- Department of English Studies, University of South Africa, Pretoria, South Africa

This qualitative study investigates the impact of Generative Artificial Intelligence in academia and explores strategies to empower critical thinking within the framework of Society 5.0, a human-centered vision of technological advancement that emphasizes the ethical integration of digital innovation and social wellbeing. As tools such as Gemini, ChatGPT 5.0, and BlackBox become increasingly embedded in research and writing practices, concerns have emerged that over-reliance on these technologies may limit critical analysis and original thought. Based on qualitative data from 16 students and one lecturer at a South African higher education institution, the study examines how GenAI influences critical thinking and cognitive presence in scholarly work. The findings reveal that GenAI can enhance critical thinking, metacognitive awareness, and cognitive presence when used reflectively and within pedagogical guidance. The study recommends the development of critical AI literacy to strengthen cognitive engagement and sustain originality to ensure that human creativity remains central to learning and scholarship in Society 5.0.

1 Introduction

Society 5.0 represents “…a sustainable, human-centric and resilient European industry,” (Breque et al., 2021, p. 3) and brings about a fundamental change in which technological innovation and human values converge. Within Society 5.0's human-centered focus, Generative AI (GenAI) now facilitates how students read, write, and reason in academia. Its benefits, linguistic scaffolding, access to models, and reduced cognitive load, are clear; yet uncritical use can blur authorship, narrow reflection, and weaken the very cognitive presence universities seek to build (Duah and McGivern, 2024; Wu et al., 2025). These tensions are amplified in South African open-distance contexts, where English-medium instruction (EMI), uneven connectivity, and the need for self-regulation redesigns everyday learning. Researchers know less about how GenAI actually influences critical thinking and cognitive presence in DE contexts, and how lecturers can cultivate responsible, reflective GenAI use rather than shortcut behaviors, even though GenAI use is common (Maphoto, 2024; Rejeb et al., 2025; Sevnarayan and Potter, 2024; Sevnarayan, 2024). This study addresses that gap by examining students' experiences with GenAI in an English module at a South African Distance Education (DE) university.

The Fifth Industrial Revolution (5IR) integrates human creativity, empathy, and sustainability with advanced technologies such as artificial intelligence (AI), robotics, and digital platforms (Denden et al., 2025; Shabur et al., 2025) unlike the Fourth Industrial Revolution (4IR), which emphasized automation, digitisation, and efficiency (Noble et al., 2022; Rejeb et al., 2025; Xu et al., 2021). In academia, this combination may result in the adaptation of current technologies and the preservation of cognitive, critical thinking, and AI literacy. Although both Society 5.0 and the 5IR describe the current human–technology model, this study adopts Society 5.0 as its overarching conceptual framework. The 5IR provides the broader industrial and technological backdrop that emphasizes human–machine collaboration, whereas Society 5.0 refines this vision into a human-centered societal model that prioritizes ethical innovation, inclusivity, and sustainability. Society 5.0 secures the analysis conceptually by focusing on how human creativity, critical thinking, and ethical awareness can coexist with GenAI in education, while references to the 5IR serve only to contextualize the technological change. This link ensures theoretical coherence and situates the study within a socially responsive interpretation of the human–AI relationship. As such GenAI tools such as ChatGPT 5.0, Gemini, and BlackBox exemplify this dual potential and challenge. These tools can enhance linguistic expression, support productivity, and improve access to scholarly resources (Bittle and El-Gayar, 2025; Denden et al., 2025; Kasneci et al., 2023; Nasr et al., 2025; Tlili et al., 2023), yet their widespread adoption raises concerns about erasing critical thinking. Cotton et al. (2023) and Maphoto et al. (2024) caution that convenience may promote surface-level engagement and reduce critical analysis and cognitive presence. Risks may be acute in distance and digital education, where independent engagement and self-regulation are central. Research in education and applied linguistics stresses critical learning, intellectual inquiry, and metacognitive awareness (Biggs et al., 2022; Garrison et al., 2000). However, over-reliance on AI-generated outputs can compromise reflection and originality. The challenge for academia in Society 5.0 is to balance GenAI's benefits with the integrity of intellectual inquiry. However, as Figure 1 below shows, Society 5.0 follows the information society and is conceived as a “super smart society” where digital and physical systems are tightly integrated. The study is framed within this trajectory and clarifies why academia must balance human creativity and cognitive presence with GenAI and LMS-integrated technology.

Figure 1. Society 5.0 timeline from hunting society to “super smart society” (Fukuyama, 2018, p. 49).

Maphoto (2024), Letseka et al. (2025), and Suliman et al. (2024) argue that within South African DEs, these debates are urgent. EMI creates barriers for many students working in a second or third language, compounded by DE, which usually demands self-regulated learning (SRL; Akintolu and Letseka, 2024; Maphoto, 2025), and by structural constraints such as unreliable internet, limited digital access, and load shedding (Akintolu et al., 2024; Maphoto et al., 2024; Mohale and Suliman, 2025). In this context, GenAI has potential but is contested: it can generate human-like articulation and integrate diverse perspectives to help overcome linguistic barriers and enhance collaboration (Van Dis et al., 2023). GenAI should serve as a supplement, not a substitute, for human interaction, critical reasoning, and mentorship (Bozkurt and Sharma, 2024). A balanced approach that combines technological support with authentic human engagement is central to effective pedagogy in digitally mediated contexts (Arowosegbe et al., 2024; Denden et al., 2025; Dwivedi et al., 2023; Holstein et al., 2022; Iqbal and Iqbal, 2024; Mahapatra and Seethamsetty, 2024).

In the current study, critical thinking is the sustained engagement with detailed ideas through analysis, synthesis, and critical evaluation rather than rote reproduction (Biggs et al., 2022; Entwistle and Peterson, 2004). It involves questioning assumptions, making conceptual connections, and applying knowledge creatively. Within DEs, critical thinking supports cognitive presence that Garrison et al. (2000, p. 89) define as “the extent to which learners are able to construct and confirm meaning through sustained reflection and discourse.” Together, the above definitions frame how GenAI influences intellectual engagement and the quality of academic contributions. The study supports the importance of AI literacy that extends beyond technical competence to ethical, reflective, and context-sensitive use. Long and Magerko (2020) define AI literacy as the set of knowledge, skills, and dispositions that enable a person to understand what GenAI is and how it works, use GenAI tools effectively, critically evaluate their outputs and limits (e.g., bias, reliability, privacy), and make informed, responsible choices about when and how to apply, or not apply, GenAI in practical contexts. For students and academics, GenAI literacy entails understanding AI tools, critically evaluating their outputs, and using them to enhance, not replace, human perspective, supported by pedagogy and assessment that promote originality, reflection, and accountability, and keep human judgment in balance with digital innovation. Despite the growing interest of GenAI in DE, a gap remains in understanding how these tools guide critical learning of Academic English modules, cognitive presence, and scholarly engagement in the Global South. Recent studies often focus on either benefits (linguistic expression, productivity) or risks (plagiarism, surface learning); few studies integrate both while addressing EMI, infrastructure, and diverse student needs (Akintolu et al., 2024; Ibrahim and Kirkpatrick, 2024; Suliman et al., 2024). The challenge is to reconcile innovation with intellectual rigor so that GenAI supports learning without undermining critical inquiry, originality, or ethical practice.

This study responds to the following research questions:

• How does Generative AI (GenAI) influence critical thinking and cognitive presence among students in a South African DE context?

• How can lecturers within South African DE contexts effectively develop students' AI literacy skills to promote the ethical and responsible use of GenAI in academic writing and assessment?

2 Literature review

2.1 Influence of GenAI on critical thinking and cognitive presence in DE

GenAI tools such as ChatGPT, Gemini, and BlackBox contribute toward how students and academics engage with learning and scholarly writing. Studies indicate that these tools provide scaffolding for idea generation, vocabulary development, and linguistic refinement, particularly for English as a Second Language (ESL) students in open distance learning contexts (Mahapatra and Seethamsetty, 2024; Tlili et al., 2023). Recent research indicates that GenAI can enhance language-learning efficiency, initiative, and independent thinking (Maphoto et al., 2024; Mohale and Suliman, 2025). For example, a 2025 survey by Fan et al. (2025) that use a sample of Chinese engineering students found that more than half of respondents reported that GenAI tools improved their initiative and creativity, though many remained concerned about the reliability of GenAI outputs in their discipline. Furthermore, Kasneci et al. (2023) found that many German students perceived GenAI tools as enhancing creativity and engagement, though concerns persisted about reliability in technical subjects. A 2025 two-wave longitudinal survey of 323 Chinese university students by Bai and Wang (2025) found that both the quality of their interactions with GenAI and the quality of the AI output positively influenced learning motivation and creative self-efficacy; further, learning motivation mediated the link between GenAI output quality and learning outcomes, and the effect was stronger for students with higher levels of creative thinking.

Despite these benefits, other scholars caution that uncritical reliance on GenAI can undermine cognitive presence, understood as the ability to construct and confirm meaning through sustained reflection and discourse (Garrison et al., 2000). A systematic review by Maphoto et al. (2024) in South Africa noted that in open distance education environments, students often substitute critical reflection with AI-generated answers, which risks diminishing originality and higher-order reasoning. Moreover, a recent study by Mohale and Suliman (2025) from a South African DE context reports extensive GenAI use in first-year academic writing, that triangulates GenAI-detection screenshots from eight student scripts (assignments and examinations) with open-ended questionnaires from lecturers. The analysis found multiple cases of high to complete AI generation in written work (including scripts showing 81%−100% AI involvement) alongside fully human-written scripts that reveals a wide range of reliance that maps onto concerns about originality, authorship, and diminished cognitive engagement.

2.2 AI literacy skills to ensure responsible use of GenAI

The literature positions academia to cultivate critical AI literacy that is ethical, reflective, and context-aware in Society 5.0. Noble et al. (2022) and Hashim (2024) frame Society 5.0 as human-centered and calls for pedagogy that complements technology with creativity and ethics. Moreover, Van Dis et al. (2023) and Bozkurt and Sharma (2024) argue for teaching approaches that help students use GenAI critically and responsibly. From a literacy perspective, Han (2025) contend that competence must extend beyond functional skills to include bias, equity, and ethical awareness. For example, a North American survey by Baytas and Ruediger (2025) found that while a significant majority of lecturers had experimented with GenAI, only a small proportion felt confident in their capacity to integrate it into teaching. Nikolopoulou (2024) shows that when thoughtfully integrated, tools such as ChatGPT can enhance lecturers' capacity to scaffold creativity, reflective thinking, and student engagement, and indicates that responsible GenAI use depends on guided, context-sensitive design. At the learner-behavior layer, Owan et al. (2025) draws on a modified Unified Theory of Acceptance and Use of Technology (UTAUT) model, found that perceived usefulness, ease of use, and ethical awareness significantly influence students' ChatGPT adoption patterns in higher education. In related work, Holstein et al. (2022) reveal that effective AI-education integration requires interdisciplinary frameworks that combine technical, critical and social dimensions. These studies indicate that academia should balance capability with responsible and metacognitive engagement, consistent with Society 5.0's values.

However, evidence from gamification research proposes that perceived usefulness arises from combinations of design elements rather than single features. Denden et al. (2025) used Fuzzy-Set Qualitative Comparative Analysis (fsQCA) to identify multiple effective configurations (e.g., badges plus feedback and progress cues) and reinforces the current study's position that GenAI supports cognitive presence when arranged with pedagogical supports, not as a stand-alone tool. However, Zhu et al. (2025) advocate process-based approaches such as multiple drafts, annotated bibliographies, reflective AI-use commentaries, to redesign practice for responsible practice, while Munaye et al. (2025) conducted a systematic review of 40 studies on ChatGPT use in education and highlight how institutions need to develop governance, policy and pedagogical strategies to ensure the responsible integration of GenAI tools rather than their unreflective adoption. These contributions point to practical directions and demonstrates the need for discipline-spanning, scalable empirical validation.

3 Theoretical framework

This study draws on a hybrid theoretical framework that integrates the Community of Inquiry (CoI) framework (Garrison et al., 2000) with emerging AI literacy frameworks advocated by Celik (2023); Faruqe et al. (2022); and Georgiva et al. (2024). The CoI framework explains meaningful online learning that emerges from the interaction of cognitive presence (students constructing meaning through inquiry), social presence (participants presenting themselves as real, trusted peers), and teaching presence (instructors designing, facilitating, and directing learning; Fiock, 2020; Noteboom and Claywell, 2010). These elements are highly relevant in a DE context, where student engagement, reflection, and collaboration are central to academic English development. In this context, GenAI technologies both extend and challenge the subtleties of presence: while they may support students by scaffolding reflection and generating ideas, they also risk undermining metacognitive awareness, engagement and originality when used uncritically.

At the same time, the development of GenAI tools in academia indicates the need for frameworks that address new literacies. Thus, the AI literacy framework as explained by Celik (2023) and Faruqe et al. (2022) draws attention to the capacity of students and lecturers to understand how GenAI functions, critically evaluates its outputs, integrates GenAI into learning processes, and engages with it ethically and transparently. The AI literacy model includes elements such as technical fluency (how GenAI works and how to operate it), critical evaluation (interrogating accuracy, bias, and provenance), practical integration (using GenAI to support, not replace, planning, drafting, and revision), and ethical engagement (transparent disclosure, citation, and responsible boundaries; Holstein et al., 2022; Long and Magerko, 2020). The elements further extend beyond functional competence to include reflective and value-driven engagement to support the principles of Society 5.0 that combines the human with the digital (Noble et al., 2022; Georgiva et al., 2024; Rejeb et al., 2025). The combination of these frameworks is demonstrated below in Figure 2.

Based on the Figure 2 above, CoI, foregrounds cognitive presence, anchors the analysis of how students' progress from triggering questions through exploration to integration and resolution (Garrison et al., 2000), while AI literacy specifies the competencies of technical fluency, critical evaluation, practical integration, and ethical engagement required to use GenAI responsibly and productively (Holstein et al., 2022; Long and Magerko, 2020). Taken together, these frameworks capture both the pedagogical processes of learning and the skills/values needed for GenAI engagement (Arowosegbe et al., 2024; Ibrahim and Kirkpatrick, 2024; Mahapatra and Seethamsetty, 2024). CoI provides the theoretical lens for how students construct meaning, interact, and reflect in online contexrs (Fiock, 2020; Noteboom and Claywell, 2010, and AI literacy delineates the protocols and practices that keep learning authentic (Celik, 2023; Faruqe et al., 2022). This dual framework interrogates not only how GenAI outlines learning presences in DE, but also how curricula, assessments, and teaching strategies can cultivate AI-aware, critically reflective students (Mohale and Suliman, 2025; Sevnarayan and Maphoto, 2024). This study prioritizes cognitive presence as the analytic target because the study examines critical thinking and meaning making irrespective of discipline; GenAI most directly perturbs this proximal outcome, and scaffolds idea generation and organization while risking illusions of understanding, reduced productive struggle, and flattened originality if used uncritically. Accordingly, social and teaching presences are treated as enabling conditions and held comparatively constant, via existing design and participation norms (Garrison et al., 2000; Kasneci et al., 2023) to isolate the effects of AI literacy interventions on reasoning quality. It is required that students disclose any GenAI use, keep simple AI-use logs (prompt → output → revision), trace sources for any GenAI suggested claims, and show evidence of their own revisions. Therefore, the hybrid framework addresses two gaps in current scholarship: (i) scarce empirical evidence on how GenAI redesigns the undercurrents of presence in distance education, and (ii) limited research on AI literacy in African academia where structural realities pose distinctive ethical and practical demands.

4 Methodology

4.1 Research approach

This study adopted a qualitative, interpretive design to explore how GenAI impacts critical thinking in academia within the context of Society 5.0. A qualitative approach was chosen because it enables an understanding of meanings, experiences, and pedagogical implications associated with the integration of GenAI tools such as ChatGPT, Gemini, and BlackBox (Owoahene Acheampong and Nyaaba, 2024; Dahal, 2024). As (Creswell and Poth 2018, p. 7) observe, “qualitative research begins with assumptions and the use of interpretive frameworks that inform the study of research problems addressing the meaning individuals or groups ascribe to a social or human problem.” Rather than seeking to quantify usage, the current study focused on interpreting how these tools influence cognitive presence, originality, and critical engagement in academia.

4.2 Research design

This study employs a single, bounded qualitative case study of UM to investigate how GenAI mediates cognitive presence, the progression from triggering questions through exploration to integration and resolution in academia. According to (Heale and Twycross 2018, p. 17), “a case study can be defined as an intensive study about a person, a group of people or a unit, which is aimed to generalize over several units.”

As such, a case study is the best fit because the phenomenon is context-dependent (Yin, 2018; Stake, 1995),1 mechanism-rich,2 and requires multiple data sources3 to trace sequences of reasoning over time (Miles et al., 2014; Yin, 2018). This design lets us hold social and teaching presences comparatively constant (Garrison et al., 2000; Shea and Bidjerano, 2009) but examines the proximal learning outcome of interest, critical thinking, and how AI-literacy elements4 either scaffold or short-circuit it (Celik, 2023; Faruqe et al., 2022). In short, a bounded case study provides the thick description, triangulation, and process tracing necessary to generate credible, actionable perspectives about GenAI's impact on cognitive presence in a DE context (Lincoln and Guba, 1985; Tisdell et al., 2025).

4.3 Research context

DE has become a defining feature of South African higher education, accounting for nearly 35.5% of public university enrolments in 2022 [Department of Higher Education and Training (DHET), 2023] and historically approaching 40% in the late 2000s [Council on Higher Education (CHE), 2012]. DE is delivered through various models and included fully online, blended, and traditional open-distance formats (McKay, 2022) and remains particularly dominant in large-scale undergraduate programmes such as those provided by the University of South Africa (Mashile et al., 2020). English serves as the primary language of instruction, although it is a second language for many students (Ngcobo and Barnes, 2021; Xulu-Gama and Hadebe, 2022). While DE provides flexibility and access for working adults and first-generation students, challenges such as limited connectivity, high data costs, and uneven digital access persist (Krönke, 2020). These dynamics make South African DE a critical context for examining how GenAI tools guide writing practices, cognitive presence, and critical thinking in distance education.

The study is situated at a South African DE university (pseudonym: UM) that serves a widely non-traditional, multilingual student body: many are working adults and first-generation students, often mobile-only,5 drawn from urban townships and rural provinces, and balancing study with employment and caregiving (University of South Africa, 2025). While English is the language of learning and teaching, a large proportion of students are multilingual with home languages such as isiZulu, isiXhosa, Sesotho, Setswana, Sepedi, Tshivenda, Xitsonga, and Afrikaans, which creates predictable pressure points around academic English, genre conventions, and paraphrase practices (Suliman et al., 2024; University of South Africa, 2025). Structural challenges include unstable connectivity, high data costs, load-shedding, variable digital fluency, and time poverty (Maphoto, 2024); pedagogically, there is low forum participation and uneven feedback cycles typical of large-scale distance provisions (Letseka et al., 2025). Within this model, independent study refers to self-directed learning outside scheduled touchpoints6 that requires self-regulation, planning, and metacognitive reflection. At the same time, UM actively exposes students to technology-enhanced learning,7 and provides a practical context to examine how GenAI interacts with critical thinking in DE, whether it productively scaffolds inquiry and language production or, if uncritically used, short-circuits the reflective work independent study is meant to cultivate.

4.4 Population and sampling

The total population of English module students at UM consisted of approximately 1,700 students enrolled during the 2025 academic year. In qualitative research, a population refers to the entire group of individuals, cases, or contexts that share relevant characteristics from which the researcher seeks to draw perspectives (Creswell and Creswell, 2017). From this population, a purposive sample of 17 participants was selected. This included 16 senior undergraduate students, and one lecturer directly involved in the teaching and assessment of the module. Purposive sampling was employed to ensure the inclusion of participants who could provide information-rich, contextually grounded perspectives into the use of GenAI tools in teaching and learning. As (Creswell and Poth 2018, p. 148) explain, “purposeful sampling enables the researcher to intentionally select participants who can best help to understand the central phenomenon.”

The selection criteria were clearly defined to strengthen the rigor and transparency of the sampling process. Participants were included if they met the following conditions as shown in Table 1.

This sampling approach as shown in Table 1, ensured that the selected participants possessed first-hand experience and reflective capacity regarding GenAI's role to guide cognitive presence and critical thinking within a DE context. Rather than aiming for statistical representativeness, the sample was chosen for its depth of perspective and contextual relevance (Palinkas et al., 2015) and this supports the study's interpretive, case-based orientation. The selection of the 17 participants was intentional and guided by the principle of information richness (Patton, 2015). Rather than aiming for representativeness, participants were chosen because their engagement patterns, reflective submissions, and evaluation responses demonstrated sustained and meaningful interaction with GenAI tools in the module. These individuals were thus positioned to provide detailed, experience-based perspectives into how GenAI influenced their critical thinking, academic writing, and cognitive presence within a DE context. The inclusion of one lecturer further ensured triangulation by capturing the pedagogical perspective on GenAI use. This purposive, criterion-based selection enabled the researcher to access participants who could best indicate the study's central phenomenon and contribute to conceptual depth and thematic saturation.

4.5 Data collection instruments

Data collection drew on two complementary sources to ensure methodological triangulation. Cohen et al. (2000, p. 254) define triangulation as an “attempt to map out, or explain more fully, the richness and complexity of human behavior by studying it from more than one standpoint.” In this study, triangulation was achieved through the integration of student evaluations and Moodle observations to enable a more holistic understanding of how GenAI mediates academic engagement and critical thinking in a digital learning environment. Student evaluations complemented these observations by eliciting students' perceptions, experiences, and reflections on their engagement with GenAI. The evaluations provided perspectives into both the perceived affordances (e.g., enhanced feedback, improved language production) and challenges (e.g., overreliance, reduced critical engagement) of GenAI use in a DE context. All data were collected online using Microsoft Forms and Moodle and this relates with the digital nature of the DE context. Evaluations and Moodle observations were prioritized over interviews because they provided in-situ evidence of GenAI-mediated learning interactions to reduce recall and social-desirability bias and minimized participant burden for time-constrained DE students, many of whom balance study with employment and caregiving responsibilities. Together, these methods generated contextually grounded, triangulated evidence on how GenAI influences academic practices that allows an interpretation of students' critical thinking and engagement processes within a DE framework.

Moodle observations focused on student interactions with GenAI-related tools which includes AI avatars, chatbots, and the AI Masterclass activities embedded within the module site. These observations examined how students used GenAI to support writing practices, feedback interpretation, and assessment preparation, thereby revealing how such tools scaffold or short-circuit cognitive presence and independent inquiry. A structured non-participant observation protocol was conducted over one semester (February–June 2025) to analyse student engagement with GenAI-mediated activities on Moodle. This included the AI Tutor Pro chatbot, AI Masterclass, and discussion forums. Weekly observations captured interaction frequency, prompt types, follow-up queries, and reflective or verification behaviors. The qualitative findings indicate that students' engagement with GenAI functions as a conditional amplifier of cognitive presence and critical literacy and enables epistemic access and ethical reflexivity while also exposing risks of surface-level engagement and over-reliance, as evidenced across themes of cognitive presence (Table 2), critical AI literacy (Table 3), and pedagogical scaffolding strategies for responsible GenAI use (Table 4). Data were drawn from Moodle analytics, chat transcripts, and field notes recorded in an observation matrix based on Garrison et al.'s (2000) COI framework (triggering, exploration, integration, resolution). The non-intrusive approach ensured authenticity, and findings were triangulated with Microsoft evaluation responses to enhance credibility.

4.6 Data analysis

The dataset comprised Moodle observations of chatbot interaction transcripts Masterclass attendance, Microsoft evaluations with open-ended items that includes Masterclass feedback. All data were exported from Moodle/Microsofts, de-identified, cleaned and segmented into analysable units. Next, Braun and Clarke's (2006) six steps, I (1) read the full corpus for familiarization; (2) generated initial codes using a dual strategy, deductive codes from CoI (focusing on cognitive presence: triggering → exploration → integration → resolution) and AI-literacy elements (technical fluency, critical evaluation, practical integration, ethical engagement), plus inductive codes emerging from the data (e.g., “illusion of understanding,” “AI voice flattening”); (3) collated codes into candidate themes; (4) reviewed themes against the whole corpus; (5) defined and named themes; and (6) wrote up with illustrative extracts. This analysis, linked to RQ1, traced how GenAI acted as a conditional amplifier of cognitive presence to enhance inquiry when pedagogy made thinking visible and diluting it when convenience replaced reasoning. This provided themes such as changing perceptions of critical thinking and GenAI as support vs. threat to critical literacy. I compared artifacts from the Moodle-integrated chatbot and the AI Masterclass with evaluations to examine how structured support cultivated critical AI literacy (e.g., prompt logs, justification of AI suggestions, and evidence of revision) to relate to RQ2.

4.7 Ethical considerations

Ethical considerations were carefully observed to ensure research integrity and participant protection. In line with Resnik's (2015, p. 1) definition of research ethics as “the principles, norms, and standards that guide responsible research conduct and protect the dignity, rights, and welfare of participants,” approval was obtained from UM's Research Ethics Committee, and informed consent was secured from all participants. Participation was voluntary; no coercion occurred, and students were free to withdraw at any time. In order to preserve anonymity, all data were de-identified and pseudonyms were used in transcripts and reporting.

5 Findings

5.1 RQ1: how does Generative AI (GenAI) influence critical thinking and cognitive presence among students in a South African distance education (DE) context?

In line with RQ1, the analysis of the data traced how GenAI redesigned cognitive presence, the construction and confirmation of meaning through sustained reflection and discourse, and the related behaviors of critical thinking. GenAI functioned as a conditional amplifier: it enhanced inquiry when pedagogy made thinking visible and it diluted inquiry when convenience replaced reasoning. The following themes emerged:

5.2 A change in perceptions of “critical thinking”

Students' reflections revealed a detailed redefinition of what “critical thinking” entails in an AI-mediated learning context. Rather than simply perceiving GenAI as either helpful or harmful, their responses illustrated underlying mechanisms of cognitive offloading and metacognitive recalibration guided by the demands of DE and EMI. Several participants described GenAI as a cognitive organizer that alleviated mental load and clarified challenging tasks. Student 1 (Evaluation Forms, 2025) explained, “I usually rely on AI tools to understand the work more better in a clearer sense.” The phrases show linguistic strain typical of EMI students, but the statement points to an underlying reliance on GenAI for cognitive scaffolding, a strategy to overcome linguistic and conceptual barriers. In contexts marked by time poverty and information overload, this use of GenAI supports the triggering and exploration phases of Garrison et al.'s (2000) CoI model where students initiate understanding and structure information but have yet to synthesize or evaluate knowledge independently.

Similarly, Student 2 (Evaluation Forms, 2025) noted that GenAI helps “improve your thoughts that are so messed up with all your subjects and deadlines and practicals.” This description exemplifies stress-induced cognitive overload, where GenAI acts as an external cognitive scaffold to restore order and focus. Such uses demonstrate how GenAI can mediate cognitive presence by managing surface-level organization and emotional regulation, important precursors to immersed learning in DE contexts characterized by isolation and heavy workload. In contrast, other students framed GenAI as enabling higher-order intellectual engagement once routine tasks were automated. Student 3 (Evaluation Forms, 2025) observed that GenAI helps them “concentrate on the important and groundbreaking parts of their research.” Here, GenAI is conceptualized as a metacognitive aid that redistributes effort, to allow students to move from mechanical production to conceptual synthesis and innovation. This pattern reflects the integration phase of cognitive presence, where students combine ideas into coherent meaning that indicate how GenAI can function as a catalyst for higher-order thinking when used deliberately and reflectively.

However, several students warned that GenAI may also diminish cognitive effort and erode intellectual ownership. Student 4 (Evaluation Forms, 2025) cautioned that “some students use it to do all their work instead of using it to assist them,” while Student 5 (Evaluations Forms, 2025) added that over-reliance “may compromise the outcome of the research.” These comments reveal awareness of ethical and motivational trade-offs, what recent scholarship terms “metacognitive laziness” (Fan et al., 2025), where convenience replaces reflection. In CoI terms, this represents regression to surface engagement, where automation replaces exploration and resolution. This theme shows that students' changed perceptions of critical thinking are not dichotomous but mechanistic: GenAI simultaneously scaffolds and short-circuits cognition depending on students' literacy, intent, and learning context. In EMI-based DE contexts, where linguistic strain and self-regulation challenges are high, GenAI provides compensatory cognitive support yet risks undermining the sustained reflection that true critical thinking demands.

5.3 The role of GenAI to support or undermine critical literacy

The themes are structured below according to the second theme:

The second theme revealed the ambivalent role of GenAI to redefine critical AI literacy. Students frequently credited GenAI with the provision of linguistic scaffolding and with enhancement of organization, cohesion, and the ability to “sound more academic.” Such affordances appear to lower entry barriers to disciplinary discourse in multilingual distance education contexts where linguistic confidence often mediates academic participation. For these students, GenAI functioned as a bridge to academic legitimacy that helped them meet institutional norms for clarity and tone. Student 6 (Evaluation Forms, 2025) described AI-assisted writing as essential for “grammar, organization, referencing, and compliance with academic norms,” to reflect the view that GenAI can enable access to academic conventions. Similarly, Student 7 (Evaluation Forms, 2025) emphasized that GenAI improved “how we say things” and made writing “sound more academic,” that recommended that GenAI tools help students construct a more professional academic voice. These reflections imply that GenAI supports epistemic access, a prerequisite to develop critical literacy among students that negotiate multiple linguistic identities.

At the same time, participants voiced ethical and cognitive literacy gaps that exposed uneven critical awareness. Student 8 (Evaluation Forms, 2025) noted that many peers “just copy as it is,” while Student 9 (Evaluation Forms, 2025) observed that ethical considerations “don't seem to phase them as I think too many … get away with submitting AI-generated assignments.” Such comments reveal a tendency among some students to use GenAI instrumentally rather than reflectively that treated it as a shortcut to compliance rather than a tool for learning. Viewed through the lens of cognitive presence (Garrison et al., 2000), this behavior indicates how students may bypass the exploration and integration phases of reflective inquiry, central to critical thinking, and settle instead for surface-level reproduction of ideas.

In contrast, several students demonstrated emerging ethical discernment. Student 9 (Evaluation Forms, 2025), while aware of plagiarism risks, actively avoided over-reliance that stated that “there's too many duplicated answers and having work similar to my peers would be a big no.” Student 10 (Evaluation Forms, 2025) echoed this stance that advised peers not to “copy and paste” but to use GenAI for brainstorming and idea generation, thus positioning GenAI as a collaborative cognitive partner rather than a substitute for originality. These perspectives reflect a metacognitive stance and an awareness of when and how to use GenAI tools responsibly.

Two participants extended this discussion by addressing macro-level ethical concerns. Student 11 (Evaluation Forms, 2025) warned about data privacy and algorithmic misuse that noted that GenAI systems “depend on gathering and analyzing substantial quantities of information,” which introduces risks of data breaches and exploitation. Student 12 (Evaluation Forms, 2025) highlighted the importance of institutional accountability that observe that “the ethical considerations and rules and regulations… are widely publicized,” yet some students “deliberately plagiarize.” These remarks indicate a systemic literacy, where ethical responsibility is seen not only as an individual obligation but also as part of institutional governance and transparency. Taken together, this theme indicates a tension between empowerment and dependency. GenAI can democratize access to academic discourse by providing linguistic support and it simultaneously risks diminishing originality, reflective judgement, and ethical engagement if used uncritically. The findings indicate that students occupy diverse positions along a continuum, from functional users seeking academic compliance to critical users that demonstrated ethical reflexivity. This ambivalence demonstrates the need for pedagogical interventions that explicitly cultivate critical AI literacy that extend beyond technical proficiency toward reflective, responsible, and value-driven engagement associated with the principles of Society 5.0.

5.4 RQ2: how can lecturers within South African DE contexts effectively develop students' AI literacy skills to promote the ethical and responsible use of GenAI in academic writing and assessment?

In line with the study's RQ2, the analysis specifically examined what pedagogical strategies can support the development of critical AI literacy among students and lecturers to ensure that GenAI is used responsibly within the Society 5.0 context. Within academia, GenAI alongside its clear benefits for linguistic scaffolding and organization.

5.5 AI chatbot as a scaffold for inquiry

The availability of a Moodle-integrated chatbot trained on the study guide demonstrates how GenAI can function as a pedagogical scaffold rather than a shortcut. This allows students to pose content-specific questions and receive targeted, contextually relevant responses and the tool supports active engagement with prescribed materials rather than dependence on generic external sources. This structured arrangement with the module content helps reduce anxiety and cognitive overload that provides reassurance that the guidance remains consistent with assessment criteria and learning outcomes. Such integration embodies the principle of “guided autonomy,” students operate independently but within pedagogically defined boundaries that promote self-regulation and reflection. In contrast, unregulated use of external GenAI platforms expose students to epistemic risks, such as misinformation, overreliance, or unintentional plagiarism, which undermine the development of critical literacy. As shown in Figure 3, the AI Tutor Pro operates as the module's dedicated digital learning assistant that provides both instructional guidance and immediate feedback. The AI avatar provides a brief orientation video before students initiate interactive dialogue to scaffold responsible tool use.

Feedback from participants indicate the chatbot's role to enhance perceived accessibility and cognitive presence. Student 15 (Evaluation Forms, 2025) noted, “The chatbot helps me understand sections of the study guide that I usually find confusing, it's like having a tutor available whenever I need it.” This reflection demonstrates that the tool not only improves comprehension of material but also cultivates a sense of academic presence and support, which is critical in distance learning contexts. Unlike human tutors, whose availability is limited by scheduling, the chatbot provides continuous, low-stakes opportunities for clarification and practice to reinforce independent learning and confidence. This intervention exemplifies how AI-mediated scaffolding can operationalise the “teaching presence” within the COI framework (Garrison et al., 2000) that bridges the temporal and spatial gaps typical of DE contexts. The evidence indicates that when GenAI is contextually integrated and pedagogically guided, it can enhance both learning engagement and cognitive depth that addresses the gap between accessibility and meaningful academic development.

Students are guided through AI Tutor Pro, shown in Figure 3, toward clarification, questioning, and reflection, processes that collectively reinforce the exploration phase of cognitive presence (Garrison et al., 2000). This design encourages students to interrogate content rather than passively consume it to help them make sense of new ideas through structured inquiry. Over time, such interaction cultivates the core skills of critical AI literacy that evaluates the accuracy of GenAI outputs, formulated follow-up questions, and discerned when further human or scholarly input is required. In this way, the chatbot transitions GenAI from a functional assistant (e.g., grammar checking or summarizing readings) to a dialogic partner in meaning-making. It invites students to engage in iterative reasoning, reflection, and self-regulation that supports a sense of agency and intellectual ownership over their learning. This pedagogical configuration supports with the ethos of Society 5.0 that positions GenAI as a collaborator that enhances human capability rather than replacing it. The tool supports a move from automation to augmentation, where critical reflection becomes central to ethical and informed participation in AI-mediated learning.

5.6 AI masterclass for responsible use of GenAI

The module also incorporates an AI Masterclass, introduced through the avatar depicted in Figure 4, designed to explicitly teach students how to engage with GenAI responsibly and reflectively. The Masterclass introduces the core dimensions of critical AI literacy that include the ethical use of GenAI in academic writing, prompt engineering for purposeful inquiry, strategies for brainstorming and idea generation, and safeguards to ensure that GenAI outputs support rather than replace original thought. This structured intervention bridges the gap between functional skills (such as grammar and summarizing) and reflective academic practice that positions GenAI as a pedagogical collaborator that upholds academic integrity. Importantly, the Masterclass directly addresses the uneven ethical awareness observed in the data. While some students previously reported uncritical reliance on GenAI or “copying answers as they are,” others demonstrated growing awareness of plagiarism, duplication, and data privacy. The Masterclass provides a shared baseline of ethical competence that indicates that all students, regardless of prior digital literacy, receive systematic guidance for responsible GenAI use.

Feedback from participants indicate this transformation. Student 10 (Evaluation Forms, 2025) remarked: “The AI Masterclass showed me how to use prompts properly. Before, I would just copy answers, but now I use AI to help me think of ideas and then build my own arguments.” This reflection signals a change from passive consumption to active meaning-making that indicate how guided instruction can move students into the integration phase of cognitive presence (Garrison et al., 2000), where they begin to internalize knowledge and apply it critically. The Masterclass design also employs affective scaffolding through an interactive avatar that introduces the session and invites students to sign up. This personalized interface reduces intimidation that surrounds AI ethics and supports an approachable learning environment. Furthermore, the inclusion of a post-evaluation reflection, where students critique what they learned and suggest institutional improvements, models the reflexive dimension of AI literacy. It transforms students from recipients of instruction into co-constructors of ethical practice to reinforce both accountability and metacognitive awareness.

The AI Masterclass exemplifies how explicit pedagogical mediation transforms GenAI from a technological novelty into a catalyst for critical engagement, ethical reasoning, and cognitive depth, key attributes of responsible participation in AI-mediated higher education and the human-centered vision of Society 5.0.

The inclusion of the AI Masterclass and avatar support, as shown in Figure 4, extends beyond the development of functional competence to strengthen the reflective, responsible, and contextual dimensions of critical AI literacy. This design ensures that students not only acquire the technical ability to operate GenAI tools but also internalize the ethical and epistemic responsibilities associated with their academic use. The use of ethical reasoning and reflective prompting indicates explicit learning outcomes. The Masterclass thus moves students from surface-level dependence on GenAI for quick answers toward critical, inquiry-driven engagement that supports the human-centered ethos of Society 5.0. The findings further indicate that when lecturers embed structured AI-literacy supports that include curriculum-aligned tools, explicit usage guidelines, and scaffolded skills training, students exhibit stronger cognitive-presence behaviors, such as inquiry, integration, and reflection. This reveals that GenAI's pedagogical value emerges not from its mere inclusion, but from its guided contextualization within teaching presence, which directly addresses RQ2.

6 Discussion

6.1 Positioning the findings within Society 5.0

Taken together, the findings indicate that GenAI operates as a conditional amplifier of learning, consistent with the Society 5.0's human-centered ethos to enhance or attenuate cognitive presence that depends on whether AI-literacy supports are embedded (Garrison et al., 2000; Ibrahim and Kirkpatrick, 2024). Students consistently valued GenAI for organizational scaffolding and linguistic support, yet observational data showed this often devolved into surface-level engagement and limited dialogue. In Society 5.0, the findings show that GenAI can enhance critical thinking and cognitive presence when students use it to organize ideas, broaden the search space, and iteratively revise, and when tasks require them to make their reasoning visible (Garrison et al., 2000; Denden et al., 2025; Noble et al., 2022). In structured activities and assessments that included support from the AI chatbot and AI Masterclass, students moved beyond exploration to integration and resolution: arguments were clearer, references were more accurate, and participation was higher than in unstructured forum work (Arowosegbe et al., 2024; Ibrahim and Kirkpatrick, 2024; Mahapatra and Seethamsetty, 2024; Noteboom and Claywell, 2010). In these conditions, GenAI operated as cognitive load management and freed student capacity for analysis and synthesis rather than replacing them (Bai and Wang, 2025; Fan et al., 2025). The same tools, however, weakened cognitive presence when convenience went unchecked. Where students imported GenAI text verbatim, elaboration was thin and interaction minimal; forums showed low participation and little back-and-forth-patterns associated with surface learning (Biggs et al., 2022) and what recent work terms metacognitive laziness (Cotton et al., 2023). In open-distance contexts, this convenience effect mirrors South African evidence that shortcuts can limit originality and attenuate inquiry (Maphoto et al., 2024). In an English-medium, open-distance context, GenAI's linguistic affordances were particularly salient. Students widely reported improvements in academic voice, cohesion, and speed, important for L2 writers, consistent with studies that show how GenAI can scaffold clarity for ESL students (Mahapatra and Seethamsetty, 2024; Mohale and Suliman, 2025). Yet these gains were fragile when AI literacy was uneven: duplicate phrasing and unoriginal assignments appeared despite claims of “not copying.” This reflects the difference between mere tool use and critical, reflective integration, verification, disclosure, and transformation, central to contemporary AI-literacy frameworks (Bozkurt and Sharma, 2024; Han, 2025; Holstein et al., 2022; Georgiva et al., 2024; Long and Magerko, 2020; Van Dis et al., 2023).

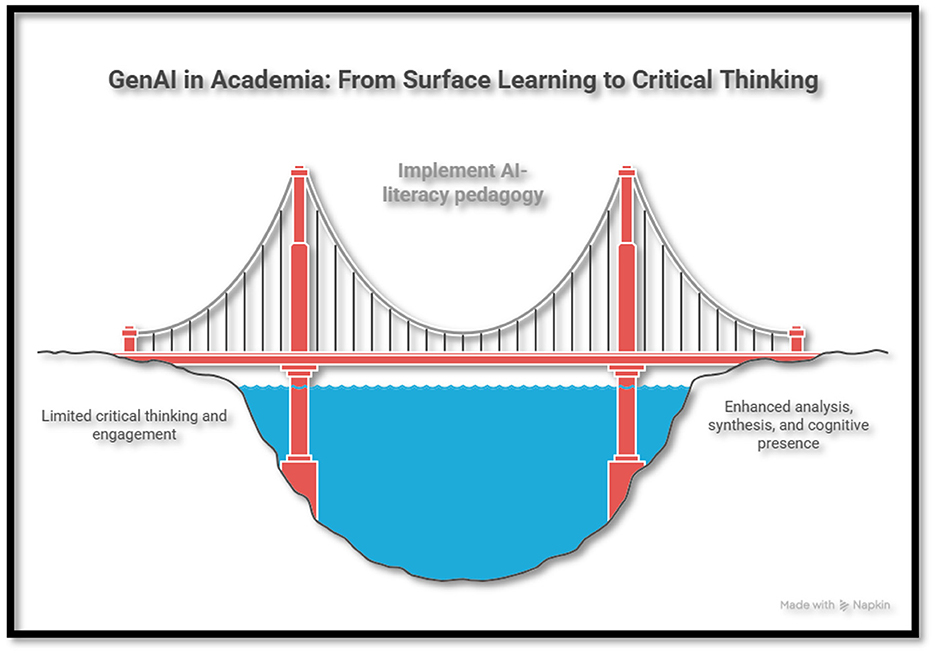

Pedagogy emerged as the decisive lever. A Moodle-integrated chatbot linked with module materials prompted clarifying questions and guided students back to prescribed texts; chatbot-mediated threads showed more on-task questions and text-linked references than unstructured forums and supported findings on pedagogical agents that bind tools to instructor intent (Baytas and Ruediger, 2025). The AI Masterclass moved practice from “copy answers” to “brainstorm → argue → verify,” with higher participation and more concise reflective evaluations, an operationalisation of the reflective, transparent use advocated in AI-literacy scholarship (Celik, 2023; Long and Magerko, 2020) and united within Society 5.0's innovation ethos (Bittle and El-Gayar, 2025; Denden et al., 2025; Nasr et al., 2025; Kasneci et al., 2023; Tlili et al., 2023). Figure 5 below demonstrates how AI-literacy carries students from limited critical thinking and engagement to enhanced analysis, synthesis, and cognitive presence with GenAI in academia.

Figure 5. GenAI in academia: from surface learning to critical thinking (Source: Napkin AI, 2025).

Figure 5 further validates how GenAI supports critical thinking and cognitive presence when pedagogy makes reasoning inspectable and demands integration/verification (Garrison et al., 2000); it undermines them when convenience is left unchecked and enhances surface approaches (Biggs et al., 2022; Cotton et al., 2023; Maphoto et al., 2024). This study shows that embedding module related supports, guided prompts, transparent AI-use statements, brief evaluations, and simple process evidence, move outcomes toward reflective engagement to preserve originality and authorship but maintain genuine linguistic benefits for DE, EMI students (Letseka et al., 2025; Sevnarayan and Maphoto, 2024).

7 Limitations

This single-site study, conducted within a South African DE and EMI context, has several limitations that should be acknowledged. While the findings provide perspectives into how GenAi impacts critical thinking in academia, their transferability to other contexts may be limited by institutional, technological, and linguistic factors. Future research could explore how similar interventions perform across diverse EFL or higher education contexts, both nationally and internationally, to evaluate the broader applicability of these findings. There are some limitations of concern: First, the study drew on a small purposive sample of 17 participants, which limits the transferability of findings to other institutions or disciplines. The observation window of one semester also constrains longitudinal interpretation; observed growth in student engagement with the Moodle chatbot and AI Masterclass may reflect short-term reactivity rather than sustained pedagogical impact. Second, while improvements in students' writing fluency and cohesion were noted, these gains may be confounded by other factors, such as existing EMI academic support structures and unequal digital access (e.g., bandwidth, data costs, and device availability). Hence, the observed effects cannot be attributed to GenAI use alone. Third, and most importantly, the researcher's dual role as lecturer and investigator presents a potential source of researcher and social-desirability bias. Students may have felt inclined to provide favorable responses or demonstrate compliance in evaluations. To mitigate this, the study employed reflexive strategies that include maintaining an audit trail of analytic decisions, the use of anonymous online data collection to reduce perceived power dynamics, and engagement in continuous self-reflection to acknowledge positionality and assumptions throughout the research process (Finlay, 2002). These strategies aimed to enhance credibility and confirmability despite the insider role.

8 Conclusions, recommendations, and future directions

Situated in a South African De context, this study's findings corroborate a growing body of evidence: GenAI is already embedded in students' writing practices and yields clear linguistic gains (fluency, cohesion, drafting speed) yet inviting surface approaches where tasks do not require the demonstration of reasoning. Importantly, the analysis of data shows that product-only assessments and single-tool plagiarism checks obscure authorship and cognitive effort, whereas process-visible designs, prompt journals, versioned drafts with rationales for accepting/rejecting. GenAI suggestions, and brief oral defenses, both reveal and strengthen integration and verification moves central to cognitive presence. Instructionally associated scaffolds (a Moodle chatbot directing students back to prescribed texts; an AI Masterclass on prompting, verification, attribution, and disclosure) enhanced use from reproduction to brainstorm → argue → verify workflows, with measurable improvements in participation and reflective commentary. Read against the Society 5.0 agenda, these results speak directly to RQ1: GenAI enhances critical thinking when pedagogy makes thinking inspectable and evidentiary; it erodes it when convenience substitutes for inquiry. Accordingly, I argue for institution-level disclosure guidelines such as transparency over prohibition, module-embedded AI-literacy for staff and students, and process-based assessment with AI-aware rubrics, paired with equity measures, low-data materials, reliable access, multilingual support, to ensure benefits are not restricted to well-resourced students. Future work may test these interventions longitudinally across disciplines to evaluate sustained effects on originality, cognitive presence, and responsible GenAI use.

Data availability statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

Author contributions

ZS: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Funding acquisition, Investigation, Methodology, Project administration, Resources, Software, Supervision, Validation, Visualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declared that financial support was not received for this work and/or its publication.

Conflict of interest

The author(s) declared that this work was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The author(s) declared that generative AI was used in the creation of this manuscript. Grammarly and Quillbot was used to correct language. ElicitAI was used to collect journal articles and for referencing.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Publisher's note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Supplementary material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/feduc.2026.1715468/full#supplementary-material

Footnotes

1. ^GenAI use unfolds amid multilingual cohorts, variable bandwidth, and self-directed study.

2. ^It is necessary to understand how GenAI influences thinking and not merely if it correlates with outcomes.

3. ^Learning artefacts, AI-use logs, interviews, observations and evaluations.

4. ^Technical fluency, critical evaluation, practical integration, ethical engagement.

5. ^Smartphone as primary device.

6. ^For example: working through the LMS study guide and readings, completing formative activities/quizzes, drafting and revising assignments, and preparing questions for Teams livestreams.

7. ^LMS, Teams livestreams, e-assessment, and emerging GenAI tools.

References

Akintolu, M., and Letseka, M. (2024). Rethinking openness for learning in open distance learning institutions. EUREKA Soc. Human. 2, 64–74. doi: 10.21303/2504-5571.2024.003375

Akintolu, M., Mitwally, M. A., and Letseka, M. (2024). South African open distance elearning student: the types, effectiveness, and preference of feedback support. West Afr. J. Open Flexible Learn. 12, 89–112.

Arowosegbe, A., Alqahtani, J. S., and Oyelade, T. (2024). Perception of generative AI use in UK higher education. Front. Educ. 9:1463208. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2024.1463208

Bai, Y., and Wang, S. (2025). Impact of generative AI interaction and output quality on university students' learning outcomes: a technology-mediated and motivation-driven approach. Sci. Rep. 15:1397. doi: 10.1038/s41598-025-08697-6

Baytas, C., and Ruediger, D. (2025). Making AI Generative for Higher Education: Adoption and Challenges Among Instructors and Researchers. Ithaka S+R. doi: 10.18665/sr.322677

Biggs, J., Tang, C., and Kennedy, G. (2022). Teaching for Quality Learning at University 5e. McGraw-Hill Education Maidenhead, (UK).

Bittle, K., and El-Gayar, O. (2025). Generative AI and academic integrity in higher education: a systematic review and research agenda. Information 16:296. doi: 10.3390/info16040296

Bozkurt, A., and Sharma, R. C. (2024). Are we facing an algorithmic renaissance or apocalypse? Generative AI, ChatBots, and emerging human-machine interaction in the educational landscape. Asian J. Distance Educ. 19, i–ix.

Braun, V., and Clarke, V. (2006). Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual. Res. Psychol. 3, 77–101. doi: 10.1191/1478088706qp063oa

Breque, M., De Nul, L., and Petridis, A. (2021). Industry 5.0: Towards a Sustainable, Human-centric and Resilient European Industry. Publications Office of the European Union.

Celik, I. (2023). Exploring the determinants of artificial intelligence (AI) literacy: digital divide, computational thinking, cognitive absorption. Telemat. Informat. 83:102026. doi: 10.1016/j.tele.2023.102026

Cohen, L., Manion, L., and Morrison, K. (2000). Research Methods in Education, 5th Edn., 254. London: RoutledgeFalmer.

Cotton, D. R. E., Cotton, P. A., and Shipway, J. R. (2023). Chatting and cheating: ensuring academic integrity in the era of ChatGPT. Innov. Educ. Teach. Int. 1–12. doi: 10.35542/osf.io/mrz8h

Council on Higher Education (CHE) (2012). Draft Policy Framework on Distance Education in South African Universities. CHE. Available online at: https://www.che.ac.za/sites/default/files/publications/DHET_Draft_Policy_Framework_on_Distance_Education_in_South_African_Universities_May_2012.pdf (Accessed October 10, 2025).

Creswell, J. W., and Creswell, J. D. (2017). Research Design: Qualitative, Quantitative, and Mixed Methods Approaches. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications.

Creswell, J. W., and Poth, C. N. (2018). Qualitative Inquiry and Research Design: Choosing among Five Approaches, 4th Edn. Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE Publications.

Dahal, N. (2024). How can generative AI (GenAI) enhance or hinder qualitative studies? A critical appraisal from South Asia, Nepal. Qual. Rep. 29, 722–733. doi: 10.46743/2160-3715/2024.6637

Denden, M., Tlili, A., Metwally, A. H. S., Wang, H., Yousef, A. M. F., Huang, R., et al. (2025). Which combination of game elements can lead to a useful gamification in education? Evidence from a Fuzzy-set qualitative comparative analysis. Open Praxis 17, 394–408. doi: 10.55982/openpraxis.17.2.844

Department of Higher Education and Training (DHET) (2023). Statistics on Post-School Education and Training in South Africa: 2023. Pretoria: DHET.

Duah, J. E., and McGivern, P. (2024). How generative artificial intelligence has blurred notions of authorial identity and academic norms in higher education, necessitating clear university usage policies. Int. J. Inf. Learn. Technol. 41, 180–193. doi: 10.1108/IJILT-11-2023-0213

Dwivedi, Y. K., Kshetri, N., Hughes, L., Slade, E. L., Jeyaraj, A., Kar, A. K., et al. (2023). Opinion paper:“so what if ChatGPT wrote it?” Multidisciplinary perspectives on opportunities, challenges and implications of generative conversational AI for research, practice and policy. Int. J. Inf. Manage. 71:102642. doi: 10.1016/j.ijinfomgt.2023.102642

Entwistle, N., and Peterson, E. R. (2004). Conceptions of learning and knowledge in higher education: relationships with study behaviour and learning outcomes. Educ. Psychol. Rev. 16, 325–347. doi: 10.1007/s10648-004-0003-0

Fan, L., Deng, K., and Liu, F. (2025). Educational impacts of generative artificial intelligence on learning and performance of engineering students in China. Sci. Rep. 15, 1–12. doi: 10.1038/s41598-025-06930-w

Faruqe, F., Watkins, R., and Medsker, L. (2022). Competency model approach to AI literacy: research-based path from initial framework to model. Adv. Artif. Intell. Machine Learn. 2, 580–587. doi: 10.54364/AAIML.2022.1140

Finlay, L. (2002). “Outing” the researcher: the provenance, process, and practice of reflexivity. Qual. Health Res. 12, 531-545. doi: 10.1177/104973202129120052

Fiock, H. S. (2020). Designing a community of inquiry in online courses. Int. Rev. Res. Open Distrib. Learn. 21, 135–153. doi: 10.19173/irrodl.v20i5.3985

Fukuyama, M. (2018). Society 5.0: aiming for a new human-centered society. Jpn. Spotlight 27, 47–50.

Garrison, D. R., Anderson, T., and Archer, W. (2000). Critical inquiry in a text-based environment: computer conferencing in higher education. Internet Higher Educ. 2, 87–105. doi: 10.1016/S1096-7516(00)00016-6

Georgiva, M., Kassorla, M., and Papini, A. (2024). AI Literacy in Teaching and Learning: A Durable Framework for Higher Education. EDUCAUSE. https://www.educause.edu/content/2024/ai-literacy-in-teaching-and-learning/introduction (Accessed January 20, 2026).

Han, F. (2025). Knowledge mapping, thematic evolution, and future directions of AI literacy research: an integration of bibliometric analysis and systematic review. SSRN 5332129. doi: 10.2139/ssrn.5332129

Hashim, M. A. M. (2024). Higher education via the lens of Industry 5.0: strategy and sustainability. Cogent Educ. 11:2188793.

Heale, R., and Twycross, A. (2018). What is a case study? Evid. Based Nurs. 21, 7–8. doi: 10.1136/eb-2017-102845

Holstein, K., McLaren, B. M., and Aleven, V. (2022). Designing for human–AI complementarity in K−12 education. AI Magazine 43, 17–30. doi: 10.1002/aaai.12058

Ibrahim, K., and Kirkpatrick, R. (2024). Potentials and implications of ChatGPT for ESL writing instruction: a systematic review. Int. Rev. Res. Open Distribut. Learn. 25, 392–415. doi: 10.19173/irrodl.v25i3.7820

Iqbal, U., and Iqbal, A. (2024). Assessing the effects of artificial intelligence on student cognitive skills: an investigation into enhancement or deterioration. Int. J. Business Anal. Technol. 2, 65–75.

Kasneci, E., Sessler, K., Küchemann, S., Bannert, M., Dementieva, D., Fischer, F., et al. (2023). ChatGPT for good? On opportunities and challenges of large language models for education. Learn. Individ. Differ. 103:102274. doi: 10.1016/j.lindif.2023.102274

Letseka, M., Mphahlele, R., and Akintolu, M. (2025). “University of South Africa,” in Handbook of Open Universities Around the World (Routledge), 105–116. doi: 10.4324/9781003478195-13

Lincoln, Y. S., and Guba, E. G. (1985). Naturalistic Inquiry. Sage. doi: 10.1016/0147-1767(85)90062-8

Long, D., and Magerko, B. (2020). “What is AI literacy? Competencies and design considerations,” in Proceedings of the 2020 CHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems (ACM),1–16. doi: 10.1145/3313831.3376727

Mahapatra, S., and Seethamsetty, S. (2024). Impact of ChatGPT on ESL students' academic writing skills: a mixed methods intervention study. Smart Learn. Environ. 11:26. doi: 10.1186/s40561-024-00295-9

Maphoto, K. (2025). One Plus one equals three: the synergy between GenAI and writing centers in ESL writing development. Stud. Learn. Teach. 6, 522–531. doi: 10.46627/silet.v6i2.599

Maphoto, K. B. (2024). Perceptions and innovations of academics in an open distance e-learning institution. Online J. Commun. Media Technol. 14:e202429. doi: 10.30935/ojcmt/14485

Maphoto, K. B., Sevnarayan, K., Mohale, N. E., Suliman, Z., Ntsopi, T. J., and Mokoena, D. (2024). Advancing students' academic excellence in distance education: exploring the potential of generative AI integration to improve academic writing skills. Open Praxis 16, 142–159. doi: 10.55982/openpraxis.16.2.649

Mashile, E. O., Fynn, A., and Matoane, M. (2020). Institutional barriers to learning in the South African open distance learning context. South Afr. J. Higher Educ. 34, 129–145. doi: 10.20853/34-2-3662

McKay, V. I. (2022). Status of distance learning in South Africa: contemporary developments and prospects. Commonwealth Learn. doi: 10.56059/11599/4480

Miles, M. B., Huberman, A. M., and Saldaña, J. (2014). Qualitative Data Analysis: A Methods Sourcebook, 3rd Edn. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Mohale, N. E., and Suliman, Z. (2025). The influence of generative AI and its impact on critical cognitive engagement in an open access, distance learning university. Compass J. Learn. Teach. Higher Educ. 18, 109–137. doi: 10.21100/compass.v18i1.1588

Munaye, Y. Y., Admass, W., Belayneh, Y., Molla, A., and Asmare, M. (2025). ChatGPT in education: a systematic review on opportunities, challenges, and future directions. Algorithms 18:352. doi: 10.3390/a18060352

Napkin AI (2025). Visual AI for Business Storytelling [Software]. Napkin AI. Available online at: https://www.napkin.ai/ (Accessed August 6, 2025).

Nasr, N. R., Tu, C.-H., Werner, J., Bauer, T., Yen, C.-J., and Sujo-Montes, L. (2025). Exploring the impact of generative AI ChatGPT on critical thinking in higher education: passive AI-directed use or human–AI supported collaboration? Educ. Sci. 15:1198. doi: 10.3390/educsci15091198

Ngcobo, M. N., and Barnes, L. A. (2021). English in the South African language-in-education policy on higher education. World English. 40, 84–97. doi: 10.1111/weng.12474

Nikolopoulou, K. (2024). Generative artificial intelligence in higher education: exploring ways of harnessing pedagogical practices with the assistance of ChatGPT. Int. J. Changes Educ. 1, 103–111. doi: 10.47852/bonviewIJCE42022489

Noble, S. M., Mende, M., Grewal, D., and Parasuraman, A. (2022). The fifth industrial revolution: how harmonious human–machine collaboration is triggering a retail and service [r]evolution. J. Retail. 98, 199–208. doi: 10.1016/j.jretai.2022.04.003

Noteboom, J. T., and Claywell, L. (2010). “Student perceptions of cognitive, social, and teaching presence,” in Paper Presented at the 26th Annual Conference on Distance Teaching and Learning (Madison, WI: University of Wisconsin–Madison).

Owan, V. J., Mohammed, I. A., Bello, A., and Shittu, T. A. (2025). Higher education students' ChatGPT use behavior: structural equation modelling of contributing factors through a modified UTAUT model. Contemp. Educ. Technol. 17:592. doi: 10.30935/cedtech/17243

Owoahene Acheampong, K., and Nyaaba, M. (2024). “Review of qualitative research in the era of generative artificial intelligence,” in Matthew, Review of Qualitative Research in the Era of Generative Artificial Intelligence. doi: 10.3102/IP.24.2112046

Palinkas, L. A., Horwitz, S. M., Green, C. A., Wisdom, J. P., Duan, N., and Hoagwood, K. (2015). Purposeful sampling for qualitative data collection and analysis in mixed method implementation research. Admin. Policy Mental Health Mental Health Serv. Res. 42, 533–544. doi: 10.1007/s10488-013-0528-y

Patton, M. Q. (2015). Qualitative Research & Evaluation Methods, 4th Edn. London: SAGE Publications.

Rejeb, A., Rejeb, K., Zrelli, I., and Süle, E. (2025). Industry 5.0 as seen through its academic literature: an investigation using co-word analysis. Discover Sustain. 6:307. doi: 10.1007/s43621-025-01166-0

Resnik, D. B. (2015). What is Ethics in Research and Why is it Important? National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences.

Sevnarayan, K. (2024). Exploring the dynamics of ChatGPT: students and lecturers' perspectives at an open distance e-learning university. J. Pedagogical Res. 8, 212–226. doi: 10.33902/JPR.202426525

Sevnarayan, K., and Maphoto, K. B. (2024). Exploring the dark side of online distance learning: cheating behaviours, contributing factors, and strategies to enhance the integrity of online assessment. J. Acad. Ethics 22, 51–70. doi: 10.1007/s10805-023-09501-8

Sevnarayan, K., and Potter, M. A. (2024). Generative artificial intelligence in distance education: transformations, challenges, and impact on academic integrity and student voice. J. Appl. Learn. Teach. 7, 104–114. doi: 10.37074/jalt.2024.7.1.41

Shabur, M. A., Shahriar, A., and Ara, M. A. (2025). From automation to collaboration: exploring the impact of Industry 5.0 on sustainable manufacturing. Discover Sustain. 6:341. doi: 10.1007/s43621-025-01201-0

Shea, P., and Bidjerano, T. (2009). Community of Inquiry as a theoretical framework: exploring relationships between cognitive, social, and teaching presence. Comput. Educ. 52, 543–553. doi: 10.1016/j.compedu.2008.10.007

Suliman, Z., Mohale, N. E., Maphoto, K. B., and Sevnarayan, K. (2024). The interconnectedness between Ubuntu principles and generative artificial intelligence in distance higher education institutions. Discover Educ. 3:188. doi: 10.1007/s44217-024-00289-2

Tisdell, E. J., Merriam, S. B., and Stuckey-Peyrot, H. L. (2025). Qualitative Research: A Guide to Design and Implementation. Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley and Sons.

Tlili, A., Shehata, B., Adarkwah, M. A., Bozkurt, A., Hickey, D. T., Huang, R., et al. (2023). What if the devil is my guardian angel: ChatGPT as a case study of using chatbots in education. Smart Learn. Environ. 10, 15–27. doi: 10.1186/s40561-023-00237-x

University of South Africa (2025). UNISA Fast Facts (Facts and Figures Brochure). Available online at: https://www.unisa.ac.za/static/corporate_web/Content/About/Documents/19611_UNISA%20Facts%20Sheets%20Brochure_February%202025_D3%20(002).pdf (Accessed July 07, 2025).

Van Dis, E. A. M., Bollen, J., Zuidema, W., van Rooij, R., and Bockting, C. L. H. (2023). ChatGPT: five priorities for research. Nature 614, 614–616. doi: 10.1038/d41586-023-00288-7

Wu, Y., Zhang, W., and Lin, C. (2025). Generative artificial intelligence in university education. IT Profess. 27, 69–74. doi: 10.1109/MITP.2025.3545629

Xu, X., Lu, Y., Vogel-Heuser, B., and Wang, L. (2021). Industry 4.0 and Industry 5.0—inception, conception and perception. J. Manuf. Syst. 61, 530–535. doi: 10.1016/j.jmsy.2021.10.006

Xulu-Gama, N., and Hadebe, S. (2022). Language of instruction: a critical aspect of epistemological access to higher education in South Africa. South Afr. J. Higher Educ. 36, 291–307. doi: 10.20853/36-5-4788

Yin, R. K. (2018). Case Study Research and Applications: Design and Methods, 6th Edn. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Keywords: academia, AI literacy, critical thinking, distance education, English as a medium for instruction, fifth industrial revolution, Generative Artificial Intelligence, Society 5.0

Citation: Suliman Z (2026) Society 5.0's rise of GenAI and the impact on critical thinking in DE. Front. Educ. 11:1715468. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2026.1715468

Received: 29 September 2025; Revised: 06 November 2025; Accepted: 12 January 2026;

Published: 09 February 2026.

Edited by:

Mohammed Saqr, University of Eastern Finland, FinlandReviewed by:

Kleopatra Nikolopoulou, National and Kapodistrian University of Athens, GreeceRicardo Pereira, Universidade Federal de Santa Catarina, Brazil

Copyright © 2026 Suliman. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Zuleika Suliman, ZXN1bGltejFAdW5pc2EuYWMuemE=

Zuleika Suliman

Zuleika Suliman