- 1Research Group Exercise and Sport, Zurich University of Teacher Education, Zurich, Switzerland

- 2Sports Office City of Zurich, Competence Center Physical Education, Zurich, Switzerland

- 3Centre for Teaching Professions and Continuing Professional Development, Zurich University of Teacher Education, Zurich, Switzerland

Introduction: Physical inactivity represents a global challenge that calls for early intervention, particularly during childhood. Schools are uniquely positioned to influence children’s current and future physical activity behaviors. The introduction of all-day schools creates an opportunity to integrate diverse sports-oriented activities throughout the school day. In Zurich, the implementation of all-day schools in primary schools led to the development and evaluation of extended educational programes, with a particular emphasis on physical activities, with the aim of contributing to holistic and sustainable health promotion. These activities included optional programes during lunch breaks and before, between, and after lessons, aimed at fostering both subject-specific and interdisciplinary competencies.

Methods: To evaluate the activities, both qualitative and quantitative methods were used, comprising semi-structured interviews with school principals and extended educational services principals and student questionnaires.

Results: The evaluation revealed high levels of participation, particularly in physical activities including the Open Gym and mobile facilities.

Discussion: The findings demonstrate the leading role of physical activities including teacher-led and child-driven options in extended educational programs.

1 Introduction

During childhood, physical activity, exercise and play are essential for the healthy development of children (Stodden et al., 2008; Hulteen et al., 2018). Physical activity in both informal settings and organized sports is important for lifecourse health, and the World Health Organization (WHO) recommends at least 60 minutes of moderate to vigorous physical activity per day for children and adolescents (Chaput et al., 2020; Chalkley and Landais, 2022). School is an important context for promoting extended educational activities, including physical activity (Sallis et al., 2012; Bailey et al., 2023), where theoretically, all children can be reached, including those who are less active and have lower motor competencies.

However, the daily lives of children and adolescents are increasingly shaped by additional activities which reduce the time available to them to freely organize their activities outside of school (Chiapparini et al., 2018). Extended educational services are seen as part of extended education, which includes school-based extended educational activities, extended educational activities by outside partners and collaborative activities by school and outside partners (Bae, 2018). As children spend most of the day at school, extended educational services schools should also take responsibility for promoting physical activity through extended educational activities (Neuber, 2020; Naul and Neuber, 2021). This is a key concern as the daily lives of many pupils are characterized by a lack of physical activity (Finger et al., 2018; Bailey et al., 2023). According to Neuber (2020), sports activities comprise the largest proportion of extended educational activities in schools.

The physical activities belong to the category of school-based extended educational activities conducted within the school context. They are organized by the school, even when some activities take place off-site, either directly offered by the school’s teachers or by other school staff or professionals from the field of extended education (Bae, 2018).

Extended educational services have the potential to develop and implement appropriate and varied extended physical activity and sports programes for children and young people (Neuber, 2008; Züchner, 2014; Webster, 2023). The extended educational services at schools referred to here offer opportunities to stimulate interest and enjoyment in physical activity at an early age. As they take place in the school grounds but after the lessons, they are designed to reach children who may not have access to an active lifestyle at home (Noetzel et al., 2024). The activities intentioned as a new type of intervention at the intersection of sport and social pedagogy as they do not request formal participation and subscription, are non-selective and open to every student. In particular, the rhythmization of the school day through movement is emphasized, as well as the informal social interaction among children. There is potential for individual support, especially for children with a lack of experience of movement or for young people showing aptitude for sport, as access to sports clubs is often limited, especially for non-athletic students (Pate et al., 2006).

As the provision of institutionalized extended education at school becomes increasingly important in Switzerland (Chiapparini et al., 2016), extended educational services at schools are assuming responsibility for developing appropriate and diverse activities for children and young people in the hours outside of the formal academic day.

It is recommended that extended educational services provide non-formal and informal contexts, such as organized or guided extended physical activities, as well as informal free play in the playground during breaks (Reimers et al., 2018) or in institutionalized extended educational service times at school. Physical activities during extended education service times play a crucial role in promoting physical activity among children, not only because they provide additional opportunities for exercise, but also because they contribute to the social and emotional development of children (Riiser et al., 2019; Webster, 2023). Theoretically, activities in extended educational services are based on the self-determination theory (SDT), serving an individual’s basic needs for intrinsic motivation and overall wellbeing (Ryan and Deci, 2000). These needs include autonomy, competence and relatedness (i.e., forging positive inter-personal relationships). A supportive learning environment, characterized by student autonomy, choices, recognition, and clear explanations regarding the importance of physical exercise significantly contributes to the satisfaction of individual basic needs (Paap et al., 2025). The experience of autonomy, competence and relatedness in sports activities as part of an extended educational programe thus contributes to the promotion of a sustainably health-conscious lifestyle.

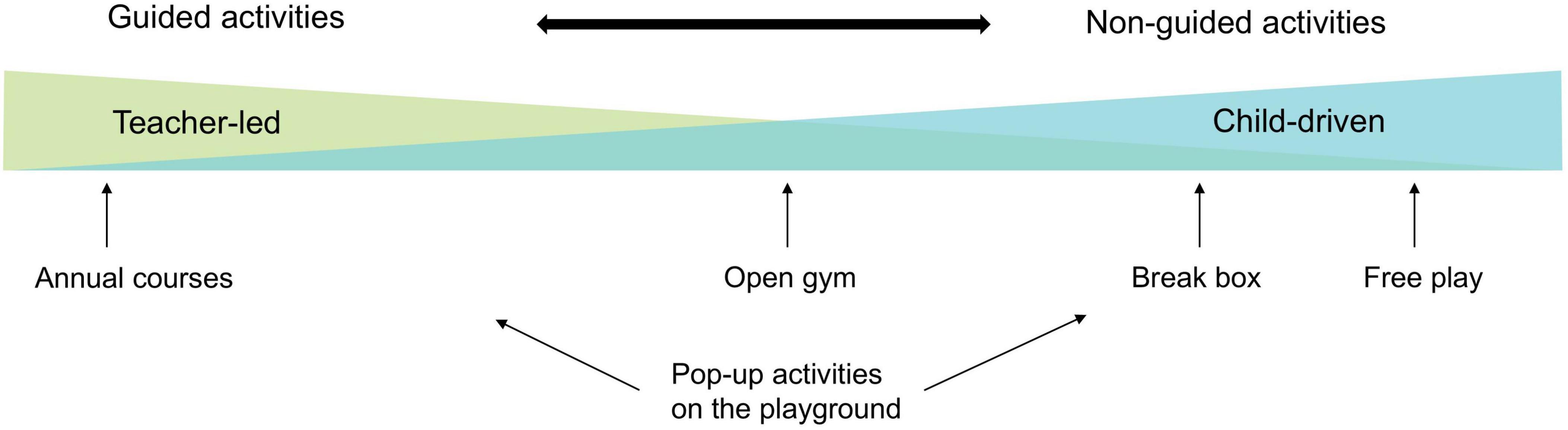

In extended educational contexts different temporal and spatial contexts are encouraged, in which children have the opportunity to meet and move according to their needs and abilities. Promoting autonomy and participation to promote relatedness. Therefore, activities should not generally be competition-oriented but offer low-threshold opportunities for physical activity and social encounters (see Figure 1). They represent an innovative field of learning and interaction that differs from both compulsory physical education and recreational or club sports. They serve as a form of social infrastructure for students, enabling them to connect their school experiences with their personal lives through the activities offered (Ferrari et al., 2023). Consequently, educators in these activities should adopt an individualized approach, considering students’ abilities and preferences, offering them choice as well as a self-determined degree of participation and peer-relatedness.

All these activities are to be understood as components of a comprehensive school programe for physical activities, such as the American framework “Comprehensive School Physical Activity Program” (CSPAP) (Society of Health and Physical Educators, 2024), the Swiss model “Bewegte Schule” (Schulgruppe BASPO, 2010) or the programe “Schule Bewegt” (Swiss Olympic et al., 2018). CSPAP is the most-globally recognized model. It is a comprehensive framework for promoting physical activity in schools, developed in the United States by the Society of Health and Physical Educators (SHAPE America). In addition to the recommendation of 60 min of physical activity per day (World Health Organization, 2010), the model also emphasizes the development of knowledge, skills, and confidence necessary to support lifelong physical activity. The framework highlights the importance of strong coordination of and synergy between all of its components: physical education, physical activity before and after school (extended educational programs), physical activity during school, staff involvement, and family and community engagement (Carson et al., 2014). The Swiss model “Bewegte Schule” aims to support schools in planning, implementing and evaluating physical activity interventions according to temporal (before/after school) and structural (in school-in class) criteria (Schulgruppe BASPO, 2010). The national programe “Schule Bewegt” has also provided a comprehensive synthesis of proposals for physical activity breaks in the classroom to encourage teachers to integrate at least 20 min of physical activity into their lessons every day (Swiss Olympic et al., 2018).

Compared to the wider field physical education, research on extended educational activities at schools is in its infancy (Demetriou et al., 2017; Webster, 2023; Bailey et al., 2024). Further (child -oriented) research is required to gain insight into the processes involved in the successful implementation of comprehensive school physical activities in different school contexts. The current literature is still in its early stages, and more evidence is needed to support the development of effective practices (Webster, 2023) and to understand the role of the physical activities during the school day.

In contrast to the parameters of club activities, participation in these activities should not be limited to a specific class or group to increase the child’s autonomous choice in terms of in what and with whom they participate. It is recommended that children and young people from diverse backgrounds be included in extended educational activities as it is acknowledged that optional school sports courses have the potential to engage children who are less active than their peers in club activities, and to attract a slightly higher proportion of girls than other organized sports (Lamprecht et al., 2021). The aim of this article is to analyze the role of physical activities during school days. With the implementation of extended educational services in primary schools and the establishment of all-day schools in the city of Zurich, extended educational services developed a variety of activities that provided non-formal and informal learning opportunities. Alongside other cultural and aesthetic educational programs, physical activities became central elements in the design of extended educational programs at school. Physical activities during lunch breaks and before, between, and after lessons were developed and evaluated to combine subject-specific and interdisciplinary competencies, complementing both family and school activities. The evaluation of the extended educational physical activities, guided by the following research questions, provided the basis for the data analysis presented in this article:

• How is the role of physical activity (PA) offerings perceived in the context of all-day schools?

• What are the patterns of use and the reasons for participating in PA?

• What are the facilitators and barriers for the effective implementation of physical activity offerings in the context of all-day schools?

These research questions provide a structured framework for an in-depth exploration of the topic and a nuanced analysis of the data collected.

2 Materials and methods

The research questions were examined within the framework of two studies Sport in school environment —a School Development Study and the in-depth Open Gym Study. The context of the city of Zurich is introduced first, followed by a concise presentation of both studies. Subsequently, the methods of data collection for analysis for each study are described.

In the city of Zurich, the implementation of all-day schools is being continually expanded. As extended educational activities are increasingly becoming part of the school day, new activities need to be developed and evaluated. In this context, our studies focused on physical extended educational activities.

2.1 Study 1: school development study

Various physical extended educational activities to support all-day schools were implemented between 2019 and 2021. The sports department of the city of Zurich invited all-day schools to participate in the project, and the aim and the content of the projects were presented online. A total of 14 schools registered as pilot schools to participate in the school development study. The goal of the project was to develop, implement and evaluate extended educational physical activities that were offered across the 14 public all-day schools in Zurich. The aim was to offer physical and sports activities during the lunch break as well as before, between and after the compulsory lessons. The activities, which were free of charge and open to all children were designed as a leading example of the interlinking of subject-specific and interdisciplinary competencies and supplementary to children’s lives. Different types of activities selected by the school were available. Activities took place weekly throughout the school year. Schools could choose from a range of activities, such as multi-sport activities (“games, fun and sport”) or sport-specific options, like dancing, football or tennis, which were led by professional sports coaches. The Open Gym during lunchtime offered a mix of free-play and structured sports opportunities on demand. Mobile facilities such as a pump track, a skate park, street soccer and parkour were set up in the school’s outdoor playgrounds and remained in place for between 4 weeks to 3 months, depending on the school’s needs.

2.2 Study 2: in-depth study open gym

The evaluation of the Open Gym focused on the usage and how the programe was used. An in-depth qualitative study was conducted on the extended educational programe Open Gym in 2022. The Open Gym provided added value to the extended educational program not only inclement weather but also through the specific play and exercise options. The aim was to provide pupils with an offer that met their individual basic needs and interests and that they could also shape. The Open Gym offered a variety of opportunities characterized by different degrees of management; the influence of the adult leader(s) present ranged from ensuring safety by supervising completely self-initiated activities to actively supporting the organization, structuring the movement space and (partly) selecting and specifying activities.

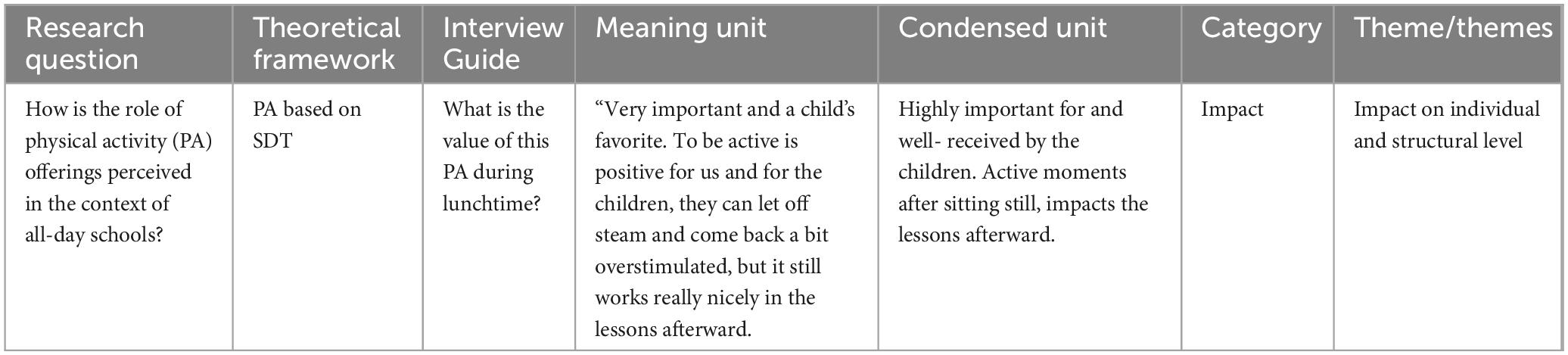

In this article the empirical data is driven by the longitudinal School Development Study (2019-2021) and the evaluation of the in-depth study Open Gym (2022). In both studies, a mixed-method approach (qualitative and quantitative data collection) was used, which is outlined in Table 1.

Table 1. Characteristics of the school development project and the in depth-study Open Gym and the methodological approaches.

2.3 Data collection

2.3.1 Qualitative data collection

After 2 years of experience in the School Development Study, the interviews were used to evaluate the impact of the implementation of the range of physical extended educational activities in all-day schools. In particular, the interviews focused on the activities themselves, their impact, the quality of the provision and the future development of the physical extended educational activities in all-day schools. Moreover, this study was concerned with the impact of the school context, the aims and impact of the activities, the school culture regarding the cooperation between professionals, the children’s wellbeing but also tensions between the stakeholders, and the pace of the children’s day regarding the transitions between school and extended educational activities. The interviews were conducted face-to-face following a semi-structured interview guide (Ferrari et al., 2022). The average duration of the interviews was 56 min (range = 39-76 min).

In the in-depth study Open Gym, the qualitative interviews took part in five schools with the principals of extended educational services and lasted approximately 60 min. The aim of the interviews was to consider the specific circumstances and unique characteristics of the Open Gym in each school and to capture the experiences of the principals of extended educational services. A semi-structured interview guide was used, which contained questions about the organization, aims and perceived impact of the Open Gym during lunchtime.

In both projects, the participants were informed about both the aims of the interviews and the wider study, as well as the data security of the audiotaped interviews.

2.3.2 Quantitative data collection

In the School Development Study, the questionnaire for the second grade pupils was administered in an analog format using pen and paper (Ferrari et al., 2022). Project staff visited the classes of the participating schools to distribute questionnaires, explain the survey’s purpose, and guide the students through the questionnaire. The questionnaire for the fifth grade pupils was administered in an online format. The link to the questionnaire was sent to the head of the participating schools with a request to forward it to all fifth grade teachers. Teachers were asked to allocate 20-30 min of a regular school lesson for their students to complete the questionnaire. As the questionnaire was not mandatory, there were missing data for school-level reasons (e.g., the principal did not forward the questionnaire to the teachers), for class-level reasons (e.g., the teacher did not have the pupils complete the questionnaire) or for individual-level reasons (e.g., the pupils did not complete the questionnaire).

The quantitative questionnaire in the in-depth study Open Gym was conducted for all children attending the school, using different questionnaires for younger (grades 1-2) and older (grades 3-6) children according to developmental appropriateness. As the children from first and second grade had lower reading levels, the questionnaire took part in the form of a standardized interview. The survey was conducted by a staff member from the Zurich University of Teacher Education who interviewed the children in small groups (approximately three children per group) during the lunchtime activity of the Open Gym. The children were asked six questions about the Open Gym, which they answered using three visual “smiley” categories. They could choose whether they agreed, partially agreed, or disagreed with the statement (Ferrari et al., 2024). For each question, the children placed a piece of paper with the chosen “smiley” in an envelope corresponding to the question being read out. Each group of children could not see the responses of the previous group. The questions covered significant aspects of the self-determination theory related to the activity and included their overall appreciation for the activity, the student’s participation and the student’s relatedness (example: “I like being in the Open Gym,” “We do cool things” or “I move a lot and can try new things”). In third and sixth grade, the questionnaire was completed by the pupils during regular class time shortly before the summer break. Schools either received the questionnaires in paper form or were provided with a QR code, allowing students to complete the questionnaire online (Sportamt Stadt Zürich, 2023). This flexibility of format enabled schools to integrate the survey into their existing daily schedule. The questionnaire contained questions about participation in the Open Gym as well as participation in other extended educational activities to explore the aspect of the individual basic needs, relatedness, autonomy and competence (Ryan and Deci, 2000).

2.3.3 Participants

In the School Development Study, 14 elementary schools participated. School principals participated in the qualitative data collection in the form of interviews. The quantitative questionnaire was filled out by all children of the second grade present on the day of the data collection (n = 402, M = 8.1 years, SD = 0.42, 43.5% girls, 56.3% boys, 0.2% diverse) out of 12 schools and children of the fifth grade, whose teachers asked them to complete the questionnaire (n = 299, M = 11.8 years, SD = 1.1; 51.8% girls, 47.2% boys, 1.0% diverse) out of 12 schools.

In the in-depth study Open Gym, qualitative interviews took place with the principal of extended educational services in the five participating schools and lasted on average for approximately 60 min. In total, first and second grade children (n = 101, M = 7.83 years, SD = 0.84, 45.5% girls, 54.5% boys, 0% diverse) from four different schools participated in the quantitative survey. From third to sixth grade, the questionnaire was filled out by children (n = 379, M = 10.49 years, SD = 1.21, 51.3% girls, 47.9% boys, 0.8% diverse) from three different schools.

2.4 Data analysis

2.4.1 Qualitative data analysis

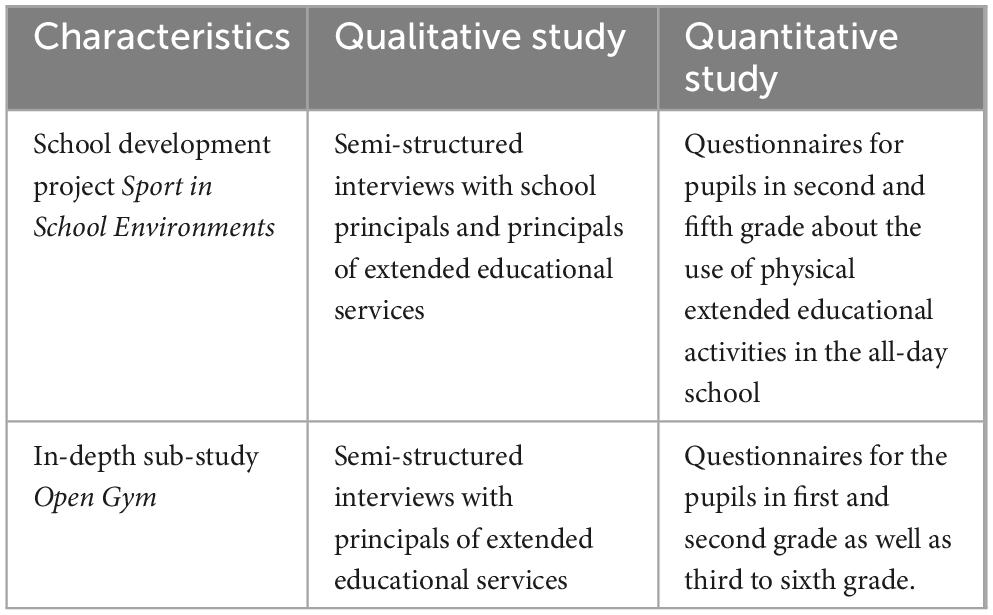

The interviews in both projects were recorded and transcribed. For data coding and the analysis, the software MAXQDA 22 (Verbi Software GmbH, 1989-2024) was used. In both projects, qualitative content analyses were conducted according to the methodological approach of Mayring and Fenzl (2019). After transcription, the themes and patterns in the interviews were identified. The categories were identified deductively based on the research questions, the theoretical framework and interview guide and inductively supplemented based on the data (see Table 2). The data were counter-coded until discrepancies among the ratters could no longer be detected.

2.4.2 Quantitative data analysis

The quantitative data analysis was performed using SPSS (IBM Corp., 2023), with descriptive statistics being calculated. In the sports programe, children had the option to participate in specific physical extended educational activities based at school. To classify the activities by sport type, broader categories were established to form, “dance,” “multi-sportive courses,” “gymnastics,” and “ball sports.”

3 Results

3.1 Physical extended educational activities as an important element of school development

“We see it as a way of offering sports in an open and inclusive manner. There are programes designed for specific target groups, but there are also opportunities where, for instance, the gymnasium is simply made available for everyone to join in. In the playground, we also provide pop-up facilities such as a skate park or a pump track. For us, these are all pieces of the puzzle that contribute to creating an active school.” (School Principal, S11_t2_Pos. 57)

Regarding the physical extended educational activities, our analysis revealed four main categories: aims, quality, impact and conditions for success. In summary, the interviews revealed that the physical extended educational activities were well-selected and generally well-received. Activities, like the Open Gym and the mobile facilities were especially popular and actively used, even during the compulsory Physical Education lessons. The pupils developed creative solutions to manage equal participation, such as developing a button registration system for mobile facilities.

3.1.1 Activities and quality

In the following sections, the quality dimensions of the physical extended educational activity of the School Development Study are presented, based on guided interviews at the end of the project.

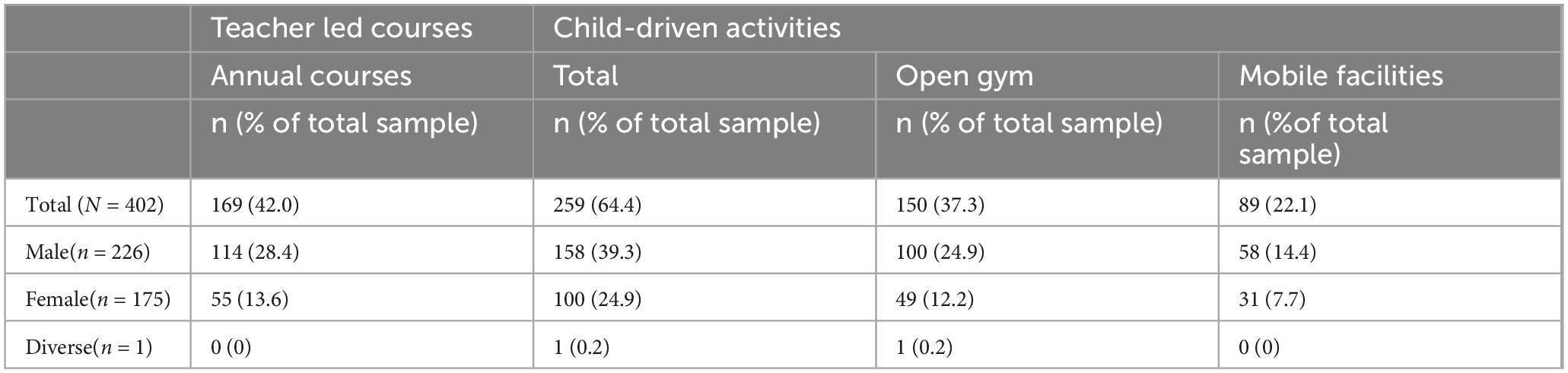

In second grade 41,8% children (n = 170) participated in the year-round courses. Out of the boys (n = 226), half participated in year-round courses (n = 114), resulting in a participation rate of 50%. For girls (n = 175), 55 took part, reflecting a participation rate of 31%. In the child-driven activities, 70% of the boys (n = 158) and 57% of the girls (n = 100) participated (Table 3).

Table 3. Usage of the physical extended educational activities in second grade (data based on the questionnaire, n = 402).

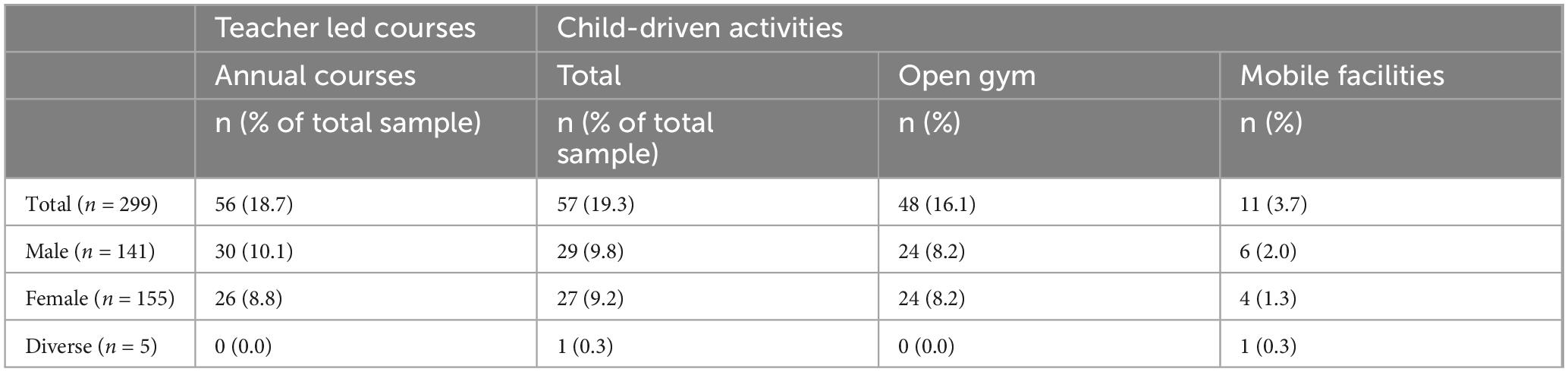

Table 4 shows the usage of physical extended educational activities by the children of the fifth grade (n = 299) who participated in the quantitative data collection. The year-round courses were attended by nearly one fifth of children (n = 56, 18.7%) of the total sample, which means that a smaller percentage of fifth-grade children attended the annual courses, in comparison to the second-grade children.

Table 4. Usage of the physical extended educational activities in fifth grade (data based on the questionnaire, n = 299).

In total, the physical extended educational activities were more popular among second-grade pupils than in fifth-grade pupils. While 42% of the second-grade children attended the year-round courses, only 18.7% of the fifth grade pupils attended the year-round courses. This could also be observed within the child-driven activities. These were engaged with by 64.4% of the second-grade pupils, but only by 19.3% of the fifth-grade pupils. The various activities were discussed in the qualitative interviews, as described in the following section.

3.1.2 Year-round courses

“I think it contributes to equal opportunities or equity that there are not only programes that cost money but are also free of charge. I think that is very important, otherwise there is a two-tier society within a school and that goes against our desire to be one unit.” (Extendend Educational Principal, S5_t1_Pos. 12)

This excerpt highlights that school principals prioritize the annual sport courses, because they were free of charge as opposed to organized sports clubs. The interview participants assumed that the number of enrollments was partially influenced by children’s social background and the sports infrastructure in their communities. Schools where many children were already involved in private extracurricular activities (e.g., sports, music, or arts) saw lower attendance in year-round courses than schools where children were not involved in private provision due to infrastructure or socioeconomic reasons.

“We need different year-round courses for different ages – the younger ones should have diverse experiences.” (School Principal, S3_t3_Pos 15)

Year-round courses in lower grades were generally broad and often focused on multisport activities, with a strong appreciation for them as they provided a contrast to compulsory Physical Education lessons due to the multi-age characteristics of the groups of children, instructors leading sessions instead of teachers, and the content of the activity. In upper elementary school, more specific courses became popular, and course offerings were influenced by current trends and local sports infrastructure.

“I need experts in these courses, real basketball players, dancers, professionals that know the sports well, who become part of the school and showcase their performances at the end of year party.” (School Principal, S1_t3_Pos 6)

Several factors contributed to the success of the year-round teacher-led courses. Key among them was the well-trained and highly professional leadership. Cooperation between course leaders and school staff was also important to ensure smooth transitions between lessons and extended educational activities, with good collaboration leading to consistent participation. Establishing continuity in year-round courses and maintaining the same leadership helped to build a sports culture and relationships with instructors. Courses of varying skill levels allowed students to progress over multiple years, improving their skills (e.g., in dancing). Effective communication with parents and pupils, such as presenting the year-round courses in class or offering trial days, also played a role in promoting enrollment. In some schools, parents were supported with online registration or translation of key documents, which led to higher attendance.

Specific organizational factors however, hindered the success of year-round courses. Neighborhood characteristics needed to be considered during course selection, as an oversaturation of a particular activity could result in low attendance. For younger children, getting to the course location was sometimes problematic, though this was addressed at some schools by asking the course leaders to escort the children. At other schools, schedule coordination was difficult, particularly when transitions between classes and courses were too tight or courses were scheduled in the afternoons during regular lessons.

3.1.3 Open gym

“They have the opportunity to go to the Open Gym during the lunch break. That is an offer that is used very well.” (Extended Educational Principal, S9_t2_Pos. 50)

The Open Gym was generally seen as a positive offering. It was noted that children played there differently compared to outdoor activities or compulsory Physical Education classes, making it a distinct experience. The programe allowed for varied participatory activities. Different organizational forms were observed depending on the Open Gym’s setup, and by creating movement landscapes, children could engage in free play. The mixing of classes and age groups led to a different dynamic than was observed during regular class time or breaks. Involving pupils in decision-making was seen to enhance their social and personal competencies.

“But then, because it’s a child’s favorite, everybody showed up at the Open Gym and we had to find a way to avoid pure chaos and make it possible that children could play a game.” (Extended Educational Principal, S2_t3_Pos.34)

Initially, some schools had no limit on the number of participants, leading to overcrowding (up to 150 children in some cases) and difficulty managing the programe. To address this, creative solutions were introduced, such as a “button system” for children to sign up for midday activities. Each child was given a button in the morning to place on the board with the different activities in order to register for the activity they wanted to attend during lunchtime (e.g., Open Gym, library, etc.).

The success of the Open Gym relied heavily on well-trained staff capable of managing large groups, support from the sports department (i.e, expert advice), and a balance between more organized activities and free play. Challenges arose when participation was unrestricted, leading to a mix of age and competence levels, which could result in either cooperation with or domination by older children. Managing these heterogeneous groups required skilled staff and was often resolved by splitting children into different days or time slots. Additionally, access for preschool children was limited due to the decentralized location of preschool on school grounds.

3.1.4 Mobile facilities

“The designs painted on the playground also play an important role in some school buildings. Additionally, we are fortunate to have created an exceptionally attractive playground, thanks to the pump track and other initiatives we have implemented.” (School Principal, S6_t2_Pos. 56)

Generally, the mobile facilities were very popular among students and were used frequently. Children developed their own rules (e.g., using the skatepark twice before stopping at a designated point) to ensure everyone could have an opportunity to take part. They regulated their learning process individually, initially observing before trying out the facilities themselves. Even children who were usually less active increased their activity levels and developed a desire to compete with their peers. Notable motor competence improvements were observed in all children.

A key advantage of the mobile facilities was their support for self-regulation and peer interaction, with an inclusive character. A positive link was found between the training of teachers and extended educational staff and the use of the facilities. When teachers and extended educational staff participated in the introduction, the facilities were more likely to be used in extended educational activities and Physical Education classes. Proper introduction to the equipment also helped pupils become “multipliers,” teaching other children how to use the facilities effectively. Additionally, the facilities were popular with the public outside school hours and at weekends, acting as a “neighborhood magnet” due to their location on school grounds, which allowed free and local access.

Due to limited school areas or available space, the mobile facilities could not be deployed across all schools. In some cases, they were placed on existing sports areas, like a basketball court, rendering these areas unusable for their normal purpose. The optimal usage period was identified as between 4 and 6 weeks.

3.1.5 Recess area

“The recess box is something we use daily. We are not even noticing it, it became so natural to use it. The only problem is the gathering when the break is over, we have to remind the children to store the stuff in the box again and not just run back to the classroom.” (Extended Educational Principal, S6_t2_Pos 41)

The school’s outdoor areas were used in a variety of ways. Each school had a bicycle course that could be used by bicycles or other wheeled play vehicles. Some schools also had playgrounds, basketball or football fields, chess boards, or other demarcated areas.

Typically, a “recess box” was available in the playground or a classroom, allowing children to freely take materials to play with. These boxes were used both outdoors and indoors, with different organizational approaches observed. At some schools, a teacher or supervisor distributed the materials, while at others a class took turns managing the box each week. In addition to small play equipment, ride-on vehicles like go-karts were especially popular. Available throughout primary school, these provide continuous engagement, offering an appealing way to improve motor skills without stigmatization. The recess box was child-oriented and needs-based, with no explicit learning goals, but it was used to guide children in overcoming poorer motor skills (e.g., those skills required for biking, balancing, and ball games) and to interact with each other.

The active involvement of Physical Education teachers, school principals and principals of extended educational services was crucial in designing an attractive playground, especially when it came to managing sports equipment or applying for funding to make infrastructure improvements.

3.1.6 Perceived impact of the physical extended educational activities

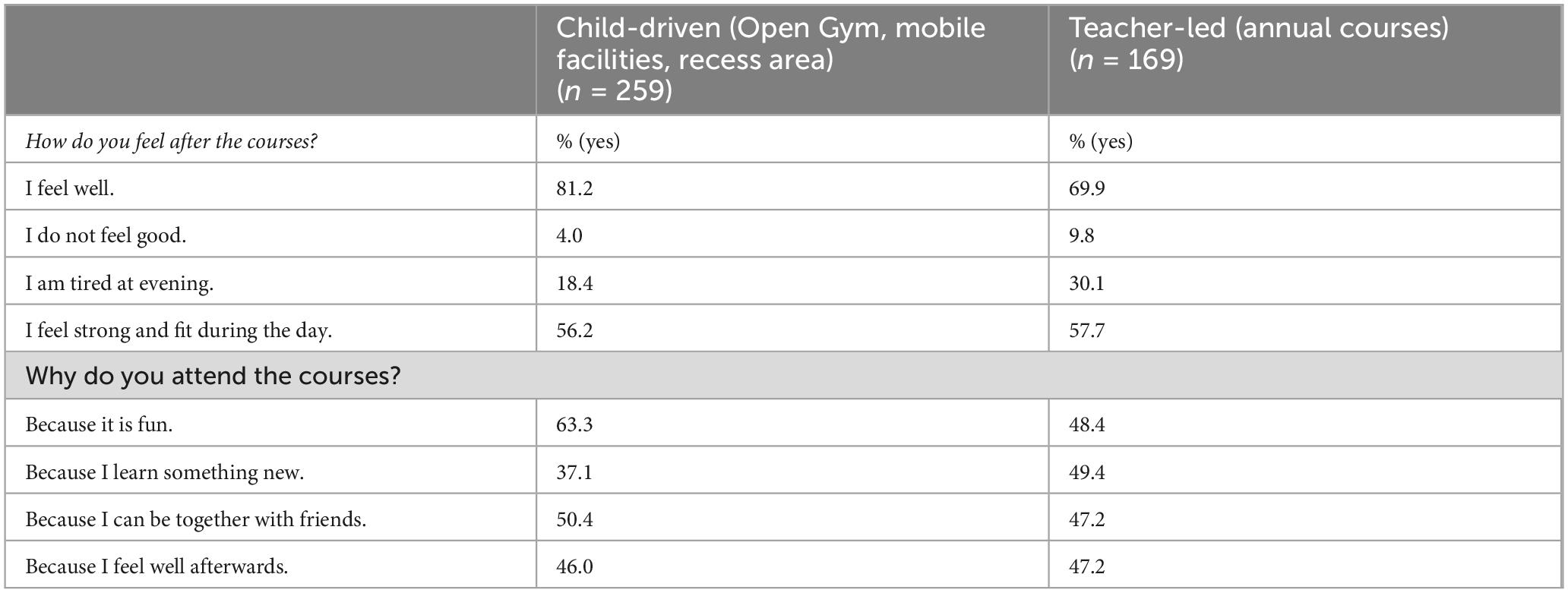

The children who participated in the teacher-led and child-driven activities were asked for the reasons as to why they participated in the activities. The questionnaires for the second- and fifth grade children differed in complexity due to developmental appropriateness. While the children in second grade class were asked how they feel and why they participate in the teacher-led and child-centered physical extended educational activities in general, the children in fifth grade answered the question why they participate in the activities separately for the different activities (Ferrari et al., 2022).

For those in the second grade, there were initial filter questions in the questionnaire. First, they could tick which year-round courses they attended, for which the name of the year-round course was school-specific. After that, they answered both questions about the wellbeing after the course and the reasons why they participated in the course by ticking the boxes.

Table 5 shows the result of the second-grade children regarding their wellbeing after the year-round courses and the reasons for their participation. Overall, they “felt well” after the courses. Differences were observed between the teacher-led and child-centered courses regarding the reasons for their participation. The reason “because it’s fun” was given more often by children in child-led activities (63.3%) than in teacher-led activities (48.4%), while children in teacher-led settings (49.4%) wanted to learn something new more often than children in child-led settings (37.1%).

Table 5. Wellbeing after and reasons why second-grade children participated in the physical extended educational activities, analyzed separately according to teacher-led and child-centered activities.

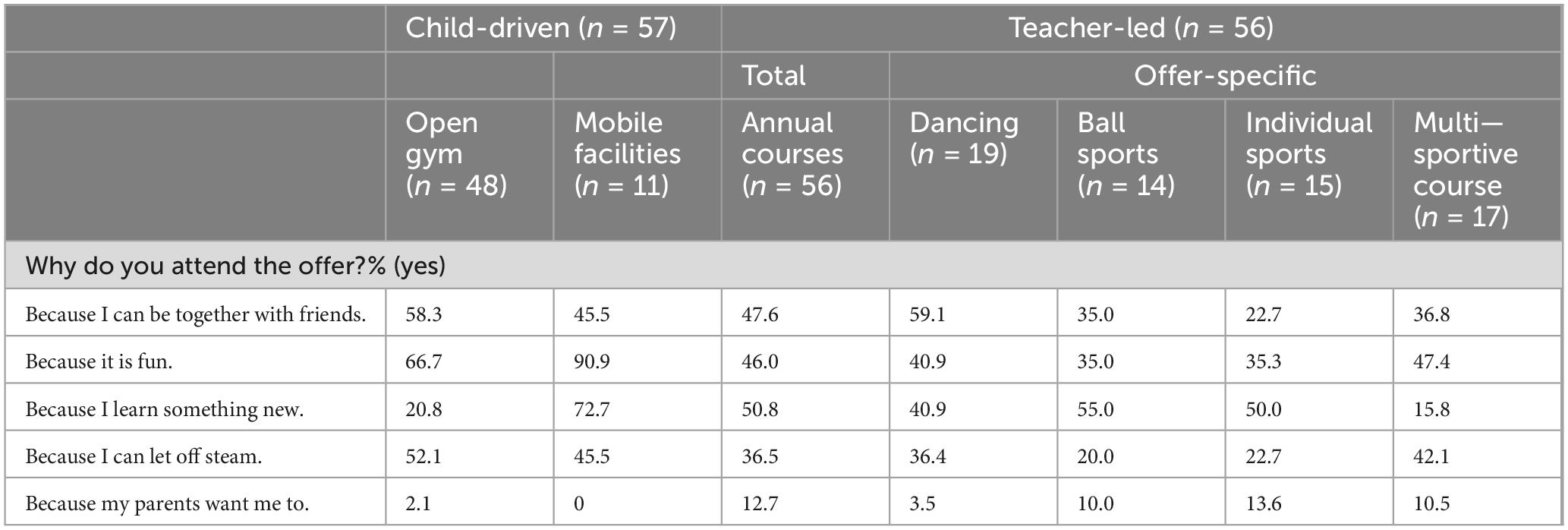

For the fifth-grade participants, the questionnaire also contained filter questions. The children could select the reasons for choosing each individual activity, which is shown in Table 6. As for child-centered activities, they could choose the Open Gym and mobile facilities, whereby the teacher-led activities contained the school-specific year-round activities. The year-round activities were then categorized as “dancing,” “ball sports,” “individual sports,” and “multi-sportive courses.”

Table 6. Reasons why the fifth-grade children participated in the physical extended educational activities (in percent).

Among fifth-grade pupils, the reasons for the attendance in child-driven activities were different for the Open Gym and the mobile facilities. In both activities, children wanted to be together with their friends and “let off steam.” Children used the mobile facilities because it was fun (90.9%) or they learned something new (72.7%). In the year-round courses, the reason “because it is fun” and “I can let off steam” has been less often cited. Within the year-round courses differences regarding the reasons for the attendance were also found. While 59.1% of the children attended the dancing courses because they wanted to be with their friends, the percentage of the children in individual sports was lower (22.7%). In the multi-sport course, only 15.8% went because they “learned something new,” while the reason “to learn something new” was higher in ball sports (55.0%).

Alongside the questionnaires for the children, the perceived impact of the physical extended educational activities was also discussed in the qualitative interviews with the school principals. The impact was observed on both individual and school levels. On an individual level, there was an observed increase in pupils’ self-esteem and autonomy. Through surveys and votes in class councils, pupils were able to express their preferences for new activities, enhancing their participation. At some schools, the effects were visible in pupils’ behavior. Pupils tended to be calmer and more balanced, especially when they engaged in physical activities during lunch breaks.

“We are convinced that the children are calmer if they can move around outside during the lunch break. They come to the afternoon lessons much more relaxed. As soon as the weather is bad or cold and they can’t go outside, things get restless. That is an interesting observation.” (School Principal, S1_t2_Pos. 100)

This effect was particularly pronounced on wet days, as restlessness grew in the afternoons when outdoor activities were limited. Group dynamics in schools also shifted, as activities were offered to multiple classes and grade levels, mixing students in settings such as the year-round courses, the open sports hall, and mobile facilities. As a result, students took part in cross-grade and cross-class socializing.

The qualitative interviews highlighted both subject-specific and personal/social competence development as goals, and in addition, “that children have a place where they can be physically active, let off steam, and also engage in something meaningful” (S9_t3_Pos. 84). These goals included integrating physical activity into daily life, improving motor and sport-specific competencies, fostering students’ autonomy through a choice of extended educational activities, and strengthening self-regulation and conflict resolution skills in the context of group play. During the project, additional physical extended educational activities were developed to meet the specific needs of both students and school staff. One example was the year-round course “calm down—multi-sportive course,” which balanced activities that pushed students to their limits with opportunities for relaxation and retreat. Another key goal was promoting equal opportunities. Free and easily accessible year-round courses aimed at reaching children who, due to financial barriers, lacked access to organized sports. In some schools, teachers and extended educational services supported the enrollment process by offering recommendations to parents.

3.2 In-depth study open gym

As the principals valued the physical activities during lunch as a child-led physical activity that had an impact on children’s behavior in the afternoon, this activity was evaluated in depth using both qualitative interviews with the principals of extended educational services and quantitative analyses of questionnaires for the pupils (Sportamt Stadt Zürich, 2023).

3.2.1 Programme and organization

“The Open Gym is an activity we would not be without any more, it’s a highlight and offer that constantly takes place and an opportunity for much more than just playing a game together. It’s not an easy offer though.” (Extended Educational Principal, S7_t3_Pos 62)

At some schools, the Open Gym was open during lunchtime every school day, and in other schools only 2 days per week. The children could also participate in extended educational activities other than the Open Gym such as the library, open classrooms with handicrafts or play-based activities. The registration for the Open Gym was also organized in different ways. At some schools, children had to register during the morning or directly before the lunch break, with the help of a button system, whereas at other schools no registration was necessary. At some schools, the children could come and go during the different activities and in other schools the children were expected to stay during the entire lunchtime once they signed up. The Open Gym was available to all children regardless of age or class level.

Whereas some schools opened the Open Gym for free play, other schools offered teacher-supervised activities, like soccer, or offered mixed formats by separation the gym hall into different areas. The content of the activities in the Open Gym was also dependent on the leader who was in the Open Gym. These were usually professionals from the sport office and staff from the extended educational services.

3.2.2 Quality and importance of the open gym

The interview partners from all schools rated the Open Gym as an important activity, which was appreciated by the parents and very popular among the pupils and almost always fully booked to capacity. The quality of the Open Gym was rated in different ways. The Open Gym should be structured, with a start and an end point, e.g., warm up, practicing, play and a cool-down. Moreover, the professionals leading the Open Gym were appreciated.

3.2.3 Aims

One of the over-arching aim of all the activities during lunchtime was to offer the children meaningful engagement during lunchtime with informal learning situations and to serve their individual basic needs by giving them the opportunity to choose the activity they wanted to take part in during lunchtime. Regarding the organization of the activities in the school, the Open Gym helped to disperse the children within the school and offer physical activities next to the playground, which could be visited during periods of inclement weather. One of the central aims of the Open Gym was to increase the duration and quality of children’s physical activity. Within the Open Gym, different activities with different materials were made available to introduce new play formats, and the opportunity to try different activities and types of movement. The children also liked the Open Gym and had fun during their physical activities.

3.2.4 Perceived impact

The perceived impact was assessed by feedback from extended educational services staff and pupils. For some children the Open Gym was very beneficial, but some younger children were overwhelmed due to the variety and the open nature of the programe.

The Open Gym was visited frequently and especially during adverse weather conditions when it was an attractive alternative to the playground. At the beginning of the project, the Open Gym was mainly used for football, which was particularly popular with the boys: “The Open Gym, just setting up goals and a ball, only attracted the boys” (Extended Educational staff, OG_S7_Pos. 32). “We mainly have boys who just want footall, football, football, and more footall (…). If something other than football was offered, like a scooter park or a skate park, they weren’t interested.” (Extendend Educational Staff, OG_S6_Pos. 83). The school team began to direct the use of the hall by organizing specific physical activities, such as a movement landscape or separating the Open Gym to offer child-driven and teacher-led activities. As a result, more girls began to participate and sports activities other than football were conducted in the Open Gym.

The emergence of conflicts between children, but also between children and staff, was frequently mentioned. However, it was also explained that this type of collaboration could positively influence relationships between the children as well as with the staff members. Some children were agitated after the Open Gym, but the lessons afterward generally proceeded positively.

3.2.5 Quantitative results

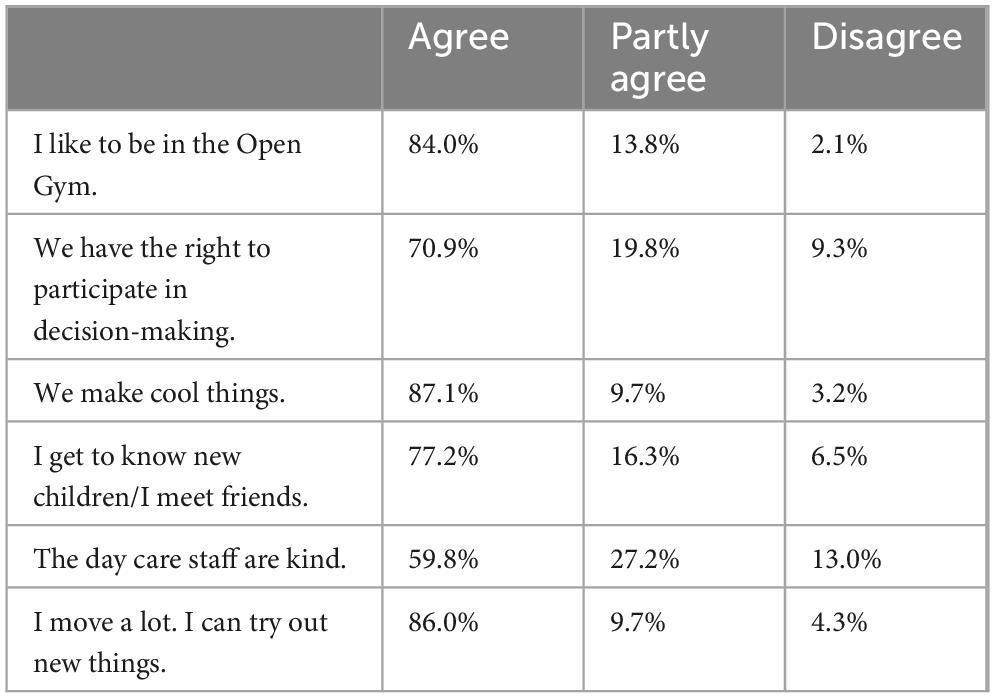

First and second grade children (n = 101) who participated in the Open Gym during lunch time took part in the standardized questionnaire. The children could answer six questions by using a child-centred approach. The questions as well as the distribution of the answers are displayed in Table 7.

Table 7. Questions about the Open Gym for the first and second grade children (n = 101) and the distribution of the answers.

The children in the first and second grades were satisfied with the Open Gym. The children enjoyed being in the Open Gym, doing “cool things” and moving around a lot, which allowed them to try new things. Seventy percent of the children said they were involved in decision-making and 77% of the children got to know new children or met (new) friends. Most of the children agreed that the staff in the Open Gym were kind, whereas one fourth partly agreed and 13% of the children disagreed.

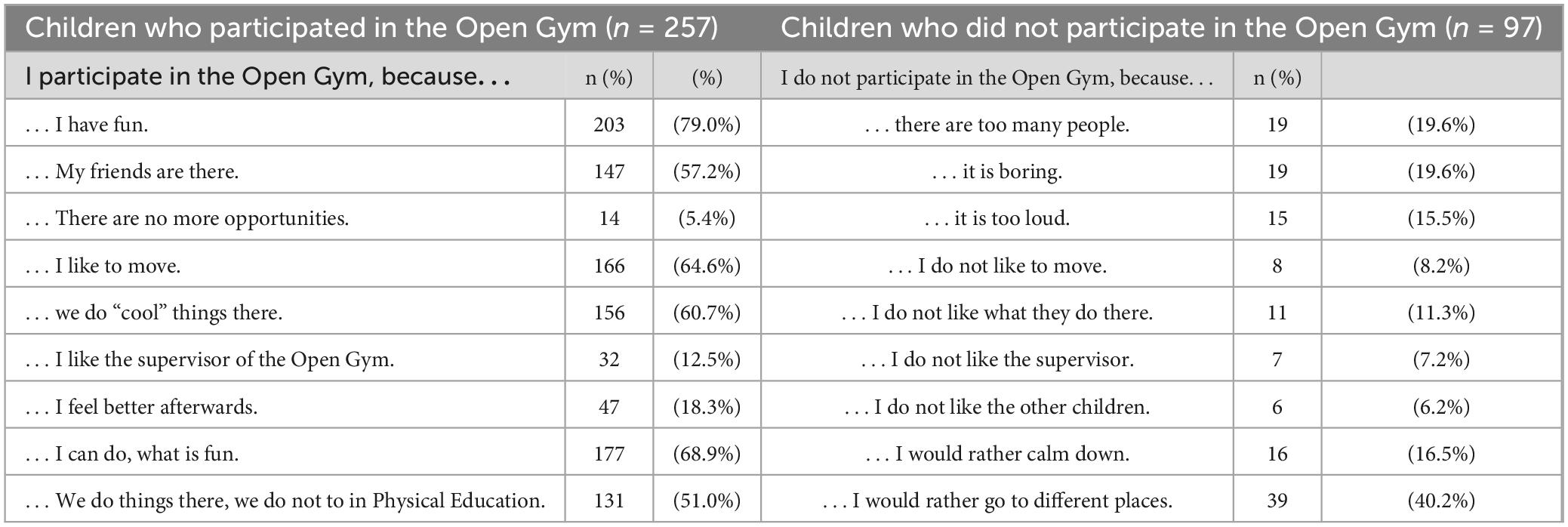

Children from third to sixth grade (n = 350) filled out an online questionnaire during 20 min of a regular lesson. Two hundred and fifty-seven children (73.4%) participated in the Open Gym, of which 13.6% went to the Open Gym “always,” 44.7% frequently’ and 41.6% “seldom.” Building on this, these children were then asked for the reason why they participated in the Open Gym (Table 8). The reasons were scaled dichotomously. The distribution of reasons as to why they participated in the Open Gym can be found in Table 8. Children went to the Open Gym because they had fun (79.0%), they liked to move (64.6%), they did “cool” things there (60.7%) and their friends were there (57.2%). Only 5.4% of the children said they would attend the Open Gym because there were no other available options.

Table 8. Reasons why third to sixth grade children participated in the Open Gym and why they do not (in total n and %).

Children who did not attend the Open Gym (n = 97) were asked for the reasons. Children preferring to go to other activities was the most commonly given reason (40.2%).

4 Discussion

The aim of this article was to analyze physical activity during the school day, at lunchtime and before, between and after lessons. The focus was on the role and importance of such activities for school principals and the extended educational services principals, as well as children’s patterns of use and motivations for participation.

The results of both studies highlight that school principals and the extended educational services principals regard the various sports activities in all-day schools, particularly the Open Gym, as central components of school-based extended educational programe (Bae, 2018).

“We need these activities. We cannot be without them anymore.” (Principal S7_ t3_Pos 5)

The sports activities offered were selected and utilized by students in different ways. This underscores the necessity for all-day schools to develop and implement diverse movement-based activities (Bailey et al., 2023; Webster, 2023), to ensure they are autonomously chosen and utilized by the children attending these schools (see Figure 1). This diversity of activities is what enables physical activities to play a leading role in extended educational activities: children choose what and with whom they are actively engaged. They perceive this engagement as part of their leisure where they can steer activity, involvement and partners.

Nevertheless, there is a need for guided activities with fixed schedules, as well as supervised options such as the Open Gym during lunch breaks offering various opportunities, and low-threshold sports activities, such as mobile facilities or equipment kits, which can be used autonomously throughout the day or outside school hours (Neuber, 2020; Naul and Neuber, 2021). The combination of these offerings is crucial and should be tailored to the specific characteristics of the schools, the needs of the students, and the local community.

“We must make sure that we offer activities that differ from the teaching but also from those activities provided by the community and the neighborhood, that these are attractive

activities, easily accessible to the children because they enjoy engaging in the activity but that also mean that they can chat with their friends and peers.” School Principal S3_t3_Pos74

Sustainable engagement with these activities is achieved through the flexible and daily selection and participation of children, fostering an inclusive environment where belonging is as important as performance (Webster, 2023). Year-round courses revealed a preference for multi-sport programes among younger children (preschool to third grade), while sport-specific courses gained popularity in higher grades, especially when children attended extended educational services on a daily basis. It was noted however, that children’s engagement in year-round courses declined with age, indicating a reluctance to commit to year-long programs. From fifth grade onward, open courses or those with quarterly adjustments in content became particularly popular. Although non-compulsory courses were requested, the courses could not always be implemented in this way, especially if the content were to be expanded. It also made it more difficult to plan with certainty.

The Open Gym was generally well received by children, who described it as a space for fun, physical activity, and social interaction with peers. Voluntary and spontaneous participation was crucial for them. One criticism was the limited opportunities for them to influence the choice of activities, with older children expressing a desire for more varied and age-appropriate content. The results of the children’s questionnaires and interviews highlight the need for a wide range of activities within extended educational offerings, not limited to sports. Some children in the two studies preferred quieter or alternative activities. Children require a variety of options, including not only movement-based activities but also cultural and aesthetic educational offerings that allow for relaxation and calmness, as well as opportunities to withdraw from social interactions with peers.

“To really grow together as a school with a diverse staff, we must have reliable structures and professionals we all can rely on, for the children’ and the parents’ sake. That children have the security to move around freely, that they feel safe, they know the professionals, they feel cared for by them. So the professionals must also trust and rely on each other 100%.” School Principal, S8_t3_Pos 75

To successfully implement extended educational activities, certain prerequisites must be in place to effectively offer a diverse range of programes. Collaboration between stakeholders is essential, requiring clear communication. Responsibilities need to be well-defined, as there were uncertainties regarding issues such as child supervision when activities were cancelled. Physical proximity between school staff was necessary for quick and informal communication. Additionally, children were more likely to participate in activities when they were held at or near the site of the school. In the case of year-round courses, the selection of activity should take into account the programes available in the immediate neighborhood of the school. Furthermore, course content and structure should vary depending on the grade level.

The high level of participation in movement-based activities underscores their significance and their “leading role” within the extended educational offerings. This confirms the results of a participatory survey on desired extracurricular activities (Tietze et al., 2005), in which children ranked sports and movement as their top priority across all primary school grades, and these activities were subsequently used extensively (Ferrari et al., 2023).

4.1 Limitations

The School Development Study and the in-depth Open Gym Study, while shedding light on the importance of physical extended educational activities, present several limitations which must be acknowledged.

4.2 Participants’ bias

One key limitation is the potential bias in the responses from participating principals, as they come from innovative schools that already have experience of seeking and securing additional funding and resources. Moreover, the schools joined the project voluntarily, which suggests that they are interested in having sport activities in day-schools and have also shown a willingness to implement it. This selection bias could lead to an overly optimistic view of their schools’ achievements and the capabilities of their staff. Another limitation lies in the powerful role of principals and extended education principal as key decision-makers in school development, whose perspectives could be influenced by personal interests and which might be contested by other school staff in the long term.

Furthermore, the studies were limited by their 3-year timeframe, which may not capture the long-term effects of extended educational services, particularly for students who engage in such programmes for over 6 years.

4.3 Methodological limitations

Self-report data present several critical limitations that must be acknowledged: participants might overestimate their achievements or the effectiveness of their programes due to social desirability or a vested interest in portraying their work positively. Additionally, children may have difficulty remembering past events or experiences accurately, leading to inaccuracies in the data. Additionally, they may interpret survey questions or interview prompts in different ways, leading to inconsistent or incomparable responses. Complementary methods such as observational data or triangulation with other informants could not be deployed due to time constraints.

Additionally, the studies focused exclusively on physical activities, omitting other extracurricular courses such as cultural or musical activities, which may have shown comparable relevance (Tietze et al., 2005). Consequently, direct comparisons between different types of extended educational activities were not possible. While this study focused primarily on physical activities, future research should include comparative analyses of different types of extended education programs, such as cultural, artistic, or academic offerings. Such studies could help identify intersections and ways of complementary working across various extracurricular areas.

4.4 Limitation of the sample

The participating schools have already benefited from financial and material support provided by the sports department of the city of Zurich, such as specific training for the extended education services staff and equipment for school playgrounds. The free year-round courses offered in schools are accessible to all schools and students across Switzerland, as they are funded by the Association for Youth and Sport (Jugend und Sport, 2025). However, additional investments in materials and programe design are required to offer extended educational activities, such as mobile playground facilities, like Pop-Up-Systems or sport-specific training for the staff.

The studies highlighted that physical extended education activities play a central role in all-day schools, but they do not operate autonomously or automatically. Effective management and professional delivery are essential to facilitate effective communication between the different stakeholders and the coordination of the different activities. This was especially evident in the in-depth Open Gym Study, where the management of the activities significantly influenced the project’s success and girls’ attendance rates in the Open Gym, and where activities were thematically planned, and movement landscapes which facilitated floorball were offered.

5 Conclusion

The findings of this study underscore that physical activities within the context of all-day schools assume a leading role in extended education. The high participation rates in programes such as the Open Gym or mobile facilities demonstrate that physical activity is not merely supplementary to instruction, but possesses its own pedagogical quality and developmental value. Schools also have the potential to contribute to the reduction of social inequalities in access to sports and exercise. The evaluation shows that low-threshold, free and open-access exercise programes are particularly effective in reaching children regardless of gender, ability or socio-economic background. Physical activity serves a dual purpose: it not only promotes physical health but also supports emotional, social, and personal development. When physical activity programes are designed with the principles of Self-Determination Theory (Ryan and Deci, 2000) in mind, fostering autonomy, competence, and relatedness, children are more likely to experience a sense of ownership and motivation. They can decide how, with whom, and in what form they want to be active. These findings highlight the educational value of physical activity and its role in providing a learning environment conducive to social and personal development.

Schools should regard physical activity as an integral component of educational development, not merely as an occasional add-on. The high level of student engagement demonstrates that physical activity is both meaningful and relevant to their daily school experience. To embed it consistently and flexibly into the school day in a student-centered way, school leadership must provide the necessary resources, such as space, time, and qualified staff to support its effective implementation. The successful implementation of physical activity programes depends on well-trained staff, clear communication, and strong collaboration among all stakeholders, including school leadership, teaching staff, and extended education professionals. To ensure and enhance programe quality, schools must provide appropriate structural conditions and offer targeted continuing professional development. Educators should be equipped not only to promote physical activity, but also to understand and support its broader developmental potential (Neuber and Kehne, 2024).

This study contributes to addresses a significant research gap and provides empirically grounded insights into perceptions, usage, and impacts—based on the perspectives of school leaders, educational staff, and pupils. The findings offer a strong empirical foundation for the further development of concepts such as “Active Schools” (Schulgruppe BASPO, 2010; Swiss Olympic et al., 2018) or the CSPAP framework (Society of Health and Physical Educators, 2024) in European contexts.

The valuable insights provided by the present study point to the need for further research to broaden and deepen our understanding of physical activity within extended educational settings (Naylor et al., 2015). Future research should adopt a multidimensional approach that considers various perspectives and levels of impact. First, longitudinal impact studies are needed to investigate the sustained effects of physical activity programes across different stages of a child’s educational trajectory. Such research could provide valuable insights into long-term influences on motor development, social-emotional competencies, academic achievement, and health-related behaviors. Second, child-centered and participatory research methods should be employed to gain a deeper understanding of how children perceive, engage with, and co-construct physical activity opportunities. These approaches offer the potential to capture children’s voices in a more nuanced and context-sensitive way. Third, given the critical role of qualified staff in the success of physical activity programes, future studies should examine the effectiveness of continuing professional development initiatives.

Data availability statement

The datasets presented in this article are not readily available because of the lack of anonymity of the interview data. Requests to access the datasets should be directed to the corresponding author.

Author contributions

IF: Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. KB: Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. JK: Writing – review & editing. LN: Writing – review & editing. PS: Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declare that financial support was received for the research and/or publication of this article. This research was funded by the Federal Office of Sport (BASPO, Bundesamt für Sport). The APC was funded by the University of Teacher Education Zurich (PHZH).

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

Bae, S. H. (2018). Concepts, models, and research of extended education. IJREE 6, 153–164. doi: 10.3224/ijree.v6i2.06

Bailey, R. P., Payne, R., Raya Demidoff, A., Samsudin, N., and Scheuer, C. (2024). Active recess: School break time as a setting for physical activity promotion in European primary schools. Health Educ. J. 83, 531–543. doi: 10.1177/00178969241254187

Bailey, R., Ries, F., and Scheuer, C. (2023). Active schools in europe—a review of empirical findings. Sustainability 15:3806. doi: 10.3390/su15043806

Carson, R. L., Castelli, D. M., Beighle, A., and Erwin, H. (2014). School-based physical activity promotion: A conceptual framework for research and practice. Child Obes. 10, 100–106. doi: 10.1089/chi.2013.0134

Chalkley, A., and Landais, R. (2022). Promoting physical activity through schools: A toolkit. Geneva: World Health Organization [WHO].

Chaput, J.-P., Willumsen, J., Bull, F., Chou, R., Ekelund, U., Firth, J., et al. (2020). 2020 WHO guidelines on physical activity and sedentary behaviour for children and adolescents aged 5-17 years: Summary of the evidence. Int. J. Behav. Nutr. Phys. Act. 17:141. doi: 10.1186/s12966-020-01037-z

Chiapparini, E., Schuler Braunschweig, P., and Kappler, C. (2016). Pädagogische zuständigkeiten in tagesschulen. Diskurs 11, 355–361. doi: 10.3224/diskurs.v11i3.8

Chiapparini, E., Schuler Braunschweig, P., Mathis, S., and Kappler, C. (2018). Kindeswohl und kinderwille. Vpod Bildungspolitik 206, 23–24. doi: 10.21256/zhaw-3598

Demetriou, Y., Gillison, F., and McKenzie, T. L. (2017). After-School physical activity interventions on child and adolescent physical activity and health: A review of reviews. APE 07, 191–215. doi: 10.4236/ape.2017.72017

Ferrari, I., Bretz, K., and Schuler Braunschweig, P. (2023). “Bewegungs- und sportangebote in der tagesschule - partizipative auswahl,” in Tagesschulen im fokus: Akteur*innen - kontexte - perspektiven, eds P. Schuler Braunschweig and C. Kappler (Bern: Hep Verlag).

Ferrari, I., Kress, J., and Schuler Braunschweig, P. (2024). Sport in schulen mit tagesstrukturen – SINTA: Zwischenbericht. Zürich: Pädagogische Hochschule Zürich.

Ferrari, I., Schuler, P., Bretz, K., and Niederberger, L. (2022). Sport im Lebensraum Schule (SLS) - dokumentation der items und skalen der itemsbefragung 2021. Zürich: Pädagogische Hochschule Zürich.

Finger, J. D., Varnaccia, G., Borrmann, A., Lange, C., and Mensink, G. B. M. (2018). Körperliche aktivität von kindern und jugendlichen in deutschland – querschnittergebnisse aus KiGGSWelle 2 und trends. J. Health Monitor. 3, 24–31. doi: 10.17886/RKI-GBE-2018-006

Hulteen, R. M., Morgan, P. J., Barnett, L. M., Stodden, D. F., and Lubans, D. R. (2018). Development of foundational movement skills: A conceptual model for physical activity across the lifespan. Sports Med. 48, 1533–1540. doi: 10.1007/s40279-018-0892-6

Jugend und Sport (2025). Freiwillige schulsportkurse. Available online at: https://www.google.com/search?q=%EF%83%A8+Jugend+und+Sport%2C+freiwillige+Schulsportkurse&rlz=1C1GCEU_deCH1046CH1046&oq=%EF%83%A8%09Jugend+und+Sport%2C+freiwillige+Schulsportkurse&gs_lcrp=EgZjaHJvbWUyBggAEEUYOTIHCAEQIRigAdIBCTExODZqMGoxNagCCLACAQ&sourceid=chrome&ie=UTF-8 (accessed January 20, 2025).

Lamprecht, M., Bürgi, R., Gebert, A., and Stamm, H. (2021). Sport schweiz 2020: Kinder- und jugendbericht. Magglingen: Bundesamt für Sport BASPO.

Mayring, P., and Fenzl, T. (2019). “Qualitative inhaltsanalyse,” in Handbuch methoden der empirischen sozialforschung, eds N. Baur and J. Blasius (Wiesbaden: Springer VS).

Naul, R., and Neuber, N. (2021). “Sport im ganztag – zwischenbilanz und perspektiven,” in Kinder- und jugendsportforschung in deutschland: Bilanz und perspektive, ed. N. Neuber (Wiesbaden: Springer VS), 133–150.

Naylor, P.-J., Nettlefold, L., Race, D., Hoy, C., Ashe, M. C., Wharf Higgins, J., et al. (2015). Implementation of school based physical activity interventions: A systematic review. Prevent. Med. 72, 95–115. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2014.12.034

Neuber, N. (2008). Zwischen betreuung und bildung – bewegung, spiel und sport in der offenen ganztagsschule. Sportunterricht 57, 180–185.

Neuber, N. (2020). “Bewegung, spiel und sport in der schulentwicklung,” in Fachdidaktische konzepte sport, ed. N. Neuber (Wiesbaden: Springer Fachmedien Wiesbaden), 137–158.

Neuber, N., and Kehne, M. (2024). Freude an Bewegung und Sport früh verankern – Perspektiven für die entwicklung des kinder- und jugendsports. Forum Kind Jugend Sport 5, 156–164. doi: 10.1007/s43594-024-00138-y

Noetzel, I., Becker, L., Gräfin v. Plettenberg, E., and Kehne, M. (2024). Forschungsstand zu bewegung, spiel und sport im schulischen ganztag in deutschland: Ein scoping review. Forum Kind Jugend Sport 5, 70–83. doi: 10.1007/s43594-024-00123-5

Paap, H., Koka, A., Meerits, P.-R., and Tilga, H. (2025). The effects of a web-based need-supportive intervention for physical education teachers on students’ physical activity and related outcomes: A randomized controlled trial. Children (Basel) 12:56. doi: 10.3390/children12010056

Pate, R. R., Davis, M. G., Robinson, T. N., Stone, E. J., McKenzie, T. L., and Young, J. C. (2006). Promoting physical activity in children and youth: A leadership role for schools: A scientific statement from the american heart association council on nutrition, physical activity, and metabolism (physical activity committee) in collaboration with the councils on cardiovascular disease in the young and cardiovascular nursing. Circulation 114, 1214–1224. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.106.177052

Reimers, A. K., Schoeppe, S., Demetriou, Y., and Knapp, G. (2018). Physical activity and outdoor play of children in public playgrounds-do gender and social environment matter? IJERPH 15:1356. doi: 10.3390/ijerph15071356

Riiser, K., Haugen, A. L. H., Lund, S., and Løndal, K. (2019). Physical activity in young schoolchildren in after school programs. J. Sch. Health 89, 752–758. doi: 10.1111/josh.12815

Ryan, R. M., and Deci, E. L. (2000). Self-determination theory and the facilitation of intrinsic motivation, social development, and well-being. Am. Psychol. 55, 68–78. doi: 10.1037/0003-066X.55.1.68

Sallis, J. F., McKenzie, T. L., Beets, M. W., Beighle, A., Erwin, H., and Lee, S. (2012). Physical education’s role in public health: Steps forward and backward over 20 years and HOPE for the future. Res. Q. Exerc. Sport 83, 125–135. doi: 10.1080/02701367.2012.10599842

Schulgruppe BASPO (2010). Die bewegte schule: Erläuterungen zum schweizer modell. Switzerland: BASPO.

Society of Health and Physical Educators (2024). What is CSPAP?- comprehensive school physical activity program. Available online at: https://www.shapeamerica.org/MemberPortal/cspap/what.aspx (accessed December 13, 2024).

Stodden, D. F., Goodway, J. D., Langendorfer, S. J., Roberton, M. A., Rudisill, M. E., Garcia, C., et al. (2008). A developmental perspective on the role of motor skill competence in physical activity: An emergent relationship. Quest 60, 290–306. doi: 10.1080/00336297.2008.10483582

Swiss Olympic, BASPO, and Fust, P. (2018). Schule bewegt. Avaible online at https://www.schulebewegt.ch/ (accessed November 20, 2024).

Tietze, W., Rossbach, H.-G., Stendel, M., and Wellner, B. (2005). Hort- und ganztagsangebote-Skala (HUGS): Feststellung und unterstützung pädagogischer qualität in horten und außerunterrichtlichen angeboten. deutsche fassung der school age care environment rating scale von Thelma Harms, Ellen Vineberg Jacobs, Donna Romano. Weinheim: Beltz Juventa.

Verbi Software GmbH (1989-2024). MAXQDA, software für qualitative datenanalyse. Berlin: VERBI Software GmbH.

Webster, C. A. (2023). The comprehensive school physical activity program: An invited review. Am. J. Lifestyle Med. 17, 762–774. doi: 10.1177/15598276221093543

World Health Organization (2010). Global recommendations on physical activity for health. Geneva: World Health Organization.

Keywords: physical activities, extended education, all-day school, movement promotion, comprehensive school program

Citation: Ferrari I, Bretz K, Kress J, Niederberger L, Schuler Braunschweig P (2025) Sports activities in extended education—their leading role for educational development. Front. Educ. 10:1536664. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2025.1536664

Received: 29 November 2024; Accepted: 21 April 2025;

Published: 30 May 2025.

Edited by:

Graça S. Carvalho, University of Minho, PortugalReviewed by:

Henri Tilga, University of Tartu, EstoniaYin Li, Tianjin University, China

Romana Klášterecká, Palacký University Olomouc, Czechia

Copyright © 2025 Ferrari, Bretz, Kress, Niederberger, Schuler Braunschweig. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Ilaria Ferrari, aWxhcmlhLmZlcnJhcmlAcGh6aC5jaA==

Ilaria Ferrari

Ilaria Ferrari Kathrin Bretz

Kathrin Bretz Johanna Kress

Johanna Kress Lukas Niederberger

Lukas Niederberger Patricia Schuler Braunschweig

Patricia Schuler Braunschweig