- 1Nepal Open University, Lalitpur, Nepal

- 2Kathmandu University School of Education, Lalitpur, Nepal

- 3Department of English, United International University, Dhaka, Bangladesh

- 4Department of English and Modern Languages, International University of Business Agriculture and Technology, Dhaka, Bangladesh

- 5Tribhuvan University, Mahendra Ratna Campus, Tahachal, Kathmandu, Nepal

This study investigates the status and effectiveness of guidance and counseling (G&C) practices in Nepali schools, focusing on three domains: learning strategies (LS), self-management (SM), and social skills (SS). Through a quantitative survey of 384 teachers, counselors, and headteachers across seven provinces of Nepal, we assessed G&C practices using a validated 30-item questionnaire adapted from the American School Counselor Association (ASCA) 2021 standards. We evaluated four school performance indicators—school environment, student behavior (e.g., social/emotional conduct), academic achievement, and post-school success—using teacher-reported 3-point scales (i.e., Good, Normal, and Needs Improvement). Using binary logistic regression, we tested four hypotheses. We found that SS were a strong predictor of better student behavior [odds ratio (OR) = 2.371, p < 0.05], as evidenced by fewer conflicts and better ethical behavior. Infrastructure (dedicated counseling rooms: OR = 2.838) and trained counselors (OR = 2.929) strongly enhanced school environments. LS and SM interventions did not have a significant impact on academic outcomes (e.g., test scores, dropout rates). Critical gaps include inadequate training in LS/SM strategies (e.g., only 9.6% of schools had counselors; teachers struggled with goal-setting and coping skills guidance). The findings emphasize the importance of conducting teacher workshops focused on delivering Learning Support and Student Mentoring (LS/SM). Additionally, there is a need for institutional support to improve counseling infrastructure and to integrate structured G&C frameworks. This study offers practical suggestions, such as creating specific areas for counseling and setting up uniform training programs to improve G&C services in places with limited resources.

1 Introduction

Guidance and counseling (G&C) are integral to the educational process, fostering students’ holistic development by addressing academic, career, and socio-emotional needs (ASCA, 2021; Yuen et al., 2007). In Tanzania, for example, Chilewa and Osaki (2022) found that insufficient resources, untrained personnel, limited government and parental support, and logistical constraints hindered these services, prompting recommendations for specialized counselor training and increased financial investments to improve outcomes. As G&C is an inseparable part of the wholistic educational process, it is important for children’s all-round harmonious development that provides remedial support, assists in solving problems, enhances academic achievement, develops social/emotional behaviors or selects career (ASCA, 2021; Diponegoro and Agungbudiprabowo, 2020; Kinra, 2008; Parveen and Akhtar, 2023; Shrivastava, 2003; Yuen et al., 2007). All schools are responsible for enhancing educational performance, which eventually concerns their students’ success and personality development. Besides normal teaching and learning activities, G&C has emerged as a key element in determining students’ overall academic, moral, and social development (Shaheen et al., 2023). Student G&C programs prevent issues like socio-emotional problems, dropouts, substance use, criminal offenses, or failure to keep jobs (Hrisyov and Kostadinov, 2022). Parents ‘counseling is the most influential aspect for young people. However, it might be delivered by their friends, teachers, school staff, or voluntary agencies (Ali and Graham, 2001). G&C provides a collaborative effort to ensure every child’s total personality development, encompassing self-reliance and self-development (Kinra, 2008). Otherwise, G&C “is likely to be not only ineffectual but harmful and misleading” (Shrivastava, 2003).

Considering the impact of G&C, some developed countries, such as the United States, Hong Kong, and Botswana, have incorporated G&C into school programs to acquire academic, career, self-awareness, and interpersonal communication skills, thereby gaining and employing lifelong skills (Nyutu, 2006; Ziomek-Daigle, 2016). In South Asia, countries like India incorporated G&C in schools as early as the early 20th century, laying a strong foundation of research about human development and learning (Shrivastava, 2003). However, in Nepal, G&C is still fragmented and unsystematic, organizationally incoherent, and policy incoherent, having been included in the National Education System Plan (1971–1976) without institutional support or infrastructure, despite informal support (Shah, 2015). Indeed, challenges such as low academic achievement and psychosocial problems are faced by scores of children in Nepali schools (Poudel, 2017; Shah, 2015). However, in Nepal, despite the inclusion of G&C in the National Education System Plan (1971–1976), implementation remains fragmented and unsystematic, lacking policy coherence, institutional support, and dedicated infrastructure (Shah, 2015). There are some challenges, including academic underachievement and psychosocial problems, among many children in Nepali schools (Poudel, 2017; Shah, 2015). In some private schools of the capital city, school leaders, teachers, and counselors address G&C related to psychosocial issues, academic underachievement, or personal development (Shah, 2015). Some of this evidence is insufficient to inform about G&C practice in the schools of Nepal. This disparity emphasizes a critical gap between policy intent and practical execution, necessitating an exploration of contextual challenges and opportunities.

With all of the above, the education system of Nepal faces multifaceted issues, including high dropout rates, academic underachievement, and psychosocial problems among students (MOEST, 2022; Poudel, 2017). One marginalized community, the Dalit (untouchable caste), also faces heightened vulnerability, and their primary level enrollment is at only 20% (CEHRD, 2024). Some private schools in urban areas such as Kathmandu have already adopted G&C services to address behavioral and academic problems; however, these initiatives are not uniform (Shah, 2015). Furthermore, in the case of Nepal, G&C is mostly taught by teachers, which raises concerns about its effectiveness due to inadequate training and excessive work pressure due to a lack of specialist counseling (Kandel, 2020). Because there are no dedicated spaces, using the classroom or administrative office for counseling compromises privacy and effectiveness (Lunenburg, 2010). Three key domains of G&C are identified in the literature: academic, career, and socio-emotional guidance (ASCA, 2021; Kinra, 2008).

However, in Nepal, research reports that connect anecdotal evidence to practice are limited, and studies on the effectiveness of these elements are scarce. Although social skills (SS) development is often emphasized, the even greater impact of G&C on learning strategies (LS) (e.g., goal setting, critical thinking) and self-management (SM) (e.g., goal engagement and focus) has been well-documented in the context of learning self-regulation. However, documenting these G&C outcomes (coping styles, adaptability) is under-investigated (Shaheen et al., 2023). Further systemic obstructions in terms of cultural sensitization, resource paucity, and inadequate training also restrict the implementation of G&C frameworks, which in turn perpetuate cyclical issues in student outcomes (Bhatta and Mehendale, 2021). Against this background, the present study fills the lacuna with a quantitative study involving 384 teachers, counselors, and headteachers from seven different provinces in Nepal.

We focus on three G&C domains:

• Learning strategies (LS)

• Self-management (SM)

• Social skills (SS)

And examine their impact on four school performance indicators:

• School environment (e.g., safety, inclusivity)

• Student behavior (e.g., social–emotional conduct)

• Academic performance (e.g., achievement scores)

• Post-school success (e.g., further education/employment)

Three research questions guide the research:

• What is the current status of G&C practices (LS, SM, SS) in Nepali schools?

• How effective are these G&C practices in improving school performance indicators?

• What infrastructural (e.g., counseling spaces) and personnel (e.g., trained counselors) factors influence G&C effectiveness?

Based on the literature review, objective, and research question, the following hypotheses were tested:

H1: Distributions of LS practices do not differ by educator gender/school type.

H2: Distributions of SM practices do not differ by educator gender/school type.

H3: Distributions of SS practices do not differ by educator gender/school type.

H4: G&C practices positively affect overall school performance.

This study aims to influence policy reform, campaign for specific teacher training, and raise awareness of the requirement of counseling infrastructure by embedding international G&C frameworks in the local socio-educational context of Nepal. The implications are far-reaching for actors working to enhance educational practices in response to the international scenario, while also considering the challenges that are particular to the context in Nepal and beyond.

2 Guidance and counseling: the context of Nepal

Nepali schoolteachers, counselors, and headteachers spend around six hours with children in their schools every school day. Therefore, the G&C provided by teachers, counselors, and headteachers can improve students’ problem-solving skills (Diponegoro and Agungbudiprabowo, 2020) to enhance academic performance, develop social/emotional behaviors, or select a career. In Nepali schools, student concerns are increasingly dominated by academic performance pressures and social–emotional and career-related issues rather than purely disciplinary or resource-based challenges (Karki et al., 2024; Li et al., 2023). For example, in student performance data from the Flash Report 2021, MOEST reports a gross enrollment rate in Early Childhood Education is 87.6%. In 2020–21, the girl enrollment rate was 49.7% at the lower basic level, whereas it was 50.0% at the secondary level. It is more vulnerable in Dalit communities (so-called untouchable caste) in 2020/21, where the enrollment of total Dalit students at the lower basic level is 20.0%. Similarly, the Education Review Office’s 2015 NASA report shows that the average learning achievements in grade 5 were 48.0, 46.0, and 47.0% in Mathematics, Nepali, and English, respectively. In contrast, in grade 5, they are 35.0, 48.0, and 41.0% in Mathematics, Nepali, and Science subjects, respectively. This evidence suggests that schools are underperforming. In addition to academic challenges, Shah (2015) identified a wide range of behavioral and psychological issues among students, including class disruptions, peer conflicts, hyperactivity, learning difficulties, disciplinary problems, bullying, career-related concerns, conversion disorders, multicultural and parenting issues, dropout rates, poor peer relationships, academic underachievement, truancy, classroom mismanagement, substance abuse, school violence, interpersonal difficulties, challenges faced by gifted students, gender-based violence, disabilities, and more (Kandel, 2020; Poudel, 2017). Further, Shah (2015) suggests providing training to schoolteachers in G&C, which is to be initiated or led by the Ministry of Education or its organization in a systematic and organized order, as counseling services influence students’ academic, social, emotional, personal behavior, and further study and career success as well (Amat, 2019).

In recent years, several initiatives have been undertaken by the government and non-government agencies. For example, the Centre for Education Human Resource Development (CEHRD) has been promoting life-skill learning through some school-level courses (Kandel, 2020). At the university and college levels, G&C courses, such as Foundation of Education, Curriculum, and Educational Psychology, are included as part of the curriculum (Shah, 2015). Generally, individual and group counseling sessions are conducted for students planning to pursue board exams or study abroad, typically after completing school-level examinations or at the end of each academic level in higher education. Private educational counseling centers and colleges have taken the lead in offering these services, often driven by commercial or business-oriented motives. However, Kathmandu University School of Education offers academic programs in G&C, including a Master of Education (M. Ed.) in School Counseling (launched in 2023 as a one-year program and expanded to 2 years in 2024) and an MPhil/PhD in School Counseling and Psychological Wellbeing focusing on transformative practices, critical praxis, and evidence-based strategies to address mental health, holistic development, and social justice in educational settings, with emphasis on interdisciplinary research and leadership in policy or institutional roles. Likewise, the Nepal Open University offers a master’s program in Pedagogical Sciences, which includes a 3-credit course on Guidance and Counseling (G&C). This program is conducted in collaboration with a project involving another university in Nepal, as well as Hamk and Jamk Universities of Applied Sciences in Finland. As part of the same initiative, a short training module is being developed and implemented through a Massive Open Online Course (MOOC), which could represent a pioneering step toward establishing school-based G&C in Nepal (Kandel, 2020).

3 Guidance and counseling: theory and practice

Guidance and counseling are analyzed from different perspectives in terms of content and context, although the intent of G&C is almost similar in that it concentrates on students’ overall development. For example, the ASCA (2021) states that school counselors are expected to provide G&C in different ways, such as culturally sustaining instruction, appraisal and advice, assisting the students in demonstrating LS, SM, and SS. In the school context, school counselors’ responsibilities are divided into three domains of GC: academic, career, and social/emotional, ensuring comprehensive accountability and cohesion of the program components (Ziomek-Daigle, 2016). In line with Ziomek-Daigle (2016), a modern trend in the guidance movement, many scholars, such as Kinra (2008) and Shrivastava (2003), have emphasized the importance of G&C in the forms of vocational, educational, and personal guidance. In vocational guidance, a guidance counselor provides services to the clients (students in the school context) to prepare them for job selection and job preparation, whereas in educational guidance, students get advice/service that encourages them to increase their results in schools across different curriculum offerings, or G&C makes adjustments with the school, curricula, and school life. In personal guidance, counselors address students’ concerns, including maladjustment issues, child and adult welfare, and aspects of mental hygiene. Mental hygiene is the science and practice of maintaining and improving mental health, an approach to mental well-being that focuses on developing and using life skills to optimize emotional and intellectual competence, prevent mental health problems, and enhance psychological resiliency. In the context of primary schools in Hong Kong, the comprehensive G&C programs and G&C activities were categorized into four groups: guidance curriculum, individual planning, responsive services, and system support (Yuen et al., 2007). In the activities, guidance counselors concentrate on students’ whole-person development through different activities like extracurricular activities, experiential learning, assisting students in working out their study and career plans, keeping achievement records, counseling students with their problems, teacher development activities relating to G&C knowledge and skills, and many more activities (Yuen et al., 2007).

In the G&C process, Kinra (2008) states that counseling is paramount in guidance, where a counselor collects detailed information about the counselee and uses different techniques, such as psychological tests or non-standard tests, for diagnostic purposes before making decisions. Education is intended to be the means to direct and guide students at the individual level through instruction or a conscious effect of society, enabling them to sustain their lives (Shrivastava, 2003). In the twenty-first century, due to insecurity, instability, and continuous change. In a professional context, Di Fabio and Bernaud (2018) stated a narrative paradigm that focuses on post-modern G&C interventions. This narrative approach provides opportunities for the participants to construct a self-story for creating meaning in their personal and professional lives. Guidance counselors generally use advice-oriented, informative, and clinical approaches (Kandel, 2020). In the training manual of G&C in Nepali Schools, three major approaches (socio-cultural, problem-solving, and inquiry-based approaches) are discussed, and further, the school, parents, and community partnership is suggested for the G&C in the Schools, which is expected to bring desirable results (Khadka, 2024; Shrestha Rajbhandary, 2019; Parveen and Akhtar, 2023).

A brief review of the literature on school G&C indicates that three major domains are considered: academic/educational, career/vocational, and social/emotional/personal G&C. As part of the chain of G&C skills, this study discusses advice, guidance, and counseling in the three aforementioned domains, rather than therapeutic counseling (Ali and Graham, 2001), which is also discussed.

4 Methods

4.1 Research design

This study employed a quantitative survey research design to investigate G&C practice and effectiveness in Nepali schools. The design aimed to generate generalizable findings (Cohen et al., 2018) by collecting data from schoolteachers, counselors, and headteachers across seven provinces of Nepal.

4.2 Participants

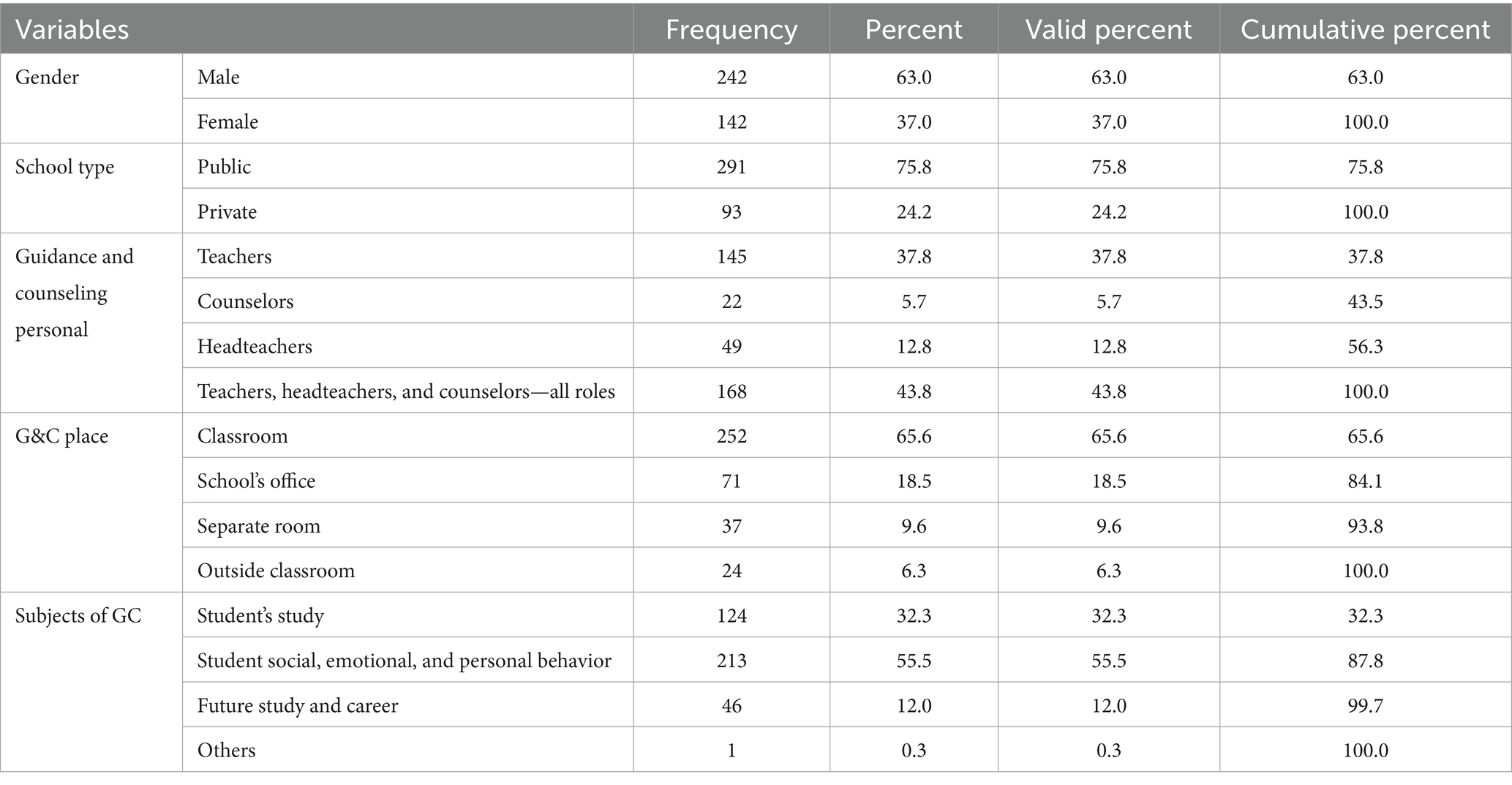

A sample of 384 teachers, counselors, and headteachers (63% male, 37% female) was drawn from 97 schools stratified across public (75.8%) and private (24.2%) institutions. The participants included teachers, headteachers, and counselors, with the majority (55.5%) reporting involvement in addressing students’ social, emotional, and behavioral issues. Data collection targeted 563 teachers, counselors, and headteachers from 138 schools, yielding 402 responses. After screening for incompleteness and outliers, 384 valid responses were retained for analysis.

4.3 Instrument

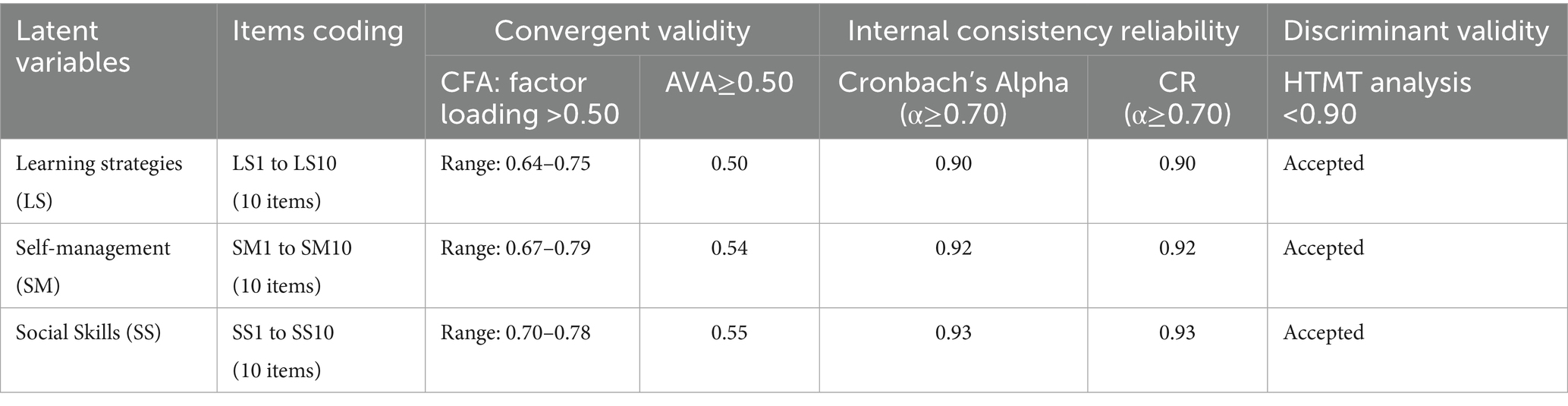

A structured Guidance and Counseling Survey Questionnaire (GCSQ) was adapted from the ASCA, 2021 and translated into Nepali using a translation-back-translation method. Permission was granted by ASCA to use it. This study was delimited to the Behavior Standards stated by ASCA (2021), and it was found to be systematic by design, with decision-making influenced by data (Ziomek-Daigle, 2016). The GCSQ includes learning strategies, self-management, and social skills, where the LS consist of 10 items, SM skills include 10 items, and SS include 10 items, and altogether 30 items that were validated using confirmatory factor analysis as presented in Table 1. First, the questionnaire was developed in English and translated into Nepali using the translation-back-translation method. Then, the researchers conducted a short round table discussion with four participants—a teacher, two counselors, and a headteacher to contextualize language issues, difficulty levels, and item relevancy. Each item used a 5-point Likert scale (1 = Strongly Disagree to 5 = Strongly Agree). For assessing the schools’ performance, four statements: school environment, student social, emotional, and personal behavior, students’ success after school education, and schools’ academic performance were asked of the teachers, counselors, and headteachers, who were on 3-point scales (good, normal, and to be improved) as dependent variables. Demographic variables (teacher gender, school type, G&C provider, and location of counseling) were also included. Furthermore, the gender of teachers, counselors, and headteachers, types of schools, guidance counselors in the schools, place of counseling, and subjects of counseling in the schools were additional questions. The details of the sample characteristics are presented in Table 2.

4.4 Reliability and validity of the items assessing G&C practice in Nepali schools

For the quality assurance of the reliability and validity of the variables, Confirmatory Factor Analysis (CFA) and Average Variance Extracted (AVA) were observed for the convergent validity, Cronbach’s Alpha and Composite Reliability (CR) for the internal consistency reliability, and Heterotrait-Monotrait (HTMT) for discriminant validity were employed (Masa’deh et al., 2022) as follows:

From Table 1, the CFA: factor loading on LS, SM and SS is above 0.50, and AVE is also above the cut-off value 0.50. Similarly, Cronbach’s Alpha and CR both are more than 0.70, and HTMT (Heterotrait-Monotrait) is in the interval of 0.84 to 0.90. These all results normally affirm the reliability and validity of the questionnaire (Cohen et al., 2018; Hair et al., 2014; Masa’deh et al., 2022).

4.5 Data collection

Data were collected between June 2024 and July 2024, using both online surveys (Google Forms), sent via email, and paper-based questionnaires distributed at different schools. We primarily recruited participants through university email lists and social media networks, such as Facebook, X, and LinkedIn. Two different methods of communication were used: one involved contacting participants through direct email invitations and survey links, while the other was face-to-face interactions conducted by researchers at designated sites. Researchers obtained informed consent and guaranteed participant anonymity prior to distribution. However, researchers administered paper-based questionnaires at their respective schools. We obtained ethical approval and anonymized institutional affiliations and identities. The questionnaire took approximately 10 min to complete for all participants, whether they used the online or paper version.

4.6 Data analysis

Demographic and G&C practice data were descriptively summarized (mean, standard deviation, frequency). Non-parametric tests (Mann–Whitney U) were used to compare responses across gender and school types. Likewise, frequency and percent are used to describe the sample characteristics and the status of schools’ performance. Mean, standard deviation, skewness, and kurtosis are employed to analyze the status of the components of G&C (LS, SM, and SS). The components of G&C (LS, SM, and SS) are also examined to determine whether they are significantly different across the genders of teachers, counselors, headteachers, and types of schools using the Mann–Whitney U test. The questionnaire’s reliability and validity were assessed using statistical methods, including Factor analysis, Cronbach’s Alpha, and others. Upon testing the assumptions, a binomial regression analysis is performed to investigate the impact of G&C on school performance. The effects of LS, SM, and SS on school performance indicators were examined with binary logistic regression with counseling location and provider as covariates. Model fit was assessed through Nagelkerke R2, the Hosmer-Lemeshow test, and multicollinearity, as indicated by tolerance (> 0.20) and VIF (< 5.0) statistics.

4.7 Ethical considerations

The study adhered to ethical standards, including informed consent, confidentiality, and anonymization of participant and school identities. Data were stored securely and were accessible only to the research team.

5 Results

5.1 Teachers’ demographic status and schools’ G&C-related information

In this section, the respondents’ gender and their school’s type, as well as the G&C person, place, and subject of G&C, are analyzed. In Table 2, male teachers have a dominant presence, which is 63%, nearly double the percentage of female teachers, which is slightly different from the male teachers’ percentage in the population (57.04%) (CEHRD, 2024). More than two-thirds of teachers from public schools (funded by the government) participated. The percentage of teachers working in public schools is 76.36% (CEHRD, 2024).

As the teachers, counselors, and headteachers responded, they guided and counseled their students, followed by headteachers or both teachers and headteachers in the schools. A small number of teachers (5.7%) agreed that counselors also guide and counsel them. Regarding the subjects of G&C, as revealed by Shah (2015), the majority of teachers (55.5%) agreed that they counsel or guide their children on issues of social, emotional, and personal behavior, followed by study counseling for students (32.3%). Only around 12% of the teachers report that they counsel for further study and career, which is also supported by the opinions of Sangroula (2024). The teachers mostly use the regular classrooms for GC. It means they guide their study, behavior, or career in the classroom and the office. Only a small number of teachers (9.6%) reported having separate rooms for G&C. The teachers’ responses suggest that Nepali schools lack a separate counseling room and other infrastructure, despite effective G&C generally requiring physical infrastructure, adequate space, the privacy of the person and subjects of counseling, accessibility to problems, and other essential elements (Lunenburg, 2010).

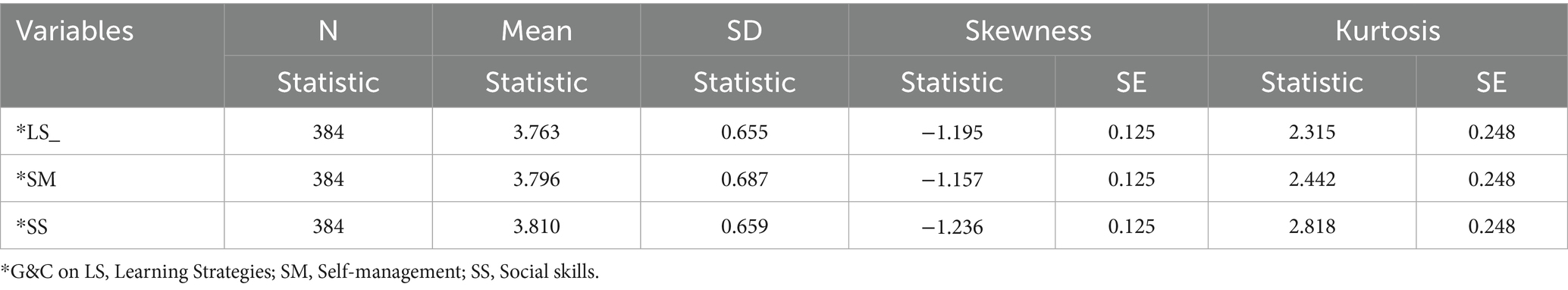

5.2 Status of school guidance counseling in the schools

The status of school guidance counseling is analyzed using means, standard deviation, skewness, and kurtosis to observe the nature of normality. In Table 3, the status of school guidance counseling is presented.

Out of five scales (strongly disagree to agree with codes from 1 to 5, respectively, strongly), teachers, counselors, and headteachers’ average rating is nearer to 4 (from 3.763 to 3.810), which represents “agree.” This means the teachers, counselors, and headteachers agree with the positive statements related to providing G&C on LS, SM, and SS. The standard deviation also indicates similar responses across the respondent teachers, counselors, and headteachers. Out of these areas of G&C, they provide G&C that focuses on SS, which aim to improve communication, listening, and SS to foster positive relationships, ethical decision-making, and social responsibility. It also fosters collaboration, leadership, advocacy, and cultural awareness, promoting social maturity and responsiveness in diverse groups. However, the responses (data) are not normally distributed as none of the values of Skewness and Kurtosis lie between −2 and +2, distorting the normality (Meinert, 2011). Responses of teachers, counselors, and headteachers were further analyzed based on their gender (male and female) and type of schools (public and private) using the Mann–Whitney U test. The result is presented in Table 4.

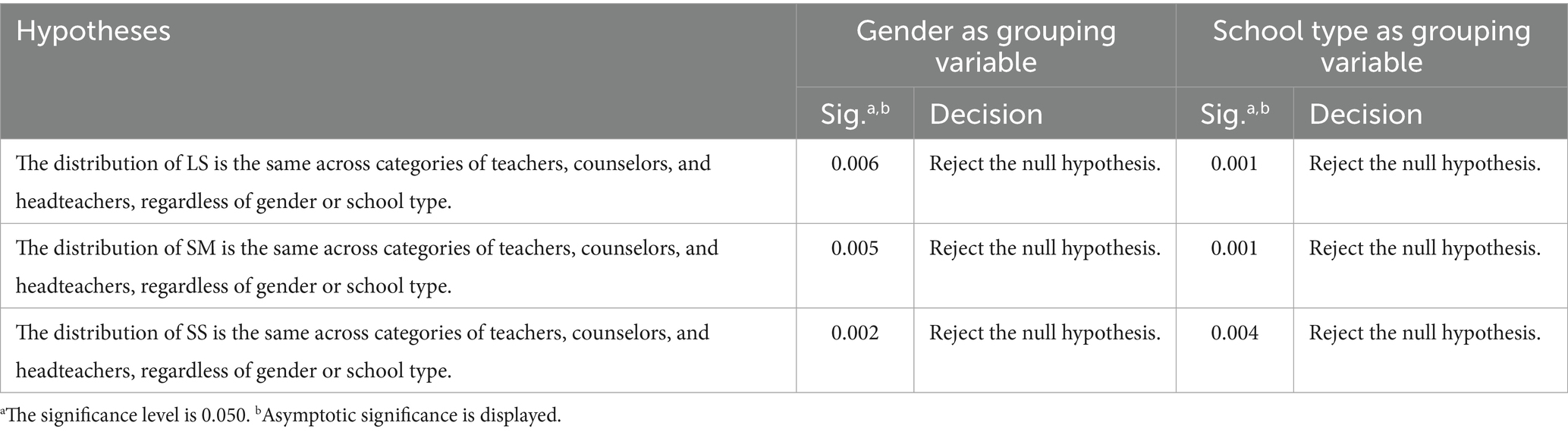

Table 4. Mann–Whitney U Test on the components of G&C across teachers, counselors, and headteachers’ gender or school types.

From Table 4, as perceived by the respondents, by gender (male and female) and types (public and private), LS, SM, and SS are significantly different at 1% level of significance (p-values: 0.006, 0.005, 0.002, 0.001, 0.001, 0.004 < 0.01). From the descriptive analysis using means, in all components (LS, SM, and SS), mean values for female teachers, counselors, and headteachers is higher that shows as perceived by the female teachers, counselors, and headteachers, the practice of G&C on each component is better. However, both types of teachers rated the statement above as “3” and closer to “4.” Similar to the findings of this study, in the context of secondary schools in Southwest Ethiopia, Arfasa’s (2018) study revealed that teachers from public schools perceived effective counseling, whereas females perceived it at a higher level. However, it contradicts that there was no significant difference between the perceptions of public and private school teachers, counselors, and headteachers in the Nepali context, and ‘so does it in the Kenyan context’ (Ngeno, 2022).

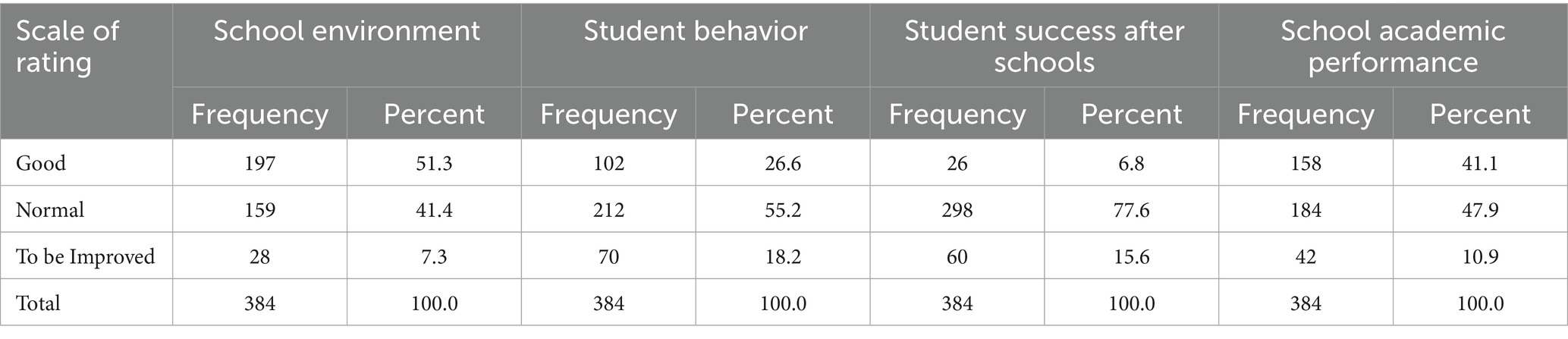

5.3 Schools’ overall performance

Regarding the schools’ overall performance in terms of environment, student behavior, academic performance, and student success after school, a 3-point Likert scale (“Good,” “Normal,” and “To be improved”) was administered among the teachers, counselors, and headteachers. The frequency on each scale is as follows in Table 5.

Table 5 shows that the school environment emerged as the strongest area, with over half of the respondents (51.3%) rating it as “Good,” while 41.4% considered it “Normal,” and only 7.3% felt it needed improvement. This implies a positive perception of the school’s physical and social aspects. On the other hand, the behavior of the students was considered average, with 55.2% rating as “Normal,” 26.6% as “Good,” and 18.2% indicating that it needed “Improvement.” The results suggest some acceptability and potential for behavioral change. Student success after school was identified as the most problematic aspect, receiving the lowest rating of “Good” at 6.8% and the highest rating of “Normal” at 77.6%, while 15.6% indicated that it does not work. This means they are least confident in the school’s ability to prepare students for life beyond education. In the school performance results, the ratings were cautiously good, with 41.1% rated “Good,” 47.9% “Normal,” and just 10.9% in the category “Needs improvement.” “Normal” was rated most frequently overall across everything from student behavior to what the student did after school. However, for the environment and academics, “Good” was the more typical rating. In conclusion, Stakeholders view the school climate most positively and are most concerned about student post-graduation success. Student behavior is generally average with some issues, and academic performance is considered reasonably good. These insights point to key areas—especially student behavior and post-school readiness—where targeted improvements could be beneficial. Despite remarkable progress in school education in Nepal, student learning outcomes tend to regress and stagnate, with some issues of equitable education or internal efficiency indicating poor quality of education (Comba et al., 2023; Bhatta and Mehendale, 2021).

5.4 Effect of school guidance counseling on schools’ overall performance

Binary logistic regression was employed to analyze the effect of G&C (LS, SM, and SS) on schools’ overall performance. For this, dependent variables, student behavior, student success after school, and school academic performance were recoded into a dichotomous scale where the scale “Normal” was merged to “to be improved” as there are some aspects of the normal situation that are supposed to improve for transforming into the status of “Good.” The scale “Good” was coded by “1” and the “To be improved” by “0.” The alternative hypothesis states, “The practice of G&C is more likely to be effective on the schools” overall performance, which has “Good: 1” status as compared to the status of “To be improved: 0.”

Two additional variables (place of G&C and the person providing G&C) were used as control variables. The “separate place for G&C” and “counselor” examined whether they affected the school performance with reference to other places like classrooms and offices, and other persons like teachers, counselors, and headteachers. From the analysis of data using SPSS, model fit and collinearity were examined before the analysis of the coefficient of binary logistic regression as follows:

The Omnibus Test on the effects of G&C components (LS, SM, and SS), including two control variables (place of G&C and G&C person) on four different components of schools’ overall performance shows the significant results whose p-values are less than 5% level of significant only for the school environment, student behavior, and schools’ academic performance. The models show a good fit only for the dependent variables: school environment (p = 0.042), student behavior (p = 0.000), and schools’ academic performance (p = 0.000).

In the Model Summary yielded from the SPSS computation, the values of Nagelkerke R Square are 8.6, 8.9, 4.0, and 4.5% for the GC: LS, SM, and SS that explain school environment, student behavior, school academic performance, and success after school education, respectively at low to very low level. Further, the Hosmer and Lemeshow test is also used to test model fit. The p-values for the school environment and student behavior are 0.940 and 0.425, indicating that the model adequately fits the analysis. The p-values for the remaining variables (school academic performance and student success after school) are less than 5%, indicating a poor fit of the model.

For testing multicollinearity among the independent variables (LS, SM, and SS), tolerance and VIF were used. The tolerance values are 0.292, 0.245, and 0.316, which are not less than 0.20. The VIF values are 3.429, 4.085, and 3.163, which are not more than 5 and do not show the issue of multicollinearity (Belsley, 1991) among three components of G&C (LS, SM, and SS) to explain the schools’ overall performance.

For the final analysis, based on the acceptance of assumptions for the fit of the models, two components of schools’ overall performance (school environment and student behavior) and the control variables (place and person of G&C) are used.

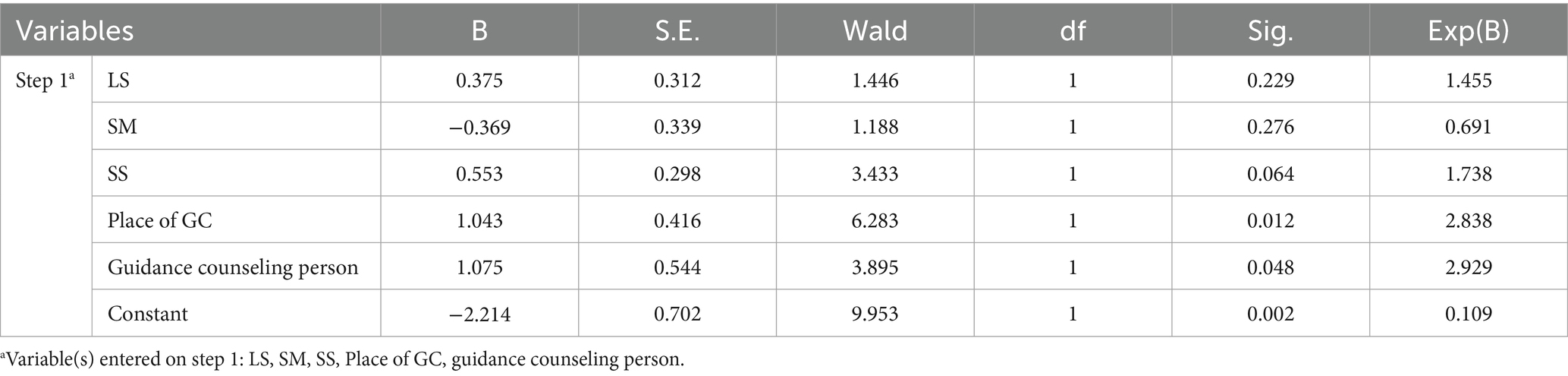

From Table 6, G&C on LS, SM, and SS are not significant in explaining the school environment (p = 0.229, 0.276, and 0.064) at the 5% level of significance; however, they are positive in explaining the school environment, except for G&C on SM skills. Wald’s criterion suggests that the place of G&C and G&C persons significantly affects the school environment. When G&C is conducted in a ‘Separate Room’ other than the office, classroom, or other places, the odds ratio (OR) is 2.838, indicating that the school environment is 2.838 times more likely to improve. Similarly, when G&C is conducted by a ‘Guidance Counselor’ other than teachers, headteachers, or others, the OR is 2.929, so the school environment is 2.929 times more likely to improve.

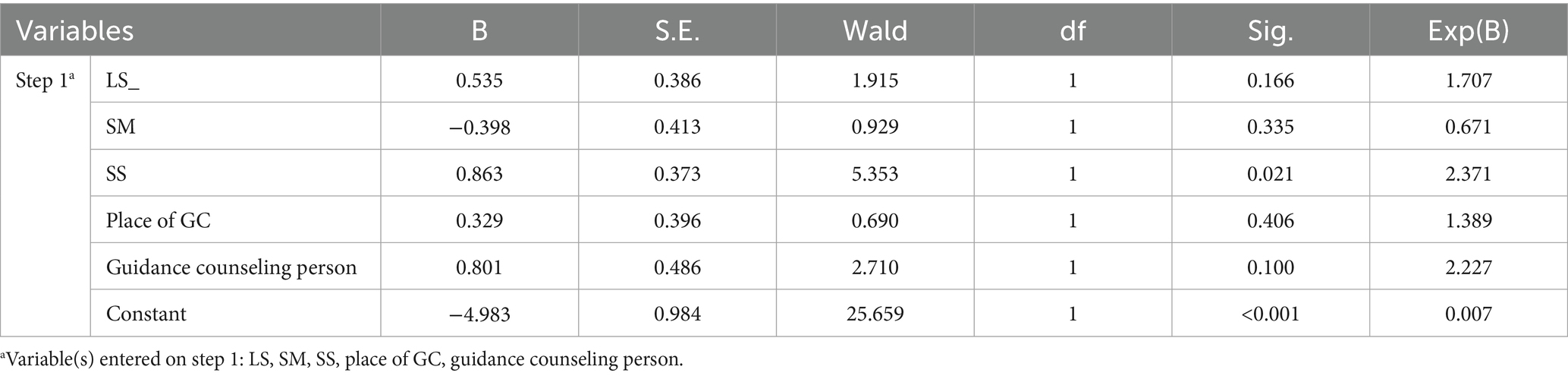

From Table 7, the Wald criterion indicates that G&C on SS significantly affects student behavior. When G&C on SS is increased by one unit, the OR is 2.371, indicating that student behavior is 2.371 times more likely to improve. G&C on LS, SM, places, or persons are not significant predictors of student behavior. However, apart from G&C on SM skills, other positive factors exist. One of the components of G&C (Social Skills) is positive and significant in explaining students’ social, emotional, and personal behavior. The places of G&C (separate room) were also significant in positively explaining the school environment. While analyzing the items of each component of G&C, the mean values of statements 7, 8, and 9 under LS, statements 5, 7, and 10 under SM, and statements 4, 5, and 9 under SS were comparatively lower. In providing G&C on LS, as perceived by the respondent teachers, the existing guidance counseling persons (teachers, counselors, and headteachers) are comparatively not able to deliver G&C on the following subjects:

LS7: Provides long- and short-term academic, career, and social/emotional goals.

LS8: Provides engagement in challenging coursework.

LS9: Facilitates informed decision-making by gathering evidence, getting others’ perspectives, and recognizing personal bias.

Similarly, they are not adequately able to deliver the G&C on SM skills that:

SM5: Enhances perseverance to achieve long- and short-term goals.

SM7: Develop effective coping skills.

SM10: Enhances ability to manage transitions and adapt to change.

In Social Skills, the least focused areas of G&C were identified as:

SS4: Helps students develop empathy.

SS5: Helps ethical decision-making and social responsibility.

SS9: Demonstrates social maturity and behaviors appropriate to the situation and environment.

The findings of this study are comparable to and contrasted with those of previous studies. A few studies, such as Shaheen et al. (2023) and Hrisyov and Kostadinov (2022), have found that G&C emerged as a positive predictor of academic, moral, and social development in the contexts of Islamabad and Bulgaria, respectively. This finding is partially consistent with the results of the current study. However, G&C on LS and SM was not a significant predictor in the Nepali school context. For the separate counseling place (room), the findings of the study are comparable to the study of Yuca et al. (2017), which found a correlation between infrastructure and G&C services. Butler (1987) also opines that a multi-purpose room can also be used for counseling. However, it is necessary to ensure students’ privacy and confidentiality when a counselor conducts an emotional interview with students, and the students may want to do it separately. In this study, only a small number of teachers reported that they had counselors in their schools who had a significant positive effect on the school environment as compared to others (teachers and headteachers). This may be due to the lack of systematic or formal training in guidance work in Nepali schools (Yuen et al., 2007).

6 Discussion

The results of this study reveal the complex efficacy of G&C practices in Nepali schools, revealing strengths and pressing needs. The main effects analysis of G&C interventions targeting SS significantly predicted improvements in students’ social, emotional, and behavioral outcomes. This finding is consistent with international research results, highlighting the significance of G&C for developing SS and ethical decision-making (ASCA, 2021; Yuen et al., 2007). Meanwhile, the absence of the main effects for LS and SM indicates contextual difficulties. These findings were in opposition to studies in Bulgaria and Pakistan in which extensive G&C programmes were positively associated with academic and self-regulation outcomes (Hrisyov and Kostadinov, 2022; Shaheen et al., 2023). The variation may be due to systemic issues within Nepal, such as a lack of teacher training in LS/SM strategies or G&C frameworks that properly target these areas. A dedicated counseling room and trained counselors were strong predictors of a positive school environment. This result aligns with previous studies that favor privacy and proper installations to improve counseling effectiveness (Yuca et al., 2017; Butler, 1987). However, only 9.6% of schools have them, representing systemic neglect of infrastructure. Moreover, the low proportion of professional counselors participating (5.7% of respondents) reflects a situation where unqualified teachers and head teachers are used in the delivery of G&C, which could compromise the quality of services. This finding aligns with Shah (2015) criticism of the ad hoc G&C policy implementation in Nepal, where policies are framed but not implemented, and resources are allocated. The study also exposed gender and institutional disparities.

Also, the ambiguity of Ethiopian and Kenyan teachers regarding G&C practices is reflected in the present study, where female teachers expressed more positive perceptions on G&C practices than their male counterparts (Arfasa, 2018; Ngeno, 2022). The results could indicate gender-specific expectations for caregiver roles or variations in training experiences. At the same time, no other substantial advantage of private schools over PS in effective G&C was observed with respect to PS, and PS made up 75.8% of the sample at that (the former) level. In other words, the underwhelming performance of many public schools (PS) was due to systemic issues rather than a lack of response advantages, suggesting that there are universal problems in education, such as overcrowding or bureaucratic inefficiency. Significant deficiencies were noted within certain G&C subsystems. Long-term goal setting (LS7–LS9), coping (SM7–SM10), and ethical decision-making (SS4–SS5) were particularly difficult for teachers to address. These voids may result in Nepal’s low educational achievement and high dropout rates (Bhatta and Mehendale, 2021). The small size of the Nagelkerke R2 (4.0–8.9%) also indicates that unobserved variables (e.g., socioeconomic barriers, parental support, and economic hardships) significantly influence school outputs. Based on the results of the study, inferences were drawn to address the research questions and hypotheses.

Regarding the current situation of G&C facilities in schools in Nepal (RQ1), teachers generally agreed that they were providing G&C support in LS, SS, and SM, with mean ratings of 3.76, 3.80, and 3.81, respectively, on a five-point scale. Characteristic skills were emphasized the most. Yet significant voids emerged, particularly in CTC outcomes such as long-term planning, taking challenging courses, and using data to inform decision-making. (2010) SM demonstrated deficits in persistence, coping, and flexibility. Infrastructure was particularly weak; just 9.6% of the schools had counseling rooms, and most sessions were held either in classrooms or with the counselor’s desk being shared in the office. There were also clear gender differences, with female teachers evaluating their G&C practices as significantly stronger than those of males, although no significant differences were found between public and private schools. For effectiveness (RQ2), SS interventions significantly increased the students’ positive behavior, decreased conflicts, and contributed to ethical behavior. Nevertheless, the interventions associated with LS and SM did not have a significant impact on school achievement or later academic success. According to the school performance indicators, the school environment was the most highly rated category (51.3% “Good”), and student behavior was average (55.2% “Normal”) with some degradations. Ratings of academic achievement were slightly more positive, while post-school outcomes were the lowest across the domains, with just 6.8% rating it as Good. Regarding infrastructure and staffing (RQ3), having designated counseling rooms and school counselors made a significant difference in the school climate, with these factors tripling the odds of good outcomes. Nevertheless, only 5.7% of schools had counselors; teachers or headteachers provided the majority of G&C services. Social/emotional concerns dominated the majority of counseling, while academic and career counseling received relatively little attention. Similarly, testing the hypotheses indicated that differences by gender and type of school (H1, H2, H3) were rejected, as significant differences were found in G&C practices when compared by the gender of the teacher and the type of school. H4, which hypothesized that G&C improves school outcomes, was partially supported in that student behavior (but not academic or post-school outcomes) improved following LS and SM. Infrastructure and trained staff, however, were found to have a positive association in the school environment.

7 Conclusion

Guidance and Counseling (G&C) is essential for supporting the holistic development of students of Nepali schools. Overall, this study reveals that while teachers actively use G&C in practice across LS, SM, and SS, the effectiveness of interventions in all areas remains unclear. The social domain was identified as the most interfering domain, and students’ behaviors improved through a decrease in conflicts and an influence on moral conduct. However, LS and SM did not have a significant impact on academic achievement and senior secondary success. Some critical areas, including goal setting, coping strategies, flexibility, and adaptability, were also laid bare. Structural constraints also restrict G&C efficacy in schools with separate counseling rooms and professional counselors. But those resources made all the difference; schools with dedicated counseling spaces were three times as likely to have favorable environments, and trained counselors had a comparably large effect. This is greatly compounded by the use of tired and undertrained teachers in the public schools. To better leverage G&C, Nepal must invest in professional development focused on LS and SM, establish infrastructure for counseling, create a preservice preparedness model (similar to the ASCA model that is being adopted by counseling in the United States), and recruit counselors with clearly delineated responsibilities. This systems logic is essential for closing the theory–policy–practice gap and enhancing academic resilience, socioemotional wellbeing, and post-school success for all students, thereby safeguarding their status as citizens in a democratic society and promoting positive youth development.

8 Limitations of the study

We must acknowledge the limitations of this research, which has provided valuable insights into the practice and efficacy of G&C in Nepali schools. First, the sample primarily consisted of public schools (75.8%) and male teachers (63%), which may limit the generalizability of the results to private schools and female teachers. The gender disparity in participants may also bias the perception of G&C effectiveness. Second, the use of self-reported teacher data, rather than objective indicators (e.g., student performance records, observational assessments), may introduce social desirability bias and subjectivity. For example, school performance indicators (e.g., environment, student behavior) relied on teachers’ reports, which may not completely reflect objective circumstances. Third, binary logistic regression models for all outcomes collectively showed low levels of explanatory power (Nagelkerke R2 ranged from 4.0 to 8.9), indicating that unmeasured controls (e.g., socioeconomic factors, parental involvement) will likely be at Work behind school performances. Along with confounding factors, the study design does not allow strong causal inferences to be made, and longitudinal data would be useful for demonstrating the long-term effects of G&C practices. Fourth, structural barriers in the Nepali schools, for example, the absence of a specific counselor (5.7%) and a special counseling room (9.6%), were observed but not thoroughly discussed. These infrastructural disparities may intervene in the association between G&C components and school performance. Furthermore, although a back-translation method was followed, there may also have been semantic errors during translation of the questionnaire from English to Nepali, which could have potentially impacted the reliability of the instruments. The cultural specificity, such as caste-based disparities (e.g., the ″untouchable caste″), also impedes generalizability to other settings. Finally, the study did not thoroughly examine why certain G&C components (e.g., LS, SM) did not significantly impact behavior, leaving a lack of understanding of the contextual barriers to their implementation. Future studies could overcome these limitations through the use of mixed methods, further sampling, and the establishment of collaborations between urban and rural schools for more longitudinal studies, enabling stronger causal claims and qualitative investigations into contextual barriers (such as cultural stigma toward counseling or resource disparities between urban and rural schools) to seeking assistance.

9 Recommendations

Based on the findings, several important recommendations have been suggested to improve G&C practices in Nepal. First, the teachers need training. It involves introducing compulsory short-term workshops and long-term certificate courses for teachers and headteachers to develop their competencies in providing life skills (LS) and social management (SM)-based counseling. Furthermore, we should include G&C modules in preservice and in-service teacher education, with a focus on evidence-based academic and career guidance policies. In terms of infrastructure, the provision of special counseling rooms in schools to maintain privacy, confidentiality, and the effectiveness of services should be paramount. Government, INGO, or NGO funding should support the establishment of these multi-functional G&C spaces in resource-constrained schools. Equally important are policy changes and institutional reforms. Education policy at the national level should also be changed to require the presence of counselors in schools who have specific roles and duties. A mandated G&C structure that parallels global models (e.g., ASCA) would be established to provide uniformity and accountability throughout schools. Community and academic partnerships should be encouraged to increase the impact of G&C programs. Collaboration among schools, universities, and NGOs could facilitate the development of context-specific training programs. Furthermore, developing online platforms, such as Massive Open Online Courses (MOOCs), can provide scalable and low-cost opportunities for professional development in remote locations. Ways to assess the impact of gender and G&C services should be implemented to ensure that systems to monitor and evaluate the effectiveness of G&C services are implemented, using a range of both qualitative and quantitative indicators. Post-counseling records at schools can be maintained to track the effectiveness of peer counseling; however, bureaucratic record-keeping has yet to be actively pursued. Finally, education and awareness-raising are also key. Sensitization campaigns should be initiated to educate stakeholders, including parents, policymakers, and students, about the vital role of G&C in holistic education. In doing so, schools can develop comprehensive G&C programs as a foundation for academic achievement, sound mental health, and lifelong success for all children.

Data availability statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

Ethics statement

The studies involving humans were approved by the Research Committee at the Faculty of Social Science and Education, Nepal Open University, Nepal. The studies were conducted in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. Written informed consent for participation was not required from the participants or the participants’ legal guardians/next of kin in accordance with the national legislation and institutional requirements.

Author contributions

JK: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Project administration, Resources, Software, Supervision, Validation, Visualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. MKH: Formal analysis, Funding acquisition, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. MNH: Formal analysis, Funding acquisition, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. ND: Conceptualization, Funding acquisition, Investigation, Methodology, Resources, Supervision, Validation, Visualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. DJ: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Project administration, Resources, Software, Validation, Visualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. NS: Investigation, Methodology, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. UA: Investigation, Methodology, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declare that financial support was received for the research and/or publication of this article. Partial publication grant was received from the Institute for Advanced Research Publication Grant of United International University, for the publication of this article. Ref. No.: IAR-2025-Pub-048.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank all the participants across Nepal for their contributions.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The authors declare that no Gen AI was used in the creation of this manuscript.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Supplementary material

The Supplementary material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/feduc.2025.1548424/full#supplementary-material

References

Ali, L., and Graham, B. (2001). The counseling approach to careers guidance (1st ed.). Routledge. Available onine at: https://imamhamzatcoed.edu.ng/library/ebooks/resources/Lynda%20Ali%20-%20Counselling%20in%20Careers%20Guidance_%20A%20Practical%20Approach%20(1996).pdf

Amat, S. (2019). Guidance and counseling in schools. 3rd International Conference on Current Issues in Education (ICCIE 2018). Available online at: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/334622929_Guidance_and_Counselling_in_Schools

Arfasa, A. J. (2018). Perceptions of students and teachers toward guidance and counseling services in Southwest Ethiopia secondary schools. Int. J. Multicult. Multirelig. Understand. 5:81. doi: 10.18415/ijmmu.v5i6.504

ASCA (2021). ASCA student standards: mindsets & behaviors for student success. Available online at: https://www.schoolcounselor.org/getmedia/7428a787-a452-4abb-afec-d78ec77870cd/Mindsets-Behaviors.pdf

Belsley, D. A. (1991). Conditioning diagnostics: collinearity and weak data in regression. New York: Wiley-Inter Science.

Bhatta, P., and Mehendale, A. (2021). “The status of school education in Nepal” in Handbook of education Systems in South Asia. eds. P. M. Sarangapani and R. Pappu (Singapore: Springer). doi: 10.1007/978-981-15-0032-9_16

Butler, M. J. (1987). Developing effective counseling facilities in schools [graduate research papers, University of Northern Iowa]. Available online at: https://scholarworks.uni.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=3158&context=grp

CEHRD (2024). Flash I report 2080 (2023/24). Available online at: https://cehrd.gov.np/file_data/mediacenter_files/media_file-17-428622471.pdf

Chilewa, E. A., and Osaki, K. (2022). The effectiveness of guidance and counseling practices on students’ career development in secondary schools in Temeke municipality. J. Humanit. Educ. Dev. 4, 160–181. doi: 10.22161/jhed.4.1.17

Cohen, L., Manion, L., and Morrison, K. (2018). Research methods in education. 8th Edn. London: Routledge. doi: 10.4324/9780203224342

Comba, R., Sharma, S., and Nestour, A. (2023). Data Must Speak: Nepal. Reports and Project Briefs. UNICEF. Available online at: https://www.unicef.org/innocenti/reports/data-must-speak-nepal

Di Fabio, A., and Bernaud, J. (2018). Introduction: postmodern guidance and career counseling interventions—the new scenario. In A. FabioDi and J. Bernaud (Eds.), Narrative interventions in post-modern guidance and career counseling, (pp. 3–14).Cham: Springer.

Diponegoro, A. M., and Agungbudiprabowo, F. H. (2020). A case study on guidance and counseling students’ perception in private university. Int. J. Sci. Technol. Res. 9, 539–543.

Hair, J. F., Sarstedt, M., Hopkins, L., and Kuppelwieser, V. G. (2014). Partial least squares structural equation modeling (PLSSEM): an emerging tool in business research. Eur. Bus. Rev. 26, 106–121. doi: 10.1108/EBR-10-2013-0128

Hrisyov, N. B., and Kostadinov, A. S. (2022). Effect of guidance and counseling on the students’ academic performance in Bulgaria. J. Educ. 5, 16–26. doi: 10.53819/81018102t50105

Kandel, S. (2020). Guidance and counseling services: an essential element to develop school. Educ. Nepal. 7, 2394–9724. doi: 10.33329/ijless.7.1.28

Karki, B., Subedi, D., and Dahal, N. (2024). Adolescent girls’ narratives on hesitation, realization, and adaptation of menstrual hygiene and sanitation practices. JMC Res. J. 13, 1–25. doi: 10.3126/jmcrj.v13i1.73383

Khadka, J. (2024) (Ed.). Guidance & counseling in schools: training manual for teacher trainers. Kathmandu: 21st CS Nepal. Faculty of Social Sciences and Education, Nepal Open University, Manbhawan, Lalitpur. https://issuu.com/eibur/docs/final_guidance_and_counselling_book#google_vignette

Li, L., Zhu, M., Yao, A., Yang, J., and Yang, L. (2023). Daily stress and mental health of professional degree graduate students in Chinese traditional medicine universities: the mediating role of learning career adaptation. BMC Med. Educ. 23:627. doi: 10.1186/s12909-023-04614-5

Masa’deh, R., Almajali, D., Majali, T., Hanandeh, A., and Al-Radaideh, A. (2022). Evaluating e-learning systems success in the new normal. Int. J. Data Netw. Sci. 6, 1033–1042. doi: 10.5267/j.ijdns.2022.8.006

Meinert, C. L. (2011). Biostatistics 101. An Insider Guide Clin. Trials 44, 137–150. doi: 10.1093/acprof:oso/9780199742967.003.0016

MOEST (2022). “Flash report I, 2022” in Government of Nepal, Ministry of Education, Science and Technology (Sanothimi, Bhaktapur: Center for Education and Human Resource Development). https://nepalindata.com/media/resources/items/0/bFlash_I_report_2078_2021_22.pdf

Ngeno, G. (2022). Students’ perceptions of the impact of guidance and counseling programs on academic needs satisfaction in secondary schools within the Rift Valley region, Kenya. Educ. Res. Rev. 17, 145–151. doi: 10.5897/ERR2022.4232

Nyutu, P. N. (2006). The development of the student counseling needs scale (SCNS)[doctoral dissertation, University of Missouri-Columbia]. Available online at: https://core.ac.uk/download/pdf/62761674.pdf

Parveen, D., and Akhtar, S. (2023). The role of guidance and counseling in schools: a literature review. Int. J. Indian Psychol. 11, 558–568. doi: 10.25215/1102.058

Poudel, T. N. (2017). An ethnographic study exploring gender-based violence at school in Nepal [doctoral dissertation, Kathmandu University School of Education, Kathmandu].

Sangroula, P. (2024). Lack of career counseling is Nepali students’ key concern since yesteryear. OnlineKhabar. Available online at: https://english.onlinekhabar.com/no-career-counselling-student-problem.html

Shah, N. K. (2015). Initiative for school counseling manual : Daayitwa Nepal Public Service Fellowship Summer 2014. Department of Education, Ministry of Education, Government of Nepal. Available at: https://daayitwa.org/storage/archives/1582520512.pdf.

Shaheen, S., Iqbal, M., and Shaheen, M. N. (2023). Impact of guidance and counseling services on students' development at the university level. J. Positi. Sch. Psychol. 7, 812–827.

Shrestha Rajbhandary, P. (2019). Involvement of parents in school counseling. Smart Family Website. Available online at: https://smartfamily.com.np/feature/involvement-of-parents-in-school-counseling

Shrivastava, K.K. (2003). Principles of guidance and counselling. Kanishka Publishers & Distributors. Available online at: http://library.lol/main/0B8DAC666A3F1B5DA092714DD4C4EEA4

Yuca, V., Daharnis Ahmad, R., and Ardi, R. (2017). “The importance of infrastructure facilities in counseling services” in 9th International Conference for Science Educators and Teachers (ICSET) (Acmarang: Universitas Negeri Semarang, Indonesia).

Yuen, M., Chan, R. M. C., Lau, P. S. Y., Gysbers, N. C., and Shea, P. M. K. (2007). Comprehensive guidance and counseling programmes in the primary schools of Hong Kong: teachers’ perceptions and involvement. Pastor. Care Educ. 25, 17–24. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-0122.2007.00421.x

Keywords: guidance and counseling, social skills, school environment, teacher training, education, educational policy

Citation: Khadka J, Dahal N, Hasan MK, Haque MN, Joshi DR, Subedi N and Acharya U (2025) Practice and effectiveness of guidance and counseling in Nepali schools: roles of learning strategy, self-management, and social skills. Front. Educ. 10:1548424. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2025.1548424

Edited by:

Aimee Quickfall, Leeds Trinity University, United KingdomReviewed by:

Julie Larran, Free University of Berlin, GermanyShankar Dhakal, Edith Cowan University, Australia

Copyright © 2025 Khadka, Dahal, Hasan, Haque, Joshi, Subedi and Acharya. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Niroj Dahal, bmlyb2pAa3Vzb2VkLmVkdS5ucA==

†ORCID: Jiban Khadka, orcid.org/0000-0002-7311-5779

Niroj Dahal, orcid.org/0000-0001-7646-1186

Kamrul Hasan, orcid.org/0000-0003-2353-4673

Nurul Haque, orcid.org/0000-0003-2046-8586

Dirgha Raj Joshi, orcid.org/0000-0002-1437-6661

Nirmala Subedi, orcid.org/0009-0006-4599-9235

Usha Acharya, orcid.org/0000-0003-1060-9875

Jiban Khadka1†

Jiban Khadka1† Niroj Dahal

Niroj Dahal Nirmala Subedi

Nirmala Subedi