Abstract

With the continuous increase in coal mining depth and intensity, the stress distribution in surrounding rock during multi-working face coordinated mining has become increasingly complex, significantly affecting the safe and efficient extraction of coal resources. This study takes the 22,214 and 22,215 working faces in Liuta Mine as the engineering background and employs FLAC3D numerical simulation to analyze the evolution of mining-induced stress and overburden fracture characteristics during coordinated mining of two adjacent faces. By establishing the stress superposition intensity index Iσ and the plastic zone evolution index IP, the mechanisms of stress superposition and cumulative plastic damage in multi-working face mining were quantitatively revealed. Simulation results indicate that the stress and plastic zone in the first-mined face exhibit a symmetric distribution, with the peak abutment pressure increasing as the face advances, reaching a maximum stress concentration factor of 1.8. In contrast, the subsequent face, influenced by the adjacent goaf and the coal pillar and key stratum structure, shows significant asymmetry in both strike and dip stress distributions. The stress concentration factor on the coal pillar side reaches a maximum of 2.3, and the stress increment within 0–40 m ahead of the face is approximately 1.3–1.4 times that of the first-mined face. The multi-working face advance process demonstrates a three-stage evolution characterized by low superposition, medium superposition, and strong superposition. At an advance distance of 2,400 m, corresponding to the transition of the main key stratum from a suspended state to a fractured voussoir beam structure, the stage represents a strong superposition zone of stress and plastic deformation. In this zone, the plastic area on the coal pillar side connects with the goaf of the first-mined face, leading to a significant increase in the risk of surrounding rock instability. The study elucidates the mechanisms of stress transfer and plastic zone interconnection during coordinated multi-working face mining and identifies the strong superposition stage as a critical period for rockburst prevention and control. Accordingly, a combined strategy of differentiated support and directional pressure relief is proposed to maintain surrounding rock stability, with emphasis on monitoring the strong plastic deformation superposition zone. The findings provide a theoretical reference for mining-induced stress analysis, stability control of surrounding rock, and rockburst prevention under similar geological and mining conditions.

1 Introduction

With the continuous increase in mining depth and intensity of coal resources in China, the deep high-stress environment and intensive mining activities have led to increasingly complex stress states of underground surrounding rock. The strong disturbance of the mining-induced stress field and the large-scale movement of overlying strata pose greater challenges to the stability control of surrounding rock (Hongpu and Gao, 2024; Feng et al., 2025; Yang et al., 2021). Intensive multi-face mining, as a primary method to enhance resource recovery and production efficiency, achieves high output and efficiency but also results in a mining-induced stress field distribution characterized by significant spatial correlation and temporal dynamics. In particular, mutual disturbances between closely spaced working faces can induce stress superposition and transfer, leading to regional stress concentration that severely affects the stability of surrounding rock (Zhang et al., 2021; Wang et al., 2023a). Therefore, an in-depth study of the spatiotemporal evolution of mining-induced stress and fracture zones under coordinated multi-face mining conditions is of great significance for revealing the mechanisms of surrounding rock instability, optimizing mining design, and achieving safe and efficient extraction.

In recent years, as mining depth and production intensity have continued to increase, especially with the large-scale application of high-intensity mining technologies, the distribution of mining-induced stress fields has become more complex (Zhang et al., 2024a; Zhang et al., 2023a; Qian and Jialin, 2019), and the strong mining-induced stress formed around working faces has a significant impact on the stability of the surrounding rock (Yan and Xue, 2024; Heping et al., 2015). Under repeated mining conditions, the layout of multiple working faces and their successive extraction subject the overburden to multiple mining-induced disturbances, causing continuous redistribution and superposition of the stress field and leading to increasingly pronounced cumulative damage in the surrounding rock (Minghui et al., 2023; Guo, 2023). In terms of repeated mining and coordinated multi-face extraction, Gao and Hui (2017) analyzed the spatiotemporal evolution of surface subsidence and ponding areas induced by multi-seam mining in the Huainan mining area, while Yan et al. (2023), using a combination of physical modeling and numerical simulation, revealed the dynamic behavior of overburden movement and deformation during repeated extraction of closely spaced coal seams. The stress redistribution induced during mining has also attracted wide attention (Zhang and Zhou, 2022). Tang and Junyi (2019) used numerical simulation to analyze the repeated mining behavior in a mine in the Yushen mining area of northern Shaanxi, and Wang et al. (2023b) investigated the instability mechanisms of deep stopes under repeated mining by integrating theoretical analysis, similarity simulation and numerical modeling. In the field of overburden movement and rock-mass control, similarity model tests have been employed to study the movement of overlying strata under different advancing speeds, and the mechanism of rockburst occurrence in deep roadways with double coal pillars under coupled dynamic and static loading has been further clarified (Pang et al., 2021; Fu et al., 2022). Yang Junzhe (Pendleton et al., 2022) examined the influence of coal pillar width on surrounding rock stress and plastic zone distribution, providing a basis for rational pillar design. Under ultra-long working face conditions, studies have shown that with increasing face length, the block size of broken key strata decreases and the manifestation of mine pressure tends to become more uniform (Wang et al., 2018). Working face length is also regarded as one of the main factors controlling the development height of the overburden fracture zone (Mingzhong et al., 2024), and the mine pressure distribution of ultra-long working faces exhibits a distinctive three-peak characteristic, in which the face inclination pressure shows a pronounced undulating pattern during periodic weighting (Chen et al., 2022).

Building on these efforts, researchers have gradually shifted their focus from single working faces to coordinated multi–working-face mining. Zhang et al. (2023b) developed an overburden structural evolution model for multi–working-face extraction and systematically revealed the dynamic transformation of the overburden structure from an I-shaped configuration to an O-shaped configuration, together with the corresponding distribution of abutment pressure. Yizhe et al. (2023), based on engineering practice in the Yima mining area, proposed a regional coordinated mining scheme that effectively reduced the risk of rockburst. Zhi et al. (2016) found that the vertical stress peak at 10 m ahead of the working face can reach up to 2.3 times the original in situ stress and increases with advancing step length. Wang et al. (2022) emphasized that remnant coal pillars in the goaf tend to trigger instability of the coal pillar–key stratum structural system.

Despite these important advances, most existing studies still concentrate on the mining response of a single working face or a local area, and systematic investigations on the spatiotemporal evolution of mining-induced stress, overburden structural movement and regional stress transfer mechanisms under coordinated multi–working-face conditions remain relatively limited (Zhipeng et al., 2023; Guo et al., 2018; Hao et al., 2022). Regional coordinated mining is an important technical approach to regulating the distribution of mining-induced stress and improving the stability of the surrounding rock. By optimizing working face layout, extraction sequence, advancing rate and coal pillar dimensions, it is possible to effectively reduce stress concentration and avoid unfavorable combinations of overburden structures (Guo, 2023). However, in current engineering practice, the design of multi–working-face layout and coordinated extraction parameters still relies heavily on empirical experience, and a systematic design theory rooted in the coupled mechanisms of stress interaction and overburden dynamic response among multiple working faces has yet to be established (Wang et al., 2023c). Therefore, in-depth research on the evolution of mining-induced stress and its impact on rock-mass stability under coordinated multi–working-face mining conditions is of great significance for improving the theoretical framework and technical system of surrounding rock control in deep, high-intensity mining.

Taking the coordinated multi–working-face mining and underground reservoir construction at Liuta Coal Mine as the engineering background, this study employs numerical simulation to systematically investigate the distribution and transfer of mining-induced stress, overburden failure characteristics and fracture-zone evolution during the coordinated extraction of working faces 22,214 and 22,215. The work focuses on the dynamic evolution of abutment pressure along strike and dip, the pattern of stress concentration and pronounced asymmetry in the coal pillar, and the mechanisms of plastic-zone expansion and coalescence, thereby quantitatively revealing stress superposition effects and the cumulative damage of the surrounding rock under multi–working-face retreat. The results will be applied to stress–displacement monitoring and stability assessment of the underground reservoir dam at Liuta Mine under mining influence, and provide a theoretical basis and engineering reference for controlling mining-induced hazards and maintaining surrounding rock stability under similar geological and mining conditions.

2 Engineering background and numerical simulation

In the numerical simulations, the geological conditions of working faces 22,214 and 22,215 in Liuta Coal Mine were used as the initial model inputs. Liuta Mine mainly exploits the Middle Jurassic Yan’an Formation, with burial depths ranging from 237.25 to 329.01 m and an average depth of 282.66 m. According to lithologic assemblage, sedimentary cycles and coal-bearing characteristics, the formation can be divided into three subsections. The main coal seam is located in the upper part of the Yan’an Formation and extends from the coal seam roof up to the top boundary of the Yan’an strata. The overlying rocks are composed mainly of greyish-white conglomeratic coarse sandstone and medium sandstone interbedded with dark grey siltstone, sandy mudstone and coal, with a total thickness of 49.37–117.61 m and an average thickness of 70.14 m. The main coal seam is 0.67–6.37 m thick, with an average thickness of 2.79 m, and can be classified as a medium-thick seam. The coal seam structure is relatively simple, with local partings dominated by mudstone and sandy mudstone. The immediate roof is mainly composed of siltstone and sandy mudstone, while the floor is dominated by sandy mudstone and siltstone. In the simulations, the physical and mechanical properties of the in situ rocks were taken as the initial model parameters. Rock-mechanical parameters were mainly derived from in situ test data obtained in the study area and were checked and supplemented using relevant published research. The physical and mechanical parameters of the coal and rock strata used in the model are summarized in Table 1.

TABLE 1

| Lithology | Bulk modulus (GPa) | Cohension (MPa) | Friction (°) | Tension (MPa) | Density (kg/m3) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Surface layer | 0.24 | 0.03 | 20.1 | 0.02 | 1800 |

| Medium sandstone | 8.57 | 3.08 | 31.3 | 2.25 | 2,633 |

| Fine sandstone | 12.45 | 2.52 | 31.6 | 2.68 | 2,288 |

| Siltstone | 11.56 | 2.62 | 35.3 | 3.18 | 2,188 |

| Argillaceous siltstone | 5.83 | 1.55 | 28.9 | 2.01 | 2,750 |

| Coal | 1.89 | 1.71 | 25.8 | 0.83 | 1900 |

Physical and mechanical parameters of coal and rock.

In this study, numerical modeling and analysis were carried out using the FLAC3D code. FLAC3D is based on an explicit finite-difference scheme and is well suited to simulating large deformation and progressive failure in geomaterials. It can continuously and dynamically track the evolution of stress, strain and plastic zones throughout the computational domain under loading, and it is capable of reproducing the full mechanical process from initial elastic response through yielding and failure to overall instability. This capability is essential for investigating overburden movement, fracture development and mine pressure behavior induced by coal seam extraction. An elastic–plastic constitutive model combined with the Mohr–Coulomb yield criterion was adopted, owing to its wide acceptance in engineering practice, the relative ease of obtaining the required parameters and its ability to capture the macroscopic characteristics of shear failure in rock masses, thereby meeting the needs of analyzing the evolution of the mining-induced stress field and the development of plastic zones (Zhao, 2000).

The full-scale numerical model established in this study is shown in Figure 1, with overall dimensions of 2048 m in length, 4,300 m in width and 500 m in height. Excavation of the working faces starts 200 m away from the model boundary. An elastic–plastic constitutive model is adopted, with displacements in the X, Y and Z directions fixed at the model base, and an equivalent vertical load applied on the top surface to represent the overburden pressure. The maximum horizontal principal stress ranges from 19.96 to 27.46 MPa, with an orientation between N26.48°W and N72.42°W, and the lateral pressure coefficient ranges from 1.31 to 1.57 with an average of 1.44. The model is discretized using four-node tetrahedral elements, with local mesh refinement in regions where significant deformation is expected, resulting in a total of 182,860 nodes and 495,484 elements. Key computational parameters such as time step and damping coefficient are taken from verified default values in FLAC3D or adjusted based on numerical stability, so as to ensure convergence of the calculation and the reliability of the results.

FIGURE 1

Numerical model: (a) Whole model; (b) Working face.

After applying gravity and boundary conditions and performing the initial equilibrium calculation, the initial stress distribution of the model was obtained, as shown in Figure 2. The model includes two working faces, 22,214 and 22,215, and the simulated mining sequence is consistent with actual production: the initial working face 22,214 is mined first, followed by coordinated extraction of the subsequent working face 22,215. A 60 m coal pillar is left between the two faces, and sufficiently wide protective coal pillars are reserved along the remaining boundaries to reduce boundary effects on the numerical results.

FIGURE 2

Initial stress distribution.

3 Analysis of numerical simulation results for the primary mining face

3.1 Stress evolution in the first-mined working face 22,214

The initial working face 22,214 has a total length of 320 m, and the evolution of its stress distribution along strike with advancing distance is shown in Figure 3. After excavation, a stress-relief zone develops directly above the goaf, while stress concentration appears in front of the coal wall. As the face advances, the influence range, peak magnitude and position of the abutment stress change dynamically.

FIGURE 3

Stress along the strike of 22,214 working face at different advancements: (a) 800 m, (b) 1,600 m, (c) 2,400 m, (d) 3,200 m of advance, and (e) after full extraction.

When the face has advanced to 800 m, as shown in Figure 3a, the influence range of the abutment stress is about 32 m, the stress concentration factor is 1.6, and the peak is located approximately 14 m ahead of the coal wall. At an advance distance of 1,600 m, illustrated in Figure 3b, the influence range expands to 38 m, the stress concentration factor increases to 1.75, and the peak moves forward to about 10 m ahead of the coal wall. At 2,400 m, shown in Figure 3c, the influence range reaches 42 m and the stress concentration factor attains its maximum value of 1.8, while the peak position shifts slightly backward to around 12 m. At 3,200 m, shown in Figure 3d, the influence range contracts to 37 m, the stress concentration factor decreases back to 1.6, and the peak moves to about 17 m ahead of the coal wall. After completion of extraction, as shown in Figure 3e, the overall stress distribution becomes more uniform.

The evolution of the strike-direction stress distribution along working face 22,214 is consistent with the dynamic overburden evolution described by key stratum theory. At the early stage of advance, for example, at an advance distance of 800 m, the overlying key stratum is in a cantilever state, and its own stiffness together with the underlying support system jointly carry the overburden load. The resulting stress concentration factor is relatively low and the peak stress is located farther from the coal wall. As the face advances to between about 1,600 m and 2,400 m, the exposed area of the roof increases, the deflection of the key stratum grows and load transfer to the coal ahead of the face is enhanced. Consequently, the stress concentration factor rises and the peak position moves closer to the coal wall. When the advance distance reaches around 2,400 m, the stress concentration factor attains its maximum value of 1.8, corresponding to the initial failure of the sub-key stratum, and the loss of stability causes a sharp transfer of load to the coal ahead of the face. After failure, the key stratum transforms into a masonry-beam type structure and enters a relatively stable stage, the stress is redistributed and the peak position shifts slightly backward.

3.2 Stress distribution along the dip direction of working face 22,214

The evolution of the stress distribution along the dip direction of working face 22,214 with advancing distance is shown in Figure 4. After excavation, a distinct stress-relief zone develops directly above the goaf, while symmetric stress concentration zones form at the coal walls on both sides, exhibiting a bimodal distribution. At an advance distance of 800 m, as shown in Figure 4a, initial stress concentration appears on both sides of the coal wall, the stress-relief zone remains relatively intact, and the dip-direction stress distribution is still in a developmental stage. When the face advances to 1,600 m, as shown in Figure 4b, the degree of stress concentration increases markedly, the influence range extends deeper into the coal, and the width of the stress-relief zone becomes larger. At 2,400 m of advance, as illustrated in Figure 4c, stress concentration becomes more pronounced and the peak stresses on both sides further increase, indicating that intensified roof activity has a stronger impact on coal wall stability. When the advance reaches 3,200 m, as shown in Figure 4d, the stress concentration zones tend to stabilize, and changes in peak stress and influence range slow down, suggesting that the surrounding rock is gradually approaching a new mechanical equilibrium. By the end of extraction, as shown in Figure 4e, the dip-direction stress distribution is basically stable; although the stress concentration on both sides remains at a relatively high level, the overall distribution pattern does not change significantly.

FIGURE 4

Stress along the inclination of 22,214 working face at different advancements: (a) 800 m, (b) 1,600 m, (c) 2,400 m, (d) 3,200 m of advance, and (e) after full extraction.

3.3 Evolution of fractured zones in working face 22,214

The development of the plastic zone not only reflects the yielding and failure process of the rock mass under mining disturbance, but also reveals the stability of the overlying strata structure and the characteristics of energy release. The evolution of the plastic zone above working face 22,214, as shown in Figure 5, exhibits a clear stage-wise behavior (Jiang et al., 2017).

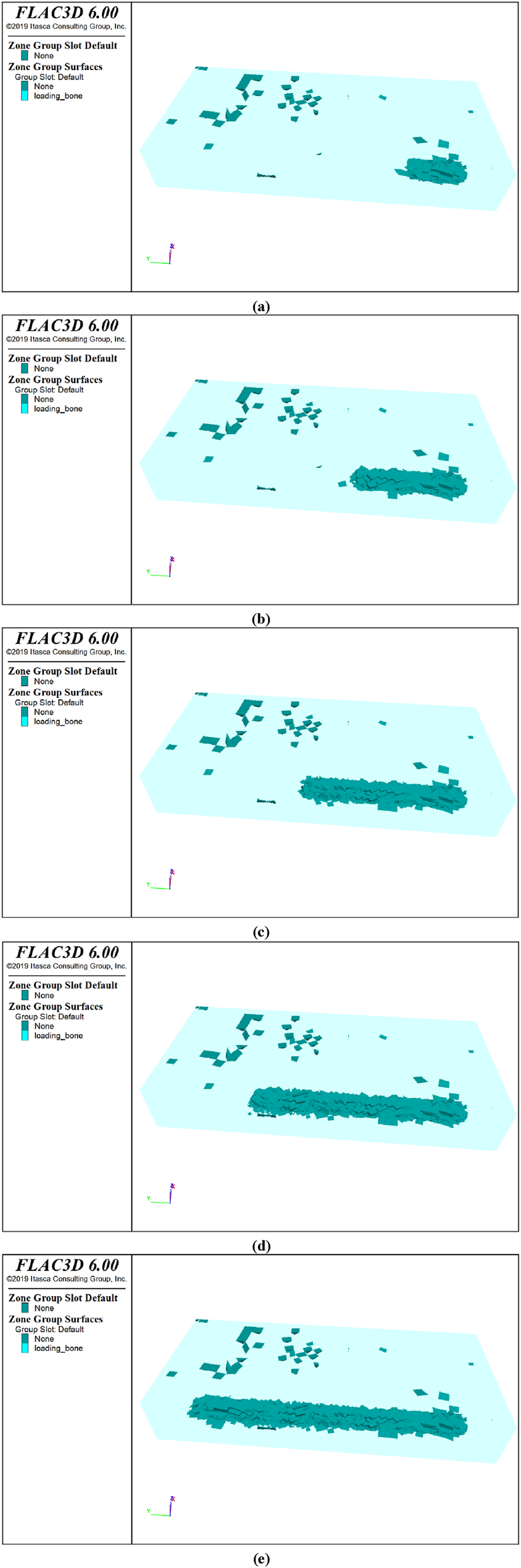

FIGURE 5

Plastic zone of 22,214 working face at different advancements: (a) 800 m, (b) 1,600 m, (c) 2,400 m, (d) 3,200 m of advance, and (e) after full extraction.

At an advance distance of 800 m, as shown in Figure 5a, the plastic zone is mainly concentrated in the immediate roof above the goaf and is discontinuous, indicating that the roof has not yet undergone through-going failure. When the advance reaches 1,600 m, as shown in Figure 5b, large-scale shear failure occurs in the immediate roof, forming an incipient caving zone, while tensile fractures appear in the strata beneath the sub-key stratum and a fracture zone begins to develop. At 2,400 m of advance, as shown in Figure 5c, the plastic zone expands rapidly, the height of the fracture zone extends up to the key stratum, and the rock mass experiences structural instability. At 3,200 m, as shown in Figure 5d, the development of the plastic zone enters a stable stage, and the height of the fracture zone reaches its maximum and tends to stabilize. By the end of extraction, as shown in Figure 5e, a continuous plastic zone is formed in the central part of the goaf, delineating a complete mining-affected zone.

As the initial working face, the plastic zone above the goaf of 22,214 displays an overall symmetric pattern, which reflects the symmetric transmission of the mining-induced stress field and provides a basis for the layout of adjacent working faces.

4 Numerical analysis of the subsequent working face

4.1 Strike-direction stress distribution in working face 22,215

The subsequent working face 22,215 has a length of 320 m, and the evolution of its strike-direction stress distribution with advancing distance is shown in Figure 6. Compared with the initial working face 22,214, working face 22,215 is a successive face and exhibits higher stress concentration and different evolution characteristics.

FIGURE 6

Stress along the strike of 22,215 working face at different advancements: (a) 800 m, (b) 1,600 m, (c) 2,400 m, (d) 3,200 m of advance, and (e) after full extraction.

When the advance reaches 800 m, as shown in Figure 6a, the influence range of the abutment stress is about 35 m, the stress concentration factor reaches 1.7, and the peak stress is located roughly 12 m ahead of the coal wall. Relative to working face 22,214 at the same advancing distance, the influence range increases by 3 m and the concentration factor rises by 0.1, indicating that the supporting effect of the coal pillar has begun to affect the mechanical distribution along the face.

At an advance distance of 1,600 m, as shown in Figure 6b, stress concentration is further intensified, the influence range expands to about 42 m, the stress concentration factor increases to 1.9, and the peak position moves forward to about 8 m ahead of the coal wall. Compared with working face 22,214 at this stage, the concentration factor is higher by 0.15, reflecting the superposition effect of the stress field induced by the adjacent goaf.

When the face advances to 2,400 m, as illustrated in Figure 6c, the influence range reaches a maximum of about 46 m, the stress concentration factor rises to 2.1, and the peak position shifts backward to about 10 m, which reflects the cumulative effect of stress concentration in the coal pillar. At an advance distance of 3,200 m, as shown in Figure 6d, the influence range begins to contract to about 43 m, the concentration factor decreases to 1.9, and the peak moves to approximately 15 m ahead of the coal wall. After the completion of extraction, as shown in Figure 6e, the overall stress distribution tends to stabilize, but the coal pillar region still maintains a relatively high residual stress, with the stress concentration factor remaining at about 1.8.

4.2 Dip-direction stress distribution in working face 22,215

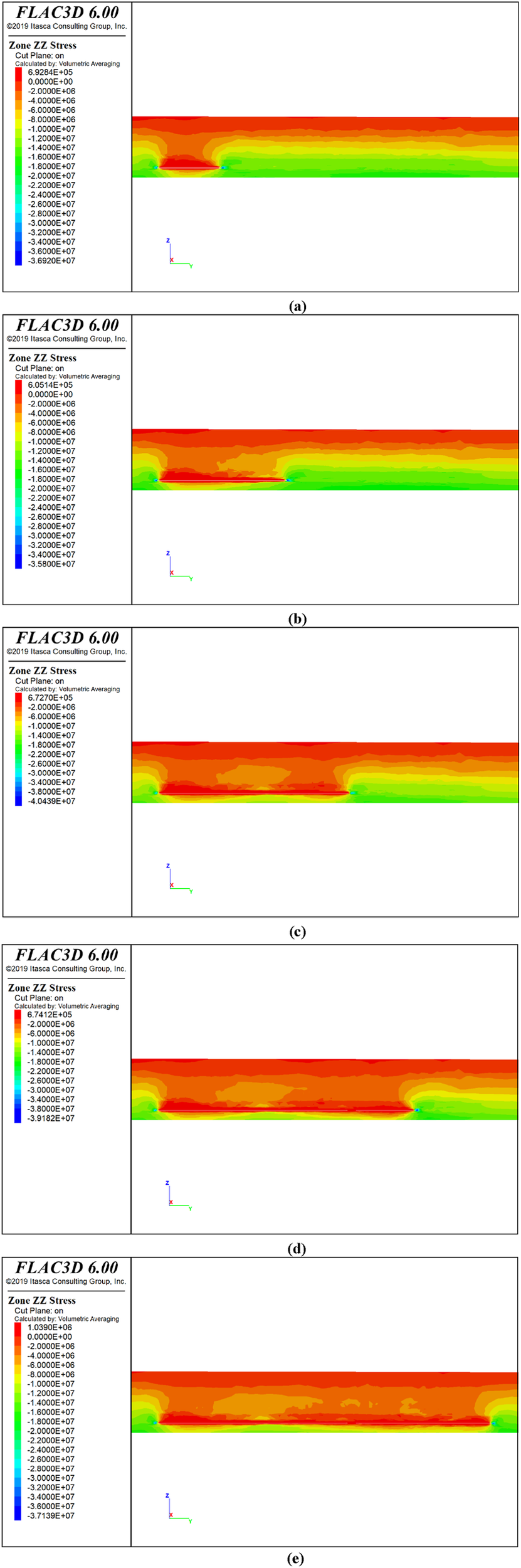

The evolution of the dip-direction stress distribution of working face 22,215 with advancing distance is shown in Figure 7. Compared with working face 22,214, working face 22,215 exhibits a clearly asymmetric dip-direction stress pattern, and the coal pillar region remains in a state of high stress concentration throughout (Guichen et al., 2022).

FIGURE 7

Stress along the inclination of 22,215 working face at different advancements: (a) 800 m, (b) 1,600 m, (c) 2,400 m, (d) 3,200 m of advance, and (e) after full extraction.

When the face advances to 800 m, the stress-relief zone begins to form. Influenced by the 22,214 goaf, stress concentration on the left coal pillar side is more pronounced, with a concentration factor of 1.8, while that on the right coal wall side is 1.6, indicating the onset of asymmetry. At 1,600 m, the stress asymmetry becomes more evident, the concentration factors continue to increase, the influence range expands, and elevated stresses appear in the floor, showing that mining-induced effects are propagating to greater depths. At 2,400 m, the asymmetry of the stress distribution reaches its maximum: the stress concentration factor on the left coal pillar side rises to 2.3, while that on the right side is 1.8, giving a difference of 0.5. When the advance reaches 3,200 m, the degree of stress concentration begins to ease but the asymmetric pattern remains obvious, with concentration factors of 2.1 on the left side and 1.7 on the right. By the end of extraction, the dip-direction stress distribution tends to stabilize, while the left coal pillar region still has a concentration factor of about 2.0 and the right side about 1.6, indicating that high stress in the coal pillar is long-lasting.

The above stress asymmetry mainly arises from the instability of the key strata above the 22,214 goaf. After extraction of working face 22,214, the key strata over the goaf on that side fracture and cave, losing their capacity to transmit load, so the overlying load is redistributed laterally toward the retained coal pillar and the side of working face 22,215. On the opposite side of 22,215, the key strata remain relatively intact and retain a stronger load-bearing capacity, resulting in a clear contrast in dip-direction stress distribution between the two sides. The analysis indicates that working face 22,215 is mined under a single-side goaf condition and its stress field is significantly influenced by the adjacent 22,214 goaf. Because the coal pillar is subjected to superposed mining-induced loads from both sides, the stress concentration in this region is particularly high. In the later stage of mining, floor deformation increases, and the high stress concentration promotes the development of plastic zones in the floor strata, which in turn may trigger floor heave and related instability problems.

4.3 Evolution of fractured zones in working face 22,215

The evolution of the plastic zone above working face 22,215, as shown in Figure 8, is characterized by early onset, strong intensity and pronounced asymmetry. Compared with working face 22,214, the plastic zone of 22,215 is significantly wider at the same advancing distance; at an advance of 800 m, the width increases by about 18 percent, as shown in Figure 8a. As the face continues to advance, the plastic zone on the side close to the 22,214 goaf, that is, the left side, develops much faster than on the opposite side, as shown in Figures 8b,d. At an advance distance of 2,400 m, as shown in Figure 8c, the width of the plastic zone on the left side is about 40 percent greater than on the right side and shows a clear tendency to connect with the plastic zone above the 22,214 goaf. By the end of extraction, as illustrated in Figure 8e, the plastic zones of the two faces are fully connected, forming a continuous plastic failure belt. These observations indicate that under the influence of the asymmetric stress field, the goaf of working face 22,215 enters plastic yielding and failure earlier and more readily, and the damage is more severe on the side adjacent to the 22,214 goaf.

FIGURE 8

Plastic zone of 22,215 working face at different advancements: (a) 800 m, (b) 1,600 m, (c) 2,400 m, (d) 3,200 m of advance, and (e) after full extraction.

On the basis of key stratum theory, when the secondary working face is mined, the key strata on the side adjacent to the goaf have already been destabilized by the extraction of the primary face, which weakens the lateral confinement of the overlying strata and promotes the initiation and growth of fracture zones. At the same time, the uneven transfer of load causes the coal pillar region to become a high-stress channel and a concentration zone for plastic deformation. The asymmetric coalescence of the plastic zone further undermines the integrity of the coal pillar and reduces its long-term load-bearing stability.

In summary, the numerical simulation results show that the overburden evolution above the primary and secondary working faces differs significantly due to mining-induced effects. The overburden above the primary working face is controlled by the key strata and undergoes essentially symmetric fracturing. In contrast, the secondary working face is subjected to asymmetric boundary conditions imposed by the goaf of the primary face, so that the overlying load is transferred laterally toward the coal pillar, causing distortion of the stress field, asymmetric development of the plastic zone, and eventual coalescence between the plastic zones above the two adjacent goafs.

5 Discussion of overlying strata stress evolution characteristics in coordinated multi-working face mining

This study uses numerical simulation to elucidate the evolution of overburden stress and the development of plastic zones under coordinated multi-working-face mining. The results show that the primary working face exhibits a largely symmetric stress distribution and plastic-zone evolution during its advance, whereas the secondary working face is strongly disturbed by the adjacent goaf, leading to pronounced asymmetry in stress distributions along both strike and dip, high stress concentration in the coal pillar region, and coalescence of its plastic zone with that above the primary goaf.

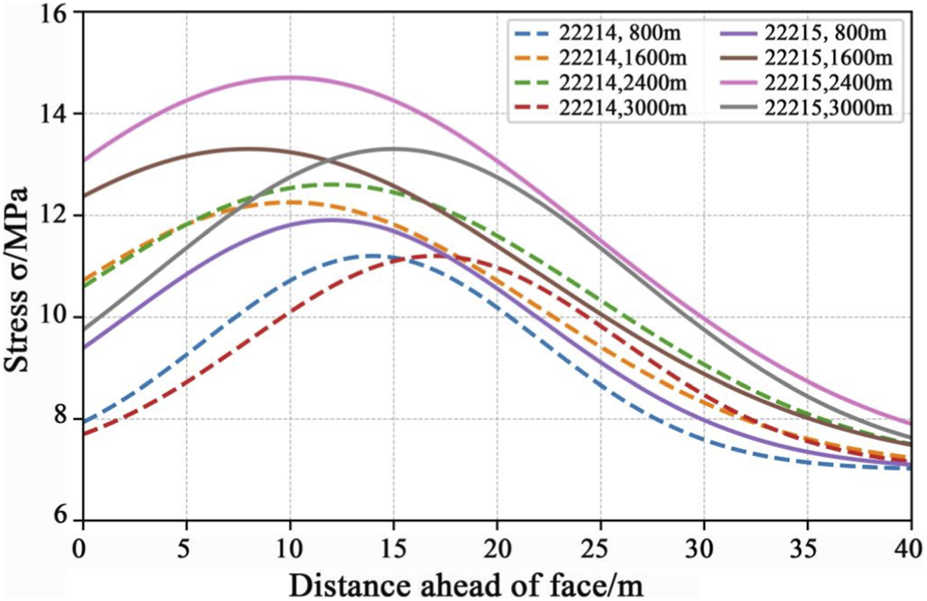

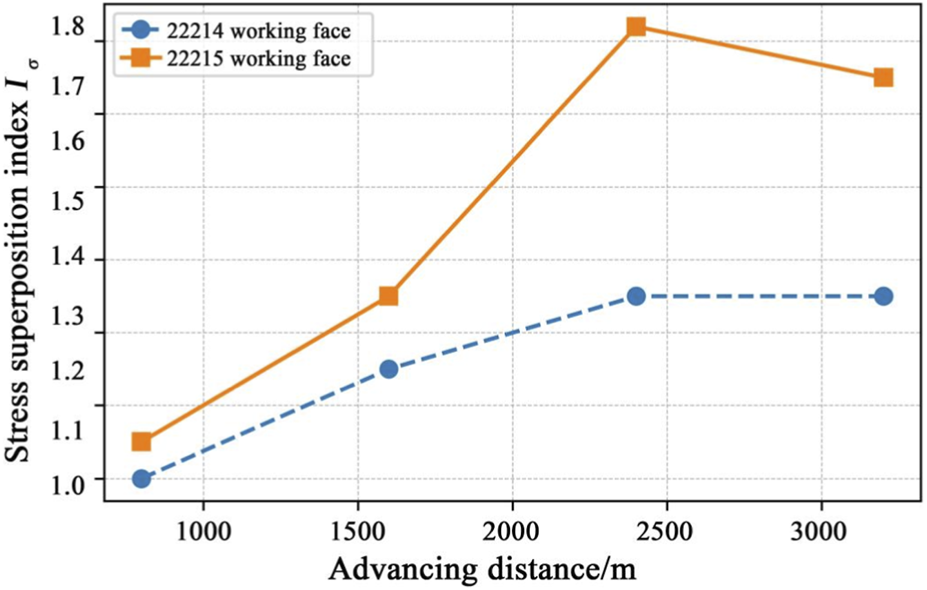

To quantify the differences in stress distribution between the primary and secondary working faces, stress concentration factors at different advancing distances were compared, as summarized in Table 2. On this basis, the vertical stress within the coal wall in the zone 0–40 m ahead of the face was extracted from the numerical results for both faces, and the corresponding stress–distance curves were plotted, as shown in Figure 9. Taking the in situ stress σ0 as the reference, a normalized stress increment curve was , and the area under this curve was calculated as ,where Iσ is defined as the stress superposition index. To emphasize the relative differences between advancing stages, the value of Iσ for the primary working face 22,214 at an advance of 800 m was set to 1.0, and the indices for the other stages and for the secondary working face were nondimensionalized by proportional scaling of the curve area, as illustrated in Figure 10, which shows the variation of the coal-wall stress superposition index with advancing distance.

TABLE 2

| Stress concentration factor | Advancing distance (m) | First-mined working face | Subsequent working face | Difference rate (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Strike peak value | 800 | 1.6 | 1.7 | +6.3 |

| 1,600 | 1.75 | 1.9 | +8.6 | |

| 2,400 | 1.8 | 2.1 | +16.7 | |

| 3,200 | 1.6 | 1.9 | +18.8 | |

| Dip-left peak value | 2,400 | 1.8 | 2.3 | +27.8 |

| Dip-right peak value | 2,400 | 1.8 | 1.8 | 0 |

Comparative analysis of stress concentration factors in working faces.

FIGURE 9

Stress–distance curves of coal wall at different advancing distances.

FIGURE 10

Iσ variation with advancing distance for the 22,214 and 22,215 working faces.

According to Table 2 and Figures 9, 10, as the advance of the primary working face 22,214 increases from 800 m to 2,400 m, both the peak value of the advance abutment pressure along strike and the stress increment within 0–40 m ahead of the face increase gradually, and the corresponding stress superposition index Iσ rises from 1.00 to about 1.25. When the advance reaches 3,200 m, the peak stress concentration factor drops to 1.6 while Iσ remains almost unchanged, indicating that the mining-induced stress has entered a relatively stable stage and that the overburden stress evolution is generally consistent with the numerical results for deep high-stress faces reported by Lei Yanzhi (Wang and Yang, 2023; Qi and Jianhao, 2018). In contrast, the stress–distance curves of the secondary working face 22,215 are overall higher than those of the primary face at all advancing stages; at 2,400 m the Iσ within 0–40 m ahead of the face is about 1.3 times that of the primary face and the corresponding peak strike-direction stress concentration factor reaches 2.1. In the dip direction, the stress concentration factor in the coal-pillar area adjacent to the goaf further increases to 2.3, giving a left–right difference of 27.8%. These results show that an advance of about 2,400 m corresponds to the stage of strongest multi-face stress superposition and load redistribution, which is also the key interval for controlling surrounding-rock stability and optimizing support parameters.

To further clarify the transfer path of stress from the goaf of the primary working face to the coal pillar and the coal mass ahead of the secondary face, a section A–A′ was arranged along the line “22,214 goaf–coal pillar–area ahead of the 22,215 face” in the numerical model, and the field of maximum principal stress vectors was extracted for analysis, as shown in Figure 11. After the extraction of 22,214, the overlying key strata above the goaf undergo composite failure and form a cantilever–voussoir beam system whose arch foot is located above the coal pillar; within this structure, stress trajectories rotate from being nearly vertical in the central part of the goaf to obliquely downward toward the pillar, indicating that the residual load is concentrated onto the pillar along the broken key strata. When the advance of 22,215 reaches about 2,400 m, both the density and magnitude of the vectors increase markedly in the upper part of the pillar and within 0–30 m ahead of the face, and high-stress vectors converge in a fan-shaped pattern from left to right: they first point from the residual bearing zone of the 22,214 goaf to the hinged position above the pillar, then bend along the combined pillar–floor structure and finally point toward the coal mass ahead of 22,215, forming a continuous high-stress channel from the 22,214 goaf through the coal pillar to the front of the 22,215 face. Combined with the strike-direction stress curves and stress concentration factors, these results indicate that the overlying key-strata assemblage evolves from a cantilevered configuration on the primary-face side to a hinged configuration on the secondary-face side during multi-face sequential mining, leading to lateral load transfer and secondary superposition on the coal pillar and the coal ahead of the secondary face, which is consistent with the load-transfer behaviour of low-position key strata under multi-face mining revealed by Zhang et al. (2024b).

FIGURE 11

Maximum principal stress vectors along the A-A′ section.

To characterize the evolution of the plastic zone, the areas of plastic failure in the central part of the goaf Ac, in the plastic zone above the left coal pillar Al, and in the plastic zone above the right coal pillar Ar were calculated at different advancing distances based on an element yield criterion. Taking the total plastic area at the 800 m stage of the primary working face as the reference value Ao, a plastic zone evolution index IP was defined as IP=(Ac + Al + Ar)/A, and its variation with advancing distance is shown in Figure 12. For the primary working face, IP increases slowly with advance and becomes essentially stable after 2,400 m, whereas for the secondary working face, IP grows much more rapidly and reaches about 1.4 times that of the primary face at 2,400 m. At the same time, the area ratio of the plastic zones on the left and right sides of the coal pillar Al/Ar increases from nearly 1.0 in the early stage to about 1.6, which is consistent with the conclusion in Section 4.3 that the plastic zone on the side adjacent to the primary goaf connects with the goaf, while the other side remains relatively weak. On this basis, the advancing process of multiple working faces can be quantitatively divided into three stages: low superposition, medium superposition, and strong superposition. When both the stress superposition index Iσ and the plastic zone evolution index IP exceed approximately 1.3 times the corresponding values of the primary face, the system enters the strong superposition stage at an advance of about 2,400 m. In this stage, the coal pillar and floor bear highly concentrated stresses, are prone to severe deformation and rockburst, and therefore form a key zone that must be strictly controlled under coordinated multi-face mining. The observed evolution of the plastic zone is consistent with the dynamic transformation of the overburden structure from an I-shaped to an O-shaped configuration reported in previous studies (Pang et al., 2021).

FIGURE 12

I p variation with advancing distance for the 22,214 and 22,215 working faces.

From the perspective of crack evolution, the staged change of the plastic zone can be given a physical interpretation. A large number of rock-mechanics and acoustic-emission experiments have shown that brittle rocks containing multiple flaws generally undergo a staged evolution under uniaxial or true-triaxial loading, including crack initiation, formation of crack clusters, development of crack bands and final coalescence into through-going fractures (Zhang and Zhou, 2020; Zhou and Zhang, 2021; Niu et al., 2020). In this study, the numerical results exhibit a similar pattern: the plastic zone evolves from localized plastic damage to continuous plastic bands and ultimately to a coalescent plastic failure corridor. This spatiotemporal evolution is broadly consistent with the experimentally observed process of crack initiation, propagation and coalescence, indicating that the plastic-zone penetration revealed in this paper is physically reasonable and in line with existing research. It should be noted, however, that due to the assumptions of a continuum constitutive model and the limitation of mesh resolution, the present simulations cannot explicitly capture individual crack trajectories or the detailed timing of acoustic-emission events; the conclusions mainly reflect the characteristics of plastic failure at the engineering scale. Future work will therefore combine underground microseismic and acoustic-emission monitoring with higher-resolution numerical modelling to carry out more refined comparative studies.

Based on the above analysis, the pronounced asymmetric stress distribution and the early, intense and through-going development of the plastic zone on the coal-pillar side of the secondary working face can be controlled in practice by combining differentiated support with directional destressing. For the roadway on the coal-pillar side of the 22,215 working face, an asymmetric reinforced support system can be adopted by appropriately increasing the length and density of rock bolts and cables along the side adjacent to the 22,214 goaf, in combination with steel arches or cable–steel strip support and simultaneous floor reinforcement, so as to enhance the overall stiffness and shear resistance of the surrounding rock in the coal-pillar area. At the same time, directional roof pre-splitting can be implemented within about 10–20 m above the coal pillar along the bottom boundary of the key stratum, and destress blasting holes or directional destress boreholes can be arranged 20–30 m ahead of the working face near the coal-pillar side, in order to reduce local peak stresses and interrupt the continuity of the plastic failure zone.

Building on this work, future research can integrate multi-source data from microseismic monitoring, stress-field evolution and plastic-zone development to construct a multi-parameter coupled early-warning model for coordinated multi-working-face mining, thereby quantitatively characterizing the coupling among key-stratum failure, stress transfer and rockburst occurrence and providing more robust theoretical support and technical tools for the prediction, early warning and mitigation of rockbursts under deep multi-working-face mining conditions.

6 Conclusion

This study employs numerical simulation to investigate the evolution of mining-induced stress and overburden failure under coordinated multi-working-face mining, and compares the strike- and dip-direction stress distributions, plastic zone development, and their interaction mechanisms between the first-mined working face 22,214 and the subsequent working face 22,215. The main conclusions are as follows.

1. The strike-direction stress distribution of the working faces exhibits pronounced dynamic evolution. For the first-mined working face 22,214, both the peak value and the influence range of the abutment pressure ahead of the face increase with advancing distance and then tend to stabilize, with a maximum stress concentration factor of 1.8. For the subsequent working face 22,215, which is affected by the goaf of 22,214, the overall stress level is higher and the stress superposition index Iσ is about 1.3 times that of 22,214, indicating that coordinated multi-working-face mining significantly amplifies the superposition of mining-induced stress.

2. The dip-direction stress distributions of the two working faces differ markedly, and the stress field of the subsequent face shows strong asymmetry. For 22,214, the dip-direction stress is approximately symmetric, whereas for 22,215 the coal pillar side adjacent to the goaf exhibits a maximum stress concentration factor of 2.3, compared with about 1.8 on the opposite side, giving a left–right difference of about 27.8%. This asymmetric stress distribution leads to significantly enhanced stress release and deformation in the floor on the coal pillar side and is a primary factor controlling the stability of the surrounding rock of the subsequent working face.

3. The mining sequence and stress superposition jointly control the morphology and extent of the plastic zone. For 22,214, the plastic zone expands in an essentially symmetric manner and the evolution index Ip increases slowly before stabilizing. For 22,215, Ip increases more markedly and shifts toward the goaf of the first-mined face, eventually coalescing with the plastic zone of the 22,214 goaf, which weakens the coal pillar strength and increases the likelihood of rockburst.

4. Under similar geological conditions and burial depth, the advancing stage during which the main key stratum transforms from a cantilevered configuration to a broken voussoir-beam structure can be regarded as a key control segment characterized by strong superposition of mining-induced stress and plastic deformation. This segment should be treated as a priority zone for surrounding rock stability control and support parameter optimization, where a combination of differential reinforcement support and directional destressing measures can be adopted for hazard prevention and control.

Statements

Data availability statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

Author contributions

XB: Investigation, Writing – original draft. QY: Conceptualization, Supervision, Writing – review and editing. QJ: Software, Data curation, Writing – original draft. JS: Writing – original draft, Data curation. ZC: Investigation, Formal Analysis, Writing – original draft. XL: Writing – original draft, Data curation.

Funding

The author(s) declared that financial support was received for this work and/or its publication. This work was funded by the Key Science and Technology Project of China Energy, grant number GJNY-21-26 & HT2025-2; and was funded in part by the National Natural Science Foundation of China, grant number 51804052.

Conflict of interest

Authors QJ and JS were employed by Chongqing Bojian Technology Co., Ltd.

The remaining author(s) declared that this work was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The author(s) declared that generative AI was not used in the creation of this manuscript.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

1

Chen J. Ren J. Yajun X. I. N. (2022). Study on strata behavior laws in ultra-long fully mechanized working face. Coal Technol.41 (10), 10–14. 10.13301/j.cnki.ct.2022.10.003

2

Feng C. Cheng Z. Xing-Ping L. Tao X. Yun-Hu B. Yi Z. et al (2025). Strata behavior laws and regional grade intelligent early warning for high-intensity mining in lengthened working face of medium-thick coal seam, Yuheng mining area. J. China Coal Soc.50 (06), 2866–2880. 10.13225/j.cnki.jccs.2025.0292

3

Fu Y. Zhang J. Chuantian Li Rui Wu Xiaoxia Li (2022). Advancing speed effect of front abutment pressure in high-intensity mining face. Coal Technol.41 (09), 14–17. 10.13301/j.cnki.ct.2022.09.003

4

Gao X. Hui L. I. U. (2017). Dynamic evolution prediction of surface subsidence ponding caused by multi-layers coal mining in the high groundwater level area. Metal. Mine (10), 39–42. 10.19614/j.cnki.jsks.2017.10.009

5

Guichen L. I. Yang S. Sun Y. Jinghua L. (2022). Research progress of roadway surrounding strata rock control technologies under complex conditions. Coal Sci. Technol.50 (6), 29–45. 10.13199/j.cnki.cst.2022-0304

6

Guo R. (2023). Study on evolution law of overburden rock fissure in repeated mining goaf of coal seam group. Coal Technol.42 (9), 81–85. 10.13301/j.cnki.ct.2023.09.016

7

Guo W. Bai E. Yang D. (2018). Study on the technical characteristics and index of thick coal seam high-intensity mining in coalmine. J. China Coal Soc.43 (8), 2117–2125. 10.13225/j.cnki.jccs.2017.1573

8

Hao L. I. Tang S. Liqiang M. A. Haiboe B. A. I. Kang Z. et al (2022). Continuous-discrete coupling simulation study on progressive failure of mining overlying strata. Chin. J. Rock Mech. Eng.41 (11), 2299–2310. 10.13722/j.cnki.jrme.2022.0098

9

Heping X. I. E. Feng G. A. O. Yang J. U. (2015). Research and exploration of deep rock mechanics. Chin. J. Rock Mech. Eng.34 (11), 2161–2178. 10.13722/j.cnki.jrme.2015.1369

10

Hongpu KANG Gao F. (2024). Evolution of mining-induced stress and surrounding rock control in coal mines. Chin. J. Rock Mech. Eng.43 (01), 1–40. 10.13722/j.cnki.jrme.2023.1055

11

Jiang L. Wu Q. Xiaoyu L. I. Nan D. (2017). Numerical simulation on coupling method between mining-induced stress and goaf compression. J. China Coal Soc.42 (8), 1951–1959. 10.13225/j.cnki.jccs.2016.1717

12

Minghui Z. A. N. Peng H. Song G. (2023). Study on mine pres sure behavior law of downward mining face in close distance coal seam group under repeated mining. Coal Chem. Indus Try46 (4), 10–13. 10.19286/j.cnki.cci.2023.04.003

13

Mingzhong L. I. Wenge Z. Ruyu Y. A. N. Wang J. Yajun L. E. I. Zheng Y. et al (2024). Development status and prospect on key technical equipment of high efficiency fully mechanized mining in super high and super long working face. Coal Sci. Technol.52 (09), 199–209.

14

Niu Y. Zhou X. P. Berto F. (2020). Evaluation of fracture mode classification in flawed red sandstone under uniaxial compression. Theor. & Appl. Fract. Mech.107, 102528. 10.1016/j.tafmec.2020.102528

15

Pang Y. Gong S. Liu Q. Wang H. Lou J. (2021). Overlying strata fracture and instability process and support loading prediction in deep working face. J. Min. & Saf. Eng.38 (2), 304–316. 10.13545/j.cnki.jmse.2019.0585

16

Pendleton N. Kula K. Giwercman A. Forti G. Bartfai G. Neill T. et al (2022). Ground movement law of high seam longwall extraction in Shangwan coal mine. J. Liaoning Tech. Univ. Nat. Sci.41 (2), 109–113. 10.11956/j.issn.1008-0562.2022.02.003

17

Qi H. Jianhao Y. U. (2018). Rationality of section coal pillar setting and comprehensive unloading technology in deep high stress area. J. China Coal Soc.43 (12), 3257–3264. 10.13225/j.cnki.jccs.2018.0394

18

Qian M. Jialin X. U. (2019). Coal mining and strata movement. J. China Coal Soc.44 (4), 973–984. 10.13225/j.cnki.jccs.2019.0337

19

Tang F. Junyi Z. (2019). Dynamic surface subsidence law caused by mining in adjacent working face. Metal. Mine (10), 8–13. 10.19614/j.cnki.jsks.201910002

20

Wang G. Yang P. (2023). Research on cause analysis and prevention technology of asymmetric floor heave in deep high-stress roadway. Coal Technol.42 (01), 25–29. 10.13301/j.cnki.ct.2023.01.006

21

Wang P. F. Feng G. R. Zhao J. L. Chugh Y. P. Wang Z. Q. (2018). Effect of longwall gob on distribution of mining-induced stress. Chin. J. Geotechnical Eng.40 (7), 1237–1246. 10.11779/CJGE201807010

22

Wang G. Zhu S. Jiang F. Zhang X. Liu J. Xu-You W. et al (2022). Mechanism of pillar-key strata structure instability induced mine tremor in fully mechanized caving face of inclined thick coal seam. J. China Coal Soc.47 (06), 2289–2299. 10.13225/j.cnki.jccs.2021.1316

23

Wang G. Pang Y. Yongxiang X. U. Lingyu M. Han H. (2023a). Development of intelligent green and efficient mining technology and equipment for thick coal seam. J. Min. & Saf. Eng.40 (5), 882–893. 10.13545/j.cnki.jmse.2023.0278

24

Wang Y. Wu G. Kong D. Zhou L. (2023b). Stability analysis of deep stope under repeated mining in close distance coal seam. Coal Sci. & Technol. Mag.42 (8), 32–36.

25

Wang C. Yang Y. Liu Y. (2023c). Asymmetric deform ation mechanism of soft rock roadway under repeated mining and the control technology. Coal Eng.55 (4), 45–51.

26

Yan S. Xue B. (2024). Quantification of key factors for coal wall stability and risk classification under high-intensity mining. J. China Coal Soc.49 (12), 4728–4738. 10.13225/j.cnki.jccs.2023.1468

27

Yan Z. Guo L. Gao L. Xingyuan Li Kou G. (2023). Study on overburden movement and deformation laws under repeated mining in close-distance coal seams. Energy Technol. Manag.48 (04), 17–20.

28

Yang L. I. Yang T. Hao N. Song W. Fu J. Ling Y. et al (2021). Analysis of advancing speed effect in high-intensity mining working face based on stress release rate and microseismic monitoring. J. Min. & Saf. Eng.38 (02), 295–303. 10.13545/j.cnki.jmse.2020.0318

29

Yizhe L. I. Kai Q. I. N. Yin W. Yunpeng L. I. Guan X. Shan-Kun Z. et al (2023). Practice of rock burst prevention with coordinated mining of regional multiple working faces. Saf. Coal Mines54 (02), 92–99. 10.13347/j.cnki.mkaq.2023.02.015

30

Zhang J.-Z. Zhou X.-P. (2020). Forecasting catastrophic rupture in brittle rocks using precursory AE time series. J. Geophys. Research-Solid Earth125 (8), e2019JB019276. 10.1029/2019JB019276

31

Zhang J. Z. Zhou X. P. (2022). Fracture process zone (FPZ) in quasi-brittle materials: review and new insights from flawed granite subjected to uniaxial stress. Eng. Fract. Mech.274, 108795. 10.1016/j.engfracmech.2022.108795

32

Zhang J. Mingzhong L. I. Zhengkai Y. Tijian L. I. Yongxiang X. U. Mingsheng Z. et al (2021). Mechanism of coal wall spalling in super high fully mechanized face and its multi-dimensional protection measures. J. Min. & Saf. Eng.38 (3), 487–495. 10.13545/j.cnki.jmse.2020.0140

33

Zhang J. Z. Zhou X. P. Du Y. H. (2023a). Cracking behaviors and acoustic emission characteristics in brittle failure of flawed sandstone: a true triaxial experiment investigation. Rock Mech. Rock Eng.56 (1), 167–182. 10.1007/s00603-022-03087-0

34

Zhang J. Dong X. Haitao C. Lei Y. Shankun Z. Qian W. et al (2023b). Structure evolution and rock burst prevention under multi-working face mining in geological anomaly areas. Coal Sci. Technol.51 (2), 95–105. 10.13199/j.cnki.cst.2022-1468

35

Zhang C. Cai L. Wang W. Huabin C. Zou Y. Wenzhi Z. (2024a). Mechanism of overburden and surface movement under high-intensity repeated mining. Metal. Mine (07), 173–180. 10.19614/j.cnki.jsks.202407024

36

Zhang G. Zhang G. Zhou G. (2024b). Collaborative response of surface subsidence and strong mine tremors under continuous multi-working-face mining. J. Min. Strata Control Eng.6 (1), 117–130. 10.13532/j.jmsce.cn10-1638/td.20240010.001

37

Zhao J. (2000). Applicability of Mohr-Coulomb and Hoek-Brown strength criteria to dynamic strength of brittle rock materials. Int. J. Rock Mech. Min. Sci.37 (7), 1115–1121. 10.1016/S1365-1609(00)00049-6

38

Zhi Y. A. N. Wang Q. Liang L. U. (2016). Prevention of rock burst and numerical simulation research in deep mining face. Coal Technol.35 (02), 35–37. 10.13301/j.cnki.ct.2016.02.013

39

Zhipeng K. Guofeng Y. U. Luo Y. Changrui D. Jing Z. (2023). Study on overlaying rock failure law of repeated mining in extremely close coal seam group by similar simulation test. Min. Res. Dev. Ment43 (5), 56–62.

40

Zhou X. P. Zhang J. Z. (2021). Damage progression and acoustic emission in brittle failure of granite and sandstone. Int. J. Rock Mech. & Min. Sci.143, 104789. 10.1016/j.ijrmms.2021.104789

Summary

Keywords

coordinated mining, multi-working face, numerical simulation, plastic zone, stress evolution

Citation

Bai X, Yuan Q, Jiang Q, Song J, Chen Z and Liu X (2026) Study on the evolution laws of overlying strata stress and mining-induced fracture zones under coordinated extraction in multi-working face areas. Front. Earth Sci. 14:1738703. doi: 10.3389/feart.2026.1738703

Received

03 November 2025

Revised

22 December 2025

Accepted

02 January 2026

Published

16 January 2026

Volume

14 - 2026

Edited by

Binbin Yang, Xuchang University, China

Reviewed by

Nan Xiao, Changsha University of Science and Technology, China

Longfei Wang, Henan Polytechnic University, China

Updates

Copyright

© 2026 Bai, Yuan, Jiang, Song, Chen and Liu.

This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Qiang Yuan, qiangyuan@cqu.edu.cn

Disclaimer

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.