- 1Department of Basic Education, Universitas Negeri Yogyakarta, Yogyakarta City, Indonesia

- 2Department of Philosophy, Sekolah Tinggi Filsafat Seminari Pineleng, Minahasa, Indonesia

- 3Department of Civic Education, Universitas Negeri Yogykarta, Yogyakarta City, Indonesia

Many children who live in the interior and mountainous areas of Papua-Indonesia do not get the right of education. This research aims to formulate a theoretical concept of boarding school-based character education by implementing Papuan cultural contextual education in the process of education. The method used is a qualitative method with a grounded theory approach. The research participants were 14 people. Data were collected through semi-structured interviews and textual analysis of the interview results. The data analysis technique uses the Atlas.ti application by using three levels of coding: open coding, axial coding, and selective coding. The research results show that there are six main concepts as a model of boarding school character education: personal development, spiritual development, extracurricular activities, clean and healthy lifestyles, learning from inspirational figures, and academic development. These six theoretical concepts can be divided into internal and external character building. One of the uniqueness of character education is the integration of local cultural values in the whole process of character education of the children, both in the school environment and in the dormitory. The results of the study provide insights for educators, schools, and government on different forms of character education models.

1 Introduction

Character education is a learning process that aims to shape the moral values, ethics, and personality of learners through teaching and real experiences. This education plays an important role in shaping students’ personalities and building their morality in the school environment. Character education is very important and fundamental for students in the age of technology (Kim, 2023; Yulia et al., 2022). In fact, this has become a major topic in various scientific discussions (Brestovanský, 2024). Character education in the United Kingdom and the United States of America fuelled political activity, as governments and educators saw that character education could be used to address social problems (Jerome and Kisby, 2019; Hastasari et al., 2022). In the context of Indonesian society, especially in the Papua region where social conflicts often occur (Ismail, 2023; Sanra et al., 2023; Scott and Tebay, 2005), character education in schools is important and urgent to teach mutual respect and non-violent problem solving from an early age. In addition, Indonesian society has many cultural values, languages, customs and traditions (Mailin et al., 2023; Asfina and Ovilia, 2017), so character education in schools helps preserve local wisdom to build the morals of the younger generation. On the other hand, infrastructure problems, lack of trained teachers (Naibaho, 2023; Madhakomala et al., 2022), and difficult access to education (Suhendar et al., 2024) for students scattered across Indonesia’s islands are major challenges to the implementation of character education. However, there are also societies in various countries that are experiencing a crisis of morality and virtue (Kayange, 2023). These groups are students who live and stay in rural, underdeveloped, and remote areas. They face economic challenges and financial constraints. In addition, they have not had adequate access to formal education, especially character education (Stone, 2023). Their opportunities for access to education (Prasetio et al., 2021) and information technology are also limited.

Some students living in rural areas may face challenges such as political instability (Viartasiwi, 2013), social conflict (Roberts and Green, 2013), complex social dynamic, including the potential for intergroup unrest or tension (Yampap and Haryanto, 2023; Putra et al., 2024) marginalization and oppression (Kebede et al., 2021). They experience hygiene and health issues (Chambers et al., 2024; Bourke et al., 2012), difficulties in socialising with others, increased school dropout rates (Liu, 2004), even 50% of rural students lose their right to learn (UNICEF, 2016; Ravet and Mtika, 2024), lack of qualified teachers (Ravet and Mtika, 2024), lack of education funding (Wallin and Reimer, 2008). Students also lose access to role models or mentors who can provide strong character guidance and limited services. Many parents face challenges in assisting their children in education, which is influenced by factors such as low levels of education and economic limitations (Li et al., 2024; Hermino and Arifin, 2020; du Plessis, 2014; Guo and Chen, 2023). On the other hand, local wisdom and traditional values remain an important aspect of rural community life, playing a role in shaping social norms and educational practices in these communities. Therefore, Character education plays a role in strengthening local cultural values by enabling young people to understand, adapt, and integrate these values in the face of globalization and technological change (Lukman et al., 2022; Handayani et al., 2023).

The problems described above are also experienced by students in the inland and outermost regions of Papua Indonesia (Yampap and Haryanto, 2023). These issues, if left unaddressed, can affect children’s psychology. Limited physical and social access to the outside community makes students feel isolated and lonely. Children tend to feel inferior when they are with friends who are outside their environment and culture. This leads to lack of confidence, fear, reluctance to open and lack of motivation to learn (Yao, 2022). Therefore, one of the efforts to overcome this problem is to improve the quality of dormitory-based character education. Dormitory-based character education is an educational approach that brings students from inland and outermost areas to live and learn with teachers in a dormitory environment for a period. This assertion is relevant to Liu and Villa (2020) research findings on children in rural China who live and study in dormitories. They found that boarding schools can improve cognitive outcomes, create better learning, and help children from disadvantaged family backgrounds.

The education system in Papua Indonesia faces significant geographical challenges, with most indigenous people living in remote inland and mountainous areas. They come from diverse ethnic communities with strong cultures. As a result, education is often shaped by local traditions and limited access to infrastructure. Education in Papua is regulated by the central Indonesian government. In practice, however, many remote and outermost areas have limited educational services and facilities, teaching staff and teaching materials. Even most marginalized communities in Papua’s interior and mountainous areas are illiterate (Wahudin et al., 2021). The central government has sought regional autonomy solutions and special programmes such as the Papua Special Autonomy (Keliat et al., 2021; Hasibuan, 2022; Sopaheluwakan et al., 2023) to improve the quality of education, but the results are still mixed, and the quality of education remains uneven (Dewi, 2024). Despite this, Papuans have strong local traditional values. Papua has a diverse cultural wealth, with more than 250 local languages and a strong tradition of cooperation and spirituality. This phenomenon provides an opportunity to implement local wisdom-based child character education (Yampap and Haryanto, 2023). Zhou and Xu (2021) explained that boarding schools help students to accept the phenomenon of multiculturalism and enhance students’ socialization (White, 2004).

Taruna Papua Indonesia Boarding School is a formal primary and secondary school that integrates local cultural values with school learning and boarding life. The school is managed by the Lokon Education Foundation. There are approximately 1,356 students who are taught and cared for at this boarding school. The boarding school is a place of learning and development for around 1,356 students who actively participate in the learning process, coaching and boarding life. They come from two indigenous ethnic communities: the Amungme who live in the mountains, the Kamoro who live on the coast, and five other related ethnic communities: the Moni, Dani, Nduga, Damal and Lanny. This assertion is supported by Katanski (2005) statement that boarding schools are deliberately created to unite children from different countries with different ethnicities, languages, and to preserve local cultures in schools. As an attempt to overcome the situation that divides ethnic communities.

Although this is not the first research on dormitory-based character education, the novelty of this research focuses on an in-depth analysis of a Papuan contextual culture-based character education model for students from the mountainous interior and coastal suburbs. These students not only come from different ethnicities, cultures, and languages, but also have differences in character, attitudes, and relationship patterns.

Therefore, the purpose of this research is to analyze a dormitory-based character education model by implementing Papuan cultural contextual education in all education and childcare. The central question of this research is how to develop a character education model for boarding schools, especially for students in the outermost and inland regions. This research is expected to be a new character education model in integrating local Papuan cultural values into school learning and children’s daily life in dormitories. The character and personality education of children will be carried out through an integrated system between school and out-of-school influences.

2 Literature review

Character education is a national movement to create schools that develop ethical, responsible; and caring young people by modeling and teaching good character through emphasis on universal values that we all share (Pala, 2011; Frye et al., 2002; Singh, 2019). Good character education is one of the keys to education in schools (Faizin, 2019). Character education has been implemented from pre-school to higher education (Hoge, 2002; Althof and Berkowitz, 2006). Character education differs from moral education. Moral education tends to be theory-based, constructivist and cognitively structured (Althof and Berkowitz, 2006; Chan, 2020). In contrast, character education is often considered more ideologically neutral than moral education. Character education focuses on achieving behaviors that are considered positive in a particular social and cultural context (Chan, 2020). These behaviors may vary depending on societal norms, educational policies and the values espoused by the educational institution. Lickona et al. (2002) emphasises that character education has three main elements: knowing the good, wanting the good and doing the good. The meaning of goodness depends on the social norms, cultural values and ethical principles adopted by a community or education system.

Based on these three elements someone is considered to have a good character if they know the good (moral knowledge), have interest in the good (moral feeling) and do good (Rokhman et al., 2014). Therefore, character education aims to develop students’ ability to make good and bad choices to understand, interpret, and uphold what is good, and to recognize this goodness in everyday life. In this regard, Lickona (2015) mentions seven essential and primary character elements that can be developed in boarding school, namely sincerity or honesty, compassion, courage, kindness, self-control, cooperation, and diligence or hard work. These seven core character traits are the most important and primary to develop in students at school, in addition to many other character values. The same opinion is expressed by Singh (2019), namely character education is the intentional, proactive effort by schools, districts, and states to instil in their student’s important core, ethical values such as caring, honesty, fairness, responsibility, and respect for self and others.

Some of these character-building values are very relevant to be integrated into boarding school education. In dormitories, students learn to live independently, manage their time and organize their personal needs without depending on the family. This assertion is relevant to the research findings of Muawalin et al. (2023) that there are several character values that are formed in students who live in the O Ngalah Islamic Boarding School, namely the characters of responsibility, courage, commitment, independence, discipline, wisdom, simplicity and cooperation in doing a job. In addition, the different ethnic, linguistic, economic, social and cultural backgrounds of the children are strengthened through dormitory-based character education (Huda and Mujahadah, 2021). The pattern of boarding school character education makes these differences a means of instilling tolerance, a sense of unity, cooperation and religious values (Marzuki, 2024). Other research shows that boarding school life makes children diligent in worship, reading the holy book, dressing neatly, caring for the environment and being responsible (Riski et al., 2023). Boarding education becomes a platform for promoting social harmony education and a sense of unity in diversity.

Local culture is all the ideas, activities, and results of human activities in a community group in a particular place. Thus, local cultural sources are the values, activities, and outcomes of traditional activities (Pangalila et al., 2021b). Local wisdom can function as advice, beliefs, literature, taboos for conservation and protection of natural resources, human resource development, culture, and science, social, political, ethical, and moral (Berkowitz and Ben-Artzi, 2024; Pangalila et al., 2021a). Character education is a deliberate effort to develop good character based on core values that are good for the individual and good for society (Faizin, 2019; Singh, 2019).

Schools become agents for cultivating character values through learning and internalising of local cultural values (Berges Puyo, 2020). Local culture-based education is a strategy for creating and designing a learning experience that incorporates culture as part of the learning process. The main elements of local culture-based character education are the integration of local cultural values in the learning curriculum, teaching materials that reflect the local culture, teachers and trainers who involve local communities, and respect for diversity (Yampap and Haryanto, 2023). The aim of culturally responsive character education is for students to quickly understand knowledge, identity, and moral values in the context of their daily lives. Other research by Yampap and Haryanto (2023) shows that tradition of burning stones, practised by indigenous Papuan Indonesians can promote students’ sense of nationalism, mutual respect, solidarity, togetherness, concern for others, and gratitude to the Almighty (Karyadi and Khasanah, 2020).

Some of the descriptions above show that character education is developed through the integration of cultural values and local wisdom in Papuan schools (Sulasmono, 2017). For example, respect for traditional leaders teaches character values that emphasize ethics and respect, as they are seen as the guardians of the community’s cultural and moral values (Ambang, 2007). Character education from the local context is easier for students to understand and accept because it is in line with their life experiences. Local cultural values strengthen children’s cultural identity and morality. What is important in character education is that schools not only build moral individuals, but also protect cultural heritage from the influence of globalization. Character education as a tool for cultural preservation (Sulasmono, 2017). Character education based on local culture plays an important role in preserving Papua’s unique culture (Petrus and Rahanra, 2022; Handayani et al., 2023). By incorporating cultural values into education, schools can become agents of cultural preservation while strengthening students’ character to maintain their cultural identity in a changing world (Karyadi and Khasanah, 2020).

Boarding education is an educational approach in which students live and learn in a community. The school provides different types of accommodation for students during their education. Teachers and students live together in a community. Lomawaima and Whitt (2023) criticize how boarding schools are often used as a means to change the cultural identity of young people by reducing their ties to their home community while imposing a particular system of discipline. For this reason, boarding school education is holistic. Students are involved not only in academic learning but also in extra-curricular activities (Dvali, 2024) such as arts, health, sports, literacy, discipline, respect, independence, hard work, discipline, self-confidence, physical fitness, and other social activities (Lomawaima and Whitt, 2023; Zhang, 2020; Yaxuan, 2023). These values are instilled in students through school rules, daily routines, and interactions with staff and fellow students.

Students living in boarding schools have a strong sense of community (Gangloff, 2024). Students participate together in all activities such as prayer, study, and sport. Trafzer et al. (2006) found that students must adapt to a regulated daily schedule: waking up, resting, queuing for meals, going to class, study times set by bells. Boarding schools also reduce undesirable student behavior, such as absenteeism (Martin et al., 2014). A survey conducted by the The Association of Boarding Schools (2013) found that 68% of boarding school students believe that boarding school helped them improve self-discipline, maturity, independence, cooperative learning, and critical thinking. The aim is to form a positive spirit of solidarity, eliminate negative feelings, interpersonal communication and get along harmoniously with housemates (Zhang and Tan, 2023).

The dormitory not only has the basic functions of life support, but also has the special function of educational functions. It is a bridge for teachers and students to communicate feelings and ideas, a platform for students to cultivate their mental health and independence, and a cradle of civilized behavior and high moral feelings. Therefore, dormitories are called the “first society,” “second family” and “third classroom” for students (Zhao and Liu, 2022). Residential education has existed in Indonesia since independence. The aim is to educate and nurture indigenous people who were not given the opportunity to learn by the colonisers (Fithriyah et al., 2023). Currently, boarding education in Indonesia is more about holistic education, namely formal education and education of religious spiritual values (Arif et al., 2024). One of them is boarding education in several pesantren in Indonesia, which has become the best practice of character education of children according to the needs of the time (Perdana, 2015).

3 Method

3.1 Research approach

This research uses a qualitative method with a grounded theory approach. Grounded theory is a qualitative method that inductively uses a set of systematic procedures to provide a theory about the phenomenon under study (Corbin and Strauss, 2014). The aim of this method is to build a theory that provides an abstract understanding of one or more of the core issues under study (Charmaz and Thornberg, 2021). The advantage of grounded theory is that it is able to generate theories based on data in the field rather than on existing theories. Grounded theory is also flexible and suitable for exploring social phenomena with an inductive approach, not tied to initial hypotheses. The disadvantage, however, is that grounded theory analysis is subjective, dependent on the researcher’s interpretation, takes longer, and is not very easy for novice researchers.

3.2 Participants/sample selection

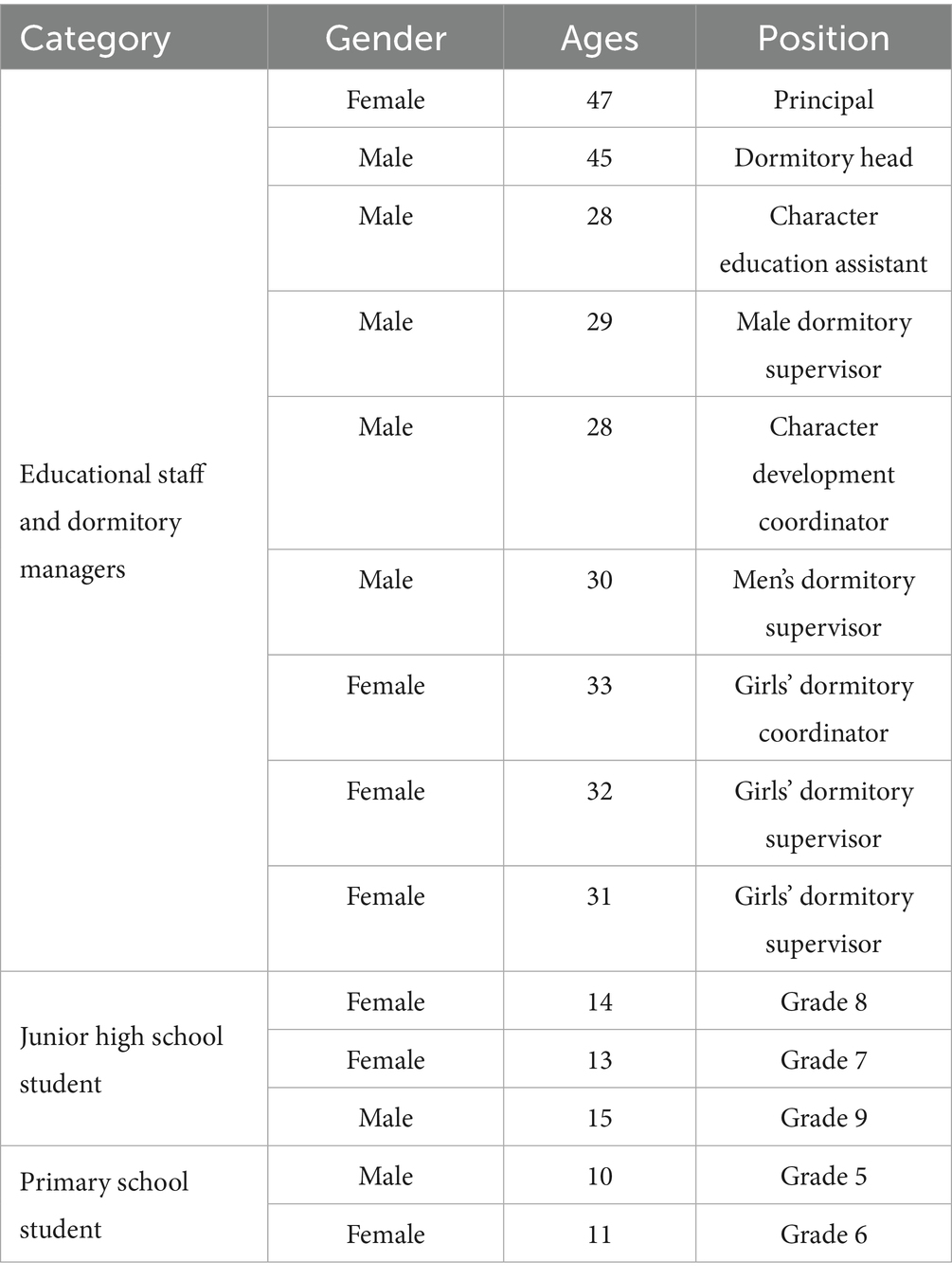

There were 14 participants in this study, consisting of the educational staff & dormitory managers, Junior High School Students and Primary School Students. This study employed purposive sampling to consider the diversity of roles and certain demographic characteristics relevant to the study’s objectives. Participants in this study were selected to reflect the diversity of roles in character education in boarding schools. To obtain a comprehensive view of character development, participants were selected based on the diversity of roles within the school ecosystem. Selection criteria included experience with and direct involvement in character education, as well as availability and readiness to participate. All participants came from the same boarding school: Taruna Papua School. To maintain transferability, the researchers provided detailed descriptions of the school’s context, learning system, and social environment characteristics. This allows readers and other researchers to evaluate the applicability of the results to other contexts. Educators and dormitory managers provided managerial and operational perspectives on character education, while students from primary to junior secondary school provided insights into their direct experiences. Gender differences were also considered to understand the dynamics of character education in different dormitory environments. In addition, differences in age and level of education allow for the analysis of character development over time. The students involved in this study were purposely selected based on their above-average cognitive abilities and personal development compared to their peers. With a focus on the boarding school system, this study aims to examine in depth how the boarding school environment contributes to students’ character development. Semi-structured interviews were conducted face-to-face in school classrooms between January and March 2023. Interviews with students were conducted in quiet classrooms during breaks and away from teachers and other school staff. This was done to minimize the influence of authority figures and ensure that students felt comfortable expressing their opinions freely. Each interview lasted between 30 and 45 min. Students received direct permission to participate in the interviews from the school principal and dormitory director (Table 1).

3.3 Data collection methods

The data collection techniques were semi-structured interviews with participant. The interview questions focused on the boarding school’s work programs and character development programs for students. The next data collection procedure was documentation. The researchers collected various documentary data related to school and dormitory curriculum design, boarding school character education rules and policies, and photos/documentation of local culture-based character development activities in the school and dormitory environment. As a next step, the research team conducted direct observations of students’ character development learning activities and extracurricular activities at Taruna Papua Timika School, Indonesia. To validate the data collection methods, the researcher used data triangulation from different informants and finally conducted discussions with peers in the form of focus group discussions (Creswell and Creswell, 2018). Researchers act as observers and have relationships with the community under study. In interviews, researchers use a child-oriented approach, non-hierarchical communication, to make participants feel more comfortable.

3.4 Data analysis procedures

The Atlas.ti application was used for data analysis. Data analysis starts with the coding stage, which is divided into three stages, namely open coding, axial coding, and selective coding (Li, 2022; Hamedinasab et al., 2023). The process of data analysis consists of three stages.

1. Open coding: providing codes/labels from each of the data collected through interviews, observations, documentation and focus group discussions (FGDs). The raw data sets were identified using keywords, phrases or recurring patterns. The process involved reading the transcripts in depth, finding patterns or keywords that appeared frequently, giving each theme an initial code, and grouping similar codes into broader categories such as personal development, spiritual development and academic development.

2. Axial coding: rearranging the codes/labels obtained through open coding by making connections between categories and their subcategories that indicate causal conditions, phenomena, contexts, influencing conditions, action/interaction strategies and consequences. The researcher linked the concepts identified through open coding, identified the core categories that influence students’ character development, and analyzed causal relationships, such as the role of interaction with caregivers and the boarding environment. The end result is a conceptual model that describes the factors that shape the character of boarding school students.

3. Selective coding. The researcher selects core categories and develops a narrative or theory that integrates all the categories identified in the previous stages (Corbin and Strauss, 2014). The aim of this stage is to develop a core theory based on the patterns found. The process involves selecting the main categories, systematically linking them to other categories, checking the consistency of the data and formulating the final theory on the role of boarding schools in shaping the character of students from the interior and the outermost regions.

4 Results

Open coding is the process of coding sentence by sentence from the original data. There were 14 respondents who provided responses on the topic of the dormitory-based character education model at Taruna School in Papua Indonesia. After several rounds of careful analysis, the researcher obtained 27 categories of initial concepts that appeared frequently. The results of processing the initial categories from the initial coding are presented in Figure 1 in the form of word clouds.

Figure 1 shows that the main theme of this research is development. Development includes various aspects of character, spiritual activities, inspiration from Papuan leaders, community activities, education and extracurricular activities. The results of this research illustrate how elements such as spirituality, the role of local figures, community activities and character education work together to support individual development in Papua with a holistic and culturally based approach.

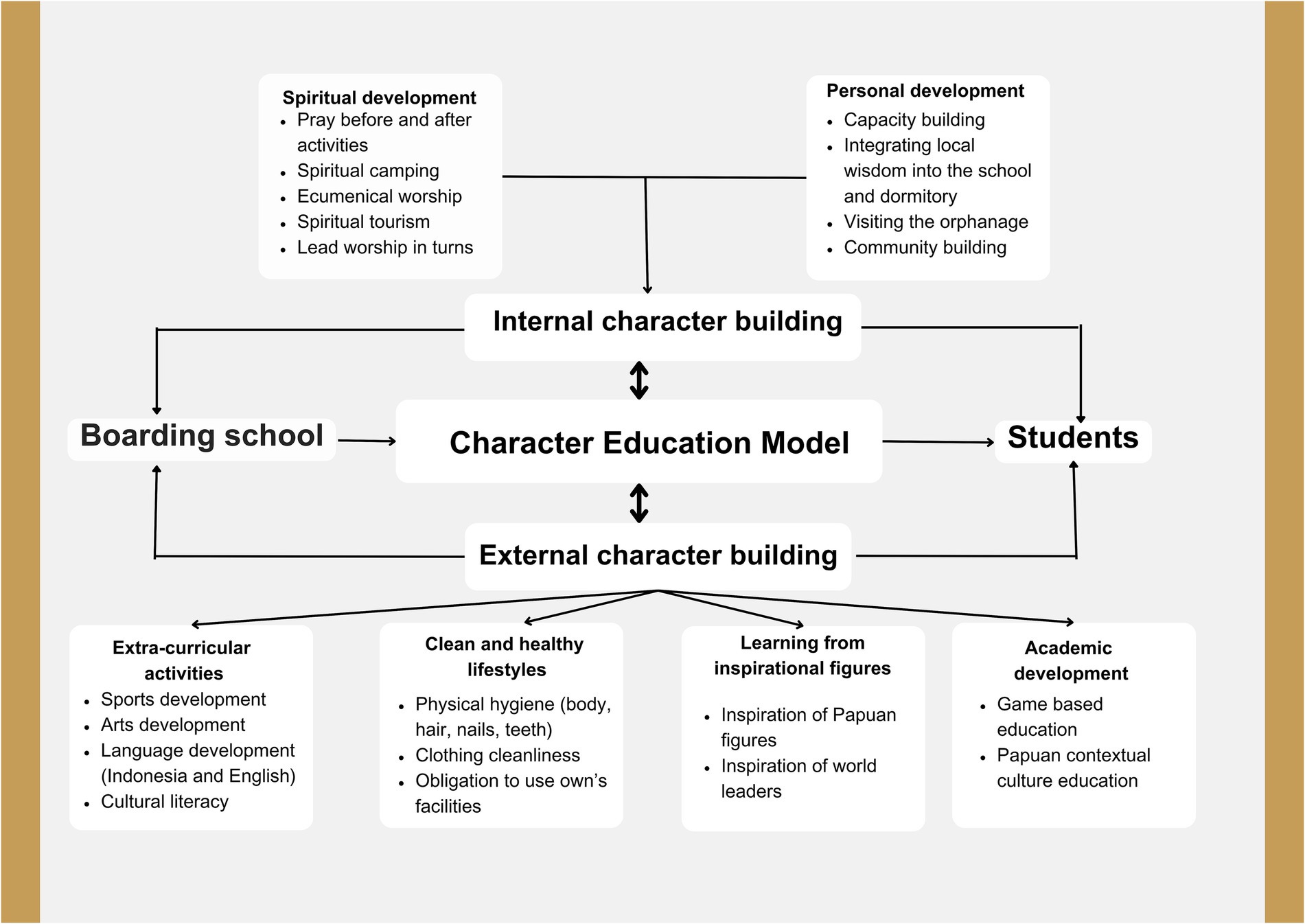

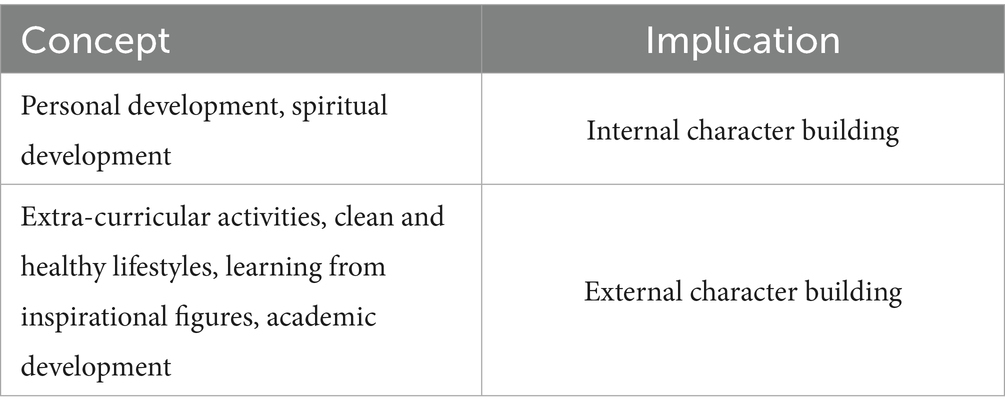

In the next stage, the researcher conducted axial coding using cluster analysis of the open coding data. In this way, the researcher combined similar codes to construct a more general macro concept. Based on the 27 frequently occurring categories, the researcher found six theoretical concepts as a form of dormitory-based character education model at Taruna Papua School, namely personal development, spiritual development, extracurricular activities, clean and healthy lifestyles, learning from inspirational figures, and academic development (Figure 2). Furthermore, the researcher made logical connections between these concepts and finally the theoretical structure is shown in Table 2. In addition, the concepts of personal development and spiritual development were grouped into internal character building. External character building includes the concept of extracurricular activities, clean and healthy lifestyles, learning from inspirational figures and academic development.

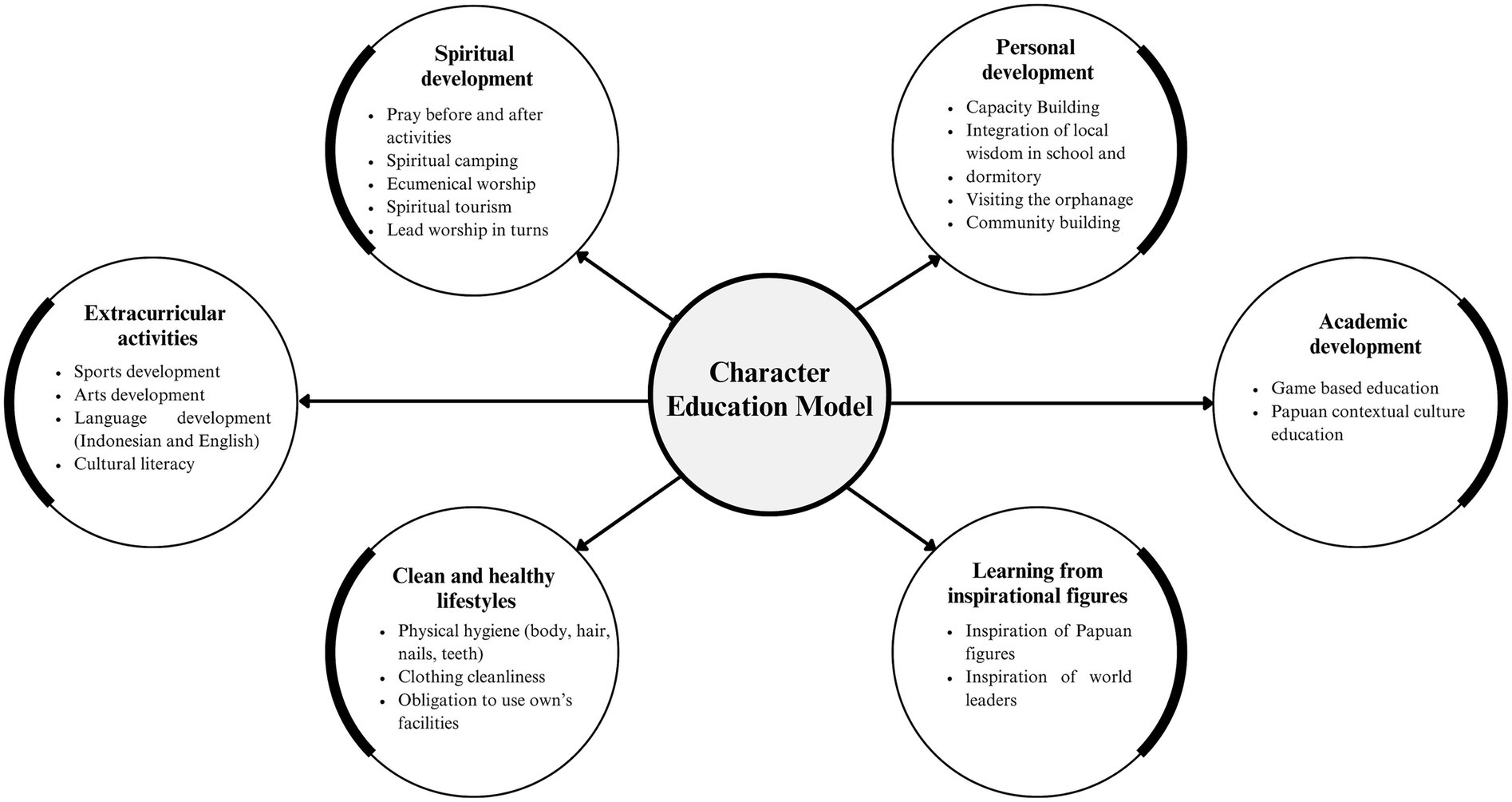

Based on the six core concepts and the results of clustering character education through the first two levels of coding, the researchers used selective coding to build a theoretical model of character education. We call this ‘dormitory-based character education theory’ (Figure 2). The axial coding results (Figure 3) show that each core concept has subcategories. Self-development has four subcategories, namely capacity building, integrating local wisdom in schools and dormitories, visiting orphanages, and building communities.

Results of this axial coding analysis show that personal development refers to increasing students’ self-competence in both academic and social aspects. By involving students in activities that promote social interaction (Chatzipanteli and Adamakis, 2022) and build a good community (Hooper, 1940), students can learn the importance of local wisdom and a sense of responsibility for the surrounding environment (Freire, 2000). The concept of spiritual development has five subcategories, namely praying before and after activities, spiritual camping, ecumenical workship, spiritual tourism, and leading worship in turn. Spiritual development is an important foundation for character education. Increased student involvement in religious practices can build moral awareness and strong ethics in students (Miller, 2000).

The concept of extra-curricular activities has four subcategories namely sports development, arts development, language development (Indonesian and English) and cultural literacy. Extracurricular activities such as sports, arts and language learning add another dimension to character education (Mathias and Mubofu, 2022). These activities help students to develop social, creative and communication skills, which are essential for holistic self-development (Eccles and Barber, 1999). The concept of clean and healthy lifestyles has three subcategories, namely body hygiene (body, hair, nails, teeth), clothing hygiene, and the obligation to use own’s facilities. Teaching students about hygiene and physical health is an important part of character education. A disciplined lifestyle in maintaining personal health reflects personal responsibility, honesty, cooperation and an awareness of the importance of health in achieving life goals (Siti Kamilah Suwarna et al., 2024).

The concept of learning from inspirational figures has two subcategories, namely inspiration from Papuan figures and inspiration from world figures. Learning from inspirational figures helps students to develop strong visions and values. By recognising successful local figures and global leaders, students can see real examples of success and good morals that become sources of motivation and role models (Bandura, 1977). The concept of academic development has two subcategories, namely game-based education, and Papuan contextual cultural education. The discovery of this concept shows that a game-based learning approach makes learning more interesting and engages students. In addition, Papuan local culture education strengthens students’ cultural identity while preparing them for global challenges (Gee, 2003). The description of the research findings of the character education model in this study aims to incorporate various important elements such as spiritual development, academic, personal, health and extra-curricular activities. With a holistic approach and rooted in the local Papuan culture, this model not only forms students’ character morally, but also develops them intellectually, physically and socially.

Figure 2 shows that the character education model can be divided into two parts: first, internal character building, which includes spiritual development and personal development; second, external character development which includes extracurricular activities, clean and healthy lifestyles, learning from inspirational figures and academic development. Effective character education combines these two aspects in a balanced way. Holistic character education in boarding schools helps everyone to develop positive moral values and attitudes internally, while strengthening environmental influences and external role models to support the development of good character.

5 Discussion

The general findings are to identify and explain the concept of character education of students in boarding schools. One of the uniqueness of character education is the integration of local cultural values in the whole process of children’s character education, both in the school environment and in the boarding house (Iulia, 2015). One of the distinctive features of character education at Sekolah Taruna Papua Indonesia is the strong integration of local wisdom. Traditional values respected by Papuan ethnic communities, such as gotong royong, solidarity, hunting behavior and respect for nature, become the focus and main reference in the learning process (Yampap and Haryanto, 2023). In this context, the learning process does not only take place in the classroom, but also outside the classroom or in traditional ceremonies. Some of these peculiarities are integrated in several character development programmes, both in the school environment and in the dormitory.

This finding is relevant to Guo and Chen (2023) statement that boarding schools should pay attention to character education that incorporates local language, community cultural values and family culture. Although students live and stay in dormitories away from their families, local language, cultural and family values are still preserved in boarding school life. Boarding education does not remove children from local cultural values such as local language and family culture. Integrating local culture into the character education of boarding students further strengthens and enriches the value of local wisdom in education. Birquier et al. (1998) assert that the traditional culture inheritance function of the family is irreplaceable in protecting the transmission of moral values from generation to generation. Katanski (2005) asserts that representations of the boarding school experience in late 20th century Native American literature express a complex combination of cultural nationalism and solidarity.

The results of a previous study showed that the main reason for student absenteeism (46.52%) in Papuan schools was illness. Other reasons for student absenteeism are related to socio-economic and geographical conditions such as not having transportation, facing bad weather, being treated badly by other students or teachers, not having food at home, lack of clean water, and not having a teacher at school (Nielsen, 2015; Karon et al., 2017). This phenomenon encourages Taruna Papua Indonesia boarding school to integrate character education in boarding school with a clean and healthy lifestyle for students.

The results showed that one form of character development is a clean and healthy lifestyle. Dormitory supervisors help students to live a healthy and clean lifestyle, both in terms of personal hygiene (body, hair, nails, teeth) and clothing hygiene. Students are required to use their own facilities. They are not allowed to use other people’s bathing facilities or clothing. Students are given nutritious food every day. Similarly, Trafzer et al. (2006) states that the boarding school experience has changed the lives of thousands of Native American children. The boarding school pattern of education transformed students from ‘savages’ to ‘civilized’ people. Boarding school officials bathed children and cut their hair to kill lice (Li et al., 2024). Marasinghe et al. (2024) found that the boarding school environment had an impact on students’ health. Every day, housemasters regularly open the windows to increase the flow of air in the dormitories. The design of the dormitories and a healthy environment provide comfort and health for the children.

The form of dormitory-based character education model at Taruna Papua School, namely play-based education, and Papuan contextual cultural education, can improve students’ learning outcomes and motivation. Through language development, students can already write and speak English fluently. Their motivation to learn is increased through game-based learning and Papuan contextual cultural education. Boarding schools help students receive multicultural education, increase students’ socialization (White, 2004), and improve students’ academic performance (Zhou and Xu, 2021). Boarding schools improve and standardize students’ learning time by providing a good learning environment (Zhong et al., 2024; Yao and Gao, 2018), which in turn improves students’ academic achievement (Foliano et al., 2019; Curto and Fryer, 2014). Similarly, Martin et al. (2014) found that boarding students had more continuous access to professional educator education than non-boarding students. Kahane (1988) believes that boarding schools provide opportunities for students to experience roles and rules, thereby promoting the all-round development of students.

One of the character education concepts found in this research is that students learn from inspirational figures. Students are given the opportunity to watch, listen and learn from the lives and inspirations of indigenous Papuan figures and famous world leaders. A distinctive feature of Papuan society is the strong respect for traditional leaders or cultural chiefs. The example and inspiration of traditional leaders provide indigenous Papuan children with a living example of how to maintain local cultural identity, ethics, morals and local wisdom values (Yampap and Haryanto, 2023). Similarly, Trafzer et al. (2006) found that Indian children living in boarding schools are increasingly enjoying and learning about moral values through public programmes, meaningful films, and publications. They use the lessons they learn at boarding school to contribute to the well-being of their families and ethnic communities. The boarding school experience has changed the lives of thousands of Native American children. Boarding school life has a positive impact on the emotional development of students (Vicinus, 1984).

Character education based on local cultural values implemented by the Taruna School in Papua, Indonesia, is the best solution for values and character education for students from inland ethnic communities. Boarding schools train students to be competitive in the future and provide happiness to children from disadvantaged and poor families (Martin et al., 2021; Behaghel et al., 2017; Guo and Chen, 2023). Sekolah Taruna Papua provides good learning services not only with learning facilities, art, prayer, health, and sports services, but all students are given equal access rights in the whole educational process, both in schools and dormitories. This finding is relevant to Tomaševski (2001), who criticized the government for focusing only on the facility needs of boarding schools, but two aspects of rights-based education are often overlooked, namely the acceptability of education and its adaptability to the perspectives of local stakeholders. This concept of character education criticises many boarding schools for prioritising business and economic interests; without paying attention to the value and character education needs of the students. This reality often leads to parents no longer sending their children to boarding schools (Guo and Chen, 2023).

The results of this study also show that the extra-curricular programme is an interesting model of character education and is very popular with students (Figure 3). Extracurricular activities help to develop students’ character in the areas of art, music, sport, and language skills (Mathias and Mubofu, 2022). The research shows that the Taruna Papua boarding school integrates extracurricular activities with local Papuan wisdom, such as traditional dances, regional music, folklore and folk games. The programme teaches children the values of togetherness, cultural identity and pride in local Papuan heritage. Sismanto (2023) states that one of the models of character development of students in schools is to integrate character values through extracurricular activities. The same is also emphasized by Dvali (2024) that the formation of students’ personality and character is carried out through a holistic system unity between school learning activities and extracurricular activity programmes (Faizin, 2019).

The results also show that Taruna Papua School provides character education for students through spiritual development. All students are required to pray together before and after activities. The boarding school provides counseling for students with personal problems. Each student takes turns leading worship, scripture reading and deep reflection in both ecumenical work and other spiritual activities. During the holidays, students engage in spiritual camping and tourism and share spiritual experiences among themselves. Some of these activities aim to develop students’ character through spiritual development activities. Spirituality is an inherent aspect at every stage of human development and is an integral part of human life. Spiritual life is an essential part and defining character of human beings (Sagala, 2018). Hilmi et al. (2020) emphasize that in a boarding school environment, youth can deepen their spiritual understanding and practice, which is often rooted in the religious values and traditions of their community.

One of the advantages of boarding schools is that students’ learning outcomes and academic skills improve. Students have regular and scheduled study time. Dormitory assistants supervise and guide them while they study in the study room. In fact, the study found that some indigenous Papuan children can quickly become fluent in English and participate in English speaking competitions at the district and national levels. The findings of this study are emphasized by Martin et al. (2014) that boarding students can receive more continuous professional education than students who do not live in dormitories. Boarding schools improve and standardize students’ learning time by providing a collective learning and living environment (Yao and Gao, 2018), which in turn improves students’ academic performance (Curto and Fryer, 2014; Behaghel et al., 2017).

6 Conclusion

This study aims to answer the question: How is character education implemented in boarding schools for students from inner and outer regions? The findings reveal six core concepts of character education that serve as a foundation for shaping students’ personal development. These findings highlight key issues in character education, such as the influence of internal factors (boarding environment, teacher roles, and curriculum) and external factors (family involvement, cultural background, and school policies). The results of this study have important implications for educators, schools, and policymakers in developing a more structured and targeted approach to character education. The distinction between internal and external character education models can aid in designing policies that align with students’ specific needs.

However, this study has some limitations. The scope is restricted to specific boarding schools, and findings may not be directly generalizable to all institutions. Additionally, the qualitative approach used in this research provides in-depth insights but lacks statistical validation. Future research should employ quantitative methods to test the relationships between key variables and further explore challenges such as bullying, student anxiety, and emotional detachment from family. Another limitation of this study is that it was restricted to a single boarding school. However, the results open up the possibility of further research examining character education models in boarding schools across different institutions and regions. By addressing these aspects, this study contributes not only to character education theory but also to practical strategies for fostering a more supportive and effective learning environment in boarding schools.

Data availability statement

The datasets presented in this study can be found in online repositories. The names of the repository/repositories and accession number(s) can be found at: https://www.preprints.org/manuscript/202408.1842/v1.

Ethics statement

The studies involving humans were approved by the Universitas Negeri Yogyakarta, Indonesia. The studies were conducted in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. Written informed consent for participation in this study was provided by the participants’ legal guardians/next of kin.

Author contributions

KoS: Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. HH: Conceptualization, Methodology, Writing – review & editing. JO: Investigation, Supervision, Validation, Writing – review & editing. KuS: Formal analysis, Investigation, Resources, Validation, Writing – review & editing. MM: Project administration, Resources, Software, Validation, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declare that financial support was received for the research and/or publication of this article. This work was funded by the Indonesian Education Scholarship, Center for Higher Education Funding and Assessment, and Indonesian Endowment Fund for Education.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The authors declare that no Gen AI was used in the creation of this manuscript.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

Althof, W., and Berkowitz, M. W. (2006). Moral education and character education: their relationship and roles in citizenship education. J. Moral Educ. 35, 495–518. doi: 10.1080/03057240601012204

Ambang, T. (2007). Re-definising the role of tribal leadership in the contemporary government systems of Papua New Guniea. Contemp. PNG Stud. DWU Res. J. 7, 87–100.

Arif, M., Dorloh, S., and Abdullah, S. (2024). A systematic literature review of Islamic boarding school (Pesantren) education in Indonesia (2014-2024). Tribakti 35, 161–180. doi: 10.33367/tribakti.v35i2.5330

Asfina, R., and Ovilia, R. (2017). Be proud of Indonesian cultural heritage richness and be alert of its preservation efforts in the global world. Humanus 15:195. doi: 10.24036/jh.v15i2.6428

Behaghel, L., de Chaisemartin, C., and Gurgand, M. (2017). Ready for boarding? The effects of a boarding school for disadvantaged students. Am. Econ. J. Appl. Econ. 9, 140–164. doi: 10.1257/app.20150090

Berges Puyo, J. G. (2020). A value and character educational model: repercussions for students, teachers, and families. J. Cult. Values Educ. doi: 10.46303/jcve.2020.7

Berkowitz, R., and Ben-Artzi, E. (2024). The contribution of school climate, socioeconomic status, ethnocultural affiliation, and school level to language arts scores: a multilevel moderated mediation model. J. Sch. Psychol. 104:101281. doi: 10.1016/j.jsp.2024.101281

Birquier, A., Krabi, š., Juber, C., Shegalan, M., and Bond, F. Z. (1998) in Family history: The impact of modernization. eds. S. R. Yuan, J. Y. Shao, K. F. Zhao, and F. B. Dong (Beijing: SDX Joint Publishing Company), 664–665.

Bourke, L., Humphreys, J. S., Wakerman, J., and Taylor, J. (2012). Understanding rural and remote health: a framework for analysis in Australia. Health Place 18, 496–503. doi: 10.1016/j.healthplace.2012.02.009

Brestovanský, M. (2024). Key annual conferences focused on character education in 2023. Dialog. Educ. 2024, 1–6. doi: 10.31262/2989-3577/2024/1/6

Chambers, C. R., Ihuka, V. C., and Crumb, L. (2024). Rural cultural wealth in African education. Int. Educ. Res. 7:p1. doi: 10.30560/ier.v7n1p1

Chan, C. W. (2020). Moral education in Hong Kong kindergartens: an analysis of the preschool curriculum guides. Glob. Stud. Child. 10, 156–169. doi: 10.1177/2043610619885385

Charmaz, K., and Thornberg, R. (2021). The pursuit of quality in grounded theory. Qual. Res. Psychol. 18, 305–327. doi: 10.1080/14780887.2020.1780357

Chatzipanteli, A., and Adamakis, M. (2022). Social interaction throughs play activities and games in early childhood, Handbook of Research on Using Motor Games in Teaching and Learning Strategy, IGI-Global. 80–99.

Corbin, J., and Strauss, A. (2014). Basics of qualitative research: Techniques and procedures for developing grounded theory, 4th edition. Thousand Oaks, California, USA: Sage publications.

Creswell, J. W., and Creswell, D. J. (2018). Research design: Qualitative, quantitative, and mixed methods approach. 5th Edn. United Kingdom: SAGE Publications India Pvt. Ltd.

Curto, V. E., and Fryer, R. G. (2014). The potential of urban boarding schools for the poor: evidence from SEED. J. Labor Econ. 32, 65–93. doi: 10.1086/671798

Dewi, R. (2024). The paradox of Papuan recognition after two decades of special autonomy: Rracism, violence, and self-determination. ASEAS Adv. Southeast Asian Stud. 17, 25–44. doi: 10.14764/10.ASEAS-0105

du Plessis, P. (2014). Problems and complexities in rural schools: challenges of education and social development. Mediterr. J. Soc. Sci. doi: 10.5901/mjss.2014.v5n20p1109

Dvali, N. (2024). Education of will and character in elementary school. Enadakultura. doi: 10.52340/lac.2024.09.14

Eccles, J. S., and Barber, B. L. (1999). Student council, volunteering, basketball, or marching band: what kind of extracurricular involvement matters? J. Adolesc. Res. 14:10. doi: 10.1177/0743558499141003

Faizin, A. (2019). Internalization of character values in Pesantren school: efforts of quality enhancement. Advances in Social Science, Education and Humanities Research, Proceedings of the 3rd International Conference on Education Innovation (ICEI 2019). 387, 132–146. doi: 10.2991/icei-19.2019.34

Fithriyah, N. N., Mukmin, D., Dimas’udah, H. R., A’yun, D.N. A. Q., and Kurnilasari, A. R. U. (2023). Islamic boarding school education (indigenous and decolonization). Proceeding International Seminar on Islamic Education and Peace. Malang, Indonesia: Universitas Islam Raden Rahmat, 3, 77–87.

Foliano, F., Green, F., and Sartarelli, M. (2019). Away from home, better at school. The case of a British boarding school. Econ. Educ. Rev. 73:101911. doi: 10.1016/j.econedurev.2019.101911

Frye, M., Lee, A. R., LeGette, H., Mitchell, M., Turner, G., and Vincent, P. F. (Eds.) (2002). North Carolina Character Education Informational Handbook and Guide. Retrieved Desember 20, 2024, from http://www.ncpublicschools.org/charactereducation.

Gangloff, Darryl. (2024). Seven benefits of boarding school. Available online at: https://www.hotchkiss.org/benefits-of-boarding-school (Accessed November 17, 2024).

Gee, J. P. (2003). What video games must teach us about learning and literacy? Comput. Entertain. 1:20. doi: 10.1145/950566.950595

Guo, G., and Chen, Y. (2023). Lack of family education in boarding primary schools in China’s minority areas: a case study of stone moon primary school, Nujiang Lisu autonomous prefecture. Front. Psychol. 13:985777. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2022.985777

Hamedinasab, S., Ayati, M., and Rostaminejad, M. (2023). Teacher professional development pattern in virtual social networks: a grounded theory approach. Teach. Teach. Educ. 132:104211. doi: 10.1016/j.tate.2023.104211

Handayani, R., Narimo, S., Fuadi, D., Minsih, M., and Widyasari, C. (2023). Preserving local cultural values in forming the character of patriotism in elementary school students in Wonogiri regency. J. Innov. Educ. Cult. Res. 4, 56–64. doi: 10.46843/jiecr.v4i1.450

Hasibuan, S. N. (2022). Special autonomy in Papua and West Papua: an overview of key issues. Bestuurskunde 2, 145–158. doi: 10.53013/bestuurskunde.2.2.145-158

Hastasari, C., Setiawan, B., and Aw, S. (2022). Students’ communication patterns of islamic boarding schools: the case of students in Muallimin Muhammadiyah Yogyakarta. Heliyon 8:e08824. doi: 10.1016/j.heliyon.2022.e08824

Hermino, A., and Arifin, I. (2020). Contextual character education for students in the senior high school. Eur. J. Educ. Res. 9, 1009–1023. doi: 10.12973/eu-jer.9.3.1009

Hilmi, I., Nugraha, A., Imaddudin, A., Kartadinata, S., LN, S. Y., and Muqodas, I. (2020). Spiritual well-being among student in Muhammadiyah Islamic boarding school in Tasikmalaya. Proceedings of the 4th International Conference on Learning Innovation and Quality Education, (The 4th ICLIQE 2020 ), Surakarta, Central Java, Indonesia, 1–5. doi: 10.1145/3452144.3452200

Hoge, J. D. (2002). Character education, citizenship education, and the social studies. Soc. Stud. 93, 103–108. doi: 10.1080/00377990209599891

Hooper, L. (1940). Child participation in community activities. Child. Educ. 16, 355–358. doi: 10.1080/00094056.1940.10724478

Huda, S. A. A., and Mujahadah, A. S. (2021). Multicultural based character education at the Tebuireng Jombang Islamic boarding school. Schoolar 1, 208–212.

Ismail, F. (2023). The dynamics of conflict resolution and the potential for disintegration in West Papua in the context of the unity of the Republic of Indonesia: an analysis of conflict and disintegration in the Papua region. Pasundan Soc. Sci. Dev. 4, 1–7. doi: 10.56457/pascidev.v4i1.74

Iulia, H. R. (2015). The importance of the personal development activities in school. Procedia. Soc. Behav. Sci. 209, 558–564. doi: 10.1016/j.sbspro.2015.11.287

Jerome, L., and Kisby, B. (2019). The rise of character education in Britain: Heroes, dragons and the myths of character. London: Palgrave Pivot Cham. doi: 10.1007/978-3-030-27761-1

Kahane, R. (1988). Multicode organizations: a conceptual framework for the analysis of boarding schools. Sociol. Educ. 61, 211–226. doi: 10.2307/2112440

Karon, A. J., Cronin, A. A., Cronk, R., and Hendrawan, R. (2017). Improving water, sanitation, and hygiene in schools in Indonesia: a cross-sectional assessment on sustaining infrastructural and behavioral interventions. Int. J. Hyg. Environ. Health 220, 539–550. doi: 10.1016/j.ijheh.2017.02.001

Karyadi, A. C., and Khasanah, U. (2020). Bakar Batu culture as a reflection of Pancasila ideology at early childhood education. Utop. Praxis Latinoam. 25, 442–453. doi: 10.5281/zenodo.3987659

Katanski, A. V. (2005). Learning to write “Indian”: The boarding-school experience and American Indian literature. Norman: University of Oklahoma Press.

Kayange, G. M. (2023). Character education crisis in modern Africa. Ubuntu virtue theory and moral character formation. 1st Edn. Oxon & New York, NY: Routledge.

Kebede, M., Maselli, A., Taylor, K., and Frankenberg, E. (2021). Ethnoracial diversity and segregation in U.S. rural school districts. Rural. Sociol. 86, 494–522. doi: 10.1111/ruso.12398

Keliat, A., Warsono, H., and Kismartini, K. (2021). Response of people in tanah Papua in assessing special autonomy as a challenge and achievement. J. Adm. Publik Public Adm. J. 11, 54–68. doi: 10.31289/jap.v11i1.4642

Kim, D. (2023). The basis of character education programs in future education. J. Ethics Educ. Stud. 70, 65–87. doi: 10.18850/JEES.2023.70.03

Li, J. (2022). Grounded theory-based model of the influence of digital communication on handicraft intangible cultural heritage. Herit. Sci. 10:126. doi: 10.1186/s40494-022-00760-z

Li, L., Liu, H., Kang, Y., Shi, Y., and Zhao, Z. (2024). The influence of parental involvement on students’ non-cognitive abilities in rural ethnic regions of Northwest China. Stud. Educ. Eval. 81:101344. doi: 10.1016/j.stueduc.2024.101344

Lickona, T. (2015). Educating for character; mendidik untuk membentuk karakter. PT Bumi Aksara: Jakarta.

Lickona, T., Schaps, E., and Lewis, C. (2002). Eleven principles of effective character education. Washington, DC: Character Education Partnership.

Liu, F. (2004). Basic education in China’s rural areas: a legal obligation or an individual choice? Int. J. Educ. Dev. 24, 5–21. doi: 10.1016/j.ijedudev.2003.09.001

Liu, M., and Villa, K. M. (2020). Solution or isolation: is boarding school a good solution for left-behind children in rural China? China Econ. Rev. 61:101456. doi: 10.1016/j.chieco.2020.101456

Lomawaima, K. T., and Whitt, S. (2023). “Indigenous boarding school experiences” in Anthropology (Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press).

Lukman, S., Tahir, M. I., and Muhi, A. H. (2022). Implications of culture values and character of local wisdom in the implementation of local government. J. Posit. Sch. Psychol. 6, 11315–11332.

Madhakomala, R., Hakim, M. A., and Syifauzzuhrah, N. (2022). Problems of education in Indonesia and alternative solutions. Int. J. Bus. Law Educ. 3, 135–144. doi: 10.56442/ijble.v3i3.64

Mailin, F., Amiruddin, M. A. D., and AbdurrahmanAchyar, Z. (2023). Exploring intercultural communication in Indonesia: cultural values, challenges, and strategies. J. Namib. Stud. 33, 2804–2816. doi: 10.59670/jns.v33i.657

Marasinghe, S. A., Sun, Y., Norbäck, D., Adikari, A. M. P., and Mlambo, J. (2024). Indoor environment in Sri Lankan university dormitories: associations with ocular, nasal, throat and dermal symptoms, headache, and fatigue among students. Build. Environ. 251:111194. doi: 10.1016/j.buildenv.2024.111194

Martin, A. J., Burns, E. C., Kennett, R., Pearson, J., and Munro-Smith, V. (2021). Boarding and d school students: a large-scale multilevel investigation of academic outcomes among students and classrooms. Front. Psychol. 11:608949. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2020.608949

Martin, A. J., Papworth, B., Ginns, P., and Liem, G. A. D. (2014). Boarding school, academic motivation and engagement, and psychological well-being. Am. Educ. Res. J. 51, 1007–1049. doi: 10.3102/0002831214532164

Marzuki, (2024). The effect of dormitory-based coaching and religiosity on Islamic education learning outcomes. Educ. J. Educ. Learn. 1, 116–129. doi: 10.61987/educazione.v1i2.498

Mathias, M., and Mubofu, C. (2022). Extracurricular activities in the broader personal development: reflections from youth in public secondary schools. Res. Amb. 6, 01–05. doi: 10.53724/ambition/v6n4.02

Miller, J. P. (2000). Education and the soul: Toward a spiritual curriculum. Albany: State University of New Work Press.

Muawalin, M., Kirom, A., and Saifulah, S. (2023). The role of boarding schools in forming the character of students (dormitory o pondok ngalah Pasuruan Islamic boarding school). J. Pendidik. Indones. 2, 15–20. doi: 10.58471/ju-pendi.v2i01.172

Naibaho, F. R. (2023). The most fundamental education conflict in Indonesia: a systematic literature review. IJIET 7, 100–113. doi: 10.24071/ijiet.v7i1.4981

Nielsen, M. (2015). Baseline study for rural and remote education initiative for Papuan provinces. Papua: Myriad Research.

Pangalila, T., Sumilat, J. M., and Sobon, K. (2021a). Analysis of civic education learning in the effort to internalize the local wisdom of North Sulawesi. Tech. Soc. Sci. J. 26, 326–337. doi: 10.47577/tssj.v26i1.5158

Pangalila, T., Sumilat, J. M., and Sobon, K. (2021b). Learning civic education based on local culture of North Sulawesi society. J. Int. Conf. Proceed. 4, 559–569. doi: 10.32535/jicp.v4i3.1359

Perdana, N. S. (2015). Character education model based on education in Islamic boarding school. Edutech 14:402. doi: 10.17509/edutech.v14i3.1387

Petrus, T., and Rahanra, R. M. (2022). Papua people and its culture. Lakhomi J. Scient. J. Cult. 3, 89–99. doi: 10.33258/lakhomi.v3i3.742

Prasetio, A., Anggadwita, G., and Pasaribu, R. D. (2021). Digital learning challenge in Indonesia. IT Development Digital Skills Competences Education, 56–71. doi: 10.4018/978-1-7998-4972-8.ch004

Putra, I. E., Putera, V. S., Rumkabu, E., Jayanti, R., Fathoni, A. R., and Caroline, D. J. (2024). “I am Indonesian, am I?”: Papuans’ psychological and identity dynamics about Indonesia. Int. J. Intercult. Relat. 99:101935. doi: 10.1016/j.ijintrel.2024.101935

Ravet, J., and Mtika, P. (2024). Educational inclusion in resource-constrained contexts: a study of rural primary schools in Cambodia. Int. J. Incl. Educ. 28, 16–37. doi: 10.1080/13603116.2021.1916104

Riski, Y. T., Huda, M. N., Coralde, M. J. C., and Andajani, S. J. (2023). Descriptive study: implementation of character education in the dormitory of the Indonesian school of Davao, Philippines. Metod. Didakt. 18, 65–74. doi: 10.17509/md.v18i2.50236

Roberts, P., and Green, B. (2013). Researching rural places. Qual. Inq. 19, 765–774. doi: 10.1177/1077800413503795

Rokhman, F., Hum, M., and Syaifudin, A. (2014). Character education for golden generation 2045 (national character building for Indonesian golden years). Procedia. Soc. Behav. Sci. 141, 1161–1165. doi: 10.1016/j.sbspro.2014.05.197

Sanra, M. M., Hidayat, E. R., Bambang, W., and Widodo, P. (2023). Papua conflict resolution in contemporary counter-insurgency perspective using mystic diamond. Int. J. Human. Educ. Soc. Sci. 3, 891–896. doi: 10.55227/ijhess.v3i2.711

Scott, C., and Tebay, N. (2005). The West Papua conflict and its consequences for the island of New Guinea: root causes and the campaign for Papua, land of peace. Round Table. 94, 599–612. doi: 10.1080/00358530500331826

Singh, B. (2019). Character education in the 21st century. J. Soc. Stud. 15, 1–12. doi: 10.21831/jss.v15i1.25226

Sismanto, (2023). Digital transformation of character education model and its implementation for diverse students in education technology in the new normal: Now and beyond. 1st Edn. London: Routledge.

Siti Kamilah Suwarna, A. Y., Adh Dhuha, Z. U., Aimar, D., Saputra, D. A., Maulana Rifki, M. T., Nurfaidah, T., et al. (2024). The role of physical education in forming students’ character education (systematic literature review). J. Ilm. Mandala Educ. 10:110. doi: 10.58258/jime.v10i1.6538

Sopaheluwakan, W. R. I., Fatem, S. M., Kutanegara, P. M., and Maryudi, A. (2023). Two-decade decentralization and recognition of customary forest rights: cases from special autonomy policy in West Papua, Indonesia. Forest Policy Econ. 151:102951. doi: 10.1016/j.forpol.2023.102951

Stone, A. (2023). “Rural student experiences in higher education” in Research, Handbook on the student experience in higher education. Cheltenham, UK: Edward Elgar Publishing, 494–505.

Suhendar, F. A., Sari, R. V., Pangesti, T., Putra, Z. M. G., and Santoso, A. P. A. (2024). The impact of poverty in Indonesia on education. JISIP 8:1119. doi: 10.58258/jisip.v8i2.6682

Sulasmono, P. (2017). The integration of local cultural wisdom values in building the character education of students. Int. J. Educ. Res. 5, 151–162.

The Association of Boarding Schools (TABS) (2013). The truth about boarding school. Asheville NC: The Association of Boarding Schools.

Tomaševski, K. (2001). “Human rights obligations: making education available, accessible, acceptable and adaptable” in SIDA (Swedish international development agency) (Novum Grafiska AB: Gothenburg), 1–47.

Trafzer, E., Clifford,, Keller, J. A., and Sisquo, L. (2006). Boarding school blues: Revisiting american indian educational experiences. Lincoln and London: University of Nebraska Press.

UNICEF. (2016). Annual report Cambodia. Available online at: https://www.unicef.org/ about/annualreport/files/Cambodia_2016_COAR.pdf (Accessed November 27, 2019).

Viartasiwi, N. (2013). Holding on a thin rope: Muslim Papuan communities as the agent of peace in Papua conflict. Procedia Environ. Sci. 17, 860–869. doi: 10.1016/j.proenv.2013.02.104

Vicinus, M. (1984). Distance and desire: english boarding-school friendships. Signs 9, 600–622. doi: 10.1086/494089

Wahudin, D., Sumule, A., and Suwirta, A. (2021). Alternatives of genuine basic education program in Papua provinces, Indonesia. Tawarikh J. Hist. Stud. 12, 219–240. doi: 10.2121/tawarikh.v12i2.1439

Wallin, D. C., and Reimer, L. (2008). Educational priorities and capacity: a rural perspective. Can. J. Educ. 31, 591–613.

White, M. A. (2004). An Australian co-educational boarding school: a sociological study of Anglo-Australian and overseas students’ attitudes from their own memoirs. Int. Educ. J. 5, 65–78.

Yampap, U., &. Haryanto, H (2023). The value of local wisdom in the burning stone tradition through learning for character building of elementary school students. KnE Social Sci. doi: 10.18502/kss.v8i8.13301

Yao, J. (2022). Discussion on the psychological characteristics and psychological education strategies of higher vocational students. Shanxi Youth 17, 196–198.

Yao, S., and Gao, L. Y. (2018). Can large scale construction of boarding schools promote the development of students in rural area better? J. Educ. Econ. 34, 53–60.

Yaxuan, Q. (2023). Thoughts on aesthetic character in music education. J. Res. Vocat. Educ. 5. doi: 10.53469/jrve.2023.05(06).10

Yulia, R., Henita, N., Gustiawan, R., and Erita, Y. (2022). Efforts to strengthen character education for elementary school students by utilizing digital literacy in era 4.0. J. Digit. Learn. Dist. Educ. 1, 240–249. doi: 10.56778/jdlde.v1i6.39

Zhang, Y. (2020). Solution or isolation: is international boarding school a good solution for Chinese elites who aim to study abroad? J. Int. Educ. Dev. 4, 101–103. doi: 10.47297/wspiedWSP2516-250014.20200408

Zhang, X., and Tan, X. (2023). Research on the influencing factors and countermeasures of the formation of “clique” in college students’ dormitory based on binary logistic analysis, 1015–1021. doi: 10.2991/978-94-6463-064-0_105

Zhao, M., and Liu, G. (2022). Research on the practical path of cultural education in university dormitories from the perspective of "three complete education". University Logistics Research 9, 48–50.

Zhong, Z., Feng, Y., and Xu, Y. (2024). The impact of boarding school on student development in primary and secondary schools: a meta-analysis. Front. Psychol. 15. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2024.1359626

Keywords: boarding school, character education, local wisdom, inland students, personal development

Citation: Sobon K, Herwin, Ohoitimur J, Sartono EKE and Murdiono M (2025) Character building through boarding school for inland and outermost student: a grounded theory approach. Front. Educ. 10:1575177. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2025.1575177

Edited by:

Sarfraz Aslam, UNITAR International University, MalaysiaReviewed by:

Gül Kadan, Cankiri Karatekin University, TürkiyeFarah Chalida Hanoum, Universitas PGRI Semarang, Indonesia

Copyright © 2025 Sobon, Herwin, Ohoitimur, Sartono and Murdiono. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Kosmas Sobon, a29zbWFzc29ib24uMjAyM0BzdHVkZW50LnVueS5hYy5pZA==

Kosmas Sobon

Kosmas Sobon Herwin1

Herwin1