- Department of Languages and Literatures, University of Gothenburg, Gothenburg, Sweden

This paper presents a learning activity intended to increase preservice (or inservice) teachers’ skills in giving feedback to students by comparing and discussing teacher feedback and generative AI (GenAI)-powered feedback. In current times, feedback is seen as a dialogue, a two-way relation striving to engage learners in the feedback process, and the way feedback is phrased is considered essential for students to interpret and act on. Teachers often struggle with questions of how much feedback to give, what to give feedback on, and how to phrase it. For inexperienced teachers, the feedback process is particularly challenging, making practice essential. The recent fast-paced development of GenAI tools is transforming the field of L2 writing and feedback practice. Although a multitude of automated writing evaluation systems offer both instant and extensive feedback to students, it is far from evident how they can or should be used in the language classroom. For novice and preservice teachers, who are often cautious in giving corrective feedback, GenAI tools present additional challenges. The activity outlined in this paper provides these teachers with guided practice in giving feedback and enables them to compare their feedback against GenAI-powered feedback on authentic learner text. Classroom discussion on responsible use of AI feedback to promote learning is central to this process. Although designed for the (English) language classroom, the exercise can easily be adapted to other disciplines.

1 Introduction

Providing feedback to students is a complex and challenging task and forms the core of every teacher’s work. Feedback literacy is, hence, an important aspect of the teaching profession (Bitchener and Ferris, 2012; Carless and Winstone, 2023; Lee and Mao, 2024). Today, a teacher should not only provide high-quality feedback to students but also be able to navigate modern pedagogical technologies, such as generative AI (GenAI) tools, which can be used for this purpose. Even though such tools have various advantages, for example, they help save time spent on writing feedback, their use can be fairly challenging due to the need for a high degree of AI and feedback literacy to ensure responsible and effective use (Jacobsen and Weber, 2025; Hawkins et al., 2025; Henderson et al., 2025). Therefore, it is essential that future teachers are trained in feedback literacy (Buck et al., 2010; Kartchava, 2021; Kong et al., 2022; Ropohl and Rönnebeck, 2019) and use of GenAI tools to ensure they help their students understand and effectively use the given feedback (Hawkins et al., 2025). The integration of feedback and AI skills in education is also strongly emphasized by the United Nations Educational Scientific and Cultural Organization (2024).

The activity presented in this paper offers guided practice based on an authentic sample learner text. It aims to support preservice (or inservice) teachers’ feedback literacy by critically engaging with teacher feedback and AI-powered feedback.

2 Intended course

Preservice (English) teachers are the prime target group for the activity, i.e., students studying to become teachers, but it may include novice as well as more experienced inservice teachers intending to develop their competence. Teachers training students in the second or third term are an ideal group because, in addition to solid subject knowledge (in this case, English), the activity requires some previous knowledge of second/foreign language acquisition theory. However, having knowledge of feedback theory is an advantage, but not a necessity. The class size can vary, but it should be large enough to generate fruitful classroom discussions and group discussions of 3–5 students. In previous iterations, the activity was carried out in a class of approximately 30 students. The activity involves independent and group work, as well as in-class discussions. It is designed for an in-class, face-to-face format, but with some adaptation, it can be conducted on an online platform such as Zoom. The activity includes three 90-min sessions and independent student work between sessions. The cross-disciplinary relevance of the activity is high. It has been designed for and executed in groups of future English teachers, but can be easily adapted to any school subject at any level.

3 Intended learning outcomes

The overall aim of the activity is to increase preservice teachers’ feedback literacy in preparation for their future work. More specifically, upon successful completion of the activities, the target group should be able to:

• give feedback on learners’ texts based on a basic model of feedback strategies;

• explore GenAI feedback tools and increase understanding of how such tools can be used in their future activities to support teaching and learning;

• discuss differences and similarities, and advantages and disadvantages of teacher feedback and GenAI feedback in relation to relevant factors; and

• critically evaluate GenAI feedback to be able to make informed decisions about when and how to use teacher vs. GenAI feedback.

4 Theoretical orientation

Feedback is an important pedagogical tool in the language classroom (Bitchener and Ferris, 2012; Hyland and Hyland, 2019a). In addition to helping learners “build awareness, knowledge, and strategic competence” (Bitchener and Ferris, 2012, p. 140) in writing and in language use more generally (Hyland and Hyland, 2019a), effective feedback also helps establish a two-way relationship between the teacher and the student, creating opportunities for learning (Hyland and Hyland, 2019b). Many factors in the context of teaching and learning shape feedback practices, making the provision of feedback challenging while it, hopefully, leads to learning.

Developing feedback literacy is a long-term process that needs practice (Ropohl and Rönnebeck, 2019). Previous studies in the field of English as a second/foreign language and teacher education (Guénette and Lyster, 2013; Kartchava, 2021; Kartchava et al., 2020; Kong et al., 2022), and my own experience of teaching future English teacher’s highlight that preservice teachers are often cautious about giving feedback.1 They often prefer to focus on positive aspects of a performance and are afraid of providing corrective feedback. They are concerned that giving too much or too complex feedback could overwhelm learners, making it harder for them to understand and use it effectively. They are also afraid of coming across as too harsh in their phrasing of the feedback and fear demotivating students. These aspects are also relevant for AI-powered feedback, and a teacher needs to evaluate the feedback provided by an AI tool, to ensure it is suitable, relevant, and unbiased. Studies have also shown that preservice teachers and inexperienced teachers tend to use a more limited range of feedback strategies than more experienced teachers (Jacobsen and Weber, 2025; Junqueira and Kim, 2013). Therefore, repeated structured training, based on a solid theoretical foundation, in providing feedback, is a necessary component of teacher education.

Writing feedback is often time-consuming, and time constraints and large classes are among the major factors negatively influencing teachers’ feedback practices (Lee and Mao, 2024; Ryan et al., 2019). As AI technology is currently transforming the field of education, GenAI feedback tools have emerged as a powerful means to provide instant and generous feedback and may help alleviate teachers’ workload in this aspect (Guo and Wang, 2024). GenAI tools can provide a large volume of high-quality feedback (Jacobsen and Weber, 2025), and studies have reported several positive effects of GenAI feedback on students’ writing. For example, it encourages reflection on feedback and writing strategies (Hawkins et al., 2025) and text revision (Shadiev and Feng, 2024) and improves language accuracy and the noticing of mistakes (Barrot, 2023). However, students do not always trust AI-provided feedback and prefer teacher feedback (Henderson et al., 2025).

However, important drawbacks and risks warrant careful scaffolding and evaluation when using GenAI tools. The success of automated feedback is largely dependent on the quality of prompts, i.e., the instructions provided to the software on what it should do. More specifically, high-quality feedback output “is dependent on the context, mission, specificity, and clarity of the prompts provided” (Jacobsen and Weber, 2025, p. 12). In this activity, students are encouraged to elaborate using different prompts and fine-tune them over several iterations. Other risks are hallucinations (i.e., fabricated data) and biases (Jacobsen and Weber, 2025), as well as inaccuracies, such as marking correct grammar as incorrect (Shadiev and Feng, 2024). To identify and navigate these pitfalls and avoid overreliance on AI output, students need guidance in critical evaluation of the output and solid discipline-specific knowledge to apply GenAI feedback.

The activity presented here engages students in using a variety of feedback strategies, offers practice with GenAI tools, including formulating effective prompts, and supports a critical analysis of students’ own feedback choices compared to those of the AI tool. The activity draws on well-established frameworks for feedback and feedback theory (Brookhart, 2017; Ellis, 2009; Ferris, 1997; Sheen, 2011). The first step of the activity is to consider some key features (see a–c below) of the feedback message. These are outlined in detail in Appendix 1, along with an illustration of feedback on the sample learner text. For teachers wanting a more comprehensive overview and guide to feedback, including numerous examples, the book How to Give Effective Feedback to Your Students (Brookhart, 2017) may be a useful resource. Three central areas of feedback are:

a) feedback content, i.e., amount, focus, valence, specificity, function, and tone;

b) whether to correct errors or only give some kind of indication of error occurrence; and

c) how to phrase feedback, e.g., ask for clarification, give information, make a request, use a hedge, and/or make a generic or text-specific comment.

Session 1 should cover the introduction to feedback and then introduce the activity (Implementation section). These key features will serve as a guide for providing feedback on the sample learner text and form the basis for the comparison between the teacher and the AI feedback.

5 Implementation

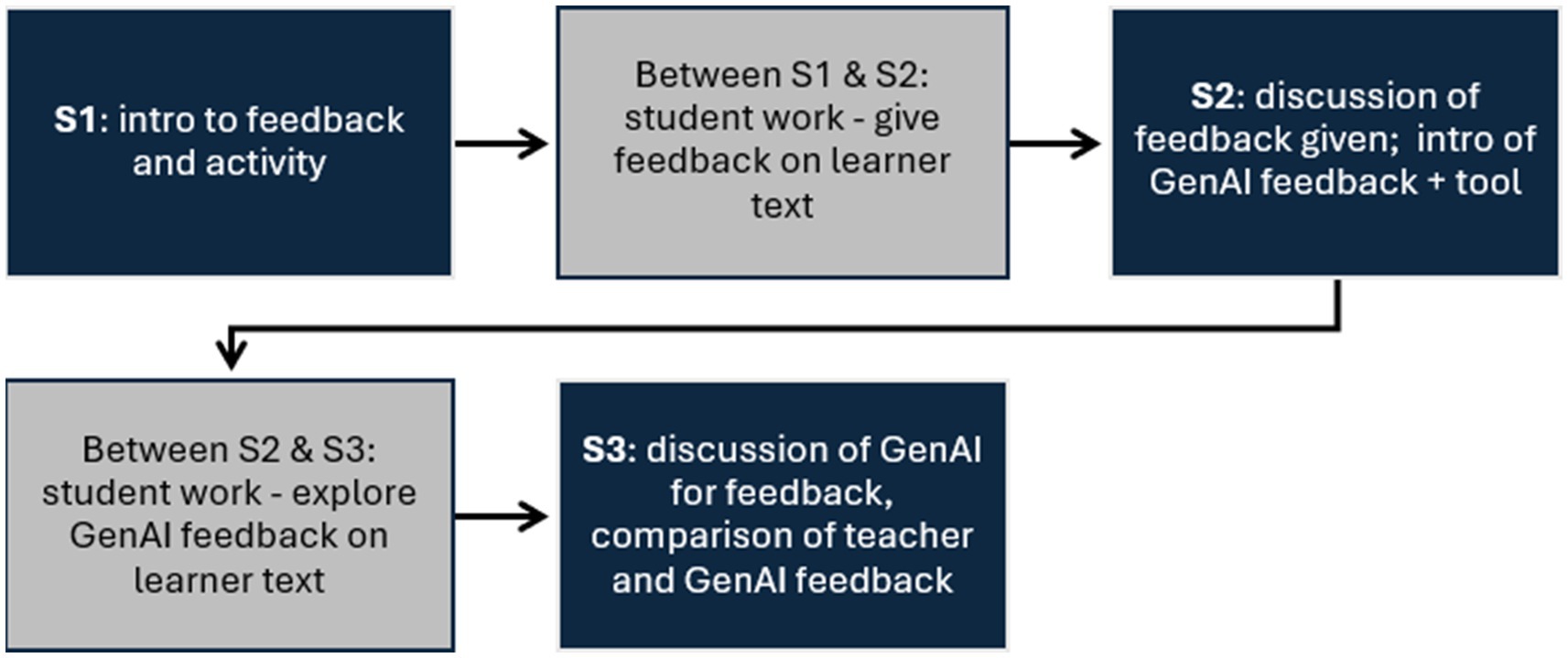

As illustrated in Figure 1, the activity is designed for three 90-min class meetings and independent work between sessions.

In session 1, the teacher introduces the concept of feedback, feedback theory, and the activity. Session 2 focuses on the discussion of teacher feedback, while session 3 focuses on AI-generated feedback and the comparison between teacher feedback and GenAI feedback. In this section, the three sessions and students’ independent work between sessions are described in detail. Appendix 1 outlines key features of feedback provision, Appendix 2 contains a sample learner text and worksheets, and Appendix 3 gives an example of GenAI feedback on a different sample text.

5.1 Session 1: introducing to feedback and the activity

After presenting the overall theme—feedback—the teacher begins the session by asking the students about their past experience of feedback (as students and in their school placements/practicums, if any) and beliefs related to feedback, e.g., what is important, difficult, and good to remember. This encourages students from the beginning to reflect on feedback and triggers in-class discussion. After this brief brainstorming, the teacher introduces the activity and its learning objectives—approximate time frame: 30 min.

The initial discussion is likely to spark ideas of some of the key aspects of feedback, which makes a convenient starting point for feedback theory and a more in-depth presentation of its key features (Appendix 1)—approximate time frame: 40 min.

Finally, the teacher repeats the task instructions and explains what the students need to do in preparation for the next class. In relation to this, it may also be relevant to consult the curricula and/or syllabi to be used. Approximate time frame: 20 min.

5.2 Between class sessions 1 and 2: giving feedback on learner text

After session 1, students will work on their own, preferably individually. Based on the feedback strategies and considerations discussed in session 1, the students will provide feedback on the sample learner text (or any other text the teacher chooses) and reflect on their feedback choices. The worksheet exercise 1 in Appendix 2 should be used as an aid for analyses and critical reflections. The students should bring all their materials to session 2.

5.3 Session 2: discussing feedback on learner text and introducing GenAI tools

In the first part of this session, students will team up in groups of 3–4 members to compare the work conducted between sessions. They should discuss the feedback choices made, e.g., the volume of feedback they gave, what areas they targeted in the feedback, and how they phrased feedback—approximate time frame: 30 min.

Next, each group briefly reports back orally on their analyses, and the teacher leads the discussion, summarizing reflections and connecting to feedback strategy models—approximate time frame: 30 min.

Finally, the teacher introduces GenAI tools for feedback by first asking the students about their experience in using an automated writing evaluation tool for feedback, followed by showing how ChatGPT can provide feedback on a text. An example with text, prompt, and feedback is provided in Appendix 3, but any text containing some language/writing issues can be used for this demonstration. The teacher should show results with a few different prompts to illustrate the significance of careful prompt formulation. For example, we may want ChatGPT’s feedback on only the strong features of the text, or on major grammatical problems. This site may be a useful starting point for prompt writing: https://help.openai.com/en/articles/10032626-prompt-engineering-best-practices-for-chatgpt. Approximate time frame: 30 min.

After session 2, the student should be able to:

• apply different feedback types and feedback strategies to support learners’ language development;

• compare and critically evaluate different types of feedback in relation to language learning and language instruction; and

• justify their choices of feedback strategies based on learners’ assumed knowledge and proficiency levels.

5.4 Between sessions 2 and 3: exploring AI-powered feedback

The next step is to use ChatGPT to generate feedback on the same text that students gave feedback on in exercise 1. This study can be conducted individually or in small groups, largely depending on the students’ knowledge of ChatGPT—inexperienced students preferred working in groups. Students should experiment with a few different prompts for generating feedback, analyze the feedback using the worksheet for exercise 2 (Appendix 2), and bring all reflections and materials to session 3.

5.5 Session 3: comparing and reflecting on teacher feedback vs. AI feedback

Based on the students’ analyses and the discussion questions in Appendix 2, the focus of this final session is a discussion of the feedback the students gave on the text and the GenAI-powered feedback on the same text. The session will consist of small-group discussions (approximately 45 min) followed by a full-group discussion (approximately 45 min) led by the teacher. Important parts of the discussion are the advantages and disadvantages of different modes and strategies, the effects of different prompts on GenAI feedback, and if/how teacher feedback and GenAI feedback can be combined.

After session 3, the students should be able to:

• analyze and critically reflect on feedback provided by a GenAI tool; and

• compare and critically evaluate different types of feedback modes and strategies in relation to language learning and language instruction.

6 Impact and implications

Feedback is a popular topic among preservice English teachers in our department. The fact that everyone has experience of receiving feedback (and some of them giving feedback) creates lively discussions about what is good vs. bad feedback. However, a more in-depth discussion, such as in this activity, is often an eye-opener to the complexity and challenges of feedback practices.

Regarding teacher feedback, students claim that they have developed a toolbox of concrete strategies and are better positioned than before to adapt to different assessment situations. Hands-on work and reflection are essential components, as evidenced by students’ end-of-class exit tickets on what they found valuable: “[t]o discuss the student texts, seeing everyone’s different feedback suggestions” and “[l]istening to everyone’s different thoughts and difficulties and learning that I’m not the only one finding this kind of hard.” Hence, students begin to see the complexity and challenges involved, and they also express strong concerns about giving feedback. Some have said: “I do not want to be mean, but still clear,” “[w]hat should I focus on? Must remember to give feedback on positive things,” “[I’m scared to] cause frustration,” and “[g]iving too strict or detailed feedback.” These are recurrent concerns clearly signaling the need for practice, while students also realize they will develop feedback skills over time.

For this student group, the need for GenAI tool practice was very clear. Among the 22 students responding to a questionnaire, 17 reported never having used a GenAI tool for obtaining feedback on a text, 4 reported having used it a few times, and 1 reported using it very often. When asked if they had seen a GenAI tool being used for feedback purposes in their school placement/practicum, 15 out of 20 respondents said “never” and 5 said “a few times” (2 students did not respond). Thus, this group’s experience with AI tools for feedback was limited, and therefore, more sessions on preparing and practicing AI use would have been useful.

Students’ comments after completing the activity reflect an increased awareness of feedback complexity and a fairly negative attitude toward using GenAI for feedback. While a few students were clearly positive toward using a GenAI (“I think it is a tool that could help me save time.”; “It was fairly easy to do.”), and a few were very strongly against using it (“I have no control over the feedback”; “I found comments that were incorrect, I would not use [a GenAI tool]”), the majority were hesitant toward using a GenAI tool. Comments include: “The ChatGPT feedback was very general, and I wouldn’t use it with students who make many mistakes.”; “There was a lot of feedback and I would be more selective in what I give feedback on.” “The feedback I gave was more specific and more personal than the AI feedback”; “I’m scared that the AI-feedback is too much.” Some commented explicitly on the need for critical evaluation: “If I have to check all the AI feedback, I could just give feedback myself.” Overall, students demonstrated knowledge of many factors influencing feedback practices, which is very promising, and their comments clearly signal a need for more practice in prompt engineering for GenAI tools for these purposes.

Several implications emerged from running the activity. First, students appreciated the variation in the activity, i.e., working on their own, in small groups, and in full-class sessions. The setup created time for reflection on feedback questions and for elaborating on the GenAI tool. Second, some students had minimal experience using GenAI for feedback, which makes guidance and prompt formulation practice necessary, and more time for this may be needed. Some of the hesitant responses may have been more positive with more prompt elaboration. Nevertheless, it was fulfilling to observe that the students, overall, did not simply accept the GenAI feedback as “true” and kept a critical stance about its accuracy and reliability. Last, an important question for in-class discussion is how to combine teacher feedback and GenAI feedback; very few students, if any, had clear ideas at this stage of how to actually use GenAI for feedback in the classroom.

7 Conclusion

The overall aim of the activity is to advance preservice (English) teachers’ feedback literacy using teacher feedback and GenAI feedback. The activity attempts to bridge a gap between theory and practice in this area, and helps students develop practical pedagogical knowledge to be applied in future teaching. Its design is clearly learner-centred, allowing students to discover the complexity of feedback and begin to see how GenAI tools may be useful. In addition, students often realized that feedback strategies are transferable to other school subjects, and the activity in itself has a high cross-disciplinary relevance.

Data availability statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/Supplementary material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Author contributions

A-LF: Writing – review & editing, Methodology, Writing – original draft, Conceptualization.

Funding

The author(s) declare that no financial support was received for the research and/or publication of this article.

Conflict of interest

The author declares that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The author(s) declare that Gen AI was used in the creation of this manuscript. Gen AI was used for generating feedback on the sample text in Appendix 3/Data sheet 3.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Supplementary material

The Supplementary material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/feduc.2025.1612398/full#supplementary-material

Footnotes

1. ^For studies on other disciplines, see for example Buck et al. (2010), Ropohl and Rönnebeck (2019), and Talanquer et al. (2015).

References

Barrot, J. S. (2023). Using automated written corrective feedback in the writing classrooms: effects on L2 writing accuracy. Comput. Assist. Lang. Learn. 36, 584–607. doi: 10.1080/09588221.2021.1936071

Bitchener, J., and Ferris, D. (2012). Written corrective feedback in second language acquisition and writing. New York: Routledge.

Brookhart, S. M. (2017). How to give effective feedback to your students. 2nd Edn. Alexandria: ASCD.

Buck, G. A., Trauth-Nare, A., and Kaftan, J. (2010). Making formative assessment discernable to pre-service teachers of science. J. Res. Sci. Teach. 47, 402–421. doi: 10.1002/tea.20344

Carless, D., and Winstone, N. (2023). Teacher feedback literacy and its interplay with student feedback literacy. Teach. High. Educ. 28, 150–163. doi: 10.1080/13562517.2020.1782372

Ellis, R. (2009). A typology of written corrective feedback types. ELT J. 63, 97–107. doi: 10.1093/elt/ccn023

Ferris, D. R. (1997). The influence of teacher commentary on student revision. TESOL Q. 31, 315–339. doi: 10.2307/3588049

Guénette, D., and Lyster, R. (2013). Written corrective feedback and its challenges for pre-service ESL teachers. Can. Mod. Lang. Rev. 69, 129–153. doi: 10.3138/cmlr.1346

Guo, K., and Wang, D. (2024). To resist it or to embrace it? Examining ChatGPT’s potential to support teacher feedback in EFL writing. Educ. Inf. Technol. 29, 8435–8463. doi: 10.1007/s10639-023-12146-0

Hawkins, B., Taylor-Griffiths, D., and Lodge, J. M. (2025). Exploring the effect of feedback literacy on AI-enhanced essay writing. Assess. Eval. High. Educ., 4, 1–13. doi: 10.1080/02602938.2025.2492070

Henderson, M., Bearman, M., Chung, J., Fawns, T., Buckingham Shum, S., Matthews, K. E., et al. (2025). Comparing generative AI and teacher feedback: student perceptions of usefulness and trustworthiness. Assess. Eval. High. Educ. 1–16, 1–16. doi: 10.1080/02602938.2025.2502582

Hyland, K., and Hyland, F. (2019a). “Contexts and issues in feedback on L2 writing” in Feedback in second language writing. Contexts and issues. eds. K. Hyland and F. Hyland. 2nd ed (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press), 1–22.

Hyland, K., and Hyland, F. (2019b). “Interpersonality and teacher-written feedback” in Feedback in second language writing. Contexts and issues. eds. K. Hyland and F. Hyland. 2nd ed (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press), 165–183.

Jacobsen, L. J., and Weber, K. E. (2025). The promises and pitfalls of large language models as feedback providers: a study of prompt engineering and the quality of AI-driven feedback. AI 6:35. doi: 10.3390/ai6020035

Junqueira, L., and Kim, Y. (2013). Exploring the relationship between training, beliefs, and teachers’ corrective feedback practices: a case study of a novice and an experienced ESL teacher. Can. Mod. Lang. Rev. 69, 181–206. doi: 10.3138/cmlr.1536

Kartchava, E. (2021). “The role of training in feedback provision and effectiveness” in The Cambridge handbook of corrective feedback in second language learning and teaching. eds. H. Nassaji and E. Kartchava (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press), 598–619.

Kartchava, E., Gatbonton, E., Ammar, A., and Trofimovich, P. (2020). Oral corrective feedback: pre-service English as a second language teachers’ beliefs and practices. Lang. Teach. Res. 24, 220–249. doi: 10.1177/1362168818787546

Kong, Y., Molnár, E. K., and Xu, N. (2022). Pre- and in-service teachers’ assessment and feedback in EFL writing: changes and challenges. SAGE Open 12, 1–15. doi: 10.1177/21582440221126672

Lee, I., and Mao, Z. (2024). Writing teacher feedback literacy: surveying second language teachers’ knowledge, values, and abilities. J. Second. Lang. Writ. 63:101094. doi: 10.1016/j.jslw.2024.101094

Ropohl, M., and Rönnebeck, S. (2019). Making learning effective - quantity and quality of pre-service teachers’ feedback. Int. J. Sci. Educ. 41, 2156–2176. doi: 10.1080/09500693.2019.1663452

Ryan, T., Henderson, M., and Phillips, M. (2019). Feedback modes matter: comparing student perceptions of digital and non-digital feedback modes in higher education. Br. J. Educ. Technol. 50, 1507–1523. doi: 10.1111/bjet.12749

Shadiev, R., and Feng, Y. (2024). Using automated corrective feedback tools in language learning: a review study. Interact. Learn. Environ. 32, 2538–2566. doi: 10.1080/10494820.2022.2153145

Sheen, Y. (2011). Corrective feedback, individual differences and second language learning, vol. 13. 1st Edn. Dordrecht: Springer.

Talanquer, V., Bolger, M., and Tomanek, D. (2015). Exploring prospective teachers’ assessment practices: noticing and interpreting student understanding in the assessment of written work. J. Res. Sci. Teach. 52, 585–609. doi: 10.1002/tea.21209

United Nations Educational Scientific and Cultural Organization. (2024). AI Competency Framework for Teachers. UNESCO. Available online at: https://unesdoc.unesco.org/ark:/48223/pf0000391104 (Accessed August 15, 2025)

Keywords: teacher education, pre-service teachers, generative AI feedback, automated feedback, teacher feedback, English teaching and learning, L2 writing

Citation: Fredriksson A-L (2025) GIFT-AI: “I’m scared that the AI feedback is too much!”—preservice (English) teachers’ feedback strategies and their use of GenAI for feedback. Front. Educ. 10:1612398. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2025.1612398

Edited by:

Kelly Merrill Jr, University of Cincinnati, United StatesReviewed by:

Veronika Solopova, Technical University of Berlin, GermanyIndah Indrawati, Madako Toli-Toli University, Indonesia

Copyright © 2025 Fredriksson. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Anna-Lena Fredriksson, YW5uYS1sZW5hLmZyZWRyaWtzc29uQHNwcmFrLmd1LnNl

Anna-Lena Fredriksson

Anna-Lena Fredriksson