE patterns of the (a) ores and (b) monzogranite and gneiss from the Xiaotazigou gold deposit (normalization values from Boynton, 1984).

Oresfrom Vein No. 1 exhibit relatively uniform total REE contents (∑REE = 24.48–28.05 ppm, average 26.75 ppm), with LREEs ranging from 19.54 to 23.11 ppm and HREEs from 4.27 to 5.84 ppm. The LREE/HREE ratios (3.80–5.42) and LaN/YbN values (13.99–18.94) indicate pronounced LREE enrichment and right-inclined REE patterns (Figure 3a). LREE fractionation is significant (LaN/SmN = 4.23–5.52), whereas HREE fractionation is weak (GdN/YbN = 1.89–2.22). Europium anomalies (δEu = 0.65–0.72) are strongly negative, while Ce anomalies (δCe = 0.69–0.81) are minor.

Monzogranitesdisplay higher ∑REE (62.66–87.42 ppm, average 78.25 ppm) with LREEs of 53.05–73.14 ppm and HREEs of 9.61–15.87 ppm. The LREE/HREE ratios (4.13–5.52) and LaN/YbN values (15.75–26.20) indicate strong LREE enrichment. They exhibit pronounced negative Eu anomalies (δEu = 0.68–0.80) but minor Ce anomalies (δCe = 0.67–0.82) (Figure 3b).

Gneissesshow the highest ∑REE (72.96–150.18 ppm, average 106.63 ppm), with LREEs of 55.16–128.48 ppm and HREEs of 17.80–21.70 ppm, LREE/HREE ratios of 3.10–5.92, and LaN/YbN values of 7.99–19.51. Negative Eu anomalies are evident (δEu = 0.64–0.74), whereas Ce anomalies remain minor (δCe = 0.87–0.95) (Figure 3b).

4.2 Trace element geochemistry

The trace element compositions are summarized in Table 2. The data were normalized to primitive mantle values, and the resulting spider diagrams are shown in Figure 4. The geochemical behavior of the ore closely resembles that of the associated monzogranite and gneiss, being enriched in large-ion lithophile elements (LILEs) such as Cs, Rb, and Ba, as well as in La, while showing relative depletion in high-field-strength elements (HFSEs) such as Nb, Ta, Ti, and P. In the ores, the trace element ratios Hf/Sm, Th/La, Nb/La, Y/Ho, Co/Ni, Nb/Ta, Zr/Hf, and Th/U range from 0.58 to 0.91, 0.21 to 0.27, 0.32 to 0.39, 13.67 to 28.90, 1.64 to 4.06, 16.00 to 20.36, 20.46 to 61.15, and 5.07 to 6.82, respectively.

TABLE 2

| Rock type | Ore | Monzogranite | Gneiss | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sample No. | XTZ01 | XTZ02 | XTZ03 | XTZ04 | XTZ07 | XTZ08 | XTZ09 | XTZ10 | XTZ11 | XTZ012 | XTZ013 |

| Cs | 1.32 | 0.36 | 0.87 | 1.02 | 0.14 | 0.13 | 0.17 | 0.74 | 3.04 | 0.70 | 1.15 |

| Rb | 95.60 | 18.50 | 81.60 | 97.60 | 38.60 | 52.10 | 30.40 | 29.80 | 56.60 | 23.10 | 47.30 |

| Ba | 314.00 | 105.00 | 203.00 | 272.00 | 1008.00 | 1690.00 | 1177.00 | 1055.00 | 203.00 | 146.00 | 960.00 |

| Th | 1.80 | 1.50 | 1.66 | 1.42 | 1.20 | 1.40 | 1.13 | 1.36 | 1.60 | 1.10 | 1.70 |

| U | 0.27 | 0.22 | 0.32 | 0.28 | 0.18 | 0.16 | 0.11 | 0.31 | 0.63 | 0.11 | 0.31 |

| Nb | 2.61 | 2.08 | 2.91 | 2.24 | 2.35 | 3.26 | 3.12 | 3.45 | 4.84 | 3.12 | 6.45 |

| Ta | 0.14 | 0.13 | 0.16 | 0.11 | 0.10 | 0.20 | 0.13 | 0.15 | 0.34 | 0.24 | 0.36 |

| La | 6.63 | 6.60 | 7.86 | 5.76 | 16.80 | 20.20 | 18.40 | 19.90 | 15.40 | 10.80 | 34.00 |

| Ce | 9.02 | 9.25 | 9.05 | 8.24 | 20.80 | 25.60 | 23.80 | 31.05 | 33.20 | 22.10 | 56.90 |

| Sr | 86.80 | 96.80 | 83.45 | 88.42 | 376.00 | 445.00 | 293.00 | 262.00 | 83.40 | 115.00 | 533.00 |

| Nd | 4.37 | 4.26 | 4.17 | 3.62 | 10.40 | 14.20 | 14.90 | 14.2 | 19.40 | 14.90 | 25.60 |

| P | 480.02 | 523.66 | 542.43 | 503.26 | 480.02 | 523.66 | 493.45 | 508.36 | 1309.15 | 336.01 | 1003.68 |

| Zr | 23.70 | 9.41 | 23.50 | 37.30 | 64.10 | 42.90 | 39.60 | 44.21 | 39.80 | 45.50 | 47.50 |

| Hf | 0.86 | 0.46 | 0.82 | 0.61 | 2.13 | 1.71 | 1.63 | 1.74 | 1.70 | 1.89 | 1.13 |

| Sm | 0.95 | 0.80 | 0.92 | 0.88 | 1.81 | 2.76 | 3.30 | 3.54 | 3.64 | 3.30 | 4.38 |

| Eu | 0.21 | 0.16 | 0.19 | 0.18 | 0.41 | 0.67 | 0.61 | 0.72 | 0.72 | 0.74 | 0.86 |

| Ti | 872.20 | 516.20 | 614.36 | 406.35 | 323.68 | 305.69 | 355.70 | 416.42 | 2097.90 | 1678.32 | 3056.93 |

| Gd | 0.79 | 0.67 | 0.73 | 0.69 | 1.44 | 2.24 | 1.92 | 2.14 | 2.93 | 2.61 | 3.65 |

| Tb | 0.13 | 0.10 | 0.08 | 0.09 | 0.19 | 0.34 | 0.31 | 0.26 | 0.42 | 0.40 | 0.44 |

| Y | 3.27 | 2.89 | 2.05 | 2.78 | 5.70 | 9.03 | 9.25 | 8.85 | 11.00 | 9.88 | 11.80 |

| Yb | 0.34 | 0.25 | 0.32 | 0.27 | 0.46 | 0.92 | 0.77 | 0.57 | 1.06 | 0.97 | 1.25 |

| Lu | 0.08 | 0.06 | 0.07 | 0.08 | 0.10 | 0.16 | 0.14 | 0.11 | 0.17 | 0.17 | 0.21 |

| Co | 114.00 | 93.00 | 131.00 | 74.80 | 11.10 | 10.10 | 46.60 | 84.60 | 3850.00 | 524.00 | 51.10 |

| Ni | 28.10 | 29.80 | 57.00 | 45.50 | 2.74 | 2.71 | 2.70 | 4.78 | 84.60 | 106.00 | 20.10 |

| Hf/Sm | 0.91 | 0.58 | 0.89 | 0.69 | 1.18 | 0.62 | 0.49 | 0.49 | 0.47 | 0.57 | 0.26 |

| Th/La | 0.27 | 0.23 | 0.21 | 0.25 | 0.07 | 0.07 | 0.06 | 0.07 | 0.10 | 0.10 | 0.05 |

| Nb/La | 0.39 | 0.32 | 0.37 | 0.39 | 0.14 | 0.16 | 0.17 | 0.17 | 0.31 | 0.29 | 0.19 |

| Co/Ni | 4.06 | 3.12 | 2.30 | 1.64 | 4.05 | 3.73 | 17.26 | 17.70 | 45.51 | 4.94 | 2.54 |

| Nb/Ta | 18.64 | 16.00 | 18.19 | 20.36 | 23.50 | 16.30 | 24.00 | 23.00 | 14.24 | 13.00 | 17.92 |

| Zr/Hf | 27.56 | 20.46 | 28.66 | 61.15 | 30.09 | 25.09 | 24.29 | 25.41 | 23.41 | 24.07 | 42.04 |

| Th/U | 6.67 | 6.82 | 5.19 | 5.07 | 6.67 | 8.75 | 10.27 | 4.39 | 2.54 | 10.00 | 5.48 |

Trace element composition of ores, monzogranite, and gneiss in the Xiaotazigou gold deposit.

FIGURE 4

Primitive mantle-normalized trace element spider diagrams of the (a) ores and (b) monzogranite and gneiss from the Xiaotazigou gold deposit (normalization values from Sun and McDonough, 1989).

4.3 Sulfur isotopes

The sulfur isotope compositions of pyrite from Vein No. 1 of the Xiaotazigou gold deposit are presented in Table 3. The δ34S values of pyrite vary within a narrow range of 2.67‰–3.70‰, with an average of 3.14‰.

TABLE 3

| Sampling location/Sample ID | Mineral analyzed | δ34S (‰) | Average δ34S (‰) |

|---|---|---|---|

| −211 m Level, No. 1 vein/XTZ03 | Pyrite | 3.70 | 3.14 |

| −211 m Level, No. 1 vein/XTZ04 | Pyrite | 3.34 | |

| −211 m Level, No. 1 vein/XTZ04 | Pyrite | 2.84 | |

| −211 m Level, No. 1 vein/XTZ05 | Pyrite | 2.67 |

Sulfur isotope composition of regional representative gold ores in the Xiaotazigou gold deposit.

5 Discussion

5.1 Genesis of granite and gneiss

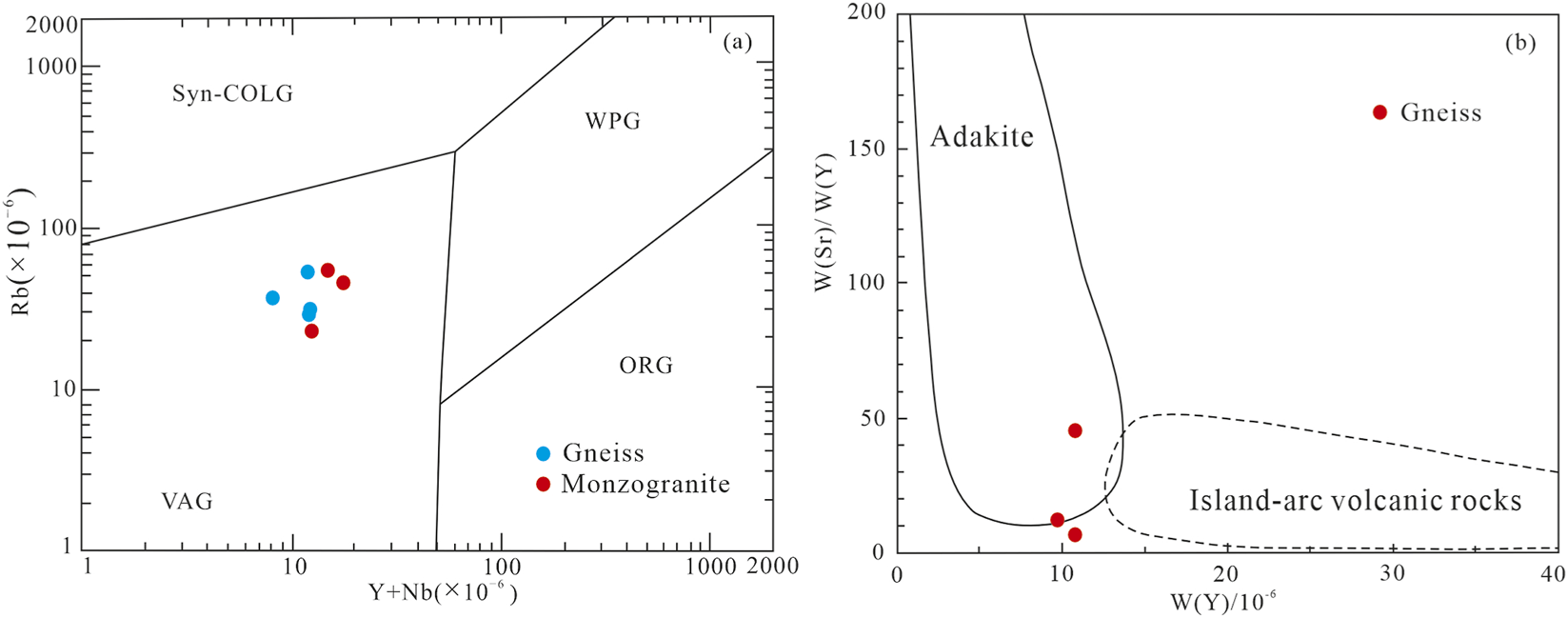

Geochemically, the monzogranitesexhibit light REE enrichment and heavy REE depletion, with pronounced negative anomalies in Nb, Ta, Ti, and P (Figure 4b). These characteristics indicate fractional crystallization of minerals such as apatite and ilmenite. Furthermore, the monzogranites possess relatively high Sr contents (262–445 ppm) but low Y (9.88–11.8 ppm) and Yb (0.97–1.25 ppm) concentrations, suggesting that the magmatic source was likely relatively mafic igneous rocks and/or involved contributions from mantle-derived components. The rocks show weak negative Eu anomalies, enrichment in Ba, and insignificant Th anomalies (Figure 4b), consistent with features of I-type granites. On the (Y + Nb)–Rb tectonic discrimination diagram (Figure 5a), all monzogranitesplot within the field of volcanic arc granites, further indicating that their formation was likely related to orogenic processes (Miao et al., 2003).

FIGURE 5

Y vs. Sr/Y (a) and (Y + Nb) vs. Rb (b) diagrams for the monzogranite and gneiss from the Xiaotazigou gold deposit.

The gneisses are characterized by low concentrations of Nb, Ta, and Sr Their chondrite-normalized REE patterns are strongly right-sloping, indicating significant fractionation between LREEs and HREEs. Pronounced negative Eu anomalies are observed, suggesting plagioclase retention in the source region, which is consistent with formation under low-pressure conditions given the pressure-sensitive stability of plagioclase. The rocks exhibit variable Sr/Y ratios (7.58–45.17), depletion in HREEs and Y, and plot within or near the adakite field on the Sr/Y–Y diagram (Figure 5b). These features imply that their protoliths likely belong to the Archean TTG (tonalite–trondhjemite–granodiorite) suite. Geochemically, the gneisses are enriched in LILEs (e.g., Ba, Rb) but depleted in HFSEs (e.g., Nb, Ta, P, Ti), reflecting an arc magmatic affinity. This interpretation is supported by their placement in the volcanic arc granite field on the (Y + Nb)–Rb diagram (Figure 5a), suggesting a genetic link to orogenic events.

5.2 Nature of ore-forming fluids

The study of the geochemical characteristics of ore-forming fluids and the sources of ore-forming materials represents a key focus in modern ore deposit research. Rare earth elements, due to their geochemical stability, can effectively trace fluid–rock interactions during mineralization (Henderson, 1984; Li et al., 2019; 2020) and help constrain ore-forming processes (Schade et al., 1989; Zhao and Jiang, 2007). Moreover, in hydrothermal deposits, the ionic radii of key ions such as Cu2+, Zn2+, and Fe2+ are much larger than those of REE3+, making the latter less likely to enter mineral lattices, thus preserving original REE signatures in the ore (Bi et al., 2004; Mills and Elderfield, 1995). Previous studies have shown that REEs and HFSEs are often concentrated in fluid inclusions within sulfide minerals in hydrothermal systems (Bi et al., 2004; Mao et al., 2006). Consequently, the composition of REEs and HFSEs in pyrite can reflect the characteristics of the ore-forming fluids (Bi et al., 2004; Mao et al., 2006). In the Xiaotazigou gold deposit, the total REE content in pyrite is relatively low (24.47–28.05 ppm), with moderate fractionation between LREEs and HREEs (LREE/HREE = 3.80–5.51; LaN/YbN = 13.99–18.94; Table 1), and the normalized REE patterns are strongly right-inclined (Figure 3a), indicating LREE enrichment during mineralization.

Experimental and theoretical studies suggest that Cl and F exhibit differential complexing behavior with REEs: Cl preferentially complexes with LREEs, while F favors HREEs (Flynn and Burnham, 1978; Alderton et al., 1980; Hass et al., 1995). HFSEs also show contrasting behavior in Cl-versus F-rich fluids. In Cl-rich fluids, LREEs are enriched and ratios such as Hf/Sm, Nb/La, and Th/La are generally <1, whereas in F-rich fluids, HFSEs are enriched, and these ratios exceed 1 (Oreskes and Einaudi, 1990; Ayers and Watson, 1993; Keppler, 1996). This feature is consistent with the fact that the fluid phase components of fluid inclusions in many typical gold deposits within the same mineralization belt generally contain Cl-, such as the Anjiayingzi gold deposit (Sun, 2013), Honghuagou gold deposit (Tang, 2018), Jinchanggouliang gold deposit (Hou, 2011), etc. Moreover, on the spider web diagram of trace elements (Figure 4), it is shown that the significant deficiency of high-field-strength elements (Nb, Ta, Ti, etc.) in pyrite also rules out the possibility that the ore-forming fluid is of the F system (Li et al., 2022). In Xiaotazigou pyrite, the ratios Nb/La (0.32–0.39), Th/La (0.21–0.27), and Hf/Sm (0.58–0.91) are all <1, consistent with LREE enrichment and indicating that the ore-forming fluids were predominantly Cl-rich. Fluid inclusion studies (Li et al., 2010) suggest temperatures of 174 °C–348 °C and salinities of 2.06–11.72 wt% NaCl equivalent, with the presence of CO2, indicating that the mineralizing fluid system was a Cl-rich, medium-to low-temperature NaCl–H2O–CO2 hydrothermal system.

The redox state of the mineralizing fluid can be inferred from Eu and Ce anomalies in REEs. In reducing conditions, Eu2+ is preferentially separated from trivalent REEs, while Ce remains as Ce3+ and does not show significant fractionation (Ma et al., 2013). In contrast, oxidizing environments typically produce negative Ce anomalies and minimal Eu anomalies (An and Zhu, 2014; Chen et al., 2013). In the Xiaotazigou deposit, pyrite exhibits pronounced negative Eu anomalies (δEu = 0.65–0.72) with no significant Ce anomalies (Figure 3a), and field observations confirm the absence of sulfate minerals indicative of strongly oxidizing conditions (e.g., barite, gypsum). These observations indicate that the ore-forming fluids were reducing. Impurity elements in pyrite, particularly Co and Ni, and the Co/Ni ratio, are valuable indicators of ore genesis (Brill, 1989; Gregory et al., 2015). Sedimentary pyrite typically exhibits Co/Ni < 1 (average 0.63) (Price, 1972), hydrothermal pyrite ranges from 1.17 to 5 (average 1.7), and volcanogenic pyrite generally has Co/Ni > 1, concentrated between 5 and 10 (average 8.7) (Campbell and Ethier, 1984; Bajwah et al., 1987; Bralia et al., 1979). In Xiaotazigou, Co/Ni ratios in pyrite range from 1.64 to 4.06 (Table 2), consistent with a magmatic–hydrothermal origin (Meng et al., 2018). The pyrite compositions also fall within the porphyry-type field in the Ni–Co diagram (Figure 6), further supporting a magmatic–hydrothermal source for the fluids.

FIGURE 6

Ni–Co diagram of pyrite from the Xiaotazigou gold deposit (after Deditius et al., 2013; Cioacă et al., 2014; Keith et al., 2016).

Elemental ratios such as Y/Ho, Zr/Hf, and Nb/Ta, which have similar ionic radii and charges, are generally stable in a closed hydrothermal system but can vary significantly due to fluid mixing or wall-rock interaction (Bau and Dulski, 1995; Yaxley et al., 1998; Douville et al., 1999). In Xiaotazigou pyrite, Y/Ho (13.67–28.90) and Zr/Hf (20.46–61.15) show wide variations, while Nb/Ta (16.00–20.36) is relatively stable, suggesting that the ore-forming fluids underwent fluid–rock interaction or mixing during evolution. Hydrogen and oxygen isotope testing and analysis show that the δD value of quartz minerals in the ore samples of the Xiaotazigou gold deposit ranges from −82.61‰ to −91.79‰, and the δ18O value ranges from 5.55‰ to 7.56‰. The δD values of the Dongwujiazi gold deposit in the neighboring area range from −89.58‰ to −92.66‰, and the δ18O values range from −1.40‰ to −0.23‰. It is believed that the ore-forming fluids of these two gold deposits both originate from magmatic water and are mixed with atmospheric precipitation (Zhang et al., 2007; Park et al., 2008), indicating that the initial mineralizing fluid was magmatic in origin with some incorporation of meteoric water.

Overall, the ore-forming fluids of the Xiaotazigou gold deposit were Cl-rich, medium-to low-temperature NaCl–H2O–CO2 hydrothermal fluids, reducing in nature, and derived primarily from magmatic sources with minor meteoric water input. This phenomenon can be explained by differences in mineralization depth and distance from intrusive bodies between the Xiaotazigou gold deposit and the neighboring Dongwujiazi gold deposit. The Xiaotazigou deposit is located approximately 1 km from the Beidashan monzogranite intrusion, which has a surface exposure of less than 1 km2, and its orebodies are hosted in the metamorphic rocks of the Xiaotazigou Formation. In contrast, the Dongwujiazi deposit lies about 6 km from a quartz monzonite intrusion to the north, with its orebodies also occurring within the Xiaotazigou Formation metamorphic rocks. The mineralization depth of the Xiaotazigou deposit ranges from 2.8 to 4.72 km (Park et al., 2008), indicating a relatively short migration distance for the ore-forming fluids. It is thus inferred that the ore-forming fluids at Xiaotazigou were predominantly derived from magmatic water associated with the monzogranite, with a minor component of meteoric water. In comparison, the Dongwujiazi deposit formed at a shallower depth of 1.39–1.84 km (Park et al., 2008) and is situated farther from the intrusion horizontally. The extended lateral migration and ascent of magmatic fluids in this setting resulted in the incorporation of a significantly higher proportion of meteoric water.

5.3 Sources of ore-forming materials

Sulfur isotope analysis of the Xiaotazigou gold ore reveals a narrow range of δ34S values (2.67‰–3.70‰; mean = 3.14‰) with a small variation (1.07‰). These values are close to the typical mantle sulfur range (δ34S = −3‰–3‰; Chaussidon and Lorand, 1990), suggesting a predominantly deep mantle origin for the sulfur. As shown in Figure 7, the δ34S values of the Xiaotazigou deposit fall within a relatively tight range, similar to those reported from other regional gold deposits such as the Jinchanggouliang (−7.21‰–1.27‰), Erdaogou (−2.2‰–3.4‰), and Dongwujiazi (1.91‰–3.14‰) deposits. The consistently mantle-like sulfur isotope signatures among these deposits indicate a shared deep magmatic source for the sulfur. Furthermore, tellurium (Te) is generally a dispersed element in the crust, and its local enrichment is widely interpreted as indicative of mantle-derived inputs (Du, 1996; Mao and Li, 2004). It is transported via mantle-derived volatile exhalations despite its low solubility in water (Du, 1996). Electron microprobe analysis has identified the presence of Te in electrum from the No. 1 vein of the Xiaotazigou deposit (Li et al., 2010), providing further evidence for the involvement of mantle-derived components in the mineralization process. Meanwhile, the similarity of REE and trace element patterns between ore, granitic intrusions, and host gneiss indicates elemental inheritance from both the intrusive rocks and country rocks (Figures 3, 4). The ore-forming fluids likely leached REEs and other trace elements during fluid–rock interaction, producing geochemical signatures that overlap those of the host rocks. Such dual inheritance is a common feature of orogenic gold systems where syn-to post-collisional granitic magmatism interacts with ancient metamorphic basement. As illustrated in the δEu–δCe, ΣREE–LREE/HREE, Nb–Ta, and Zr–Hf diagrams (Figure 8), the oreplot in similar ranges or exhibit trends consistent with those of monzogranite and gneiss. This further supports the interpretation that the ore-forming materials of the Xiaotazigou gold deposit were likely derived from the monzogranite and gneiss.

FIGURE 7

δ34S (‰) in this study, marine and continental rocks.

FIGURE 8

Covariation diagrams of δEu vs. δCe (a), ΣREE vs. LREE/HREE (b), Nb/Ta (c), and Zr/Hf (d) for the ores, monzogranite, and gneiss from the Xiaotazigou gold deposit.

5.4 Genetic implications

From the Late Indosinian to Middle Jurassic, northern China, including the study area, experienced intracontinental collisional orogeny, with the southward subduction of the Mongolia–Okhotsk Ocean at ∼160 Ma providing the primary tectonic driver (Mao et al., 2005; Zhao et al., 2004). During the compressional stage, crustal thickening concentrated energy and facilitated the formation of mineralized magmatic–hydrothermal systems. Subsequent extensional stages triggered lithospheric thinning and ascent of mineralized granitic magmas along faults, where fluids were enriched and precipitated in favorable structural sites, forming numerous gold deposits in the region, including Dongwujiazi, Beidi, Huojiazi, and Xiaotazigou.

Field observations indicate that Xiaotazigou gold mineralization is structurally controlled by the Chifeng–Kaiyuan and Chengde–Beipiao faults, which provided conduits for deep-seated ore-forming fluids. Ore bodies are confined to compressional–shear fractures, with zoned hydrothermal alteration of the wall rocks progressing outward from silicification to sericitization, chloritization, and carbonate alteration. Mineral assemblages are relatively simple, dominated by pyrite with subordinate chalcopyrite, sphalerite, and galena, and quartz as the primary gangue mineral with minor calcite. These geological features closely resemble those of typical orogenic gold deposits worldwide (Table 4).

TABLE 4

| Metallogenic region | Chifeng-chaoyang area, northern margin of north China craton | Qinling orogen | Sierra foothills and klamath mts |

|---|---|---|---|

| Deposit name | Xiaotazigou | Ma’anqiao, liba | Alleghany, grass valley, French gulch |

| Host rock | Neoarchean xiaotazigou formation metamorphic rocks | Devonian flysch clastic rocks | Paleozoic to jurassic metamorphic series |

| Ore-control structure | Secondary faults | Secondary ductile-brittle faults | Brittle-ductile shear zones |

| Magmatic rock | Yanshanian granites | Indosinian-yanshanian granites | Jurassic-early cretaceous granites |

| Ore body characteristic | Vein-type | Vein-type, stratiform-like | Stockwork vein-type |

| Ore type | Quartz-vein type | Quartz-vein type, altered rock type | Quartz-vein type, altered rock type |

| Metallic minerals | Pyrite, chalcopyrite, pyrrhotite, galena, sphalerite | Pyrite, chalcopyrite, pyrrhotite, galena, sphalerite, native gold | Pyrite, chalcopyrite, native gold, galena, sphalerite, electrum |

| Wall-rock alteration | Silicification, sericitization, chloritization, carbonatization | Silicification, sericitization, chloritization, carbonatization | Silicification, sericitization, sericitization, chloritization, carbonatization |

| Ore-forming fluid | Low-medium T (174 °C–348 °C), low salinity (2.06–11.72 wt%) H2O-CO2-NaCl system | Low-medium T (146 °C–467 °C), low salinity (2.2–10.0 wt%) H2O-CO2-NaCl system | Low-medium T (200 °C–300 °C), low salinity H2O-CO2±CH4 system |

| References | Li et al. (2010) | Li et al., 2001; Wei, 2007; Li et al., 2021 | Landefeld, 1988; Groves et al., 1998; Goldfarb et al., 2001 |

Comparison of geological characteristics between the Xiaotazigou gold deposit and typical orogenic gold deposits worldwide.

Fluid inclusion studies indicate that homogenization temperature and salinity are negatively correlated (Figure 9), consistent with fluid evolution patterns observed in classic orogenic gold systems (Chen et al., 2007). Proximity to the Dongwujiazi gold deposit (∼7 km to the northeast) with a similar tectonic setting suggests that Xiaotazigou shares the same orogenic gold-forming mechanism, confirming its classification as an orogenic.

FIGURE 9

Relationship between homogenization temperature and salinity for fluid inclusions in quartz from the Xiaotazigou gold deposit (data from Xu et al., 2010).

6 Conclusion

Pyrite from the Xiaotazigou deposit is enriched in LREE and shows negative Eu anomalies with Hf/Sm, Nb/La, and Th/La <1, indicating Cl-rich, reducing, medium–low temperature NaCl–H2O–CO2 ore-forming fluids. Variations in Y/Ho and Zr/Hf ratios suggest mixing with meteoric water.

Sulfur isotope data (δ34S = 2.67‰–3.70‰, avg. 3.14‰) indicate a dominant mantle source of sulfur, while similar REE and trace element patterns between ores, granitoids, and gneisses show that crustal rocks also contributed ore materials.

The Xiaotazigou deposit is an orogenic gold deposit formed in an intracontinental orogenic regime following the collision between the North China Craton and the Siberian Plate, providing important implications for gold metallogeny in the northern margin of the NCC.

Statements

Data availability statement

The datasets presented in this study can be found in online repositories. The names of the repository/repositories and accession number(s) can be found in the article/supplementary material.

Author contributions

HY: Writing – original draft, Conceptualization, Investigation. LF: Project administration, Writing – review and editing. YB: Writing – review and editing, Validation. QW: Validation, Writing – review and editing. ZW: Validation, Writing – review and editing. YZ: Validation, Writing – review and editing. JS: Writing – review and editing, Software, Supervision.

Funding

The author(s) declared that financial support was received for this work and/or its publication. This research was funded by the China Geological Survey project of China (DD20240206703, DD20230395).

Acknowledgments

We acknowledge all people who contributed to field investigation.

Conflict of interest

Authors YB, QW, ZW, and YZ were employed by Liaoning Nonferral Geology 109 Team Co., Ltd.

The remaining author(s) declared that this work was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The author(s) declared that generative AI was not used in the creation of this manuscript.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

1

Alderton D. H. M. Pearce J. A. Potts P. J. (1980). Rare Earth element mobility during granite alteration: evidence from southwest England. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett.49, 149–165. 10.1016/0012-821x(80)90157-0

2

Ames L. Tilton G. R. Zhou G. Z. (1993). Timing of collision of the Sino-Korean and yangtze cratons: U-Pb zircon dating of coesite-bearing eclogites. Geology21, 339–342. 10.1130/0091-7613(1993)021<0339:tocots>2.3.co;2

3

An F. Zhu Y. F. (2014). Trace element geochemistry of the Baogutu gold deposit in West junggar, Xinjiang. Acta Petrologica Mineralogica33 (2), 329–342.

4

Ayers J. C. Watson E. B. (1993). Apatite/fluid partitioning of rare-earth elements and strontium: experimental results at 1.0 GPa and 1000°C and application to models of fluid-rock interaction. Chem. Geol.110, 299–314. 10.1016/0009-2541(93)90259-l

5

Bajwah Z. U. Seccombe P. K. Offler R. (1987). Trace element distribution Co:Ni ratios and genesis of the big cadia iron–copper deposit, New South Wales, Australia. Miner. Deposita22, 292–300. 10.1007/bf00204522

6

Bau M. Dulski P. (1995). Comparative study of yttrium and rare-earth element behaviours in fluorine-rich hydrothermal fluids. Contributions Mineralogy Petrology119 (2), 213–223. 10.1007/bf00307282

7

Bau M. Romer R. L. Lüders V. Dulski P. (2003). Tracing element sources of hydrothermal mineral deposits: REE and Y distribution and Sr-Nd-Pb isotopes in fluorite from MVT deposits in the pennine orefield, England. Miner. Deposita38, 992–1008. 10.1007/s00126-003-0376-x

8

Bi X. Hu R. Peng J. Wu K. (2004). Trace element geochemistry of pyrite and its implication for the nature of ore-forming fluid. Bull. Mineralogy, Petrology Geochem.23 (1), 1–4. 10.3969/j.issn.1007-2802.2004.01.001

9

Boynton W. W. (1984). “Geochemistry of the rare earth elements: meteorite studies,” in Rare Earth element geochemistry. Editor HendersonP. (Amsterdam: Elsevier), 63–114.

10

Bralia A. Sabatini G. Troja F. (1979). A revaluation of the Co/Ni ratio in pyrite as geochemical tool in ore genesis problems. Miner. Deposita14 (3), 353–374. 10.1007/bf00206365

11

Brill B. A. (1989). Trace-element contents and partitioning of elements in ore minerals from the CSA Cu-Pb-Zn deposit, Australia. Can. Mineral.27 (2), 263–274.

12

Campbell F. A. Ethier V. G. (1984). Nickel and cobalt in pyrrhotite and pyrite from the Faro and sullivan orebodies. Can. Mineral.22, 503–506.

13

Chaussidon M. Lorand J. P. (1990). Sulphur isotope composition of orogenic spinel lherzolite massifs from Ariege (North-Eastern pyrenees, France): an ion microprobe study. Geochimica Cosmochimica Acta54 (10), 2835–2846. 10.1016/0016-7037(90)90018-g

14

Chen Y. J. Ni P. Fan H. R. Pirajno F. Lai Y. Su W. C. et al (2007). Fluid inclusion study of different types of gold deposits. Acta Petrol. Sin.23 (9), 2085–2108. 10.3969/j.issn.1000-0569.2007.09.009

15

Chen B. H. Wang Z. L. Li H. L. Li J. K. Li J. L. Wang G. Q. (2013). Ore-forming fluid evolution of the taishang gold deposit, jiaodong peninsula: constraints from REE and trace element compositions of auriferous pyrite. Acta Petrol. Sin.30 (9), 2518–2532.

16

Cioacă M. E. Munteanu M. Qi L. Costin G. (2014). Trace element concentrations in porphyry copper deposits from metaliferi Mountains, Romania: a reconnaissance study. Ore Geol. Rev.63, 22–39. 10.1016/j.oregeorev.2014.04.016

17

Deditius A. Chryssoulis S. Li J. W. Ma C. Q. Parada M. A. et al (2013). Pyrite as a record of hydrothermal fluid evolution in a porphyry copper system: a SIMS/EMPA trace element study. Geochimica Cosmochimica Acta104, 42–62. 10.1016/j.gca.2012.11.006

18

Douville E. Bienvenu P. Charlou J. L. Donval J. P. Fouquet Y. Appriou P. et al (1999). Yttrium and rare-earth elements in fluids from various deep-sea hydrothermal systems. Geochimica Cosmochimica Acta63 (5), 627–643. 10.1016/s0016-7037(99)00024-1

19

Du L. T. (1996). The relationship between crustal fluids and mantle fluids. Earth Sci. Frontiers3 (4), 172–180.

20

Flynn T. R. Burnham C. W. (1978). An experimental determination of rare earth partition coefficients between chloride containing vapor phase and silicate melts. Geochimica Cosmochimica Acta42, 685–701. 10.1016/0016-7037(78)90087-X

21

Goldfarb R. J. Groves D. I. Gardoll S. (2001). Orogenic gold and geologic time: a global synthesis. Ore Geol. Rev.18, 1–75. 10.1016/s0169-1368(01)00016-6

22

Gregory D. D. Large R. R. Halpin J. A. Baturina E. L. Lyons T. W. Wu S. et al (2015). Trace element content of sedimentary pyrite in black shales. Econ. Geol.110, 1389–1410. 10.2113/econgeo.110.6.1389

23

Groves D. I. Goldfarb R. J. Gebre-Mariam M. Hagemann S. Robert F. (1998). Orogenic gold deposits: a proposed classification in the context of their crustal distribution and relationship to other gold deposit types. Ore Geol. Rev.13, 7–27. 10.1016/s0169-1368(97)00012-7

24

Hass J. R. Shock E. L. Sassani D. C. (1995). Rare earth elements in hydrothermal systems: estimates of standard partial molal thermodynamic properties of aqueous complexes of the rare earth elements at high pressures and temperatures. Geochimica Cosmochimica Acta59 (21), 4329–4350. 10.1016/0016-7037(95)00314-p

25

Henderson P. (1984). Rare Earth element geochemistry. Amsterdam: Elsevier Science Publishers, 510.

26

Hou W. R. (2011). Contrast Study on the Hadamengou Gold Deposit and Jinchangouliang Gold Deposit, Inner Mongolia. Beijing: Chinese Academy of Geological Sciences, 213.

27

Jia S. S. Wang E. D. Fu J. F. Song J. C. Xi X. F. (2011). The differences of geological characteristics and the Unity of mineralization in the major gold concentrated areas of eastern Hebei-Western Liaoning. Acta Geol. Sin.85 (9), 1493–1506.

28

Keith M. Haase K. M. Klemd R. Krumm S. Strauss H. (2016). Systematic variations of trace element and sulfur isotope compositions in pyrite with stratigraphic depth in the skouriotissa volcanic–hosted massive sulfide deposit, troodos ophiolite, Cyprus. Chem. Geol.423, 7–18. 10.1016/j.chemgeo.2015.12.012

29

Keppler H. (1996). Constraints from partitioning experiments on the composition of subduction zone fluids. Nature380, 237–240. 10.1038/380237a0

30

Landefeld L. A. (1988). “The geology of the mother Lode-gold belt sierra Nevada foothills metamorphic belt, California,” in Bi-centennial gold 88, extended abstracts, oral programme (Tulsa, OK: The Pacific Section American Association of Petroleum Geologist), 22, 167–172.

31

Li Z. X. (1994). Collision between the north and south China blocks: a crustal-detachment model for suturing in the region east of the tanlu fault. Geology22, 739–742. 10.1130/0091-7613(1994)022<0739:cbtnas>2.3.co;2

32

Li F. Zou X. Gao J. Lu Y. Zhang Y. (2001). On the rapid-positioning and prediction for micro-dissemination type (sedimentary rock host) gold deposit (ore bodies), Ma'anqiao. Northwest. Geol.34 (1), 27–63. 10.3969/j.issn.1009-6248.2001.01.004

33

Li B. L. Xu Q. L. Zhang H. Chang G. L. (2010). Characteristics and genesis of ore-forming fluids of No.1 vein in xiaotazigou gold deposit, chaoyang city, Liaoning Province. Earth Sci. Front.17 (2), 295–305.

34

Li J. Cai W. Y. Li B. Wang K. y. Liu H. l. Konare Y. et al (2019). Paleoproterozoic SEDEX-type stratiform mineralization overprinted by Mesozoic vein-type mineralization in the qingchengzi Pb-Zn deposit, northeastern China. J. Asian Earth Sci.184, 104009. 10.1016/j.jseaes.2019.104009

35

Li J. Wang K. Y. Cai W. Y. Sun F. y. Liu H. l. Fu L. j. et al (2020). Triassic gold–silver metallogenesis in qingchengzi orefield, north China craton: perspective from fluid inclusions, REE and H–O–S–Pb isotope systematics. Ore Geol. Rev.121, 103567. 10.1016/j.oregeorev.2020.103567

36

Li J. Song M. C. Yu J. T. Bo J. W. Zhang Z. L. Liu X. (2022). Genesis of Jinqingding gold deposit in eastern Jiaodong Peninsula: constrain from trace elements of sulfide ore and wall-rock. Geol. Bull. China41 (6), 1010–1022. 10.12097/j.issn.1671-2552.2022.06.009

37

Li B. Zhu L. M. Ding L. L. (2021). Geology, isotope geochemistry, and ore genesis of the liba gold deposit in the western qinling orogen, China. Acta Geol. Sin. Engl. Ed.95 (2), 427–448. 10.19762/j.cnki.dizhixuebao.2020243

38

Ma Y. Du X. Zhang Z. Xing S. Zou Y. Li B. et al (2013). REE geochemical characteristics of qingchengzi stratiform/veined Pb-Zn ore district. Mineral. Deposits32 (6), 1236–1248. 10.3969/j.issn.0258-7106.2013.06.010

39

Mao J. W. Li X. F. (2004). Mantle derived fluids in relation to ore-forming and oil-forming processes. Mineral. Deposits23 (4), 520–532.

40

Mao J. W. Li Y. Q. Goldfarb R. (2003). Fluid inclusion and noble gas studies of the dongping gold deposit, Hebei province, China: a mantle connection for mineralization?Econ. Geol.98, 517–534. 10.2113/98.3.517

41

Mao J. Xie G. Zhang Z. Li X. Wang Y. Zhang C. et al (2005). Mesozoic large-scale metallogenic pulses in north China and corresponding geodynamic settings. Acta Petrol. Sin.21 (1), 169–188. 10.3969/j.issn.1000-0569.2005.01.017

42

Mao G. Hua R. Gao J. Zhao K. Long G. Lu H. et al (2006). REE and trace element features of gold-bearing pyrite in Jinshan gold deposit, Jiangxi province. Mineral. Deposits25 (4), 412–426. 10.3969/j.issn.0258-7106.2006.04.006

43

Mao G. Z. Hua R. M. Gao J. F. Li W. Zhao K. Long G. et al (2009). Existing forms of REE in gold-bearing pyrite of the jinshan gold deposit, Jiangxi province, China. J. Rare Earths27 (6), 1079–1087. 10.1016/s1002-0721(08)60392-0

44

Meng Y. M. Hu R. Z. Huang X. W. Gao J. F. Qi L. Lyu C. (2018). The relationship between stratabound pb-zn-ag and porphyry-skarn Mo mineralization in the laochang deposit, southwestern China: constraints from pyrite Re–Os isotope, sulfur isotope, and trace element data. J. Geochem. Explor.194, 218–238. 10.1016/j.gexplo.2018.08.008

45

Miao L. Fan W. Zhai M. Qiu Y. Mcnaughton N. Groves D. (2003). Zircon SHRIMP U-Pb geochronology of the granitoid intrusions from jinchanggouliang-erdaogou gold orefield and its significance. Acta Petrol. Sin.19 (1), 70–80. 10.3969/j.issn.1000-0569.2003.01.008

46

Michard A. Albarède F. (1986). The REE content of some hydrothermal fluids. Chem. Geol.55 (1–2), 51–60. 10.1016/0009-2541(86)90127-0

47

Mills R. Elderfield H. (1995). Rare earth element geochemistry of hydrothermal deposits from the active TAG mound, 26°N mid-atlantic ridge. Geochimica Cosmochimica Acta59 (17), 3511–3524. 10.1016/0016-7037(95)00224-n

48

Oreskes N. Einaudi M. T. (1990). Origin of rare earth element-enriched hematite breccias at the Olympic Dam Cu-U-Au-Ag deposit, roxby downs, South Australia. Econ. Geol.85 (1), 1–28. 10.2113/gsecongeo.85.1.1

49

Park S.-s. Shi L. Yu Z. Zhang B. (2008). Geochemical characteristics of xiaotazigou-dongwujiazi gold orefield in Chaoyang, Liaoning. Geol. Resour.17 (3), 188–195. 10.3969/j.issn.1671-1947.2008.01.002

50

Poulsen K. H. Taylor B. E. Mortensen J. K. (1990). “Observations on gold deposits in north China platform,” in Current research, part A (Ottawa: Geological Survey of Canada), 33–44. Paper 90–1A.

51

Price B. J. (1972). Minor elements in pyrites from the smithers map area, British Columbia and exploration applications of minor element studies. Vancouver, BC: University of British Columbia, 83–91. M.Sc. thesis.

52

Schade J. Cornell D. H. Theart H. F. J. (1989). Rare-earth element and isotopic evidence for the genesis of the prieska massive sulfide deposit, South Africa. Econ. Geol.84 (1), 49–63. 10.2113/gsecongeo.84.1.49

53

Sun Z. J. (2013). Study on gold deposits mineralization in chifeng-chaoyang region, northern margin of north China craton. Changchun: Jilin University, 1–194. Ph.D. thesis.

54

Sun S. S. McDonough W. F. (1989). “Chemical and isotopic systematics of oceanic basalts: implications for mantle composition and processes,”. Editors SaundersA. D.NorryM. J. (London: Geological Society, London, Special Publications), 42, 313–345. 10.1144/gsl.sp.1989.042.01.19

55

Tang K. D. (1990). Tectonic development of Paleozoic fold belts at the north margin of the Sino-Korean craton. Tectonics9, 249–260. 10.1029/tc009i002p00249

56

Tang Q. Y. (2018). Geological characteristics and Genesis of Inner Mongolia Honghuagou Gold deposit. Shijiazhuang: Hebei GEO University, 67.

57

Wei L. (2007). Preliminary study on the ore-forming fluids of baguamiao gold deposit, Shaanxi province. Acta Petrol. Sin.23 (9), 2257–2262. 10.3969/j.issn.1000-0569.2007.09.023

58

Xu Q. Li B. Xue H. Wan D. Shen X. (2010). Ore-forming fluid characteristics and genesis of dongwujiazi gold deposit in chaoyang city, Liaoning Province. Northwest. Geol.43 (3), 75–84. 10.3969/j.issn.1009-6248.2010.03.010

59

Yaxley G. M. Green D. H. Kamenetsky V. (1998). Carbonatite metasomatism in the southeastern Australian lithosphere. J. Petrology39, 1917–1930. 10.1093/petrology/39.11.1917

60

Zhang B. W. (2007). Geochemical characteristics and genesis of the xiaotazigou gold deposit, Liaoning. Changchun: Jilin University, p72.

61

Zhao K. D. Jiang S. Y. (2007). Rare-earth element and yttrium analyses of sulfides from the dachang Sn-polymetallic ore field, Guangxi province, China: implication for ore genesis. Geochem. J.41 (2), 121–134. 10.2343/geochemj.41.121

62

Zhao Y. Zhang S. Xu G. Yang Z. Hu J. (2004). Major tectonic event in the Yanshanian intraplate deformation belt in the Jurassic. Geol. Bull. China23 (9), 854–863. 10.3969/j.issn.1671-2552.2004.09.006

Summary

Keywords

ore-forming fluids, orematerial source, rare earth elements, sulfur isotopes, trace elements, Xiaotazigou gold deposit

Citation

Yuan H, Fu L, Bai Y, Wei Q, Wang Z, Zhao Y and Sun J (2026) Genesis of the Xiaotazigou gold deposit in the northern margin of the north China craton: constraints from sulfur isotopes, rare earth elements, and trace elements. Front. Earth Sci. 13:1739854. doi: 10.3389/feart.2025.1739854

Received

05 November 2025

Revised

04 December 2025

Accepted

11 December 2025

Published

12 January 2026

Volume

13 - 2025

Edited by

Jenni Lie, Widya Mandala Catholic University Surabaya, Indonesia

Reviewed by

Zheming Zhang, Sinosteel, China

Jiepeng Tian, Shandong Jianzhu University, China

Updates

Copyright

© 2026 Yuan, Fu, Bai, Wei, Wang, Zhao and Sun.

This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Jingyao Sun, 18346123881@163.com

Disclaimer

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.